Submitted:

26 January 2024

Posted:

29 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Development of Aedes mosquito vectors in coastal brackish water and its impact on the control of dengue and other arboviral diseases

3. Understanding the implications for dengue control of the reduced Aedes vector densities and dengue incidence observed during the COVID-19 lockdown

4. Adaptation of fresh water Anopheles malaria vectors to salinity and its consequences for malaria control

5. Laboratory tests supporting clinical diagnosis of Lyme disease and tick-borne relapsing fever

6. SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and COVID-19 vaccines

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ramasamy, R. The scope of modern biotechnology. J. Natl. Sci. Found. Sri Lanka 1994, 22A, S1-S5. [CrossRef]

- Turgeon, M.L. Immunology and Serology in Laboratory Medicine, 4th ed.; Mosby Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2009; pp.1–525.

- Shah, J.S.; Ramasamy, R. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests for identifying protozoan and bacterial pathogens in infectious diseases. Diagnostics 2022; 12(5):1286. [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.S.; Burrascano, J.J.; Ramasamy, R. Recombinant protein immunoblots for differential diagnosis of tick-borne relapsing fever and Lyme disease. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2023, 60(4), 353-364. [CrossRef]

- Adashi, E.Y.; Gruppuso, P.A; Cohen, I.G. CRISPR therapy of sickle cell disease: The dawning of the gene editing era. Am. J. Med. 2024, S0002-9343(23)00798-2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.12.018. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fact sheet on dengue and severe dengue. Available online: https:// www. who. int/ news- room/ fact- sheets/ detail/dengue- and-severe- dengue (accessed 14 January 2024).

- World Health Organization. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. Available online: https:// whqli bdoc. who. int/ publications/ 2009/ 97892 41547 871_ eng. pdf (2009a) (accessed 17 August 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue. Available online: https:// www. cdc. gov/ dengue/ index. Html (accessed 15 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. Temephos in drinking-water: use for vector control in drinking-water sources and containers. Available online: https://www. who. int/ docs/ defau lt- source/ wash- documents/ wash- chemicals/ temephos- background- document. pdf? sfvrsn= c34fd a71_4 (accessed 17 August 2023).

- Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N.; Jude, P.J.; Dharshini, S.; Vinobaba, M. Larval development of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in peri-urban brackish water and its implications for transmission of arboviral diseases. PLoS. Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1369. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Jude, P.J.; Thabothiny, V.; Raveendran, S.; Ramasamy, R. Preimaginal development of Aedes aegypti in brackish and fresh water urban domestic wells in Sri Lanka. J. Vector Ecol. 2012, 37(2), 471–473. [CrossRef]

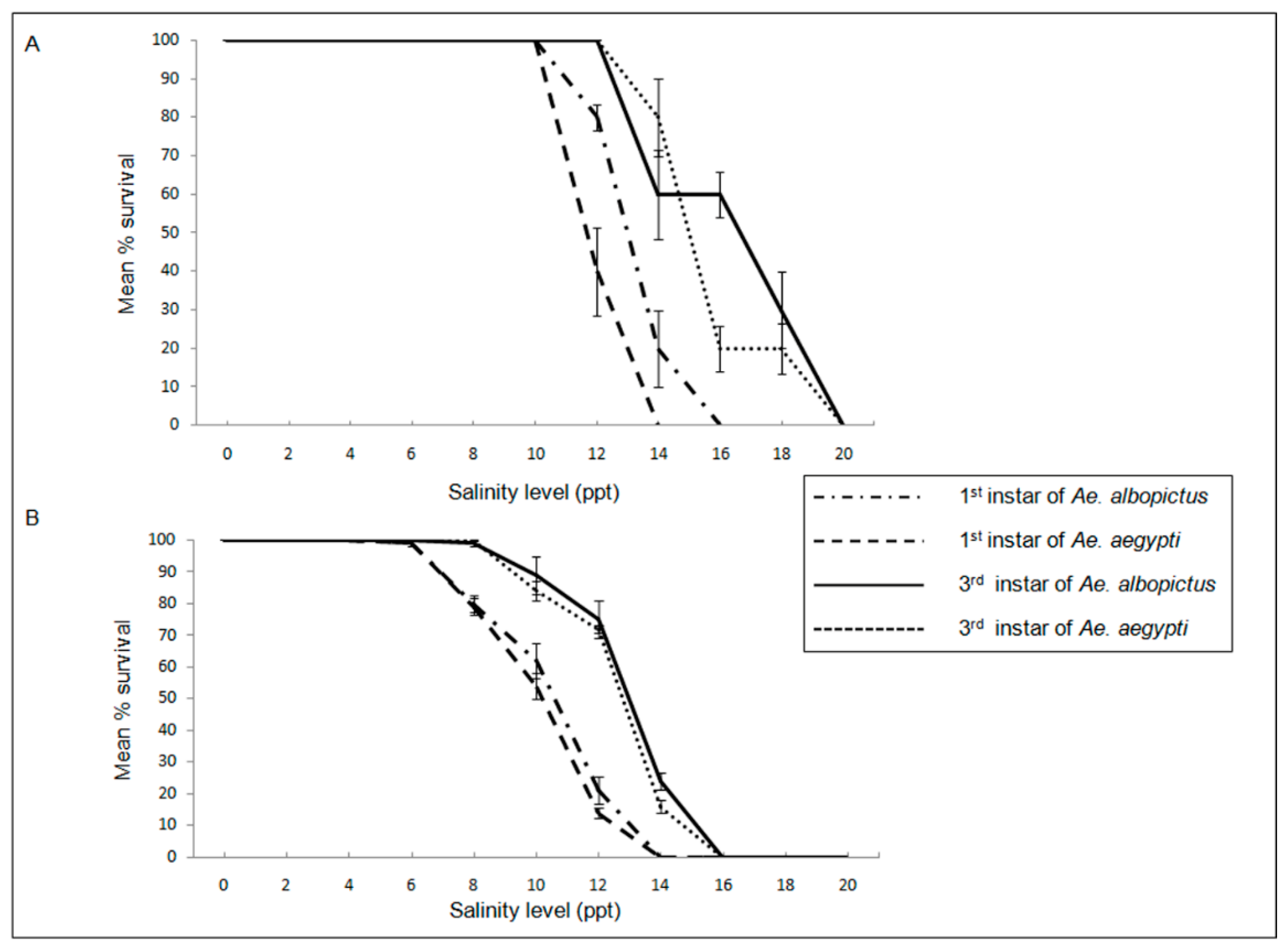

- Jude, P.J.; Tharmasegaram, T.; Sivasubramaniyam, G.; Senthilnanthanan, M.; Kannathasan, S.; Raveendran, S.; Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N. Salinity-tolerant larvae of mosquito vectors in the tropical coast of Jaffna, Sri Lanka and the effect of salinity on the toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis to Aedes aegypti larvae. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 269. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Karvannan, K.; Weerarathne, T.C.; Karunaratne, S.H.P.; Ramasamy, R. Development of the major arboviral vector Aedes aegypti in urban drain-water and associated pyrethroid insecticide resistance is a potential global health challenge. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12(1), 337. [CrossRef]

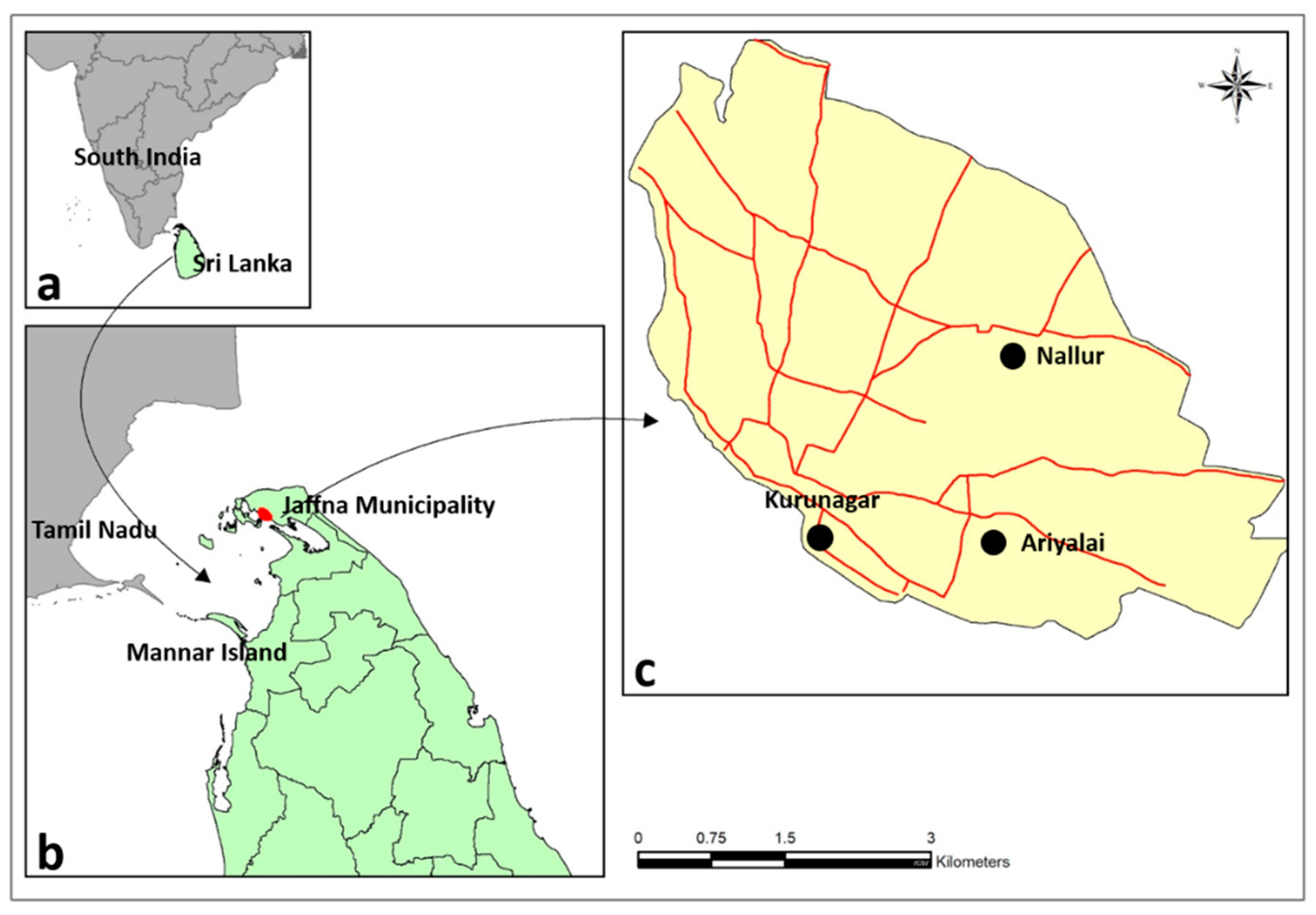

- Surendran, S.N.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Thiruchenthooran, V.; Raveendran, S.; Tharsan, A.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Karunakaran, S.; Ponnaiah, B.; Gomes, L.; et al. Aedes larval bionomics and implications for dengue control in the paradigmatic Jaffna peninsula, northern Sri Lanka. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14(1), 162. Erratum in: Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14(1), 218. [CrossRef]

- Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Thanihaichelvan, M.; Tharsan, A.; Eswaramohan, T.; Ravirajan, P.; Hemphill, A.; Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N. Resistance to the larvicide temephos and altered egg and larval surfaces characterize salinity-tolerant Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13(1), 8160. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Kesavan, L.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Tharsan, A.; Liyanagedara, N.; Eswaramohan, T.; Raveendran, S.; Singh,. OP.; Ramasamy, R. Morphological and odorant-binding protein 1 gene intron 1 sequence variations in Anopheles stephensi from Jaffna city in northern Sri Lanka. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2022, 36(4), 496-502. [CrossRef]

- Idris, F.H.; Usman, A.; Surendran, S.N.; Ramasamy, R. Detection of Aedes albopictus pre-imaginal stages in brackish water habitats in Brunei Darussalam. J. Vector Ecol. 2013, 38(1), 197-199. [CrossRef]

- Yee, D.A.; Himel, E.; Reiskind, M.H.; Vamosi, S.M. Implications of saline concentrations for the performance and competitive interactions of the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti (Stegomyia aegypti) and Aedes albopictus (Stegomyia albopictus). Med. Vet. Entomol. 2014, 28(1), 60-69. [CrossRef]

- de Brito Arduino, M.; Mucci, L.F.; Serpa, L.L.; Rodrigues, Mde. M. Effect of salinity on the behavior of Aedes aegypti populations from the coast and plateau of southeastern Brazil. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2015, 52(1),79-87.

- Galavíz-Parada, J.D.; Vega-Villasante, F.; Marquetta, M. del C.; Guerrero-Galvan, S.R.; Chong, O.; Navarrete-Heredia, J.L.; Cupul-Magaña, F.G. Effect of Temperature and Salinity on the Eclosion and Survival of Aedes aegypti (L) (Diptera: Culicidae) from Western Mexico. Rev. Cuba Med. Trop. 2019, 71(2), e353.

- Ratnasari, A.; Jabal, A.R.; Syahribulan; Idris, I.; Rahma, N.; Rustam, S.N.R.N.; Karmila, M.; Hasan, H.; Wahid, I. Salinity tolerance of larvae Aedes aegypti inland and coastal habitats in Pasangkayu, West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 1203-1210.

- Shamna, A.K.; Vipinya, C.; Sumodan, P.K. Detection of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) breeding in brackish water habitats in coastal Kerala, India and its Implications for dengue scenario in the state. Int. J. Entomol. Res. 2022, 7, 214–216.

- Ramasamy, R.; Jude, P.J.; Veluppillai, T.; Eswaramohan, T.; Surendran, S.N. Biological differences between brackish and fresh water-derived Aedes aegypti from two locations in the Jaffna peninsula of Sri Lanka and the implications for arboviral disease transmission. PLoS. One 2014, 9, e104977. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Laheetharan, A.; Senthilnanthanan, M.; Ramasamy, R. Adaptation of Aedes aegypti to salinity: Characterized by larger anal papillae in larvae. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2018. 55(3), 235-238. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Thiruchenthooran, V.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Eswaramohan,T.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Naguleswaran, A.; Uzest, M.; Cayrol, B.; Voisin, S.N.; et al. Transcriptomic, proteomic and ultrastructural studies on salinity-tolerant Aedes aegypti in the context of rising sea levels and arboviral disease epidemiology. BMC. Genomics 2021, 22(1), 253. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N. Mosquito vectors developing in atypical anthropogenic habitats: Global overview of recent observations, mechanisms and impact on disease transmission. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2016, 53(2), 91-98.

- Ramasamy, R. Adaptation of freshwater mosquito vectors to salinity increases arboviral disease transmission risk in the context of anthropogenic environmental changes. In: Shapshak, P.; Sinnott, J.T.; Somboonwit, C.; Kuhn, J.H. editors. Global Virology I - Identifying and Investigating Viral Diseases. New York City (NY): Springer; 2015. pp. 45–54.

- Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N.; Jude, P.J.; Dharshini, S.; Vinobaba, M. Adaptation of mosquito vectors to salinity and its impact on mosquito-borne disease transmission in the South and Southeast Asian tropics. In: Morand, S.; Dujardin, J.P.; Lefait, R.; Apiwathnasorn, C. editors. Socio-Ecological Dimensions of Infectious Diseases in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Springer; 2015. pp 107–122.

- Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N. Possible impact of rising sea levels on vector-borne infectious diseases. BMC. Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 18. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S. Global climate change and its potential impact on disease transmission by salinity-tolerant mosquito vectors in coastal zones. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 198. [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Tissera, H.; Ooi, E.E.; Coloma, J.; Scott, T.W.; Gubler,. D.J. Preventing dengue epidemics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103(2), 570-571.

- Gavi, S.; Tapera, O.; Mberikunashe, J.; Kanyangarara, M. Malaria incidence and mortality in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of routine surveillance data. Malaria J. 2021, 20(1), 233. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.T.; Dickens, B..S.L.; Chew, L.Z.X.; Choo, E..LW.; Koo,. J.R.; Aik, J.; Ng, L.C.; Cook, A.R. Impact of sars-cov-2 interventions on dengue transmission. PLoS. Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14(10), e0008719.

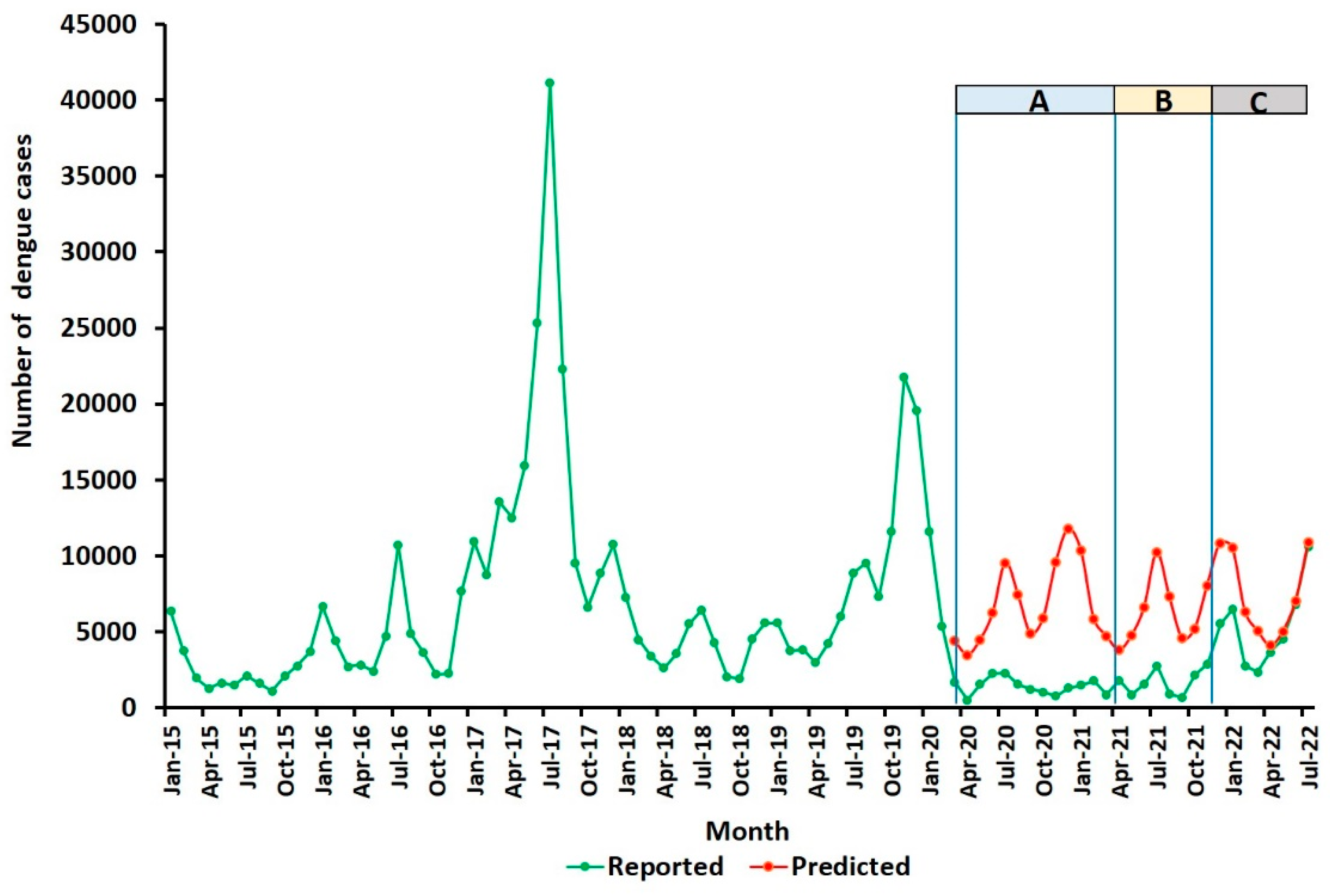

- Surendran, S.N.; Nagulan, R.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Arthiyan, S.; Tharsan, A.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Raveendran, S.; Kumanan, T.; Ramasamy, R. Reduced dengue incidence during the COVID-19 movement restrictions in Sri Lanka from March 2020 to April 2021. BMC. Public Health 2022, 22(1), 388. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Nagulan, R.; Tharsan, A.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Ramasamy, R. Dengue Incidence and Aedes Vector collections in relation to COVID-19 population mobility restrictions. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7(10), 287. [CrossRef]

- Niriella, M.A.; Ediriweera, D.S.; De Silva, A.P.; Premarathna, B..H.R.; Jayasinghe, S.; de Silva, H.J. Dengue and leptospirosis infection during the coronavirus 2019 outbreak in Sri Lanka. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115(9), 944-946. [CrossRef]

- Ariyaratne, D.; Gomes, L.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Kuruppu, H.; Kodituwakku, L.; Jeewandara, C.; Pannila Hetti, N.; Dheerasinghe, A.; Samaraweera, S.; Ogg, G.S.; et al. Epidemiological and virological factors determining dengue transmission in Sri Lanka during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS. Glob. Public Health 2022, 2(8), e0000399. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G. The Epidemiology and Control of Malaria. Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1957.

- Paramasivan, R.; Philip Samuel, P.; Pandian, R.S. Biting rhythm of vector mosquitoes in a rural ecosystem of South India. Int. J. Mosq. Res. 2015, 2, 106–113.

- Kusumawathie, P.H.D. Larval infestation of Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus in six types of institutions in a dengue transmission area in Kandy, Sri Lanka. Dengue Bull. 2005, 29, 165–168.

- Mayilsamy, M.; Vijayakumar, A.; Veeramanoharan, R.; Rajaiah, P.; Balakrishnan, V.; Kumar, A. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown during 2020 on the occurrence of vector-borne diseases in India. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2023, 60(2), 207-210. [CrossRef]

- Wijesundere, D.A.; Ramasamy, R. Analysis of historical trends and recent elimination of malaria from Sri Lanka and its applicability for malaria control in other countries. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 212. [CrossRef]

- Jude, P.J.; Dharshini, S.; Vinobaba, M.; Surendran, S.N.; Ramasamy, R. Anopheles culicifacies breeding in brackish waters in Sri Lanka and implications for malaria control. Malar. J. 2010, 9, 106. [CrossRef]

- Jude, P.J.; Tharmasegaram, T.; Sivasubramaniyam, G.; Senthilnanthanan, M.; Kannathasan, S.; Raveendran, S.; Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N. Salinity-tolerant larvae of mosquito vectors in the tropical coast of Jaffna, Sri Lanka and the effect of salinity on the toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis to Aedes aegypti larvae. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 269. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Jayadas, T.T.P., Tharsan, A.; Thiruchenthooran, V.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Raveendran, S.; Ramasamy, R. Anopheline bionomics, insecticide resistance and transnational dispersion in the context of controlling a possible recurrence of malaria transmission in Jaffna city in northern Sri Lanka. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13(1), 156. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086173 (accessed 15 January 2024).

- Surendran, S.N.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Gajapathy, K.; Arthiyan, S.; Jayadas, T.T..P; Karvannan, K.; Raveendran, S.; Karunaratne S.H.P.P.; Ramasamy, R. Genotype and biotype of invasive Anopheles stephensi in Mannar Island of Sri Lanka. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.N.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Sivasingham, A.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Karvannan, K.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Gajapathy, K.; Senthilnanthanan, M.; Karunaratne, S.H.P.P.; Ramasamy, R. Anthropogenic factors driving recent range expansion of the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 53. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html (accessed 15 January 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tick- and Louse-Borne Relapsing Fever. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/index.html (accessed 15 January 2024).

- Boulanger, N.; Boyer, P.; Talagrand-Reboul, E.; Hansmann ,Y. Ticks and tick-borne diseases. Med. Mal. Infect.. 2019, 49(2), 87-97.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the second national conference on serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR. 1995, 44(31), 590–591.

- Mead, P.; Petersen, J.;, Hinckley, A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR. 2019, 68(32), 703. [CrossRef]

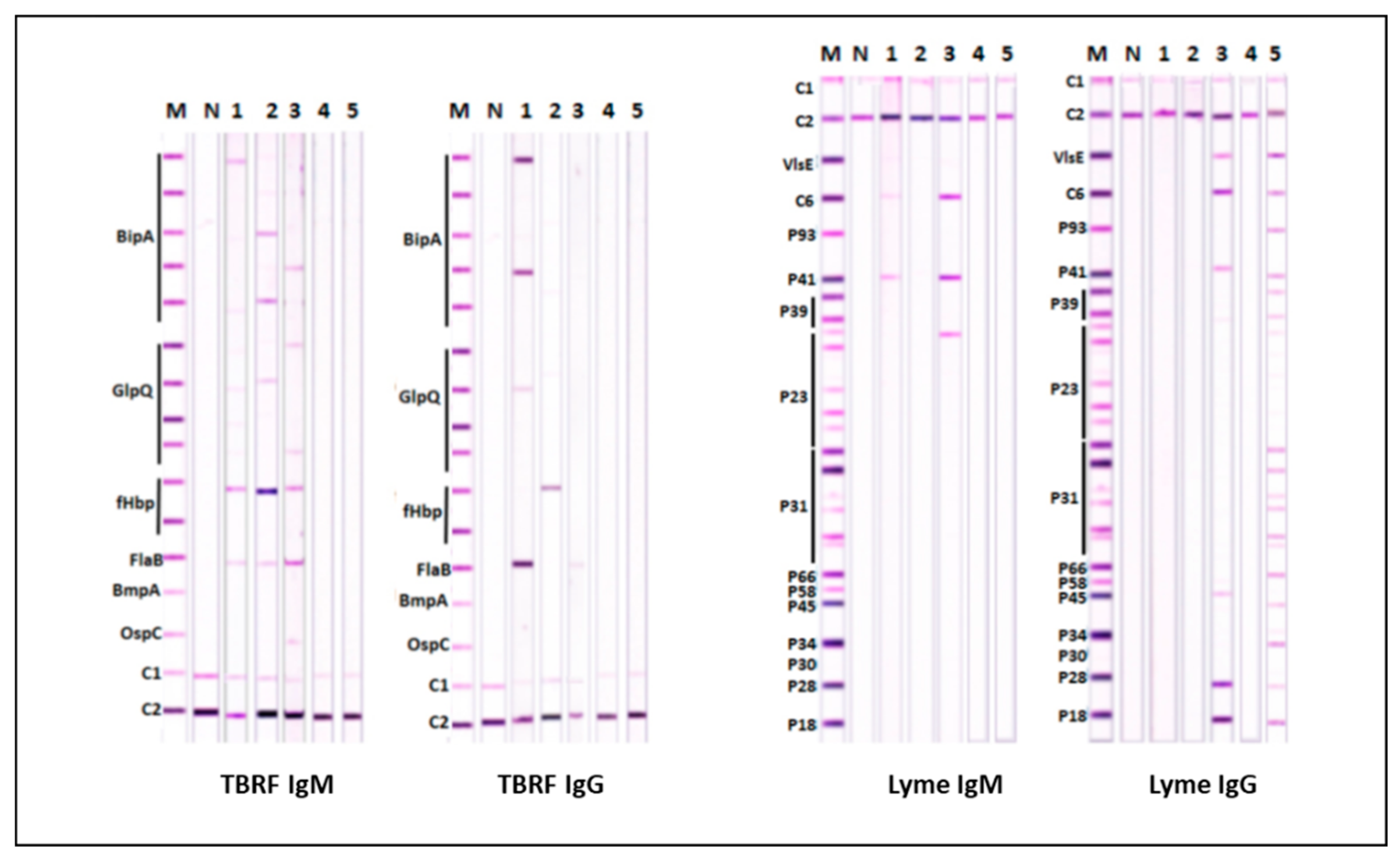

- Liu, S.; Cruz, I.D.; Ramos, C.C.; Taleon, P.; Ramasamy, R.; Shah, J. Pilot study of immunoblots with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi antigens for laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease. Healthcare (Basel) 2018, 6(3), 99. [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.S.; Liu, S.; Du Cruz, I.; Poruri, A.; Maynard, R.; Shkilna, M.; Korda, M.; Klishch, I.; Zaporozhan, S.; Shtokailo, K.; et al. Line immunoblot assay for tick-borne relapsing fever and findings in patient sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA. Healthcare (Basel) 2019, 7(4), 121. [CrossRef]

- Kugeler, K.J.; Schwartz, A.M.; Delorey, M.J.; Mead, P.S.; Hinckley, A.F. Estimating the frequency of Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27(2), 616-619. [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.R.; Strle, F.; Wormser, G.P. Comparison of Lyme disease in the United States and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27(8), 2017-2024. [CrossRef]

- Glauser, W. Combatting Lyme disease myths and the "chronic Lyme industry". CMAJ 2019, 191(40), E1111-E1112. Erratum in: CMAJ 2019, 191(50), E1389.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 17 January 2024).

- Ramasamy, M.N.; Minassian, A.M.; Ewer, K.J.; Flaxman, A.L.; Folegatti,. PM.; Owens, D.R.; Voysey, M.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Babbage, G.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2021, 396(10267), 1979-1993.

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22(9), 1293-1302. [CrossRef]

- Yamana, T.K.; Galanti, M.; Pei, S.; Di Fusco, M.; Angulo, F.J.; Moran, M.M.; Khan, F.; Swerdlow, D.L.; Shaman, J. The impact of.

- COVID-19 vaccination in the US: Averted burden of SARS-CoV-2-related cases, hospitalizations and deaths. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0275699.

- Haas, E.J.; McLaughlin, J.M.; Khan, F.; Angulo, F.J.; Anis, E.; Lipsitch, M.; et al. Infections, hospitalisations, and deaths averted via a nationwide vaccination campaign using the Pfizer–BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in Israel: A retrospective surveillance study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 357–366.

- Bonnevie E, Goldbarg J, Gallegos-Jeffrey AK, Rosenberg SD, Wartella E, Smyser J. Content themes and influential voices within vaccine opposition on Twitter, 2019. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110(S3), S326-S330. [CrossRef]

- Nature Editorial. How online misinformation exploits 'information voids' - and what to do about it. Nature 2024, 625(7994), 215-216. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R. Nasal conditioning of inspired air, innate immunity in the respiratory tract and SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/4j95b (accessed 14 January 2024).

- Ramasamy, R. Perspective of the relationship between the susceptibility to initial SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and optimal nasal conditioning of inhaled air. Int. J. Mol .Sci. 2021, 22(15), 7919.

- Ramasamy R. Innate and adaptive immune responses in the upper respiratory tract and the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2022, 14(5), 933.

- Aquino, Y.; Bisiaux, A.; Li, Z.; O'Neill, M.; Mendoza-Revilla, J.; Merkling, S.H.; Kerner, G.; Hasan, M.; Libri, V.; Bondet, V.; et al. Dissecting human population variation in single-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2023, 621(7977), 120-128.

- Ramasamy R. COVID-19 vaccines for optimizing immunity in the upper respiratory tract. Viruses 2023, 15(11), 2203. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Differences | Cited References |

|---|---|---|

| LC50 for salt | Significantly higher LC50 in BW Ae. aegypti for the L1 and L3 to adult transition. An inheritable characteristic | [10,15,23] |

| Osmoregulatory anal papillae in L3 larvae |

Significantly larger anal papillae in BW Ae. aegypti. An inheritable characteristic | [24] |

| Gene expression in mid-L4 larvae |

Marked differences, particularly in genes for cuticle proteins, and others associated with cuticle synthesis | [25] |

| Protein composition of L4 cuticles | Marked differences compatible with the gene expression data | [25] |

| Cuticle structure by TEM | Thicker cuticles in L4 larvae and adult abdomen with more prominent endocuticles and exocuticles in BW Ae. aegypti | [25] |

| Surfaces of shed L3 and L4 cuticles | More pronounced surface undulations in BW Ae. aegypti cuticles by AFM and SEM | [15] |

| Egg sizes | Significantly smaller eggs in BW Ae. aegypti | [15] |

| Surfaces of eggs by AFM and SEM | BW Ae. aegypti egg surfaces were significantly less elastic by AFM, with more undulating surfaces seen by AFM and SEM | [15] |

| Hatchability of eggs and preimaginal development to adults | Hatchability of eggs laid and preimaginal development to adults by FW Ae. aegypti is decreased in 10 gL-1 salt BW. These properties were maternally inherited in genetic crosses | [15] |

| Susceptibility of L3 and L4 to the common larvicide Temephos | BW Ae. aegypti were significantly more resistant than FW Ae. aegypti in a 24h assay |

[15] |

| L1-L4: first to fourth instar larval stages, AFM: atomic force microscopy, SEM: scanning electron microscopy, TEM: transmission electron microscopy, LC50: concentration producing 50% lethality | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).