Submitted:

26 January 2024

Posted:

26 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental part

2.1. Reagents and characterization

2.2. Synthesis of Mg-MOF-74

2.3. Evaluation of adsorbents

2. Results and discussion

3. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Xin, C.L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Z.F.; Liu, L.L.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.M. Enhancement of Hydrothermal Stability and CO2 Adsorption of Mg-MOF-74/MCF Composites. Acs Omega 2021, 6, 7739–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Jones, C.W. Adsorbent Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Large Anthropogenic Point Sources. Chemsuschem 2009, 2, 796–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bollini, P.; Didas, S.A.; Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Jones, C.W. Structural Changes of Silica Mesocellular Foam Supported Amine-Functionalized CO2 Adsorbents Upon Exposure to Steam. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 2010, 2, 3363–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comotti, A.; Fraccarollo, A.; Bracco, S.; Beretta, M.; Distefano, G.; Cossi, M.; Marchese, L.; Riccardi, C.; Sozzani, P. Porous dipeptide crystals as selective CO2 adsorbents: Experimental isotherms vs. grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations and MAS NMR spectroscopy. Crystengcomm 2013, 15, 1503–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, M.H.; de Croon, M.H.J.M.; van der Schaaf, J.; Cobden, P.D.; Schouten, J.C. Kinetic and structural requirements for a CO2 adsorbent in sorption enhanced catalytic reforming of methane-Part I: Reaction kinetics and sorbent capacity. Fuel 2012, 99, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, S.S. A Chemically Functionalizable Nanoporous Material [Cu3(TMA)2(H2O)3]n. Science 1999, 283, 1148–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Mayr, F.; Gagliardi, A. Adsorption and sensing properties of SF6 decomposed gases on Mg-MOF-74. Solid State Communications 2023, 363, 115120–115124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.H.; Ullah, S.; Chen, X.; Ma, J.X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Luo, G.S. Selective adsorption of liquid long-chain α-olefin/paraffin on Mg-MOF-74: Adsorption behavior and interaction mechanism. Nano Research 2023, 16, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, A.; Mouchaham, G.; Bhatt, P.M.; Liang, W.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Adil, K.; Jamal, A.; Eddaoudi, M. Advances in Shaping of Metal–Organic Frameworks for CO2 Capture: Understanding the Effect of Rubbery and Glassy Polymeric Binders. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2018, 57, 16897–16902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alezi, D.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Suyetin, M.; Bhatt, P.M.; Weselinski, L.J.; Solovyeva, V.; Adil, K.; Spanopoulos, I.; Trikalitis, P.N.; Emwas, A.H.; et al. MOF Crystal Chemistry Paving the Way to Gas Storage Needs: Aluminum-Based soc-MOF for CH4,O2, and CO2 Storage. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 13308–13318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREAMER, A.E.; GAO, B. Carbon-Based Adsorbents for Postcombustion CO2 Capture: A Critical Review. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50, 7276–7289. [Google Scholar]

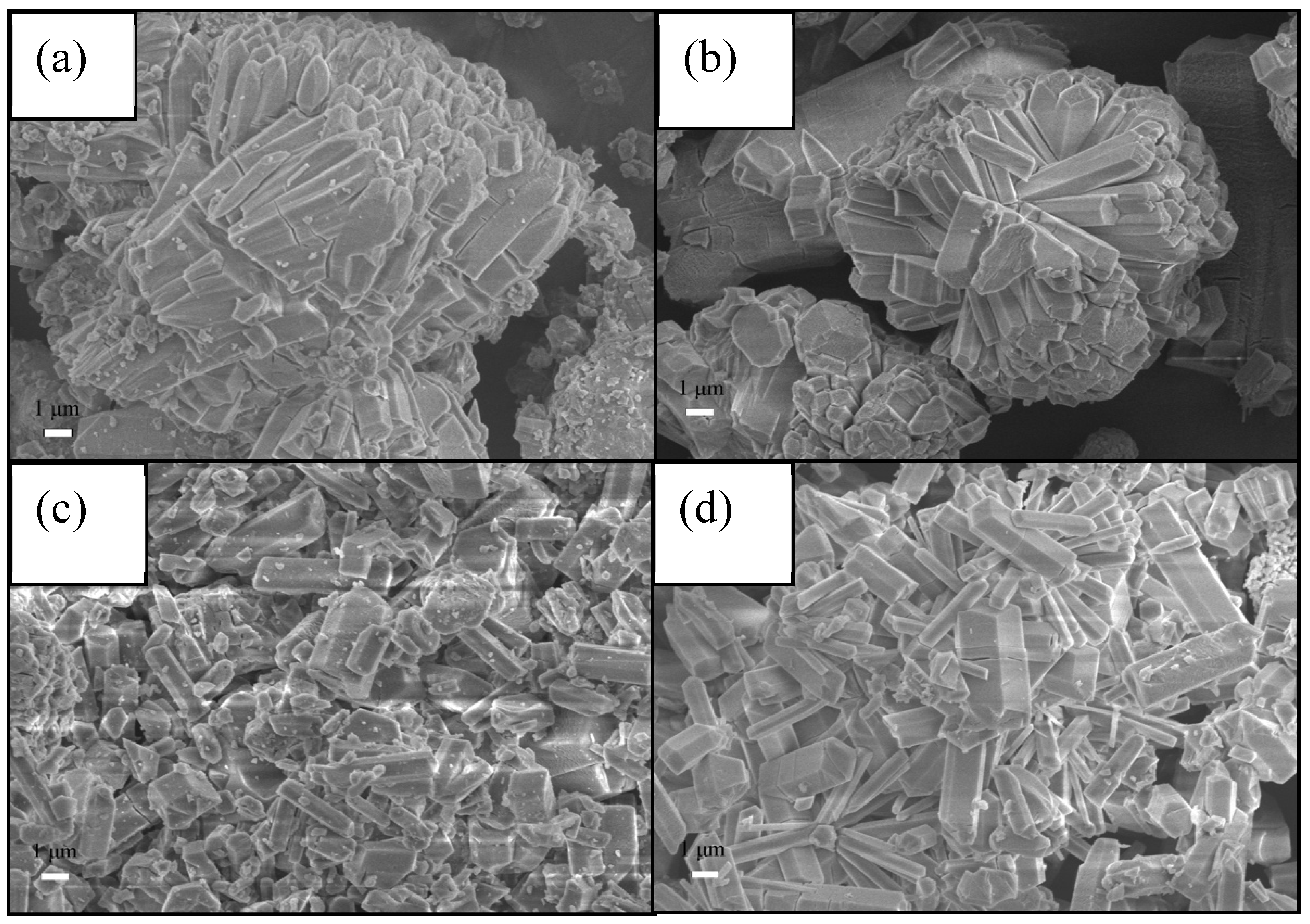

- Hu, J.Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.X. Controlled syntheses of Mg-MOF-74 nanorods for drug delivery. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2021, 294, 121853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, B.X.; Zhou, L.J.; Xia, Z.F.; Feng, N.J.; Ding, J.; Wang, L.; Wan, H.; Guan, G.F. Synthesis of Hierarchically Structured Hybrid Materials by Controlled Self-Assembly of Metal Organic Framework with Mesoporous Silica for CO2 Adsorption. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 23060–23071. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.P.; Cui, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.M.; Zhang, J.F.; Shu, X.; Liu, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.C. Porous HKUST-1 derived CuO/Cu2O shell wrapped Cu(OH)2 derived CuO/Cu2O core nanowire arrays for electrochemical nonenzymatic glucose sensors with ultrahigh sensitivity. Applied Surface Science 2018, 439, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.A.; Cho, H.Y.; Kim, J.; Yang, S.T.; Ahn, W.S. CO2 capture and conversion using Mg-MOF-74 prepared by a sonochemical method. Energy & Environmental Science 2012, 5, 6465. [Google Scholar]

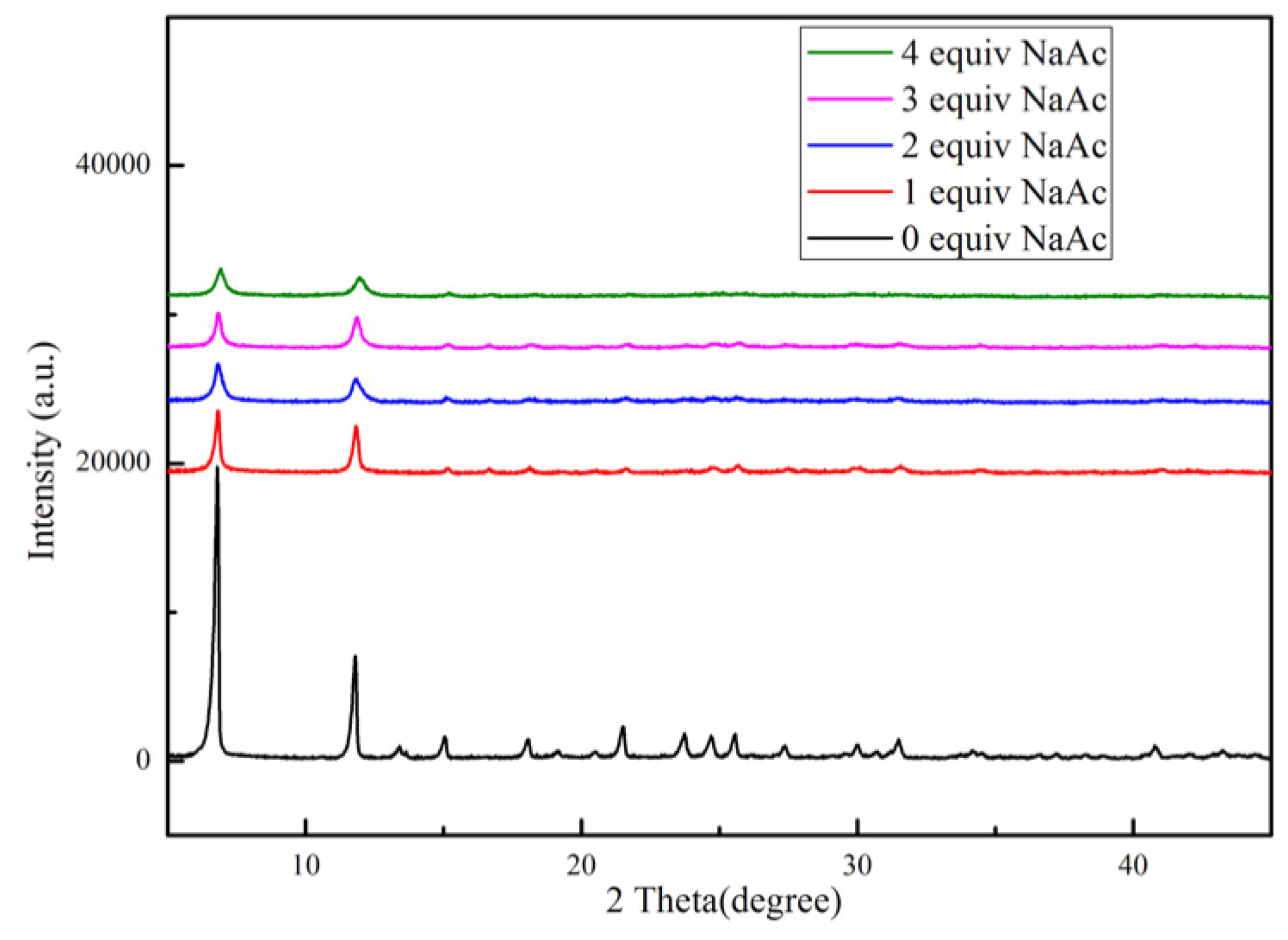

- Yao, Z.Y.; Guo, J.H.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Guo, F.; Sun, W.Y. Controlled synthesis of micro/nanoscale Mg-MOF-74 materials and their adsorption property. Mater. Lett. 2018, 223, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.Q.; Liu, X.C.; Zhao, X.F.; Yu, S.M.; Yuan, Z.P.; Liu, S.J.; Yi, X.B. Hierarchically Porous Mg-MOF-74/Sodium Alginate Composite Aerogel for CO2 Capture. Acs Applied Nano Materials 2023, 6, 16694–16701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Zhan, H.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Effect of various alkaline agents on the size and morphology of nano-sized HKUST-1 for CO2 adsorption. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 27901–27911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Jiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhan, H.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Wei, W. Enhanced CO2 Adsorption Capacity and Hydrothermal Stability of HKUST-1 via Introduction of Siliceous Mesocellular Foams (MCFs). Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2016, 55, 7950–7957. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A.; Maji, T.K. Mg-MOF-74@SBA-15 hybrids: Synthesis, characterization, and adsorption properties. Apl Materials 2014, 2, 124107–124113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.F.; Chen, Y.N.; Gong, M.; Chen, A.J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.T.; Liu, Y.; Dan, N.H.; Li, Z.J. Core-shell structure Mg-MOF-74@MSiO2 with mesoporous silica shell having efficiently sustained release ability of magnesium ions potential for bone repair application. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2023, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.F.; Tian, W.J.; Lu, X.; Yuan, H.M.; Yang, L.Y.; Zhang, H.; Shen, H.M.; Bai, H. Boosting the CO2 adsorption performance by defect-rich hierarchical porous Mg-MOF-74. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

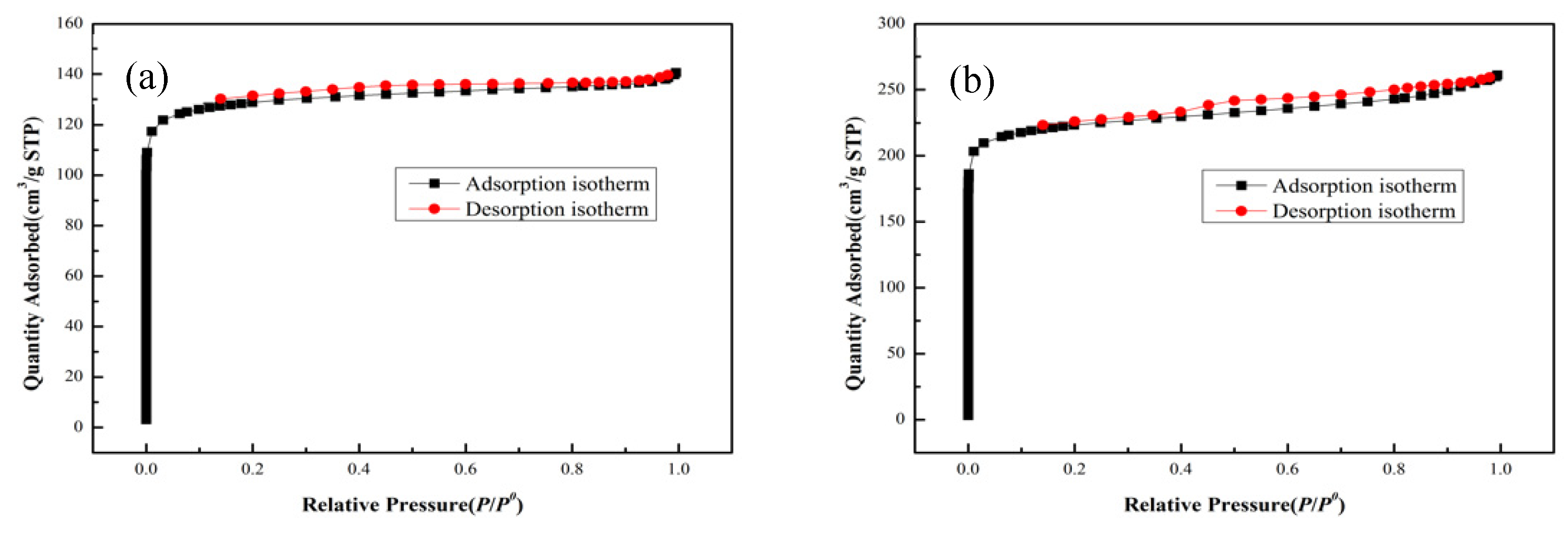

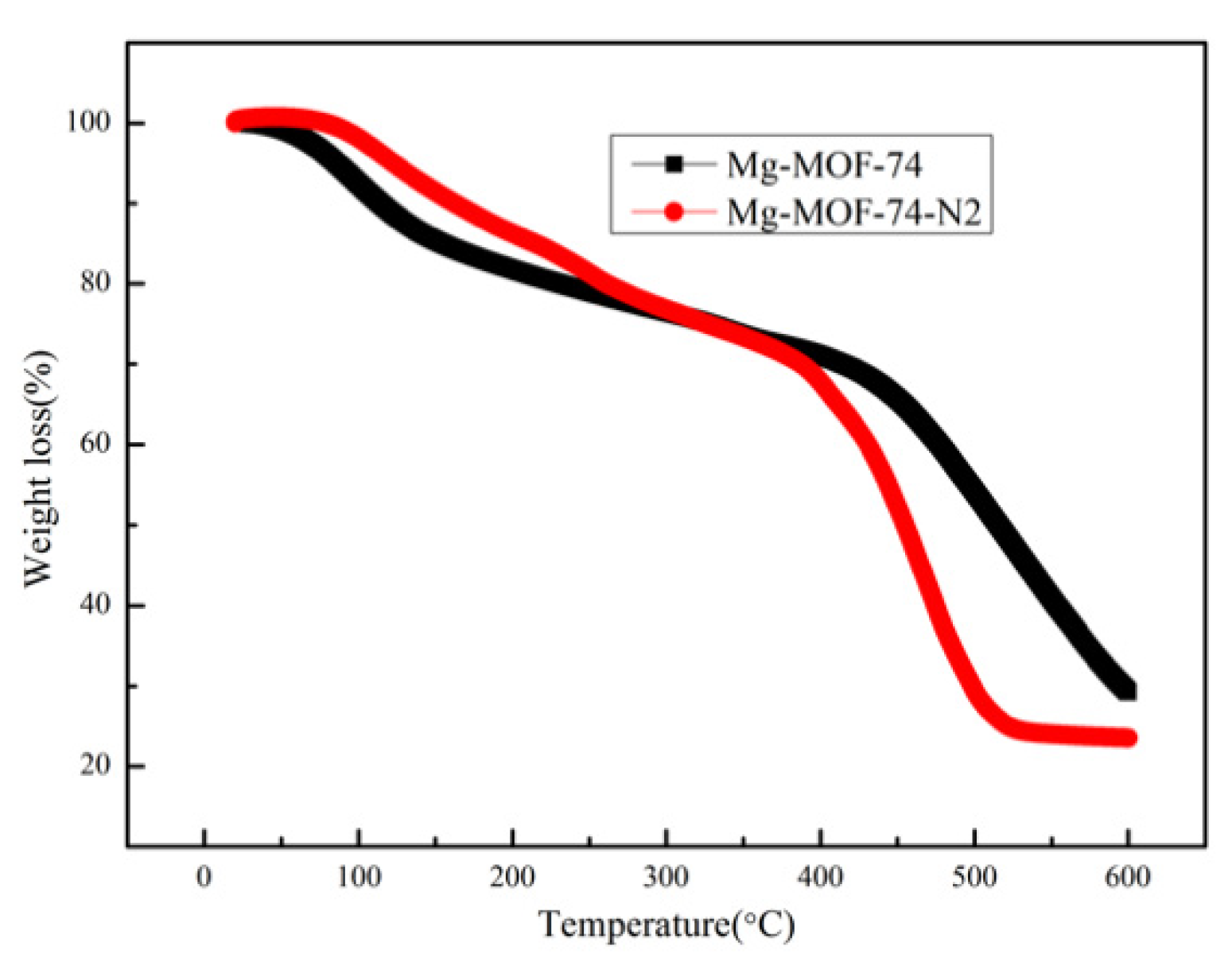

| Samples | Specific area(m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | Pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-MOF-74 | 570.3 | 0.218 | 0.91 |

| Mg-MOF-74-N2 | 624.7 | 0.264 | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).