1. Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions are causing anthropogenic climate change or global warming which is a challenge for human beings in this century and needs to be addressed [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Among technological approaches, adsorption technologies by using solid adsorbents which include natural calcium materials [

6], MOFs, zeolites, and activated carbons [

7,

8], have been considered as promising solutions to mitigate CO

2 due to their low energy requirement, simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and scalability [

9,

10]. Of the solid adsorbents, activated carbons synthesized from biomass with high surface areas are gaining attention for their low cost, high surface area, high porosity, and large-scale application potentials [

11,

12].

Basic groups (amine groups) are known to enhance the structural,

alkalinity, and chemical properties and adsorption efficiency [

9,

10,

13] of activated carbons [

14]. Amine groups can be increased onto the activated carbons by wet [

14] or dry or dry impregnation methods, depending on whether aqueous or gaseous NH

3 was injected into activated carbons at different temperatures [

10,

15]. The thermal modification using NH

3 is normally known as amination and the temperature ranges are normally from 200

oC to 800

oC [

15]. Through the heating process, NH

3 disbands to various free radicals such as NH

2, NH, atomic H

2, and N

2. These free radicals will then react with carbons to produce N-functionalities such as -CN, pyridinic, and pyrrolic [

15]. When ammonia impregnation is applied, it is expected that the amount of incorporated N

2 will be improved on the activated carbons [

16], this leads to also to enhance the CO

2 adsorption capacity [

9,

10,

13], since CO

2 is acidic. For instance, Zhang [

9] used

microwave irradiation under N2 atmosphere and NH

4OH impregnation to increase the CO2 adsorption up to 3.75 mmol/g at 1 atm and 20 oC [

9]. Ava Heidari [

13] used ammonia solution with heat modification to achieve the CO

2 adsorption capacity of up to 3.22 mmol/g at 1 bar and 30

oC [

13]. However, impregnating activated carbons into a basic solution or through the wet impregnation process might result in blocking pores in the structures of activated carbons [

16] and lead to the adsorption decrease [

9].

Okara powder waste, often considered food-processing waste [

17] and discarded or underutilized during soy-bean production processes, represents an environmentally friendly feedstock for activated carbon production by fast pyrolysis processes [

18,

19]. The hydrothermal process has been known as a simple method to improve activated carbon adsorption properties [

19,

20,

21]. This research aims to evaluate the impacts of ammonia aqueous solution impregnation through hydrothermal treatment at 200

oC on relatively high surface area okara powder waste activated carbons toward CO

2 adsorption capacity. The textural structures of the modified ACs derived from okara powder waste were characterized. The functional groups and composition of elements of the ACs were further analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The adsorption of CO

2 on the original and modified ACs was measured, discussed, and reported in this study. By investigating this bio-waste material, the research not only addresses sustainability issues but also contributes to waste valorization [

22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instruments

Original activated carbons were prepared from pyrolysis processes with dry KOH (Xilong, China) activation. The high surface area (590 m

2/g) [

18] was obtained from a two-step carbonization and activation method. First, okara powder waste was sun-dried and oven-dried before it went through a vertical and horizontal pyrolysis setup in a N

2 flow of 1.8 L/min to obtain the biochar. Pyrolysis temperature is set at 550

oC; heating rate 3

oC/min; residence time is 1 hour; in a N

2 flow of 1.8 L/min. After that, the biochar was impregnated with dry KOH and went through washing and re-pyrolysis steps with pyrolysis temperature set at 550

oC; heating rate 3

oC/min; residence time: 1 hour before testing their BET surface area values. These steps were described in detail in a previous study [

18].

2.2. Modification of ACs

The original activated carbons have surface areas of 590 m2/g and were divided into 4 samples where sample 1 (denoted S1-original AC) remains the original activated carbon with high surface areas. Prior to the surface modification, the AC was dried in an oven (Nabertherm, Germany) at 100 oC for 24 hours and kept in a zip bag. Sample 2 (denoted sample S2-AC-NH4OH-24h) was impregnated with NH3 solution 25% (Xilong, China) in an autoclave and kept in an oven (Nabertherm, Germany) at 200 oC for 24 hours. 75 ml ammonia aqueous solution (25%, Xilong) was added to 0.5 g of the original AC, the heating rate is 3 oC/min. Sample 3 (denoted as S3-AC-NH4OH-48h) and sample 4 (denoted as S4-AC-NH4OH-72h) were activated carbons with NH3 solution 25% (Xilong, China) impregnated in an oven (Nabertherm, Germany) at 200 oC for 48 and 72 hours, respectively.

2.3. SEM-EDX

A Jeol, JCM-7000 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) was used to perform the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the samples. SEM images were captured at 3000 magnification. EDX analyses were examined with a 10 kV acceleration voltage by the same instrument.

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The surface FTIR spectra were taken with a Thermal Scientific – NICONET iS5050 FTIR (USA) instrument. The samples were dried in a vacuum desiccator (Jeio, Korea) before being mixed with KBr powder and pressed with a Specac hydraulic press (England). Data acquisition was obtained automatically from the standard software package installed in a connected computer. The samples were run after a pure KBr sample known as a baseline result. The spectrometer collected 1800 spectra in the range of 400–4000 cm−1, with a resolution of 2 cm−1.

2.5. Temperature Programmed Desorption of CO2 on ACs

TPD is a useful technique to characterize adsorbed species, to find acidic and basic sites on the surface, chemically bonded surface, or organic compound adsorbed on the surface of the sample [

23,

24]. TPD coupled to mass spectrometry(MS) instrument was provided by Micrometrics, AUTOCHEM – 2950 (GA 30093, USA). The experiments were carried out in a TPD cell placed into a stainless steel, cylindrical heating block. 100 mg of the sample was placed in a quartz reactor. The degassing process takes place within 15 min with Helium (99.99%) flow at 300 °C; heating rate of 3

oC/min and then the sample was then cooled to 50

oC s for CO

2 chemisorption in 10% CO

2/helium. Then the TPD-CO

2 temperature is increased up to 500

oC; heating rate of 10

oC/min and keep this temperature in 30 min for desorption [

23,

25,

26].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Impact on Morphology and Composition of Activated Carbons

SEM photographs of the original activated carbon and modified samples are shown in

Figure 2. It is observed from the figure that the external surface of all activated carbon samples shows some pores. Visually, the carbon samples present similar structures but the ammonia modifications also caused changes to the surface morphology. Changes can be seen in

Figure 2 (b, c, d) that the thick wall becomes opened; porosity gets wider; and SEM images in (b), and (c) have more pores and channels than the raw/original activated carbon (a) [

27] and the surface of sample (d) looks smoother [

28].

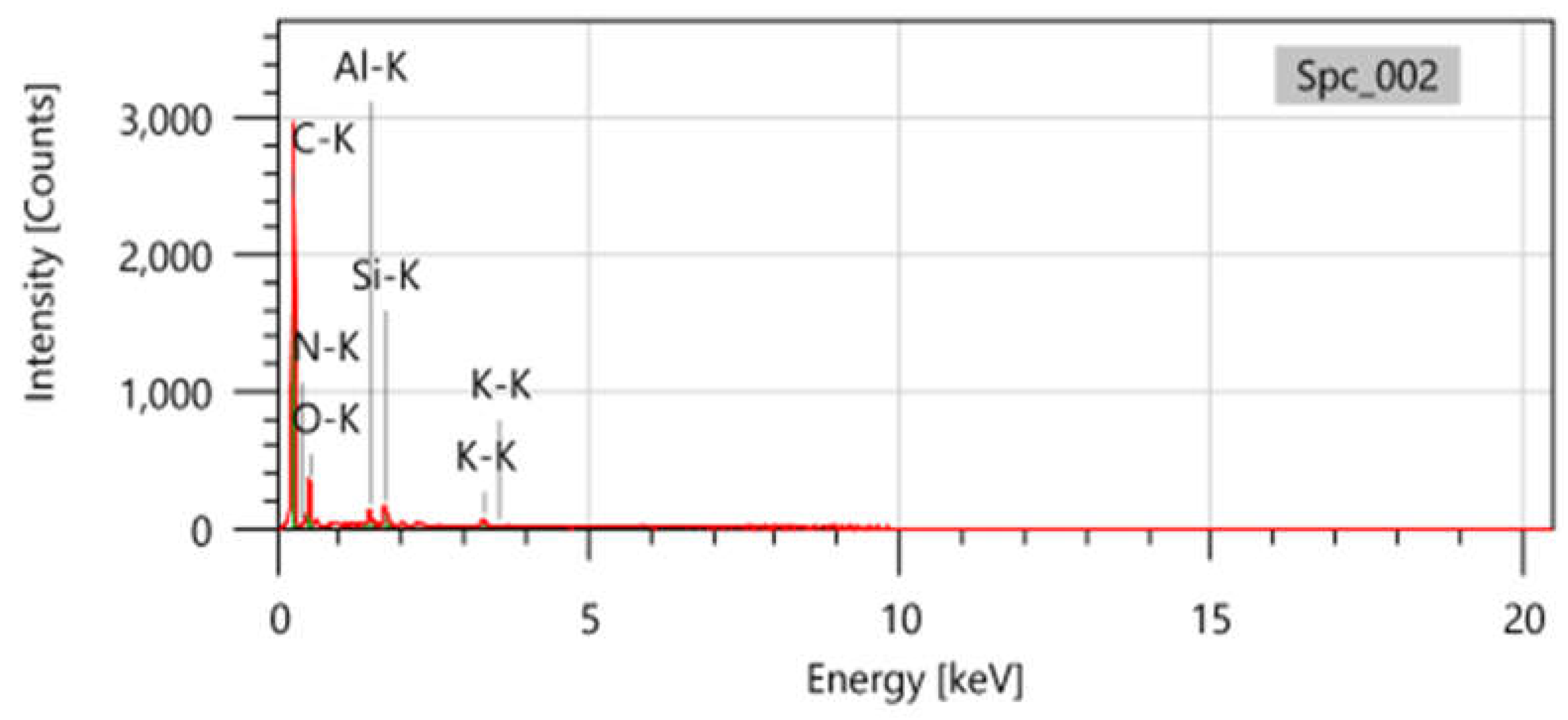

From

Table 1, we can see that there is no N in the raw AC sample. For samples S2 S3 and S4, with an increase in hydrothermal time, the N concentration in the mass of those samples are 4.34; 6.05; 1.58 (%), while the N concentration in the atom is 4.17; 5.70, and 1.16, respectively. The C/N atom ratio clearly shows that the AC modified with NH

4OH for 48h (S3) possesses the highest N content. The decrease in N concentration in sample S4 (when hydrothermal duration is 72 hours) can be due to the NH

3 desorption from pores in this sample in a too-long heating treatment process. Thus, samples S2 and S3 with a reasonable heating time (24h and 48h) may have better CO

2 adsorption ability due to higher N content. Of these 4 samples, Cl only appears in the original AC, this is possible because the Cl impurities remain from the washing step using aqueous HCl solutions of the AC preparation steps [

18].

EDX results of sample S2 are illustrated in

Figure 3. The result shows that this sample has the highest oxygenated groups compared to other samples (S1, S3, and S4). This sample also contains a Si concentration of 3.23% in mass and 1.55% in atoms, which is relatively high compared to the literature of between 0.09 and 1.21 % [

18,

29].

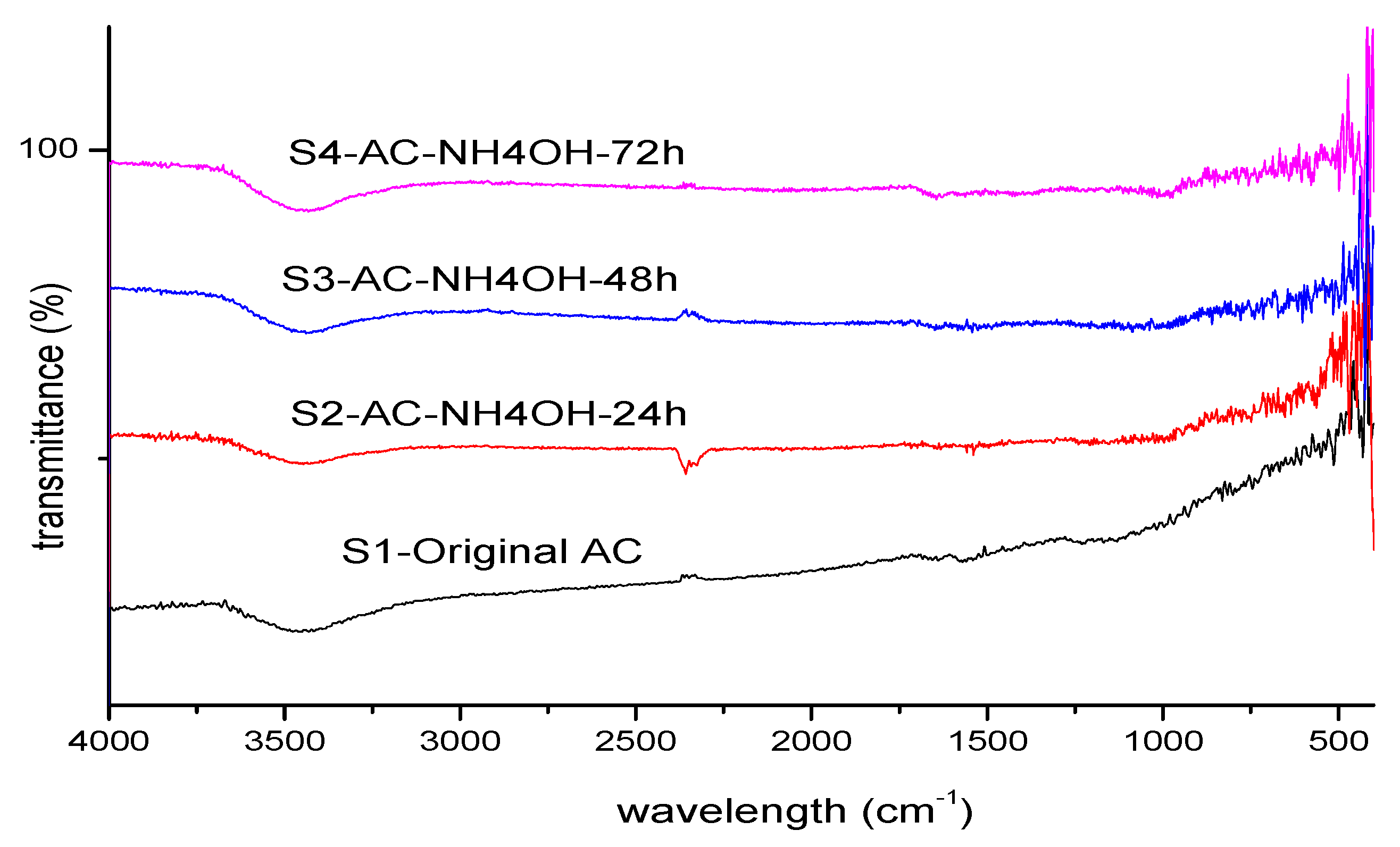

3.2. Impact on Functional Group of Activated Carbons

Functional groups and complexes inside the samples were analyzed through infrared-spectra analysis. FTIR spectra of these 4 samples are shown in

Figure 4.

Visually, FTIR analysis results of 4 investigated samples show quite similar spectra. Around the wavelength of 2358 cm

-1, corresponding to the –C = O stretch [

30,

31], a small peak appears at samples S1-Original AC, S3 -AC-NH

4OH-24 and S4-AC-NH

4OH-72. The FTIR spectra confirm the presence of N-containing groups in ammonia-modified activated carbons (samples S2 -AC-NH

4OH-24, S3-AC-NH

4OH-24, and S4-AC-NH

4OH-72). The characteristic band at the wavelength of 3432cm

−1 and 3442 cm

−1 of both treated and untreated AC spectra shown could be due to the –OH asymmetric stretching vibration or the presence of N-H groups [

18,

32,

33].

3.3. Impact on CO2 Adsorption Ability

CO

2 adsorption experiments through the break-through apparatus were carried out with samples S1-S4. The CO

2 uptake capacity of these samples was compared with previous studies as illustrated in

Table 2.

In this work, CO2 uptake capacity was calculated from the desorbed CO2 amount in the TPD CO2 measurement. The results exhibit a strong difference between the S1-original AC sample compared with the S2-AC-NH4OH-24h, S3-AC-NH4OH-48h, and with the cited literature research. Specifically, S1-original AC has much lower CO2 uptake compared to S2-AC-NH4OH-24h, and S3-AC-NH4OH-48h since these samples have been modified with NH groups. As the content of N is highest in the S3 sample as described in EDS results, this sample also has the highest CO2 uptake, which is a reasonable value compared to the CO2 uptake reported by other researchers in the literature. Thus, it can be concluded that the treatment with NH4OH for 48h is optimal for the modification of Acs to adsorb CO2.

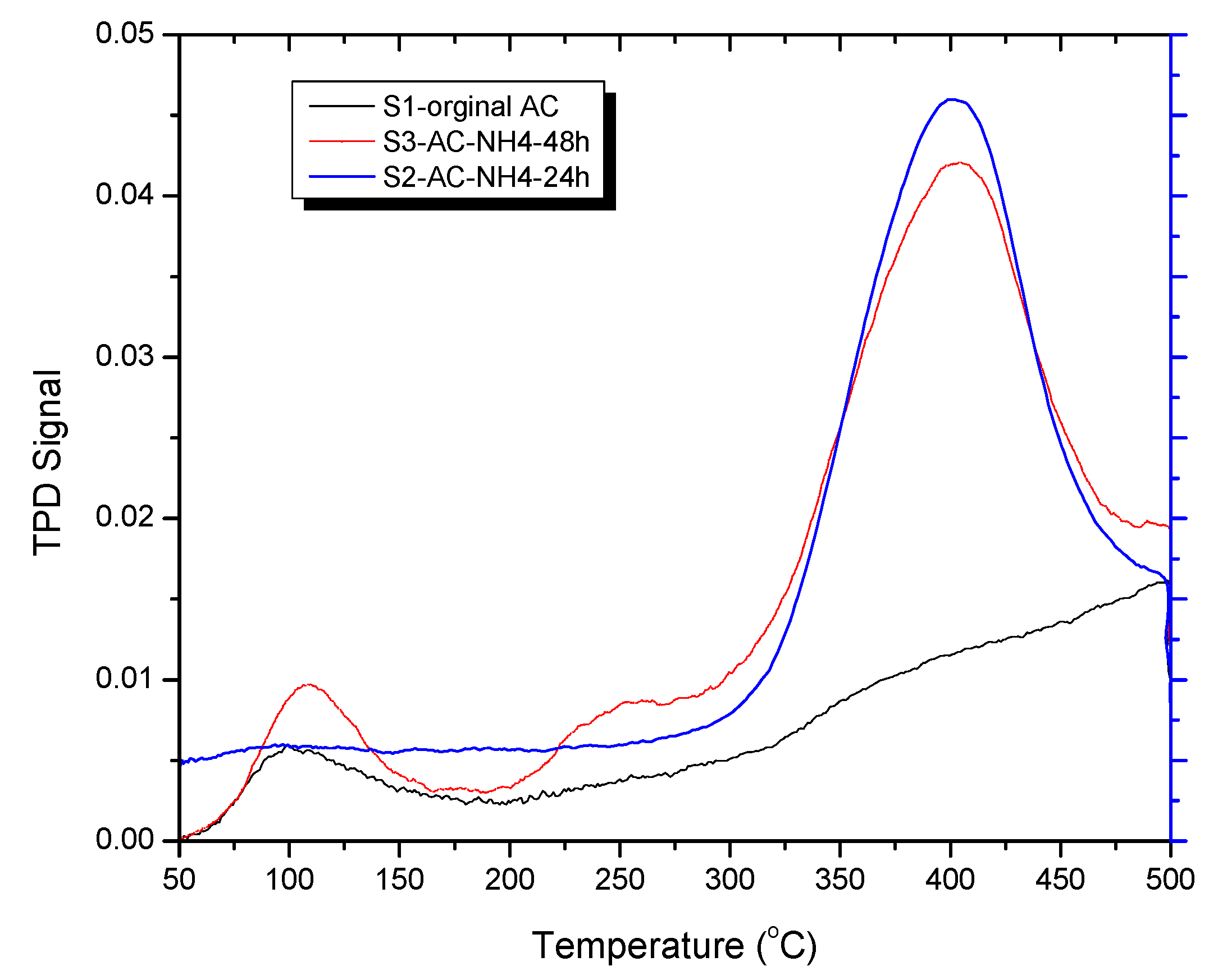

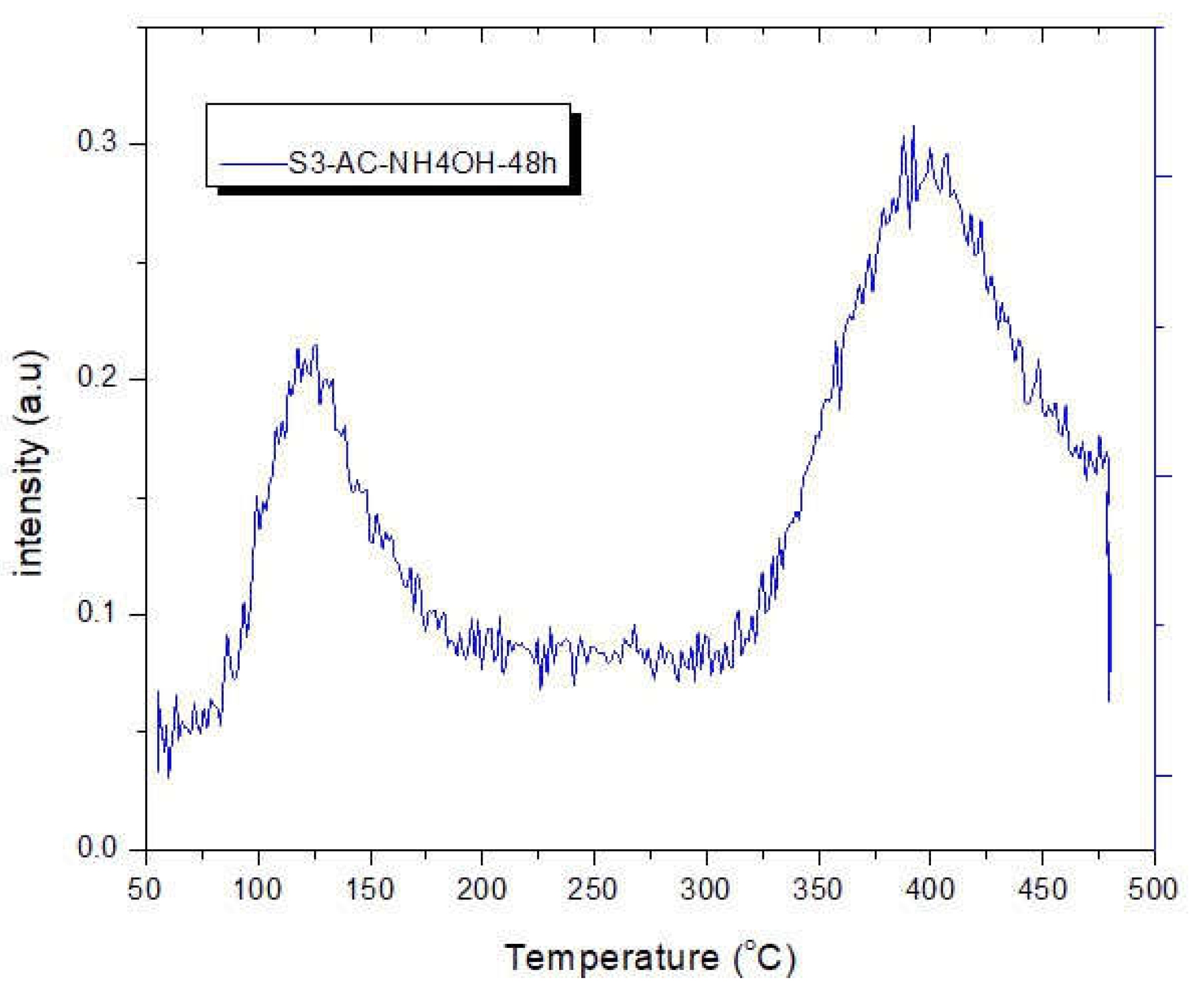

3.4. CO2 Temperature-Programmed Desorption (CO2-TPD) experimental results

The CO

2-TPD experimental results are shown in

Figure 5. From the TPD profiles, the S1-original AC has its peak in the low-temperature region (50 – 180

oC) while the S2-AC-NH

4OH-24h and the S3-AC-NH

4OH-48h has its peak in the high-temperature region (290 – 500

oC), representing that the original AC only weakly adsorb CO

2 while the modified samples strongly adsorb CO

2 so that they release CO

2 at high temperatures [

41].

Figure 5 shows that when the adsorption temperatures increased, the intensity of the peaks rose reaching the highest values at 400 °C, which is in good agreement with the literature [

42]. The CO

2- TPD for sample S1 - original AC implies at the temperature reaches 97

oC, that there was a small amount of released CO

2. For samples S2 – AC-NH

4-24h and S3-AC-NH

4OH-48 h, when the temperature gets 400

oC, there is a significant amount of released CO

2 possibly because of the desorption of CO

2 and the decomposition of other functional groups inside the samples [

28,

43,

44]. The release of CO

2 below 400 °C indicates that there are carboxylic groups prensented in the surface of the different activated carbon samples [

28].

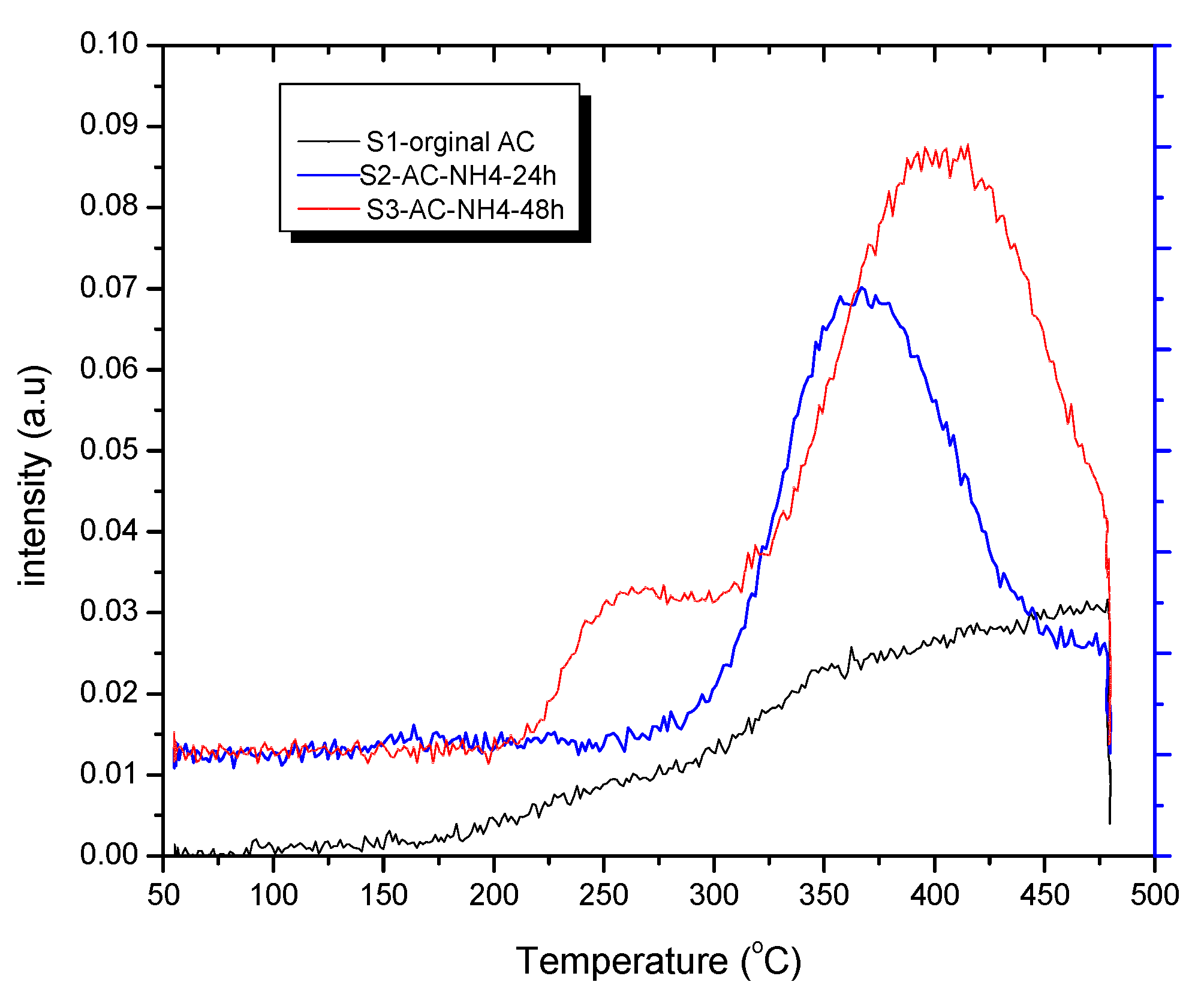

The masses of the released CO

2 and NH

3 were monitored during the TPD CO

2 measurement, according to the method described in the literature [

43]. The results of mass 44 for CO

2 are shown in

Figure 6. The changes of mass intensity with temperatures fit quite well with the TPD CO

2 profiles in the high-temperature range of the samples, showing the fact that CO

2 was released at high temperatures from 220 – 475

oC. Besides, the mass 17 of NH

3 of sample S3 was also examined as shown in

Figure 7 to see if NH

3 functionalized in AC materials is also released during the increase of the temperature. Here the signals were also observed at low-temperature regions and thus fit with the TPD CO

2 profile of the samples. Therefore, the released NH

3 contributes to the peaks at low temperatures (50 – 175

oC) in the TPD CO

2 profile of the S3 sample. NH

3 was also released at high temperatures. Thus, the modification of ACs by NH

4OH solution only resulted in a weak bond with AC.

4. Conclusions and Outlooks

Activated carbons (ACs) were derived from okara powder waste and activated by KOH for CO

2 adsorption. The surface of ACs was impregnated with ammonia aqueous solution using a hydrothermal process at 200

oC to enhance the CO

2 adsorption. The prepared activated carbon samples were characterized with SEM-EDX and FTIR. Ammonia impregnation improved the morphology of the activated carbons. The amounts of the basic groups on the carbon surfaces became more. The performance of CO

2 uptake onto okara-based activated carbons was evaluated at different hydrothermal durations. The amount of CO

2 adsorbed onto ACs increased when the hydrothermal and impregnation time increased. The findings have implications for advancing carbon capture technologies [

5] and promoting the use of agricultural byproducts [

22].

Looking forward, several new approaches can be researched to further advance this study. First, investigating a broader range of ammonia impregnation conditions such as dry ammonia impregnation and activation processes could give additional optimizations for CO2 uptake capacity. Additionally, investigating the adsorption isotherm simulation computational modeling might give new insights into the CO2 uptake mechanisms and capacity. Combining ammonia impregnation with other modification strategies, such as doping with additional heteroatoms or integrating advanced material composites, may further enhance CO2 adsorption properties. Expanding the research to various other feedstocks for activated carbon production and comparing their performance may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the material’s adsorption performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.D. Hoang; methodology, T.D. Hoang; validation, T.D. Hoang, L.M. Thang; Formal analysis, T.D. Hoang; investigation, T.D. Hoang L.M. Thang; Resources, T.D. Hoang, L.M. Thang, L.D. Dung; data curation, T.D. Hoang, L.M. Thang.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D. Hoang.; writing—review and editing, T.D. Hoang, L.M. Thang, L.D. Dung, visualization, T.D. Hoang.; supervision, L.M. Thang; project administration, L.M. Thang, L.D. Dung; funding acquisition, T.D. Hoang, L.M. Thang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Vietnam (Grant numbers: No. NDT.94.CHN/20). T.D.H. scholarship was funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD, No. 57315854. The APC was funded by MDPI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article. Data supporting reported results can be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Vietnam (Grant numbers: No. NDT.94.CHN/20). T.D.H sincerely thanks the RoHan Project funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD, No. 57315854) and to the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of Germany inside the framework of the “SDG Bilateral Graduate School program” for funding T.D.H a PhD scholarship. Tuan-Dung Hoang also would like to thank MDPI for waiving the APC fees for the publication of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mac Dowell, N.; Fennell, P.S.; Shah, N.; Maitland, G.C. The role of CO2 capture and utilization in mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandh, S.A.; Malla, F.A.; Hoang, T.D.; Qayoom, I.; Mohi-Ud-Din, H.; Bashir, S.; Betts; R.; Le, T.T.; Nguyen Le, D.T.; Linh Le, N.V.; Le, H.C. Track to reach net-zero: Progress and pitfalls. Energy Environ 2024, 0958305X241260793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.; Nghiem, N. Recent developments and current status of commercial production of fuel ethanol. Fermentation 2021, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezali, N.A.A.; Ong, H.L.; Villagracia, A.R.; Hoang, T.D. Bio-based nanomaterials for energy application: A review. Vietnam J. Chem. 2024, 62, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, F.A.; Dung, T.; Bandh, S.A.; Malla, A.A.; Wani, S.A. Circular Economy to Decarbonize Electricity. In Renewable Energy in Circular Economy, 1st ed.; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Hoang, A.T., Eds.; Springer International Publishin: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, L.C.; Teixeira, P.; Pinheiro, C.I.; Palavra, A.M.; Calvete, M.J.; Nieto de Castro, C.A.; Nobre, B.P. The Treatment of Natural Calcium Materials Using the Supercritical Antisolvent Method for CO2 Capture Applications. Processes 2024, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.; Bandh, S.A.; Malla, F.A.; Qayoom, I.; Bashir, S.; Peer, S.B.; Halog, A. Carbon-Based Synthesized Materials for CO2 Adsorption and Conversion: Its Potential for Carbon Recycling. Recycling 2023, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, N.Z.M.; Buthiyappan, A.; Raman, A.A.A.; Patah, M.F.A.; Sufian, S. Recent advances in biomass based activated carbon for carbon dioxide capture–A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 116, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Li, Z. Enhancement of CO2 adsorption on high surface area activated carbon modified by N2, H2 and ammonia. J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 160, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevida, C.; Plaza, M.G.; Arias, B.; Fermoso, J.; Rubiera, F.; Pis, J.J. Surface modification of activated carbons for CO2 capture. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 7165–7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.; Ben-Mansour, R. Adsorption breakthrough and cycling stability of carbon dioxide separation from CO2/N2/H2O mixture under ambient conditions using 13X and Mg-MOF-74. Appl. Energy. 2018, 230, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelnoor, N.; AlHajaj, A.; Khaleel, M.; Vega, L.F.; Abu-Zahra, M.R. Activated carbons from biomass-based sources for CO2 capture applications. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, A.; Younesi, H.; Rashidi, A.; Ghoreyshi, A.A. Evaluation of CO2 adsorption with eucalyptus wood based activated carbon modified by ammonia solution through heat treatment. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 254, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholidoust, A.; Atkinson, J.D.; Hashisho, Z. Enhancing CO2 adsorption via amine-impregnated activated carbon from oil sands coke. Energy & Fuels 2017, 31, 1756–1763. [Google Scholar]

- Abd, A.A.; Othman, M.R.; Kim, J. A review on application of activated carbons for carbon dioxide capture: present performance, preparation, and surface modification for further improvement. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021, 28, 43329–43364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przepiórski, J.; Skrodzewicz, M.; Morawski, A.W. High temperature ammonia treatment of activated carbon for enhancement of CO2 adsorption. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 225, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.Y.; Wang, R.; Thakur, K.; Ni, Z.J.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Hu, F.; Zhang, J.G.; Wei, Z.J. Evolution of okara from waste to value added food ingredient: An account of its bio-valorization for improved nutritional and functional effects. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021, 116, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.; Liu, Y.; Le, M.T. Synthesis and Characterization of Biochars and Activated Carbons Derived from Various Biomasses. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Bianasari, A.; Khaled, M.S.; Hoang, T.D.; Reza, M.S.; Bakar, M.S.A.; Azad, A.K. Influence of combined catalysts on the catalytic pyrolysis process of biomass: A systematic literature review. Energy Convers. Manag, 1184. [Google Scholar]

- Adame-Pereira, M.; Durán-Valle, C.J.; Le, M.T. Hydrothermal Carbon Coating of an Activated Carbon—A New Adsorbent. Molecules 2023, 28, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.K.; Singh, L.P.; Chaudhary, M.; Le, M.T. A novel approach to develop activated carbon by an ingenious hydrothermal treatment methodology using Phyllanthus emblica fruit stone. J. Clean. Prod, 1256. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, T.D.; Van Anh, N.; Yusuf, M.; Ali S. A, M.; Subramanian, Y.; Hoang Nam, N.; Minh Ky, N.; Le, V.G.; Thi Thanh Huyen, N.; Abi Bianasari, A.; K Azad, A. Valorization of Agriculture Residues into Value-Added Products: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Studies. Chem. Rec. 2024, e202300333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtelesis, M.; Kousi, K.; Kondarides, D.I. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over La2O3-promoted CuO/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts: a kinetic and mechanistic study. Catalysts 2020, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimbeu, C.M.; Gadiou, R.; Dentzer, J.; Schwartz, D.; Vix-Guterl, C. Influence of surface chemistry on the adsorption of oxygenated hydrocarbons on activated carbons. Langmuir 2010, 26, 18824–18833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.H.; Ruckenstein, E. Temperature-programmed desorption of CO adsorbed on NiO/MgO. Journal of Catalysis 1996, 163, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Lobban, L.L.; Mallinson, R.G. Experimental investigations on the interaction between plasmas and catalyst for plasma catalytic methane conversion (PCMC) over zeolites. In Studies in surface science and catalysis, 2nd ed.; Liu, C.J., Lobban, L.L., Mallinson, R.G., Eds.; Elsevier: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 1998; Volume 119, pp. 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Almoneef, M.M.; Jedli, H.; Mbarek, M. Experimental study of CO2 adsorption using activated carbon. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 065602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouma, I.; Jeguirim, M.; Sager, U.; Limousy, L.; Bennici, S.; Däuber, E.; Asbach, C.; Ligotski, R.; Schmidt, F.; Ouederni, A. The potential of activated carbon made of agro-industrial residues in NOx immissions abatement. Energies 2017, 10, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F.; Abd Razak, A.S.; Krishnan, S.; Sulaiman, H.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. Biochar production techniques utilizing biomass waste-derived materials and environmental applications–A review. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 7, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.H.D.; Chalimah, S.; Primadona, I.; Hanantyo, M.H.G. Physical and chemical properties of corn, cassava, and potato starchs. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Abdullah, A.H.D., Chalimah, S., Primadona, I., Hanantyo, M.H.G., Eds. 2nd ed.; IOP Publishing: Briston, UK, 2018; Vol. 160, p. 012003.

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C. Evaluate the pyrolysis pathway of glycine and glycylglycine by TG–FTIR. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2007, 80, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, E.A.; Pérez-Huertas, S.; Pérez, A.; Calero, M.; Blázquez, G. Recycling PVC Waste into CO2 Adsorbents: Optimizing Pyrolysis Valorization with Neuro-Fuzzy Models. Processes 2024, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Nyamhere, G.; Sebata, E.; Guyo, U. Kinetic and equilibrium modelling of lead sorption from aqueous solution by activated carbon from goat dung. Desalin Water Treat 2016, 57, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Côté, A.P.; Furukawa, H.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Colossal cages in zeolitic imidazolate frameworks as selective carbon dioxide reservoirs. Nature 2008, 453, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, V.; Pupier, O.; Guillot, A. Carbon dioxide-methane mixture adsorption on activated carbon. Adsorption 2006, 12, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Plaza, M.; González García, A.S.; Pevida García, C.; Pis Martínez, J.J.; Rubiera González, F. Valorisation of spent coffee grounds as CO2 adsorbents for postcombustion capture applications. Appl. Energy. 2012, 99, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ma, T.; Zhang, R.; Tian, Y.; Qiao, Y. Preparation of porous carbons with high low-pressure CO2 uptake by KOH activation of rice husk char. Fuel 2015, 139, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Narkiewicz, U.; Morawski, A.W.; Wróbel, R.J.; Michalkiewicz, B. Highly microporous activated carbons from biomass for CO2 capture and effective micropores at different conditions. J Co2 Util. 2017, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, P.; Yan, X.; Lang, J.; Peng, C.; Xue, Q. Promising porous carbon derived from celtuce leaves with outstanding supercapacitance and CO2 capture performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2012, 4, 5800–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Production of highly microporous carbons with large CO 2 uptakes at atmospheric pressure by KOH activation of peanut shell char. J. Porous Mater. 2015, 22, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeeha, A.H.; Kasim, S.O.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Abasaeed, A.E.; Al-Fatesh, A.S. Influence of nature support on methane and CO2 conversion in a dry reforming reaction over nickel-supported catalysts. Materials 2019, 12, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, D.; Song, G.; Yang, H.; Chen, L.; Sun, L.; Yang, S.; Guan, H.; Xie, X. Adsorption characteristics of gas molecules (H2O, CO2, CO, CH4, and H2) on CaO-based catalysts during biomass thermal conversion with in situ CO2 capture. Catalysts 2019, 9, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ma, X.; Zha, Q.; Kim, K.; Chen, Y.; Song, C. Maximizing the number of oxygen-containing functional groups on activated carbon by using ammonium persulfate and improving the temperature-programmed desorption characterization of carbon surface chemistry. Carbon 2011, 49, 5002–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Morlay, C.; Ahmad, R.; Joly, J.P. Assessing surface chemistry and pore structure of active carbons by a combination of physisorption (H2O, Ar, N2, CO2), XPS and TPD-MS. Adsorption 2011, 17, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimbeu, C.M.; Gadiou, R.; Dentzer, J.; Vidal, L.; Vix-Guterl, C. A TPD-MS study of the adsorption of ethanol/cyclohexane mixture on activated carbons. Adsorption 2011, 17, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).