Introduction

Trimeresurus albolabris, also known as the white-lipped pit viper, white-lipped tree viper, white-lipped bamboo pit viper, and green tree pit viper, is a venomous snake species belonging to the family Viperidae [

1]. It is a relatively small snake, with adults typically measuring around 70-90 cm in length, and is known for its distinctive appearance, with a white stripe running down the center of its upper lip [

2] (

Figure 1). This species has been reported in China, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and West Java and has become one of the most common venomous snakes with medical importance in Southeast Asia [

3].

T. albolabris is a highly venomous snake. Its bite can be dangerous to humans, causing symptoms ranging from pain and swelling to more severe ones, such as shock, spontaneous bleeding, defibrination, and other complications of thrombocytopenia and leukocytosis [

4,

5]. Notably, the venom of

T. albolabris contains metalloproteinases [

6,

7], a thrombin-like enzyme [

8], and other venom components [

5,

9].

Context

Despite its venomous nature,

T. albolabris is also an important research subject for its sexual dimorphism [

10] and geographic variation [

11]. A complete and high-quality genome of this species is crucial for studying venom proteomics, particularly for drug discovery, developing antivenom therapies, and understanding the evolution of venomous species [

12,

13,

14]. However, a complete genome of

T. albolabris has not been published yet [

15].

Here, we report the first whole genome with high continuity of a male

T. albolabris individual, collected from Mengzi, Yunnan, China. The genome was generated using single-tube long fragment read (stLFR) [

16] and whole genome sequencing (WGS) technologies. Our

T. albolabris genome had a repeat element content of 38.42% and a total size of 1.51 Gb. This new genome assembly provides valuable evidence for future studies on snake venom and the genetic underpinnings of the

Trimeresurus species.

Method

The comprehensive and sequential procedures employed in this investigation are compiled within a protocols.io compilation, with the slight adjustments delineated underneath (

Figure 2). [

17].

Sample Collection and Sequencing

In Mengzi, Yunnan, China, we captured a male T. albolabris specimen. To ensure its preservation, the specimen was promptly frozen in dry ice (at -80°C) right after collection and identification, serving both for storage and transportation purposes. Detailed procedures for DNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing are available in a protocols.io protocol collection [

17]. For RNA sequencing, we utilized the heart, stomach, liver, and kidneys, while a muscle sample was employed for stLFR and WGS sequencing. The genome assembly and annotation workflow can also be found in the corresponding protocols.io protocol [

17].

Approval for this research, encompassing sample gathering, experimental processes, and study design, was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI-IRB E22017). Throughout the investigation, scrupulous adherence to the protocols outlined by BGI-IRB was rigorously maintained, ensuring alignment with ethical and regulatory norms.

Genome Assembly, Annotation, and Assessment

The stLFR sequencing data were subjected to assembly using Supernova [

18] (v2.1.1, RRID:SCR_016756). Subsequently, the gap-filling and redundancy removal steps were performed using GapCloser [

19] (v1.12-r6, RRID:SCR_015026) and redundans [

20] (v0.14a), respectively. These processes involved utilizing the WGS data to address the gaps in the assembly and eliminate redundant sequences.

To identify repeat elements within the genome sequences, multiple genomic tools were utilized, including Tandem Repeats Finder [

21] (v. 4.09, RRID:SCR_022193), LTR_Finder [

22] (RRID:SCR_015247), RepeatModeler [

23] (v1.0.8), RepeatMasker [

24] (v. 3.3.0, RRID:SCR_015027), and RepeatProteinMask (v. 3.3.0) [

25]. Predicting protein-coding genes involved a comprehensive strategy combining de novo, homology-based, and transcript mapping approaches.

De novo gene prediction was performed using GlimmerHMM [

26] (RRID:SCR_002654). RNA-seq-based predictions began with Trimmomatic [

27] (v0.30, RRID:SCR_011848) filtering of RNA-seq data. Following the acquisition of clean RNA-seq data, Trinity [

28] (v2.13.2, RRID:SCR_013048). Finally, PASA [

29] (v2.0.2, RRID:SCR_014656) aligned transcripts against the white-lipped tree viper genome to derive gene structures. Homology-based prediction involved mapping protein sequences from the UniProt database (release-2020_05), including

Pseudonaja textilis (GCA_900518735.1),

Protobothrops mucrosquamatus (GCA_001527695.3),

Thamnophis elegans (GCA_009769535.1), and

Notechis scutatus (GCA_900518725.1) to the white-lipped tree viper genome using Blastall (v2.2.26) [

30] with an E-value cut-off of 1e-5. Then, we used GeneWise [

31] (v2.4.1, RRID:SCR_015054) to analyze the alignment results and predict gene homology. The integration of RNA-seq, homology, and

de novo predicted genes resulted in the generation of a final gene set using the MAKER pipeline (v3.01.03, RRID:SCR_005309) [

32]. This approach, incorporating multiple genomic tools and techniques, facilitated the annotation and prediction of genes in the white-lipped tree viper genome.

The functional characterization was conducted through a BLAST investigation, contrasting with various repositories such as SwissProt, TrEMBL, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), while restricting the E-value threshold to 1e-5. InterProScan [

26] (v5.52-86.0, RRID:SCR_005829) was employed to anticipate patterns and domains, along with gene ontology (GO) descriptors.

Assessing the integrity of our genome involved the utilization of Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO, v5.2.2, RRID:SCR_015008) in genome mode, employing lineage information from vertebrata_odb10 for benchmarking purposes [

33].

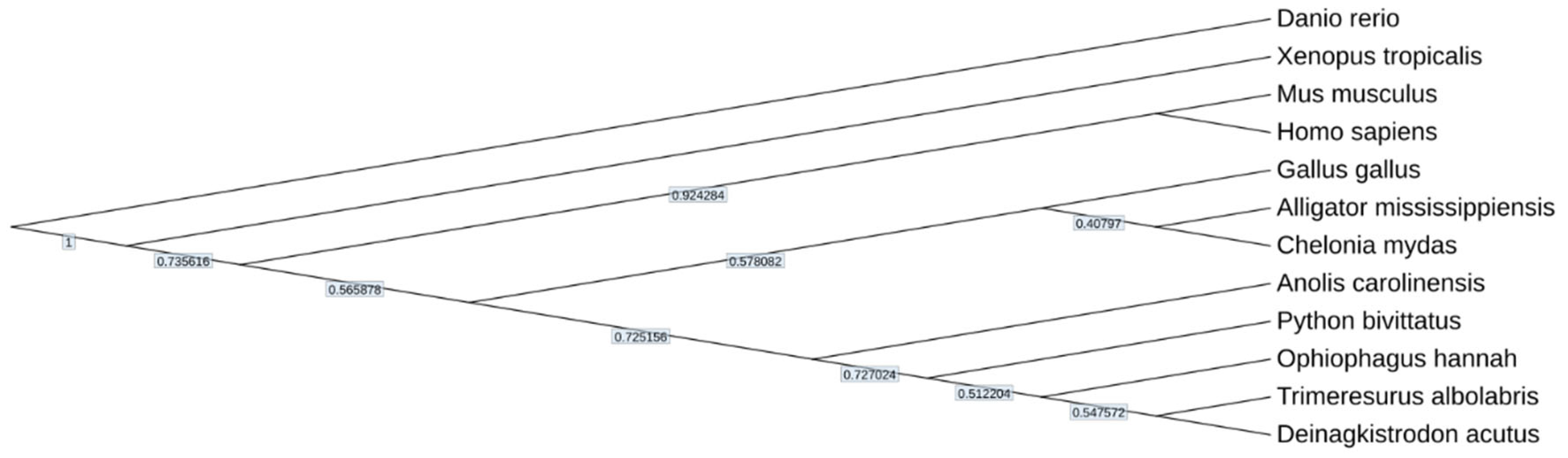

A reconstructed phylogenetic tree was generated by OrthoFinder (v2.3.7, RRID:SCR_017118) [

34], which can search for single-copy orthologs among the protein sequences of

Chelonia mydas (GCA_015237465.2),

Gallus gallus (GCA_016699485.1),

Homo sapiens (GCA_000001405.29),

Mus musculus (GCA_000001635.9),

Ophiophagus hannah (GCA_000516915.1),

Python bivittatus (GCA_000186305.2),

Xenopus tropicalis (GCA_000004195.4),

Alligator mississippiensis (GCA_000281125.4),

Danio rerio (GCA_000002035.4),

Anolis carolinensis (GCA_000090745.2),

Gopherus evgoodei (GCA_007399415.1),

Podarcis muralis (GCA_004329235.1), and

Deinagkistrodon acutus [

35].

Results

This study on snake genomics resulted in a total of 387.48 Gb of paired-end (fastq 1 and fastq 2) data, which comprised 204.61 Gb of short reads data obtained through WGS sequencing and 182.87 Gb of long reads data obtained through stLFR sequencing, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

We produced the first whole of the genomic structure for

T. albolabris, demonstrating remarkable continuity, encompassing a comprehensive genome size of 1.51 Gb, a GC content of 39.97%, and an N50 scaffold length of 381.55 kb (

Table 3). The compiled genome of T. albolabris comprises 10,016 contigs surpassing 1,000 base pairs, with a collective extension of 1.50 Gb, representing 99.14% of the overall genome length. This asset will offer substantial proof for delving into novel perspectives in the examination of

Trimeresurus viper genomics.

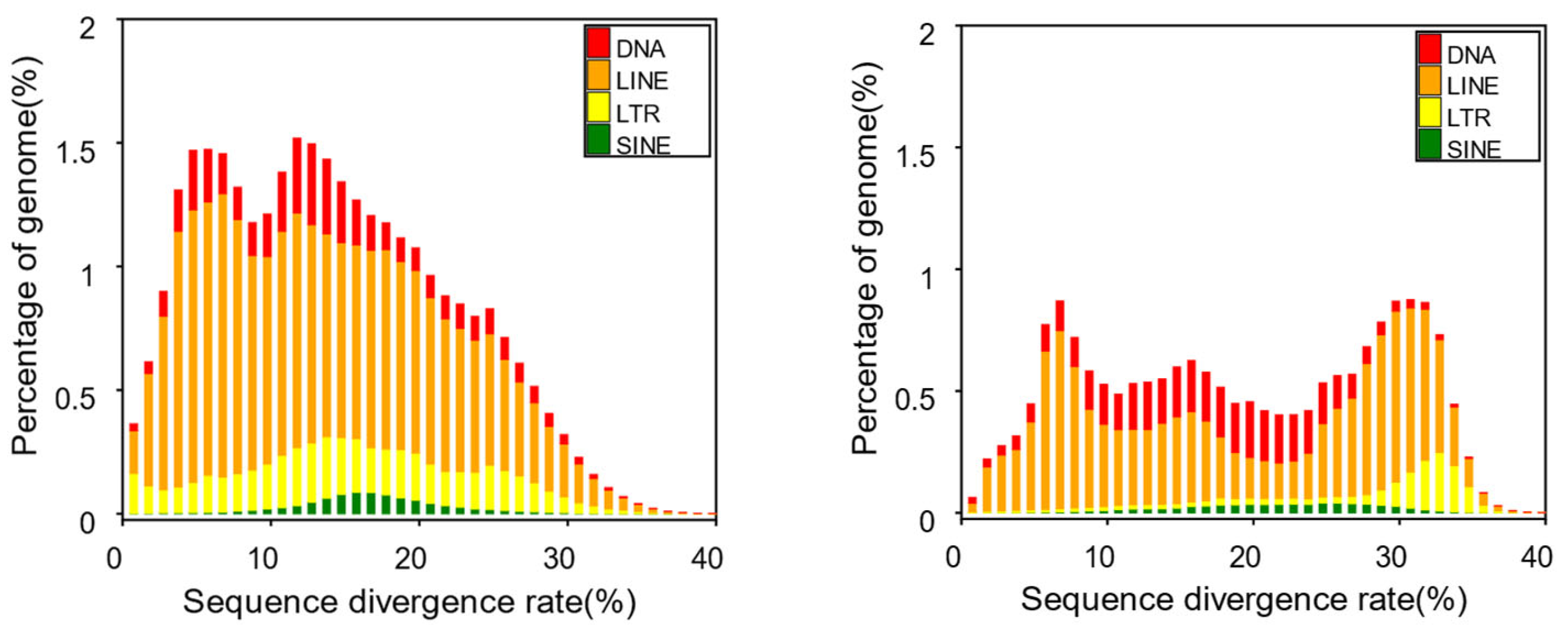

We detected repetitive elements in the

T. albolabris genome, accounting for 38.42% of the total genome. Among them, the highest proportion was occupied by long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), which accounted for 23.94% and amounted to approximately 362.35 Mb. These findings were found to be highly similar to the repetitive element content observed in previously sequenced genomes, such as those of

Thamnophis elegans (42.02%) (accession No. PRJNA561996) and

Crotalus tigris (42.31%) [

36]. This indicates that the results we obtained are highly reliable and plausible. The remaining types of transposable elements, including DNA transposons, long terminal repeats (LTRs), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), accounted for 6.90%, 5.83%, and 1.24%, respectively (

Figure 3,

Table 4, and

Table 5).

Using homology-based,

de novo, and RNA-sequencing annotation methods, we successfully identified 21,695 protein-coding genes in our

T. albolabris genome assembly. We compared our assembly to those of

Notechis scutatus (GCA_900518725.1),

Pseudonaja textilis (GCA_900518735.1), and

Thamnophis elegans (GCA_009769535.1), all of which are available from the NCBI database. Our analysis revealed no significant differences in the distribution of transcript mapping lengths, coding sequences (CDS) lengths, or the quantity of exons and introns. Additionally, our analysis predicted the presence of 250 miRNAs, 179 tRNAs, and 301 snRNAs within the

T. albolabris genome (

Table 6).

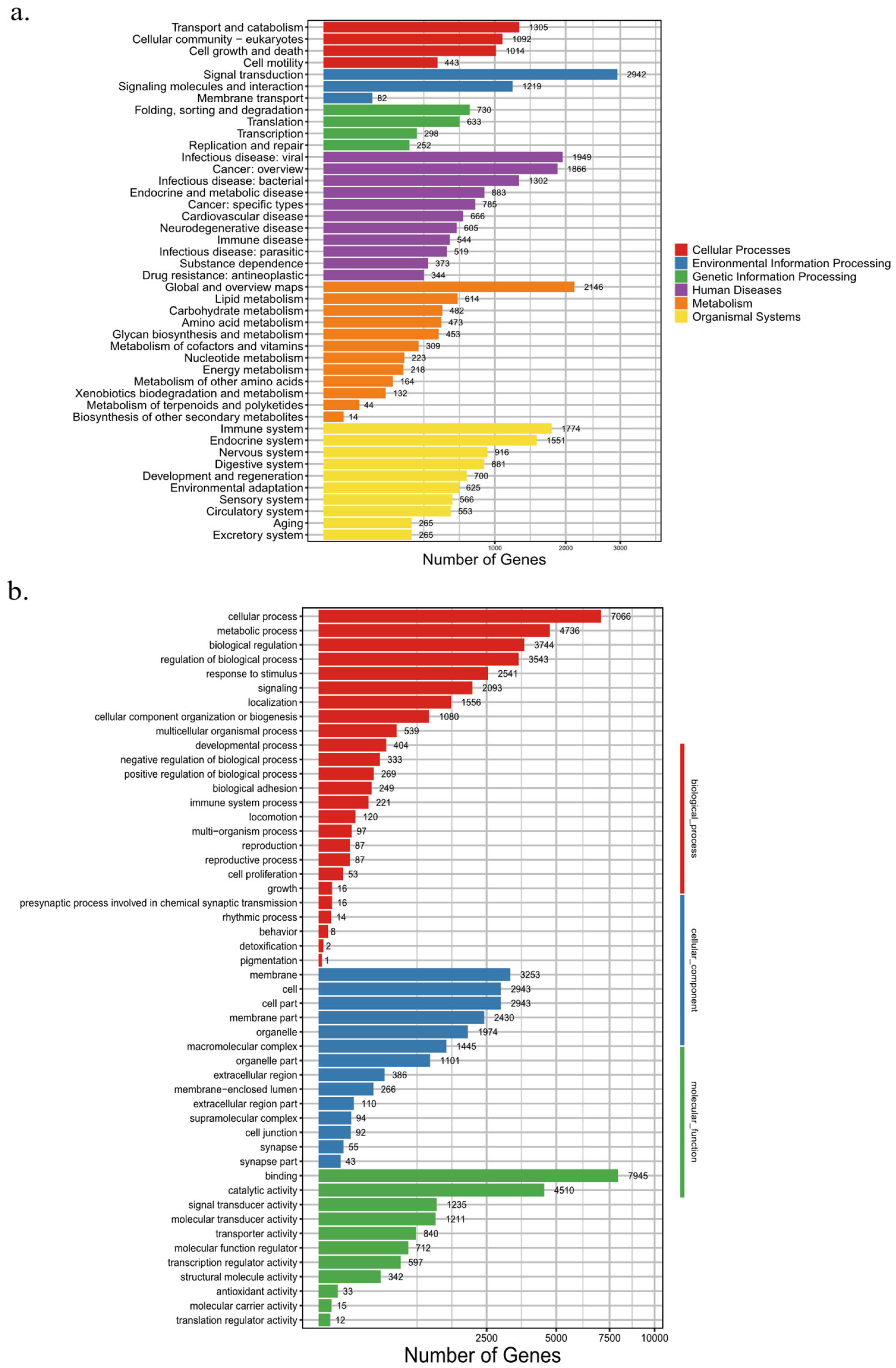

Comparing our results with various public datasets, such as InterPro [

37], KEGG [

38], SwissProt [

39], TrEMBL [

39], and GO terms, we identified 21,695 expanded gene families, including 99.17% functionally annotated genes (

Table 7).

Further analyses using KEGG enrichment revealed that Environmental Information Processing, Organismal Systems, and Metabolism pathways were the most abundant, with Signal Transduction pathways being the most prominent. Among the Organismal Systems pathways, 1,774 Immune System genes and 1,551 Endocrine System genes were the most abundant (

Figure 4a). In addition, based on the results of our GO analysis, we found that 7,900 genes are related to binding, while 7,740 genes are related to cellular processes (

Figure 4b).

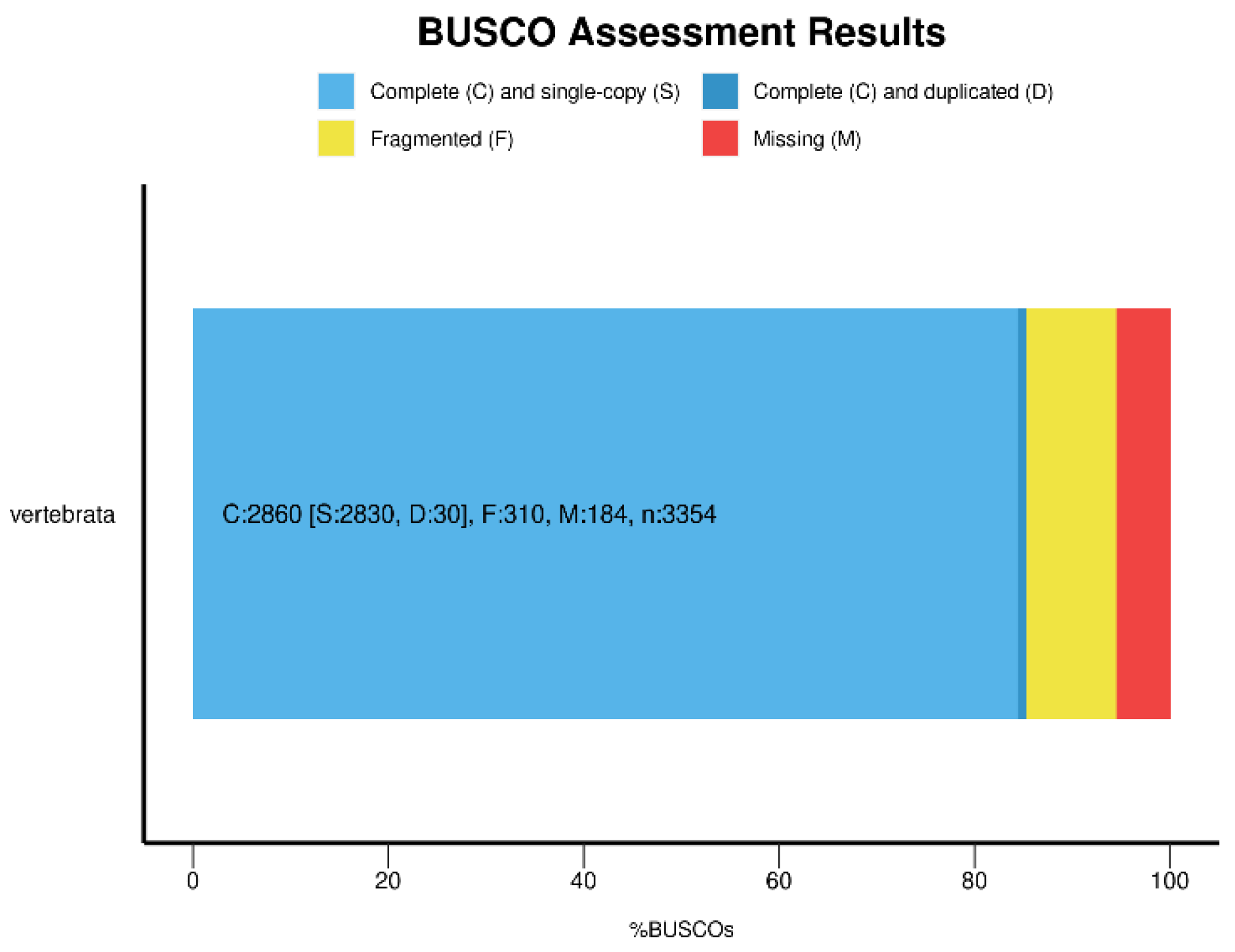

Data Validation and Quality Control

We employed BUSCO v5.2.2 to assess the quality and completeness of our genome assembly [

40]. The results of our BUSCO analysis revealed that our assembly achieved 85.3% completeness when evaluated against the vertebrata_odb10 database (

Figure 5), indicating that our assembly is of relatively high quality and completeness.

To evaluate the integrity of our assembly, we generated a phylogenetic tree using the protein sequences of seven distinct amphibian and reptile species (Anolis carolinensis, Chelonia mydas, Deinagkistrodon acutus, Ophiophagus hannah, Python bivittatus, Xenopus tropicalis, and Alligator mississippiensis), along with the protein sequences of Gallus gallus, Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, and Danio rerio obtained from NCBI. The resultant phylogenetic tree aligns with prior research findings, affirming that our data can reliably discern relationships among species (

Figure 6).

Reuse Potential

We unveiled the inaugural genome assembly of the white-lipped arboreal pit viper. This information furnishes novel tools for delving into the serpent's biological and evolutionary aspects, along with the genetic underpinnings of its venom.

Author Contributions

H Liu and H Lu designed and initiated the project. Y C and Y F performed the DNA extraction and the library construction. X N and J C performed the data analysis. X N, J C and Y L wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The information substantiating the conclusions of this research has been stored in the CNGB Sequence Archive (CNSA) [

41] within the China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) [

42] , under the designated accession number CNP0004151. The unprocessed data can be accessed on NCBI using the Bioproject number PRJNA955401 (see also the machine readable nanopublication: RAV3oIcruk). Supplementary data is also accessible through GigaDB [

43].

Editor’s note

This article is a component of a collection of Data Release manuscripts introducing the genetic codes of diverse serpent varieties [

44].

Ethics approval

The research conducted in this study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of BGI (BGI-IRB E22017).

Acknowledgments

Our initiative received backing from the China National GeneBank (CNGB). Additionally, Hainan University and BGI-Shenzhen provided support for this endeavor. The sample collection was carried out by Anhui Normal University. Funding for this project was granted by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Genome Read and Write (grant no. 2017B030301011).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbrevitions

fAbbreviations used include fq for fastq, GO for gene ontology, KEGG for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, LINE for long interspersed nuclear element, LTR for long terminal repeat, SINE for short interspersed nuclear element, stLFR for single-tube long fragment read, TEs for transposable elements, and WGS for whole genome sequencing.

References

- Gray JE. Synopsis of the species of Rattle snakes, or Family of Crotalidae. Zoological Miscellany 2: 47–51. http://repositorio.fciencias.unam.mx:8080/xmlui/handle/11154/158063.

- Leviton A, Wogan G, Koo M, Zug G, Lucas R, Vindum J. The Dangerously Venomous Snakes of Myanmar. Illustrated Key and Checklist. 542003; https://repository.si.edu/handle/10088/4542.

- Zhu F, Liu Q, Che J, Zhang L, Chen X, Yan F, et al.. Molecular phylogeography of white-lipped tree viper (Trimeresurus; Viperidae). Zoologica Scripta. 2016;. [CrossRef]

- Cockram CS, Chan JC, Chow KY. Bites by the white-lipped pit viper (Trimeresurus albolabris) and other species in Hong Kong. A survey of 4 years’ experience at the Prince of Wales Hospital. J Trop Med Hyg. 93:79–86 1990;

- Liew JL, Tan NH, Tan CH. Proteomics and preclinical antivenom neutralization of the mangrove pit viper (Trimeresurus purpureomaculatus, Malaysia) and white-lipped pit viper (Trimeresurus albolabris, Thailand) venoms. Acta Tropica. 2020;. [CrossRef]

- Jangprasert P, Rojnuckarin P. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of albolamin: A type P-IIa snake venom metalloproteinase from green pit viper (Cryptelytrops albolabris). Toxicon. 2014;. [CrossRef]

- Pinyachat A, Rojnuckarin P, Muanpasitporn C, Singhamatr P, Nuchprayoon S. Albocollagenase, a novel recombinant P-III snake venom metalloproteinase from green pit viper (Cryptelytrops albolabris), digests collagen and inhibits platelet aggregation. Toxicon. 2011;. [CrossRef]

- Tan CH. Snake Venomics: Fundamentals, Recent Updates, and a Look to the Next Decade. Toxins. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2022;. [CrossRef]

- Olaoba OT, Karina Dos Santos P, Selistre-de-Araujo HS, Ferreira de Souza DH. Snake Venom Metalloproteinases (SVMPs): A structure-function update. Toxicon X. 2020;. [CrossRef]

- Zhu F, Chen L, Guo P, Xu Y, Liu Q. Sexual Dimorphism and Geographic Variation of the White-lipped Pit Viper (Trimeresurus albolabris) in China. Current Herpetology. 2022;. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra A, Thorpe RS. A Phylogeny of the Trimeresurus Group of Pit Vipers: New Evidence from a Mitochondrial Gene Tree. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2000;. [CrossRef]

- Casewell NR, Wüster W, Vonk FJ, Harrison RA, Fry BG. Complex cocktails: the evolutionary novelty of venoms. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2013;. [CrossRef]

- Calvete JJ. Venomics: integrative venom proteomics and beyond*. Biochemical Journal. 2017;. [CrossRef]

- Rao W, Kalogeropoulos K, Allentoft ME, Gopalakrishnan S, Zhao W, Workman CT, et al.. The rise of genomics in snake venom research: recent advances and future perspectives. GigaScience. 2022;. [CrossRef]

- Song T, Zhang C, Zhang L, Huang X, Hu C, Xue C, et al.. Complete mitochondrial genome of Trimeresurus albolabris (Squamata: Viperidae: Crotalinae). Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;. [CrossRef]

- Wang O, Chin R, Cheng X, Wu MKY, Mao Q, Tang J, et al.. Efficient and unique cobarcoding of second-generation sequencing reads from long DNA molecules enabling cost-effective and accurate sequencing, haplotyping, and de novo assembly. Genome Res. 2019;. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Cui L, Deng Z, Ma Y, Yang D, Gong Y, et al.. The annotation pipeline for the genome of a snake. protocols.io. 2023;. [CrossRef]

- Weisenfeld NI, Kumar V, Shah P, Church DM, Jaffe DB. Direct determination of diploid genome sequences. Genome Res. 2017;. [CrossRef]

- Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, et al.. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience. 2012;. [CrossRef]

- Pryszcz LP, Gabaldón T. Redundans: an assembly pipeline for highly heterozygous genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;. [CrossRef]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;. [CrossRef]

- Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatModeler Open-1.0. 2008–2015. Seattle, USA: Institute for Systems Biology. http://www.repeatmasker.org, Last Accessed May. 1:20182015;

- Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics, 2009; 25: 4.10.1–4.10.14. [CrossRef]

- Tempel S. Using and understanding RepeatMasker. Mobile genetic elements: protocols and genomic applications. Methods Mol. Biol., 2012; 859: 29–51. [CrossRef]

- Stanke M, Steinkamp R, Waack S, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;. [CrossRef]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;. [CrossRef]

- Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, et al.. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;. [CrossRef]

- Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, et al.. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;. [CrossRef]

- Mount DW. Using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2007;. [CrossRef]

- Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;. [CrossRef]

- Campbell MS, Holt C, Moore B, Yandell M. Genome Annotation and Curation Using MAKER and MAKER-P. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 2014;. [CrossRef]

- Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, Simão FA, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;. [CrossRef]

- Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biology. 2015;. [CrossRef]

- Yin W; Wang Z; Li Q; Lian J; Zhou Y; Lu B; Jin L; Qiu P; Zhang P; Zhu W; Wen B; Huang Y; Lin Z; Qiu B; Su X; Zhang G; Yan G; Zhou Q (2016): Supporting data for "Evolutionary trajectories of snake genes and genomes revealed by comparative analyses of five-pacer viper" GigaScience Database. [CrossRef]

- Margres MJ, Rautsaw RM, Strickland JL, Mason AJ, Schramer TD, Hofmann EP, et al.. The Tiger Rattlesnake genome reveals a complex genotype underlying a simple venom phenotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2021;. [CrossRef]

- Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al.. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M. The KEGG Database. ‘In Silico’ Simulation of Biological Processes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; [CrossRef]

- Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;. [CrossRef]

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Chen F, Gao F, Li L, Liu K, You L, et al. CNSA: a data repository for archiving omics data. Database. 2020;. [CrossRef]

- Chen FZ, You LJ, Yang F, Wang LN, Guo XQ, Gao F, et al.. CNGBdb: China National GeneBank DataBase. Yi Chuan (Hereditas,). 2020;. [CrossRef]

- Niu X; Lv Y; Chen J; Feng Y; Cui Y; Lu H; Liu H (2024): Supporting data for "The genome assembly and annotation of the White-Lipped Tree viper Trimeresurus albolabris" GigaScience Database. [CrossRef]

- Snake Genomes. GigaByte. 2023; [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).