1. Introduction

The date palm

Phoenix dactylifera is one of the earliest perennial plants to undergo domestication. The oldest botanical record of the date palm is 19,000 years ago, found in archaeological excavations on the Sea of Galilee [

1]. Its presence is documented in the East Mediterranean dating back to biblical times [

2]. Thriving in arid and semiarid regions across the globe, this resilient tree plays a pivotal role as a foundational fruit tree in predominantly Eastern and Southern Mediterranean countries, as well as in the Near East, where it stands as a significant cash crop [

3]. Beyond its economic importance, the date palm is widely incorporated as a common ornamental tree throughout the Mediterranean basin. The presence of date palms in the area, both in their wild form and under cultivation continuous for thousands of years in the East Mediterranean [

4], has contributed to the rich diversity of herbivorous arthropods of this tree.

The modern cultivation of date palm plantations in Israel is believed to have commenced around 1924, marked by a significant influx of offshoots (suckers) from Egypt [

5]. The 1950s saw the emergence of notable challenges in plant protection, particularly with the outbreak of two species of armored scale. Since then, the roster of arthropod pests has expanded to encompass 31 species, with approximately half of them being deemed economically significant [

6]. Presently, the five primary arthropod pests in date palm plantations in Israel, ranked by their relative economic impact, include the red palm weevil (RPW),

Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier, the lesser date moth,

Batrachedra amydraula Meyrick, the old world date mite (

Oligonychus afrasiaticus McGregor), sap beetles (Nitidulidae, mainly

Carpophilus hemipterus L), and a rhinoceros beetle, the bunch stalk borer,

Oryctes elegans Prell (Svetlana Dobrinin, unpublished data). The former three species are considered among the top ten arthropod pest of date palm worldwide [

7]. To the best of our knowledge, RPW is the sole invasive species within the pest complex affecting the date palm in Israel. In contrast to other major arthropod pests, this species does not target the fruits or their bunch stalk.

The contemporary cultivation of date palm trees in urban areas across Israel is well rooted in the Jewish and Moslem ethnicities. In the Jewish sector, the planting has been primarily motivated by the aspiration to incorporate a tree from 'The Seven Species' (Shiv'at HaMinim in Hebrew), a selection of seven agriculturally significant plants identified in the Hebrew Bible as special products of the ancient Land of Israel. Traditionally, date palms were planted in proximity to synagogues. Noteworthy for their rapid establishment as mature trees post-replanting, they seamlessly integrate into urban spaces, serving as an effective buffer between traffic lanes, and the low maintenance cost of these trees. Until the establishment of RPW, there was no imperative need to address any plant protection issues related to these trees in urban environments.

The tribe Rhynchophorini in the subfamily Dryophthorinae in the weevil family (Curculionidae) brings together species that inhabit various palm species, including the RPW. The natural distribution range of the RPW spread over Southeast Asia and Melanesia. However, the large commercial distribution of palms, mainly coconut and date palms, mainly from the mid-1970s, led to the establishment of the weevil in many countries, directly or following infiltration from neighboring countries [

8]. The large economic losses and damage to biodiversity caused by the invasion of the weevil in large areas of the world have earned it the status of a serious major pest that requires the development of effective management strategies to prevent or to stop the damage [

9].

The establishment of the weevil in the eastern Mediterranean basin began already at the end of the 1980s, and in Israel, it was discovered in 1999 [

10]. The severe damage in Israel and other countries in the region (and in general) was especially manifested in the damage to the date palm and the Canary Island date palm, which are among the palms that are very sensitive to the attack of the weevil [

11,

12]. The frequency occurrence of the latter palm species as ornamental tree in Israel was steeply reduced due to the loss of most of the conspecific trees to the weevil. The weevil remains the sole significant pest of ornamental date palms in Israel.

The main difficulty in dealing with tree borers is the discovery of the adults during the short activity of egg laying. In addition, the eggs are often hidden in the outer layers of the bark, and the penetration of the larvae into the trunk is usually characterized by no continuously noticeable symptoms. Therefore, in many cases, when dealing with the weevil, the natural tendency was to adopt one of the strategies that would prevent the palms from being inhabited. Hence, application of insecticides that are contact poisons against adults has been usually the considered tactic [

13], together with traps' activation for the adult mass capture [

14]. The weevil's aggregation pheromone was identified as early as 1993 [

15]. However, soon it became clear that these tools are not promising. The use of synthetic pesticides to prevent palm infestation is not quite effective, being expensive when applied to all palms in the setting. The conclusion soon suggested that the discovery of the palms inhabited by the weevil is an essential element for the management [

16,

17].

In principle, identifying a palm infested by the weevil is not simple. A visual examination of external damage symptoms through a survey from the ground, or the use of remote thermal sensing have not been adopted as an effective interface tool because, in practical terms, such detection is only feasible in very advanced stages of colonization. Often discovery the typical chemical signature of a palm infested by the weevil was studied by employing dogs, but this approach has not proven itself on a commercial scale either. There is no doubt acoustic and seismic sensors bring to light the main scientific and technological efforts to detect the weevil's occupation of the palm [

9].

Attempts to develop acoustic sensors represent the majority of reported efforts in this area. An acoustic sensor detects and measures the movement speed of the air particles in response to sound waves, and allows audio signals to be received and analyzed. That is, apparently, with a relatively simple act of inserting a microphone, one can listen to the gnawing sounds made by the weevil larvae inside the monitored stem medium. Despite the extensive reporting in the professional literature, acoustic sensors have not developed into a central tool in weevil monitoring. A seismic sensor is designed to measure vibrations or mechanical vibrations within a solid material, such as soil, rock or wood, and in this case, it is designed to pick up the mechanical vibrations in the stem because of the activity of weevil larvae. The IoTree Agrint seismic sensor (Agrint Rockville, Maryland, USA) is the only product widely used commercially [

18]. The widespread use of this sensor in plantations and urban areas began in 2020 (Agrint, personal communication), and therefore, several years of experience have been accumulated in several palm settings of the effect of the sensor employing on the changes in the frequency of palm trees affected by RPW.

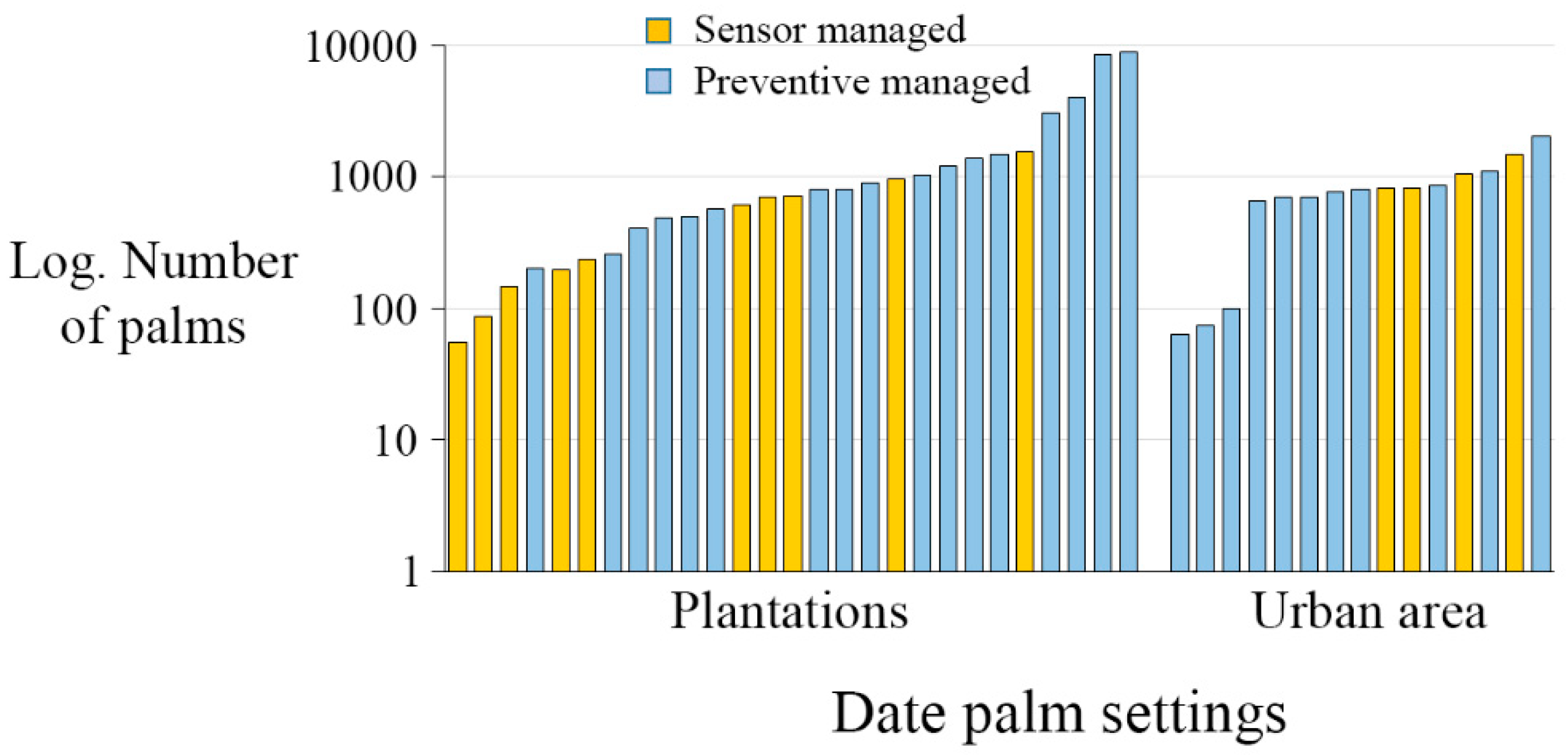

The weevil may colonize date palm trees almost at any age. In Israel there are 910,000 fruit-bearing date palms, with the most common varieties are Medjoul 82.3% and Deri 7.4% [

19]. About a quarter of plantations are at the susceptible age (4-14 years after planting) for the red palm weevil attack, and among those 25% are sensors installed. Currently, the colonization of very young trees (from the state of rooted high offshoots to 3-year-old trees) or mature trees (> 15-year-old trees) is uncommon. In addition, 36,000 date palms growing in public areas in Israel (as park or street trees, of different varieties, with Hayani as the dominant one). About 27% of these palms are sensors installed (Agrint Ltd, unpublished data). The installation of the sensors in large settings makes it possible to compare the two management strategies against the RPW, sensor-based management vs preventive management based on prophylactic insecticide treatments.

The weevil control practice in Israel is still mainly synthetic pesticide-based. Ground application of Imidacloprid (a systemic neonicotinoid) or cover spray to the lower section of the stem by Imidacloprid + Lambda Cyhalothrin (a pyrethroid) serves as a preventive measure in both public areas and plantations in places where sensors are not in use. Curative measures include the application of both above mentioned insecticides or stem injection of Imidacloprid or Thiamethoxam (another systemic neonicotinoid). In organic plantations and in conventional plantations during fruit set, the preventive measure includes the application of formulation of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana to young trees) up to the maximum age of 12-14 years) and spraying of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae as a curative measure [

20,

21,

22,

23].

In this report, we compare the RPW infestation picture as revealed by the two management strategies, preventive vs sensor-based management in two kinds of environments, date palm plantations and ornamental trees in the urban area. We also examine three aspects deriving from sensor activation in date palm settings as follows. (1) The relationship between the curative treatments with respect to the damage index in the plantations. (2) The relationships between curative treatments and the damage index information. (3) The probability of occurring an attack event on a certain palm tree as related to its RPW infestation history. (4) The effect of sensor-based management on the decline of RPW infestation incidence over time.

4. Discussion

The invasion of the Red Palm Weevil has had far-reaching consequences on both agricultural and urban date palm cultivation in Israel and other regions. This event is a significant turning point in terms of plant protection for date palms and has led to a substantial impact on the economy, affecting both the fruit and ornamental aspects of the tree. The establishment of the weevil population has resulted in notable changes in the economic costs associated with managing date plantations in Israel. For Medjoul date palm plantations, the cost per adult tree has increased by 2%, rising from

$350 to

$362 [

27]. In urban settings, the management expenses for date palm trees have surged by a staggering 40%, soaring from

$138 to

$192 per adult tree [

28]. These shifts underscore the considerable economic challenges faced by both agricultural and urban sectors in the wake of the RPW invasion. The elevated expenses associated with controlling the date palm weevil in urban areas of Israel, coupled with the already high costs of irrigation and the limited shade offered by the palms in the context of global warming, have led to a hesitancy among most municipalities to persist in planting date palms within their territories. The feasibility of this approach is impractical for Israeli date growers, especially considering the relatively modest increase in management expenses attributed to the RPW, even though it constitutes significant economic and environmental costs. Regardless, land managers in both agricultural and urban settings are apprehensive about the cumulative impact of extensive synthetic pesticide use. Consequently, in both environments, there is a shared pursuit among land managers to reduce reliance on chemical pesticides and foster a more environmentally friendly and sustainable landscape.

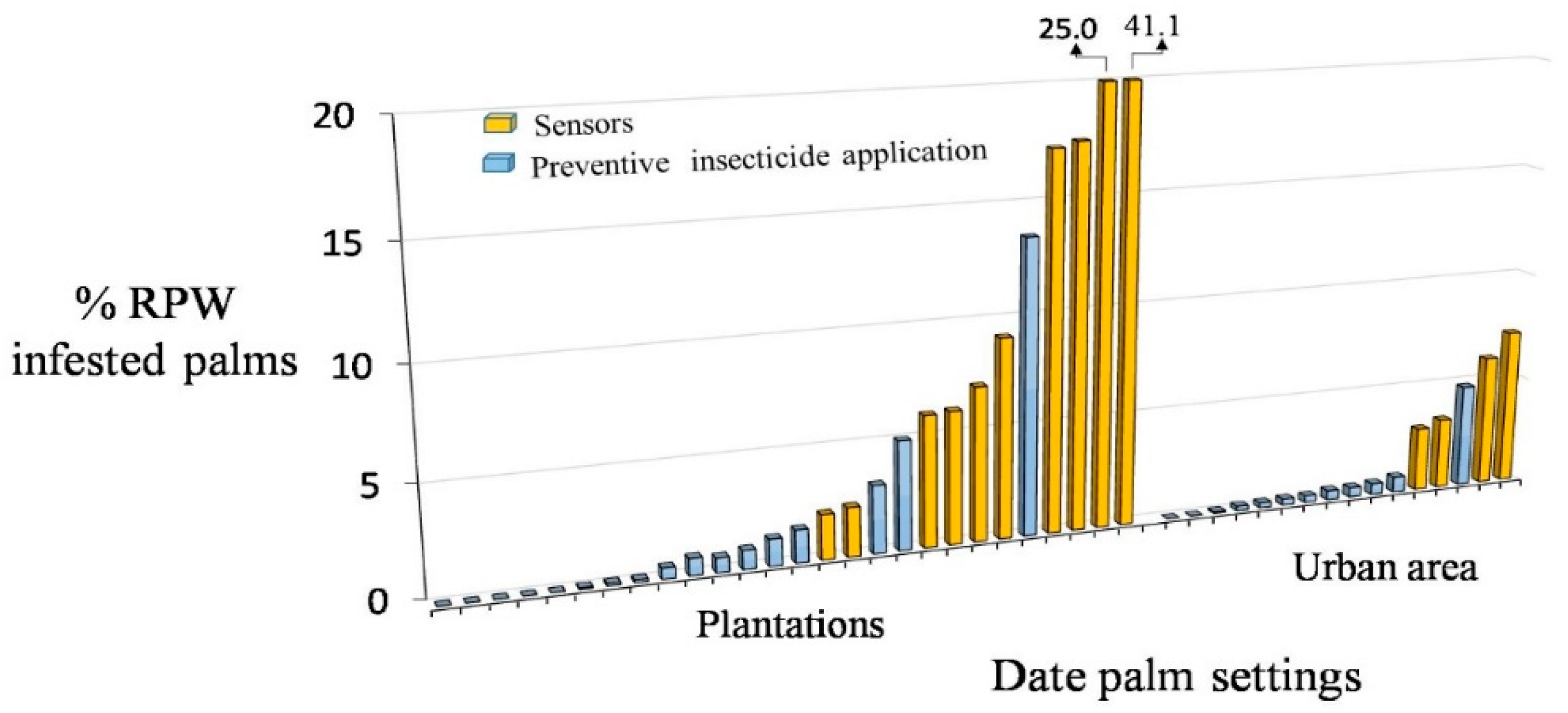

The implementation of seismic sensors in palm settings in both agricultural and urban areas aims primarily to curtail the widespread use of synthetic insecticides and instead focus extermination efforts on trees inhabited by the weevil. However, current findings indicate that the rate of RPW colonization in settings managed by sensors appears to be considerably higher than in comparable settings employing preventive measures. However, these significant differences may not totally reflect the infestation situation. The seismic sensor sensibility allows pinpointing on an infestation that is usually unrevealed by other detection or monitoring procedures, particularly in the range of the sensor detection, the palm crown, and the lower section of the stem in ornamental and plantation trees, respectively. On the other hand, the monitoring of the palm infestation in settings under preventive measures, as we learned during the collection of information for the preparation of the article, it almost never takes place, and is only manifested when noticeable signs of damage appear, and in many cases only the collapse of the palm spurs the monitoring of its surroundings.

Though, these notable differences may not fully capture the extent of the infestation situation. The heightened sensitivity of seismic sensors allows for precise identification of infestations that often go unnoticed by other detection or monitoring methods. This is especially true within the sensor's detection range, focusing on the palm crown and the lower section of the stem in ornamental and plantation trees, respectively.

The frequent use of pesticides in date plantations, coupled with the weevil's increasing tendency to attack the crown, particularly due to the activity of the bunch stalk borer, O. elegans [7, S. Dobrinin unpublished data], is anticipated to adversely impact the tree's environment, fruit quality, and harm the entomofauna of the tree, particularly the natural enemies guilds of severe pests in this habitat [

6]. The extensive use of pesticides in urban environments is also a significant concern [

29]. While accumulated experience suggests that some date trees infested by the weevil can overcome the infestation without human intervention, this appears to be the exception rather than the rule. In the cases examined in this study, the number of palms subjected to curative treatments was relatively small, often not exceeding 10% of the total trees. Moreover, the methods employed to eliminate the RPW infestation, such as stem injection of systemic insecticides and, notably, the application of entomopathogenic nematodes, are considerably safer compared to the commonly used preventative spray applications.

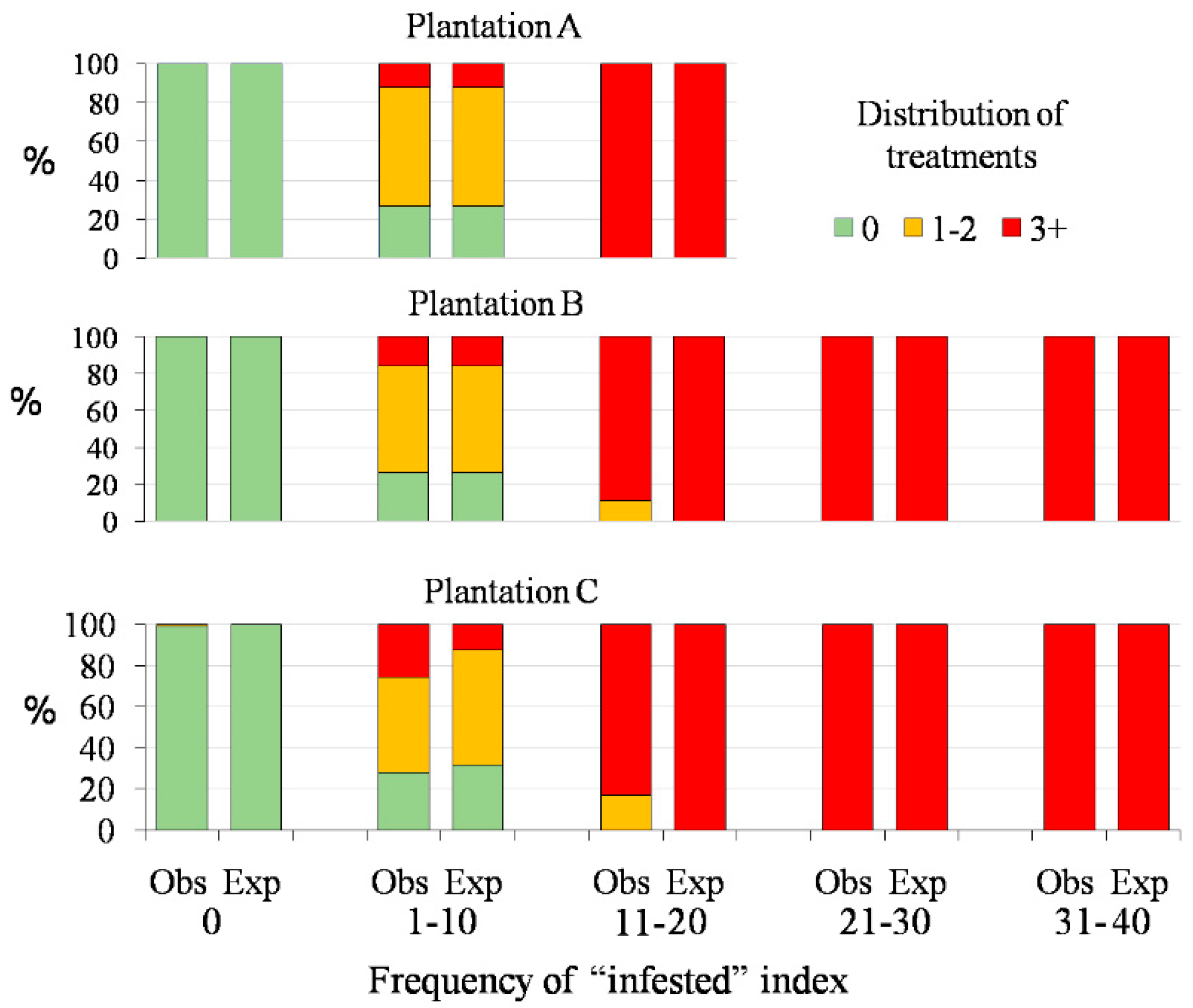

The seismic sensor information classifies instances as 'suspected' based on conditions that precede the formal 'infested' designation. However, this categorization is dynamic and may later transition, often marking the initiation of an unsuccessful infestation by weevil larvae that eventually returns to a "healthy" status. It's noteworthy that the 'suspected' category may, in rarer cases, be prompted by activities of other biological agents [

18]. Consequently, 'suspected' does not consistently serve as an early indicator of weevil colonization or a signal to take immediate action. This observation may elucidate why an examination of curative treatment distributions in relation to the 'suspected' damage index did not reveal a significant association between the two datasets in our analysis. Specifically, when comparing distributions for one or two treatments versus no treatment and three or more treatments versus one or two treatments, no notable correlations were found. In each of the three plantations studied, the curative treatments eventually led to a "healthy" damage index classification. This suggests a positive dependence in probabilities corresponding to the aforementioned treatment comparisons. This dependency indicates a close relationship between 'infested' damage index information provided by the sensors and the applied curative treatments targeted at the relevant palm trees in each plantation. This underscores the high reliability of the IoTree sensors.

Wood borers, prominent among various beetle families, are naturally drawn to and infest weakened, damaged, dying, or dead trees and wood products. The interaction between indigenous tree species and foreign wood borers, or vice versa, can pose a significant threat, leading to successful attacks on seemingly healthy trees. The RPW is no exception, and its invasive colonization success varies among potential palm host species [

30] and even date palm varieties [

25,

31]. There is little doubt that the invasion of RPW in the Mediterranean had a profound impact, primarily devastating the Canary Island date palm

Phoenix canariensis and, to a lesser extent, the date palm [

9,

11,

32,

33,

34]. The RPW shows a strong preference for the Canary Island date palm, making it highly suitable for its development [

35]. Accumulated experience indicates that without proper protection, the Canary Island date palm is significantly affected by the weevil, whereas damage to date palms in similar environments, typically urban and park settings, is not widespread even without preventive measures.

Despite limited knowledge about the genetic factors contributing to tolerance or resistance in date palm varieties against RPW, a recent study by Abdel-Bakya et al. [

36] suggests that the varying responses of palm cultivars to palm weevil infestation may be linked to factors such as the chemical composition of nutrient mineral elements in the soil or genetic diversity among cultivated varieties. However, physiological weaknesses and physical wounds likely serve as the primary stimuli for beetle attacks on potential hosts. Volatile compounds released from fresh wounds on palms attract and stimulate RPW females to lay their eggs [

25].

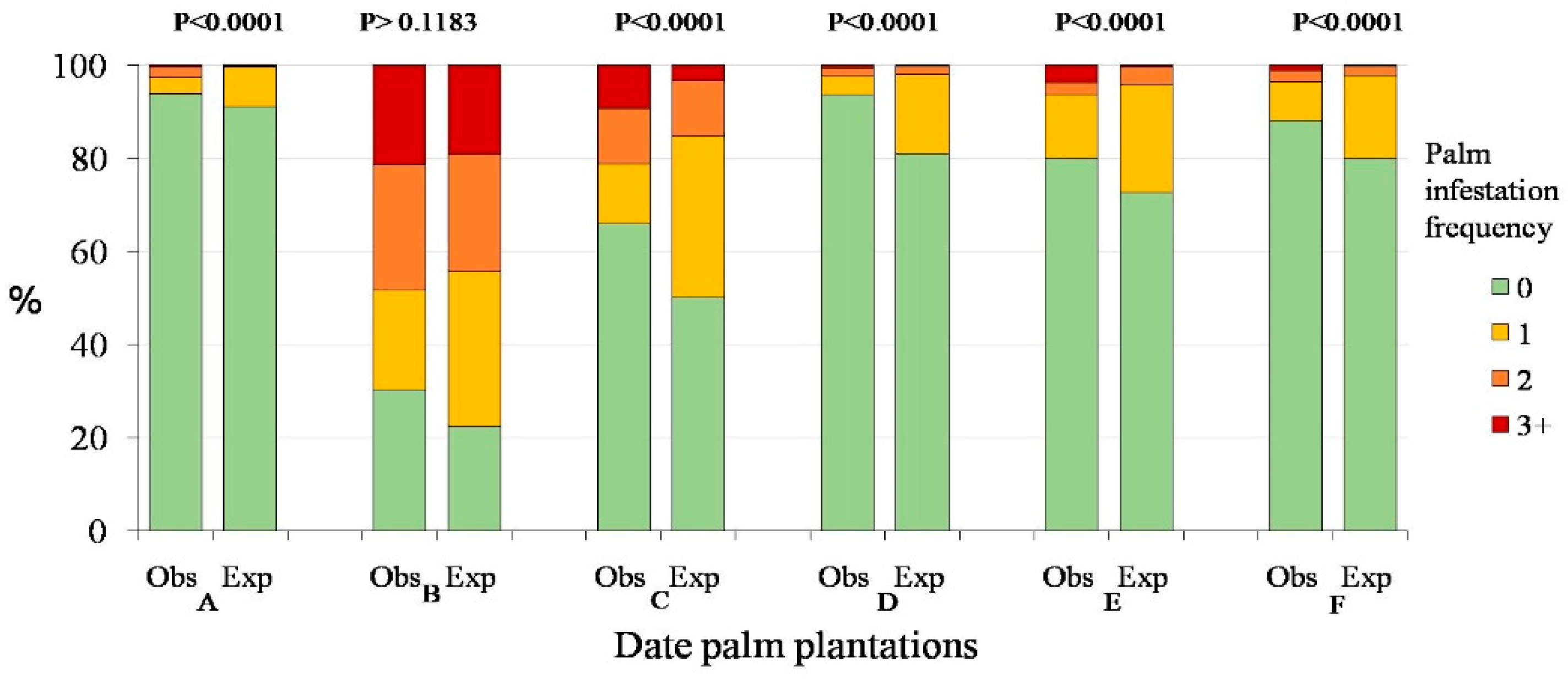

In our current investigation, we observed a notable increase in the likelihood of the RPW attack event on a specific date palm tree within a given plantation. This heightened probability was particularly evident in trees previously infested by RPW, subsequently underwent curative treatment, and obtained a 'healthy' damage index. This consistent pattern was observed across all six plantations studied, indicating that the palm's recovery did not eliminate all injury symptoms. These trees probably still emitted cues that made them more attractive targets for RPW females. Collectively, events categorized as 'suspected' occurred more frequently than expected based on Poisson distribution, suggesting that instances where the 'suspected' damage index was determined often involved some form of injury that could later draw the attention of RPW. However, upon closer examination of the 'suspected' category for each plantation individually, it was revealed that in four out of the six studied plantations, this category did not deviate significantly from what would be anticipated by Poisson distribution. It is essential to note the potential influence of the association between 'suspected' and 'infested' categories on these findings. In light of these results, it is imperative to emphasize the connection between previously RPW-affected trees and the need for heightened vigilance among growers. Specifically, growers should focus on monitoring new potential RPW infestations and implement more stringent prevention and protection measures, recognizing the lingering vulnerability of trees that have undergone curative treatment after successful colonization by the weevil. Our previous study has revealed that importance of early detection and fast reaction by applying entomopathogenic nematodes as curative treatment to infested trees [

18].

Despite the flight ability of the weevil and the great distances that the adults may travel in a relatively short time [

37], the spread pace of the weevil in the area of the date plantations is not fast. For example, in Saudi Arabia, the weevil appeared in 1987, and its spread between the regions of the country continued until 2015 [

25]. In Israel, the weevil was recorded for the first time in 1999 and there are still date palm areas in the Arava Valley where it has not reached. Another example is in the village Idan in the Arava Valley (where plantations B and C are located, see

Table 1). It took four years until the weevil population moved from the plantations on the eastern side of the village to those on the western side (a distance of 2.5 km) (S. Dobrinin unpublished). The slight movement of the weevil between the growing areas probably indicates that the weevil tends to stick to the place where its population was established. This picture may explain at least in part the reduction of the weevil population in date palm settings under a continuous management of monitoring using the sensors as demonstrated in the present study (

Figure 5). It seems that most of the adult weevils in the plantation originate within the site, and the penetration of adult weevils from outside the plantation area is marginal. Then, under meticulous management, when all the trees, marked by the sensors as infested by the weevil, are subjected to curative treatment, the RPW population in the plantation, or in the relevant urban environment, will gradually decrease.

Upon the request of the Investments Directorate of the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture, an economic evaluation for date palm plantations was undertaken [

27]. The report indicates that the annual cost of preventive red palm weevil (RPW) management per date tree, employing pesticides as per Ministry recommendations, amounts to

$22.5. In contrast, utilizing sensor-based management reduces the cost to

$6.7 per tree. This calculation is based on a 5.2-hectare plantation of the Medjoul variety, featuring a tree density of 130 trees per hectare and a sensor equipment lifespan of 10 years. Concurrently, Agrint Ltd conducted an economic assessment for date palms in urban areas [

38]. Here, the annual cost of preventive RPW management per date tree using pesticides is

$40.4, while the calculated cost of sensor-based management is

$18.9 per tree. This evaluation considers a treated area with 1000 trees and a sensor equipment lifespan of 6 years. Importantly, both assessments exclude the costs associated with curative treatments under either strategy when necessary.

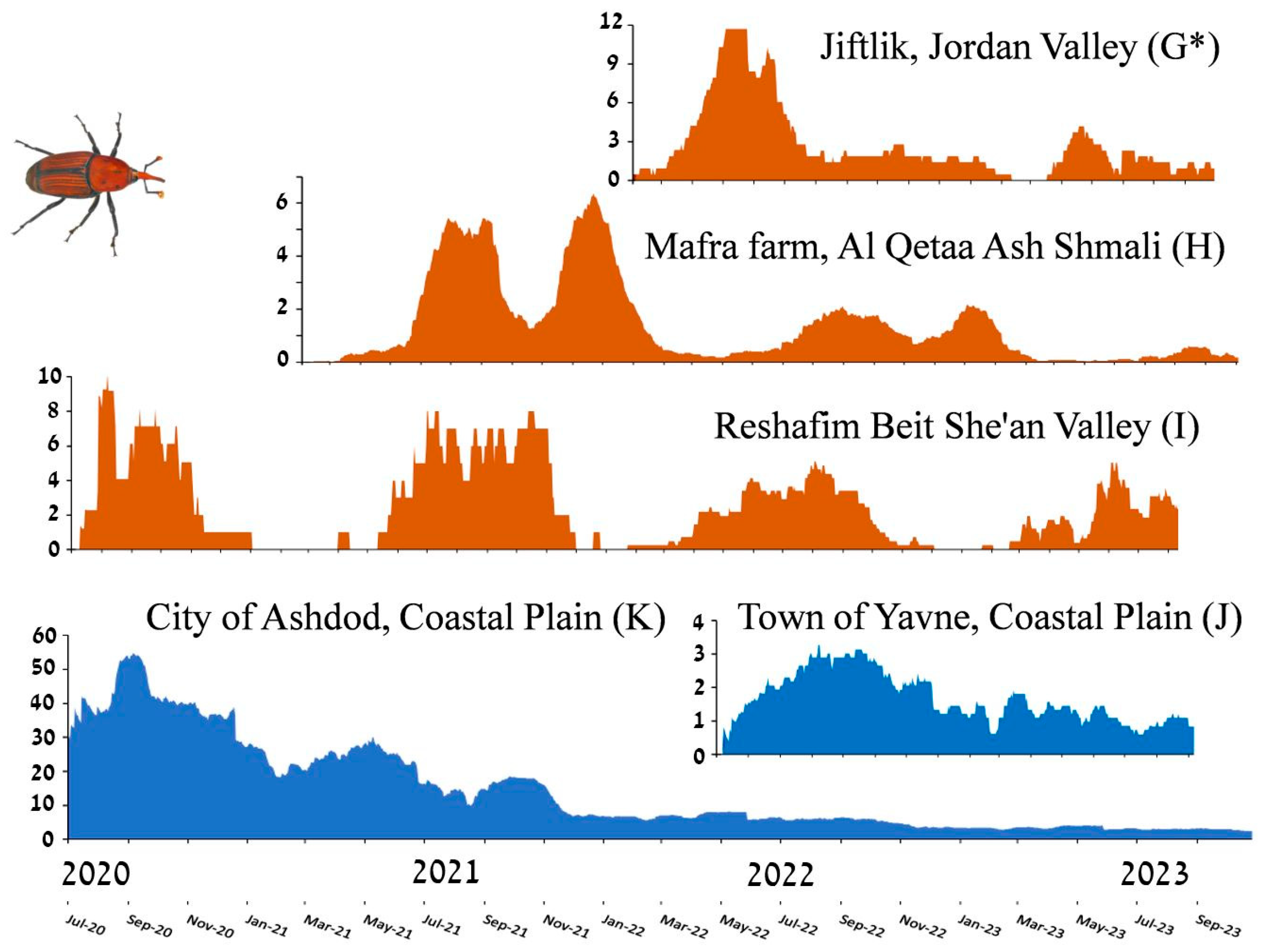

The distinctive fluctuation pattern observed in palm infestations across the three studied plantations and two cities under examination appears to be closely tied to the diverse temperature regimes prevalent in these regions. Notably, the observed waves of activity in the plantations, characterized by apparently no infestation during the summer months, likely stem from the exceptionally high temperatures experienced during this period in these areas (with daily maximum temperatures in August reaching between 40-46°C). The RPW population, as established by Peng et al. [

39], exhibits susceptibility to extreme temperatures, with an optimal growth temperature around 27 °C; a critical threshold of 44–45 °C at which pupae are effectively eliminated was already suggested by Salama et al. [

40]. In contrast, the summer temperature regime in the Israeli coastal plain—where the date palm settings of the two cities under examination are situated—is relatively mild, with daily maximum temperatures in August ranging between 30-33°C. Probably because of this moderate climate, RPW infestations persist throughout the entire year in this region.