1. Introduction

Historically, pyrolysis primarily served as a method for producing carbonaceous materials, including wood and coal. For thousands of years, charcoal was utilized by humans as a heat source until it was eventually replaced by coal due to its higher energy content. In the late 19th century, wood distillation emerged as a lucrative practice for generating useful substances such as solvents, creosote oil, bitumen, various chemicals, and non-condensable gases, which found extensive application in boiler heating systems. However, with the advent and expansion of the petrochemical industry in the 1930s, leading to the availability of more cost-effective products, the wood distillation sector experienced a decline [

1].

Due to the reduction of environmental pollution and the added value of polymer waste, many options have been created to prevent landfilling, such as various separation, processing, and recycling methods to produce energy and valuable products from polymer waste. With the progression of science and the introduction of new technologies, the chemical recycling of polymer waste is expanding. Using different pyrolysis methods and waste classification, valuable products, light, and heavy hydrocarbons, gas, carbon, Etc., are produced. These reactions take place in batch and semi-continuous operation reactors [

2].The calculations, design, and material of the body of the reactor or heat chamber are essential because to pyrolyze the polymeric material, heat must penetrate the body, and then the degradation of the polymers begins. Various processes of pyrolysis of polymer waste are being developed in different countries of the world. However, microwave as an efficient, controllable, and low-depreciation technology with many other advantages for pyrolysis of materials can change the future of recycling systems. During World War II, we developed telecommunication radars that produced and used a wide electromagnetic range between 300 MHz and 3 GHz in high quality, which we called the microwave [

3,

4]. Then inventions were made in this field, such as the cavity magnetron, which is a powerful, inexpensive, and effective invention used by the microwave source for a wide range of purposes. The heat generated by the microwave in the material is generated by the charged species and the resistance of the material's bipolar particles to the field created by the waves. In terms of material quality and the effect of the microwave on the electric field created and the interactions in general, materials can be classified in three ways: (A) Materials that the microwave has no effect on and that pass through and act as insulation, (B) Materials that do not absorb microwaves and that do reflect waves, such as conductors' materials, and, Dielectric materials that absorb microwaves and the radiation of these dielectric heating waves have also been introduced themselves. Many mechanisms contribute to the dielectric reactions in different materials, including dipoles, ionic conductivity, electronic polarization of materials, atomic, Maxwell Wagner, or surface. Things like Maxwell Wagner and their polarization convert the waves into thermal energy to transmit electromagnetic energy at microwave rates [

1]. Pyrolysis is the operation in which materials are indirectly heated in a vacuum environment without oxygen or air, and in an endothermic process, the material itself is thermally decomposed. The process itself has a thermal efficiency of about 70%, and if the fuel required for pyrolysis is provided from the products produced, the efficiency increases to more than 90% [

5]. The energy required for the pyrolysis process indirectly heats itself by transferring heat and heating its own outer wall of the chamber or reactor. The temperature required for pyrolysis of polymer wastes is between 400 and 800 ° C [

6]. Temperature changes are one of the critical factors that directly affect the distribution or phase of the product. The effect of temperature on products is that by increasing the pyrolysis temperature, gas production increases, and by decreasing the pyrolysis temperature, liquid production increases. In this process, the product is also affected by speed and heat transfer. Processes require the appropriate temperature and velocity for their pyrolytic decomposition. Cooling is used to increase the condensing of gas molecules in order to create more liquid goods. Depending on the type of waste of polymeric materials for pyrolysis, one can increase the weight of the liquid produced up to 80% [

7]. The supply of pyrolysis vapor throughout the system, until it reaches the condensers and products, must be done in an environment with an inert atmosphere, without oxygen, or with injection of nitrogen gas. Purging the system with nitrogen also helps to keep secondary reactions in the hot zone to a minimum [

1]. Furthermore, Mechanical and chemical recycling are the main methods for polymer waste. Pyrolysis is a chemical recycling method that uses heat without oxygen to break down polymers. Microwave pyrolysis utilizes microwave energy for efficient, volumetric heating itself. Itself can achieve high temperatures and heating rates. Carbon materials themselves absorb microwaves well due to polarization effects. Multiple factors influence the yield and quality of pyrolysis products, including temperature, heating rate, and reactor design. Fluidized bed reactors are commonly used. Vortex reactors are a novel approach to improve heat/mass transfer themselves. Valuable fuels and chemicals can be obtained from waste polymer pyrolysis, including light hydrocarbons, aromatics, and syngas, by oneself. However, we face challenges such as dealing with mixed waste streams ourselves. Polymer wastes such as plastics and tires represent a significant environmental issue due to their low biodegradability and ineffective recycling systems. In South Africa, less than 20% of polymer waste is recycled, with the majority ending up illegally dumped or in landfills [

1]. This leads to problems such as ocean plastic pollution, of which South Africa ranks among the top countries globally [

1]. There is a critical need for improved recycling technologies and infrastructure to divert these disposed polymers from landfills and recover value from them. Pyrolysis is a chemical recycling technique that can transform polymer wastes into useful fuels, chemicals and gases through thermal depolymerization in the absence of oxygen [

6]. It offers benefits over other disposal methods that just burn or bury the waste. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis utilizes microwave energy to rapidly heat the waste polymers from within, enabling faster heating rates, better process control, and higher product quality compared to conventional external heating [

8].

The aims of this study are difine as the following procedures: 1-To evaluate the feasibility of microwave-assisted pyrolysis for energy production from polymeric materials. 2- To investigate the influence of microwave frequency, temperature, and residence time on the pyrolysis process. 3-To design and optimize a continuous microwave vortex reactor system called Pwave+ to recycle polymer waste streams into valuable hydrocarbon products in an efficient, scalable and sustainable manner.

2. Bachground

The proposed method for recycling polymer waste aims to make use of cutting-edge innovations in the industry by incorporating cutting-edge technologies like microwaves and analytical systems [

9]. In the first stage of this proposal, mechanical recycling systems, which are typically used for waste separation, play a significant role. The research covers a wide range of processing and materials science topics, all of which pose difficulties for effective mechanical recycling systems. Challenges include ensuring efficient separation of polymers from other waste materials and halting the introduction of pollutants. The quality of the final product is directly related to how well recycled materials are optimized, taking into account a variety of materials, price fluctuations, and the constraints of the proposed scenarios [

10]. This encourages and piques people's curiosity about chemical recycling, which is not as common as it should be.

The research investigates various methods for processing polymer waste into uniform granules, which can then be used to manufacture chemical products like fuels or different polymers with the desired performance and similarity to the required raw materials [

11]. In addition, there are situations in which separation is technically and economically unfeasible, calling for alternative approaches to recycling heterogeneous and contaminated polymer waste, which have greater potential for efficient material recovery [

12]. Pyrolysis of polymer waste, and especially waste tires, is a well-known and frequently-discussed topic [

13]. Understanding how variables like temperature, shredded polymer waste size, heating rate, and feed residence time affect pyrolytic product yields is a major area of research. Gas, liquid (oil), and solid (char, and for tire waste, steel and ash added) are the three main products generated from polymer waste recycling, with the composition of each portion determined by the pyrolysis conditions and the type of reactor used [

12].

Because of the valuable compounds that can be extracted from oil, the investigation centers on the ideal ratio of pyrolysis products produced from microwaves in order to construct an ideal system using Pwave +, which may be the most advanced microwave technology in the world [

14]. As the research progresses, an upgraded system or human intervention will be required to collect and process the carbon in the smoke to activate the process. The cost of converting gas into electricity is significantly lower than the cost of oil. However, learning more about pyrolysis technologies and reactors makes it much simpler to locate the most effective method of recycling polymer waste [

11]. The primary objective of this work is to compile and make available a wealth of information regarding the science, technology, construction, and practical application of pyrolysis of polymers and biofuels [

15].

The first batch of biomass pyrolysis material has formed because biomass is the first raw material used in the decomposition of pyrolysis. Fixed-bed reactors, some of which also use agitators, are mobile bed reactors that are pneumatically displaced, or it has a reactor rotating, centrifugal, chain, or screw reactors that move mechanically [

16]. These reactors are used for fast, medium, and conventional pyrolysis, respectively. Waste polymers include tires, particularly truck tires, which are rich in hydrocarbons and are therefore classified as a processed biomass. While conventional or agricultural biomass shares some mechanical and thermal properties with whole or crushed tires [

17], tires have their own unique set of characteristics. Based on the energy supply methods required for pyrolysis, there are many criteria for pyrolysis classification sources, which are:

Supply the required heat of pyrolysis by extracting fuels from pyrolyzed products,

The heat required for the pyrolysis process enters the interior of the reactor through a gas or inert substance,

To increase the thermal efficiency of the exhaust gases through external walls or internal radiators to prepare re-separation processes,

Other factors affecting the performance of the reactor include:

Batch or periodic with fixed bed and continuous with fluidised bed,

Suitable pyrolysis medium under atmospheric pressure, vacuum, or inert gas overpressure, without oxygen and with or without catalyst [

18],

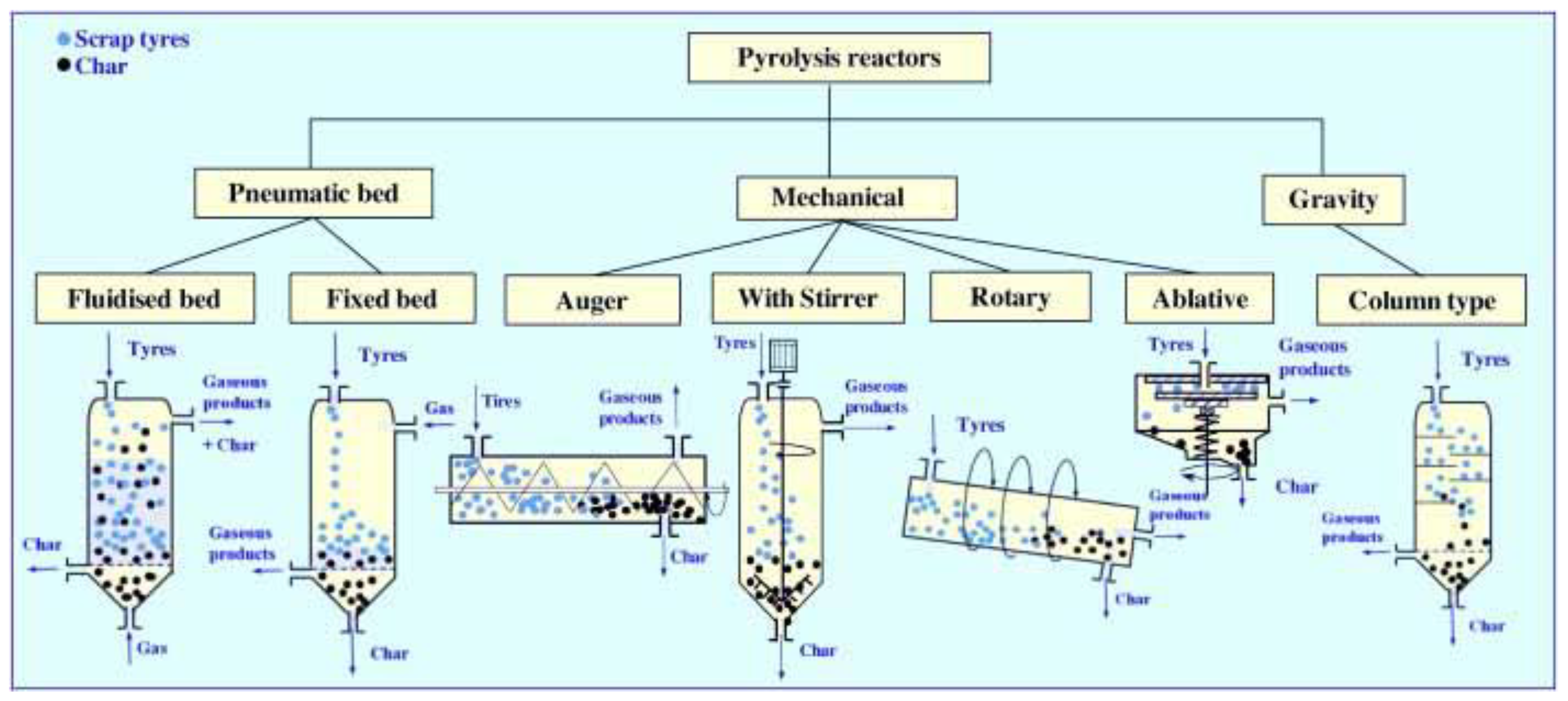

In the present work, pyrolysis classifies as shown in Figure 3-1, depending on how the raw material (powder, granules, pieces, polymer waste, or whole waste tires) is forced to move inside them, i.e., pneumatically, mechanically, and gravitationally.

The types of pyrolysis illustrated diagrammatically in

Figure 1 have a crucial influence on oil and gas yields and the composition and quality of the third primary product of pyrolysis carbon black or activated carbon. Pyrolysis oil is a highly complex mixture, especially from tires containing aliphatic, aromatic, hetero-atomic, and polar fractions. The gases are a mixture of

, C1–C4 hydrocarbons,

, CO, and

. The use of catalysts during pyrolysis increases the proportion of hydrogen in gas and the number of aromatic compounds in the oil.

Whole or shredded tires have mechanical and thermal characteristics that are very different from conventional polymer waste. Hence, biomass reactors are not addressed in

Figure 1 unless they are comparable to those used for waste tires pyrolysis.

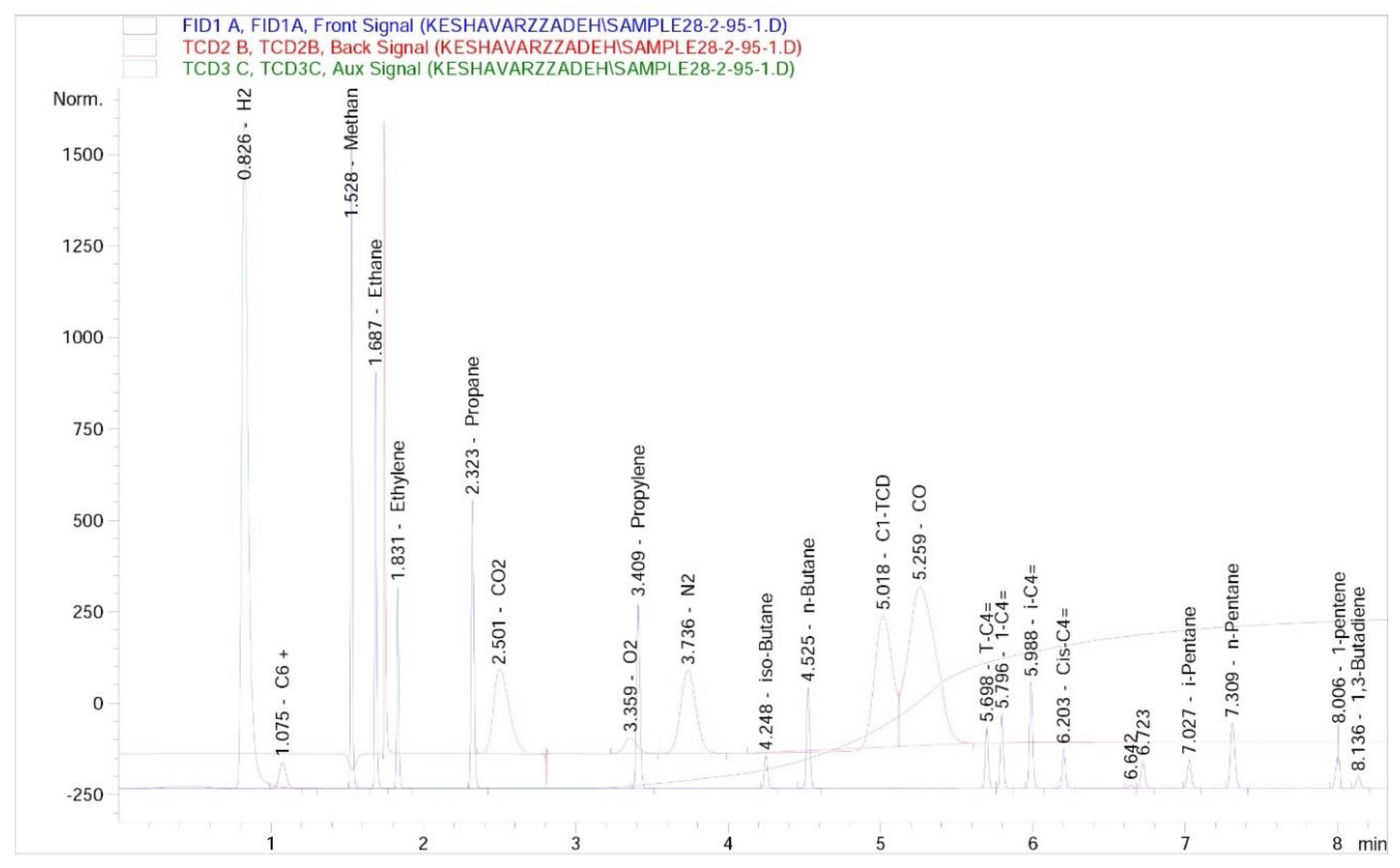

Based on the research, experiments, and experience gained in recycling tires and plastics, looking for a new solution to solve problems in pyrolysis systems and increase efficiency and optimize it. As can see in the analysis of exhaust gases from the pyrolysis reactor in

Figure 2, the exhaust gases from polymers, which in this form mainly test on the waste tire, are the source of hydrocarbons and recyclable gases.

Exhaust gases from pyrolysis of polymer waste (50% waste tire and 50% plastic) were obtained under vacuum conditions in a heat chamber and sent to the laboratory in a unique bag for testing.

By examining various methods, achieved the following points, Reductive Processes. It is important to note that most pyrolysis processes have a declining process and generally do not disrupt some oxidative processes but rather combustion. These procedures include those with hydrogen injections and those that exclude air and other oxygenators to create a reduced environment.

One way to desulfurize waste tires is to add hydrogen sulfide to the pyrolysis process, which reduces the amount of sulfur in the resulting products, such as oil and char. Since all reductive processes produce high-temperature gas, which may be as much as two times as hot as natural gas, burning a part of that gas is common to heat the reactor.

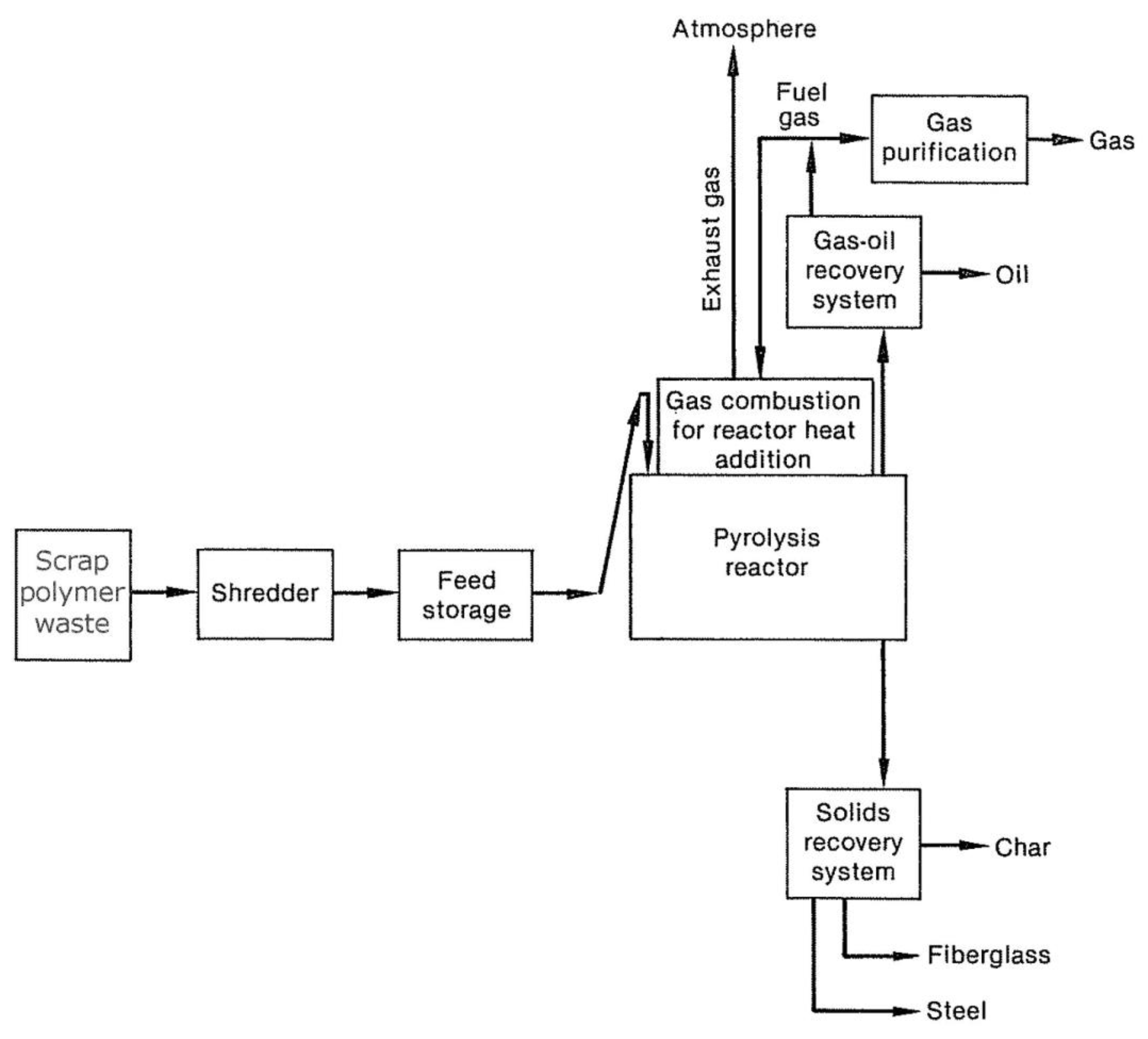

Figure 3, A general flow diagram showing the continuous polymer waste or the pyrolysis process of the reducing tires. The introduced steps can also use in batch systems.

As waste tires acquire from transportation or inventory, they shred into 2 to 6-inch pieces. It is possible to separate some steel using magnetism during the shredding process, although very few operators do so. In order to start the process and transfer the tires to the feed depot, several devices are used, which are usually funnel-shaped and feed the reactor by gravity through sealing systems and the use of multiple rotating valves. Some pyrolysis systems insert the tires completely into the reactor, which causes the material to decompose during the process [

20].

Figure 3.

The general flow of continuous pyrolysis process systems for waste polymers [

21].

Figure 3.

The general flow of continuous pyrolysis process systems for waste polymers [

21].

Finally, to optimize the process, using the maximum microwave pyrolysis recovery potentials and designing the Pwave+ system, various methods such as the results of this type of pyrolysis of polymer waste and then various reactors pyrolysis systems have been studied and tested.

In general, estimates indicate that there are hundreds of different types of pyrolysis reactors. Not able to cover them all in the scope of this proposal. Consequently, focus on the reactors that are the most widely used nowadays. The pyrolysis reactors group into several categories based on how long the gas stays within the reactor and how long it takes the polymer waste particle to reach the ultimate temperature or heating rate. Four major types of reactors are either in commercial operation or are about to be.

The four types of reactors mentioned here are fluidized bed, rotary kiln, moving grate-kiln, and retort. A wide range of operations may perform in these reactors, including oxidative or reductive reactions.

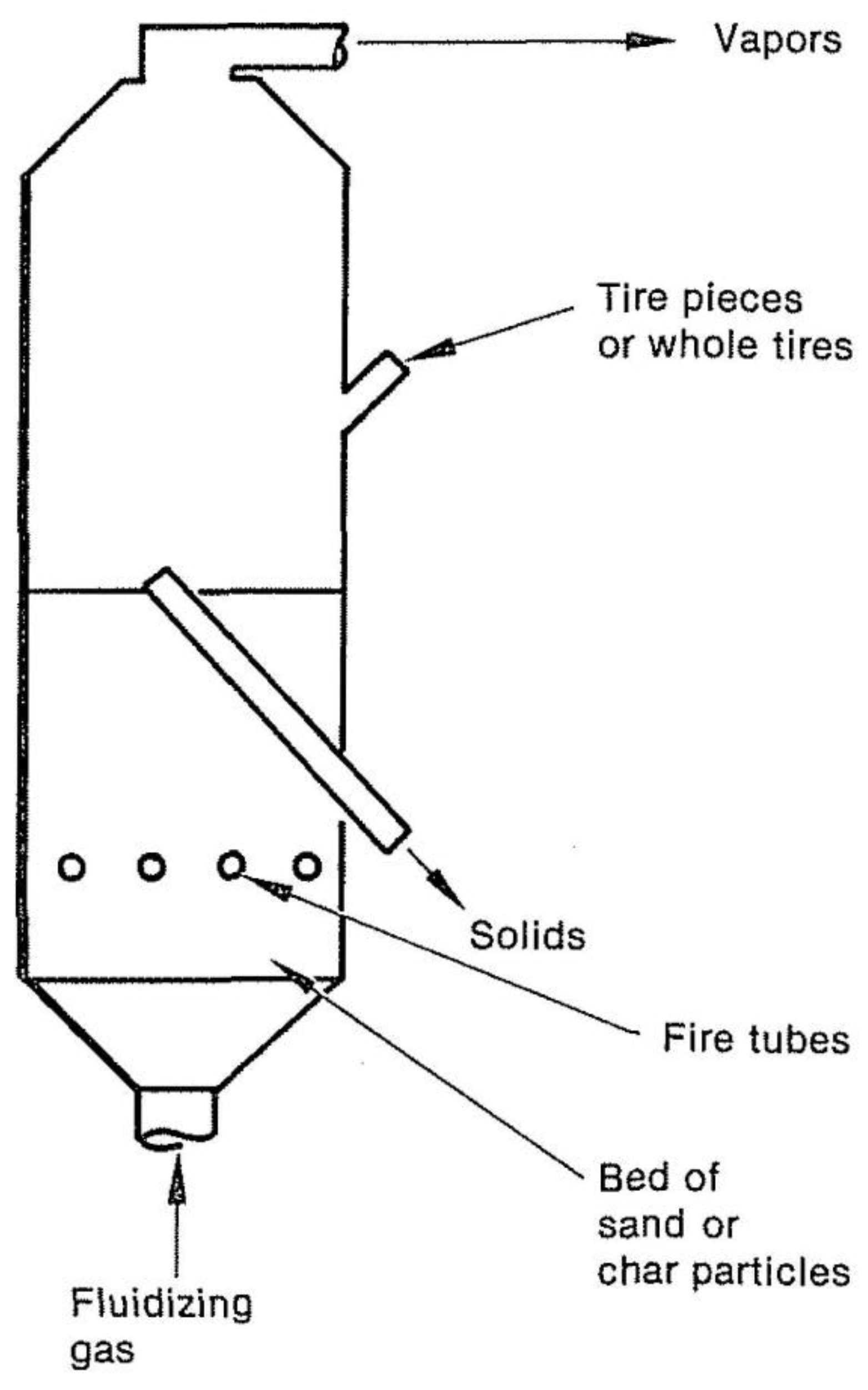

Figure 4 depicts a fluidized bed pyrolysis reactor. A fluidized bed has two main advantages: excellent solids mixing and the temperature of a consistent solid. The most significant drawbacks of a fluidized bed are removing entrained particles from the vapors and the need to provide fluidizing gas. Reductive systems do not need fire tubes, and the fluidizing gas for such a system is generally pyrolytic waste gas.

Air may use as a fluidizing medium in an oxidative system. Therefore, no external heat source is necessary. This bed is fed with waste plastics or tires, depending on the reactor's size; when it is in operation, Tire rubber is abraded due to fluidized particles abrasive action during the response, finally reducing the tire material microscopic fragments of char. The displacement of carbon particles is when the volume of the bed increases by adding feed overflow to the outlet pipe. It is common to remove small coal particles from the vapors using centrifugal separators and return the vapors to the bed.

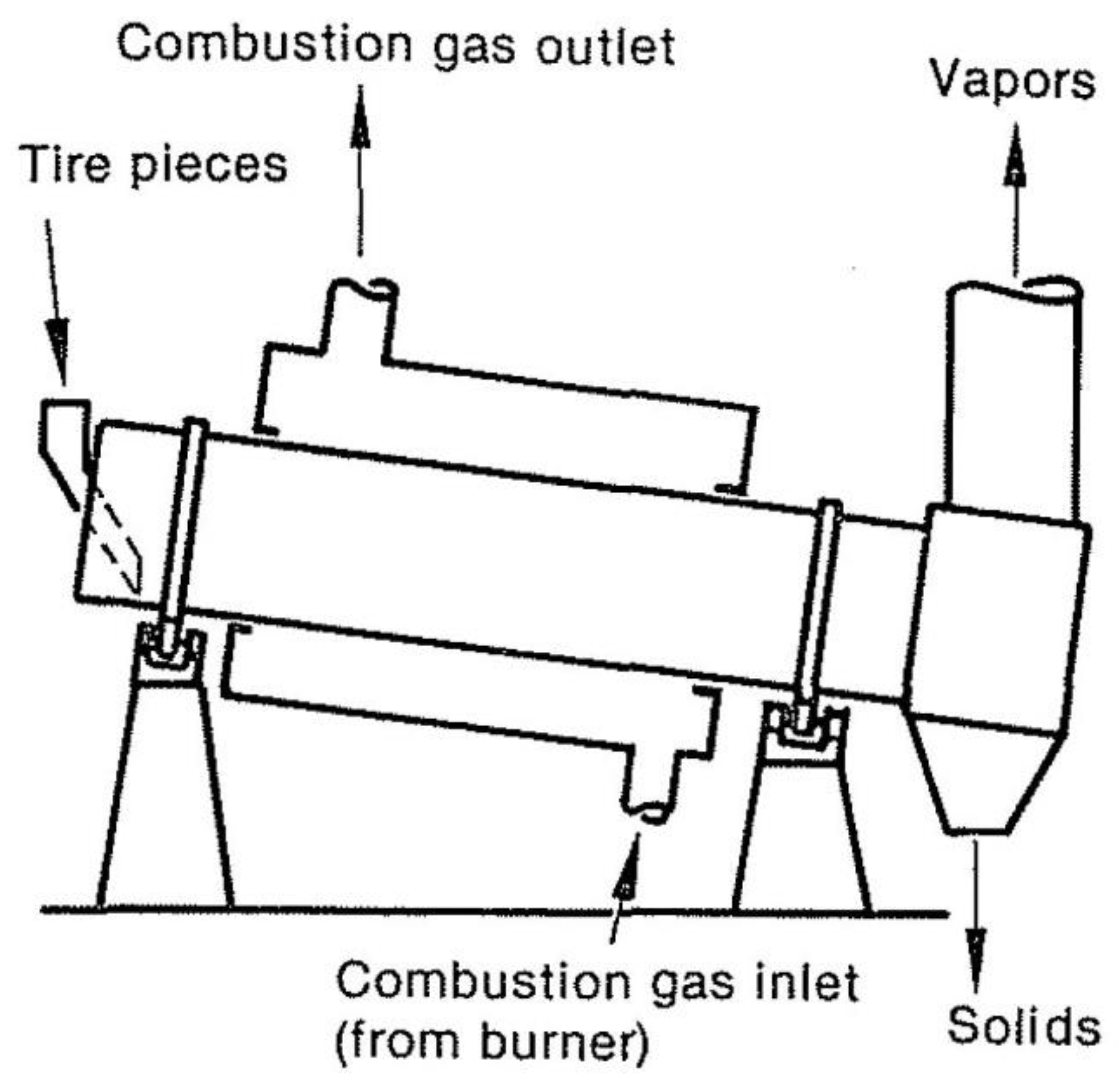

Figure 5 shows a rotary kiln pyrolysis reactor. Compared to fluidized bed reactors where the particles are well mixed, solids move through the rotary kiln in the fork flow, and for example, there is limited mixing during the rotary kiln. This solid-gas contact pattern uses continuous when using a rotary kiln with fabrics attached to the inner wall of the kiln to raise solids from below, then releases them, causing the gases inside the kiln to enter the reactor and provides the right temperature throughout the reactor.

Due to the details of the design and construction of these reactors in various companies, brief information about the furnace and internal systems of rotary pyrolysis reactors provides. The main problem with this model of reactors, which prevents air from escaping, is the need to seal a large area. In

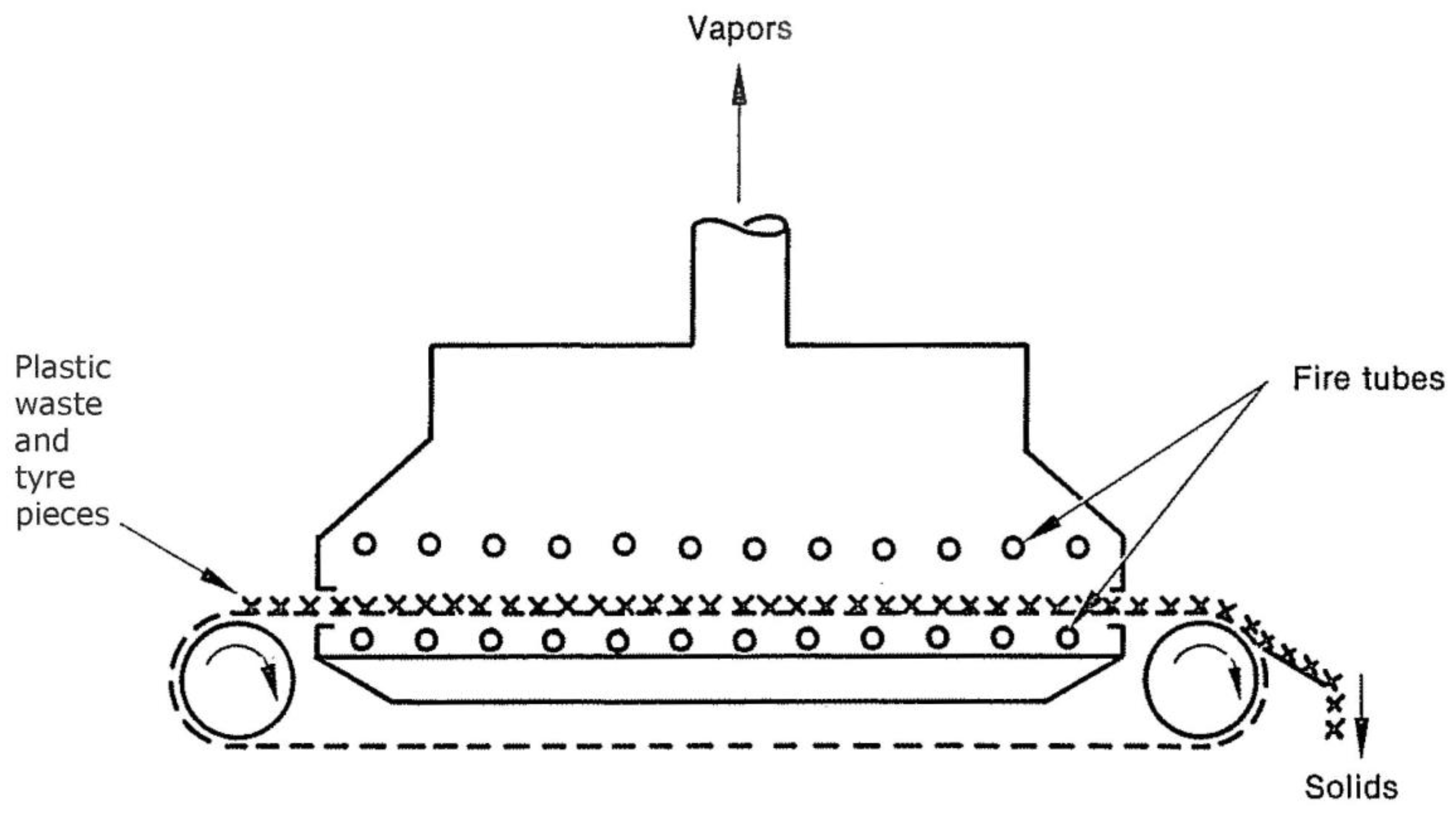

Figure 6 of a traveling grate pyrolysis reactor, see that its design is very similar to a rotary kiln. Nevertheless, the main difference between the two reactors is the flow of solids. Due to heat transmission from the fire tubes, the temperature homogeneity of solids at any axial point is less than with the rotating kiln. Compared to the rotating kiln, this reactor design is easier to seal, and it is also mechanically simpler.

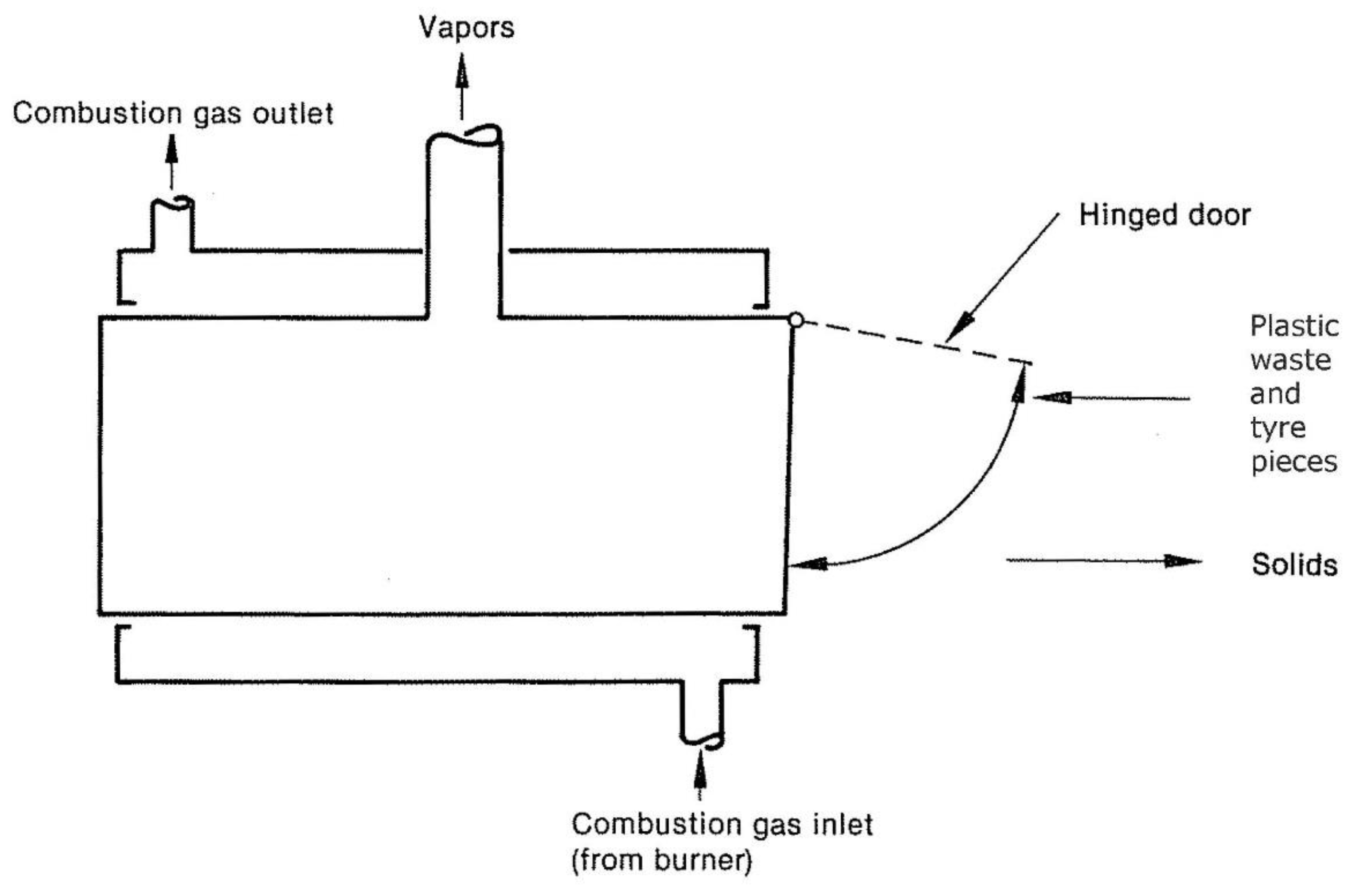

Figure 7 depicts a horizontal batch retort reactor. Plastics or tires may be placed into the reactor after it cool, and then the door can be closed, air can purge from the reactor, and heat can deliver to the external surface once the door has been closed. During the cycle, vapors constantly are eliminated. A fresh cycle begins when the reactor door is opened, solids are removed, and the reactor is reloaded to begin the process all over again [

21]. A continuous retort reactor can position vertically. One of the significant advantages of a retort reactor is that it is simple and easy to seal. Batch operations have the drawbacks of poor productivity and high labor expenses. In addition to molten salt, hot oil baths, plasma, and microwave reactors, other reactors consider, but microwave reactors have more potential to be explored because they could be more efficient in the new design. In the results of studies and experiments, there is a need for recycling systems to design a pyrolysis reactor with the help of a microwave or a more efficient reactor.

3. Methodology

3.1. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis

Developed by Tech-En Ltd in Hainault, UK, the device is a relatively new process that shows to perform heat treatment as an effective method in a warm bed to recover and recycle chemicals from problematic waste such as plastic waste, sewage sludge coffee hulls [

17].

For this process, the waste combines with a highly microwave-absorbent material such as carbon particles that absorbs microwave radiation and generates enough heat energy to reach the temperatures needed to create significant pyrolysis. The effect of microwave heat on waste in the absence of oxygen breaks down materials into smaller molecules. Renewable oils are composed of hydrocarbon volatiles that gives rise to a product called "pyrolysis oil," while depending on the reaction conditions, incompressible gaseous products are collected as "pyrolysis gases" with different compounds [

22].

3.2. Heat Transfer Mechanisms for Microwaves

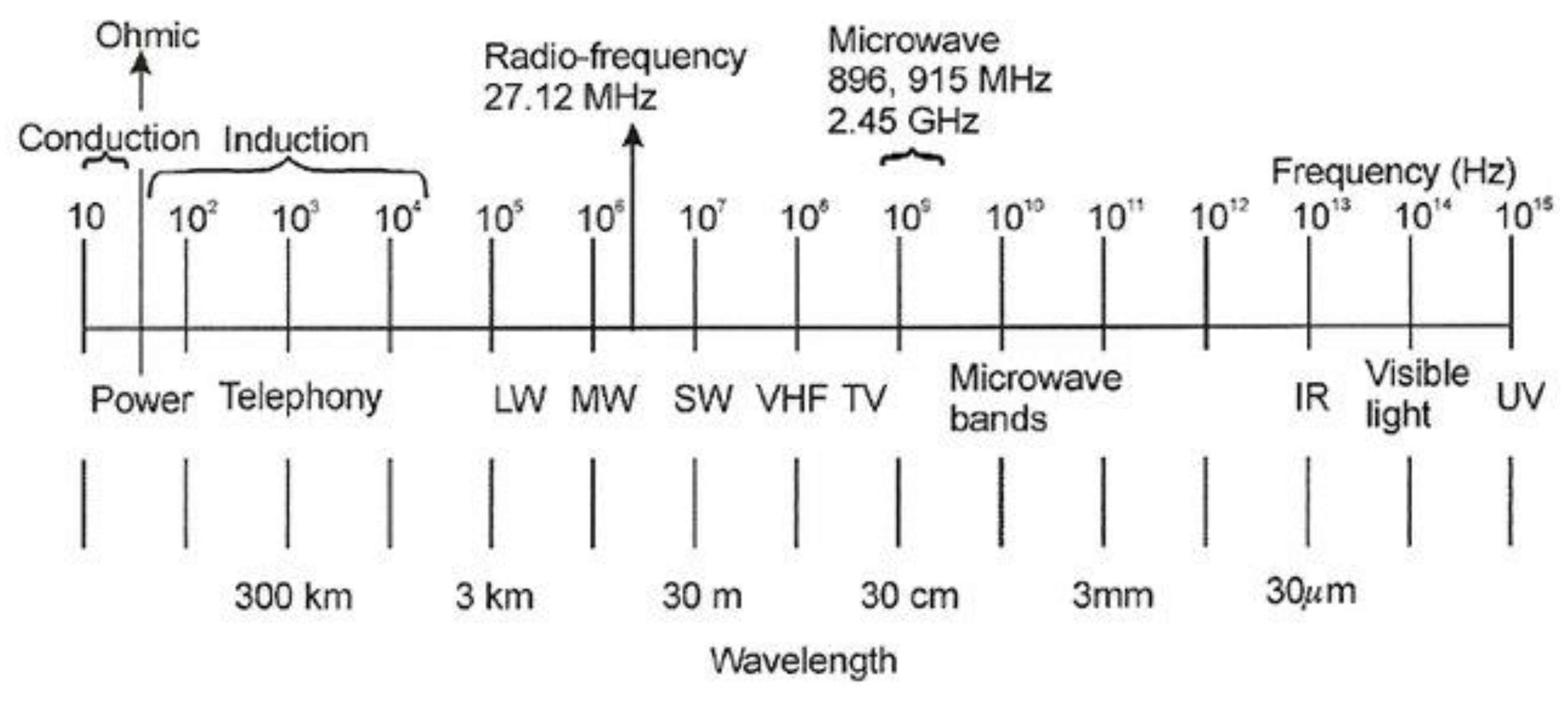

The heat generated by microwaves is classed as a volumetric heating technology that uses electric current. Also included in this group of heating techniques are conduction and induction heating, both of which operate at frequencies ranging from 0–6 Hz and 50 Hz–30 kHz; respectively, various heating techniques are done by sending a current through the workload to produce electric power I2R heating. While ohmic heating works at frequencies between induction and conduction heating, also included in this category, it uses the exact heating mechanism as the other techniques. There are other types of radiofrequency heating range from 1 to 100 MHz, but the most common is 27.12 MHz, which use to heat materials with a high resistance when put between electrodes [

22]. With samples from different electric volumetric heating technologies and frequency ranges, a typical electromagnetic spectrum with examples of applications shows here in

Figure 8.

According to the concepts and theories of microwave heating, materials are heated in a microwave field by three different methods. Microwave radiation causes charged particles in the substance to move, and these methods summed up as follows:

- a)

In this mechanism, when the material expos to microwave radiation and the bipolar orientation (polarization) of the material cause the material containing polar compounds to be heated mainly by these waves. When exposed to a microwave field, electronic polarization surrounding nuclei and nuclear polarization itself are dislocated from their equilibrium positions, leading to the formation of "induced dipoles." Due to the asymmetric charge distribution in the molecule, permanent dipoles occur in some materials, such as water. Under the influence of a changing or alternating electric field, induced or permanent dipoles tend to reorient. In the fluctuating field, the chemical bonds of induced or permanently polarized molecules realigned. It occurs billions of times every second, resulting in friction between the spinning molecules, which generates heat in the whole volume of the material [

24].

- b)

Maxwell Wagner or surface polarization results from the polarization of matter when the load is inhomogeneous at the points of contact or interface between the various components of the system. When substances at the interfaces have different conductivities and dielectric constants, polarization occurs. When the space charge builds up, it causes dielectric losses that contribute to heating effects, as well as field distortions.

- c)

Charged particles or carriers, such as electrons, ions, and the like, create electric currents when an electrically conductive substance expos to electromagnetic radiation. Under the influence of an externally generated electromagnetic field, electrons flow through the material, producing conducting pathways. Although most of these materials have a reasonably high electrical resistivity, the forced flow of electrons causes the material to heat up due to dissipating the power created by the forced flow of electrons [

22].

3.3. Design of the Pwave+ Technology

Pwave+ technology, to overcome the disadvantages of the pyrolysis and focus made to improve the efficiency because of modifications made on heat treatment and reactions practice. The required heat replaces by microwave pyrolysis, working based on a continuous process.

As shown in

Figure 9, powdered polymers with dimensions of less than 1 cm enter the (1A) section after separating the potential metals remaining from the pulverization operation. Due to the continuity of the system and preventing the entry of oxygen into the combustion chamber, inlet design is such that after the entry of materials, the presence of a vacuum pump (1B) causes oxygen to leave the environment. By maintaining tank pressure, the inlet polymers have a certain speed towards the combustion chamber.

The combustion chamber [

6] provides the required heat using a microwave concentrated in the chamber's core to generate the heat needed to pyrolysis the inlet material.

Due to the need to coordinate the mechanical and electrical parts of the device with each other, monitoring and control systems [

25] are used to coordinate and command different parts. The settings generally relate to the temperature required for pyrolysis operations (up to 600 ° C depending on the input polymers), control of inputs and outputs using automatic processing of changes in pressure, temperature, flow data, Etc. The combustion chamber decomposes materials in an environment with uniform heat. After cooling in several stages, the rest of the material is discharged as coal from under the chamber to prevent system pressure drop and gas leakage. The coal left over from the process is no longer affected by heat in addition to a sharp reduction in volumetric mass. However, in the other part, the combustion chamber gases enter the separator [

26]. The separator prevents the entry of heavy particles that enter the processed path due to the pressure of the gas produced in the combustion chamber.

The gases injected into the catalyst chamber [

27] increase the temperature and flow. A specific temperature is required to achieve the maximum effect of the catalyst on the material, so the two-layer catalyst chamber using a cooling coating reduces the temperature to about 200

.

Moreover, pass through the catalyst, which causes transparency and lightening of the liquid color. After passing through the catalyst of the upper part of the chamber catalyst, together with the liquid obtained from this part, other gases enter the separator [

28]. This part is composed of non-condensing gases of the previous stages, which are generally light hydrocarbons. Condensers [

29] reduce the remaining gas temperature to 100 ° C for storage, and the cooling system [

30] supplies water for the condensers between 20 and 30 ° C.

Despite the passage of gases through all these stages, there is still some non-condensing gas. Which have high flammability, and after passing through the condenser, they remain as gas Which store in a separate tank for use in a gas generator (9) to supply the necessary energy to the system. Exhaust gases from the generator and emergency pressure regulating valves in different parts of the system, connected to saline gas (10) to prevent possible clogging and increase pressure, which prevent the passage of polluted exhaust gases into the environment. The ideal pressure in the whole system is up to 0.5 bar and check by sensors connected to the control system.

The output of this system is light and heavy hydrocarbons, which can use as fuel or feed for refineries, as well as programmable, and depending on customer needs, and the system is modular so that parts can add to it.

3.4. Mechanism of the Pwave+ Technology Process

Depolymerization, or turning a polymer into a monomer or a combination of monomers, happens in this process. In contrast to combustion and gasification processes, which entail complete or partial material oxidation, pyrolysis involves heating in the absence of air. Since the process is primarily thermodynamic, effective energy content guarantees in the products. The temperature ranges from 500 to 600 degrees Celsius. The proposed technique breaks down polymer chains into monomers by using electrical power and microwaves (depolymerization). In this stage, depolymerization occured due to electrical power and microwave that allows breaking down the polymer chain into monomers. Pyrolysis products of waste polymers always produce parts containing solid gases, including coal, biochar, liquid, and incompressible materials (H2, CH4, CnHm, CO, CO2, and N). Because the liquid phase only removes from pyrolysis gas during the cooling down step, these two streams can be utilized simultaneously in some applications when supplying hot gas straight to the burner or oxidation chamber. Particles heat to a specified temperature during the pyrolysis process. Materials stay within the pyrolysis unit, where they are moved down a screw conveyor at a set speed until the process is complete. The chosen pyrolysis temperature defines the composition and yields of products (pyrolysis oil, gas, and char).

The exhaust gases then go to the Pwave + storage tank and enter the separator. After separating the heavy and light materials in this reactor, the resulting gases reach the catalyst chamber, decreasing the temperature. The condensers then cool the exhaust gases from the catalyst chamber area, and light and heavy hydrocarbons enter the storage tanks. In this process, gases have little ability to liquefy, such as ethane, butane, and propane, Etc., which also depends on the recycled materials used, and are stored in a separate tank and ready for sulfur removal if required for further treatment., For example, gases from the pyrolysis of tires have a large amount of sulfur that needs to be passed through a cyclone and a gas scrubber to generate the electricity required by the system. It should note that the electricity required by the system to start work to reach the possibility of using a gas generator in cases where there is no access to energy can don by storing solar energy. The hydrocarbons produced have different aromatic and aliphatic compounds depending on the polymers used in the reactor and separation operations for fuel or used in refineries.

3.5. Advantages of Pwave+ Technology

A modular technology can be swiftly deployed on the market and helps enhance the local current sorting facility's technology supply. The microwave pyrolysis consumes 15 times less energy and produces the heat required for recycling the waste polymer process than the standard pyrolysis method used in the world. When it comes to fuel production, the current performance reaches 95%, with a capacity of 100 kg per hour to 200 kg / h; a module can produce between 500 and 1000 tons per year. This technology is not cause any environmental pollution. Produced goods reduce greenhouse gas emissions by preventing the extraction of petroleum-based resources, saving 3 tonnes of greenhouse gases for every ton of processed plastics. Although the Pwave+ technology is primary development for treating waste polymers, it might also use to treat Agricultural Waste and other similar instances in the future. The Pwave+ microwave pyrolysis system used a continuous vortex reactor configuration designed to maximize heat transfer and polymer waste conversion. Carbon materials that strongly absorb microwave energy used as internal heating beds along with recycled gases to provide a self-sufficient energy source for the process [

27]. Various model and real-world polymer waste streams including plastics and tires collected and prepared by removing metals and separating into manageable fractions [

6]. The reactor system performance was modeled computationally and optimized experimentally by controlling parameters such as temperature, pressure, flow rates, power density and reactor geometry to improve microwave absorption, heating rates, pyrolysis reactions and product separations [

29].

Advanced instrumentation and automation were enabled monitoring, control and data-driven optimization of the process [

25]. Modular and transportable system design allowed capacity scaling to suit different throughput requirements [

31]. The expected outcomes are an energy-efficient continuous microwave pyrolysis system able to sustainably transform diverse polymer waste streams into valuable fuels, chemicals and gases.

4. Results and Discussions

This investigation focuses on the utilization of state-of-the-art microwave and analytical systems in the recycling of polymer waste. Initially, mechanical recycling systems play a significant role in waste separation processes. Various aspects of processing and materials science are explored, each posing challenges to the technologies associated with mechanical recycling and system efficiency. These challenges aim to prevent the introduction of pollutants and ensure effective separation of polymers from other waste materials. The effects of optimization in utilizing recycled materials, considering different material types and price fluctuations, along with their limitations within specific scenarios, directly impact the quality of the resulting output product. These limitations further motivate and spark interest in the less commonly practiced chemical recycling approaches.

Within this study, different approaches for converting polymer waste into granules of specific dimensions have been examined. These approaches offer the potential to generate chemical products such as fuels or various polymers that exhibit similar performance and characteristics to the required raw materials. Additionally, there are instances where the separation of materials is technically and economically infeasible, thus necessitating alternative methods for recycling heterogeneous and contaminated polymer waste that possess greater potential for effective material recovery.

Pyrolysis of polymer waste aims to optimize the system and use the microwave to recover the value of this high-volume waste in the form of valuable products such as light and heavy hydrocarbons and electricity generation. The most significant achievements of this system and the goal of this study is to achieve a portable system with high efficiency and energy supply of the system itself. Furthuremore, the majority of this technique beneficial and dis advantages are chractrized in the

Table 1 and

Table 2.

4.1. Design and Optimization of a Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis System (Pwave+)

In this chapter, the focus is on the design and optimization of a microwave-assisted pyrolysis system. The aim is to develop an efficient and effective system for the pyrolysis process, considering various factors and parameters.

The chapter explores different aspects of system design, including reactor design, selection of microwave power and frequency, and optimization of operating parameters. The goal is to achieve optimal pyrolysis conditions, ensuring maximum waste polymer conversion into desired products. Furthermore, this part delves into modeling and simulation techniques to aid design and optimization. Through computer-aided simulations, the performance and efficiency of the system can be evaluated and improved.

Key performance indicators are evaluated to assess the system's effectiveness, and optimization algorithms are employed to fine-tune the system parameters. The aim is to optimize the process in terms of product yield, energy efficiency, and overall system performance.

Overall, this chapter presents a comprehensive approach to designing and optimizing a microwave-assisted pyrolysis system, aiming to maximize the conversion of waste polymers into valuable products while minimizing energy consumption and environmental impact.

4.2. Thermal Behavior of Waste Polymers under Microwave Irradiation

This section presents the findings from an investigation into the thermal characteristics of diverse waste polymers when exposed to microwave irradiation. The experiments were conducted using a microwave pyrolysis setup known as Pwave+, and key parameters such as temperature profiles and weight loss curves of the polymer samples were carefully monitored. The impact of several factors, including polymer composition, heating rate, and irradiation duration, on the pyrolysis process was analyzed and extensively discussed. The data derived from these experiments were utilized to ascertain the optimal conditions for achieving efficient polymer pyrolysis.

The primary focus of studying the thermal behavior of waste polymers under microwave irradiation is to gain insights into how different types of waste polymers respond when subjected to microwave heating during the pyrolysis process. The section provides a comprehensive explanation and exploration of the subject matter encompassing the following aspects:

Experimental setup: The experimental setup used for microwave pyrolysis of waste polymers is described, including details of the microwave pyrolysis reactor, sample preparation, and measurement instrumentation used to monitor temperature and pressure changes.

Waste polymers samples: The following tables specify the results of the polymer materials used in the tests, which investigated each polymer's characteristics after microwave pyrolysis.

Pyrolysis optimization parameters in this research's designed and manufactured device, which include temperature changes over time for each polymer sample, are recorded and checked by the monitoring system. This includes any observed changes in pressure-temperature behavior, such as differences in heating rate, peak temperature, and stabilization period.

4.3. Experimental Procedures and Set Up

For instance, the experimental set up procedures occurred during the lab and it is known that Designing and constructing a pilot-scale microwave-assisted pyrolysis system with appropriate safety measures and control systems.

According to the

Figure 10 the Made parts define as Made parts; Connections, Filters placement flanges, structure, chamber. Furthuremore, the special parts are made by the authors too. This part contributed to Sparger to prevent the passage of heavy materials in the pyrolysis gas and adjust the inlet pressure to the system that also reveals in

Figure 11.

4.4. Simulation and Programming to Optimize System Design

Microwave pyrolysis, as a promising waste treatment technology, shows great potential. The Pwave+ research specifically explores the utilization of microwave-assisted pyrolysis for a mixture of waste polymers along with additional impurities. The process generates a diverse array of compounds, which was effectively demonstrated through analysis. It is worth noting that the resulting condensate could potentially serve as a transportation fuel. However, in certain applications, the aromatic fraction might need to be eliminated to meet the prescribed restrictions on these chemicals. The aromatic fraction possesses significant value due to its properties as a solvent and a precursor for various chemicals, including pharmaceuticals, lubricants, detergents, and polymers such as polystyrene and polycarbonate. Additionally, it finds application in explosives. The amorphous nature and surface morphology of the char make it suitable for utilization as a component in tar formulations or in systems requiring substantial amounts of carbon derived from the pyrolysis of polymer waste. The resulting carbon has a substantial volume that can be independently activated to yield valuable products, including activated carbon. Despite numerous studies conducted on microwave pyrolysis, the progress in industrial thermal heat applications has been hindered by a lack of comprehensive comprehension regarding microwave systems. Furthermore, there is insufficient precise information available in the existing resources to facilitate accurate economic evaluations of alternative pyrolysis processes for making meaningful comparisons in terms of economic viability. By employing meticulously designed microwave pyrolysis, which introduces novel and inventive techniques, it becomes feasible to recycle substantial quantities of plastic waste, tires, and agricultural waste. The resulting end product can serve as a viable substitute for conventional fossil fuels. Leveraging the advantages of microwave waves, this system presents a cost-effective and environmentally friendly design. Consequently, if the objective is to convert waste tires and polymers into hydrocarbon fuels, an appropriately implemented microwave pyrolysis process can achieve that purpose efficiently.

This study performed the simulation by CAD software such as Comsol Multiphysics and Ansys and Advance Design systems and also evaluate the behavior of the system and outcomes. Also the programming is also dine by Matlab and Mathematia software.

After the research progress, the optimized Pwave+ system is expected to convert up to 80-90% of the polymer waste feedstock into useful pyrolysis oil and gas products, leaving behind a solid char residue [

32]. The oils are anticipated to contain various hydrocarbon fractions and aromatics that can be purified into transportation fuels or petrochemicals [

33]. The gases contain combustible light hydrocarbons that recycled to provide energy self-sufficiency to the microwave pyrolysis process.

The results provides insights into the technical and economic feasibility of continuous microwave vortex reactors for recycling mixed polymer wastes compared to current pyrolysis methods [

34]. Data on the relationships between microwave power, reactor geometry, waste composition, temperature profiles and product distributions have analyzed to create performance models and optimization strategies for the reactor [

35]. Limits and considerations for scale-up and commercial implementation also explored.