1. Introduction

The hospital sector in Germany generates approximately 1.2 million tons of waste annually, much of which consists of single-use plastic products that are currently incinerated. Five years ago, we established a cross-disciplinary expert group—cross-industry cooperation—dedicated to advancing the circular economy in medicine [

1]. The group operates under the legal framework of the non-profit association Ecology and Sustainability in Medicine e.V. and pursues the goals of waste reduction and high-quality plastic recycling from central operating rooms.

By introducing operating room surgical trays, we replaced the otherwise double-packaged medical products with tray-based packaging [

2]. Scientific comparison with the standard approach demonstrated a 34% reduction in waste weight, a 32% reduction in waste volume, and a 43% reduction in operating room setup time. In addition, the use of trays significantly improved operating room staff satisfaction, achieving an average score of 9.74 out of 10 in the study. To further enhance resource efficiency, the residual plastic waste from the trays was assessed for recyclability using thermochemical recycling. The aim of this study was to convert a standardized plastic fraction into synthetic oil.

2. Materials and Methods

A defined waste stream based on TUR trays was used as the input material. These trays originated from a prospective study comparing procedure-specific tray systems (sterile packs containing predefined medical devices) with the standard approach in the operating room.

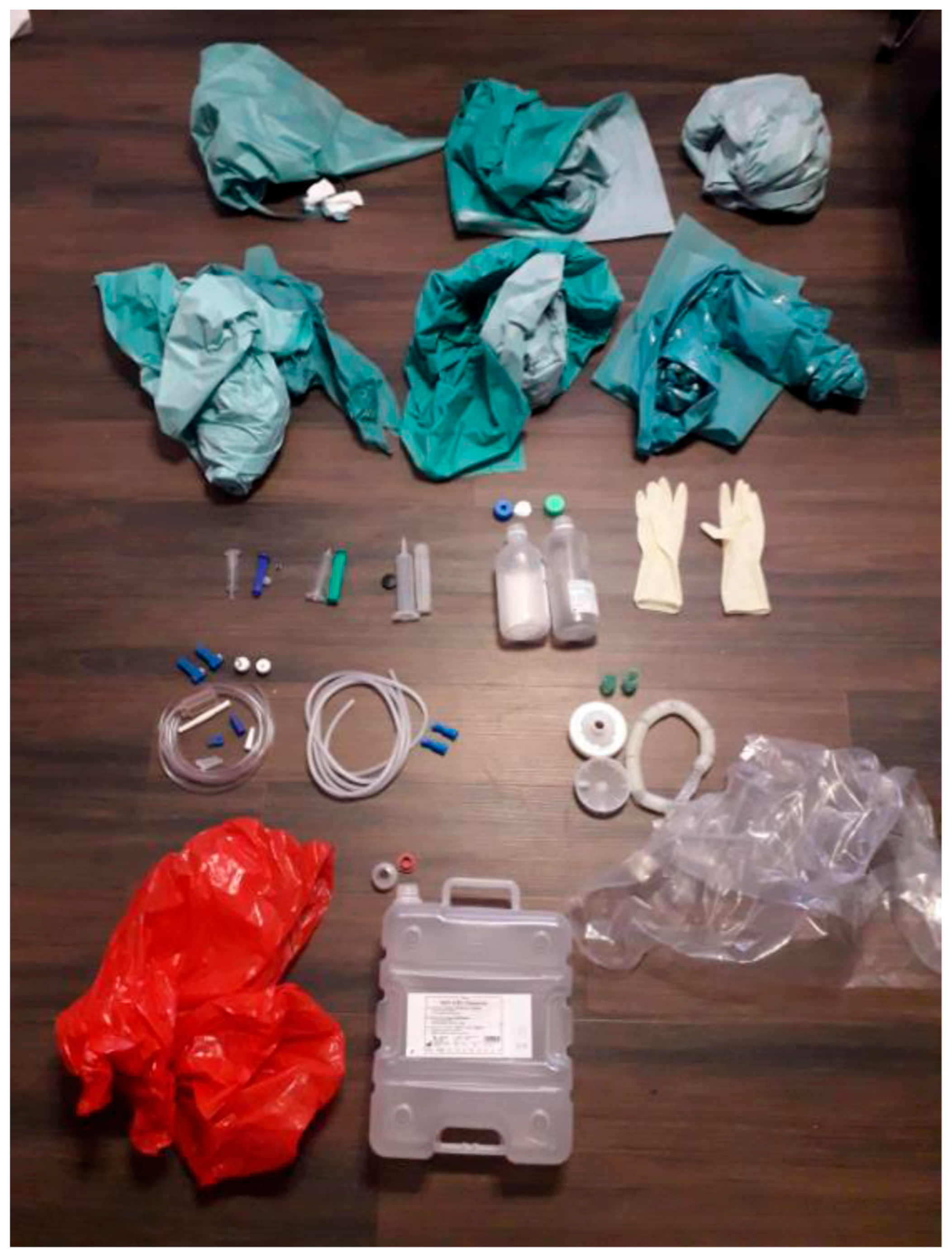

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the residual waste from a single TUR tray following one operation (transurethral resection of the prostate adenoma).

The pyrolysis of this residual waste was carried out by Next Generation Elements GmbH (NGE, Feldkirchen, Austria) using a standardized thermochemical recycling process [

2]. A total of four pyrolysis oils obtained from trays of the above-mentioned study were subjected to detailed chemical characterization. The analyses were performed by the Institute for Mineral Oil Products and Environmental Analysis GmbH (Klosterneuburg, Austria), employing established protocols for the evaluation of pyrolysis-derived hydrocarbons.

At the SynLab AG (Munich, Germany) pyrolysis facility, a batch pyrolysis reactor is used in which the temperature can be continuously adjusted up to 500 °C (

Figure 3). During the process, plastics or plastic mixtures are primarily converted into the gas phase to obtain high-quality oils. Materials that are not transferred into the gas phase remain as coke (solid fraction) in the reactor. The non-condensable gases generated are directed to the in-house ventilation system. Based on the laboratory experiments, a mass balance of feed, oil, coke, and gas can be determined. These results provide an indication of the suitability of the investigated input material for producing pyrolysis oil for the medical device industry.

The input material (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), derived from the TUR tray, is introduced into the reactor vessel (

Figure 3) and heated in the absence of oxygen to a temperature range of 430–460 °C. Under these conditions, the material decomposes into smaller molecular chains, generating pyrolysis gas. Components that do not transition into the gas phase remain in the reactor as solid residue, forming the so-called coke phase, which can be collected after the reactor has fully cooled.

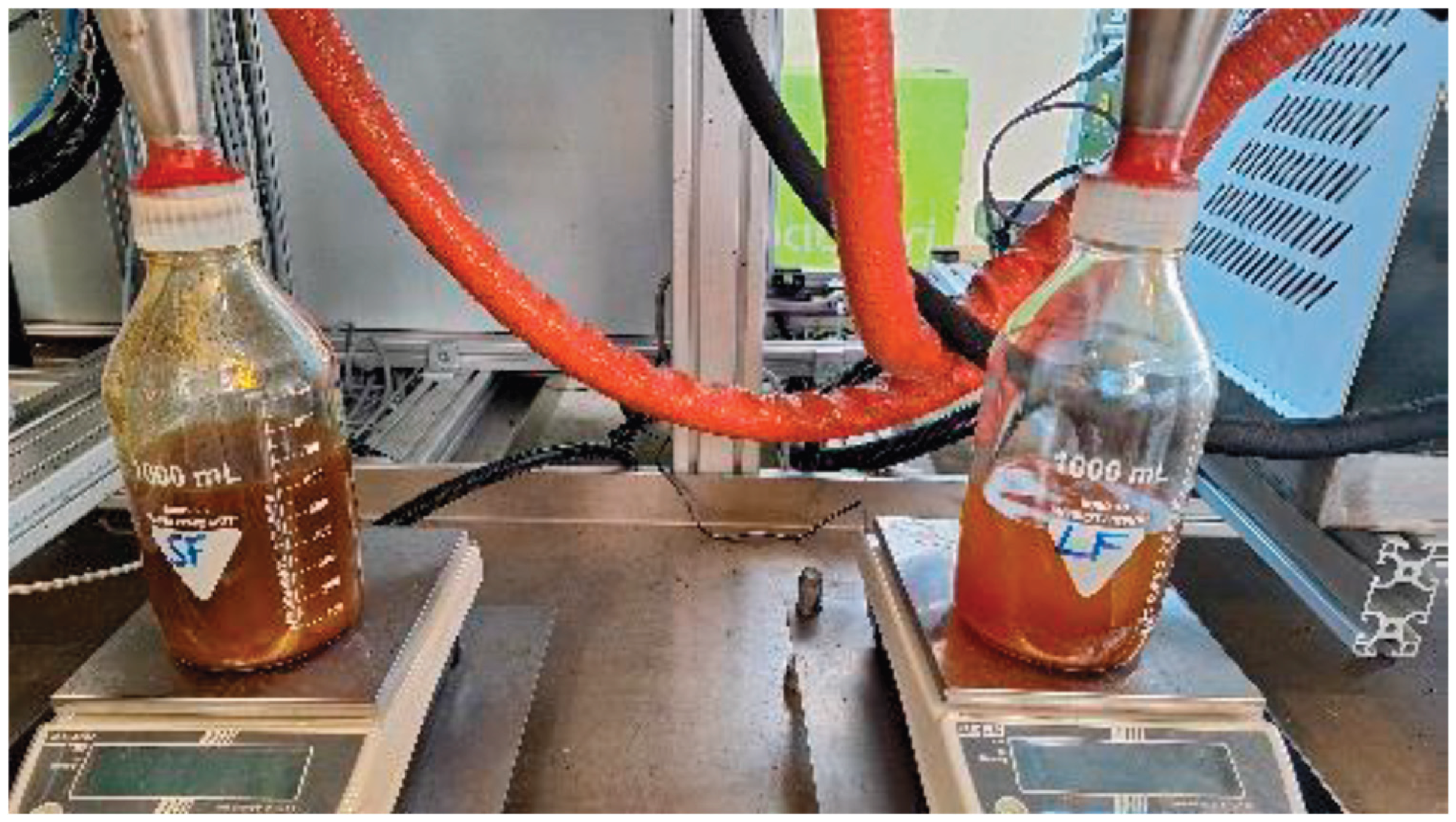

Pyrolysis gases are divided into condensable and non-condensable fractions. In the subsequent step, the pyrolysis gas is passed through two heat exchangers (condensation stages 1 and 2) at different temperatures. This process yields heavy oil (HF) and light oil (LF) fractions (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), which are regarded as products suitable for further processing in downstream industrial sectors. The remaining non-condensable gases that cannot be liquefied after the second condensation stage are directed through a water lock and subsequently discharged via the general ventilation system.

The workflow comprised several key steps, from material preparation to fraction collection and post-experimental analysis, as outlined below:

Loading of the material into the batch reactor (maximum capacity 3.0 kg; here: 1.102 kg,

Figure 2 and

Figure 6).

Heating of the material in the reactor at a rate of 150 °C/h.

After reaching the required pyrolysis temperature after 4 hours, the pyrolysis gas condensed into heavy oil and light oil fractions, which were collected in 1-liter glass bottles (

Figure 7).

The coke fraction remained as hazardous waste and, after complete cooling of the experimental setup on the following day, was collected and analyzed.

3. Results

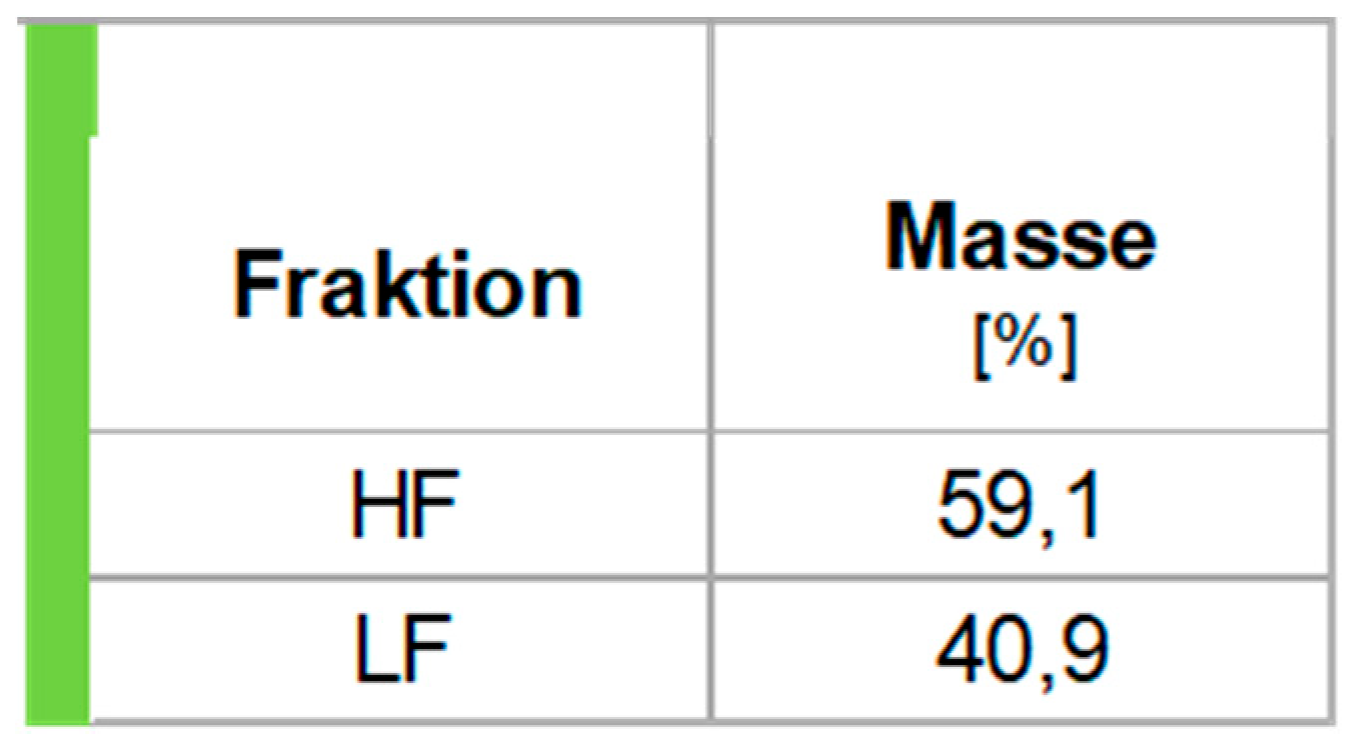

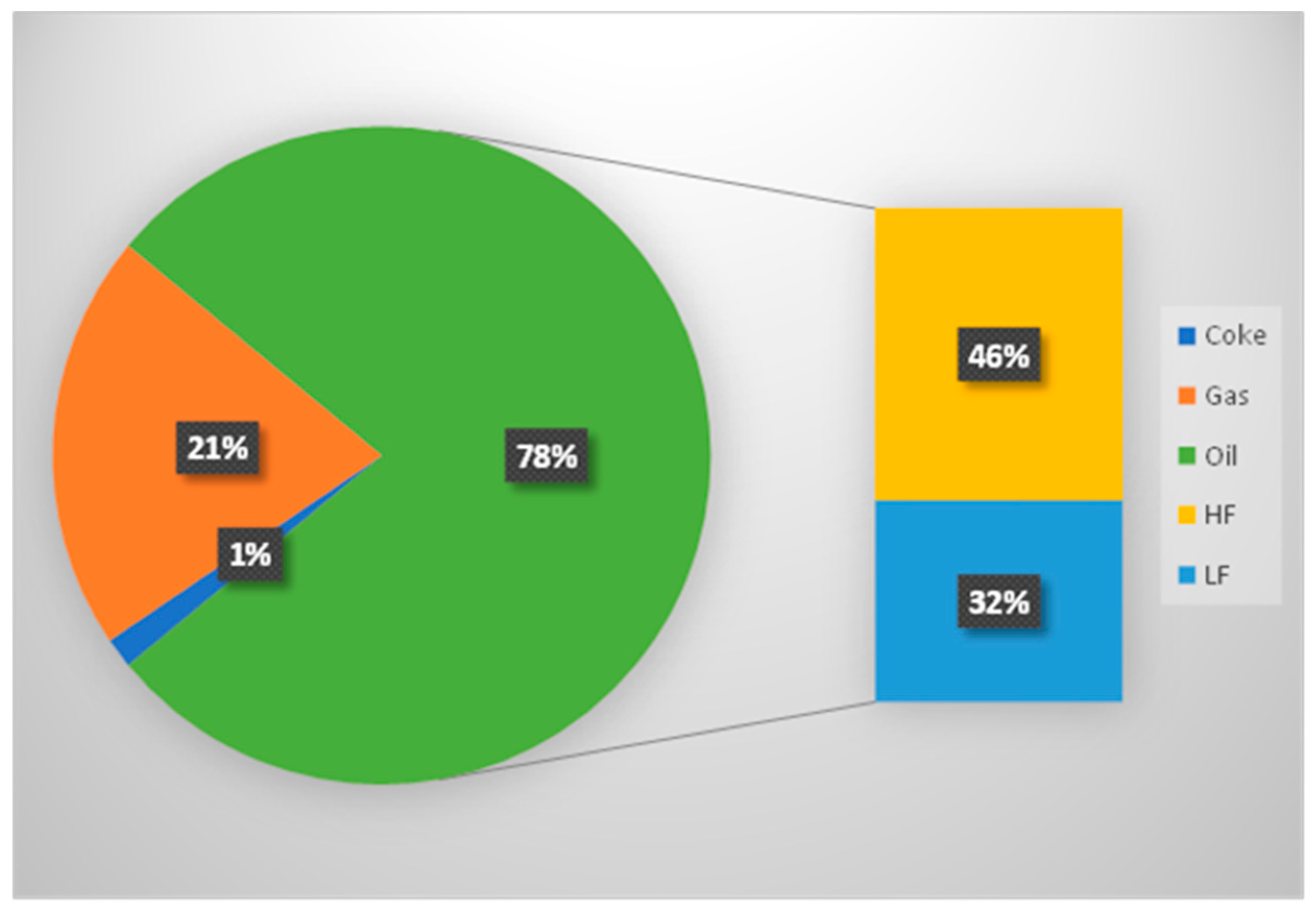

All fractions obtained were documented by final weighing, enabling the determination of the mass balance of the pyrolysis process. The relative mass percentages of the heavy fraction (HF) and light fraction (LF) were calculated based on the total yield of “sum oil” (

Figure 4).

The heavy fraction of the pyrolysis oil solidified into a wax-like consistency at room temperature, indicating the presence of longer hydrocarbon chains. In contrast, the light fraction remained liquid, suggesting shorter hydrocarbon chains.

The coke residue emitted a faint odor reminiscent of pyrolysis oil, albeit only in subtle traces. This confirms that the reaction temperature of 450 °C was sufficient for a successful pyrolysis process. At higher temperatures, a larger proportion of gas is typically produced, thereby reducing the overall oil yield. Since the objective was to maximize oil recovery, the temperature was set at 450 °C. With a mass fraction of 1.5%, the coke content can be considered low (

Figure 5).

3.1. Chemical Analysis

3.1.1. Density of the Fractions

The density of the heavy fraction (HF) was 767.0 kg/m³, while that of the light fraction (LF) was 748.9 kg/m³. Compared with previous trials, the oil fractions fall within the expected range. For comparison, the density of gasoline lies between 720–775 kg/m³, and that of diesel between 820–845 kg/m³ [

3].

3.1.2. Acid Number (AN)

The acid number of HF was 3.14 mg KOH/g, whereas LF showed a higher value of 10.10 mg KOH/g.

3.1.3. Water Content of the Fractions

HF showed a water content of 0.011 wt%, while LF contained approximately 0.041 wt%. Both values can be regarded as low, which represents a favorable characteristic for pyrolysis oil.

3.1.4. Higher Heating Value (HHV)

The HHV of HF was 46.39 MJ/kg and that of LF 46.80 MJ/kg. These values are comparable to those reported in the literature and previous trials. Importantly, they exceed the heating value of a conventional heat transfer oil (42–45 MJ/kg).

3.2. Elemental Analysis

A total of 23 elements were analyzed using atomic emission spectrometry. In both fractions, only phosphorus and silicon were detected at concentrations >1 mg/kg, while all other elements were negligible.

Silicon primarily originates from silicone-based input materials. To reduce the Si content, separation of these feedstocks prior to pyrolysis could be considered. Nevertheless, both P and Si levels are acceptable and do not represent exclusion criteria for the further use of pyrolysis oil in medical device applications.

3.3. CHNS Analysis

The CHNS results were unremarkable and did not deviate from values reported for other pyrolysis oils.

3.3.1. Chloride Content in LF

The chloride content of LF was 110 mg/kg. This level can be considered low. Although chloride is regarded as a problematic component in steam cracking processes, critical thresholds vary among companies and are not standardized.

3.3.2. Boiling Range Distribution

Gas chromatography was conducted to determine the boiling range distribution of the fractions. The boiling point curves of both HF and LF were in line with expectations, confirming the presence of hydrocarbons with varying molecular chain lengths.

4. Discussion

The pyrolysis temperature of 450 °C effectively eliminates any risk of biological contamination in the recycled oil, thereby addressing one of the major arguments against the use of biologically contaminated single-use medical products for the production of new medical devices. The decisive factor, however, is the quality of the pyrolysis product. The experiment met expectations for generating a high-quality and usable pyrolysis oil. From 100% hazardous waste, 78% oil was recovered, with a higher yield of heavy fraction compared to light fraction. The low coke content (1.5%) and the calculated gas fraction (20.5%) complement the overall mass balance. Importantly, the produced pyrolysis gas could potentially be applied in processes aimed at producing plastics for medical devices from a quality perspective.

The remaining coke fraction, representing 1.5% of the total mass, must be treated as hazardous waste and disposed of properly. Chemical analysis confirmed that the pyrolysis oils did not contain significant contamination originating from the medical products. The chloride and silicon contents, as well as the coke fraction, could be further reduced by improved presorting of the input material, thereby enhancing oil quality. This was addressed in our concept of using OR sets/trays containing only pyrolysis-suitable medical products. A subsequent sorting and collection system further optimized the input material.

Other recycling approaches cannot currently enable a true circular economy for medical products, since the risk of contamination remains a limiting factor in mechanical recycling. A commonly raised concern regarding pyrolysis relates to its economic and ecological implications, particularly the energy demand required to sustain the process.

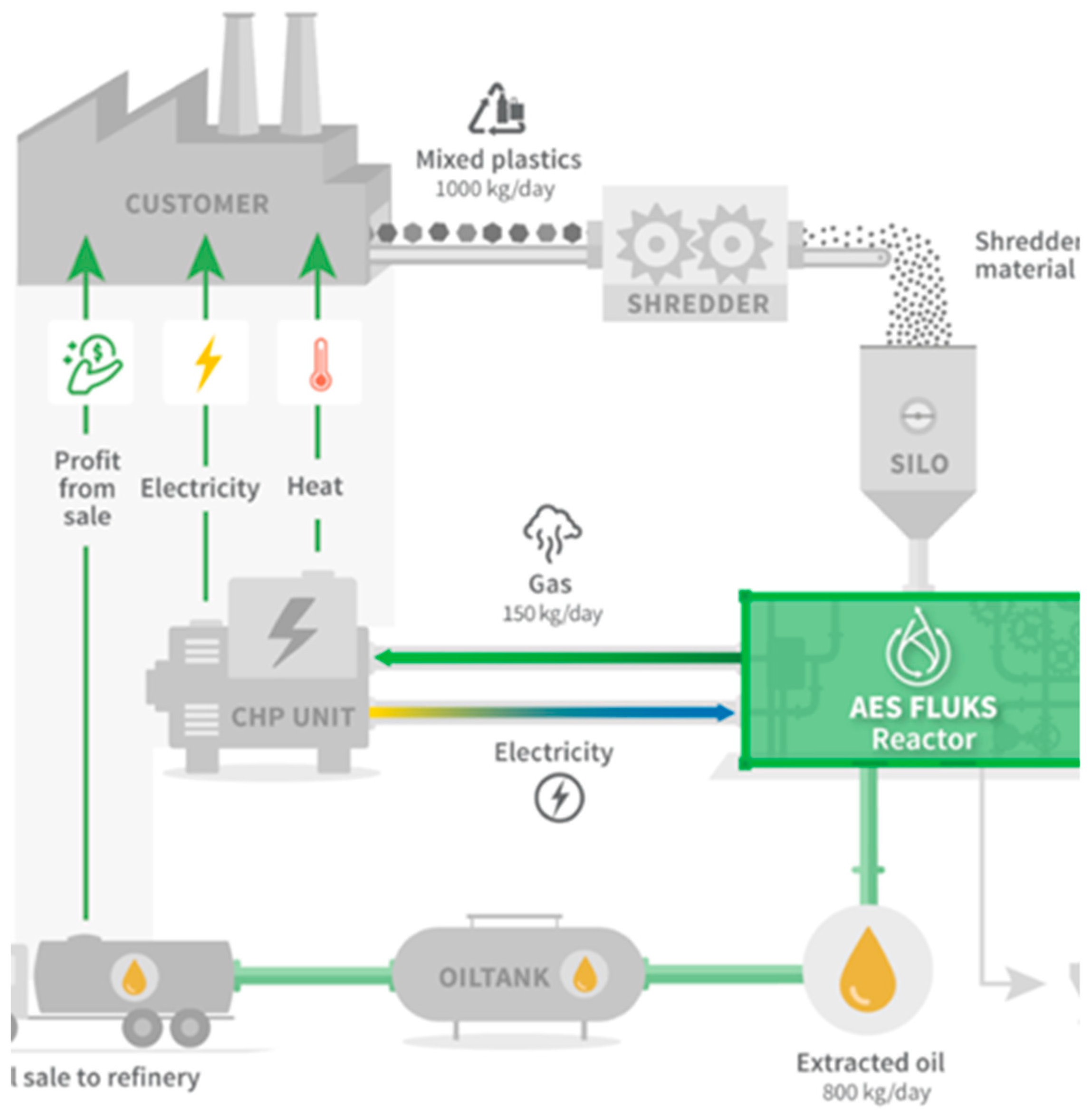

Our approach effectively addresses the commonly raised concerns regarding pyrolysis and provides the following advantages:

Energy efficiency: The pyrolysis facility utilizes the process gases to generate energy through an integrated combined heat and power (CHP) unit. This reduces the external energy demand of the plant by up to 75%.

Noise reduction: An enclosed shredder design minimizes noise emissions to LDEN < 50 decibels.

CO₂ savings: For every ton of plastic waste processed, approximately 2.9 tons of CO₂ emissions are avoided compared with conventional incineration. For the first pilot plant with a capacity of 350 tons, this corresponds to an annual reduction of more than 1,000 tons of CO₂.

High recovery rate: The overall material recovery rate exceeds 70%.

Complete decontamination: The pyrolysis process ensures 100% elimination of biological contamination.

Sustainability and certification: The resulting pyrolysis oil is ISCC+ certifiable and can be used as a raw material for the production of new medical devices, thereby replacing or complementing fossil-based crude oil.

Medical plastic waste is currently almost exclusively incinerated—resulting in high emissions. Our concept reverses this logic: waste becomes a valuable resource. Instead of extracting fossil raw materials, we recover high-quality pyrolysis oil from standardized surgical trays—directly on site, in modular plants, with minimal effort (

Figure 6). This approach represents a synergistic combination of two R-strategies: Reduce and Recycle. The use of trays reduces plastic packaging consumption in the operating room by 34% (R2 of the R-strategies). Subsequent utilization of the pyrolysis oil for the production of new medical devices represents true circular economy (R8 of the R-strategies).

The market potential for this pyrolysis approach is considerable: with a conservatively estimated waste volume of 20 t/clinic/year, Germany alone generates more than 14,000 t of medical plastic waste annually—currently largely unused. By closely linking hospitals, logistics providers, waste management companies, regulatory authorities, and material manufacturers, a fully circular value chain emerges—planned, scalable, and sustainable. Our expert group “Circularity in Medicine” represents this value chain and has formally established itself as the association Ökologie & Nachhaltigkeit in der Medizin e.V.

The project was systematically developed under ecological criteria. The trays used are deliberately substituted with materials of high recyclability. A life cycle assessment and technical validation support the concept. Implementation takes place under consideration of regulatory, hygienic, and logistical requirements. The concept, based on standardized trays and their patented collection system, can be scaled to many other sites.

The economic benefits of the proposed concept extend across all stakeholders. Hospitals benefit from cost reductions through waste minimization, while plastic waste is converted into valuable resources; in addition, the adoption of such a system provides a marketing advantage as a “Green Hospital”, attractive to both staff and patients. Tray manufacturers profit from the distribution and use of eco-designed trays specifically developed for recycling. Medical device manufacturers are able to meet the recycling quotas mandated by the EU-MDR, thereby strengthening and securing their market positions. Finally, pyrolysis plant operators gain direct economic value through the sale of recycled oil.

This project based on the pyrolysis of medical plastics transforms sustainability from a regulatory obligation into a clinically verifiable reality. It creates the opportunity for every hospital to become an active part of the circular economy.

5. Conclusions

Pyrolysis of medical plastics offers a viable pathway to transform waste into valuable resources, turning sustainability from a regulatory requirement into a clinically verifiable reality. This approach enables hospitals to actively participate in the circular economy while supporting emission reduction and resource efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P., A.P., B.H., D.B., C.H. and T.O.; methodology, N.P. and T.O.; software, N.P.; validation, D.B. and T.O.; formal analysis, N.P., A.P., B.H. and C.H.; investigation, N.P. and B.H.; resources, N.P., A.P., B.H. and C.H.; data curation, N.P. and T.O.; writing—original draft preparation N.P., D.B. and T.O.; writing—review and editing, D.B. and T.O.; visualization, D.B.; supervision, A.P., B.H., C.H. and T.O.; project administration, N.P. and T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

no ethical review is needed as no patient data ws involved.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection regulations, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Thomas Otto, on behalf of the Expert Group on Ecology and Sustainability in Medicine e.V. Special thanks to Stefan Welter (Department of Thorax Surgery, DGD Lungenklinik Hemer, Germany), Markus Grunow (Farco-Pharma GmbH, Cologne, Germany), Stefan Lomberg (Mittelstands und Wirtschaftsvereinigung der CDU Mühlheim, Germany) and Jochen Cramer (Visualization and Sustainability, Micro-Tech Europe GmbH, Germany). This article was prepared without digital/AI assistance. For the English translation, a translation program was used, followed by review and correction by the author. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TUR |

Transurethral resection |

| HF |

Heavy fraction |

| LF |

Light fraction |

| AN |

Acid number |

| HHV |

Higher heating value |

| CHNS |

Carbon, Hydrogen, Nitrogen, and Sulfur |

| KOH |

Kaliumhydroxid |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).