Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

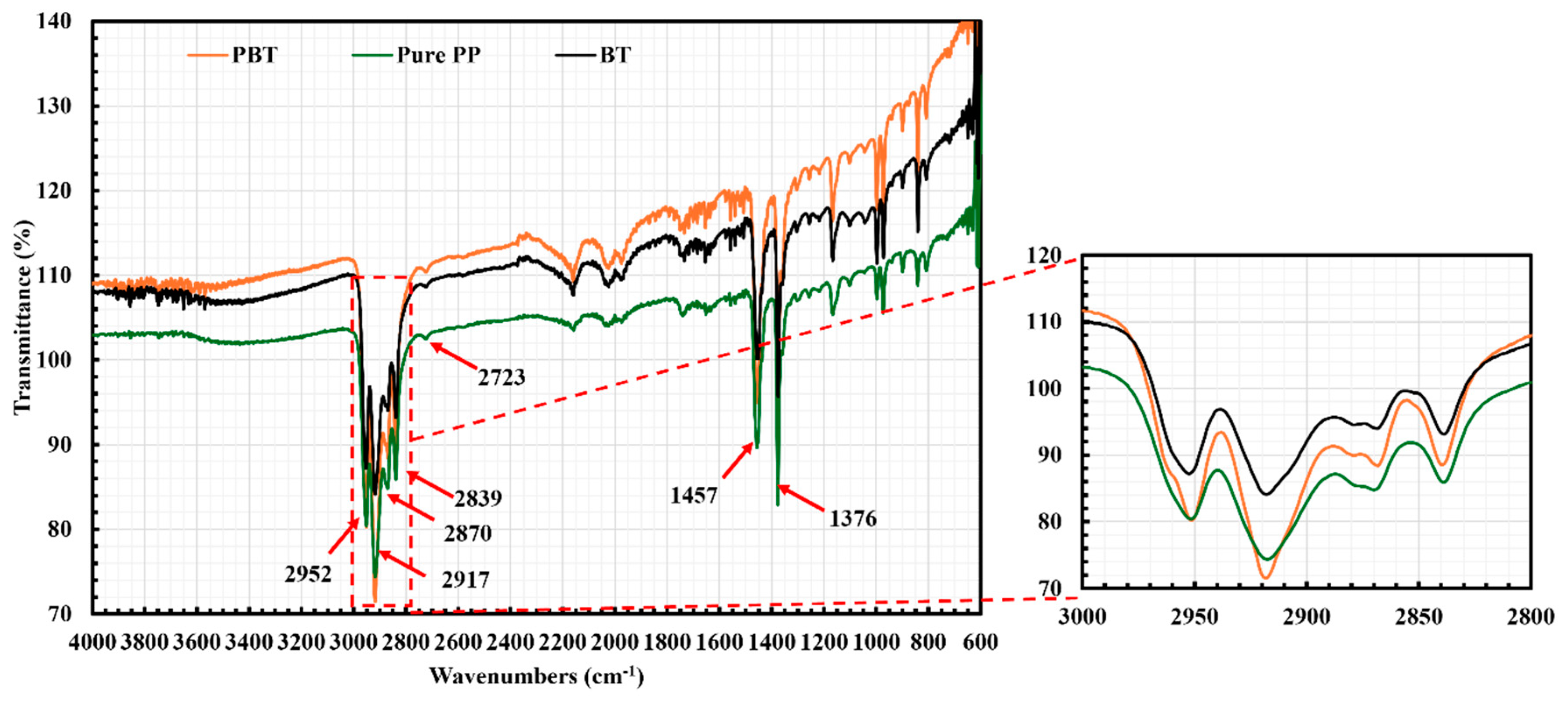

2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

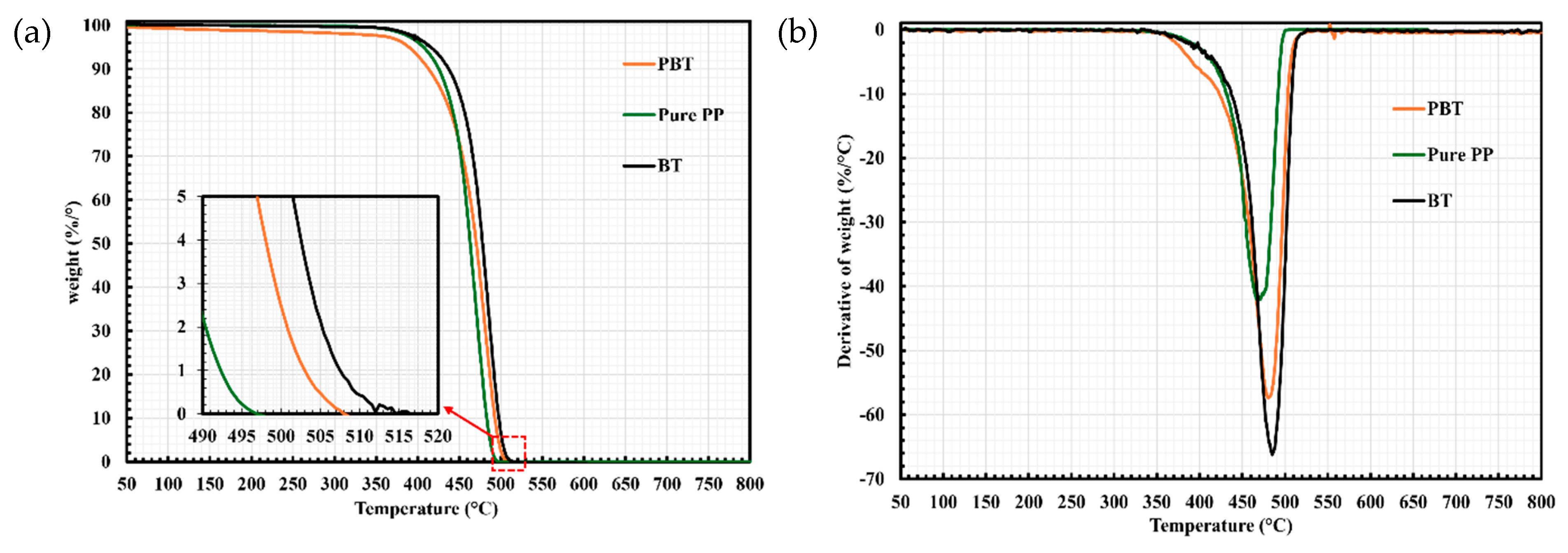

2.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

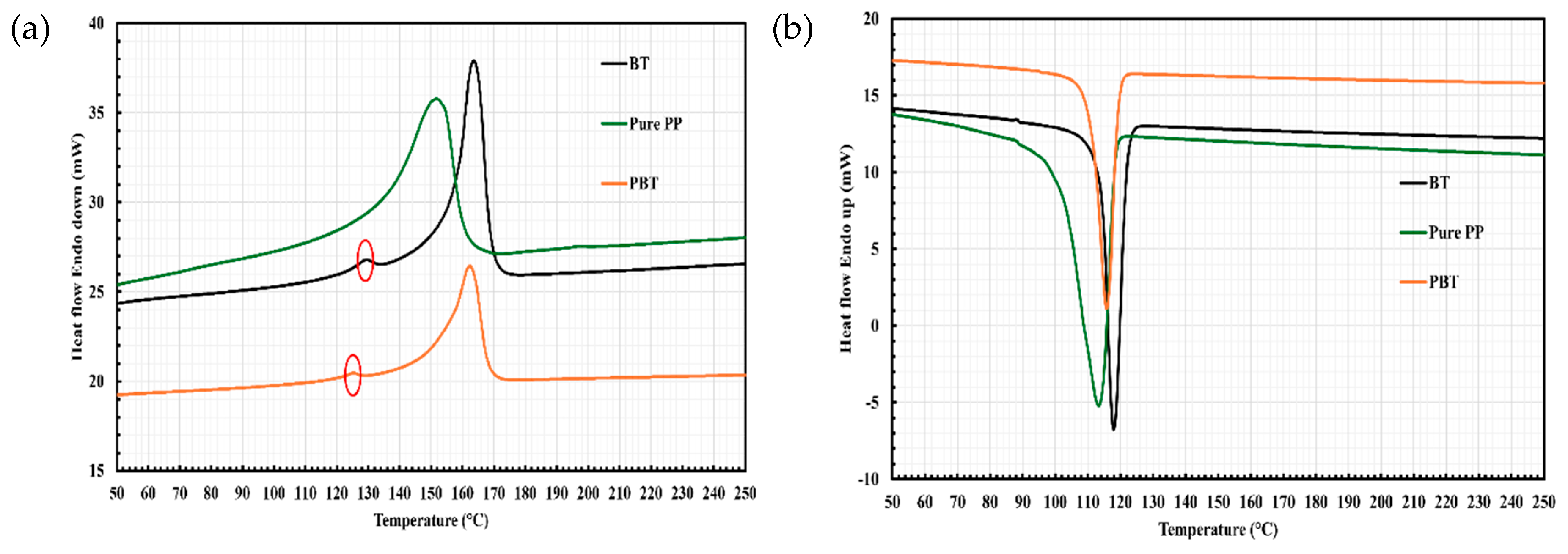

2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

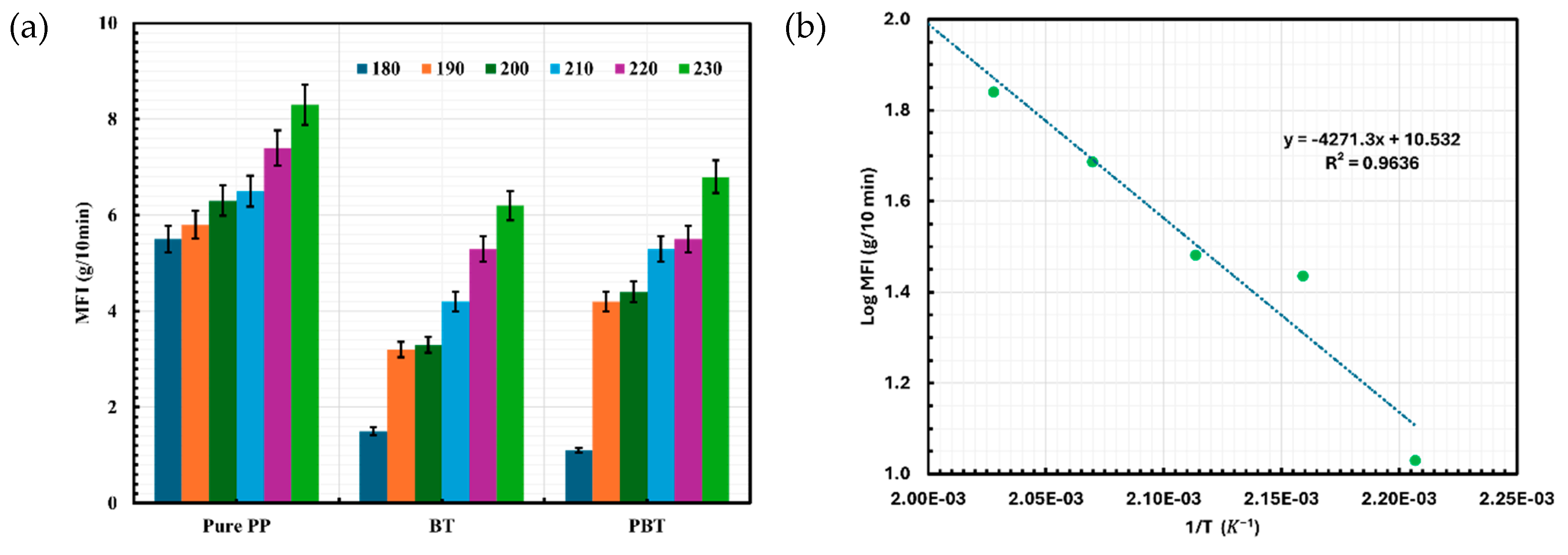

2.4. Melt Flow Index (MFI) Analysis

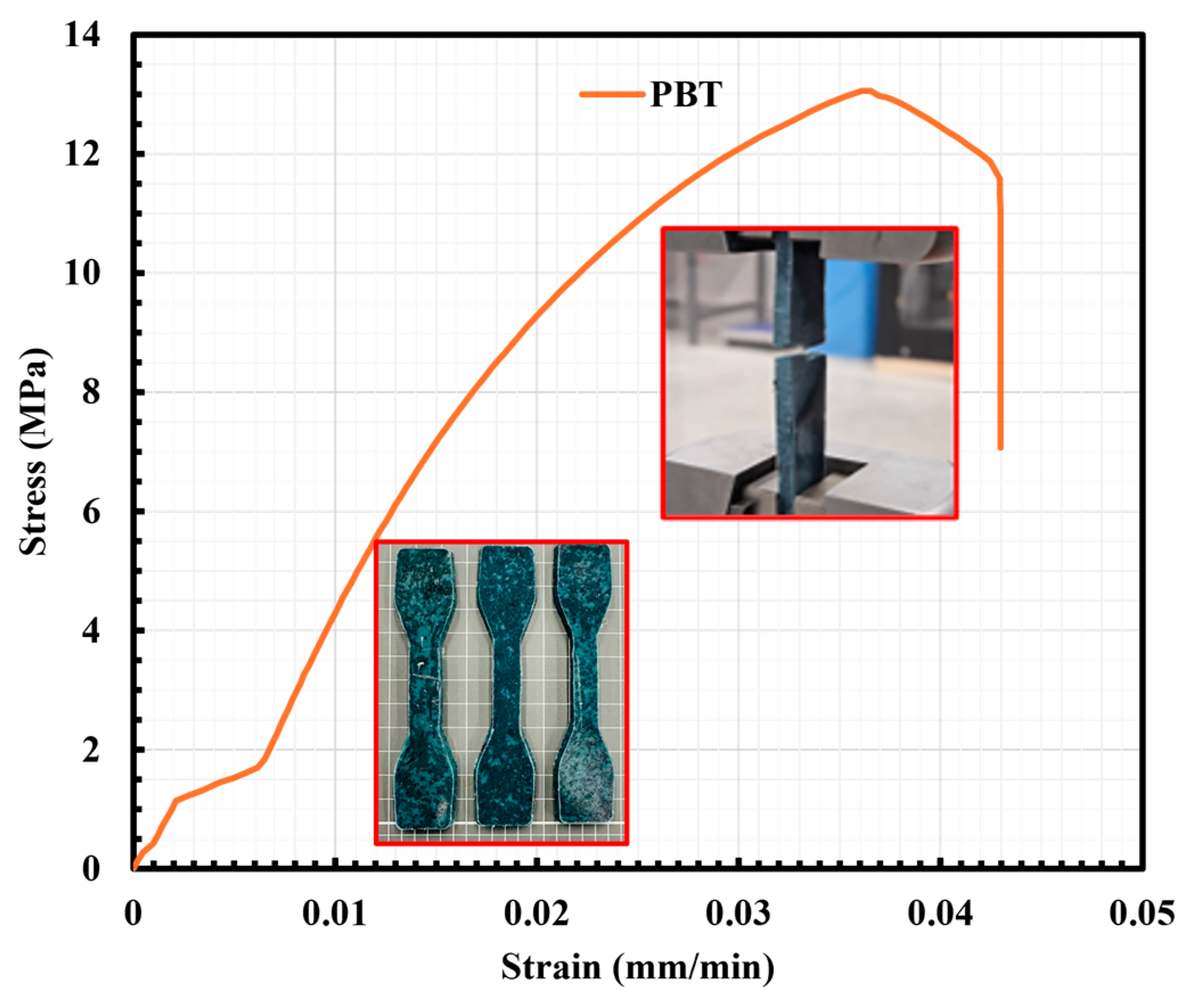

2.5. Mechanical Properties

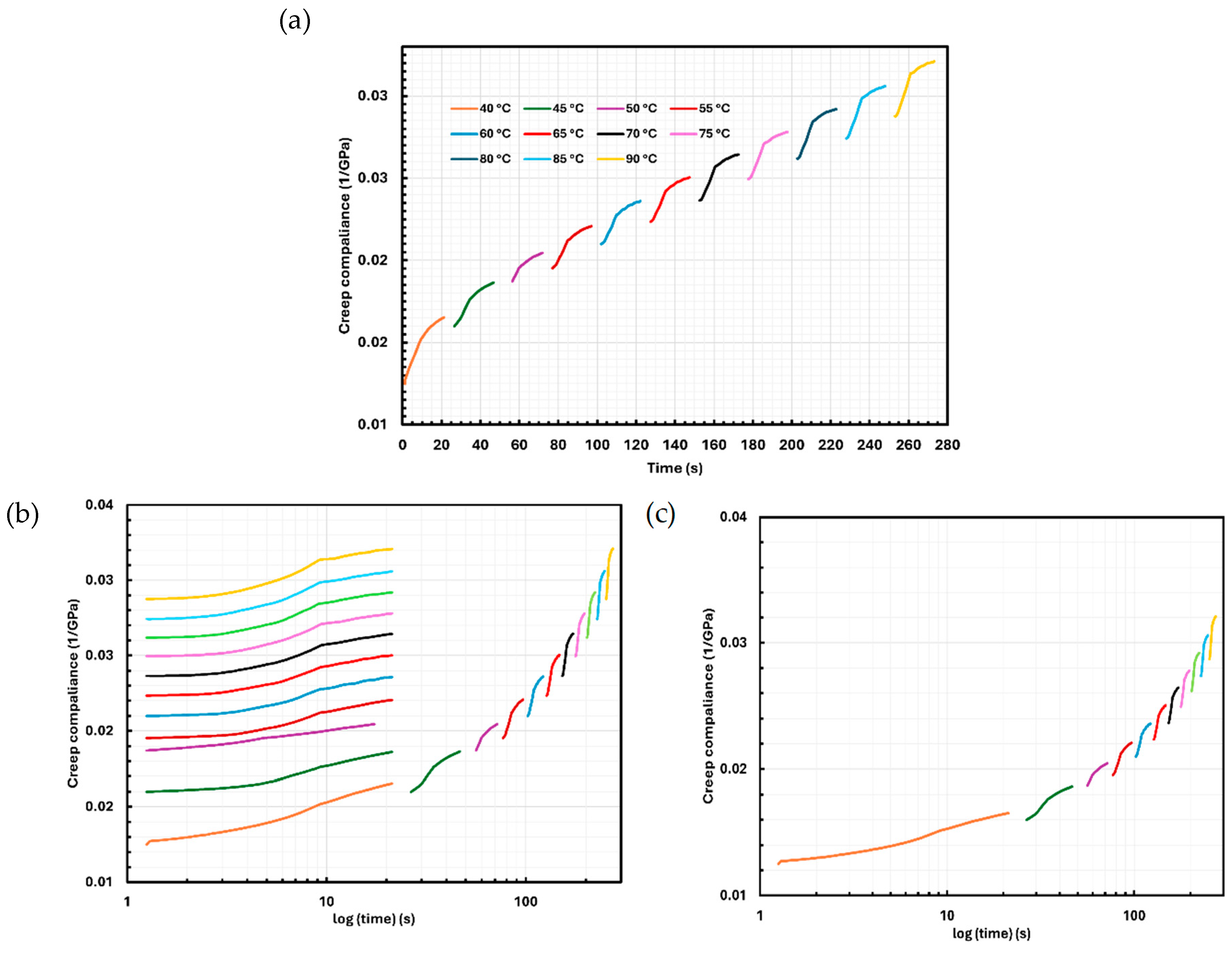

2.6. Creep Analysis

2.7. Water Contact Angle

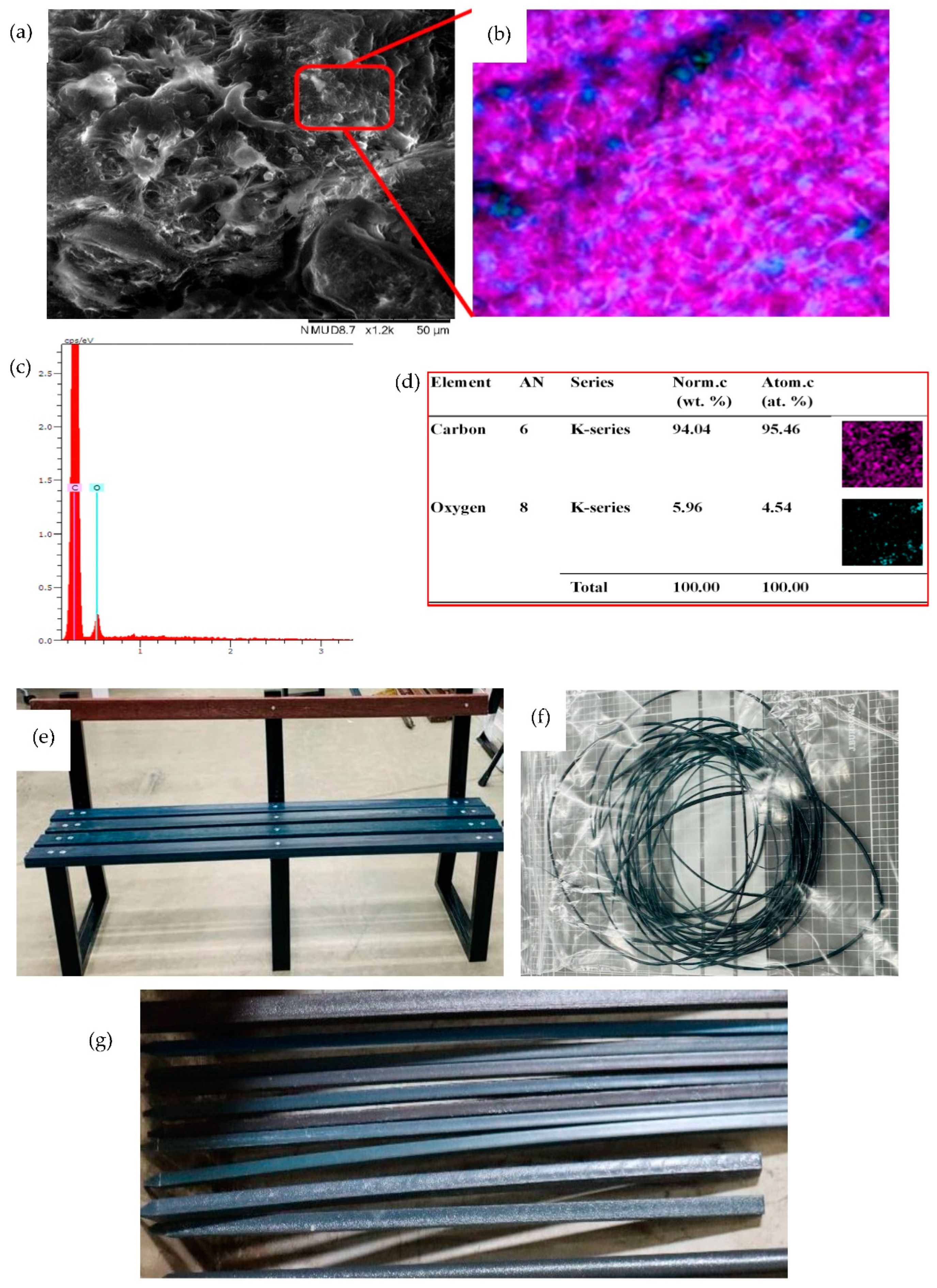

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

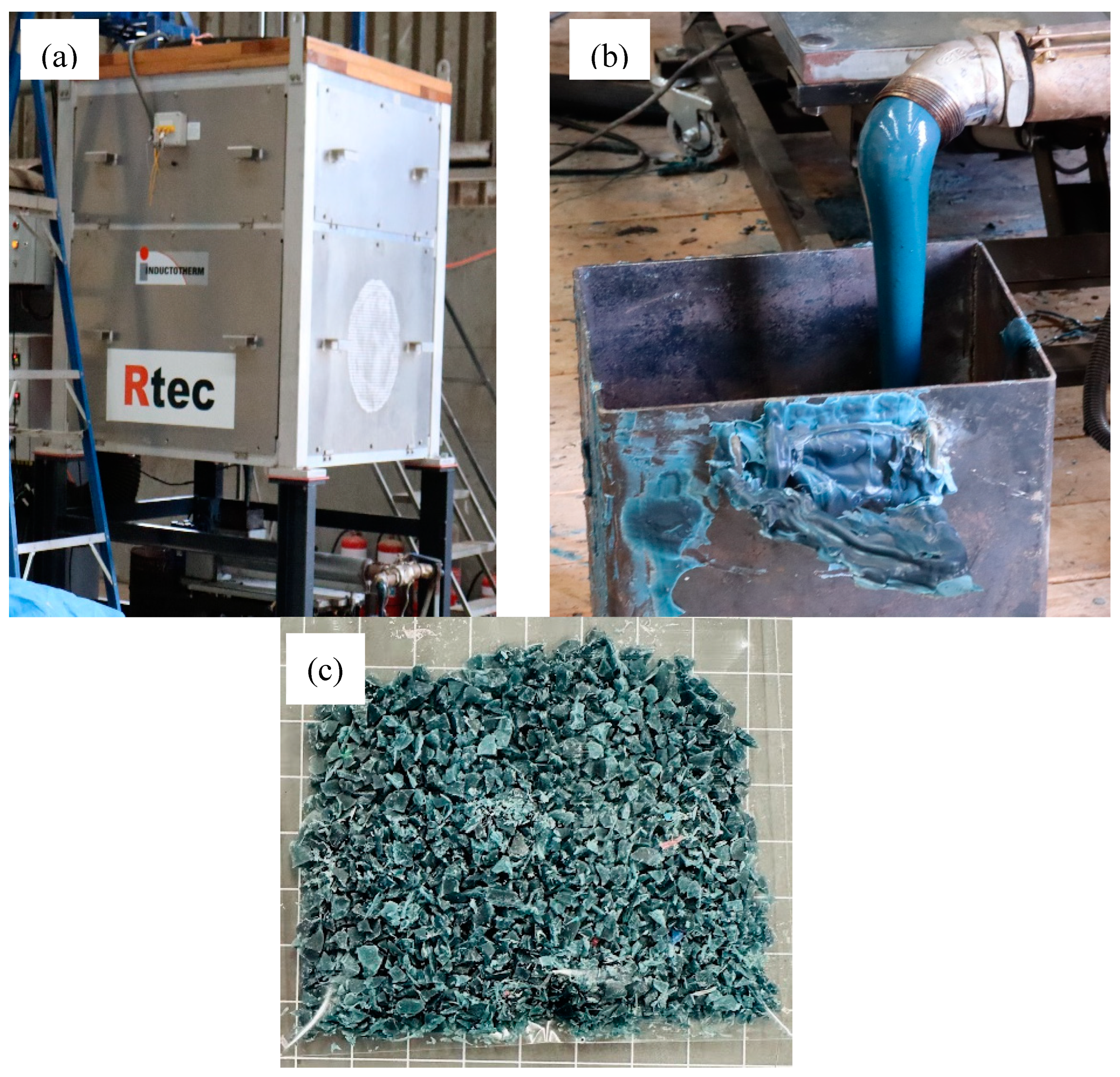

2.9. Production of 3D Printing Filament and Park Bench Using PBT

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Bale Twine and Processed Bale Twine

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3.4. Melt Flow Index

3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.7. Tensile Properties

3.8. Creep Test

3.9. Hardness Testing

3.10. Contact Angle

3.11. Morphology

3.12. 3D Printing Filament Production

3.13. Assembly of a Park Bench

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Briassoulis, D. Agricultural plastics as a potential threat to food security, health, and environment through soil pollution by microplastics: Problem definition. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164533. [CrossRef]

- Siwek, P.; Domagala-Swiatkiewicz, I.; Bucki, P.; Puchalski, M. Biodegradable agroplastics in 21st century horticulture. Polimery 2019, 64, 480–486. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, Z.; Wollmann, C.; Schaefer, M.; Buchmann, C.; David, J.; Tröger, J.; Muñoz, K.; Frör, O.; Schaumann, G.E. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 690–705. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wen, X.; Tang, W. Are biodegradable plastics a promising solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114469. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.S.; Hu, X.B.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, J. Effects of plastic mulch and crop rotation on soil physical properties in rain-fed vegetable production in the mid-Yunnan plateau, China. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 145, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Walsh, K.B. Microplastics in water: Occurrence, fate and removal. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2024, 264, 104360. [CrossRef]

- Coblentz, W.K.; Akins, M.S. Silage review: Recent advances and future technologies for baled silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4075–4092. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Du, Q. Uptake of Di-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate of Vegetables from Plastic Film Greenhouses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11585–11588. [CrossRef]

- Sintim, H.Y.; Bandopadhyay, S.; English, M.E.; Bary, A.I.; DeBruyn, J.M.; Schaeffer, S.M.; Miles, C.A.; Reganold, J.P.; Flury, M. Impacts of biodegradable plastic mulches on soil health. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 273, 36–49. [CrossRef]

- Bostan, N.; Ilyas, N.; Akhtar, N.; Mehmood, S.; Saman, R.U.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Shatid, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Pandiaraj, S. Toxicity assessment of microplastic (MPs); a threat to the ecosystem. Environ. Res. 2023, 234, 116523. [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, J.; Dvorak, R.; Kosior, E. Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2115–2126. [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D.; Hiskakis, M.; Babou, E. Technical specifications for mechanical recycling of agricultural plastic waste. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1516–1530. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Hernández, T.; Robledo-Ortíz, J.R.; González-López, M.E.; del Campo, A.S.M.; González-Núñez, R.; Rodrigue, D.; Pérez Fonseca, A.A. Mechanical recycling of <scp>PLA</scp> : Effect of weathering, extrusion cycles, and chain extender. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140. [CrossRef]

- Thiounn, T.; Smith, R.C. Advances and approaches for chemical recycling of plastic waste. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 1347–1364. [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, S.O.; Adeleke, A.A.; Ikubanni, P.P.; Nnodim, C.T.; Balogun, A.O.; Falode, O.A.; Adetona, S.O. Energy from biomass and plastics recycling: a review. Cogent Eng. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. [CrossRef]

- de Sá Teles, B.A.; Cunha, I.L.C.; da Silva Neto, M.L.; Wiebeck, H.; Valera, T.S.; de Souza, S.S.; de Oliveira Schmitt, A.F.; Oliveira, V.; Kulay, L. Effect of Virgin PP Substitution with Recycled Plastic Caps in the Manufacture of a Product for the Telephony Sector. Recycling 2023, 8, 51. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Shinners; B. M. Huenink; R. E. Muck; K. A. Albrecht Storage Characteristics of Large Round Alfalfa Bales: Dry Hay. Trans. ASABE 2009, 52, 409–418. [CrossRef]

- Kostic, S.; Kocovic, V.; Petrovic Savic, S.; Miljanic, D.; Miljojkovic, J.; Djordjevic, M.; Vukelic, D. The Influence of Friction and Twisting Angle on the Tensile Strength of Polypropylene Baling Twine. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3046. [CrossRef]

- McAfee, J.R.; Shinners, K.J.; Friede, J.C. Twine Tension in High-Density Large Square Bales. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2018, 34, 515–525. [CrossRef]

- Zrida, M.; Laurent, H.; Grolleau, V.; Rio, G.; Khlif, M.; Guines, D.; Masmoudi, N.; Bradai, C. High-speed tensile tests on a polypropylene material. Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 685–692. [CrossRef]

- Alsabri, A.; Tahir, F.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Environmental impacts of polypropylene (PP) production and prospects of its recycling in the GCC region. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 2245–2251. [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Gao, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, B. The boom era of emerging contaminants: A review of remediating agricultural soils by biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172899. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Y.; Rodrigue, D. Conversion of Polypropylene (PP) Foams into Auxetic Metamaterials. Macromol 2023, 3, 463–476. [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S.; Dinçer, H. Sustainability analysis of digital transformation and circular industrialization with quantum spherical fuzzy modeling and golden cuts. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 138, 110192. [CrossRef]

- Stoian, S.A.; Gabor, A.R.; Albu, A.-M.; Nicolae, C.A.; Raditoiu, V.; Panaitescu, D.M. Recycled polypropylene with improved thermal stability and melt processability. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 2469–2480. [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Putri, A.R.; Pratiwi, V.A.; Ilhami, V.I.N.; Kaniawati, I.; Kurniawan, T.; Farobie, O.; Bilad, M.R. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of pyrolysis of polypropylene microparticles and its chemical reaction mechanism completed with computational bibliometric literature review to support sustainable development goals (SDGs). J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2024, 19, 1090–1104.

- Gopanna, A.; Mandapati, R.N.; Thomas, S.P.; Rajan, K.; Chavali, M. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) of polypropylene (PP)/cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) blends for qualitative and quantitative analysis. Polym. Bull. 2019, 76, 4259–4274. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, U.; Ashraf, S.M. Characterization of Polymer Blends with FTIR Spectroscopy. In Characterization of Polymer Blends; Wiley, 2014; pp. 625–678. [CrossRef]

- Polypropylene; Karger-Kocsis, J., Ed.; Polymer Science and Technology Series; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1999; Vol. 2; ISBN 978-94-010-5899-5.

- Mylläri, V.; Ruoko, T.; Syrjälä, S. A comparison of rheology and FTIR in the study of polypropylene and polystyrene photodegradation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132. [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, C.M.C.; Martins, A.F.; Mano, E.B.; Beatty, C.L. Effect of recycled polypropylene on polypropylene/high-density polyethylene blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 80, 1305–1311. [CrossRef]

- Gall, M.; Steinbichler, G.; Lang, R.W. Learnings about design from recycling by using post-consumer polypropylene as a core layer in a co-injection molded sandwich structure product. Mater. Des. 2021, 202, 109576. [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Steinmetz, Z.; Gray, A.; Munno, K.; Lynch, J.; Hapich, H.; Primpke, S.; De Frond, H.; Rochman, C.; Herodotou, O. Microplastic Spectral Classification Needs an Open Source Community: Open Specy to the Rescue! Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 7543–7548. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-H.; Cho, M.-H.; Kang, B.-S.; Kim, J.-S. Pyrolysis of a fraction of waste polypropylene and polyethylene for the recovery of BTX aromatics using a fluidized bed reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 277–284. [CrossRef]

- Mihelčič, M.; Oseli, A.; Huskić, M.; Slemenik Perše, L. Influence of Stabilization Additive on Rheological, Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polypropylene. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14, 5438. [CrossRef]

- Kashi, S.; De Souza, M.; Creighton, C.; Al-Assafi, S.; Varley, R. Degradation of Polyalkylene Glycol: Application of FTIR, HPLC, and TGA in Investigating PAG Oil Thermal Stability and Antioxidant Reaction Kinetics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 19638–19648. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, S.K.; Mostafazadeh-Marznaki, M.; Chaharmahali, M.; Tajvidi, M. Effect of Thermomechanical Degradation of Polypropylene on Mechanical Properties of Wood-Polypropylene Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2009, 43, 2543–2554. [CrossRef]

- Wijerathne, D.; Gong, Y.; Afroj, S.; Karim, N.; Abeykoon, C. Mechanical and thermal properties of graphene nanoplatelets-reinforced recycled polycarbonate composites. Int. J. Light. Mater. Manuf. 2023, 6, 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Freudenthaler, P.J.; Fischer, J.; Liu, Y.; Lang, R.W. Polypropylene Post-Consumer Recyclate Compounds for Thermoforming Packaging Applications. Polymers (Basel). 2023, 15, 345. [CrossRef]

- Baltes, L.; Costiuc, L.; Patachia, S.; Tierean, M. Differential scanning calorimetry—a powerful tool for the determination of morphological features of the recycled polypropylene. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 2399–2408. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenstein, G.W.; Riedel, G.; Trawiel, P. Thermal analysis of plastics : theory and practice; Hanser ; Hanser Gardner Publications [distributor]: Munich, Cincinnati SE - xxix, 368 pages : illustrations (some color) ; 25 cm, 2004; ISBN 156990362X; 9781569903629; 3446226737; 9783446226739.

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Tzounis, L.; Maniadi, A.; Velidakis, E.; Mountakis, N.; Papageorgiou, D.; Liebscher, M.; Mechtcherine, V. Sustainable Additive Manufacturing: Mechanical Response of Polypropylene over Multiple Recycling Processes. Sustainability 2020, 13, 159. [CrossRef]

- Tratzi, P.; Giuliani, C.; Torre, M.; Tomassetti, L.; Petrucci, R.; Iannoni, A.; Torre, L.; Genova, S.; Paolini, V.; Petracchini, F.; et al. Effect of Hard Plastic Waste on the Quality of Recycled Polypropylene Blends. Recycling 2021, 6, 58. [CrossRef]

- Ferg, E.E.; Bolo, L.L. A correlation between the variable melt flow index and the molecular mass distribution of virgin and recycled polypropylene used in the manufacturing of battery cases. Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 1452–1459. [CrossRef]

- Luna, C.B.B.; da Silva, W.A.; Araújo, E.M.; da Silva, L.J.M.D.; de Melo, J.B. da C.A.; Wellen, R.M.R. From Waste to Potential Reuse: Mixtures of Polypropylene/Recycled Copolymer Polypropylene from Industrial Containers: Seeking Sustainable Materials. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6509. [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, A.; Kucukpinar, E.; Stoll, H.; Sängerlaub, S. Comparison of Properties with Relevance for the Automotive Sector in Mechanically Recycled and Virgin Polypropylene. Recycling 2021, 6, 76. [CrossRef]

- Handayani, S.U.; Fahrudin, M.; Mangestiyono, W.; Hadi Muhamad, A.F. Mechanical Properties of Commercial Recycled Polypropylene from Plastic Waste. J. Vocat. Stud. Appl. Res. 2021, 3, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Satya, S.K.; Sreekanth, P.S.R. An experimental study on recycled polypropylene and high-density polyethylene and evaluation of their mechanical properties. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 920–924. [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad, K.; Ravichandran, K.; Jayaseelan, V.; Muthuramalingam, T. Acoustic and mechanical characterisation of polypropylene composites reinforced by natural fibres for automotive applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14029–14035. [CrossRef]

- Zdiri, K.; Elamri, A.; Hamdaoui, M.; Harzallah, O.; Khenoussi, N.; Brendlé, J. Reinforcement of recycled PP polymers by nanoparticles incorporation. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11, 296–311. [CrossRef]

- Bourmaud, A.; Le Duigou, A.; Baley, C. What is the technical and environmental interest in reusing a recycled polypropylene–hemp fibre composite? Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2011, 96, 1732–1739. [CrossRef]

- Berdjane, K.; Berdjane, Z.; Rueda, D.R.; Bénachour, D.; Baltá-Calleja, F.J. Microhardness of ternary blends of polyolefins with recycled polymer components. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 89, 2046–2050. [CrossRef]

- Nukala, S.G.; Kong, I.; Kakarla, A.B.; Tshai, K.Y.; Kong, W. Preparation and Characterisation of Wood Polymer Composites Using Sustainable Raw Materials. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14, 3183. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, A.J.; Marcovich, N.E.; Aranguren, M.I. Analysis of the creep behavior of polypropylene-woodflour composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2004, 44, 1594–1603. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Lei, Y.; Yao, F. Creep behavior of bagasse fiber reinforced polymer composites. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3280–3286. [CrossRef]

- Homkhiew, C.; Ratanawilai, T.; Thongruang, W. Time–temperature and stress dependent behaviors of composites made from recycled polypropylene and rubberwood flour. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 66, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Houshyar, S.; Shanks, R.A.; Hodzic, A. Tensile creep behaviour of polypropylene fibre reinforced polypropylene composites. Polym. Test. 2005, 24, 257–264. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-C.; Wu, T.-L.; Hung, K.-C.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wu, J.-H. Mechanical properties and extended creep behavior of bamboo fiber reinforced recycled poly(lactic acid) composites using the time–temperature superposition principle. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 558–563. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, K.; Chen, L. Short term creep properties of WPC at different temperatures—An experimental and numerical investigation at different stress levels. Polym. Compos. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-C.; Chien, Y.-C.; Wu, T.-L.; Hung, K.-C.; Wu, J.-H. Effects of Heat-Treated Wood Particles on the Physico-Mechanical Properties and Extended Creep Behavior of Wood/Recycled-HDPE Composites Using the Time–Temperature Superposition Principle. Materials (Basel). 2017, 10, 365. [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-C.; Wu, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wu, J.-H. Assessing the effect of wood acetylation on mechanical properties and extended creep behavior of wood/recycled-polypropylene composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 108, 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Landel, R.F.; Nielsen, L.E. Mechanical properties of polymers and composites; CRC press, 1993; ISBN 1482277433.

- Ferry, J.D. Viscoelastic properties of polymers; John Wiley & Sons, 1980; ISBN 0471048941.

- Choi, H.-J.; Kim, M.S.; Ahn, D.; Yeo, S.Y.; Lee, S. Electrical percolation threshold of carbon black in a polymer matrix and its application to antistatic fibre. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6338. [CrossRef]

- Monasse, B.; Haudin, J.M. Growth transition and morphology change in polypropylene. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1985, 263, 822–831. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Hay, J.N. The measurement of the crystallinity of polymers by DSC. Polymer (Guildf). 2002, 43, 3873–3878. [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-C.; Wu, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wu, J.-H. Assessing the effect of wood acetylation on mechanical properties and extended creep behavior of wood/recycled-polypropylene composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 108, 139–145. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Tm (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔHm (J/g) | Xc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PP | 152.00 | 113.49 | 54.24 | 26.6 |

| BT | 164.04 | 118.15 | 149.57 | 72.2 |

| Model | Parameter | Processed ET |

|---|---|---|

| Burger's Model | Em | 1.0 GPa |

| Ek | 2.322 GPa | |

| ηk | 70.159 GPa | |

| ηm | 3.55 × 103 GPa | |

| τ | 15.9 | |

| R2 | 0.75 | |

| Findley power-law model | S0 | 0.32 /GPa |

| a | 0.25 | |

| b | 1.0 | |

| R2 | 2.322 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).