1. Introduction

An additional name for candle bush is

Senna alata (L.) Roxb. (

SA), which belongs to the Fabaceae family. This ornamental plant originates in its natural habitat, the Amazon Rainforest. It is widely accessible across the continents of Asia and Africa. Cultivated for medicinal purposes in the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, this shrub is extensively distributed [

1]. As a result of its ethnomedical applications in the treatment of numerous health conditions, it has acquired considerable significance. Predominantly found in active phytochemicals [

1], compared to the roots, flowers, and stem materials, the leaves are utilized more frequently in traditional medicine. SA leaves, both fresh and dried, have been utilized as remedies for skin maladies, constipation, stomach pain, and ringworm in a number of countries [

2].

SA leaf extract has been associated with a range of pharmacological properties [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], which include analgesic, laxative, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anthelmintic, and antimicrobial effects.

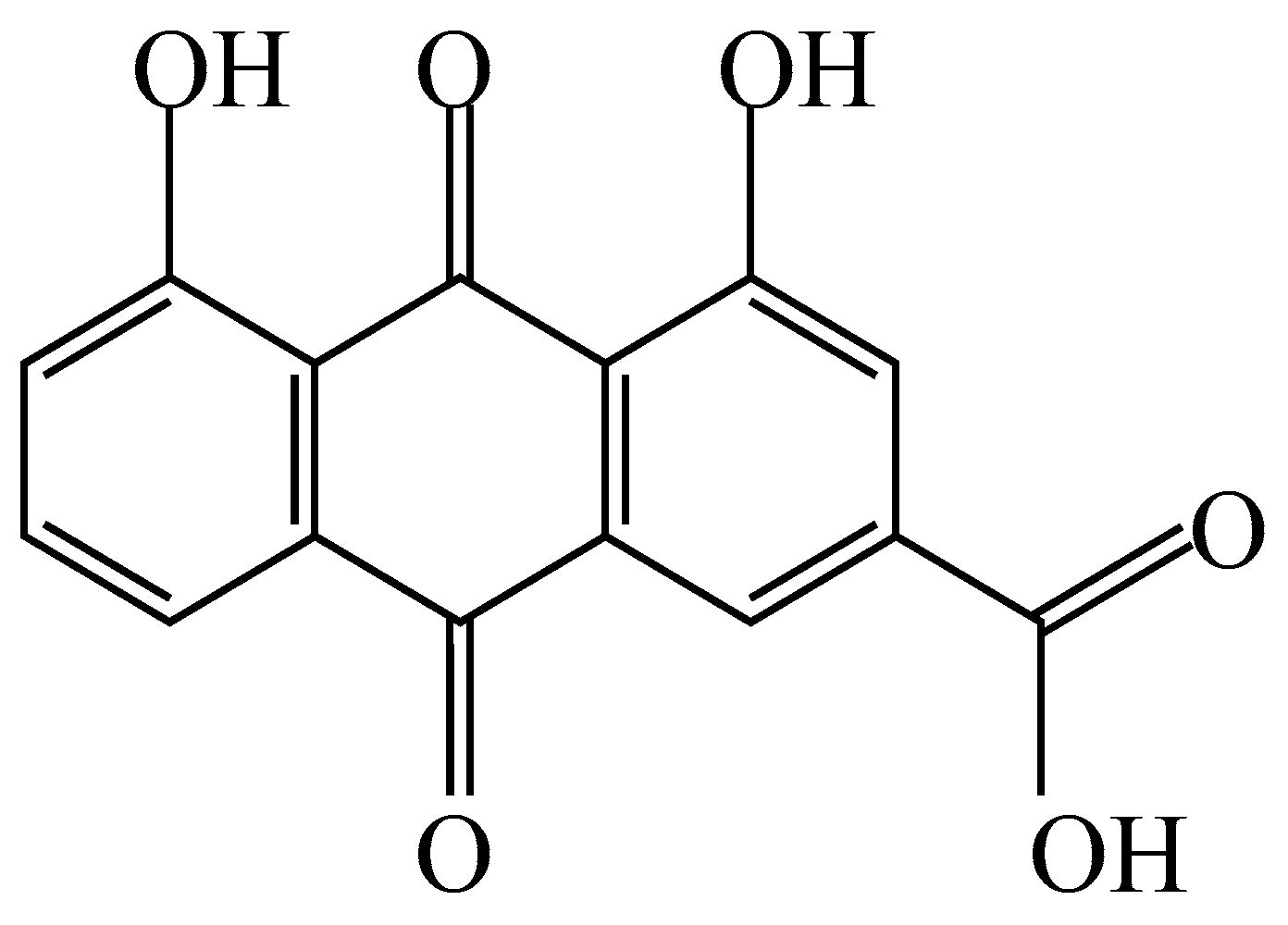

SA leaf extract is rich in carbohydrates, proteins, anthraquinones, flavonoids, terpenoids, tannins, phlobatannins, saponins, cardiac glycosides, and flavonoids [

8]. The authors, Ahmed S. and Shohael A.M., identified antifungal anthraquinones, namely aloe-emodin, chrysophanol, emodin, and rhein, in the SA leaves [

9]. Khare C.P. noted in Indian Medicinal Plants that rhein was responsible for the antibacterial activity of SA leaves [

10]. Limmatvapirat, C., et al. discovered that the high rhein content of SA leaf extract was responsible for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties [

11]. This demonstrated that the

SA leaf extract possessed sufficient biological properties to be utilized in the formulation of pharmaceuticals.

Shellac, which originates from the resinous secretions of lac insects (

Laccifer lacca), is a naturally occurring polymer [

12]. Single esters of aleuritic acid and terpenic acids (specifically jalaric acid or laccijalaric acid) comprise its composition. Shellac, which has a low crystallinity and a melting point between 50 °C and 75 °C, is a semicrystalline polymer [

13]. Shellac is applicable in numerous industries, including food and pharmaceutical technologies, due to its numerous advantageous properties. The aforementioned characteristics consist of favorable film formation, water resistance, flexibility, non-toxicity, biodegradability, high luster, acid resistance, and low gas and water vapor permeability [

14]. Additionally, delivery systems composed of shellac and varying in size from nanometers to micrometers have been developed [

15]. Examples include nanofibers, microparticles, hydrogels, and others.

Sticklac is a resinous substance that is secreted by the lac insect's female, a species that inhabits tree branches. The sticklac was subjected to a series of procedures in order to obtain seed-lac: crushing, sieving, washing with an alkaline aqueous solution and water, and air-drying to eliminate insect remains, branches, and other impurities [

16]. When seedlac is purified, the valuable substance shellac is produced. There are two distinct methods for producing shellac: melting, filtration, and forming into thin sheets; or dissolving the seedlac in an organic solvent, filtration to remove sediment, evaporation, and establishing into a thin film [

16]. The three distinct varieties of commercial shellac correspond to the methods of production: bleached, machine-made, and hand-made. By dissolving seedlac in an alkaline aqueous solution, treating it with sodium hypochlorite, and precipitating it with sulfuric acid, bleached shellac is produced. By removing wax from the precipitate via filtration, dewaxed or bleached shellac is produced [

17]. Although several studies have been published on the application of bleached shellac for enteric coating of drugs [

18], edible surface coating of fruits and vegetables [

19], microparticle formation of antibacterial oils [

20], and gel formation for periodontitis treatment [

21], there is currently no research examining the application of bleached shellac in the production of electrospun nanofibers.

Drug delivery systems based on nanotechnology employ nanoscale materials to regulate and target drug release with extreme precision. Nanotechnology enables the site-specific and target-oriented medication delivery that is beneficial for chronic diseases. The application of natural products integrated into nanomaterials in clinical settings remains a challenging endeavor [

22]. A range of biopolymeric materials are employed in drug delivery and natural product-based nanotechnology, such as shellac [

23], chitosan [

24], xanthan gum [

24], and cellulose [

25]. At present, a multitude of scientific investigations are focused on the pharmacological potential of bioactive compounds or phytochemical constituents found in various plant species. The objective is to create active ingredients that exhibit superior safety and reduced adverse effects compared to synthetic compounds currently in use [

26].

Due to their numerous advantages, nanofibers, which are defined as fibers with a diameter of less than 1000 nm, are extensively utilized in drug delivery, cosmetics, and wound dressing. The advantages encompass favorable stability, accurate administration of active ingredients to the intended site, minimal toxicity, enhanced capacity for loading drugs, exceptional mechanical properties, encapsulation of various categories of active compounds, and suitability for pharmaceuticals that are sensitive to temperature [

27]. Electrospinning (including emulsion electrospinning, coaxial electrospinning, and multi-jet electrospinning) and non-electrospinning processes (including interfacial polymerization, phase separation, and self-assembly) are utilized to generate nanofibers [

28]. Electrospinning is the predominant and most efficient method utilized in the fabrication of nanofibers. Single-fluid electrospinning involves the feeding of a polymer solution or polymer melt containing active components through a high-voltage electrospinning machine (10-50 kV). This process yields delicate fibers [

29]. Applied voltage, polymer type, and polymer concentration frequently have a significant impact on the properties of nanofibers [

30]. The electrospinning process utilizes electrostatic force to deform electrospinning fluid into nanoscale fibers that resemble the extracellular matrix of native tissue. As a result, these filaments have the capacity to facilitate regular cellular processes, such as cell proliferation and attachment. Electrospinning yields nanofibers that demonstrate remarkable characteristics, such as a substantial specific surface area, elevated porosity, favorable biocompatibility, and biodegradability. Consequently, electrospun nanofibers have been extensively implemented across various sectors of the pharmaceutical industry, including but not limited to wound dressings, medical implants, drug delivery systems, and scaffolds for tissue engineering [

31].

The physical and chemical properties of electrospun nanofibers are primarily dictated by the electrospinning process, with a strong reliance on the morphology of these nanofibers. The electrospinning process is notably influenced by three categories of factors: process parameters, solution parameters, and ambient conditions [

32]. Modifying these parameters has the potential to bring about alterations in the morphology and structure of the nanofibers. Conducting an analysis of the optimal electrospinning conditions becomes imperative for achieving the desired array of fine-diameter, beadless nanofibers. A fractional factorial design (

FFD) stands out as a crucial statistical advancement for investigating the impacts of multiple controllable factors on a specific response of interest. The careful reduction in the size of an experiment is not only a well-established design feature but also serves to prevent the loss of valuable data, given that not all conceivable combinations of the levels of the factors of interest are tested [

33]. This design functions as a preliminary stage in the assessment procedure, wherein critical factors are identified prior to advancing to a more exhaustive evaluation. Reducing the number of trials does not encompass all potential interactions that may occur among independent factors within the experimental space. After conducting preliminary tests, crucial variables are identified for additional analysis through the utilization of either a response surface design or a full factorial design, which includes a central tendency and replicated experiments. In contrast to three-level factorial designs, response surface designs present a more streamlined methodology by generating significant insights through a reduced number of trials. In order to develop a more accurate representation of the response variable, these designs examine curvature and interactions in the experimental space [

34,

35,

36]. Hence, employing an alternative optimization design becomes crucial for achieving optimal conditions. One frequently used response surface design is the Box-Behnken (

BB) design, which aims to optimize processes by examining the interplay between various factors and their impact on a response variable. The BB design, known for its rotatability, requires three levels per factor and incorporates a central point for quadratic effect estimation. This approach is particularly well-suited for experiments involving more than two factors, providing a streamlined method to determine optimal conditions with minimal iteration [

37]. Once the response surface model is established, optimization techniques can be applied to identify optimal conditions for maximizing or minimizing the response variable.

Due to their unique characteristics, electrospun nanofiber dressings promote more effective wound healing than conventional dressings. Nanofibers can optimally absorb exudates, provide a moist environment that promotes cell respiration and proliferation, reduce bacterial infection and inflammation, offer additional high permeability, and protect damaged tissues from dehydration [

38]. Electrospinning can incorporate numerous molecules into nanofibers, such as drugs, growth factors, bioactive nanoparticles, and herbal extracts. Because of their biodegradability, high compatibility with blood and tissues, and antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, electro-spun biopolymer dressings containing herbal extract or natural compounds could promote wound healing and cell growth [

39,

40,

41]. Sprague-Dawley rats subjected to treatment with electrospun gelatin membranes containing

Centella asiatica extract as transdermal wound dressings demonstrated superior dermal wound-healing activity in comparison to rats treated with gauze (utilized as a control), gelatin membranes without

C. asiatica extract, and commercial wound dressings. This enhanced activity can be attributed to the antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties of the electrospun membranes [

42]. The wound dressing, composed of chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibers containing green tea (

Camellia sinensis) extract and prepared through the electrospinning method, exhibited superior healing effects on rat wounds compared to other prepared wound dressings. This notable effectiveness can be attributed to its antibacterial activities against

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus, as well as its high swelling capacity. This characteristic ensures the retention of moisture on the wound surface throughout the healing process and prevents nanofibers from adhering to the wound surface, contributing to an optimal healing environment [

43]. Electrospun gelatin nanofibers containing an ethanol extract of

Curcuma comosa Roxb. rhizomes displayed antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase, and antibacterial properties. To achieve optimal conditions for electrospun nanofibers with enhanced freeze-thaw stability, the gelatin concentration was 30% w/v in a co-solvent system of acetic acid and water (9:1 v/v) at a feed rate of 3 mL/h and an applied voltage of 15 kV. The lowest loading percentage of 5% w/v ethanol extract in nanofibers showed remarkable DPPH radical scavenging, anti-tyrosinase, and antibacterial properties against

S. aureus and

Staphylococcus epidermidis [

44]. Although numerous investigations [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49] have detected noteworthy antimicrobial capabilities in

SA leaf extract, no research has yet been conducted on its incorporation into electrospun nanofibers. Based on the antimicrobial properties of

SA leaf extract and the unique characteristics of electrospun shellac fibers, it is possible that electrospun shellac fibers infused with this extract could promote faster wound healing.

The present study employed electrospinning to generate shellac fibers that incorporated SA leaf extract. The screening procedure was employed to determine the most effective electrospinning parameters that would yield nanofibers with the intended morphology, utilizing a fractional factorial experimental design. In order to determine the optimal values for each dependent parameter, the BBD was applied. Furthermore, an investigation was conducted on the entrapment efficiency and release kinetics of rhein from electrospun shellac fibers laden with SA leaf extract. Additionally, the antimicrobial properties of these fibers were assessed, given that inhibiting microbial growth could accelerate the healing of wounds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

SA leaves, bleached shellac, and ethanol absolute (≥ 99.8% v/v) were procured from Charoensuk Osot, an herbal shop in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand; Excelacs Co., Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand; and VWR International (Fontenay-sous-Bois, Val-de-Marne, France), respectively. Acetonitrile HPLC grade (≥ 99.93% v/v), orthophosphoric acid (85% w/w), and standard rhein (≥ 95% w/w) were procured from Fisher Scientific Korea Ltd. (Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Korea), Ajax Finechem (Botany, Auckland, New Zealand), and MilliporeSigma Supelco (Frankfurter Strasse, Darmstadt, Germany). Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) and Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) were purchased, respectively, from Becton, Dickinson and Company (Sparks, Maryland, USA) and HiMedia Laboratories Private Limited (Mumbai, Maharashtra, India).

2.2. Preparation of SA leaf extract

In accordance with our prior research [

11],

SA leaf extraction was conducted under optimal extraction conditions in order to yield an extract with a high rhein content. A precise volume of dehydrated pulverized

SA leaves was combined with 95% v/v ethanol in a 25:1 (mL/g) solid-to-solvent ratio. The solution was subsequently extracted utilizing an ultrasonicator (Model 230D, Crest Ultrasonics Corporation, Trenton, New Jersey, USA) set to a frequency of 42-45 kHz (level 9) at a temperature of 60 °C. Following an extraction period of 18 min, the obtained solutions underwent filtration through a Whatman filter paper No. 1. Subsequently, the filtrate was evaporated using a rotary evaporator (R-100, Buchi, Tokyo, Japan) set at 40 °C and 35 mbar of pressure. The concentrated mass was thoroughly dried using a freeze dryer (Model 6112974, Labconco Corporation, Kansas City, Missouri, USA) and subsequently stored in a dark environment at -20 °C until further analysis."

2.3. Design of experiments

2.3.1. Fractional factorial design (FFD)

A

FFD was employed to investigate the main effects and potential interactions among various factors influencing multiple response variables in shellac fibers incorporated with SA leaf extract. The parameters and experimental ranges are outlined in

Table 1, established through preliminary experiments and prior research with slight modifications [

23,

50]. The Design Expert software, version 8.0.6 (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), was utilized to create the design matrix and perform data analysis. The response variables measured were the diameter of fibers and the bead-to-fiber ratio.

2.3.2. Box-Behnken design (BBD)

The FFD results aid in the identification of critical variables that have a substantial impact on both the diameter of the fiber and the ratio of beads to fibers. In order to optimize the electrospinning procedure for shellac nanofibers laden with SA leaf extract, a

BBD was executed. Multiple response variables, including fiber diameter, bead-to-fiber ratio, and entrapment efficacy, were accounted for in this design. The precise ranges and levels of each parameter are specified in

Table 2. A total of 29 experimental trials were conducted, with the inclusion of five center points in order to guarantee thorough coverage of the data.

2.4. Preparation and evaluation of shellac-SA leaf extract solutions

In order to formulate the solution, an exact volume of SA leaf extract was dissolved in ethanol with a concentration of 95% v/v. To guarantee total solubility, an ultrasonicator (Model 230D, Crest Ultrasonics Corporation, Trenton, New Jersey, USA) was employed. Following that, different concentrations of bleached shellac were introduced into each of these solutions and agitated for one night at ambient temperature using a magnetic stirrer (ST10, Finepcr, Seoul, Korea). After agitating, the concentrations of each solution were modified by adding 95% v/v ethanol in order to achieve the intended results. Following that, an examination was conducted on the viscosity, conductivity, and surface tension of the shellac-extract solution using the following instruments: a viscometer (RM 100 CP 2000 Plus, LAMY Rheology, Champagne-au-Mont-d'Or, France), an electrical conductivity meter (Model EC400, Extech Instruments Corporation, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA), and a drop shape analyzer (First Ten Angstroms, Portsmouth, Virginia, USA).

2.5. Fabrication of electrospun shellac fibers loaded with SA leaf extract

Each solution was transferred to a 10-mL syringe featuring a needle at the nozzle and connected to a high-voltage power supply during the electrospinning procedure. The fibers that were obtained were deposited on the aluminum foil that was affixed to the rotating cylinder. For all samples, the distance between the needle point and the collector remained constant at 20 cm. The electrospinning procedure was carried out in a controlled environmental setting, characterized by a relative humidity (RH) of 40% to 60% and a temperature range of 23-25 °C.

2.6. Entrapment efficiency of SA leaf extract into electrospun fibers

The quantity of extract encapsulated within nanofibers was assessed through quantitative dilution of rhein content, which was employed as an electrospun fiber marker compound. The determination of the entrapment efficiency of

SA leaf extract was performed by employing the calibration curve of standard rhein. Through serial dilution of standard rhein solutions ranging from 2 g/mL to 30 g/mL, the calibration curve was generated. After dissolving each fiber sample (0.2 g) in ethanol at a concentration of 95% v/v, the volume was adjusted to 10.0 mL. The rhein concentration was subsequently determined by employing high-performance liquid chromatography with a diode array detector (HPLC-DAD) on an Agilent 1100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). The chromatographic separation was performed by employing an isocratic elution system at a temperature of 40 °C and utilizing a Luna Omega Polar C18 column (100 Å, 5 μm

, 4.6 mm x 250 mm) manufactured by Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, California, USA. A 55:45 (v/v) ratio was maintained for the mobile phase, which comprised acetonitrile and 0.1% v/v orthophosphoric acid in an aqueous solution; elution was conducted at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The injection volume, total run duration, and detection wavelength were all configured with the following specific values: 10 µL, 40 min, and 254 nm, respectively. The analysis described above was conducted using the validated method developed by Limmatvapirat C. et al. [

11]. The extract's entrapment efficacy (in %) was determined by employing the subsequent equation [

51].

2.7. In vitro release study

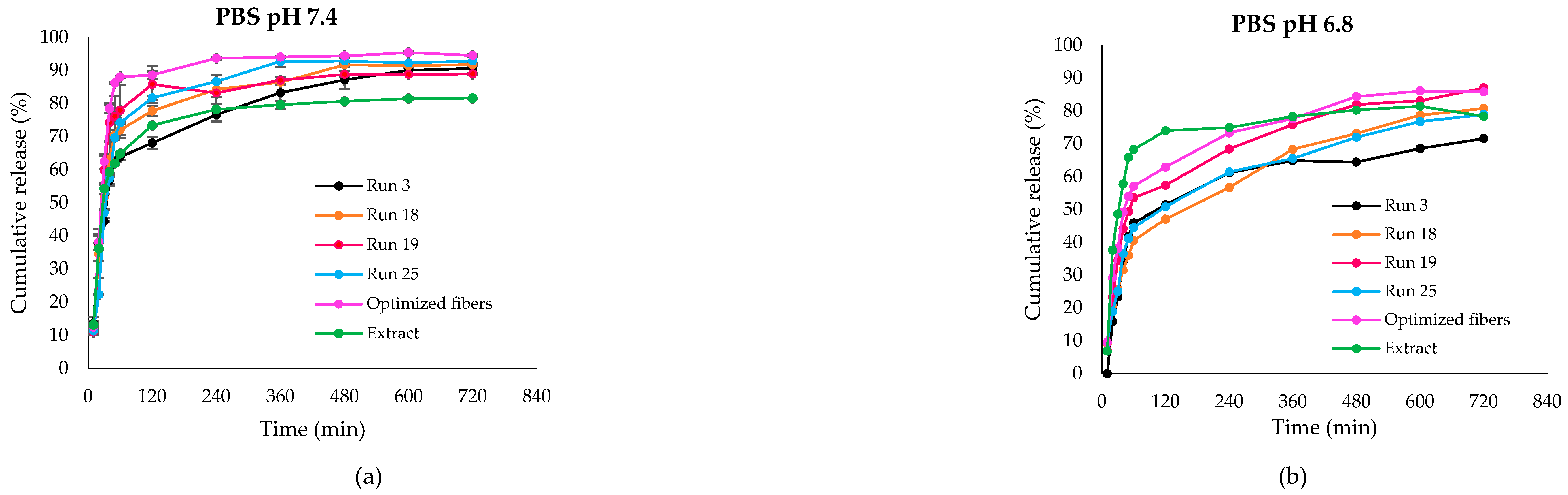

The

in vitro release study of rhein from

SA leaf extract encapsulated in shellac electrospun fibers was investigated using two types of releasing media: phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 and pH 6.8, employing the direct immersion method [

52]. To enhance the solubility of the fibers, 1.5% Tween 80 was introduced into each medium. Six fiber samples, including Run 3 (446.89 nm) and Run 18 (426.59 nm) representing large fiber diameters, and Run 19 (277.07 nm) and Run 25 (226.21 nm) representing small fiber diameters, along with the optimized fiber and extract, were utilized to assess and compare the release characteristics of rhein from each sample. Each sample was immersed in 10 mL of dissolution media and shaken at 100 rpm in a temperature-controlled incubator at 37 °C for 12 hr. One mL of each sample solution was withdrawn at regular time intervals (10 min, 20 min, 30 min, 40 min, 50 min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 6h, 8h, 10h, and 12h), and an equivalent volume of fresh medium was added to ensure a constant volume. The concentration of rhein released from the collected sample solutions was determined using HPLC-DAD.

2.8. Release kinetics

The dissolution profiles of each fiber underwent fitting with different kinetic models, encompassing the zero-order, first-order, Higuchi model, and Korsmeyer-Peppas model, using Excel Add-in DD Solver version 1. The selection of the optimal model relied on criteria such as the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the highest Model Selection Criterion (MSC), and the highest adjusted coefficient of determination (R2 adj). These criteria collectively guided the identification of the most appropriate model for characterizing the dissolution behavior of the fibers.

2.9. Characterization of electrospun shellac fibers loaded with SA leaf extract

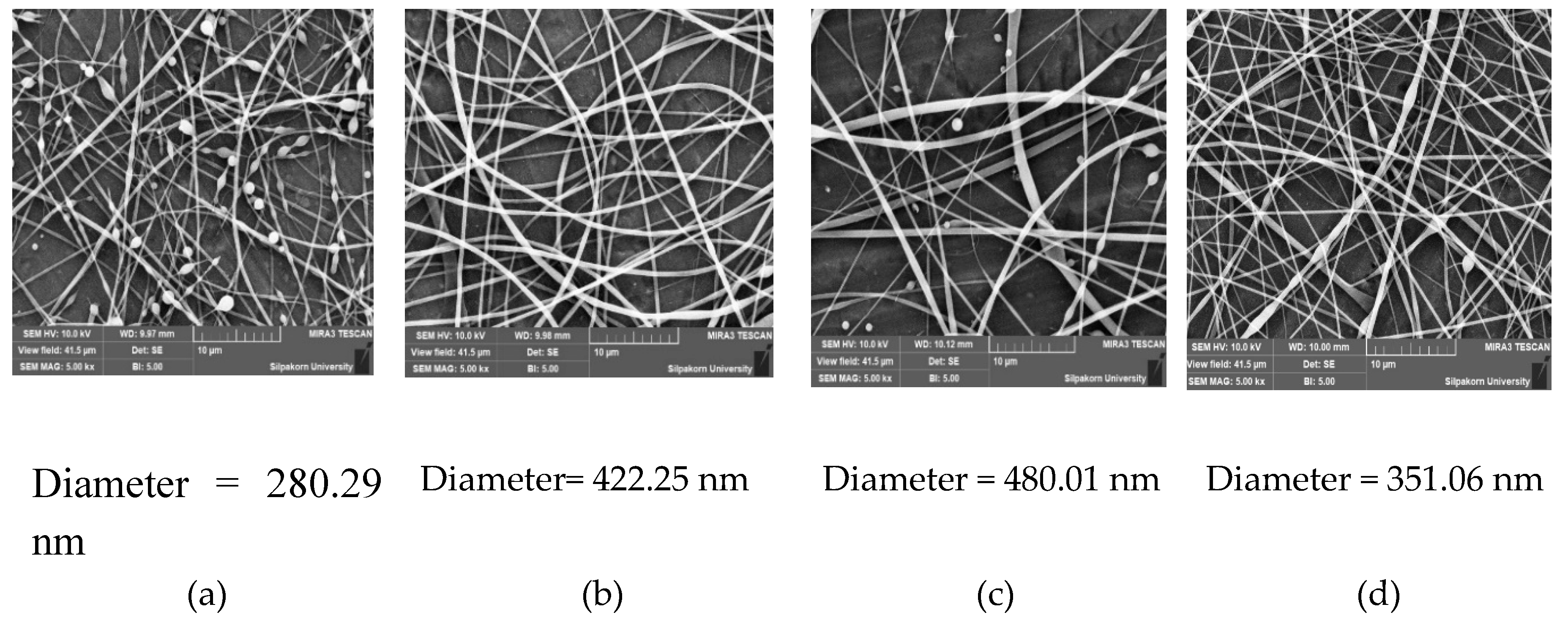

2.9.1. Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The morphology of electrospun shellac fibers, containing SA leaf extract, was investigated using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (MIRA 3, Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). Fiber diameters and the bead-to-fiber ratio were analyzed based on SEM images, employing JMicroVision V.1.2.7 software from University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland.

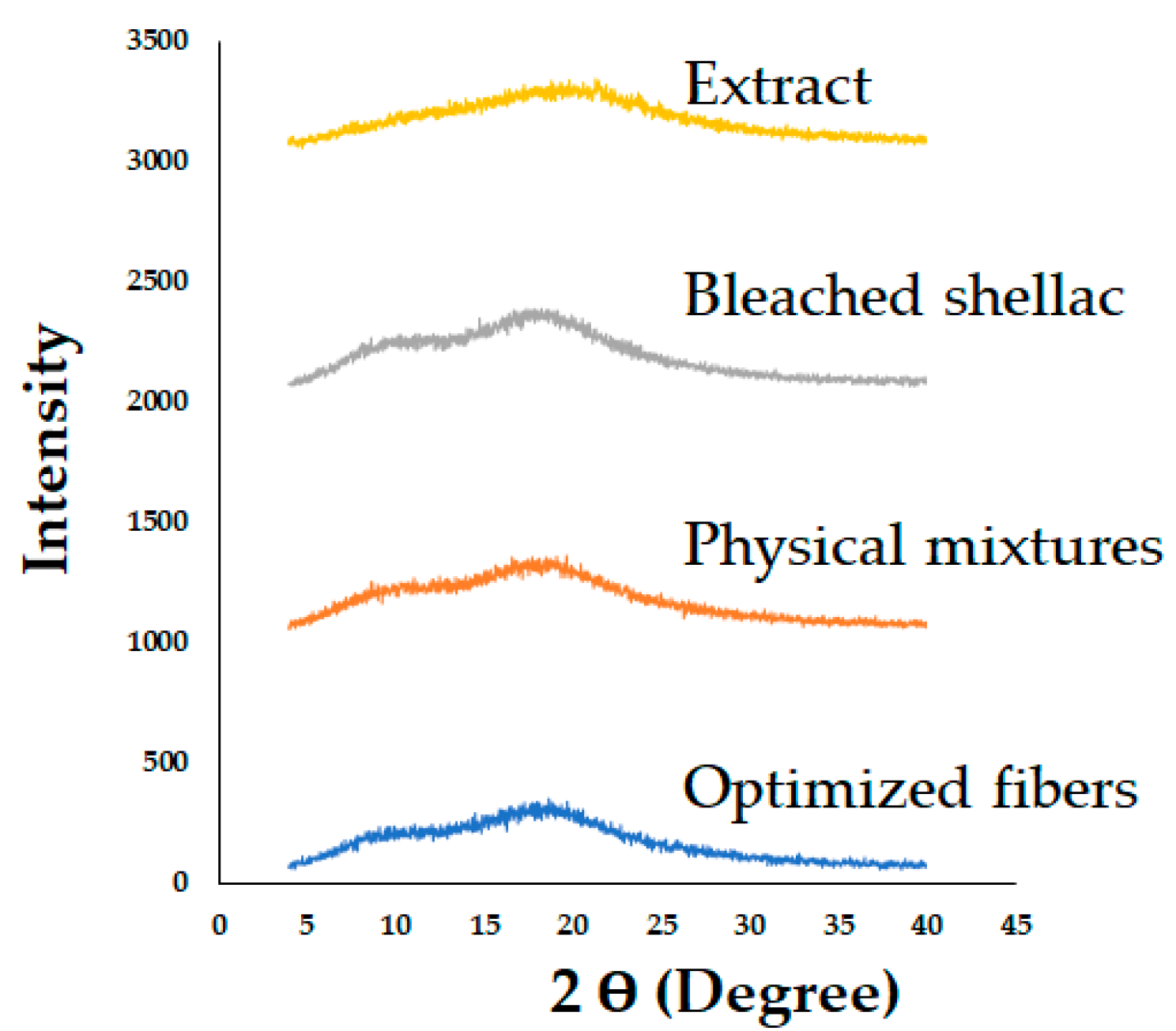

2.9.2. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

The investigation of the crystallinity of SA leaf extract, bleached shellac, their physical mixtures, and fibers was conducted utilizing a powder X-ray diffractometer (PXRD) MiniFlex II, manufactured by Rigaku Corporation in Tokyo, Japan. At 40 mV and 30 mA, the analysis was conducted utilizing Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). To observe whether each sample was crystalline or amorphous, they were scanned at a rate of 4°/min in the 2θ range of 5° to 40°.

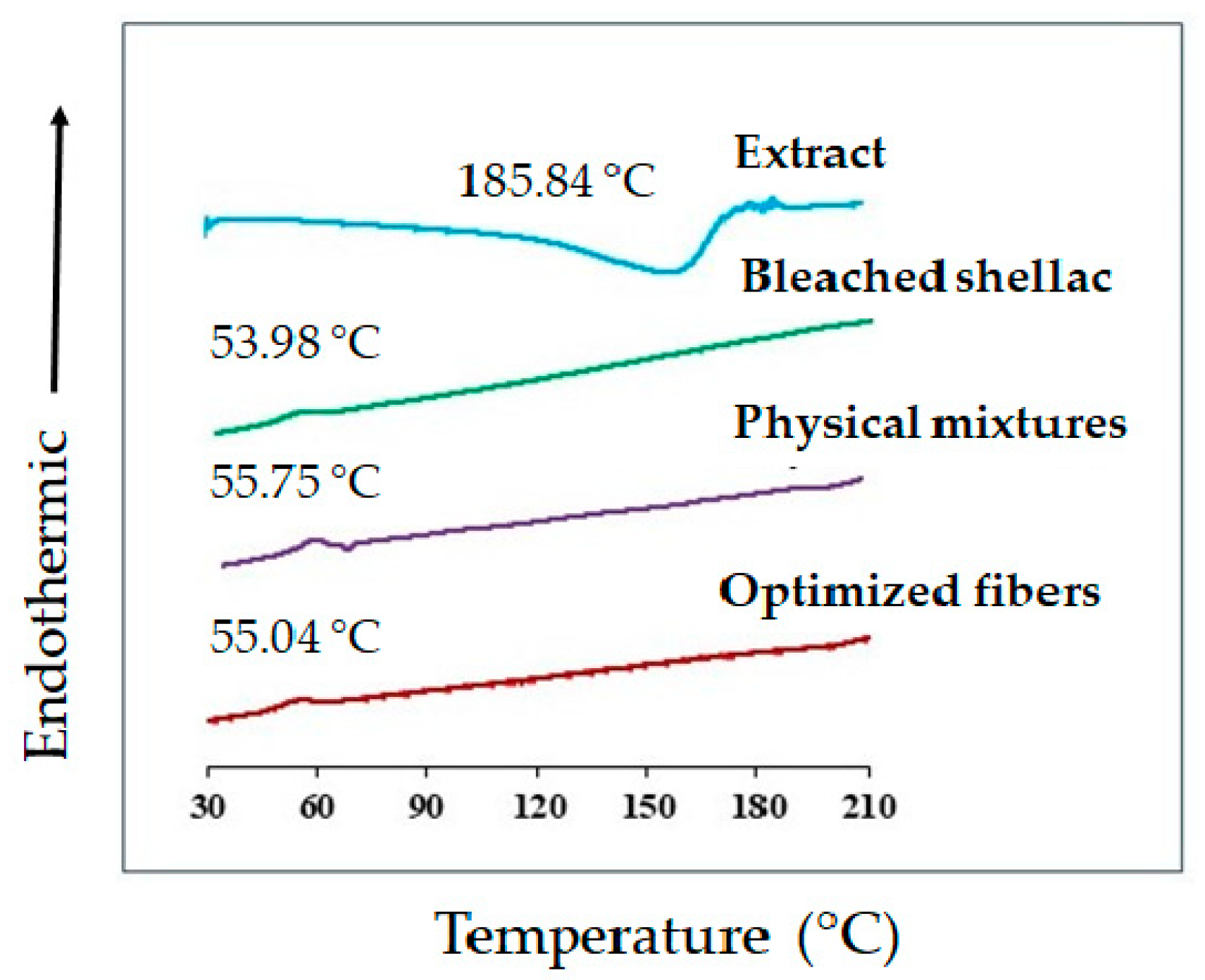

2.9.3. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Utilizing a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC 8000, Perkin Elmer, Rodgau, Germany), the thermal properties of electrospun fibers were assessed. Each sample in the aluminum container weighed between 2 and 5 mg. The samples were subsequently heated in the range of 25 °C to 210 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. An examination was conducted while nitrogen gas was flowing at a rate of 20 mL/min.

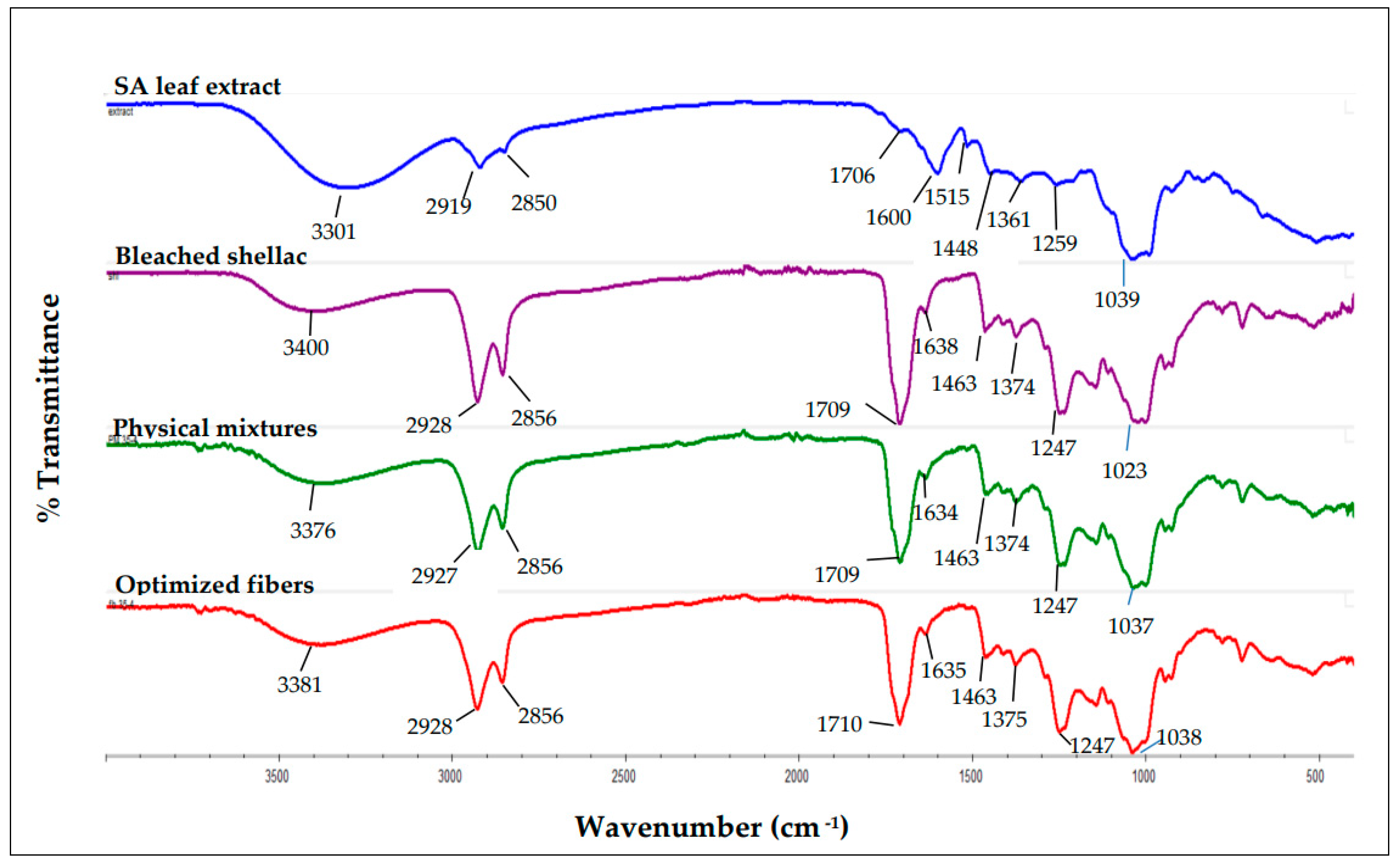

2.9.4. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

Using FTIR (Nicolet Avatar 360, Ramsey, Minnesota, USA), the chemical compositions and functional properties of SA leaf extract, bleached shellac, their physical mixtures, and fibers were analyzed. Each sample was incorporated into KBr powder, which was subsequently compacted under hydraulic pressure into a pellet before being inserted into the sample holder. The spectrum was acquired at a resolution of 4 cm-1 over the range of wavenumbers from 4000 to 400 cm-1.

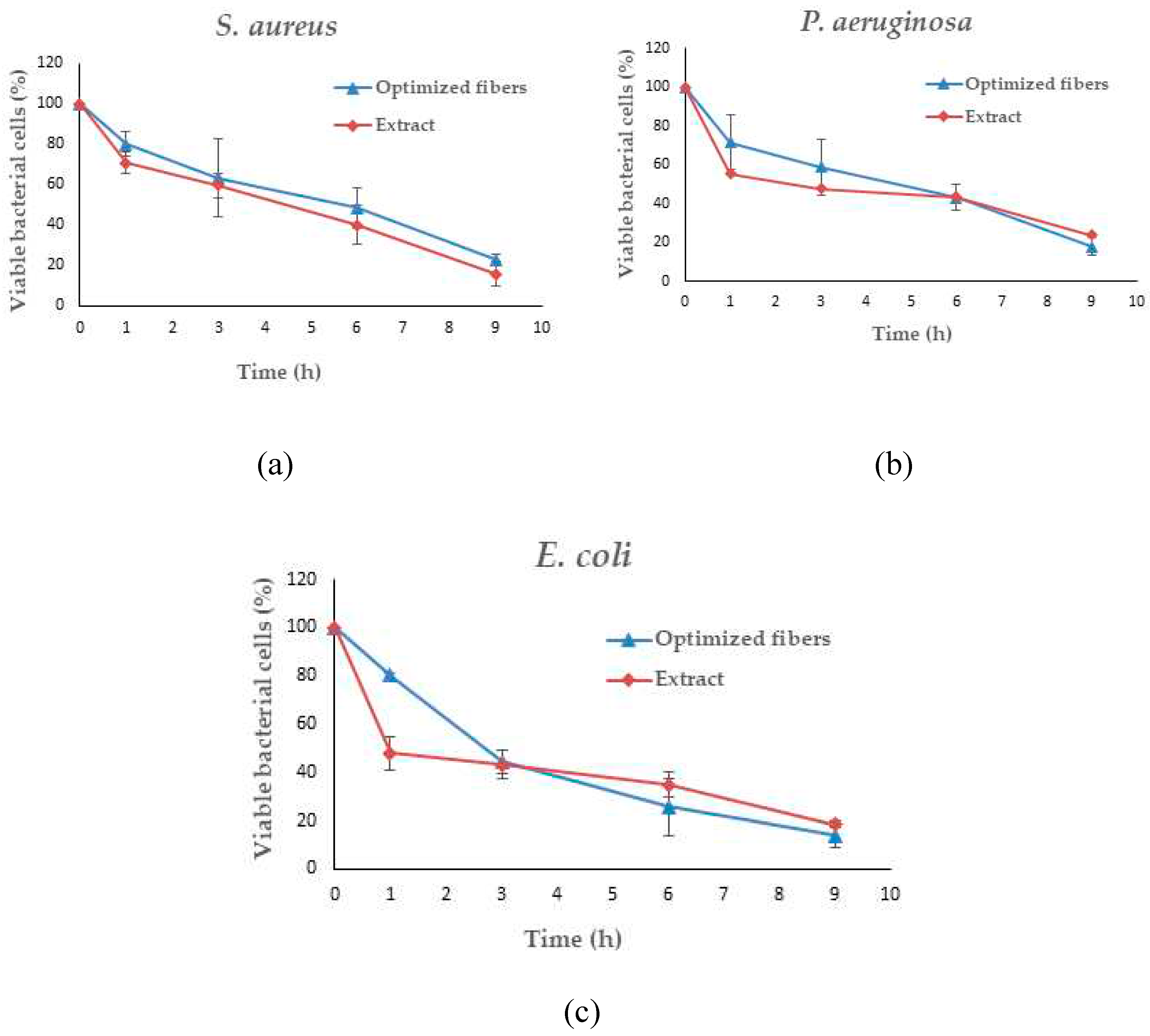

2.10. Antimicrobial activity of optimized fibers

A microbiological technique, the time-kill kinetics assay, is employed to assess the antimicrobial effectiveness of a substance within a predetermined time frame. As in a previous study [

30], the antibacterial capacity of optimized fibers against

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538P,

Escherichia coli DMST 4212, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027 was determined over time. The test microorganisms were subcultured from a suitably isolated colony on an agar plate into a new tube of sterile growth medium, TSB, in order to prepare the bacterial culture. The culture was incubated at 37 °C for 18 to 24 h in a bacterial incubator (Contherm Biosyn 6000CP; Contherm Scientific Ltd., Wellington, New Zealand). Following the incubation period, the microbial culture was evaluated at a wavelength of 600 nm using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Cary 60, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). An absorbance reading between 0.08 and 0.1 was obtained, which corresponds to a bacterial concentration of approximately 0.5 McFarland standard, or 10

8 CFU/mL. In this test [

11], the MIC values for the SA leaf extracts against

S. aureus,

E. coli, and

P. aeruginosa that were determined in the previous broth dilution assay were utilized. The bacterial suspension was diluted to a concentration of 10

6 CFU/mL. Test samples were sterilized under UV light for 30 min prior to the experiment. Subsequently, they were mixed with bacterial medium to achieve the desired concentration: 3.15 mg/mL for

S. aureus and 6.25 mg/mL for

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa, equivalent to 5 times the minimum inhibitory concentration (

MIC) of the SA extract. Extract and bacterial culture without test samples were employed as the reference and negative control, respectively. Every sample was incubated at 37 °C in a bacterial incubator. At each designated time interval, 100 µL of the withdrawn sample was diluted to a concentration of 10

5 CFU/mL before being applied to the sterile agar plate using a spreader. Then, for 18–24 h, all agar plates are incubated at 37 °C to promote colony formation. After the incubation period, the colonies on each plate were counted, and the percentage of viable bacterial cells was calculated using the following equation:

In this context, the microbial loads denoted as C0 and Ct, respectively, are expressed in CFU/mL for the initial time point and each time point specified.

4. Discussion

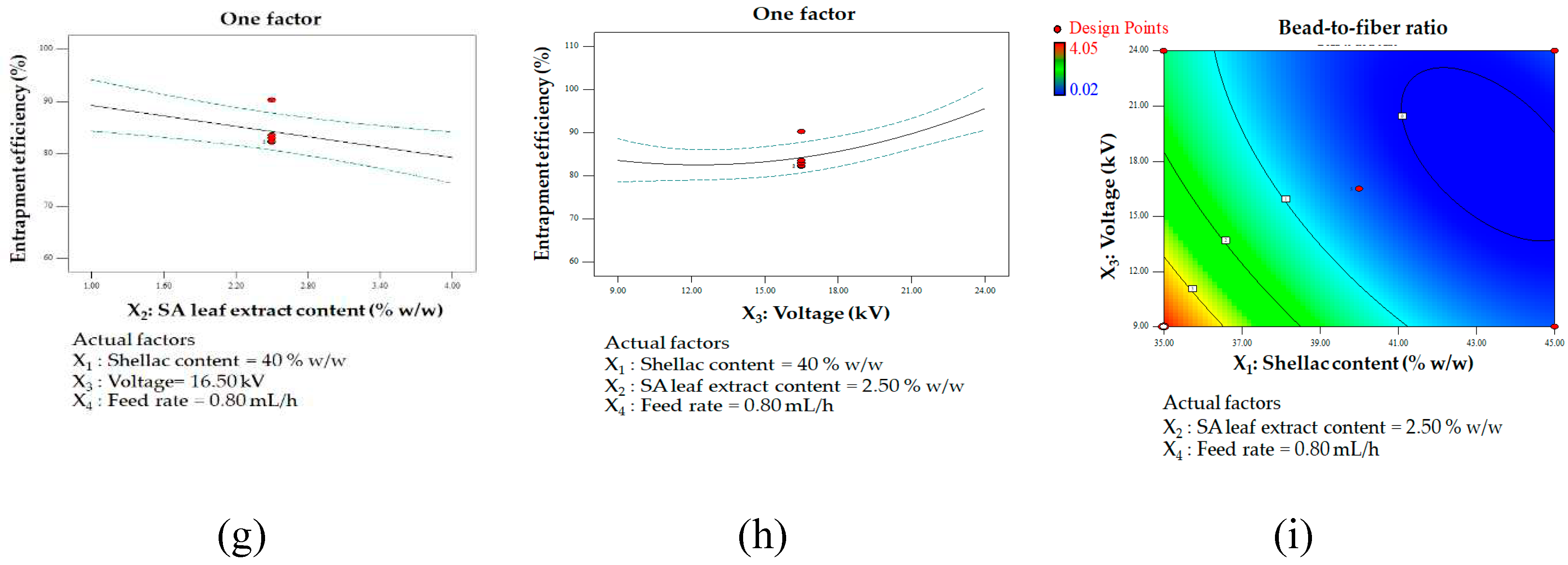

The outcome of electrospinning a polymer solution, including the structure and morphology of the nanofibers, is typically influenced by polymer-specific solution parameters, processing conditions, and ambient factors. Critical factors that influence the spinnability of a polymer solution include its concentration and electrical conductivity. The examination of the impact of applied voltage and shellac content on fiber diameter has yielded valuable insights into the electrospinning procedure. A correlation was observed between greater shellac concentration and the formation of larger fiber diameters; this was attributed to the increased viscosity and solution entanglement caused by the higher shellac concentration. An increase in the shellac content hinders the elongation resistance of the electrospinning process, leading to the generation of fibers with larger diameters [

62].

The adjustment of voltage levels significantly influenced the diameters of the fibers. At first, the implementation of low voltage resulted in an expansion of fiber diameter as a consequence of diminished electrostatic forces. This caused the polymer flow to experience reduced stretching, ultimately producing fibers with larger diameters. Following that, a decrease in fiber diameter was detected at a medium voltage level, possibly as a result of balanced electrostatic forces, which caused the polymer jet to stretch optimally and produce fibers with a smaller diameter. On the contrary, the implementation of elevated voltage resulted in an enlargement of the fiber diameter. This finding suggests that an excess of electrostatic forces may cause the polymer flow to undergo overstretching, thereby producing fibers with larger diameters [

62,

63]. Although certain studies have reported no correlation between the voltage applied and the diameter of the fibers [

64], it was discovered that increasing the voltage during the electrospinning process generated more charges, which improved the polymer solution's ability to stretch and contributed to the production of thinner nanofibers with a smaller diameter [

65]. These results are consistent with those of other investigations [

23,

66,

67] that have documented comparable results.

The observed correlation between varying levels of shellac content, extract content, and applied voltage with the bead-to-fiber ratio sheds light on the intricate dynamics of the electrospinning process. High levels of shellac content, extract content, and applied voltage were associated with a reduction in the bead-to-fiber ratio, indicating a tendency for smoother fiber formation under these conditions. The presence of fewer beads in conditions of higher shellac content can be attributed to the increased viscosity and improved solution entanglement. This impedes bead formation, favoring the development of smoother fibers. The elevated shellac content likely alters the balance between viscosity and surface tension, promoting a smoother electrospinning process. In contrast, lower shellac and extract content, as well as low voltage, were linked to enhanced bead formation. The lower shellac concentration results in reduced viscosity, allowing surface tension to exert a more dominant influence along the electrospinning jets. This dominance of surface tension, coupled with fewer chain entanglements, contributes to bead formation along the fibers [

62]. These findings suggest that the interplay between shellac concentration, extract content, and applied voltage significantly influences the morphology of electrospun fibers. Understanding these relationships provides valuable insights for optimizing the electrospinning process to achieve specific fiber characteristics, enhancing the potential applications of electrospun materials.

An elevated concentration of extract may potentially enhance the conductivity of the solution, thereby promoting the expansion of the polymer stream and reducing the formation of beads. A substantial increase in solution conductivity was observed subsequent to the introduction of the extract. In this context, the carboxylic acid composition of the extract is noteworthy. Compounds possessing carboxylic groups, rhein in particular, are capable of ionization, which produces charged species (ions) that enhance the conductivity of the solution [

68]. Furthermore, the inclusion of substantial quantities of extract resulted in an increase in the viscosity of electrospinning solutions. This phenomenon may potentially explain the decreased amount of bead formation. On the contrary, reduced concentrations of shellac and extract, along with low voltage, can cause a decline in the viscosity and conductivity of the solution. This, in turn, can contribute to inadequate polymer jet elongation and an increase in the formation of beads. Moreover, elevating the applied voltage can enhance the electrostatic forces exerted on the polymer flow, which facilitates the development of a more uniform and elongated fiber structure, consequently diminishing the occurrence of beads [

69]. These findings underscore the critical influence of extract concentration and processing parameters on the electrospinning process, providing valuable insights for optimizing conditions to achieve desired fiber morphologies. Effective control of these variables can lead to improved electrospinning outcomes for various applications in materials science.

A high degree of entrapment efficiency is discernible under particular circumstances, which involve the application of a high voltage and a low concentration of shellac and extract. These results indicate that the aforementioned conditions might augment the entrapment of the intended components within the fibers. It is probable that decreased concentrations of shellac and extract lead to enhanced solubility and decreased solution viscosity, thereby facilitating the successful incorporation of the extract into the polymer matrix. Conversely, as the concentration of both shellac and extract increased, a significant reduction in the efficiency of entrapment was detected. The potential cause of this decrease could be the existence of immobile constituents in the solution or the substances' poor solubility [

70]. These findings provide valuable insights into the interplay between solution composition and entrapment efficiency, offering guidance for optimizing electrospinning conditions to achieve effective incorporation of components within the fibers for various applications in materials science.

The implementation of elevated voltage emerges as a potential strategy to enhance the efficacy of entrapment in the electrospinning process. This observed phenomenon can be attributed to the intensified electrostatic forces and elongation of the polymer jet during electrospinning. The heightened capacity for elongation likely results in improved entrapment and incorporation of the target substances within the fibers. Moreover, the production of smoother, more uniform fibers, a consequence of elevated applied voltage, contributes to enhanced entrapment efficiency. The significant surface area of the polymers generated under high voltage facilitates the passive loading of the substance, further contributing to the increased level of entrapment [

71,

72]. In conclusion, the application of elevated voltage in the electrospinning process holds promise for enhancing the efficacy of entrapment. This improvement is attributed to intensified electrostatic forces, increased polymer jet elongation, and the production of smoother fibers, collectively leading to improved entrapment efficiency. The substantial surface area of the polymers created under elevated voltage also facilitates passive loading of the substance, solidifying the entrapment of the extract within the matrix. These findings underscore the importance of carefully managing processing parameters, specifically voltage, to optimize entrapment outcomes in electrospinning applications, offering valuable insights for various material science applications.

The optimized electrospun shellac fibers laden with SA leaf extract exhibited two distinct phases of release behavior in releasing media with pH values of 7.4 and 6.8: an initial burst release phase followed by a sustained release phase. A burst release may transpire when a fraction of the substance or compound is released rapidly from the surface or in close proximity to the surface region of the fibers. The burst release mechanism is commonly linked to molecules that are either loosely affixed to the fiber matrix or exist on its surface. This process facilitates an instantaneous discharge of the compound. After the initial explosive release, the rate of rhein release from each fiber sample peaked at 4 h and remained constant for the next 12 h, indicating a sustained release. Throughout this prolonged period, the residual rhein molecules were discharged at a relatively consistent rate. Typically, the sustained release was attributed to the drug or compound diffusing across the fiber matrix. A constant release rate is maintained as the molecules are continuously replenished from within the matrix as they diffuse out of the fibers [

73]. Additionally, the relatively slow dissolution rate of shellac, influenced by water absorption and expansion, further contributes to the formation of sustained release profiles, emphasizing the suitability of these fibers for controlled drug release applications [

53].

The optimized fibers demonstrated the highest percentage of rhein release, surpassing the release rates of the other fiber samples. Notably, the optimized fibers exhibited a faster release of rhein compared to both smaller- and larger-diameter fibers, achieving maximum release within 4 h. In contrast, smaller-diameter fibers peaked in release within 6 h, while larger-diameter fibers showed the highest percentage of release after 8 h. The observed results can be attributed to the impact of fiber diameter on drug release kinetics. Smaller-diameter fibers exhibited a faster release, reaching peak release within a shorter timeframe of 6 h. This phenomenon is linked to the increased surface area-to-volume ratio, which enhances the contact area between drug-loaded fibers and the surrounding medium. The elevated surface area promotes a higher rate of drug release [

74]. On the contrary, larger-diameter fibers, with reduced porosity and a lower surface area-to-volume ratio, demonstrated a slower release profile. The prolonged diffusion path and limited contact with the surrounding medium contributed to a delayed release of the drug. The optimization process applied to create the optimized fibers was specifically aimed at maximizing surface area and diffusion characteristics. This optimization likely accounts for the comparatively faster release observed in these fibers compared to others. These findings emphasize the critical role of fiber diameter in governing drug release kinetics in electrospun fibers, providing valuable insights for tailored drug delivery applications.

In the context of pH-dependent release, the cumulative release of rhein from all fiber samples at pH 6.8 was notably diminished compared to pH 7.4. This discrepancy can be attributed to the comparatively higher dissolution pH of shellac (around 7.3) and its poor solubility in aqueous solutions, resulting in limited rhein release at pH 6.8 [

75]. Conversely, at pH 7.4, where shellac exhibits full solubility, a higher cumulative release was observed [

58,

76]. The extract demonstrated complete solubility under both pH conditions. However, the release rate of rhein from the extract was substantially slower compared to the fibers loaded with the extract. This discrepancy suggests that fiber-mediated drug release could occur at an accelerated rate, potentially influenced by polymer degradation, hydration, or drug diffusion processes [

77]. The amorphous state of the extract and nanometer-sized diameters of the fibers significantly increase the rate of rhein release in PBS solution (pH 7.4) in comparison to the extract in its intact state. In addition, it should be noted that biphasic release profiles, which comprise an initial rapid release followed by a sustained release, may prolong the efficacy of bacterial inhibition [

78]. This unique release pattern further underscores the versatility and potential therapeutic benefits of the electrospun shellac fibers loaded with SA leaf extract.

The characterization studies provide strong evidence of the successful incorporation of SA leaf extract into the electrospun shellac fibers. The FTIR spectrum of the optimized fibers loaded with SA leaf extract revealed a notable shift in the majority of the extract's absorption peaks to higher frequency regions. This shift, particularly in OH stretching, C-H stretching, C=O stretching, and C=C-C stretching bands within aromatic rings, suggests a significant interaction between rhein (the primary component of the extract) and shellac within the fibers. This interaction is crucial as it signifies the compatibility and integration of the extract into the polymeric matrix, potentially influencing the release kinetics and overall performance of the fibers.

The PXRD patterns of both shellac and extract, characterized by the absence of diffraction peaks, indicate their amorphous states. Interestingly, this amorphous characteristic was maintained in the electrospun shellac fibers loaded with SA leaf extract. This consistency in amorphous structure suggests that the electrospinning process did not adversely impact the amorphous nature of shellac and extract. The amorphous state is often desirable in drug delivery systems, as it can enhance solubility and dissolution rates.

Given that SA leaf extract has demonstrated antimicrobial effectiveness against certain pathogens, the successful integration of the extract into the electrospun fibers opens up avenues for assessing the potency of these extract-loaded electrospun shellac fibers. Further evaluation will be crucial to determining the antimicrobial efficacy of the fibers and their potential applications in targeted drug delivery and infection control. A significant reduction in viable microbial cells was consistently observed at every incubation time point throughout the study on time-kill kinetics when both optimized fibers and the SA extract were utilized. Distinct differences were observed in the viable bacterial reduction rates between the fibers and the extract, as determined by analysis. Remarkably, it became evident within the first hour that the SA leaf extract demonstrated a more expeditious decline in microbial population in comparison to the optimized fibers. The observed discrepancies can potentially be attributed to differences in the release characteristics of the SA leaf extract and the optimized fibers. Prior studies have indicated a potential correlation between the antibacterial activities of electrospun fibers and the drug release behaviors exhibited by them [

74]. The potential reason for the observed rapid decrease in bacterial viability within the initial hour is that the extract may have a more immediate and direct effect. On the contrary, the optimized fibers have the potential to facilitate an extended and sustained antibacterial effect, which could lead to a more significant decrease throughout the nine-hour duration. The results of this study indicate that the optimized fibers successfully control the incremental discharge of antimicrobial agents from the matrix during the incubation phase. The implementation of controlled release may potentially extend the bacterial population's exposure to antimicrobial compounds, specifically rhein, which could lead to a gradual yet consistent decline in the viable bacterial population. Furthermore, the observed variations in antimicrobial effectiveness against distinct bacterial strains may be attributed to various factors, including the composition and concentration of active compounds in the SA leaf extract, as well as particular interactions between the fiber matrix and bacterial cells. While the antimicrobial effect between the extract and the optimized fibers did not exhibit a significant difference, this can be attributed to the rapid initial dissolution of the extract. However, towards the end of the incubation time, the optimized fibers demonstrated a higher release of rhein, contributing to a more effective reduction in microbial loads. Despite this, the form of the optimized fibers proved to be more convenient, facilitating better air passage and promoting optimal wound healing. This convenience stands as a distinct advantage of the fiber patch. Additional research is required to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms of these materials in order to yield practical implications for antimicrobial therapies. Furthermore, it is necessary to investigate the wider use of these fibers in the field of wound care in order to maximize their effectiveness in clinical environments.

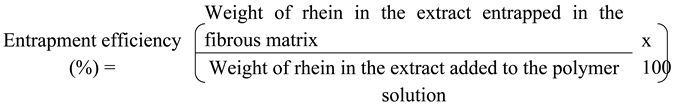

Figure 1.

Pareto chart showing the effect of parameters on fiber diameter (a) and bead-to-fiber ratio (b).

Figure 1.

Pareto chart showing the effect of parameters on fiber diameter (a) and bead-to-fiber ratio (b).

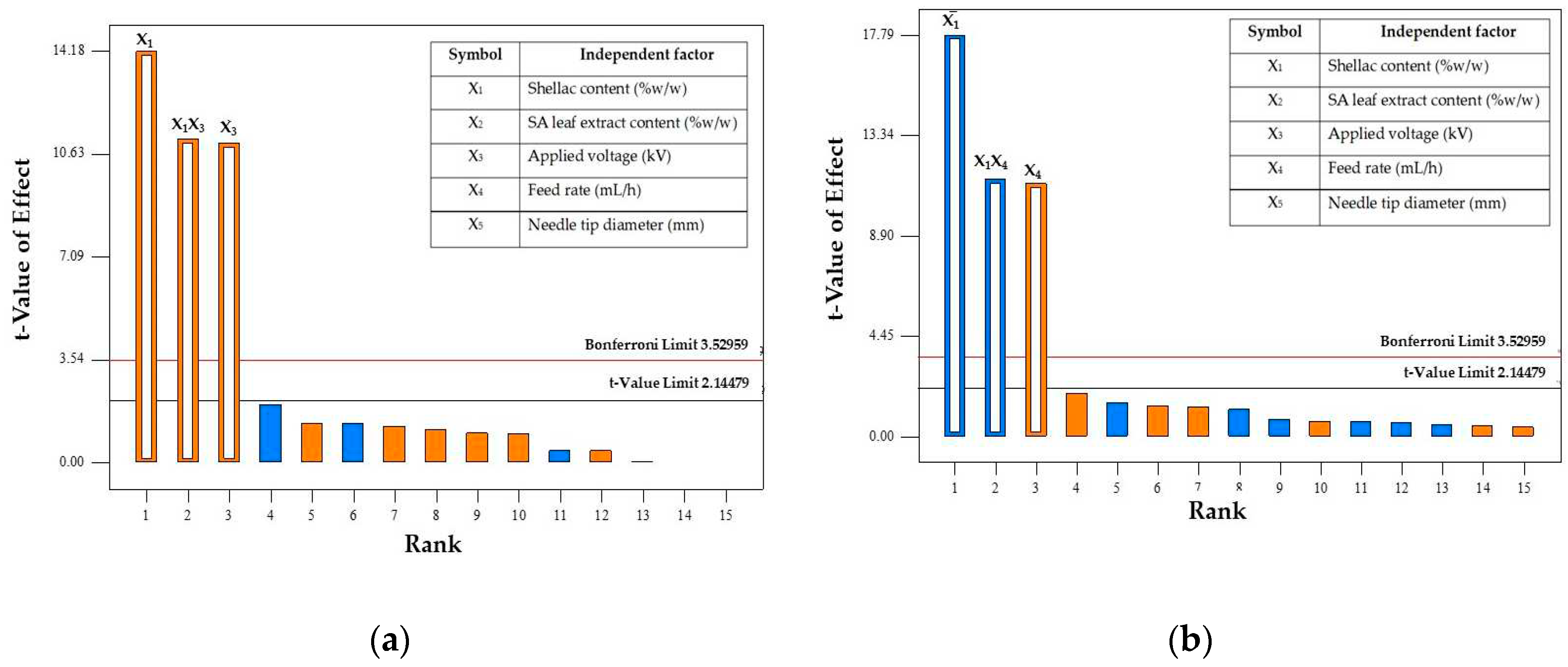

Figure 2.

Contour plots showing the interactions between factors on fiber diameter (a) and bead-to-fiber ratio (b).

Figure 2.

Contour plots showing the interactions between factors on fiber diameter (a) and bead-to-fiber ratio (b).

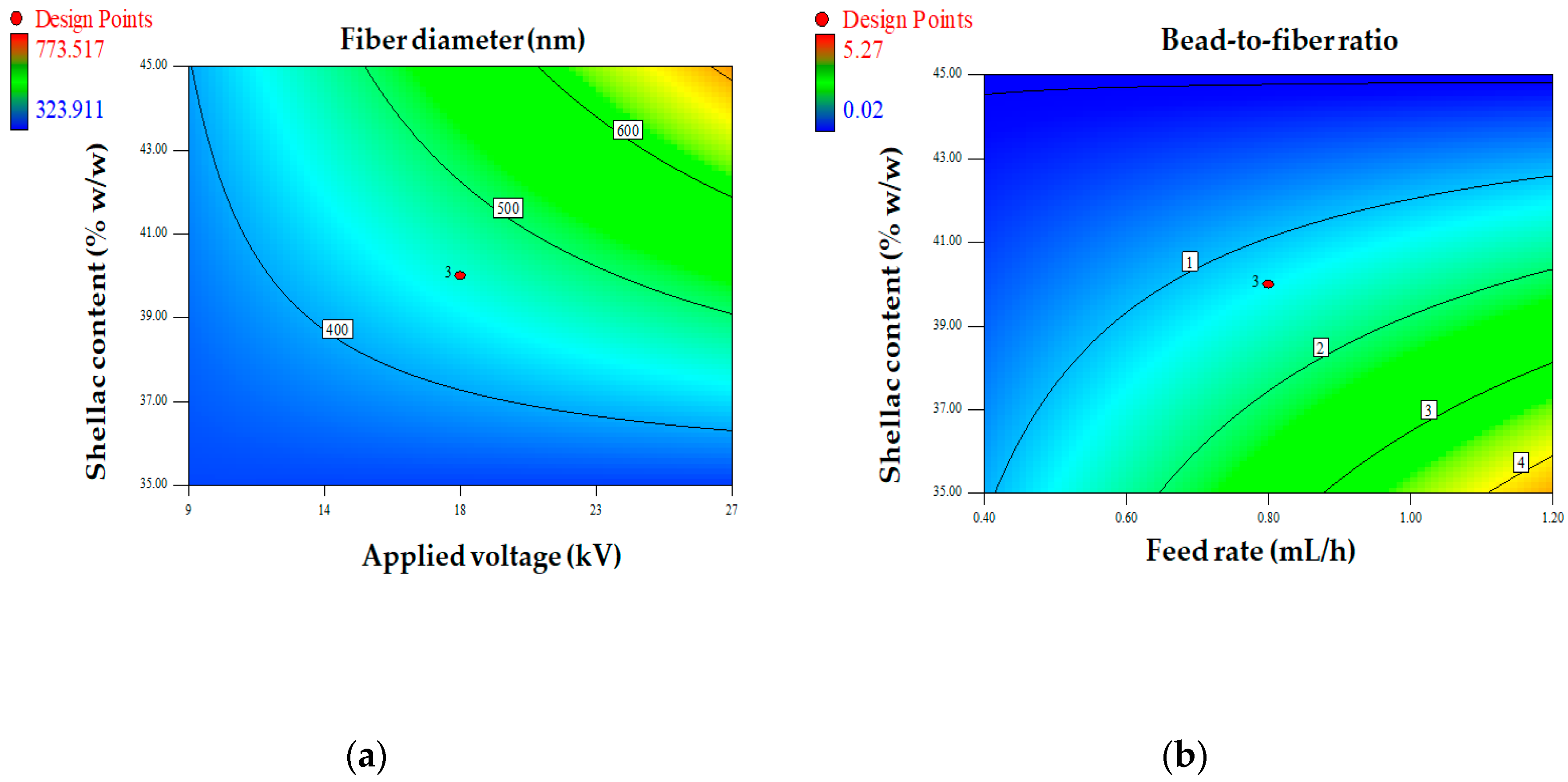

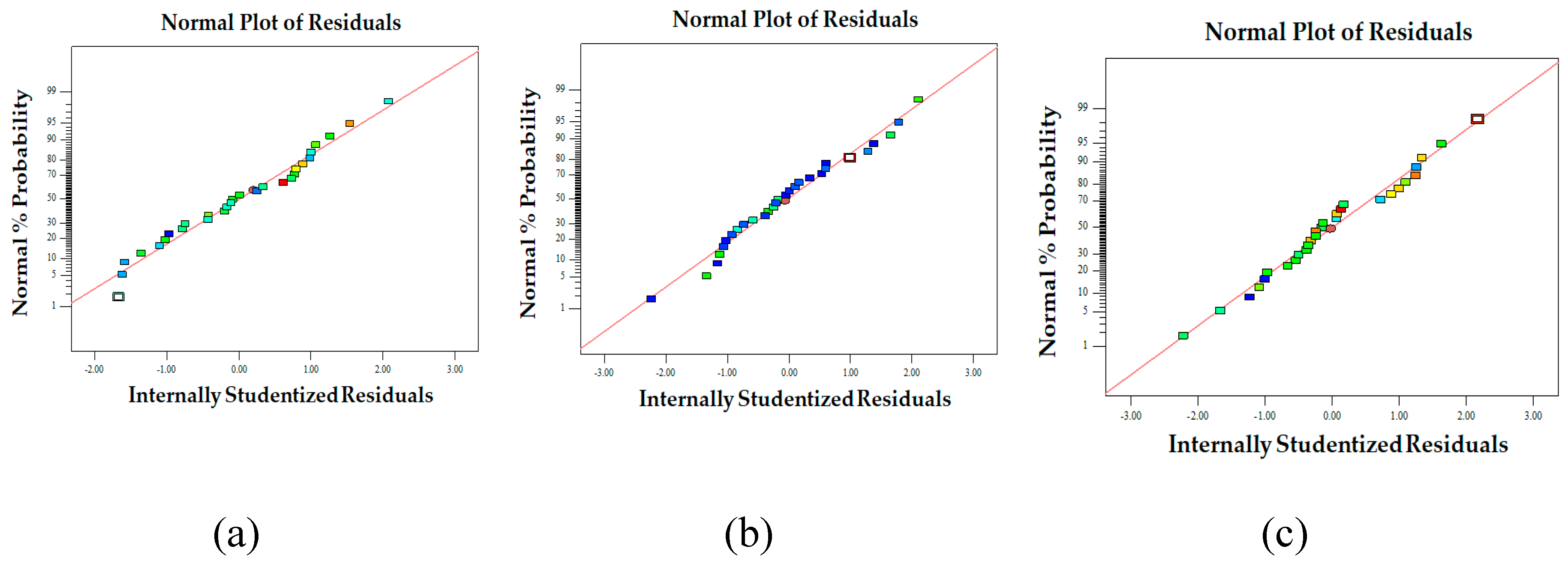

Figure 3.

Plot of the internally studentized residual's normal probability for fiber diameter (a) and bead-to-fiber ratio (b).

Figure 3.

Plot of the internally studentized residual's normal probability for fiber diameter (a) and bead-to-fiber ratio (b).

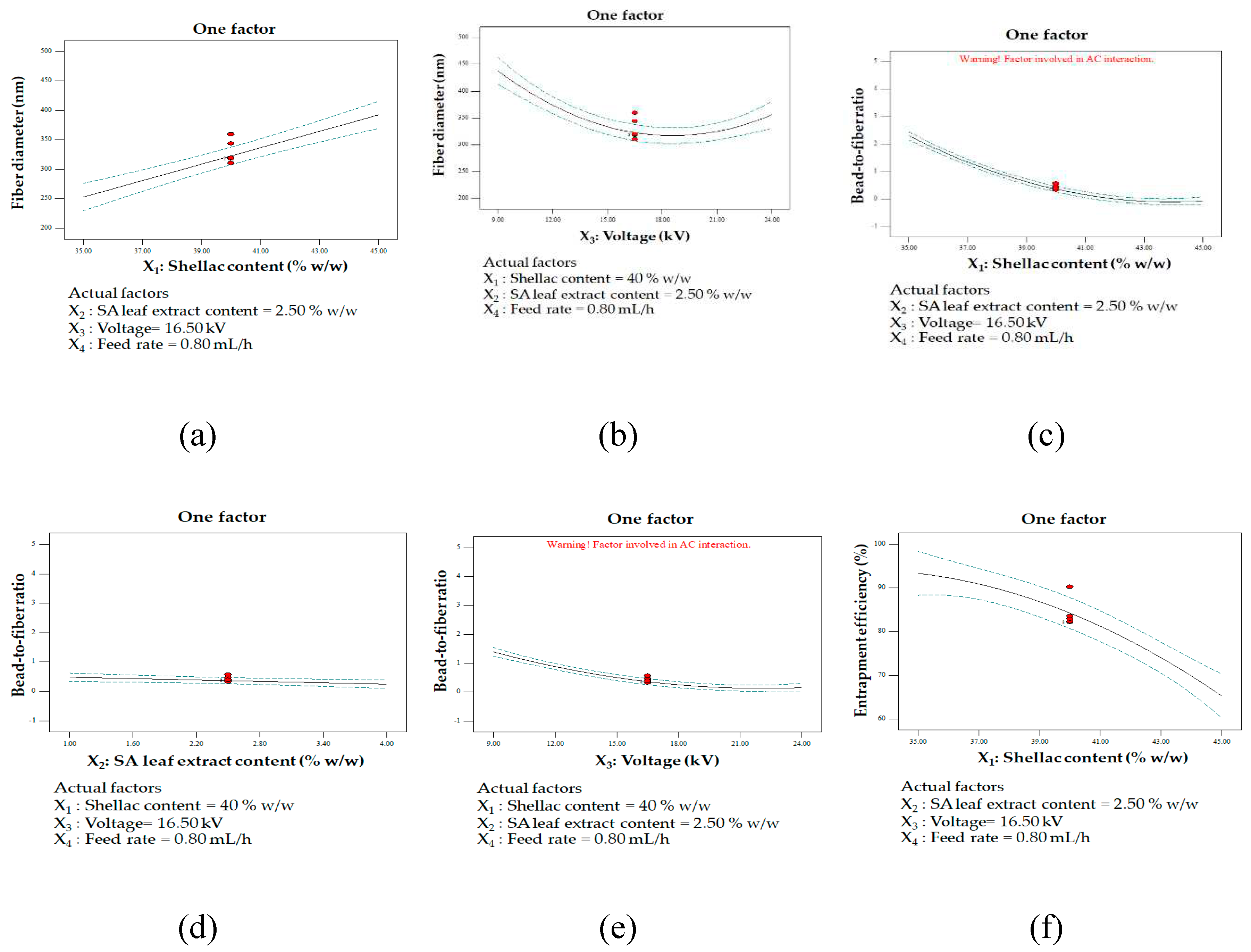

Figure 4.

Normal probability plot of the internally studentized residuals for fiber diameter (a), bead-to-fiber ratio (b), and entrapment efficiency (c).

Figure 4.

Normal probability plot of the internally studentized residuals for fiber diameter (a), bead-to-fiber ratio (b), and entrapment efficiency (c).

Figure 5.

One factor affecting multiple responses: fiber diameter influencing shellac content (a) and applied voltage (b); bead-to-fiber ratio influencing shellac content (c), extract content (d), and applied voltage (e); entrapment efficiency influencing shellac content (f), extract content (g), and applied voltage (h); contour plot illustrating the interaction between shellac content and applied voltage on bead-to-fiber ratio (i).

Figure 5.

One factor affecting multiple responses: fiber diameter influencing shellac content (a) and applied voltage (b); bead-to-fiber ratio influencing shellac content (c), extract content (d), and applied voltage (e); entrapment efficiency influencing shellac content (f), extract content (g), and applied voltage (h); contour plot illustrating the interaction between shellac content and applied voltage on bead-to-fiber ratio (i).

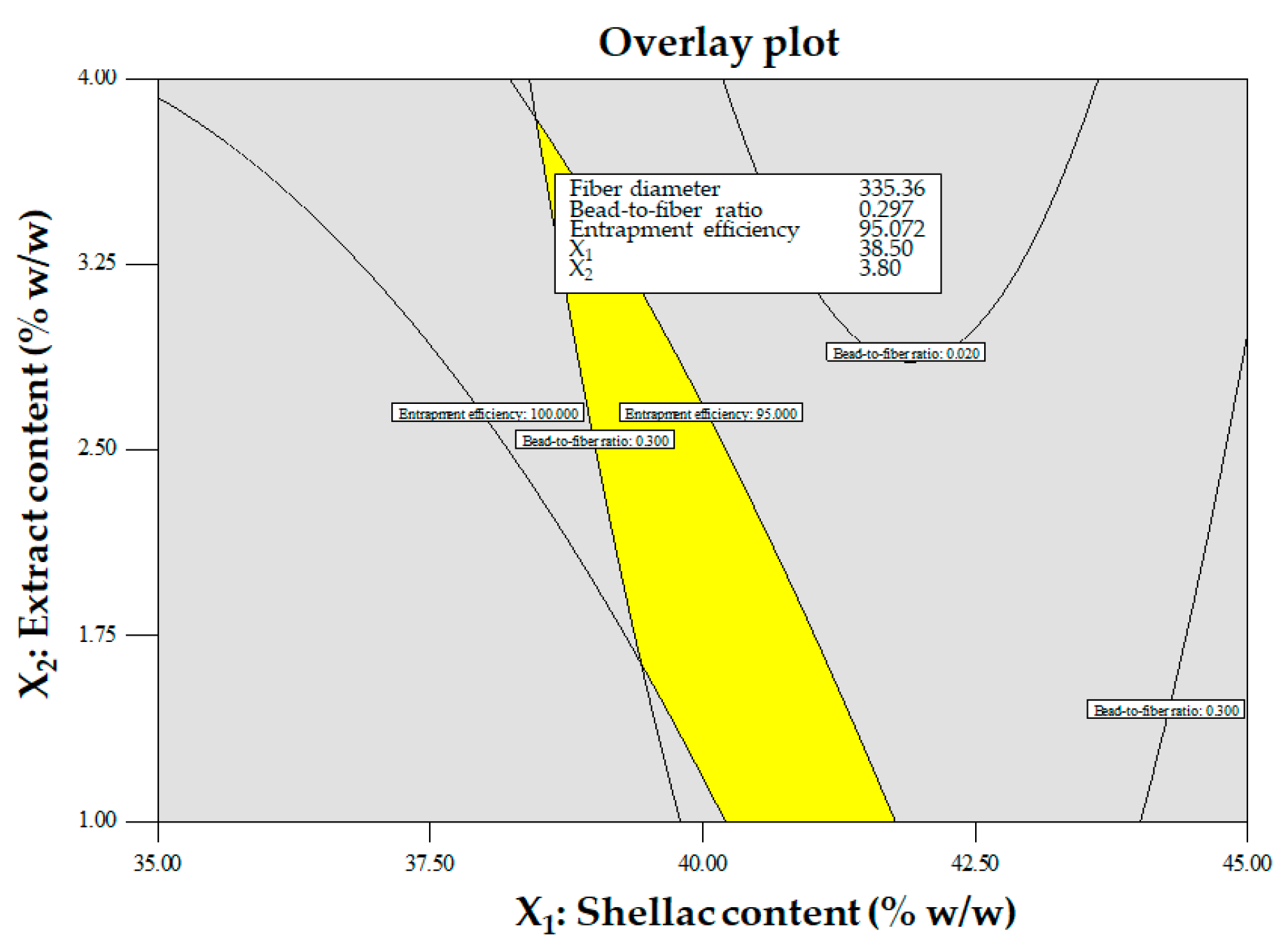

Figure 6.

Overlay contour plot for optimized conditions.

Figure 6.

Overlay contour plot for optimized conditions.

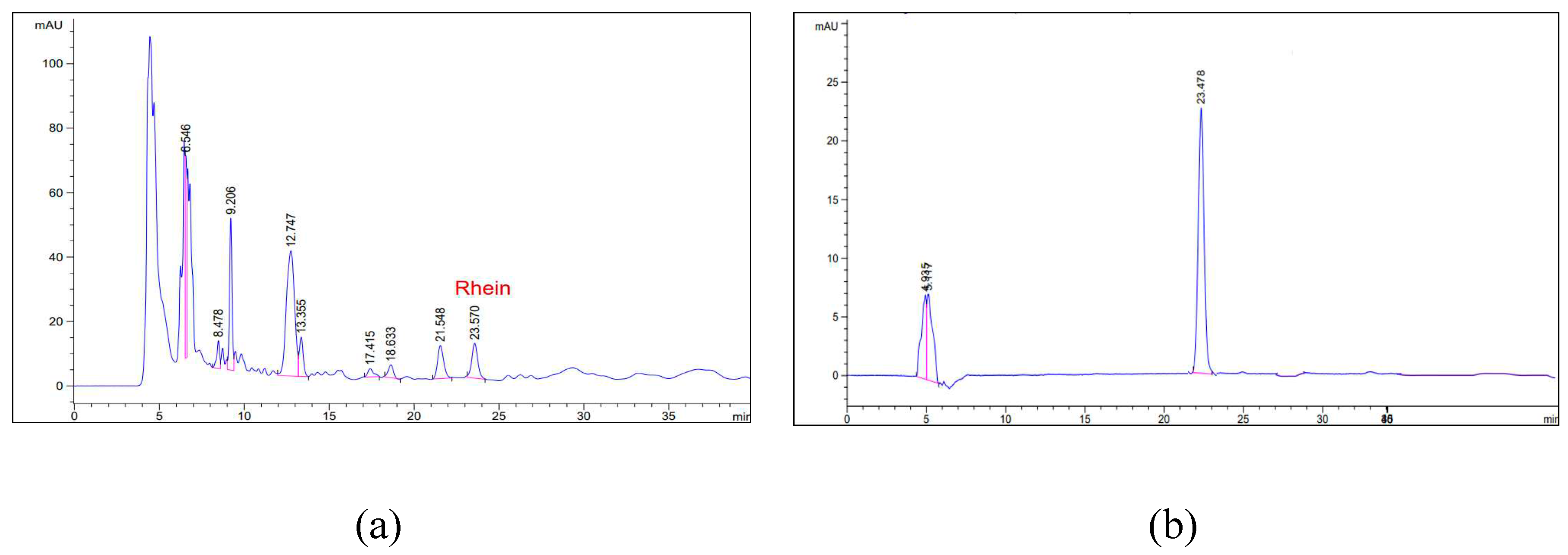

Figure 7.

The HPLC chromatograms of shellac fibers loaded with SA extract (a) and the standard rhein (b) reveal an identical retention time for the rhein peak at 23.5 min.

Figure 7.

The HPLC chromatograms of shellac fibers loaded with SA extract (a) and the standard rhein (b) reveal an identical retention time for the rhein peak at 23.5 min.

Figure 8.

Cumulative rhein release of fiber samples and extract at pH 7.4 (a) and pH 6.8 (b).

Figure 8.

Cumulative rhein release of fiber samples and extract at pH 7.4 (a) and pH 6.8 (b).

Figure 9.

SEM images showing the effect of individual factors on the fiber diameter. (a) Low shellac content (35% w/w) with 4% w/w extract content at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (b) High shellac content (45% w/w) with 4% w/w extract content at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (c) Low voltage (9 kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:4) at 0.8 mL/h. (d) High voltage (24 kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:4) at 0.8 mL/h.

Figure 9.

SEM images showing the effect of individual factors on the fiber diameter. (a) Low shellac content (35% w/w) with 4% w/w extract content at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (b) High shellac content (45% w/w) with 4% w/w extract content at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (c) Low voltage (9 kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:4) at 0.8 mL/h. (d) High voltage (24 kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:4) at 0.8 mL/h.

Figure 10.

SEM images showing the effect of individual factors on the bead-to-fiber ratio. (a) Low shellac content (35% w/w) with 1% w/w extract content, at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (b) High shellac content (45% w/w) with 1% w/w extract content at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (c) Low extract content (1% w/w) with 40% w/w shellac content at 16.5 kV and 0.4 mL/h. (d) High extract content (4% w/w) with 40% w/w shellac content at 16.5 kV and 0.4 mL/h. (e) Low voltage (9kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:2.5) at 0.4 mL/h. (f) High voltage (24 kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:2.5) at 0.4 mL/h.

Figure 10.

SEM images showing the effect of individual factors on the bead-to-fiber ratio. (a) Low shellac content (35% w/w) with 1% w/w extract content, at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (b) High shellac content (45% w/w) with 1% w/w extract content at 16.5 kV and 0.8 mL/h. (c) Low extract content (1% w/w) with 40% w/w shellac content at 16.5 kV and 0.4 mL/h. (d) High extract content (4% w/w) with 40% w/w shellac content at 16.5 kV and 0.4 mL/h. (e) Low voltage (9kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:2.5) at 0.4 mL/h. (f) High voltage (24 kV) with shellac-to-extract ratio (40:2.5) at 0.4 mL/h.

Figure 11.

PXRD patterns of bleached shellac, SA leaf extract, their physical mixtures, and optimized electrospun shellac fibers loaded with extract.

Figure 11.

PXRD patterns of bleached shellac, SA leaf extract, their physical mixtures, and optimized electrospun shellac fibers loaded with extract.

Figure 12.

DSC thermograms of bleached shellac, SA leaf extract, their physical mixtures, and optimized electrospun shellac fibers loaded with extract.

Figure 12.

DSC thermograms of bleached shellac, SA leaf extract, their physical mixtures, and optimized electrospun shellac fibers loaded with extract.

Figure 13.

FTIR spectrum of SA leaf extract, bleached shellac, their physical mixtures, and optimized electrospun shellac fibers loaded with extract.

Figure 13.

FTIR spectrum of SA leaf extract, bleached shellac, their physical mixtures, and optimized electrospun shellac fibers loaded with extract.

Figure 14.

Chemical structure of rhein.

Figure 14.

Chemical structure of rhein.

Figure 15.

Time-kill kinetics of optimized nanofibers and SA extract against S. aureus (a), P. aeruginosa (b), and E. coli (c).

Figure 15.

Time-kill kinetics of optimized nanofibers and SA extract against S. aureus (a), P. aeruginosa (b), and E. coli (c).

Figure 16.

Antimicrobial activities of optimized fibers.

Figure 16.

Antimicrobial activities of optimized fibers.

Table 1.

Experimental ranges and levels of independent variables in FFD.

Table 1.

Experimental ranges and levels of independent variables in FFD.

| Independent variables |

Symbol |

Level |

| Low (-1) |

Center (0) |

High (+1) |

| Shellac content (%w/w) |

X1

|

35 |

40 |

45 |

|

SA leaf extract content (%w/w) |

X2

|

1 |

2.5 |

4 |

| Applied voltage (kV) |

X3

|

9 |

18 |

27 |

| Feed rate (mL/h) |

X4

|

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

| Needle tip diameter (mm) |

X5

|

0.61 |

0.84 |

1.06 |

Table 2.

Experimental ranges and levels of independent variables in BBD.

Table 2.

Experimental ranges and levels of independent variables in BBD.

| Independent variables |

Symbol |

Level |

| Low (-1) |

Center (0) |

High (+1) |

| Shellac content (% w/w) |

X1

|

35 |

40 |

45 |

|

SA leaf extract content (% w/w) |

X2

|

1 |

2.5 |

4 |

| Applied voltage (kV) |

X3

|

9 |

16.5 |

24 |

| Feed rate (mL/h) |

X4

|

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

Table 3.

Design matrix and experimental responses of FFD.

Table 3.

Design matrix and experimental responses of FFD.

| Run |

Independent variables |

Responses |

X1

Shellac content

(%w/w) |

X2

Extract content

(%w/w) |

X3

Applied voltage

(kV) |

X4

Feed rate

(mL/h) |

X5

Needle tip

Diameter

(mm) |

R1

Fiber

diameter (nm)

|

R2

Bead-to- fiber ratio

|

| 1 |

-1 (35) |

-1 (1) |

1 (27) |

1 (1.2) |

1 (1.06) |

401.02±22.79 |

4.45±1.30 |

| 2 |

-1 (35) |

-1 (1) |

-1 (9) |

1 (1.2) |

-1 (0.61) |

398.99±3.71 |

5.27±1.07 |

| 3 |

0 (40) |

0 (2.5) |

0 (18) |

0 (0.8) |

0 (0.84) |

360.93±13.26 |

0.32±0.11 |

| 4 |

1 (45) |

-1 (1) |

1 (27) |

1 (1.2) |

-1 (0.61) |

773.52±25.61 |

0.17±0.02 |

| 5 |

1 (45) |

1 (4) |

1 (27) |

1 (1.2) |

1 (1.06) |

749.96±15.79 |

0.16±0.12 |

| 6 |

-1 (35) |

1 (4) |

1 (27) |

-1 (0.4) |

1 (1.06) |

396.22±10.62 |

0.56±0.29 |

| 7 |

-1 (35) |

-1 (1) |

1 (27) |

-1 (0.4) |

-1 (0.61) |

368.51±8.74 |

1.39±0.61 |

| 8 |

-1 (35) |

1 (4) |

-1 (9) |

-1 (0.4) |

-1 (0.61) |

374.57±9.27 |

1.43±0.81 |

| 9 |

1 (45) |

1 (4) |

-1 (9) |

1 (1.2) |

-1 (0.61) |

394.49±9.52 |

0.02±0.01 |

| 10 |

1 (45) |

-1 (1) |

1 (27) |

-1 (0.4) |

1 (1.06) |

727.32±4.43 |

0.17±0.07 |

| 11 |

-1 (35) |

1 (4) |

1 (27) |

1 (1.2) |

-1 (0.61) |

330.31±10.38 |

4.12±0.68 |

| 12 |

1 (45) |

1 (4) |

1 (27) |

-1 (0.4) |

-1 (0.61) |

680.65±8.98 |

0.28±0.12 |

| 13 |

-1 (35) |

1 (4) |

-1 (9) |

1 (1.2) |

1 (1.06) |

343.44±6.93 |

4.45±1.47 |

| 14 |

1 (45) |

1 (4) |

-1 (9) |

-1 (0.4) |

1 (1.06) |

419.49±3.24 |

0.02±0.01 |

| 15 |

1 (45) |

-1 (1) |

-1 (9) |

-1 (0.4) |

-1 (0.61) |

425.40±11.30 |

0.02±0.01 |

| 16 |

0 (40) |

0 (2.5) |

0 (18) |

0 (0.8) |

0 (0.84) |

323.91±7.84 |

0.34±0.08 |

| 17 |

-1 (35) |

-1 (1) |

-1 (9) |

-1 (0.4) |

1 (1.06) |

387.38±2.71 |

1.03±0.26 |

| 18 |

1 (45) |

-1 (1) |

-1 (9) |

1 (1.2) |

1 (1.06) |

435.88±5.41 |

0.02±0.01 |

| 19 |

0 (40) |

0 (2.5) |

0 (18) |

0 (0.8) |

0 (0.84) |

349.50±3.19 |

0.57±0.14 |

Table 4.

ANOVA for the selected factorial model.

Table 4.

ANOVA for the selected factorial model.

| Source |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F value |

P-value

Prob > F |

| Response 1- Fiber diameter |

| Model |

3.585× 105

|

3 |

1.195× 105

|

32.97 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1-Shellac content |

1.613× 105

|

1 |

1.613× 105

|

44.49 |

< 0.0001* |

| X3-Applied voltage |

97320.85 |

1 |

97320.85 |

26.85 |

0.0001* |

| X1X3

|

99939.92 |

1 |

99939.92 |

27.58 |

< 0.0001* |

| Residual |

54362.18 |

15 |

3624.15 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

53643.40 |

13 |

4126.42 |

11.48 |

0.0829** |

| Pure Error |

718.78 |

2 |

359.39 |

|

|

| Cor Total |

4.129× 105

|

18 |

|

|

|

| R2 = 0.8683 Adj R2 = 0.8420 Pred R2 = 0.8274 |

| Response 2- Bead-to-fiber ratio |

| Model |

53.90 |

3 |

17.97 |

64.62 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1-Shellac content |

29.81 |

1 |

29.81 |

107.22 |

< 0.0001* |

| X4-Feed rate |

11.83 |

1 |

11.83 |

42.56 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1X4

|

12.25 |

1 |

12.25 |

44.06 |

< 0.0001* |

| Residual |

4.17 |

15 |

0.28 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

4.13 |

13 |

0.32 |

16.47 |

0.0587** |

| Pure Error |

0.039 |

2 |

0.019 |

|

|

| Cor Total |

58.07 |

18 |

|

|

|

| R2 = 0.9282 Adj R2 = 0.9138 Pred R2 = 0.9016 |

| Significant *p < 0.01 Not significant ** |

Table 5.

Actual (coded) values for the BBD process variables.

Table 5.

Actual (coded) values for the BBD process variables.

| Run |

Independent variables |

Responses |

X1

Shellac content

(%w/w) |

X2

Extract content

(%w/w) |

X3

Applied voltage

(kV) |

X4

Feed rate

(mL/h) |

R1

Fiber diameter

(nm) |

R2

Bead-to-fiber ratio |

R3

Entrapment efficiency

(%) |

| 1 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

343.99±13.90 |

0.33±0.02 |

82.33 |

| 2 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

1 (24.00) |

-1 (0.40) |

335.26±3.92 |

0.43±0.05 |

96.04 |

| 3 |

1 (45.00) |

0 (2.50) |

1 (24.00) |

0 (0.80) |

446.89±13.01 |

0.09±0.08 |

77.44 |

| 4 |

-1(35.00) |

-1 (1.00) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

310.52±29.01 |

2.37±0.49 |

96.81 |

| 5 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

359.51±5.93 |

0.46±0.12 |

82.94 |

| 6 |

1 (45.00) |

-1 (1.00) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

355.37±10.94 |

0.05±0.04 |

70.53 |

| 7 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

1 (24.00) |

1 (1.20) |

336.23±20.90 |

0.16±0.03 |

90.05 |

| 8 |

-1(35.00) |

0 (2.50) |

-1 (9.00) |

0 (0.80) |

325.04±26.16 |

4.05±0.23 |

102.99 |

| 9 |

0 (40.00) |

1 (4.00) |

1 (24.00) |

0 (0.80) |

351.06±20.18 |

0.09±0.01 |

95.52 |

| 10 |

1 (45.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

1 (1.20) |

414.27±19.82 |

0.02±0.01 |

68.97 |

| 11 |

-1(35.00) |

0 (2.50) |

1 (24.00) |

0 (0.80) |

312.57±8.51 |

1.47±0.20 |

105.42 |

| 12 |

-1(35.00) |

1 (4.00) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

280.29±21.53 |

1.99±0.65 |

77.55 |

| 13 |

1 (45.00) |

1 (4.00) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

422.24±22.60 |

0.02±0.01 |

66.39 |

| 14 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

319.79±17.05 |

0.57±0.11 |

83.54 |

| 15 |

0 (40.00) |

1 (4.00) |

0 (16.50) |

-1 (0.40) |

276.04±10.89 |

0.09±0.04 |

76.70 |

| 16 |

1 (45.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

-1 (0.40) |

390.48±15.29 |

0.03±0.01 |

58.88 |

| 17 |

-1(35.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

-1 (0.40) |

259.94±23.12 |

2.13±0.13 |

99.81 |

| 18 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

-1 (9.00) |

1 (1.20) |

426.59±11.20 |

1.65±0.44 |

80.84 |

| 19 |

0 (40.00) |

1 (4.00) |

0 (16.50) |

1 (1.20) |

277.07±10.24 |

0.07±0.02 |

87.74 |

| 20 |

0 (40.00) |

-1 (1.00) |

0 (16.50) |

1 (1.20) |

291.10±7.12 |

0.34±0.06 |

93.81 |

| 21 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

310.52±2.16 |

0.39±0.07 |

90.24 |

| 22 |

0 (40.00) |

-1 (1.00) |

1 (24.00) |

0 (0.80) |

356.75±23.34 |

0.22±0.03 |

99.44 |

| 23 |

0 (40.00) |

1 (4.00) |

-1 (9.00) |

0 (0.80) |

480.01±8.57 |

1.16±0.40 |

77.87 |

| 24 |

1 (45.00) |

0 (2.50) |

-1 (9.00) |

0 (0.80) |

523.86±6.69 |

0.25±0.06 |

59.84 |

| 25 |

-1(35.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

1 (1.20) |

226.20±5.42 |

2.62±0.97 |

88.39 |

| 26 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

0 (16.50) |

0 (0.80) |

318.21±2.27 |

0.38±0.10 |

82.19 |

| 27 |

0 (40.00) |

0 (2.50) |

-1 (9.00) |

-1 (0.40) |

462.28±7.76 |

1.31±0.47 |

74.99 |

| 28 |

0 (40.00) |

-1 (1.00) |

0 (16.50) |

-1 (0.40) |

332.74±10.42 |

0.37±0.12 |

85.82 |

| 29 |

0 (40.00) |

-1 (1.00) |

-1 (9.00) |

0 (0.80) |

410.33±6.35 |

1.48±0.69 |

95.13 |

Table 6.

ANOVA for the quadratic model reducing the response surface.

Table 6.

ANOVA for the quadratic model reducing the response surface.

| Source |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F value |

P-value

Prob > F |

| Response 1- Fiber diameter |

| Model |

1.175 x 105

|

3 |

39162.78 |

43.96 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1-Shellac content |

58597.40 |

1 |

58597.40 |

65.77 |

< 0.0001* |

| X3-Voltage |

19954.60 |

1 |

19954.60 |

22.40 |

< 0.0001* |

| X32

|

38936.35 |

1 |

38936.35 |

43.70 |

< 0.0001* |

| Residual |

22273.41 |

25 |

890.94 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

20585.04 |

21 |

980.24 |

2.32 |

0.2151*** |

| Pure Error |

1688.37 |

4 |

422.09 |

|

|

| Cor Total |

1.398 x 105

|

28 |

|

|

|

| R2 = 0.8406 Adj R2 = 0.8215 Pred R2 = 0.7835 |

| Response 2- Bead-to-fiber ratio |

| Model |

27.59 |

6 |

4.60 |

162.82 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1-Shellac content |

16.73 |

1 |

16.73 |

592.40 |

< 0.0001* |

| X2 Extract content |

0.17 |

1 |

0.17 |

5.87 |

0.0241** |

| X3-Voltage |

4.61 |

1 |

4.61 |

163.31 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1X3

|

1.46 |

1 |

1.46 |

51.84 |

< 0.0001* |

| X12

|

3.94 |

1 |

3.94 |

139.49 |

< 0.0001* |

| X32

|

1.18 |

1 |

1.18 |

41.94 |

< 0.0001* |

| Residual |

0.62 |

22 |

0.028 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

0.59 |

18 |

0.033 |

3.78 |

0.1032*** |

| Pure Error |

0.035 |

4 |

8.63 x 10-3

|

|

|

| Cor Total |

28.21 |

28 |

|

|

|

| R2 = 0.9780 Adj R2 = 0.9720 Pred R2 = 0.9546 |

|

Response 3-Entrapment efficiency

|

| Model |

3537.04 |

5 |

707.41 |

21.82 |

< 0.0001* |

| X1-Shellac content |

2377.95 |

1 |

2377.95 |

73.34 |

< 0.0001* |

| X2- Extract content |

297.57 |

1 |

297.57 |

9.18 |

0.0060* |

| X3-Voltage |

434.97 |

1 |

434.97 |

13.42 |

0.0013* |

| X12

|

169.60 |

1 |

169.60 |

5.23 |

0.0317** |

| X32

|

198.54 |

1 |

198.54 |

6.12 |

0.0211** |

| Residual |

745.75 |

23 |

32.42 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

699.71 |

19 |

36.83 |

3.20 |

0.1340*** |

| Pure Error |

46.04 |

4 |

11.51 |

|

|

| Cor Total |

4282.80 |

28 |

|

|

|

| R2 = 0.8259 Adj R2 = 0.7880 Pred R2 = 0.7052 |

| Significant *p < 0.01 ** 0.01 < p < 0.05 Not significant *** |

Table 7.

Criteria for the optimization of electrospinning conditions.

Table 7.

Criteria for the optimization of electrospinning conditions.

| Name |

Goal |

Lower limit |

Upper limit |

| X1: Shellac content (%w/w) |

in range |

35 |

45 |

| X2: Extract content (%w/w) |

in range |

1 |

4 |

| X3: Applied voltage (kV) |

in range |

9 |

24 |

| X4: Feed rate (mL/h) |

equal to 0.8 mL/h |

0.4 |

1.2 |

| Fiber diameter (nm) |

in range |

250 |

500 |

| Bead-to-fiber ratio |

in range |

0.02 |

0.3 |

| Entrapment efficiency (%) |

in range |

95 |

105 |

Table 8.

Optimum conditions with desirable results.

Table 8.

Optimum conditions with desirable results.

| No |

Applied voltage

(kV) |

Feed rate

(mL/h) |

Shellac content

(% w/w) |

Extract content (% w/w) |

Fiber diameter

(nm) |

Bead-to- fiber ratio |

Entrapment efficiency

(%) |

Desirability |

| 1 |

23.99 |

0.8 |

38.50 |

3.80 |

335.36 |

0.30 |

95.071 |

1 |

Table 9.

Confirmation.

| Response |

Prediction |

Experimental value |

95% PI low |

95% PI high |

| Fiber diameter |

335.36 |

305.77 ± 10.93 |

291.594 |

379.126 |

| Bead-to-fiber ratio |

0.30 |

0.29 ± 0.05 |

0.0267618 |

0.567025 |

| Entrapment efficiency |

95.071 |

96.38 ± 1.42 |

86.1137 |

104.028 |

Table 10.

Solution properties of different shellac-extract ratios.

Table 10.

Solution properties of different shellac-extract ratios.

Shellac content

(% w/w) |

SA leaf extract content

(% w/w) |

Viscosity

(mPa. S)

(Mean ± SD) |

Conductivity (µS)

(Mean ± SD) |

Surface tension (mN/m)

(Mean ± SD) |

| 35 |

0 |

30.81 ± 1.74 |

94.17 ± 0.15 |

28.15 ± 0.15 |

| 40 |

0 |

59.49 ±0.98 |

77.27 ± 0.31 |

28.56 ± 0.23 |

| 45 |

0 |

132.85 ±1.22 |

71.50 ±1.39 |

28.94 ± 0.06 |

| 35 |

1 |

35.89 ± 0.61 |

170.80 ± 3.36 |

27.64 ± 0.31 |

| 35 |

2.5 |

48.18 ± 2.82 |

178.50 ±0.10 |

28.52 ±0.08 |

| 35 |

4 |

52.71 ± 1.29 |

187.80 ± 1.01 |

30.23 ± 0.28 |

| 40 |

1 |

73.57 ± 1.22 |

160.10± 0.10 |

28.24 ± 0.16 |

| 40 |

2.5 |

91.89 ± 2.09 |

165.47 ± 1.29 |

28.64 ± 0.07 |

| 40 |

4 |

108.96 ± 4.36 |

179.17 ±0.74 |

29.08 ±0.05 |

| 45 |

1 |

159.41 ± 3.81 |

158.00 ± 0.56 |

30.60 ± 0.11 |

| 45 |

2.5 |

183.61 ±1.42 |

160.40 ±0.10 |

30.32 ± 0.09 |

| 45 |

4 |

267.98 ± 6.94 |

176.50 ± 1.18 |

32.05 ± 0.19 |

| 38.5 (Optimized) |

3.8 (Optimized) |

88.36 ± 3.15 |

180.20 ±0.66 |

29.11 ± 0.09 |