1. Introduction

Nowadays, nanotechnology is an exciting research topic for researchers in academia and industrial fields due to its deals with forming matter at the nano range with more enhanced features compared to their bulk counterparts. Recently, nanofiber is one of the nanotechnologies that have widely attracted attention from several research due to their exhibits of many specific properties such as lightweight, large surface-to-volume ratio, and high porosity [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These appropriate nanofiber properties are especially suitable for use as a material for several applications, i.e., filter [

5] and catalyst [

6] etc. It is well known that nanofibers can be fabricated using various techniques. Among those techniques, electrospinning is a versatile, widely studied, and commonly employed technique used to produce nanofibers with unique properties, as we mentioned, such as high surface area-to-volume ratio, high porosity, tunable features, and cost-effective process of manufacturing nanofibers [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, electrospinning is the most efficient way to prepare nanofibers with synergistic characteristics for new applications through blending multiple polymers with individual functionalities in the solution phase. The morphology of electrospun fiber mats depended on the processing and polymer solution spinning parameters like the applied voltage, polymer flow rate, solution concentration, molecular weight of the polymer, relative humidity, diameter of the needle, and tip-to-collector distance [

11,

12,

13,

14]. These nanofibers find applications in various fields, including tissue engineering [

15,

16,

17], filtration [

18,

19,

20], energy storage [

21,

22], adsorbents [

23,

24,

25] and drug delivery [

26,

27,

28,

29]. In recent years, electrospinning has also emerged as a promising method for producing antibacterial nanofibers due to their potential in combating microbial infections and their application in wound healing [

30,

31,

32,

33]. This technique offers numerous enticing possibilities, one of which involves the inclusion of drugs, functional fillers, or bioactive molecules within the core of electrospinning fibers [

34].

Over the past few decades, using polymeric materials as nonwoven fiber mats by electrospinning process has been a popular approach to medical applications. For example, Ullah et al. [

35] prepared the ultrafine of bioactive among oil-loaded electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers for wound dressing applications. They also reported that these fibrous materials exhibited in-vitro biocompatibility, cell viability, and good antibacterial and antioxidant properties. They suggested that these nonwoven electrospun fiber mats can be used to heal wound infections. Hashemikia et al. [

36] also prepared the electrospun fiber mats of chitosan/polyethylene oxide/silica nanofibers composited with ciprofloxacin for applying wound healing. They also investigated in vitro and in vivo drug delivery. They mentioned that the silica particle played a crucial role in collagen creation, accelerating wound healing. Furthermore, the essential organic compound from natural products has attracted attraction to be used as a functional drug for application in the electrospun fiber mat. Santos and coworkers [

37] fabricated the electrospun fiber mats of cellulose acetate composited with annatto, its natural dye exhibiting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, for wound dressing. These functionalized materials exhibit well the result of inflammatory process and biocompatibility. However, we also found that several types of materials are used in electrospinning to produce electrospun nanofibers, i.e., poly(vinyl alcohol) [

38], poly(ethylene glycol) [

39], polyamide [

40], poly(vinylidene fluoride) [

41], polycaprolactone [

42], so on.

As a safe biopolymer, polylactic acid (PLA) is one of the candidate materials for fabricating electrospun fiber mats. Due to its several advantageous properties, such as non-toxicity, good transparency, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and good thermal and mechanical performance [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Consequently, many studies have already demonstrated the application of PLA-electrospun as a direct material for specific applications in various fields. However, it is well known that the neat PLA exhibits brittle and low flexibility properties. Therefore, blending or composites with different materials is beneficial for improving their properties. Presently, the functionalities of biocomposite nanofibers (fabricated from biodegradable matrices reinforced with fillers) are becoming of utmost interest as environmentally friendly materials and potentially specific applications, particularly in the medical fields. The easiest way to make the functionality electrospun fiber mats is to add the functionalities materials into a polymer solution prior to the spinning process. Recently, producing PLA-based nonwoven fiber mats through the electrospinning technique has received growing attention. Several previous studies have stated that the functionalized electrospun fiber mats, as well as antimicrobial properties, were prepared from PLA composited with metal-based nanoparticles such as silver (Ag) [

49], zinc oxide (ZnO) [

50], and titanium dioxide (TiO

2) [

51,

52], etc. Hence, it is not surprising that PLA has been widely used to produce nanofibers and help inorganic materials fabricate nanofibers' functionalities for various applications.

In the present work, we aimed to implement the fabrication of antimicrobial nonwoven fiber mats based on PLA loaded with Ag nanoparticles by electrospinning techniques. Here, Ag nanoparticles were prepared by reducing silver nitrate (AgNO3) while preparing the PLA solution for electrospinning. The effects of the Ag concentrations within the polymer suspension on the morphology and physical properties of the obtained nanofibers were investigated. Additionally, the chemical interaction, morphology surface, thermal properties, water absorbency, and antibacterial properties were examined by using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscope (SEM), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), swelling ratio, as well as qualitative and quantitative antibacterial tests, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Commercial-grade Poly (lactic acid) (PLA) was obtained from NatureWorks LLC (USA) with the trade name of Ingeo 3100 HP (Mw = 140,000 g/mol). Silver nitrate was purchased from LOBA Chemie Co., Ltd., India. Dichloromethane and dimethylformamide were purchased from Sigma Aldrich-Merck Co., Ltd., Germany. Other chemical agents were analytical-grade purity and used as received without further purification.

2.2. Electrospinning process

Here, the biocomposite nanofibers were fabricated by using the electrospinning process as follows: First, PLA powders were dissolved in a co-solvent of dimethylformamide and dichloromethane at the ratio of 50:50 at a concentration of 10 wt% at 80 °C for 3 h. Approximately amounts of silver nitrate (for the desired concentrations of 1, 3, and 5 wt%) were added into the 10 wt% PLA solution and continuously stirred for 12 h to obtain homogeneous solutions. Second, the polymer suspensions were treated with ultrasonication to destroy small air bubbles in the solution. Third, the suspension was loaded into a 10-mL plastic syringe. A metal needle was fitted to a syringe and connected to a high-voltage generator. A rotating metal wrapped with aluminum foil and connected to the ground was used as the collector for the composite nanofibers. The polymer suspension was pumped through a syringe controller at a flow rate of 0.05 mL/h during electrospinning. The syringe used in this experiment had a capillary tip diameter of 21 gauge and contained an attached copper wire used as the positive electrode. A voltage of 10 kV was applied to the spinning solution, and a dense web of fibers was collected on the aluminum foil. The nanofibers were collected on a metal collector wrapped with aluminum foil and kept at a fixed distance of 10 cm away from the needle tip of the spinneret. The obtained nonwoven fiber mats were dried initially at 60 °C for 8 h prior to further characterization. In this paper, to be convenient for discussing the experimental results, the samples are referred to as PLA/Ag-1, PLA/Ag-3, and PLA/Ag-5, which correspond to a 10 wt% PLA solution in which silver nitrate is suspended at concentrations of 1, 3 and 5 wt%, respectively.

2.3. Scanning electron microscope

The surface morphology of all fabricated nonwoven fiber mats was examined through SEM (Model: Quanta 450, FEI, USA). Before analysis, all samples were cut into small pieces (1×1 cm2) and sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold. All images were captured and operated using secondary electrons and 15 kV of accelerating voltage after the sputter-coating of specimens with a gold nanolayer. Moreover, the nanofiber dimensions' average fiber diameter and distribution were investigated via image analysis using ImageJ software (ImageJ, version 1.45, USA) from at least 100 measurements per sample.

2.4. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FTIR was performed to examine the chemical interaction between silver nitrate molecules and PLA molecular chains. An FTIR spectrometer (Model: Invenio, Bruker, USA) in ATR mode equipped with a diamond crystal was used for investigation. All the spectra were recorded in transmittance mode with 4 cm-1 resolution in the wavenumber range of 4000 cm-1 - 400 cm-1 under ambient conditions.

2.5. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis

Thermal properties of nonwoven fiber mats based on PLA were characterized using a DSC technique (Model: DSC 200 F3, Netzsch, Canada). All the samples were in a sealed aluminum pan, and each piece used was approximately 5.0 mg. They were sequentially heated from 30 to 200 °C, cooled to 25 °C, and then reheated to 200 °C at the rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen flow of 50 mL/min. Then, the degree of crystallinity of the obtained nonwoven fiber mats (

) was calculated by equation (1) [

53].

where

is the melting enthalpy for 100% crystalline PLA (93.0 J/g) [

54];

is the melting enthalpy for the nonwoven fiber mats and w is the mass fraction of PLA in the fiber mats.

2.6. Water absorbency

The swelling ratio of the nonwoven fiber mats based on PLA was determined from the relationship between the swollen and dry weight of the sample. The procedure for testing has been previously reported as follows [

55]: At first, the sample of PLA nonwoven fiber mats was weighed to obtain the initial dry weight (W

d) and dimensions. The nonwoven fiber mat sample was then placed in a beaker containing de-ionized water and was removed after 5 min. Then, the wet sample was rapidly dried with filter paper to remove the excess water and subsequently weighed to define W

t. This process continued, with the weight after immersion for selected times. Finally, the water absorbency or swelling ratio (%SR) of each nonwoven fiber mat was also calculated according to Eq (2):

where W

d is the dry weight of the nonwoven fiber mats, and W

S is the weight of the swollen sample immersed in the de-ionized water at room temperature at the selected times. All the tests were performed in triplicate (n = 3) under identical conditions.

2.7. Antibacterial testing

The in vitro antibacterial activities in both qualitative and quantitative tests were investigated onto each electrospun fibers sample for evaluation against Gram-negative (

E. coli) and Gram-positive (

S. aureus) bacterial strains, using the disk diffusion susceptibility and plate colonies count method described previously [

56], respectively. Briefly, the qualitatively antibacterial activity of the samples was investigated as follows. The bacteria used were cultured in an LB medium and then incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, which contained approximately 1.5×10

6 CFU/mL (0.5 McFarland). A 10

-2 dilution of the incubated bacteria was transferred to an LB agar plate. Disc shapes of 5.00 mm diameter was cut from the samples. The nonwoven fiber mat sample of neat PLA was used as a control for comparing the potential antibacterial properties with the other samples. Next, the cut-out discs were placed on the LB agar plates, spread with bacteria, and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After the incubation period, the diameters of the bacterial inhibition zone were measured in mm with a transparent ruler. These experiments were performed in triplicate.

In addition, the potential quantitative antibacterial activity in the samples was performed as follows. The bacterial cells,

S. aureus and

E. coli were grown overnight in an LB broth medium at 30 °C to bacteria grown to contain approximately 1.5×10

6 CFU/mL (0.5 McFarland), the same as the disk diffusion susceptibility test. Then, the 10

-2 dilution suspensions of grown bacteria were prepared, and the given content of the samples at the ratio of 1:1 by weight was added to the suspensions. The nonwoven fiber mats from the neat PLA were also used as controls. The suspensions were shaken in a rotary shaker (Model XY-80, Taitec, Koshigaya, Saitama, Japan) at the constant speed of 120 rpm for 3 h at 30 °C and were diluted 10-fold repeatedly. One hundred microliters of an aliquot of these cell solutions were seeded onto LB agar using a surface spread plate technique with a glass stick. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The number of viable bacterial colonies (CFU) was counted and then calculated to the initial number of bacterial cells before dilution. The antibacterial efficacy (%R) of the nonwoven fiber mats was calculated according to the following equation (3):

where V

c is the number of bacterial cells in the presence of the nanofiber from the neat PLA (CFU/mL) and V

s is the number of bacterial cells in the presence of those nanofibers from PLA/Ag (CFU/mL). All the experiments were repeated in triplicates, and the results are presented as mean values.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Scanning electron microscope

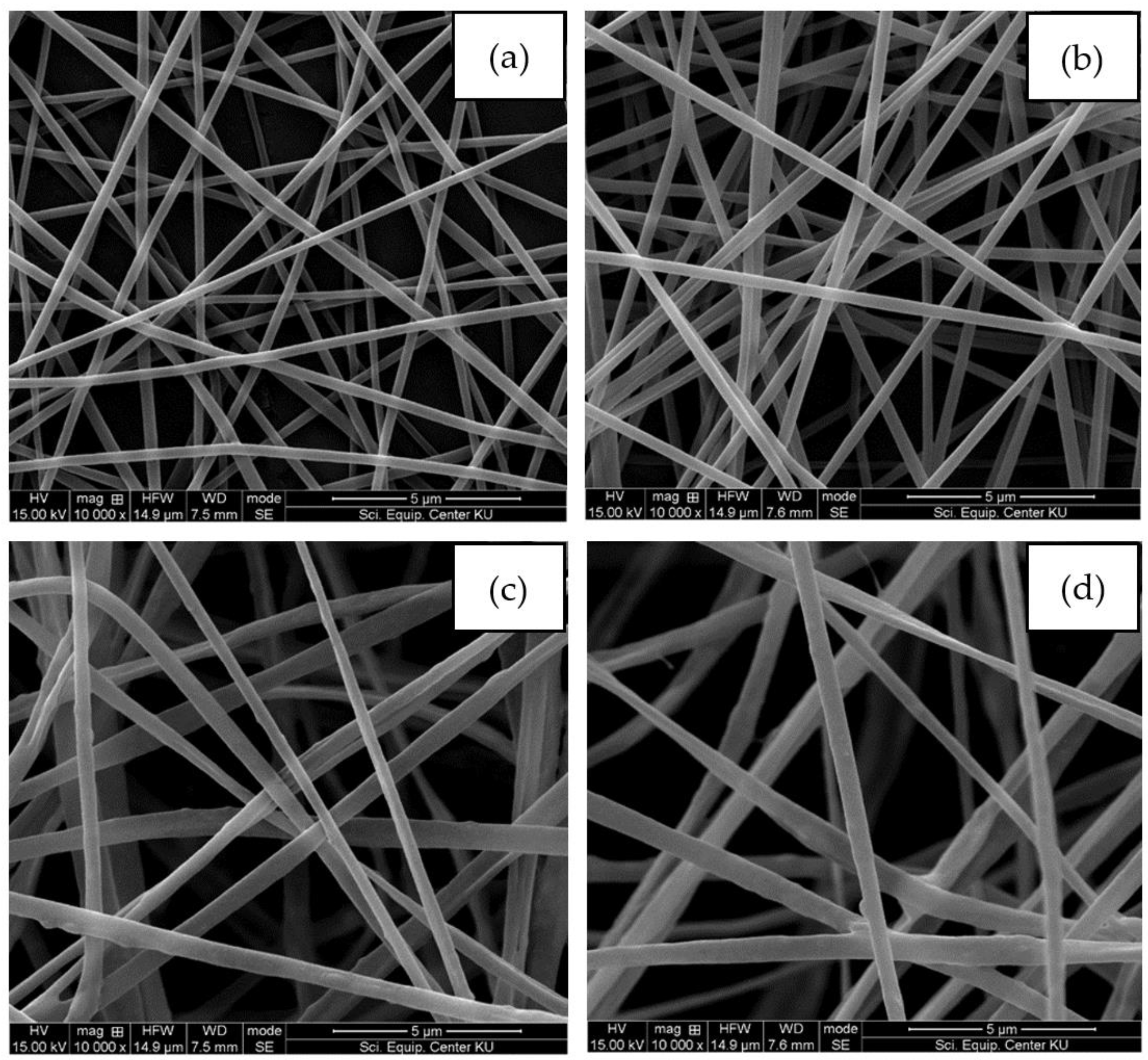

The morphological surfaces of the nonwoven fiber mats from all samples are shown in

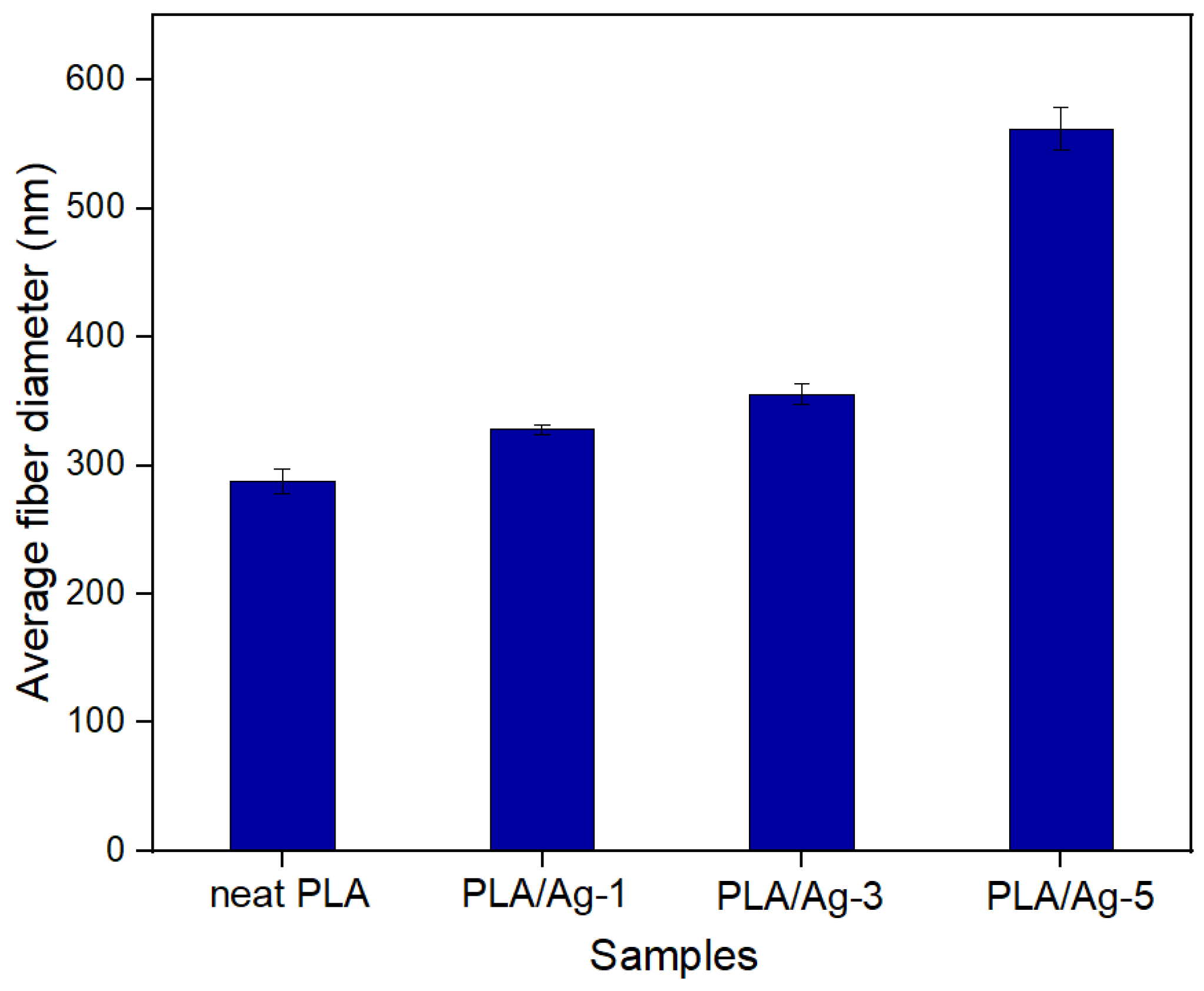

Figure 1. We found that all the samples of fabricated electrospun fibers exhibited smooth and uniform fiber diameters without the occurrence of bead defects on the surface. By contrast, from this figure, the size of the electrospun fibers becomes larger when addition the Ag into PLA matrices. It is well-known that fiber size is one of the main parameters affected by the physical properties of the obtained nonwoven fiber mats. Hence, it is essential to measure this parameter to evaluate the nonwoven fiber mats' performance. From the experimental results, the average diameters of the nanofibers were approximately 287.80±9.56 nm, 327.96±4.01 nm, 355.33±7.86 nm, and 561.94±16.87 nm for PLA, PLA/Ag-1, PLA/Ag-3, and PLA/Ag-5, respectively. A comparison of the average fiber diameter of electrospun based on PLA structures from different Ag concentrations is illustrated in

Figure 2. Interestingly, these results suggest that the addition of Ag increased the average diameter of the nanofibers. In addition, it would be improved with increases in the Ag concentration. This is probably due to the addition of Ag nanoparticles increasing the polymer suspension concentration, which might have resulted in the formation of thicker nanofibers, the same trend as the result of Maleki et al. [

57,

58].

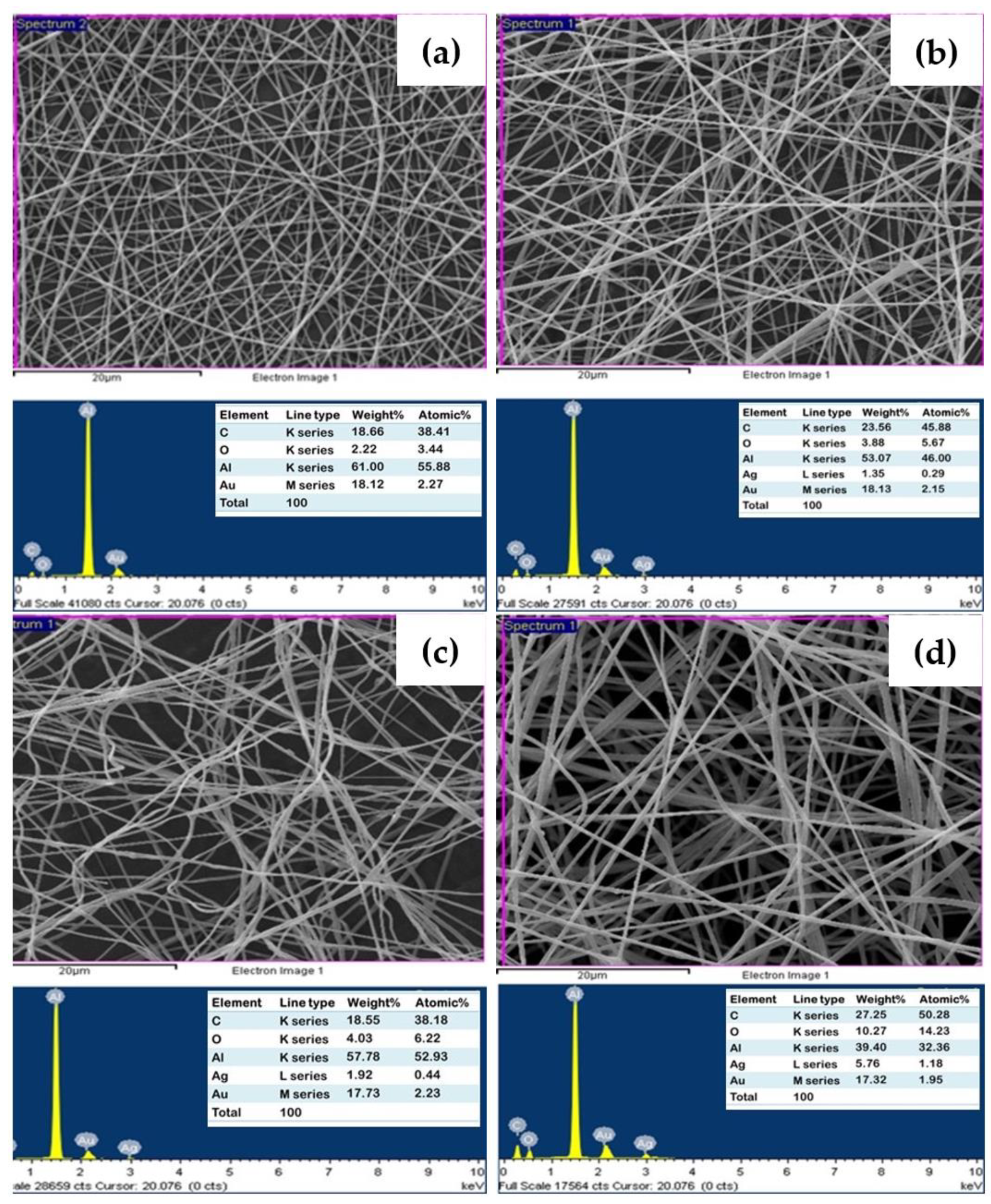

In addition, to confirm the element compositions, the energy dispersive X-ray spectrum of all fabricated nonwoven fiber mats based on PLA were investigated. The results revealed that the nonwoven fiber mats of PLA composited with Ag at different concentration displays the significant peaks of Ag, which reflect the composition of Ag elements in the nonwoven fiber mats. However, it did not display this peak in the EDS spectra of neat PLA, as shown in

Figure 3. This result suggested that the silver was successfully incorporated in the PLA nanofibers. The amounts of silver within the PLA nanofibers were approximately 1.35%, 1.92%, and 5.76% for PLA/Ag-1, PLA/Ag-3 and PLA/Ag-5, respectively. The amounts of Ag content within nonwoven fiber mats increased with an increase of AgNO

3 concentrations during the prepared PLA suspensions for the electrospinning process. Furthermore, all nonwoven fiber mats show the elemental characteristics peak of PLA molecule, i.e., carbon (C) and oxygen (O). Strongly signal peaks of Al and Au came from the substrate of the electrospun fiber collector and coating gold prior to SEM investigation, respectively.

3.2. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The incorporation of silver into PLA nanofibers, as well as the chemical reaction between those molecules upon electrospinning, were confirmed by FTIR, as shown in

Figure 4. All the IR spectra of nonwoven fiber mats exhibited peaks at approximately 1184 cm

-1 and 1755 cm

-1, which can be indexed to the characteristic of C=O stretching and C-O stretching of the carboxyl group in the PLA molecules [

59,

60]. In addition, the small and weak peaks around 2995 and 3350 cm

-1 are associated with the stretching of CH

2, and O-H, respectively [

61]. Silver nitrate used as a precursor to produce Ag nanoparticles was also investigated for comparison. It displays a strong peak around 1190 cm

-1, and the position of this peak changed little, while its intensity gradually weakened, intensities and this peak would shift to lower wavenumbers. This indicates that the addition of silver nitrate has intermolecular reaction with PLA molecules. Furthermore, a broad band in the range of 600 to 800 cm

−1 could be attributed to Ag–O vibration [

62]

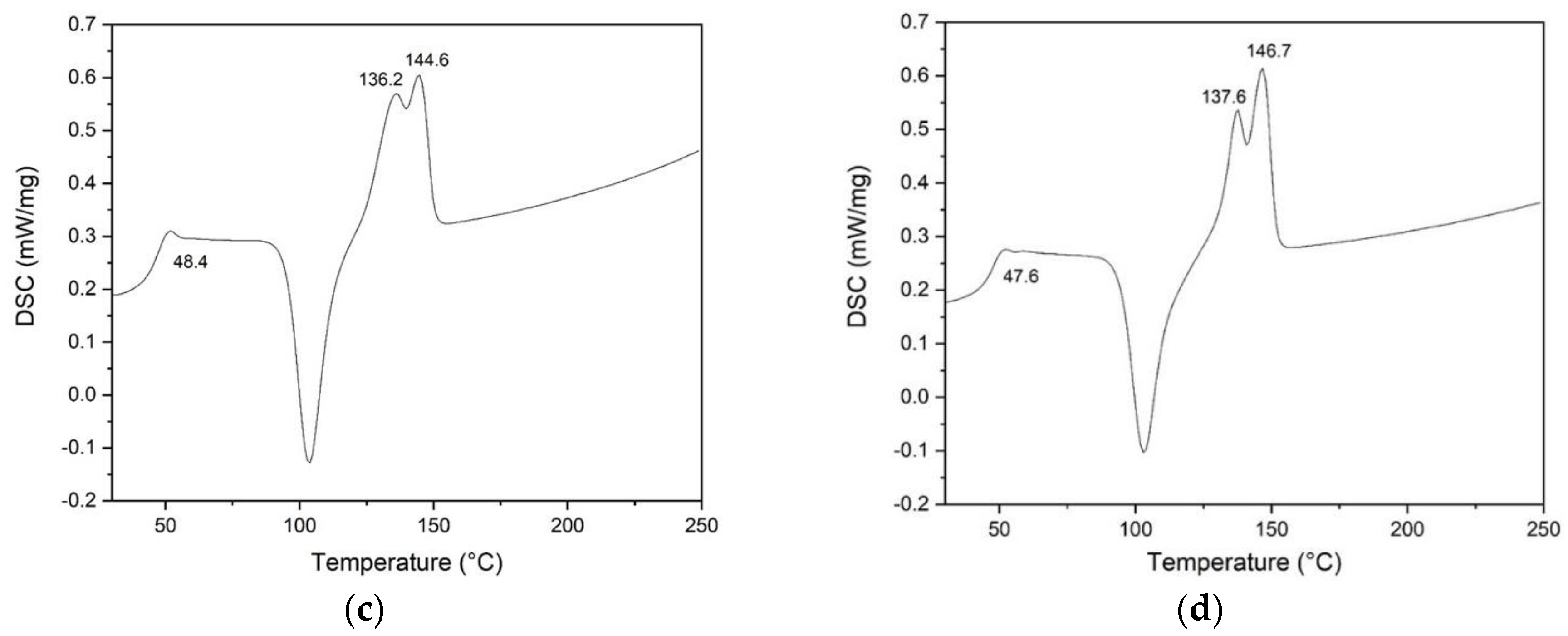

3.3. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis

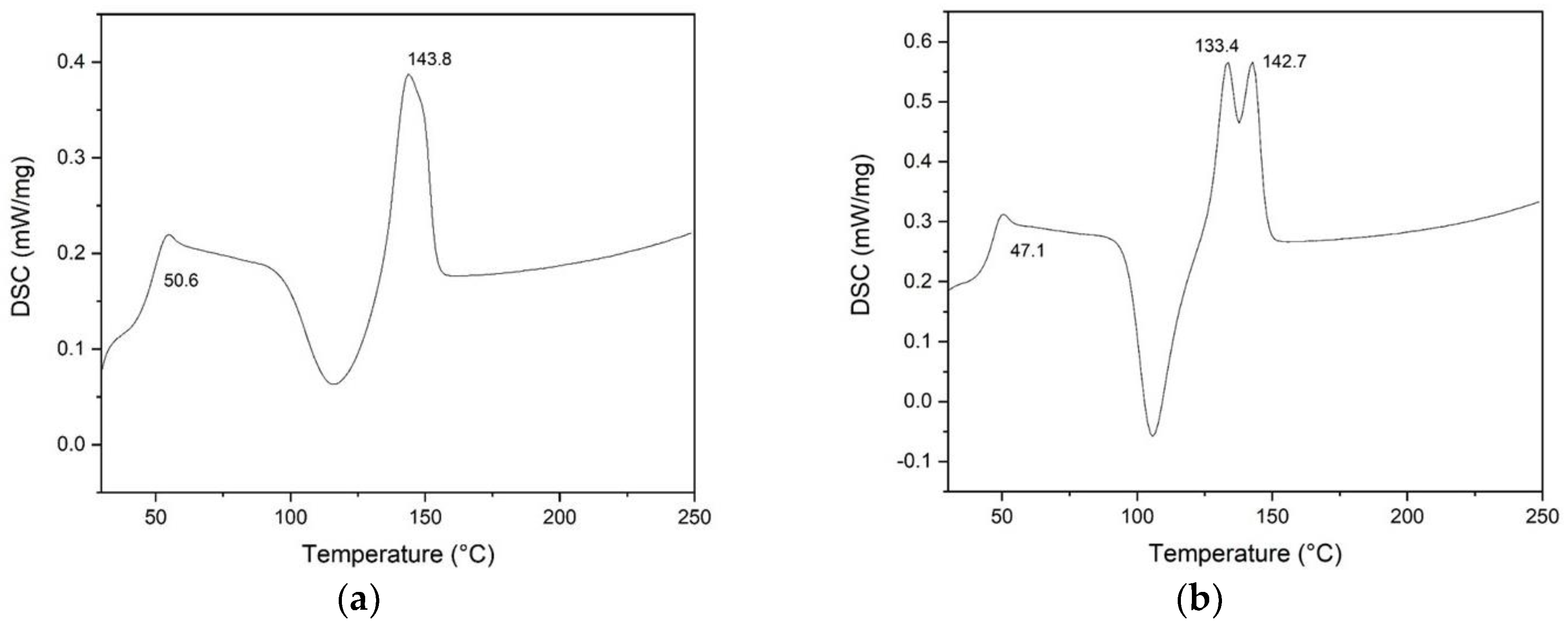

DSC thermogram results are presented in

Figure 5. The values of glass temperature (

Tg), melting temperature (

Tm), melting enthalpy

, and the degree of crystallinity of the electrospun fiber PLA containing the various Ag concentrations were recorded in

Table 1. Observably, the fabricated nonwoven fiber mats from PLA composited with Ag dominantly display two peaks of the melting temperature, corresponding to it is not homogeneity miscible between Ag particles and PLA matrices. Besides, we found that the contents of Ag nanoparticles within the PLA matrix slightly affect the thermal properties of nonwoven fiber mats in both

Tg and

Tm values, as shown in

Table 1. In addition, as expected, the degree of molecular order of the chains is higher in PLA composite nanofibers than in neat PLA nanofiber, as shown by the enthalpy values of 35.75, 33.58, 27.99, and 25.42 J/g for PLA/Ag-1, PLA/Ag-3, and PLA/Ag-5, respectively. This result suggested the crystallization of the polymer, resulting in increases in the degree of crystallinity of PLA nonwoven fiber mats, as illustrated in

Table 1. This result shows that the addition of silver particles acts as a nucleating agent, which increases the melting temperature and degree of crystallinity of PLA. This means that the silver particles influence intermolecular interactions or chain flexibility of PLA polymer chains. This result agrees with the results reported by Greco et al. [

63] and Oksiuta and coworker [

64].

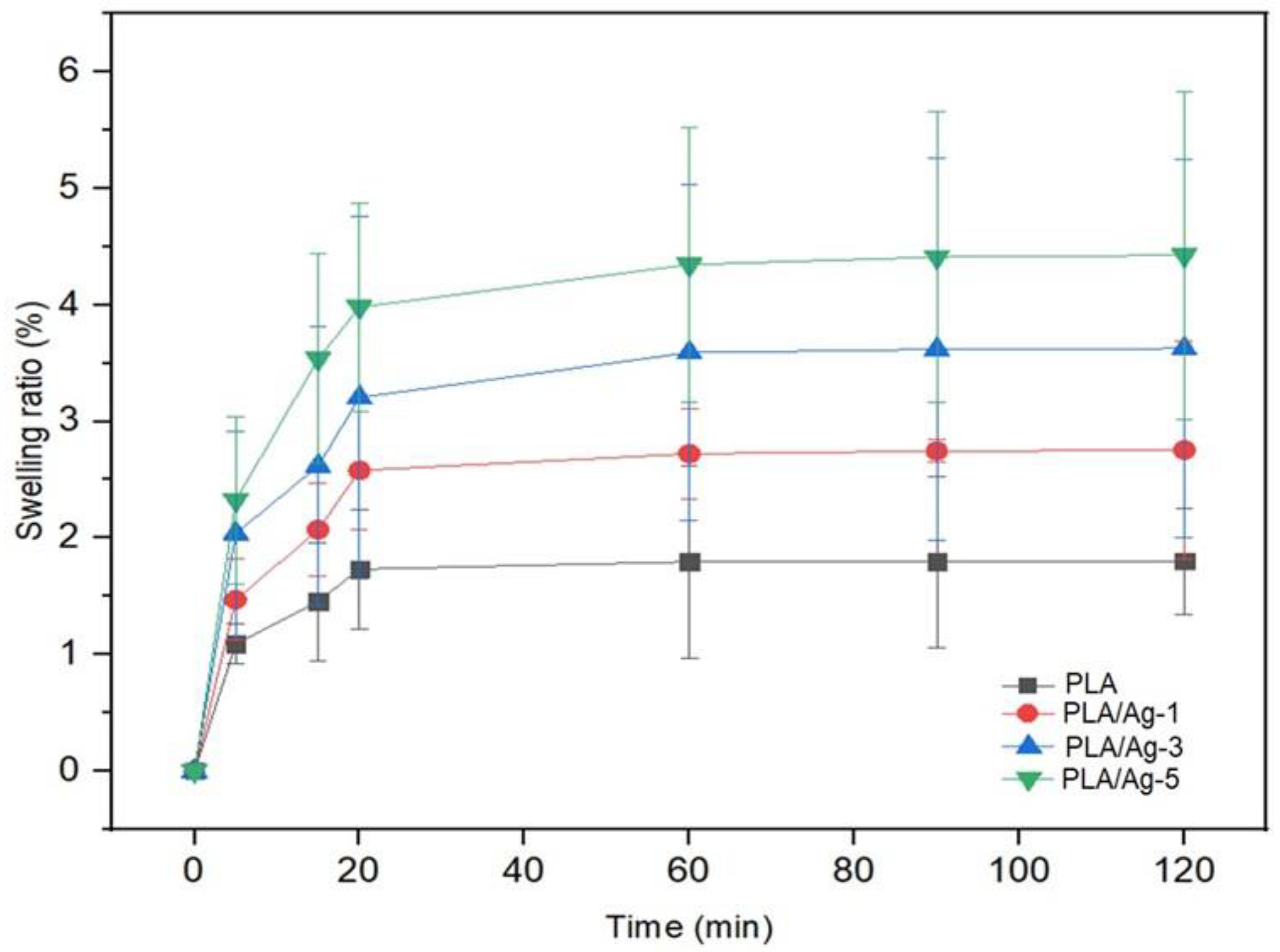

3.4. Water absorbency

In this investigation, the swelling ratios of nanofibers PLA and PLA composited with Ag nanoparticles at different concentrations are shown in

Figure 6. From this study, we found the nonwoven fiber mats exhibit an equilibrium absorbency of water in the range of 1-4%, depending on their compositions. These structured fiber mats did not absorb water so much due to the effect of the functionality of the chemical structure of PLA molecules; therefore, it shows highly hydrophobic properties. In

Figure 6, all nonwoven fiber mats exhibited a high initial water adsorption rate and then reached the equilibrium within 20 min. At the given contact time, the nonwoven composites PLA/Ag fiber mats showed higher values of swelling ratio than neat PLA. This is probably due to the miscibility between the silver particles and PLA matrices. The swelling ratio of nonwoven fiber mats increased when increasing the concentration of Ag nanoparticles, which resulted in more space or free volume on the interfacial of composites; hence, it illustrates a high swelling ratio when comparing the neat PLA nanofibers.

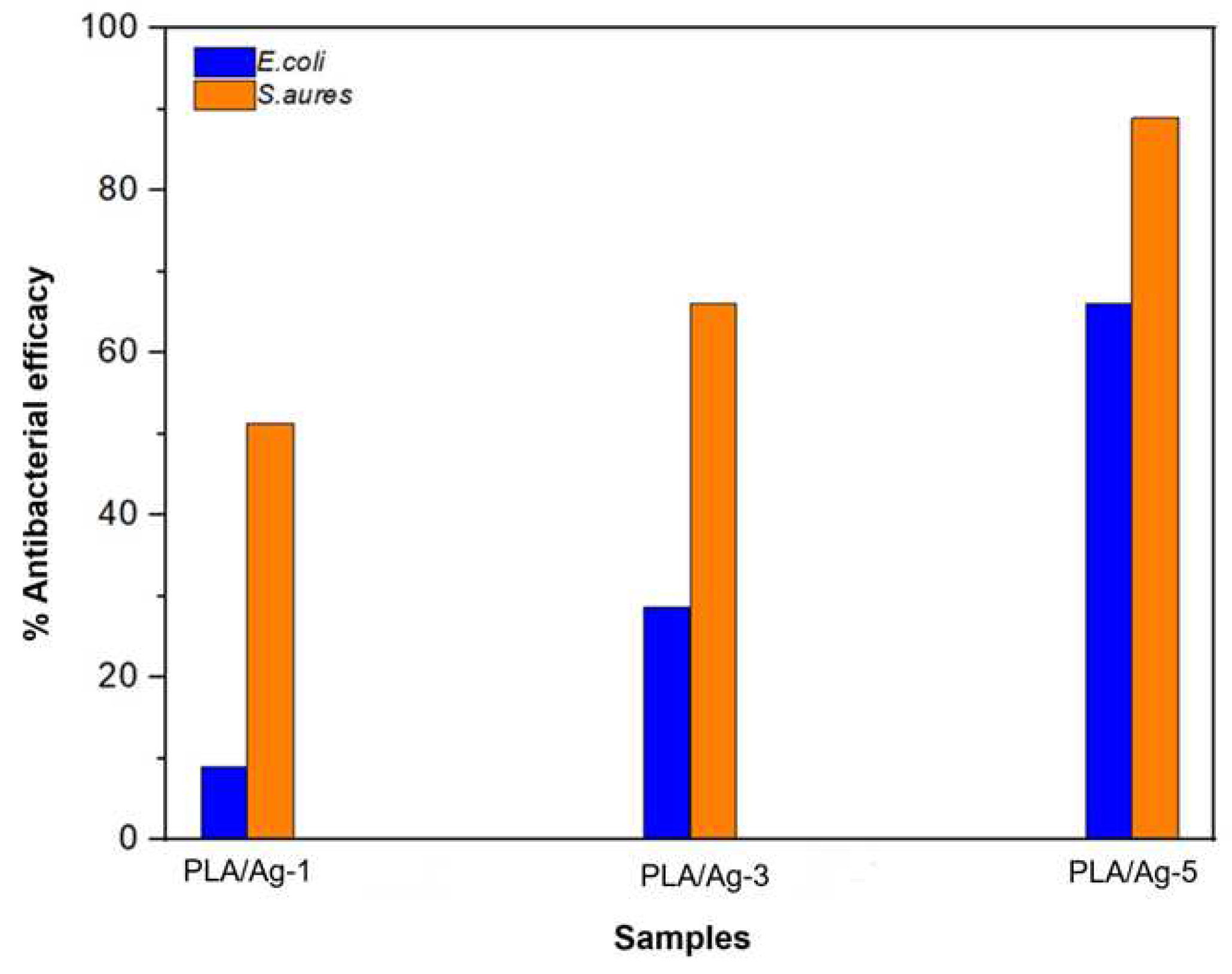

3.5. Antibacterial testing

Antibacterial activities of nonwoven fiber mats fabricated from neat PLA and PLA composited Ag nanoparticles at various concentration was evaluated against both Gram-positive (

S. aureus) and Gram-negative (

E. coli) bacteria by using disk diffusion susceptibility and plate colonies count methods. Our results demonstrated that no antibacterial activity was detected for neat PLA electrospun fiber mats, which were used as control materials, as illustrated in

Figure 7. In contrast, the antibacterial efficacy of both

S. aureus and

E. coli of the PLA composite nanofiber mats gradually increased with an increase in the amounts of Ag nanoparticles, as can be seen in

Figure 7. Besides, the size of inhibition zones also depends on the type of bacterial strain. In this study, all the obtained nonwoven fiber mats against

S. aureus bacteria were higher than

E. coli bacteria. This is probably due to the difference in the bacterial structure characteristics, resulting in the difference in the sensitivity and efficacy of antibacterial activity, as well as in agreement with those of the available scientific literature [

65,

66,

67].

More precisely, the quantitative analysis of electrospun fiber mats' antibacterial activities is demonstrated in

Figure 8. The results show that the PLA/Ag exhibits a significant increase in the antibacterial properties when added more amount of Ag nanoparticle content. Bacteria and culture media with neat PLA nanofiber mats were used as a control. The number of colonies counted after sampling the bacteria found in different samples, as depicted in

Table 2. PLA/Ag-5 nanofiber mats exhibited the highest antibacterial efficacies, both in

S. aureus and

E. coli, among three of the obtained composite nonwoven fiber mats.

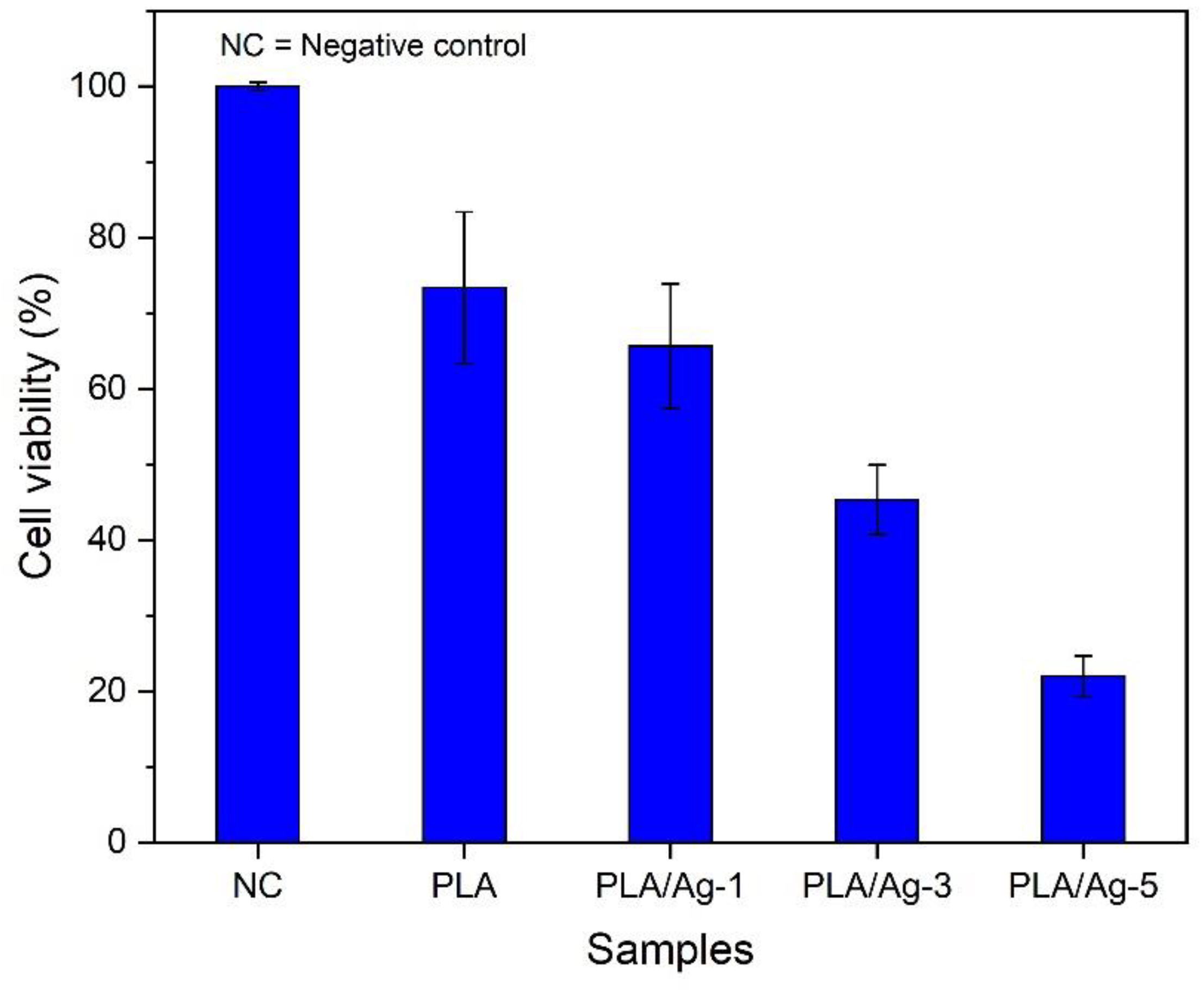

One of the essential characteristics of wound dressing is the growth and differentiation of cells in the wound site. Thus, to determine the cytotoxicity of the obtained nonwoven fiber mats to fibroblasts, MTT assays were carried out to investigate the cell viability. The MTT assay is a standard for testing that has been reported [

68]. The results showed that all fabricated nonwoven fiber mats have affected cell viability. In particular, the PLA/Ag electrospun fiber mats exhibited a significant influence on the amount of survival cells. In addition, the cell viability gradually decreased when increases in the Ag nanoparticles within PLA matrices, as represented in

Figure 9. The percentage of viable cells showed approximately 73.41±10.02, 63.69±8.20, 35.36±4.61, and 21.98±2.70 for nonwoven fiber mats prepared from PLA, PLA/Ag-1, PLA/Ag-3, and PLA/Ag-5, respectively. This result indicates that Ag nanoparticles have much effect on the survival of the cells. This study concurred with the findings of research that showed Ag nanoparticle concentrations have a direct inhibitory effect on cell growth.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully designed and prepared the antibacterial nonwoven fiber mats of PLA and PLA hybridized with Ag nanoparticles, smoothly and uniformly without any beads, via electrospinning technique. The results showed that the average diameters of the PLA nanofibers containing the Ag nanoparticles were larger than those without those particles. Besides, this diameter size is proportionally the amount of Ag nanoparticle contents. Additionally, the contents of Ag nanoparticles incorporated within the PLA-matrix show insignificant effect on the thermal properties of the nonwoven fiber mats. The crystallinity of the nonwoven fiber mats from PLA composited with Ag nanoparticles was a bit higher than those fiber mats the neat PLA. FTIR and EDS spectra indicated that Ag nanoparticles were merely incorporated in the PLA matrices without any chemical bonding between the particles of silver and the PLA chains. Accordingly, the antibacterial activities results revealed a most substantial growth inhibitory effect in the short term of the PLA/Ag-5, concerning the Ag nanoparticles concentration, against both S. aureus and E. coli, with a more pronounced action towards the Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative bacteria. In addition, all produced nonwoven fiber mats would be induced a reduction in cell viability for the L929 fibroblast cell line in the cell toxicity study. Overall, we suggest that the nonwoven fiber mats made here showed excellent morphological and thermal properties as well as antibacterial efficacy; moreover, the possibility of modifying functionalities of the materials can be adjusted the ratio between PLA and Ag nanoparticles for potential use in biomedical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J., C.-F.H., and A.P.; methodology and investigation, K.S., V.K., N.S. and J.S.; physical tests and analysis, N.S., K.S., R.M., A.T., and T.J.; Writing - Original Draft, T.J., R.M., and C.-F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute, KURDI, Fundamental Fund (FF, KU) 13.66. This research was also supported by the two-institution co-research project provided by Kasetsart University and National Chung Hsing University.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply acknowledged to the Faculty of Science at Sriracha, Kasetsart University and Faculty of Medical Science, Naresuan University for providing convenient laboratories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there have been no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence this work reported in this paper.

References

- Reddy, V.S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ye, Z.; Roy, K.; Chinnappan, A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Liu, W.; Ghosh, R. A. Review on electrospun nanofibers based advanced applications: From health care to energy devices. Polymers 2021, 13, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbiah, T.; Bhat, G.S.; Tock, R.W.; Parameswaran, S.; Ramkumar, S.S. Electrospinning of nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 96, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abduljabbar, A.; Farooq, I. Electrospun polymer nanofibers: Processing, properties, and applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, L.; Osemwegie, O.; Ramkumar, S.S. Functional nanofibers and their applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 5439–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.; Blachowicz, T.; Sabantina, L. Electrospun nanofiber mats for filtering applications-technology, structure and materials. Polymers 2021, 13, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinthaginjala, J.K.; Seshan, K.; Lefferts, L. Preparation and application of carbon-nanofiber based microstructured materials as catalyst supports. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 3968–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Kundu, S.C. Electrospinning: A fascinating fiber fabrication technique. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reneker, D.H.; Yarin, A.L. Electrospinning jets and polymer nanofibers. Polymer 2008, 49, 2387–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.E.; Inai, R.; Ramakrishna, S. Technological advances in electrospinning of nanofibers. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2011, 12, 013002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Facile and ultrasensitive sensors based on electrospinning-netting nanofibers/net. Nanosci. Technol. 2015, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Duzyer, S.; Hockenberger, A.; Zussman, E. Characterization of solvent-spun polyester nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 120, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.J.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Electrospinning process and structure relationship of biobased poly(butylene succinate) for nanoporous fibers. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5547–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Yao, H.; Luo, J.; Li, Z.; Wei, J. Functionalization of electrospun nanofiber for bone tissue engineering. Polymers 2022, 14, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.H.; Cheng, C.C.; Huang, C.F.; Chen, J.K. Using coaxial electrospinning to fabricate core/shell-structured polyacrylonitrile–polybenzoxazine fibers as nonfouling membranes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 58760–58771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, K.; Afifi, A.M.; Jahangirian, H.; Webster, T.J. Biomedical applications of chitosan electrospun nanofibers as a green polymer-Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Kuang, H.; You, Z.; Morsi, Y.; Mo, X. Electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering with drug loading and release. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Z.; Yu, D.G.; Wang, K. Electrospun nanofiber membranes for air filtration: A review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, V.V.; Wang, L.J.; Padhye, R. Electrospun nanofibre materials to filter air pollutants-A review. J. Ind. Text. 2018, 47, 2253–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Cui, J.; Qu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, R.; Ma, W.; Huang, C. Multistructured electrospun nanofibers for air filtration: A review. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 23293–23313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, F.; Tarascon, J.M.; Kim, J.K. Recent advances in electrospun carbon nanofibers and their application in electrochemical energy storage. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 76, 319–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Lee, J.S. Electrospinning based carbon nanofibers for energy and sensor applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardick. O.; Dods, S.; Stevens, B.; Bracewell, D.G. Nanofiber adsorbents for high productivity continuous downstream processing. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 213, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlayıcı, Ş.; Avcı, A.; Pehlivan, E. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofiber (nylon 6,6/graphene oxide) for removal of Cr (VI): synthesis and adsorption studies. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaghraby, N.A.; Omer, A.M.; Kenawy, E.R.; Gaber, M.; Nemr, A.E. Electrospun composites nanofibers from cellulose acetate/carbon black as efficient adsorbents for heavy and light machine oil from aquatic environment. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2022, 19, 3013–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhaj, S.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Nanofibres in drug delivery applications. Fibers 2023, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, A.; Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z. Electrospun nanofibers for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, D.; Lu, X.; Jing, X.; Huang, Y. Biphasic drug release from electrospun polyblend nanofibers for optimized local cancer treatment. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, W.; Tan, G. Stimuli-responsive electrospun nanofibers for drug delivery, cancer therapy, wound dressing, and tissue engineering. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamnongkan, T.; Sukumaran, S.K.; Sugimoto, M.; Hara, T.; Takatsuka, Y.; Koyama, K. Towards novel wound dressings: Antibacterial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles and electrospun fiber mats of zinc oxide nanoparticle/poly (vinyl alcohol) hybrids. J. Polym. Eng. 2015, 35, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, I.; Czapka, T. Electrospun polymer nanofibers with antimicrobial activity. Polymers 2022, 14, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.M.; Hassanin, A.H.; El-kaliuoby, M.I.; Omran, N.; Gamal, M.; El-Khatib, A.M.; Kandas, I.; Shehata, N. Innovative antibacterial electrospun nanofibers mats depending on piezoelectric generation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, S.A.; Taha, A.A.; Khozemy, E.E.; EL-Moslamy, S.H.; Kamoun, E.A. Electrospun zinc-based metal organic framework loaded-PVA/chitosan/hyaluronic acid interfaces in antimicrobial composite nanofibers scaffold for bone regeneration applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 76, 103823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Duan, X.P.; Li, Y.M.; Yang, D.P.; Long, Y.Z. Electrospun nanofibers for wound healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 76, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, R.; Dhand, C.; Mayandi, V.; Leung, C.M.; Ezhilarasu, H.; Karuppannan, S.K.; Prasannan, P.; Ong, S.T.; Sunderasan, N.; Kaliappan, I.; Kamruddin, M.; Barathi, V.A.; Verma, N.K.; Ramakrishna, S.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Arunachalam, K.D. Core-shell structured antimicrobial nanofiber dressings containing herbal extract and antibiotics combination for the prevention of biofilms and promotion of cutaneous wound healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 24356–24369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Saito, Y.; Ullah, S.; Haider, K.; Nawaz, H.; Duy-Nam, P.; Kharaghani, D.; Kim, I.S. Bioactive Sambong oil-loaded electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers: Preparation, characterization, and in-vitro biocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 166, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemikia, S.; Farhangpazhouh, F.; Parsa, M.; Hasan, M.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Hamidi, M. Fabrication of ciprofloxacin-loaded chitosan/polyethylene oxide/silica nanofibers for wound dressing application: In vitro and in vivo evaluations. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 597, 120313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, A.E.A.; dos Santos, F.V.; Freitas, K.M.; Pimenta, L.P.S.; Andrade, L.D.O.; Marinho, T.A.; de Avelar, G.F.; da Silva, A.B.; Ferreira, R.V. Cellulose acetate nanofibers loaded with crude annatto extract: Preparation, characterization, and in vivo evaluation for potential wound healing applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 118, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodeji, O.J.; Khyum, M.M.O.; Afolabi, R.T.; Smith, E.; Kendall, R.; Ramkumar, S. Preparation of surface-functionalized electrospun PVA nanowebs for potential remedy for SARS-CoV-2. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Li, X.; Miao, M.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. Fabrication and properties of electrospun and electrosprayed polyethylene glycol/polylactic acid (PEG/PLA) films. Coatings 2021, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, M.N.; Metwally, B.S.; Mubarak, M.F; Ahmed, H.A.; Moghny, T.A.; Zayed, A.M. Fabrication of electrospun polyamide–weathered basalt nano-composite as a non-conventional membrane for basic and acid dye removal. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 8511–8533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.-G. Processes of electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride-based nanofibers, their piezoelectric properties, and several fantastic applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azari, A.; Golchin, A.; Mahmoodinia, M.M.; Mansouri, F.; Ardeshirylajimi, A. Electrospun polycaprolactone nanofibers: Current research and applications in biomedical application. Adv Pharm Bull. 2022, 12, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Chang, C.C.; Halada, G.; Cuiffo, M.A.; Xue, Y.; Zuo, X.; Pack, S.; Zhang, L.; He, S.; Weil, E.; Rafailovich, M.H. Engineering flame retardant biodegradable polymer nanocomposites and their application in 3D printing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 137, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Azimi, B.; Ismaeilimoghadam, S.; Danti, S. Poly(lactic acid)-based electrospun fibrous structures for biomedical applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, F.S.; Khoddami, A.; Avinc, O. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) nanofibers for bone tissue engineering. J. Text. Polym. 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.; Daniels, R. Preparation and characterization of electrospun polylactic acid (PLA) fiber loaded with birch bark triterpene extract for wound dressing. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2021, 22, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatahian, R.; Mirjalili, M.; Khajavi, R.; Rahimi, M.K.; Nasirizadeh, N. Effect of electrospinning parameters on production of polyvinyl alcohol/polylactic acid nanofiber using a mutual solvent. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2021, 29, S844–S856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamnongkan, T.; Jaroensuk, O.; Khankhuean, A.; Laobuthee, A.; Srisawat, N.; Pangon, A.; Mongkholrattanasit, R.; Phuengphai, P.; Wattanakornsiri, A.; Huang, C.F. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Mechanical, Thermal, and Antibacterial Properties of PLA/ZnO Nanoflower Biocomposite Filaments for 3D Printing Application. Polymers 2022, 14, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alippilakkotte, S.; Kumar, S.; Sreejith, L. Fabrication of PLA/Ag nanofibers by green synthesis method using Momordica charantia fruit extract for wound dressing applications. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 529, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaris, V.; San Félix García-Obregón, I.; López, D.; Peponi, L. Fabrication of PLA-based electrospun nanofibers reinforced with ZnO nanoparticles and in vitro degradation study. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, F.; Ahmed, S.; Liu, Y. Physico-mechanical and antibacterial properties of PLA/TiO2 composite materials synthesized via electrospinning and solution casting processes. Coatings 2019, 9, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.; Atassi, Y. TiO2/PLLA electrospun nanofibers membranes for efficient removal of methylene blue using sunlight. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu, D.M.; Frone, A.N.; Chiulan, I.; Gabor, R.A.; Spataru, I.C.; Căşărică, A. Biocomposites from polylactic 401 acid and bacterial cellulose nanofibers obtained by mechanical treatment. BioResources 2017, 12, 662–672.402. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, L.; Lee, S.; Mei, C.; Xu, X.; Wu, Q. The influence of grafted cellulose nanofibers and postex-403 trusion annealing treatment on selected properties of poly(lactic acid) filaments for 3D printing. J. Polym. Sci. Part 404 B Polym. Phys. 2017, 55, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamnongkan, T.; Mongkholrattanasit, R.; Wattanakornsiri, A.; Wachirawongsakorn, P.; Takatsuka, Y.; Hara, T. Green adsorbents for copper (II) biosorption from waste aqueous solution based on hydrogel-beads of biomaterials. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 35, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamnongkan, T.; Sukumaran, S.K.; Sugimoto, M.; Hara, T.; Takatsuka, Y.; Koyama, K. Towards novel wound dressings: Antibacterial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles and electrospun fiber mats of zinc oxide nanoparticle/poly (vinyl alcohol) hybrids. J. Polym. Eng. 2015, 35, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Semnani Rahbar, R.; Saadatmand, M.M.; Barani, H. Physical and morphological characterisation of poly(L-lactide) acid-based electrospun fibrous structures: Tunning solution properties. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2018, 47, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Gharehaghaji, A.A.; Criscenti, G.; Moroni, L.; Dijkstra, P.J. The influence of process parameters on the properties of electrospun PLLA yarns studied by the response surface methodology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Jiang, H.; Zimba, B.L.; Chen, L.; Wan, J.; Wu, Q. Preparation of poly(lactic acid)/graphene oxide nanofiber membranes with different structures by electrospinning for drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 16619–16625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Zhao, R.; Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Ning, X. Bicomponent PLA nanofiber nonwovens as highly efficient filtration media for particulate pollutants and pathogens. Membranes 2021, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavoukkarasu, M.; Balaji, U.; Behera, S.; Panda, P.K.; Mishra, B.K. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticle from leaf extract of Desmodium gangeticum (L.) DC. and its biomedical potential. Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 116, 424–427. [Google Scholar]

- Shume, W.M. , Murthy H.C.A., Zereffa E.A. A Review on synthesis and characterization of Ag2O nanoparticles for photocatalytic applications. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Ferrari, F. Thermal behavior of PLA plasticized by commercial and cardanol-derived plasticizers and 416 the effect on the mechanical properties. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 146, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksiuta, Z.; Jalbrzykowski, M.; Mystkowska, J.; Romanczuk, E.; Osiecki, T. Mechanical and thermal properties of polylactide (PLA) composites modified with Mg, Fe, and polyethylene (PE) additives. Polymers 2020, 12, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alinezhad Sardareh, E.; Shahzeidi, M.; Salmanifard Ardestani, M.T.; Mousavi-Khattat, M.; Zarepour, A.; Zarrabi, A. Antimicrobial activity of blow spun PLA/gelatin nanofibers containing green synthesized silver nanoparticles against wound infection-causing bacteria. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, H.H.; Kim, B.H.; Yang, K.S.; Rhee, J.I. Synthesis and antibacterial performance of size-tunable silver nanoparticles with electrospun nanofiber composites. Synth. Met. 2011, 161, 2124–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiao, D.; Zhang, W.; Ren, K.; Qiu, L.; Tian, C.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Han, X. Antibacterial and antihyperplasia polylactic acid/silver nanoparticles nanofiber membrane-coated airway stent for tracheal stenosis. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 206, 111949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaee-Ardakani, M.R.; Hatamian-Zarmi, A.; Sadat, S.M.; Mokhtari-Hosseini, Z.B.; Ebrahimi-Hosseinzadeh, B.; Kooshki, H.; Rashidiani, J. In situ preparation of PVA/schizophyllan-AgNPs nanofiber as potential of wound healing: Characterization and cytotoxicity. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).