Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

14 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

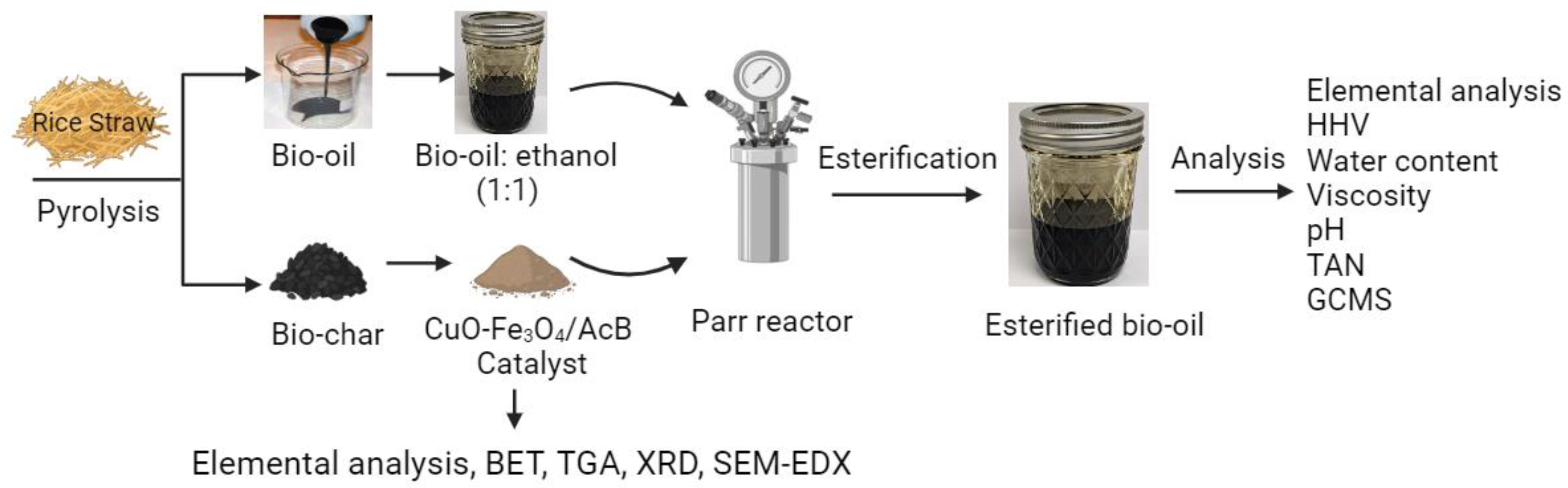

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Pyrolysis of Rice Straw

2.3. Preparation of biochar-based catalysts

2.4. Preparation of CuO-Fe3O4/AcB

2.5. Catalyst Characterization

2.6. Bio-oil esterification process

2.7. Physical and chemical characterization of raw and esterified bio-oil

3. Results

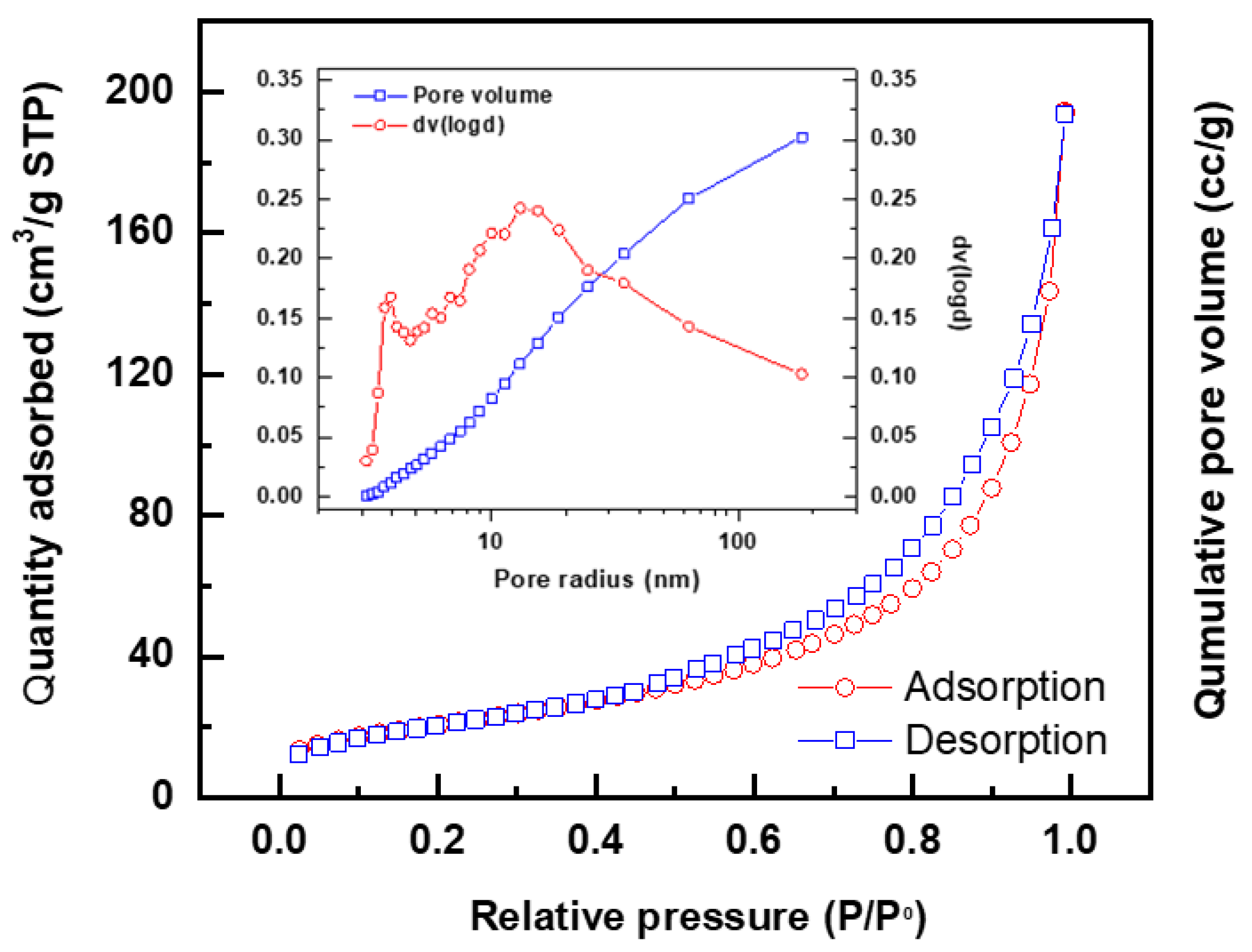

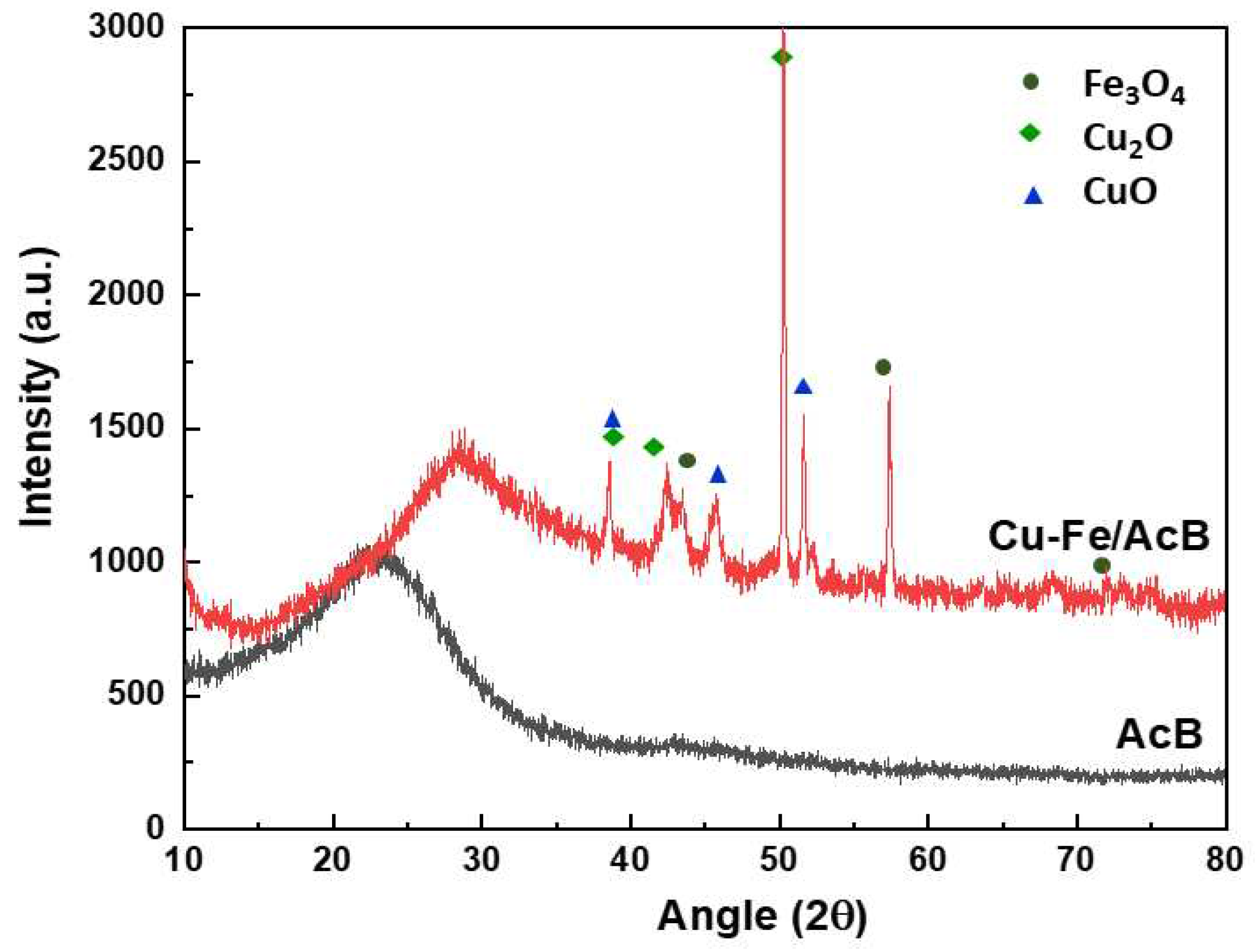

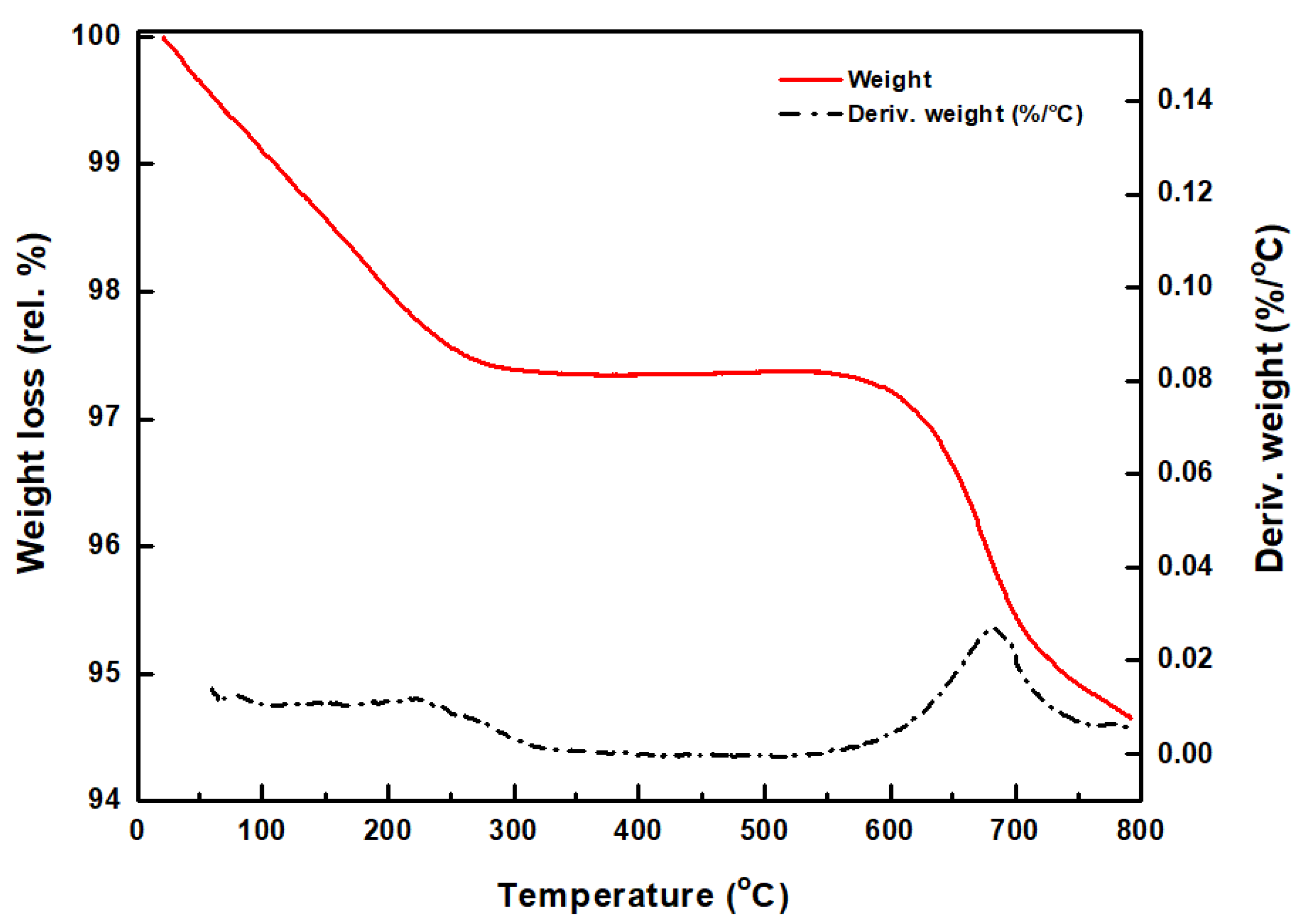

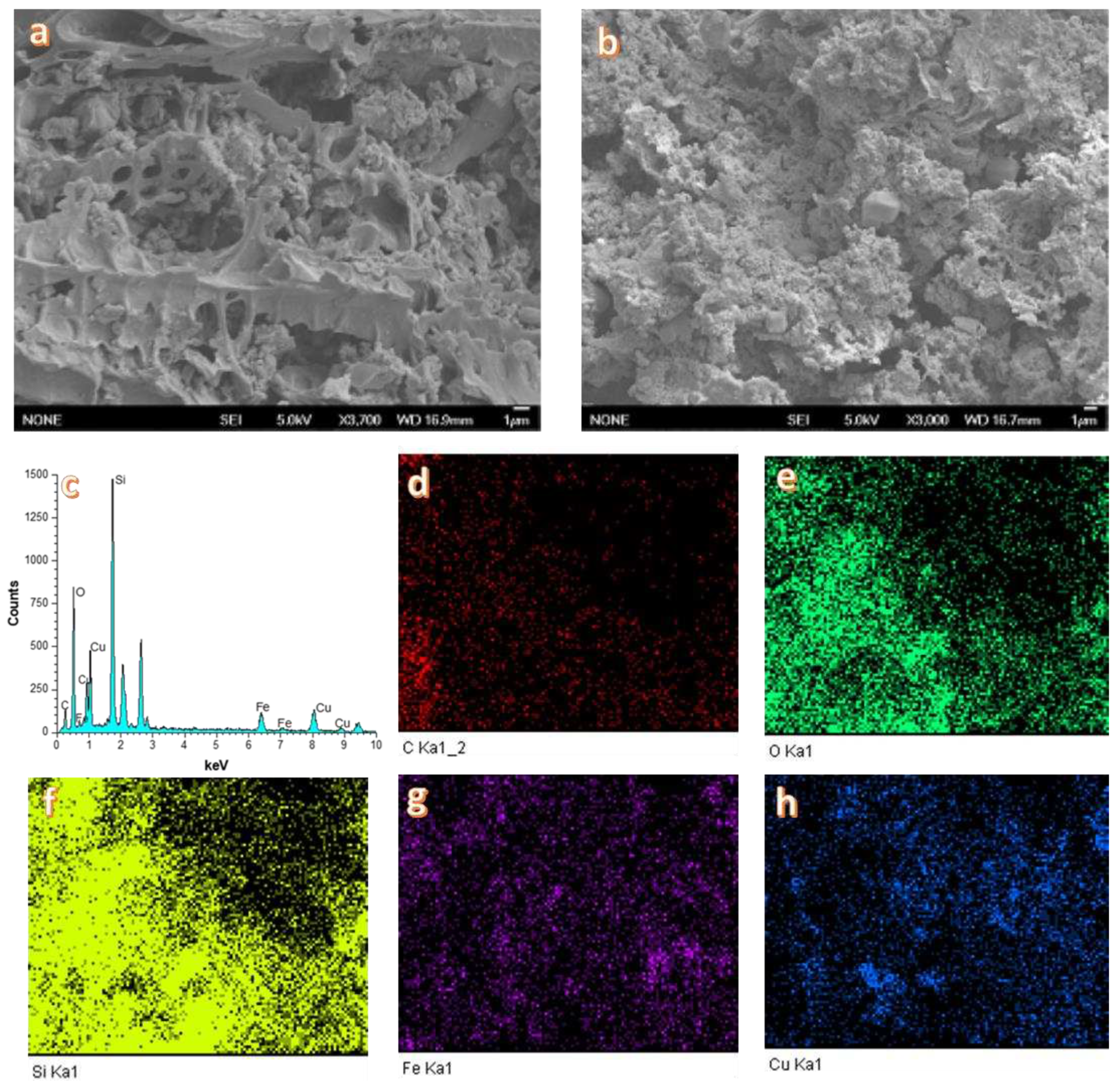

3.1. Catalyst Characterization

3.2. Product yields, elemental analysis and HHV

3.3. Physical chractarization of raw and esterified upgraded bio-oils

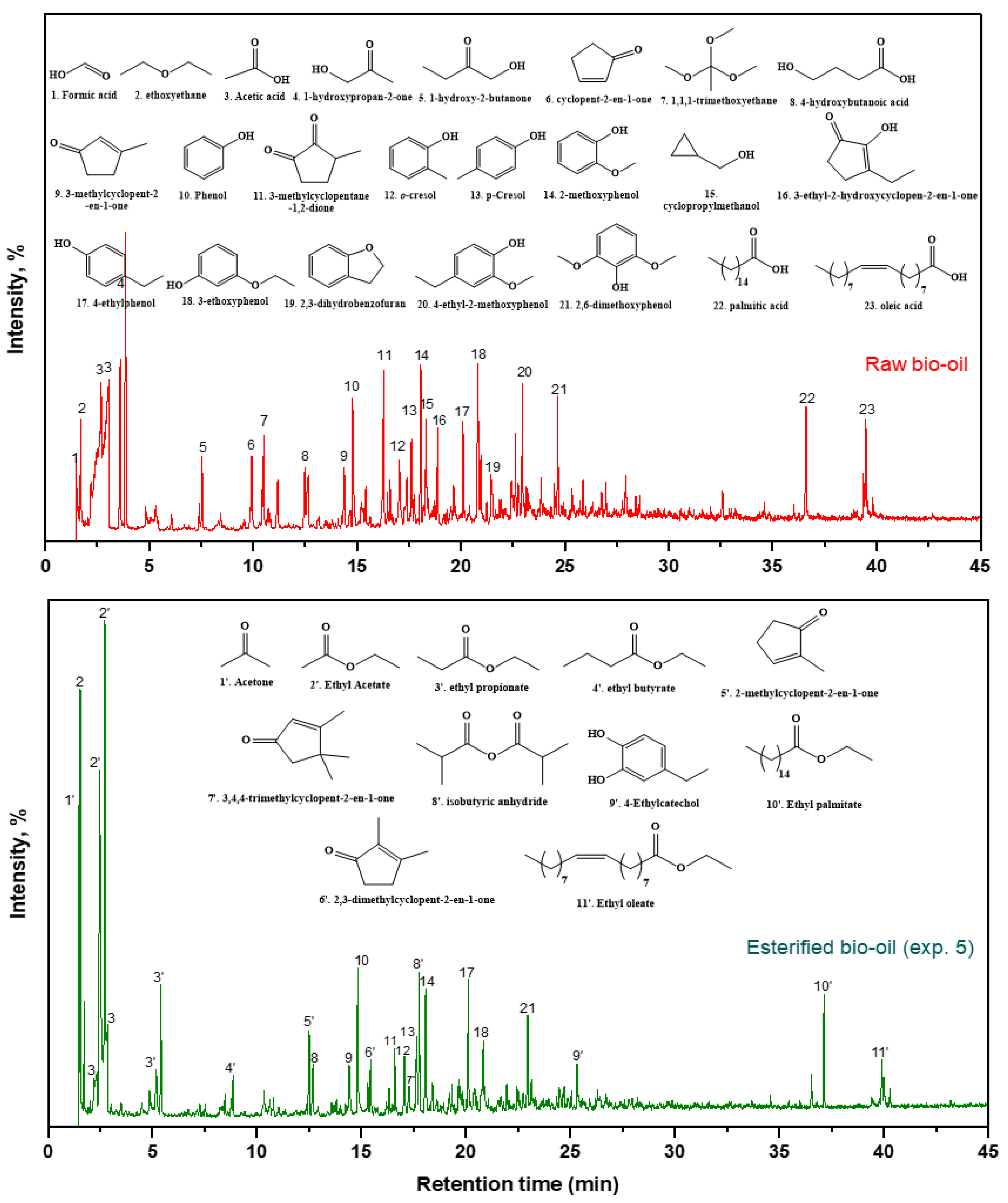

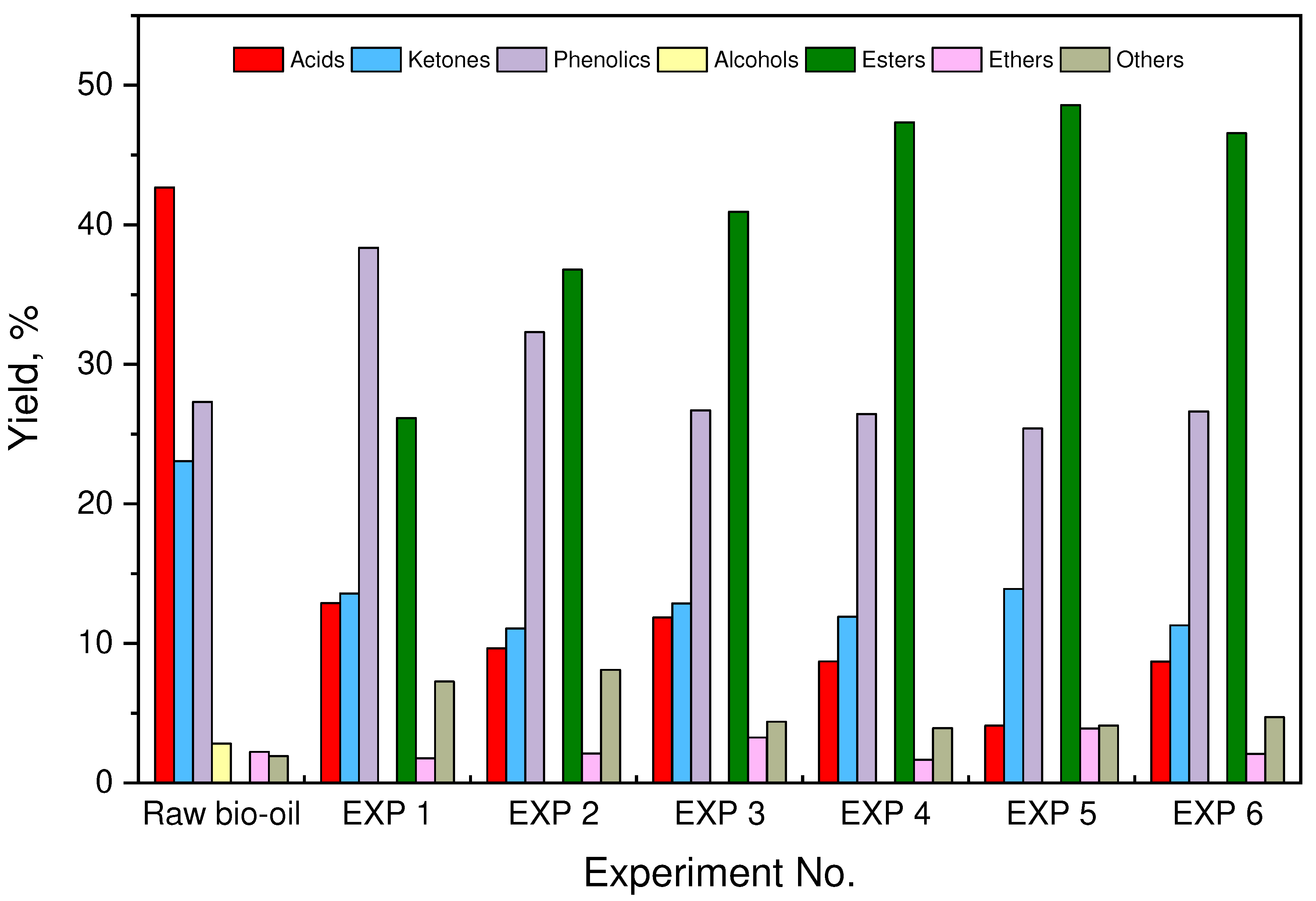

3.4. Chemical chractarization of raw and esterified upgraded bio-oils

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, B.; Bai, D. The path to carbon neutrality in China: A paradigm shift in fossil resource utilization. Resources Chemicals and Materials 2022, 1, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoon, A.; Haleem, A.; Bahl, S.; Javaid, M.; Bala Garg, S.; Chandmal Sharma, R.; Garg, J. Environmental impact of energy production and extraction of materials - a review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 57, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U.; Steele, P.H. Pyrolysis of wood /biomass for Bio-oil. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2017, 62, 848–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, S.M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Life cycle assessment of rice straw-based power generation in Malaysia. Energy 2014, 70, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, P.K.; Shadangi, K.P.; Srivastava, R.K. Chapter 5 - Agricultural waste to fuels and chemicals. 2023, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Hamidin, N. Bio-oil Product from Non-catalytic and Catalytic Pyrolysis of Rice Straw. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2013, 7, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Oasmaa, A.; Lehto, J.; Solantausta, Y.; Kallio, S. Historical Review on VTT Fast Pyrolysis Bio-oil Production and Upgrading. Energy and Fuels 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernik, S.; Bridgwater, A.V. Overview of applications of biomass fast pyrolysis oil. Energy and Fuels 2004, 18, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Kumar, A. Production of renewable diesel through the hydroprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass-derived bio-oil: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 58, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenbacher, A.; Fennell, P.; Jensen, A.D. A Review of Recent Research on Catalytic Biomass Pyrolysis and Low-Pressure Hydropyrolysis. Energy and Fuels 2021, 35, 18333–18369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, S.; Choi, D.; Choi, I.-G.; Choi, J.W. The effect of storage duration on bio-oil properties. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2012, 95, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneechakr, P.; Karnjanakom, S. Improving the Bio-Oil Quality via Effective Pyrolysis/Deoxygenation of Palm Kernel Cake over a Metal (Cu, Ni, or Fe)-Doped Carbon Catalyst. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 20006–20014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, E.B.M.; Steele, P.H.; Ingram, L. Characterization of fast pyrolysis bio-oils produced from pretreated pine wood. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2009, 154, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmi, W.W.; Park, J.-Y.; Amini, G.; Lee, I.-G. Upgrading of esterified bio-oil from waste coffee grounds over MgNiMo/activated charcoal in supercritical ethanol. Fuel Processing Technology 2023, 250, 107915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, J.R.; Miller, J.; Geller, D.P.; Locklin, J.; Keith, L.H.; Johnson, T. Catalytic esterification of fatty acids using solid acid catalysts generated from biochar and activated carbon. Catalysis Today 2012, 190, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.R.C.; dos Santos, I.A.; Arcanjo, M.R.A.; Cavalcante, C.L.; de Luna, F.M.T.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Vieira, R.S. Production of Jet Biofuels by Catalytic Hydroprocessing of Esters and Fatty Acids: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Lee, I.-G.; Park, J.-Y.; Lee, K.-Y. Efficient upgrading of pyrolysis bio-oil over Ni-based catalysts in supercritical ethanol. Fuel 2019, 241, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaghat, H.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, I.-G.; Jae, J.; Jung, S.-C.; Park, Y.-K. Catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of crude bio-oil in supercritical methanol using supported nickel catalysts. Renewable Energy 2019, 144, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, H.A.; Nizamuddin, S.; Siddiqui, M.T.H.; Riaz, S.; Konstas, K.; Mubarak, N.M.; Srinivasan, M.P.; Griffin, G.J. Catalytic upgradation of bio-oil over metal supported activated carbon catalysts in sub-supercritical ethanol. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, G.; Sanna, A.; Paone, E.; Catizzone, E. Recent catalytic advances in hydrotreatment processes of pyrolysis bio-oil. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Jeon, W.; Lee, J.-H.; Nam, B.; Lee, I.-G. Effects of supercritical fluids in catalytic upgrading of biomass pyrolysis oil. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 377, 120312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Luo, Z.; Yu, C.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Upgrading of bio-oil in supercritical ethanol: Catalysts screening, solvent recovery and catalyst stability study. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2014, 95, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, K. Supercritical fluids technology for clean biofuel production. Progress in Natural Science 2009, 19, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, P.; Li, F.; Ye, J.; Zhou, M. Hydrotreatment of vegetable oil for green diesel over activated carbon supported molybdenum carbide catalyst. Fuel 2018, 216, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Hasan, M.D.M.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.-Z. Reaction behaviour of light and heavy components of bio-oil in methanol and in water. Fuel 2018, 232, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gunawan, R.; Mourant, D.; Hasan, M.D.M.; Wu, L.; Song, Y.; Lievens, C.; Li, C.-Z. Upgrading of bio-oil via acid-catalyzed reactions in alcohols—A mini review. Fuel processing technology 2017, 155, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiyanti, A.R.; Gutierrez, A.; Honkela, M.L.; Krause, A.O.I.; Heeres, H.J. Hydrotreatment of wood-based pyrolysis oil using zirconia-supported mono-and bimetallic (Pt, Pd, Rh) catalysts. Applied Catalysis A: General 2011, 407, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.; Ji, Y.; Leong, G.J.; Kovach, N.C.; Trewyn, B.G.; Richards, R.M. Hybrid mesoporous silica/noble-metal nanoparticle materials—synthesis and catalytic applications. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2018, 1, 4386–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiabudi, H.; Aziz, M.; Abdullah, S.; Teh, L.; Jusoh, R. Hydrogen production from catalytic steam reforming of biomass pyrolysis oil or bio-oil derivatives: A review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 18376–18397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.-Y.; Cao, J.-P.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, T.-L.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y.-P.; Wei, X.-Y. Catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapors from lignite over mono/bimetal-loaded mesoporous HZSM-5. Fuel 2018, 218, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, R.; Pawelec, B.; Castaño, P.; Álvarez-Galván, M.C.; Loricera, C.V.; Fierro, J.L.G. Upgrading of bio-liquids on different mesoporous silica-supported CoMo catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2009, 92, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Q.; Lei, H.; Zacher, A.H.; Wang, L.; Ren, S.; Liang, J.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A review of catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived phenols from biomass pyrolysis. Bioresource Technology 2012, 124, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewmeesri, R.; Nonkumwong, J.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Laosiripojana, N.; Faungnawakij, K. Deoxygenations of palm oil-derived methyl esters over mono- And bimetallic NiCo catalysts. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Rahman, M.M.; Sarker, M.; Chai, M.; Li, C.; Cai, J. A review on the catalytic pyrolysis of biomass for the bio-oil production with ZSM-5: Focus on structure. Fuel processing technology 2020, 199, 106301. [Google Scholar]

- Sihombing, J.L.; Herlinawati, H.; Pulungan, A.N.; Simatupang, L.; Rahayu, R.; Wibowo, A.A. Effective hydrodeoxygenation bio-oil via natural zeolite supported transition metal oxide catalyst. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2023, 16, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, C.; Akutsu, R.; Yang, K.; Zayan, N.M.; Dou, J.; Liu, J.; Bose, A.; Brody, L.; Lamb, H.H.; Li, F. Hydrogenation of bio-oil-derived oxygenates at ambient conditions via a two-step redox cycle. Cell Reports Physical Science 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ling, H.; Wei, D.; Wei, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhao, J. Microwave catalytic co-pyrolysis of chlorella vulgaris and oily sludge by nickel-X (X= Cu, Fe) supported on activated carbon: Characteristic and bio-oil analysis. Journal of the Energy Institute 2023, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Ge, Y.; Li, Z. Efficient depolymerization of alkali lignin to monophenols using one-step synthesized Cu–Ni bimetallic catalysts inlaid in homologous biochar. Biomass and Bioenergy 2023, 175, 106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Han, X.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, C.C. Hydrodeoxygenation of Pyrolysis Oil in Supercritical Ethanol with Formic Acid as an In Situ Hydrogen Source over NiMoW Catalysts Supported on Different Materials. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Tie, B.; Lei, M.; Wei, X.; Peng, O.; Du, H. Silicate-modified oiltea camellia shell-derived biochar: A novel and cost-effective sorbent for cadmium removal. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a Catalyst. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 77, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Tamai, K.; Ichii, M.; Wu, G.F. A rice mutant defective in Si uptake. Plant Physiology 2002, 130, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejati, B.; Adami, P.; Bozorg, A.; Tavasoli, A.; Mirzahosseini, A.H. Catalytic pyrolysis and bio-products upgrading derived from Chlorella vulgaris over its biochar and activated biochar-supported Fe catalysts. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2020, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hassan, E.B.; Miao, P.; Xu, Q.; Steele, P.H. Effects of single-stage syngas hydrotreating on the physical and chemical properties of oxidized fractionated bio-oil. Fuel 2017, 209, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhao, N.; Tong, L.; Lv, Y. Structural and adsorption characteristics of potassium carbonate activated biochar. RSC Advances 2018, 8, 21012–21019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Leahy, J.J.; Kwapinski, W. Catalytically upgrading bio-oil via esterification. Energy and Fuels 2015, 29, 3691–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.Q.; Jiang, H.F.; Lin, C.; Liao, S.J. Shape- and size-controlled electrochemical synthesis of cupric oxide nanocrystals. Journal of Crystal Growth 2007, 303, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrappa, K.G.; Venkatesha, T.V. Generation of nanostructured CuO by electrochemical method and its Zn–Ni–CuO composite thin films for corrosion protection. Materials and corrosion 2013, 64, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, I.; Jackson, M.A.; Hassan, E.B. Hydrogen-Free Catalytic Reduction of Biomass-Derived 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-Bis(hydroxymethyl)furan Using Copper–Iron Oxides Bimetallic Nanocatalyst. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachos-Perez, D.; Martins-Vieira, J.C.; Missau, J.; Anshu, K.; Siakpebru, O.K.; Thengane, S.K.; Morais, A.R.C.; Tanabe, E.H.; Bertuol, D.A. Review on Biomass Pyrolysis with a Focus on Bio-Oil Upgrading Techniques. Analytica 2023, 4, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, P.; Zhao, C. Stability evaluation of fast pyrolysis oil from rice straw. Chemical Engineering Science 2015, 135, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.; Alsamaq, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. Production of renewable fuels by blending bio-oil with alcohols and upgrading under supercritical conditions. Frontiers of Chemical Science and Engineering 2019, 13, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, H.A.; Nizamuddin, S.; Siddiqui, M.T.H.; Riaz, S.; Konstas, K.; Mubarak, N.; Srinivasan, M.; Griffin, G. Catalytic upgradation of bio-oil over metal supported activated carbon catalysts in sub-supercritical ethanol. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EXP. | Catalyst |

AcB (wt%) |

Cu and Fe (wt%) |

Cu (wt%) |

Fe (wt%) |

Cu: Fe ratio |

| 1 | AcB | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 2 | 1 | 80 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 1:1 |

| 3 | 2 | 80 | 20 | 13.33 | 6.66 | 2:1 |

| 4 | 3 | 80 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 3:1 |

| 5 | 4 | 90 | 10 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 3:1 |

| 6 | 5 | 70 | 30 | 22.5 | 7.5 | 3:1 |

|

EXP. No. |

Catalyst | BET Surface area (m2/g) |

Pore Volume (cc/g) |

Average pore diameter (nm) |

| 1 | AcB | 203.75 | 0.389 | 3.71 |

| 2 | 1 | 58.32 | 0.253 | 14.75 |

| 3 | 2 | 56.41 | 0.234 | 15.39 |

| 4 | 3 | 53.19 | 0.213 | 16.03 |

| 5 | 4 | 74.81 | 0.299 | 10.64 |

| 6 | 5 | 23.89 | 0.176 | 36.78 |

| EXP. No. |

Y (liquid) |

Y (solid) |

Y (gas) |

Elemental Analysis (wt.%) |

HHV (MJ/kg) |

|||

| C | H | N | O | |||||

| Raw bio-oil | - | - | - | 54.2 | 7.7 | 1.8 | 36.3 | 21.3 |

| 1 | 56.3 | 4.3 | 39.4 | 60.7 | 7.2 | 2.1 | 28.0 | 24.3 |

| 2 | 37.4 | 17.6 | 45.0 | 62.3 | 7.6 | 2.2 | 27.9 | 27.8 |

| 3 | 38.4 | 17.3 | 44.3 | 62.9 | 6.6 | 3.1 | 27.4 | 28.9 |

| 4 | 36.0 | 19.1 | 44.9 | 65.4 | 9.1 | 2.8 | 22.7 | 30.9 |

| 5 | 37.4 | 19.3 | 43.3 | 66.9 | 9.1 | 2.2 | 21.8 | 32.1 |

| 6 | 36.9 | 19.6 | 43.5 | 67.0 | 8.8 | 3.3 | 20.9 | 31.9 |

| EXP. No. |

Water content |

Viscosity at 40 °C Cst |

Density at 40 °C (g/cm3) | pH |

TAN (mg KOH/g) |

| Raw bio-oil | 38.5 | 1.88 | 0.92 | 4.3 | 83.9 |

| 1 | 35.2 | 1.78 | 0.87 | 4.6 | 75.7 |

| 2 | 34.4 | 1.68 | 0.84 | 4.8 | 74.5 |

| 3 | 34.0 | 1.75 | 0.84 | 4.8 | 72.6 |

| 4 | 33.9 | 1.79 | 0.85 | 4.9 | 70.8 |

| 5 | 32.1 | 1.63 | 0.78 | 5.6 | 60.3 |

| 6 | 32.7 | 1.77 | 0.86 | 5.1 | 71.1 |

| RT (min) | Compound Name | (Area %) | ||||||

| Raw Bio-oil | EXP 1 | EXP 2 | EXP 3 | EXP 4 | EXP 5 | EXP 6 | ||

| Acids | ||||||||

| 1.57 | Formic acid | 2.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2.68 | Acetic acid | 32.32 | 11.02 | 6.62 | 10.29 | 6.27 | 2.08 | 6.27 |

| 12.66 | 4-hydroxybutanoic acid | 2.06 | 0.00 | 3.03 | 0.00 | 2.44 | 2.03 | 2.42 |

| 36.61 | Palmitic acid | 3.59 | 1.86 | 0.00 | 1.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 39.48 | Oleic acid | 2.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 42.68 | 12.88 | 9.65 | 11.85 | 8.71 | 4.11 | 8.69 | |

| Ketones | ||||||||

| 1.49 | Acetone | 0.00 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 1.87 | 1.98 | 4.12 | 2.01 |

| 3.87 | 1-hydroxypropan-2-one | 11.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 7.50 | 1-hydroxy-2-butanone | 1.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 9.93 | Cyclopent-2-en-1-one | 2.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 12.50 | 2-methylcyclopent-2-en-1-one | 0.00 | 3.68 | 3.18 | 3.01 | 2.84 | 2.80 | 3.19 |

| 14.41 | 3-methylcyclopent-2-en-1-one | 1.99 | 3.45 | 2.31 | 2.48 | 2.21 | 2.15 | 2.26 |

| 16.30 | 3-methylcyclopentane-1,2-dione | 5.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 16.60 | 2,3-dimethylcyclopent-2-en-1-one | 0.00 | 2.06 | 3.46 | 3.70 | 3.52 | 3.35 | 3.84 |

| 17.29 | 3,4,4-trimethylcyclopent-2-en-1-one | 0.00 | 2.49 | 2.11 | 1.81 | 1.36 | 1.49 | 0.00 |

| Total | 23.06 | 13.58 | 11.06 | 12.87 | 11.91 | 13.91 | 11.3 | |

| Phenolics | ||||||||

| 14.79 | Phenol | 3.30 | 5.97 | 4.19 | 4.52 | 4.64 | 4.73 | 4.54 |

| 17.03 | o-cresol | 2.76 | 3.52 | 2.71 | 2.79 | 2.90 | 2.48 | 5.57 |

| 17.63 | p-Cresol | 2.23 | 2.81 | 2.27 | 2.41 | 3.02 | 2.53 | 0.00 |

| 18.04 | 2-methoxyphenol | 4.07 | 8.17 | 5.86 | 5.08 | 5.24 | 4.75 | 5.17 |

| 20.11 | 4-ethylphenol | 2.49 | 5.43 | 4.27 | 3.89 | 4.49 | 3.84 | 4.04 |

| 20.82 | 3-ethoxyphenol | 5.02 | 5.44 | 5.03 | 3.68 | 3.17 | 2.90 | 3.13 |

| 22.96 | 4-ethyl-2-methoxyphenol | 2.50 | 4.48 | 3.52 | 2.62 | 2.99 | 2.13 | 2.68 |

| 24.64 | 2,6-dimethoxyphenol | 2.70 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 25.32 | 4-Ethylcatechol | 2.25 | 2.53 | 2.41 | 1.71 | 0.00 | 2.04 | 1.50 |

| Total | 27.32 | 38.35 | 32.3 | 26.7 | 26.45 | 25.4 | 26.63 | |

| Alcohols | ||||||||

| 18.33 | Cyclopropylmethanol | 2.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 2.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Esters | ||||||||

| 2.71 | Ethyl acetate | 0.00 | 16.67 | 24.83 | 27.69 | 33.89 | 36.55 | 32.55 |

| 5.41 | Ethyl propionate | 0.00 | 2.76 | 5.98 | 7.04 | 6.99 | 7.59 | 7.46 |

| 8.86 | Ethyl butyrate | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 1.49 | 1.52 | 1.40 |

| 37.13 | Ethyl palmitate | 0.00 | 4.24 | 3.34 | 3.19 | 3.22 | 3.04 | 3.15 |

| 39.92 | Ethyl oleate | 0.00 | 2.48 | 1.62 | 1.82 | 1.75 | 1.39 | 2.01 |

| Total | 0.00 | 26.15 | 36.79 | 40.94 | 47.34 | 48.57 | 46.57 | |

| Ethers | ||||||||

| 1.54 | Ethoxyethane | 2.22 | 1.77 | 2.10 | 3.25 | 1.67 | 3.91 | 2.09 |

| Total | 2.22 | 1.77 | 2.10 | 3.25 | 1.67 | 3.91 | 2.09 | |

| Others | ||||||||

| 21.44 | 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran | 1.91 | 2.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 17.76 | Isobutyric anhydride | 0.00 | 5.08 | 8.10 | 4.39 | 3.92 | 4.10 | 4.72 |

| Total | 1.91 | 7.27 | 8.1 | 4.39 | 3.92 | 4.1 | 4.72 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).