1. Introduction

The prompt growth of population and extensive urbanization requires alternative energy resources to the depleting conventional crude oil reserves in order to supply the energy demand. Heavy oil is considered as an alternative unconventional hydrocarbon resource to fill the gap of energy supply because of its abundant reserves worldwide and sustainability. Generally, crude oils with a density of higher than 920 kg/m

3 and viscosity of over 30 mPa

.s are classified as heavy oil [

1]. Such hydrocarbons typically contain a significant amount of high-molecular weight compounds such as resins and asphaltenes[

2,

3,

4]. In addition, a vast amount of sulfur-, nitrogen-, and oxygen- containing compounds are concentrated in such macromolecules, which cause several problems during the production, transportation and processing of such crude oil [

5,

6,

7]. Besides, the rich metal-containing complexes such as vanadyl and porphyrin, as well as other heavier metals in the structure of the heavy oils are prone to poison the active catalysts used during the crude oil processing in refineries. Due to the large macromolecules with high carbon content and relatively low hydrogen ratio, the yield of value-added fractions is significantly low in contrast to the conventional light crude oils [

8,

9]. Therefore, it is crucial to upgrade and improve the quality of such hydrocarbon resources before transferring to refineries. Moreover, it is important to obtain high-quality or at least partially upgraded crude oil in reservoir formations in order to ease mobility of crude oils through reservoir rocks and enhance the recovery efficiency.

Currently, steam-based enhanced oil recovery methods continue to be the predominant techniques for effectively producing heavy oil and natural bitumen [

10,

11,

12]. The structural traps with impermeable cap rocks that block the migration of the crude oil and lead to the accumulation of it can serve as natural reactors to carry out upgrading processes, where the heat is supplied by steam, hot water etc. To date many attempts have been made to upgrade heavy oil in-situ by using the steam under relatively mild conditions, which was termed for the first time by Hyne et al. as an “Aquathermolysis” [

13,

14,

15]. However, the efficiency of aquathermolysis reactions was very low and was not sufficient for effective viscosity reduction, especially for heavy oils with high asphaltene content. Early in 1986 Hyne and his colleagues implied that some metal ions, i.e., nickel and cobalt are believed to be involved in the cleavage of some bonds by hydrodesulfurization and hydrocracking processes, as well as water-gas-shift reactions to produce hydrogen intermediates [

16]. Since then, many authors have tried to design different types of catalysts aiming to deliver to the oil reservoir formations, and transition metal-based catalysts have become of focal interest [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. At present, the applied aquathermolysis catalysts can be roughly divided as water-soluble, oil-soluble and dispersed. Although the efficiency of the latter catalysts is high, the injection of such catalysts by requiring stable suspension to the downhole is cost-effective and challenging. Instead, many authors are focused on the developing oil-soluble catalysts based on different ligands due to the high sweep efficiency. Qin et al. synthesized oil-soluble iron oleate to improve aquathermolysis reactions [

23]. The obtained laboratory data showed that the viscosity reduction degree was over 75% at 200℃, 24 hours and 0.3 % catalyst solution concentration. The authors noted that catalyst does not only promote a cleavage of C-S bonds, but also accelerates the scission rate of C-O and C-N bonds [

23]. Zhao et al. synthesized oil-soluble catalyst based on 2-ethyl-hexanoic acid ligand, and evaluated its performance on upgrading heavy oil sample from Liaohe field[

24]. The content of light fractions increased, while the ratio of resins and asphaltenes decreased after the catalyst assisted aquathermolytic upgrading. The authors reported decrease in the content of sulfur by 0.5% and increase in the atomic ratio of H/C from 1.63 to 2.0 [

24]. Yi et al. carried out a comparison study to evaluate the efficiency of water-soluble catalysts and oil-soluble catalysts based on nickel (NiN) and iron naphthenates (FeN) on the aquathermolytic upgrading of resins and n-pentane asphaltenes, which were previously isolated from Liaohe heavy crude oil [

25]. According to authors, the activity sequence of the catalysts was as follows: without catalyst < NiSO4 < FeSO4 < NiN < FeN, which means oil soluble catalysts had higher efficiency than water soluble ones in terms of aquathermolytic upgrading of resins and asphaltenes. Al-Muntaser et al. [

26] and [

27] Suwaid et al. studied the role of oil-soluble catalysts based on metal stearate on hydrogen donating capacity of decalin and upgrading of heavy oil under steam injection conditions. The authors imply that aquathermolytic upgrading using Ni-stearate demonstrated catalytic activity in terms of hydrogen production and facilitating the in-situ upgrading of hydrocarbons. Particularly, the viscosity of upgraded oil was reduced from 2034 mPa

.s to 1031 mPa

.s, measured in identical conditions. Moreover, significant decrease was obtained in resins and asphaltenes contents of heavy oil from 26.30 and 8.26% to 16.55 and 1.49%, respectively. Some other organic ligands such as octanoate and decanoate are also reported as an effective coupling compounds for the synthesis of oil-soluble aquathermolysis catalysts [

7]. Although, the oil-soluble catalyst precursors exhibited high catalytic performance in aquathermolytic upgrading of heavy oil, implementation of organometallic catalysts in the fields can involve significant costs. The oil-soluble catalysts are expensive to obtain and require additional facilities for the synthesis. Solubility of the catalyst precursors in organic solvents is also challenging, as not all the ligands can provide excellent solubility in oil phase. It is crucial in terms of injectivity and distribution of catalyst precursors through the porous reservoir rocks without precipitation. Moreover, the synthesis of oil-soluble catalysts has environmental challenges due to the additional applied chemicals and disposal of used water, which has to be treated or utilized. The management of any by-products generated during the synthesis may also pose challenges in terms of environmental impact. These procedures without any doubt significantly increase the cost of oil-soluble catalyst precursors.

On the other hand, water-soluble catalysts are known as cheap, easy-to-handle metal salts with less impact to the environment and pose minimal health and safety risks. Such catalyst precursors do not require other hazardous organic additives and do not require regeneration or separation from oil bulk. Meanwhile, water-soluble catalyst precursors can be directly injected into the well by dissolving salts in water, which can significantly reduce the cost of implementation. Chen et al. synthesized a series of water-soluble metal complexes based on hydroxyl carbonyl acid and metal salts [

28]. The authors evaluated the upgrading performance of the synthesized metal coordination complexes at 180°C for 24 h in case of heavy crude oil with no sand from Tazhong reservoir. The viscosity of heavy oil sample was reduced by 80% using only 0.1% of the iron (III) coordination complex. Deng et al. developed water-soluble catalytic complex based on Co (II) for steam-based upgrading of heavy oil sample from Huabei reservoir [

29]. Introduction of 0.15% catalyst and 15% methanol to the aquathermolytic process carried out at 180°C for 24 hours, resulted to the heavy oil viscosity reduction degree of 85.3%, and the pour point was altered by 9.0°C. Clark et al. studied the influences of nickel and vanadyl salts, as well as transition metal cations on the aquathermolysis of sulfur-containing model compounds [

15,

30]. The authors found that certain cations were active for thiophane conversion, while others were reactive for tetrahydrothiophene, which was explained by the catalytic nature of the metals and chemical properties of the model compounds. The same authors studied the catalytic efficiency of the metal ions such as Fe

+2, Ru

+2, Os

+3, Co

+2, Rh

+3, Ir

+3, Ni

+2, Pd

+2, Pt

+2, and Pt

+4 on hydrodesulfurization of thiophene and tetrahydrothiophene during aquathermolysis processes[

31]. The Pt (IV) solution revealed the best performance by reducing the content of sulfur at least by 40% (depends on the chemical nature of the used model compound). The iron (II) sulfate was used to promote hydrocracking of bituminous oil at higher temperature ranges 375-415°C [

18]. Although the catalyst contributed to the rise of the asphaltenes content from 15% to 20%, the viscosity of upgraded oil was reduced from 2140 mPa

.s to 520 mPa

.s. It shows that the content of the asphaltenes in crude oil mixture is not the sole deterministic factor of viscosity alteration. Zhong et al. investigated the synergetic effect of water-soluble Fe (II) and hydrogen donor solvent – tetralin on the aquathermolytic upgrading of heavy oil sample from Liaohe [

32]. The authors observed that with increasing Fe concentration, the viscosity of heavy oil sample was further reduced. If hydrogen donor and iron catalyst without tetralin contributed to the viscosity reduction of 40% and 60%, respectively. Then, the combination of the water-soluble catalyst and hydrogen donor reduced the viscosity of heavy oil sample by 90%. According to the temperature optimization study, the authors imply that the favorable temperature to carry out aquathermolysis reaction is 240°C. The researches on exploring and developing new catalytic complexes are continued to better the efficiency of the water-soluble catalysts. The stability and durability of the water-soluble catalysts is still poorly understood. Few researchers have addressed the problem of catalyst deactivation by the formation of the coke-like substances under the harsh conditions of aquathermolysis process. In this regard, developing water-soluble catalysts that can efficiently promote the aquathermolysis reactions, while suppressing unwanted side reactions and remaining active for a long period is challenging. Further focus should be placed on the design of water-soluble catalysts, optimization of operational conditions, and studying overall mechanisms of the catalytic aquathermolysis of heavy oil.

With this in mind we tried to evaluate the performance of nickel and iron sulfates as water-soluble metal salts on the aquathermolytic upgrading of heavy oil sample produced from Ashal’cha reservoir at temperature of 300°C, for 24 hours. We hope that our research will be beneficial for decisive makers in solving the problems regarding the applications of water-soluble catalysts to enhance the production of heavy oil and upgrade it in-situ.

2. Materials and Methods

The object of the given study was a heavy oil sample produced from Ashal’cha oil field, which is located in the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia Federation. The density and dynamic viscosity of the oil sample under normal conditions is 0.951 g/cm3 and 3280 mPa.s, respectively. The average content of high-molecular components is about 45 %wt., and the content of sulfur can reach as high as 5 %wt.

The iron and nickel salts with assay of more than 98%, which were manufactured for laboratory uses were purchased from LLC «ChemTrade» (Russia Federation). The catalytic aquathermolysis processes using water-soluble catalysts NiSO

4 and FeSO

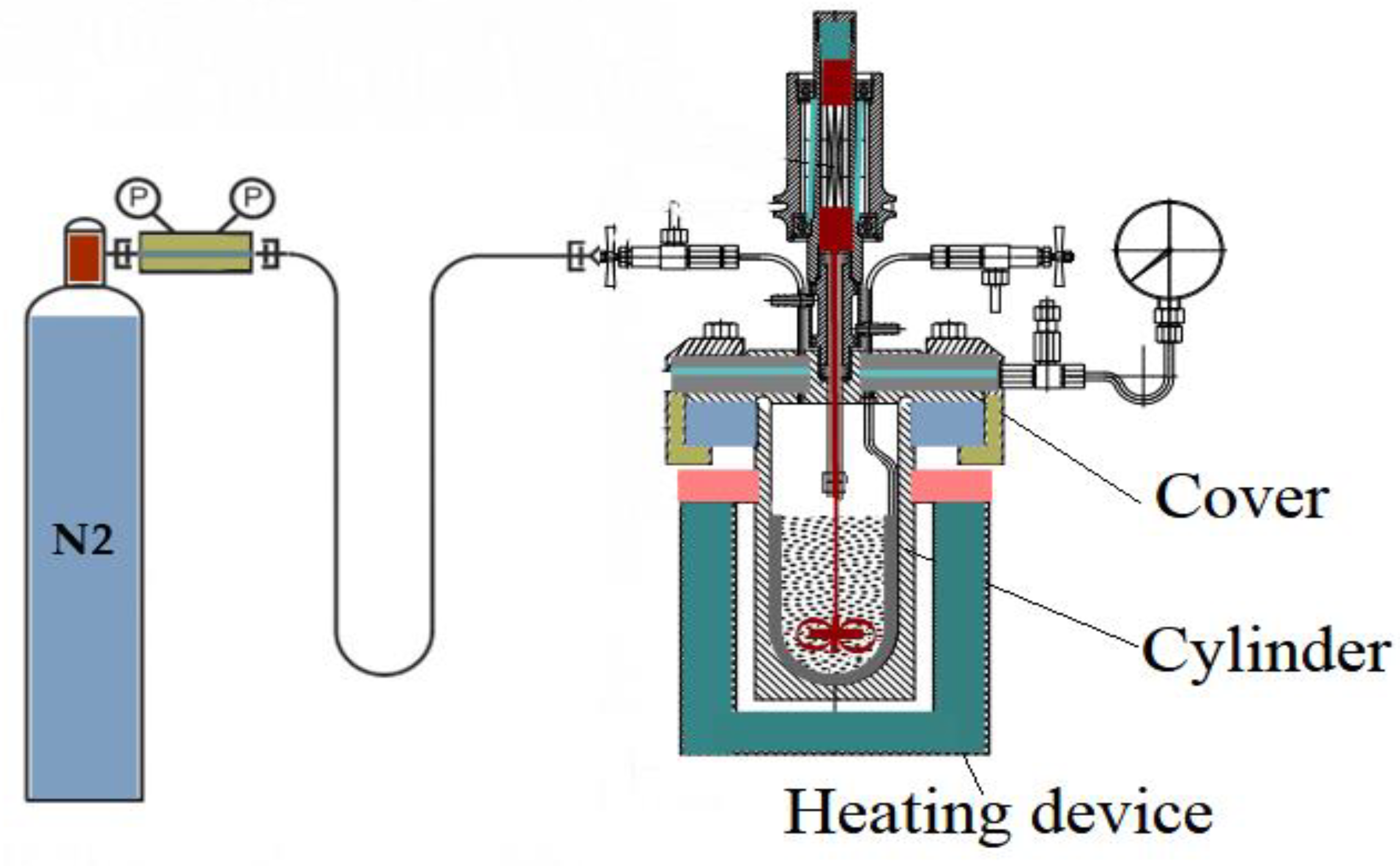

4 are conducted in a high pressure and high temperature batch reactor with stirrer (HPHT), which is regulated by a control unit connected to a personnel computer for monitoring and recording the kinetics and the progress of the process. The scheme of the HPHT reactor is illustrated in

Figure 1. The model system was initially purged with nitrogen for 20 minutes at room temperature to provide inert ambient of the process before the temperature in the reactor was raised up to 300°C in less than 1 hour and maintained for 24 hours. The HPHT reactor is then cooled down at room temperature. The oil: water mass ratio was selected 70:30 in order to simulate the process of aquathermolysis in steam stimulated production techniques. The concentration of the catalyst was 2 %wt. from oil bulk.

2.1. Elemental Analysis of Oil Samples

A Perkin Elmer 2400 Series II (Perkin Elmer, Massachusetts, USA) Analyzer was used to evaluate the changes in the mass content of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur in the composition of oil sample before and after thermo-catalytic upgrading. The difference between the one and the sum of the CHNS content can be attributed to the content of oxygen. The results of the given analysis method allow to estimate the atomic ratio of H/C, which reflects the hydrogenation processes during aquathermolytic upgrading. Moreover, it provides information regarding the hydrodesulfurization, hydrodenitrogenation and hydrodeoxygenation of crude oil samples.

2.2. FT-IR of Crude Oil Samples

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis was performed using a Vertex 70 FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker, Ettingen, Germany) in order to identify the changes in the functional groups of heavy oil under the influence of the catalytic systems. The infrared absorption characteristic peaks were identified in the wide range of 400 – 4000 cm-1 wavenumbers.

2.3. Atmospheric Crude Distillation Unit

The crude oil atmospheric distillation was conducted in an ARN-LAB-03 distillation unit as per ASTM D86 [

33]. The heavy crude oil samples (initial and after upgrading) were evaluated by fractionation of them into light-end and heavy-end hydrocarbons. The light-end hydrocarbons referred to gasoline and diesel fractions with the boiling point ranges of initial boiling point (i.b.p) – 200°C and 200°C – 300°C, respectively. The heavy-end hydrocarbons correspond to the fractions, the boiling point of which are higher than 300°C.

2.4. Dynamic Viscosity of Crude Oil Samples

The dynamic viscosity of oil samples was measured using a Fungilab rotational viscometer Alpha L series combined with a temperature maintaining unit MPC K6 from Huber (Offenburg, Germany). The temperature dependent viscosity values were measured in the temperature ranges of 20 to 80 °C with a step of 20 °C.

2.5. SARA-Analysis

The SARA analysis is a widely employed technique for characterizing different fractions of petroleum. It involves the chromatographic separation of crude oil into four primary categories based on polarity: saturates, aromatic compounds, resins, and asphaltenes. Asphaltenes were isolated from the maltenes by the addition of n-heptane. The oil-to-solvent ratio was 1:40 by weight. It is important to note that the applied solvent determines the nature of the asphaltenes isolated from the oil [

34]. The n-alkane soluble components – maltenes are then separated by passing their mixture through a chromatographic column with an adsorbent. In the given study previously calcined aluminum oxides are used as the adsorbent. The chromatography column is tapped with a rubber tube after a portion of aluminum oxide is poured into the column for its sealing, and n-heptane is carefully poured into the upper part of the column. The n-heptane is passed through the column until the residue discolors. The expiring fraction of Saturates is collected. When the upper part of the aluminum oxide is almost dry, toluene is added to the column. The collecting flask is changed and the Aromatics fraction is collected. The toluene is passed through until the expiring solvent is discolored. Then a 150:50 toluene/methanol mixture is passed through the column in order to elute Resins fraction. The solvents of all three fractions are distilled off and evaporated under vacuum till constant weight of fractions was reached.

2.6. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy (GC MS)

The Saturates and Aromatics fractions obtained from the SARA analysis were further analyzed using a GC MS analysis method. The complex system was composed of a gas chromatography “Chromatech-Crystal 5000” manufactured in Yoshkarala, Russia, and a mass-selective detector ISQ produced in USA. The results obtained were processed using the XCalibur application. For the experiments, a capillary column with a length of 30 m and a diameter of 0.25 mm was employed. The carrier gas used was helium, flowing at a rate of 1 mL/min, and the column temperature was set to 310°C. The thermostat regime was adjusted as follows: starting with a temperature rise from 100°C to 150°C at a heating rate of 3°C/min, followed by a further increase from 150°C to 300°C at a heating rate of 12°C/min, and then maintaining this temperature isothermally until the end of the analysis. In terms of the GC MS settings, the Electron energy was set to 70 eV, and the ion source temperature was maintained at 250°C. To identify the molecules and compounds, the NIST Mass Spectral Library and relevant literature sources were used.

3. Results and Discussions

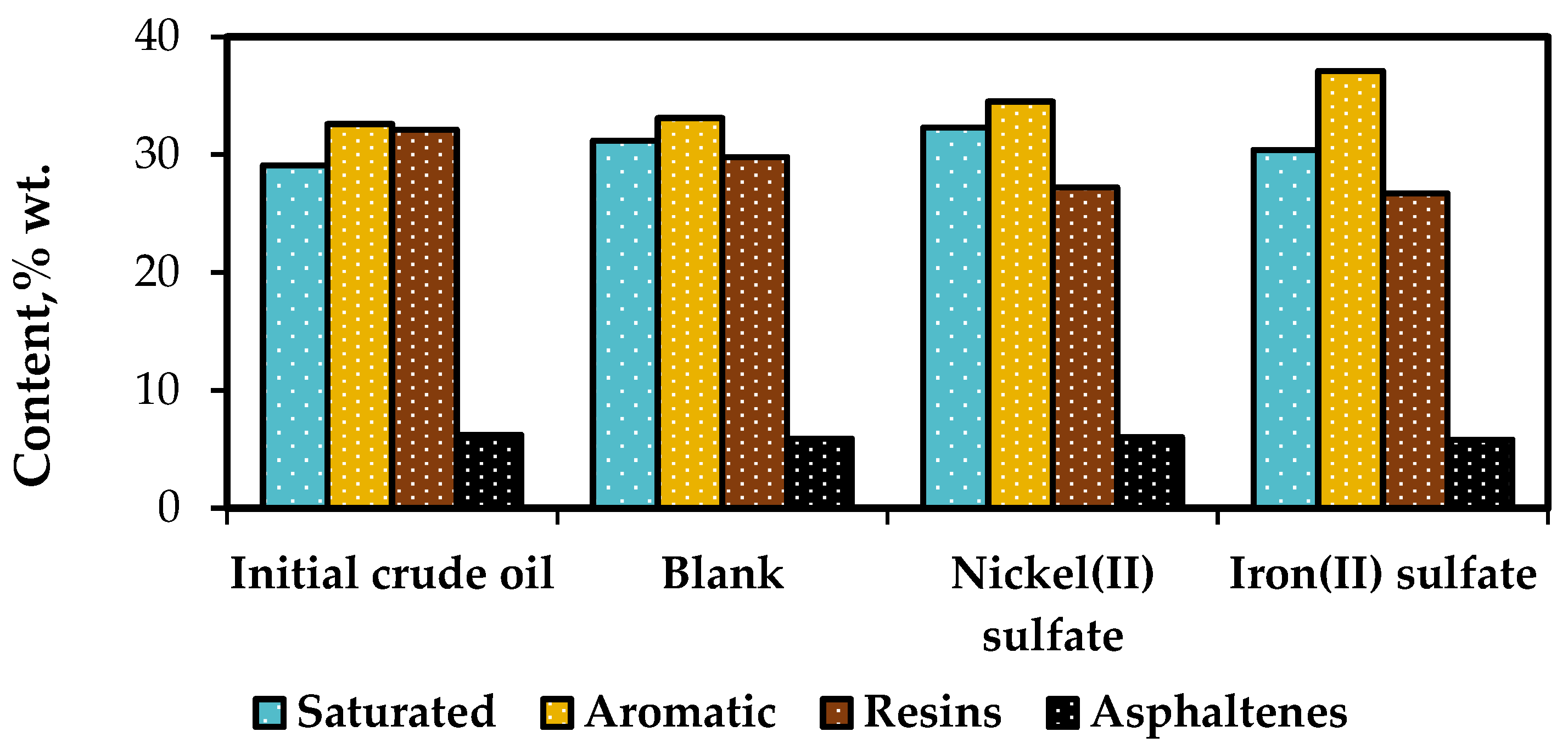

SARA analysis provides valuable information about the group composition of heavy oil, which is essential for evaluating the upgrading performance of the process. It helps in understanding the colloidal structure of heavy oil during production, transportation, and refining processes. The analysis also assists in predicting the stability of heavy oil and establishing the necessary measures to mitigate the challenges associated with heavy oil processing. The SARA-fractions of initial (original) crude oil were compared with the fractions of non-catalytically upgraded oil sample (blank) and catalytically upgraded ones (

Figure 2).

Based on the data presented in

Figure 2, the native crude oil sample had a resin content of 32.1 %wt. and an asphaltene content of 6.2 %wt. Among the catalysts tested, Iron (II) sulfate exhibited the most effective performance in enhancing the group composition. It led to a reduction in resin content by more than 16.8% compared to the initial sample. Additionally, the content of asphaltenes decreased from 6.2 %wt. to 5.8 %wt. The presence of Iron (II) sulfate facilitated the destructive hydrogenation of resins, resulting in an increase in the content of saturated and aromatic compounds from 29.1%wt. and 32.6%wt. to 30.4%wt. and 37.1%wt., respectively. On the other hand, Nickel (II) sulfate also contributed to the reduction of resins (27.2 %wt.), but the content of asphaltenes remained similar to that of the blank sample (6 %wt.). These findings demonstrate that catalytic aquathermolysis reactions lead to a significant increase in light components and a decrease in heavy components within the heavy oil.

Viscosity is the most important technological property of oil, as it determines its mobility in the reservoir rock. The oil recovery factor strongly depends on the viscosity values. Some authors imply that viscosity depends on the content of asphaltenes [

35,

36]. In other words, the highly viscous crude oil contains significant amount of asphaltenes. The elevated viscosity of heavy oil can be attributed to its abundant presence of macromolecular structures. Decrease of viscosity is expected with the destruction of primarily C-S bonds in the composition of resins and asphaltenes of heavy oil and hydrogenation of free radicals under aquathermolytic conditions.

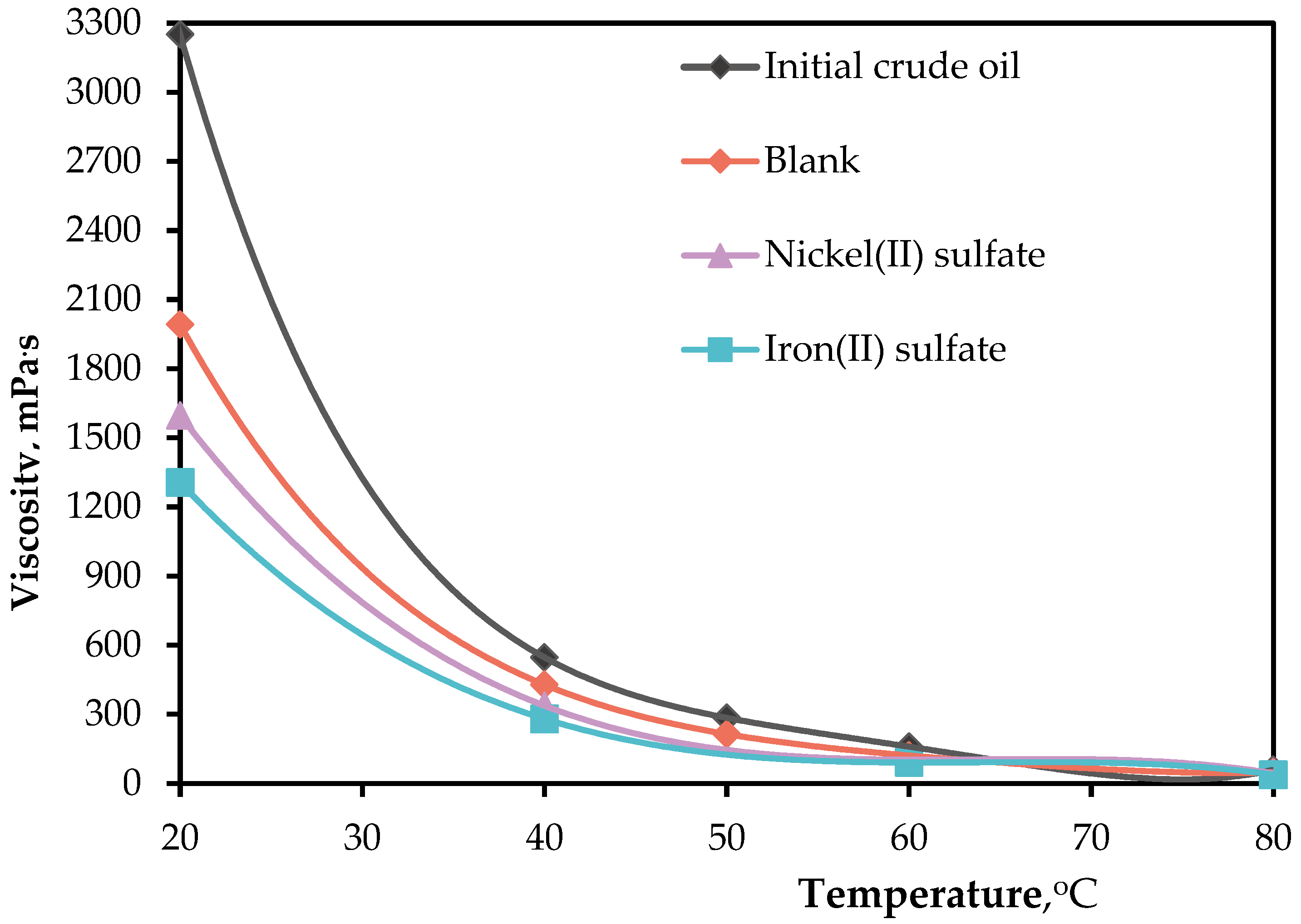

Figure 3 shows the results of measuring the temperature-dependent viscosity characteristics of the initial oil and catalytic aquathermolysis products. The water-soluble catalysts FeSO

4 and NiSO

4 contributed an obvious viscosity reduction in contrast to the viscosity of initial crude oil sample and viscosity of blank sample. The FeSO

4 promoted the aquathermolytic scission of carbon-heteroatom bonds, which led to the viscosity reduction from 3250 mPa

.s (initial crude oil) to 1306 mPa

.s. Although, the nickel (II) sulfate contributed to the viscosity alteration by 50%, the iron (II) sulfate performance was the highest ~ 60%.

Heavy oil typically has a high carbon content and a low hydrogen content, which determines polyaromatic content that determines its high viscosity and low quality. Upgrading of heavy oil involves increasing the hydrogen content relative to carbon, thereby improving its quality owing to the hydrogenation reactions. To evaluate catalysts for the intensification of hydrogenation reactions, the atomic H/C ratio of oil samples before and after catalytic upgrading were estimated and compared in

Table 1. Catalysts facilitated the hydrogenation reactions, wherein hydrogen is added to the heavy oil molecules, resulting in increased H/C ratio.

As can be seen from

Table 1, the addition of catalysts Iron (II) sulfate and Nickel (II) sulfate equally contributed to the increase in the atomic ratio of H/C from 1.52 before the reaction to 1.99, which indicates a formation of significant number of aliphatic compounds after catalytic upgrading. In addition, water-soluble catalysts promoted hydrodesulfurization of the heavy oil, which reduced the content of sulfur from 5.5 %wt. to 4.5 %wt.

The atmospheric distillation of oil is one of the informative parameters to evaluate the upgrading performance of the catalytic aquathermolysis process. The atmospheric distillation of heavy oil samples before and after catalytic upgrading are summarized in

Table 2.

According to the results (

Table 2), it can be seen that the initial boiling point in case of using iron sulfate decreases from 168 ºС to 154 ºС, and also leads to an increase in gasoline and diesel fractions by (13% and 53%, respectively), and fractions boiling above 300 ºС are lower by 9% wt. NiSO

4 catalyst leads to an increase of gasoline and diesel fractions by 40% and 9%, respectively, and the fractions boiling above 300 ºС decreased by 2% wt.

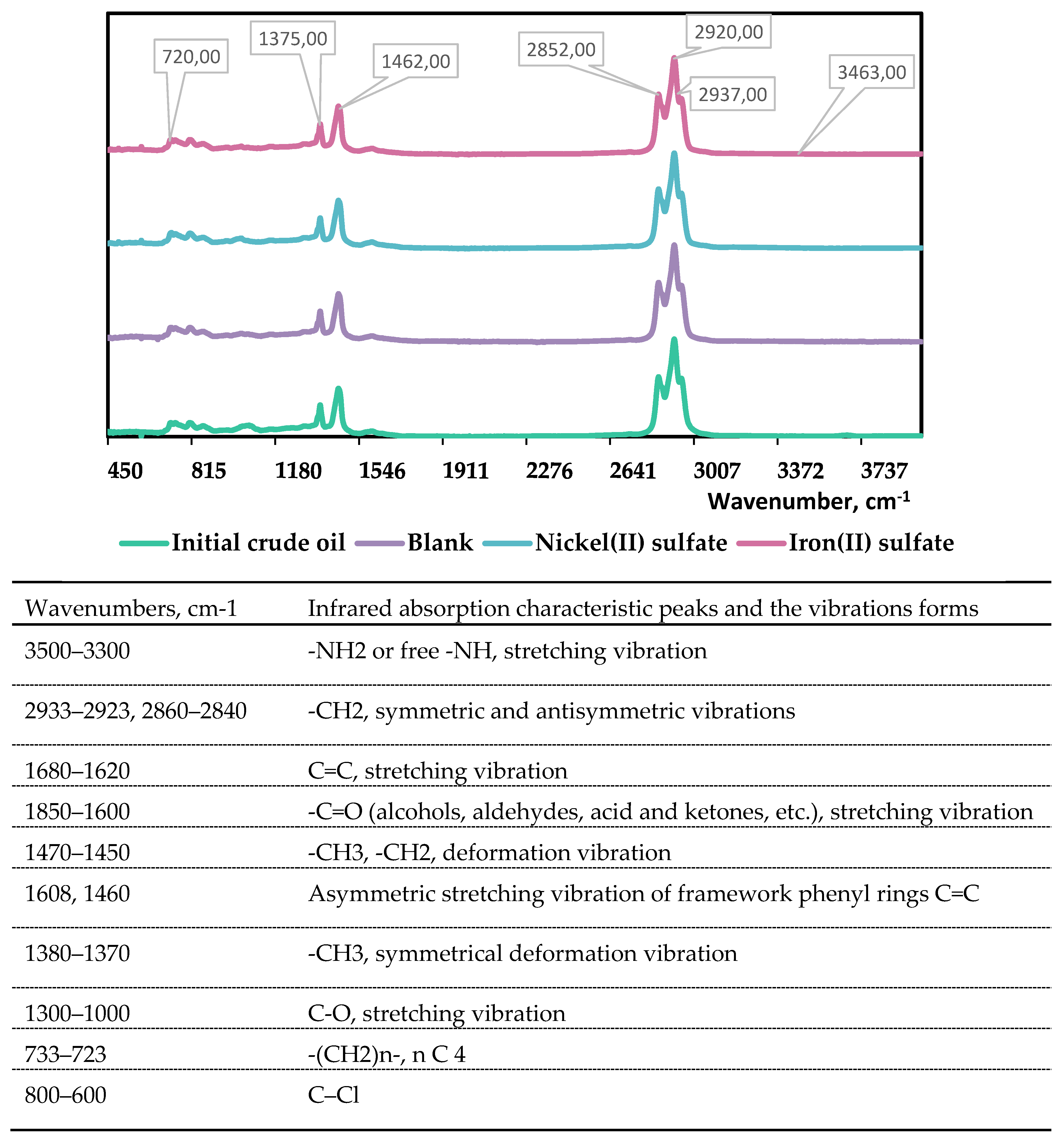

FT-IR Spectroscopy is employed as an analytical technique to assess the effectiveness of the catalysts by examining alterations in functional groups. This method offers supplementary data regarding the structure and chemical composition of heavy oil. The obtained spectra (as shown in

Figure 4) were analyzed to determine coefficients such as C1-aliphaticity, C2-aromaticity, C3-branching, C4-condensation, C5-oxidation, and C6- and C7-sulfurization degrees. These coefficients were estimated according to reference [

37] and are summarized in

Table 3.

The following spectral coefficients were calculated using the provided equations: Aliphaticity (C1) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1450 cm-1 (D1450) to the intensity at 1600 cm-1 (D1600). It indicates the proportion of C-H bonds in aliphatic structures compared to C=C bonds in aromatic structures; Aromaticity (C2) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1600 cm-1 (D1600) to the sum of the intensities at 720 cm-1 and 1380 cm-1 (D720+1380). It indicates the proportion of C=C bonds in aromatic groups compared to C-H bonds in aliphatic structures; Branching (C3) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1380 cm-1 (D1380) to the intensity at 720 cm-1 (D720). It indicates the proportion of methylene groups to methyl groups; Degree of condensation (C4) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1600 cm-1 (D1600) to the sum of the intensities at 740 cm-1 and 860 cm-1 (D740+860). It shows the proportion of C=C bonds in aromatic groups compared to C-H bonds in aromatic structures and provides information about the degree of condensation; Degree of oxidation (C5) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1700 cm-1 (D1700) to the intensity at 1600 cm-1 (D1600). It indicates the proportion of carbonyl groups R-C=O (in the presence of an OH-group) compared to C=C bonds in aromatic structures, providing insight into the degree of oxidation; Degree of sulfurization (C6) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1030 cm-1 (D1030) to the intensity at 1600 cm-1 (D1600). It shows the proportion of S=O bonds in sulfoxide groups (either in sulfonates or sulfonic acids, provided that absorption bands in the range of 1260–1150 cm-1 and 700–600 cm-1) compared to C=C bonds in aromatic groups, indicating the degree of sulfurization; Degree of sulfurization (C7) – This coefficient represents the ratio of the intensity at 1160 cm-1 (D1160) to the intensity at 1600 cm-1 (D1600). It shows the proportion of S=O bonds in sulfonate groups compared to C=C bonds in aromatic groups, providing information about the degree of sulfurization. These coefficients were calculated to evaluate various chemical characteristics of the analyzed samples based on their infrared spectra. They provide valuable information about aliphaticity, aromaticity, branching, degree of condensation, degree of oxidation, and degree of sulfurization in the studied compounds.

According to the results summarized in

Table 3, one can observe that there is a decrease in the coefficients of aliphaticity (C1), branching (C3), and sulfurization (C6). At the same time, there is an increase in condensation (C4) and oxidation (C5) coefficients. These changes strongly suggest that there is a compaction of the naphthenic molecule, along with the substitution of alkyl-naphthene fragments with functional groups containing sulfur and oxygen.

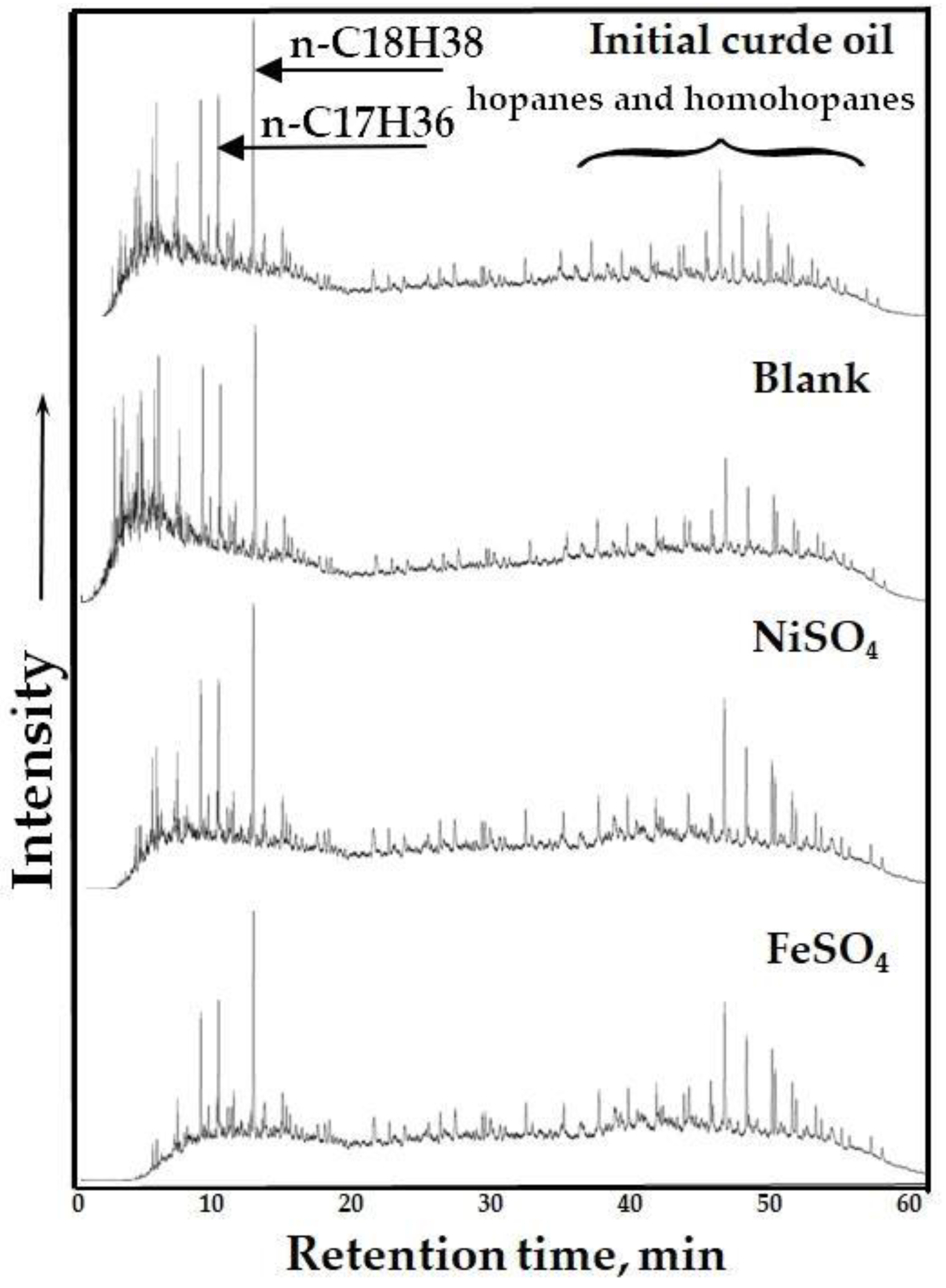

The results of GC MS analysis of saturated hydrocarbons separated from the initial crude oil and upgraded oil samples are shown in

Figure 5. The most significant changes are observed in the lower retention time zone corresponding to the high-molecular-weight n-alkanes. Particularly, the number of normal alkanes with the carbon chain length of higher than 21 in the composition of saturates separated from the oil sample upgraded in the presence of iron sulfate is almost twice the intensity of the corresponding peak observed in the saturate fraction of blank sample. However, the number of iso-alkanes in the composition of saturates fraction of oil sample upgraded using iron sulfate is less than normal alkanes of blank sample. According to the spectra, the peaks correspond to hopanes and homohopanes are also intensified in the presence of both water-soluble metal salts.

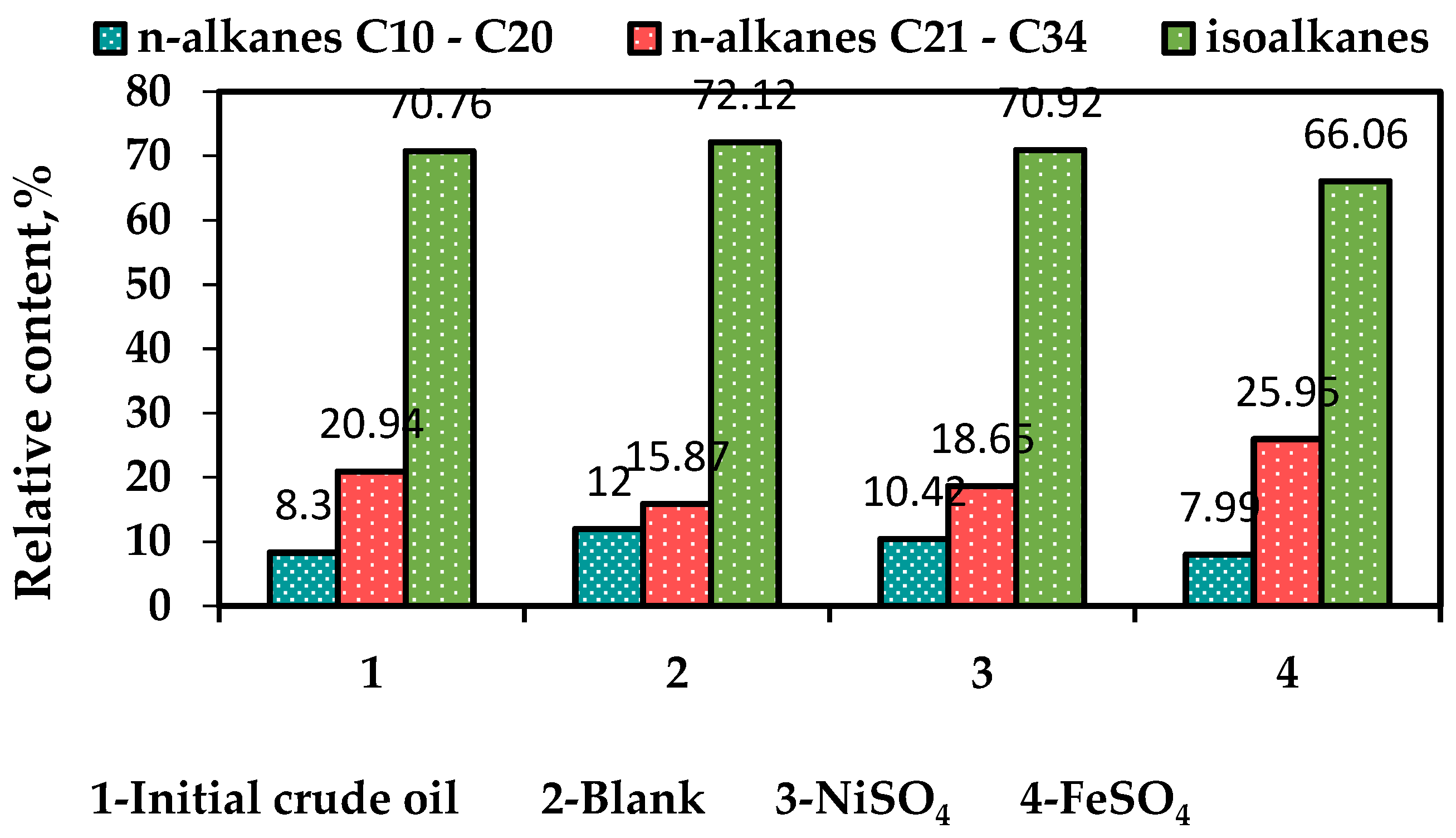

The relative quantitative analysis was employed based on the comparison of spectral area behind the peaks of the samples and the results of relative content of normal alkanes with the carbon chain of less than 20 and more than 21, as well as the relative content of iso-alkanes separated from the crude oil samples are presented in

Figure 6. The nickel (II) sulfate contributed to the increase in the number of low-molecular-weight normal alkanes from 8 to 10%, while the number of C10-C20 n-alkanes is unchanged (8%) in the presence of iron (II) sulfate. However, iron sulfate significantly increased the content of high-molecular-weight normal alkanes by more than 60% compared to the oil sample after non-catalytic treatment. Moreover, the given catalyst contributed to the altering the number of iso-alkanes from 72% to 66%.

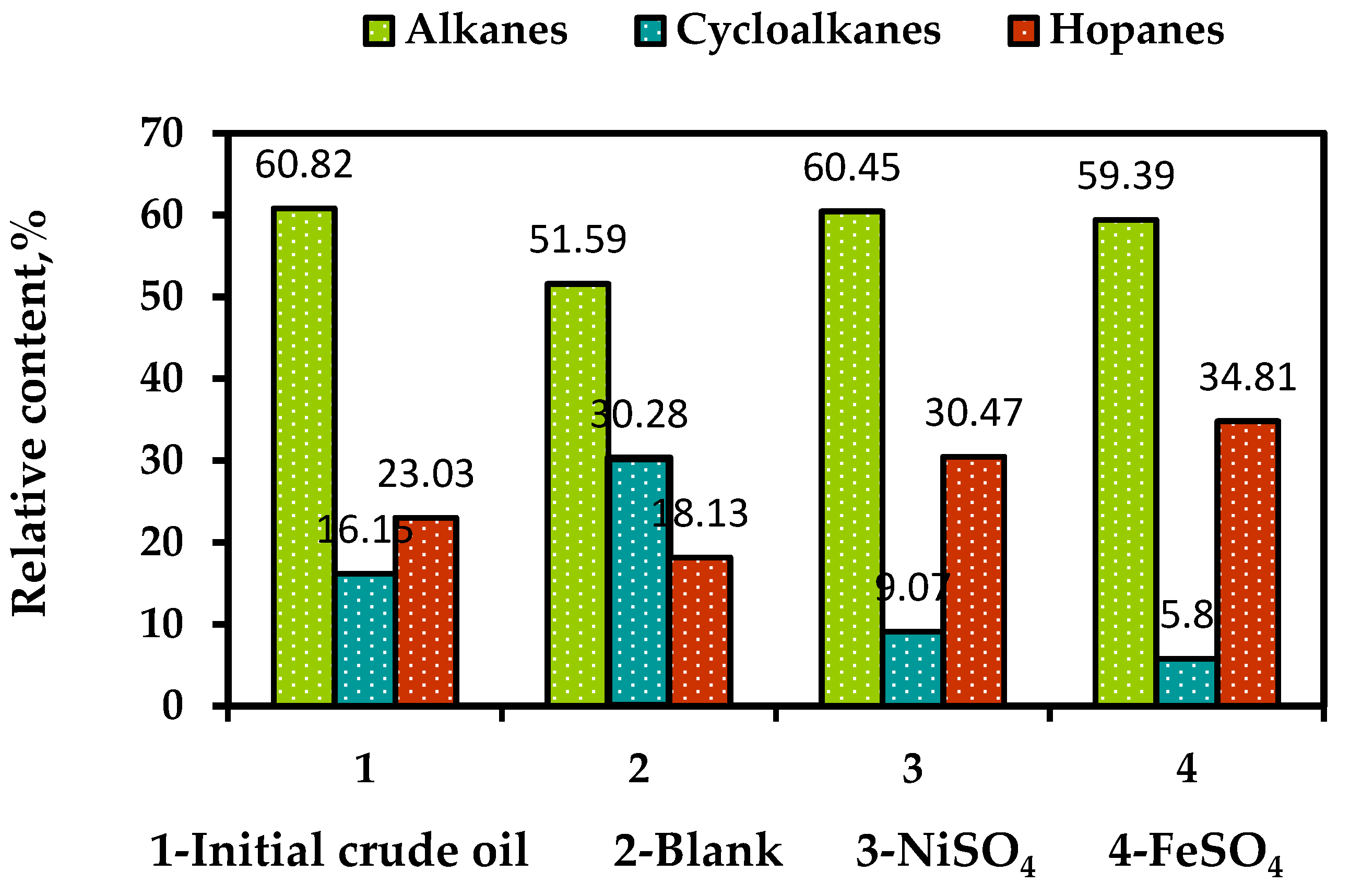

In

Figure 7, the comparison is made between the relative number of saturated hydrocarbons (alkanes) and other compounds such as alkenes and hopanes. The study found that the non-catalytic aquathermolysis of heavy oil led to a decrease in the percentage of alkanes from 61% to 52%, while the proportion of cyclic hydrocarbons is almost doubled. However, addition of the nickel (II) and iron (II) sulfates to the reaction system contributed to the decrease in the number of cyclic hydrocarbons from 30% (blamk sample) to 9% and 6%, accordingly. On the other hand, the number of hopanes were increased twice in the presence of both water-soluble catalysts.

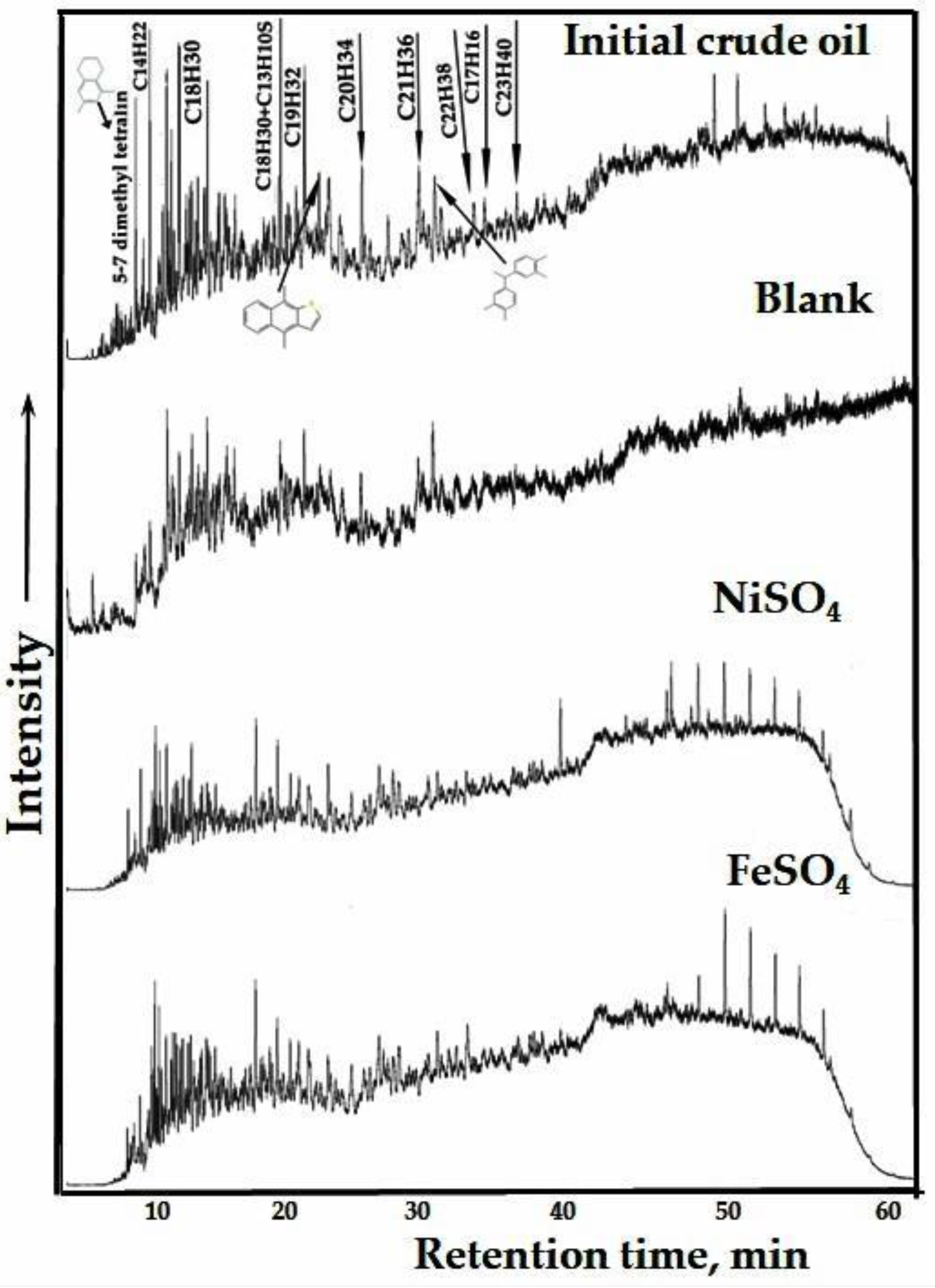

The recorded mass spectra of aromatic hydrocarbons in the mode of TIC are illustrated in

Figure 8. According to the spectra, the significant changes were observed in the intensity of peaks corresponding to alkyl benzenes and thiophenes. The intensity of peaks with the retention time of 22 minutes and higher, which correspond to the C18H30 and heavier aromatic rings – heptadecylbenzene are significantly reduced with addition of the water-soluble catalysts.

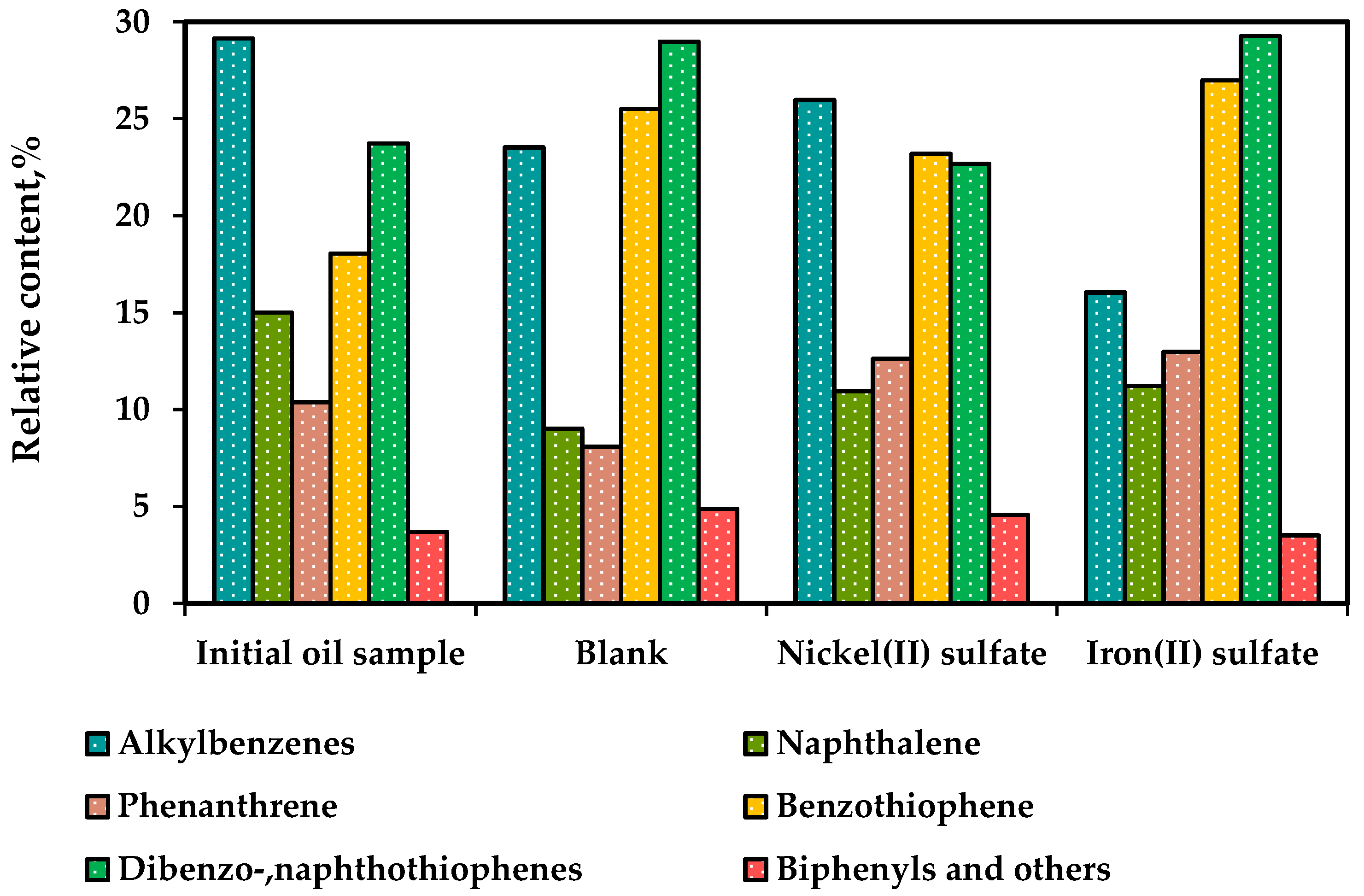

Figure 9 presents the results of a quantitative analysis of aromatic hydrocarbon compounds. The data shows that the proportion of alkylbenzenes decreased from 29% to 24% after non-catalytic upgrading. When catalysts were introduced, the content of alkylbenzenes was further reduced to 16%. Additionally, the content of naphthalene in the aromatic fraction increased from 9% (in the blank sample) to 11% after catalytic upgrading. This suggests that the presence of catalysts had an impact on the distribution of naphthalene. Furthermore, a slight increase in the content of biphenyls and other compounds was observed after both the non-catalytic and catalytic processes. It demonstrates the detachment of peripheral radicals from condensed aromatic rings of resins and asphaltenes, which were bonded by means of C-S, C-N and C-O bonding and further joined the aromatic hydrocarbons.

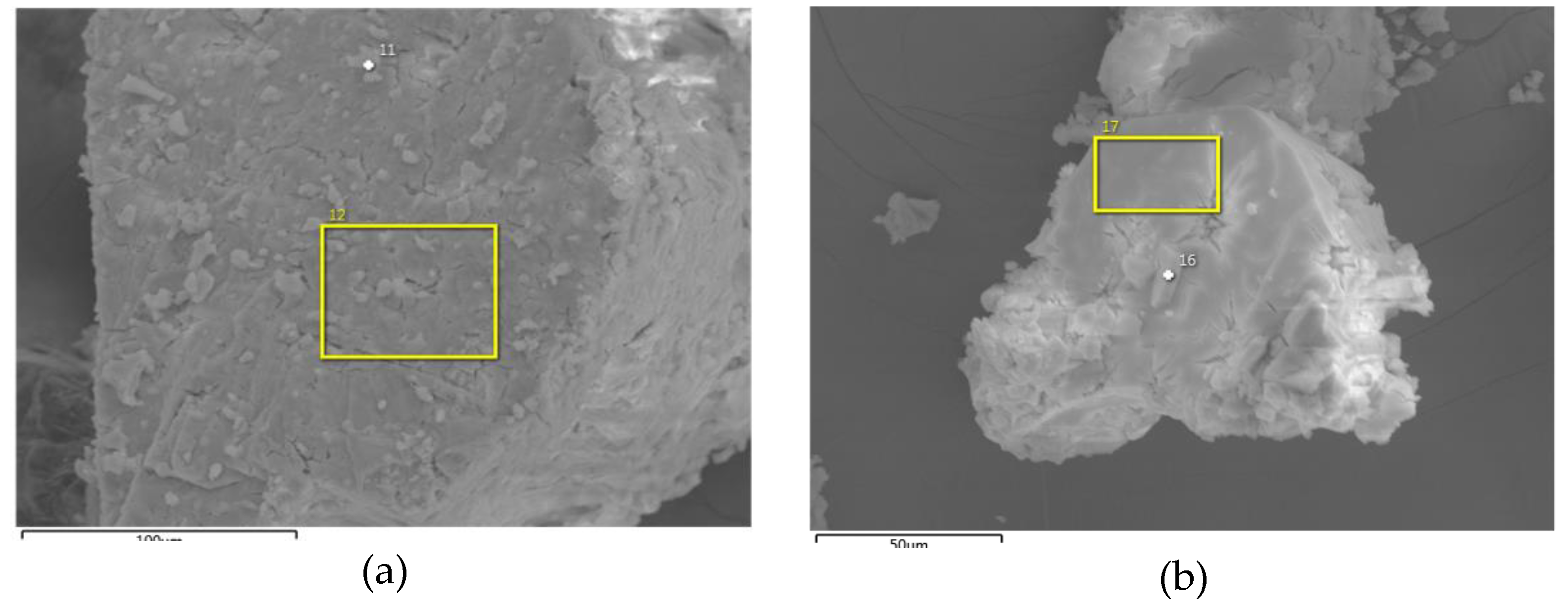

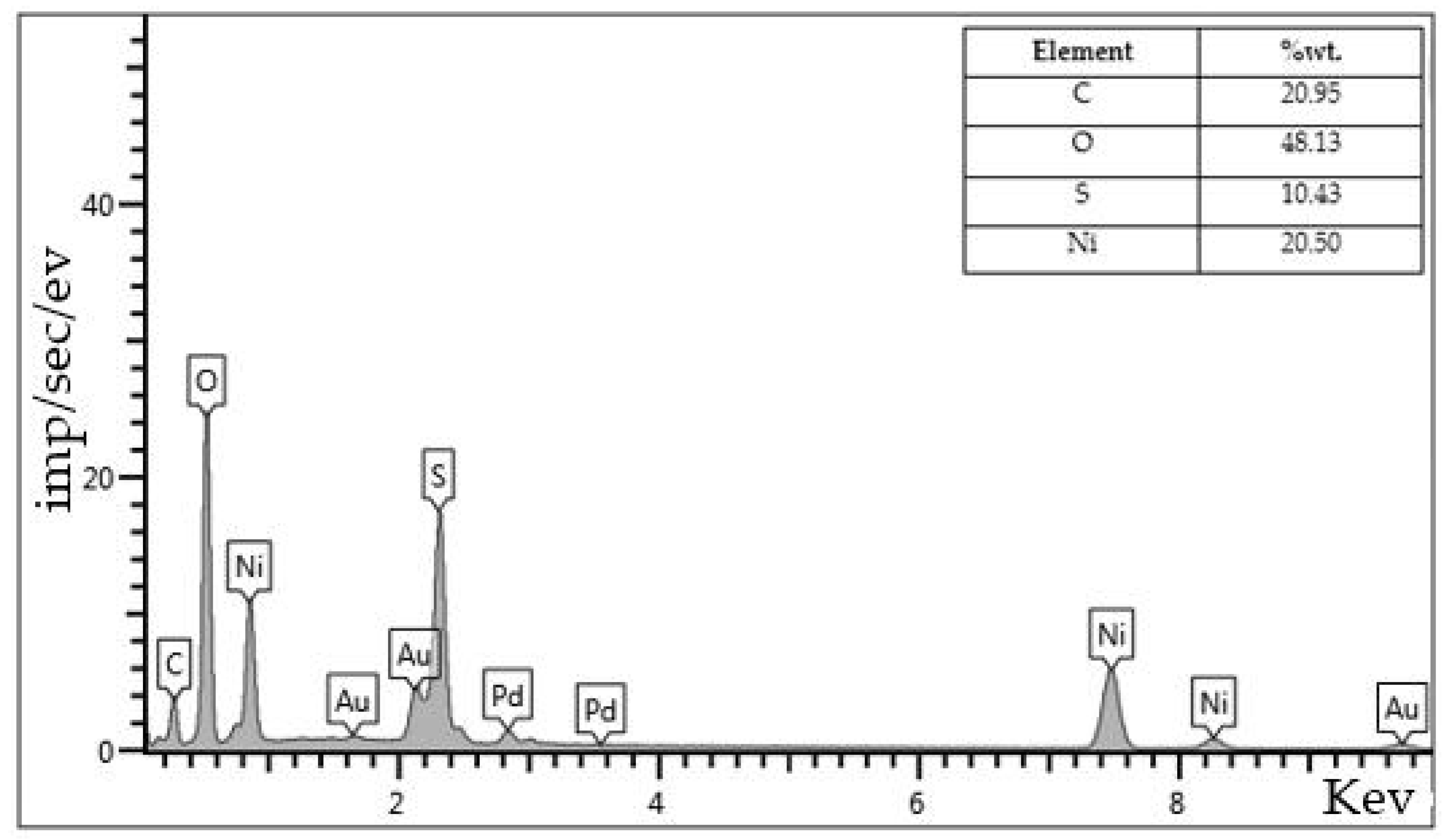

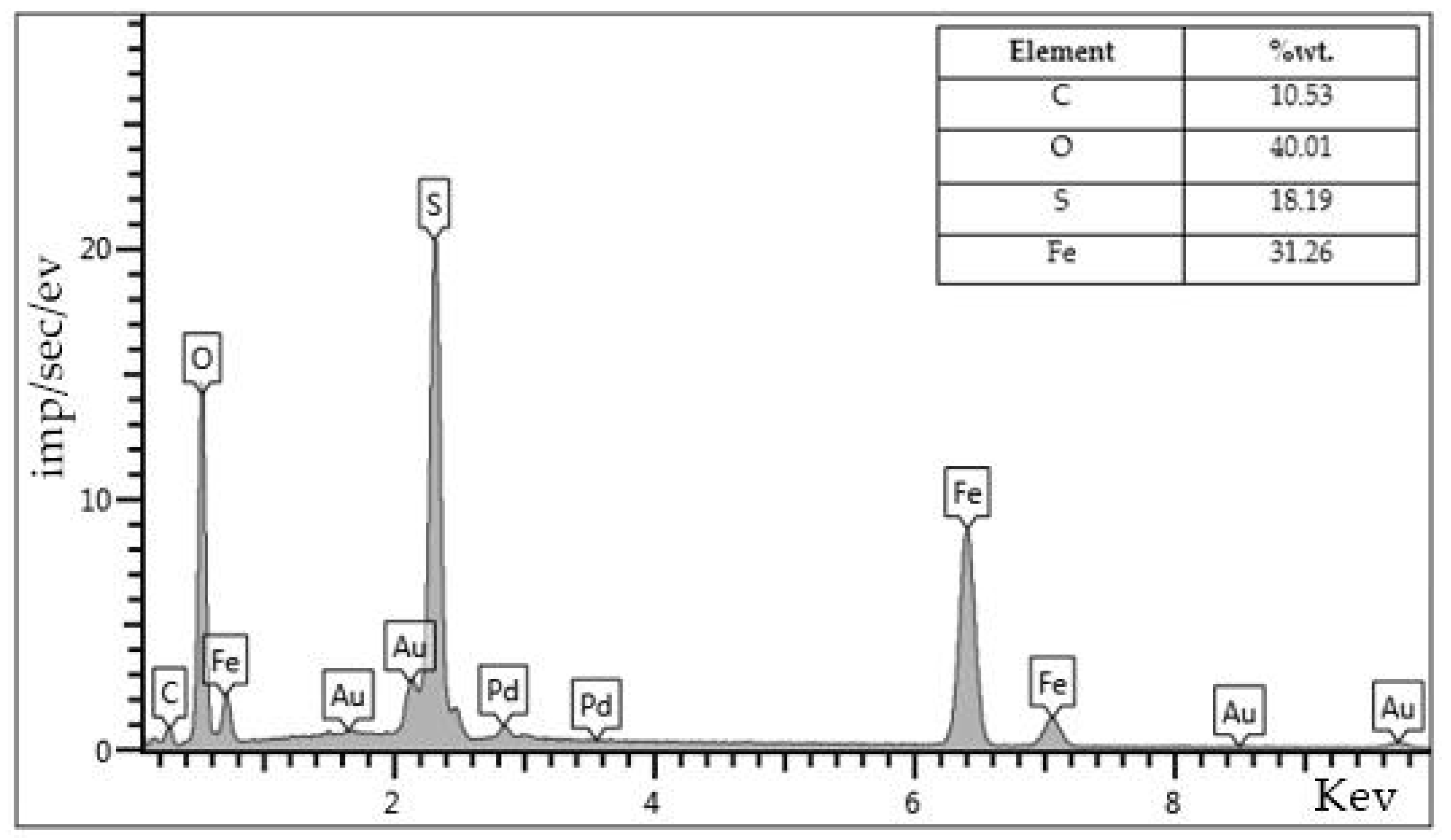

The nature of the microstructure can be seen over a wide magnification range of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis method. In general, SEM analysis is used to facilitate comparison and explanation of microstructures. In SEM images, the microscope is used to qualitatively determine microstructural changes in the matrix of catalyst samples (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). In this way, the microstructure is easy to observe because the images can be magnified. The structure of the catalyst samples was imaged after aquathermolysis processes. The data obtained by EDX provides information on the elemental composition of the metals formed in the reaction as well as the end of the process. Both large-scale and individual surface analyses were performed. The average particle size of the formed metal oxides and sulfides was identified in a micron range. According to the elemental composition (

Figure 11) the share of nickel oxides prevails its sulfide form as the content of oxygen – 48 %wt., while sulfur only 10 %wt. The high ratio of carbon (21 %wt.,

Figure 11) indicates adsorption of the high molecular-weight fragments of heavy oil, which are not dissolved in organic solvent such as, carbenes and carboids on the surface of the nickel catalyst particles. On the other hand, the sulfur content is relatively higher (18%wt.,

Figure 12) in the composition of the iron-based catalyst surface. It indicates that iron (II) sulfate is prone to sulfidation by hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur-containing by-products of aquathermolysis process. Moreover, according to the content of carbon (10 %wt.,

Figure 12), iron oxides and sulfides are less contributed to the coke formation. Hence, such catalysts can longer withstand in the reservoir formations coking process and remain active.

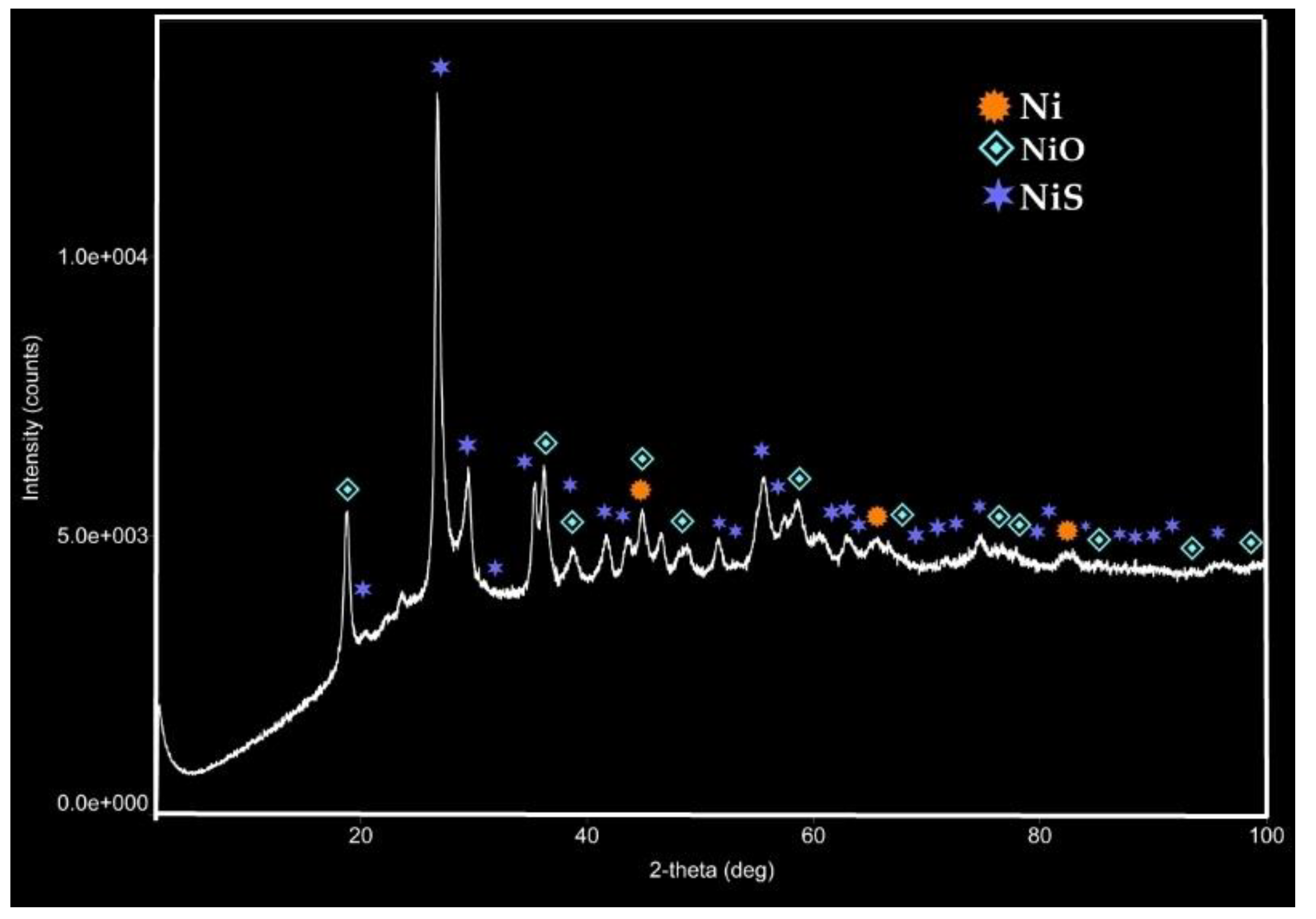

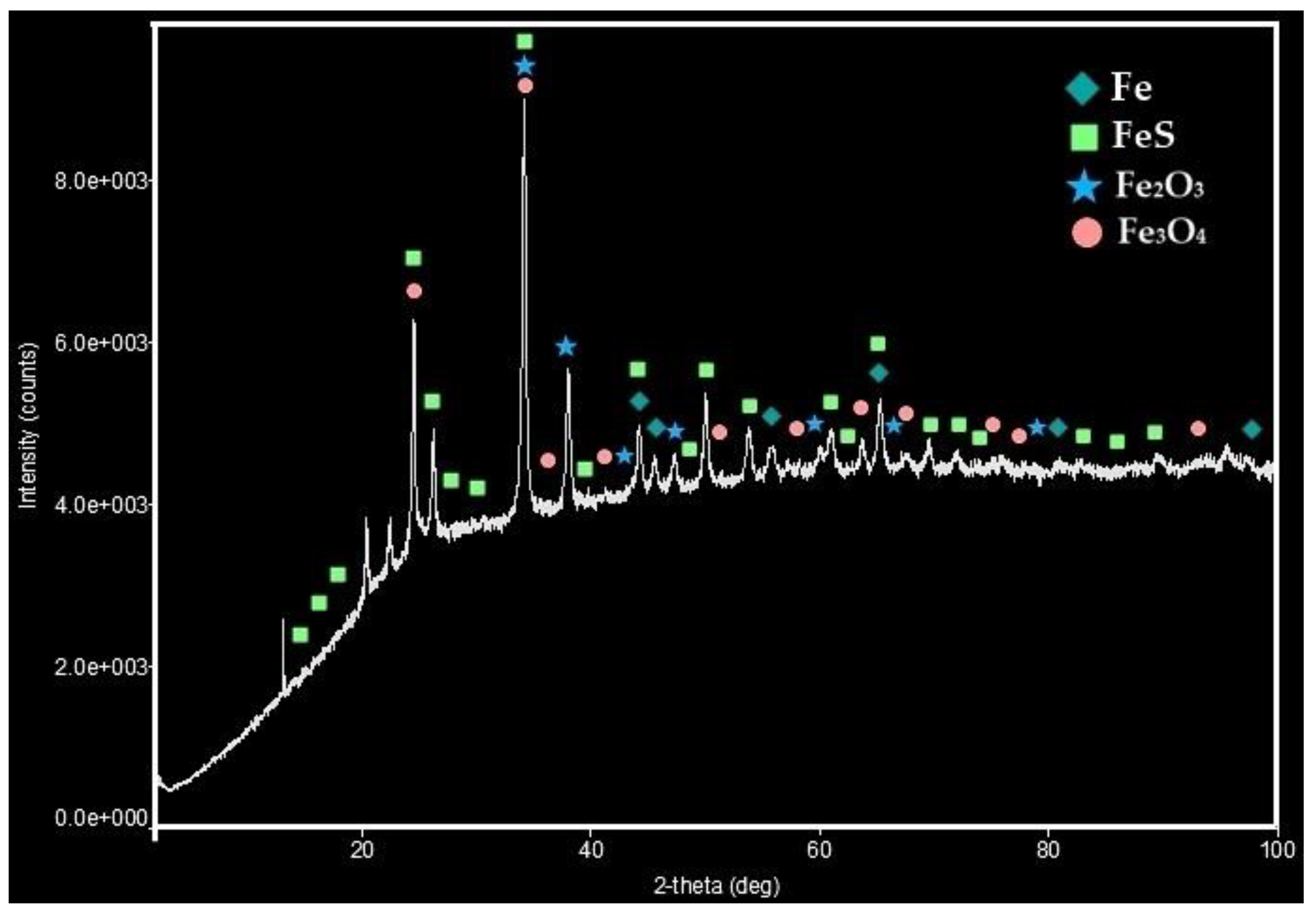

In conjunction with SEM-EDX analysis method, XRD patterns of the isolated catalyst particles from oil bulk after aquathermolysis process (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) provides further characterization of the morphology, phase composition and crystalline structure of the thermal decomposition products of the metal sulfates. The patterns are characterized by a series of sharp peaks corresponding to the crystal lattice planes of Ni, NiO and NiS in case of nickel (II) sulfate and Fe, FeS, Hematite (Fe

2O

3), Magnetite (Fe

3O

4) in case of iron (II) sulfate. Nickel oxide is a cubic crystal structure with a characteristic peak at 2θ values of approximately 19.8°, 37.5°, 42.5°, 58° and 79°. Nickel sulfide or by another name millerite has a hexagonal crystal structure. Its XRD pattern shows peaks at 2θ values of approximately 20.9°, 27°, 42.6°, 54.9°, 62.7°, and 69.4°. The intensity of XRD pattern of nickel phase is relatively very low and presented by 2θ values of 43° and 66°.

The thermal decomposition products of iron (II) sulfate in aquathermolytic conditions are primarily presented by pyrrhotite (FeS), which indicates the involvement of the sulfur-containing by-products of the aquathermolysis reactions in sulfidation of the metal oxides. The prominent peaks around 2θ were observed in the XRD pattern of FeS: 23.9°, 42°, 50°, 55°, 63.8°, 71.9°. Hematite and magnetite has rhombohedral and cubic crystal structure, accordingly.