1. Introduction

The urgency to incorporate circular economy models into agricultural practices is becoming increasingly evident, particularly in the context of efficient resource use. As humanity faces the pressing need to optimise the use of the planet’s resources, it is crucial to align with international frameworks such as the 2030 Agenda and guidelines from organisations such as the United Nations and its specialised agency, the Food and Agriculture Organization [

1]. Integrating circular economy principles into traditional linear agricultural systems is not only advisable but also a moral imperative. The goal is to gradually transform these strategic sectors into circular production models, wherein waste from primary industries is minimised to near zero [

1,

2].

From a technical perspective, the deployment of biorefineries remains limited, despite the increasing prevalence of circular-economy roadmaps. The commercial implementation of biomass-to-products is hindered by insufficient cost competitiveness, as bio-based outputs frequently fail to match the prices of their fossil-derived counterparts. High capital and operational expenditures, feedstock logistics, and scale-up risks have been consistently identified as significant barriers [

3]. In this context, integrated biorefineries that employ cascade valorization, prioritising the recovery of high-value molecules and directing residual streams to lower-value commodities or energy, emerge as a pragmatic approach to achieving competitiveness. This strategy distributes value across co-products while enhancing overall resource efficiency[

4].

Regard rice industry, the second-largest crop in the world by production volume, yet approximately 30% of its yield consists of by-products like rice husk, straw, and bran [

5]. In Extremadura, Spain, where rice production is significantly underutilised, there is an urgent need to add value to these by-products, which are often discarded or used for low-value purposes, such as animal feed [

6].

In this context, rice bran stands out as a high-value by-product because of its rich content of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, including γ-oryzanol. The efficient extraction of rice bran oil (RBO), a valuable oil that can be extracted from rice bran (RB), can be achieved using cold pressing and solvent extraction methods without degradation[

7,

8,

9]. RBO contains several compounds (γ-oryzanol, tocopherol, etc.) that are recognised for their antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties [

10,

11]. The specific properties of γ-oryzanol depend on the substituents on each of its [

10], but this family of compounds offers diverse applications in food formulations, cosmetics, and nutritional supplements[

7,

12]. Specifically, RBO is interesting regarding its possible application in post-harvest control to reduce spoilage in this important worldwide industry.

Addressing the environmental impact of traditional single-use plastics is also critical, particularly those made from low- and ultra-low-density polyethylene used in packaging [

13,

14]. In response, there is a growing trend towards using natural polymers, such as starch, and alternatives, such as paper and wood. However, the vast amount of petrochemical plastics that need to be replaced underscores the necessity for the further development of sustainable alternatives. One significant barrier to the widespread adoption of bio-based plastics, such as polyhydroxybutyrate and its copolyesters, is their high production cost, which limits their economic feasibility [

15,

16]. To address this challenge, it is essential to integrate bio-based plastic production into biorefinery models. Effective strategies include incorporating bioplastic production as a stage within biorefineries, reducing the costs of fermentation and culture media, and minimising purification expenses. Since the early 2000s, research in this field has increased steadily, focusing on cost-effective solutions for bioplastics [

17]. For example, several studies have successfully used residues and by-products in fermentation. Huang et al. 2006 demonstrated the successful application of RB in such processes in the laboratory.

Additionally, the industrial production of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose from various plant biomasses has been well established. Integrating these proven extraction methods into the final stages of biorefinery models provides a pathway for creating economically viable and sustainable systems. These biorefinery models are crucial for transforming the agricultural sector, allowing the conversion of diverse agricultural residues into high-value compounds [

19,

20].

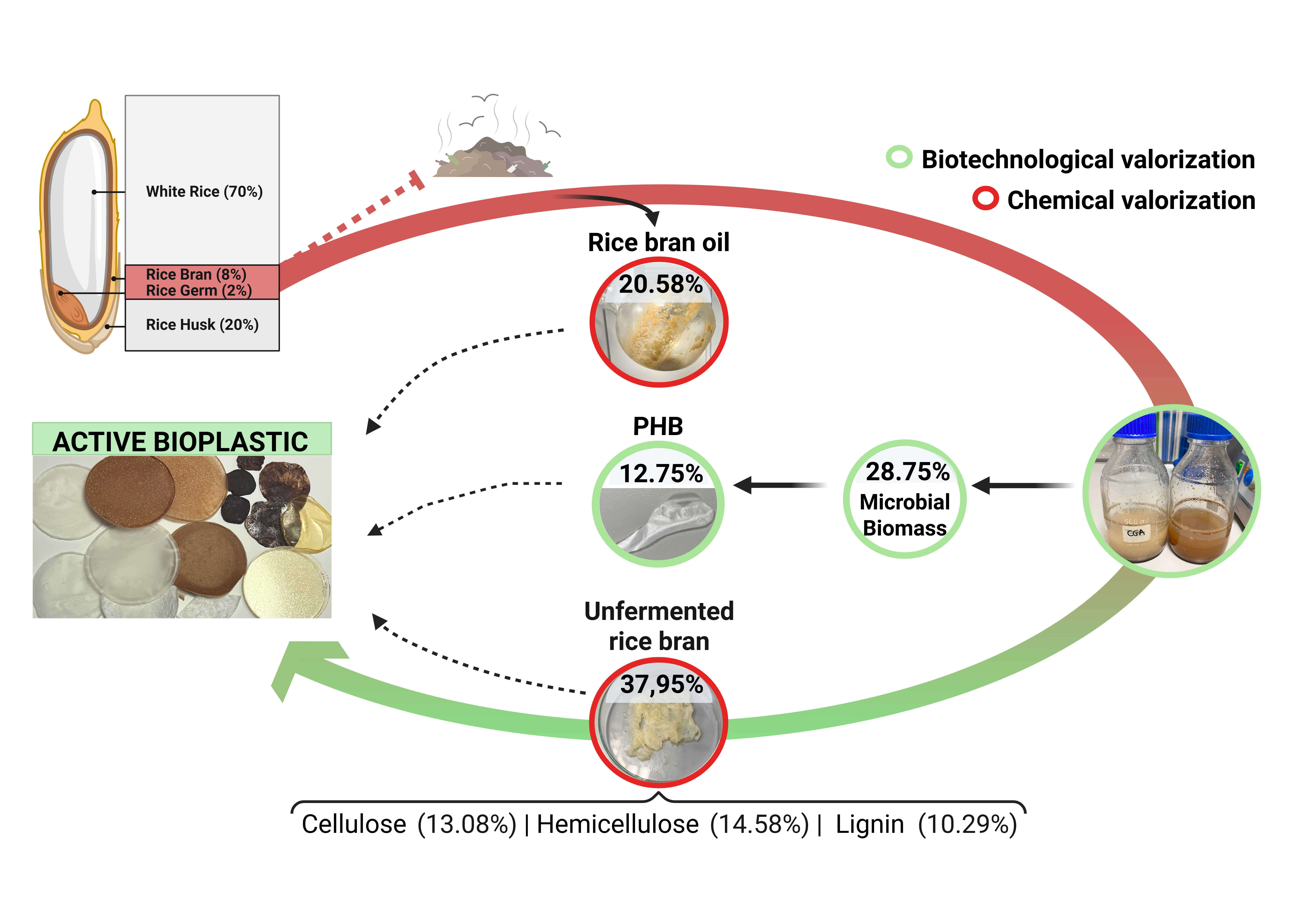

This study aimed to develop a biorefinery model capable of transforming nearly 100% of RB into high-value products, thereby demonstrating its potential as a valuable resource. The model integrates three main processes: extracting RBO to be used as an active ingredient in fruit coatings to reduce postharvest damage; utilising defatted rice bran (d-RB) to decrease the production costs of polyhydroxybutyrate-valerate (PHBV); and recovering cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin from non-assimilated residues of defatted rice bran.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rice Bran Material and Oil Extraction

The RB used as the starting material was obtained from a local supplier in Valencia, Spain, and stored in 1 kg vacuum-packed batches until use. RBO was extracted according to the protocol described by Martillanes et al. (2018), where the optimal extraction conditions were established as follows: 100% ethanol (EtOH) at 60 °C for 97 min.

2.2. Properties of the Rice Bran Oil

As the raw material used was the same as that used by Martillanes et al. (2018) and did not have any extra value in determining the specific profile of bioactive compounds, this study validated the antioxidant activity of RBO following the method described by Turoli et al. (2004) as a tool to verify the effect of storage conditions (20ºC, dark) over the preservation of RB throughout the years.

2.3. In Vitro Evaluation of the Rice Bran Oil

The pathogenic fungi G. candidum and R. stolonifer belong to the private fungal collection of the Biotechnology and Sustainability Department of CICYTEX and were isolated from residual fruits and vegetables. Both microorganisms were cultured on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 5 days at 25ºC. The hyphal solution of G. candidum and spore solution of R. stolonifer required for the assays were obtained by resuspending the contents of the previously cultured plates in 8 mL of Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) (Conda Laboratories, Madrid, Spain) supplemented with the antibiotic chloramphenicol (PanReac AppliChem, Castellar del Vallès, Spain) using a swab. After filtration, the concentration was adjusted to 104 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL using a Neubauer chamber (Brand GmbH + Co KG, Wertheim, Germany).

The antifungal activity of RBO was determined using two different methods. The first was the CFU count, in which 10 µL of the solution of G. candidum hyphae or R. stolonifer spores together with different volumes of RBO (from 10 to 90 µL to G. candidum and from 10 to 70 to R. stolonifer), 1% DMSO (PanReac AppliChem, Castellar del Vallès, Spain), and PDB with chloramphenicol were surface-seeded on rose Bengal plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated for 3 days at 25ºC. Sterile distilled water and 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used as controls. The antifungal activity was determined based on the inhibitory capacity of RBO against fungal growth (summarised in Table 1, Supplementary Material).

The second method involved a linear growth assay. Culture plates were prepared with PDA and a solution containing 1 g RBO, DMSO (0.5 mL DMSO, 4.5 mL glycerol (density 1.26 g/cm3), and 9.5 mL distilled water. A similar mixture was used as a control, but water was substituted for RBO in the case of the white control and ketoconazole (0.1 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, United States) was used as the positive control group. Once the culture plates were prepared, a circular incision of 9 mm in diameter was made in the agar, and a section obtained from the plates containing

G. candidum and

R. stolonifer was seeded on the agar. After three days of incubation at 25 °C, the inhibition ratio was determined using Equation 1. Measures of

in vitro fungal growth on image plates were performed using the software integrated into the automatic colony counter SCAN 500 (Interscience, Saint-Nom-la-Bretêche, France).

where d

o is the diameter of the fungal section, d

c is the diameter of the fungal colony in the blank control, and d

s is the diameter of the fungal colony on the plate with RBO or ketoconazole as a positive control.

2.4. Assessment of Rice Bran Oil for Effective Post-Harvest Disease Control in Grapes and Lemons

The grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) and lemons (Citrus lemon L.) used were commercially ripe. The fruits were disinfected by immersion in 2% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for 5 min and allowed to dry under a laminar-flow hood before use.

After disinfection, the stalks were removed from the grapes, and the lemons were cut into three parts because of their large size. The fruit was immersed in a solution of G. candidum or R. stolonifer spores at a concentration of 5*103-104 CFU/mL. After drying for 10 min, the samples were immersed in a coating solution containing 1%, 3%, or 15% RBO; 4 g soy lecithin (Laguilhoat, Fuenlabrada, Spain) as a compatibiliser; and 100 ml of a solution of a commercial lipophilic carrier without inherent bioactive properties (NATURCOVER M:water = 1:6, v/v) (Decco Ibérica Post Cosecha, S.A., Paterna, Spain), used as a vehicle for RBO inclusion. Water was used as the control. The fruits were incubated for 5 days at 25 °C with 100% relative humidity, and the growth of the fungi in the inoculated area was classified as (rotting-No rotting).

We calculated inhibition as the reduction in rotting compared to the control (water, without RBO) using Equation 2:

For each block of data (each fungus and fruit tested), a linear interpolation was fitted to allow the IC50 to be calculated by linear interpolation instead of sigmoidal interpolation because of the small set of sampling points in each group tested.

2.5. Microbial Production of PHBV by Haloferax Mediterranei

Haloferax mediterranei was selected based on a study by Huang et al. (2006) on the biological production of PHBV through the fermentation of RB and extruded corn starch residue. Initially, H. mediterranei was grown in 200 mL of standardised commercial medium to generate the pre-inoculum and incubated for seven days at 39 °C and 75 rpm in an orbital incubator (Optic Ivymen System). The medium composition included glucose (1 g/L), proteose/peptone (5 g/L), yeast extract (10 g/L), and a Subov salt solution (833 mL) composed of NaCl (234 g/L), MgCl₂·6H₂O, MgSO₄·7H₂O, CaCl₂·2H₂O, KCl (6 g/L), NaHCO₃ (0.2 g/L), NaBr (0.7 g/L), and 9 drops of FeCl₃·6H₂O (5% aqueous solution). After seven days, the culture density was evaluated using a Neubauer chamber. The pre-inoculum, representing 5% of the total volume, was added to a medium in which the carbon source was replaced with d-RB. The culture was grown in batch mode in a glass bioreactor (Applikon Bio 7,5 L) working with a volume of broth (4 L) at 41 °C, with constant aeration through a sparger (Flow 18.6 L/h and Pressure 12 KPa), automatic monitoring, and pH control (Setpoint 6.8, basic solution of 1M NaOH and acidic solution of 1M HCl) for 14 days with an N:C ratio of 0.73. The detailed medium composition included: yeast extract 28.95 g/L, d-RB 21.05 g/L, and salt solution (833 mL) composed of NaCl 234 g/L, MgCl₂·6H₂O 19,5 g/L, MgSO₄·7H₂O 30 g/L, CaCl₂ 1 g/L, KCl 5 g/L, NaHCO₃ 0.2 g/L, NaBr 0.5 g/L.

2.6. PHB Extraction and Purification

The extraction procedure for PHBV was based on the method described by Rawte and Mav (2002). Cell lysis was performed using 2% (w/v) NaClO, and the suspension was incubated in an orbital shaker at 37 °C and 75 rpm. The mixture was then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 20 min at room temperature (RT). After removing the supernatant, the pellet was washed thrice with chloroform (CHCl₃) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), and the organic chloroform fraction was retained. Finally, the chloroform was removed under vacuum using a rotary evaporator. The extraction yields were determined gravimetrically using Equation 3:

where W

dc is the dry weight of the cells and W

PHBV is the weight of the extracted PHBV.

2.7. Lignin, Hemicellulose, and Cellulose from Fermented Rice Bran

The extraction method used to obtain lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose has been described by Xu et al. (2006). The lignin fraction obtained was compared with that obtained using the alkali destructive method of lignin extraction described by [

24]

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed as follows. For the in vitro CFU counting method, model parameter evaluations included normality testing, polynomial fitting, and generation of the corresponding graphical representations. For RBO in vitro linear growth, data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD); after confirming normality, comparisons were performed using the Student’s t-test. For RBO in vivo assays, after confirming normality, data were scaled to the 0–1 range and expressed as percentages; four and five independent experimental units were analysed for lemons and grapes, respectively. PHBV production and the extraction yields of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose are reported as mean ± SD of three independent experimental units. All statistical analyses were performed using Origin 2023 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Properties of Bran Oil

The extraction yield was 20.58%, which is similar to that obtained by Martillanes et al. (2018). Furthermore, the results showed a high total antioxidant activity of 13.32 ± 0.84 mmol Trolox/mL. Validation through antioxidant activity showed that the preservation of the raw material for 6 years in the dark, vacuum-packed, and stored at room temperature preserved the bioactivity of RB (

Table 1).

3.2. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of Bran Oil

The results of the antifungal activity of RBO against

R. stolonifer and

G. candidum based on the CFU count and linear growth are shown in

Figure 1 and 2. Additional details are provided in Figures 1–6 in the Supplementary Material.

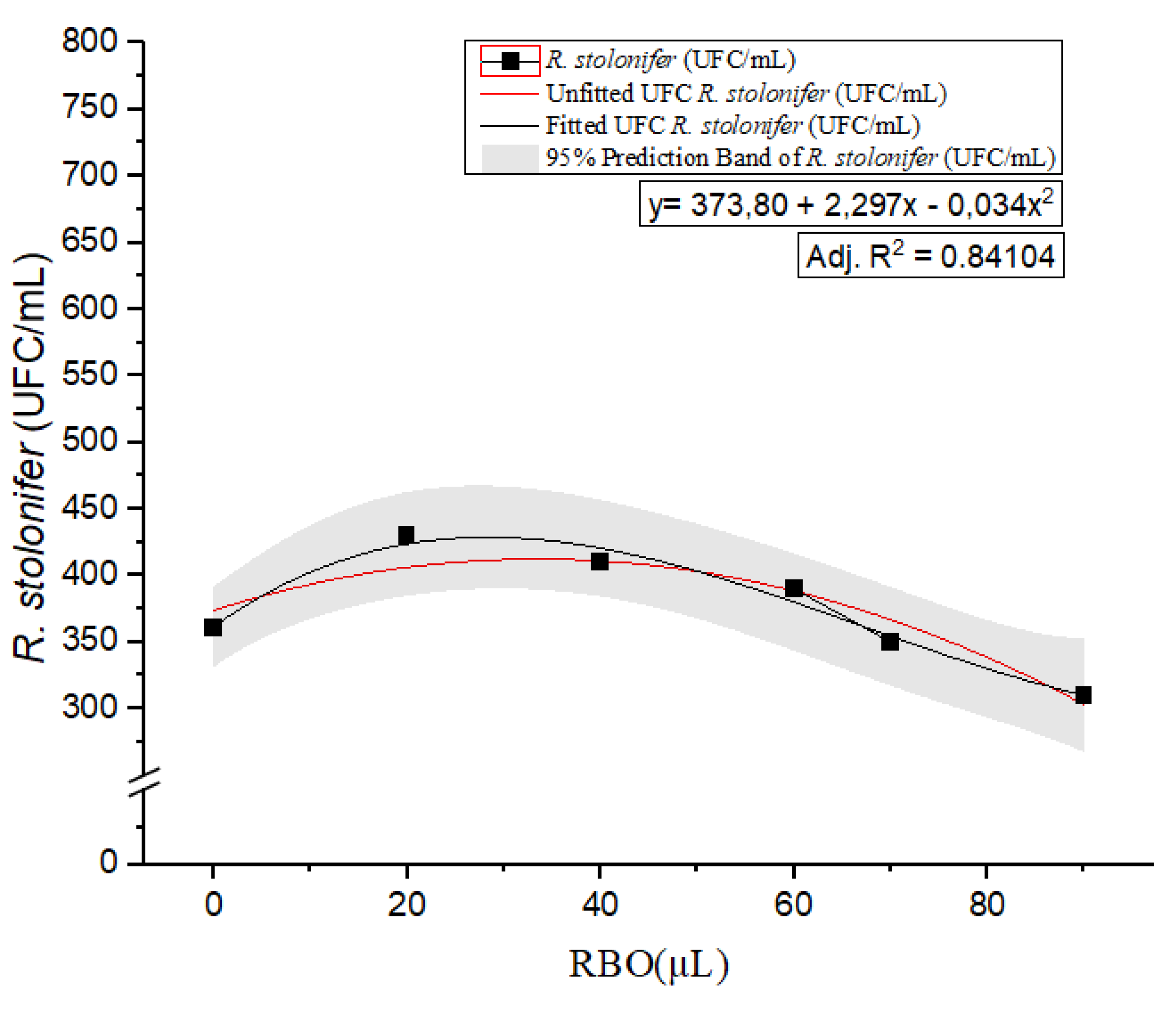

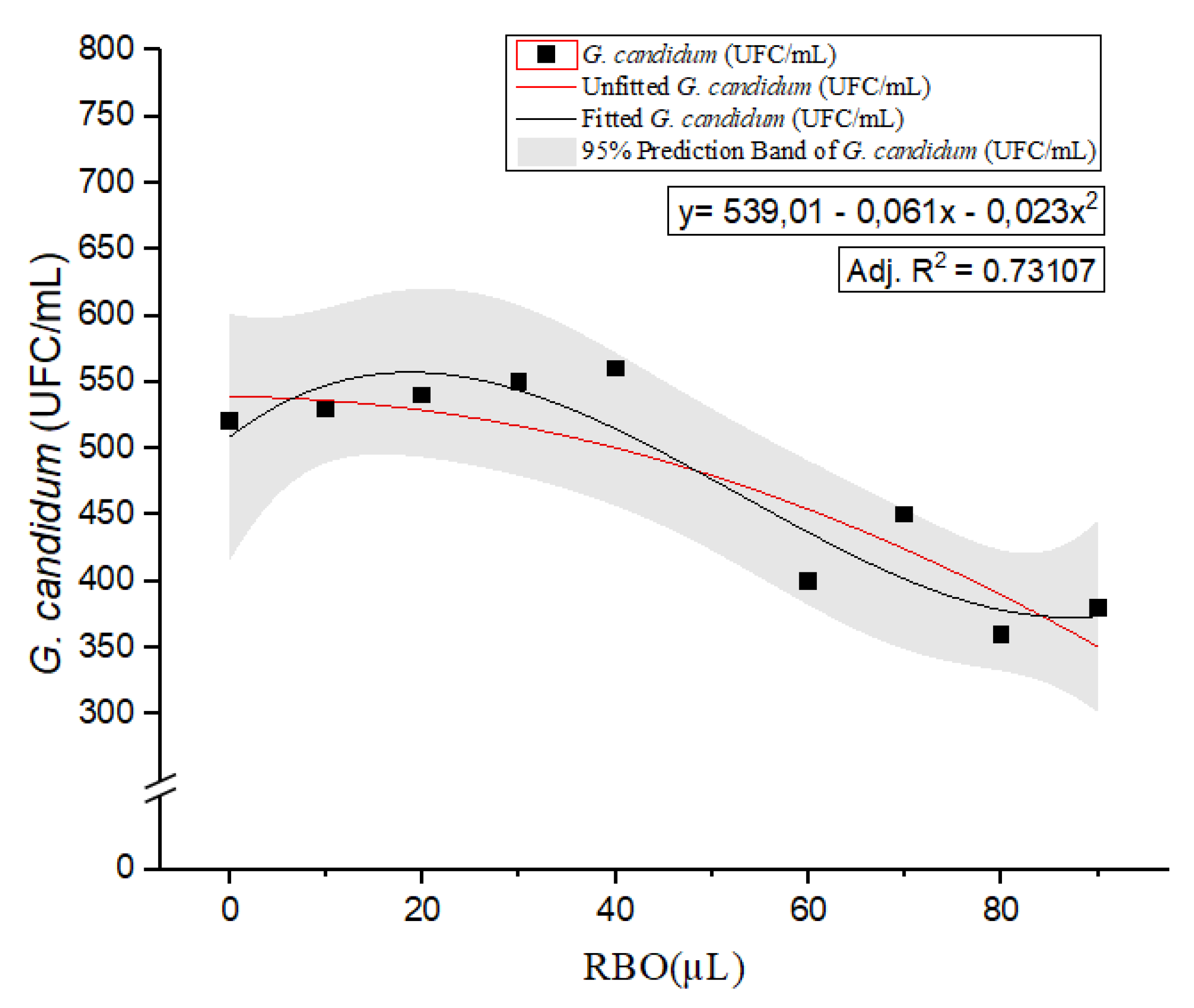

First, the effect of RBO on the growth of

Geotrichum candidum and

Rhizopus stolonifer was assessed by evaluating the CFU over a concentration gradient. The data shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 adhered to a normal distribution. In addition, no significant differences were observed between the water and DMSO controls, indicating that 1% DMSO did not inhibit fungal growth.

For

G. candidum (

Figure 1), the CFU count showed a slight but consistent decrease with increasing RBO concentration. The fitted quadratic regression model y= 539.01 - 0.061x − 0.023x

2 yielded an adjusted R

2 of 0.73107, suggesting a moderate correlation between RBO concentration and fungal growth inhibition. By setting the first derivative to zero to locate the maximum of the curve, we calculated the peak value at approximately 14.05 µL of RBO. This point indicates a threshold beyond which further increases in RBO concentration result in a decrease in

G. candidum CFU per mL. These findings suggest that RBO concentrations above this threshold may exert an inhibitory effect on

G. candidum, potentially reducing its growth and viability. However, given the R² value, instead of validating the addition of 14.05 µL, 10 and 20 µL were validated. The observed growth inhibition did not align with the model’s prediction, resulting in

G. candidum growth at all studied values (Supplementary Material, Figure 4, images C and D).

Similarly, for

R. stolonifer (

Figure 2), the CFU counts initially increased slightly before declining at higher RBO concentrations. The quadratic regression model y= 373.80 + 2. 297x − 0.034x

2 provided a higher adjusted R

2 of 0.84104, indicating a stronger fit than the first-order model. The calculated peak CFU, obtained by setting the first derivative to zero, was approximately 34.05 µL of RBO. This concentration appears to represent a threshold for

R. stolonifer growth, beyond which RBO begins to inhibit its proliferation. Similar to the

G. candidum validation, we decided to validate 30 and 40 µL instead of the 34.05 µL suggested by the model due to R

2. In this case, the results were satisfactory, with counts of 0 in both samples. This adjustment aligned the validation with the model (Supplementary Material, Figure 4, images A and B).

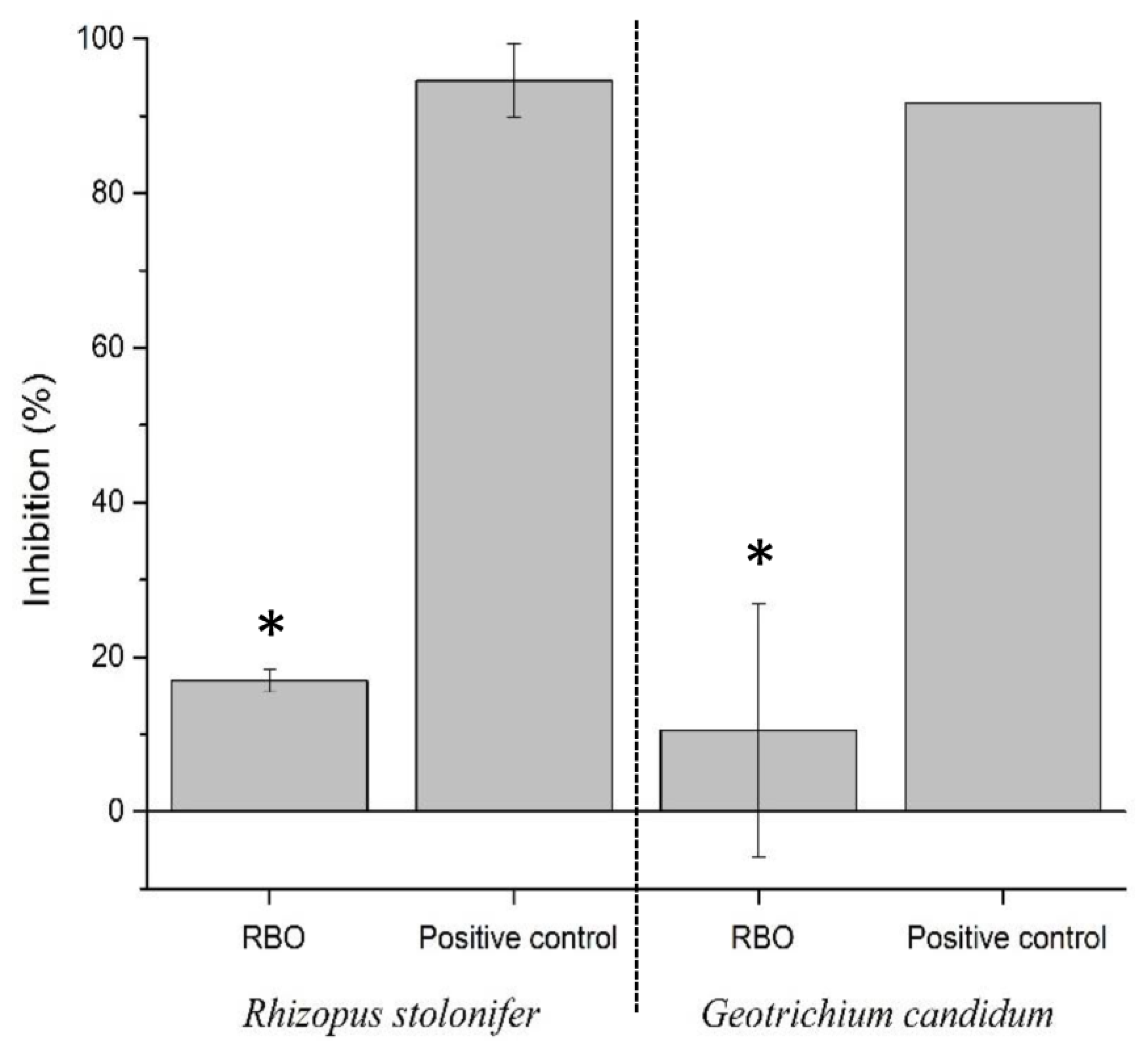

Regarding the evaluation of linear growth (

Figure 3), the antifungal efficacy of RBO at a final concentration of 3% was evaluated against

Rhizopus stolonifer and Geotrichum candidum, and the inhibition percentages were compared with those obtained by substituting RBO with an antifungal agent (positive control).

For R. stolonifer, the inhibition achieved by RBO was approximately 20%, whereas the positive control displayed an inhibition of nearly 100%, indicating complete suppression of fungal growth. Similarly, for G. candidum, RBO showed an inhibition of approximately 5%, whereas the positive control showed close to 100% inhibition. Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences in the inhibition rates between RBO and the antifungal control for both the fungal species.

3.3. In Vivo Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of Bran Oil

The in vivo activity of RBO against R. stolonifer and G. candidum was evaluated using grapes and lemons. As shown in Figure 4, in the case of grapes, treatment with 1% RBO did not reduce the percentage of grapes in rotten condition compared to the control, but higher concentrations of the oil reduced the growth of the fungus. With the 3% RBO treatment, 60% of the grapes remained non-rotting. The calculated IC₅₀ values indicated that approximately 2.67% RBO is required to inhibit 50% of R. stolonifer growth on grapes. In the case of lemons infected with R. stolonifer, none of the RBO treatments sufficiently reduced the number of lemons in a rotting condition, and the IC₅₀ was estimated to be above the tested concentration range (>15% RBO).

In fruits infected with G. candidum, RBO considerably decreased the growth of this fungus. The percentage of fruit in a rotting condition ranged from 60% in the control treatment to 20% using 1% and 3% RBO, with an estimated IC₅₀ of less than 1% RBO for grapes. For lemons, the percentage of G. candidum rot decreased as the RBO concentration increased: 100% for the water control, 75% for the 1% RBO treatment, and 50% for the 3% RBO treatment, yielding an IC₅₀ of approximately 3% RBO. Additional details are provided in Figures 7–10 in the Supplementary Material.

3.4. PHB Production with Haloferax Mediterranei

In the second phase of cascade valorization, the leftover solid waste from RBO extraction was used as a carbon source to produce PHBV through fermentation. After 14 days, d-RB was extensively digested with Haloferax mediterranei deposited on the undigested RB at the bottom of the reactor. The pH adjustment data showed that to maintain the pH at SetPoint 6.8, 197.2 mL of 1M NaOH was added over 14 days. Additional details are provided in Figures 11-12A in the supplementary material.

3.5. PHB Extraction and Purification

Gravimetric quantification performed from the crude culture broth yielded 4.18 ± 0.678 g of wet biomass and 0.77 ± 0.085 g of dry biomass from 63.64 g of culture broth. As for PHB production, 0.2366 g of PHB was obtained, which represents 0.37% of the fermented raw broth, 5.66% in terms of wet biomass, and 30.73% in terms of dry biomass. The removal of chloroform generated a very thin and brittle PHB film (Figure 12B; Supplementary Material).

3.6. Lignin, Hemicellulose and Cellulose Extraction Yield from Digested Rice Bran

The serial extraction method allowed the recovery of 1.6465 ± 0.015 g cellulose (16.46%), 1.8310 ± 0.1827 g hemicellulose (18.31%), and 1.297 ± 0.073 g lignin (12.97%) from 10 g defatted and unfermented RB. In contrast, the alkali method (destructive) yielded 0.4993 g of lignin (9.80%) from 5.002 g of the sample.

4. Discussion

4.1. Extraction, in Vitro Validation, and Application of the Crude Rice Bran Extract in Edible Coatings

As shown in

Table 1, the results indicate that proper storage of RB under vacuum at room temperature maintains its oil bioactivity over long periods, in contrast to previous studies that suggested treatments such as infrared radiation, dry heat, microwave, or low-temperature storage to prevent rapid oxidation [

25,

26,

27]. This stability emphasises the influence of factors such as variety, origin, harvest season, and extraction methods on RBO’s bioactive properties of RBO [

28].

Table 1.

Overview of RBO extraction methods, antioxidant activity (ABTS), and source details from various studies.

Table 1.

Overview of RBO extraction methods, antioxidant activity (ABTS), and source details from various studies.

| Origin and year of harvest |

Variety |

Year of RBO extraction |

Extraction Process |

Antioxidant activity by ABTS assay |

SD |

Research |

| Valencia (Spain), 2018 |

Seria (Senia-Bahia) |

2018 |

Ethanolic extraction |

1.47 (mg TEAC/g DW of RB) |

- |

[9] |

| Valencia (Spain), 2018 |

Seria (Senia-Bahia) |

2024 |

Ethanolic extraction |

13.32 (mmol Trolox/mL of RBO oil)

|

0.84 |

Our research |

| Chumphon (Thailand), 2014 |

Dok-kham |

2014 |

Ethanolic extraction |

34.94 (mg TEAC/g DW of RB) |

1.26 |

[59] |

| Phang-nga (Thailand), 2014 |

Dok-kha |

8.36 (mg TEAC/g DW of RB) |

1.04 |

| Satum (Thailand), 2014 |

Khem-ngen |

7.23 (mg TEAC/g DW of RB) |

0.27 |

| Chumphon (Thailand), 2014 |

Nang-dam |

3.73 (mg TEAC/g DW of RB) |

0.19 |

| China, 2019 |

Oryza sativa L. Varieties: Nanjing, Wuyoudao, Yanfeng, Suijing, Longjing |

2021 |

N’Hexane extraction assisted by ultrasonic |

1592.38-2106.47 µmol TEAC/100 g |

NA |

[60] |

The antifungal activity of RBO exhibited different levels of inhibition depending on the fungal species and conditions, confirming its possible role as a natural alternative to protect fruits from postharvest damage. The

in vitro assays highlighted effective concentrations for inhibiting fungal growth: for

G. candidum, our model indicated an inhibitory effect at approximately 14.05 µL of RBO, where concentrations above this point significantly reduced CFU. In the case of

R. stolonifer, a stronger correlation was observed, with a peak effect at 34.05 µL of RBO, indicating a threshold for inhibition. It should be noted that the doses used are intentionally higher than the endogenous levels of antimicrobial phytochemicals typically present in fresh fruit tissues and, as is customary in plant antimicrobial studies, exceed naturally occurring (and often sensorially acceptable) concentrations in foods to overcome matrix effects [

29,

30]. Furthermore, our bioassay with lemons and grapes used open/wounded fruit, which removes the main natural resistance barriers (cuticle and cell wall/waxes) and increases susceptibility to infection by wound pathogens [

31,

32]. Therefore, the activity observed under these conditions is likely a conservative estimate and may underestimate the efficacy in intact, unwounded fruit.

Although the differences between both fungi are significant, the antifungal activity of RBO against both

R. stolonifer and

G. candidum appears to result from direct contact with the functional compounds of the oil, particularly oryzanols. Family of oryzanols may disrupt the electron transport chain in fungal cells, leading to a loss of proton motive force, reduced ATP synthase activity, and decreased cell viability [

33,

34]. Additionally, RBO polyphenols can interact with microbial cell membranes and cause structural alterations [

35]. Our findings are consistent with previous theoretical explanations and the demonstrated antifungal activity of RBO against other fungi, such as

Rhizoctonia solani,

Pyricularia oryzae,

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, and

Fusarium graminearum [

36].

Figure 6 (Supplementary Material) illustrates how an increase in concentration affects fungal morphology, with direct contact with RBO disrupting growth, particularly in

G. candidum. These macroscopic changes align with the previously described actions of plant antimicrobials (membrane disruption, oxidative stress, and impaired β-glucan/chitin remodelling), leading to hyphal collapse and surface roughening [

37]. This is also consistent with recent SEM studies reporting membrane and cell wall damage and deformed, shrunken hyphae after exposure to botanical extracts or essential oils [

38],mirroring our macroscopic observations. In contrast, it was challenging to make similar observations for

R. stolonifer because its aerial structures hide the agar surface. Furthermore, as shown in the images in Figure 5 (Supplementary Material), challenges were encountered in achieving a homogeneous dispersion of RBO in the solid PDA medium used for fungal cultivation. The lipophilic nature of RBO complicates its distribution within the hydrophilic agar structure. Although the addition of DMSO and glycerol improved dispersion, it remained uneven, indicating that standard

in vitro methods may need refinement to achieve more accurate CFU counts when evaluating lipophilic compounds.

Overall, the results obtained using the proposed methodology allowed us to adjust the data through polynomial regression, which can guide the selection of the optimal concentration for in vivo trials. Our model suggests that a range of 3-5% RBO (oil/coating) is likely to achieve significant reductions in fungal growth.

Our in vivo tests demonstrated the greater antifungal efficacy of a commercial cover with 3% RBO, inhibiting both R. stolonifer and G. candidum on grapes and lemons. The rough texture of the fruits likely facilitated the immobilisation of the RBO coating, enhancing its antifungal properties and minimising the repulsive forces between hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds. As shown in Figure 4, in grapes, a coating with 3% RBO preserved 60% of the fruits in a non-rotting state, with IC₅₀ values of 2.67% for R. stolonifer and less than 1% for G. candidum. In contrast, lemons required higher concentrations of RBO, with an IC₅₀ of 3% for G. candidum and over 15% for R. stolonifer, indicating that the efficacy of RBO varies depending on the fruit type and fungal species (additional information can be found in Figures 7–10 of the supplementary material).

Traditionally, fruit coatings are designed to effectively reduce water loss, gas exchange, and respiration, thereby extending the shelf life of the fruit (Aloui et al., 2014; Rojas-Graü et al., 2009. Our

in vivo results suggest that the lipophilic matrix with RBO not only creates a uniform protective layer on the fruit but also adds an active function to traditional formulations, protecting against postharvest damage. Thus, our active coating shows results consistent with research on essential oils, such as those using alginate with grapefruit seed extract, which has demonstrated efficacy against postharvest fungi, such as

Penicillium digitatum [

39,

41].

4.2. Biological Production of PHB(V) from Defatted Rice Bran

In the second valorization step, owing to the high production costs of bio-based plastics such as PHBV [

15,

16], our research incorporates their production into biorefinery models. This approach aims to offset losses with the benefits gained in the earlier stages while reducing input costs by using d-RB as a replacement for commercial carbon sources. Building on previous research [

18,

42], our study achieved a 47% yield of PHB compared to the results of Huang et al. (2006) which were based on a fed-batch process using an RB and cornstarch mixture (in a 1:8 ratio). Differences in yield may be attributed to various factors, such as the use of different carbon sources [

43] and the absence of specific stress induction in our process, such as N starvation [

44]. Additionally, variations in the results might be explained by the potential degradation occurring between 120 and 336 h of culture, as described in previous studies on

Cupriavidus necator [

45].

For extraction and purification, our study also indicated that, consistent with Koller et al. (2015), storing the culture in cold conditions and analysing it after 12 days yielded results similar to those obtained immediately after the culture ended. This suggests that the process is effective for extracting and purifying PHBV owing to the low rate of degradation and simplicity of the extraction process, in which

H. mediterranei is inactivated after fermentation [

46]. The extraction process is simple and environmentally friendly, taking advantage of the extreme salinity conditions of fermentation. Dilution with tap water causes cell rupture by osmotic shock, facilitating the extraction of the desired compounds and eliminating the need for harsh chemicals or complex procedures, as previously reported [

47]. However, to align the process with green chemistry trends, there is an urgent need to eliminate the use of halogenated solvents such as chloroform in favour of green solvents or extraction techniques.

Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether using d-RB as a carbon source leads to higher PHBV yields than using non-defatted sources.

4.3. Lignin, Cellulose, and Hemicellulose from Defatted and Fermented Rice Bran

In the last step of our biorefinery model, by extracting lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, the proposed biorefinery model provides a solution for handling almost all initial RB.

Through serial extraction, 30% less cellulose was obtained than that in the characterisation studies of [

28,

48]. However, the result is positive, since the differences can be explained by losses across biological degradation during cultivation with

Haloferax mediterranei, a desirable effect indicating that our substrate-conditioning route improves bioaccessibility for the inoculated microorganism, consistent with reports of cellulose/hemicellulose depletion during microbial fermentation [

49].The same is true for holocellulose, which is based on sugars and is very likely to have reduced its volume after fermentation [

49]. However, holocellulose should be interpreted more broadly, as lignin content, structure, and lignin–carbohydrate complexes strongly govern carbohydrate accessibility and hydrolysis, complicating cross-study comparisons [

50]. As indicated by Casas et al. (2019), depending on the hydrolytic process, an important part of both fractions can adhere to each other via covalent bonds; therefore, their quantification and purification are very complex, explaining the 32% difference between the evaluated lignin extraction processes.

4.4. Biorefineries

Biorefineries and biofoundries are essential climate tools that are needed now more than ever. The fight against climate change demands faster and smarter solutions, and biorefineries and biofoundries are stepping up. These advanced facilities transform waste, such as agricultural byproducts into sustainable alternatives. Consequently, investment in biorefineries and/or biofoundries is growing worldwide as their potential becomes undeniable[

52,

53]. These facilities are no longer niche research projects but are rapidly becoming essential tools in the global effort to achieve sustainability targets. The ultimate goal is to harness cutting-edge science and automation to develop real and scalable solutions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions while creating economic value. Our research (summarised in Figure 5), like that of others (Casa et al., 2021), reimagines agroindustrial waste (RB) into valuable materials and products (RBO, PHBV, Biomass, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin). By integrating chemical processes with microorganism fermentation, we can efficiently and sustainably address climate change at its root and generate economic profit.

To provide a rough estimate, if we scale our observed yields to 1 ton of rice bran and assess each fraction based on current market values (the calculation considered 1 US

$ ≈ €0.95), the potential gross revenue per product could be: rice bran oil (20.6%) €1,100; PHB (12.8%) €490-730[

54]; microbial biomass (28.8%) €190-270 for feed-grade or €1,000-1,440 for premium SCP[

55]; cellulose (13.1%) €75[

56]; hemicelluloses (14.6%) €70-80 if sold as glucose syrup or €2,770-5,540 as XOS[

56,

57]; and lignin (10.3%) €30-70[

58]. Depending on the product combination, total revenue per ton can vary significantly: in a conservative scenario (feed-grade biomass + hemicelluloses as syrup), it is €1,950, while in an optimistic scenario (premium SCP + XOS), it can reach €8,950 per ton. These figures are only indicative: they do not account for CAPEX/OPEX, energy, stabilization/handling, and logistics, and they are highly sensitive to product purity/quality and end use.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the economic and ecological potential of the proposed cascade valorization model for RB. The extracted RBO exhibited significant antifungal properties, effectively inhibiting Geotrichum candidum and Rhizopus stolonifer in both in vitro and in vivo assays (The data obtained are of considerable industrial applicability; however, due to limited availability, the experimental design is inadequate, and the data cannot be considered conclusive. Corroboration of these exploratory observations requires implementing an appropriate experimental design with a sufficient sample size to robustly verify the findings of this study). The production of PHBV from d-RB yielded promising results, and the extraction of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose contributed to the advancement of our biorefinery model. Crucially, this study illustrates that adopting integrated approaches for managing agricultural waste from current agro-industrial activities allows nearly complete conversion of RB into high-value compounds. The use of RBO for postharvest treatment, the creation of bioplastics such as PHBV, and the extraction of valuable polymers such as cellulose and lignin demonstrate that sustainable resource management can yield environmental, social, and economic benefits while also having a significant impact on other industries. Finally, although the model shows great potential, further optimisation is required to enhance its efficiency and minimise the use of toxic reagents. This study emphasises that the agro-industrial sector should embrace this approach for more effective resource management and sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Bruno Navajas Preciado: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualisation. Sara Martillanes Costumero: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualisation. Almudena Galván: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft. Javier Rocha Pimienta: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization. Rosario Ramírez: Resources, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding acquisition. Jonathan Delgado Adámez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The authors thank the PID project, which was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Operational Program for Extremadura (PID2020-119608RR-100). This study forms part of the AGROALNEXT programme and was supported by MCIN with funding from European Union NextGenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1). B. Navajas offers thanks for Grant PRE2021-097773, funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and “ESF Investing in your future”.

Declaration of conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- G20 G20 OSAKA LEADERS’ DECLARATION. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/g20_summit/osaka19/en/documents/final_g20_osaka_leaders_declaration.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Qiao, H.; Zheng, F.; Jiang, H.; Dong, K. The Greenhouse Effect of the Agriculture-Economic Growth-Renewable Energy Nexus: Evidence from G20 Countries. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 671, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makepa, D.C.; Chihobo, C.H. Barriers to Commercial Deployment of Biorefineries: A Multi-Faceted Review of Obstacles across the Innovation Chain. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Almada, D.; Galán-Martín, Á.; Contreras, M. del M.; Castro, E. Integrated Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessment of Biorefineries: Review and Future Research Directions. Sustain Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 4031–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, B.O.; Tuaño, A.P.P. Gross Structure and Composition of the Rice Grain. In Rice: Chemistry and Technology; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 31–53. ISBN 9780128115084. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, S.B.; Mondal, R.; Mandi, S.K. Crop Residue Management Options in Rice–Rice System: A Review. Arch Agron Soil Sci 2020, 66, 1218–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, U.; Thongsook, T. Extraction and Utilization of Rice Bran Oil: A Review; 2017.

- Kumar, P.; Yadav, D.; Kumar, P.; Panesar, P.S.; Bunkar, D.S.; Mishra, D.; Chopra, H.K. Comparative Study on Conventional, Ultrasonication and Microwave Assisted Extraction of γ-Oryzanol from Rice Bran. J Food Sci Technol 2016, 53, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martillanes, S.; Ayuso-Yuste, M.C.; Gil, M.V.; Manzano-Durán, R.; Delgado-Adámez, J. Bioavailability, Composition and Functional Characterization of Extracts from Oryza Sativa L. Bran. Food Research International 2018, 111, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, J.B.; Cho, S.-M.; Cho, I.K.; Li, Q.X.; Jang, H.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-M.; Hwang, K.-A. Characterization and Quantification of γ-Oryzanol in Grains of 16 Korean Rice Varieties. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2015, 66, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martillanes, S.; Rocha-Pimienta, J.; Gil, M.V.; Ayuso-Yuste, M.C.; Delgado-Adámez, J. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Rice Bran (Oryza Sativa L.) Extracts in a Mayonnaise-Type Emulsion. Food Chem 2020, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-Y.; Lee, K.-W.; Choi, H.-D. Rice Bran Constituents: Immunomodulatory and Therapeutic Activities. Food Funct 2017, 8, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danso, D.; Chow, J.; Streita, W.R. Plastics: Environmental and Biotechnological Perspectives on Microbial Degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawecki, D.; Nowack, B. Polymer-Specific Modeling of the Environmental Emissions of Seven Commodity Plastics As Macro- and Microplastics. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 9664–9676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, S.; Massaglia, S.; Brun, F.; Peano, C.; Mosso, A.; Giuggioli, N.R. Use of Bio-Based Plastics in the Fruit Supply Chain: An Integrated Approach to Assess Environmental, Economic, and Social Sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Production of Sustainable and Biodegradable Polymers from Agricultural Waste. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, Y.F.; Kumar, V.; Samadar, P.; Yang, Y.; Lee, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Song, H.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, E.E.; Jeon, Y.J. Production of Bioplastic through Food Waste Valorization. Environ Int 2019, 127, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.Y.; Duan, K.J.; Huang, S.Y.; Chen, C.W. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates from Inexpensive Extruded Rice Bran and Starch by Haloferax Mediterranei. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2006, 33, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, P. V.; Gando-Ferreira, L.M.; Quina, M.J. Tomato Residue Management from a Biorefinery Perspective and towards a Circular Economy. Foods 2024, 13, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, M.; Miccio, M.; De Feo, G.; Paulillo, A.; Chirone, R.; Paulillo, D.; Lettieri, P.; Chirone, R. A Brief Overview on Valorization of Industrial Tomato By-Products Using the Biorefinery Cascade Approach. Detritus 2021, 15, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoli, D.; Testolin, G.; Zanini, R.; Bellù, R. Determination of Oxidative Status in Breast and Formula Milk. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics 2004, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawte, T.; Mav, S. A Rapid Hypochlorite Method for Extraction of Polyhydroxy Alkanoates from Bacterial Cells; 2002; Vol. 40.

- Xu, F.; Sun, J.X.; Sun, R.; Fowler, P.; Baird, M.S. Comparative Study of Organosolv Lignins from Wheat Straw. Ind Crops Prod 2006, 23, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Coronado, M.J.; Hernández, M.; Centenera, F.; Pérez-Leblic, M.I.; Ball, A.S.; Arias, M.E. Chemical Characterization and Spectroscopic Analysis of the Solubilization Products from Wheat Straw Produced by Streptomyces Strains Grown in Solid-State Fermentation. Microbiology (N Y) 1997, 143, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanzadeh, F.M.; Rao, R.M.; Windhauser, M.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Marshall, W.E. Prevention of Oxidative Rancidity in Rice Bran during Storage. J Agric Food Chem 1999, 47, 2997–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, C.; Wu, Y.; Ju, X. Storage Characteristics of Infrared Radiation Stabilized Rice Bran and Its Shelf-life Evaluation by Prediction Modeling. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 2638–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.T.; Liu, K.; Han, S.; Jatoi, M.A. The Effects of Thermal Treatment on Lipid Oxidation, Protein Changes, and Storage Stabilization of Rice Bran. Foods 2022, 11, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yi, C.; Quan, K.; Lin, B. Chemical Composition, Structure, Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Rice Bran Dietary Fiber Modified by Cellulase Treatment. Food Chem 2021, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshirvani, N. Essential Oils as Natural Food Preservatives: Special Emphasis on Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities. J Food Qual 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Guha, P. A Review on Antifungal Activity and Mode of Action of Essential Oils and Their Delivery as Nano-Sized Oil Droplets in Food System. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 4701–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Du, Y.; Jiao, W.; Sun, F.; Fu, M. Rhizopus Stolonifer and Related Control Strategies in Postharvest Fruit: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, G.; Chen, T.; Tian, S. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Multi-Level Defense Responses of Horticultural Crops to Fungal Pathogens. Hortic Res 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P. Coupling of Phosphorylation to Electron and Hydrogen Transfer by a Chemi-Osmotic Type of Mechanism. Nature 1961, 191, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, D.; Gibbons, C.; Arechaga, I.; Leslie, A.G.W.; Walker, J.E. The Rotary Mechanism of ATP Synthase. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2000, 10, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W. Application of Edible Coating with Essential Oil in Food Preservation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xi, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Che, F.; Gu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y. Isolation of Four Major Compounds of γ-Oryzanol from Rice Bran Oil by Ionic Liquids Modified High-Speed Countercurrent Chromatography and Antimicrobial Activity and Neuroprotective Effect of Cycloartenyl Ferulate In Vitro. Chromatographia 2021, 84, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.; Li, F. Antifungal Mechanism of Natural Products Derived from Plants: A Review. Nat Prod Commun 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K.H.; Khorshidi, J.; Vafaee, Y.; Rastegar, A.; Morshedloo, M.R.; Hossaini, S. Phytochemical Profile and Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils Obtained from Different Mentha Longifolia L. Accessions Growing Wild in Iran and Iraq. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloui, H.; Khwaldia, K.; Sánchez-González, L.; Muneret, L.; Jeandel, C.; Hamdi, M.; Desobry, S. Alginate Coatings Containing Grapefruit Essential Oil or Grapefruit Seed Extract for Grapes Preservation. Int J Food Sci Technol 2014, 49, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Graü, M.A.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Edible Coatings to Incorporate Active Ingredients to Fresh-Cut Fruits: A Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2009, 20, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Parisi, M.C.M.; Baggio, J.S.; Silva, P.P.M.; Paviani, B.; Spoto, M.H.F.; Gloria, E.M. Control of Rhizopus Stolonifer in Strawberries by the Combination of Essential Oil with Carboxymethylcellulose. Int J Food Microbiol 2019, 292, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, M.; Chiellini, E.; Braunegg, G. Study on the Production and Re-Use of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) and Extracellular Polysaccharide by the Archaeon Haloferax Mediterranei Strain DSM 1411. Chem Biochem Eng Q 2015, 29, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.Y.; Hussin, M.H.; Baidurah, S. Biosynthesis of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) by Cupriavidus Necator from Various Pretreated Molasses as Carbon Source. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2019, 17, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, A.; Spatola Rossi, T.; Morlino, M.S.; Gupte, A.P.; Favaro, L.; Morosinotto, T.; Treu, L.; Campanaro, S. Autotrophic Poly-3-Hydroxybutyrate Accumulation in Cupriavidus Necator for Sustainable Bioplastic Production Triggered by Nutrient Starvation. Bioresour Technol 2024, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, D.; Yashchuk, O.; Noseda, D.G.; Araoz, B.; Hermida, É.B. Improved Fermentation Strategies in a Bioreactor for Enhancing Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) Production by Wild Type Cupriavidus Necator from Fructose. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlacek, P.; Slaninova, E.; Koller, M.; Nebesarova, J.; Marova, I.; Krzyzanek, V.; Obruca, S. PHA Granules Help Bacterial Cells to Preserve Cell Integrity When Exposed to Sudden Osmotic Imbalances. N Biotechnol 2019, 49, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, E.A.; Levin, P.A. Bacterial Cell Wall Quality Control during Environmental Stress; 2020.

- Arun, V.; Perumal, E.M.; Prakash, K.A.; Rajesh, M.; Tamilarasan, K. Sequential Fractionation and Characterization of Lignin and Cellulose Fiber from Waste Rice Bran. J Environ Chem Eng 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, W.; Song, L.; Guo, Z.; Bian, Z.; Han, Y.; Cai, H.; Yang, P.; Meng, K. The Potential of Trichoderma Asperellum for Degrading Wheat Straw and Its Key Genes in Lignocellulose Degradation. Front Microbiol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, D.; Leitch, M.; Fatehi, P. Lignin-Carbohydrate Complexes: Properties, Applications, Analyses, and Methods of Extraction: A Review. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, G.A.; Lærke, H.N.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Stein, H.H. Arabinoxylan Is the Main Polysaccharide in Fiber from Rice Coproducts, and Increased Concentration of Fiber Decreases in Vitro Digestibility of Dry Matter. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2019, 247, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Sindhu, R.; Sirohi, R.; Kumar, V.; Ahluwalia, V.; Binod, P.; Juneja, A.; Kumar, D.; Yan, B.; Sarsaiya, S.; et al. Agricultural Waste Biorefinery Development towards Circular Bioeconomy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, J.; Rajauria, G.; McMahon, H.; Ravindran, R.; Dominguez, C.; Ambye-Jensen, M.; Souza, M.F.; Meers, E.; Aragonés, M.M.; Skunca, D.; et al. Green Biorefinery Systems for the Production of Climate-Smart Sustainable Products from Grasses, Legumes and Green Crop Residues. Biotechnol Adv 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaim, R.; Unis, R.; Gnayem, N.; Gozin, M.; Gnaim, J.; Golberg, A. Techno-Economic Analysis of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Production Using Cobetia Amphilecti from Celery Waste. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2025, 150, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QY RESEARCH Single-Cell Bacterial Proteins - Global Market Share and Ranking, Overall Sales and Demand Forecast 2025-2031. Available online: https://www.qyresearch.com/sample/4935587 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- ENCE First Quarter 2025 Earnings Report; 2025.

- Chemanalyst Liquid Glucose Price Trend and Forecast. Available online: https://www.chemanalyst.com/Pricing-data/liquid-glucose-1593 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Correa-Guillen, E.; Henn, K.A.; Österberg, M.; Dessbesell, L. Lignin’s Role in the Beginning of the End of the Fossil Resources Era: A Panorama of Lignin Supply, Economic and Market Potential. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2025, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruen-ngam, D.; Thawai, C.; Sukonthamut, S.; Nokkoul, R.; Tadtong, S. Evaluation of Nutrient Content and Antioxidant, Neuritogenic, and Neuroprotective Activities of Upland Rice Bran Oil. ScienceAsia 2018, 44, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; Wang, Y.; Shang, B.; Liu, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y. A Comparative Investigation on Physicochemical Properties, Chemical Composition, and in Vitro Antioxidant Activities of Rice Bran Oils from Different Japonica Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Varieties. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2021, 15, 2064–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).