Submitted:

12 December 2023

Posted:

13 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

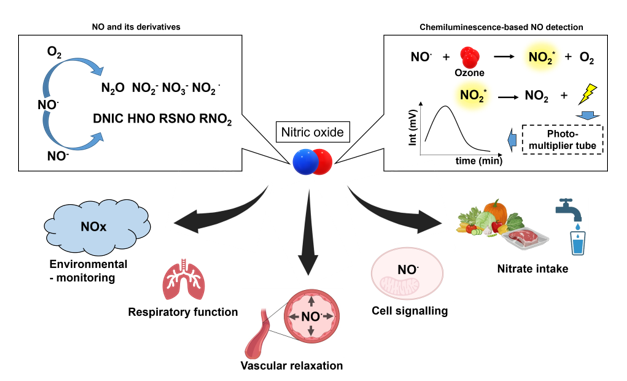

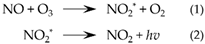

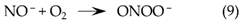

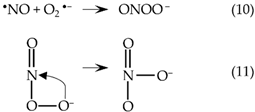

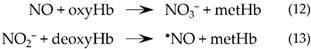

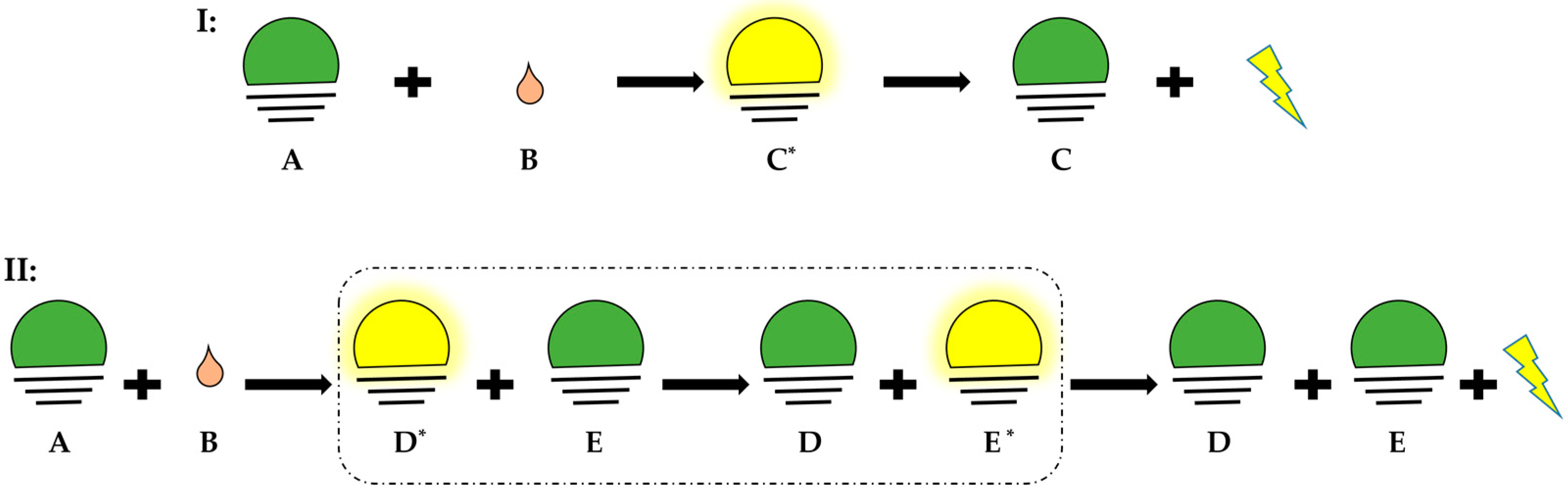

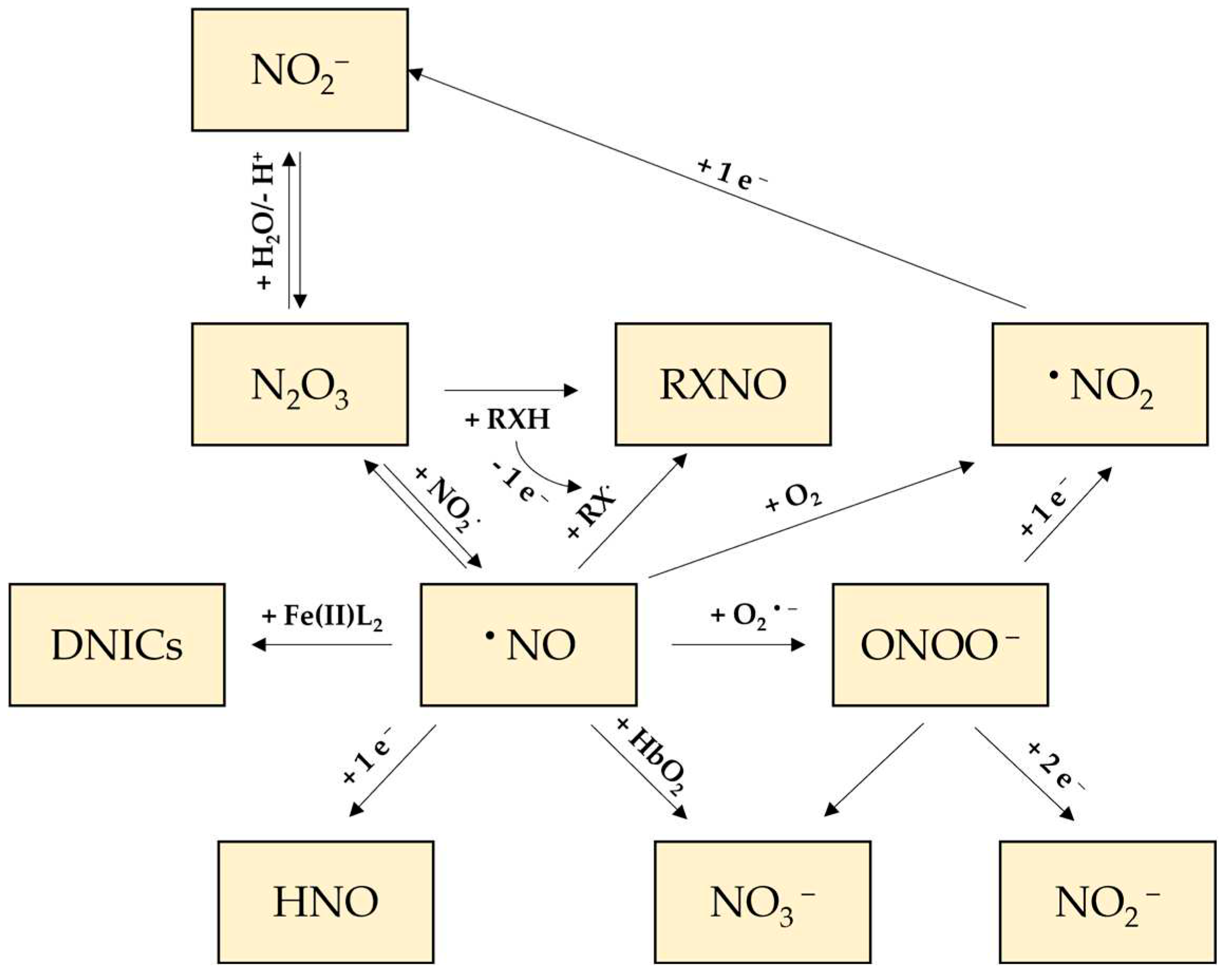

2. NO and its biologically relevant derivatives

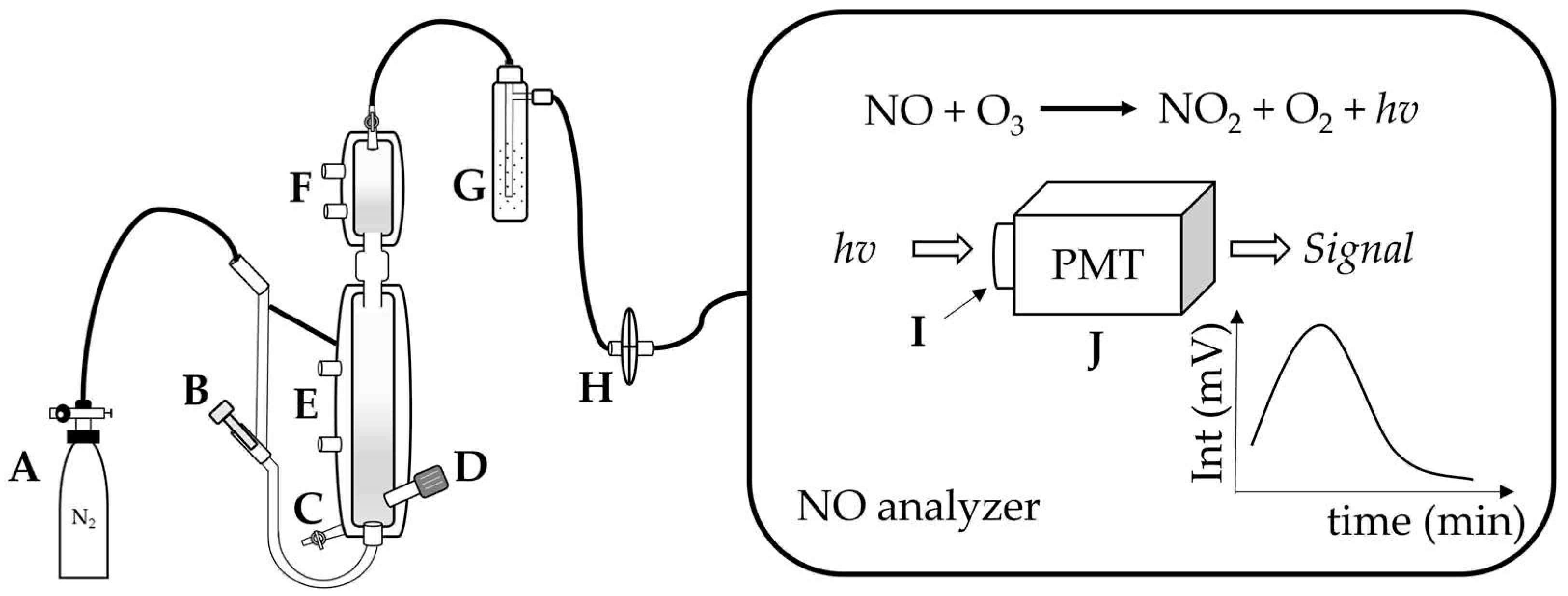

3. Measurement of NO metabolites by chemiluminescence

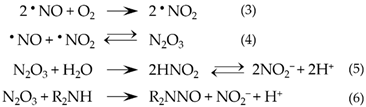

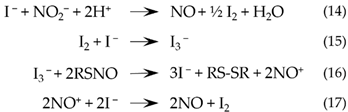

3.1. Reduction of nitrite, RSNO and RNNO by tri-iodide

3.2. Measurement of nitrate by vanadium chloride

4. Multi-level analytical approaches for comprehensive analysis of NO metabolites

4.1. Chemiluminescence coupled with chromatography or mass spectrometry (MS)

4.1.1. Gas chromatography

4.1.2. Liquid chromatography

4.1.3. Mass spectrometry

4.2. Coupled with microdialysis

4.3. Coupled with flow injection analysis

5. Advantages and drawbacks of chemiluminescence for measuring NO species

5.1. Advantages

5.2. Pitfalls

6. Alternatives for the detection of nitric oxide species

6.1. Electrochemical sensors

6.2. Fluorescence

6.3. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)

6.4. Mass spectrometry

6.5. UV-visible spectrophotometry for NO determination

6.6. Griess assay

| Method | Common applications | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical sensors | Direct NO detection via electrooxidation or electroreduction; |

Real-time NO quantification in biological system; NO detection in tissues and cells |

[82,83] |

| Fluorescence | Indirect detection of NO via formation of a fluorescent molecule | Detection of NO in cells and tissues | [85,86,87] |

| Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) | Indirect detection of NO; Direct detection of HbNO and dinitrosyl iron complex |

NO and HbNO detection in cells and tissues | [88,89,90] |

| Mass spectrometry | Detection of NO via multiple ion detection (MID) | NO detection in aqueous solution | [91] |

|

UV-visible spectrophotometry |

Indirect detection of NO via oxyhemoglobin oxidation | NO formation in cells and tissues | [92,94] |

| Griess assay | Determination of nitrite and nitrate via formation of an azo dye in acidic condition | Determination of nitrite level in biological system | [93,95] |

7. Practical considerations

7.1. General concerns about choosing chemiluminescence as a detection tool for NO species

7.2. Technical details on the procedure

7.2.1. Carefully choose calibrants and a range of calibration concentrations

7.2.2. Interference from other components in the matrix, non-objective reaction

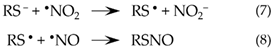

7.3. Notes for ozone-based chemiluminescence detectiion in biological samples

8. Successful application in different fields

9. Summary and conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Fontijn, A.; Sabadell, A.J.; Ronco, R.J. Homogeneous chemiluminescent measurement of nitric oxide with ozone. Implications for continuous selective monitoring of gaseous air pollutants. Analytical chemistry 1970, 42, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feelisch, M.; Rassaf, T.; Mnaimneh, S.; Singh, N.; Bryan, N.S.; Jourd’Heuil, D.; Kelm, M. Concomitant S-, N-, and heme-nitros(yl)ation in biological tissues and fluids: implications for the fate of NO in vivo. FASEB J 2002, 16, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, R.M.; Ferrige, A.G.; Moncada, S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature 1987, 327, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignarro, L.J.; Buga, G.M.; Wood, K.S.; Byrns, R.E.; Chaudhuri, G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987, 84, 9265–9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furchgott, R.F.; Cherry, P.D.; Zawadzki, J.V.; Jothianandan, D. Endothelial cells as mediators of vasodilation of arteries. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1984, 6 Suppl 2, S336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, M.; Feelisch, M.; Spahr, R.; Piper, H.M.; Noack, E.; Schrader, J. Quantitative and kinetic characterization of nitric oxide and EDRF released from cultured endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1988, 154, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.P.; Hoekstra, J.W. Oxidation of nitrogen oxides by bound dioxygen in hemoproteins. J Inorg Biochem 1981, 14, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.S.; Tannenbaum, S.R.; Deen, W.M. Kinetics of N-Nitrosation in Oxygenated Nitric Oxide Solutions at Physiological pH: Role of Nitrous Anhydride and Effects of Phosphate and Chloride. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1995, 117, 3933–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, M.N.; Rios, N.; Trujillo, M.; Radi, R.; Denicola, A.; Alvarez, B. Detection and quantification of nitric oxide-derived oxidants in biological systems. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 14776–14802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Koning, A.; Kuhnle, G.G.C.; Nagy, P.; Bianco, C.L.; Pasch, A.; Wink, D.A.; Fukuto, J.M.; Jackson, A.A.; van Goor, H.; et al. The Reactive Species Interactome: Evolutionary Emergence, Biological Significance, and Opportunities for Redox Metabolomics and Personalized Medicine. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017, 27, 684–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, S.; Czapski, G. Kinetics of Nitric Oxide Autoxidation in Aqueous Solution in the Absence and Presence of Various Reductants. The Nature of the Oxidizing Intermediates. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1995, 117, 12078–12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.; Czapski, G. Mechanism of the Nitrosation of Thiols and Amines by Oxygenated •NO Solutions: the Nature of the Nitrosating Intermediates. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1996, 118, 3419–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, N.S.; Rassaf, T.; Maloney, R.E.; Rodriguez, C.M.; Saijo, F.; Rodriguez, J.R.; Feelisch, M. Cellular targets and mechanisms of nitros(yl)ation: an insight into their nature and kinetics in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 4308–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, M.N.; Li, Q.; Vitturi, D.A.; Robinson, J.M.; Lancaster, J.R., Jr.; Denicola, A. Membrane "lens" effect: focusing the formation of reactive nitrogen oxides from the *NO/O2 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol 2007, 20, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourd’heuil, D.; Jourd’heuil, F.L.; Feelisch, M. Oxidation and nitrosation of thiols at low micromolar exposure to nitric oxide. Evidence for a free radical mechanism. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 15720–15726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, J.C., Jr.; Bosworth, C.A.; Hennon, S.W.; Mahtani, H.A.; Bergonia, H.A.; Lancaster, J.R., Jr. Nitric oxide-induced conversion of cellular chelatable iron into macromolecule-bound paramagnetic dinitrosyliron complexes. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 28926–28933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartberger, M.D.; Liu, W.; Ford, E.; Miranda, K.M.; Switzer, C.; Fukuto, J.M.; Farmer, P.J.; Wink, D.A.; Houk, K.N. The reduction potential of nitric oxide (NO) and its importance to NO biochemistry. 2002, 99, 10958–10963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulik, R.; Debski, D.; Zielonka, J.; Michalowski, B.; Adamus, J.; Marcinek, A.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Sikora, A. Nitroxyl (HNO) reacts with molecular oxygen and forms peroxynitrite at physiological pH. Biological Implications. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 35570–35581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blough, N.V.; Zafiriou, O.C. Reaction of superoxide with nitric oxide to form peroxonitrite in alkaline aqueous solution. Inorganic Chemistry 1985, 24, 3502–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Sueta, G.; Campolo, N.; Trujillo, M.; Bartesaghi, S.; Carballal, S.; Romero, N.; Alvarez, B.; Radi, R. Biochemistry of Peroxynitrite and Protein Tyrosine Nitration. Chem Rev 2018, 118, 1338–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, S.; Shivashankar, K. Metmyoglobin and methemoglobin catalyze the isomerization of peroxynitrite to nitrate. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 14036–14046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, N.; Radi, R.; Linares, E.; Augusto, O.; Detweiler, C.D.; Mason, R.P.; Denicola, A. Reaction of human hemoglobin with peroxynitrite. Isomerization to nitrate and secondary formation of protein radicals. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 44049–44057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.S.; Ferguson, T.B., Jr.; Han, T.H.; Hyduke, D.R.; Liao, J.C.; Rassaf, T.; Bryan, N.; Feelisch, M.; Lancaster, J.R., Jr. Nitric oxide is consumed, rather than conserved, by reaction with oxyhemoglobin under physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 10341–10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosier, B.T.; Buetas, E.; Moya-Gonzalvez, E.M.; Artacho, A.; Mira, A. Nitrate as a potential prebiotic for the oral microbiome. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, T.M.; Stevens, C.R.; Benjamin, N.; Eisenthal, R.; Harrison, R.; Blake, D.R. Xanthine oxidoreductase catalyses the reduction of nitrates and nitrite to nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions. FEBS Lett 1998, 427, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cui, H.; Liu, X.; Zweier, J.L. Xanthine oxidase catalyzes anaerobic transformation of organic nitrates to nitric oxide and nitrosothiols: characterization of this mechanism and the link between organic nitrate and guanylyl cyclase activation. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 16594–16600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapil, V.; Haydar, S.M.; Pearl, V.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Ahluwalia, A. Physiological role for nitrate-reducing oral bacteria in blood pressure control. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 55, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Nitric oxide signaling in health and disease. Cell 2022, 185, 2853–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, E.A.; Huang, L.; Malkey, R.; Govoni, M.; Nihlen, C.; Olsson, A.; Stensdotter, M.; Petersson, J.; Holm, L.; Weitzberg, E.; et al. A mammalian functional nitrate reductase that regulates nitrite and nitric oxide homeostasis. Nat Chem Biol 2008, 4, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.C.S.t.; Lechauve, C.; Keller, A.S.; Brooks, S.; Weiss, M.J.; Columbus, L.; Ackerman, H.; Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Isakson, B.E. The role of globins in cardiovascular physiology. Physiol Rev 2022, 102, 859–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosby, K.; Partovi, K.S.; Crawford, J.H.; Patel, R.P.; Reiter, C.D.; Martyr, S.; Yang, B.K.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Zalos, G.; Xu, X.; et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med 2003, 9, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoBue, A.; Heuser, S.K.; Lindemann, M.; Li, J.; Rahman, M.; Kelm, M.; Stegbauer, J.; Cortese-Krott, M.M. Red blood cell endothelial nitric oxide synthase: A major player in regulating cardiovascular health. Br J Pharmacol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Bonaventura, C.; Bonaventura, J.; Stamler, J.S. S-nitrosohaemoglobin: a dynamic activity of blood involved in vascular control. Nature 1996, 380, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Schechter, A.N.; Shelhamer, J.H.; Pannell, L.K.; Conway, D.A.; Hrinczenko, B.W.; Nichols, J.S.; Pease-Fye, M.E.; Noguchi, C.T.; Rodgers, G.P.; et al. Inhaled nitric oxide augments nitric oxide transport on sickle cell hemoglobin without affecting oxygen affinity. J Clin Invest 1999, 104, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bryan, N.S.; MacArthur, P.H.; Rodriguez, J.; Gladwin, M.T.; Feelisch, M. Measurement of nitric oxide levels in the red cell: validation of tri-iodide-based chemiluminescence with acid-sulfanilamide pretreatment. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 26994–27002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarason, A.K.; Allman, K.G.; Young, D.; Redman, C.W. Elevated levels of serum nitrate, a stable end product of nitric oxide, in women with pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997, 104, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Alghayth, M.; Vanhatalo, A.; Wylie, L.J.; McDonagh, S.T.; Thompson, C.; Kadach, S.; Kerr, P.; Smallwood, M.J.; Jones, A.M.; Winyard, P.G. S-nitrosothiols, and other products of nitrate metabolism, are increased in multiple human blood compartments following ingestion of beetroot juice. Redox Biol 2021, 43, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samouilov, A.; Zweier, J.L. Development of chemiluminescence-based methods for specific quantitation of nitrosylated thiols. Anal Biochem 1998, 258, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley, R.; Feelisch, M.; Holt, S.; Moore, K. A chemiluminescense-based assay for S-nitrosoalbumin and other plasma S-nitrosothiols. Free Radic Res 2000, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.F.; Janero, D.R. Specific S-nitrosothiol (thionitrite) quantification as solution nitrite after vanadium(III) reduction and ozone-chemiluminescent detection. Free Radic Biol Med 1998, 25, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, K.; Ragsdale, N.V.; Carey, R.M.; MacDonald, T.; Gaston, B. Reductive assays for S-nitrosothiols: implications for measurements in biological systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 252, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Wang, X.; Reiter, C.D.; Yang, B.K.; Vivas, E.X.; Bonaventura, C.; Schechter, A.N. S-Nitrosohemoglobin is unstable in the reductive erythrocyte environment and lacks O2/NO-linked allosteric function. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 27818–27828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Shi, P.; Song, W.; Bi, S. Chemiluminescence and Bioluminescence Imaging for Biosensing and Therapy: In Vitro and In Vivo Perspectives. Theranostics 2019, 9, 4047–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, W.; Wu, R.; Guan, W.; Ye, N. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Chemiluminescence Probes for Biosensing and Imaging of Reactive Oxygen Species. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinari, E.M.; Manes, J.D. Nitrogen-specific detection of peptides in liquid chromatography with a chemiluminescent nitrogen detector. Journal of Chromatography A 1994, 676, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannegan, D.; Ashraf-Khorassani, M.; Taylor, L.T. High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with chemiluminescence nitrogen detection for the study of ethoxyquin antioxidant and related organic bases. J Chromatogr Sci 2001, 39, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashihira, N.; Makino, K.; Kirita, K.; Watanabe, Y. Chemiluminescent nitrogen detector-gas chromatography and its application to measurement of atmospheric ammonia and amines. Journal of Chromatography A 1982, 239, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinari, E.M. Gas chromatography-chemiluminescent nitrogen detection: GC-CLND. In Developments in Food Science, Wetzel, D.L.B., Charalambous, G., Eds.; Elsevier: 1998; Volume 39, pp. 385–424.

- Toraman, H.E.; Franz, K.; Ronsse, F.; Van Geem, K.M.; Marin, G.B. Quantitative analysis of nitrogen containing compounds in microalgae based bio-oils using comprehensive two-dimensional gas-chromatography coupled to nitrogen chemiluminescence detector and time of flight mass spectrometer. J Chromatogr A 2016, 1460, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, D.; Ozel, M.Z.; Gogus, F.; Hamilton, J.F.; Lewis, A.C. Determination of volatile nitrosamines in grilled lamb and vegetables using comprehensive gas chromatography - nitrogen chemiluminescence detection. Food Chem 2012, 135, 2215–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozel, M.Z.; Hamilton, J.F.; Lewis, A.C. New sensitive and quantitative analysis method for organic nitrogen compounds in urban aerosol samples. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinari, E.M.; Damon Manes, J. Nitrogen-specific liquid chromatography detection of nucleotides and nucleosides by HPLC-CLND. In Developments in Food Science, Charalambous, G., Ed.; Elsevier: 1995; Volume 37, pp. 379–396.

- Robbat, A.; Corso, N.P.; Liu, T.Y. Evaluation of a nitrosyl-specific gas-phase chemiluminescence detector with high-performance liquid chromatography. Analytical Chemistry 1988, 60, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinari, E.M.; Courthaudon, L.O. Nitrogen-specific liquid chromatography detector based on chemiluminescence: Application to the analysis of ammonium nitrogen in waste water. Journal of Chromatography A 1992, 592, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinari, E.M.; Manes, J.D.; Bizanek, R. Peptide content determination of crude synthetic peptides by reversed-phase liquid chromatography and nitrogen-specific detection with a chemiluminescent nitrogen detector. Journal of Chromatography A 1996, 743, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.C.; Wagner, D.A.; Glogowski, J.; Skipper, P.L.; Wishnok, J.S.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem 1982, 126, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Akaike, T.; Fang, J.; Beppu, T.; Ogawa, M.; Tamura, F.; Miyamoto, Y.; Maeda, H. Antiapoptotic effect of haem oxygenase-1 induced by nitric oxide in experimental solid tumour. Br J Cancer 2003, 88, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, N.S.; Grisham, M.B. Methods to detect nitric oxide and its metabolites in biological samples. Free Radic Biol Med 2007, 43, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Simultaneous derivatization and quantification of the nitric oxide metabolites nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 2000, 72, 4064–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Fung, H.L. Evaluation of an LC-MS/MS assay for 15N-nitrite for cellular studies of L-arginine action. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2011, 56, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corens, D.; Carpentier, M.; Schroven, M.; Meerpoel, L. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry with chemiluminescent nitrogen detection for on-line quantitative analysis of compound collections: advantages and limitations. Journal of Chromatography A 2004, 1056, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.W.; Jia, W.; Bush, M.; Dollinger, G.D. Accelerating the drug optimization process: identification, structure elucidation, and quantification of in vivo metabolites using stable isotopes with LC/MSn and the chemiluminescent nitrogen detector. Anal Chem 2002, 74, 3232–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelius, J.; Tran, T.; Turner, N.; Piazza, A.; Mills, L.; Slack, R.; Hauser, S.; Alexander, J.S.; Grisham, M.B.; Feelisch, M.; et al. Isotope tracing enhancement of chemiluminescence assays for nitric oxide research. Biol Chem 2009, 390, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, J.M.; DeFeudis, F.V.; Roth, R.H.; Ryugo, D.K.; Mitruka, B.M. Dialytrode for long term intracerebral perfusion in awake monkeys. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 1972, 198, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Vlessidis, A.G.; Evmiridis, N.P.; Evangelou, A.; Karkabounas, S.; Tsampalas, S. Luminol chemiluminescense reaction: a new method for monitoring nitric oxide in vivo. Analytica Chimica Acta 2002, 458, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanowicz, M.; Pyszynska, M. Flow-Injection Methods in Water Analysis-Recent Developments. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Fukuda, S.; Hosoi, Y.; Mukai, H. Rapid flow injection analysis method for successive determination of ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate in water by gas-phase chemiluminescence. Analytica Chimica Acta 1997, 349, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendgen-Cotta, U.; Grau, M.; Rassaf, T.; Gharini, P.; Kelm, M.; Kleinbongard, P. Reductive gas-phase chemiluminescence and flow injection analysis for measurement of the nitric oxide pool in biological matrices. Methods Enzymol 2008, 441, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Vlessidis, A.G.; Evmiridis, N.P. Dialysis membrane sampler for on-line flow injection analysis/chemiluminescence-detection of peroxynitrite in biological samples. Talanta 2003, 59, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Dejam, A.; Lauer, T.; Jax, T.; Kerber, S.; Gharini, P.; Balzer, J.; Zotz, R.B.; Scharf, R.E.; Willers, R.; et al. Plasma nitrite concentrations reflect the degree of endothelial dysfunction in humans. Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 40, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, A.; Zajda, J.; Meyerhoff, M.E. Comparison of electrochemical nitric oxide detection methods with chemiluminescence for measuring nitrite concentration in food samples. Anal Chim Acta 2019, 1077, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.N.; Green, J.R.; Mutus, B. Fluorescein isothiocyanate, a platform for the selective and sensitive detection of S-Nitrosothiols and hydrogen sulfide. Talanta 2022, 237, 122981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Vlessidis, A.G.; Evmiridis, N.P. Determination of nitric oxide in biological samples. Microchimica Acta 2004, 147, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garside, C. A chemiluminescent technique for the determination of nanomolar concentrations of nitrate and nitrite in seawater. Marine Chemistry 1982, 11, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallakunta, V.M.; Slama-Schwok, A.; Mutus, B. Protein disulfide isomerase may facilitate the efflux of nitrite derived S-nitrosothiols from red blood cells. Redox Biol 2013, 1, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doctor, A.; Platt, R.; Sheram, M.L.; Eischeid, A.; McMahon, T.; Maxey, T.; Doherty, J.; Axelrod, M.; Kline, J.; Gurka, M.; et al. Hemoglobin conformation couples erythrocyte S-nitrosothiol content to O2 gradients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 5709–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamler, J.S.; Jaraki, O.; Osborne, J.; Simon, D.I.; Keaney, J.; Vita, J.; Singel, D.; Valeri, C.R.; Loscalzo, J. Nitric oxide circulates in mammalian plasma primarily as an S-nitroso adduct of serum albumin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 7674–7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Shelhamer, J.H.; Schechter, A.N.; Pease-Fye, M.E.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Panza, J.A.; Ognibene, F.P.; Cannon, R.O. , 3rd. Role of circulating nitrite and S-nitrosohemoglobin in the regulation of regional blood flow in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 11482–11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.K.; Vivas, E.X.; Reiter, C.D.; Gladwin, M.T. Methodologies for the sensitive and specific measurement of S-nitrosothiols, iron-nitrosyls, and nitrite in biological samples. Free Radic Res 2003, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piknova, B.; Park, J.W.; Cassel, K.S.; Gilliard, C.N.; Schechter, A.N. Measuring Nitrite and Nitrate, Metabolites in the Nitric Oxide Pathway, in Biological Materials using the Chemiluminescence Method. J Vis Exp 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, R.M.; Ellis, C.G.; Freeman, D.J. Optimization of nitric oxide chemiluminescence operating conditions for measurement of plasma nitrite and nitrate. Clin Chem 2002, 48, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.D.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Electrochemical Nitric Oxide Sensors: Principles of Design and Characterization. Chem Rev 2019, 119, 11551–11575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuki, K. An electrochemical microprobe for detecting nitric oxide release in brain tissue. Neurosci Res 1990, 9, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yuan, B.; Yin, T.; Qin, W. Alternative coulometric signal readout based on a solid-contact ion-selective electrode for detection of nitrate. Anal Chim Acta 2020, 1129, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiersma, J.H. 2, 3-Diaminonaphthalene as a spectrophotometric and fluorometric reagent for the determination of nitrite ion. Analytical Letters 1970, 3, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H.; Sakurai, K.; Kikuchi, K.; Kawahara, S.; Kirino, Y.; Nagoshi, H.; Hirata, Y.; Nagano, T. Development of a fluorescent indicator for nitric oxide based on the fluorescein chromophore. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1998, 46, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; LoBue, A.; Heuser, S.K.; Leo, F.; Cortese-Krott, M.M. Using diaminofluoresceins (DAFs) in nitric oxide research. Nitric Oxide 2021, 115, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleschyov, A.L.; Mollnau, H.; Oelze, M.; Meinertz, T.; Huang, Y.; Harrison, D.G.; Munzel, T. Spin trapping of vascular nitric oxide using colloid Fe(II)-diethyldithiocarbamate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 275, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Hyde, J.S. Trapping of nitric oxide by nitronyl nitroxides: an electron spin resonance investigation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993, 192, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piknova, B.; Gladwin, M.T.; Schechter, A.N.; Hogg, N. Electron paramagnetic resonance analysis of nitrosylhemoglobin in humans during NO inhalation. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 40583–40588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, J.M.; Chrestensen, C.A.; Moomaw, E.W. Detection of Nitric Oxide by Membrane Inlet Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1747, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feelisch, M.; Noack, E.A. Correlation between nitric oxide formation during degradation of organic nitrates and activation of guanylate cyclase. European journal of pharmacology 1987, 139, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griess, P. Bemerkungen zu der Abhandlung der HH. Weselsky und Benedikt „Ueber einige Azoverbindungen”︁. 1879, 12, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, M.; Schrader, J. Control of coronary vascular tone by nitric oxide. Circ Res 1990, 66, 1561–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, I.; Iwanejko, J.; Dembinska-Kiec, A.; Pankiewicz, J.; Wanat, A.; Anna, P.; Golabek, I.; Bartus, S.; Malczewska-Malec, M.; Szczudlik, A. Determination of nitrite/nitrate in human biological material by the simple Griess reaction. Clin Chim Acta 1998, 274, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagababu, E.; Rifkind, J.M. Measurement of plasma nitrite by chemiluminescence. Methods Mol Biol 2010, 610, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.; Suvorava, T.; Heuser, S.K.; Li, J.; LoBue, A.; Barbarino, F.; Piragine, E.; Schneckmann, R.; Hutzler, B.; Good, M.E.; et al. Red Blood Cell and Endothelial eNOS Independently Regulate Circulating Nitric Oxide Metabolites and Blood Pressure. Circulation 2021, 144, 870–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Rassaf, T.; Dejam, A.; Kerber, S.; Kelm, M. Griess method for nitrite measurement of aqueous and protein-containing samples. Methods Enzymol 2002, 359, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D.; Rossi, R.; Milzani, A.; Dalle-Donne, I. Nitrite and nitrate measurement by Griess reagent in human plasma: evaluation of interferences and standardization. Methods Enzymol 2008, 440, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsikas, D. Analysis of nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids by assays based on the Griess reaction: appraisal of the Griess reaction in the L-arginine/nitric oxide area of research. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2007, 851, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.A.; Storm, W.L.; Coneski, P.N.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Inaccuracies of nitric oxide measurement methods in biological media. Anal Chem 2013, 85, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brizzolari, A.; Dei Cas, M.; Cialoni, D.; Marroni, A.; Morano, C.; Samaja, M.; Paroni, R.; Rubino, F.M. High-Throughput Griess Assay of Nitrite and Nitrate in Plasma and Red Blood Cells for Human Physiology Studies under Extreme Conditions. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, P.H.; Shiva, S.; Gladwin, M.T. Measurement of circulating nitrite and S-nitrosothiols by reductive chemiluminescence. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2007, 851, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R.A.; Floreani, A.A.; Von Essen, S.G.; Sisson, J.H.; Hill, G.E.; Rubinstein, I.; Townley, R.G. Measurement of exhaled nitric oxide by three different techniques. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 153, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binding, N.; Muller, W.; Czeschinski, P.A.; Witting, U. NO chemiluminescence in exhaled air: interference of compounds from endogenous or exogenous sources. Eur Respir J 2000, 16, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, J.N. Nitric oxide measurement by chemiluminescence detection. Neuroprotocols 1992, 1, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.W.; Spicer, C.W. Chemiluminescence method for atmospheric monitoring of nitric acid and nitrogen oxides. Analytical Chemistry 1978, 50, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuik, F.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Lauer, A.; Lupascu, A.; von Schneidemesser, E.; Butler, T.M. Top–down quantification of NOx emissions from traffic in an urban area using a high-resolution regional atmospheric chemistry model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 8203–8225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Astorga, C. Impact of cold temperature on Euro 6 passenger car emissions. Environmental Pollution 2018, 234, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, K.-K.; Yang, G.-P.; Li, P.-F.; Liu, C.-Y.; Ingeniero, R.C.O.; Bange, H.W. Continuous Chemiluminescence Measurements of Dissolved Nitric Oxide (NO) and Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) in the Ocean Surface Layer of the East China Sea. Environmental Science & Technology 2021, 55, 3668–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y.; Taira, M. Flow-Injection Analysis Method for the Determination of Nitrite and Nitrate in Natural Water Samples Using a Chemiluminescence NO<SUB>x</SUB> Monitor. Analytical Sciences 2003, 19, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijay, S.; Craswell, E. Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and ground water: an increasingly pervasive global problem. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, L.E.; Leone, A.M.; Persson, M.G.; Wiklund, N.P.; Moncada, S. Endogenous nitric oxide is present in the exhaled air of rabbits, guinea pigs and humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1991, 181, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alving, K.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.M. Increased amount of nitric oxide in exhaled air of asthmatics. Eur Respir J 1993, 6, 1368–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmstrom, R.E.; Tornberg, D.C.; Settergren, G.; Liska, J.; Angdin, M.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Endogenous nitric oxide release by vasoactive drugs monitored in exhaled air. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 168, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.; Hargadon, B.; Morgan, A.; Shelley, M.; Richter, J.; Shaw, D.; Green, R.H.; Brightling, C.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Pavord, I.D. Alveolar nitric oxide in adults with asthma: evidence of distal lung inflammation in refractory asthma. Eur Respir J 2005, 25, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Khatri, S.B.; Tejwani, V. Measuring exhaled nitric oxide when diagnosing and managing asthma. Cleve Clin J Med 2023, 90, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, A.; Mitchell, K.; Blackwell, J.R.; Vanhatalo, A.; Jones, A.M. High-nitrate vegetable diet increases plasma nitrate and nitrite concentrations and reduces blood pressure in healthy women. Public Health Nutr 2015, 18, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.D.; Marsh, A.P.; Dove, R.W.; Beavers, D.; Presley, T.; Helms, C.; Bechtold, E.; King, S.B.; Kim-Shapiro, D. Plasma nitrate and nitrite are increased by a high-nitrate supplement but not by high-nitrate foods in older adults. Nutr Res 2012, 32, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, V.; Milsom, A.B.; Okorie, M.; Maleki-Toyserkani, S.; Akram, F.; Rehman, F.; Arghandawi, S.; Pearl, V.; Benjamin, N.; Loukogeorgakis, S.; et al. Inorganic nitrate supplementation lowers blood pressure in humans: role for nitrite-derived NO. Hypertension 2010, 56, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, F.J.; Ekblom, B.; Sahlin, K.; Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E. Effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure in healthy volunteers. N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 2792–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Dejam, A.; Lauer, T.; Rassaf, T.; Schindler, A.; Picker, O.; Scheeren, T.; Godecke, A.; Schrader, J.; Schulz, R.; et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med 2003, 35, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milsom, A.B.; Fernandez, B.O.; Garcia-Saura, M.F.; Rodriguez, J.; Feelisch, M. Contributions of nitric oxide synthases, dietary nitrite/nitrate, and other sources to the formation of NO signaling products. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012, 17, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, T.; Preik, M.; Rassaf, T.; Strauer, B.E.; Deussen, A.; Feelisch, M.; Kelm, M. Plasma nitrite rather than nitrate reflects regional endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity but lacks intrinsic vasodilator action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 12814–12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.C.; Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Kovacic, J.C.; Noguchi, A.; Liu, V.B.; Wang, X.; Raghavachari, N.; Boehm, M.; Kato, G.J.; Kelm, M.; et al. Circulating blood endothelial nitric oxide synthase contributes to the regulation of systemic blood pressure and nitrite homeostasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013, 33, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Piknova, B.; Huang, P.L.; Noguchi, C.T.; Schechter, A.N. Effect of blood nitrite and nitrate levels on murine platelet function. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominic, P.; Ahmad, J.; Bhandari, R.; Pardue, S.; Solorzano, J.; Jaisingh, K.; Watts, M.; Bailey, S.R.; Orr, A.W.; Kevil, C.G.; et al. Decreased availability of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide is a hallmark of COVID-19. Redox Biol 2021, 43, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, A.; Bhatoee, M.; Singh, P.; Kaladhar, V.C.; Yadav, N.; Paul, D.; Loake, G.J.; Gupta, K.J. Detection of Nitric Oxide from Chickpea Using DAF Fluorescence and Chemiluminescence Methods. Current Protocols 2022, 2, e420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picetti, R.; Deeney, M.; Pastorino, S.; Miller, M.R.; Shah, A.; Leon, D.A.; Dangour, A.D.; Green, R. Nitrate and nitrite contamination in drinking water and cancer risk: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Environ Res 2022, 210, 112988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, S.R.; Correa, P. Nitrate and gastric cancer risks. Nature 1985, 317, 675–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, T.; Di Taranto, A.; Berardi, G.; Vita, V.; Iammarino, M. Nitrate as food additives: Reactivity, occurrence, and regulation. In Nitrate handbook; CRC Press: 2022; pp. 281–300.

- Ziarati, P.; Zahedi, M.; Shirkhan, F.; Mostafidi, M. Potential health risks and concerns of high levels of nitrite and nitrate in food sources. SF Pharma J 2018, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kapil, V.; Khambata, R.S.; Robertson, A.; Caulfield, M.J.; Ahluwalia, A. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension 2015, 65, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, A.; Wany, A.; Pandey, S.; Bulle, M.; Kumari, A.; Kishorekumar, R.; Igamberdiev, A.U.; Mur, L.A.J.; Gupta, K.J. Current approaches to measure nitric oxide in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2019, 70, 4333–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.J.; Kaiser, W.M. Production and Scavenging of Nitric Oxide by Barley Root Mitochondria. Plant and Cell Physiology 2010, 51, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, N.; Tiwari, S.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Nitric oxide in plants: an ancient molecule with new tasks. Plant Growth Regulation 2020, 90, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction solution | Conditions | Target NO metabolites |

References |

| Iodine/iodide | 60 mM I−/6 to 20 mM I2/ 1M HCl, RT | NO2−; RNNO, RSNO | [38] |

| 56 mM I−/2 mM I2, 4mM CuCl, CH3COOH, 68°C | [39] | ||

| 45 mM I−/10 mM I2, CH3COOH, 60°C | [2] | ||

| VCl3/H+ | 0.1 M vanadium(III) in 2M HCl | NO3−; NO2−; RNNO; RSNO | [40] |

| Cysteine/CuCl | 1 mM L-cysteine/ 0.1 mM CuCl | RSNO | [41] |

| Hydroquinone/quinone | 0.1 M hydroqui-none/ 0.01 M quinone | RSNO | [38] |

| Ferricyanide |

0.2 M ferricyanide in PBS, pH 7.5 | NO-Heme | [42] |

| 0.05 M ferricyanide in PBS, pH 7.5 | [13] |

| 1. Pretreatment |

Stabilization reagent is prepared for organ tissues and RBCs by adding…

|

Differentiation assistant reagent: measurements in tri-iodide reductive solution in…

|

| 2. Avoiding contamination |

Nitrite contamination is everywhere; therefore, paying attention to…

|

| 3. Minimum time before storage |

The scavenging of the nitrite can be really fast; therefore...

|

| 4. Sample storage |

|

| 5. Measurement procedure |

|

| 6. Technical issues |

|

| 7. pH value affecting the reductive reaction |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).