1. Introduction

Telemedicine offers numerous benefits, including reducing regional disparities in healthcare access and improving services for patients who face difficulties visiting hospitals or clinics. It also contributes to better working conditions for physicians and enables medical facilities to accommodate a larger number of patients [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the effective implementation of telemedicine requires not only appropriate systems and medical devices but also seamless integration of various diagnostic data during online consultations. Because physical examinations—such as palpation, urine tests, blood tests, and X-ray imaging—are not feasible remotely, the scope of telemedicine remains somewhat limited. Nonetheless, certain physiological measurements, such as electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring, can be conducted remotely. Several factors are expected to drive the future of healthcare. First, advancements in remote monitoring technologies will allow real-time tracking of patients’ health conditions. Beyond measuring vital signs with smartwatches and sensors, cloud-based health manage-ment platforms will enable healthcare providers to remotely analyze patient data and take timely actions. Second, the use of AI for disease prediction and anomaly detec-tion will support early intervention. Machine learning models will facilitate compari-son of real-time and historical patient data, enabling the detection of subtle changes. Furthermore, AI-driven optimization of individualized treatment plans will enhance disease management. The broader adoption of virtual consultations and online care will also ease the burden on medical institutions and patients alike. Remote prescrip-tions and online pharmacies will further streamline the process, enabling medication delivery after virtual consultations. Additionally, improving patients’ self-management capabilities is crucial. Mobile apps for symptom tracking, medica-tion management, and lifestyle guidance, combined with real-time biofeedback train-ing, will empower patients to actively monitor and manage their own health. One promising modality for remote diagnostics is the measurement of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO). FeNO testing is a quantitative, non-invasive, simple, and safe method for as-sessing airway inflammation, and it serves as a valuable complement to other diag-nostic tools for airway diseases [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Owing to its simplicity and safety, FeNO mon-itoring holds strong potential for remote healthcare applications. With further ad-vances in telemedicine, real-time FeNO monitoring could support patient self-management and enhance disease control while minimizing the need for frequent hospital visits.

Despite its potential, FeNO testing is not commonly included in routine health checkups, leading to a limited understanding of its variability in healthy individuals. Most previous studies have focused on patients with respiratory diseases such as asthma [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], while data from healthy populations remain sparse. Clarifying the variability and time-dependent fluctuations of FeNO in healthy individuals is critical for establishing reference values and evaluating its feasibility for broader telemedicine use [

29,

30].To address this gap, the present study aims to analyze individual variabil-ity and time-dependent differences in FeNO levels among healthy subjects. By catego-rizing measurements into four distinct time frames and conducting statistical analyses, we seek to shed light on the natural fluctuations of FeNO in healthy individuals. These findings may inform the development of remote FeNO monitoring systems, thereby supporting early detection and management of airway inflammation in tele-medicine settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

8 healthy participants (mean age: 61.3 ± 14 years, 2 females) were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria required all participants to be free from respiratory diseases. The exclusion criteria included individuals diagnosed with respiratory disorders (

Table 1). All participants provided informed consent before participation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Engineering, Mie University (Approval number 132, Approved February 19, 2025).

The measurement times were grouped as shown in the table below (

Table 2).

Participants in the experiment took the breath gas test to measure NO at a time convenient for them, so the amount of data varies depending on the time period.

2.2. FeNO Measurement Device

Exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was measured using the NIOX VERO device (Chest M.I., Inc., Japan; Medical Device Approval Number: 22700BZX00030000, JAN Code: 7350047030229). The device was operated via a PC application, “NIOX Panel,” with USB cable communication.

FeNO measurements followed the guidelines established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), which recommend exhaling at a constant flow rate of 50 ml/sec ± 10% for 10 seconds. The measurement process involved the following steps; participants inhaled NO-free gas through a built-in NO scrubber in the device’s respiratory handle. They then exhaled at a constant flow rate (50 ml/sec ± 10%) for 10 seconds following ATS/ERS standards. The last 3 seconds of exhalation were sampled for FeNO analysis to ensure a stable reading. If the exhalation flow rate or duration was insufficient, the measurement was in-erupted and repeated. The total measurement time, from initiation to result display, was approximately 1 minute and 30 seconds. Regarding the output of NO concentration values, the measuring device samples the last 3 seconds of exhalation and analyzes the NO concentration. FeNO values are typically 15 ppb or less in healthy individuals, but values of 22 ppb or higher indicate a possibility of asthma, and values of 37 ppb or higher indicate a high likelihood of asthma [

7,

8,

12].

Next, discuss Device Calibration and Environmental Conditions. The NIOX VERO device measures FeNO in parts per billion (ppb) with high precision. To maintain measurement accuracy, the device, sensor, and respiratory handle have predefined expiration and usage limits. During this study, these components were replaced as necessary, eliminating the need for additional calibration. All measurements were conducted in a temperature-controlled environment (24°C ± 2°C). Participants remained seated at rest during the FeNO measurement process.

2.3. Exchange Kinetics of Exhaled Nitric Oxide (NO)

For an explanation of the exchange kinetics of NO in exhaled air, Nikolaos M. et al. In this study [

31], a model of the lung divided into two compartments, airways and alveoli, was constructed to reproduce the relationship between exhaled NO concentration and expiratory flow rate and to provide an index for assessing the contribution of NO sources in the lung. In this study, a two-compartment mathematical model was developed to analyze the exchange dynamics of NO in exhaled breath, dividing the lungs into two regions: the airways and the alveoli. Each compartment is surrounded by a tissue layer capable of producing and consuming NO, with adjacent blood flow (bronchial circulation for the airways and pulmonary circulation for the alveoli) assumed to be an infinite sink for NO. The NO production rate was estimated based on existing experimental data, and parameters were adjusted to match experimental results by simulating the relationship between the NO elimination rate at end-exhalation (ENO) and the exhalation flow rate (V˙E). Additionally, the relationship between ENO and V˙E was used as an index to evaluate the relative contributions of the airways and alveoli to exhaled NO. This model demonstrated that exhaled NO concentration is inversely correlated with exhalation flow rate and that both the airways and alveoli contribute to NO elimination. Unlike previous single-compartment models, which struggled to explain certain experimental findings, this two-compartment model successfully reproduces observed phenomena, providing a more comprehensive framework for understanding NO exchange dynamics [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. The concentration of exhaled NO is known to depend on the V˙E, a phenomenon that must be accurately accounted for in mathematical models of NO exchange. As exhalation flow rate increases, the concentration of NO in exhaled breath generally decreases due to the shortened residence time of NO within the airways and the dilution effect of increased airflow. Conversely, at lower flow rates, NO accumulates in the airway compartment, leading to higher concentrations in the exhaled breath.To quantify this relationship, the two-compartment model incorporates flow-dependent NO transport dynamics. The parameters governing NO production and uptake in the airway and alveolar compartments were estimated using experimental data, particularly the observed relationship between the NO elimination rate at ENO and V˙E. By fitting the model to experimental results, key physiological parameters such as NO production rates in the airways and alveoli, tissue diffusion coefficients, and airway wall uptake rates were optimized.Through this approach, the model reproduces the characteristic inverse correlation between exhaled NO concentration and exhalation flow rate [

39].

The NO concentration in exhaled breath is described by the following formula,

Cno(t) is the concentration of NO in exhaled air, Calv is the alveolar NO concentration, Jaw is the airway NO flux, and Daw is the airway diffusion parameter.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We compared FeNO levels at different measurement points using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). We used SPSS Statistics (IBM SPSS Statistics v29.0.1) for the analysis. We evaluated the temporal variation in FeNO levels, taking into account the within-subject variability. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Mathematically, the repeated measures ANOVA model can be expressed as:

where:

Yij is the FeNO value of subject i at time point j,

μis the overall mean,

αj is the fixed effect of the time point j

si is the random effect associated with subject i (accounting for within-subject variability),

εij is the residual error term.

The main hypothesis tested is:

against the alternative:

This model allows us to assess whether FeNO levels significantly vary across the measurement times within the same individuals (2-4).

3. Results

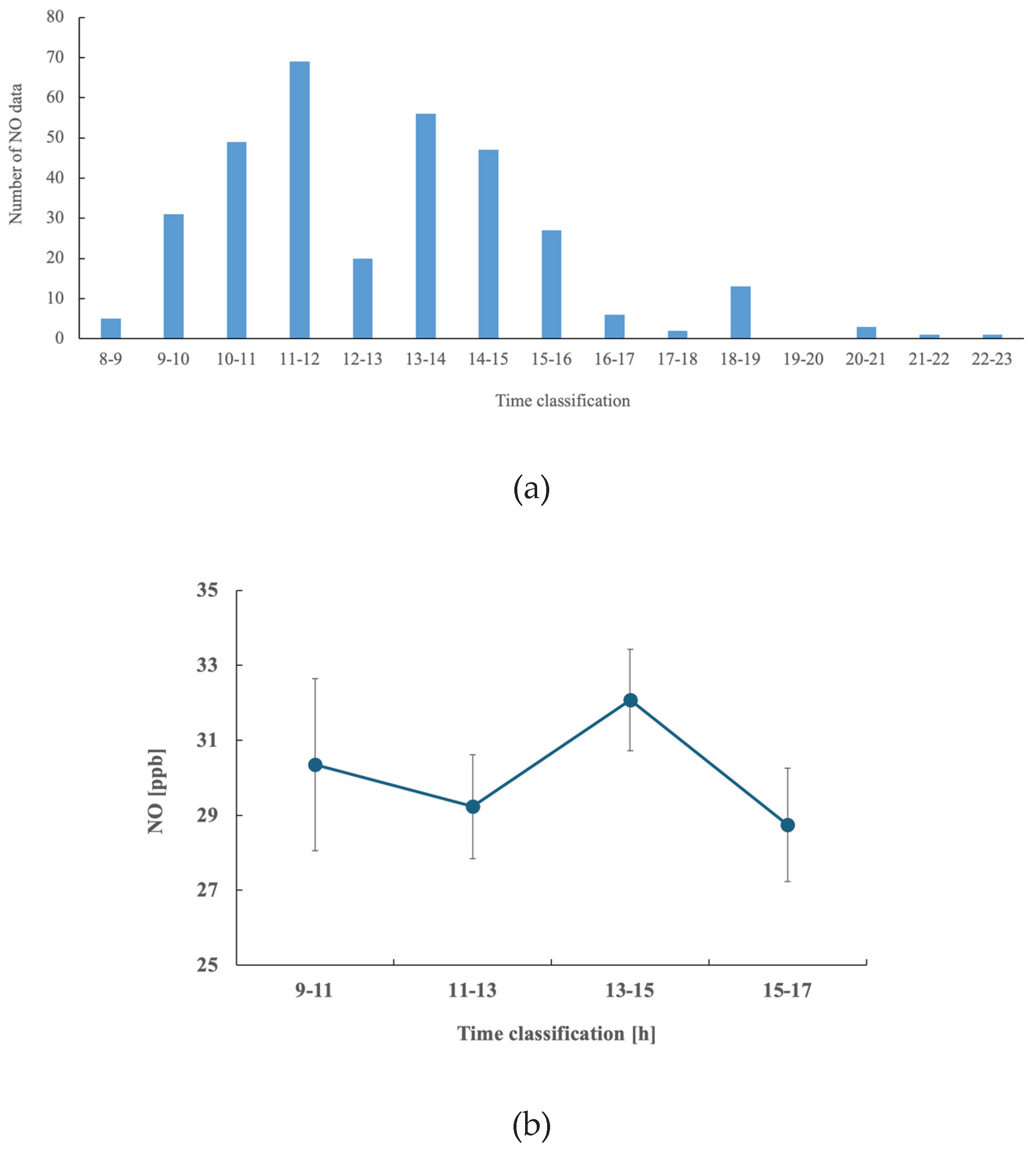

The results of statistical analysis using analysis of variance are shown in the table (

Table 3). NO levels fluctuated greatly from person to person, so no significant differences were observed (

Figure 1). NO levels showed particularly large fluctuations in the morning. Statistical analysis was performed on the 4 groups of 11am-1pm, 1-3pm, and 3-5pm, there were slight differences in the measured values depending on the measurement time (P = 0.088).

S.D. is Standard Deviation and S.E. means Standard Error. S.D. measures the variability or dispersion of individual data points from the mean. S.E. represents the variability of the sample mean estimate of a population mean.

4. Discussion

In this study, we analyzed exhaled NO values using analysis of variance: 80 cases from 9-11am, 89 cases from 11-1pm, 103 cases from 1-3pm, and 33 cases from 3-5pm. The results showed that there were no significant differences because NO fluctuates greatly from person to person, and that there are large fluctuations in the morning. First, we will consider the effects of circadian rhythms. In a previous study, the possible effects of the important internal variable circadian rhythm on exhaled breath temperature (EBT) were analyzed in a group of 24 healthy adult volunteers [

40,

41]. EBT was measured repeatedly at different times of day (8am, noon, 4pm, and 8pm), and the correlation with axillary temperature readings at these times was analyzed. The results reported that there were significant differences in some axillary temperature readings. The highest EBT was reported at 4pm, and the lowest EBT was reported at 8am, indicating that circadian rhythms affect EBT. This is the first analysis of circadian rhythms in healthy subjects exhaled NO levels, and it was shown that they are not affected by circadian rhythms compared to EBT.

Next, we will consider repeated measurements. Recent studies have shown excellent reproducibility in FeNO measurements, and in a study that determined whether repeated FeNO measurements were necessary in the same session for asthma screening, the value of repeated measurements was shown to be insignificant [

42]. The results of this study are also consistent with the results of previous studies, as although there is a large individual difference in the measured NO values of healthy individuals, the variation within individuals is not that large.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the results. A limited number of participants can reduce the statistical power required to detect significant differences, potentially impacting the interpretation of the findings. Additionally, there was a wide age range among the participants, which is another limitation. Variations in age can influence the production and fluctuations of FeNO, and age-related physiological differences in the respiratory system may introduce bias in the results. The impact of these age-related variations should be considered, and a more age-homogeneous sample would have been preferable for more precise analysis. This study was limited to healthy subjects and did not include subjects with respiratory diseases, so it is not possible to clearly show the extent of clinically significant changes. And, in this study, we did not measure NO concentrations at flow rates other than 50 ml/s, so we could not obtain information on Jaw and Daw.

Given these constraints, future studies should involve larger sample sizes and aim to balance age groups to obtain more reliable and accurate results. However, despite these limitations, this study holds significant value for several reasons. Firstly, it represents an attempt to analyze diurnal variation using data from healthy individuals, which is a relatively novel approach in the field. By examining how FeNO fluctuates across different times of the day, we have provided insights into the natural variability of FeNO levels. Moreover, the study highlights the individual differences in FeNO measurements, an important factor that has often been overlooked in previous research. Understanding these individual variations can be crucial in interpreting FeNO data, particularly when considering its potential for use in clinical applications such as asthma diagnosis or remote monitoring [

43,

44,

45,

46].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed NO levels (total 305 cases) of eight subjects measured at four different times in order to clarify the existence of diurnal variations in NO levels in healthy individuals and to examine the applicability of NO measurements to telemedicine. The results of the analysis showed that NO levels varied greatly between individuals, with no significant differences between groups. In addition, it was revealed that NO levels showed particularly large variations in the morning. These results differ from previous studies showing diurnal variations in breath temperature. Further research is needed to clarify the factors behind individual differences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y.; methodology, E.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, E.Y., Y.Y.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, E.Y.; resources, E.Y.; data curation, T.A., Y.I., H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, E.Y.; project administration, E.Y.; funding acquisition, E.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mie University Faculty of Engineering (No.132, 2/19/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results in this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author via email. Access to the data is restricted to research purposes only.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MacKinnon, G.E.; Brittain, E.L. Mobile Health Technologies in Cardiopulmonary Disease. Chest 2020, 157(3), 654-664. [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Feldman, D.I.; Sayed, A. Digital Health: From Remote Monitoring to Remote Care. J. Card. Fail. 2025, 31(2), 489-491. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T.; Yopes, M.C. Direct-to-Consumer Telemedicine. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7(8), 2546-2552. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Jayasena, R.; Chen, S.H.; Maiorana, A.; Dowling, A.; Layland, J.; Good, N.; Karunanithi, M.; Edwards, I. The Effects of Telemonitoring on Patient Compliance With Self-Management Recommendations and Outcomes of the Innovative Telemonitoring Enhanced Care Program for Chronic Heart Failure: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22(7), e17559. [CrossRef]

- Janjua, S.; Carter, D.; Threapleton, C.J.; Prigmore, S.; Disler, R.T. Telehealth interventions: remote monitoring and consultations for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, CD013196. [CrossRef]

- Cowie, M.R.; Lam, C.S.P. Remote monitoring and digital health tools in CVD management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18(7), 457-458. [CrossRef]

- Puckett, J.L.; George, S.C. Partitioned exhaled nitric oxide to non-invasively assess asthma. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008, 163(1-3), 166-177. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.07.020.

- Popov, T.A.; Dunev, S.; Kralimarkova, T.Z.; Kraeva, S.; DuBuske, L.M. Evaluation of a simple, potentially individual device for exhaled breath temperature measurement. Respir Med. 2007, 101(10), 2044-2050. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.005.

- Carpagnano, G.E.; Foschino-Barbaro, M.P.; Crocetta, C.; Lacedonia, D.; Saliani, V.; Zoppo, L.D.; Barnes, P.J. Validation of the Exhaled Breath Temperature Measure: Reference Values in Healthy Subjects. Chest. 2017, 151(4), 855-860. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.013.

- Davis, M.D.; Hunt, J. Exhaled breath condensate pH assays. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012, 32(3), 377-386. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2012.06.003.

- Popov, T.A. Human exhaled breath analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011, 106(6), 451-456. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.02.016.

- Lehtimäki, L.; Karvonen, T.; Högman, M. Clinical Values of Nitric Oxide Parameters from the Respiratory System. Curr Med Chem. 2020, 27(42), 7189-7199. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200603141847.

- Stewart, L.; Katial, R.K. Exhaled nitric oxide. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2012, 32(3), 347-362. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2012.06.005.

- Hoyte, F.C.L.; Gross, L.M.; Katial, R.K. Exhaled Nitric Oxide: An Update. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2018, 38(4), 573-585. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2018.06.001.

- García-Río, F.; Casitas, R.; Romero, D. Utility of two-compartment models of exhaled nitric oxide in patients with asthma. J Asthma. 2011, 48(4), 329-334. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.565847.

- Wyszyńska, M.; Nitsze-Wierzba, M.; Czelakowska, A.; Kasperski, J.; Żywiec, J.; Skucha-Nowak, M. An Evidence-Based Review of Application Devices for Nitric Oxide Concentration Determination from Exhaled Air in the Diagnosis of Inflammation and Treatment Monitoring. Molecules. 2022, 27(13), 4279. doi: 10.3390/molecules27134279.

- Pontier, J.M.; Buzzacott, P.; Nastorg, J.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Lambrechts, K. Exhaled nitric oxide concentration and decompression-induced bubble formation: An index of decompression severity in humans? Nitric Oxide. 2014, 39, 29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.04.005.

- Baraldi, E.; Carraro, S. Exhaled NO and breath condensate. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006, 7(Suppl 1), S20-S22. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2006.04.017.

- Popov, T.A.; Kralimarkova, T.Z.; Labor, M.; Plavec, D. The added value of exhaled breath temperature in respiratory medicine. J Breath Res. 2017, 11(3), 034001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa7801.

- Amann, A.; Miekisch, W.; Schubert, J.; Buszewski, B.; Ligor, T.; Jezierski, T.; Pleil, J.; Risby, T. Analysis of exhaled breath for disease detection. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif). 2014, 7, 455-482. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-071213-020043.

- Tonacci, A.; Sansone, F.; Pala, A.P.; Conte, R. Exhaled breath analysis in evaluation of psychological stress: A short literature review. Int J Psychol. 2019, 54(5), 589-597. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12494.

- Minh, T.D.C.; Blake, D.R.; Galassetti, P.R. The clinical potential of exhaled breath analysis for diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012, 97(2), 195-205. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.02.006.

- Paleczek, A.; Rydosz, A. Review of the algorithms used in exhaled breath analysis for the detection of diabetes. J Breath Res. 2022, 16(2), 025003. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ac4916.

- Emilsson, Ö.I.; Kokelj, S.; Östling, J.; Olin, A.C. Exhaled biomarkers in adults with non-productive cough. Respir Res. 2023, 24(1), 65. doi: 10.1186/s12931-023-02341-5.

- Peng, L.; Jiang, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Online Measurement of Exhaled NO Concentration and Its Production Sites by Fast Non-equilibrium Dilution Ion Mobility Spectrometry. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 23095. doi: 10.1038/srep23095.

- Zitt, M. A Perspective on Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide Measurement for Adherence Monitoring. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017, 5(2), 523-524. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.10.014.

- MacBean, V.; Pooranampillai, D.; Howard, C.; Lunt, A.; Greenough, A. The influence of dilution on the offline measurement of exhaled nitric oxide. Physiol Meas. 2018, 39(2), 025004. doi: 10.1088/1361-6579/aaa455.

- Zhang, D.; Luo, J.; Qiao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, R.; Zhong, X. Measurement of exhaled nitric oxide concentration in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96(12), e6429. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006429.

- Couillard, S.; Laugerud, A.; Jabeen, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Melhorn, J.; Hinks, T.; Pavord, I. Derivation of a prototype asthma attack risk scale centred on blood eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide. Thorax. 2022, 77(2), 199-202. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217325.

- Guida, G.; Carriero, V.; Bertolini, F.; Pizzimenti, S.; Heffler, E.; Paoletti, G.; Ricciardolo, F.L.M. Exhaled nitric oxide in asthma: from diagnosis to management. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 23(1), 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Tsoukias, N. M.; George, S. C. A Two-Compartment Model of Pulmonary Nitric Oxide Exchange Dynamics. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 653–665.

- Baron, R.; Haick, H. Mobile Diagnostic Clinics. ACS Sens. 2024, 9(6), 2777-2792. [CrossRef]

- Sapci, A.H.; Sapci, H.A. Digital continuous healthcare and disruptive medical technologies: m-Health and telemedicine skills training for data-driven healthcare. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25(10), 623-635. [CrossRef]

- Tsoukias, N.M.; George, S.C. A two-compartment model of pulmonary nitric oxide exchange dynamics. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85(2), 653-660. [CrossRef]

- Rottier, B.L.; Cohen, J.; van der Mark, T.W.; Douma, W.R.; Duiverman, E.J.; ten Hacken, N.H. A different analysis applied to a mathematical model on output of exhaled nitric oxide. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99(1), 378-379. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.W.; Condorelli, P.; Rose-Gottron, C.M.; Cooper, D.M.; George, S.C. Probing the impact of axial diffusion on nitric oxide exchange dynamics with heliox. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 97(3), 874-882. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.W.; George, S.C. Impact of axial diffusion on nitric oxide exchange in the lungs. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93(6), 2070-2080. [CrossRef]

- George, S.C.; Hogman, M.; Permutt, S.; Silkoff, P.E. Modeling pulmonary nitric oxide exchange. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 96(3), 831-839. [CrossRef]

- Dweik, R.A.; Boggs, P.B.; Erzurum, S.C.; Irvin, C.G.; Leigh, M.W.; Lundberg, J.O.; Olin, A.C.; Plummer, A.L.; Taylor, D.R.; American Thoracic Society Committee on Interpretation of Exhaled Nitric Oxide Levels (FENO) for Clinical Applications. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184(5), 602-615. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M.; Piacentini, G.; Chiossi, L.; Ruggeri, F.; Caiazzo, I.; Campisano, M.; Martella, S.; Villa, M.P. Tidal-breathing measurement of exhaled breath temperature (EBT) in schoolchildren. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014, 49(12), 1196-1204. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22994.

- Carpagnano, G.E.; Lacedonia, D.; Malerba, M.; Martinelli, D.; Cotugno, G.; Foschino-Barbaro, M.P. Exhaled breath temperature measurement: influence of circadian rhythm. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2017, 31(1), 229-235.

- Yang, S. Y.; Kim, Y. H.; Byun, M. K.; Kim, H. J.; Ahn, C. M.; Kim, S. H.; Lee, H. S.; Park, H. J. Repeated Measurement of Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide Is Not Essential for Asthma Screening. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 28(2), 98–105. [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Gil, J.M.; Fernandez-Nieto, M.; Acevedo, N. Understanding the Cellular Sources of the Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO) and Its Role as a Biomarker of Type 2 Inflammation in Asthma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5753524. [CrossRef]

- Celis-Preciado, C.A.; Lachapelle, P.; Couillard, S. Exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO): Bridging a knowledge gap in asthma diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53(8), 791-793. [CrossRef]

- Bacharier, L.B.; Pavord, I.D.; Maspero, J.F.; Jackson, D.J.; Fiocchi, A.G.; Mao, X.; Jacob-Nara, J.A.; Deniz, Y.; Laws, E.; Mannent, L.P.; Amin, N.; Akinlade, B.; Staudinger, H.W.; Lederer, D.J.; Hardin, M. Blood eosinophils and fractional exhaled nitric oxide are prognostic and predictive biomarkers in childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154(1), 101-110. [CrossRef]

- Harnan, S.E.; Essat, M.; Gomersall, T.; Tappenden, P.; Pavord, I.; Everard, M.; Lawson, R. Exhaled nitric oxide in the diagnosis of asthma in adults: a systematic review. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2017, 47(3), 410-429. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).