Submitted:

12 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and apparatus

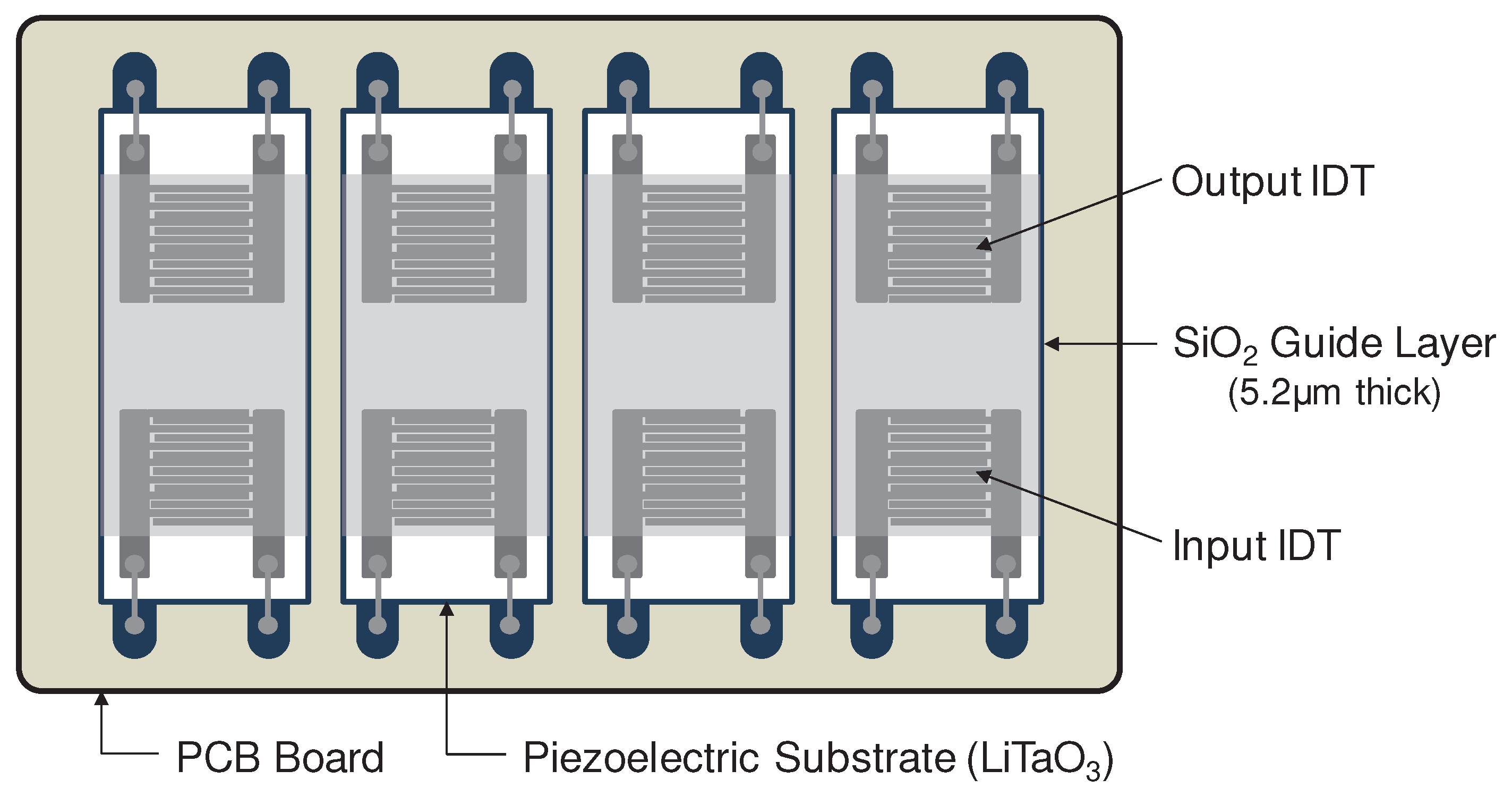

2.2. Design and fabrication of SAW sensor array

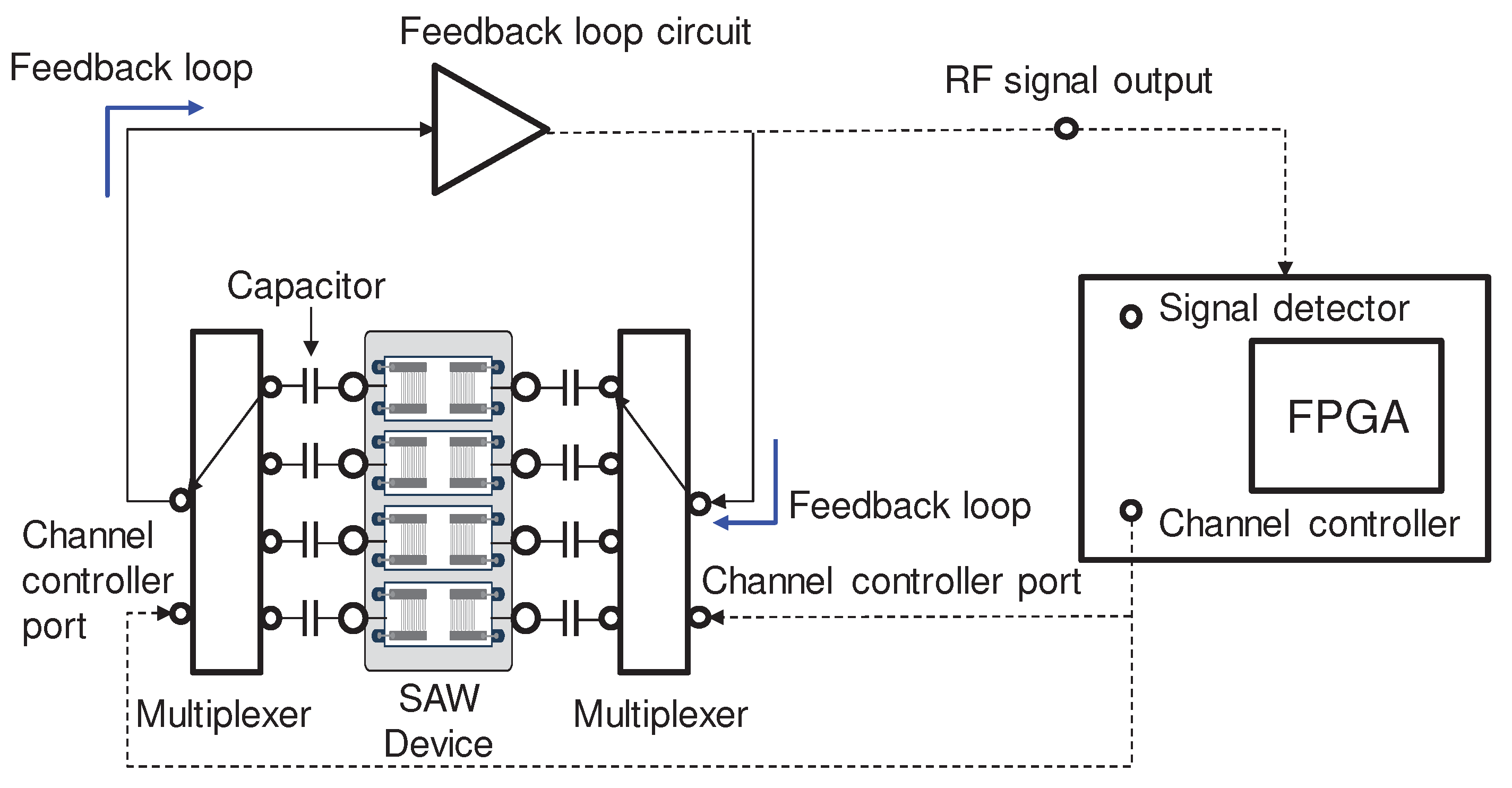

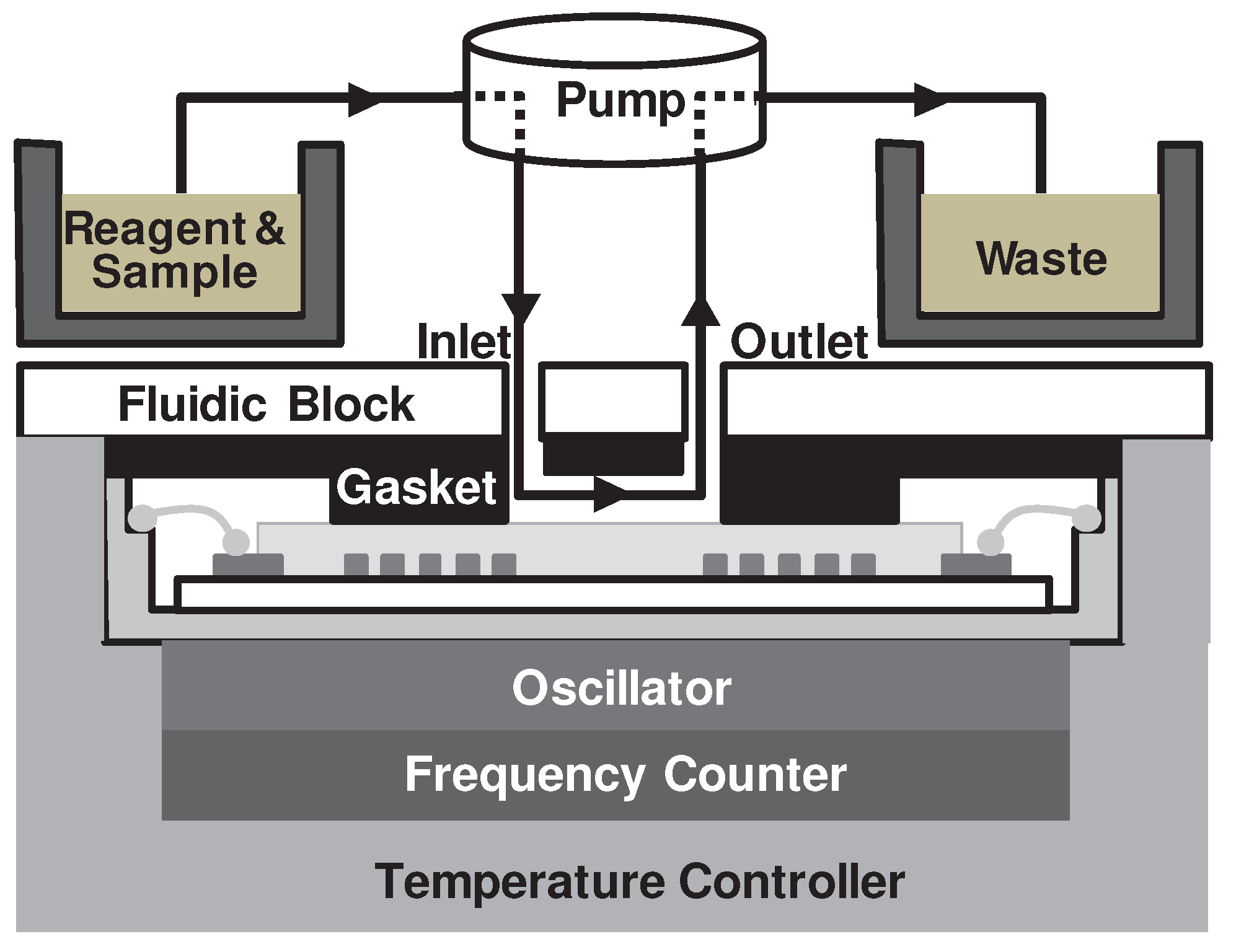

2.3. Sensing and fluidic blocks of the SAW sensor array

2.4. Immobilization of capture probes on SiO2 - coated SAW sensor array and conjugation of detecting probes on TiO2 nanoparticles

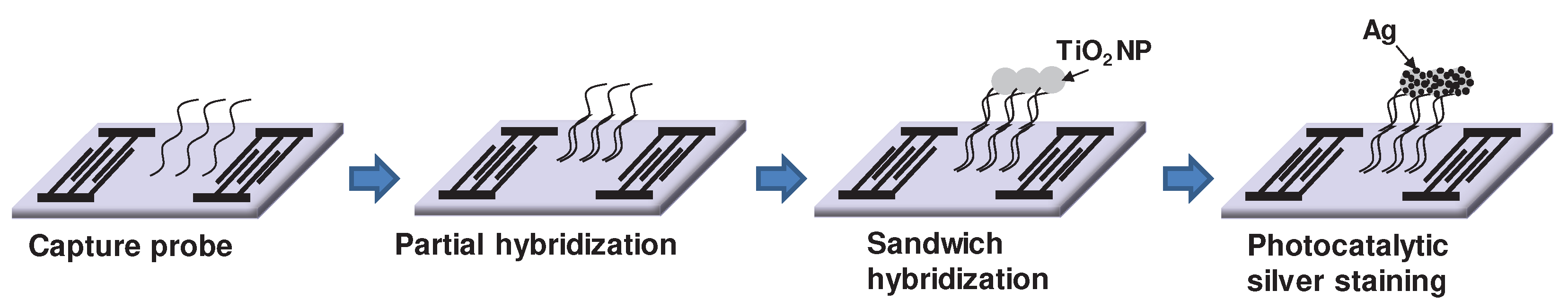

2.5. Sandwich hybridization with photocatalytic silver staining

2.6. Detection of miRNAs using exosomal miRNAs extracted from a MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cell line

3. Results

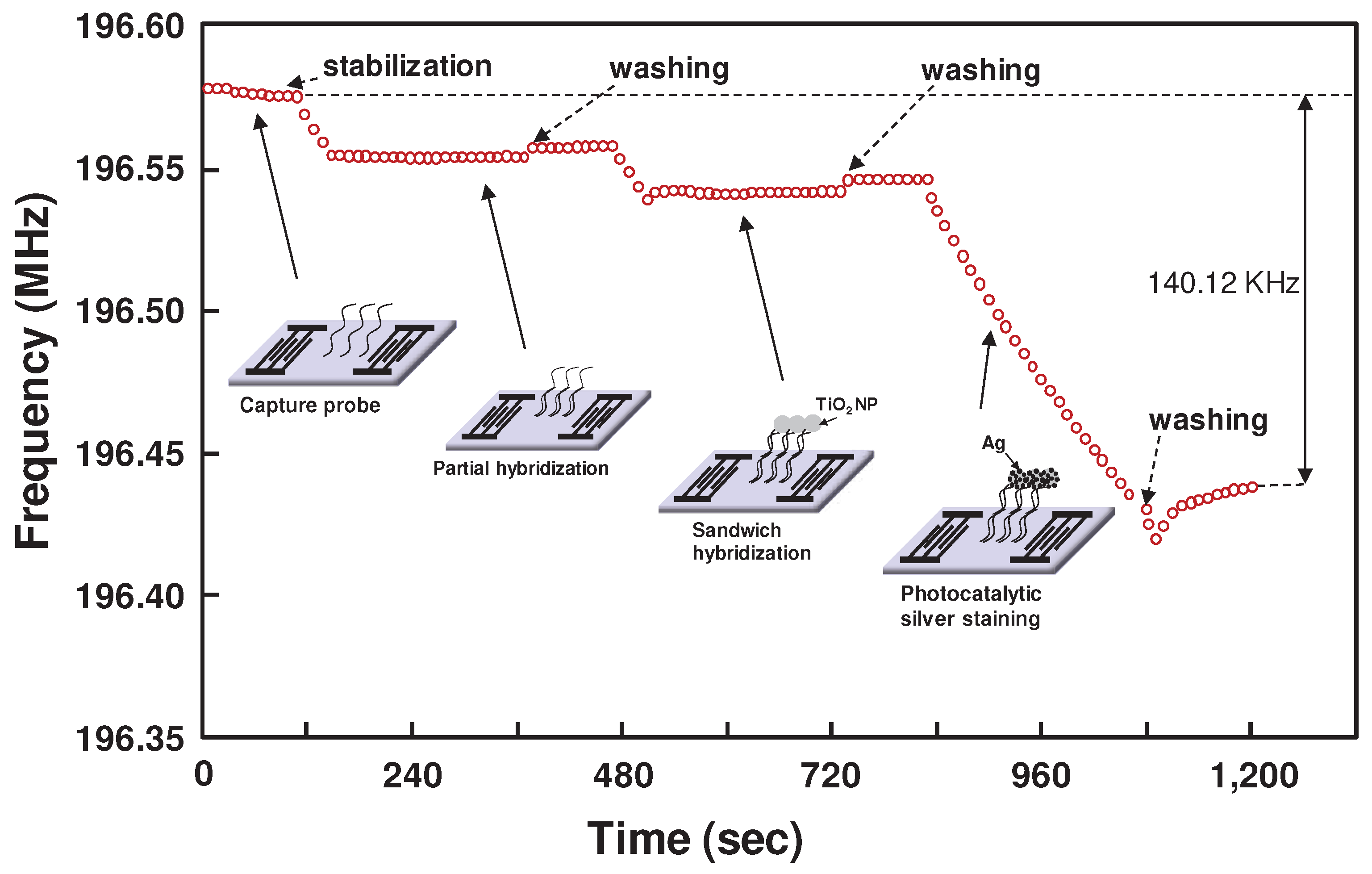

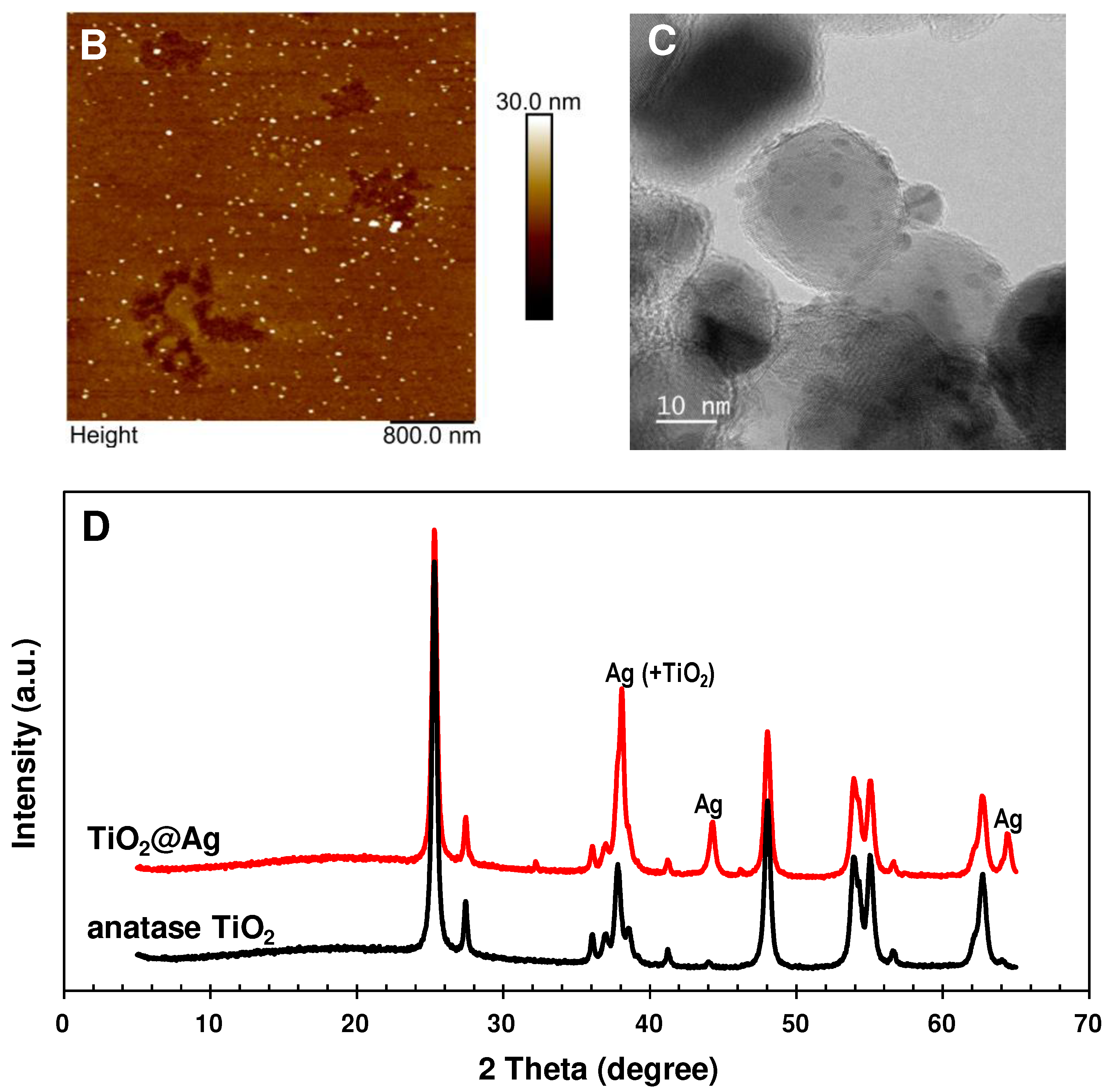

3.1. Detection of miRNAs by sandwich hybridization and photocatalytic silver staining

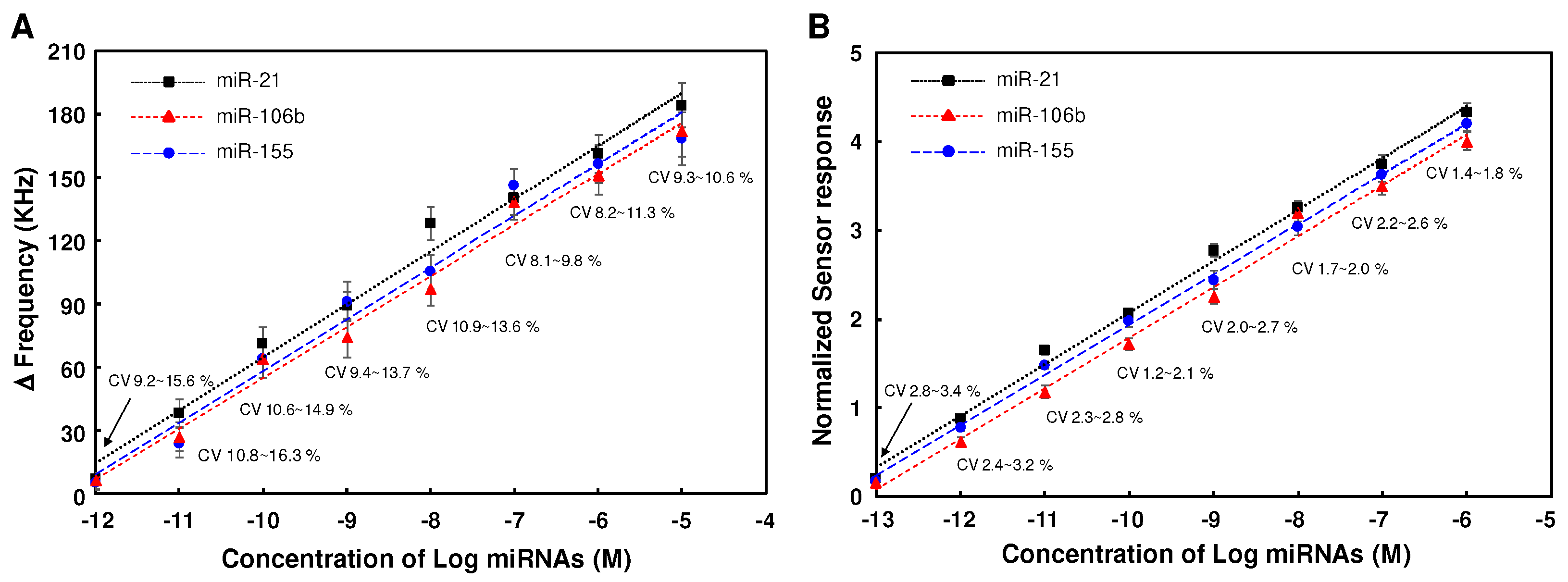

3.2. Evaluation of the response of SAW sensors on the concentration of miRNAs

3.3. Effect of normalization on the reproducibility for detecting miRNAs in SAW sensor array

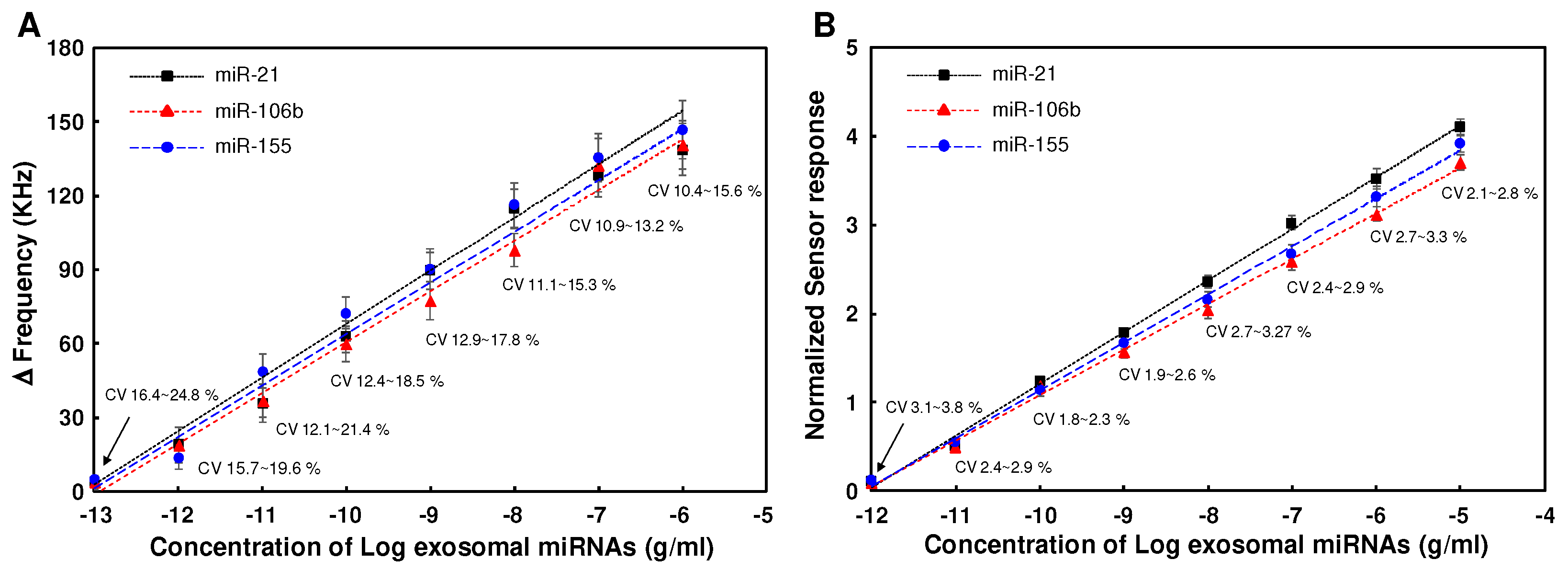

3.4. Detection of miR-21, miR-106b and miR-155 in cancer cell-derived exosomal miRNA samples using SAW sensor array

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, A.P.F. Biosensors: sense and sensibility. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3184–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Yang, L.; Wang, P. Nucleic acid molecular systems for in vitro detection of biomolecules. ACS Mater. Au. 2023, 3, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, R. Recent optical sensing technologies for the detection of various biomolecules: review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poghossian, A.; Schöning, M.J. Label-free sensing of biomolecules with field-effect devices for clinical applications. Electroanalysis 2014, 26, 1197–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Slaughter, G. Label-free microRNA optical biosensors. Nanomater. 2019, 9, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvi, F.; Jafari, K. A measurement platform for label-free detection of biomolecules based on a novel optical bioMEMS sensor. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 7501407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. SPR biosensors: historical perspectives and current challenges, Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 229, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.S. Label-free quantitative detection of nucleic acids based on surface-immobilized DNA intercalators. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 241, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, S.S. A quartz crystal microbalance-based biosensor for enzymatic detection of hemoglobin A1c in whole blood. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 258, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.; Lee, S.S. Highly sensitive piezoelectric immunosensors employing signal amplification with gold nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2019, 30, 445502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, S.S. QCM sensing of miR-21 by formation of microRNA–DNA hybrid duplexes and intercalation on surface-functionalized pyrene. Analyst 2019, 144, 6936–6943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, S.S. Strategic approaches for highly selective and sensitive detection of Hg2+ ion using mass sensitive sensors. Anal. Sci. 2019, 35, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.Y.; Lee, S.S. Quartz crystal microbalance cardiac Troponin I immunosensors employing signal amplification with TiO2 nanoparticle photocatalyst. Talanta 2021, 35, 122233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Länge, K.; Rapp, B.E.; Rapp, M. Surface acoustic wave biosensors: a review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 391, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Namkoong, K.; Cho, E.C.; Ko, C.; Park, J.C.; Lee, S.S. Surface acoustic wave immunosensor for real-time detection of hepatitis B surface antibodies in whole blood samples. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 3120–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.N.; Kim, S.K.; Han, K.Y.; Cho, E.C.; Park, J.C.; Lee, S.S. Sensitive and simultaneous detection of cardiac markers in human serum using surface acoustic wave immunosensor. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 8629–8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Park, J.-Y.; Seo, H.; Lee, T.; Lee, W.; Kim, S.K.; Hahn, Y.K.; Jung, J.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, S.S. Sensitive and reproducible detection of cardiac troponin I in human plasma using a surface acoustic wave immunosensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 178, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Jung, J.; Hahn, Y.K.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, T.; Park, J.-Y.; Seo, H.; Lee, J.N.; Oh, J.H.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, S.S. A centrifugally actuated point-of-care testing system for the surface acoustic wave immunosensing of cardiac troponin I. Analyst. 2013, 138, 2558–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Kwak, J.; Lee, S.S. Increase in detection sensitivity of surface acoustic wave biosensor using triple transit echo wave. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 113, 083702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.C.; Gizeli, E.; Goddard, N.J.; Lowe, C.R. Acoustic love plate sensors: a theoretical model for the optimization of the surface mass sensitivity. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1993, 13-14, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizeli, E.; Stevenson, A.C.; Goddard, N.J.; Lowe, C.R. Acoustic love plate sensors: comparison with other acoustic devices utilizing surface SH waves. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1993, 13-14, 638–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizeli, E.; Stevenson, A.C.; Goddard, N.J.; Lowe, C.R. A novel love plate acoustic sensor utilizing polymer overlayers. IEEE Trans. UFFC. 1992, 39, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.; Venema, A. Theoretical comparison of sensitivities of acoustic shearwave modes for (bio)chemical sensing in liquids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 61, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.; Vellekoop, M.J.; Haueis, R.; Lubking, G.W.; Venema, A. A Love-wave sensor for (bio)chemical sensing in liquids. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 1994, 43, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Luo, J.K.; Du, X.Y.; Flewitt, A.J.; Li, Y.; Markx, G.H.; Walton, A.J.; Milne, W.I. Recent developments on ZnO films for acoustic wave based bio-sensing and microfluidic applications: a review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 143, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Länge, K. Grimm, S.; Rapp, M. Chemical modification of parylene C coatings for SAW biosensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 125, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Hannon, G.J. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004, 5, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.-W.; MacRae, I.J. The molecular machines that mediate microRNA maturation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F.; Shehzad, A.; Khan, T.; Kim, Y.Y. MicroRNAs: synthesis, mechanism, function, and recent clinical trials. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1803, 1231–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennecke, J.; Hipfner, D.R.; Stark, A.; Russell, R.B.; Cohen, S.M. Bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 2003, 113, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Carthew, R.W. A microRNA mediates EGF receptor signaling and promotes photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Cell 2005, 123, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cissell, K.A.; Shrestha, S.; Deo, S.K. MicroRNA detection: challenges for the analytical chemist. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 4754–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamizawa, J.; Konishi, H.; Yanagisawa, K.; Tomida, S.; Osada, H.; Endoh, H.; Harano, T.; Yatabe, Y.; Nagino, M.; Nimura, Y. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 3753–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Getz, G.; Miska, E.A.; Alvarez-Saavedra, E.; Lamb, J.; Peck, D.; Sweet-Cordero, A.; Ebert, B.L.; Mak, R.H.; Ferrando, A.A.; Downing, J.R; Jacks, T.; Horvitz, H.R.; Golub, T.R. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005, 435, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volinia, S.; Calin, G.A.; Liu, C.-G.; Ambs, S.; Cimmino, A.; Petrocca, F.; Visone, R.; Iorio, M.; Roldo, C.; Ferracin, M.; Prueitt, R.L; Yanaihara, N.; Lanza, G.; Scarpa, A.; Vecchione, A.; Negrini, M.; Harris, C.C.; Croce, C.M. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricoli, J.V.; Jacobson, J.W. MicroRNA: Potential for cancer detection, diagnosis, and prognosis. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4553–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ba, Y.; Ma, L.; Cai, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Shang, X.; Gong, T.; Ning, G.; Wang, J.; Zen, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.-Y. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Daniel, W.L.; Mirkin, C.A. A Microarray-based multiplexed scanometric immunoassay for protein cancer markers using gold nanoparticle probes. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9183–9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, K.V.; Boro, R.; Thampi, K.R.; Raje, M.; Varshney, G.C.; Suri, C.R. Immunochromatographic dipstick assay format using gold nanoparticles labeled protein-hapten conjugate for the detection of atrazine. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 5028–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, D.W.; Brozik, S.M. Low-level detection of a Bacillus anthracis simulant using Love-wave biosensors on 36° YX LiTaO3. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004, 19, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.; Gupta, V.B. Methods for the determination of limit of detection and limit of quantitation of the analytical methods. Chron. Young Sci. 2011, 2, 21–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Z.; Guo, L.; Lin, Z.; Qiu, B.; Chen, G. Enzyme-free fluorescent biosensor for miRNA-21 detection based on MnO2 nanosheets and catalytic hairpin assembly amplification. Anal. Methods. 2016, 8, 8492–8497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Sun, H.; Xu, L.; Yue, Q.; Shen, G.; Li, M.; Tang, B.; Li, C.-Z. In situ monitoring of cytoplasmic precursor and mature microRNA using gold nanoparticle and graphene oxide composite probes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1021, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Xu, T.; Liu, X.; Yu, X.; Li, R.; Deng, J.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Y. Rapid and ultrasensitive detection of microRNA based on strand displacement amplification-mediated entropy-driven circuit reaction. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 3057–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, M.; Campuzano, S.; Pingarrón, J. M.; Raouafi, N. Amperometric biosensing of miRNA-21 in serum and cancer cells at nanostructured platforms using anti-DNA–RNA hybrid antibodies. ACS Omega. 2018, 3, 8923–8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md. N.; Masud, M.K.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Gopalan, V.; Alamri, H.R.; Alothman, Z.A.; Hossain, Md. S.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Lamd, A.K.; Shiddiky, M.J.A. Gold-loaded nanoporous ferric oxide nanocubes for electrocatalytic detection of microRNA at attomolar level. Biosens Bioelectron, 2018, 101, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, K.M.; Carrascosa, L.G.; Shiddiky, M.J.A.; Trau, M. Poly(A) extensions of miRNAs for amplification-free electrochemical detection on screen-printed gold electrodes. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 2000–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, S. S. Detection of miR-155 using two types of electrochemical approaches. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2020, 41, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, B.; Dudak, F.C.; Boyaci, I.H.; Tamerc, U.; Ozsoz, M. SERS-based direct and sandwich assay methods for mir-21 detection. Analyst 2014, 139, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, A.; Cheema, J.A.; Rajwar, D.; Ammanath, G.; Xiaohu, L.; Koon, L.S.; Yi, W.; Yildizd, U.H.; Liedberg, B. Polythiophene derivative on quartz resonators for miRNA capture and assay. Analyst. 2015, 140, 7912–7917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premaratnea, G.; Mubaraka, Z.H.A.; Senavirathnab, L.; Liub, L.; Krishnan, S. Measuring ultra-low levels of nucleotide biomarkers using quartz crystal microbalance and SPR microarray imaging methods: A comparative analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 253, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.B.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.S. Electrochemical detection of miRNA-21based on molecular beacon formed by thymine-mercury(II)-thymine base pairing. Electroanalysis. 2023, 35, e202300011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, C.K.; Hobbs, K.; Trent, J.F. Biological differences among MCF-7 human breast cancer cell lines from different laboratories. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1987, 9, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Miao, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Jia, L. MiR-106b and miR-93 regulate cell progression by suppression of PTEN via PI3K/Akt pathway in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analytical Techniques | Target miRNA | Linear Range (pM) | LOD (pM) | Ref. |

| Fluoresence | miR-21 | 1,000 – 50,000 | 330 | 43 |

| Fluoresence Fluoresence Electrochemical Electrochemical Electrochemical Electrochemical Electrochemical QCM SPR SERS SAW SAW SAW |

miR-21 miR-106b miR-21 miR-107 miR-107 miR-155 miR-21 miR-21 miR-21 miR-21 miR-21 miR-106b miR-155 |

0 – 30,0000 0.001 – 1,000 0.096 – 25 0 – 1,000 0.005 – 5 0.5 – 25,000 0.1 – 10 1,000 – 10,000 0 – 1.8 4,440 – 1,480,000 0.1 – 1,000,000 0.1 – 1,000,000 0.1 – 1,000,000 |

4,500 0.00044 0.029 0.0001 0.01 0.96 0.64 400 0.047 850 0.012 0.026 0.015 |

44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 This work “ “ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).