Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

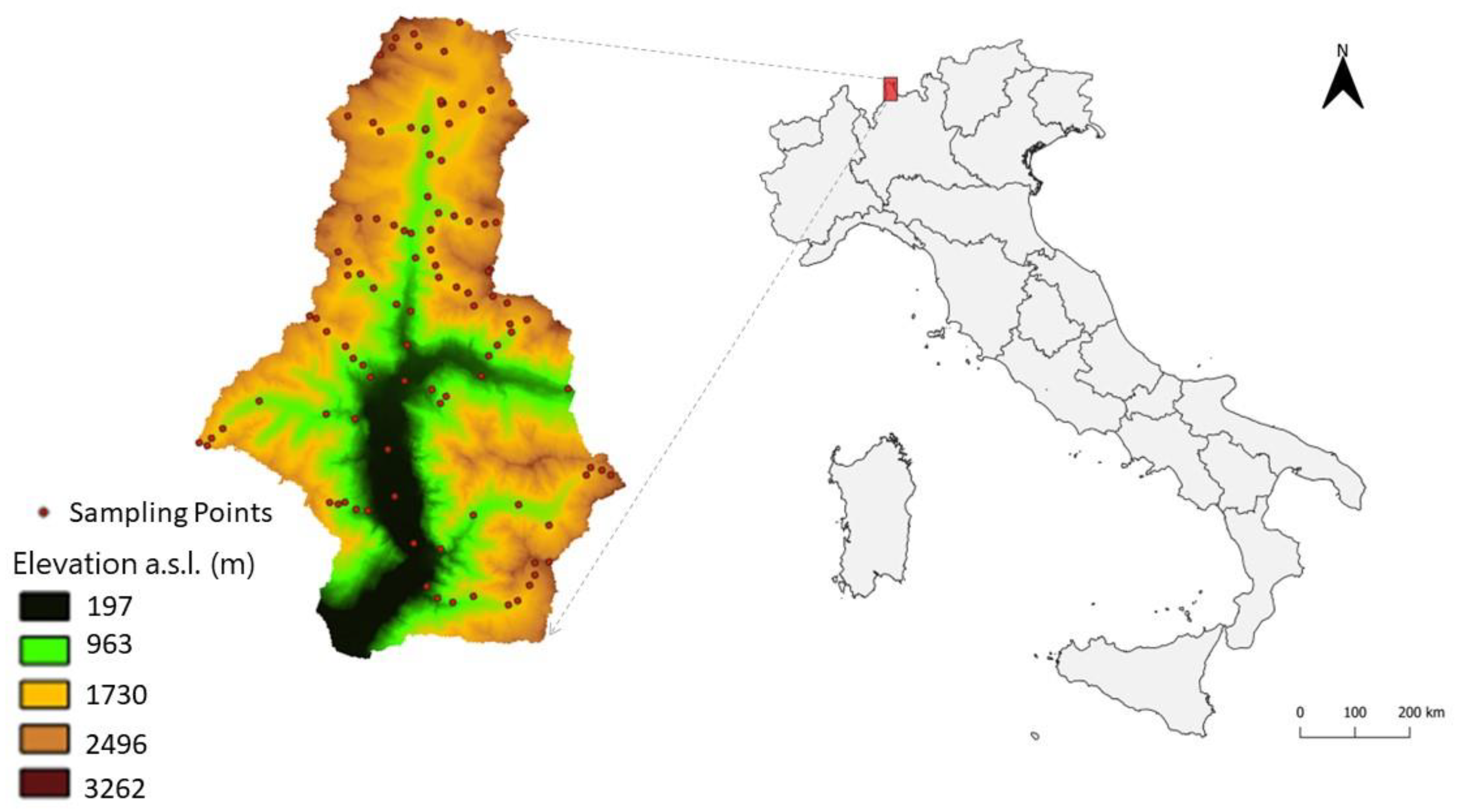

2.1. Study area

2.2. DSM approaches in SOC stock mapping

- soil survey and laboratory analyses;

- calculation of SOC stock at each sampling point;

- calculation and selection of environmental covariates;

- preparation of the covariate maps (with a spatial resolution of 20 x 20 m);

- extraction of the environmental covariates at each soil sampling point;

- selection of the covariates;

- comparison of different machine learning models to estimate the SOC stocks;

- spatialization of the SOC stocks;

- obtaining estimation uncertainty maps.

2.2.1. Soil survey and data collection strategy

2.2.2. Laboratory analysis methods

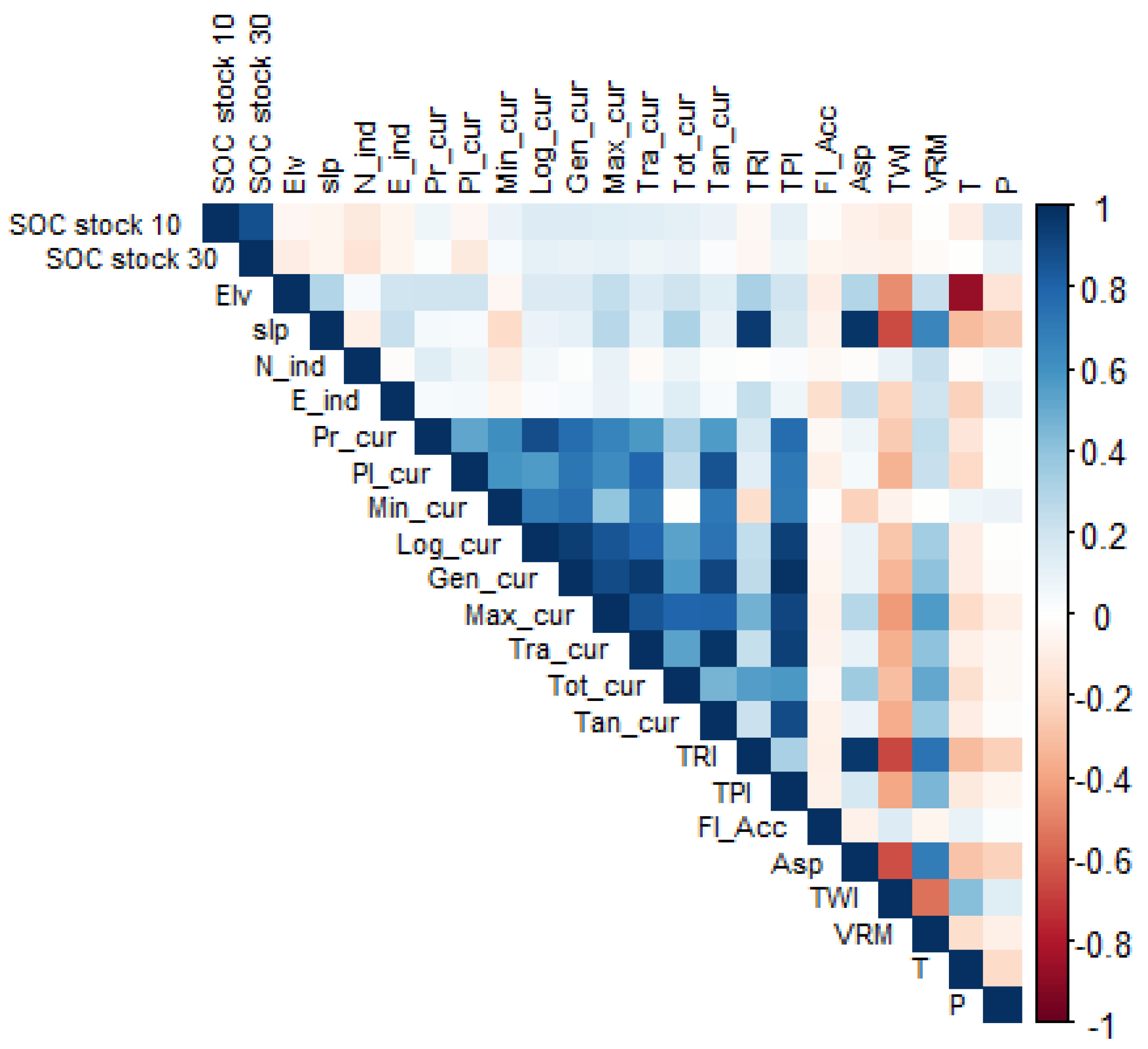

2.2.3. Environmental covariates

- Geomorphometric covariates: to calculate these covariates we used the digital terrain model (DTM), delivered from the regional geo-portal of Lombardy (www.geoportale.regione.lombardia.it), and extracted 16 morphometric parameters. The calculation was carried out in QGIS 3.16.1 using the integrated SAGA tool.

- Climatic covariates: we used mean annual air temperature (T) and precipitation (P) delivered from WorldClim (www.worldclim.org) with spatial resolution of 1 km2. We applied a statistical downscaling technique using a 30-year time series of climatic data registered at seven meteorological stations in Valchiavenna, to obtain climatic covariate maps with the same spatial resolution as the other environmental variables (20 m). Working in an alpine valley, the downscaling technique was based on statistical correlations between climatic variables with the elevation and also with latitude and longitude [23]. The results of the correlations were used to obtain T and P maps of the area, correcting the estimated values for slope and exposure, which have a direct impact on microclimatic conditions in mountainous environments [24]. The equations used for climate downscaling are explained in the Supplementary materials (Eq S1 - Eq S5).

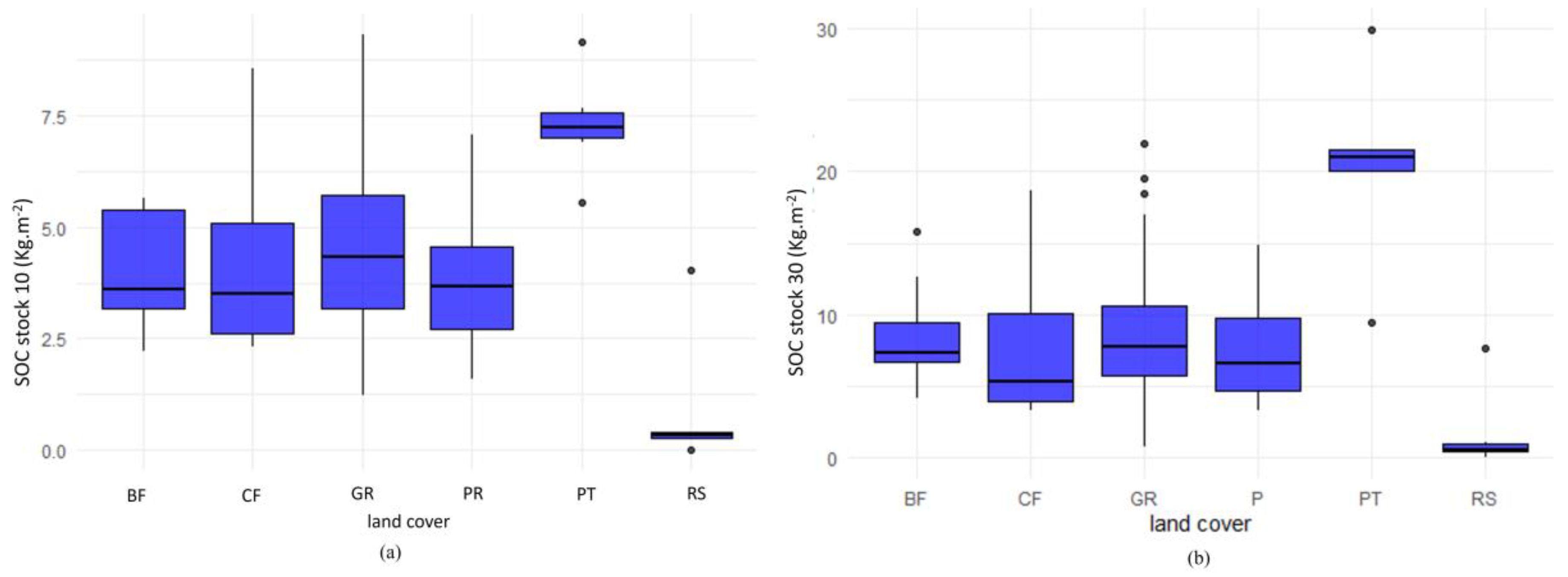

- Land cover covariates: we used the most recent land cover maps of Lombardy, related to agricultural and forestry use (DUSAF 7.0) [25] and identified six land cover classes in the study area: broadleaf forests, coniferous forests, grasslands (low elevation), prairies (high elevation), peatlands, and rocky soils.

2.2.4. Covariates selections and modeling approaches

- Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS). In 1991, Friedman unveiled a new methodology that amalgamated linear regression with spline mathematical modeling through binary recursive partitioning [26]. This method constructs a model step by step, assessing variable importance and regularization to unimportant covariates. MARS is flexible, identifying complex nonlinear interactions between input variables, and it requires minimal pre-processing. Until now, the MARS model has not been widely applied in soil properties prediction [27,28].

- Elastic Net Model (ENET). The model was introduced by Zou and Hastie in 2005 [29]. Similar to Lasso and Ridge Regression, it employs a regulation and variable selection technique, choosing the most advantageous combination of the two models. For studies with few observations and a high number of predictors, it is advised to use this model [29,30,31].

- Random Forests (RF). Proposed by Breiman in 2001 [32], RF is the most used machine learning algorithm in DSM, as it has proven effective in mapping soil properties over an extensive variety of data sources and scales of soil heterogeneity. The model uses decision trees for training, combining them to produce single predictions for each observation in the datasets using an out-of-bag (OOB) strategy [33].

- Support Vector Machine (SVM). An effective machine learning method for mapping soil properties, largely used by soil mappers in recent years [34,35]; it is a kernel-based model, highly used to analyze non-linear relationships over a high-dimensional induced feature space. SVM uses decision surfaces specified by a kernel function [36]. In the DSM approach, SVM is frequently used for classification, but it is also used for regression predictions.

2.2.5. Prediction validation and uncertainties mapping

3. Results

3.1. SOC stock statistical analysis

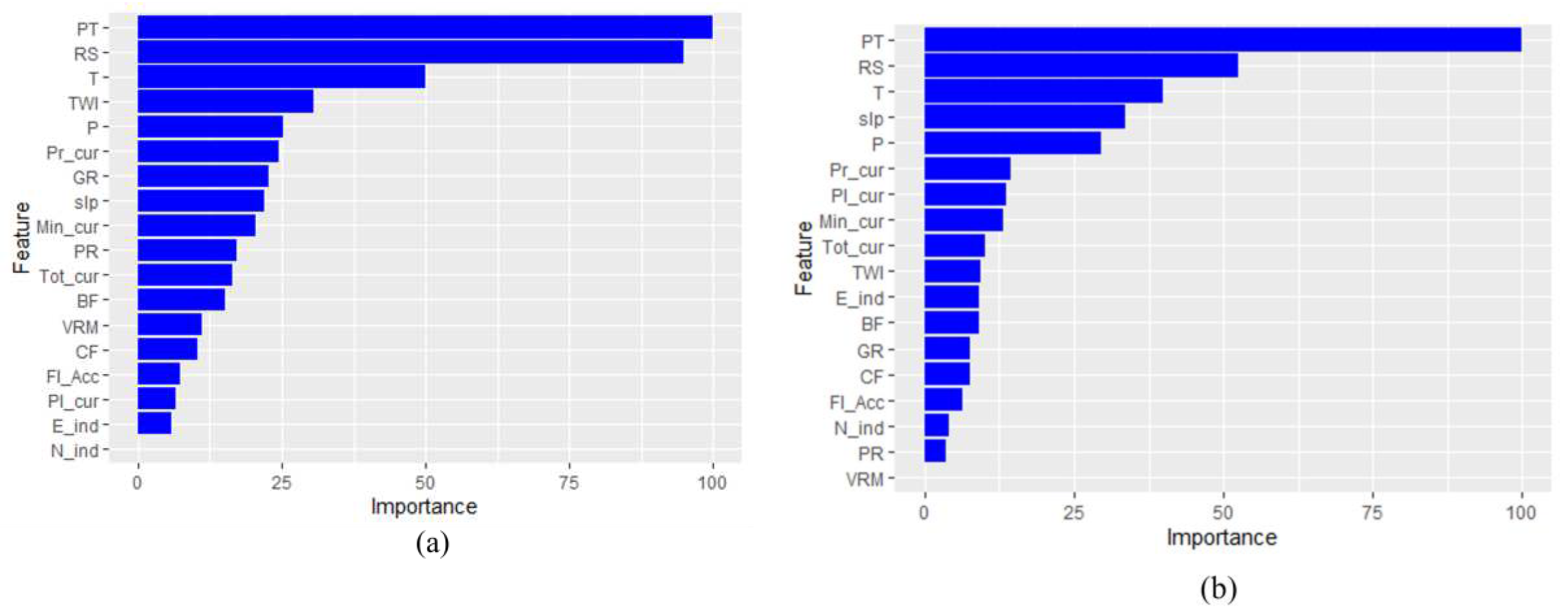

3.2. Models validation and SOC stock prediction

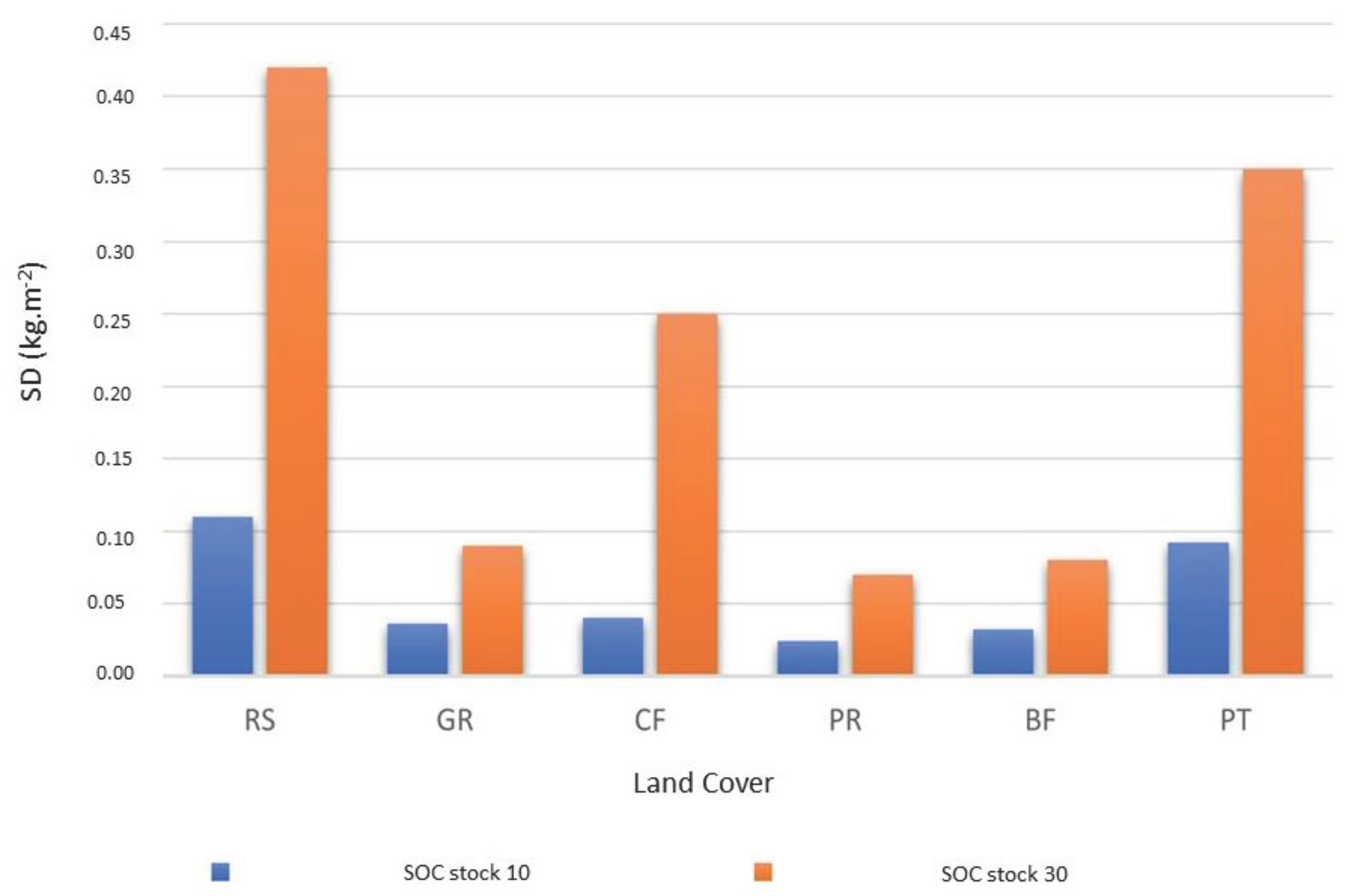

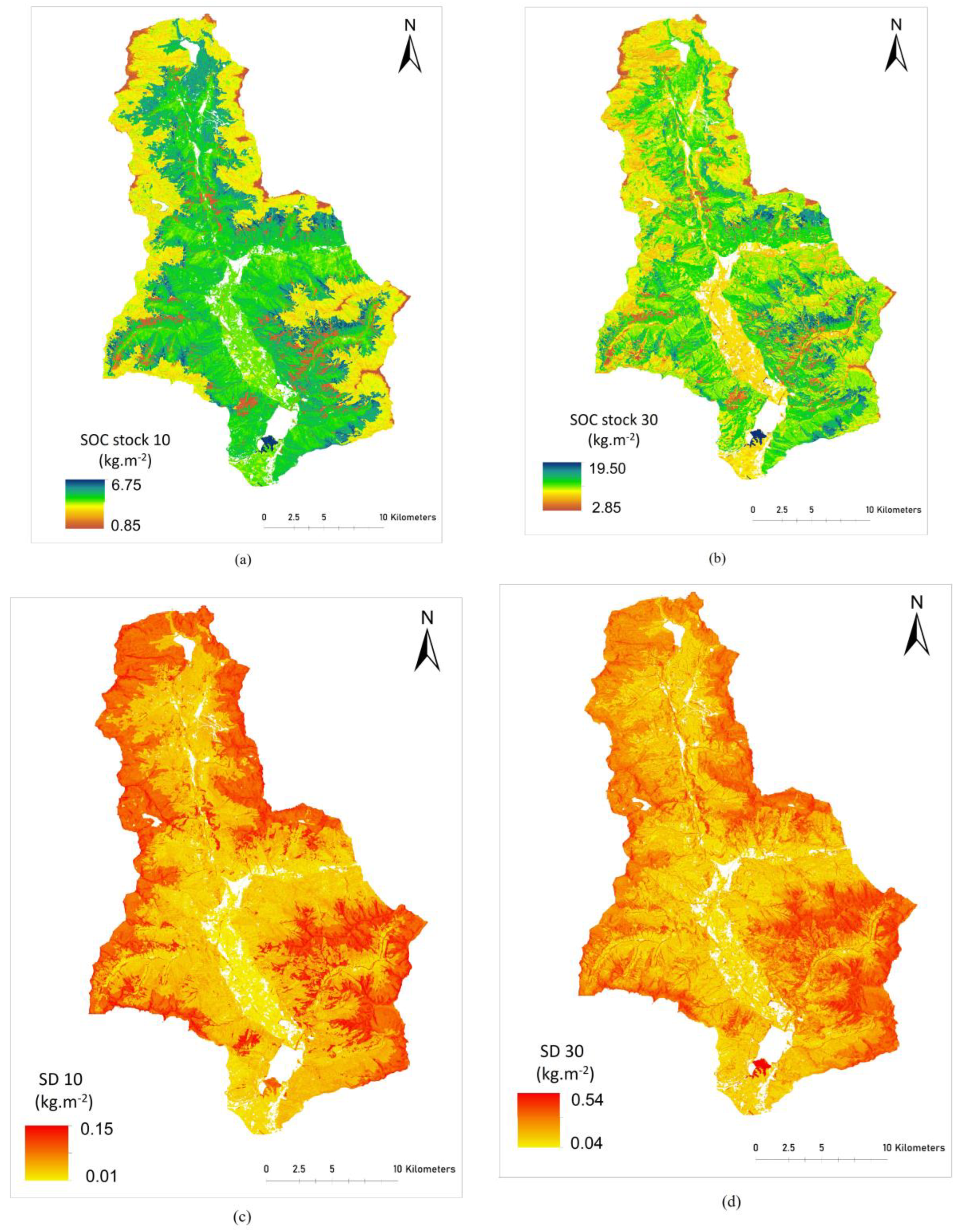

3.3. Maps of SOC stock and uncertainty estimation

4. Discussion

4.1. Models’ performance

4.2. SOC stock spatial distribution: the main drivers and uncertainties

5. Conclusions

References

- Baruck, J. et al. Soil classification and mapping in the Alps: The current state and future challenges. Geoderma 264, 312–331 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R. et al. Understanding Mountain Soils: A contribution from mountain areas to the International Year of Soils 2015. https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1522121 (2015).

- Hartemink, A. E., Gerzabek, M. H., Lal, R. & McSweeney, K. Soil Carbon Research Priorities. in Soil Carbon (eds. Hartemink, A. E. & McSweeney, K.) 483–490 (Springer International Publishing, 2014). [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. et al. The carbon sequestration potential of terrestrial ecosystems. J. Soil Water Conserv. 73, 145A-152A (2018). [CrossRef]

- Alfthan, B. et al. Mountain Adaptation Outlook Series: Synthesis Report. (2018).

- Adler, C., P., Weste, I., Bhatt, C. & Huggel. Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, U., Hoffmann, T., Jurasinski, G., Glatzel, S. & Kuhn, N. J. Assessing the spatial variability of soil organic carbon stocks in an alpine setting (Grindelwald, Swiss Alps). Geoderma 232–234, 270–283 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Lagacherie, P. & McBratney, A. B. Chapter 1 Spatial Soil Information Systems and Spatial Soil Inference Systems: Perspectives for Digital Soil Mapping. in Developments in Soil Science vol. 31 3–22 (Elsevier, 2006).

- D’Amico, M. E., Freppaz, M., Leonelli, G., Bonifacio, E. & Zanini, E. Early stages of soil development on serpentinite: the proglacial area of the Verra Grande Glacier, Western Italian Alps. J. Soils Sediments 15, 1292–1310 (2015). [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, M. E., Freppaz, M., Filippa, G. & Zanini, E. Vegetation influence on soil formation rate in a proglacial chronosequence (Lys Glacier, NW Italian Alps). CATENA 113, 122–137 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. et al. Modeling soil organic carbon spatial distribution for a complex terrain based on geographically weighted regression in the eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. CATENA 187, 104399 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ferré, C., Caccianiga, M., Zanzottera, M. & Comolli, R. Soil–plant interactions in a pasture of the Italian Alps. J. Plant Interact. 15, 39–49 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-M. et al. Comparison of boosted regression tree and random forest models for mapping topsoil organic carbon concentration in an alpine ecosystem. Ecol. Indic. 60, 870–878 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ballabio, C., Fava, F. & Rosenmund, A. A plant ecology approach to digital soil mapping, improving the prediction of soil organic carbon content in alpine grasslands. Geoderma 187–188, 102–116 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Baize, D. Naissance et évolution des sols : La pédogenèse expliquée simplement. 1–160 (2021).

- Dorji, T., Odeh, I. O. A., Field, D. J. & Baillie, I. C. Digital soil mapping of soil organic carbon stocks under different land use and land cover types in montane ecosystems, Eastern Himalayas. For. Ecol. Manag. 318, 91–102 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. et al. Effects of land use and land cover change on soil organic carbon storage in the Hexi regions, Northwest China. J. Environ. Manage. 312, 114911 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Vaysse, K. & Lagacherie, P. Using quantile regression forest to estimate uncertainty of digital soil mapping products. Geoderma 291, 55–64 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Heuvelink, G. Uncertainty quantification of GlobalSoilMap products. Glob. Basis Glob. Spat. Soil Inf. Syst. - Proc. 1st Glob. Conf. 335–340 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Peralta, G., Di Paolo, L. & Luotto, I. Global Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Potential Map – GSOCseq v.1.1. (FAO, 2022). [CrossRef]

- Nations, Y., Olmedo, G. F. & Reiter, S. Soil Organic Carbon Mapping Cookbook 2nd Edition. (2018).

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. (2022).

- Bc, H. & Rg, C. Climate downscaling: techniques and application. Clim. Res. 07, 85–95 (1996).

- Belloni, S. & Pelfini, M. Il gradiente termico in Lombardia, Dipartimento di scienze terra del università di Milano. Acqua-Aria 4, 441–447 (1987).

- DUSAF 7.0 - Uso e copertura del suolo 2023 - Geoportale della Lombardia. https://www.geoportale.regione.lombardia.it/news/-/asset_publisher/80SRILUddraK/content/dusaf-7.0-uso-e-copertura-del-suolo-2023.

- Friedman, J. H. Estimating Functions of Mixed Ordinal and Categorical Variables Using Adaptive Splines. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA590939 (1991).

- Rentschler, T. et al. Comparison of catchment scale 3D and 2.5D modelling of soil organic carbon stocks in Jiangxi Province, PR China. PLOS ONE 14, e0220881 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-J., Cheng, H., Yang, L.-C. & Zhao, Y.-G. Soil organic carbon mapping in cultivated land using model ensemble methods. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 68, 1711–1725 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 67, 301–320 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Sirsat, M. S., Cernadas, E., Fernández-Delgado, M. & Barro, S. Automatic prediction of village-wise soil fertility for several nutrients in India using a wide range of regression methods. Comput. Electron. Agric. 154, 120–133 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Schmidt, M. G., Heung, B., Bulmer, C. E. & Knudby, A. Using an ensemble learning approach in digital soil mapping of soil pH for the Thompson-Okanagan region of British Columbia. Can. J. Soil Sci. 102, 579–596 (2022).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

- Wadoux, A. M. J.-C., Minasny, B. & McBratney, A. B. Machine learning for digital soil mapping: Applications, challenges and suggested solutions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 210, 103359 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Khaledian, Y. & Miller, B. A. Selecting appropriate machine learning methods for digital soil mapping. Appl. Math. Model. 81, 401–418 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Were, K., Bui, D. T., Dick, Ø. B. & Singh, B. R. A comparative assessment of support vector regression, artificial neural networks, and random forests for predicting and mapping soil organic carbon stocks across an Afromontane landscape. Ecol. Indic. 52, 394–403 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

- Piikki, K., Wetterlind, J., Söderström, M. & Stenberg, B. Perspectives on validation in digital soil mapping of continuous attributes—A review. Soil Use Manag. 37, 7–21 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tajik, S., Ayoubi, S. & Zeraatpisheh, M. Digital mapping of soil organic carbon using ensemble learning model in Mollisols of Hyrcanian forests, northern Iran. Geoderma Reg. 20, e00256 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ließ, M., Schmidt, J. & Glaser, B. Improving the Spatial Prediction of Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in a Complex Tropical Mountain Landscape by Methodological Specifications in Machine Learning Approaches. PLOS ONE 11, e0153673 (2016).

- Zhou, T. et al. High-resolution digital mapping of soil organic carbon and soil total nitrogen using DEM derivatives, Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data based on machine learning algorithms. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138244 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. et al. A novel intelligence approach based active and ensemble learning for agricultural soil organic carbon prediction using multispectral and SAR data fusion. Sci. Total Environ. 804, 150187 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zeraatpisheh, M., Ayoubi, S., Mirbagheri, Z., Mosaddeghi, M. R. & Xu, M. Spatial prediction of soil aggregate stability and soil organic carbon in aggregate fractions using machine learning algorithms and environmental variables. Geoderma Reg. 27, e00440 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yigini, Y. & Panagos, P. Assessment of soil organic carbon stocks under future climate and land cover changes in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 557–558, 838–850 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ma, M. & Chang, R. Temperature drive the altitudinal change in soil carbon and nitrogen of montane forests: Implication for global warming. CATENA 182, 104126 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Odebiri, O. et al. Estimating soil organic carbon stocks under commercial forestry using topo-climate variables in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South Afr. J. Sci. 116, 1–8 (2020).

- Parton, W. j. et al. Impact of climate change on grassland production and soil carbon worldwide. Glob. Change Biol. 1, 13–22 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Puche, N. J. B., Kirschbaum, M. U. F., Viovy, N. & Chabbi, A. Potential impacts of climate change on the productivity and soil carbon stocks of managed grasslands. PLOS ONE 18, e0283370 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. et al. A high-resolution map of soil pH in China made by hybrid modelling of sparse soil data and environmental covariates and its implications for pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 273–283 (2019). [CrossRef]

| Covariates Names | Abbreviations | Main statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Mean | Median | Max | SD | ||

| Elevation (m) | Elv | 197 | 1558.57 | 1664.21 | 3262 | 723.48 |

| Slope (°) | Slp | 0 | 31.75 | 32.93 | 80.08 | 15.40 |

| Northness index | N_ind | -0.99 | -0.14 | -0.31 | 1 | 0.74 |

| Eastness index | E_ind | -0.99 | -0.05 | -0.07 | 0.99 | 0.67 |

| Profile Curvature | Pr_cur | -0.277 | -0.000118 | -0.00003 | 0.208 | 0.007 |

| Plan Curvature | Pl_cur | -14.224 | 0.000095 | 0.00062 | 8.503 | 0.045 |

| Min Curvature | Min_cur | -0.666 | -0.010872 | -0.00515 | 0.242 | 0.023 |

| Log Curvature | Log_cur | -0.919 | -0.000248 | -0.00004 | 0.680102 | 0.039003 |

| General Curvature | Gen_cur | -1.426 | 0.000063 | 0 | 1.167034 | 0.07111 |

| Max Curvature | Max_cur | -0.309 | 0.010903 | 0.00539 | 0.483 | 0.022 |

| Transversal Curvature | Tra_cur | -0.773112 | 0.000311 | 0.00007 | 0.829 | 0.04 |

| Total Curvature | Tot_cur | 0 | 0.000986 | 0.00015 | 0.319 | 0.003 |

| Tang Curvature | Tan_cur | -0.269201 | 0.000099 | 0.000071 | 0.298031 | 0.014142 |

| Terrain Ruggedness Index | TRI | 0.0013 | 11.09 | 10.27 | 94.32 | 7.119 |

| Terrain Position Index | TPI | -81.178 | 0.0055 | -0.0012 | 65.2903 | 4.351 |

| Flow Accumulation | Fl_Acc | 0 | 106.35 | 3 | 61576 | 1109.12 |

| Vector Ruggedness Measure | VRM | 0 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.06 |

| Terrain Wetness Index | TWI | 2.808 | 7.944 | 7.324 | 19.311 | 2.715 |

| Mean annual Temperature (°C) | T | 1.62 | 4.97 | 3.12 | 14.61 | 3.74 |

| Mean annual Precipitations (mm) | P | 514.8 | 1278.56 | 1268.6 | 1531.1 | 132.39 |

| Soil Properties | Statistical Metrics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 1st Qu | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu | Max | SD | |

| SOC stock 10(kg.m-2) | 0.02 | 2.88 | 4.00 | 4.29 | 5.55 | 9.31 | 2.10 |

| SOC stock 30(kg.m-2) | 0.03 | 5.13 | 7.27 | 8.72 | 10.93 | 29.90 | 5.51 |

| Model Performance | Machine learning models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARS | Enet | RF | SVR | ||

| SOC stock 10(kg m-2) | RMSE | 1.63 | 1.61 | 1.35 | 1.50 |

| R2 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.69 | 0.50 | |

| MAE | 1.25 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 0.98 | |

| SOC stock 30(kg m-2) | RMSE | 3.47 | 3.97 | 3.36 | 3.46 |

| R2 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.65 | 0.62 | |

| MAE | 2.67 | 3.01 | 2.48 | 2.25 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).