1. Introduction

According to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Brazil is the most biodiverse country in the world [

1] and knowledge of this biodiversity is fundamental for conservation strategies. Brazilian researchers daily describe new species and report discoveries about species distribution in the Brazilian biomes. However, a large proportion of microbial species in Brazil remain undescribed.

Despite the economic importance of exploring biodiversity, Brazil has invested very little to promote this type of study. The situation is even more urgent considering climate change, fires, and environmental disasters to which Brazilian biomes have been subjected in recent years. In addition, according to Bustamante and collaborators [

2], the contribution of changes in land use and agriculture to climate change and biodiversity decline places new demands on sustainability challenges in agriculture and soil biodiversity conservation. All these studies and applications depend on biodiversity conservation, which must be carried out both in situ and

ex situ.

In fact, culture collections are essential biorepositories for biodiversity conservation and service providers for the health, environmental, agribusiness, and industry sectors. This is so true that the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) itself drove a paradigm shift on the world stage regarding the role of biological collections. Therefore, biological collections are essential parts of the research infrastructure of all countries. In Brazil, this importance has been recognized by the current legislation, Law 13,123/2015, for access to genetic resources and associated traditional resources knowledge and benefit sharing. Therefore, investments in microbial collections are strategic for the sustainable use of biodiversity and the defence of national sovereignty. Considering the low volume of financial resources available, it is mandatory for the Brazilian government to apply these resources very well, prioritizing demands rationally. However, such rational and sustainable use of financial resources depends on knowledge of each Brazilian collection’s reality, problems, and demands. The truth is that so far, we have more questions than answers. For example, how many and what are the Brazilian microbial collections? Where are they located? What type of institution are they in? Are all biomes and taxonomic groups represented in our collections? Which collections have deposits of type strains and how are they preserved? What are the collections’ strengths, weaknesses, and needs so that diversity is safely preserved?

Therefore, to answer these questions and to know the actual situation of the biological collections as a whole in Brazil, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Brazil asked for the Brazilian Societies of Botany, Microbiology, Virology and Zoology to carried out a comprehensive survey on Brazilian biological collections. This survey comprised several stages, such as: (1) preparation and validation of a form containing several questions related to different aspects of organization and management of biological collections; (2) Prospection of curators and professionals associated with public and private institutions potentially maintaining collections to send the form; (3) Data compilation and analysis. In the current study, we specifically present the results obtained for the microbiological collections, providing an overview of the current status for these collections and discussing essential strategies for conserving Brazilian microbial biodiversity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey structure

A comprehensive survey was built to properly understand the status and organization of the Brazilian microbiological collections. The survey comprised 92 different questions, organized into nine sections about different aspects related to the organization and management of collections: (1) Identification, (2) Characterization, (3) Infrastructure, (4) Personnel, (5) Access, (6) Digitalization, (7) Quality management, (8) Collection management, and (9) Priorities.

For all nine sections, most of the questions provided previously defined closed alternatives for the answers, with a few exceptions allowing for open answers. For questions related to ordinal variables, a unipolar scale (from “minimum” to “maximum”, “worst” to “best”) with an odd number of alternatives was employed.

The survey was initially reviewed and validated by 10 curators from representative microbiological collections from different kinds of institutions and Brazilian regions. These curators evaluated the feasibility and completeness of the survey, suggesting corrections and changes to be made to the final version.

2.2. Assessing the Microbiological Collections

A preliminary list with already known and established microbiological collections was built based on data collected from the main Brazilian public databases, such as the Brazilian node of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, SiBBr (

Sistema de Informação sobre a Biodiversidade Brasileira,

https://collectory.sibbr.gov.br/collectory/), and SpeciesLink (

https://specieslink.net/search/). Additional collections were also contacted based on data provided by the Brazilian Society of Microbiology, and Brazilian Society of Virology, as well as lists compiled by national, regional and international federations and networks such as the World Federation for Culture Collections (WFCC),

Federación Latinoamercina de Colecciones de Cultivos Microbianos (FELACC),

Napi Taxonline - Rede Paranaense de Coleções Biológicas. Moreover, to reach potential unknown collections that were still absent from official databases and lists, the survey link was also sent to researchers from Brazilian public and private universities and research institutes, and advertised on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

2.3. Data Analysis

The answers received between April and June 2022 were manually processed and reviewed before further analyses. All answers for all 92 questions were individually assessed, searching for potential mistakes and inconsistencies. After revisions and corrections, the results were further analyzed and processed in Microsoft Excel, and final plots were produced in R [

3], using the tidyverse package.

3. Results

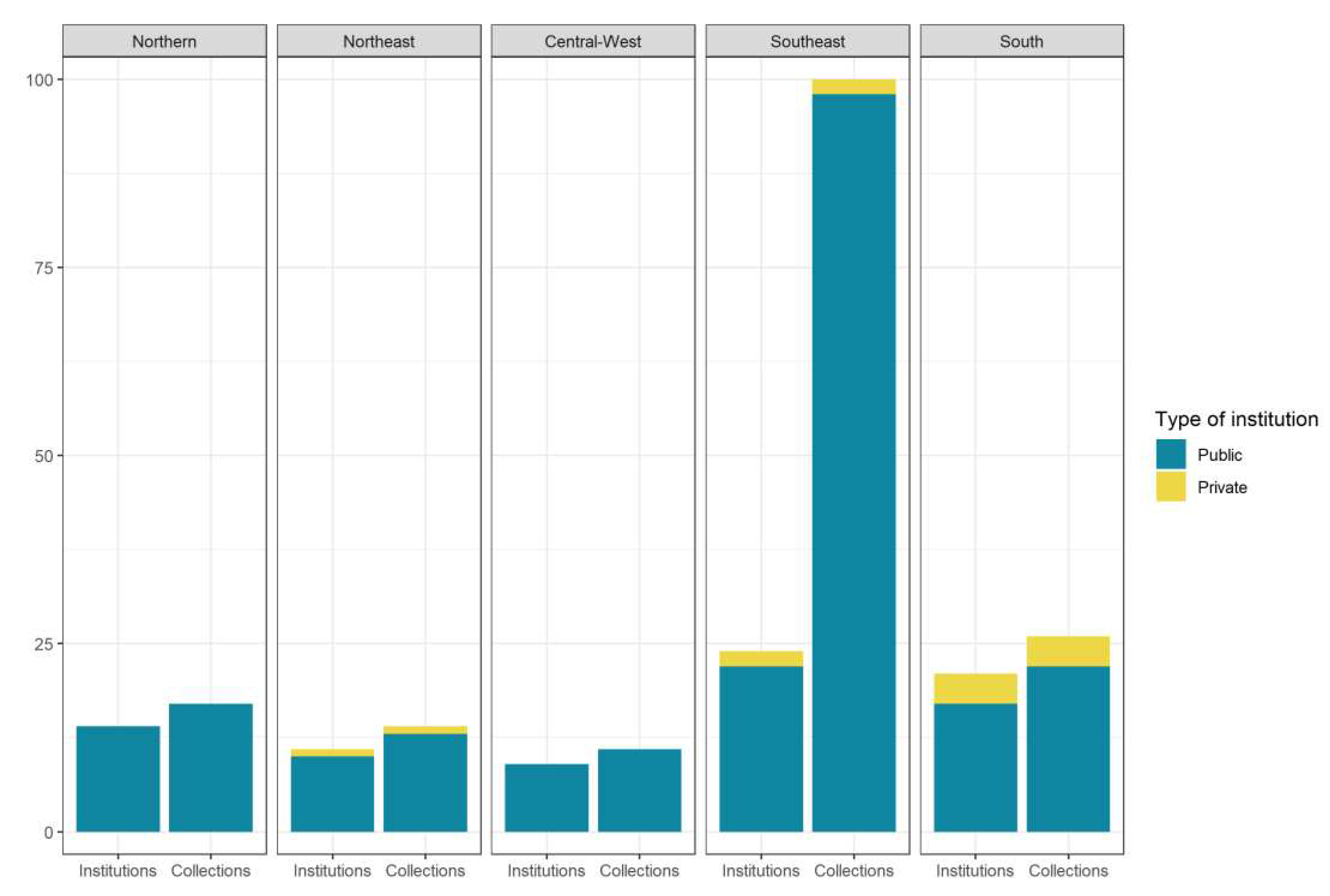

3.1. Public Institutions in Brazil Are Responsible for the Vast Majority of Microbial Collections

The survey was sent to public and private institutions in Brazil and was answered by 168 microbiological collections from 79 different institutions. Among these institutions, 73 (92.4%) comprise public research institutions and universities (

Figure 1).

There is apparent heterogeneity between Brazilian regions, with the Southeast region alone accounting for 59.5% of the Brazilian microbial collections (

Figure 1). If, on the one hand, this is the most populous region in Brazil (it concentrates 42.06% of the Brazilian population); on the other hand, it is home to only part of one of the six Brazilian biomes (Atlantic Forest).

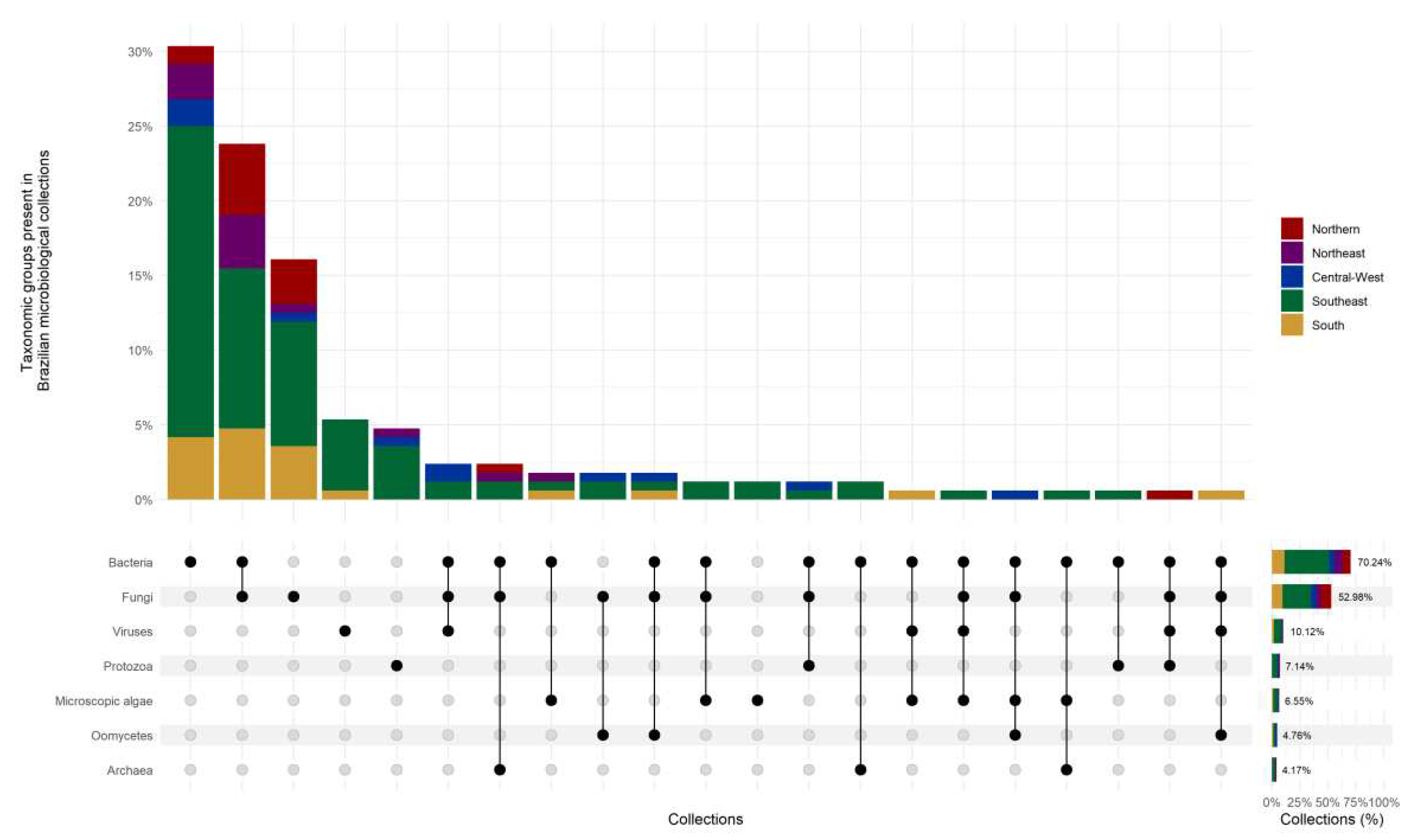

3.2. Most Collections in Brazil Have Bacteria and Fungi

The main taxonomic groups preserved in Brazilian culture collections are bacteria (present in 70.24% of the collections) and fungi (52.98%) from different Brazilian ecosystems and biomes, including ex situ preservation on several type strains (

Figure 2). Bacteria and fungi are usually the most abundant taxon in microbial culture collections worldwide [

4,

5]. As already expected, most Brazilian Collections have microorganisms obtained from different substrates in the Brazilian territory. Even though the survey did not assess the number of isolates pertaining to each taxonomic group in the microbial collections, as well as the quality and preservation status of these isolates, it is still reasonable to expect that bacteria and fungi are likely the microbial taxonomic groups mostly preserved in Brazil. These data illustrate the importance of culture collections in preserving Brazilian biodiversity.

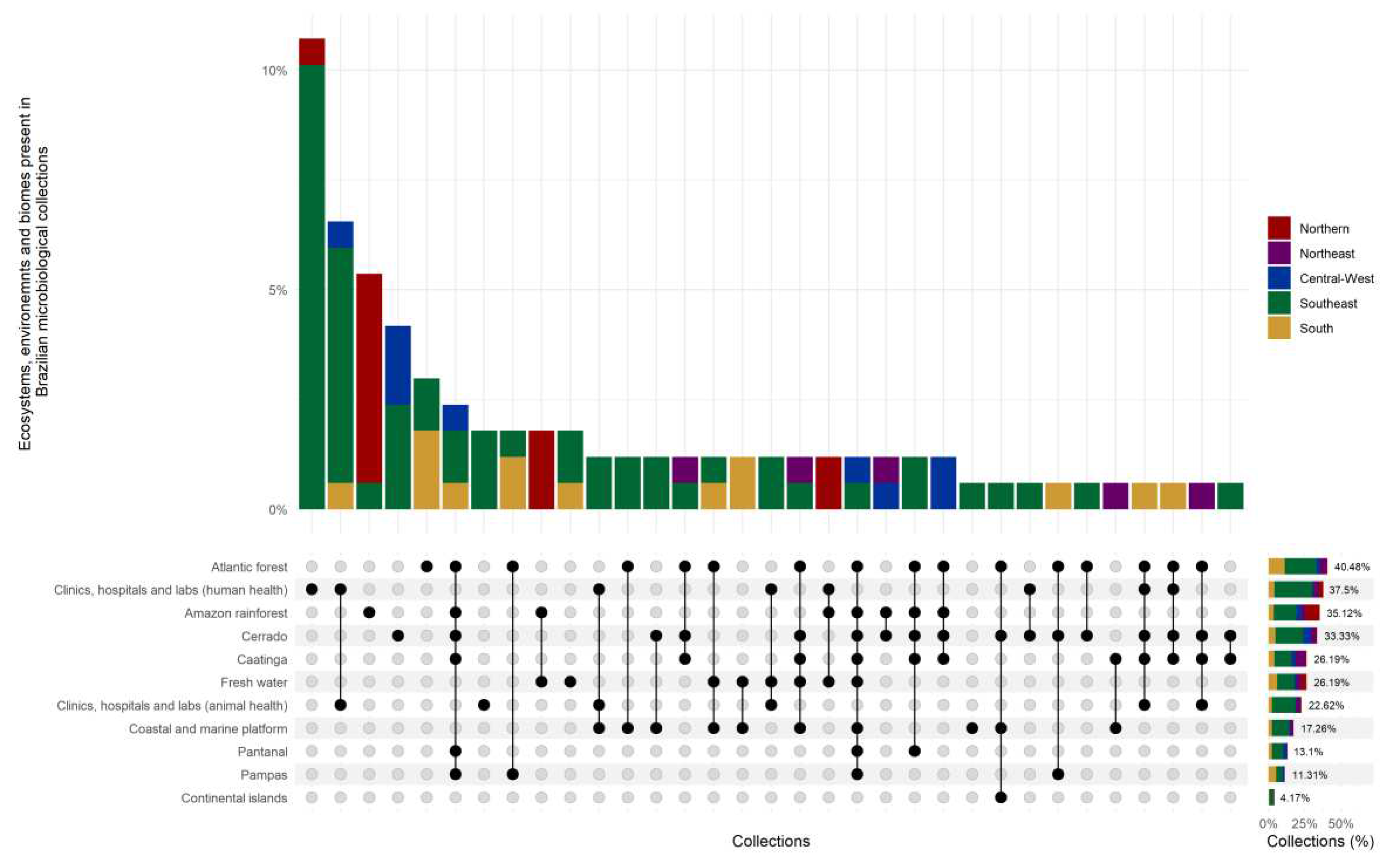

3.3. One of the Most Diverse Biomes in Brazil Is Poorly Conserved Ex Situ

There is an evident heterogeneity between the represented biomes in the Brazilian microbial collections (

Figure 3). Most of the collections have microbial isolates obtained from the Atlantic Forest (40.48%), Amazon (35.12%), Cerrado (Savannah) (33.33%), and Caatinga (26,19%), Pantanal and Pampas biomes are poorly represented within the various microbial collections around Brazil (present in only 13.11% and 11.31% of the collections, respectively). It is surprising since the Pantanal is one of the world’s most highly diverse biomes. Although plants and animals in Pantanal are extensively studied, there are few studies on microorganisms, which is reflected in the low representation of this biome among the microbiological collections.

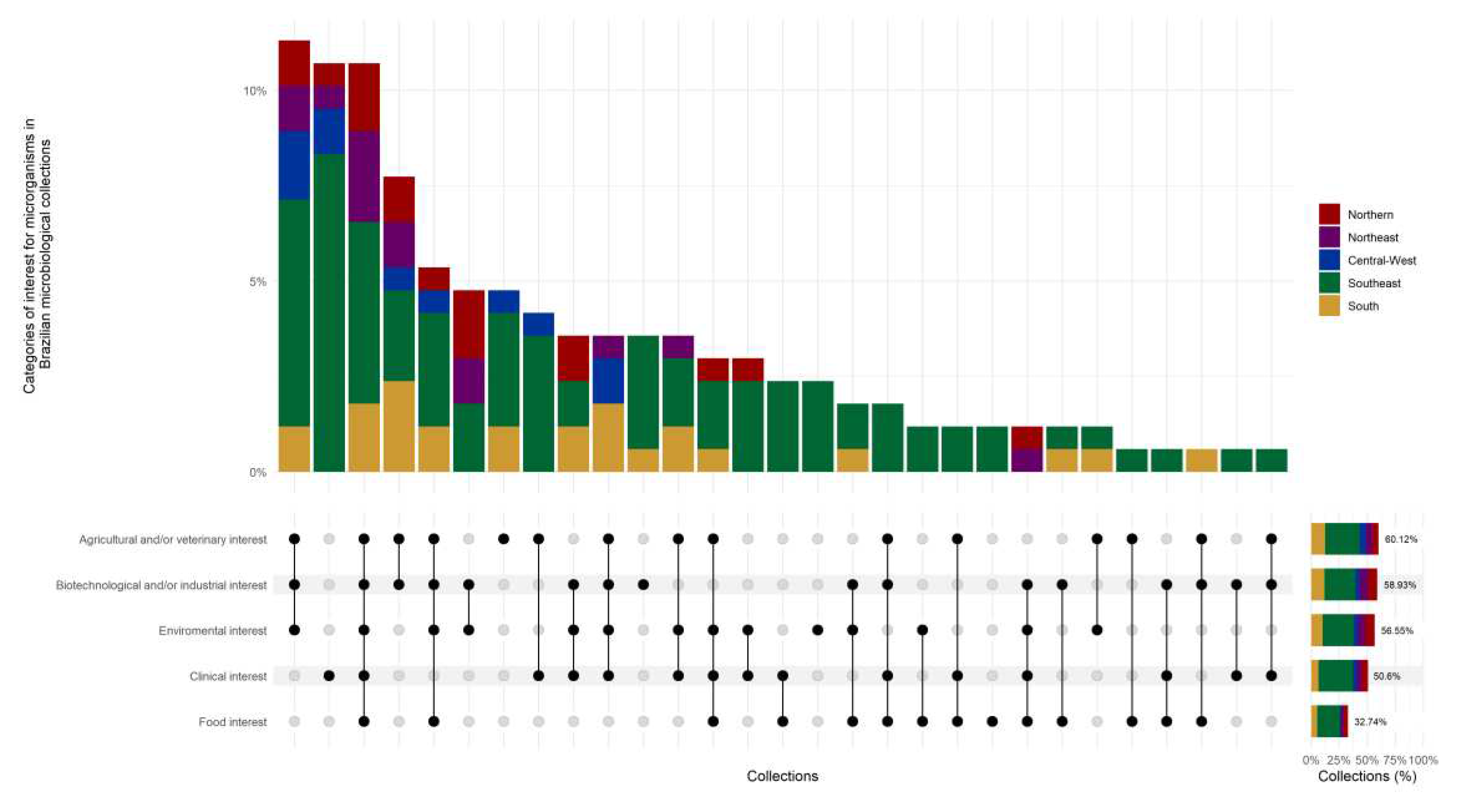

3.4. Brazilian Collections Are a Source of Microorganisms with Great Interest in Different Areas

A representative number of Brazilian collections harbor microorganisms with potential for application in several areas, being of interest in biotechnology, agriculture, and the pharmaceutical industry, in addition to the importance in clinical and veterinary medicine (

Figure 4). A smaller number of collections are dedicated to preserving microorganisms of food interest (32.74%), demonstrating that there are still gaps to be filled.

Furthermore, we observed that several collections preserve clinical microorganisms (human and animal pathogens) suggesting that these groups have great representativeness also (

Figure 4). The emergence and dissemination of multidrug-resistant pathogens, the introduction of new pathogens in Brazil (such as SARS-CoV-2, H5N1, H1N1, Monkeypox, Zika virus, Chikungunya virus), and the emergence of new zoonoses, highlight the importance of preserving these microorganisms for epidemiological studies and development of vaccines and new drugs.

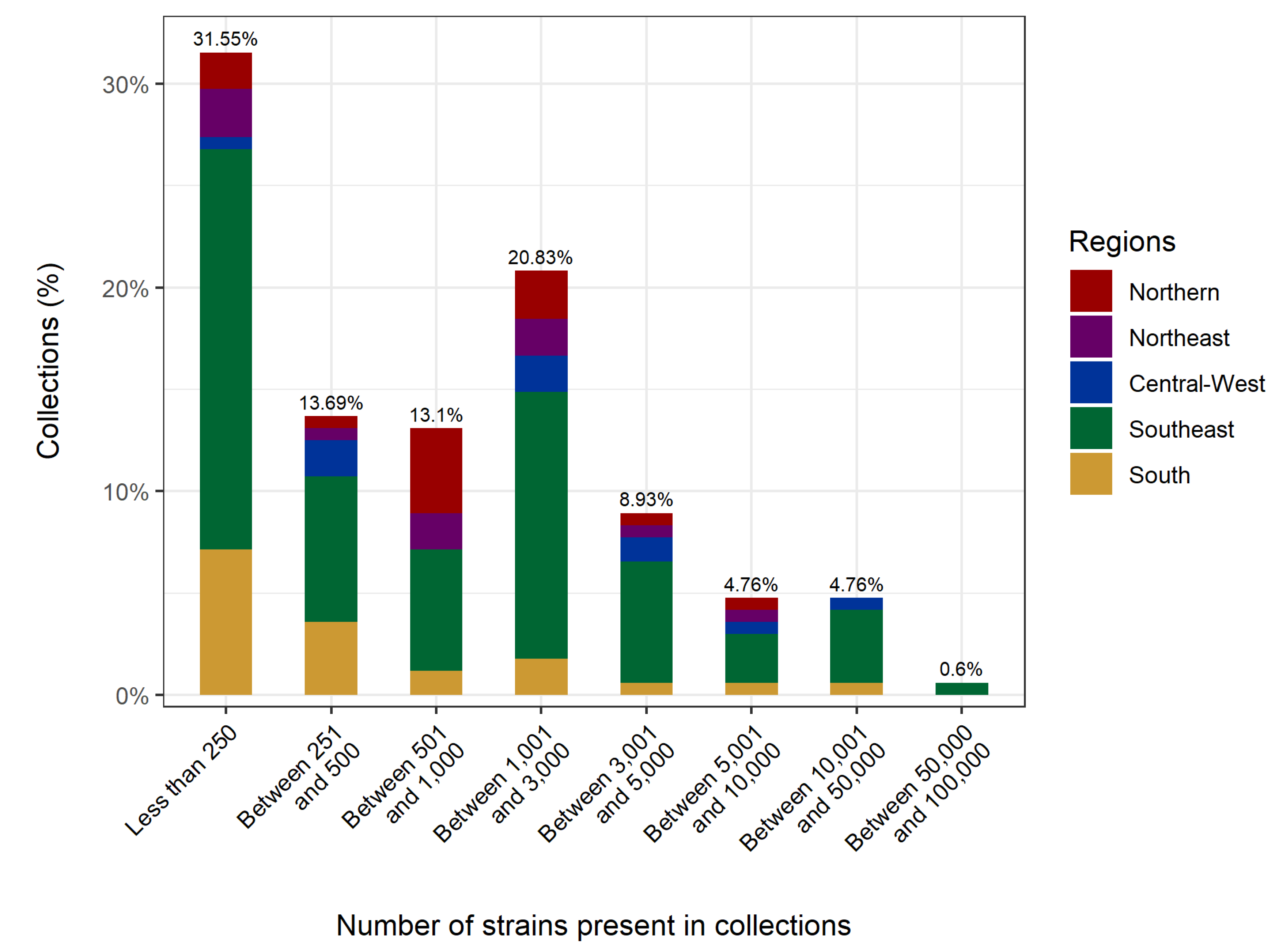

3.5. Size of Brazilian Microbiological Collections and Methods of Preservation Applied

According to our study, 58.34% of Brazilian microbial collections can be considered as small collections (up to 1000 isolates), 29.76% contain between 1000 and 5000 isolates, 9.5% are large collections (having between 5 and 50 thousand isolates), and one collection from the Southeast region (0.6%) contains more than 50,000 isolates (

Figure 5). This one is considered a very large microbial collection, larger than most collections in developed countries, according to Ryan and collaborators [

5].

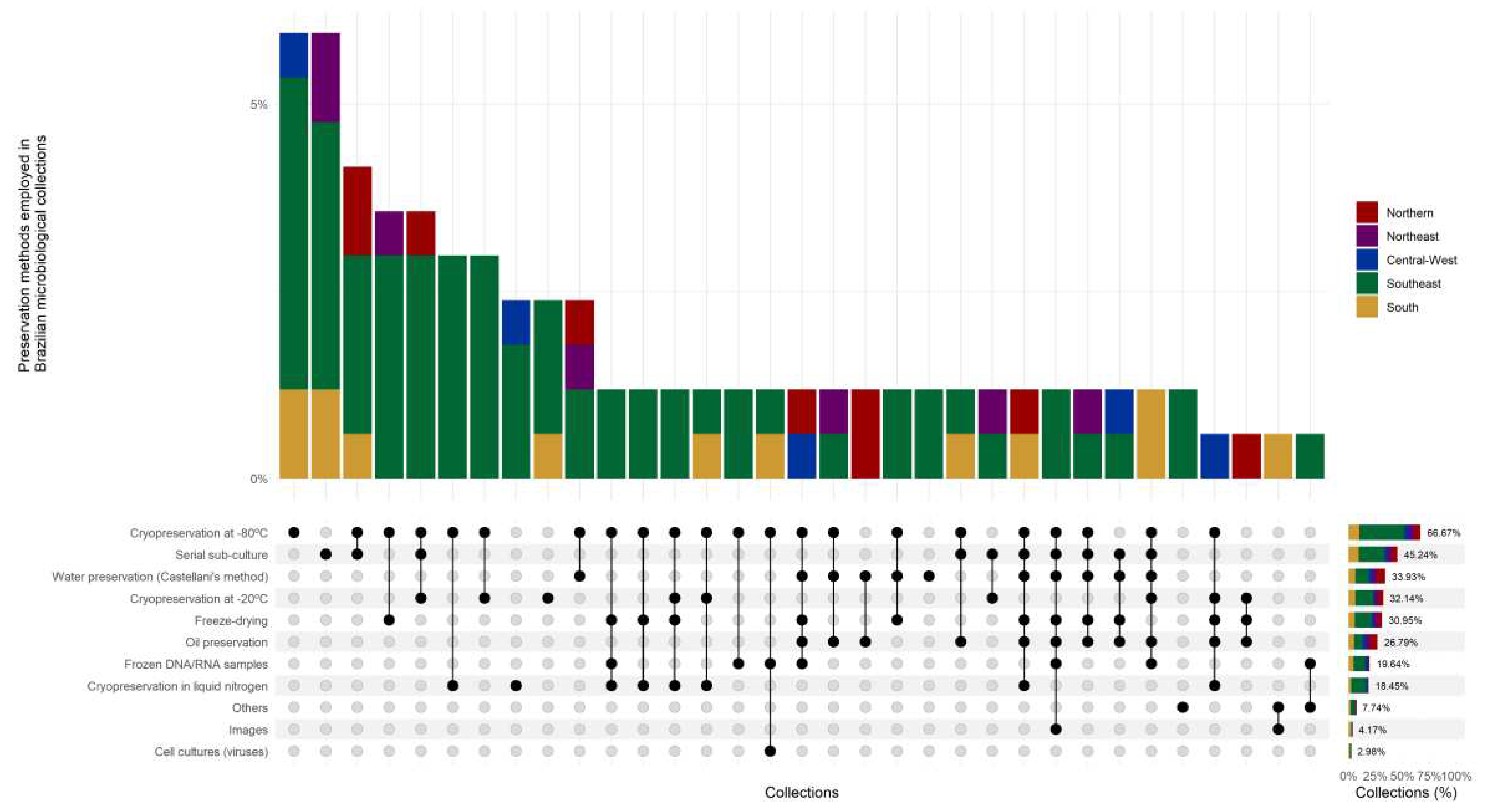

Regarding preservation, 66.67% of Brazilian microbiological collections employ cryopreservation at -80°C as one of the preservation methods (

Figure 6). However, several collections still preserve strains (including type strains) using classical methods, such as serial sub-culture (45.2%), and storage in oil (26.8%) or water (Castellani’s Method) (33.9%) [

6]. One of the reasons is probably the limitation of financial resources to acquire equipment for cryopreservation.

However, if, on the one hand, these basic methods are low cost, requiring only basic infrastructure, on the other hand, the main objective of preservation is to maintain purity and viability and avoid the selection of mutants [

7]. Therefore, the classical methods are not the best suited to meet these requirements, and there is a clear need to invest in long-term preservation methods such as freeze-drying and cryopreservation at ultrafrezeers and liquid nitrogen tanks [

5].

In the routine maintenance of microbial collections, the quality and constant availability of reagents and basic supplies are of great importance, especially in maintaining the microorganisms in at least two different conditions [

8]. However, there is a need for large financial investment for such maintenance, and unfortunately, such investment is limited for most Brazilian microbial collections, as will be shown below.

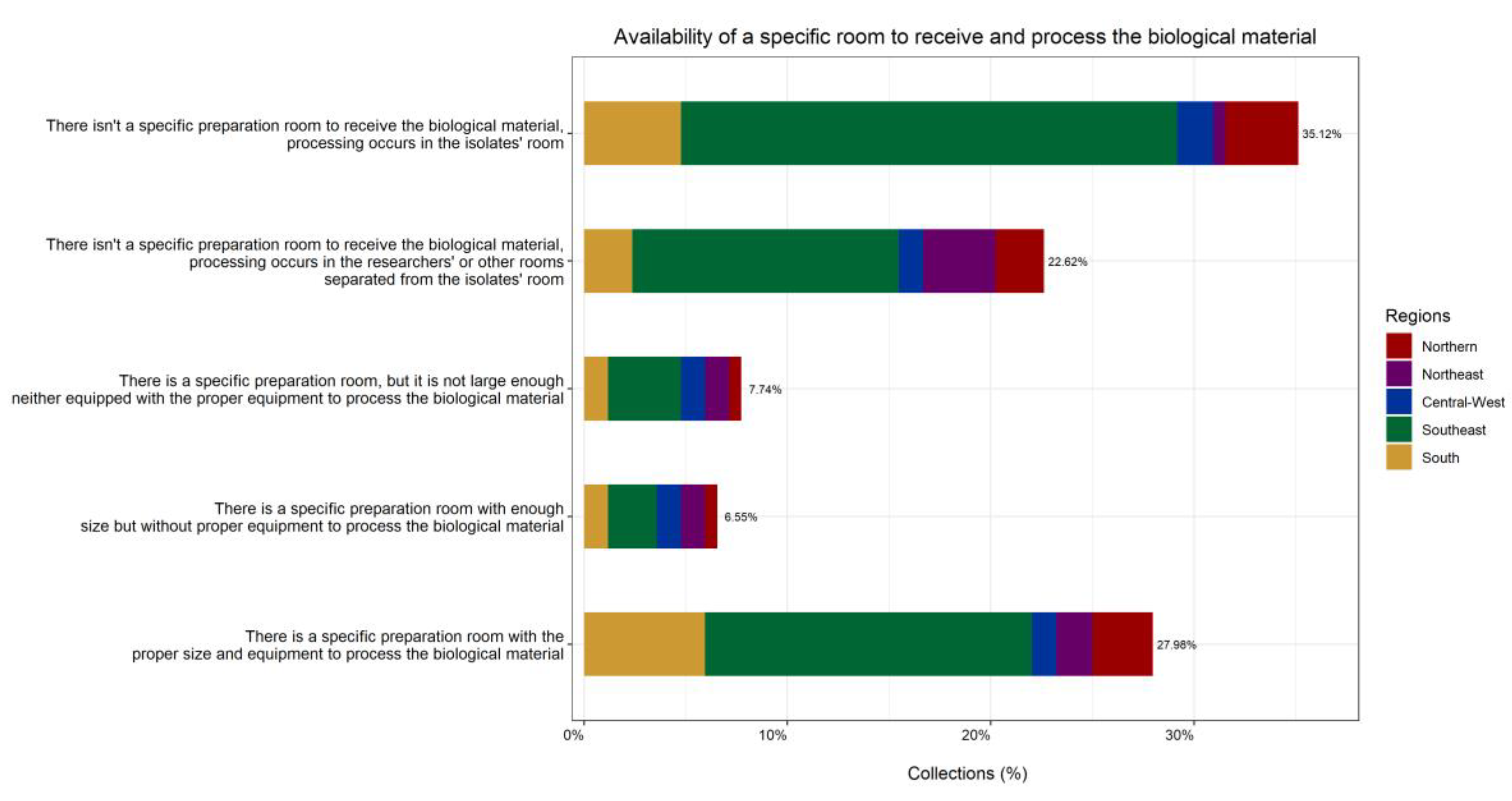

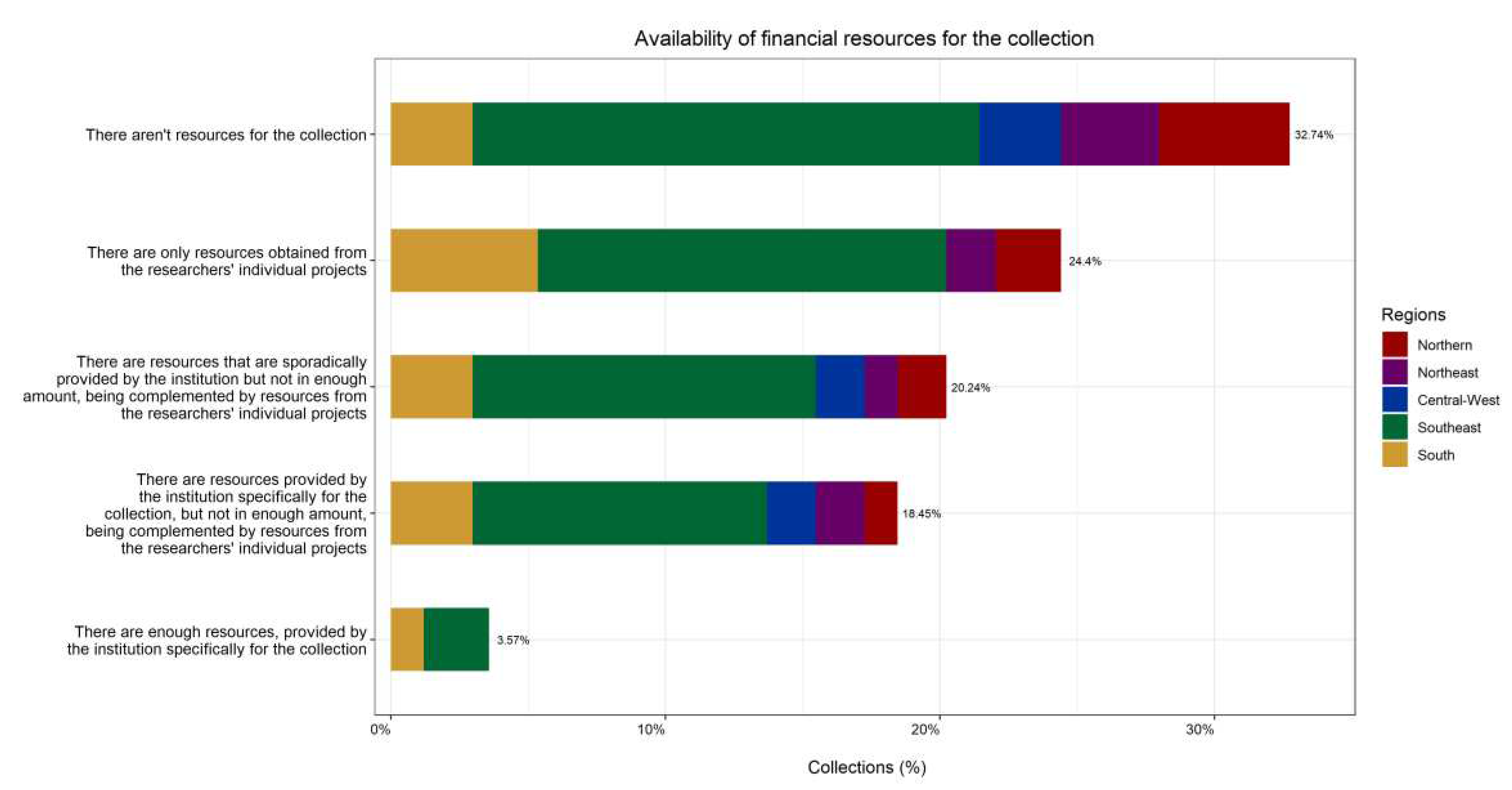

3.6. Despite Their Great Importance, Brazilian Microbial Collections Lack Infrastructure, Financial and Human Resources

Most microbiological collections in Brazil have serious problems with infrastructure, financial resources, and human resources. Regarding infrastructure, a considerable part of the collections (35.12%) is in a critical scenario, in which there is no preparation room, with reception and expedition of microorganisms taking place in the same room in which the microorganisms are preserved (

Figure 7).

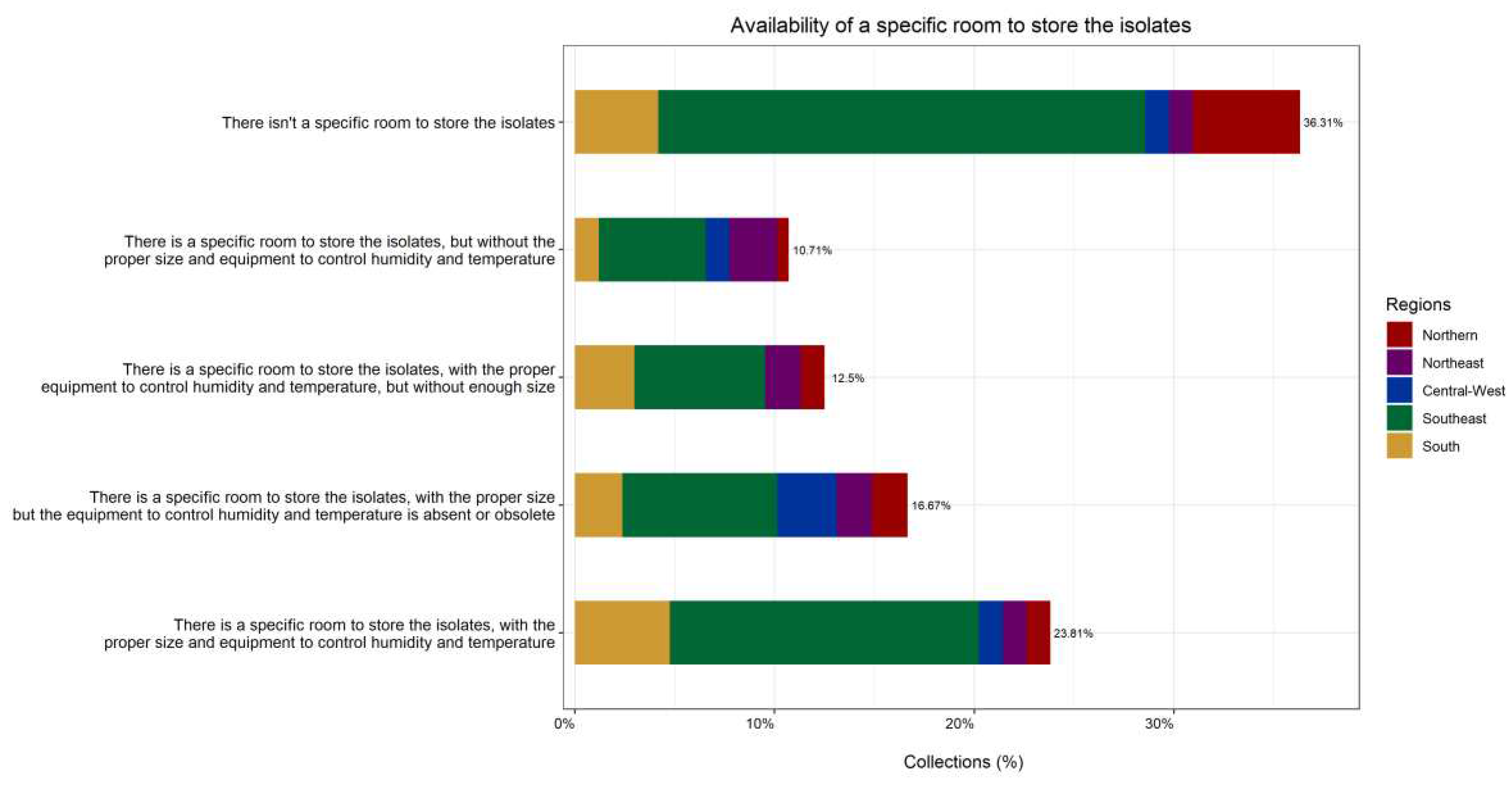

The lack of infrastructure is a critical issue for microbiological collections in Brazil, as 36.31% do not have a specific room to maintain the collection (

Figure 8). But the scenario is even more worrying in some regions of Brazil, such as the North (53%) and Southeast (41%). Furthermore, for 23.2% of the Brazilian microbiological collections, even though they have a specific room to maintain the collection, the room is not large enough (

Figure 8).

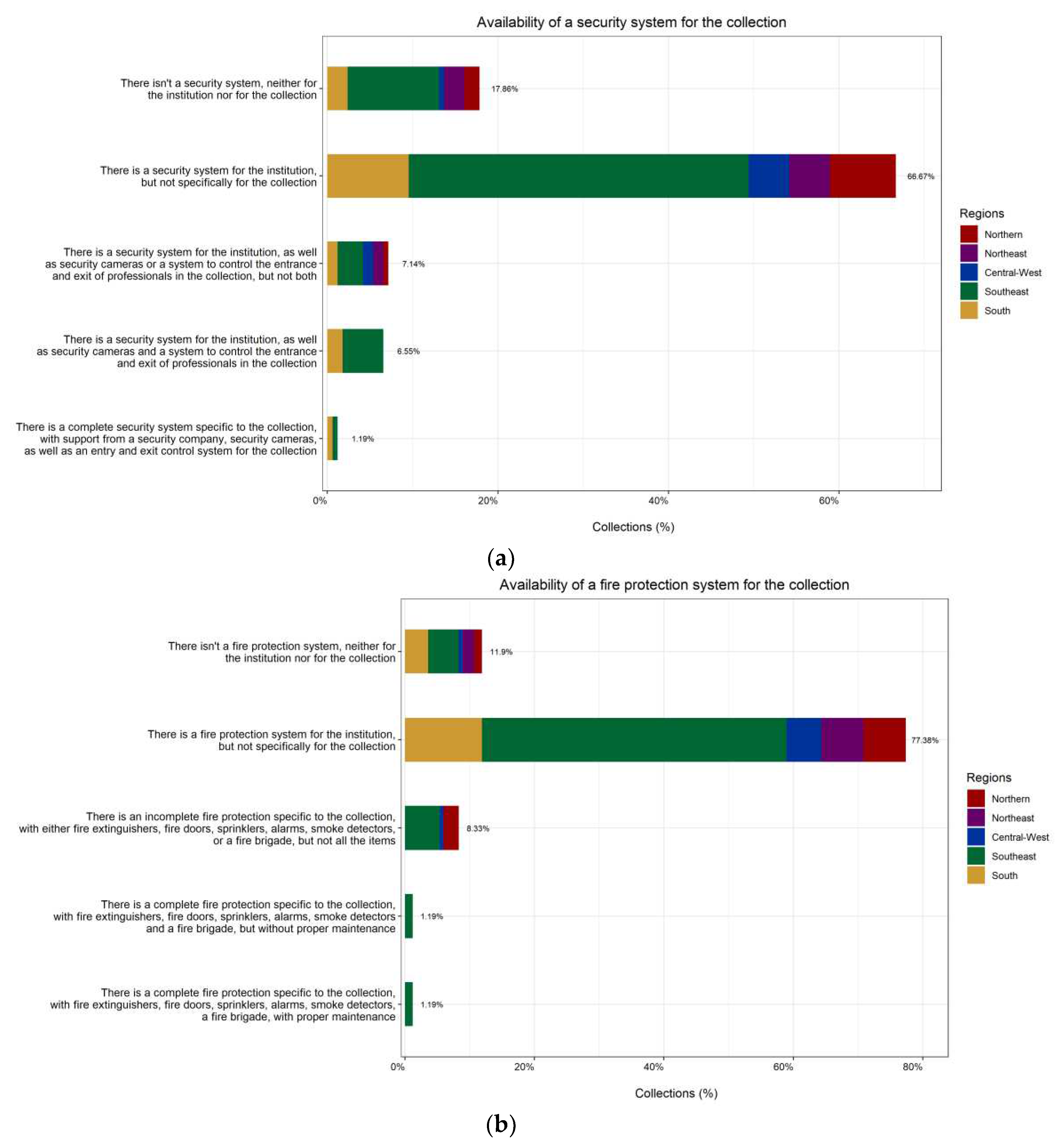

In addition, there is also a concern regarding the security of the collection due to biosecurity issues [

8]. Only 1.19% of the microbiological collections in Brazil have a complete security system specific to the collection including security cameras and an entry and exit control system (

Figure 9a). This figure shows also that 17.86% of the collections have no security system, neither for the institution nor for the collection. In addition, very few microbiological collections (1.19%) have a complete and exclusive and adequately maintained fire protection system, including extinguishers, fire doors, sprinklers, alarms, smoke detectors, and fire brigade (

Figure 9b). Logically, in most institutions that house microbiological collections, there is a fire protection system in general (77.38%), but not one exclusive to the collection. The positive point is that most microbial collections have adequate electrical installations (72.02%), which minimizes the risk of fires and the risks of freezers and ultrafreezers not working, resulting in the loss of microorganisms viability (

Figure 9c).

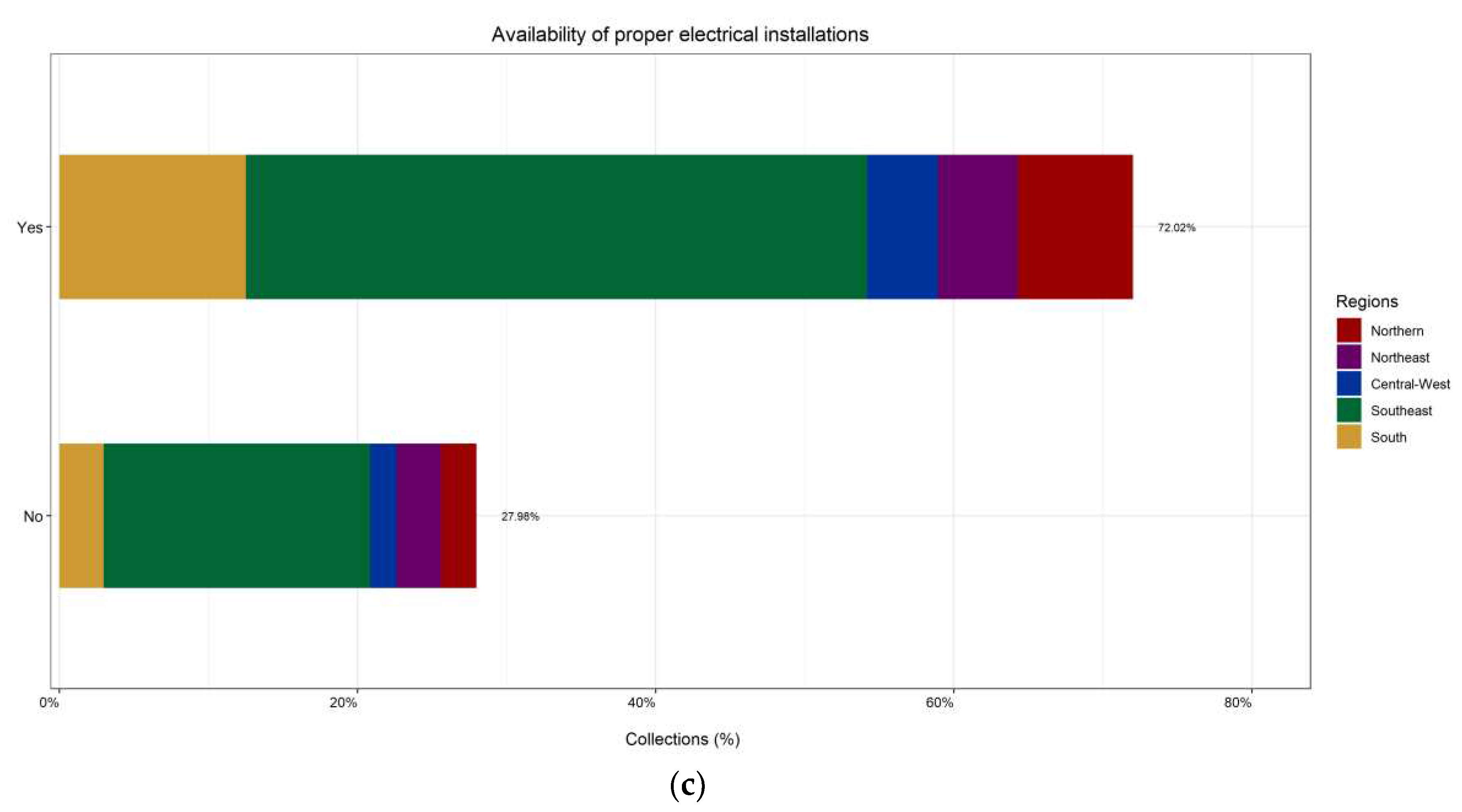

As previously mentioned, unfortunately, the lack of funding is another fragile aspect of the current situation of microbial collections in Brazil, since most of them do not have sufficient financial resources to maintain their collections (

Figure 10). This data reveals the risk to which collections are subjected since the lack of reagents and basic supplies and cryopreservation equipment can compromise the quality, purity, and viability of the preserved material.

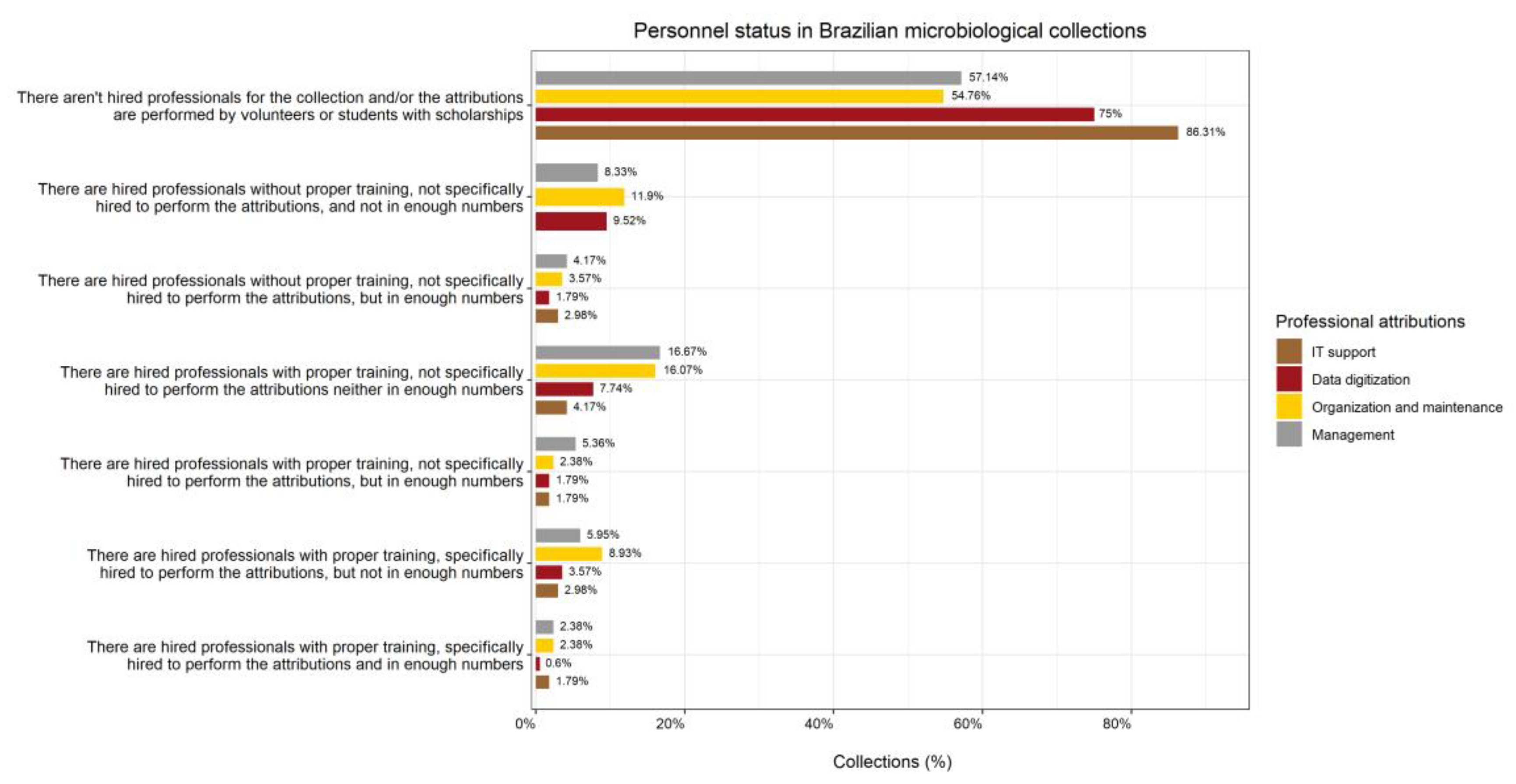

Another fragility increasing the problems, is the low number of professionals working in Brazilian microbiological collections (

Figure 11). We analyzed four categories of professional attributions, and 54.76% of collections do not have professionals hired for organization and maintenance of the collection. In some cases, these attributions are performed by volunteers or students with scholarships. These percentages are even higher for collection management (57.14%), data digitization (75%) or Information Technology (IT) support (86.31%).

3.7. Brazilian Microbiological Collections and Recognition by the Institution

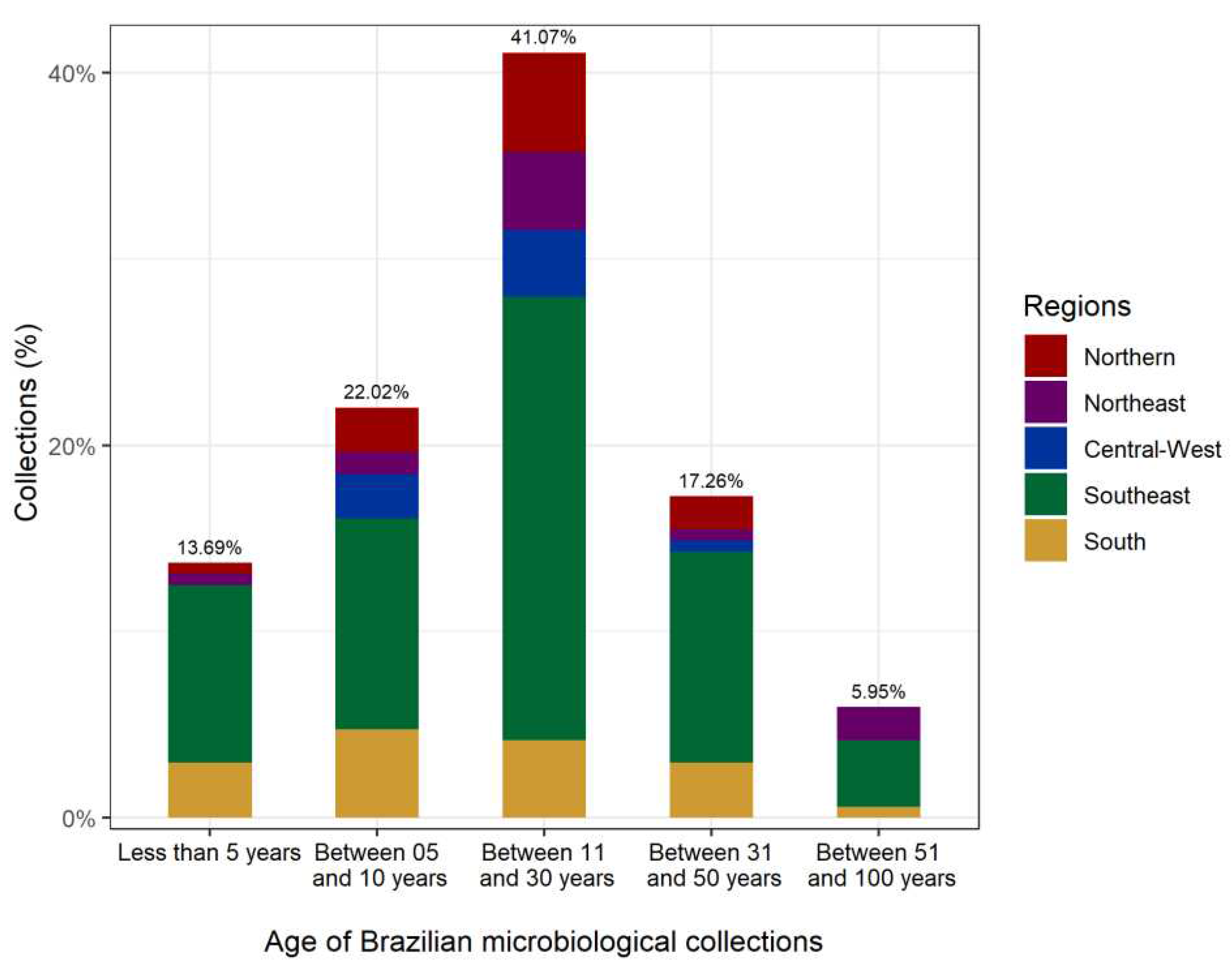

A considerable part of Brazilian microbiological collections (58.33%) is between 11 and 50 years old since their foundation (

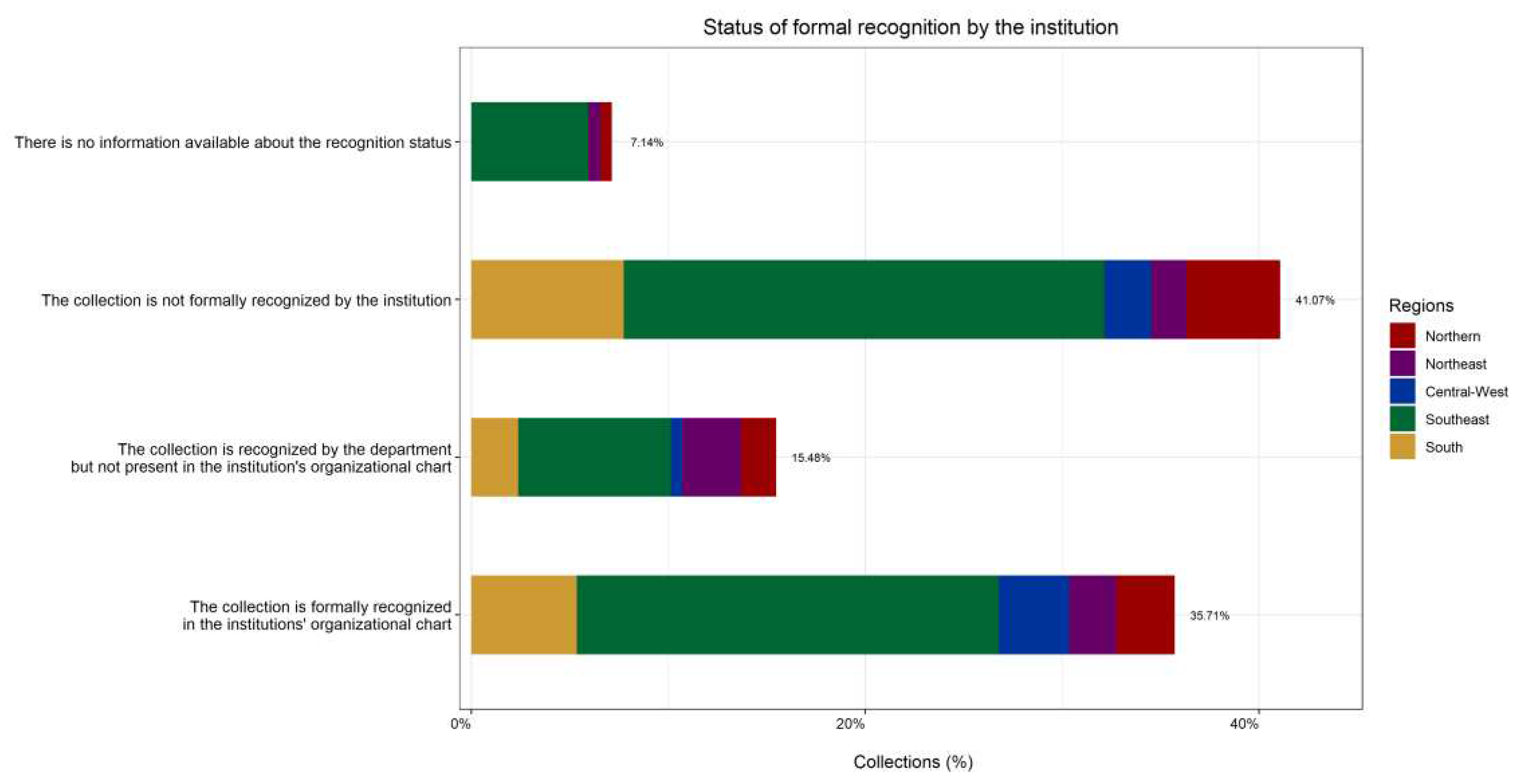

Figure 12), having survived for an extended period and safeguarding material of great importance, as has been discussed so far. However, only 51.5% of collections have formal recognition from their institutions, with an internal regulation and a specific policy for biological collections (

Figure 13). Among these, approximately 56.9% are concentrated in the Southeast region. Therefore, the scenario in other regions of the country is even more critical.

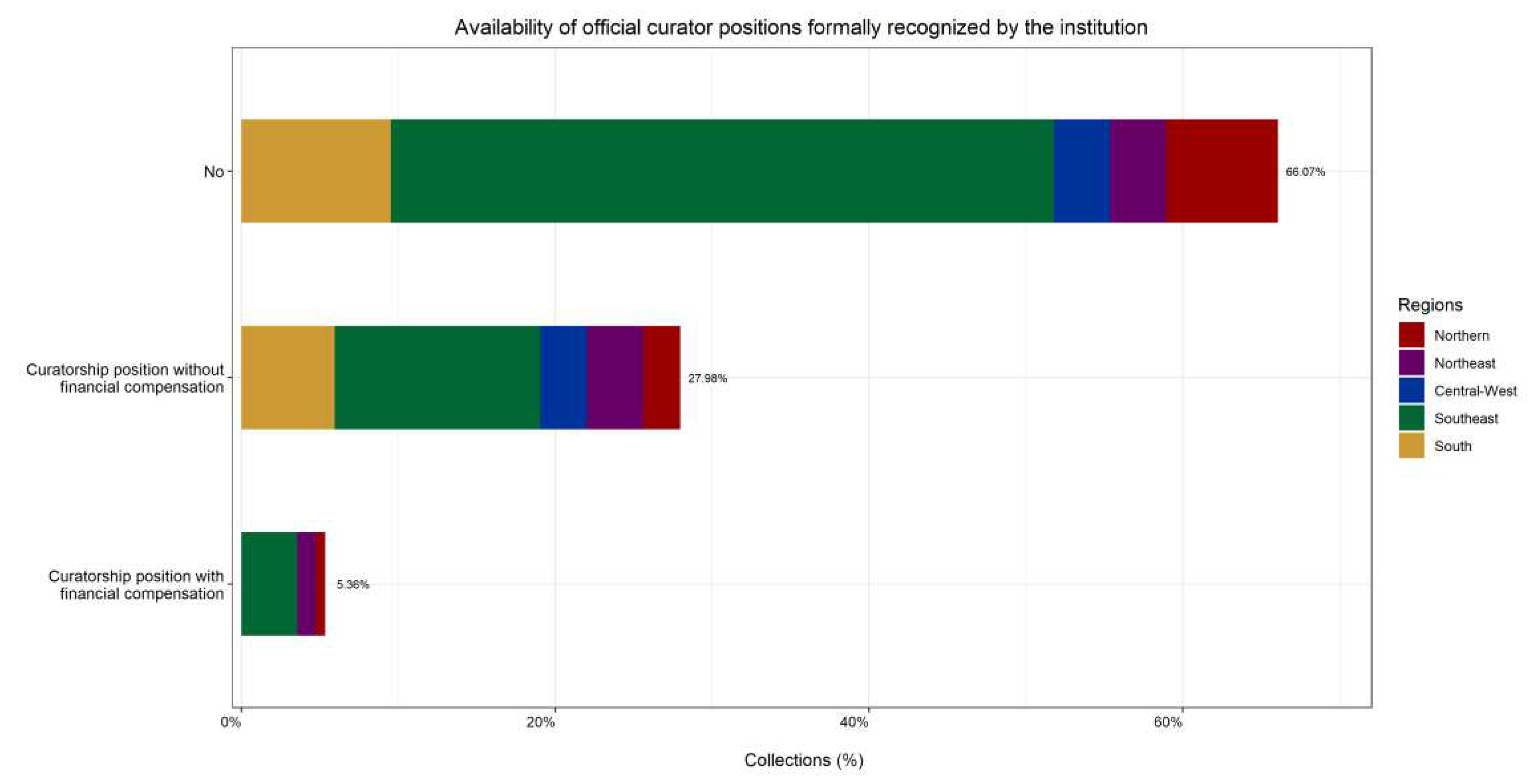

Another essential data to be analyzed is the official position of curator in the institutions’ organizational chart. 66.07% of the microbiological collections in this survey do not have a curator position in their institutions (

Figure 14). In the Southeast region, where the most significant number of collections are found, this percentage still increases to 71.7%. These numbers are worrying, as they demonstrate that most collections rely on the commitment and dedication of researchers who act as curators voluntarily. Without the institution’s formalization of curatorial activity, the collection risks disappearing when the researcher retires. The role of the curator is essential and must be a minimum criterion in the management, organization, and institutionalization of biological collections [

9].

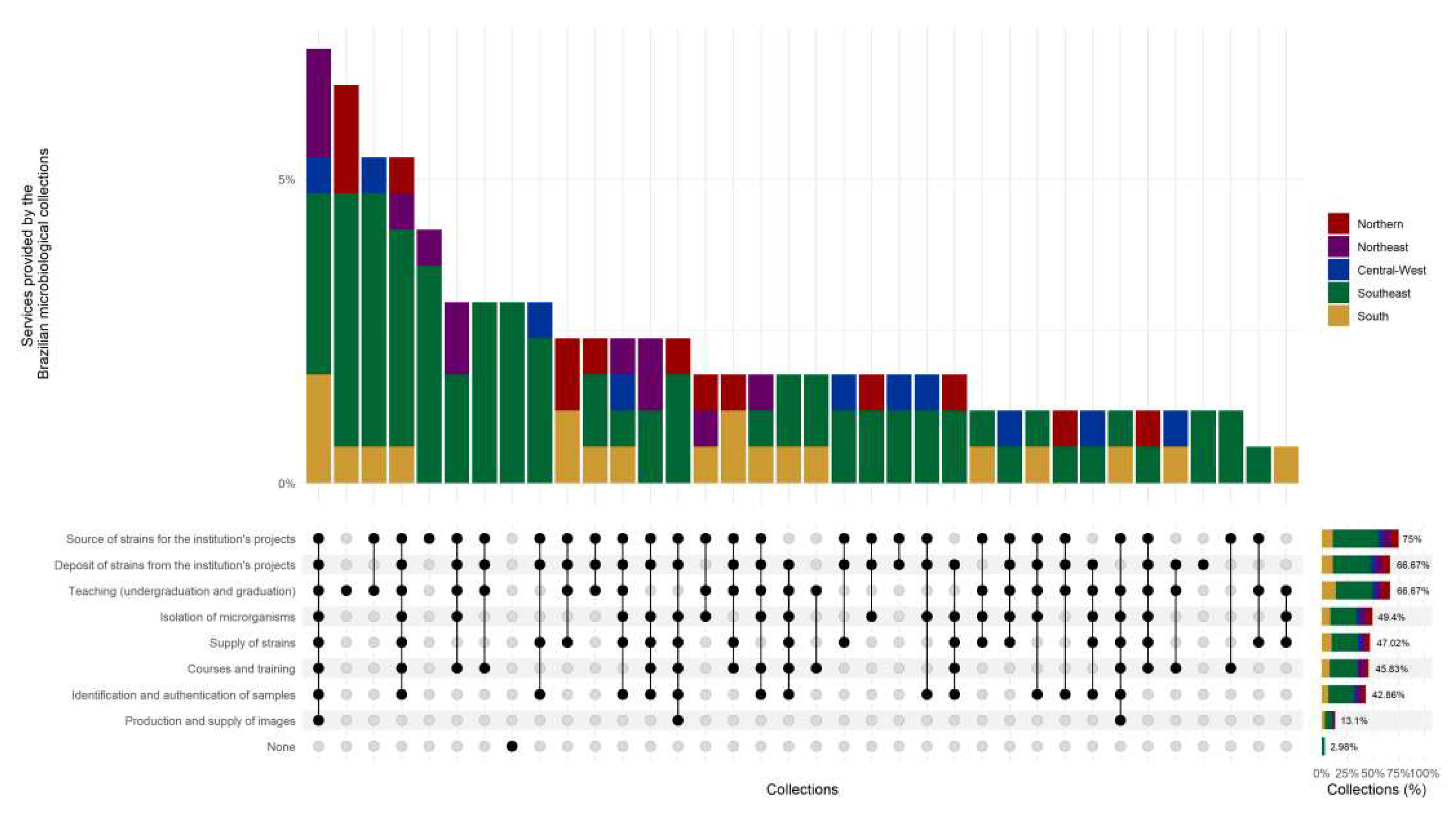

In addition to the valuable material preserved in collections, microbial collections provide essential services that support research, technological development, and innovation [

10]. Around 97% of the collections offer public and private institutions with specialized services such as deposit and supply of strains, taxonomic identification, consultancy, courses and training, and others, and a significant proportion of these collections provide more than one kind of service (

Figure 15). Although in practice, they provide services, they are not formally classified as service collections, which could change with institutional recognition.

4. Discussion

When referring to a microbial collection, we must keep in mind that they must meet the minimum criteria: 1) to conduct activities such as preservation, deposits, distribution, and taxonomic identification of microorganisms, besides scientific consultancy and training; 2) to have a curator; 3) to conduct registration of procedures and maintenance of documentation; and 4) to possess at least minimal human resources and infrastructure [

9]. To meet all these criteria, it is urgent that the microbial collections are institutionalized and their institutions become committed to maintaining their collections. This recognition would guarantee minimum requirements and rules to ensure the services’ quality. Therefore, allowing the supply of high-quality microbial resources that, for example, contribute to the reproducibility of research and, consequently, to the credibility of science [

11].

Considering the importance that microorganisms have in promoting plant growth, in the cycling of compounds in nature and for diverse other applications in industry, agriculture and health sector, it is urgent to adopt strategies for the study, conservation and prospecting of microorganisms present in all Brazilian Biomes with emphasis in the biomes less represented in the collections such as Pantanal. The great diversity of plants and animals present in the Pantanal biome, points to a great richness of microorganisms in the most different substrates in this region, as suggested by several authors [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The data herein presented highlight the importance of this type of survey to guide public strategies for conserving the Brazilian microbiota in regions where they are poorly assessed.

Unfortunately, there is a fragile aspect of the current situation in Brazil since most of microbiological collections do not have sufficient financial resources to maintain their collections, as was showed in

Figure 10. This data reveals the risk to which collections are subjected since the lack of reagents and basic supplies and cryopreservation equipment can compromise the quality, purity, and viability of the preserved material. Therefore, the Brazilian microbial collections could benefit from having a sustainability plans that would include external fundraising, inter alia, by selling services and strains. However, it must be stressed the responsibility of the public institutions where the majority of the collections are located and the responsibility of the government of giving financial support to these collections.

In this context, the Brazilian Access and Benefit Sharing legislation – Law 13.123/2015 [

16] – will bring an opportunity to finance activities of Brazilian biological collections through the National Benefit Sharing Fund (FNRB). The Decree 8,772 of 2016 [

17], which regulates the Law, establishes in its article 100 that the

National Benefit Sharing Program is responsible for promoting, among others: I – the conservation of biological diversity; II – recovery, creation and maintenance of ex situ collections of genetic heritage samples. It is determined that resources originated from the economic exploitation of finished products and reproductive material obtained through access to the Genetic Heritage from ex situ collections accredited at SisGen will be made available by the National Benefit Sharing Fund – FNRB [

18]. In this context, the Brazilian Access and Benefit Sharing legislation is an opportunity to finance activities and to maintain Brazilian biological collections through FNRB. However, for collections to receive resources from the Fund, they must be accredited through the Brazilian online system for access and benefit sharing framework – SisGen – whose registration is carried out by the institution’s legal representative.

On the other hand, unfortunately, the Law has been causing some negative impact on the microbiological collections mainly concerning the description of new species. According to the Law 13,123/2015, foreign researchers who want to access native Brazilian biodiversity can only access it if they are associated with public or private Brazilian scientific and technological research institutions [

18], and, therefore, this institution will be responsible for registering the activity in SisGen (

https://sisgen.gov.br/paginas/login.aspx). This requirement also applies to using any Brazilian genetic resource deposited in ex situ collections. Due to this requirement, in recent years international microbiological collections have not accepted deposits of Brazilian micro-organisms. In addition, this situation has also been causing consequences for describing new species of bacteria coming from Brazil since depositing type strains in at least two different culture collections is mandatory. According to da Silva and collaborators [

19], the association requirement defined by the Brazilian Law 13.123/2015 impacts on the ‘unrestricted distribution’ envisaged under Rule 30 of the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP). The impact on the studies involving Brazilian biodiversity is very clear. Despite of the efforts to solve these problems, there is still a long way to go.

Putting all this information together and considering that ex situ collections play a fundamental role in preserving and conserving biodiversity yet involve high-cost activities, Brazilian microbiological culture collections must seek more investments and recognition.

5. Conclusions

Brazilian ex situ collections preserve microorganisms of high importance and with potential for application in different sectors. However, despite all these economic and biotechnological potentials, the data analysis showed severe limitations and fragilities, especially regarding physical infrastructure and human resources, and raises alerts about the risk that Brazilian collections are subjected to.

Finally, we recommend that institutions commit to the maintenance and preservation of their microbiological collections and become responsible for their management and organization. We also recommend that the Brazilian government invest more in taxonomy, data handling, bioinformatics, and culture collections management and training. These supports and investments will strengthen the preservation of Brazilian biodiversity in the different biomes. They will support the bioeconomy, allowing important microorganisms to be applied in several areas, including human health research, antimicrobials, environmental protection, bioinoculants, and biocontrol agents for sustainable agriculture and even for animal and human food, as well as for taxonomic purposes.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology of Brazil, Term of Cooperation, Federal University of Paraná number 14.0003.00/2021. This work was also supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico CNPq: PQ grant Luciane Marinoni process number 311744/2021-4; PQ grant Chirlei Glienke process number 312658/2022-2.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Ministry of Science and Technology of Brazil for supporting this important and unprecedented evaluation. We also acknowledge the Brazilian Society of Zoology for coordinating the project and the Brazilian Societies of Botany, Microbiology, and Virology for their cooperation. We really appreciate the curators for filling out the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- CBD—Convention on Biological Diversity. Brazil 130th country to ratify Nagoya Protocol to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/doc/press/2021/pr-2021-03-24-brazil-en.pdf. 2021.

- Bustamante, M.M.C., Calaça, F.J.S., Pompermaier, V.T., da Silva, M.R.S.S., Silveira, R. (2023). Effects of Land Use Changes on Soil Biodiversity Conservation. In: Søndergaard, N., de Sá, C.D., Barros-Platiau, A.F. (eds) Sustainability Challenges of Brazilian Agriculture. Environment & Policy, vol 64. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Boundy-Mills K, McCluskey K, Elia P, Glaeser JA, Lindner DL, Nobles DR Jr, Normanly J, Ochoa-Corona FM, Scott JA, Ward TJ, Webb KM, Webster K, Wertz JE. Preserving US microbe collections sparks future discoveries. J Appl Microbiol. 2020 Aug;129(2):162-174. [CrossRef]

- Ryan MJ, McCluskey K, Verkleij G, Robert V, Smith D. Fungal biological resources to support international development: Challenges and opportunities. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019 Aug 26;35(9):139. [CrossRef]

- de Capriles, C.H., Mata, S., Middelveen, M. Preservation of fungi in water (Castellani): 20 years. Mycopathologia 106, 73–79 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Ryan MJ, Smith D (2004) Fungal genetic resource centres and the genomic challenge. Mycol Res 108:1351–1362.

- OECD Best Practice for Biological Resource Centres, 2007. https://www.oecd.org/sti/emerging-tech/38777417.pdf.

- da Silva, M., Chame, M., Moratelli, R. Fiocruz Biological Collections: Strengthening Brazil’s biodiversity knowledge and scientific applications opportunities. Biodiversity Data Journal, v. 8, p. 1-12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M., Sá, M. R. (2016). Coleções vivas: As coleções microbiológicas da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Museologia & Interdisciplinaridade, 5(9), 175–187. [CrossRef]

- de Vero, L. Et al. Preservation, Characterization and Exploitation of Microbial Biodiversity: The perspective of the Italian network of Culture Collections. Microorganisms, v. 12, p. 685, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gos FMWR, Savi DC, Shaaban KA, Thorson JS, Aluizio R, Possiede YM, Rohr J and Glienke C (2017). Antibacterial Activity of Endophytic Actinomycetes Isolated from the Medicinal Plant Vochysia divergens (Pantanal, Brazil). Front. Microbiol. 8:1642. Doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01642. [CrossRef]

- Noriler SA, Savi DC, Aluizio R, Palácio-Cortes AM, Possiede YM and Glienke C (2018). Bioprospecting and Structure of Fungal Endophyte Communities Found in the Brazilian Biomes, Pantanal, and Cerrado. Front. Microbiol. 9:1526. [CrossRef]

- Iantas J, Savi DC, Schibelbein RdS, Noriler SA, Assad BM, Dilarri G, Ferreira H, Rohr J, Thorson JS, Shaaban KA and Glienke C (2021). Endophytes of Brazilian Medicinal Plants With Activity Against Phytopathogens. Front. Microbiol. 12:714750. [CrossRef]

- Assad BM, Savi DC, Biscaia SMP, Mayrhofer BF, Iantas J, Mews M, de Oliveira JC, Trindade ES, Glienke C. Endophytic actinobacteria of Hymenachne amplexicaulis from the Brazilian Pantanal wetland produce compounds with antibacterial and antitumor activities, Microbiological Research, 248, 2021. [CrossRef]

- BRAZIL. 2015. Law nº 13,123, May 20th. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 21 Mai. 2015. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/lei/l13123.htm.

- BRAZIL. 2016. Decree nº 8772, May 11th. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 12 Mai. 2016. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/decreto/d8772.htm.

- da Silva, M., Oliveira, D.R. de. The new Brazilian legislation on access to the biodiversity (Law 13,123/15 and Decree 8772/16). Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 49 (2018), pp1-4. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M, Desmeth, P., Venter, N.S., Shouche, Y., Yurkov, A. How legislations affect new taxonomic descriptions. Trends in Microbiology, Volume 31, Issue 2,2023, Pages 111-114. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Brazilian microbiological collections are mainly located in public institutions. Stacked bar plots presenting the number of public (blue) and private (yellow) institutions and microbial locations according to their regional distribution.

Figure 1.

Brazilian microbiological collections are mainly located in public institutions. Stacked bar plots presenting the number of public (blue) and private (yellow) institutions and microbial locations according to their regional distribution.

Figure 2.

Brazilian microbiological collections mostly preserve bacteria and fungi. UpSet plot showing the taxonomic groups preserved in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 2.

Brazilian microbiological collections mostly preserve bacteria and fungi. UpSet plot showing the taxonomic groups preserved in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 3.

Brazilian microbiological collections mostly preserve microrganisms from the Atlantic Forest, Amazon rainforest, Cerrado and Caatinga biomes. UpSet plot showing the represented ecosystems, biomes and environments in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their re-gional distribution.

Figure 3.

Brazilian microbiological collections mostly preserve microrganisms from the Atlantic Forest, Amazon rainforest, Cerrado and Caatinga biomes. UpSet plot showing the represented ecosystems, biomes and environments in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their re-gional distribution.

Figure 4.

Brazilian microbial collections harbor microrganisms of interest in different areas. UpSet plot showing the categories of interest for microorganisms in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 4.

Brazilian microbial collections harbor microrganisms of interest in different areas. UpSet plot showing the categories of interest for microorganisms in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 5.

Brazilian microbial collections mostly present small to moderate sizes. Stacked bar plots presenting the bumber of strains preserved in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 5.

Brazilian microbial collections mostly present small to moderate sizes. Stacked bar plots presenting the bumber of strains preserved in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 6.

Besides cryopreservation, several Brazilian microbial collections still employ classical methods to preserve their strains. UpSet plot presenting the preservation methods employed in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 6.

Besides cryopreservation, several Brazilian microbial collections still employ classical methods to preserve their strains. UpSet plot presenting the preservation methods employed in Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 7.

Most Brazilian microbial collections do not present a specific room to receive and process the biological material. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of a specific room to receive and process the biological material in Brazilian microbial collections.

Figure 7.

Most Brazilian microbial collections do not present a specific room to receive and process the biological material. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of a specific room to receive and process the biological material in Brazilian microbial collections.

Figure 8.

Most Brazilian microbial collections do not present a specific room to store and maintain the isolates. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of a specific room to maintain the isolates in Brazilian microbial collections.

Figure 8.

Most Brazilian microbial collections do not present a specific room to store and maintain the isolates. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of a specific room to maintain the isolates in Brazilian microbial collections.

Figure 9.

Brazilian microbial collections have limitations in several infrastructural aspects. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of a security system (a) fire protection systems (b) and adequate electrical installations (c) for the microbial collections according to their regional distribution.

Figure 9.

Brazilian microbial collections have limitations in several infrastructural aspects. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of a security system (a) fire protection systems (b) and adequate electrical installations (c) for the microbial collections according to their regional distribution.

Figure 10.

Brazilian microbial collections lack financial resources. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of financial resources for the Brazilian microbial collections according to their regional distribution.

Figure 10.

Brazilian microbial collections lack financial resources. Stacked bar plots presenting the availability status of financial resources for the Brazilian microbial collections according to their regional distribution.

Figure 11.

Low number of dedicated professionals associated to Brazilian microbial collections. Grouped bar plots presenting the personnel status in Brazilian microbial collections for IT support (brown), Data digitization (red), Organization and maintenance (yellow), and Management (gray).

Figure 11.

Low number of dedicated professionals associated to Brazilian microbial collections. Grouped bar plots presenting the personnel status in Brazilian microbial collections for IT support (brown), Data digitization (red), Organization and maintenance (yellow), and Management (gray).

Figure 12.

Most Brazilian microbial collections are between 11 and 30 years old. Stacked bar plots presenting the age of the Brazilian microbial collections since their foundation, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 12.

Most Brazilian microbial collections are between 11 and 30 years old. Stacked bar plots presenting the age of the Brazilian microbial collections since their foundation, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 13.

Several Brazilian microbial collections lack formal recognition by their institutions. Stacked bar plots presenting the formal recognition status for microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 13.

Several Brazilian microbial collections lack formal recognition by their institutions. Stacked bar plots presenting the formal recognition status for microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 14.

Most Brazilian microbial collections lack curatorship positions with formal recognition and financial compensation. Stacked bar plots presenting the status of curatorship positions in microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 14.

Most Brazilian microbial collections lack curatorship positions with formal recognition and financial compensation. Stacked bar plots presenting the status of curatorship positions in microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 15.

Brazilian microbial collections offer a diverse set of services for both public and private institutions. UpSet plot presenting the services provided the Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

Figure 15.

Brazilian microbial collections offer a diverse set of services for both public and private institutions. UpSet plot presenting the services provided the Brazilian microbial collections, according to their regional distribution.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).