Submitted:

06 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

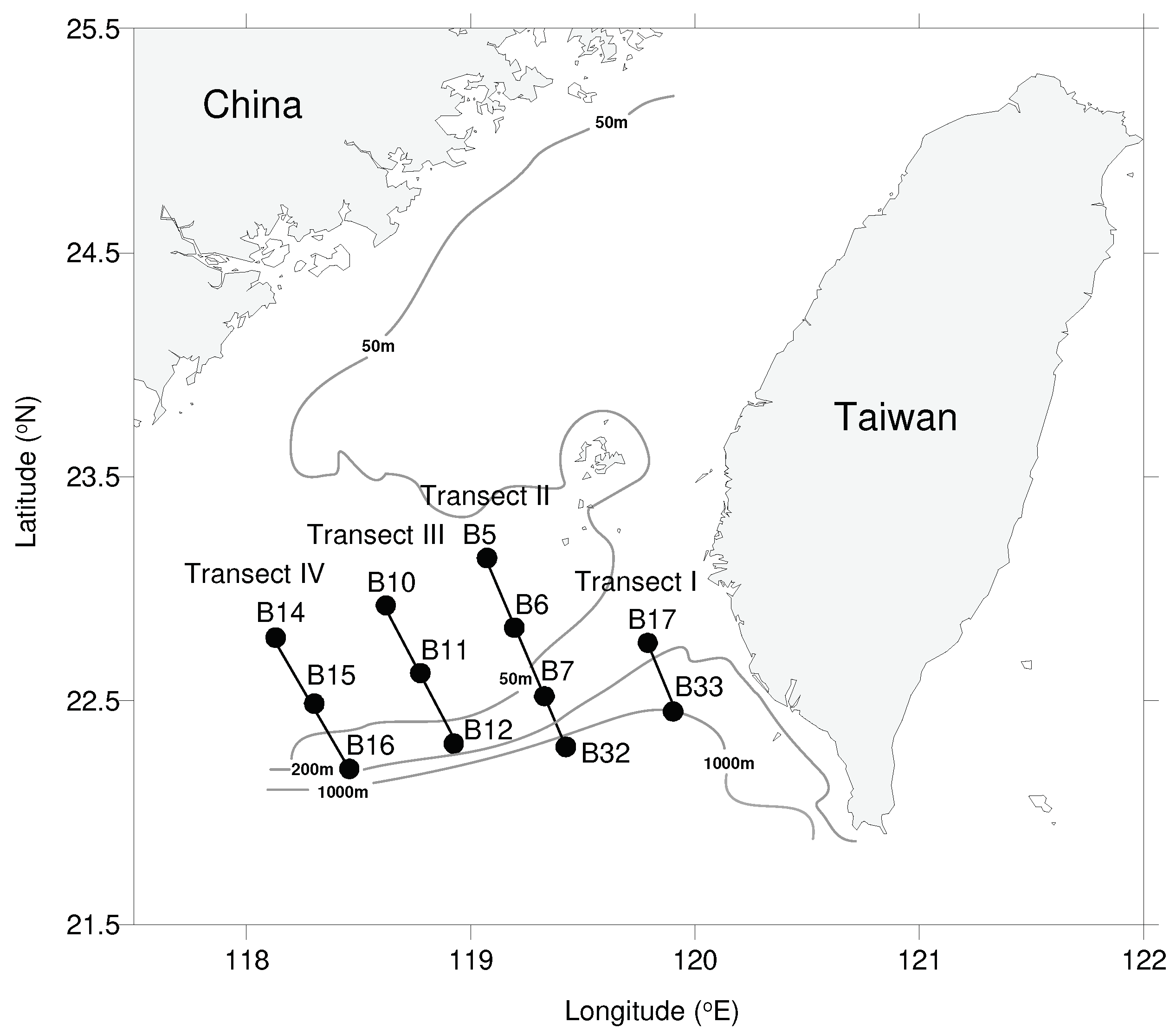

2.1. Oceanographic and Biological Sampling

2.2. Identification and Enumeration

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Resaults

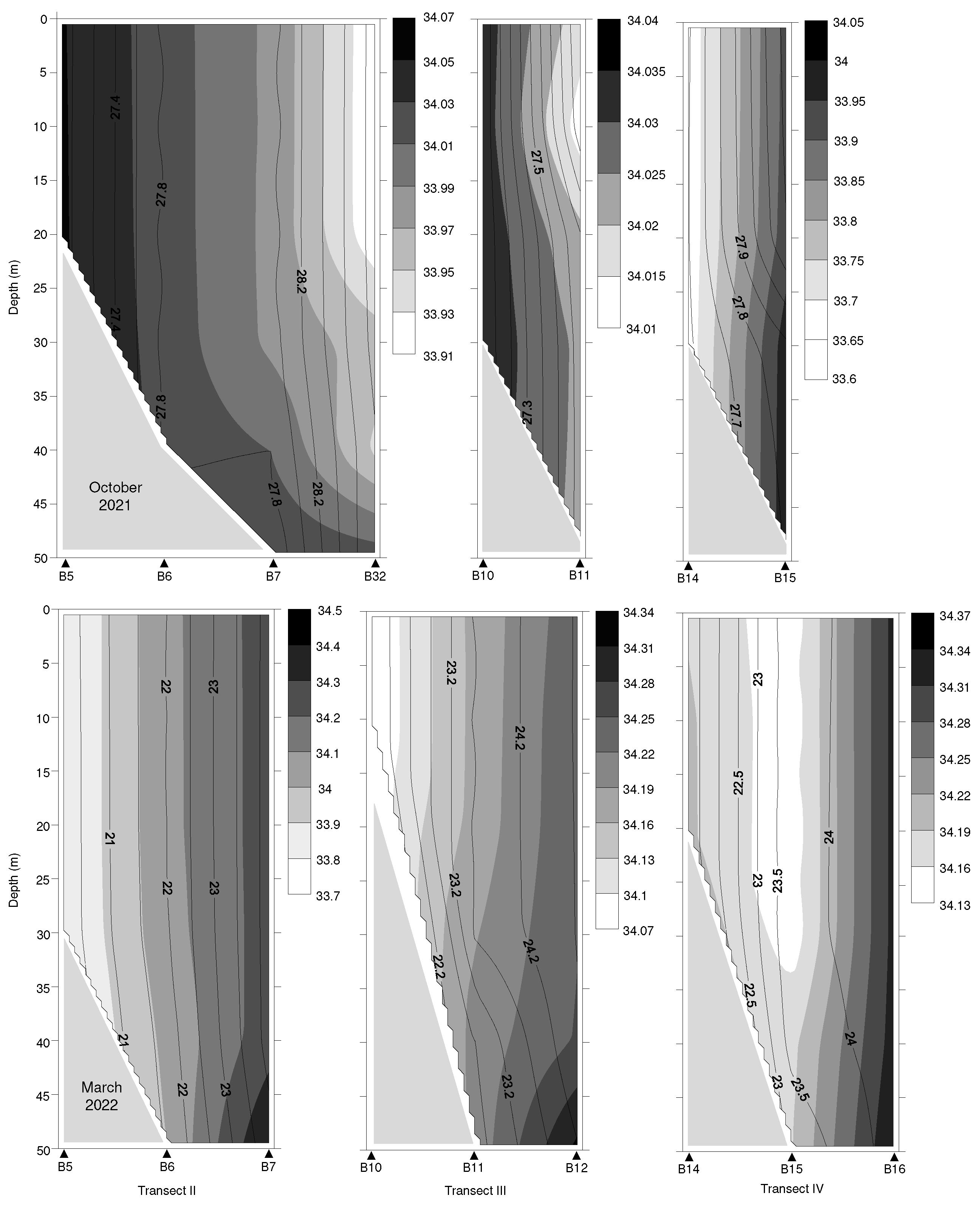

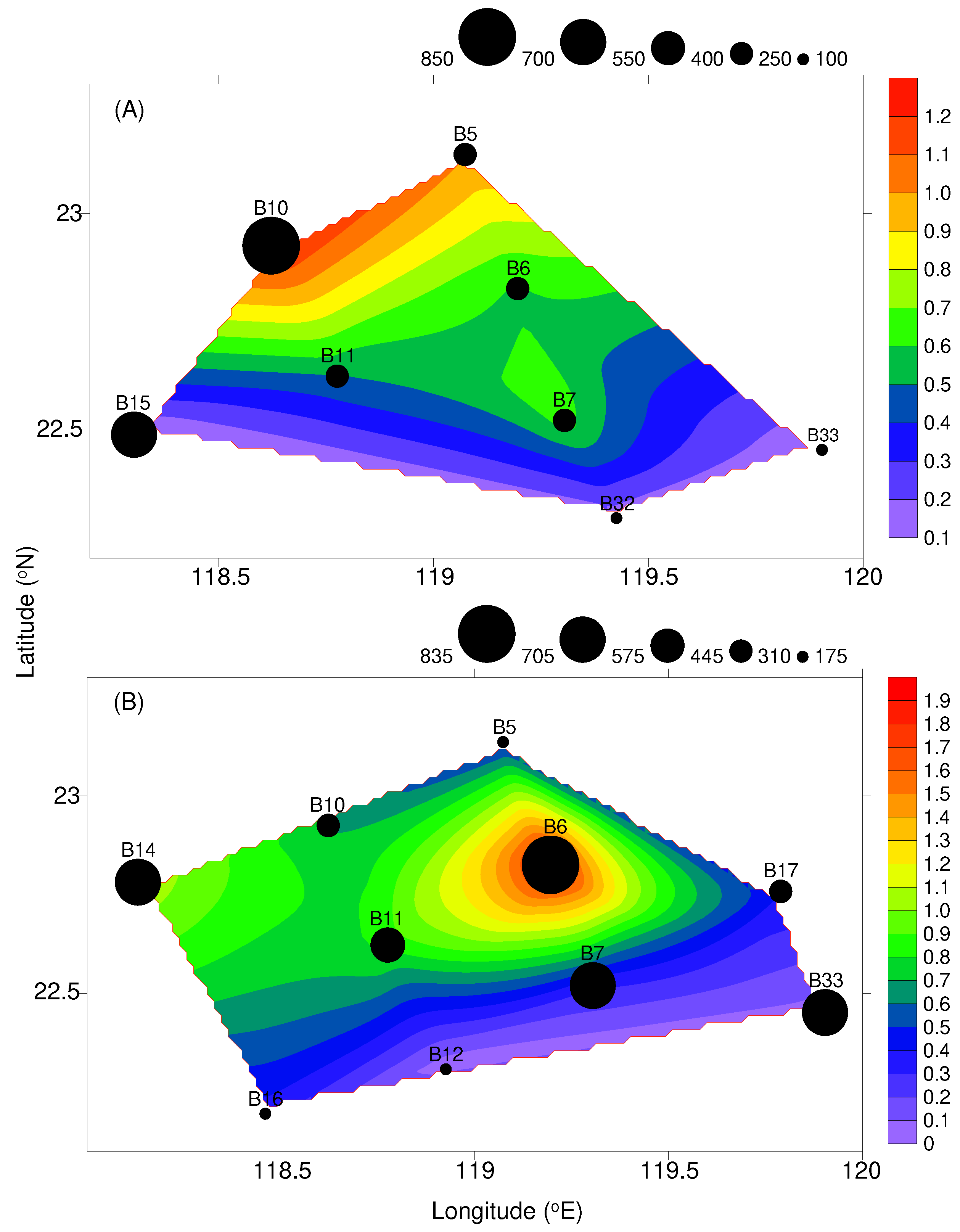

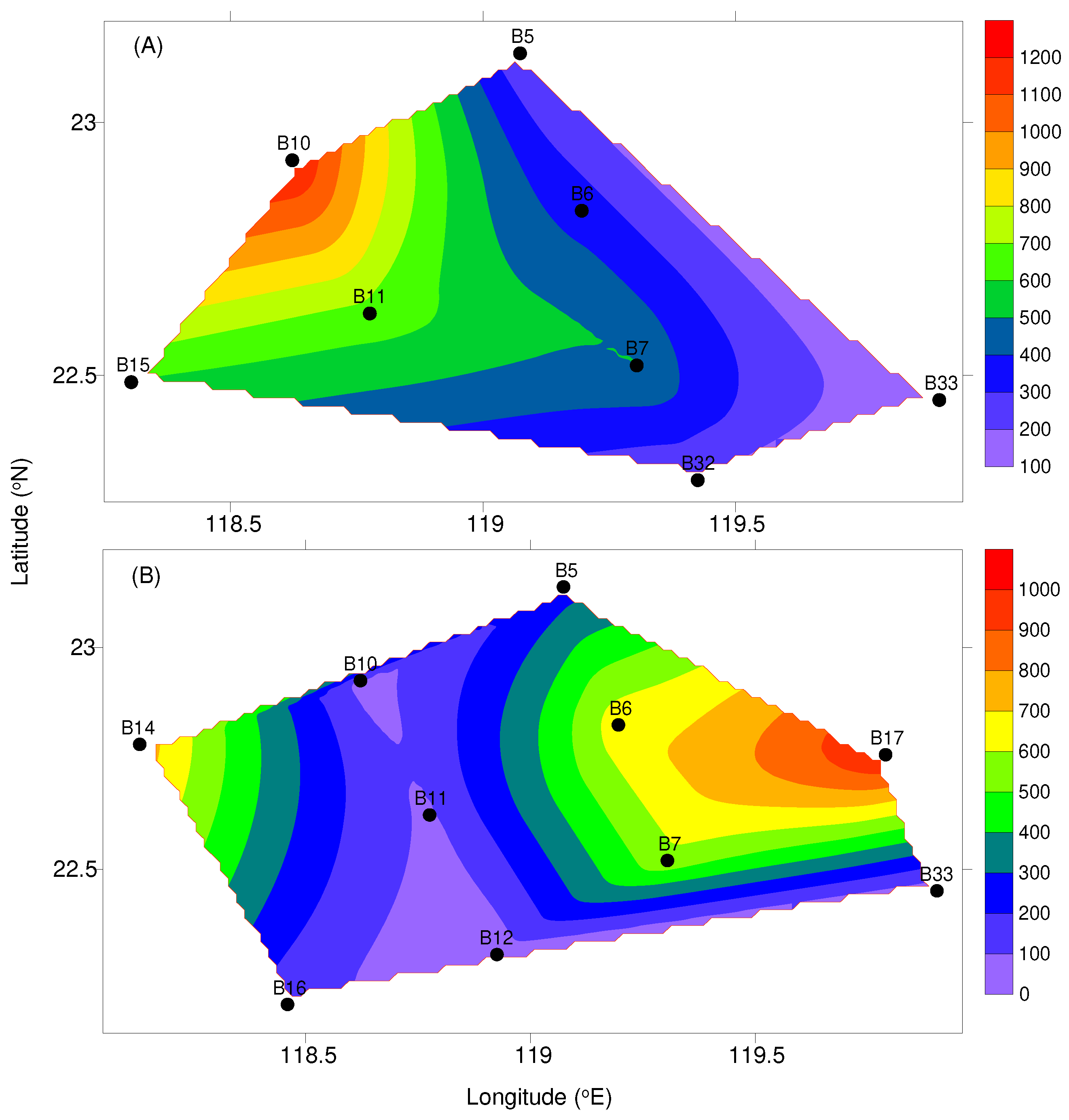

3.1. Hydrographic and Biological Conditions

3.2. Composition of Fish Larvae

3.3. Temporal Changes in Abundance and Diversity of Fish Larvae

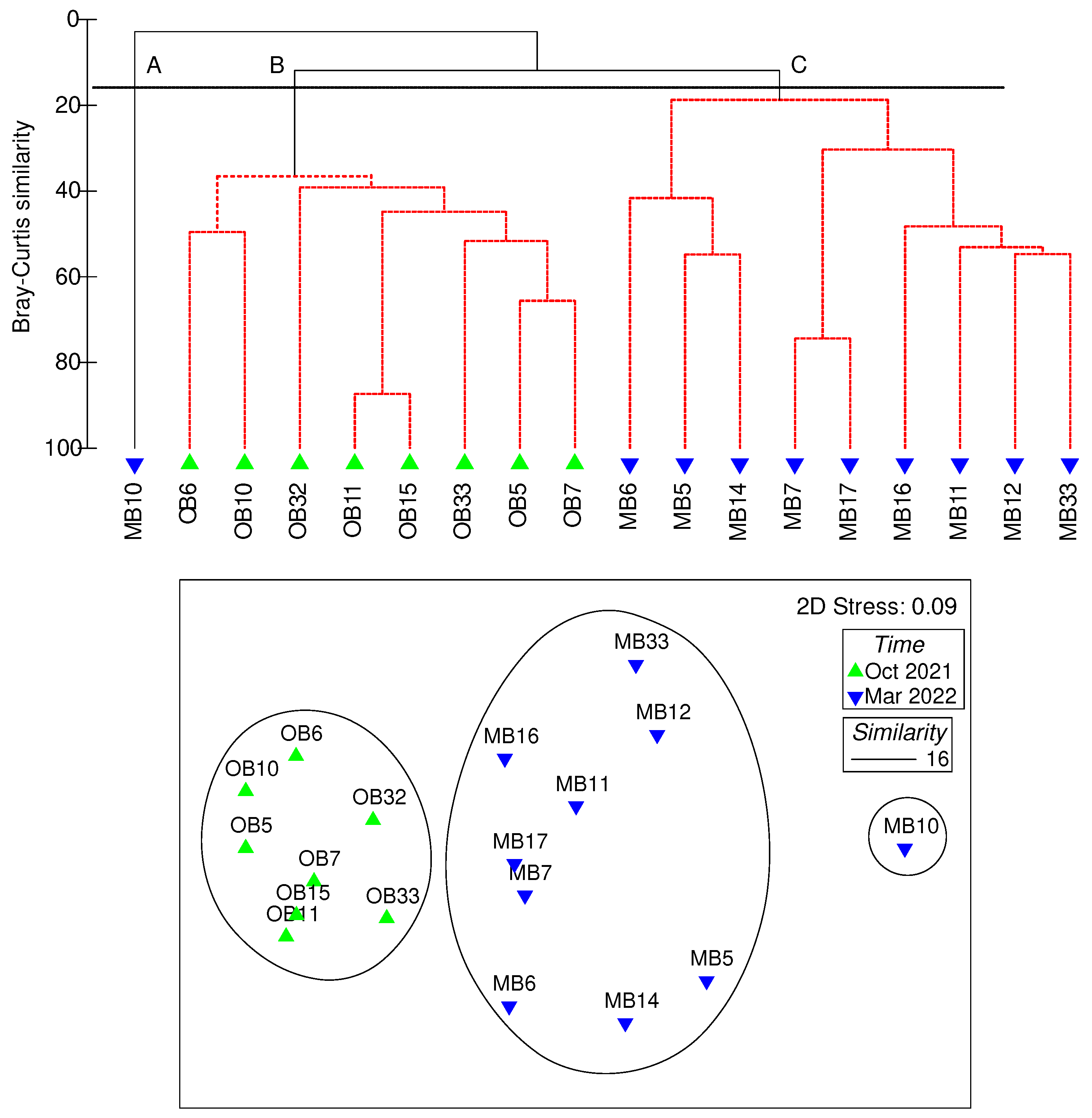

3.4. Assemblages of Fish Larvae

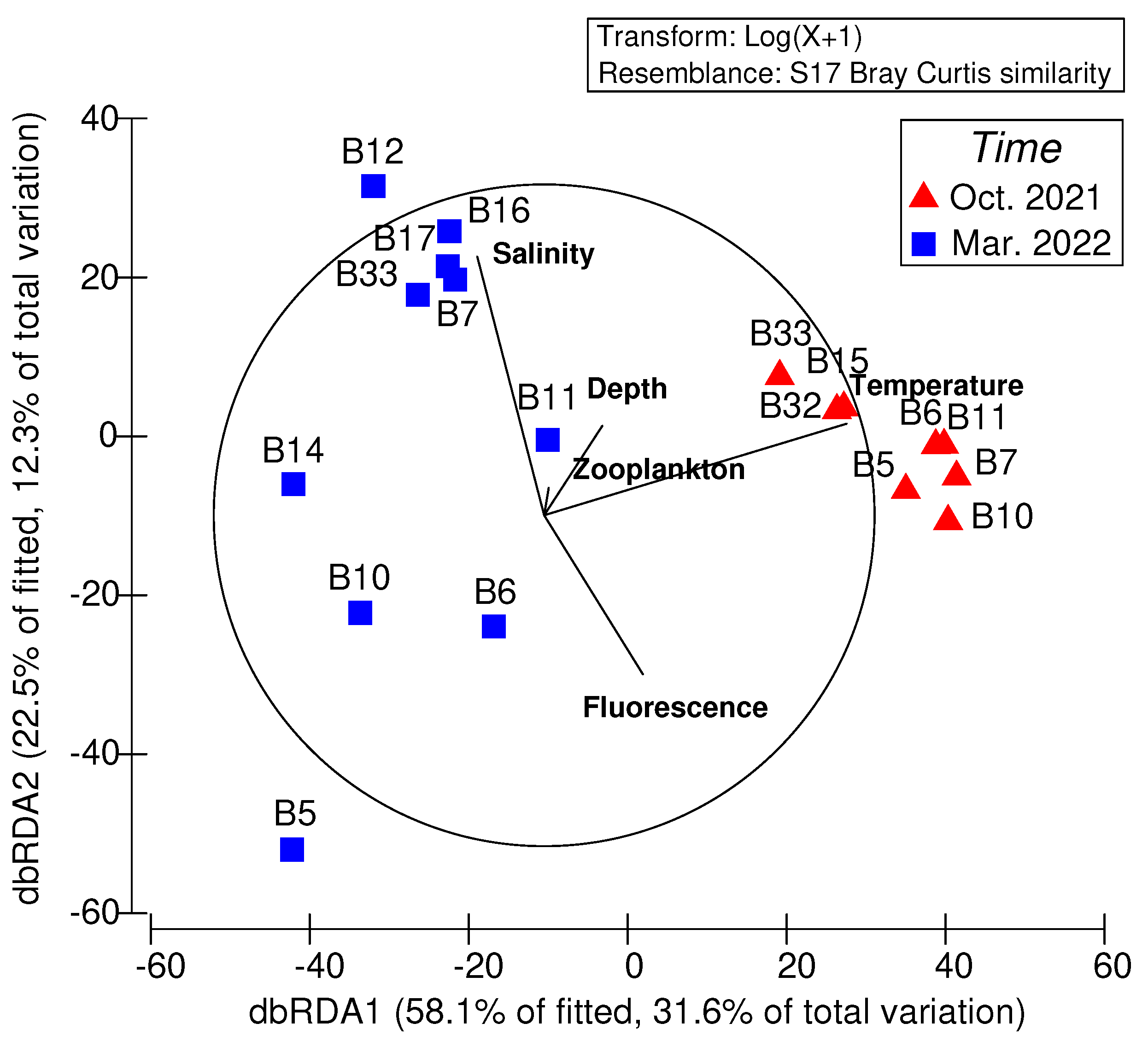

3.5. Correlation between Fish Larvae Assemblages and Environmental Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franco-Gordo, C.; Godínez-Domínguez, E.; Suárez-Morales, E. Larval fish assemblages in waters off the central Pacific coast of Mexico. J. Plankton Res. 2002, 24, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatés, A.; Olivar, M.P.; Salat, J.; Palomera, I.; Alemany, F. Physical and biological processes controlling the distribution of fish larvae in the NW Mediterranean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2007, 74, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.C.; Leis, J.M.; Hausfeld, H.F. Seasonal and spatial distribution of fish larvae in waters over the North West Continental Shelf of Western Australia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1986, 31, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.J.; Morse, W.W.; Kendall, A.W.J. A comparison of larval fish assemblages in the temperate zone of the northeast Pacific and northwest Atlantic Oceans. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1993, 53, 588–644. [Google Scholar]

- Olivar, M.P.; Emelianov, M.; Villate, F.; Uriarte, I.; Maynou, F.; Álvarez, I.; Morote, E. The role of oceanographic conditions and plankton availability in larval fish assemblages off the Catalan coast (NW Mediterranean). Fish. Oceanogr. 2010, 19, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakun, A. Fronts and eddies as key structures in the habitat of marine fish larvae: opportunity, adaptive response and competitive advantage. Sci. Mar. 2006, 70, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni, J.J. Fisheries oceanography and the ecology of early life histories of fishes: a perspective over fifty years. Sci. Mar. 2005, 69, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.; Wang, J.; Chern, C.S.; Chao, S.Y. Seasonal variation of the circulation in the Taiwan Strait. J. Mar. Syst. 2002, 35, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.; Sheu, D.D.; Kuo, H.M. Water mass and throughflow transport variability in the Taiwan Strait. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, C12012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chern, C.S. On the Kuroshio branch in the Taiwan Strait during wintertime. Prog. Oceanogr. 1988, 21, 469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Shimada, T.; Lee, M.A.; Sakaida, F.; Kawamura, H. Wintertime sea surface temperature fronts in the Taiwan Strait. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L23603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

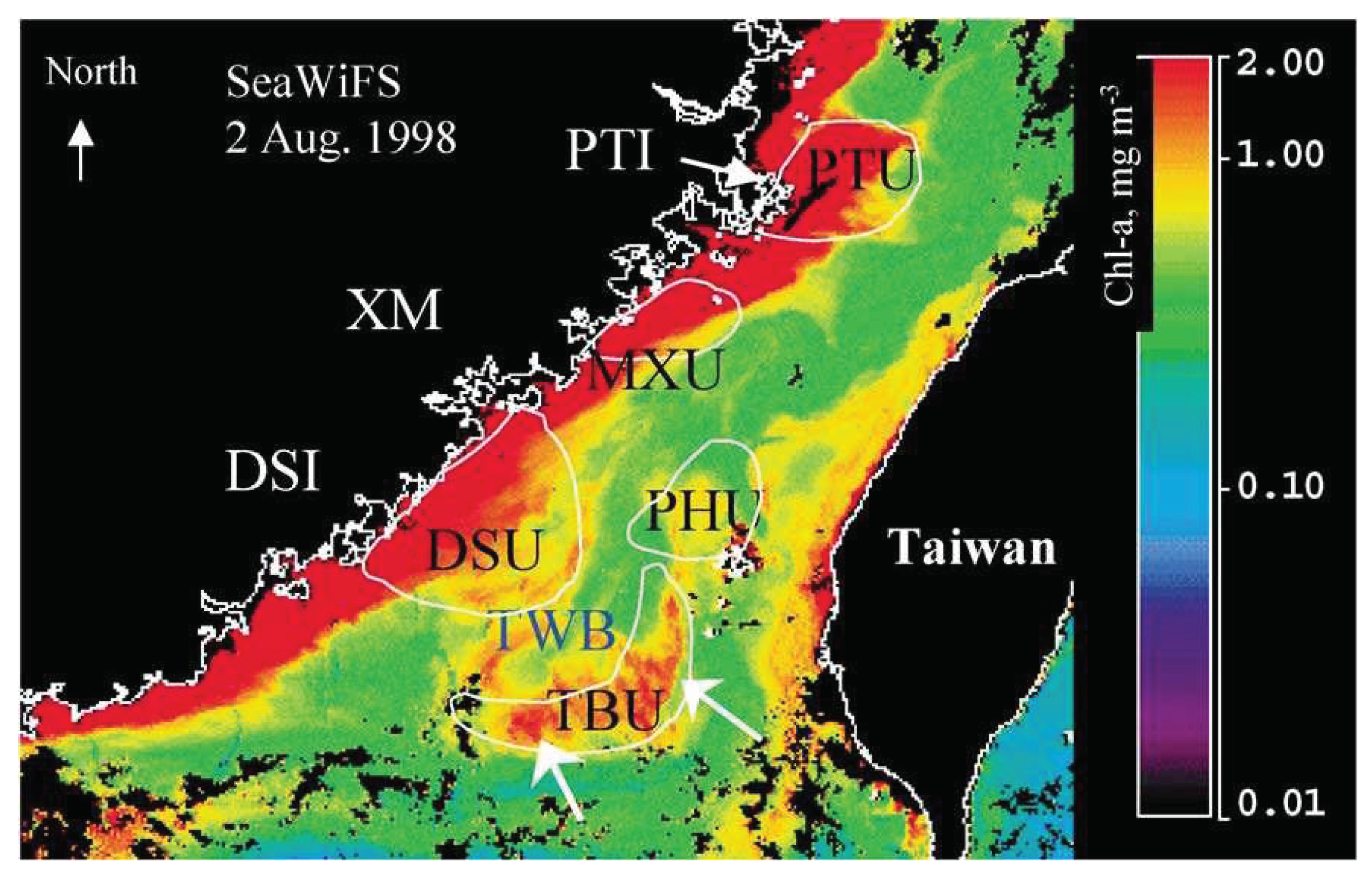

- Tang, D.L.; Kester, D.R.; Ni, I.H.; Kawamura, H.; Hong, H.S. Upwelling in the Taiwan Strait during the summer monsoon detected by satellite and shipboard measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Kawamura, H.; Hong, H.; Pan, W. A review of research on the upwelling in the Taiwan Strait. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2003, 73, 605–628. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, P.Y.; Shimada, T.; Lan, K.W.; Lee, M.A.; Liao, C.H. Assessing summertime primary production required in changed marine environments in upwelling ecosystem around the Taiwan Bank. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryther, J.H. Photosynthesis and fish production in the sea. Science 1969, 166, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, Z. Introduction. In Minnan-Taiwan Bank fishing ground upwelling ecosystem study (pp. i-ii); Hong, H.S., Qiu, S.Y., Ruan, W.Q., Hong, Q.C., Eds.; Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1991; pp. i–ii. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.S.; Qiu, S.Y.; Ruan, W.Q.; Hong, Q.C. 1991. Minnan-Taiwan Bank fishing ground upwelling ecosystem study. In Minnan-Taiwan Bank fishing ground upwelling ecosystem study; Hong, H.S., Qiu, S.Y., Ruan, W.Q., Hong, Q.C., Eds.; Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1991; pp. 1–18. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.Y.; Lo, W.T.; Wu, L.J.; Liu, D.C. Larval fish assemblages in the Taiwan Strait, western North Pacific: linking with monsoon-driven mesoscale current system. Fish. Oceanogr. 2012, 21, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okiyama, M. (Ed.) An Atlas of the Early Stage Fishes in Japan; Tokai University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1988. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Leis, J.M.; Trnski, T. The Larvae of Indo-Pacific Shorefishes; New South Wales University Press: Sidney, Australia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T.S. Fish larvae of Taiwan; National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium: Checheng, Taiwan, ROC, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Pielou, E.C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 1966, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation, 2nd ed.; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2001; 172p. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, J.B.; Wish, M. Multidimensional Scaling; Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Application in the Social Sciences; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Aust. Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, B.H.; Anderson, M.J. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a common on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 2001, 82, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.W.; Jan, S.; Liu, K.K. Nutrient fluxes through the Taiwan Strait in spring and summer 1999. J. Oceanogr. 2001, 57, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Comas, C.; Stemmann, L.; Ibanez, F.; Berline, L.; Mazzocchi, M.G.; Gasparini, S.; Picheral, M.; Gorsky, G. Zooplankton long-term changes in the NW Mediterranean Sea: Decadal periodicity forced by winter hydrographic conditions related to large-scale atmospheric changes? J. Mar. Syst. 2011, 87, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, D.; Hunt, B.P.V.; Pakhomov, E.A.; Mackas, D.L. Mesozooplankton community seasonal succession and its drivers: Insights from a British Columbia, Canada, fjord. J. Mar. Syst. 2013, 115–116, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.H.; Chen, C.T.A.; Bai, Y.; He, X. Elevated primary productivity triggered by mixing in the quasi-cul-de-sac Taiwan Strait during the NE monsoon. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.A.; Miskiewicz, A.G. Larval fish assemblages in south-east Australian coastal waters: seasonal and spatial structure. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2000, 50, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.Y.; Meng, P.J.; Chang, Y.C.; Lo, W.T. Temporal and spatial occurrence of mesopelagic fish larvae during epipelagic drift associated with hydrographic features in the Gaoping coastal waters off southwestern Taiwan. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2017, 9, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.Y.; Lo, W.T.; Liao, C.C.; Meng, P.J. Shifts in the assemblage of summer mesopelagic fish larvae in the Gaoping waters of southwestern Taiwan: a comparison between El Niño events and regular years. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A.; Lee, K.T.; Shiah, G.Y. Environmental factors associated with the formation of larval anchovy fishing grounds in the coastal waters of southwest Taiwan. Mar. Biol. 1995, 121, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.S.; Young, S.S.; Chen, C.S. Monthly variation of larval anchovy fishery in I-lan Bay, NE Taiwan, with an evaluation for optimal fishing season. J. Fish. Soc. Taiwan 1997, 24, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.Y.; Tseng, Y.H.; Chiu, T.S.; Shen, M.L.; Hsieh, C.H. Using coupled fish behavior-hydrodynamic model to investigate spawning migration of Japanese anchovy, Engraulis japonicus, from the East China Sea to Taiwan. Fish. Oceanogr. 2012, 21, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Chao, S.Y. A climatological description of circulation in and around the East China Sea. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 2003, 50, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.S.; Chen, C.S. Growth and temporal variation of two Japanese anchovy cohorts during their recruitment to the East China Sea. Fish. Res. 2001, 53, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakabo, T. (Ed.) Fishes of Japan with Pictorial Keys to the Species, English ed.; Tokai University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sassa, C.; Moser, H.G.; Kawaguchi, K. Horizontal and vertical distribution patterns of larval myctophid fishes in the Kuroshio Current region. Fish. Res. 2002, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, Y.; Nakata, H. Effect of the mesoscale hydrographic features on larval fish distribution across the shelf break of East China Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 2007, 27, 1616–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassa, C.; Kawaguchi, K.; Hirota, Y.; Ishida, M. Distribution patterns of larval myctophid fish assemblages in the subtropical-tropical waters of the western North Pacific. Fish. Oceanogr. 2004, 13, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A.; Wang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.K.; Chen, W.Y.; Wu, L.J.; Liu, D.C.; Wu, J.L.; Teng, S.Y. Summer assemblages of ichthyoplankton in the waters of the East China Sea shelf and around Taiwan in 2007. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2013, 21, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, E.H. Mesopelagic and bathypelagic fishes in the California current region. Calif. Coop. Ocean. Fish. Invest. Rep. 1969, 13, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatés, A.; Masó, M. Effect of a shelf-slope front on the spatial distribution of mesopelagic fish larvae in the Western Mediterranean. Deep-Sea Res. 1990, 37, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhling, B.A.; Beckley, L.E.; Olivar, M.P. Ichthyoplankton assemblage structure in two mesoscale Leeuwin Current eddies, eastern Indian Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 2007, 54, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, H.G.; Smith, P.E. Larval fish assemblages and oceanic boundaries. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1993, 53, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | October 2021 | March 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental variables | ||

| Temperature (°C) | 27.87 ± 0.67 | 23.11 ± 1.70 |

| Salinity | 33.95 ± 0.12 | 34.15 ± 0.15 |

| Fluorescence (mg m-3) | 0.66 ± 0.51 | 0.72 ± 0.53 |

| Zooplankton (ind. m-3) | 381 ± 227 | 451 ± 226 |

| Fish larvae | ||

| Abundance (ind. 1000 m-3) | 480 ± 363 | 362 ± 364 |

| Species number (total) | 14 ± 6 (66) | 18 ± 2 (105) |

| Species diversity (H’) | 1.96 ± 0.52 | 1.99 ± 0.77 |

| Species evenness (J’) | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.13 |

| Family | October 2021 | Family | March 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of taxa | Contribution of family to total abundance (%) | Number of taxa | Contribution of family to total abundance (%) | ||

| Engraulidae | 2 | 26.23 | Myctophidae | 14 | 36.84 |

| Gobiidae | 5 | 16.45 | Clupeidae | 1 | 12.90 |

| Apogonidae | 1 | 14.07 | Ammodytidae | 1 | 6.88 |

| Bregmacerotidae | 2 | 9.50 | Gobiidae | 2 | 3.39 |

| Myctophidae | 10 | 8.55 | Sparidae | 5 | 3.36 |

| Trichiuridae | 1 | 3.38 | Trichiuridae | 2 | 3.09 |

| Percichthyidae | 3 | 3.16 | Mullidae | 2 | 2.84 |

| Bothidae | 3 | 1.49 | Scombridae | 6 | 2.69 |

| Sciaenidae | 2 | 1.29 | Nomeidae | 2 | 2.45 |

| Trichonotidae | 1 | 1.17 | Mugilidae | 1 | 2.21 |

| Labridae | 3 | 1.13 | Tetraodontidae | 2 | 2.09 |

| Synodontidae | 3 | 1.17 | |||

| Gempylidae | 3 | 1.11 | |||

| Pleuronectidae | 2 | 1.10 | |||

| Carangidae | 10 | 1.01 | |||

| Total | 33 | 86.41 | Total | 56 | 83.13 |

| Taxon | October 2021 | Taxon | March 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | RA | Mean ± SD | RA | ||

| Engraulis japonicus | 117 ± 307 | 24.38 | Diaphus slender type | 67 ± 166 | 18.38 |

| Apogon sp. | 63 ± 97 | 13.14 | Clupeidae gen. sp. | 47 ± 139 | 12.90 |

| Gobiidae gen. spp. | 56 ± 68 | 11.59 | Benthosema pterotum | 38 ± 53 | 10.42 |

| Bregmaceros sp. | 31 ± 61 | 6.41 | Bleekeria mitsukurii | 25 ± 42 | 6.88 |

| Myctophidae gen. spp. | 17 ± 15 | 3.59 | Gobiidae gen. spp. | 12 ± 28 | 3.31 |

| Tridentiger sp. | 16 ± 26 | 3.38 | Trichiurus lepturus | 10 ± 14 | 2.86 |

| Trichiurus lepturus | 15 ± 26 | 3.15 | Cubiceps pauciradiatus | 9 ± 9 | 2.39 |

| Bregmaceros nectabanus | 12 ± 20 | 2.47 | Planiliza sp. | 8 ± 17 | 2.21 |

| Notoscopelus resplendens | 11 ± 32 | 2.32 | Mullidae gen. sp. | 8 ± 20 | 2.09 |

| Lateolabrax sp. | 7 ± 18 | 1.40 | Takifugu sp. | 8 ± 16 | 2.09 |

| Percichthyidae gen. sp. | 7 ± 11 | 1.40 | Diaphus stubby type | 7 ± 16 | 1.83 |

| Asterorhombus sp. | 5 ± 14 | 1.09 | Sparidae gen. spp. | 6 ± 10 | 1.69 |

| Nibea sp. | 5 ± 15 | 1.09 | Ceratoscopelus warmingii | 6 ± 13 | 1.68 |

| Acanthopagrus sp. | 6 ± 17 | 1.52 | |||

| Myctophum sp. | 5 ± 10 | 1.34 | |||

| Scomberomorus spp. | 4 ± 12 | 1.07 | |||

| Average similarity (%) | A (–) | B (43.21) | C (30.51) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sim/SD | C (%) | Sim/SD | C (%) | Sim/SD | C (%) | |||

| Less than two samples in group |

Gobiidae gen. spp. | 3.88 | 35.54 | Benthosema pterotum | 1.49 | 36.77 | ||

| Myctophidae gen. spp. | 1.33 | 24.89 | Cubiceps pauciradiatus | 0.66 | 33.39 | |||

| Apogon sp. | 0.64 | 12.52 | Trichiurus lepturus | 0.57 | 11.14 | |||

| Engraulis japonicus | 0.50 | 6.46 | Bleekeria mitsukurii | 0.36 | 7.54 | |||

| Trichiurus lepturus | 0.45 | 6.33 | Planiliza sp. | 0.29 | 2.91 | |||

| Tridentiger sp. | 0.49 | 5.13 | ||||||

| Total | - | 90.87 | Total | - | 91.75 | |||

| Variable | SS (trace) | Pseudo-F | P-value | % Variation explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 15021 | 5.8473 | 0.001* | 26.76 |

| Salinity | 7355.1 | 2.4130 | 0.026* | 13.10 |

| Bottom depth | 2663.6 | 0.7971 | 0.611 | 4.74 |

| Fluorescence | 2915.7 | 0.8767 | 0.515 | 5.19 |

| Zooplankton | 2679.5 | 0.8021 | 0.585 | 4.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).