Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

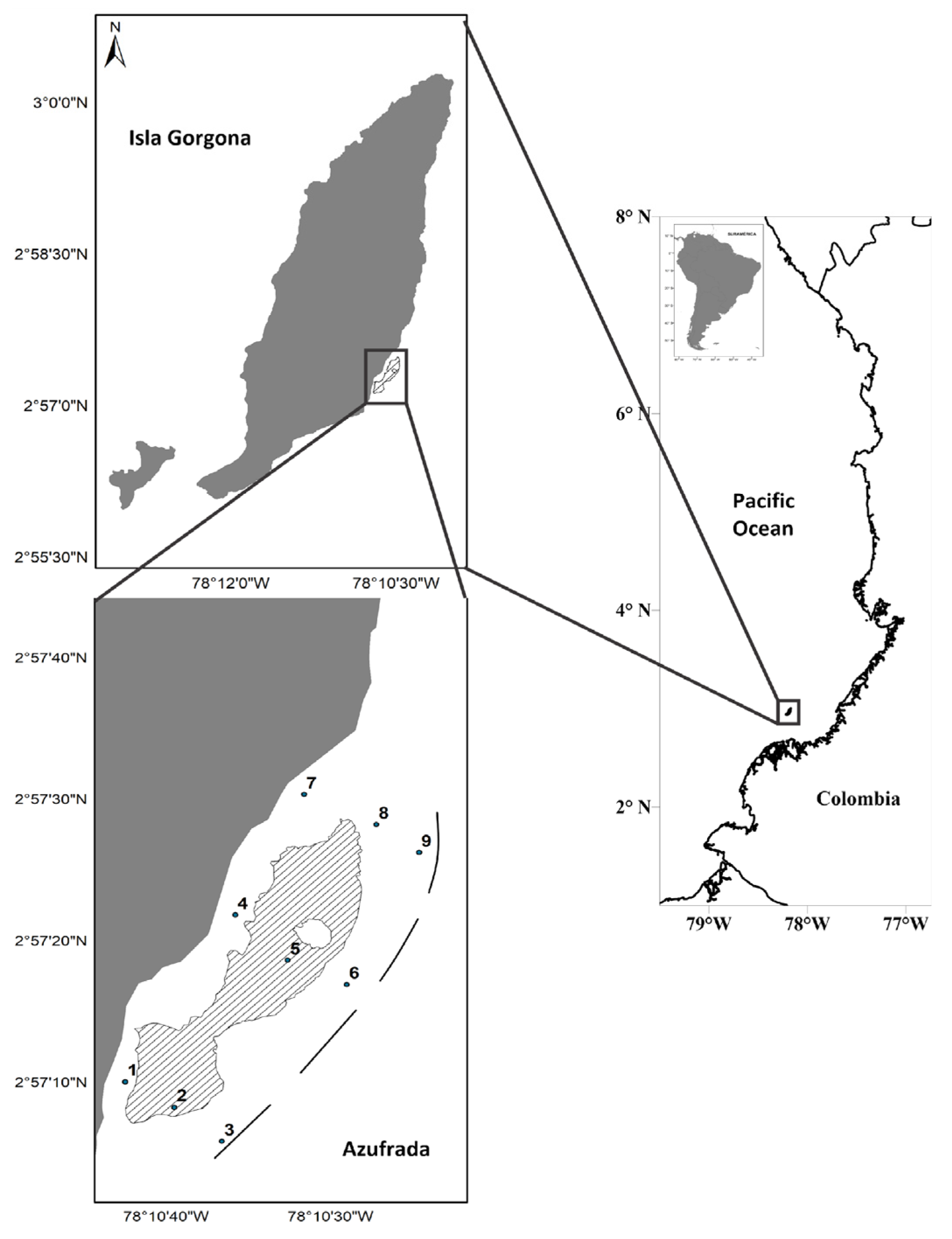

2. Materials and Methods

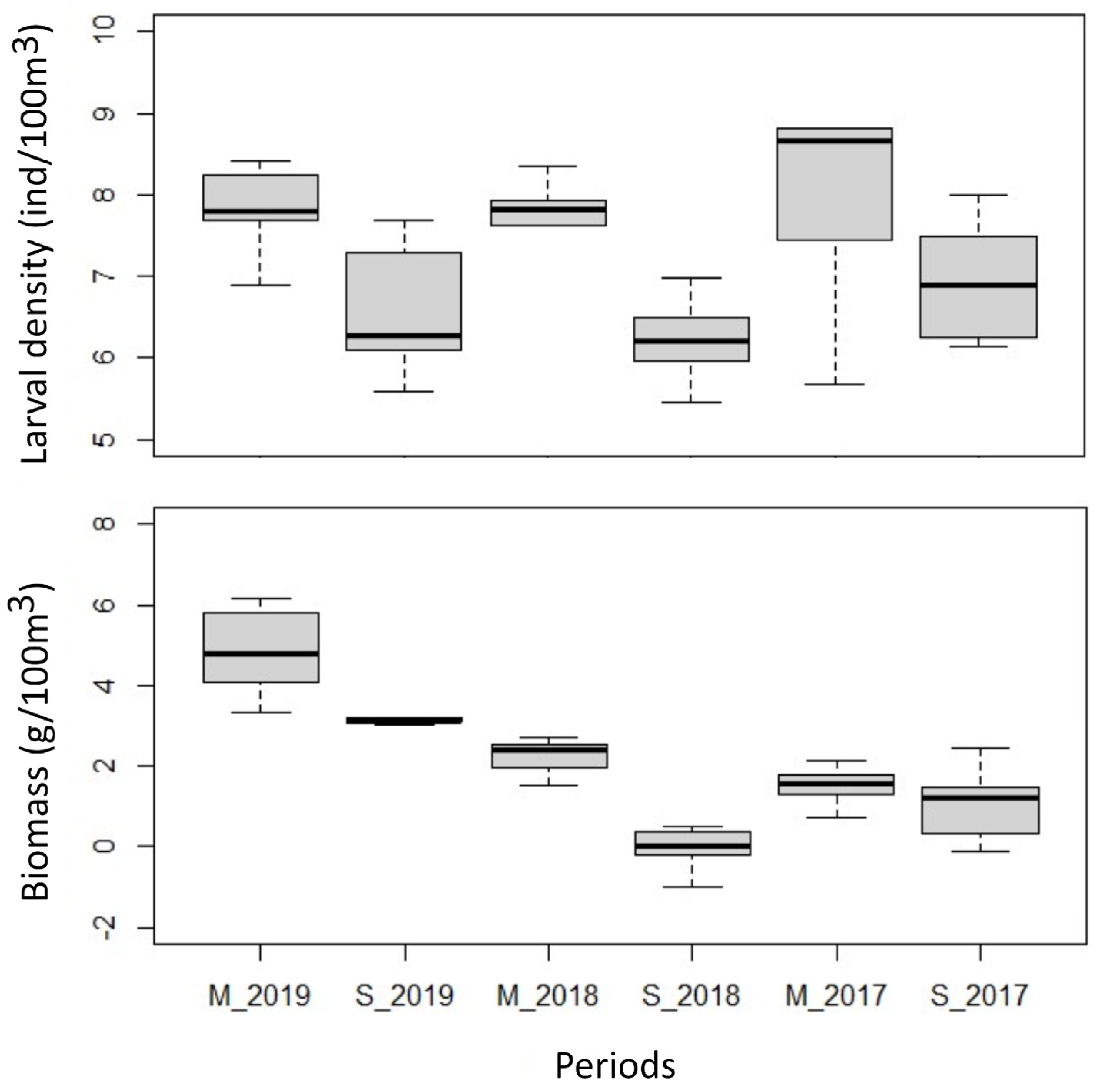

3. Results

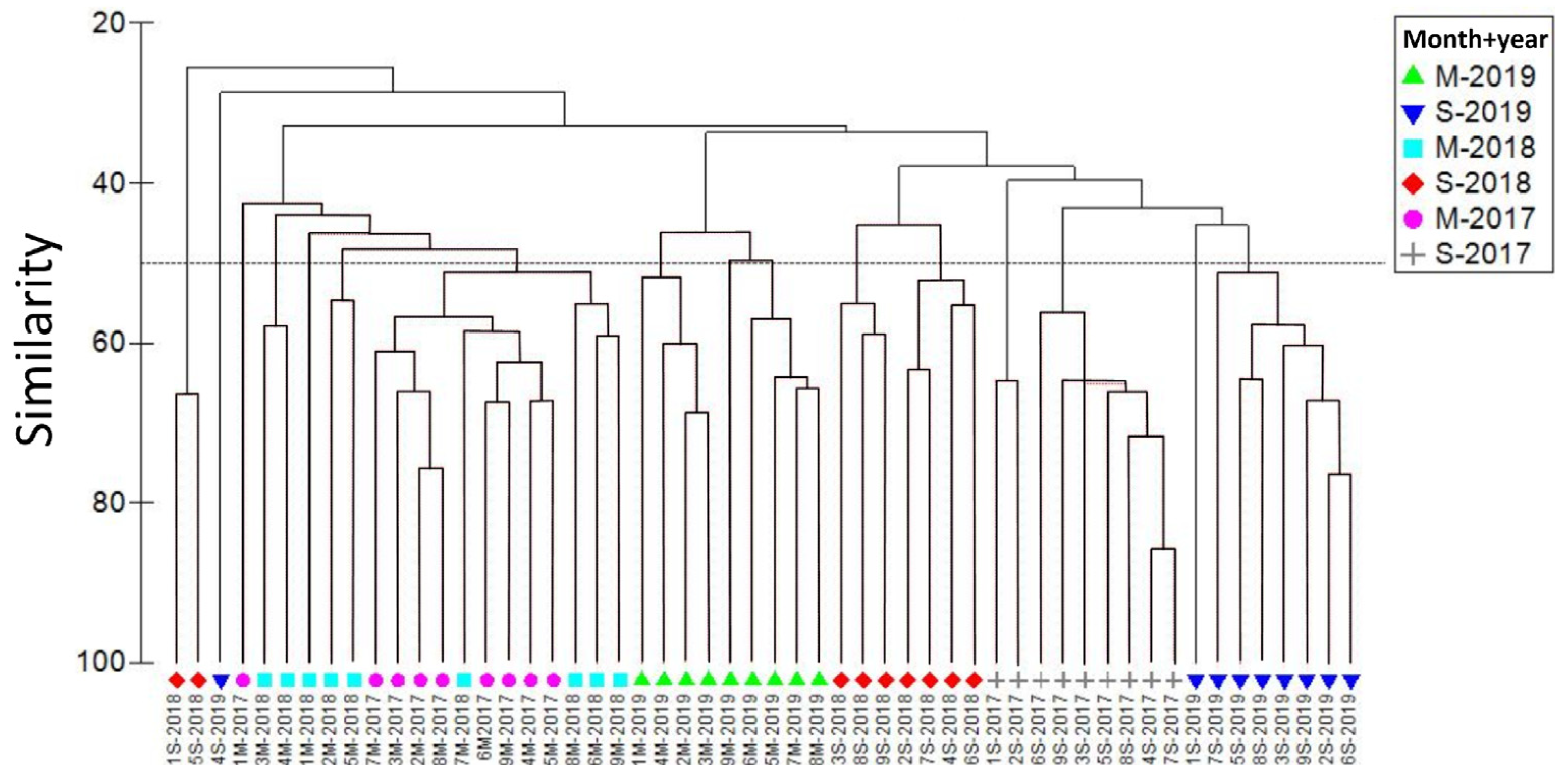

3.1. Fish Larval Assemblage Composition and Structure

3.2. Ambient Conditions

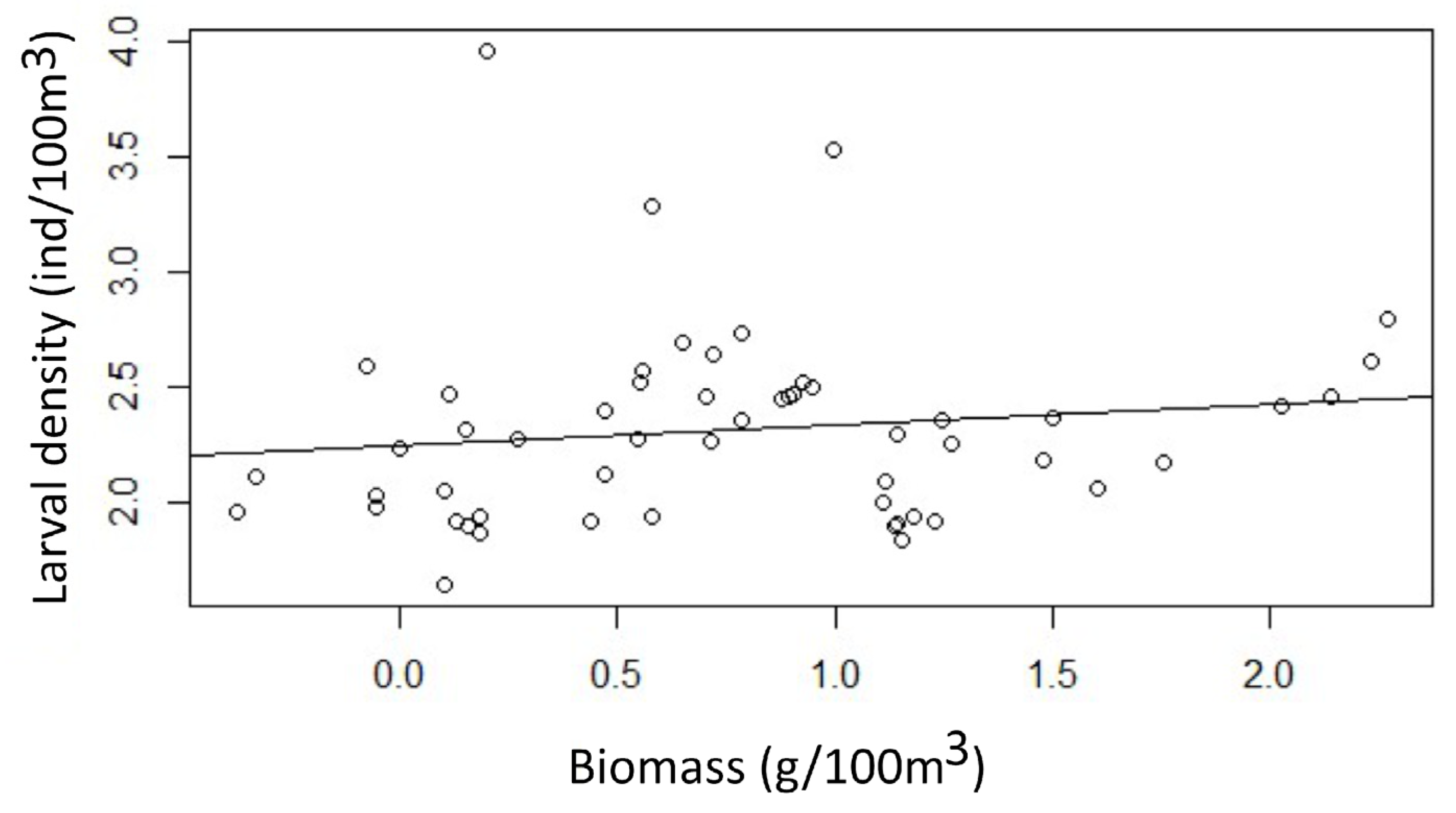

3.3. Relationship Between Fish Larval Assemblages and Environmental Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amador, J.A.; Alfaro, E.J.; Lizano, O.G.; Magaña, V.O. Atmospheric forcing of the eastern tropical Pacific: a review. Prog. Oceanogr. 2006, 69, 101–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, P.C.; Talley, L.D. Hydrography of the eastern tropical Pacific: a review. Progress. Oceanogr. 2006, 69, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, P.C.; Lavín, M.F. Oceanographic Conditions of the Eastern Tropical Pacific. In Coral Reefs of the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Coral Reefs of the World; Glynn, P.; Manzello, D.; Enochs, I., Eds., vol 8.; Springer, Dordrecht, 2017; pp. 59-83. [CrossRef]

- Eslava, J.A. (1993). Climatología. En P. Leyva (Ed.), Colombia Pacífico. Tomo I; Fondo para la protección del medio ambiente, FEN, Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia, 1993; pp. 136–147.

- Velandia, M.C.; Scheel, M.; Puentes, C.; Durán, D.; Osorio, P.; Delgado, P.; Obando, N.; Prieto, A.; Díaz, J.M. 2019.

- Sale, P.F. Connectivity, recruitment variation, and the structure of reef fish communities. Integr Comp Biol. [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.; Enochs, I.C.; Sibaja-Cordero, J.; Hernández, L.; Alvarado, J.J.; Breedy, O. ;... Zapata, F.A. Marine biodiversity of Eastern Tropical Pacific coral reefs. In Coral reefs of the eastern tropical Pacific; Glynn et al., Eds.; Springer, Dordrecht, 2017; pp. 203-250. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Barco, J.A.; Rodríguez-Quintal, J.G.; Rodríguez, C.T.; Narciso-Fejure, S.E. Moluscos asociados al arrecife coralino de Isla Larga, Parque Nacional San Esteban, Estado Carabobo, Venezuela. Mem. Fund. La Salle Cien. Nat. Fundación 2019, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Brogan, M.W. Distribution and retention of larval fishes near reefs in the Gulf of California. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994, 115, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamner, W.M; Largier, J.L. Oceanography of the planktonic stages of aggregation spawning reef fishes. In Reef fish spawning aggregations: biology, research and management; Sadovy de Mitcheson, Y.; Colin, P.L., Eds.; Springer, Dordrecht, 2012; pp. 159-190. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, R.K.; Paris, C.B.; Srinivasan, A. Scaling of connectivity in marine populations. Sci. 2006, 311, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, C.D.; Bellwood, D.R. Disturbance and recolonisation by small reef fishes: the role of local movement versus recruitment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015, 537, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, M.J. Diel patterns of abundance of presettlement reef fishes and pelagic larvae on a coral reef. Mar. Biol. 2001, 138, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Coto, C.; Gutiérrez, R.M.; González-Félix, M.; Sanvicente-Añorve, L.; García, F.Z. Annual Variation of Ichthyoplancton Assemblages in Neritic Waters of the Southern Gulf of Mexico. Caribb. J. Sci. 2000, 36, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Leis, J.M.; McCormick, M.I. The biology, behavior and ecology of the pelagic, larval stage of coral-reef fishes. In Sale, P.F. (Ed.). Coral reef fishes: New insights into their ecology. Academic Press, San Diego, 2022; pp. 171-199. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rosenberg, S.P.A.; Saldierna-Martínez, R.J.; Aceves-Medina, G.; Cota–Gómez, V.M. (2007) Fish larvae in Bahía Sebastián Vizcaíno and the adjacent oceanic region, Baja California, México. Check. list. 2007, 3, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Chávez, C.A.; Beier, E.; Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Barton, E.D.; Godínez, V.M. Role of circulation scales and water mass distributions on larval fish habitats in the Eastern Tropical Pacific off Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2015, 120, 3987–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.; Hale, E.; Hilton, E.J.; Clardy, T.R. : Deary, A.L.; Targett, T.E.; Olney, J.E. Composition and temporal patterns of larval fish communities in Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, USA. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 2015, 527, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Zerrato, J.J.; Córdoba-Rojas, D.F.; Giraldo, A. Composición taxonómica de las larvas de peces en el arrecife coralino de La Azufrada, Pacífico colombiano, entre 2017 a 2019. Bol. Cient. Mus. Hist. 2023, 27, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, J.H.S. The effect of temperature on larval fishes. Neth. J. Zool. 1991, 42, 336–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Y.; Yaragina, N.; Kraus, G.; Marteinssdottir, G.; Wright, P.J. Using environmental and biological indices as proxies for egg and larval production of marine fish. J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 2003, 33, 115–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.I.; Cury, P.; Brander, K.; Jennings, S.; Möllmann, C.; Planque, B. Sensitivity of marine systems to climate and fishing: concepts, issues and management responses. J. Mar. Syst. 2010, 79, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamizar, N.; Blanco-Vives, B.; Migaud, H.; Davie, A.; Carboni, S.; Sanchez-Vazquez, F.J. Effects of light during early larval development of some aquacultured teleosts: A review. Aquac. 2011, 315, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.M. Larval fish assemblages near Indo-Pacific coral reefs. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1993, 53, 362–392. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, B.C.; Wellington, G.M. Endemism and the pelagic larval duration of reef fishes in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. 2000, 205, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.M. Pacific coral-reef fishes: the implications of behaviour and ecology of larvae for biodiversity and conservation, and a reassessment of the open population paradigm. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 2002, 65, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.; et al. Marine Biodiversity of Eastern Tropical Pacific Coral Reefs. In Coral Reefs of the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Coral Reefs of the World; Glynn, P.; Manzello, D.; Enochs, I., Eds., vol 8.; Springer, Dordrecht, 2017. Pp. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, G.J.; Banks, S.A.; Bessudo, S.; Cortés, J.; Guzmán, H.M.; Henderson, S.; Martinez, C.; Rivera, F.; Soler, G.; Ruiz, D.; Zapata, F.A. Variation in reef fish and invertebrate communities with level of protection from fishing across the Eastern Tropical Pacific seascape. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuc, A.; Quimbayo, J.P.; Alvarado, J.J.; Araya-Arce, T.; Arriaga, A.; Ayala-Bocos, A.; Julio Casas-Maldonado, J.; Chasqui, L.; Cortés, J.; Cupul-Magaña, A.; Olivier, D.; Olán-González, M.; González-Leiva, A.; López-Pérez, A.; Reyes-Bonilla, H.; Smith, F.; Rivera, F.; Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F.A.; Rodríguez-Villalobos, J.C.; Segovia, J.; Zapata, F.A.; Bejarano, S. Patterns of reef fish taxonomic and functional diversity in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Ecography. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, M.H.; Madrigal-Mora, S.; Espinoza, M. Drivers of reef fish assemblages in an upwelling region from the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 98, 1074–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, E.A.; Gutiérrez, B.; Franke, R. Peces de la isla de Gorgona. Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, 1987; pp. 323.

- Mora, C.; Ospina, A. Experimental effect of cold, la nina temperatures on the survival of reef fishes from Gorgona island (eastern Pacific Ocean). Mar. Biol. 2002, 141, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, A.F.; Mora, C. Effect of body size on reef fish tolerance to extreme low and high temperatures. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 2004, 70, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.M.; Zapata, F.A. Fish community structure on coral habitats with contrasting architecture in the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2014, 62, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.M.; Muñoz, C.G.; Zapata, F.A. Fish corallivory on a pocilloporid reef and experimental coral responses to predation. Coral Reefs. 2014, 33, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate, A.; Zapata, F.A.; Giraldo, A. A comparison of visual and collection-based methods for assessing community structure of coral reef fishes in the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2014, 62, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quimbayo, J.P.; Zapata, F.A. Cleaning interactions by gobies on a tropical eastern Pacific coral reef. J. Fish. Biol. 2018, 92, 1110–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle-Bonilla, I.C.; López, A.G.; Cuéllar-Chacón, A. Spaciotemporal variation in the coral fish larvae assembly of Gorgona Island, Colombian Pacific. Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost. 2017, 46, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Martínez, G.A.; Giraldo, A.; Rivera-Gómez, M.; Aceves-Medina, G. Daily and monthly ichthyoplankton assemblages of La Azufrada coral reef, Gorgona Island, Eastern Tropical Pacific. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; Zapata, L.A. Peces demersales del Parque Nacional Natural Gorgona y su área de influencia, Pacífico colombiano. Bio. Col. 2006, 7, 211–244. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, J.F. “The hydroclimatology of Gorgona Island: seasonal and ENSO–related patterns”. Act. Biol. 2009, 91, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, A.; Rodríguez-Rubio, E.; Zapata, F. Condiciones oceanográficas en isla Gorgona, Pacífico oriental tropical de Colombia. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. 2008, 36, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, A.; Díaz-Granados, M.C.; Gutiérrez-Landázuri, C.F. Isla Gorgona, enclave estratégico para los esfuerzos de conservación en el Pacífico Oriental Tropical. Rev. biol. Trop. 2014, 62, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, F.A.; Morales, Y.A. Spatial and temporal patterns of fish diversity in a coral reef at Gorgona Island, Colombia. In Proceedings of the 8th international Coral Reef symposium, Vol. 1.; Ciudad de, Panamá, Panamá; 1997; pp. 1029–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, F.A.; Vargas-Ángel, B. Corals and coral reefs of the Pacific coast of Colombia. En: Coral reefs of Latin America Elsevier Science; Cortes, J. Eds.; Amsterdam, Holanda, 2003; pp. 419-447. [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.W.; Von Prahl, H.; Guhl, F. Coral reefs of Gorgona Island, Colombia, with special reference to corallivores and their influence on community structure and reef development. An. Inst. Invest. Mar. Punta. BetõÂn. 1982, 12, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, B.; Lavaniegos, B.; Giraldo, A.; Rodríguez-Rubio, E. Temporal and spatial variation of hyperiid amphipod assemblages in response to hydrographic processes in the Panama Bight, eastern tropical Pacific. Deep-Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. 2013, 73, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Gómez, M.; Giraldo, A.; Lavaniegos, B. Structure of euphausiid assemblages in the Eastern Tropical Pacific off Colombia during El Niño, La Niña and neutral conditions. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2019, 516, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, B.; Giraldo, A. Structure of hyperiid amphipod assemblages on Isla Gorgona, eastern tropical Pacific off Colombia. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2012, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, A.; Valencia, B.; Acevedo, J.D.; Rivera, M. Fitoplancton y zooplancton en el área marina protegida de Isla Gorgona, Colombia, y su relación con variables oceanográficas en estaciones lluviosa y seca. Rev. biol. Trop. [CrossRef]

- Moser, H.G. The early stages of fishes in the California current region. California cooperative oceanic fisheries investigations, Atlas No. 33. Nat. Mar. Fish. Serv. SFSC. La Jolla, Calif. Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kans, 1996; 18. 9358. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-León, B.S.; Ríos, R. Estadios tempranos de peces del Pacífico colombiano. Instituto Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura INPA-Buenaventura, Colombia, 2000; pp. 727. 9: ISBN, 9589. [Google Scholar]

- Boeing, W.J.; Duffy-Anderson, J.T. Ichthyoplankton dynamics and biodiversity in the Gulf of Alaska: responses to environmental change. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, M.J.; Llorente, B.J. The use of species accumulation functions for the prediction of species richness. Conserv. Biol. 1993, 7, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation. 2nd Edition, PRIMER-E, Ltd. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, C. Monitoring river health initiative technical report number 36. 2003. www.deh.gov.au/index.html. 12/05/07.

- Escarria, E.; Beltrán, B.; Giraldo, A.; Zapata, F. Ichthyoplankton in the National Natural Park Isla Gorgona (Pacific Ocean of Colombia) during September 2005. Bol. Investig. Mar. 2007, 35, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.M.; Goldman, B. A preliminary distributional study of fish larvae near a ribbon coral reef in the Great Barrier Reef. Coral reefs. 1984, 2, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponaugle, S.; Fortuna, J.; Grorud, K.; Lee, T. Dynamics of larval fish assemblages over a shallow coral reef in the Florida Keys. Mar. Biol. 2003, 143, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.M. Are larvae of demersal fishes plankton or nekton? Adv. Mar. Biol. 2006, 51, 57–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamner, W.M.; Wolanski, E. Hydrodynamic forcing functions and biological processes on coral reefs: a status review. In Proc. 6th Int. Coral Reef Symp, 1988; Vol 1; pp. 103-113.

- Irisson, J.O.; LeVan, A.; De Lara, M.; Planes, S. Strategies and trajectories of coral reef fish larvae optimizing self-recruitment. J. Theor. Bio. 2004, 227, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, S.M.; Russ, G.R.; Abesamis, R.A. Pelagic larval duration and settlement size of a reef fish are spatially consistent, but post-settlement growth varies at the reef scale. Coral Reefs. 2015, 34, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.M. The pelagic stage of reef fishes: the larval biology of coral reef fishes. In: The ecology of fishes on coral reefs; Sale, P.F.; Eds; University of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1991; pp. 183-230. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.R. The role of adult biology in the timing of spawning of tropical reef fishes. En: The Ecology of Fishes on Coral Reefs; Sale, P.F; Eds.; Academic Press, San Diego, USA, 1991; pp. 356–386. [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.T.; Hsieh, H.Y.; Wu, L.J.; Jian, H.B.; Liu, D.C.; Su, W.C. Comparison of larval fish assemblages between during and after northeasterly monsoon in the waters around Taiwan, western North Pacific. J. Plankton. Res. 2010, 32, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Beier, E.; Godínez, V.M.; Barton, E.D.; Santamaría-del-Angel, E.; Jiménez-Rosemberg, S.P.A.; Marinone, S.G. Hydrographic and fish larvae distribution during the “Godzilla El Niño 2015–2016” in the northern end of the shallow oxygen minimum zone of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2017, 122, 2156–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Gordo, C.; Godínez-Domínguez, E.; Suárez-Morales, E. Larval fish assemblages in waters off the central Pacific coast of Mexico. J. Plankton. Res. 2002, 24, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funes-Rodríguez; R. ; Flores-Coto, C.; Esquivel-Herrera, A.; Fernández-Alamo, M.A.; Gracia-Gásca, A. Larval fish community structure along the west coast of Baja California during and after the El Niño event (1983). Bull. Mar. Sci. 2002, 70, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aceves-Medina, G.; Jiménez-Rosenberg, S.P.A.; Hinojosa-Medina, A.; Funes-Rodríguez, R.; Saldierna, R.J.; Lluch-Belda, D. . Watson, W. Fish larvae from the Gulf of California. Sci. Mar. 2003, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Medina, G.; Saldierna-Martínez, R.J.; Hinojosa-Medina, A.; Jiménez-Rosenberg, S.P.; Hernández-Rivas, M.E.; Morales-Ávila, R. Vertical structure of larval fish assemblages during diel cycles in summer and winter in the southern part of Bahía de La Paz, México. Estuar. Coas. Shelf. Sci. 2008, 76, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.Y.; Lo, W.T.; Chen, H.H.; Meng, P.J. Larval fish assemblages and hydrographic characteristics in the coastal waters of southwestern Taiwan during non-and post-typhoon summers. Zool. Stud. 2016, 55, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarakis, S.; Drakopoulos, P.; Filippou, V. Distribution and abundance of larval fish in the northern Aegean Sea—eastern Mediterranean—in relation to early summer oceanographic conditions. J. Plankton. Res. 2002, 24, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunda-Arara, B.; Mwaluma, J.M.; Locham, G.A.; Øresland, V.; Osore, M.K. Temporal variability in fish larval supply to Malindi Marine Park, coastal Kenya. Aquat. Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2009, 19, S10–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponaugle, S.; Llopiz, J.K.; Havel, L.N.; Rankin, T.L. Spatial variation in larval growth and gut fullness in a coral reef fish. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 383, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.M. Ontogeny of behaviour in larvae of marine demersal fishes. Ichthyol. Res. 2010, 7, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, R.K.; Castro, L.R. Relation of coral reef fish larval distributions to island scale circulation around Barbados, West Indies. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1994, 54, 228–244. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, C.S.; Panteleev, G.; Taggart, C.T.; Sheng, J.; DeYoung, B. Observations on larval fish transport and retention on the Scotian Shelf in relation to geostrophic circulation. Fish. Oceanogr. 2000, 9, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Slawinski, D.; Beckley, L.E.; Keesing, J.K. Retention and dispersal of shelf waters influenced by interactions of ocean boundary current and coastal geography. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2010, 61, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Beier, E.; Avalos-García, C.; Lavín, M.F. Larval fish assemblages and geostrophic circulation in Bahía de La Paz and the surrounding southwestern region of the Gulf of California. J. Plankton. Res. 2006, 28, 1081–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivar, M.P.; Emelianov, M.; Villate, F.; Uriarte, I.; Maynou, F.; Alvarez, I.; Morote, E. The role of oceanographic conditions and plankton availability in larval fish assemblages off the Catalan coast (NW Mediterranean). Fish. Oceanogr. 2010, 19, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.W. Comparison of the measurement and effects of habitat structure on gastropods in rocky intertidal and mangrove habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998, 169, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, F.; Folke, C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerken, I.; Dorenbosch, M.; Verberk, W.C.E.P.; De La Morinière, E.C.; van Der Velde, G. Importance of shallow-water biotopes of a Caribbean Bay for juvenile coral reef fishes: patterns in biotope association, community structure and spatial distribution. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2000, 202, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellwood, D.R.; Wainwright, P.C. (2002) The history and biogeography of fishes on coral reefs. In: Coral reef fishes: dynamics and diversity in a complex ecosystem: Sale, P.F., Eds.; Academic Press, 2002; pp. 5-32. [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.J.; Broad, K.; Brumbaugh, D.R.; Dahlgren, C.P.; Harborne, A.R.; Hastings, A. . Sanchirico, J.N. Coral reef habitats as surrogates of species, ecological functions, and ecosystem services. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, R.; Lowe-McConnell, R.H. Ecological studies in tropical fish communities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987; pp. 382. [CrossRef]

- Johannes, R.E. Traditional marine conservation methods in Oceania and their demise. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1978, 9, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, J.; Porri, F.; Starczak, V.; Blythe, J. Causes of decoupling between larval supply and settlement and consequences for understanding recruitment and population connectivity. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2010, 392, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, V.; Holzman, R. Hydrodynamic starvation in first-feeding larval fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 8083–8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Taxa reported | New records | Accumulated taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escarria et al. [57] | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Calle-Bonilla et al [38] | 29 | 29 | 64 |

| Ramírez et al. [39] | 87 | 57 | 121 |

| This work | 88 | 41 | 462 |

| Periods | Richness (d) | Diversity H' (nats/ind) |

|---|---|---|

| March_2017 | 1.64 | 2.25 |

| September_2017 | 1.80 | 2.90 |

| March_2018 | 2.23 | 4.38 |

| September_2018 | 1.71 | 2.99 |

| March_2019 | 1.98 | 2.34 |

| September_2019 | 2.59 | 4.20 |

| Groups | Statistic R | Significance level P (%) |

|---|---|---|

| M-2019, S-2019 | 0.752 | 0.1 |

| M-2019, M-2018 | 0.921 | 0.1 |

| M-2019, S-2018 | 0.859 | 0.1 |

| M-2019, M-2017 | 0.903 | 0.1 |

| M-2019, S-2017 | 0.791 | 0.1 |

| S-2019, M-2018 | 0.837 | 0.1 |

| S-2019, S-2018 | 0.682 | 0.1 |

| S-2019, M-2017 | 0.962 | 0.1 |

| S-2019, S-2017 | 0.601 | 0.1 |

| M-2018, S-2018 | 0.757 | 0.1 |

| M-2018, M-2017 | 0.287 | 0.1 |

| M-2018, S-2017 | 0.849 | 0.1 |

| S-2018, M-2017 | 0.856 | 0.1 |

| S-2018, S-2017 | 0.576 | 0.1 |

| M-2017, S-2017 | 0.896 | 0.1 |

| Parameters | Statistics | M-2017 | S-2017 | M-2018 | S-2018 | M-2019 | S-2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | µ | 28.4 | 28.8 | 27.4 | 27.7 | 25.8 | 27.5 |

| S.D. | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.13 | |

| Min | 28.3 | 28.7 | 27.2 | 27.5 | 25.4 | 27.4 | |

| Max | 28.7 | 29.1 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 26.2 | 27.8 | |

| S (PSU) | µ | 29.6 | 25.2 | 26.7 | 26.1 | 30.7 | 30.3 |

| S.D. | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 1.14 | 0.44 | 0.13 | |

| Min | 29.6 | 24.2 | 26.5 | 23.1 | 30.1 | 30.0 | |

| Max | 29.7 | 25.7 | 27.0 | 26.7 | 31.4 | 30.4 | |

| OD (ml/L) | µ | 5.6 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 4.9 | 8.9 | 6.7 |

| S.D. | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.46 | 0.24 | 0.63 | |

| Min | 5.2 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 8.6 | 6.0 | |

| Max | 5.8 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 9.3 | 7.9 |

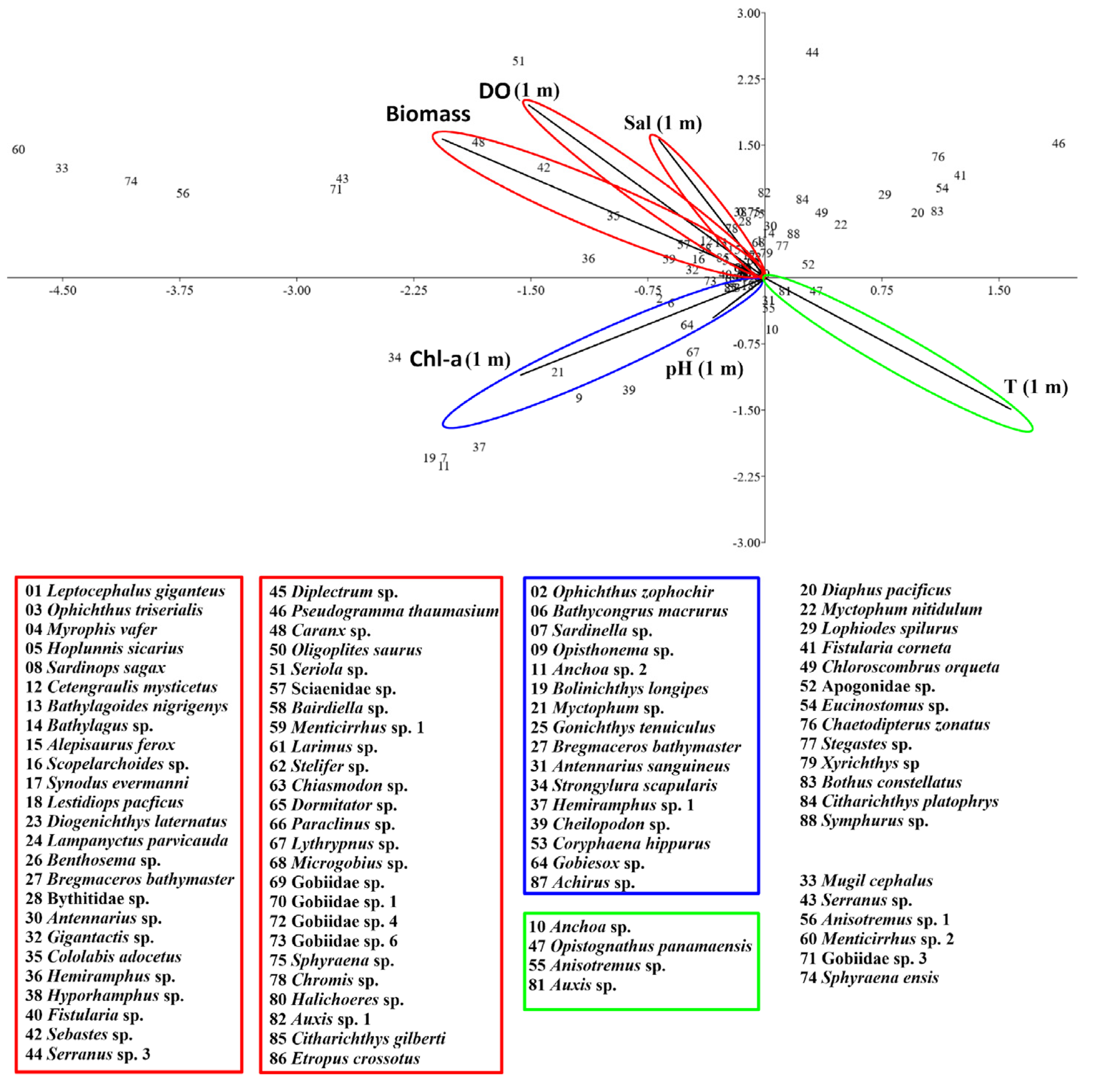

| Axis 1 | Axis 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Variance explained | 36.27 | 31.42 |

| T (1 m) | 0.45 | -0.42 |

| UPS (1 m) | -0.19 | 0.44 |

| DO (1 m) | -0.43 | 0.56 |

| pH-1 m | -0.10 | -0.13 |

| Chl-a (1 m) | -0.45 | -0.32 |

| Biomass | -0.59 | 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).