1. Introduction

Coral reefs are highly diverse marine ecosystems that provide foraging and refuge habitats to a very dense and diverse array of marine species and are thus often regarded as the “rainforests of the sea” [

1]. Reefs can protect the shoreline from storms, waves, and fluctuating currents, and serve as a breeding and feeding ground for an estimated 1 million species [

1]. Moreover, reefs are also a source of livelihood for local fishing communities [

2]. For instance, Miththapala [

3] estimated that an average of 15 tons of fish and other seafood per km

2 can be harvested if the resource is well-managed.

Direct localized threats have altered coral reef community structures and marine ecosystem function, while indirect global stressors associated with environmental changes continue to become increasingly more severe [

1]. The health and distribution of reef-building corals are influenced by environmental conditions such as climate, biochemistry, and fishing pressure [

4]. In Cambodia, illegal fishing poses one of the most immediate threats to coral reefs. Consequently, conservation efforts have largely focused on assessing the status of threatened reef systems and delivering fisheries management tools to protect wider ecosystem networks [

5,

6,

7]. However, to protect marine biodiversity and promote sustainable resource use, the creation of Marine Fisheries Management Areas (MFMA) and its thorough management are key for the sustainable use of the marine resources and long-term conservation of high biodiversity areas, such as coral reefs or habitats containing endemic species[

2]. These management, including the enforcement of its regulations and approaches, are also important to provide education and training to communities on the importance of conserving marine biodiversity and fisheries [

8]. Since these initial MFMA designations, Cambodia has continued to promote marine conservation and management through collaboration between the government, NGOs, and communities.

However, the impacts of local environmental conditions on reef systems in Cambodia have not been afforded the same research attention. By understanding the effects of physical and chemical parameters on coral community structure, the local drivers other than existing anthropogenic threats including fishing and coastal development, which mainly influence the health and distribution of corals, can be better identified. Furthermore, by identifying relationships between coral and environmental variables, one can gain an initial insight into how coral reefs in Cambodia will respond to future conditions under the environmental change phenomena. Here, in the Koh Seh reef system, located in shallow water in the coastal zone in Cambodia, we i) investigated coral reef diversity and community structure, i.e. richness, abundance, and Shannon diversity index, in different areas around the island, ii) determined the health status of the coral community, and iii) identified the key environmental drivers responsible for the observed diversity and community structure on the Koh Seh reef.

2. Materials and Methods

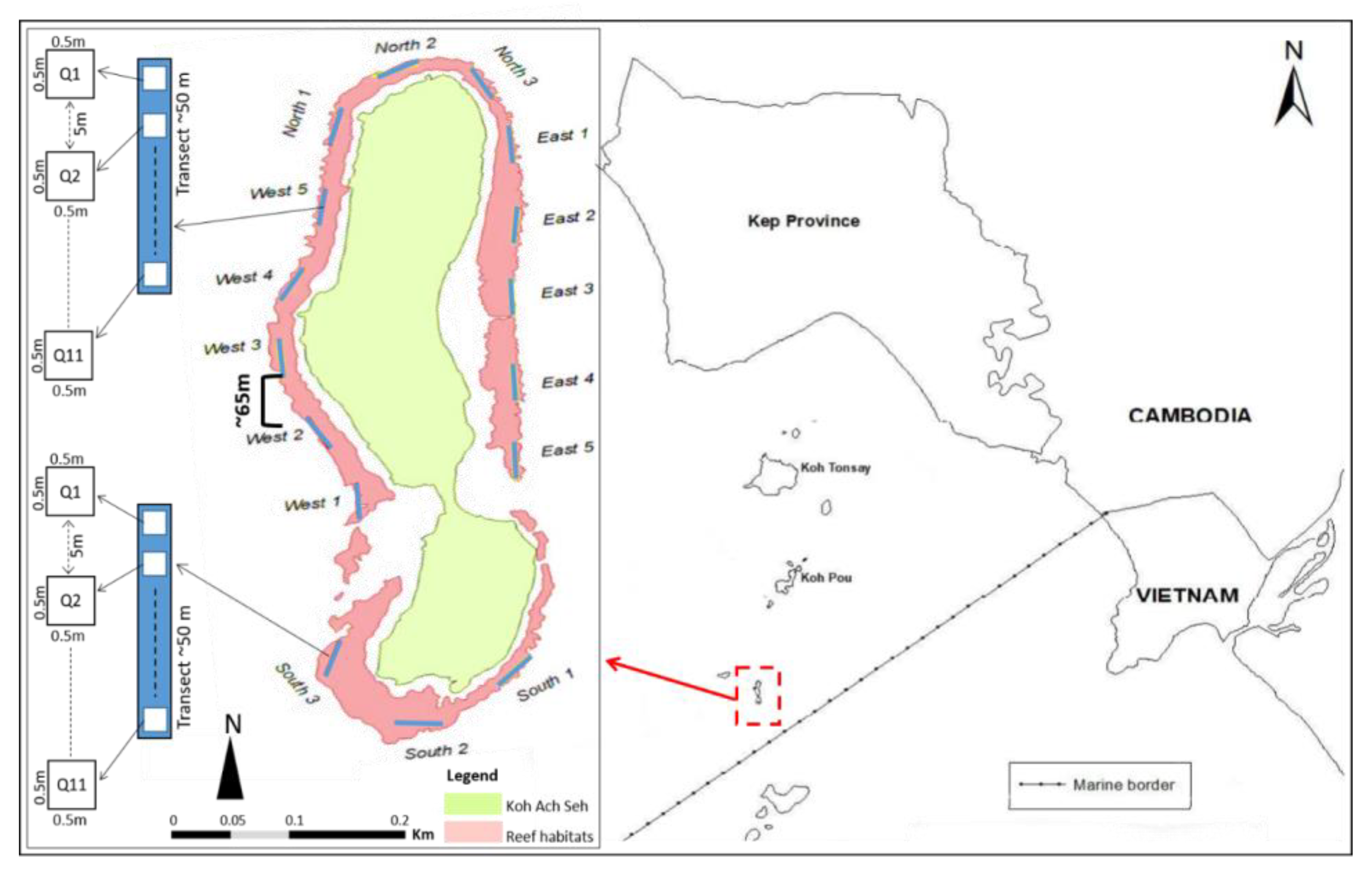

This study was conducted on the Koh Seh reef in Cambodia’s Kep archipelago (

Figure 1). Koh Seh reef is one of the many reefs that fringe around a small island in the archipelago, which is a part of a cluster of reefs surrounding the archipelago’s islands. In addition, Koh Seh reef is a protected area of the Kep MFMA that was established in 2018. Before the undertaking of fieldwork, a desktop study was undertaken to map the extent of the Koh Seh reef. Following this, the sampling area was divided into four sections based on the presence of coral communities. These include sites at the northern, southern, eastern and western sections of the reef (

Figure 1).

2.1. Sampling Design and Data Collection

2.1.1. Substrate and Coral Cover

Data was collected between 25

th June to 25

th September 2019. A total of 16 sampling sites were established around the island, which included five sites each for the west and east sections, and three sites each for the north and south (

Figure 1). The number of sites surveyed chosen within each part was proportional to the extent of the total reef habitat of the island. At each of the sampling sites, surveys were undertaken along 50 m transect lines at depths between 1 and 2.5 m (median depth range), based on the reef structure growing as shallow water in Kep archipelago it between 1 to 3 m depth and in proximately 65-m breaks were established between transect lines. Note that breaks between transect lines were larger in areas that exhibited sandy bottom habitat, notably in the southern section (

Figure 1). SCUBA divers placed quadrats (50 cm

2) at five-meter intervals (beginning at zero) along each transect. Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates were collected at each quadrat site.

At each quadrat site photographic data was collected using an Olympus Tough TG-5 waterproof camera. The imagery was used to aid in the identification of coral species to the genus level. The imagery was also used to analyze percent benthic reef cover and ecological health (measured as The percentage of dead, bleached, and/or diseased coral compared to healthy coral), which was undertaken using the software CPCe (Coral Point Count with Excel extensions [

9] .Benthic reef components were assigned to the following substrate categories: hard coral, soft coral, sponge, rock, sand, zoanthid, macro-algae, and crustose coralline algae. Using CPCe to analyze benthic reef cover and coral reef health, we randomly applied fifty points to each image and assigned each one a substrate type and health status based on substrate type the point landed on.

2.1.2. Physical-Chemical Variables and Sedimentation Rate Calculation

Water quality sampling (dissolved oxygen, pH, and salinity) was undertaken at the starting point (i.e., at zero metres) and at the end point of each transect line and replicate. An Automatic Temperature Compensation (ATC) meter, with additional instrumentation fitted (including a HI 9146 Microprocessor) was used to measure temperature, pH, salinity, and dissolved oxygen (DO). Depth of coral reef habitat was also measured at each transect line using a Mares Matrix dive computer.

To assess sedimentation rate, sediment traps were deployed at one end of each survey transect. Sediment traps were made from white plastic bottles and sediment trap blocks, measuring 15 × 6.5 cm with a mouth diameter of 5 cm. Each trap weighed 9 kg, which was identified as an appropriate weight for remaining stable on the sea floor through a pilot trial. Sediment traps were left in the water for one week before being sealed underwater (to prevent loss of sediment from traps) and then recovered. On land, sediment was removed from traps, placed into separate jars and sent to the laboratory at the Royal University of Phnom Penh. At the lab, sediment from each jar was filtered through size 97 g/m2 filter paper and then dried at a temperature of 25 oC for three days. The dry weight (in grams) of each sample was then measured.

2.1.3. Data Analysis

Survey data was analyzed to determine percent substrate cover and composition of coral genera. Ward’s hierarchical clustering method was then used to group coral community data from all 16 sites into clusters (i.e. zones) by applying the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity distance matrix [

10] using the “vegan” package of R [

11]. Before performing this cluster analysis, a Hellinger transformation was undertaken to normalize the coral data and reduce effects of outliers. The result of this analysis can demonstrate which parts of the island are similar or distinct based on the coral communities. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for significant differences in coral richness, abundance, and diversity between clusters/zones. Diversity was measured using the Shannon diversity index (Diversity H).

Multi-level pattern analysis was applied to identify species indicators within each cluster/zone [

12]. We used the Indicator Value (IndVal) developed by Dufrene and Legendre [1997] in the R package “labdsv” (Roberts, 2013) to identify indicator taxa for coral communities within the defined clusters. A taxon's Indicator Value is a 0-1 index showing its importance in a group of sites, with 0 being least and 1 being most important. A value of 1 results if the taxon is present only in the group and when it occurs in all sites of that group. The high number of taxa showing significant indicator values suggests their preferred habitat. We selected the most significant taxa for each cluster by retaining only those with high indicator values and a p < 0.05.

A non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) was used to visualize coral communities in a two-dimension plot to illustrate differences in community composition and their associations with environmental factors. Data was analyzed using R statistical program [

13] . In all cases the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Substrate Covers and Coral Community Organization

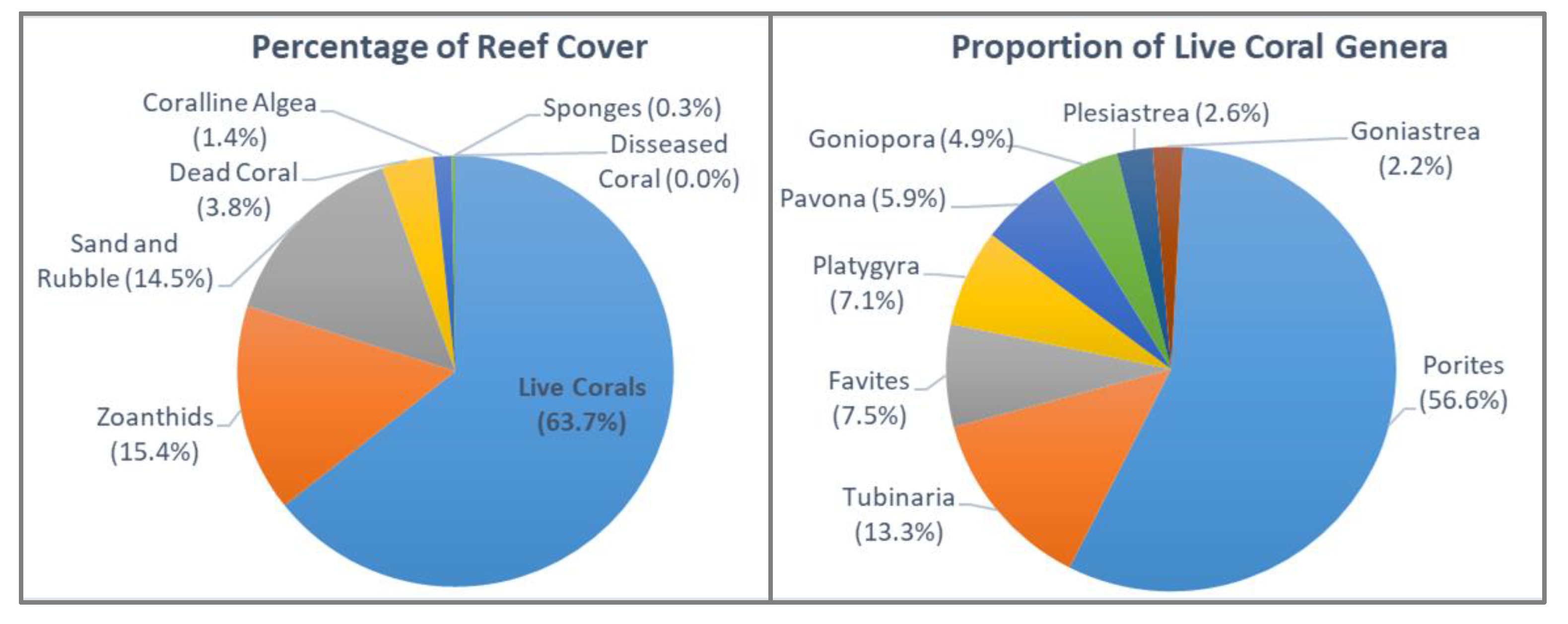

Average substrates cover on the Koh Seh reef was dominated by live hard coral (64%), followed by Zoanthids (15%) and sand/rubble (15%). Other substrate types exhibited relatively low levels of cover in comparison and are presented in

Figure 2.

In total there were 409 hard live coral colonies recorded, belonging to 14 genera and 9 families (Scleractinia). Only one soft coral colony (Octocorallia) was observed, and the species was not able to be determined. Of the 14 hard coral genera, Porites was the most common genus across the reef system (56.6% of all corals), followed by Tubinaria (13.3%). Acropora was the least prevalent genus, comprising <1%. Diversity of coral genera along transect lines ranged from 4 to 10 genera, 12 to 40 colonies, and 0.1 to 1.9 on the Diversity H. Most hard coral growth forms were massive, which included species form the following genera: Porites, Favites, Favia, Goniastrea, Platygyra, and Goniopora.

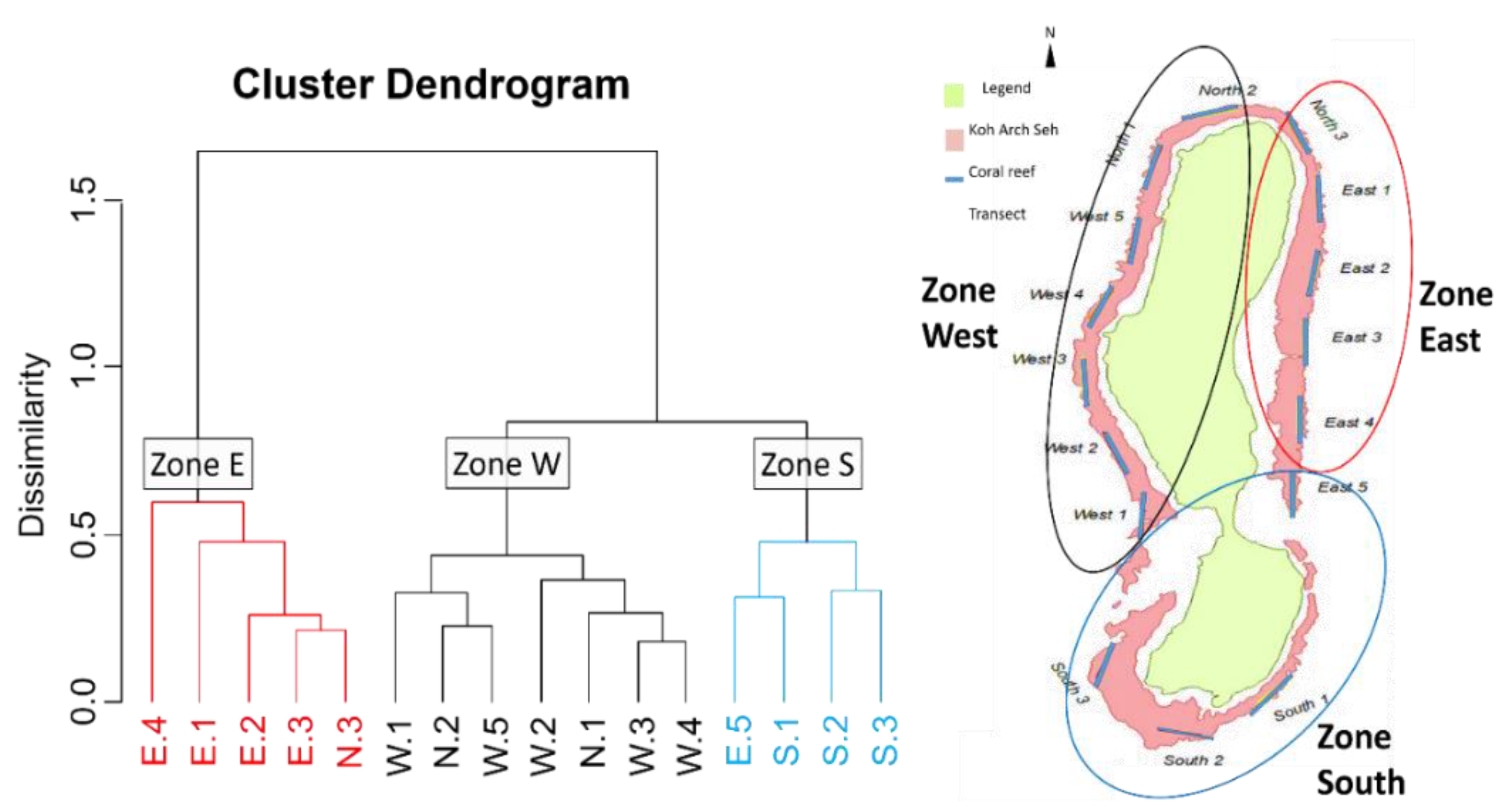

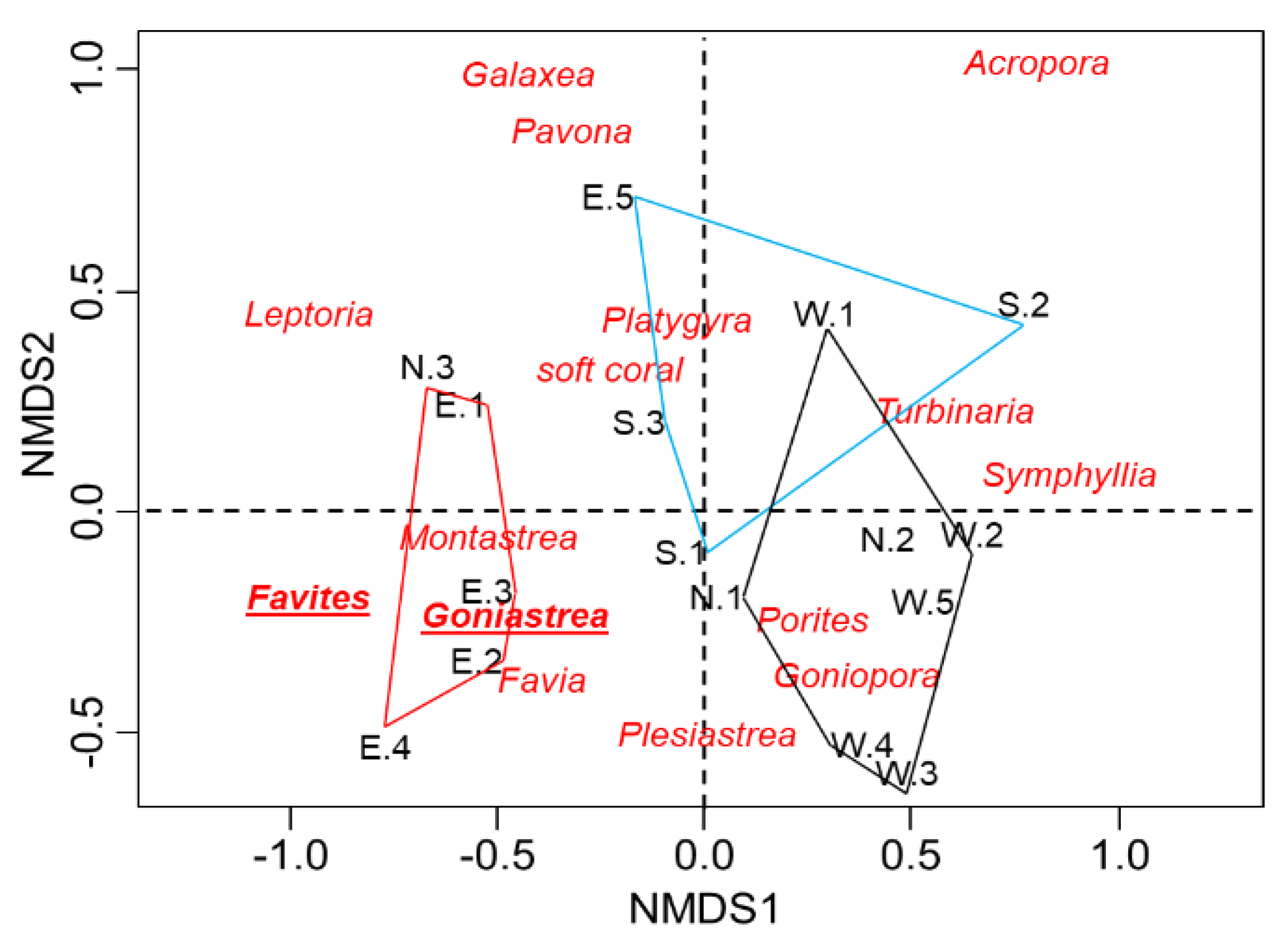

Based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and the hierarchical analysis of the live hard corals, the sixteen sites were grouped into three clusters, referred to as zones (

Figure 3). The clusters represent the organization of coral communities in zones East, South, and West. Zone East consisted of four sites located in the east part and one site in the northeast part of the island. Zone South is made up of three sites in the south and one site in the eastern parts of the island, whereas zone West is made up of five sites located in the western part and two sites in the northern part of the island (

Figure 3). The NMDS ordination plot also shows three distinct coral communities around the island of Koh Ach Seh. Coral communities within the East Zone are less similar to those within the South and West Zones (

Figure 4).

Based on the Kruskal-Wallis analysis, coral community composition was not found to be significantly different based on richness, abundance and diversity H, and nor the reef covers among the three zones (

Table 1). However, we found them different in terms of indicator taxa.

Favites was the indicator taxa identified within the East zone (IndVal = 0.98,

p = 0.005),

Goniastrea was identified as the indicator for both the South and East zones (IndVal = 0.09,

p = 0.015) (

Figure 3). There was no indicator found for the West zone.

3.2. Health Status and Environmental Characterization of Coral Communities

Among the reef covers, live corals comprised 64%, with an average of 51%, 63% and 73% for zones East, West and South, respectively (

Table 1). Only 4% of the corals were found dead, with an average of 6%, 3% and 3% for zones East, West and South, respectively, and no diseased corals were detected. The percentage of dead coral was not significantly different between the three zones (

Table 1).

We found that most of the environmental variables, except for salinity, showed significant differences among the three zones. DO and water depth had a highly significant difference (

p < 0.001), while the others like Sediment load, Temperature and pH were significant different at

p < 0.05. Detailed information on the environmental variables characterizing each reef zone is provided in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reef Cover and Coral Community Organization

Cambodia’s coral reefs community is dominated by hard corals, and their composition can be significantly varied among islands and soft coral occurrence is less abundance. There may be some underlying factors rendering the inshore reef inhospitable for soft coral, which requires more investigation [

14]. Our finding that the highest percentage of live hard corals cover with soft corals comprises a small proportion is also in line with the results of the survey taken place in the Koh Rong archipelago between 2010 and 2014 [

6] and in the Koh Sdach archipelago in 2014 [

14]. In addition, Cambodia’s coral reefs appear to be dominated by

Porites spp. In Koh Seh and Koh Rong,

Porites spp. respectively comprised 36% and 56% of all hard corals [

15], while they comprise 21% of Koh Sdach [

14]. Similar research in Karimunjawa islands, Indonesia also found the massive growth forms of

Porites spp [

16].

Here we found that coral cover and community composition, by means of richness, abundance, and diversity H, were not significantly different from one to another part of Koh Seh (or so-called zone in this study). This can happen especially when the island is small and has less variations in physical-chemical characteristics, and when the island has historically been colonized by the observed coral species. The research found that coral communities are relatively similar across the same reef in Koh Rong and Koh Sdach Archipelagos [

17]. The shallow water of Koh Seh supports distinct organization of coral community composition among the three zones of the island, especially zone East was represented by two indicators, namely

Favites and

Goniastrea, and by one indicator (also

Goniastrea) for zone South. Regarding the

Goniastrea spp. and

Favites spp, they represented in shallow water with high sediment rate [

3], which is similar to our finding in the present study.

4.2. Health Status and Environmental Characterization of Coral Communities

In this research, we found that there are low percentages of disease, bleaching and dead coral during data collection. Based on these indicators (disease, bleaching, dead coral cover), coral reefs in the Koh Seh archipelago appear to be relatively healthy. Most hard corals are massive in growth form and are the most resistant group in the southeast Asia ocean where tropical ocean can shape reef structure [

4].

Other research from neighboring islands such as Koh Rong and Koh Sdach archipelagos found that most of hard corals are also massive form [

14] and also similar to the findings of the present study (

Table 3). This can also reflect the effectiveness of marine protected areas, and therefore coral reef around Koh Seh archipelago should be under further regular monitoring, e.g. every year by the Marine Conservation Cambodia (an NGO) and the Marine Fisheries department of the Ministry of Agriculture in Cambodia. Corals in the zone East of Koh Seh may get degraded as they frequently receive stress from human activities such as frequent illegal fishing activities, transportation, and thus, more precaution should be given to this zone as well.

Environmental factors usually affect coral community composition. These factors can be anthropogenic disturbances, temperature, pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen, depth, and sediment [

16,

18]. For instance, an experimented study on three coral species including

Pocillopora damicornis,

Acropora millepora and

Platygyra sinensis found that the growth, survival, and photosynthesis of these corals were impacted by temperature, visibility and salinity [

19]. Another experiment on coral

Acropora yongei indicated that the species is sensitive to bleaching when the level of dissolved oxygen is reduced [

18]. The experiment on coral

Acropora yongei by reducing oxygen level showed coral

Acropora yongei is sensitive to bleaching when dissolved oxygen is low [

18].

In our study, a significant difference in environment variables such as dissolved oxygen, temperature, pH, water depth and sediment load was found among the three zones. Higher values of these variables were mainly found for shallow water (zone East), and lower values were in zone South (

Table 2). The depth of water from the surface is closely related to physical and chemical conditions [

20], and thus the sediment loads, especially in the shallow water in zone East of Koh Seh, as well as other islands in a neighboring country like Thailand [

21]. This is due to the water currents and the fishing activities underground such as bottom trawling, coastal development that causes hign turbidity and sediment load. Sediments have been found to influence coral communities, as found in our study and as well as others [

21]. For instance, our study and Cruz et al. [

22] found that

Goniastrea spp and

Favites spp occur in high sedimentation loads and in shallow water of Thailand and Puerto Rico Island [

23]. This is also the case in our study that a significantly high sediment load was found in zone East where

Goniastrea spp and

Favites spp dominated. According to these results, sedimentation appears to be one of the most important factors influencing coral communities. Most of the corals that are massive growth forms, such as

Porites spp,

Favites spp and

Favia spp,

Goniastrea spp, are more stress-tolerant than branching corals, e.g.

Acropora spp and

Tubastrea micrantha [

21]. Due to these factors, the

Favites and

Goniastrea are the indicator of their communities in zone East and appear to be more stress-tolerant than other coral taxa.

To warrant our finding on the coral health, composition and the effects of the environmental factors, additional survey and sampling sites have to be considered as they can increase accuracy and reliability of coral health and their community assessments [

24,

25]. Small sample size can only provide an area-specific coverage generalization, as is the case of the present study, because coral reefs are highly heterogeneous and inter-annual varied, which requires large coverage or inter-islands investigation to reveal real trend of community patterns, including the detection of rare species and events (e.g. disease outbreaks or recruitment of juvenile) and ecological health status [

25]

5. Conclusions

This study is the first detailed investigation of coral reefs and diversity in Koh Seh of the Kep Archipelagos. We found that live hard corals are the dominant component of the benthic reef covers, followed by Zoanthids and sand and rubble. All hard corals around Koh Seh can be grouped into three zones: East, West and South zones. Although no significant difference was detected in coral communities between these zones, we found that Favites spp. and Goniastrea spp. were the indicators of coral communities for the two zones, East and South. Moreover, coral communities in the three zones were characterized by key environmental variables such as dissolved oxygen, water temperature, pH, and sediment load because the values of these variables were significantly higher in zone East. The high sediment loads in zone East can be due to the current water activities and anthropogenic disturbances such as fishing and transportation. Nevertheless, we found a small proportion of dead and diseased coral colonies around the island. This may suggest that the protection effort co-enforced by the Marine Conservation Cambodia and the Marine Fisheries department of the Ministry of Agriculture in Cambodia is rather effective. Taken as a whole, our study is a useful baseline for further study of benthic reefs and coral communities in the whole Kep Archipelagos and surrounding areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.O.I, R.S.; Methodology: S.O.I, R.S., A.H.; Data collection: S.O.I, A.H.; Formal analysis and investigation: S.O.I, R.S.; Writing - original draft preparation: S.O.I, R.S.; Writing - review and editing: All; Funding acquisition: A.H.; Supervision: R.S., A.H.; Visualization: S.O.I, R.S.

Funding

This research was funded by Marine Conservation of Cambodia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

NA.

Informed Consent Statement

NA.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained by official request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. L. Reaka-Kudla, “The global biodiversity of coral reefs: a comprison with rain forests,” vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 295–316, 1997.

- F. Moberg and C. Folke, “Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems,” ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS, vol. 29, pp. 215–233, 1999.

- Sriyanie Miththapala, “Coral Reefs. Coastal Ecosystems Series (Vol1)pp 1-36 +iii. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ecosystems and Livelihood group Asia, IUCN.,” 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Ellis et al., “Multiple stressor effects on coral reef ecosystems,” Glob Chang Biol, vol. 25, no. 12, pp. 4131–4146, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Reid, A. Haissoune, and P. Ferbeer, “Koh Seh Environmental Assessment: Marine Conservation Cambodia (MCC).,” 2017.

- V. Thorne, B. Mulligan, R. M. Aoidh, and K. Longhourst, “Current status of coral reef health around the Koh Rong Archipelago, Cambodia,” Cambodian Journal of Natural History, vol. 1, pp. 98–113, 2015.

- J.-W. vanMelissa M. N. I. R. Bochove, “Cambodian Journal of Natural History,” vol. 2011, no. 2, pp. 114–121, 2011.

- M. Hamilton, “Perceptions of fishermen towards marine protected areas in Cambodia and the Philippines,” Bioscience Horizons, vol. 5, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Kohler and S. M. Gill, “Coral Point Count with Excel extensions (CPCe): A Visual Basic program for the determination of coral and substrate coverage using random point count methodology,” Comput Geosci, vol. 32, no. 9, pp. 1259–1269, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Legendre and Legendre, Numerical Ecology-Developments in Environmental Modelling, 3rd ed. Elsevier Science BV, Amsterdam. 2012.

- J. Oksanen, “Vegan: an introduction to ordination.”.

- Borcard et al., “Borcard, D., Gillet, F., Legendre, P., 2011. Numerical Ecology with R. Springer Science & Business Media, New York.,” p. 2011, 2011.

- R Core Team, “A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Rainboth, W.J., 1996. Species identification field guide for fishery purposes. Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. FAO, Rome.,” p. 2013, 2013.

- J. M. Savage, P. E. Osborne, M. D. Hudson, M. P. Knapp, and L. Budello, “A current status assessment of the coral reefs in the Koh Sdach Archipelago, Cambodia,” Cambodian Journal of Natural History, vol. 2014, no. 1, pp. 47–54, 2014.

- van Bochove J.W., McVee M., Ioannou N., Raines P., “C AMBODIA R EEF C ONSERVATION P ROJECT Year 1 Report February 2010 – February 2011,” no. February 2010, 2011.

- E. N. Edinger and M. J. Risk, “Reef classification by coral morphology predicts coral reef conservation value,” ELSEVIER, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Jan-Willem Van Bochove et al., “Cambodian Journal of Natural History,” Evaluating the statue of Cambodia’s coral reefs through baseline surveys and scientific monitoring, vol. 2011, no. 2, pp. 214–221, 2011.

- A. F. Haas, D. D. Deheyn, and J. E. Smith, “Effects of reduced dissolved oxygen concentrations on physiology and fluorescence of hermatypic corals and benthic algae,” PeerJ, vol. 2014, no. 1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Kuanui, S. Chavanich, V. Viyakarn, M. Omori, and C. Lin, “Effects of temperature and salinity on survival rate of cultured corals and photosynthetic efficiency of zooxanthellae in coral tissues,” Ocean Science Journal, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 263–268, 2015. [CrossRef]

- O. Guadayol, N. J. Silbiger, M. J.Donahue, and F. I. M. Thomas, “Patterns in temporal variability of temperature, oxygen and pH along an environmental gradient in a coral reef,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Caroline S. Rogers, “Responses of coral reefs and reef organisms to sedimentation,” Mar Ecol Prog Ser, vol. 62, pp. 185–202, 1990. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Cruz, V. H. Meira, R. K. P. de Kikuchi, and J. C. Creed, “The role of competition in the phase shift to dominance of the zoanthid Palythoa cf. variabilis on coral reefs,” Mar Environ Res, vol. 115, no. February, pp. 28–35, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. N. Anthony, D. I. Kline, G. Diaz-Pulido, S. Dove, and O. Hoegh-Guldberg, “Ocean acidification causes bleaching and productivity loss in coral reef builders,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 105, no. 45, pp. 17442–17446, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Cowling, A. “Spatial Methods for Line Transect Surveys,” 1998. [Online]. Available: http://about.jstor.org/terms.

- Y. M. Bozec, S. O’Farrell, J. H. Bruggemann, B. E. Luckhurst, and P. J. Mumby, “Tradeoffs between fisheries harvest and the resilience of coral reefs,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 113, no. 16, pp. 4536–4541, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).