1. Introduction

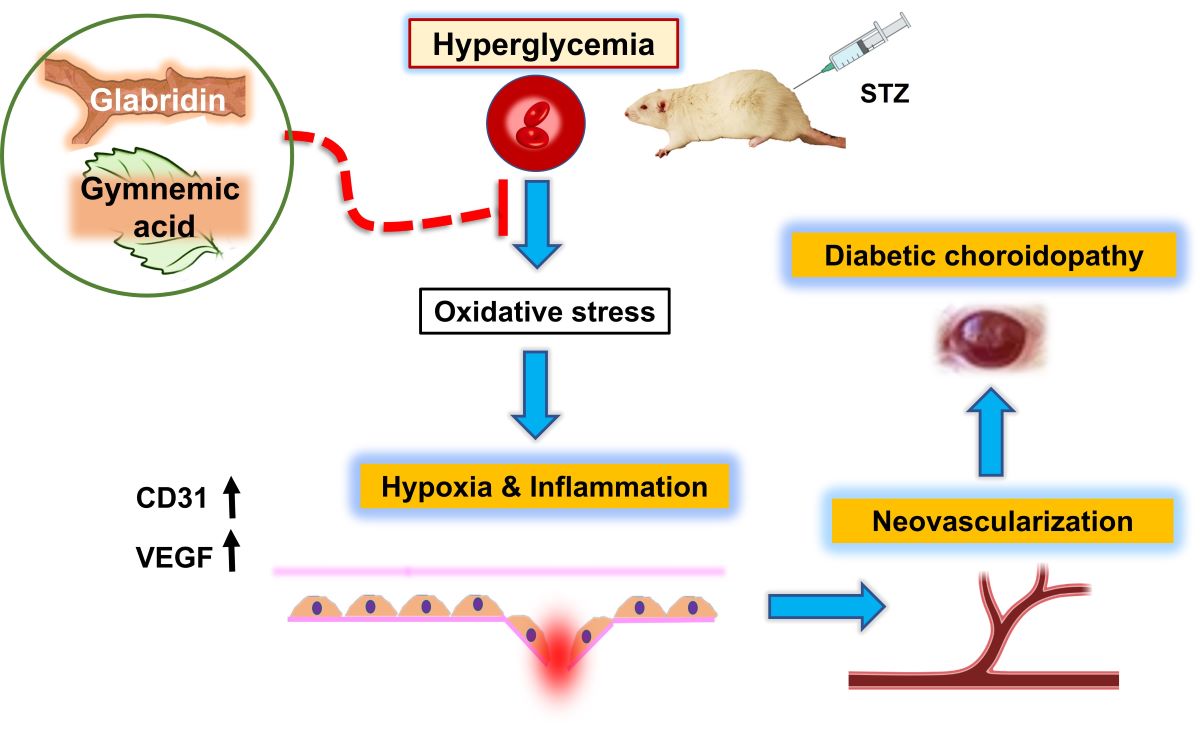

Diabetes issues can eventually result in blindness and give rise to the serious condition known as diabetic retinopathy (DR). High blood sugar makes the vascular wall less effective because it kills intramuscular pericytes and makes the basement membrane thicker. This happens while microvascular retinal changes happen. The small blood vessels in the eyes are particularly vulnerable to poor blood glucose control, which can cause damage. Studies on humans and animals have mostly examined the retinal vasculature rather than the choroid vasculature since diabetic retinopathy is typically a serious clinical issue.

The choroid, which is located outside the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and supplies the outer retina with nutrients, normally supplies the inner retina through the retinal vasculature. Therefore, it is possible that the thickness of the choroid may indirectly reflect the metabolic condition of the retina and the circulation of the choroidal blood. Several retinal illnesses, including glaucoma, have been linked to abnormalities in the thickness of the choroidal layer. Therefore, the nonperfusion of choroidal capillaries, or the choriocapillaris, could result in functional vision loss [

1]. In addition to supplying the outer retina with nutrients, the choroid is responsible for regulating both the temperature and the volume of the eye. The choroidal circulation is a high-flow system that has a relatively low oxygen content, even though it is responsible for 85 percent of the total blood flow in the eye. The posterior choroid and the peripapillary region receive their blood supply from the short PCA, while the anterior sections of the choroid receive their blood supply from the long PCAs as well as the anterior ciliary artery. The ophthalmic artery gives off a branch called the anterior ciliary artery, which supplies blood to the iris as well as the anterior choriocapillaris.

Even though diabetic retinopathy is well understood and frequently used as a diagnostic tool to track the advancement of the illness, routine clinical ophthalmology evaluation of the choroid is quite uncommon [

2].According to new research, the diabetic choroid may experience comparable phenomena [

3].Also, diabetic retinopathy has been seen in alloxan and streptozotocin (STZ) diabetes models [

4].The rats and monkeys that get diabetes on their own show choroidal vascular leakage and capillary dropout and display evidence of choroidal neovascularization. Thickening of the basement membrane coined the term diabetic choroidopathy [

5]. It's possible that the choroidal vasculopathy that comes with diabetes plays a bigger role in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic choroidopathy may also be the cause of the inexplicable loss of visual function that can happen to diabetic subjects who do not have retinopathy [

3].

In experimental models like type 1 diabetes, streptozotocin (STZ) is a commonly used drug to generate insulin-dependent diabetic mellitus. STZ causes potentially dangerous systemic microvascular changes and consequences. It also has toxic effects on islet beta cells. The vascular corrosion casting technique combined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) has become an important basic tool for learning about how organ microvasculation works. This will help with future physiological and pathological studies. The three-dimensional architecture of the vascular bed and network can be found using this conventional method [

6]. This technique produces a readily comprehensible, stunning, and identifiable three-dimensional picture of the entire choroid as well as an enlarged localized lesion, all while demonstrating the vascular architecture.

At present, the use of modern methods of treating diabetic eye disease has many effects on patients. Regardless of the cost of treatment being quite expensive and various side effects from treatment, there is currently a lot of research on herbs that have the power to cure diabetes. Gymnemic acid is an important substance in

Gymnema sylvestre. It is another herb that is used to treat diabetes [

7]. This has the effect of increasing the efficiency of β-cell function in the pancreas and slowing down the absorption of glucose in the small intestine. This results in an increase in the amount of insulin in the body and can reduce blood sugar levels in diabetic rats [

8]. Currently, there are research studies on diabetes that affect various organs in the body. And this time, we studied the action of gymnemic acid as another option for treating diabetic conditions. Within the scope of this research project, the effects of gymnemic acid derived from

Gymnema sylvestre on microvascularity and structural issues within the choroid of rats that had been given STZ to induce diabetes were investigated.

Glabridin is a polyphenolic flavonoid that is also recognized as an active component of the

Glycyrrhiza glabra, which is also known as the licorice plant. Streptozotocin-produced diabetic rats have shown that it lowers blood glucose levels [

9]. Additionally, it demonstrated evidence of having an antioxidant effect in the kidneys of diabetic mice through an increase in superoxide dismutase (SOD) and a decrease in malondialdehyde (MDA) content [

10]. The treatment of glabridin to diabetic rats with glabridin resulted in a reduction in serum glucose as well as hepatic collagen type I, which caused the livers of the diabetic rats to return to their normal structures [

9]. Because of this, glabridin's ability to lower blood sugar and fight inflammation and scar tissue may be important parts of future drug development plans for diabetes. For that reason, this study is going to use a microscope to look at how gymnemic acid and glabridin affect the blood vessels in the choroidal layer of diabetic rats' eyes. A study that compares the levels of VEGF, and CD31 proteins after gymnemic acid treatment. These two proteins cause angiogenesis, a process that can result in eye damage and diabetic retinopathy. Therefore, it is expected that this will be another research project that will bring benefits. and as a guideline for using herbs to prevent diabetes-related eye complications from causing vision loss. Therefore, it is expected that this will be another research project that will bring benefits and as a guideline for using herbs to prevent diabetes-related eye complications from causing vision loss.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and the methodology of the study

In this investigation, we used male Wistar rats that were eight weeks old and weighed between 200 and 250 g. At the center of the Southern Laboratory Animal Facility at Prince of Songkla University, a total of fifty rats were housed in an environmentally controlled laboratory environment. The conditions included a humidity level of 50 + 10%, a temperature of 25 + 2 degrees Celsius, and a light/dark cycle of 12 hours on, 12 hours off. The rodents had unrestricted access to both the food and the water from the tap. The Prince of Songkla University Animal Ethics Committee gave its stamp of approval to every single experimental technique that was carried out (MHCSI 6800.11/236, Ref.3/2020).

2.2. Initiation of diabetes in animals

One week after becoming accustomed to their new environment, the rats were divided at random into five groups (each with ten members) as follows: In the control group, the rats were receiving a standard rat diet. The standard diet was given to the rats in the diabetic group, which was denoted by the acronym streptozotocin (STZ). The diabetic rats in the DM+GB group were given a standard diet and were also given glabridin from Licorice 4 mg/kg BW (purified > 98% by HPLC analysis performed by Shaanxi Langrun Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Xian, China) in 0.5 ml of 0.5% Tween 80 solution as a supplement. The diabetic rats in the DM+GM group were given a standard diet and were also given gymnemic acid from Gymnema sylvestre 400 mg/kg BW (purified > 75% by HPLC analysis) in 0.5 ml of 0.5% Tween 80 solution as a supplement. The diabetic rats in the DM+GR group were given a standard diet and were also given glyburide (Sigma-Aldrich; Merk KGaA) at 4 mg/kg in 0.5 ml of 0.5% Tween 80 solution as a supplement. To inducing hyperglycemia, a single dosage of streptozotocin (STZ) 60 mg/kg (Sigma-Aldrich; Merk KgA, Germany) that was dissolved in 0.1 mol/l in citrate buffer was administered intraperitoneally (I.P.) to all rats, except for those in the control group of rats. Citric buffer was the only substance that was administered to the control rats. Blood glucose levels were tested using a glucometer manufactured by Roche Diagnostics GmbH in Mannheim, Germany, 3 days after an injection of STZ. Those rats who had a glucose level in their blood that was higher than 250 mg/dl were categorized as diabetic rats. The amount of glucose in the blood was measured once a week. Eight weeks after receiving therapy, the rats were put to death, and a blood sample was taken from their hearts using a cardiac puncture so that kidney function could be evaluated. After dissection, the kidneys were placed in a 10% formalin buffer to be preserved.

2.3. Preparation of histological slides for H&E and Mason's trichrome staining procedures

As a part of the preparation for the histological investigation, the eye tissues of all of the groups were dissected, and then they were promptly fixed in 10% formalin. This was done to assess the histological alterations and measure the lumen diameter of the choroidal arteries. They were subjected to a graded sequence of ethanol that progressed through 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100% for one hour each, with two changes in between. Before filtering, three changes of xylene lasting thirty minutes each were employed as a cleaning reagent. The tissue was then fixed in paraffin, sectioned at five micrometers thick, and stained with H&E and Masson's trichrome (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). An Olympus light microscope, model BX-50, manufactured in Japan by Olympus, was used to inspect and photograph each segment. The Olympus cellSens software was used to get a measurement of the lumen diameter of the arteries.

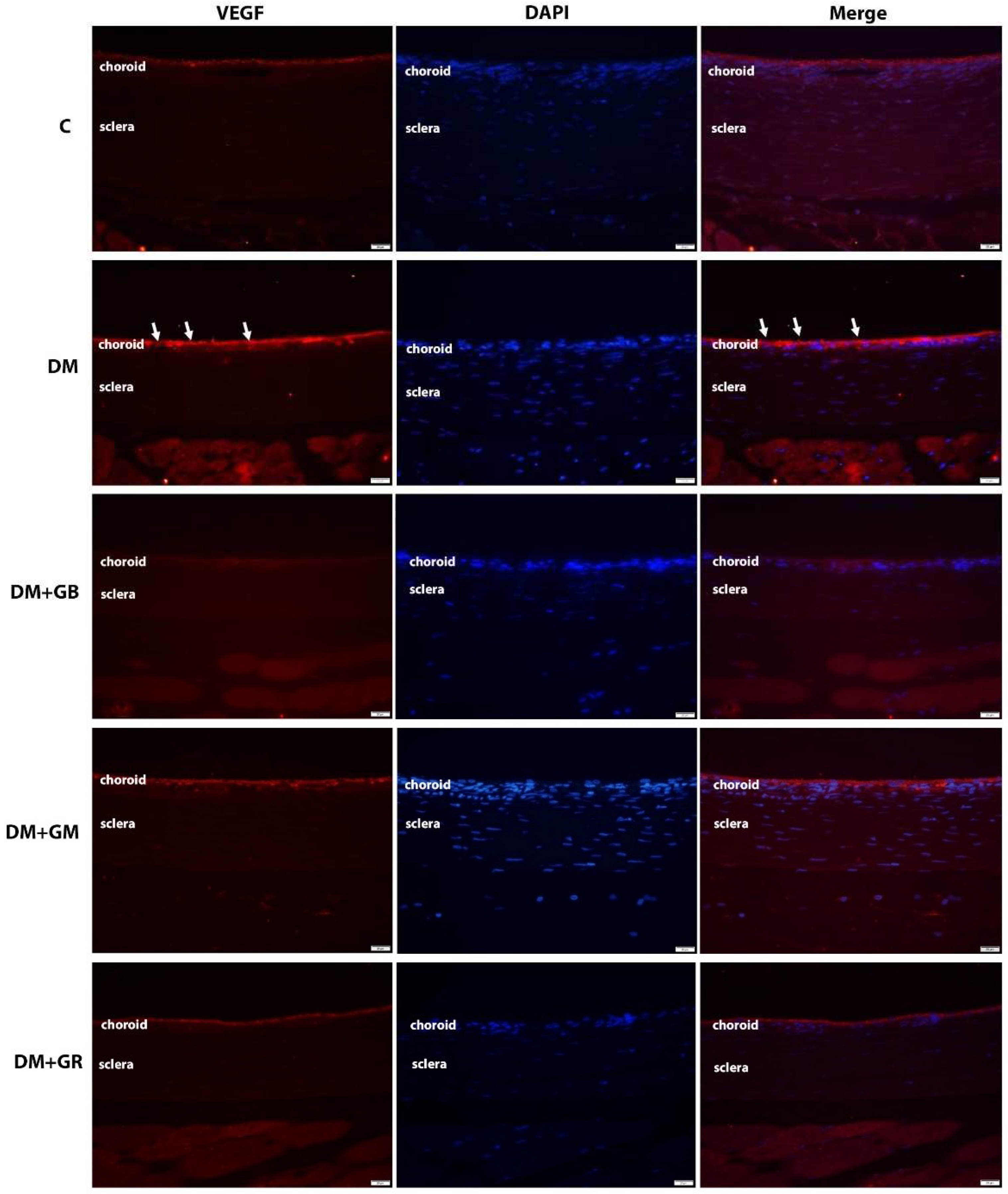

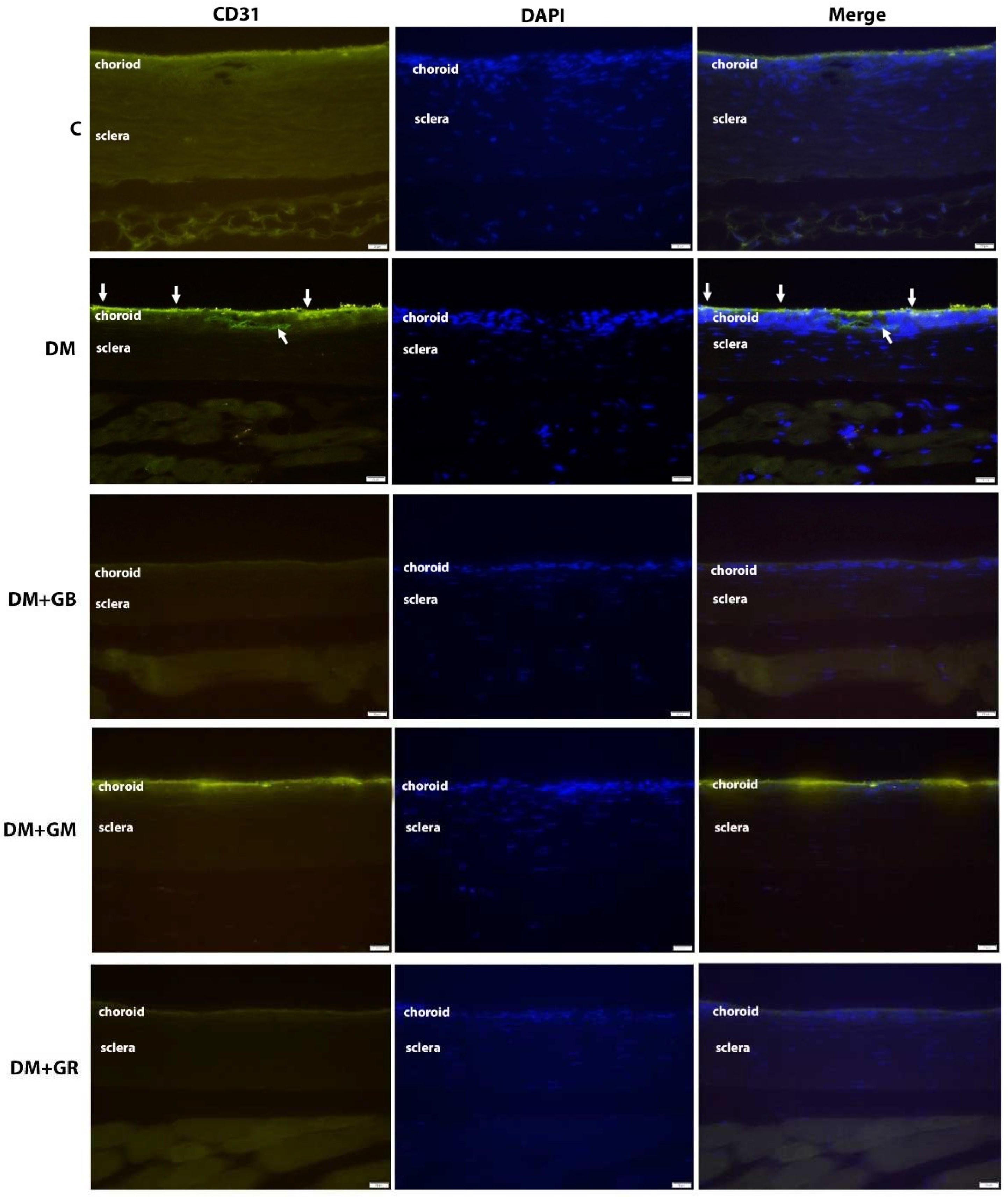

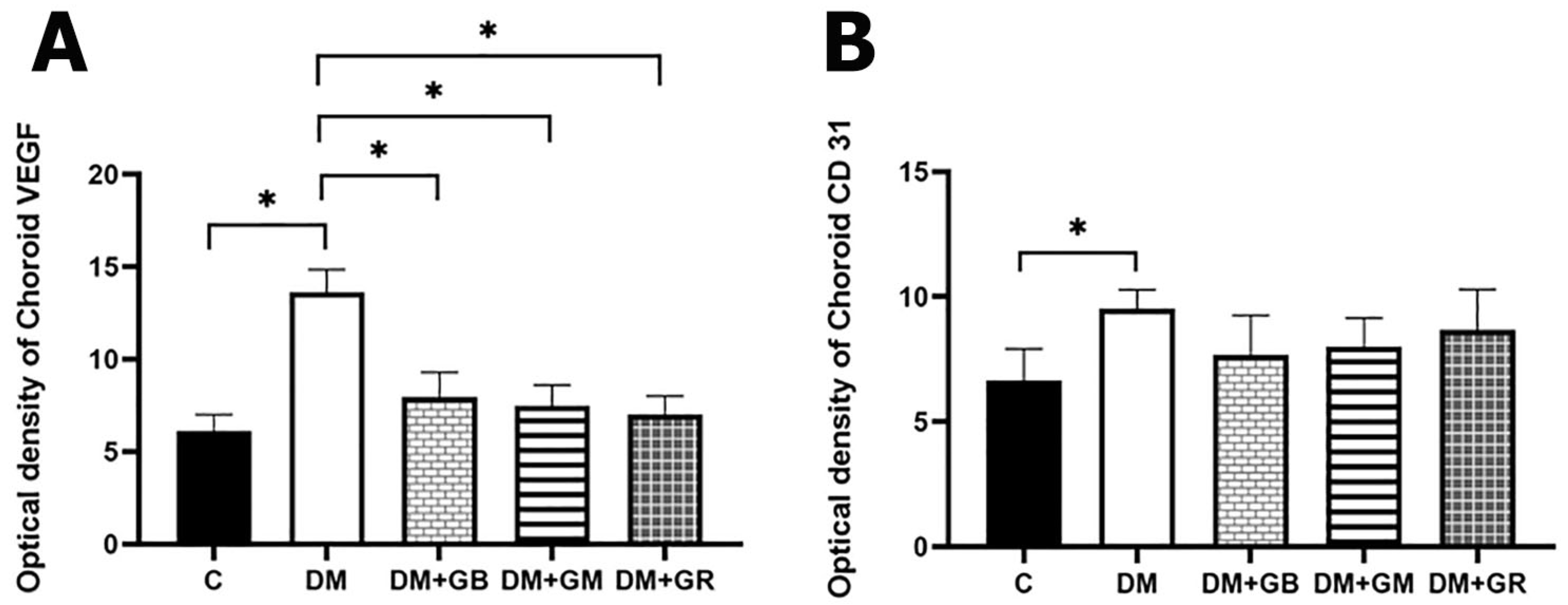

2.4. The immunofluorescence method was utilized to investigate the VEGF and CD31 concentrations.

The immunohistochemical approach was used to examine the levels of VEGF and CD31 expression in the choroid layer of the eye. In a nutshell, each slide was deparaffinized in xylene, hydrated in gradient ethanol, permeabilized in PBS buffer, and then blocked with serum in PBS. Finally, the slides were washed in PBS. At a temperature of 4

oC for one night, the slides were treated with rabbit anti-VEGF and mouse anti-CD31 antibodies from Abcam, Cambridge, UK, diluted 1:200 in blocking serum. The sections were washed three times with PBS before being put in blocking solution with a fluorescein horse anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibody and a Texas red goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Inc.). They were left there for two hours at room temperature to find VEGF and CD31. A fluorescent microscope (model BX-50; manufacturer: Olympus, Japan) was used to evaluate the images. Within each specimen, five glomeruli were chosen at random for examination. Image J software from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was used to quantify the chemiluminescence intensity. The optical density (OD) of each sample was standardized based on the glomerular area of the sample. The X600 photos were selected after being grayscaled with 8 bits and then transformed. To obtain accurate measurements of the area, integrated density, and background intensity, The optical density (OD) calculation followed Fu et al.'s (2018) instructions, as shown in the choroidal layer [

11].

2.5. An investigation of the choroid vascular corrosion cast process using a scanning electron microscope

The left ventricle of each group of rats was perfused with a 0.9% sodium chloride solution to flush the blood out of the blood vessels. After that, a combination of plastic called PU4ii casting resin, which is based on polyurethane (vasQtec), was injected into the blood circulation of rats. In order to ensure that the plastic was properly polymerized, the animal that had plastic injected into it was first left at room temperature for 30 minutes, and then it was submerged in hot water for 3 hours. After the polymerization process was complete, the eye was extracted, and the tissue was then corroded in a 10% KOH solution at room temperature for 30–40 days. The vascular cast for the eye was given a rinsing in a tap with a gentle stream of water and then washed in many changes of distilled water to remove any leftover tissues. After that, it was allowed to air dry at ambient temperature, and then it was mounted to a metal stub using double glue tape and carbon paint before it was coated with gold using sputtering apparatus. Finally, an SEM (JEOL JSM-5400) with a 10 KV accelerating voltage was used to look at the choroid area in the eye cast. A piece of software called SemAfore was used to determine the diameter of the blood veins in the choroid.

2.6. Examination of data based on statistics

The findings were summarized using the mean value together with the standard error of the mean (SEM). The study of statistics was carried out with the use of ANOVA, and then the Bonferroni posttest was used. It was determined that statistical significance had been reached when the value of p was lower than 0.05.

4. Discussion

From the results of this study, it is known that after the end of the 8-week experiment, rats in the diabetes (DM) group had higher blood sugar levels and significantly decreased body weight. Compared to the control group (C), consistent with the results of a 2021 study by Sandech et al., the effects of blood sugar levels and body weight were studied. Streptozotocin at a dose of 60 mg/kg BW induces diabetes in rats. And the experiment was conducted for a period of 8 weeks. It was found that the blood sugar level of the diabetic rats increased, and the body weight of the rats decreased with statistical significance compared to normal rats due to streptozotocin [

8]. Because of its low cost and the fact that it has less adverse effects than other medications, it is one of the diabetogenic medications. Specifically, the process of alkylation of DNA is linked to the specific harmful impact that it has on β-cells that are located within the pancreas [

12]. Because of this, the production of the hormone insulin is slowed down, which is a consequence of the action. This is accomplished via binding with GLUT2 to distribute streptozotocin, which can enter cells. The DNA strand is then modified by the addition of a methyl group, which leads to the destruction of beta cells and necrosis. The result causes the body to have a condition. hypoinsulinemia and hyperglycemia, and as a result, the body has higher blood sugar levels [

13] at the same time. One of the obvious specific characteristics of diabetes is a decrease in body weight. As a result of the loss or deterioration of proteins in the body, the body fluid of diabetic rats decreased [

14].

Results from this study show that after the end of the 8-week experiment, diabetic rats treated with glabridin at a dose of 40 mg/kg (DM+GB) showed a statistically significant decrease in blood sugar levels when compared to the rats in the diabetic group. Administration of glabridin at a dose of 40 mg/kg BW to rats induced with diabetes by injecting streptozotocin at a dose of 60 mg/kg BW was able to increase levels of antioxidants (superoxide dismutase; SOD) and reduce levels of free radicals (malondialdehyde; MDA), which causes the body to reduce oxidative stress, thus helping to reduce blood sugar levels [

9,

10]. In addition, this study shows that at the end of the 8-week experiment, diabetic rats treated with gymnemic acid at a dose of 400 mg/kg BW had a reduction in blood sugar levels compared to control rats. A study involving the administration of gymnemic acid at 400 mg/kg BW to rats induced with diabetes by streptozotocin injection at a dose of 60 mg/kg BW for a period of 60 days found that the blood sugar levels of diabetic rats The levels of diabetic rats treated with gymnemic acid were significantly reduced compared to untreated diabetic rats [

8]. This is because the chemical structure of gymnemic acid is similar in shape to the molecule of diabetic rats. sugar Therefore, it can bind to the receptor instead of the sugar molecule in the taste buds on the tongue. It makes you unable to taste sweetness. It also binds to receptors in the small intestine. It can delay the absorption of glucose into the small intestine [

15]. In addition, the administration of gymnemic acid can increase the number of beta cells in the pancreas. This is the reason why gymnemic acid can reduce blood sugar levels.

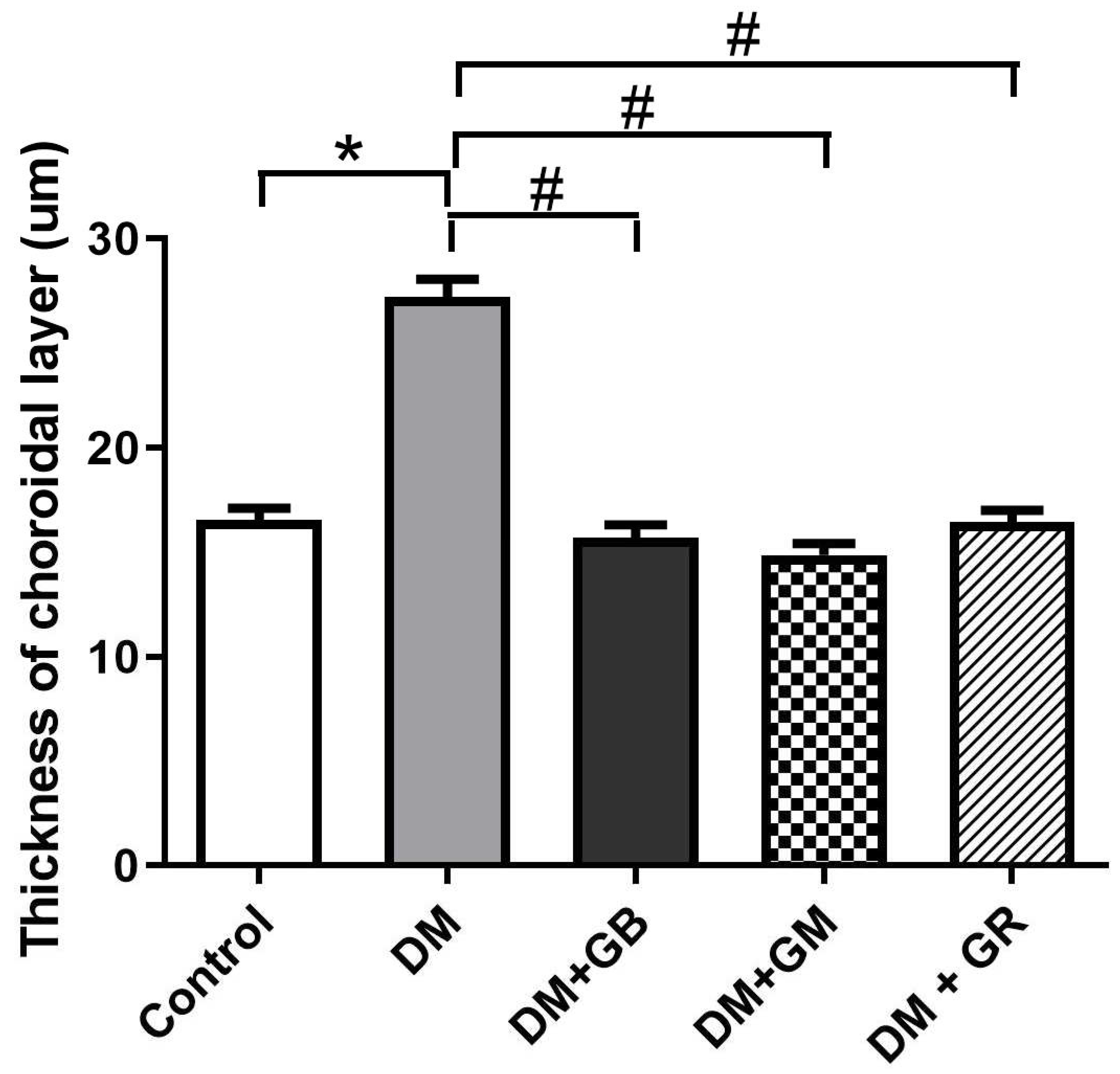

In the results of a study comparing the histological changes of cells and choroidal tissues in the eyeball using H&E and Masson's trichome staining, it was found that the thickness of the choroid layer in the diabetic (DM) rats was significantly increased when compared to the control rats. This is consistent with research in 2020 by Endo H. and colleagues who studied the thickness of the choroid layer in diabetic patients. The thickening of the choroidal layer is caused by the increased permeability of the choriocapillaris [

16]. Considering that the choroid is responsible of the blood flow to the eye, the autonomic nervous system plays a significant role in the autoregulation of choroidal blood flow. During the early stages of DR, the sympathetic innervation was engaged, which resulted in increased choroidal circulation, which ultimately led to an increase in the thickness of the choroid. At the same time, blood vessels in the choroid layer had a significantly increased thickness of the blood vessel wall., especially the connective tissue layer, or the tunica adventitia, when compared to the control group rats. Hyperglycemia is directly responsible for the acceleration of the atherosclerotic process, which in turn leads to the development of endothelial dysfunction. This dysfunction, in turn, leads to vasoconstriction, proinflammatory processes, and prothrombotic processes, all of which contribute to the development and rupture of blood vessels [

17].

Diabetes may be an independent factor that contributes to the thickening of the choroid, and subsequent progression of diabetic retinopathy (DR) may result in the reduction of choroid thickening. This may manifest as a thicker choroidal layer during the first stage of diabetic retinopathy (DR), which then gradually thins out as the disease progresses [

18]. The increased permeability of the choriocapillaris is what causes the thickening of the choroidal layer. Angiogenesis and cytokines that are caused by inflammation and oxidative stress may be the cause of the thickening of the choroidal layer in the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. This is because there is a possibility that these cytokines are producing an excessive quantity of expression. These cytokines include platelet-derived growth factor, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, VEGF, pigment epithelium-derived factor, and insulin-like growth factor 1, among others [

16]. Using Masson's trichrome staining to look at the choroidal artery from the choroidal tissues of diabetic rats showed that the vessel wall had become thicker and there were more collagen fibers deposited in the wall of the vessel. A narrowing of the lumen was also observed in rats with diabetes. The buildup of collagen can result in stenosis of the arteries. Recent collagen synthesis has the potential to act as a substrate, which can result in luminal narrowing [

19]. A narrowing of the arteries that provide blood to the body, particularly the head, face, and brain, is referred to as arterial stenosis [

20]. In diabetic patients, vascular problems are the result of the deterioration of the vascular wall [

20]. Since these histopathological alterations cause blood vessels to become rigid, they are unable to respond to either exogenous or endogenous stimuli, which prevents them from being able to efficiently regulate blood flow [

21].

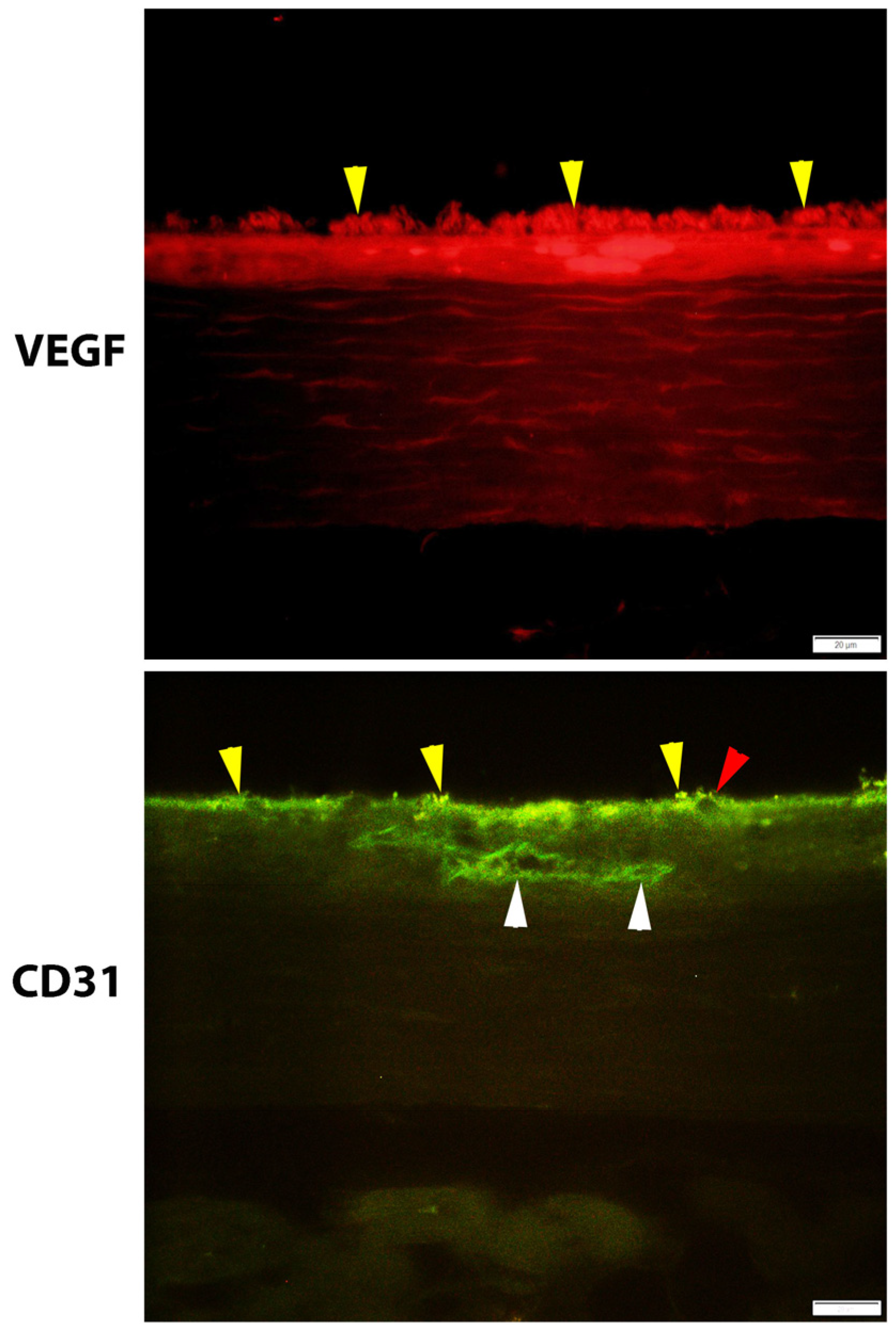

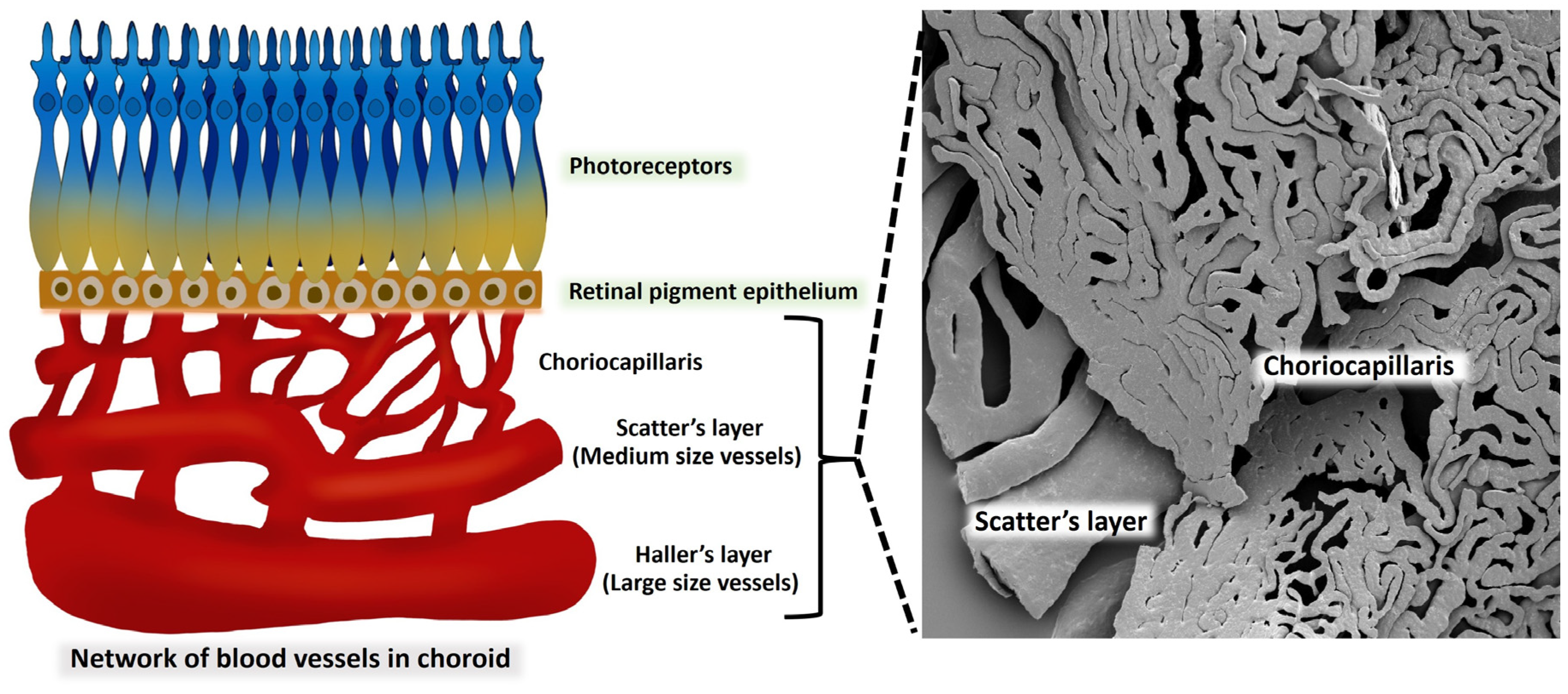

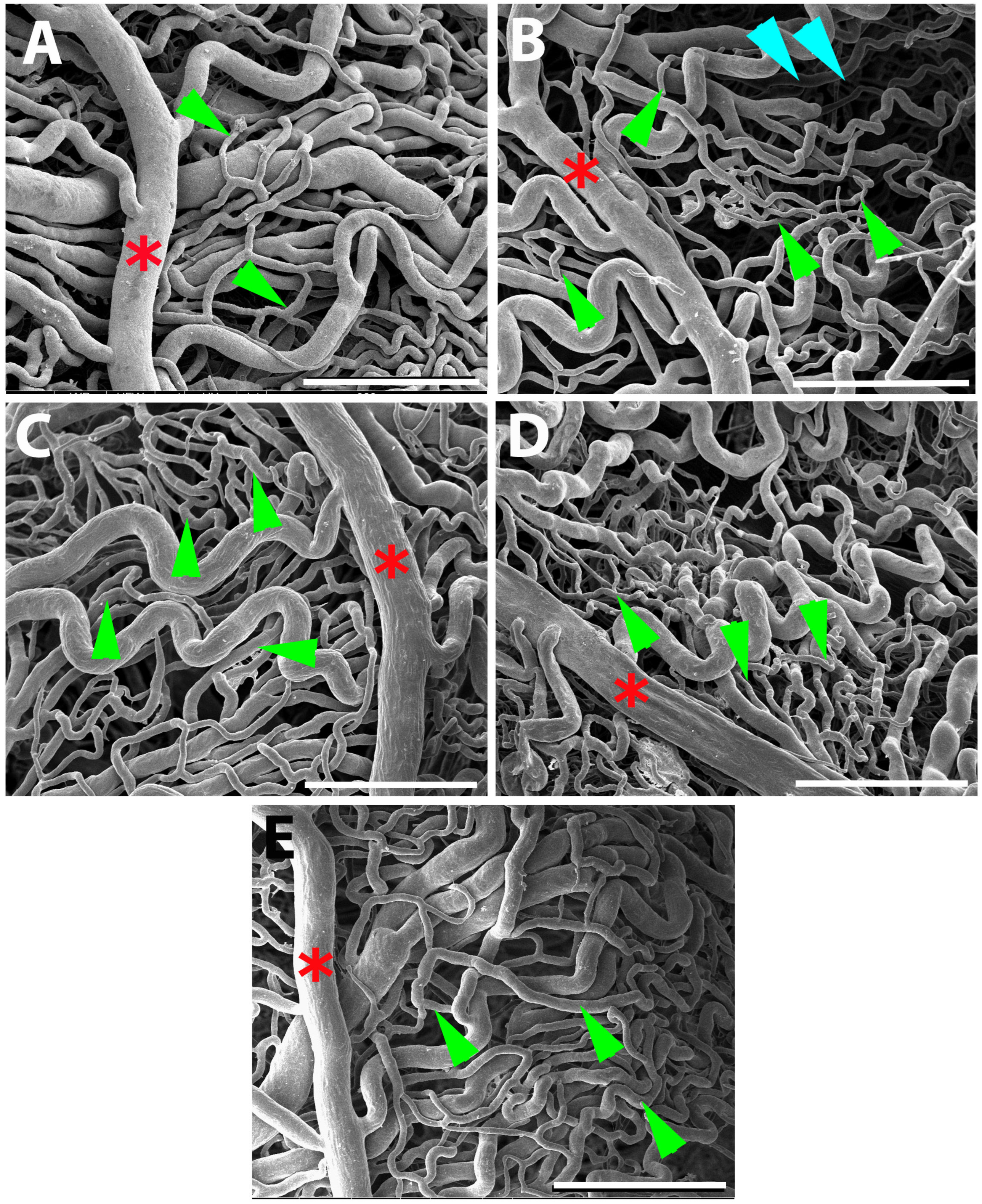

This study used induced diabetic rats as subjects and used SEM to show that the choroidal arteries were changed in a way that wasn't seen in any of the other five groups of rats. Choroidal damage is increasing in rats with diabetes mellitus. The choroid microvasculature is made up of choroid arteries, choriocapillaris, short-running arterioles and venules, and choroid arteries. The choroid arteries and the choriocapillaris were observed to have tortuosity, shrinkage, and widespread constriction. The choriocapillaris, which is the smallest vessel, was the most severely affected by the damage. In diabetic eyes, the choriocapillaris can become blocked, the blood vessels can change shape with more vascular tortuosity, the blood vessels can drop out, there can be areas of vascular non-perfusion, and the choroidal neovascularization can happen. These findings were strikingly comparable to those observed in the previous study. Hidayat and Fine [

22], who were the first to propose the idea of diabetic choroidopathy, discovered capillary dropout and choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in the enucleated eyes of diabetic patients. They used light and electron microscopy to make their observations. When the choriocapillaris is damaged, it can cause substantial damage to the function of the retinal tissue, particularly in the macula fovea.

All the gaps between the capillaries were not regular. Both the arterioles and the venules exhibited a significant amount of loss. Given the observations, there is indication that choroidal neovascularization has taken place. Higher blood glucose levels are the main cause of microvascular complications in diabetes, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. Numerous studies have demonstrated that hyperglycemia has a detrimental effect on the endothelium's functioning and causes pathological alterations that are associated with diabetes. In endothelial cells, hyperglycemia activates four primary molecular signaling systems. These mechanisms are in the cell membrane. Some of these are turning on PKC, speeding up the hexosamine pathway, making more advanced glycation end products, and speeding up the polyol pathway [

23]. PKC, for instance, affects the activation of a variety of growth factors and alters the activity of vasoactive factors in the context of diabetes microvascular problems. Vasoactive factors include vasodilators like nitric oxide (NO) as well as vasoconstrictors like angiotensin II and endothelin 1. These vasoactive factors are responsible for relaxing blood vessels.

VEGF plays a significant role in the process of neural regeneration and angiogenesis that takes place after an ischemic stroke [

24]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that VEGF, which is the main regulator of angiogenesis, may directly modulate the size of lumens. Lumen diameter is a reaction to blood pressure and blood flow, which influence the delivery of oxygen and immune surveillance that occurs, respectively. Furthermore, VEGF and Ang I are capable of inducing hyperplasia, tortuosity, and a reduction in lumen diameter. These effects are highly potent [

8]. They are also quite good at inducing endothelial proliferation. It is for this reason that the increasing quantity of these two proteins causes the diameter of the lumen to become more constricted. In addition, it has been demonstrated that VEGF, which is the main regulator of angiogenesis, may directly modulate the size of lumens. Lumen diameter is a reaction to blood pressure and blood flow, which influence the delivery of oxygen and immune surveillance that occurs, respectively.

The mechanism, in conjunction with the decreased permeability of Bruch's membrane that is observed with advancing age, causes a reduction in the amount of oxygen that is supplied to the retina as one gets older [

25]. However, this can also result in choroidal neovascularization. Retinal and retinal pigment epithelial cells are responsible for the release of VEGF, which results in the dilation of the choroidal capillaries and an increase in blood flow. Diabetes, in general, is associated with decreased cellular proliferation and EC dysfunction, which causes angiogenesis to be impaired [

26]. The pathogenesis of DR has been linked to several pro-angiogenic cytokines, such as insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). However, VEGF is generally acknowledged as the most important cytokine in the process of driving DR. Renin-angiotensin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma are two more pathways that are taken into consideration. ROS levels rise, which creates IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, iNOS, IP-10, MMPs (especially MMP9), C5-9, and TNF-α. These ROS cause inflammation at the cellular level [

27]. ICAM-1 (CD54) or E-Selectin (CD62E); VCAM-1 (CD106); and PECAM (CD31) are examples of endothelial adhesion molecules that are increased in endothelial cells. CD31 has been considered a potential target for atherosclerosis since it is considered a proinflammatory and, thus, a proatherosclerotic molecule. Additionally, CD31 is involved in a wide variety of other biological processes, such as angiogenesis, apoptosis, platelet aggregation, and thrombosis [

28]. It is important for the vascular endothelium to be able to survive and respond properly to different types of mechanical, immune, and metabolic stresses [

29].

Additionally, the beneficial therapeutic impact of gymnemic acid, which is the active component generated by Gymnema sylvestre, has been examined, and it was discovered that gymnemic acid was present in every region of the plant. Rats that were given gymnemic acid had lower levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and higher levels of antioxidants like glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), catalase (CAT), and malondialdehyde (MDA) and these levels went down [

30]. The glycolysis pathway relies heavily on the enzyme known as gymnemic acid. It has been discovered that it interacts with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The favorable therapeutic action of glabridin isolated from licorice is that it considerably increases the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) while simultaneously lowering the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the liver, kidney, and pancreas. The compound known as glabridin is a powerful anti-inflammatory drug, antioxidant, and free radical scavenger [

31]. So, the hypoglycemic effects of glabridin and gymnemic acid in rats that were given STZ may be linked to the antioxidant effects of these two compounds, at least in part.

Figure 1.

Light micrographs of the choroidal and scleral (SC) layers can be separated by choroidoscleral junctions (black arrows) stained with H&E (A-E) and Masson’s trichrome (F-J) in all 5 groups of rats. The thickness of the choroidal layer in each group is presented with the green line. The choroidal layer is composed of choroid arteries (blue arrowheads). Changes in the histological characteristics of the choroidal layer were observed in the DM group. They were the thickness of the choroidal layer and the choroidal arterial wall, particularly in the region of the tunica adventitia (red asterisk). scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 1.

Light micrographs of the choroidal and scleral (SC) layers can be separated by choroidoscleral junctions (black arrows) stained with H&E (A-E) and Masson’s trichrome (F-J) in all 5 groups of rats. The thickness of the choroidal layer in each group is presented with the green line. The choroidal layer is composed of choroid arteries (blue arrowheads). Changes in the histological characteristics of the choroidal layer were observed in the DM group. They were the thickness of the choroidal layer and the choroidal arterial wall, particularly in the region of the tunica adventitia (red asterisk). scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 2.

The effect of glabridin and gymnemic acid on thickness of choroidal layer in five group of rats at 8 weeks demonstrated the significantly increased in the DM group compared with the control rats (*p<0.001). After supplementation of glabridin, gymnemic acid, and glyburide, thickness of choroidal layer have decreased in DM+GB, DM+GM, and DM+GR groups compared with the DM rats ( #p<0.001) Values are mean + SE.

Figure 2.

The effect of glabridin and gymnemic acid on thickness of choroidal layer in five group of rats at 8 weeks demonstrated the significantly increased in the DM group compared with the control rats (*p<0.001). After supplementation of glabridin, gymnemic acid, and glyburide, thickness of choroidal layer have decreased in DM+GB, DM+GM, and DM+GR groups compared with the DM rats ( #p<0.001) Values are mean + SE.

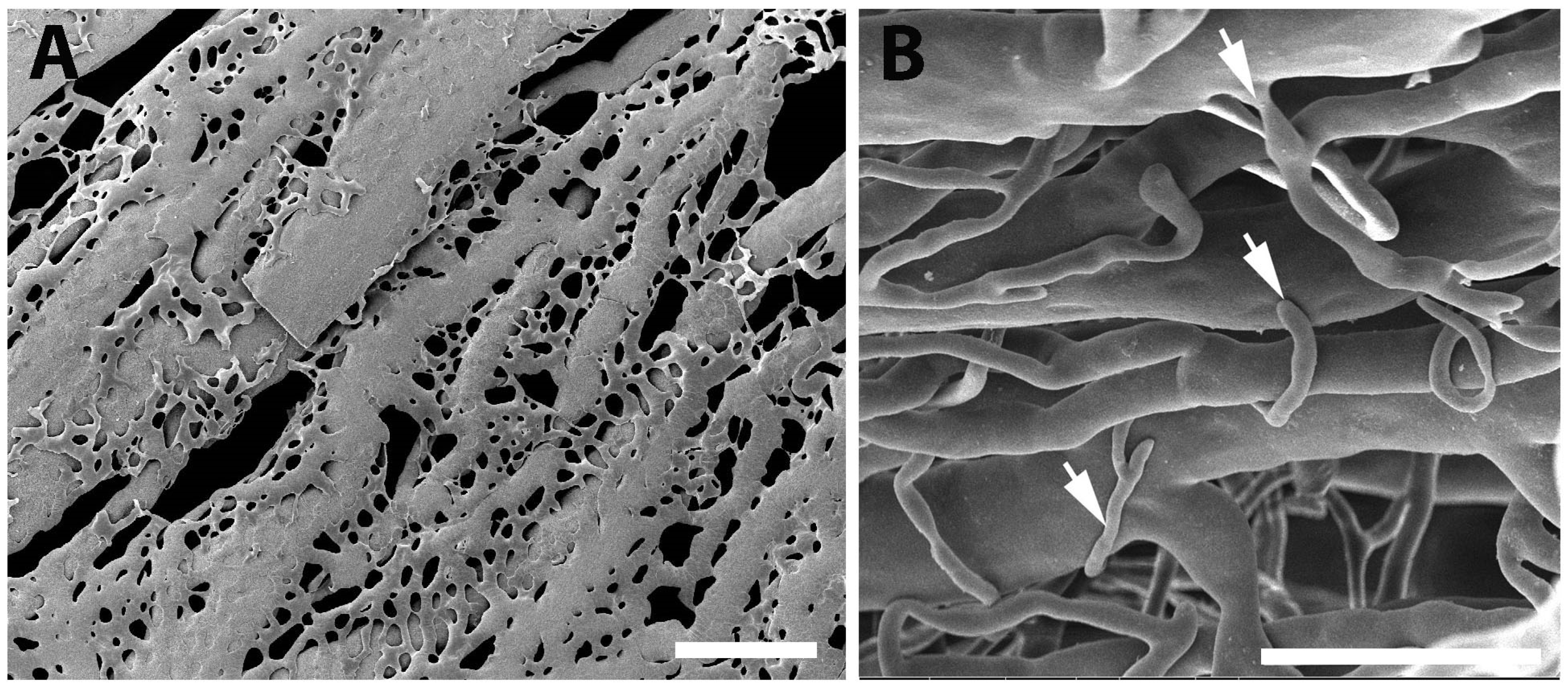

Figure 7.

A comparison of the choroidal vascular structure and the vascular corrosion casting framework is indicated in this diagram. The outermost layer of the choroid, which is also known as Haller's layer, is composed of vessels with a large vessel capacity. Sattler's layer is the name given to the innermost layer of the choroid, which is composed of vessels that are significantly smaller in size than the vessels that make up the outermost layer. An extensive number of anastomotic capillaries are what constitute the choriocapillaris of the choroid.

Figure 7.

A comparison of the choroidal vascular structure and the vascular corrosion casting framework is indicated in this diagram. The outermost layer of the choroid, which is also known as Haller's layer, is composed of vessels with a large vessel capacity. Sattler's layer is the name given to the innermost layer of the choroid, which is composed of vessels that are significantly smaller in size than the vessels that make up the outermost layer. An extensive number of anastomotic capillaries are what constitute the choriocapillaris of the choroid.

Figure 8.

SEM micrographs with vascular corrosion casting technique/SEM in all 5 groups of rats: Control (A), DM (B), DM+GB (C), DM+GM (D) and DM+GR (E). The choroid artery (red asterisk) gives branches to supply the choroidal layer. Many anastomotic capillaries are what make up the choriocapillaris of the choroid (green arrows). In the DM group, choroid artery had a small diameter, and choriocapillaris shrank. Capillaries dropout (blue arrowheads) of choriocapillaris was also present in DM group. Scale bar = 300.

Figure 8.

SEM micrographs with vascular corrosion casting technique/SEM in all 5 groups of rats: Control (A), DM (B), DM+GB (C), DM+GM (D) and DM+GR (E). The choroid artery (red asterisk) gives branches to supply the choroidal layer. Many anastomotic capillaries are what make up the choriocapillaris of the choroid (green arrows). In the DM group, choroid artery had a small diameter, and choriocapillaris shrank. Capillaries dropout (blue arrowheads) of choriocapillaris was also present in DM group. Scale bar = 300.

Figure 9.

SEM micrographs with vascular corrosion casting technique/SEM in DM group. (A) The arrangement of choriocapillaris is not dense and untidy. It has link to one another, resulting in the formation of a flatter sheet. The capillaries dropout (blue arrowheads) of choriocapillaris was also present. Furthermore, the sprouting of blood vessels (white arrows) were discovered in regions of the scatter's layer that included choroidal arteries that were significantly more exposed. Scale bar = 300.

Figure 9.

SEM micrographs with vascular corrosion casting technique/SEM in DM group. (A) The arrangement of choriocapillaris is not dense and untidy. It has link to one another, resulting in the formation of a flatter sheet. The capillaries dropout (blue arrowheads) of choriocapillaris was also present. Furthermore, the sprouting of blood vessels (white arrows) were discovered in regions of the scatter's layer that included choroidal arteries that were significantly more exposed. Scale bar = 300.

Table 1.

A comparison of blood glucose levels in different groups. (mg/dl).

Table 1.

A comparison of blood glucose levels in different groups. (mg/dl).

| Wk. |

C

(mg/dl) |

DM

(mg/dl) |

DM+GB

(mg/dl) |

DM+GM

(mg/dl) |

DM+GR

(mg/dl) |

| 1 |

70.5+4.92 |

360.50+32.33* |

314.83+30.71* |

362.89+49.29* |

297.67+20.69** |

| 2 |

72.00+5.49 |

290.50+34.44* |

311.67+49.73* |

269.22+35.60* |

241.00+36.43#

|

| 3 |

79.17+3.25 |

351.17+43.25* |

305.33+52.59* |

188.00+41.51* |

176.50+38.65#

|

| 4 |

73.33+3.57 |

253.67+30.75* |

170.67+41.11 |

240.89+48.70* |

187.50+45.61 |

| 5 |

72.00+3.98 |

301.50+55.41* |

137.00+40.87##

|

289.78+50.06##

|

192.50+54.94** |

| 6 |

73.58+3.55 |

351.00+34.82* |

69.50+13.69#

|

249.78+49.68##

|

149.00+47.48#

|

| 7 |

73.00+4.25 |

457.00+20.99* |

158.33+37.64#

|

259.00+45.53##

|

165.83+49.04#

|

| 8 |

74.67+3.31 |

353.83+35.16* |

174.50+30.99#

|

213.44+40.73##

|

160.67+52.46#

|

Table 2.

A comparison of the body weight in different groups. (g).

Table 2.

A comparison of the body weight in different groups. (g).

| Wk. |

C(g) |

DM(g) |

DM+GB(g) |

DM+GM(g) |

DM+GR(g) |

| 1 |

256.66+5.25 |

178.83+3.56* |

173.33+4.71* |

240.83+4.24***** |

197.66+8.24* |

| 2 |

286.50+6.17 |

187.33+5.52* |

181.16+5.93* |

216.38+10.03*** |

221.33+14.33**** |

| 3 |

305.66+8.55 |

178.83+7.60* |

181.00+8.09* |

232.33+8.13*** |

215.50+19.72**** |

| 4 |

325.50+8.17 |

167.50+10.45* |

179.16+9.15* |

231.66+9.19** |

211.33+11.81** |

| 5 |

342.66+9.02 |

171.83+12.38#

|

166.50+13.52 |

263.33+15.15##

|

212.16+10.28####

|

| 6 |

352.50+8.01 |

173.50+11.01#

|

179.16+13.28 |

267.50+15.31##

|

209.33+7.85####

|

| 7 |

370.50+8.66 |

159.50+13.52#

|

175.50+13.04 |

275.83+16.86##

|

199.00+8.03####

|

| 8 |

371.00+9.27 |

182.00+13.82#

|

191.00+14.61 |

286.66+18.28###

|

222.83+6.25####

|

Table 3.

The mean wall thickness, diameter, and lumen diameter of the choroid arteries (CRA) in all 5 groups of rats: control group, DM group, and DM+GB group., DM+GM group and DM+GR group at 8 weeks.

Table 3.

The mean wall thickness, diameter, and lumen diameter of the choroid arteries (CRA) in all 5 groups of rats: control group, DM group, and DM+GB group., DM+GM group and DM+GR group at 8 weeks.

| Groups |

Wall thickness of CRA (µm) |

Diameter of lumen of CRA (µm) |

| Control |

9.48 ± 1.13* |

50.47 ± 11.37* |

| DM |

16.35 ± 5.01 |

39.12 ± 9.27 |

| DM+GB |

10.23 ± 1.11* |

52.52 ± 11.10* |

| DM+GM |

10.41 ± 1.44* |

53.71 ± 7.12* |

| DM+GR |

9.80 ± 1.78* |

51.58 ± 8.11* |

Table 4.

The average diameters of choroid arteries (CRA), and choriocapillaris in control DM, DM+GB, DM+GM and DM+GR groups at 8 weeks.

Table 4.

The average diameters of choroid arteries (CRA), and choriocapillaris in control DM, DM+GB, DM+GM and DM+GR groups at 8 weeks.

| Groups |

|

Diameters of blood vessels (µm), mean + SE |

|

| |

|

Choroidal arteries |

|

Choriocapillaris |

|

| Control |

|

89.73±2.82 |

|

10.52±0.72 |

|

| DM |

|

60.31±2.71* |

|

4.68±0.65* |

|

| DM+GB |

|

81.18±3.56 |

|

8.88±0.70 |

|

| DM+GM |

|

80.31±3.83 |

|

7.76±0.82 |

|

| DM+GR |

|

79.82±4.73 |

|

9.54±0.78 |

|

| P-value* |

|

< 0.001 |

|

< 0.001 |

|