1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a rapidly increasing global health burden, and diabetic retinopathy (DR) stands out as one of its most serious microvascular complications. It is estimated that around 22% of people with diabetes worldwide develop DR, while approximately 6% suffer from vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) (Sasongko, 2017). In 2020, this accounted for about 103 million adults affected by DR, with projections indicating that the number will rise to over 160 million by 2045, in line with the global diabetes epidemic (Lechner, O’Leary & Stitt, 2017; Garcia-Medina et al., 2020).

Regional prevalence further demonstrates the magnitude of this problem. In the United States, DR is estimated to affect 26.4% of diabetic patients, while in India, prevalence studies report 16.9% in patients under 50 years, with similar rates in older age groups ranging from 18% to 19%. Such findings confirm that DR is not only widespread but also consistently present across various populations and age brackets, highlighting its role as a major cause of preventable blindness worldwide (Feenstra, Yego & Mohr, 2013; Baptista, Paniagua & Tavares, 2010).

These prevalence data underscore the pervasive impact of DR and the urgent need for preventive and therapeutic strategies. Conventional management focuses on systemic control of diabetes, but adjunctive approaches such as antioxidants—including tocotrienol-rich vitamin E (Tocovid)—have shown potential in reducing disease progression and protecting retinal health (Ruamviboonsuk, 2022). This combination of systemic management and emerging therapies offers hope in addressing the global burden of DR (Chiew et al., 2021; Garcia-Medina et al., 2020).

Diabetic retinopathy is a microvascular disorder of the retina resulting from the long-term effects of diabetes mellitus (DM) (Shukla and Tripathy, 2023). This disorder is classically described by progressive changes in the microvasculature leading to retinal ischemia, neovascularization, changes in retinal permeability, and macular edema. According to recent studies, retinal neurodegeneration is a crucial trait associated with disease progression, and early retinal nerve injury precedes microangiopathy. Meanwhile, oxidative stress is a causative factor in increased capillary permeability, damage to the blood-retinal barrier (BRB), retinal capillary cell apoptosis, microvascular abnormalities, and neovascularization (Oshitari, 2023). DR is generally managed through strict glycemic control and regular ophthalmologic monitoring. A more severe DR leads to a tighter control schedule. In patients with severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), examinations can be performed every 2-4 months. The first-line treatment for patients with PDR is anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF). However, this treatment is only effective in treating cases of diabetic macular edema (DME). Current DR treatment is still focused on treating advanced DR, often after permanent damage has occurred, necessitating preventive care or early pathology management. According to the results of a previous study, dietary supplements containing antioxidants are associated with inhibiting retinal metabolic abnormalities, reducing apoptosis, and promoting pericyte recovery (Domenech and Marfany, 2020).

Several vitamin supplements have been widely reported to be beneficial in DR. This includes vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol), an essential micronutrient and fat-soluble antioxidant with a proposed role in protecting tissues from uncontrolled lipid peroxidation (Lee, 2010). The vitamin also contains essential protein functions and gene-modulating effects (Galli et al., 2022). In a meta-analysis, alpha-tocopherol supplementation was found to reduce total cholesterol (TC) levels and increase high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) when administered for ≥12 weeks.

Buah merah (Pandanus conoideus Lamk.) is a natural plant native in Indonesia, offering numerous benefits. This fruit is known to have a high content of monounsaturated fatty acids (oleic acid) and various biochemical compounds, such as carotene, cryptoxanthin, tocopherol, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids, with potential applications in functional foods and medicine. The chemical composition of buah merah varies, including 3.12-6.48% average protein value, 11.21-30.72% fat, 43.86-79.66% carbohydrates, 3.78-21.88 mg/100g vitamin C, 0.97-3.14 mg/100g vitamin B1, 0.53-1.11% calcium (Ca), 8.32-123.03% iron (Fe), 0.01-0.33% phosphorus (P), 333-3309 ppm total carotenoids, and 964-11918 ppm tocopherols (Murtiningrum, S., et al, 2011). Buah merah’s oil is empirically used by indigenous people as a natural medicine for various diseases, including cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, and HIV/AIDS (Wismandanu et al., 2016).

Red fruit oil also has been investigated for its potential benefits beyond glycemic control. Experimental studies suggest that its bioactive compounds, particularly carotenoids and tocopherols, may support renal protection in conditions associated with diabetes. In nephropathy models, red fruit oil demonstrated antihyperglycemic properties that correlated with improvements in kidney function, indicating its possible therapeutic role in diabetic nephropathy and related metabolic complications also including its anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective effects, to highlight its broad therapeutic potential and rationale for use in ocular disease(Khairani & Wijayanti, 2023). Despite these limitations, the interest in red fruit oil as a complementary intervention persists, with future directions likely focusing on refining dosage, formulation, and understanding its mechanisms of action in both metabolic and oxidative stress–related disorders (Handayani, 2013).

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effect of buah merah extract (Pandanus conoideus Lamk.) on retinal density and apoptosis in a diabetic rat model. The results are expected to serve as the basis for tracing the effect of administering buah merah extract on the protection of retinal cells in cases of DR.

2. Materials and Methods

An experimental test method was adopted with a post-test only control group design. This study was conducted in the animal laboratory and anatomical pathology laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University. The sample comprised male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) weighing 120-150 grams without any genetic modification status, genotype, and any previous procedures. All experimental animals were adapted for 1 week and given standard feed according to predetermined guidelines based on Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidebook, dead animal was exclusion criteria from this study (Akbarzadeh et al., 2007).

The sample comprised 30 male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus), divided into 5 groups, each consisting of 6 rats. These included group 1 (normal control), 2 (diabetic control), 3 (diabetic + 1 ml of buah merah extract), 4 (diabetic + 1.5 ml of buah merah extract), and 5 (diabetic + 2 ml of buah merah extract). Each 1 ml of buah merah extract was equivalent to a total of 12 mg carotenoids, 10 mg tocopherol, 1.348 mg alpha tocopherol, and 3.4 mg beta-carotene.

In this study, hyperglycaemia was induced using Alloxan (SIGMA USA, Cat. No. A7413, CAS Number: 2244-11-3) at a dose of 120 mg/kg body weight, administered intraperitoneally. Blood sugar in experimental animals was evaluated using Autocheck® multi-monitoring system, carried out by phlebotomy of blood through the peripheral tail vein of diabetic rats in group 4. Blood sampling was performed at three time points: before Alloxan induction, 3 days after Alloxan injection as check point examination, and 1 day before termination (after 2 weeks). The random blood glucose levels were categorized as normal (75-150 mg/dl), mild diabetes (150-200 mg/dl), and severe diabetes (200-400 mg/dl).

The buah merah extract used in this study was prepared at the Phytopharmaceutical Laboratory of Hasanuddin University to ensure standardization and quality control. Fresh buah merah was carefully selected, washed, dried, and subsequently ground into a fine powder prior to extraction. In this study, the process of producing buah merah extract involved selecting fully ripe fruits, cleaning, cutting, crushing, and hot extraction using a processing machine. The fresh fruit was then dried to retain about 20–25% of its fresh weight. The extraction process was conducted by maceration using 96% ethanol as the solvent, with the powdered sample completely immersed in ethanol. To optimize solvent penetration and metabolite dissolution, the mixture was gently agitated for 30 minutes every 8 hours over a 24-hour period. The solution was then filtered to separate the supernatant from the residue, and this maceration procedure was repeated three times on the residue to maximize extract yield. All resulting filtrates were combined and subjected to concentration under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator maintained at 45–50 °C, followed by further evaporation on a water bath to remove any residual solvent. Approximately 150 ml of extract was obtained from 250 grams of dried fruit pulp. The final product was a thick ethanolic extract, which was stored in an airtight container protected from light until use in the experiment.

In this study, each 1 ml of buah merah extract contains active compounds of 12,000 ppm (12 mg) total carotenoids, 10,000 ppm (10 mg) tocopherol, 3,581 ppm (3.4 mg) beta-carotene, 1,460 ppm (1.5 mg) B-cryptoxanthin, 1,368 ppm (1.36 mg) alpha tocopherol, 74.60% oleic acid, 8% linoleic acid, 2.1% decanoate, 21.0 mg sodium, and several other contents. Buah merah extract was administered orally to diabetic rats in groups 3, 4, and 5 at doses of 1 ml, 1.5 ml, and 2 ml, (equal to ~166–200 mg/kgBW, ~250–300 mg/kgBW, and ~333–400 mg/kgBW) respectively, using a sonde. Administration of the buah merah extract was performed by oral gavage at a frequency of once daily. Treatment commenced immediately after the post-alloxan blood collection in order to ensure that baseline hyperglycemia was established prior to intervention. The extract was administered consistently throughout the experimental period to maintain therapeutic exposure.

Buah merah extract was given to the treatment groups for 2 weeks according to the dose. In this study, one rat was reported dead in group 5. All rats were then terminated 2 weeks after administration of buah merah extract. Measurement of body weight and random blood glucose was carried out during pre-alloxan and post-alloxan induction, as well as pre-termination. After the experimental rats were treated, all groups were terminated and enucleated using the following procedures: (1) The experimental rat was anaesthetised using ether. (2) Rat was then fixed on the operating table. (3) The bulbus oculus was enucleated, and then the optic nerve was cut. (4) All enucleated rat’s eyes were stored in a pot containing 10% formalin for further histopathological examination.

Examination of photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cell densities, IHC assessment of photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cells caspase-3 expression, was carried out simultaneously after the second week. Histopathological evaluation was carried out using hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining at a magnification of 400x per field of view. The assessment included the counting of cell nuclei in the outer nuclear layer and retinal ganglion cell layer (corresponding to retinal photoreceptor nuclei) in three fields of view with the thickest density, and calculating the average count (Rajendran, 2012). Caspase-3 (Cat No. C9598, Sigma USA) expression in retinal ganglion cells was calculated quantitatively by counting the number of normal cells and those undergoing apoptosis. Meanwhile, caspase-3 expression in retinal photoreceptor cells was examined using immunohistochemistry of Invitrogen monoclonal caspase-3 antibodies and calculated at 400x magnification per field of view. This variable was calculated as the average of 3 fields of view with the thickest density. The scoring for photoreceptor cell caspase-3 expression used was the modified Immunoreactivity Scoring System (IRS) (Mitachi, 2021; Ichsan et.al, 2022), includes = (1) Negative: less than 10% per field of view, (2) Low: 10-20% per field of view, and (3) High: greater than 20% per field of view, this method was used to distinguish the expression of caspase-3 in the photoreceptor cells due to tiny size and high density cell layer. Moreover, the expression of caspase-3 in the retinal ganglion cell was counted using quantitative analysis (mean ± SD).

All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS® for windows ver.24.0 tools include ANOVA and LSD methods. The data were displayed by table, graph and narrative explanation.

3. Results

An experimental study with a post-test only control group method was conducted to determine the effect of buah merah (Pandanus conoideus Lamk.) extract on retinal layer of diabetic rat models.

3.1. Blood Sugar Profiles in Experimental Animals.

Blood sugar levels were measured at three time points (pre-alloxan, post-alloxan, and pre-termination). The normal range of blood sugar in normal rats was 75-150 mg/dl. in group 1, the average random blood glucose in the study was in the normal range (<150 mg/dl) with p-value of 0.65, which showed no significant difference. meanwhile, for diabetes-induced rats, all four groups had levels >150 mg/dl after alloxan injection. There was a significant difference in random blood glucose levels between diabetes groups 2, 3, 4, and 5, with p-value of <0.05 (

Table 1).

3.2. Photoreceptor Cell Density and Retinal Ganglion Cell Density in Experimental Animals

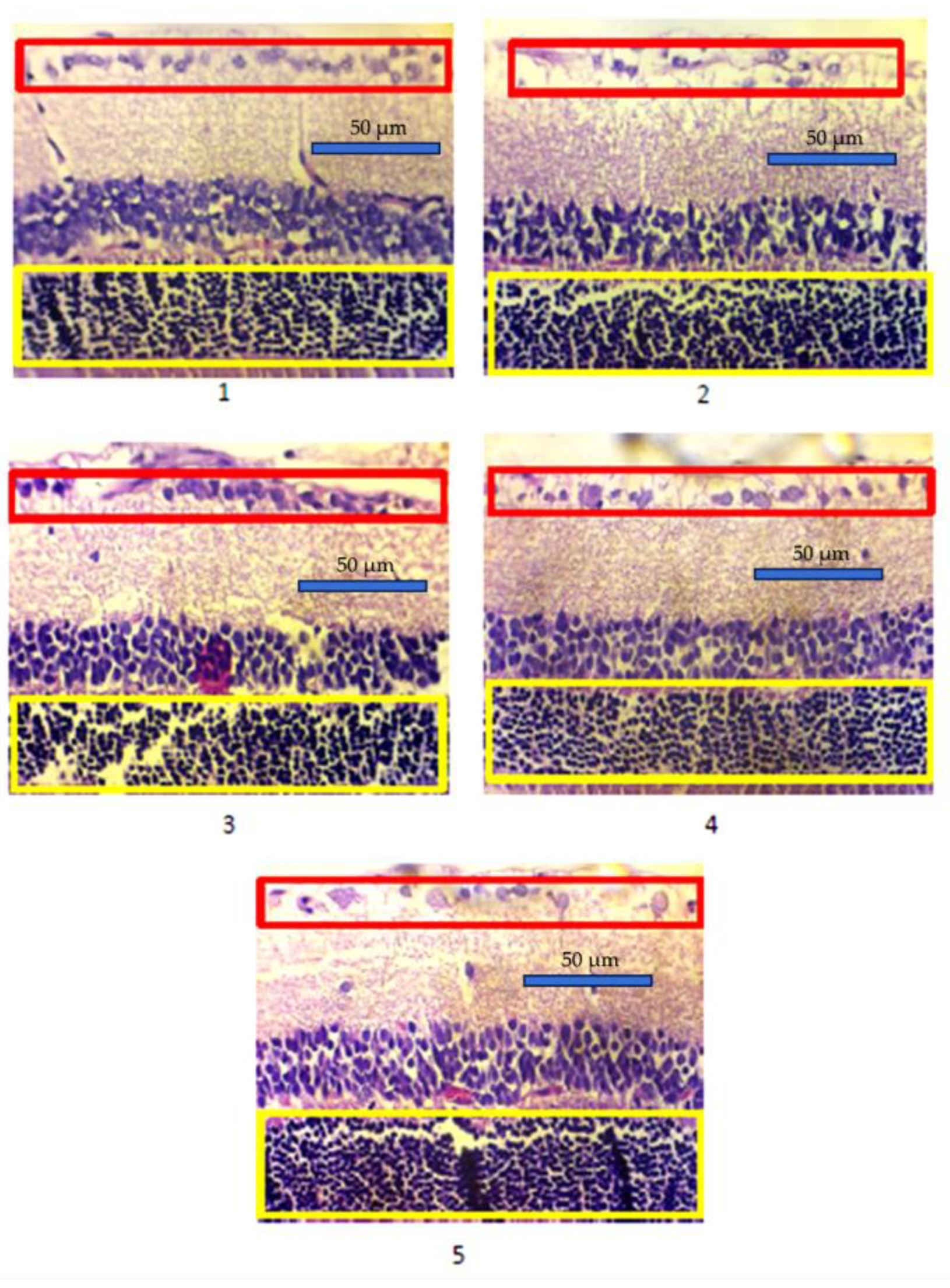

The density assessment of photoreceptor cells in retina was carried out by counting the number of photoreceptor nuclei in the outer nuclear layer. Similarly, the density of ganglion cells was assessed by counting the number of ganglion nuclei averaged over 3 fields of view (approximately 0.045 mm² per fields of view).

Figure 1 shows a comparison of the average photoreceptor and retinal retinal ganglion cell densities of each group. The average density of photoreceptor cells and ganglion cells in the experimental animals was shown in

Table 2. The highest and lowest photoreceptor cell densities were found in group 1 (787.97 ± 18.78) and 2 (572.93 ± 45.40), respectively. In the treatment groups of

buah merah extract, the photoreceptor cell density value in group 3 was close to group 1 (722.52 ± 147.56), while 4 and 5 had similar photoreceptor cell density values (605.03 ± 77.46 and 604.28 ± 75.23). One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) obtained a significant difference between group 4, with p-value of 0.001. The average density of ganglion cells was highest in group 1 (22.77 ± 2.63) and lowest in group 2 (13.20 ± 2.31). The average density of ganglion cells in group 3 was close to the value in group 1 and 2 (18.73 ± 5.61). Similarly, the average density of ganglion cells in groups 4 and 5 were close to group 2 (14.86 ± 3.28 and 13.84 ± 3.13). ANOVA test showed p-value of 0.001, suggesting a significant difference in retinal ganglion cell density between groups.

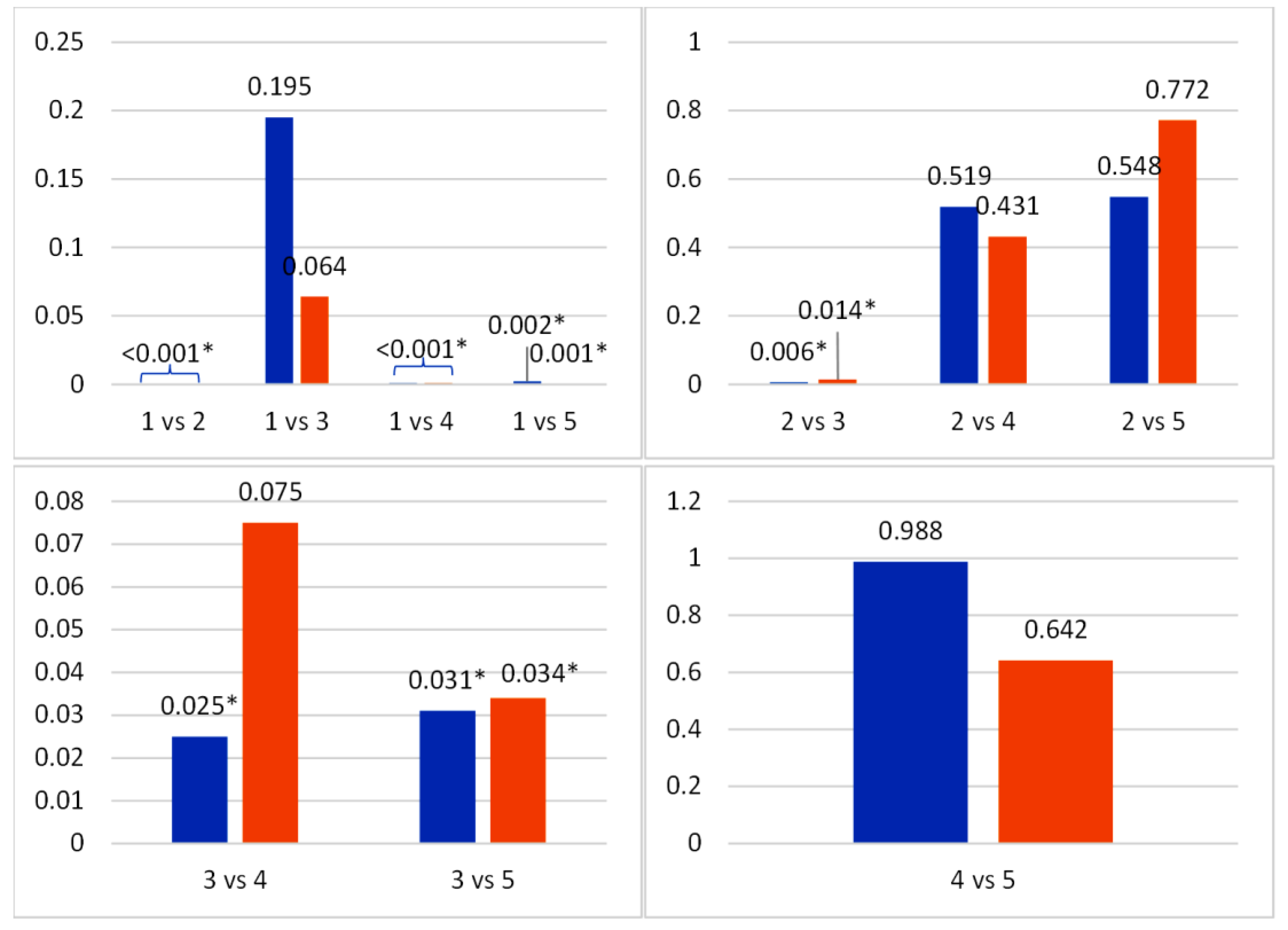

Post-hoc analysis was carried out after obtaining significant results using Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc test, as shown in

Figure 2. The density of photoreceptor cells and ganglion cells between groups 1 and 2 was significantly different, with p-value of <0.001. Furthermore, the density of photoreceptor cells and retinal ganglion cells in group 3 was not statistically significantly different from group 1 (0.195 and 0.064), but was significantly different from group 2 (0.006 and 0.014). These results differ from the test results of groups 4 and 5, where there was a significant difference when compared to group 1, with p-value <0.05 for both photoreceptor cell and retinal ganglion cell densities. This result was not statistically different when compared to group 2, with p-value>0.05 for photoreceptor (0.519 and 0.548) and retinal ganglion cell density (0.431 and 0.772).

3.3. Apoptosis of Photoreceptor Cells and Ganglion Cells in Experimental Animals

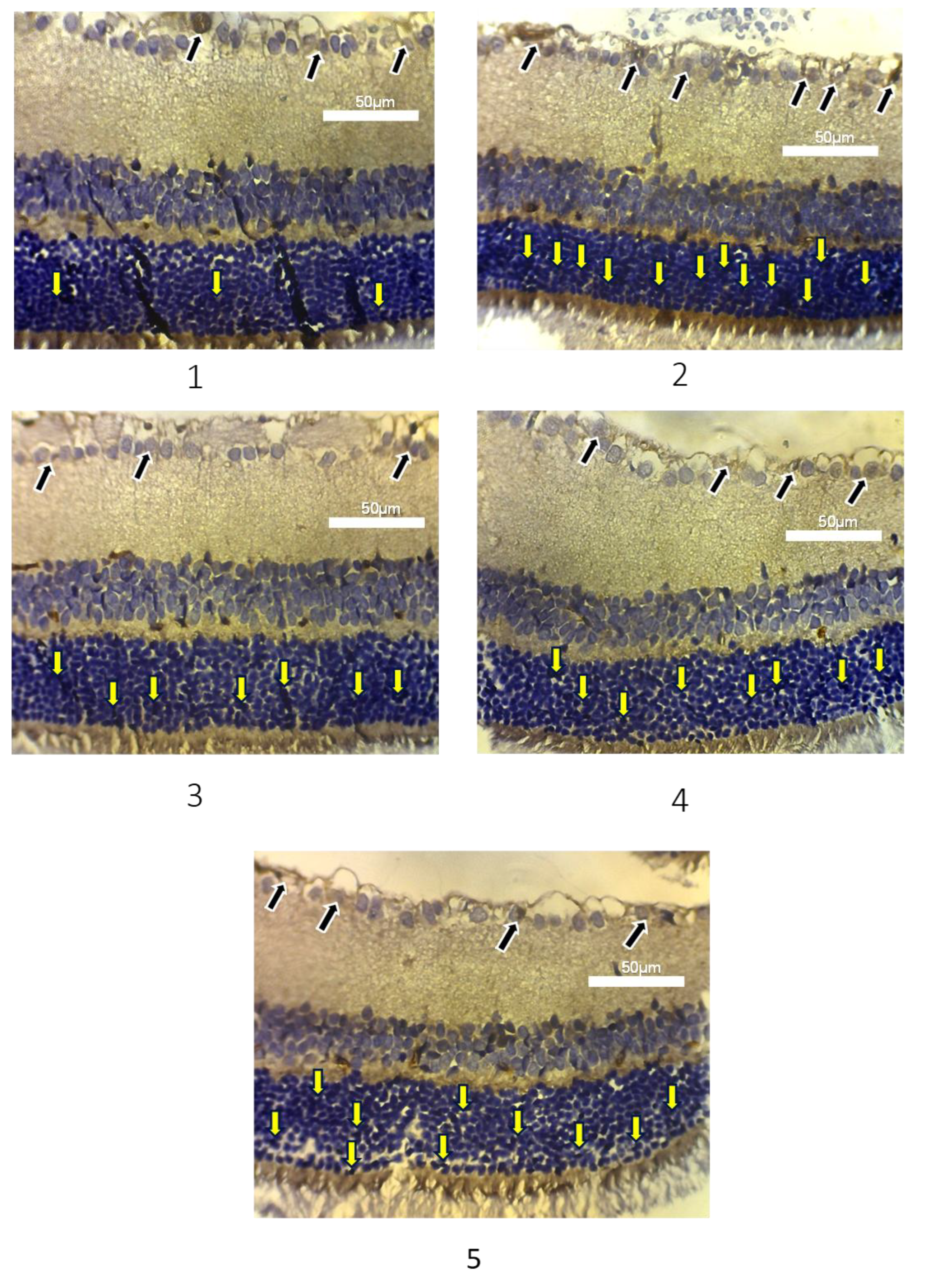

Apoptosis assessment of photoreceptor cells and retinal ganglion cells in experimental animals was measured based on the amount of caspase-3 expression as a marker of cell apoptosis (

Figure 3). The calculation of caspase-3 expression was assessed semi-quantitatively, after counting the photoreceptor cells stained with brown pigment, then categorised into 3 groups, negative, low, and high groups. In

Table 3, group 1 showed the majority of photoreceptor Caspase-3 expression in the negative category (5 out of 6), followed by 1 low category. Group 2 showed the highest Caspase-3 expression in the low category (4 out of 6), with 2 high and none negative. In the treatment groups, group 3 showed an even distribution between the negative and low categories, with none high. Group 4 showed 3 low cases, 2 negative, and 1 high. The majority of Caspase-3 expression in Group 5 was in the low category (5 out of 6), with only 1 negative. The results of the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test showed a difference between photoreceptor Caspase-3 expression in each treatment group, with p-value of 0.020.

In

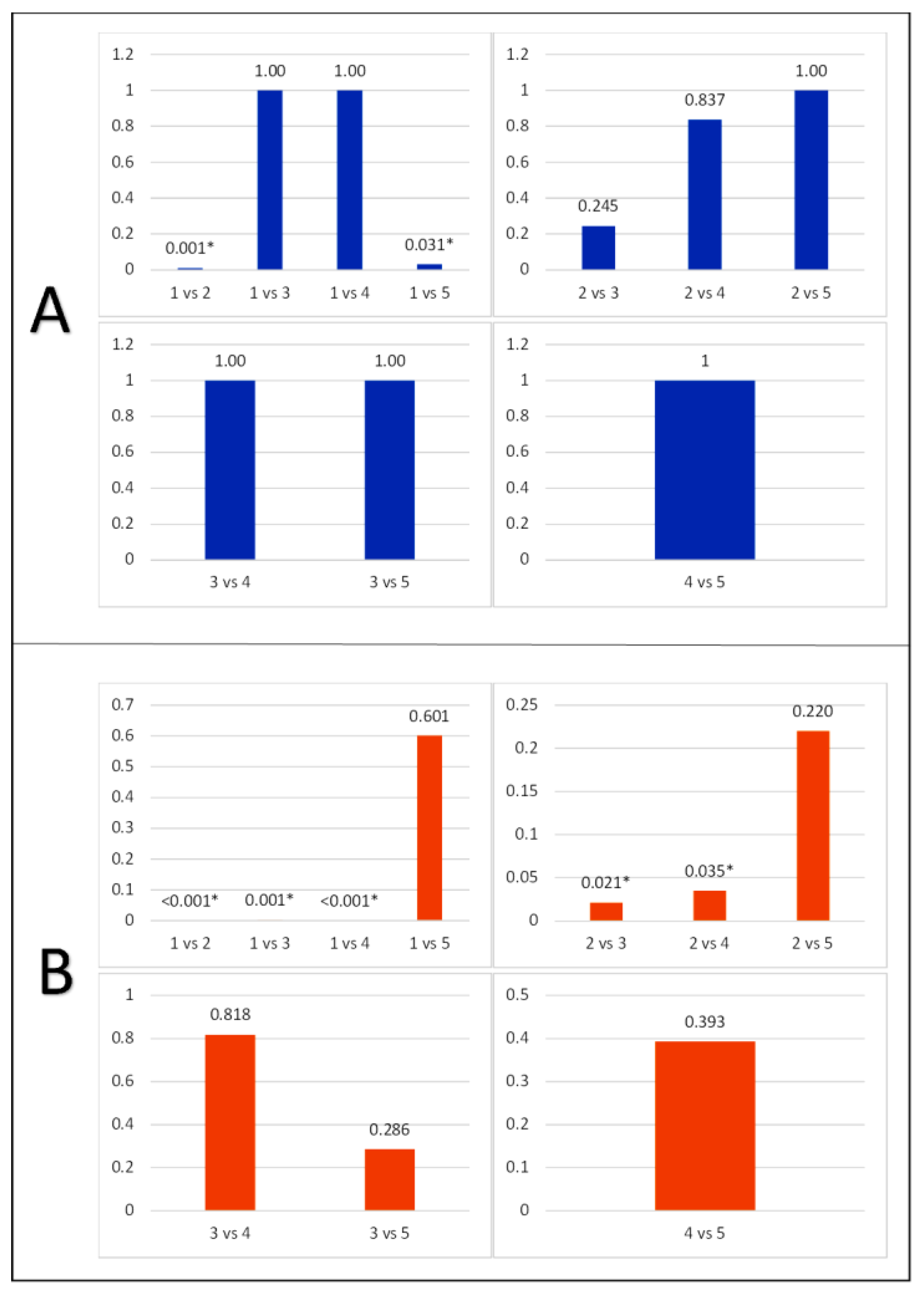

Table 4, Group 1 exhibited the lowest average caspase-3 expression in ganglion cells (23.50 ± 3.50), while Group 2 showed the highest (46.33 ± 6.05). Caspase-3 expression in ganglion cells in group 3, 4, and 5 were 37.50 ± 5.01, 38.33 ± 9.67, and 41.60 ± 4.67 respectively. One Way ANOVA test showed p-value of 0.001, suggested a significant difference in the average caspase-3 expression in each group. A post-hoc test was conducted on the expression of caspase-3 in photoreceptor cells using the Mann-Whitney test (

Figure 4). The result showed that the expression of caspase-3 in photoreceptor cells in groups 1 and 2 was significantly different (0.010). In groups 3, 4, and 5, this expression was not significantly different from 1, with the same p-value (1.000, 1.000, and 0.601). Groups 3 and 4 did not differ significantly from 2, with p-values of 0.245 and 0.837, respectively. However, group 5 showed no significant difference from 2, with p-value of 1.000.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effects of buah merah on the density and apoptosis of photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cells in diabetic rat models. The experimental animals were diabetic Wistar rats with a total of 30 samples, with 1 rat dropping out during the treatment duration. Based on cage-side clinical observations and necropsy findings, the death was not attributable to direct toxicity of buah merah extract, but rather to aggressive behavior and cannibalism, which are well-documented phenomena in rodent colonies. In our study, the deceased rats exhibited external injuries consistent with cannibalistic attack by cage-mates, supporting this as the primary cause of mortality (Balcombe, 2004).

In this study, every 1 ml of buah merah extract is equivalent to a total of 12 mg carotenoids, 10 mg total tocopherol, 1.348 mg alpha tocopherol, and 3.4 mg beta-carotene. The mechanism of apoptosis in DR played an important role in knowing the progression of the disease and is also expected to help in promotive, preventive, and curative efforts. Several studies have shown the role of antioxidants in DR, both synthetically obtained antioxidants and antioxidants derived from natural plants (Garcia-Medina, J. J., 2020). Furthermore, several studies have investigated the effects of natural plants on humans and experimental animals, showing its potential to prevent hyperglycemia and inhibit diabetes-related complications, including nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy. Studies related to the role of natural plants in DR include Annona muricata, Camellia sinensis, Curcuma longa, Ginko biloba, Paenoia suffruticosa, Pinus pinaster, Trigonella foenum graecum, Vaccinium mytillus, and Vitis vinifera (Nazarani et al, 2018).

Buah merah (Pandanus conoideus Lamk.) from Papua is a known natural plant in Indonesia with many health benefits, such as playing a role in diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, malaria, HIV, cancer, and others. The results of this study showed that the weight of the experimental animals differed significantly in the normal group because there was an increase in body weight. Meanwhile, in the group of diabetic rats with treatment in groups 3, 4, and 5, there was an increase in body weight post-Alloxan induction on the third day, followed by a decrease pre-termination. In the diabetic control group, no significant changes in body weight were found in pre-Alloxan, post-Alloxan, and pre-termination. The hyperglycemic condition in diabetic rats during the 2-week treatment duration has caused weight loss. A study by Febriyanti et al. (2011) reported that weight loss in a group of diabetic rats was caused by a lack of insulin. This insulin decreases the glucose entering the cells, causing the metabolism of protein and fat into energy, thereby decreasing the fat reserves in diabetic rats. In contrast to the result, a previous study reported an increase in body weight of diabetic rats given buah merah extract on the fifth day. The nature of alpha tocopherol in buah merah acts as an antioxidant that fights free radicals from unsaturated fatty acids, leading to the protection of fat from ROS (Febriyanti et al., 2011). The potential of buah merah extract in reducing blood sugar levels is related to the function of the active compounds tocopherol, carotene, beta carotene, and ascorbic acid. These compounds inhibit the work of the alpha-glucosidase enzyme, which degrades and converts carbohydrates into glucose. When the function of the enzyme is inhibited, then there is a decrease in blood sugar levels, thereby returning to normal (Khairani, 2023).

In this study, hyperglycemia was found in diabetic group without treatment, and also in buah merah extract treatment for 14 days. This was evident in the average random blood glucose level of >200 mg/dl before rats were terminated. Group 2 (diabetic control) had the highest random blood glucose level at pre-termination, with a value in the random blood glucose category of 418.83 ± 144.51. The diabetic group with treatment had a random blood glucose range of 382.17 ± 49.94 mg/dl, 375.83 ± 66.79mg/dl, and 361.60 ± 62.65 mg/dl before termination. All diabetic groups had random blood glucose levels in the range of 200-400 mg/dl, showing that experimental animals were in severe diabetes mellitus. Therefore, the effect of buah merah extract dose did not succeed in reducing the hyperglycemia of rats. A literature review by Ighodaro et al. (2018) reported the inconsistency factor of alloxan induction material in diabetic rat models. There was a duration of hyperglycemia stability of less than 1 month, and during this period, there was no adequate strength to evaluate the drug (Ighodaro et al., 2018). The result was also consistent with the report of Kowluru et al. (2003) that the effects on retina of diabetic rat models given a combination of antioxidants ascorbic acid 1 g/kg; trolox 500 mg/kg; dl-alpha tocopherol acetate 250 mg/kg; n-acetyl cysteine, 200 mg/kg; beta carotene 45 mg/kg; and selenium, 0.1 mg/kg did not affect the severity of hyperglycemia, glycated hemoglobin levels, and body weight in the treatment group. The study reported that there was still a possibility of a combination of antioxidants being given to diabetic rats that worked through mechanisms other than those related to correcting oxidative stress. For example, alpha tocopherol can normalize the increase in PKC activity induced by diabetes through its effect on the accumulation of diacylglycerol (Kowluru et al, 2003).

Active compounds that play a role in buah merah include carotenoids, total tocopherol, beta-carotene, B-cryptoxanthin, alpha tocopherol, oleic acid, linoleic acid, and others. Some of these compounds have been known to be beneficial in DR. Carotenoids are a large group of organic and lipophilic pigments, produced by plants, algae, and some bacteria and fungi, used in the treatment of Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS) at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg beta-carotene. A literature review study showed that carotenoids played a role in the mechanism of ROS, inflammation, neovascularization, and neurodegeneration in both diabetes mellitus patients and diabetic test animals. Furthermore, a dose of carotenoids in the form of astaxanthin of 3 mg/kgBW in rats significantly protects the retina in inhibiting neurodegenerative diseases (Yeh PT, et al, 2016; Fathalipour M et al, 2020). The effect of alpha tocopherol in diabetic rat model by Ichsan et al., was reported to function as a retinoprotective agent when given a single dose of 15 mg for 14 days (pre and post alloxan induction) obtained an average photoreceptor cell density of 752 ± 190 cells and a retinal ganglion cell density of 27 ± 2cells (Ichsan et al, 2022).

The result of this study showed a retinoprotective effect on photoreceptor cells and ganglion cells in treatment group 3. This group was given 1 ml of buah merah extract with a combination of active compounds of 12 mg total carotenoids, 10 mg tocopherol, 3.581 mg beta-carotene, 1.460 mg B-cryptoxanthin, and 1.368 mg alpha tocopherol. A previous study on diabetic rats given a combination of antioxidants also showed an antioxidant effect that protected retina of diabetic rats (Kowluru et al., 2013). In various studies that assessed retinal layer using OCT, the inner retinal layer, including nerve fibers, ganglion cells, and the plexiform experienced a decrease along with the duration of RD incident. Caspase-3 is an executor that has been widely examined in relation to the apoptosis process in the neural retina.

Previous studies have reported that red fruit oil supplementation may not always provide protective effects, as seen in experimental models where it failed to prevent oxidative stress, raising concerns about its potential limitations and safety profile; however, in our study, no overt adverse effects were observed during the treatment period, with animals showing no behavioral changes, weight loss, or gastrointestinal symptoms, suggesting that the supplementation was well tolerated under our experimental conditions (Handayani, 2013).

The unique bioactive components of this extract—particularly β-cryptoxanthin, tocopherol, and polyunsaturated fatty acids—are known to modulate oxidative stress and apoptotic signaling in retinal tissue. Specifically, these compounds may inhibit the caspase-3 activation pathway, reducing DNA fragmentation and apoptotic cell death among photoreceptor and ganglion cells. In addition, the antioxidant properties of β-cryptoxanthin and tocopherol contribute to stabilization of mitochondrial membranes and preservation of retinal neuron integrity under hyperglycemic conditions. This mechanistic explanation aligns with recent studies demonstrating that carotenoid-rich and antioxidant extracts can suppress apoptosis through regulation of Bcl-2/Bax expression and attenuation of ROS-mediated damage in diabetic retina models (see updated references. These findings suggest that Pandanus conoideus extract exerts a dual protective role—both anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic—which may contribute to the preservation of retinal structure and function in diabetic conditions (Khairani,2023).

In this study, Alloxan-induced diabetic rats showed that apoptosis had occurred, evidenced by the expression of caspase-3 in photoreceptor cells and ganglion cells in diabetic rat model for approximately 14 days of observation. This was also found in a study conducted on STZ-induced diabetic rat model to assess apoptosis that occurred starting from 1 week of observation. The result showed that the comparison of caspase-3 expression in photoreceptor cells in treatment groups 3, 4, and 5 was not significantly different between the normal and diabetic groups. Groups 3 and 4 affected the photoreceptor cells of experimental rats, with caspase-3 expression values in photoreceptor cells similar to normal controls, while group 5 had no effect. Caspase-3 expression in ganglion cells showed that all treatment groups had different values from the normal control group. Therefore, at retinal ganglion cell level, the effect of this buah merah extract did not inhibit retinal ganglion cell apoptosis. The administration of buah merah extract containing alpha tocopherol and carotenoids has the potential to protect photoreceptor cells but not ganglion cells. Another study explained the effect of alpha tocopherol on a group of rats given a dose of 15 mg alpha, getting closer to the normal group's caspase-3 expression value (Ichsan et al., 2022). A study conducted for 21 days showed that the dose range of buah merah extract should represent the minimum and maximum with the same interval. The minimum dose in experimental rats was 4 g/kgBW and the maximum was 68 g/kgBW Another study showed the hypoglycemic effect of buah merah extract in Alloxan-induced diabetic rats (14 mg, IV). The result showed that doses ranging from 0.12 ml to 0.48 ml were safe in experimental animals, with 0.12 ml exhibiting a significant hypoglycemic effect (Febriyanti et al, 2011).

Kaur N. et al. (2017). reported that doses of 1.35 ml/kg BW and 5.4 ml/kg BW did not impair kidney function in STZ-induced rats. Meanwhile, reports on diabetic rats given 15 mg/kgBW of alpha tocopherol compounds have shown a retinoprotective effect (Ichsan et al, 2022). In this study, the dose range given was 1 ml - 2 ml. The results showed that a 1 ml dose of buah merah extract, containing 12 mg of total carotenoids, 10 mg of total tocopherol, 1.348 mg of alpha-tocopherol, and 3.4 mg of beta-carotene, protected photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cells from apoptosis in diabetic rats. An active compound in natural plants can act as an antioxidant when it fights the effects of free radicals on a disease (Tabatabaei, 2019). However, there is still controversy regarding the existence of a pro-oxidant effect. In this case, when an active compound is given in excessive amounts, the free radical process increases. According to Black Hormer et al. (2020), the prooxidant effects of alpha tocopherol and beta carotene lead to increased ROS in vitro studies. Another report showed that the administration of buah merah oil doses could cause increased ROS in experimental animals due to the combined work of several antioxidants as pro-oxidants by inducing the Fenton reaction and the Haber-Weiss reaction. This increases the production of hydroxyl radicals and reduces antioxidant levels in the blood (Handayani, 2013). A study by de Oliveira, B.F. (2013) found that a combination of antioxidants, consisting of 1.6 μM ascorbic acid, 0.82 μM alpha-tocopherol, and 0.016 μM beta-carotene, induced free radical production in vitro in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients aged 20-39 years. This may be due to the doses exceeding the optimal levels of 12 mg total carotenoids, 10 mg total tocopherol, 1.348 mg alpha-tocopherol, and 3.4 mg beta-carotene, rendering the 1.5 ml and 2 ml doses ineffective in protecting retinal cells in diabetic rats (Kalariya, 2008).

Safety factors will remain a major concern in the use of natural plants as supplements for DR. Therefore, the advantages of this study include relevance to clinical situations related to the prevention and treatment of DR. The results are expected to have good potential clinical impacts. This study used a detailed and methodological experimental design to evaluate the effects of buah merah extract on retina of diabetic rat model, including clear control and treatment groups. A histological analysis was used to evaluate cellular changes in retina, and important qualitative and quantitative data were provided. The number of experimental animal samples was sufficient to provide results that could be analysed statistically. However, there are limitations, including the use of experimental rats as diabetic model cannot fully represent the pathomechanism of DR in humans. Although animal models are useful, the results of this study should be applied with caution to human clinical conditions. The 14-day treatment duration may also be a limitation because the observation of long-term therapeutic effects of buah merah extract is not yet fully understood. The assessment of density and apoptosis depends significantly on histopathological methods that may still override molecular or biochemical data.

There has been increasing interest in the field of study related to natural plants that are eventually formulated as supplements. Regarding side effects and drug interactions, Zhao et al. reported that some plants did not show toxic effects in vivo or in vitro. However, cellular and animal model studies may not fully predict toxicological outcomes in humans (Zhao Yuxuan, 2024). In our study, the application of buah merah extract represents a groundbreaking step in expanding the scientific repertoire of ocular therapeutics. By focusing on its protective effects against retinal cell apoptosis, particularly in photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells, this research provides novel insights into its role as a potential neuroprotective and cytoprotective agent in the eye. Such findings not only validate the empirical use of buah merah in traditional medicine but also open a new frontier in ophthalmic research, underscoring its promise as a natural intervention for vision preservation and retinal health. Future studies should explore the possible side effects of natural or herbal plants on the human body to help inhibit the development of DR.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides an overview of the effects of administering buah merah extract to diabetic rat model. The results show that administering buah merah extract maintains photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cell density in diabetic rat model. However, it does not inhibit apoptosis in either retinal photoreceptors or ganglion cells. This result proves that our intention was not to model the full clinical spectrum of diabetic retinopathy (which evolves over weeks to months) but to interrogate early retinal stress and apoptosis following hyperglycemia. The results of this study show that natural plant ingredients, such as buah merah, have the potential to be retinoprotective in diabetic rat model, even though hyperglycemia has not been resolved. There is a possibility that antioxidant effect of buah merah extract may include additional pathways beyond inhibiting oxidative stress in DR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.S. and A.M.I.; methodology, BD.; software, S.L.; validation, H.S.M., A.M.I. and BD.; formal analysis, S.W.S.; investigation, S.W.S.; resources, I.C.I.; data curation, A.A.Z and I.C.I.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.S, A.M.I, H.S.M, BD.; writing—review and editing, A.M.I, I.C.I.; visualization, A.A.Z; supervision, S.L, A.A.Z, BD, H.S.M, A.M.I.; project administration, I.C.I.; funding acquisition, S.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has no funding to be disclosed.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethical Committee of Hasanuddin University No. 92/ UN.4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data were included in this main manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akbarzadeh, A. , Norouzian, D., Mehrabi, M.R., Jamshidi, S.H, Farhangi, A., Verdi, A.A., et al., 2007. Induction of diabetes by Streptozotocin in rats. Indian journal of clinical biochemistry : IJCB, 22(2), 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Anil, Rajendran., 2012. Routine Histotechniques, Staining and Notes on Immunohistochemistry. Elsevier India P Ltd.

- Balcombe, J.P. , Barnard, N.D., and Sandusky, C., 2004. Laboratory routines cause animal stress. Contemporary topics in laboratory animal science, 43(6), 42–51.

- Baptista, S. , Paniagua, P. and Tavares, A., 2010. Antioxidants in the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy – A Review, Journal of Diabetes & Metabolism, 1(3), pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Black, H. S. , Boehm, F., Edge, R., and Truscott, T.G., 2020. The Benefits and Risks of Certain Dietary Carotenoids that Exhibit both Anti- and Pro- Oxidative Mechanisms-A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(3), 264. [CrossRef]

- Chiew, Y. , Tan, S., Ahmad, B., Khor, S. E., and Abdul Kadir, K., 2021. Tocotrienol-rich vitamin E from palm oil (Tocovid) and its effects in diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: a pilot phase II clinical trial. Asian Journal of Ophthalmology, 17(4), 375-399. [CrossRef]

- deOliveira, B.F. , Costa, D.C., Nogueira-Machado, J.A. and Chaves, M.M., 2013. β-Carotene, α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid: differential profile of antioxidant, inflammatory status and regulation of gene expression in human mononuclear cells of diabetic donors. Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 29: 636-645. [CrossRef]

- Galli, F. , Vigna, L., Tinelli, C., Caiazza, A., Racca, V. and Passoni, A., 2022. Vitamin E (Alpha-Tocopherol) Metabolism and Nutrition in Chronic Kidney Disease, Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 11(5). [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Medina, J.J. , Rubio-Velazquez, E., Foulquie-Moreno, E., Casaroli- Marano, R.P., Pinazo-Duran, M.D., Zanon-Moreno,V., et al., 2020. Update on the Effects of Antioxidants on Diabetic Retinopathy: In Vitro Experiments, Animal Studies and Clinical Trials. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(6), 561. [CrossRef]

- Fathalipour, M. , Fathalipour, H., Safa, O., Nowrouzi-Sohrabi, P., Mirkhani, H., Hassanipour, S., 2020. The Therapeutic Role of Carotenoids in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Jul 3;13:2347-2358. [CrossRef]

- Febriyanti, R. , 2011. Pengaruh Pemberian Ekstrak Buah merah (Pandanus Conoideus) Terhadap Kadar Glukosa Darah Tikus Putih (Rattus Norvegicus) Diabetik." Jurnal Peternakan UIN Sultan Syarif Kasim, vol. 8, no. 1, 1 Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, D.J. , Yego, E.C., and Mohr, S., 2013. Modes of Retinal Cell Death in Diabetic Retinopathy. Journal of clinical & experimental ophthalmology, 4(5), 298. [CrossRef]

- Handayani, M.D.N. , Soekarno, P.A., and Wanandi, S.I., 2013. Red fruit oil supplementation fails to prevent oxidative stress in rats. Universa Medicina, 32(2), 86–91. [CrossRef]

- Ichsan, A.M. , Bukhari, A., Lallo, S., Miskad, U.A., Dzuhry, A.A., Islam, I. C., et al., 2022. Effect of retinol and α-tocopherol supplementation on photoreceptor and retinal retinal ganglion cell apoptosis in diabetic rats model. International journal of retina and vitreous, 8(1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O. M. , Adeosun, A. M., and Akinloye, O. A., 2017. Alloxan-induced diabetes, a common model for evaluating the glycemic-control potential of therapeutic compounds and plants extracts in experimental studies. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 53(6), 365–374. [CrossRef]

- Kalariya, N.M. , Ramana, K.V., Srivastava, S.K., and van Kuijk, F.J., 2008. Carotenoid derived aldehydes-induced oxidative stress causes apoptotic cell death in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Experimental eye research, 86(1), 70–80. [CrossRef]

- Khairani, A.C. , Wijayanti, T., and Widodo, G.P., 2023. Antihyperglycemic Activity of Red Fruit Oil (Pandanus conoideus Lam) on Improving Kidney Function in STZ- NA-Induced Nephropathy Rats. [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A. , and Koppolu, P., 2002. Diabetes-induced activation of caspase-3 in retina: effect of antioxidant therapy. Free radical research, 36(9), 993–999. [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A. , Koppolu, P., Chakrabarti, S., and Chen, S. 2003. Diabetes- induced activation of nuclear transcriptional factor in the retina, and its inhibition by antioxidants. Free radical research, 37(11), 1169–1180. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Navpreet. (2017). Role of Nicotinamide in Streptozotocin Induced Diabetes in Animal Models. Journal of Endocrinology and Thyroid Research. 2. 10.19080/JETR.2017.02.555577.

- Lechner, J. , O’Leary, O.E. and Stitt, A.W., 2017. The pathology associated with diabetic retinopathy, Vision Research, 139, pp. 7–14. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T. , Gayton, E.L., Beulens, J.W., Flanagan, D.W., and Adler, A.I. 2010. Micronutrients and diabetic retinopathy a systematic review. Ophthalmology, 117(1), 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Mitachi, K. , Ariake, K., Shima, H. et al. Novel candidate factors predicting the effect of S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy of pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtiningrum, M. , Sarungallo, Z.L. and Mawikere, N.L. (2011) 'The exploration and diversity of red fruit (Pandanus conoideus L.) from Papua based on its physical characteristics and chemical composition', Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity, 13(3), pp. 124–129. [CrossRef]

- Nazarian-Samani, Z. , Sewell, R. D. E., Lorigooini, Z., & Rafieian-Kopaei, M. (2018). Medicinal Plants with Multiple Effects on Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: a Systematic Review. Current diabetes reports, 18(10), 72. [CrossRef]

- Ng, S. (2020) 'Pharmacology and Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin E: Nanoformulations to Enhance Bioavailability', Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, pp. 9961–9974.

- Oshitari, T. (2023). Neurovascular Cell Death and Therapeutic Strategies for Diabetic Retinopathy. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(16), 12919. [CrossRef]

- Ruamviboonsuk, V. , & Grzybowski, A.,2022. The Roles of Vitamins in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Narrative Review. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(21), 6490. [CrossRef]

- Sasongko, M.B. , Widyaputri, F., Agni, A.N., Wardhana, F.S., Hikmah, I., Adisasmita, A., Soeatmadji, D.W. and Lestari, Y.D. (2017) 'Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Blindness in Indonesian Adults With Type 2 Diabetes', American Journal of Ophthalmology, 181, pp. 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei-Malazy, O. , Ardeshirlarijani, E., Namazi, N., Nikfar, S., Jalili, R. B., and Larijani, B., 2019. Dietary antioxidative supplements and diabetic retinopathy; a systematic review. Journal of diabetes and metabolic disorders, 18(2), 705–716. [CrossRef]

- Yeh PT, Huang HW, Yang CM, Yang WS, Yang CH. 2016. Astaxanthin Inhibits Expression of Retinal Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Mediators in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 14;11(1):e0146438. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. , Chen, Y., and Yan, N., 2024. The role of natural products in diabetic retinopathy. Biomedicines, 12(6), 1138. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).