1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the most common microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus and remains a leading cause of vision impairment and blindness worldwide. As the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise, so does the burden of DR, affecting millions of individuals globally.

The low oxygen tension of the retina [

1], its high metabolic demands [

2], and the complex organization of the blood-retinal barrier [

3] make the retina one of the first systems affected in diabetes [

4]. The disease is characterized by progressive damage to the retinal microvasculature, leading to capillary occlusion, ischemia, and increased vascular permeability. These pathological changes contribute to two major sight-threatening complications: proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and diabetic macular edema (DME) [

5].

The development of DME is driven by complex and multifactorial mechanisms, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF, a key mediator, enhances vascular permeability, leading to fluid accumulation in the retina and the progression of macular edema [

6]. Consequently, therapies targeting VEGF have become central to managing this condition.

Over the last two decades, significant advancements have been made in the management of DME. Intravitreal pharmacological therapies, particularly anti-VEGF agents such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab, aflibercept, and faricimab, have transformed treatment paradigms. These therapies have demonstrated superior visual outcomes compared to traditional laser therapy [

7,

8]. Anti-VEGF medications act by inhibiting VEGF-induced vascular permeability, effectively reducing macular edema and improving vision. Nevertheless, frequent intravitreal injections and variability in patient responses present ongoing challenges.

For patients who do not respond adequately to anti-VEGF therapy, corticosteroid implants such as dexamethasone (Ozurdex

®) and fluocinolone acetonide (Iluvien

®) provide an alternative approach by modulating inflammatory pathways and stabilizing the blood-retinal barrier [

7,

9]. However, their use is associated with potential ocular side effects, such as cataract formation and elevated intraocular pressure [

10].

In addition to conventional treatments, there is growing interest in the influence of systemic and nutritional factors on DME management. Nutritional supplements—such as antioxidants (vitamins C and E, lutein, and zeaxanthin), omega-3 fatty acids, fenofibric acid, and vitamin D—have been explored for their potential to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, which play critical roles in DME progression [

9,

11,

12,

13]. While some studies suggest that dietary modifications and targeted supplementation may support retinal health, more extensive clinical trials are required to confirm their effectiveness in managing DME [

14].

This study investigates the potential role of a combination of Bromelain (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg) in managing diabetic retinopathy and DME, focusing on their anti-inflammatory and vascular-stabilizing effects.

The subsequent sections present clinical outcomes and retinal morphological changes observed during this study.

2. Materials and Methods

Forty eyes of forty patients with type 2 diabetes and cystoid diabetic macular edema, treated with a maintenance protocol based on anti-VEGF, were randomly selected and enrolled in this prospective case-control study. Only eyes that had completed the loading phase and were on a maintenance protocol based on bi-monthly injections were included. All patients underwent a complete ophthalmological examination, including BCVA, anterior segment slit-lamp and fundus examination, measurement of central macular thickness (CMT), and fundus photography by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) at the U.O.C. Ophthalmology, Polo Pontino-Ospedale A. Fiorini, Terracina (LT), Italy.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later revisions.

The severity of DR was categorized based on the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema Severity Scale. Inclusion criteria encompassed: (a) men and women aged 60–90 years; (b) type 2 diabetes managed with oral or subcutaneous anti-hyperglycemic therapy; (c) diabetes duration between 5 and 15 years; (d) non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, characterized by the presence of microaneurysms; (e) a confirmed diagnosis of diabetes mellitus per American Diabetes Association criteria; (f) best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) ≥ 20/50 on ETDRS charts; (g) no systemic diabetes-related complications; (h) presence of cystoid center-involving DME, patients after the loading phase; (i) CMT between 200 and 600 µm.

Exclusion criteria included: (a) proliferative diabetic retinopathy; (b) history of hypersensitivity to study medications; (c) macular pathologies unrelated to diabetes (e.g., foveal scars, exudative macular degeneration, uveitis, or epiretinal membranes); (d) less than 20 weeks of intravitreal treatment; (e) more than 36 weeks of intravitreal treatment; (f) cataract surgery within 12 months; (g) prior ocular surgeries within 12 months. Mild DME was defined as central macular thickness (CMT) below 400 µm, following the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE; accessed January 3, 2025).

The sample size was calculated using MedCalc version 10.0 (MedCalc, Ostend, Mariakerke, Belgium). The minimum sample size requirement for a t-test with an alpha level of 0.05, and a power of 0.8, was calculated to be 20 for each group.

The study design chosen was a cross-over model in which all patients received the drug and the washout period. After a two-month washout corresponding to the interval between IVT administrations, Group “A” received one pill twice a day for two months, and after two months, all examinations were repeated. Group “B,” after the washout, was only monitored without drug administration until the next IVT.

After two months and the IVT administration, groups were crossed according to our clinical design to reduce intraindividual variability. Patients in Group “A” were only monitored, while patients in Group “B” were treated with the same regimen for two months. At the end of the study, data were further divided into two groups: the treatment group (20 eyes) and the control group (20 eyes). The treatment group included data from patients during the period when they received a dietary supplement (Redemase 500®, Ophthagon Srl, Rome, Italy) containing Bromelain (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg) at a dosage of two tablets per day before meals continuously over a 4-month period. The control group data were collected during the period in which our sample patients were only observed during anti-VEGF maintenance therapy.

Ophthalmic assessments—including BCVA, anterior segment slit-lamp examination, fundus examination, CMT measurement, and fundus photography—were performed at baseline and at two- and four-month intervals using a spectral-domain OCT instrument (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering).

Within the treatment group, a sub-analysis was conducted to evaluate therapy response. Good responders were defined as those showing a reduction of over 30 µm in CMT, while poor responders were identified as those with unchanged or increased CMT compared to baseline.

Scanning Protocol

One eye per patient was included in the analysis, and the highest-quality scans were selected for evaluation. The OCT acquisition protocol consisted of a macular line scan and a 6 × 6 mm macular cube, centered on the fovea. All scans were reviewed by an expert ophthalmologist (F.M.) to ensure proper segmentation accuracy.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism software, version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as median values with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. The normality of the data was assessed using the Anderson–Darling and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Depending on the data distribution, a Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare variables. To evaluate changes in CMT and BCVA over time, a mixed-design ANOVA was performed. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 40 eyes (16 males, 24 females; mean age 70 ± 6.77 years) with a diagnosis of mild non-proliferative DR and focal edema were included in the study and divided in two groups: treatment group (group A, n = 20 eyes) and control group (group B, n = 20 eyes). The main cohort data are summarized in

Table 1.

At the baseline examination, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of demographics and ocular parameters (BCVA, CMT).

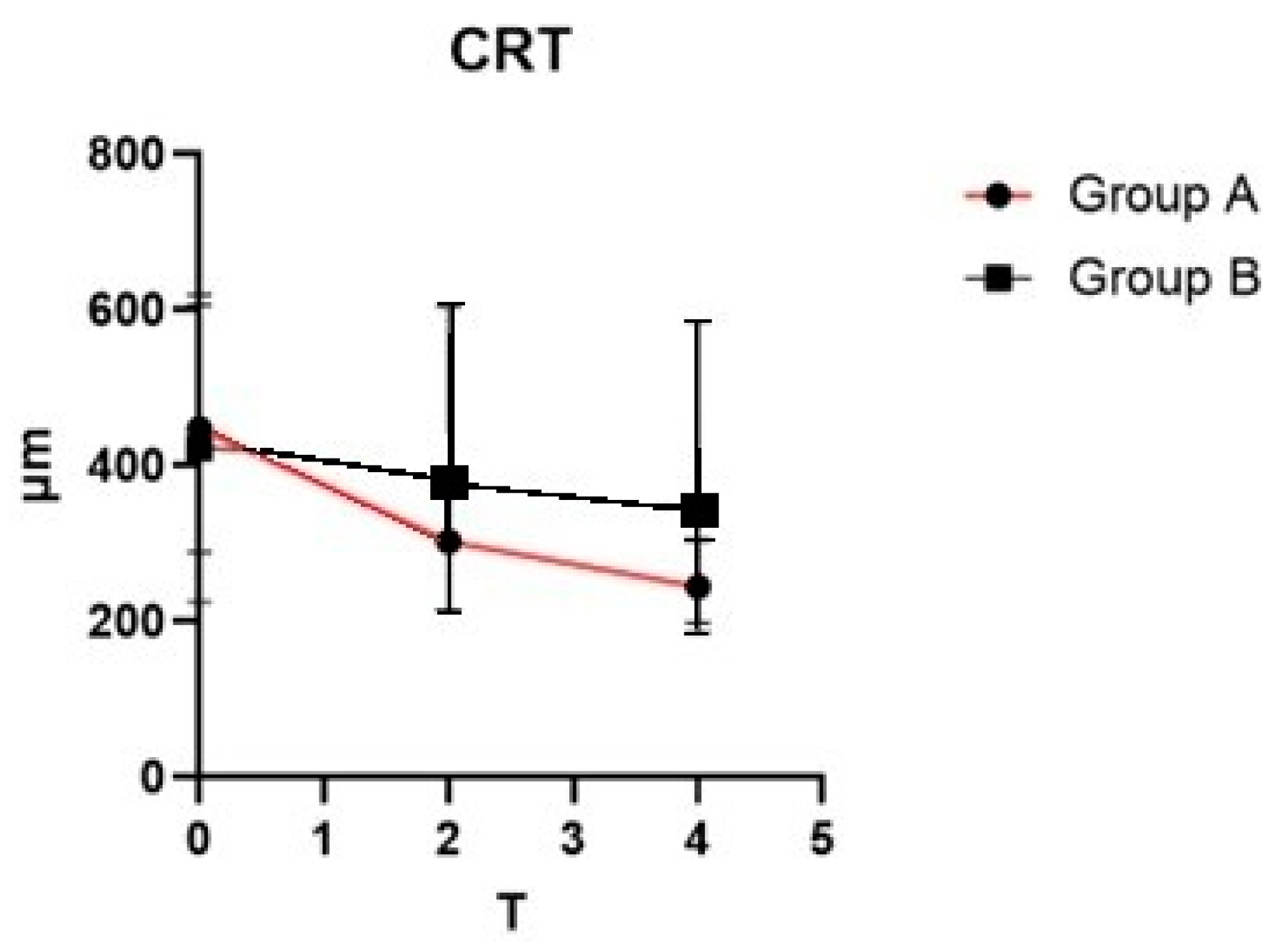

The results of the mixed-model ANOVA indicated that the interaction between time and treatment on the CMT was significant, with F (2, 114) = 5,645 (p = 0,0046). There was a reduction in CMT in eyes of group A (

Figure 1). Specifically, during each follow-up time point, it was observed that group B showed a very slight downward trend in CMT dimension.

Conversely, the interaction between time and treatment was not significant in BCVA with F (2, 114) = 0.929 (p = 0.3976).

At the ophthalmic evaluation of 40 eyes analyzed, 21 were pseudophakic (group A: 11 eyes; group B: 10 eyes), 10 had an N2C3 cataract (group A: 5 eyes; group B: 5 eyes), 5 had an N3C2 cataract (group A: 3 eyes; group B: 2 eyes) and 4 had an N4C3 cataract (group A: 2 eyes; group B: 2 eyes). There were no documented adverse effects observed in group A, which received the oral administration of fixed combination of Bromelin (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg). At each follow-up, fundus examination was performed, and no vitreoretinal interface abnormalities were detected.

4. Discussion

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is a major cause of vision loss in patients with diabetes, resulting from the accumulation of fluid in the macula due to breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier. DME often occurs in conjunction with diabetic retinopathy and can lead to significant visual impairment if left untreated [

5]. Current treatment strategies primarily involve intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, which aim to reduce retinal edema and improve visual acuity. Additionally, other treatment options, such as intravitreal corticosteroids and laser photocoagulation, are commonly used [

8].

OCT, in combination with visual acuity measurements, guides both the diagnosis and therapy of diabetic macular edema [

15]. Promising OCT-based biomarkers correlated with possible visual recovery and CMT include the presence and quantity of intraretinal fluid (IRF), subretinal fluid (SRF), the integrity of the external limiting membrane (ELM), the number of hyperreflective foci (HRF) [

16], disorganization of retinal internal layers (DRIL) where no demarcation can be identified between the ganglion cell layer, the inner plexiform layer, the inner nuclear layer, and the outer plexiform layer [

17], and the percentage of disruption of the IS/OS layer of the photoreceptor [

18].

The pathogenesis and progression of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema are not only due to a vascular phenomenon with rupture of the hematoretinal barrier but also to an alteration of the neurovascular unit [

19].

Neurovascular units are defined as neurons (ganglion cells, amacrine cells, horizontal cells, and bipolar cells), glial cells (Müller cells, microglia, and astrocytes), and vessels (endothelial cells, pericytes, and basement membrane). Among the microglia, two subtypes are distinguished: a pro-inflammatory one (M1) and an anti-inflammatory one (M2) [

20].

Under conditions of hyperglycaemic stress, microglia switch to the proinflammatory M1 stage, with production of TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and VEGF via the ERK1/2-NFkb signaling pathway [

21,

22]. Through paracrine mediation, Müller cells and astrocytes are also activated and amplify inflammatory responses by producing proinflammatory cytokines [

23].

This new knowledge of neuroinflammation in diabetic macular edema has brought increasing interest in the use of oral supplements or adjunctive therapies to help manage DME, particularly in reducing inflammation and improving vascular health [

9]. These therapies aim to complement primary treatments, potentially improving outcomes between injections or reducing the frequency of intravitreal injections.

Various natural compounds have been studied for their potential benefits in managing DME, including flavonoids, antioxidants, and enzymes such as bromelain, all of which have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and edematous properties [

11,

12,

13].

Our study focused on the potential role of a fixed combination of Bromelain (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg) in the management of cystoid center-involving DME.

Bromelain, a proteolytic enzyme extracted from pineapple (Ananas comosus), has been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, and fibrinolytic activities. These properties are particularly relevant in DME, where chronic inflammation and microvascular dysfunction contribute to disease progression. Bromelain has demonstrated the ability to inhibit the Raf-1/extracellular-regulated-kinase-(ERK-) 2 pathways of T cells, which are involved in VEGF production [

24]. Bromelain has also been reported to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukins, which are implicated in retinal vascular permeability [

25]. Furthermore, bromelain’s ability to reduce blood viscosity and platelet aggregation may help improve retinal microcirculation in neurovascular units, thereby decreasing ischemic damage in diabetic retinopathy [

26,

27].

Diosmin, a flavonoid commonly derived from citrus fruits, is widely used in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency due to its vasoprotective and anti-edema effects. This flavonoid is effective in protecting tight junctions, maintaining blood-retinal barrier integrity, and reducing retinal vascular permeability during retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury [

28]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that diosmin exerts antioxidant effects, protecting retinal endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced damage [

29]. Additionally, its ability to modulate VEGF expression and inflammatory cytokine levels suggests a possible synergistic role alongside existing anti-VEGF therapies in controlling DME progression [

30,

31].

In our study, we found that patients who received a fixed combination of Bromelain (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg) demonstrated an improvement in retinal edema and a reduction in CMT. The supplement was taken continuously over a 4-month period while patients were undergoing maintenance anti-VEGF treatment. However, despite these positive changes in retinal morphology, no significant improvement in visual acuity was observed. This result is consistent with previous studies suggesting that although reductions in retinal edema are often seen with adjunctive therapies, improvements in visual acuity may not always follow, particularly in patients with chronic or severe DME [

32,

33,

34]. It is possible that the resolution of edema does not immediately translate into functional visual recovery, which may be influenced by factors such as retinal ischemia or permanent damage to the retinal structure [

35,

36].

Nonetheless, the findings from our study suggest that a fixed combination of Bromelain (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg) may play an important role in managing DME by helping to control retinal edema between anti-VEGF injections. This could provide a more manageable treatment regimen for patients by ensuring better control of edema during the inter-injection period. Such an approach could lead to decreased healthcare costs, lower patient burden, and fewer clinic visits, which may improve adherence to treatment. Furthermore, adjunctive therapies like this combination may offer a cost-effective means of enhancing patient outcomes while reducing the overall healthcare burden associated with DME management.

Our study also raises the possibility that adjunctive treatments with a fixed combination of Bromelain (250 mg) and Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus (250 mg) may offer a beneficial strategy for managing DME in a more comprehensive, cost-effective manner, potentially easing the burden on both patients and healthcare systems. While further research is needed to confirm the long-term benefits and safety of such supplements, our results provide a basis for exploring their role as part of a broader DME management strategy.

The limitations of the study include sample size, lack of long-term follow-up, and absence of randomization.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest a possible synergistic action of the orally administered combination of Bromelain 250 mg and 250 mg Diosmin mcgSMIN Plus with anti-VEGF intravitreal maintenance therapy in patients affected by cystoid center-involving DME. This combination may provide a more manageable treatment regimen for patients by ensuring better control of edema during the inter-injection period and improving healthcare costs and the workload of healthcare professionals. However, further multicenter, long-term, randomized controlled trials are needed to statistically enhance the understanding of the role of this oral combination in patients treated for DME with anti-VEGF intravitreal maintenance therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization E.M.V. (Enzo Maria Vingolo); statistic analysis, F.M. (Feliciana Menna); investigation, M.C. (Mattia Calabro); methodology F.M. and S.L (Stefano Lupo), software M.C. and F.C., validation M.C. F.M. and S.L, visualization M.C., resources M.C., data curation M.C., writing—original draft, F.M. M.C. S.M. (Simona Mascolo) L.C. (Lorenzo Casillo) F.Mi.(Filippo Miccichè); writing—review and editing, F.M. M.C.; supervision E.M.V. and S.L.; project administration E.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by Ethics Committee of Ospedale A. Fiorini, Terracina, Italy protocol code 035 on 19/12/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMT |

Central Macular Thickness |

| DME |

Cystoid center-involving diabetic macular |

| BCVA |

Best Corrected Visual Acuity |

| DR |

Diabetic retinopathy |

| VEGF |

Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| SD-OCT |

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography |

References

- Wangsa-Wirawan, N.D.; Linsenmeier, R.A. Retinal oxygen: Fundamental and clinical aspects. Arch Ophthalmol 2003, 121, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, W. Country, Retinal metabolism: A comparative look at energetics in the retina. Brain Research 2017, 1672, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, T.W.; Antonetti, D.A.; Barber, A.J.; LaNoue, K.F.; Levison, S.W. Diabetic retinopathy: More than meets the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002, 47 (Suppl 2), S253–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, D.A.; Barber, A.J.; Bronson, S.K.; Freeman, W.M.; Gardner, T.W.; Jefferson, L.S.; Kester, M.; Kimball, S.R.; Krady, J.K.; LaNoue, K.F.; Norbury, C.C.; Quinn, P.G.; Sandirasegarane, L.; Simpson, I.A.; for the JDRF Diabetic Retinopathy Center Group. Diabetic Retinopathy: Seeing Beyond Glucose-Induced Microvascular Disease. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2401–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropp, M.; Golubnitschaja, O.; Mazurakova, A.; Koklesova, L.; Sargheini, N.; Vo, T.K.S.; et al. Diabetic retinopathy as the leading cause of blindness and early predictor of cascading complications-risks and mitigation. EPMA J. 2023, 14, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suciu, C.-I.; Suciu, V.-I.; Nicoara, S.-D. Optical Coherence Tomography Biomarkers in Diabetic Macular Edema. Journal of Diabetes Research 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznicek, L.; Cserhati, S.; Seidensticker, F.; Liegl, R.; Kampik, A.; Ulbig, M.; et al. Functional and morphological changes in diabetic macular edema over the course of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013, 91, e529–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, T. Current Treatments for Diabetic Macular Edema. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruamviboonsuk, V.; Grzybowski, A. The Roles of Vitamins in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassbender Adeniran, J.M.; Jusufbegovic, D.; Schaal, S. Common and Rare Ocular Side-effects of the Dexamethasone Implant. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017, 25, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Muñoz, E.A.; Burggraaf-Sánchez de Las Matas, R.; Mataix Boronat, J.; Molina Martín, J.C.; Desco, C. Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation in the Current Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiosi, F.; Rinaldi, M.; Campagna, G.; Manzi, G.; De Angelis,V. ; Calabrò, F.; et al. Effect of a Fixed Combination of Curcumin, Artemisia, Bromelain, and Black Pepper Oral Administration on Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Indices in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevali, A.; Vaccaro, S.; Borselli, M.; Bousyf, S.; Lamonica, L.; Randazzo, G.; et al. Anatomical and Functional Effects of an Oral Supplementation of Bromelain and Curcugreen in Patients with Focal Diabetic Macular Edema. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Kim, D.; Hernández, C.; Simó, R.; Roy, S. Beneficial effects of fenofibric acid on overexpression of extracellular matrix components, COX-2, and impairment of endothelial permeability associated with diabetic retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2015, 140, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; Bandello, F.; Berg, K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Gerendas, B.S.; Jonas, J.; Larsen, M.; Tadayoni, R.; Loewenstein, A. Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Ophthalmologica 2017, 237, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midena, E.; Toto, L.; Frizziero, L.; Covello, G.; Torresin, T.; Midena, G.; Danieli, L.; Pilotto, E.; Figus, M.; Mariotti, C.; Lupidi, M. Validation of an Automated Artificial Intelligence Algorithm for the Quantification of Major OCT Parameters in Diabetic Macular Edema. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VASun, J.K.; Lin, M.M.; Lammer, J.; et al. Disorganization of the Retinal Inner Layers as a Predictor of Visual Acuity in Eyes With Center-Involved Diabetic Macular Edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014, 132, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwary, A.S.; Oster, S.F.; Yuson, R.M.; Cheng, L.; Mojana, F.; Freeman, W.R. The association between percent disruption of the photoreceptor inner segment-outer segment junction and visual acuity in diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010, 150, 63–67.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshitari, T. Advanced Glycation End-Products and Diabetic Neuropathy of the Retina. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinuthia, U.M.; Wolf, A.; Langmann, T. Microglia and inflammatory responses in diabetic retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 564077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ouyang, H.; Mei, X.; Lu, B.; Yu, Z.; Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Ji, L. Erianin alleviates diabetic retinopathy by reducing retinal inflammation initiated by microglial cells via inhibiting hyperglycemia-mediated ERK1/2-NF-κB signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 11776–11790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abcouwer, S.F. Müller Cell-Microglia Cross Talk Drives Neuroinflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes 2017, 66, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, F.S.; Allkabes, M.; Salsini, G.; Bonifazzi, C.; Perri, P. The importance of glial cells in the homeostasis of the retinal microenvironment and their pivotal role in the course of diabetic retinopathy. Life Sciences 2016, 162, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mynott, T.L.; Guandalini, S.T.; Raimondi, F.R.; Fasano, A.L. Bromelain prevents secretion caused by Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli enterotoxins in rabbit ileum in vitro. Gastroenterology 1997, 113, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, H.R. Bromelain: Biochemistry, Pharmacology and Medical Use. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2001, 58, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, M.; Nambiar, V.; Pan, A.S. Therapeutic effects of bromelain in reducing retinal edema: A review. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2020, 36, 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, R.; Sharma, S.; Shetty, A. Bromelain’s role in reducing retinal inflammation and edema in diabetic retinopathy. Journal of Diabetic Retinopathy 2021, 11, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Gong, Y.; et al. Diosmin Alleviates Retinal Edema by Protecting the Blood-Retinal Barrier and Reducing Retinal Vascular Permeability during Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Y.; Liou, S.-S.; Hong, T.-Y.; Liu, I.-M. The Benefits of the Citrus Flavonoid Diosmin on Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells under High-Glucose Conditions. Molecules 2017, 22, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniello, R.; Melli, M.; Ricci, G. The role of diosmin in treating diabetic macular edema: A clinical review. European Journal of Ophthalmology 2019, 29, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, L.; Carvalho, M.; Teixeira, F. Effects of diosmin on vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology Research 2020, 25, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Gu, L.; Luo, D.; Qiu, Q. Diabetic Macular Edema: Current Understanding, Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2022, 11, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haydinger, C.D.; Ferreira, L.B.; Williams, K.A.; Smith, J.R. Mechanisms of macular edema. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1128811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, L.J.; Auffarth, G.U.; Bagautdinov, D.; Khoramnia, R. Ellipsoid Zone Integrity and Visual Acuity Changes during Diabetic Macular Edema Therapy: A Longitudinal Study. J Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 8117650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatziralli, I.; Theodossiadis, P.; Souli, M. Retinal ischemia and its role in visual impairment in diabetic macular edema: A comprehensive review. Retina Journal 2019, 39, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.M.G.; Fawzi, A.; Teo, K.Y.; Fukuyama, H.; Sen, S.; Tsai, W.S.; Sivaprasad, S. Diabetic macular ischaemia- a new therapeutic target? Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022, 89, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).