1. Introduction

Among typically used materials for EMI shielding, carbon-based materials and metals have been the two most considered ones, owing to their intrinsically high electrical conductivity and high electromagnetic (EM) wave reflection [

1,

2]. Being non-conductive, common polymers are generally non-effective or less effective, unless when combined with other functional materials and/or components. Although the non-conductive issue can be partially solved by using intrinsically electrically conductive polymers such as polythiophene, polyanilines or poly(p-phenylene vinylene), these polymers display limited mechanical and thermal performance, considerably reducing their range of applications. Owing to the development in the last 20-25 years of different types of micro- and especially nano-sized carbon-based fillers, such as carbon nanotubes and more recently graphene-based materials (graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide, graphene nanoplatelets, etc.), their combination with non-conductive polymers (thermoplastics, thermosets and elastomers) has been considered as a possible strategy to obtain conductive polymer-based (nano)composites with expected enhanced EMI shielding performance. Hence, a great number of researchers have considered the development of such polymer-based (nano)composites in terms of developing lightweight structural-functional components with improved electrical conductivities and as a consequence EMI shielding efficiencies for the most varied applications, especially interesting for high demanding sectors such as aerospace or telecommunications [

1,

2]. Albeit promising, as the properties (including the electrical conductivity and as a result the EMI performance) of polymer (nano)composites may be tuned by the addition of functional conductive nanofillers (type(s), concentration, method of preparation, etc.), the possible advantages of foaming such materials are undeniable [

3,

4]. Not only foaming leads to even lighter structures, with direct advantages in fields such as aerospace, and enhanced functional characteristics such as reduced thermal conductivity, but it has also been proved to effectively reduce the percolation threshold of the conductive nanofillers, enabling to obtain lightweight components with high electrical conductivities at lower concentrations of nanofiller. Additionally, in the specific case of EMI shielding, the generation of a controlled cellular structure, especially of the microcellular type, promotes an absorption/multiple reflection-based EMI shielding mechanism, this way reducing the common problem of EMI shielding components based on reflective materials (such as metals) related to the interference of the reflected waves with surrounding electronic components [

3,

5,

6]. Summarizing, the combination of the addition of conductive nanofillers to polymers and generation of a controlled cellular/porous structure enables to create lightweight components with enhanced electrical conductivities and EMI shielding properties. Therefore, this review article, which addresses the most recent trends on polymeric foams and porous structures intended for EMI shielding applications, initially considers the importance and the possibilities of generating foams with a controlled microcellular structure as a way to enhance EMI shielding and promote an absorption-based EMI shielding mechanism, focusing on both common as well as advanced technologies/methods that use sCO

2. Less known but also important and hence considered in this review, are the works that use polymer foams as templates to create carbon foams for high temperature EMI shielding applications. As, besides the generation of a controlled cellular structure and how it may affect the EMI shielding performance of the prepared foams, these also contain conductive nanofillers, this review analyzes the importance of the type(s) of nanofiller(s) used, the effective possible combination of different types of nanofillers (hybrid nanofillers/nanohybrids) and the selective distribution of said nanofillers in the formation of a highly conductive network at lower nanofiller concentrations and hence promotion of the enhancement of the EMI SE. Even more recent and still much less considered (and thus with a high level of interest) than the studies related to the influence of the cellular structure and the generated polymer-nanofiller(s) microstructure on the EMI shielding performance of polymer nanocomposite foams, are the works dedicated to the use of computational tools to assess and tailor the EMI shielding performance of polymer foams, here represented by a recently published work. The last section further extends the concept of polymer-based foams to other porous polymer structures, focusing on porous components prepared using 3D printing, expected to be highly applicable in a great number of fields, as 3D printing technologies have seen a considerable technological boost in recent years and are expected to continue in the coming years. Last but not least, some future perspectives are presented, divided in those based on material/component development and more application-driven.

2. Microcellular foaming for EMI shielding applications

2.1. Supercritical CO2 foaming

As several researchers have demonstrated the importance of developing foams with a controlled microcellular structure for promoting absorption-dominant EMI shielding, sCO

2 foaming has been highly considered as foaming strategy for the fabrication of such lightweight materials intended for high demanding EMI shielding protection applications [

7,

8,

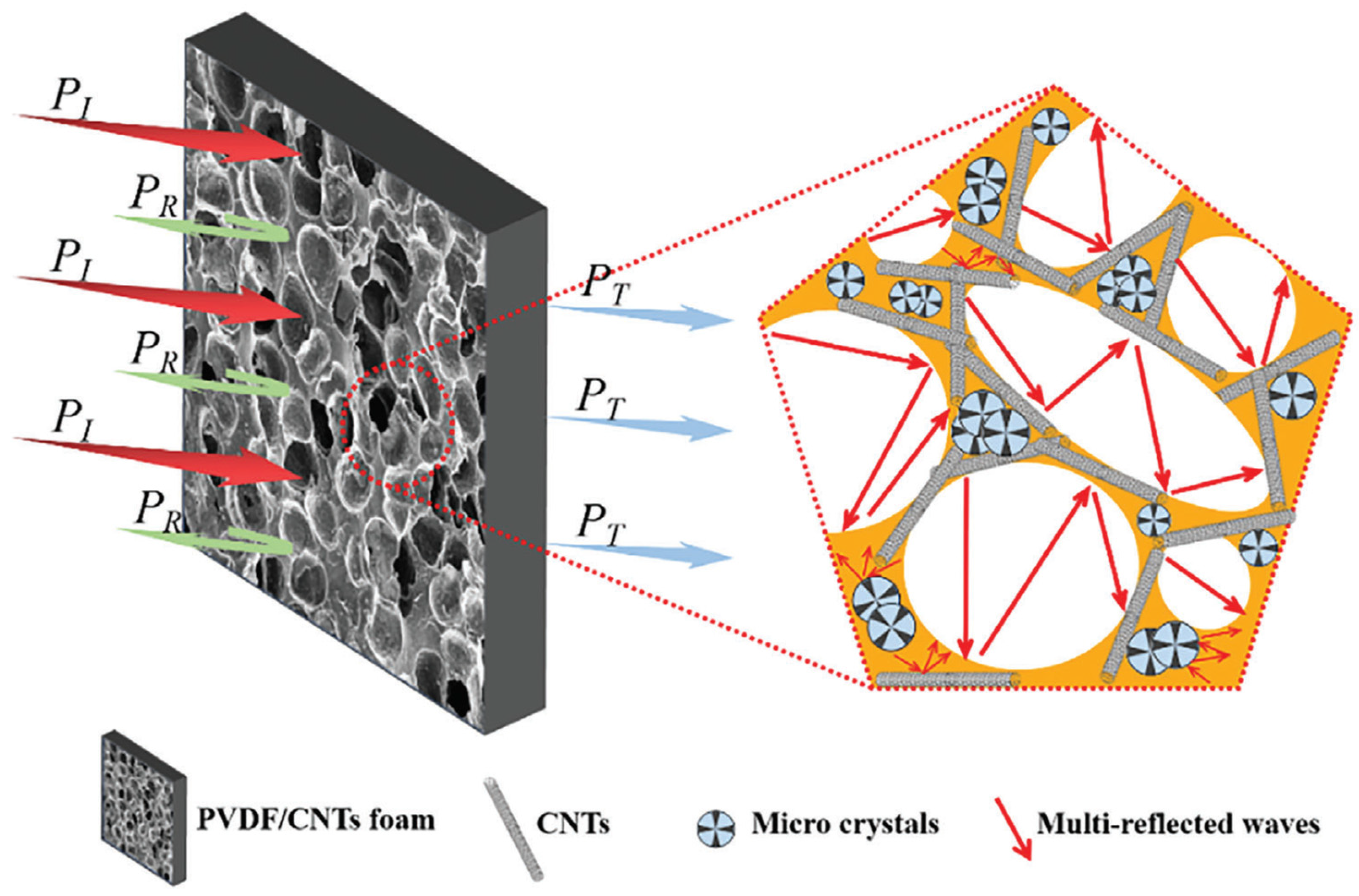

9]. In this sense, Dun and co-workers [

10] prepared by solid-state sCO

2 foaming polyvinylidene difluoride-carbon nanotubes (PVDF-CNT) nanocomposite foams for EMI shielding purposes. They demonstrated that the combination of the generation of a cellular structure during foaming gradually favored the interconnection between carbon nanotubes, promoting the formation of an effective conductive CNT network throughout the cell walls of the foams and as a consequence final materials with high electrical conductivities and EMI shielding efficiencies (reaching a specific value of almost 30 dB·cm

3/g). Additionally, as the generation of the cellular structure during sCO

2 foaming led to the reorientation of CNTs, the resulting foams displayed considerably lower percolation thresholds for electrical conduction when compared to their unfoamed nanocomposites counterparts (0.40 vol% CNT compared to 1.44 vol% CNT, i.e., almost four times lower). The authors also demonstrated how the EMI shielding mechanism changed from reflection-dominant in the case of the unfoamed nanocomposites to increasingly absorption-dominant with foaming, with the controlled cellular structure also contributing to an effective mechanism of multiple reflection (see scheme presented in

Figure 1).

Aghvami-Panah et al. [

11] used microwave-assisted foaming from previously sCO

2 saturated precursors to prepare polystyrene (PS)-based nanocomposite foams containing different concentrations of three different types of carbon-based (nano)fillers: carbon black (CB), carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene nanoplatelets (GnP), and analyzed the EMI shielding performance of the resulting foams. They demonstrated that the type of (nano)filler and its concentration has important effects on the final cellular structure and hence on the properties of the resulting foams, with the maximum value of the specific EMI SE being obtained for PS foams containing a 1 wt% of CNTs (> 50 dB·cm

3/g).

Wang et al. [

9] prepared poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-based microcellular foams containing different graphene oxide (GO)-nickel nanochains (NiNCs), the second of the two with known electric and magnetic anisotropic characteristics, using a sCO

2 foaming process. The combination of the two types of particles having different dimensionalities, 1D NiNCs and 2D GO nanosheets, favored the formation of an effective 3D conductive filler network, resulting in foams with higher electrical conductivities at lower fillers concentrations, and absorption-dominated high EMI SE, in some cases, surpassing 53 dB.

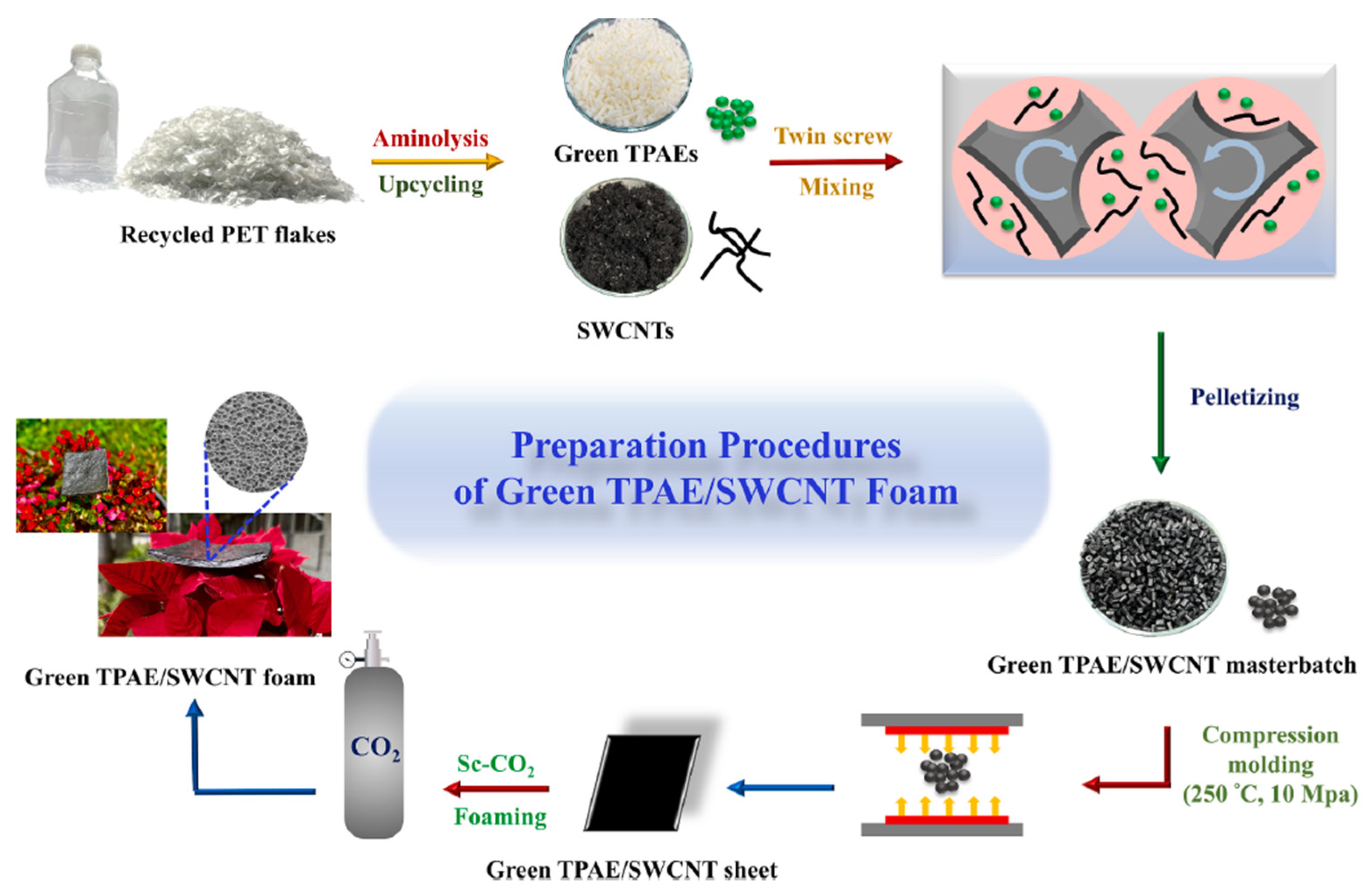

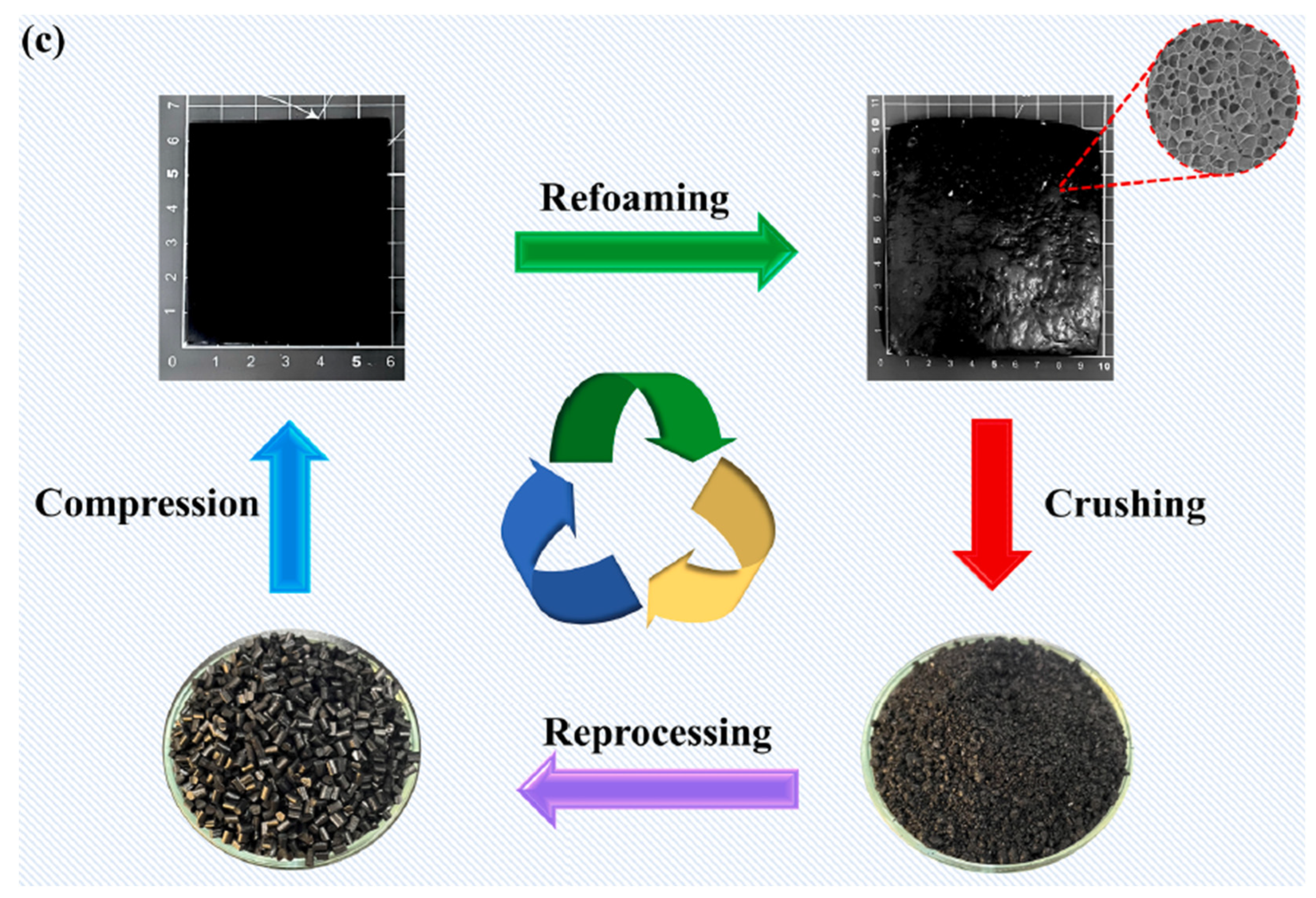

Besides some of the already mentioned environmental advantages of creating lightweight components with enhanced EMI shielding performance for high demanding applications through foaming, as for instance the use of a considerably lower amount of polymer to create the part, there is considerable interest in further improving the sustainability of these materials by using recycled and recyclable polymers. Recently, Lee et al. [

12] have developed nanocomposite foams with outstanding EMI shielding protection by integrating chemically recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET), particularly a thermoplastic polyamide elastomer synthesized using a monomer derived from the aminolysis of recycled PET, combining it with single wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), and later microcellular foaming using sCO

2 dissolution (see scheme presented in

Figure 2). The authors showed that by only adding 2 wt% of SWCNTs the resulting foams displayed extremely high EMI shielding efficiencies, the specific values exceeding 210 dB·cm

3/g. Besides showing a great durability, the nanocomposite foams could be easily recycled, reprocessed and even refoamed (see

Figure 3), opening a promising prospective in reducing plastic waste accumulation and reducing the necessity of virgin plastics in the production of foams for sustainable electronic applications.

2.2. Other microcellular foaming technologies

Besides sCO

2 foaming, there are other manufacturing technologies that can be used to create microcellular polymer-based foams [

8], from more traditional extrusion or injection-molding microcellular foaming [

13,

14,

15,

16] to more advanced and recent processes such as ultrasound-aided [

17,

18,

19], bi-modal [

20,

21,

22,

23] or cyclic [

24,

25] microcellular foaming, including solvent-based processes such as phase separation/inversion processes [

26]. Hence, some research groups have considered these as a possible way of developing microcellular lightweight components with enhanced absorption-dominated EMI shielding characteristics. Such is the case of Zhu et al. [

27], that have recently considered the preparation of microcellular polyamide 6 (PA6)-carbon fiber (CF) composite foams by means of chemical injection foaming. As mentioned before, as the combination of CF addition and chemical foaming led to foams with more uniform smaller-sized cellular structures, EMI SE resulted comparatively higher than the unfoamed composite counterpart (almost 37 dB, almost 30% higher than the non-foamed composite). A similar injection molding-based foaming process, more specifically core-back injection, was used by Wang and co-workers [

28] to prepare lightweight polypropylene (PP)-carbon nanosheets (CNS) nanocomposite foams having a microcellular structure. In this work, the authors showed that it was possible to obtain foams having higher specific flexural modulus values than that of their respective unfoamed injection-molded counterparts, hence foams showing great potential as EMI shields for sensor applications.

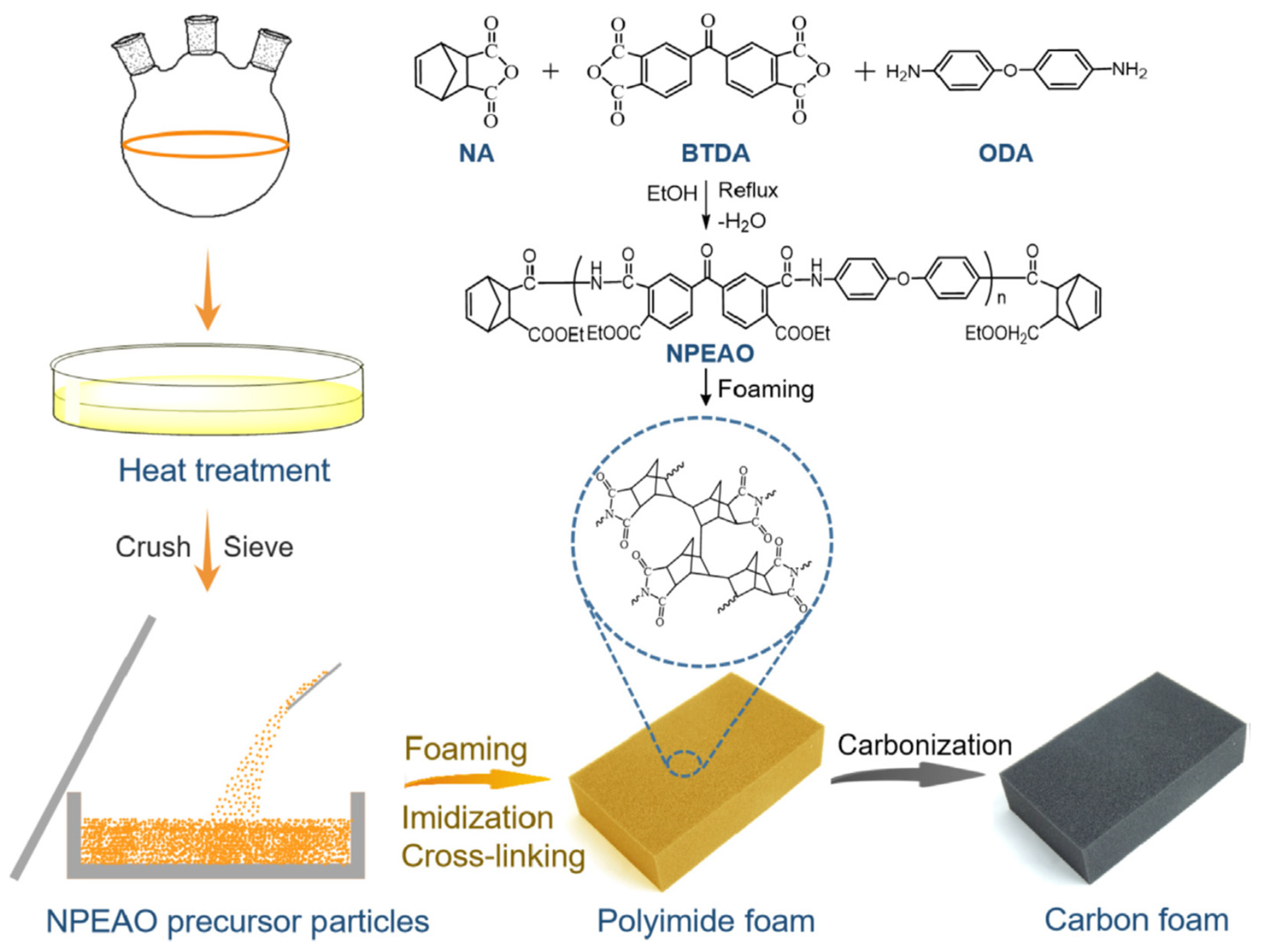

3. Carbon foams obtained from polymer foam templates

Interestingly, researchers have recently considered the strategy of synthesizing carbon foams, known by their high stiffness and high use temperature, with enhanced EMI shielding performance from polymeric foam/porous templates, as they could find potential applications in the aerospace and telecommunication fields as structural-functional integrated elements. In this sense, Li et al. [

29] prepared carbon foams via carbonization of previously prepared thermosetting polyimide (PI) foam templates (see

Figure 4), the resulting foams displaying a combination of good mechanical performance (high compressive strength) and high EMI shielding efficiency, reaching values as high as 54 dB (593.4 dB·cm

3/g in terms of specific EMI SE), related to the crosslinked network of the polyimide templates. The authors also showed that it was possible to adjust the density, compressive mechanical performance and electrical conductivity (and hence EMI SE) by carefully controlling the characteristics of the polyimide templates. Much in the same way, Sharma and co-workers [

30] prepared lightweight carbon foams by carbonizing phenolic impregnated polyurethane foam templates, later decorating the foams with zinc oxide nanofibers by means of electrospinning. They observed that the characteristic open-cell porous structure of the PU foam templates together with the presence of the nanofibers results in lightweight components with absorption-dominant enhanced EMI shielding performance (> 58 dB and > 1000 dB·cm

3/g for a final density as low as 0.28 g/cm

3).

Tang et al. [

31] used some of the previously mentioned strategies, particularly a combination of preparation of emulsion-templated open-cell polymeric composites, their high crosslinking (hypercrosslinking) and carbonization, to fabricate lightweight carbon foams from syndiotactic polystyrene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and magnetic Ni-CNTs. The addition of both CNTs and magnetic Ni-CNTs helped to better control the carbonization stage of preparation of the carbon foams, leading to less shrinkage, higher graphitization degree, larger cells and nanoreinforced pore walls. As a result, the prepared carbon foams displayed a high mechanical robustness, a more hydrophobic nature and a higher specific surface area (as high as 144 m

2/g). The simultaneous use of CNTs and Ni-CNTs nanofillers greatly enhanced the EMI SE, reaching values of almost 80 dB for some of the prepared carbon foams. The authors explained this great EMI SE improvement by a combination of the electrical conduction losses of the conductive carbonized PS-carbon-rich nanofillers network, the polarization losses from the interfacial polarization between the carbonized PS and the nanofillers, dielectric losses within the cells, and magnetic loss from the magnetic Ni-CNTs.

Some researchers have recently addressed the issues concerning both EMI protection and thermal management during the operation of electronic components by combining carbon foams containing conductive carbon-based nanofillers (such as GO, rGO or carbon nanotubes) with phase change materials. For instance, Gao and co-workers [

32] prepared carbon foams with rGO containing paraffin-based phase change materials (see

Figure 5) with improved EMI SE and thermal conductivity, which the authors explained based on the effective construction of an electrically and thermally conductive carbonized melamine foam-rGO 3D network (

Figure 6). Particularly, the authors were able to prepare lightweight components with EMI SE up to 49 dB having an absorption-dominated EMI behavior and a thermal conductivity more than 300% higher than that of pure paraffin, enabling to drop in more than 17 ºC the work temperature in an analog electronic chip device. Also, the developed components exhibited a high cycling and thermal stability, ensuring their long-term use in this sort of electronic devices.

4. Hybrid nanofillers/nanohybrids

As with polymer-based (nano)composites, researchers have recently considered the possibility of tailoring the EMI shielding efficiency of cellular/porous polymer-based (nano)composites not only by controlling their cellular structure (void fraction, open/closed/interconnected cellular structure, cell size, etc.) but also by favoring the formation of an effective electrically-conductive network through the solid fraction by combining different types and proportions of nanofillers (hybrid nanofillers or nanohybrids), as there is a direct relation between the electrical conductivity and the EMI SE. In this sense, Dehghan et al. [

33] prepared cellular nanocomposites using sCO

2 with hybrid MXene/rGO nanosheets, showing that the use of the hybrid fillers led to foams with smaller cell sizes and higher values of electrical conductivity when compared to the ones containing only MXene, globally resulting in components with higher EMI shielding efficiencies, > 25 dB for foams containing MXene/rGO nanohybrids and less than 18 dB for foams containing only MXene (see comparison between foams containing only MXene and foams containing MXene/rGO nanohybrids in

Figure 7). Zhang et al. [

34] combined carbon-based nanoparticles having different geometries, particularly layered-like graphene nanosheets and tubular-like carbon nanotubes, and prepared microcellular PMMA-based (nano)composite foams containing these nanohybrids by sCO

2 dissolution. Interestingly, they demonstrated that foaming promoted the exfoliation of graphene nanosheets and a better distribution of the nanohybrids throughout the solid fraction of the foams, with CNTs interconnecting the graphene sheets helping to create a highly effective conductive 3D network, leading to materials with high electrical conductivities and EMI shielding efficiencies, especially when compared to the unfoamed counterparts.

Cheng and co-workers [

35] have taken advantage of the particular structure of some types of polymeric foams, in their case the particular sponge-like structure of some waterborne polyurethane (PU) foams, to prepare by dip-coating PU-based composite foams containing CNT-magnetic anisotropic Ni particles hybrids intended for EMI shielding protection. Once again, the authors demonstrated the effective synergistic effect of combining both types of nanofillers, as the foams containing the hybrids reached EMI SE values higher than 42 dB, clearly exceeding those of the PU foams containing only CNTs. Based on the results, the authors proposed a mechanism to describe the absorption-dominated EMI shielding characteristics of the resulting PU-CNT-Ni foams (see

Figure 8): first of all, EM waves are attenuated due to conduction losses in alternating EM fields promoted by the electrically conductive solid fraction; secondly, the addition of the Ni particles makes the EM wave impedance match with that of the composites, with interfacial polarization losses between CNTs, Ni and PU and hence wave absorption; and third, the attenuation of EM waves is also promoted by the magnetic losses caused by the magnetic Ni particles. Additionally, incident EM waves are reflected and scattered multiple times at the wall interface formed by the hybrid fillers structure, further dissipating EM energy. Zheng et al. [

36] used a similar PU-based foamed system combining Fe

3O

4-polyvinyl acetate (PVA) and GO-silver particles as (nano)filler, demonstrating the possible synergistic effects between both types of (nano)fillers in terms of establishing an effective network through the PU foam structure, leading to high EMI shielding efficiencies (> 30 dB and almost 280 dB·cm

3/g) and to an absorption-dominated primary shielding mechanism. As with the use of Ni, the addition of the ferromagnetic Fe

3O

4 particles effectively improved the absorption performance due to a combined characteristic dielectric loss of ferroelectric materials and the hysteresis loss of ferromagnets. Zhu et al. [

37] were able to modulate the EMI shielding properties of polymer composite foams prepared by double dip-coating a previously prepared sponge-like PU foam, first making it conductive in a SWCNT dispersion and in a second stage coating the already conductive foam with a paraffin solution/emulsion (see

Figure 9), this way creating a shape memory-like foam whose EMI shielding performance may be modulated by applying a controlled compressive stress and later possible recovery. The resulting foams showed extremely high values of the EMI SE (56 dB) for ultra-low densities (0.03 g/cm

3) by adding a SWCNTs content below 0.2 vol%, displaying ultra-high durabilities (> 2000 compression-recovery cycles) and adjustable continuous EMI shielding efficiencies between 18 and 30 dB.

As a consequence of their characteristic mechanical performance, lightness and enhanced EMI shielding protection, these foams are expected to find possible applications in the field of electronics, for instance as portable and wearable electronic devices.

5. Selective distribution of conductive nanofillers

Wang et al. [

38] have recently used an interesting strategy to enhance the EMI shielding performance of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU)-CNT composite foams, which consisted in creating a multilayer gradient structure (see scheme of the preparation process in

Figure 10) by adjusting the cellular structure and ratio of soft/hard domains of each layer, combined with the selective distribution of the conductive carbon nanotubes throughout the hard domain (see scheme presented in

Figure 11(a)). This selective distribution of the conductive CNTs improved the interlayer polarization of EM and the impedance matching between material and air, leading to foams whose EMI SE (> 35 dB) resulted 20% higher than that of the homogenous composites containing the same amount of CNTs. The proposed EMI shielding mechanism of TPU-CNT composites with multilayer gradient structure after foaming, presented in

Figure 11(b), based on a combination of polarization loss and multiple reflection, enables to correlate the importance of selectively distributing conductive nanoparticles throughout a given domain of the material and the EMI shielding performance, opening new possibilities in the design of lightweight components based on low filler composites with enhanced EMI shielding protection. Some researchers have even further extended this layered-gradient like concept, combining conductive foamed layers based on a polymer nanocomposite foam with layers formed by different materials, such as aluminum, knitted fabric layers, etc., endowing the sandwich-like materials with excellent EMI shielding [

39].

Much in the same way as Wang et al., Liu and co-workers [

40] prepared biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL)/poly(lactic acid) (PLA)-CNT composite foams by selectively distributing/dispersing the CNTs throughout the PCL matrix, in this way facilitating the formation of an effective conductive network in the final prepared foams. As a result, the resulting foams displayed an absorption-dominant EMI shielding behavior with an EMI SE of almost 23 dB and a specific EMI SE of around 90 dB·cm

3/g, which opens brand new possibilities in the development of fully biodegradable components for EMI shielding protection.

Interestingly, Feng et al. [

41] were able to selectively distribute conductive CNTs at the interfaces of polyetherimide (PEI) granules when preparing PEI-CNT foams through a ball milling, sinter molding and later sCO

2 dissolution foaming process, which led to the formation of conductive paths at extremely low CNT concentrations (percolation threshold of 0.06 vol%) and hence to foams with high values of electrical conductivity (almost 8 S/m) and as a result high EMI shielding efficiencies (> 30 dB).

Taking advantage of the fact that the generation of a controlled and particular cellular structure during foaming may reduce the actual conductive paths between conductive particles pre-dispersed throughout the polymer-based matrix before foaming due to an excluded volume effect and even promote the redistribution and alignment of the particles, Wu and co-workers [

42] were able to prepare PP-CNT composite foams with enhanced EMI shielding efficiencies (reaching values of almost 60 dB) using a core-back foaming injection molding process, as foaming enabled to create cellular structures with big cells, which promoted the formation of a more effective path of aligned conductive particles. Yang et al. [

43] had already used a similar strategy to prepare highly conductive polymer-based composites at extremely low rGO percolation thresholds (0.055 vol%). Peng and co-workers [

44] promoted the formation of a bi-conductive network in polymer-based foams by combining the high-efficiency of Ni-coated melamine foam sponges as absorption-driven EMI shielding elements and the redistribution and arrangement of conductive CNTs induced by foaming in CNT-TSM-PDMS composite foams, leading to EMI SE as high as 45 dB for CNT contents of only 3 wt%. As expected, EMI shielding was absorption-dominated, the foams additionally showing outstanding EMI shielding durability even in harsh environments.

6. Computational approaches

Owing mostly to their (micro)structural complexity, the scientific works that deal with polymer (nano)composites, polymer foams and polymer-based (nano)composite foams intended for EMI shielding protection where the EMI shielding mechanism is absorption dominated, still rely a lot on trial and error, not considering or only superficially mentioning the real mechanisms governing the (micro)structure-EMI shielding performance relationship for these materials. Only recently, researchers have started to consider the use of computational-based approaches to develop composite foams for EMI shielding. Particularly, Park et al. [

45] have dealt with the fabrication of layered PVDF-based composite foams, focusing on the effects of the layered structure and microcellular structure of the developed layered foams on their final EMI shielding performance. They demonstrated through the use of a theoretical computation approach that the best result in terms of the layered structure consisted of an absorption layer based on a medium-density PVDF foam containing a high amount of SiC nanowires and MXene nanosheets and a shielding layer formed by a lower density PVDF-8 wt% CNT nanocomposite foam (see

Figure 12). Experimental findings also corroborate the importance of optimizing the void fractions of both foamed layers in terms of guaranteeing the best possible input impedance matching, and that the addition of nanohybrids based on 2D conductive MXene nanosheets and 1D SiC nanowires to the PVDF in the absorption layer provides great EM wave dissipation enhancements. Hence, the tailored layered structures exhibit a combination of low EM reflectivity and high EMI SE, opening up great possibilities in the development of tailor-made elements with absorption-dominant EMI shielding characteristics for a vast array of high performance applications.

7. 3D printing

In 2018, Bregman and co-workers [

46] published an article where they presented a model-based methodology (finite element modeling in COMSOL) for estimating the EMI shielding properties of polymer-based composites, using measurements of complex EM parameters, predictive absorption modeling and later fabrication by 3D printing, more specifically by fused filament fabrication, and compression-moulding. Some of the presented preliminary results using a commercial PLA-based filament containing 16 wt% of graphene/carbon nanotubes/carbon black conductive filler seem to suggest that the presence of a controlled cellular structure (periodic pore structure) in a conductive polymer (nano)composite can lead to lower EM reflection losses and higher absorption capability. The authors claimed that this was possible due to a combination of dielectric mismatch between the conductive PLA-based filament and the air present inside of the pores, which causes multiple reflection at interfaces, and the presence of dissipation pathways (conductive fillers) as well as a material fraction whose relative impedance is 1 or close to 1 (air inside of pores), associated to a lower front face reflection and hence higher absorption.

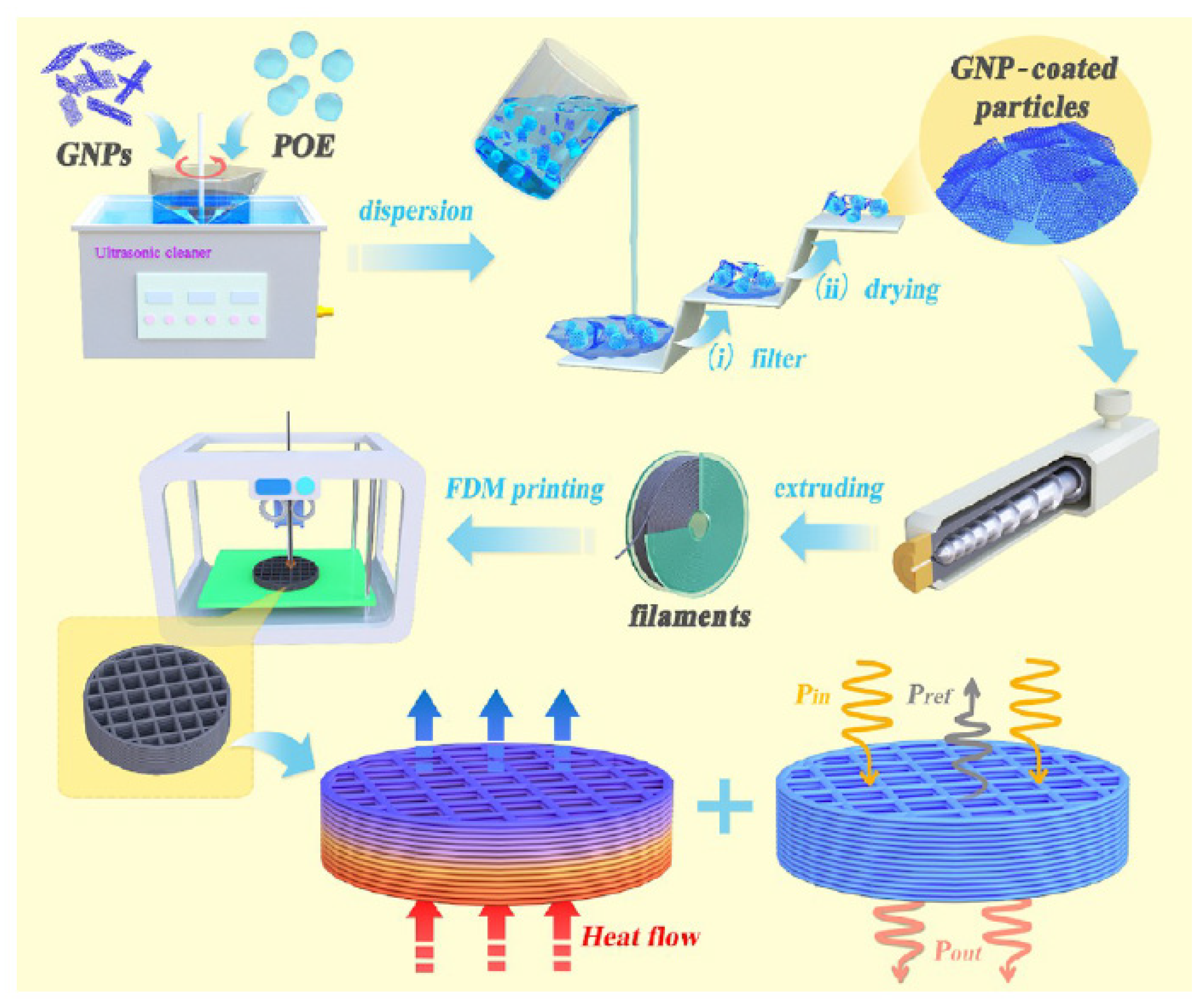

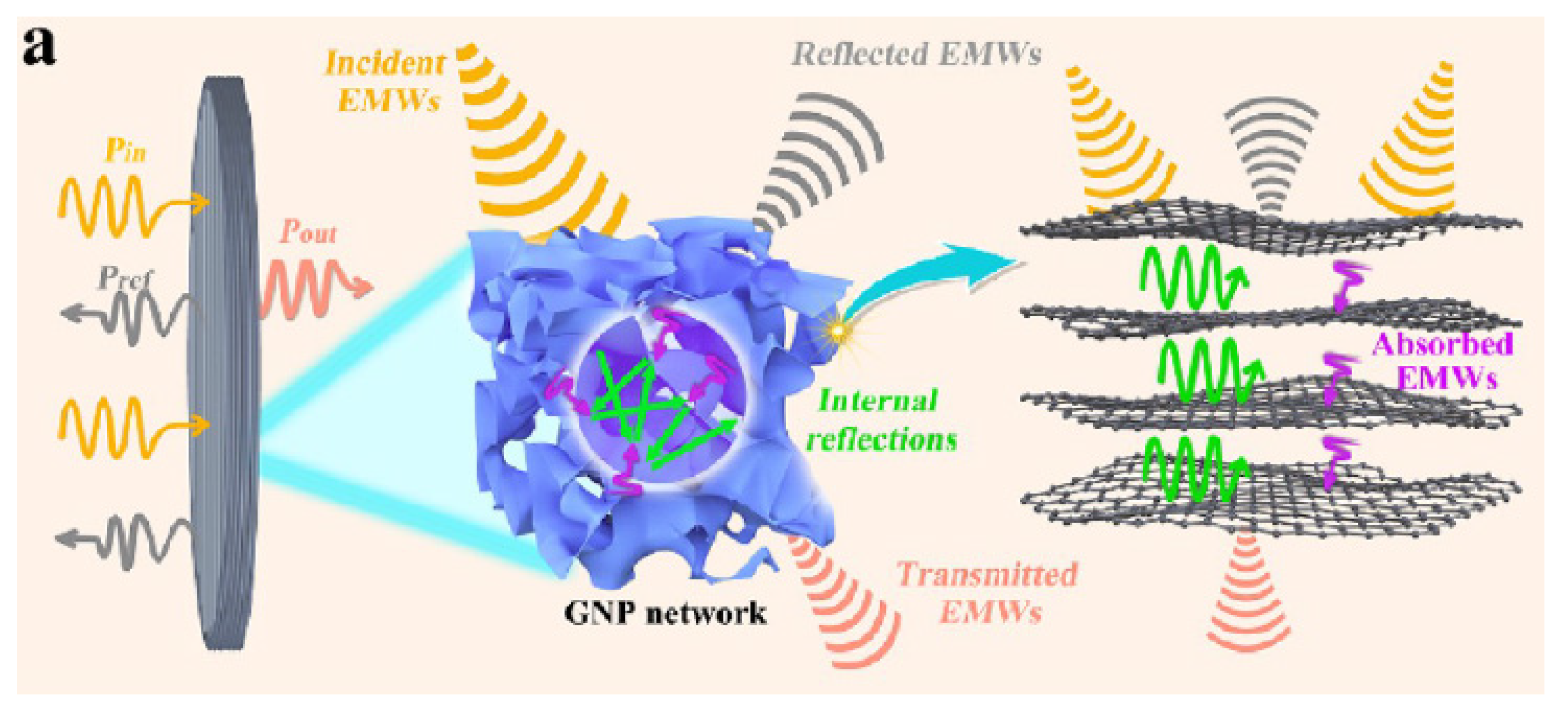

Using a similar fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing process (see scheme presented in

Figure 13), Lv et al. [

47] prepared polyolefin elastomer (POE)-graphene nanoplatelets (GnPs) nanocomposite foams and demonstrated their viability for thermal management applications as a result of their enhanced absorption-based electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency (EM mixed multiple reflection-absorption mechanism can be seen in

Figure 14), reaching values as high as 35 dB or almost 245 dB·cm

2/g (thickness-normalized specific value), and high thermal conductivity (4.3 W/(m·K)).

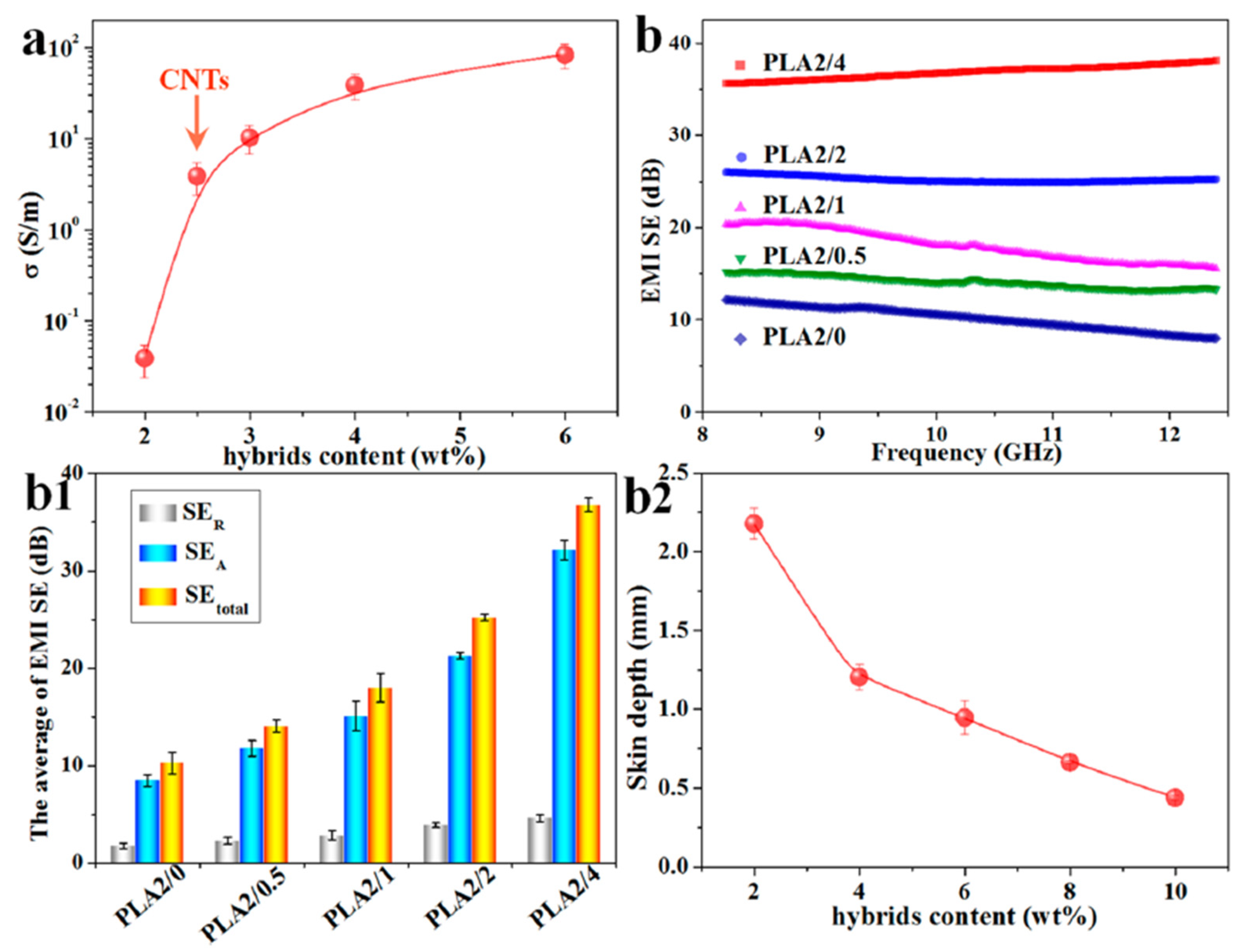

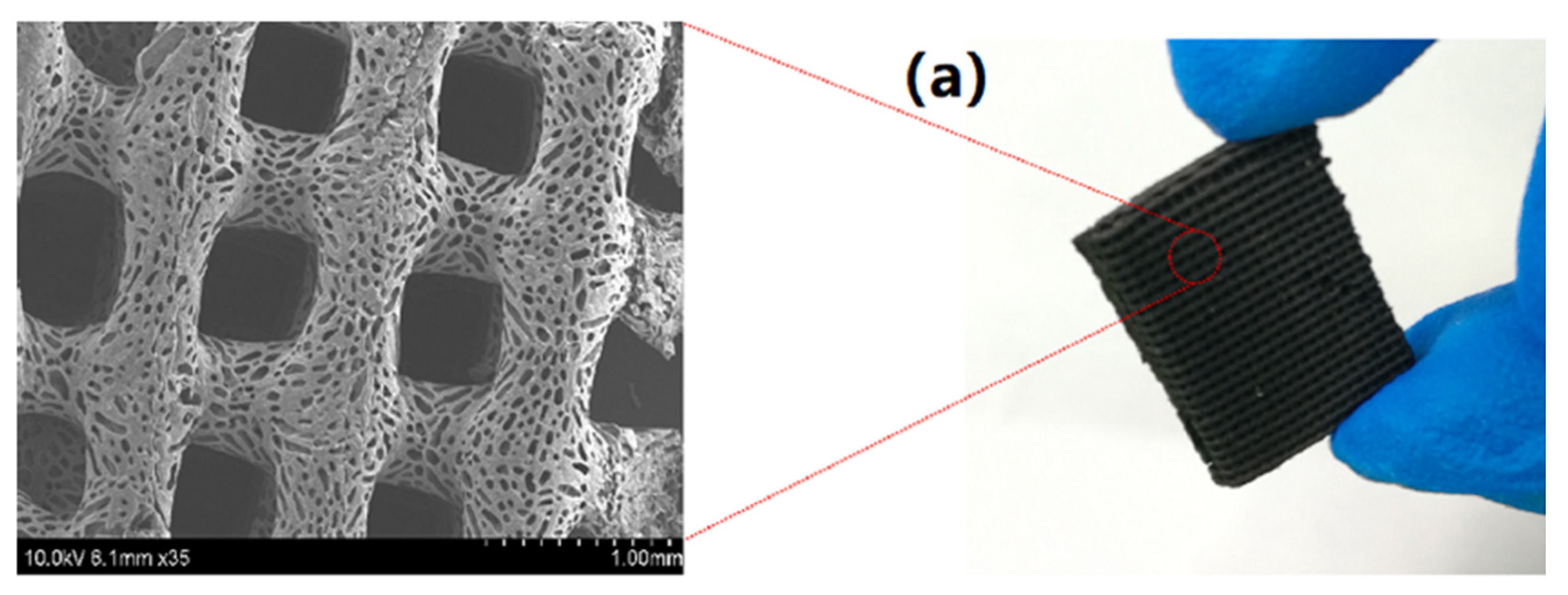

Shi and co-workers [

48] prepared by FDM 3D-printing honeycomb-like cellular nanocomposites based on the combination of PLA and conductive GnP/CNT nanohybrids (see images presented in

Figure 15), with the resulting cellular/porous parts showing improved mechanical performance and especially EMI shielding efficiencies as high as 37 dB (X-band range), much higher than the common commercial standard of 20 dB for EMI shielding applications (see

Figure 16). Interestingly, the authors used finite element simulation based on the fluid dynamics of polymer melts to optimize the amount of GnP and CNT in the nanohybrids (optimum values of 2 and 4 wt%, respectively), and established a quantitative relationship between the final cellular/porous structure and the EMI shielding properties of the 3D printed part, hence facilitating the design of novel 3D printed lightweight structures for electromagnetic radiation protection.

In a similar way but counteracting one of the main problems of adding conductive carbon-based nanofillers (in this case, carbon nanotubes) to a polymer matrix, which is nanofiller agglomeration, Pei et al. [

49] used high energy mechanical ball milling to evenly distribute and disperse CNTs throughout a chitosan (CS) matrix and successfully create CS-CNTs 3D printing ink. After creating porous parts by 3D printing (see

Figure 17), the authors demonstrated that they effectively absorbed EM waves, reaching EMI shielding efficiencies higher than 25 dB and high absorption losses (> 19 dB) for densities as low as 0.072 g/cm

3, hence showing that the prepared printing ink may find promising applications in the 3D printing of lightweight components with improved EMI shielding performance.

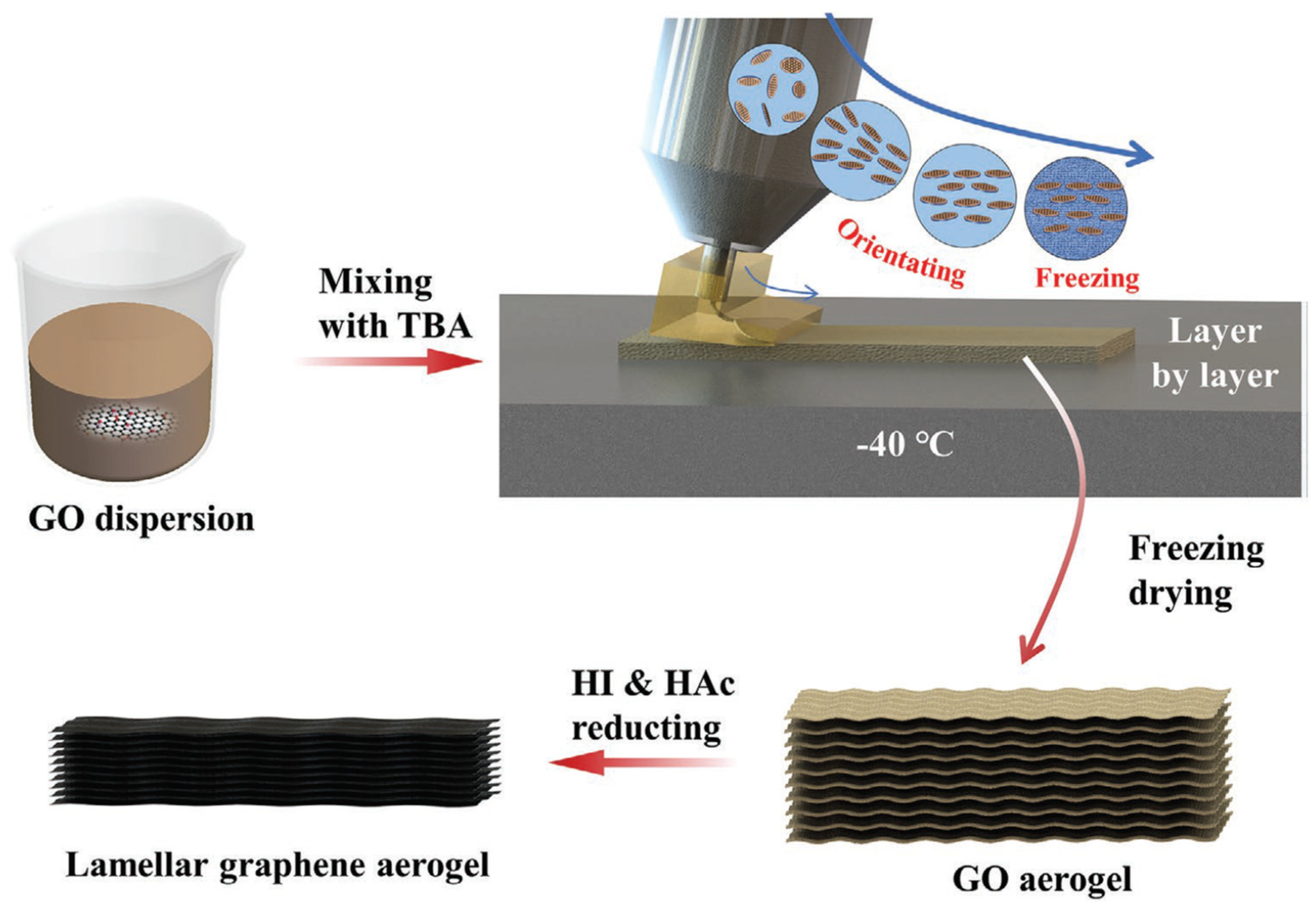

More recently, some authors have considered the 3D printing of polymer-based aerogels for EMI shielding and piezoresistive sensor applications. In this sense, Guo and co-workers [

50] have developed a strategy based on the 3D printing of lamellar graphene aerogels (LGA), more specifically on the printing through a slit extrusion printhead of a shear thinning GO water-based dispersion (see

Figure 18). As a result of a much better control of the size and shape of the graphene platelets when compared to more traditional methods, the LGAs showed higher EMI shielding efficiencies (up to almost 69 dB for a 3 mm thickness).

Xue et al. [

51] took further this concept and prepared by 3D printing aerogel frames with hierarchical porous structure and hence gradient-conductivity based on MXene-CNT-Polyimide, showing that the prepared aerogels had almost fully absorption-based EM behavior, thanks to the slightly conductive EM absorption top layer and the highly conductive EM reflective bottom layer, combined with the dissipation of EM waves by multiple reflections (hierarchical porous structure). The result was the creation of aerogels with extremely high EMI shielding efficiencies (> 68 dB) and globally low reflection losses, hence with promising applications in defense and aerospace industries.

8. Future perspectives and concluding remarks

The further development and application of polymer-based (nano)composite foams and porous structures for EMI protection, albeit currently very trending and needed due to the technological challenges related to the increasing use of wireless communication electronic devices, still requires a great deal of work, not only related to the (micro)structural complexity of such materials and technological challenges related to their preparation, but also to the increasingly more demanding electronics industry, which now requires components with EMI shielding protection and a vast range of additional properties, such as heat dissipation or long-term stable mechanical performance. Future perspectives in the development and application of such materials seem to take two parallel ways: one related to the development of novel materials/components, i.e., their composition, the development of new processes/methods/technologies to carefully control their cellular structure (both foams as well as porous structures), and the design and use of gradient/layered structures; and a more application-driven way, with the possible development of strategies to tailor-control the (micro)structural characteristics of the developed foams/porous structures and hence their properties for a specific application.

The first of the above mentioned ways, related to the development of new polymer-based formulations and components, has already been mentioned to a great extent in this review, as it focusses initially on the adaptation of the composition of the polymer nanocomposite foams to the foaming process and to the required final characteristics of the components to be used for EMI shielding. Particularly, the most common strategy, expected to be further explored in the coming years, is the addition to polymer matrices and proper distribution/dispersion of hybrid fillers that combine functional nanoparticles, especially conductive and/or magnetic, having different geometries/dimensionalities/characteristics, such as tubular-like carbon nanotubes and flat-like graphenes. Chemically, polymer matrices having reactive functional groups may also be modified by functional molecules and/or (nano)fillers. Even more specific composition modification can be considered, as the already mentioned selective distribution/dispersion/preferred orientation of the nanofillers, the addition of nucleating agents to promote cell size reduction in the foams and the crystallization in semi-crystalline polymer matrices [

52], or the control of the phase morphology of the polymer-based solid fraction of the foam, for instance by sCO

2 annealing [

53], could be used as strategies to enhance the EMI SE. Also interesting and somewhat related to the more application-driven future perspective motor, is the possibility of adding functional (nano)fillers to bio-based polymers and later foaming to create biodegradable lightweight components for more short/medium-term EMI shielding applications.

Besides composition, the development of new fabrication processes and technologies to generate controlled cellular/porous structures intended to maximize EMI shielding, especially focused on favoring EM wave absorption, is critical in terms of enabling to transfer the scientific knowledge to the industry. In this sense, new industrial foaming technologies and fabrication processes are expected to arise in the future, especially those intended to generate microcellular foams, mainly advanced microcellular foaming processes such as ultrasound-assisted sCO2 foaming or multi-modal and cyclic foaming processes, or controlled porous structures such as 3D printing.

Last but not least, the design and use of gradient/layered structures where at least one of the layers is formed by an EM wave absorber material based on a polymer-based foam or porous structure, previously mentioned in this review, is expected to be one of the most interesting strategies in terms of developing lightweight components with tailor-made EMI shielding performance.

As expected, some of the future trends of polymer-based (nano)composite foams and porous structures are more application-driven, trying to connect the best of both scientific and industrial worlds. There is a high interest in developing viable strategies to control and, if possible, tailor-control, the characteristics of the resulting foams, this way enabling to prepare lightweight components with adjustable EMI shielding properties for a specific field and application, from flexible foams for sensors to rigid porous structures for high demanding structural applications.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (project PID2021-128048NB-I00).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbasi, H.; Antunes, M.; Velasco, J.I. Recent Advances in Carbon-Based Polymer Nanocomposites for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 103, 319–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omana, L.; Chandran, A.; John, R.E.; Wilson, R.; George, K.C.; Unnikrishnan, N.V.; Varghese, S.S.; George, G.; Simon, S.M.; Paul, I. Recent Advances in Polymer Nanocomposites for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding: A Review. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25921–25947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Noroozi, M.; Abrisham, M.; Eghbalinia, S.; Teimoury, F.; Bahramian, A.R.; Dehghan, P.; Sadri, M.; Goodarzi, V. A Comprehensive Review on Carbon-Based Polymer Nanocomposite Foams as Electromagnetic Interference Shields and Piezoresistive Sensors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 2318–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orasugh, J.T.; Ray, S.S. Functional and Structural Facts of Effective Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Materials: A Review. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 8134–8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kausar, A.; Ahmad, I.; Zhao, T.; Aldaghri, O.; Ibnaouf, K.H.; Eisa, M.H. Nanocomposite Foams of Polyurethane with Carbon Nanoparticles-Design and Competence towards Shape Memory, Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Shielding, and Biomedical Fields. Crystals 2023, 13, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Noroozi, M.; Xiao, X.; Park, C.B. Recent Advances in Graphene-Based Polymer Nanocomposites and Foams for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 1545–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yan, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Han, W.; Chai, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T. Progress in the Foaming of Polymer-based Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Composites by Supercritical CO2. Chem Asian J. 2023, 18, e202201000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugad, R.; Radhakrishna, G.; Gandhi, A. Recent advancements in manufacturing technologies of microcellular polymers: A review. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Hui, L.; Zhang, X.; Qin, J. Design and research of high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding GO/NiNCs/PMMA microcellular foams. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, D.; Luo, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Wen, B.; Zhang, Y. Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Foams Based on Poly(vinylidene fluoride)/Carbon Nanotubes Composite. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghvami-Panah, M.; Wang, A.; Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Esfahani, S.A.S.; Seraji, A.A.; Shahbazi, M.; Ghaffarian, R.; Jamalpour, S.; Xiao, X. A comparison study on polymeric nanocomposite foams with various carbon nanoparticles: Adjusting radiation time and effect on electrical behavior and microcellular structure. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2022, 13, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-W.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, L.-Y.; Lee, Y.-H. Developing sustainable and recyclable high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding nanocomposite foams from the upcycling of recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate). Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, M. Thermoplastic foams: Processing, manufacturing, and characterization. Polymerization. London: IntechOpen, 2018, pp. 117–137.

- Sauceau, M.; Fages, J.; Common, A.; Nikitine, C.; Rodier, E. New challenges in polymer foaming: A review of extrusion processes assisted by supercritical carbon dioxide. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guanghong, H.; Yue, W. Microcellular foam injection molding process. In: Some Critical Issues for Injection Molding. IntechOpen, 2012, pp. 175–202.

- Hou, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, G.; Dong, G.; Xu, J. A novel gas-assisted microcellular injection molding method for preparing lightweight foams with superior surface appearance and enhanced mechanical performance. Mater. Des. 2017, 127, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhai, W.; Ling, J.; Shen, B.; Zheng, W.; Park, C.B. Ultrasonic irradiation enhanced cell nucleation in microcellular poly(lactic acid): A novel approach to reduce cell size distribution and increase foam expansion. Ind Eng Chem Res 2011, 50, 13840–13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, W. Selective ultrasonic foaming of polymer for biomedical applications. J Manuf Sci Eng 2008, 130, 021004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Kumar, V. Creating open-celled solid-state foams using ultrasound. J Cell Plast 2009, 45, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Asija, N.; Chauhan, H.; Bhatnagar, N. Ultrasound-induced nucleation in microcellular polymers. J Appl Polym Sci 2014, 131, 9076–9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-N.; Jing, X.; Geng, L.-H.; Chen, B.-Y.; Mi, H.-Y.; Peng, X.-F. A novel multiple soaking temperature (MST) method to prepare polylactic acid foams with bi-modal open-pore structure and their potential in tissue engineering applications. J Supercrit Fluids 2015, 103, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Q.; Huang, H.X. Formation mechanism and tuning for bi-modal cell structure in polystyrene foams by synergistic effect of temperature rising and depressurization with supercritical CO2. J Supercrit Fluids 2016, 109, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, G.; Dugad, R.; Gandhi, A. Bimodal Microcellular Morphology Evaluation in ABS-Foamed Composites Developed Using Step-Wise Depressurization Foaming Process. Polym Eng Sci 2020, 60, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Cha, S.W.; Seo, J.; Ahn, J. A study on the foaming ratio and optical characteristics of microcellular foamed plastics produced by a repetitive foaming process. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 2013, 14, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-H.; Ohm, W.-S.; Cho, S.-H.; Cha, S.W. Effects of repeated microcellular foaming process on cell morphology and foaming ratio of microcellular plastics. Polym-Plast Technol Eng 2011, 50, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, B.P.; Hur, S.H.; Choi, W.M.; Chung, J.S. Facile fabrication of stacked rGO/MoS2 reinforced polyurethane composite foam for effective electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. : Part A 2023, 166, 107366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Jiang, T.; Zeng, X.; Li, S.; Shen, C.; Zhang, C.; Gong, W.; He, L. High strength and light weight polyamide 6/carbon fiber composite foams for electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, M.; Ren, Q.; Weng, Z.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, W.; Yi, X. Strong and high void fraction PP/CNS nanocomposite foams fabricated by core-back foam injection molding. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, Y.; Yu, N.; Gao, Q.; Fan, X.; Wei, X.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Z.; He, X. Lightweight and stiff carbon foams derived from rigid thermosetting polyimide foam with superior electromagnetic interference shielding performance. Carbon 2020, 158, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, A.; Agrawal, P.R.; Dwivedi, N.; Mondal, D.P.; Srivastava, A.K.; Dhakate, S.R. Enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding properties of phenolic resin derived lightweight carbon foam decorated with electrospun zinc oxide nanofibers. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 30, 103055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xu, P.; Dong, J.; Gui, H.; Zhang, T.; Ding, Y.; Murugadoss, V.; Naik, N.; Pan, D.; Huang, M.; Guo, Z. Carbon foams derived from emulsion-templated porous polymeric composites for electromagnetic interference shielding. Carbon 2022, 188, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Ding, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, J. Carbon foam/reduced graphene oxide/paraffin composite phase change material for electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal management. J. Energy Storage 2023, 58, 106355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, P.; Simiari, M.; Gholampour, M.; Aghvami-Panah, M.; Amirkiai, A. Tuning the electromagnetic interference shielding performance of polypropylene cellular nanocomposites: Role of hybrid nanofillers of MXene and reduced graphene oxide. Polym. Test. 2023, 126, 108162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Tang, M.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Fan, X.; Shi, X.; Qin, J. Synergistic Effect of Carbon Nanotube and Graphene Nanoplates on the Mechanical, Electrical and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Properties of Polymer Composites and Polymer Composite Foams. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 353, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, Y.; Liu, C.; Shen, C.; Liu, X. Synergistic effects between carbon nanotube and anisotropy-shaped Ni in polyurethane sponge to improve electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. China Mater. 2023, 66, 2803–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Li, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, X. Lightweight polyurethane composite foam for electromagnetic interference shielding with high absorption characteristic. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 649, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, M.; Dale, J.; Qiang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, M.; Ye, C. Modulating electromagnetic interference shielding performance of ultra-lightweight composite foams through shape memory function. Compos. Part B 2021, 204, 108497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zou, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Liao, X. Electromagnetic interference shielding composites and the foams with gradient structure obtained by selective distribution of MWCNTs into hard domains of thermoplastic polyurethane. Compos. Part A 2024, 176, 107861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Dong, Y.-E. Multifunctional composite foam with high strength and sound-absorbing based on step assembly strategy for high performance electromagnetic shielding. Polym. Compos. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Feng, H.; Zeng, W.; Jin, C.; Kuang, T. Facile Fabrication of Absorption-Dominated Biodegradable Poly(lactic acid)/Polycaprolactone/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Foams towards Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Liu, P.; Wang, Q. Exploiting the Piezoresistivity and EMI Shielding of Polyetherimide/Carbon Nanotube Foams by Tailoring Their Porous Morphology and Segregated CNT Networks. Compos. Part A 2019, 124, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ren, Q.; Gao, P.; Ma, W.; Shen, B.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W.; Cui, P.; Yi, X. Enhanced electrical conductivity and EMI shielding performance through cell size-induced CNS alignment in PP/CNS foam. Compos. Commun. 2023, 43, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, R.; Song, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Shen, Y. One-Pot Preparation of Porous Piezoresistive Sensor with High Strain Sensitivity via Emulsion-Templated Polymerization. Compos. Part A 2017, 101, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Ma, M.; Chu, Q.; Lin, H.; Tao, W.; Shao, W.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; He, H.; Wang, X. Absorption-dominated electromagnetic interference shielding composite foam based on porous and bi-conductive network structures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 10857–10866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wei, L.; Hamidinejad, M.; Park, C.B. Layered polymer composite foams for broadband ultra-low reflectance EMI shielding: A computationally guided fabrication approach. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 4423–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, A.; Taub, A.; Michielssen, E. Computational design of composite EMI shields through the control of pore morphology. MRS Commun. 2018, 8, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Peng, Z.; Meng, Y.; Pei, H.; Chen, Y.; Ivanov, E.; Kotsilkova, R. Three-Dimensional Printing to Fabricate Graphene-Modified Polyolefin Elastomer Flexible Composites with Tailorable Porous Structures for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding and Thermal Management Application. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 16733–16746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Peng, Z.; Jing, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y. 3D Printing of Delicately Controllable Cellular Nanocomposites Based on Polylactic Acid Incorporating Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Hybrids for Efficient Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7962–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Lu, H.; Yu, R.; Xu, Z.; Li, D.; Tang, Y.; Xing, W. Porous network carbon nanotubes/chitosan 3D printed composites based on ball milling for electromagnetic shielding. Compos. Part A 2021, 145, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hua, T.; Qin, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, R.; Qian, B.; Li, L.; Shi, X. A New Strategy of 3D Printing Lightweight Lamellar Graphene Aerogels for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding and Piezoresistive Sensor Applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.T.; Yang, Y.; Yu, D.Y.; Wali, Q.; Wang, Z.Y.; Cao, X.S.; Fan, W.; Liu, T.X. 3D Printed Integrated Gradient-Conductive MXene/CNT/Polyimide Aerogel Frames for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding with Ultra-Low Reflection. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhang, X.; Hou, J.; Chen, J. Lightweight electromagnetic interference shielding poly(L-lactic acid)/poly(D-lactic acid)/carbon nanotubes composite foams prepared by supercritical CO2 foaming. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 210, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Chen, J.; Liao, X.; Song, P.; Li, G. Efficient electrical conductivity and electromagnetic interference shielding performance of double percolated polymer composite foams by phase coarsening in supercritical CO2. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 213, 108895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).