1. Introduction

Pickering emulsions are a type of emulsion where solid particles serve as stabilizers that anchor at the oil/water interface to form oil-in-water (O/W) or water-in-oil (W/O) emulsions. The Pickering emulsion maintains its stability by forming an interfacial barrier against aggregation, coalescence, and Ostwald ripening [

1,

2,

3]. Compared to emulsions stabilized by small molecule surfactants, Pickering emulsions prepared with stabilizers are more stable, biocompatible, and environmentally friendly. Such attributes have been demonstrated in several industrial applications, including the food industry [

4]. Given the safety concerns, previous research on solid particles utilized in Pickering emulsions has mainly focused on food-grade materials such as polyphenols [

5], fats [

6], proteins [

7], polysaccharides [

8,

9], and their complex [

10,

11,

12]. Among these, proteins are ideal candidates due to their molecular characteristics [

13], accessibility, biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity, and high nutritional value [

14,

15]. However, proteins are prone to structural swelling, denaturation, and aggregation when adsorbed at the oil/water interface, leading to emulsion destabilization [

16]. Polysaccharides, on the other hand, offer promising potentials to stabilize emulsions by preventing the agglomeration of oil phases through their spatial structure and viscosity-enhancing ability [

13]. Common polysaccharide stabilizers include starch [

17,

18], cellulose [

19,

20], chitosan [

21,

22], and chitin [

23,

24].

Chitin, an insoluble natural polysaccharide with a highly ordered crystal structure composed of N-acetyl-2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose units linked by β-(1, 4) glycoside bonds [

25], is widely found in the exoskeleton of marine invertebrates. With millions of tons of seafood waste produced worldwide, their disposal poses a serious threat to the environment and human health [

26]. Therefore, it is urgent to develop sustainable methods for treating seafood waste and realize its value-added potential. Conventional chemical extraction techniques, which typically employ HCl, are harmful to the environment due to the last step of chemical waste disposal [

27]. For the sake of environmental protection, Rahayu et al. investigated the physicochemical properties of chitin extracted using HCl and three other acids (H

2SO

4, HNO

3, and CH

3COOH) [

28]. The results showed that high crystallinity index and large porous size morphology were obtained using strong acids other than CH

3COOH, which was attributed to the low ability of weak acids to remove amorphous regions. While phosphoric acid (PA) is known to be an environmentally friendly and moderately strong acid, yet to date, there have been no studies investigating its potential for hydrolyzing chitin. We hypothesize that PA is a promising candidate for chitin hydrolysis extraction.

It has been proven that chitin nanocrystals (ChNCs), nanofibers (ChNFs), and nanoparticles (ChNPs) are effective stabilizers for fabricating stable emulsions. Cheikh et al. prepared ChNCs using H

2SO

4 hydrolysis, and used them to stabilize O/W emulsions of three types of oils [

29]. Kaku et al. obtained ChNFs by HCl hydrolysis and used them for emulsion preparation [

30]. Additionally, Bai et al. stabilized O/W Pickering emulsions using ChNPs as emulsifiers at a low concentration of 0.0005 wt% and investigated the effect of ChNPs axial ratios on the emulsion stability [

31]. Different processing techniques may produce nano chitins of varying shapes, sizes, and properties. In this study, a novel green extraction technique using PA was developed to produce ChNCs (defined as PA-ChNCs). Thereafter, their properties were characterized and their effects on emulsion stability were evaluated, systematically.

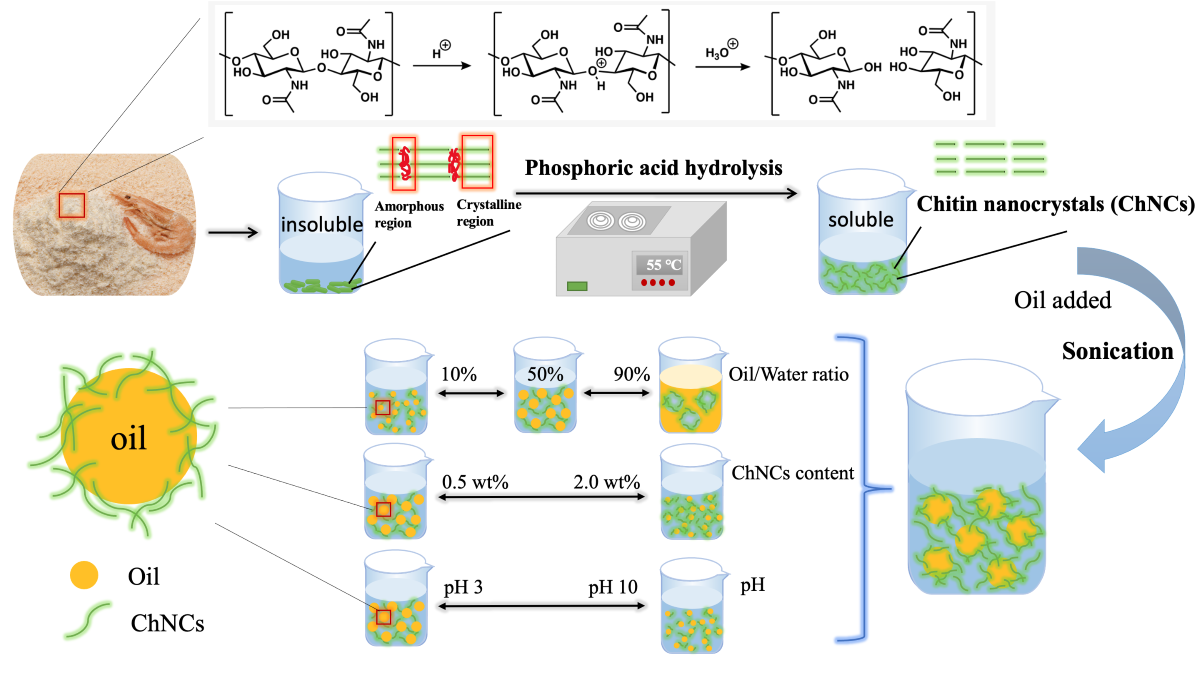

In detail, PA-ChNCs were obtained from shrimp shells by PA hydrolyzation. Morphological and physicochemical properties of PA-ChNCs were comprehensively characterized using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscope, scanning electron microscope (SEM), small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS and WAXS), dynamic light scattering (DLS) and Zetasizer. For the first time, the study demonstrated the use of PA-ChNCs as stabilizers for producing Pickering emulsions. The effects of O:W ratio, PA-ChNCs concentration, and pH on their emulsification ability and emulsion stability were systematically investigated. The rheological behavior of Pickering emulsions stabilized by PA-ChNCs was explored by rheometer and the stabilization mechanism was investigated using confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM). The results of this study are highly valuable for the development of sustainable and eco-friendly stabilizers for fabricating Pickering emulsions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Chitin powder extracted from shrimp shells was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) and was purified before use. PA (65 wt%), HCl, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Calcofluor White Stain, and Nile red were all reagent grade and supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) oil was purchased from Amazon and used without further purification. Deionized water (DI water) was used unless specified.

2.2. Preparation of PA hydrolyzed chitin nanocrystals

Chitin was purified according to a procedure described in a previous study [

32]. After purification, 3 g of purified chitin powder was mixed with 10 g of PA (65 wt%) and the mixed dough was placed in tubes and sealed. The tubes were then immersed in an ultrasonication (40 kHz 130 W) water bath (Branson 2510R-DTH, Danbury, CT, USA) at 55 °C for 2 h. The mixture was then thoroughly washed with distilled water and the supernatant was removed by centrifugation (8235 ×

g for 10 min) at room temperature. To remove the residual acid, the PA-ChNCs suspension was dialyzed using dialysis membranes (10K MWCO) in DI water until a constant pH of 6.28 was achieved. Thereafter, the suspension was stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

2.3. Characterization of PA-ChNCs

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

PA-ChNCs powder was obtained by freeze-drying. The measurement was carried out using a Jasco FTIR 4100 spectrometer (Jasco Inc., Easton, MD, USA) under attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode at room temperature. All spectra were collected between 550 and 4000 cm–1 with a resolution of 2 cm–1.

Small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS and WAXS).

SAXS and WAXS experiment was performed using an integrated SAXS/WAXS in-house instrument (XEUSS 2.0 Xenocs, France). X-ray wavelength (λ) was 1.54 Å, and the beam diameter was 0.5 mm. The sample-to-detector distance was 1756 mm for SAXS and 133 mm for WAXS. SAXS was used to determine the cross-sectional sizes of PA-ChNCs in dilute aqueous suspensions with a concentration of 0.2 % (mass fraction). A flow cell was used as solution sample holder which ensured robust scattering background subtraction. Data analysis was based on fitting the 1D scattering profile using a parallelized form factor model, which has been reported elsewhere [

23]. Cross-sectional sizes of PA-ChNCs were parameterized by width

and thickness

of a rectangle.

Crystalline structure and degree of crystallinity were characterized using WAXS. Powder samples of purified chitin and PA-ChNC were loaded in Kapton tubes with a diameter of 0.8 mm. The tubes were sealed with paraffin wax, allowing the samples to be measured in a vacuum environment. The scattered intensity in a

-range between ~0.5 and ~2.8

Å was defined as

= (4π/λ)sin(θ), with λ and 2θ being the X-ray wavelength and the scattering angle, respectively. The crystalline index (CrI) was calculated with Eq.(1), where

Apeaks is the area of crystalline chitin and

Aamorph is the area of for amorphous chitin.

Morphological characterization.

The morphology of PA-ChNCs was examined by a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Tescan XEIA FEG SEM, Brno, Czechia). The PA-ChNCs powder was first coated with gold sputtering for 70 s, then observed by SEM. The SEM micrographs were acquired at 10.0 kV and a working distance of 5.38 mm. A representative image was presented for each treatment.

Particle size and zeta potential (ζ) measurement.

The obtained PA-ChNCs suspensions were diluted to 0.01 wt%, and the pH was adjusted to 3, 5, 7, 9, and 10 with 0.1M HCl and/or 0.1M NaOH. The hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index (PDI), and electrophoretic mobility of PA-ChNCs were measured with DLS (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, NY, USA) and Zetasizer Ultra (Malvern Instruments, UK) at 25 °C. Particle size distribution was determined by intensity frequency and zeta potential was calculated through the Smuluchowski equation.

2.4. Preparation of O/W Pickering emulsions

PA-ChNCs suspensions with various solid concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 wt%) were prepared by diluting stock suspension (4.5 wt%). The suspensions were adjusted to pH 3, 5, 7, 9, and 10 using 0.1M HCl and/or 0.1M NaOH. The appropriate amount of MCT oil was added to PA-ChNCs suspensions at ratios of 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90% (w/w). The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and then sonicated at 40% amplitude for 2 min in an ice bath, with 1 s of sonication and 1 s of standby.

2.5. Characterization of Pickering emulsions

Creaming index.

The creaming index (CI) is considered as the proportion of the aqueous layer to the total volume of the emulsion, which is employed to assess emulsion stability. Based on a previous study [

33], a digital diameter meter was used to measure the thickness of the aqueous phase, and the volume of the emulsion was calculated based on the diameter of the vial. The CI was analyzed at different O:W ratios, PA-ChNCs concentrations, and pH values. The CI was calculated using Eq. (2), where

Va and

Vt are the volumes of the aqueous layer and the total sample system, respectively.

Droplet size and zeta potential measurement.

Droplet size of the Pickering emulsion was observed using an optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 50 × magnification. The microscope images of droplets were then processed by image J software. The droplet diameters were calculated using Origin lab and fitted with the Gauss function, and statistical analysis was performed. Each Pickering emulsion was diluted 100 times with DI water and images were captured. Three images were randomly taken and at least 20 droplets in each image were counted to obtain the droplet size distribution. The zeta potential of Pickering emulsions was detected using electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) (Zetasizer Ultra, Malvern, UK) at 25 °C [

34]. The measured electrophoretic mobility was used to calculate zeta potential by the instrument via the Smuluchowski equation [

35]. Each Pickering emulsion was characterized by diluting 500 times with DI water to minimize multiple scattering effects.

Rheological properties.

The rheological properties of Pickering emulsion were determined at 25 °C using a Discovery HR-2 rheometer (TA Instruments Ltd., DE, USA.) with a steel parallel plate (25 mm diameter, gap 100 μm). To start the measurement, the emulsions were settled on the plate until temperature equilibrium was reached. The steady-state flow measurements were conducted with shear rates ranging from 0.1 to 100 s-1, and the apparent viscosity (η) was obtained by using TA data analysis software. The dynamic tests were conducted within the linear viscoelastic region, and the frequency test was conducted with a stress value of 1 Pa. A frequency range of 0.1 to 100 rad/s was used, and a strain of 1% was applied. The elastic modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) were recorded versus frequency to determine the degree of flocculation in the emulsion system.

Pickering emulsion microstructure.

An investigation of the interfacial structure of Pickering emulsion droplets was carried out using a Zeiss LSM 980 Airyscan 2 confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Zeiss, Germany) with a 63× oil lens. A 50% (mass fraction) O/W Pickering emulsion was prepared and double stained with Nile red and calcofluor white. The stained emulsion was diluted 100 times with DI water and then placed on concave microscope slides covered with a glass coverslip at 25 °C [

35]. Nile red was used to stain the oil phase and calcofluor white was applied to dye PA-ChNCs. CLSM was performed at an excitation spectrum of 561 and 405 nm for Nile red and calcofluor white, respectively.

To further determine the structure of the Pickering emulsion interface, polarized light microscopy (Olympus, Japan) was employed at 50× magnification. A 50% (mass fraction) O/W Pickering emulsion was diluted with DI water and then located on concave microscope slides covered with a glass coverslip at room temperature [

36]. By rotating the polarizer, the interfacial structure of Pickering emulsion droplets was characterized, and the microscope image was captured by a camera.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Each measurement was conducted three times and presented as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). The differences were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for statistical significance (p<0.05) using SAS software (Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterizations of PA-ChNCs

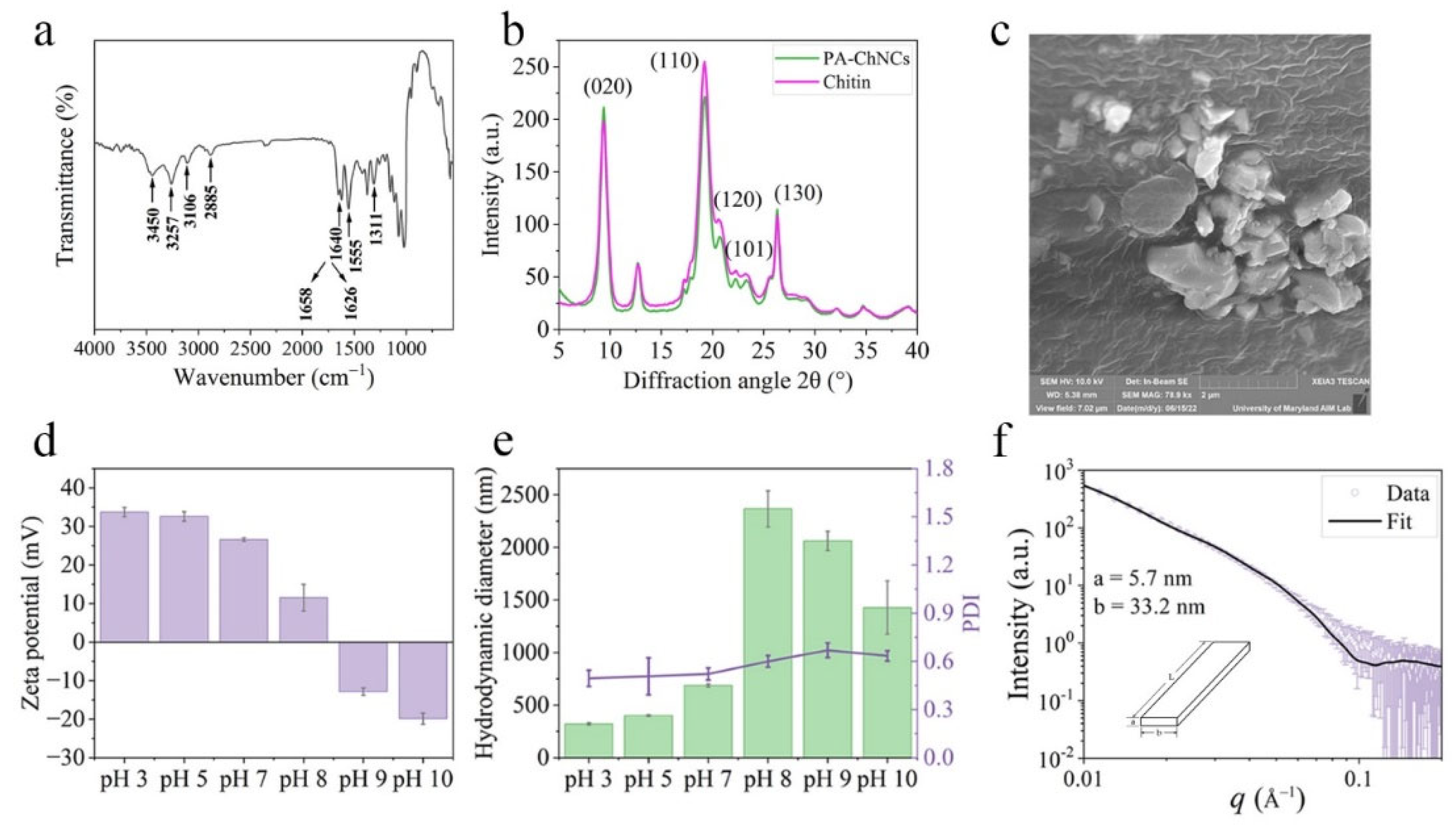

In this study, PA-ChNCs were prepared by hydrolyzing chitin powder with PA. The obtained PA-ChNCs were characterized by FTIR, SAXS, WAXS, SEM, Zetasizer, and optical tensiometer. The results indicated that the PA-ChNCs were crystalline with a high degree of hydrophilicity.

3.1.1. FTIR

FTIR analysis of PA-ChNCs was performed and results were shown in

Figure 1a. Characteristic peaks of chitin were observed at 3450 cm

−1 for the O-H stretching, 3257 cm

−1 for the N-H stretching, and 2885 cm

−1 for the C-H stretching vibration bands. Furthermore, three amide peaks were identified at 1640, 1555, and 1311 cm

−1, which were attributed to amide I (C=O stretching), amide II (C-N-H stretching and N-H bending), and amide III (C-N stretching), respectively. The amide I band was split into two distinct peaks, which were attributed to hydrogen bonding. One of them was the intermolecular hydrogen bonding between acetylamide groups (C-O⋯H-N) at 1658 cm

−1. The other one was intramolecular hydrogen bonding between acetylamide C=O and C6 hydroxyl group (-OH) at 1626 cm

−1. The above results were consistent with previous studies [

28,

32,

37].

3.1.2. XRD

The crystalline structure of PA-ChNCs was examined by XRD. As shown in

Figure 1b, two diffraction peaks at 9.4° and 19.3° were absorbed, indexed as (020) and (110), respectively. Furthermore, three characteristic crystalline planes were identified at 20.8°, 23.3°, 26.3°: (120), (101), and (130). These peaks were in accordance with the unique characteristic diffraction patterns reported for α-chitin [

28]. The crystalline structure of the extracted chitin remained unchanged. The reason is that acid hydrolysis may remove amorphous regions by swelling and acidification, but highly crystalline regions were untouched and maintained their integrity because of inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonding networks [

27]. The crystallinity of PA-ChNCs (83.1%) was higher than that of bulk chitin (80.0%), indicating that the phosphoric acid hydrolysis in this study is a promising method for chitin processing given its great capacity to remove amorphous region.

3.1.3. SEM

SEM was used to observe the surface morphology of PA-ChNCs, which was shown in

Figure 1c. PA-ChNCs exhibited rock-like surfaces. This agreed with those reported in a previous study [

24]. After ultrasonic treatment, the network structure comprising cross-linked and well-defined fibers was shattered and fractured into nanocrystals. However, a slight agglomeration of nanocrystals was observed, which could be a formation of hydrogen bonds by PA-ChNCs during the freeze-drying process, leading to irreversible aggregation [

38].

3.1.4. Particle size and zeta potential of PA-ChNCs

The zeta potential is a crucial parameter for assessing the stability of emulsions.

Figure 1d depicts the zeta potential of PA-ChNCs from pH 3 to 10. The results showed that PA-ChNCs exhibited a positive charge in the pH range of 3 to 8, which can be attributed to the protonation of the primary amine groups resulting from partial deacetylation of chitin in an acidic environment. The zeta potential of PA-ChNCs reached its highest value of 33.7 ± 1.2 mV at pH 3, and the lowest value of 11.5 ± 3.5 mV at pH 8. At pH values of 9 and 10, the surface was negatively charged, indicating that zeta potential of PA-ChNCs approached 0 mV when pH was around 8 to 9. This observation is in accordance with an earlier report [

39].

Particle size is also an essential indicator that affects emulsion stability.

Figure 1e shows the hydrodynamic diameter and PDI of PA-ChNCs at pH levels ranging from 3 to 10. The results indicated that under acidic conditions, PA-ChNCs exhibited higher hydrophilicity due to their stronger positive charges, leading to a better dispersion in water. This was further supported by the contact angle measurement, which was about 30° at pH values below 7 (

Figure S1). The smallest hydrodynamic diameter of PA-ChNCs was observed at pH 3 (321.5 ± 10.5 nm, PDI = 0.49 ± 0.05). The hydrodynamic diameter gradually increased with a decrease in zeta potential. At pH 8 (ζ = 11.53 ± 3.48 mV) and above, a considerable aggregation of PA-ChNCs occurred, evidenced by an increase in their average diameters ranging from 1428.0 ± 253.2 to 2366.7 ± 171.6 nm. Similar results were reported in another study [

39]. However, as the hydrodynamic diameter is not the true size of nanoparticles, we further analyzed PA-ChNCs using SAXS.

Figure 1f reveals that PA-ChNCs were rod-like in shape with a cross-sectional thickness

a of

5.7 nm and width

b of

33.2 nm at pH 7. The length

L was much larger than

a or

b and exceeded the detection limit of SAXS, as indicated by the DLS data (686.7 ± 14.9 nm).

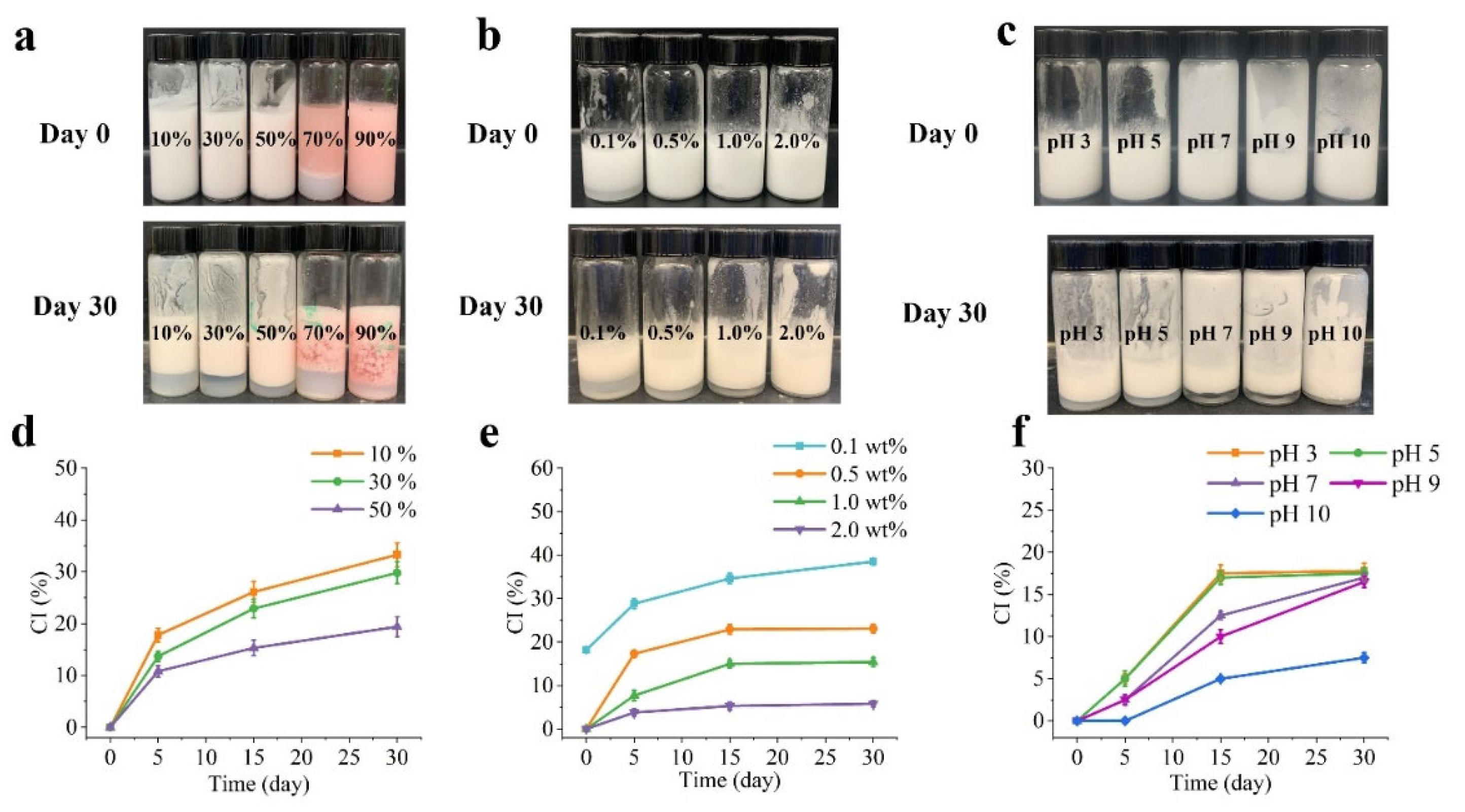

3.2. Macroscopic characteristics and storage stability of Pickering emulsions

Figure 2 illustrates the macroscopic characteristics of Pickering emulsions with different oil fractions (10, 30, 50, 70, and 90%), stabilized by PA-ChNCs that have various concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 wt%) and pH values (3, 5, 7, 9, 10). It was observed that O/W emulsions were formed by 1.0 wt% of PA-ChNCs at oil fractions lower than 50%; whereas at oil fractions exceeding 70%, W/O emulsion systems were created, as confirmed by CLSM. After 30 days of storage, phase separation occurred in all emulsions (

Figure 2a). CI increased gradually over time, from 0% to between 19.4 ± 1.9% and 33.3 ± 2.3%. Notably, the CI exhibited a slower growth rate as the O:W ratio increased from 10% to 50%, indicating better stability of the 50% O/W emulsion in retarding separation and reducing CI (

Figure 2d). The concentration of PA-ChNCs also played a crucial role in emulsion formation.

Figure 2b demonstrates that a fresh emulsion with 0.1 wt% of PA-ChNCs immediately exhibited layering, with CI rising from 18.2 ± 0.5 % to 38.5 ± 0.7 % within 30 days (

Figure 2e). However, the CI growth rate was found to decrease markedly with increasing PA-ChNCs content. At a low concentration of PA-ChNCs (e.g., 0.5 wt%), creaming increased over time (from 0% to 23.1 ± 1.0 %), which was attributed to the limited particles to stabilize a large volume of oil droplets, leading to collapse of the internal structure due to gravity. In contrast, the emulsion with 2.0 wt% PA-ChNCs showed negligible demulsification or gravitational separation during storage (CI=5.8 ± 0.7 % after 30 days of storage). This can be explained by Stokes’s law, where emulsions with high viscosity and small droplet sizes can inhibit gravitational separations. Additionally, the strong Brownian force (repulsive force) between emulsion droplets prevented their flocculation and coalescence [40], which is consistent with other reports [

33]. Furthermore, particle size and zeta potential of PA-ChNCs exhibited significant differences at different pH values, as discussed in section 3.1.4. Hence, to investigate the effect of pH on emulsion stability, Pickering emulsions with 50% O:W ratio were prepared using 1.0 wt% of PA-ChNCs and adjusted to pH values between 3 and 10. Obviously, emulsions were formed at all pH values, but varying degrees of layering were observed after 30 days (

Figure 2c). It is noteworthy that CI increased over time and reached a minimum value at pH 10 (7.5 ± 0.6 %), while no significant differences were observed at other pH levels (

Figure 2f). This trend could be attributed to the interplay between droplet size, zeta potential, and viscoelastic properties of emulsions.

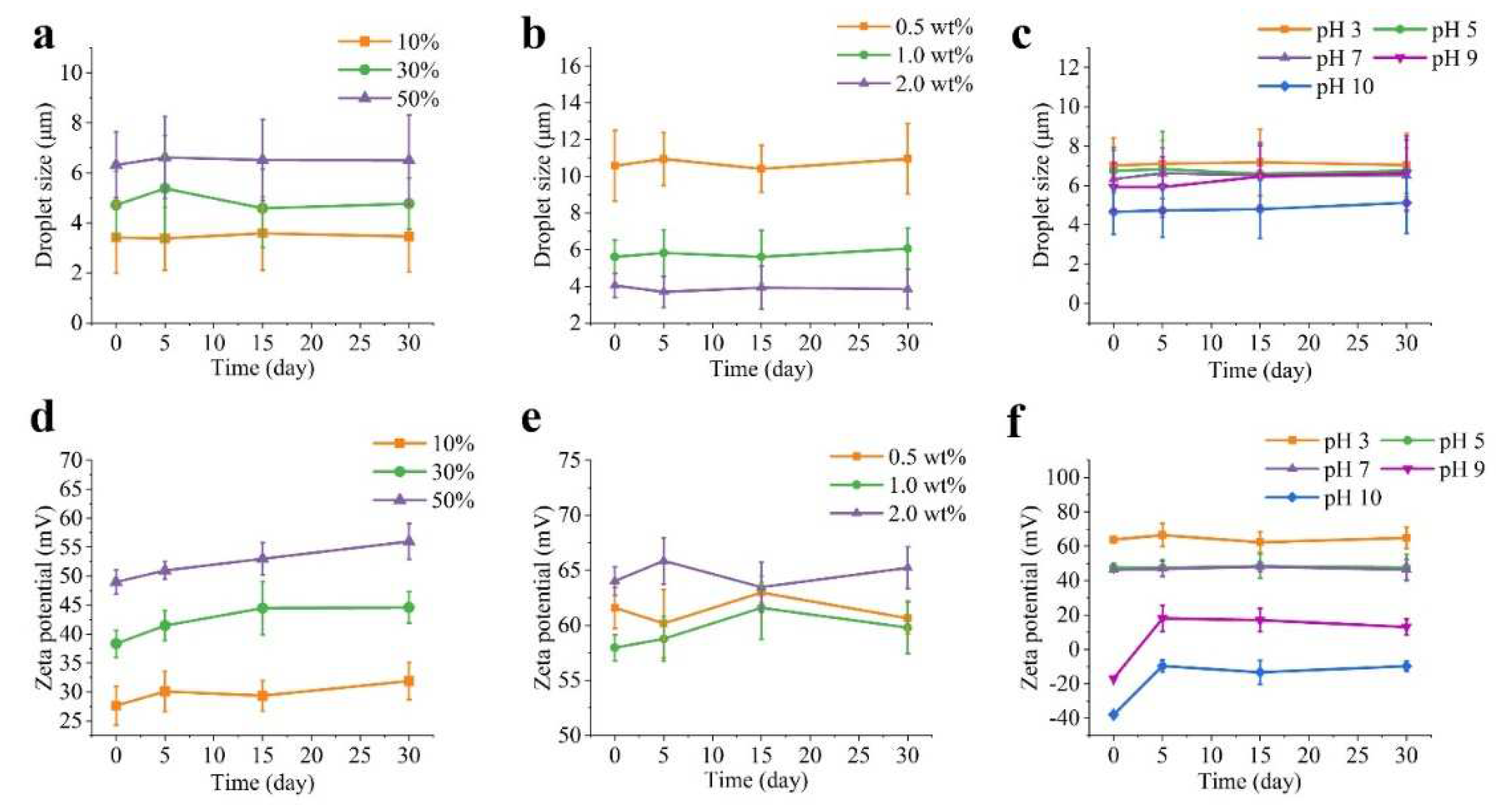

3.3. Physicochemical properties of Pickering emulsions

Figure 3. illustrates the impact of various factors on the droplet size and zeta potential of the Pickering emulsions. The droplet size increased progressively from 3.23 ± 1.42 to 6.32 ± 1.32 µm as oil fractions increased from 10% to 50% (

Figure 3a). This could be explained by the elevated oil fraction and the corresponding decrease in water phase volume resulting in less water available per unit of oil where PA-ChNCs failed to disperse and pack at the interface, leading to the formation of large droplets. Furthermore, high O:W ratios resulted in increased interfacial tension, making oil difficult to form smaller droplets, also the increased viscosity of the oil phase can make it more challenging to generate sufficient shear forces to create smaller droplets. Consequently, a deficiency of PA-ChNCs at the O/W interface leads to larger droplets. This finding aligns with previous reports [

41,

42]. Generally, emulsions with small droplet sizes tend to be more stable than those with large droplet sizes. However, there was no significant change in droplet sizes for all emulsions after 30 days of storage at 4 °C in this study. This may be due to the consequence of the combined effect of various factors. Moreover, PA-ChNCs concentrations significantly affected droplet size of oil, with a dramatic decrease as PA-ChNCs concentration increased from 10.58 ± 1.93 µm (0.5 wt %) to 4.05 ± 0.64 µm (2.0 wt %), whereas the 0.1 wt% PA-ChNCs failed to form an emulsion and hence was not included in the discussion (

Figure 3b). It was thought that the emulsion with 2.0 wt% PA-ChNCs closely arranged adjacent droplets, some of which slightly overlapped. This was attributed to the formation of a three-dimensional solid-like network in Pickering emulsions, which led to small droplet sizes and exhibited gel properties due to excess PA-ChNCs. Increasing PA-ChNCs concentration may enhance crosslinking within the network, thereby forming a more compact structure [

43]. It was observed that the droplet size of emulsions with all concentrations of PA-ChNCs remained relatively stable over time. As another factor affecting the emulsion stability, the increase in pH from 3 to 10 decreased the droplet size from 7.02 ± 1.40 µm to 4.66 ± 1.14 µm. Moreover, there was no significant change in droplet size after 30 days of storage, with droplet size remaining minimal at pH 10 (5.12 ± 1.58 µm) and maximal at pH 3 (7.04 ± 1.62 µm).

Zeta potential, an indicator of emulsion stability, was found to vary depending on the oil fraction (

Figure 3d). Emulsions with a high oil fraction (50%) exhibited a high zeta potential (49.0 ± 2.1 mV), suggesting enhanced stability. The zeta potential showed a slight variation among the different PA-ChNCs concentrations (

Figure 3e), with 2.0 wt% displaying a slightly higher zeta potential (64.0 ± 1.3 mV) compared to 0.5 wt% (61.6 ± 1.9 mV) and 1.0 wt% (58.0 ± 1.2 mV) at day 0. No significant change occurred after storage of 30 days in all emulsions. Consequently, emulsions with 2.0 wt% PA-ChNCs displayed superior stability compared to those with lower concentrations. As expected, the positive zeta potential of the emulsion at pH values below 7 clearly indicated partial deacetylation of chitin. The values were all above 30 mV and showed no significant change during the 30 days of storage. In contrast, fresh emulsions at pH 9 and 10 showed negative charges due to the ionization of the carboxyl groups and hydroxyl groups. The decrease in absolute charge after 5 days may be due to the aggregation of PA-ChNCs at pH higher than 8, which interferes with hydroxyl groups contact with hydroxyl ions and thus ionization, as well as low-temperature storage that prevents ionization by impeding molecular mobility. It is worth noting that the zeta potential of the emulsion was lowest at pH 9, possibly due to the proximity to ~0 mV of PA-ChNCs (

Figure 3f).

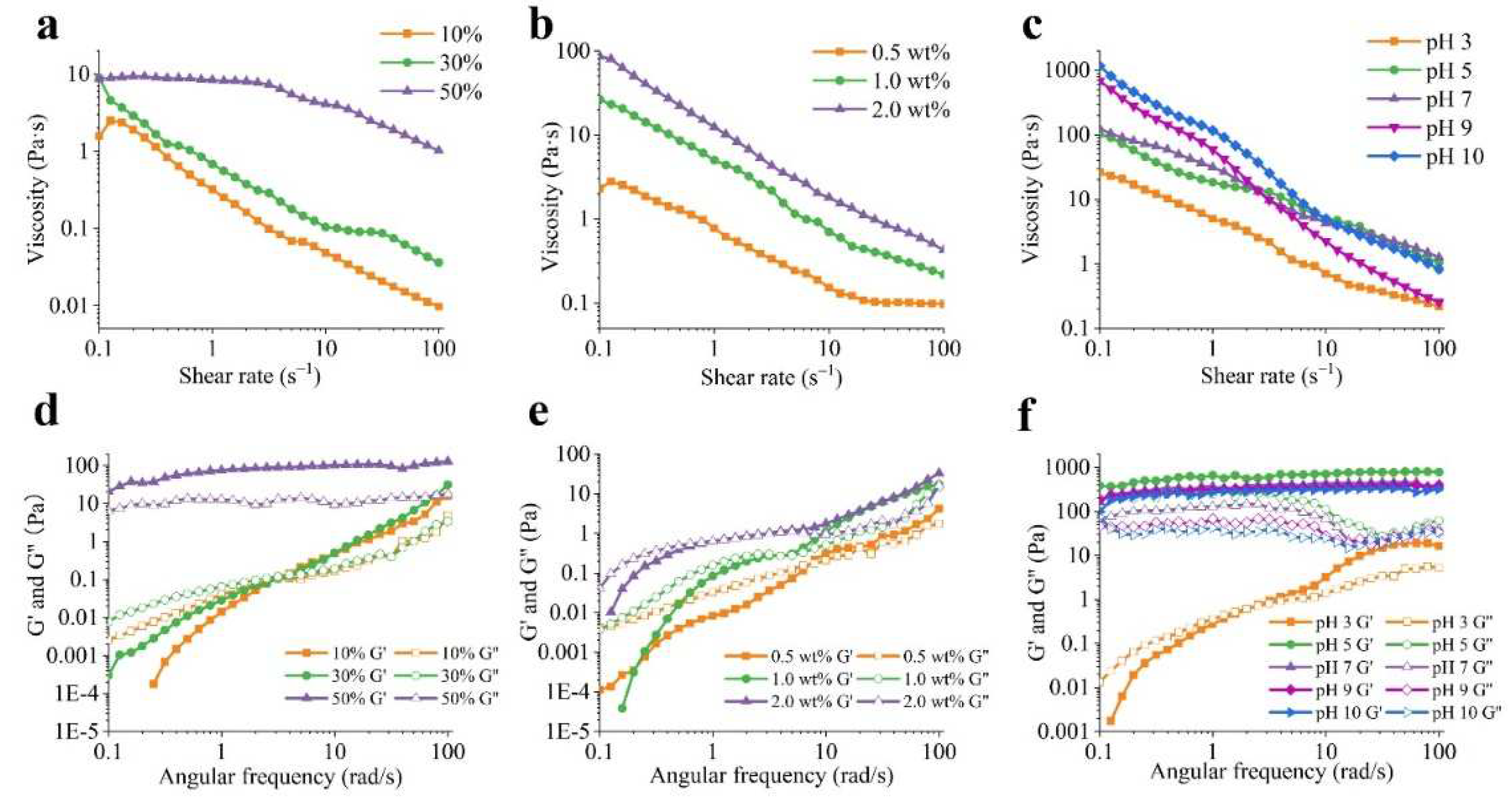

3.4. Rheological characterization of Pickering emulsions

The rheological properties of emulsions are important indicators of their stability characteristics.

Figure 4a demonstrates that the viscosity of emulsions decreased as shear rate increased, indicating that the emulsions displayed shear-thinning behavior. Increasing the oil fractions from 10% to 50% resulted in a progressive increase in viscosity at the same concentration of PA-ChNCs (1.0 wt%) and pH 7. The increase in viscosity of emulsions can be primarily attributed to the escalation in the concentration of droplets. The presence of droplets hampers the fluid flow, leading to an increase in energy dissipation. At high oil content, the viscosity rise can also be ascribed to the increased droplet flocculation, which enhances the effective volume fraction of droplets and thus, viscosity [44]. It is noteworthy that emulsions containing 50% oil initially exhibited Newtonian behavior, followed by a shift to shear-thinning behavior due to bulk coalescence [45]. The above results are consistent with the observation that increasing oil fraction enhanced the physical stability of emulsions [42,46]. To further elucidate the gel structure of the emulsions, dynamic oscillatory measurements were conducted (

Figure 4d). The storage modulus (G′) was found to be higher than the loss modulus (G′′) in the frequency range of 0.1 to 100 rad/s for the 50% O/W emulsion, indicating that Pickering emulsion exhibited an elastic gel-like structure. In contrast, for the 10% and 30% O/W emulsions, G′′ was higher than G′ at low frequency, suggesting the formation of liquid-like emulsions. This result was consistent with viscosity data. A crossover was observed in the 10% and 30% O/W emulsions where G′ = G′′, indicative of viscoelastic energy and the presence of a gel matrix. Subsequently, G' exceeded G'' as frequency increased, indicating the development of a gel-like matrix. Several other studies [41,45] also reported G′ > G′′ for emulsions with 50%, 60%, and 70% oil content, confirming the existence of an elastic gel network. G′ and G′′ gradually increased with increasing oil content, possibly as a consequence of an increase in the relative density of the emulsion droplets, resulting in a higher G′.

Figure 4b shows that increasing the PA-ChNCs content in the emulsions at the same O:W ratio (50%) resulted in an increase in viscosity due to the thickening effect of PA-ChNCs in the continuous phase. This finding is consistent with emulsions thickened by other polysaccharides [47]. The viscoelastic properties of the emulsions were frequency-dependent, with both G′ and G′′ increasing with frequency (

Figure 4e). At low frequencies, where G′′ was greater than G′, the emulsions behaved as viscous fluids. As the frequency increased, G′ surpassed G′′, contributing to solid-like behavior [48].

Furthermore, the viscosity of the emulsions increased with increasing pH values (

Figure 4c). At pH 10, PA-ChNCs in the continuous phase presented a high WCA (50.7 ± 3.7°,

Figure S1), allowing them to adhere to the surface of the oil droplets, thus enhancing the viscosity of the emulsion. The dynamic viscoelasticity further illustrated the characteristic of emulsion (

Figure 4f). Emulsions with pH 3 mainly exhibited viscous properties at low frequencies, where G′′ was larger than G′, and showed elastic properties as frequency rose. In contrast, emulsions with other pH values exhibited G′ > G′′ at the experimented frequency, indicating the formation of gel-like matrixes.

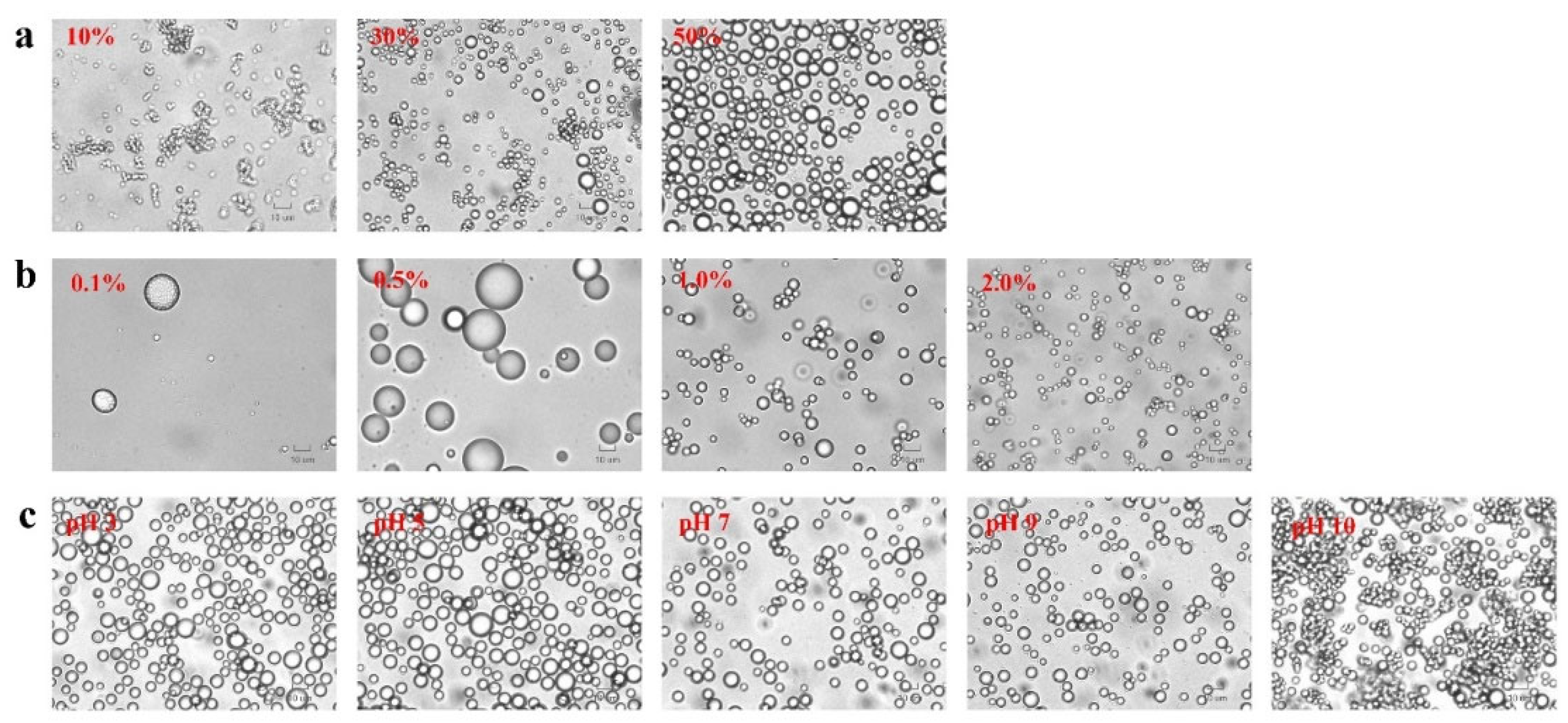

3.5. Morphological structure of Pickering emulsion

Figure 5 revealed the presence of spherical droplets with different sizes and distributed in the continuous phase. This is correlated with the O:W ratios, PA-ChNCs concentrations, and pH values, as discussed in section 3.3. Images of droplets in the emulsion after 30 days of storage were provided in the Supplemental Document (

Figure S2-S4). Apparently, the droplets in 10% emulsion clustered together into large agglomerates and flocculated after 15 days of storage. This resulted in the most unstable emulsion, which separated over time. In contrast, the droplets in 30% emulsions showed some aggregation, while those in 50% emulsions remained separated and evenly dispersed. The droplets of emulsions with different PA-ChNCs concentrations were uniformly distributed but flocculated to some extent. A similar phenomenon was observed in emulsion of various pH values.

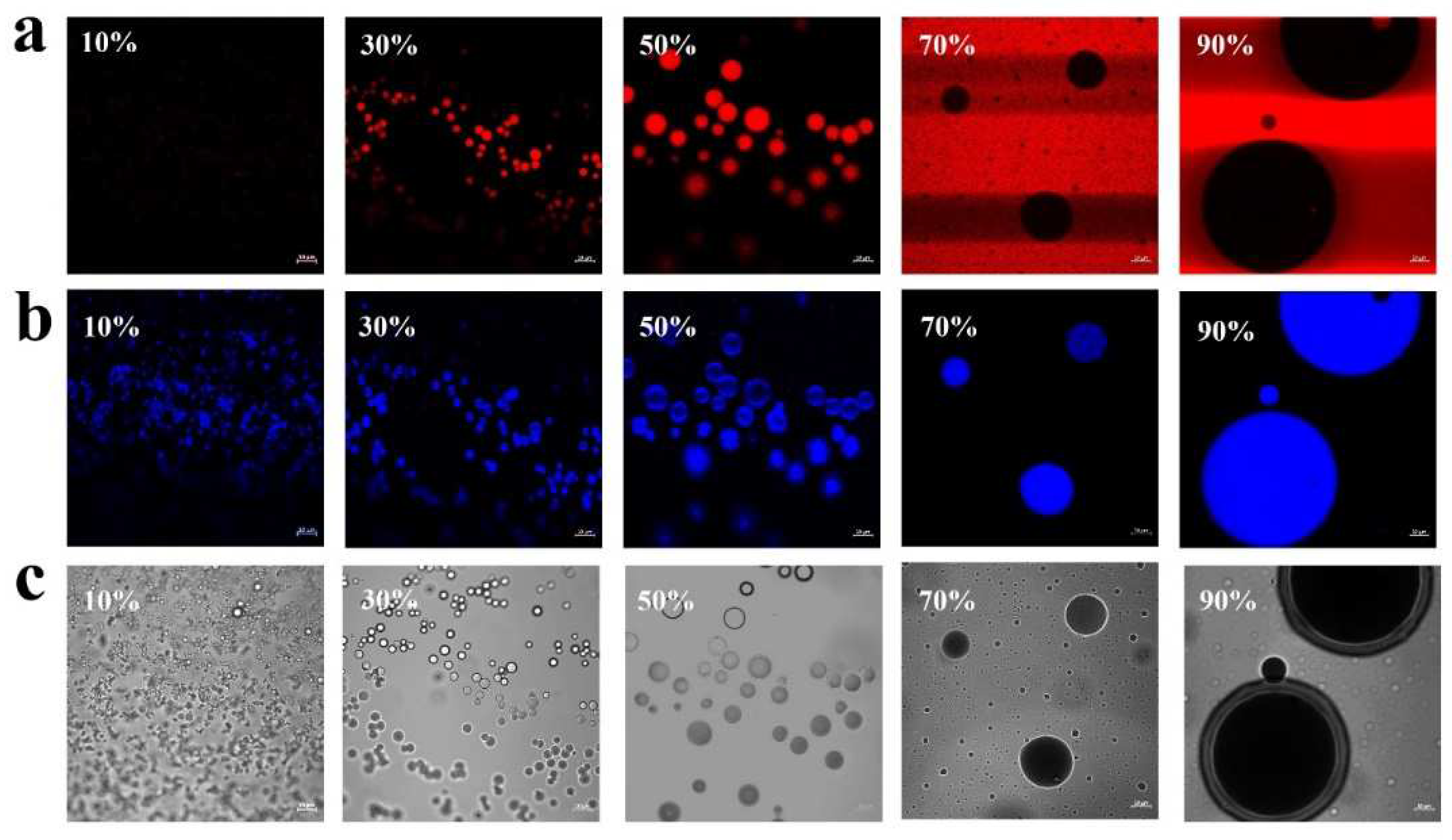

To elucidate the formation mechanism for Pickering emulsions, the microstructure of Pickering emulsions made from various O:W ratios was visualized using CLSM technique. The results were presented in

Figure 6, where Nile red and Calcofluor white were used to stain the oil phase (red) and PA-ChNCs (blue), respectively. CLSM observations revealed that emulsion microstructure varied considerably depending on the O:W ratios. O/W Pickering emulsions were formed at ratios below 50%, while W/O systems were found at ratios of 70% and 90%. The stabilization mechanism of Pickering emulsions was well established and arose from the interfacial packing of adsorbed particles, which formed a robust mechanical barrier that impeded droplet coalescence. This mechanism was evident in 50% O/W emulsions, where the PA-ChNCs were observed absorbing at the oil-water interfaces, creating a stable barrier that effectively hindered droplet coalescence and led to the formation of stable emulsions.

Polarized light microscopy can be used to investigate birefringence based on the difference in refractive index between two perpendicular directions in a crystal. In practice, isotropic materials appear dark when light travels through, while anisotropic ones appear bright in contrast. Since chitin nanocrystals are identified as a strongly anisotropic material, they can be seen brighter under the microscope [49]. As is shown in

Figure S5, a brighter ring shape structure surrounded the round oil droplet, indicating that the PA-ChNCs adhered to the interface of water and oil, forming Pickering emulsions.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a novel eco-friendly method for obtaining chitin nanocrystals was developed by hydrolyzing chitin with phosphoric acid. The composition, structure, morphology, crystal size, zeta potential, and hydrophilicity of PA-ChNCs were characterized. They were highly pH-dependent in terms of their size, surface charge, and hydrophilicity. PA-ChNCs exhibited small particle size, high and positive zeta potential at pH below 8, while the particle size increased significantly and presented negative zeta potential under alkaline conditions. Based on these properties, PA-ChNCs were employed to prepare Pickering emulsions, and the effect of O:W ratio, PA-ChNCs content, and pH on the stability of the emulsions were investigated. Increased oil content (50% O:W) resulted in larger droplet size, higher zeta potential, and increased viscosity. Small droplets with high viscosity were formed by modulating PA-ChNCs content from 0.1 wt% to 2.0 wt% and pH from 3 to 10. Our study proposes a promising approach for fabricating Pickering emulsions with controllability using PA-ChNCs, exhibiting exceptional stability at an O:W ratio of 50%, PA-ChNCs concentration of 2.0 wt%, and alkaline conditions. Furthermore, our efforts may expand the scope of the application of chitin in the food industry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Contact angle of PA-ChNCs from pH 3 to pH 10; Figure S2: Optical micrographs of Pickering emulsions stabilized by 1.0 wt% PA-ChNCs at pH 7 with different oil-water ratios during 30 days of storage; Figure S3: Optical micrographs of 50% O:W Pickering emulsions stabilized by various PA-ChNCs concentrations at pH 7 during 30 days of storage; Figure S4: Optical micrographs of 50% O:W Pickering emulsions stabilized by 1.0 wt% PA-ChNCs at various pH values during 30 days of storage; Figure S5: Polarized light microscopy images of fresh Pickering emulsion stabilized by 0.5 wt% PA-ChNCs with 50% O:W at pH 3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.J. and Q.W.; methodology, X.J. and P.M.; software, K.S.-Y.T.; validation, X.J.; formal analysis, X.J.; investigation, X.J.; resources, Y.M. and Q.W.; data curation, X.J., K.S.-Y.T. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.J.; writing—review and editing, P.M., Y.M. and Q.W.; visualization, X.J.; supervision, Q.W.; funding acquisition, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the Graduate School at the University of Maryland.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Imaging Core Facility of the Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics at the University of Maryland for providing the confocal laser-scanning microscope and Amy Elizabeth Beaven for her help. Purchase of the Zeiss LSM 980 Airyscan 2 was supported by Award Number 1S10OD025223-01A1 from the National Institute of Health. We would like to thank the University of Maryland NanoCenter for providing SEM equipment, and Dr. Jiancun Rao for his help in instrument operation. We would also like to thank Dr. Zi Teng at U.S. Department of Agriculture for his help with contact angle measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The identification of any commercial product or trade name does not imply endorsement or recommendation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

References

- Albert, C.; Beladjine, M.; Tsapis, N.; Fattal, E.; Agnely, F.; Huang, N. Pickering emulsions: Preparation processes, key parameters governing their properties and potential for pharmaceutical applications. J. Control. Release 2019, 309, 302–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Sheng, Y.; Ngai, T. Pickering emulsions: Versatility of colloidal particles and recent applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisuzzo, L.; Cavallaro, G.; Milioto, S.; Lazzara, G. Pickering emulsions stabilized by halloysite nanotubes: from general aspects to technological applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ao, F.; Ge, X.; Shen, W. Food-grade Pickering emulsions: Preparation, stabilization and applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q.; Yi, Z.; Ran, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, G.; Li, X. Green tea polyphenol-stabilized gel-like high internal phase pickering emulsions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 4076–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellari, G. I.; Zafeiri, I.; Batchelor, H.; Spyropoulos, F. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers of dual functionality at emulsion interfaces. Part I: Pickering stabilisation functionality. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 654, 130135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Seah, K.-W.; Ngai, T. Single and double Pickering emulsions stabilized by sodium caseinate: Effect of crosslinking density. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; McClements, D. J.; Luo, S.; Ye, J.; Liu, C. Effect of internal and external gelation on the physical properties, water distribution, and lycopene encapsulation properties of alginate-based emulsion gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 108499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Fan, Y. In vitro digestion properties of different chitin nanofibrils stabilized lipid emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, Z.; Wang, J.; Ruan, Q.; Guo, J.; Yang, X. Fabrication of stable Pickering double emulsion with edible chitosan/soy β-conglycinin complex particles via one-step emulsification strategy. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 138, 108465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Jiang, C.; Huang, Z.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Hong, Y. Formation, stability and the application of Pickering emulsions stabilized with OSA starch/chitosan complexes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 299, 120149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Su, Z.; Meng, X.; Zhang, X.; Kennedy, J. F.; Liu, B. Fabrication and characterization of Pickering emulsion stabilized by soy protein isolate-chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.; Morell, P.; Nicoletti, V.; Quiles, A.; Hernando, I. Protein-and polysaccharide-based particles used for Pickering emulsion stabilisation. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 119, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Li, C.; Shi, X.; Xiao, H. Naturally occurring protein/polysaccharide hybrid nanoparticles for stabilizing oil-in-water Pickering emulsions and the formation mechanism. Food Chem. 2022, 395, 133641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Mu, C.; Ngai, T.; Lin, W. Advances in Pickering emulsions stabilized by protein particles: Toward particle fabrication, interaction and arrangement. Food Res. Int. 2022, 111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H. Globular proteins as soft particles for stabilizing emulsions: Concepts and strategies. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 103, 105664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E. B.; Kim, J.-Y. Application of starch nanoparticles as a stabilizer for Pickering emulsions: Effect of environmental factors and approach for enhancing its storage stability. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pedrouso, M.; Lorenzo, J. M.; Moreira, R.; Franco, D. Potential applications of Pickering emulsions and high internal-phase emulsions (HIPEs) stabilized by starch particles. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 46, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Cui, R.; Lu, S.; Hu, X.; Xu, B.; Song, Y.; Hu, X. High internal phase Pickering emulsions stabilized by cellulose nanocrystals for 3D printing. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 125, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Oguzlu, H.; Baldelli, A.; Zhu, Y.; Song, M.; Pratap-Singh, A.; Jiang, F. Sprayable cellulose nanofibrils stabilized phase change material Pickering emulsion for spray coating application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.; Sun, H.; Mu, T.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Chitosan-based Pickering emulsion: A comprehensive review on their stabilizers, bioavailability, applications and regulations. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 120491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, M.; Rajaei, A.; Hosseini, E.; Aghbashlo, M.; Gupta, V. K.; Lam, S. S. Effect of type of fatty acid attached to chitosan on walnut oil-in-water Pickering emulsion properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Ma, P.; Taylor, K. S.-Y.; Tarwa, K.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Q. Development of Stable Pickering Emulsions with TEMPO-Oxidized Chitin Nanocrystals for Encapsulation of Quercetin. Foods 2023, 12, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Lin, B.; Xu, C.; Lin, M.; Zhan, W. Preparation and characterization of individual chitin nanofibers with high stability from chitin gels by low-intensity ultrasonication for antibacterial finishing. Cellulose 2018, 25, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Ganesan, A. R.; Ezhilarasi, P.; Kondamareddy, K. K.; Rajan, D. K.; Sathishkumar, P.; Conterno, L. Green and eco-friendly approaches for the extraction of chitin and chitosan: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 119349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Lee, S. H.; Kim, J.; Park, C. B. “Waste to wealth”: lignin as a renewable building block for energy harvesting/storage and environmental remediation. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 2807–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Pei, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tang, K. Recent Progress in Preparation and Application of Nano-Chitin Materials. Energy Environ. Mater. 2020, 3, 492–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, A. P.; Islami, A. F.; Saputra, E.; Sulmartiwi, L.; Rahmah, A. U.; Kurnia, K. A. The impact of the different types of acid solution on the extraction and adsorption performance of chitin from shrimp shell waste. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheikh, F. B.; Mabrouk, A. B.; Magnin, A.; Putaux, J.-L.; Boufi, S. Chitin nanocrystals as Pickering stabilizer for O/W emulsions: Effect of the oil chemical structure on the emulsion properties. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2021, 200, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Fujisawa, S.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Synthesis of chitin nanofiber-coated polymer microparticles via Pickering emulsion. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Huan, S.; Xiang, W.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Nugroho, R. W. N.; Rojas, O. J. Self-assembled networks of short and long chitin nanoparticles for oil/water interfacial superstabilization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 6497–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Briber, R. M. Efficient production of oligomeric chitin with narrow distributions of degree of polymerization using sonication-assisted phosphoric acid hydrolysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 276, 118736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Zheng, S.; Li, H.; Luo, D.; Wang, Y. High internal-phase pickering emulsions stabilized by xanthan gum/lysozyme nanoparticles: rheological and microstructural perspective. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liang, R.; Li, L. The interaction between anionic polysaccharides and legume protein and their influence mechanism on emulsion stability. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 131, 107814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Tong, Z.; Dai, L.; Wang, D.; Lv, P.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y. Influence of interfacial compositions on the microstructure, physiochemical stability, lipid digestion and β-carotene bioaccessibility of Pickering emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 104, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, R.; Kondo, T. Favorable 3D-network Formation of Chitin Nanofibers Dispersed in WaterPrepared Using Aqueous Counter Collision. Sen'i Gakkaishi 2011, 67, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurkan, M. V.; Voronkina, A.; Khrunyk, Y.; Wysokowski, M.; Petrenko, I.; Ehrlich, H. Progress in chitin analytics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, M.; Patel, M. K.; De Brauwer, L.; Nair, R.; Montalbano, M. L.; Monti, M.; Oksman, K. Influence of Chitin Nanocrystals on the Crystallinity and Mechanical Properties of Poly (hydroxybutyrate) Biopolymer. Polymers 2022, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parajuli, S.; Hasan, M. J.; Ureña-Benavides, E. E. Effect of the Interactions between Oppositely Charged Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs) and Chitin Nanocrystals (ChNCs) on the Enhanced Stability of Soybean Oil-in-Water Emulsions. Materials 2022, 15, 6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Hao, Y.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Aggregation of egg white peptides (EWP) induced by proanthocyanidins: A promising fabrication strategy for EWP emulsion. Food Chem. 2023, 400, 134019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Sun, C.; Wei, Y.; Mao, L.; Gao, Y. Characterization of Pickering emulsion gels stabilized by zein/gum arabic complex colloidal nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tang, C.-H. Soy glycinin as food-grade Pickering stabilizers: Part. III. Fabrication of gel-like emulsions and their potential as sustained-release delivery systems for β-carotene. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 56, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.-x. , Lei, Y.-c., Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, L.-j. Rheological and structural properties of sodium caseinate as influenced by locust bean gum and κ-carrageenan. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Liu, W.; McClements, D. J.; Zou, L. Rheological, structural, and microstructural properties of ethanol induced cold-set whey protein emulsion gels: Effect of oil content. Food Chem. 2019, 291, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Gonzalez, A. J. P.; Huang, Q. Kafirin nanoparticles-stabilized Pickering emulsions: Microstructure and rheological behavior. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Zeng, Q.; Tai, K.; He, X.; Yao, Y.; Hong, X.; Yuan, F. Preparation of curcumin-loaded emulsion using high pressure homogenization: Impact of oil phase and concentration on physicochemical stability. LWT 2017, 84, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Ban, C.; Goh, K. K.; Choi, Y. J. Enhancement of the gut-retention time of resveratrol using waxy maize starch nanocrystal-stabilized and chitosan-coated Pickering emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Liu, F.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Impact of chitosan–EGCG conjugates on physicochemical stability of β-carotene emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 39, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Cao, X.; Luo, B.; Liu, M. Chitin nanocrystals as an eco-friendly and strong anisotropic adhesive. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 11356–11368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).