1. Introduction

Chitin is a natural polymer that belongs to the group of polysaccharides. It is the main component of invertebrate exoskeletons and occurs in the cell walls of fungi and yeasts [

1,

2,

3]. It is an easily accessible by-product of shellfish production [

4,

5,

6]. Currently, this polymer is increasing in popularity. However, it possesses outstanding properties predisposing chitin to medical applications, including non-toxicity [

7,

8,

9], biodegradability [

10,

11,

12], gel-forming ability [

13,

14,

15] and antibacterial properties [

16,

17,

18]. Chitin is an intervening polysaccharide also due to the presence of (acetyl)-amine and hydroxyl functional groups, which can be modified to produce new materials with assumed properties and functions. However, the insolubility of chitin in common organic solvents is an obstacle to its commercial use [

10,

14,

17]. The solubility, and thus the processability, can be improved by using modifications, including a deacetylation process [

19,

20,

21]. During the deacetylation of chitin, the acetyl group (C

2H

3O) is removed, resulting in the formation of an amino group (NH

2) [

22,

23]. This process starts first in the amorphous regions of the chitin material and then in the crystalline parts [

22,

24]. Through modification of hydroxyl groups, it is possible to obtain chitin derivatives [

25,

26]. Their physical and chemical properties will differ from the initial polymer. Many attempts have been made over the years to modify the hydroxyl groups. One of the derivatives obtained is acetylchitin [

21,

27,

28]. It was acquired by esterification with acetic anhydride. A mixture of 1,2-dichloroethane and trichloroacetic acid was used as solvents for chitin. However, the strongly acidic solvent system used to perform this reaction resulted in the significant degradation of chitin. Bourne [

29,

30,

31,

32] developed a trifluoroacetic acid and organic acid composition, which could also be used to esterify chitin. The reaction yielded chitin monoesters and copolyesters, with acetylchitin as the significant component. Using the solvent combination proposed by Bourne, it was also possible to obtain butyryl derivatives [

33,

34]. Draczynski et al. [

35,

36] also created a way to produce mixed chitin esters. The butyryl-acetyl-chitin esterification reaction was carried out using perchloric acid as a catalyst and a mixture of acetic and butyric anhydrides in an equal molar ratio. Bhatt et al. [

19] used trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA), benzoic acid and phosphoric acid to produce chitin benzoic acid esters. The synthesis of chitin butyrate in the presence of TFAA/H

3PO

4 by reacting chitin with butyric acid has also been reported [

37].

The objective of the study was to determine the effect of the ratio of butyric anhydride to succinic anhydride on the properties of the chitin derivative.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chitin made from shrimp shells in coarse flakes was used as a commercial product of Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, Massachusetts, United States). Methanesulfonic acid (min. 98%), butyric anhydride (min. 98%) and succinic anhydride (min. 99%) were purchased from Pol-Aura (Morąg, Poland).

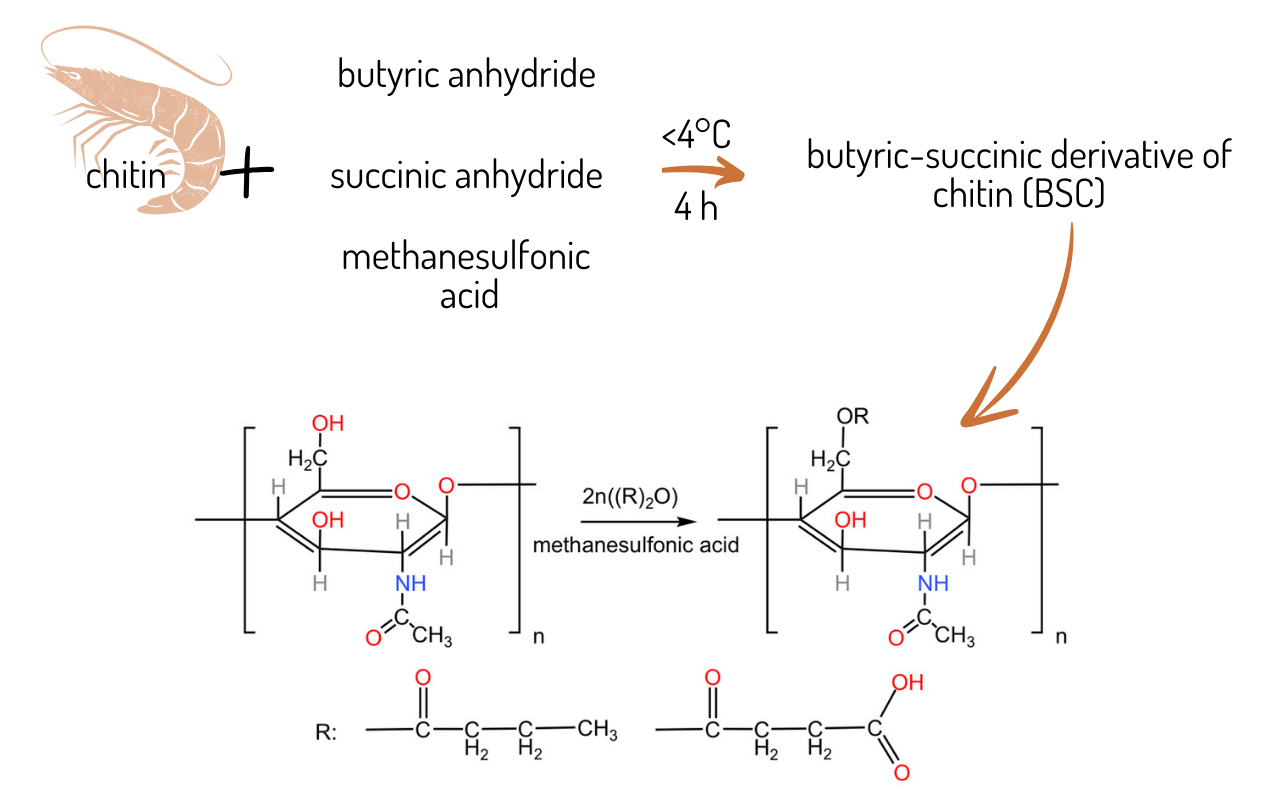

2.2. Synthesis of the butyric-succinic derivative of chitin (BSC)

The chitin used for the synthesis was ground with a ball mill for more rapid and efficient reactions. The grinding speed was 600 rpm, and its one cycle lasted 300 seconds. This process was repeated several times to achieve a more homogenous polymer.

To carry out the syntheses, 25 g of chitin, 100 cm

3 of methanesulfonic acid and succinic and butyric anhydrides in different molar ratios were used (

Table 1). The substrates were introduced into a cooled reactor, followed by adding the pre-cooled catalyst. The reactions proceeded for 4 hours under controlled conditions at a temperature not exceeding 4°C. Frequent stirring was applied to prevent localised overheating of the reaction mixtures. Upon completion of the reaction, the products were neutralised using a 5% aqueous ammonia solution. Subsequently, the materials were rinsed thoroughly with distilled water until the wash water reached a neutral pH, indicating the removal of residual methanesulfonic acid from the synthesised polymers.

Figure 1.

The butyric-succinic derivative of chitin (BSC).

Figure 1.

The butyric-succinic derivative of chitin (BSC).

2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR ATR)

Samples of synthesised polymers in powder form were examined with FTIR ATR analysis to confirm changes in their chemical structure. The study was conducted with the Thermo Scientific, Nicolet 6700 (Waltham, Massachusetts, US), using a resolution of 4 nm; each spectrum was at an average of 64 scans.

2.4. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance ( 1H NMR)

Analysis using

1H NMR Avance II plus (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, Massachusetts, US) operating at the

1H frequency 700 MHz was performed to analyse the chemical structure of the synthesised polymers. The powder-form polymer was dissolved in deuterated DMSO to conduct the study. Based on the measurements, the intensity of selected peaks was determined using the equation below, and these measurements determined the theoretical degrees of substitution:

Where: - integer value of signal intensity, originating from protons in methyl group of butyric/ succinic acid residue; - the integral value of signal intensity in the range of 3.0-4.2 ppm originated from H2 - H6 protons in the glucosamine moiety of the polymer

2.5. Thermogravimetry (TG)

Thermal characterisation tests were performed by differential scanning calorimetry with a thermowell using TG Labsys Evo 1150 (Setaram, France). The tests were performed in a nitrogen atmosphere using a heating rate of 10°C/min over a temperature range of 20°C - 600°C.

2.6. The contact angle

To evaluate the surface properties of the materials, films were prepared from the resulting polymer by casting thin films from a 5% polymer solution in alcohol. This method facilitated the formation of uniform films suitable for subsequent surface characterisation and analysis. The contact angle of copolyester-made polymer films was measured using a Rame-Hart Model 90 goniometer (Rame-Hart, Succasunna, USA) and DROPImage Pro software version 3.19.12.0 (Rame-Hart, Succasunna, USA). Distilled water was used for measurement, and ten repeats were performed for each sample tested.

3. Results

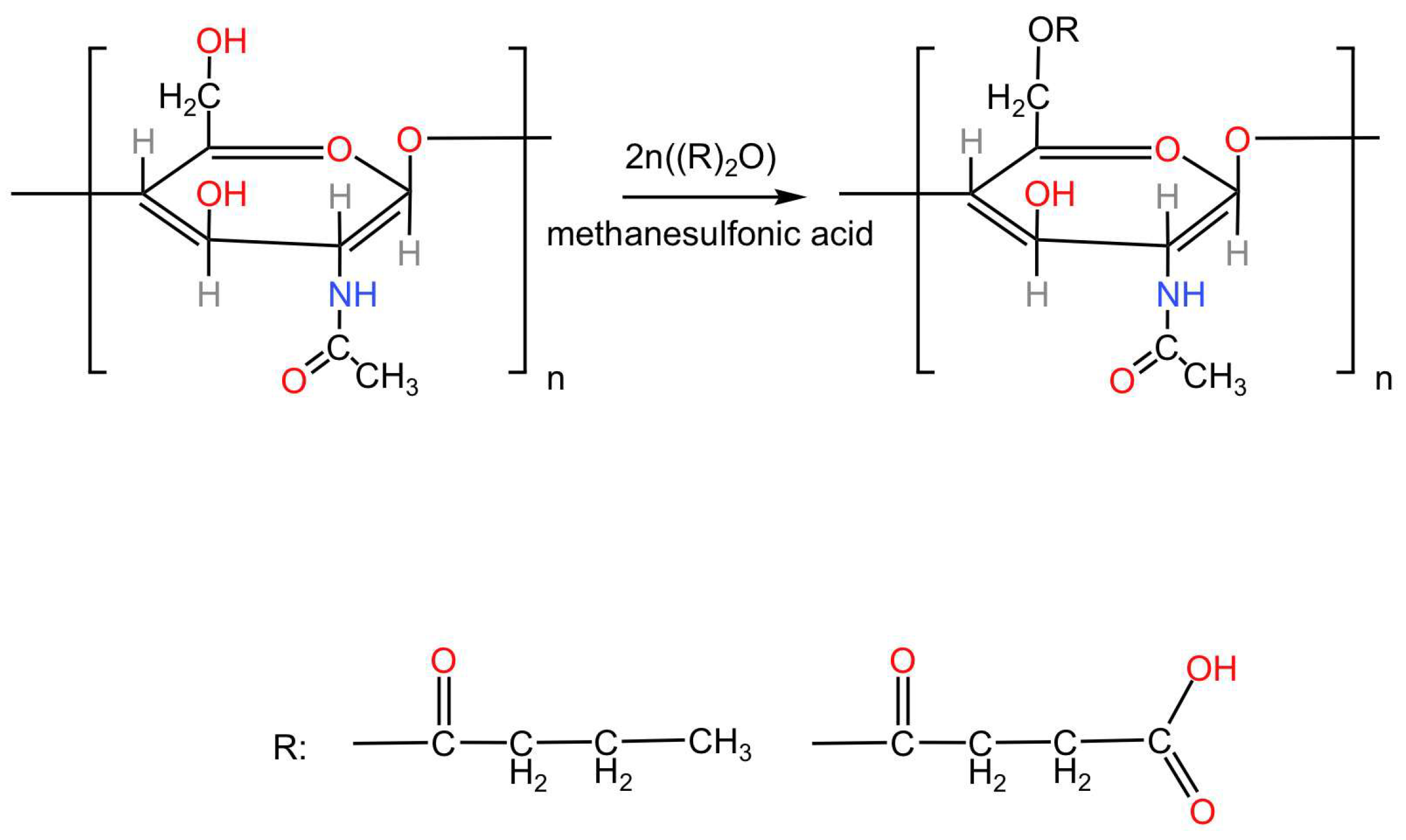

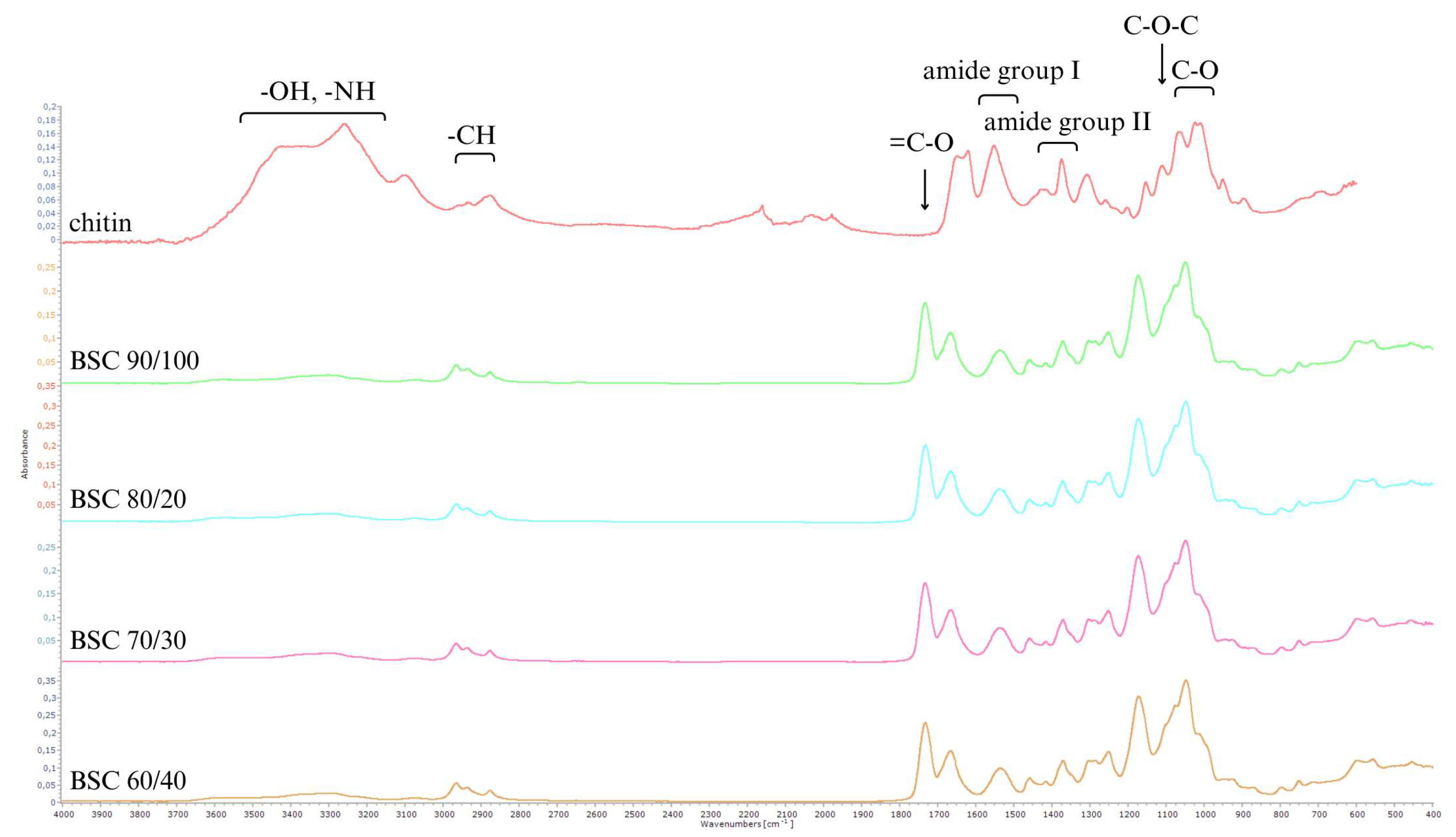

The spectrum (

Figure 2) shows significant differences between chitin and the chitin esters obtained. The spectral analysis of chitin reveals distinct signals corresponding to its functional groups, providing insights into structural modifications induced by chemical reactions. In the 4000–3000 cm⁻¹ range, bands associated with hydroxyl (-OH) and amide/amine (-NH) stretching vibrations are prominent. A reduction in the intensity of these bands in synthesised products highlights a decrease in -OH and -NH₂ groups, attributed to esterification reactions and reduced hydrogen bonding from introducing ester groups.

The 3000–2800 cm⁻¹ region corresponds to -CH stretching vibrations. Enhanced definition of these bands in the modified polymers indicates successful alkyl group incorporation from butyric and succinic anhydrides. Additionally, amide group signals in chitin, including a strong band at 1656 cm⁻¹ (amide I) and another at 1554 cm⁻¹ (amide II), partially diminish in synthesised products, evidencing amide group modification and confirming structural alteration in the resulting copolyesters (

Figure 3).

The 1200–900 cm⁻¹ region, associated with the glycosidic ring, shows minimal spectral changes. Vibrations linked to glycosidic oxygen bridges (C-O-C) at 1150 cm⁻¹ and C-O vibrations at 1030–1100 cm⁻¹ remain intact, indicating retention of the glycosidic ring's structure post-synthesis. Overlapping signals in this range, including new ester bond bands at 1100–1000 cm⁻¹, confirm the integration of ester groups while preserving the fundamental chitin structure.

Notably, the spectra of the synthesised products exhibit new intense bands at 1740–1730 cm⁻¹, corresponding to carbonyl groups (C=O) characteristic of esters. This observation validates the efficiency of esterification using butyric and succinic anhydrides, demonstrating successful chemical modification of chitin into functionalised copolyesters.

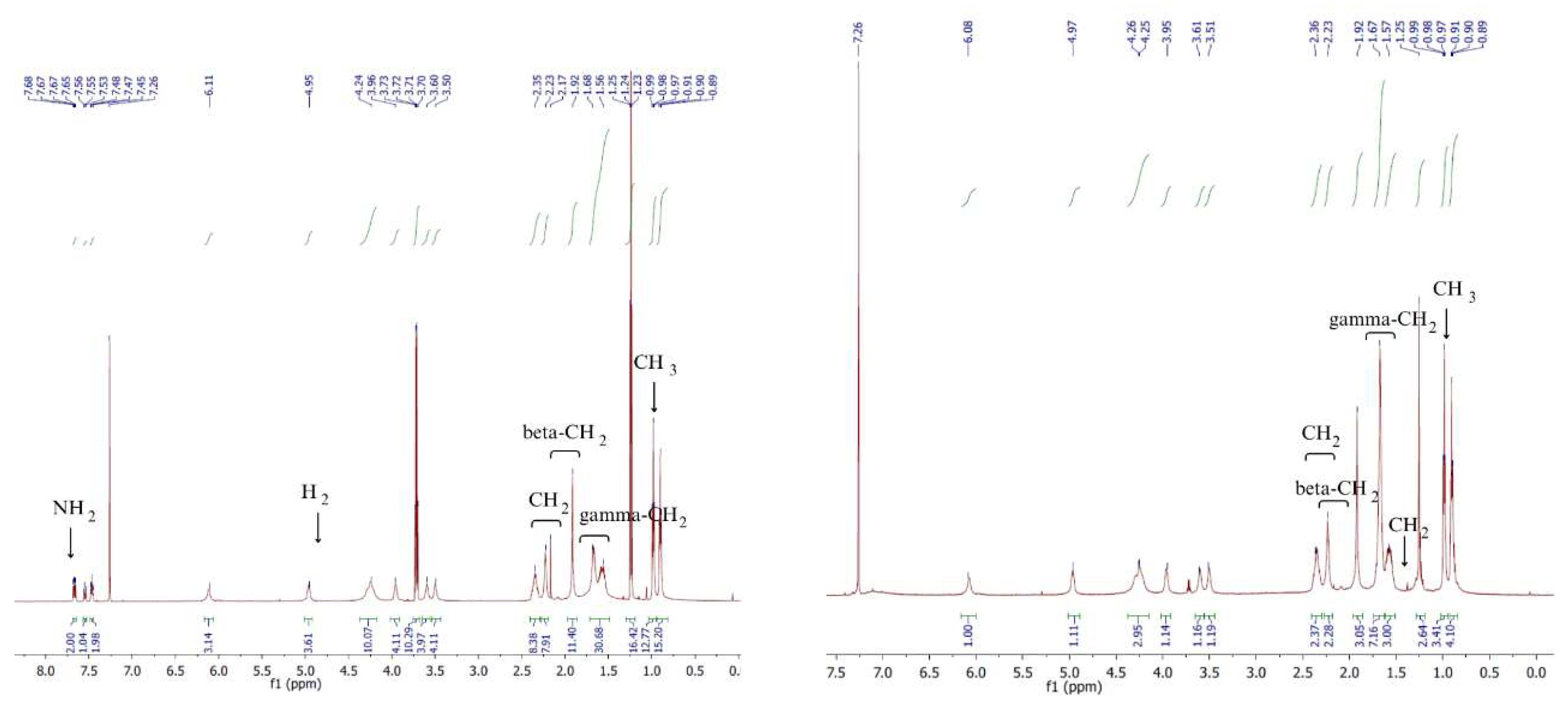

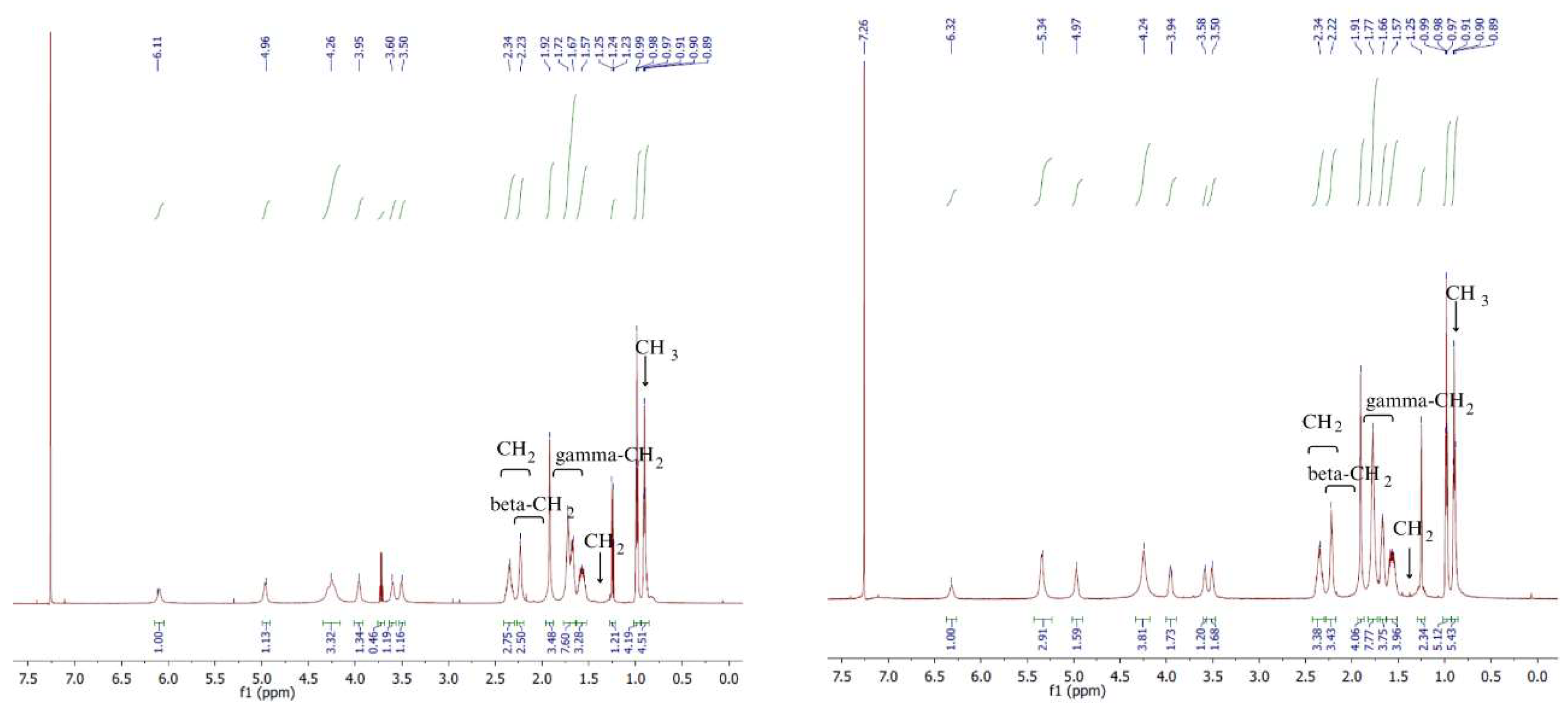

Besides FTIR ATR analysis, the obtained chitin esters were analysed by NMR. In the

1H NMR spectra (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) shown, the following proton signals can be identified:

NH2 in chitin at 7.8 ppm

CH2 group of succinic acid at 2.2-2.4 ppm

Beta-CH2 group of butyric acid at 2.3–2.1 ppm

Gamma-CH2 group of butyric acid 1.7–1.6 ppm

CH2 group on C6 atom of sugar ring 1.47 ppm

CH3 group of butyric acid 0.9 ppm 0.84 ppm

Based on

1H NMR analysis, it is possible to determine the degree of substitution with butyryl and succinyl groups (

Table 2). The degree of substitution (DS) for BSC 90/10 copolymer was 1.8 for groups derived from butyric acid anhydride, corresponding to the theoretical maximum DS. Similarly, for groups derived from succinic acid anhydride, the DS calculated from ¹H NMR spectra was 0.2, aligning with the theoretical expectation.

In the BSC 80/20 copolymer, the DS with butyric acid anhydride groups reached the theoretical maximum of 1.6. The substitution level for succinic acid anhydride groups also matched the theoretical value, confirming consistent reactivity.

However, in BSC 70/30 and 60/40 copolymers, deviations were observed. For BSC 70/30, the DS for butyric acid anhydride groups was 1.2, lower than the theoretical value of 1.4, while the DS for succinic acid anhydride groups was 0.8, exceeding the theoretical value of 0.6. These variations are attributed to steric hindrance, where the larger succinic acid anhydride groups restrict access to reactive sites for the smaller butyric acid groups.

The higher theoretical substitution of succinic acid anhydride groups is linked to its symmetrical structure and higher reactivity, facilitating nucleophilic attack. Additionally, the four-membered ring structure of succinic acid anhydride generates ring strain, making its bonds more prone to cleavage during reactions. On the other hand, the lack of ring strain in butyric acid anhydride results in its lower reactivity.

The thermal decomposition of the samples begins at approximately 50°C, with the most significant weight loss occurring between 80.0–83.5°C and concluding between 96.7°C and 103.1°C, varying by sample (

Table 3). This initial weight loss, ranging from 3.1–3.5%, is attributed to the evaporation of water and residual solvents.

The primary thermal degradation phase commences at significantly higher temperatures, between 289.7°C and 291.1°C. The temperature at which the most substantial weight loss occurs is recorded between 314°C and 322.6°C, with the degradation process concluding at a peak temperature of 340°C to 351.4°C. A distinctive mass loss of 81.1–83.8% is observed during this stage, signalling extensive material decomposition. Stawski et al. [

40] demonstrated that the thermal degradation range of chitin varies between 300°C and 460°C, depending on its source. The degradation temperatures of the synthesised copolyesters align with this range, which suggests that the modifications made during synthesis did not significantly alter the thermal stability of the obtained derivative.

The highest water contact angle was observed for the film derived from BSC 90/10, indicating its pronounced hydrophobicity relative to other samples (

Table 4). This is attributed to its higher content of butyryl groups, which consist of short, aliphatic chains exhibiting hydrophobic characteristics. The film obtained from synthesis product 2b exhibited a slightly reduced contact angle, likely due to the increased content of succinic groups within the polymer matrix. Succinic acid anhydride-derived groups contain carbonyl and hydroxyl functionalities, imparting a mild hydrophilic character. The film synthesised from BSC 70/30 demonstrated a more hydrophilic nature than those from BSC 90/10 and BSC 80/20, reflecting a higher content of succinic groups in its structure. The lowest contact angle was measured for the sample derived from BSC 60/40, indicating the highest hydrophilicity among the tested materials. Such changes emphasise the direct relationship between the proportion of succinic groups in the polymer and the increasing hydrophilicity of the film.

4. Discussion

This study synthesised a novel chitin derivative, butyric-succinic chitin, using methanesulfonic acid as a catalyst. Structural analysis through FTIR ATR confirmed significant modifications in the chemical structure of the synthesised copolyesters, evidenced by the weakening of hydroxyl and amine bands (3600–3000 cm⁻¹) and the emergence of bands corresponding to alkyl (3000–2800 cm⁻¹) and carbonyl (1740–1730 cm⁻¹) groups. Specifically, preserving the characteristic glycosidic ring demonstrated that the basic structure of chitin remained intact after esterification.

The degree of substitution of butyric and succinyl groups was determined by ¹H NMR spectroscopy, and it aligned closely with theoretical values for most samples. The hydrophilicity of the copolyesters was shown to increase with succinic anhydride content due to the presence of polar groups. Furthermore, incorporating butyryl and succinyl groups into the structure of the polymer provides the possibility for further chemical modifications. These modifications may enable the addition of bioactive or reactive active substances, opening the way to developing novel biomaterials with customisable properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.B.; methodology, A.B..; validation, A.B. and N.T.; formal analysis, A.B. and N.T.; investigation, A.B., N.T and M.P. (synthesis); writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and N.T.; writing—review and editing, A.B., N.T. and E. P.-W.; visualisation, A.B. and N.T..; supervision, E. P.-W. G.S. and Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the statutory research fund of the Institute of Textile Engineering, Lodz University of Technology, Żeromskiego str. 116, 90-924 Lodz, Poland, assigned no. I-42/501/4-42-1-3.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Piotr Cichacz and Patryk Śniarowski.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sánchez-Vallet, A.; Mesters, J.R.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. The Battle for Chitin Recognition in Plant-Microbe Interactions. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2015, 39, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.J.; Fernandez, J.G.; Sohn, J.J.; Amemiya, C.T. Chitin Is Endogenously Produced in Vertebrates. Current Biology 2015, 25, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, N.D.; Brück, W.M.; Garbe, D.; Brück, T.B. Enzymatic Modification of Native Chitin and Conversion to Specialty Chemical Products. Mar Drugs 2020, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crini, G. Historical Review on Chitin and Chitosan Biopolymers. Environ Chem Lett 2019, 17, 1623–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Dhillon, G.S. Recent Trends in Biological Extraction of Chitin from Marine Shell Wastes: A Review. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2015, 35, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, V.; Asghari, M.; Dashti, A. A Review on Chitin and Chitosan Polymers: Structure, Chemistry, Solubility, Derivatives, and Applications. ChemBioEng Reviews 2015, 2, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Yadav, P.N.; Adhikari, R. Applications of Chitin and Chitosan in Industry and Medical Science: A Review. Nepal J Sci Technol 2016, 16, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Komi, D.E.; Sharma, L.; Dela Cruz, C.S. Chitin and Its Effects on Inflammatory and Immune Responses. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018, 54, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, A.; Mudasir, A.; Saiqa, I. Advanced Materials Chitosan : A Natural Antimicrobial Agent : A Review. Journal of Applicable Chemistry 2014, 2, 493–503. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, B.; Huang, Y.; Lu, A.; Zhang, L. Recent Advances in Chitin Based Materials Constructed via Physical Methods. Prog Polym Sci 2018, 82, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Ganesan, A.R.; Muralisankar, T.; Jayakumar, R.; Sathishkumar, P.; Uthayakumar, V.; Chandirasekar, R.; Revathi, N. Recent Insights into the Extraction, Characterisation, and Bioactivities of Chitin and Chitosan from Insects. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020, 105, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusztahelyi, T. Chitin and Chitin-Related Compounds in Plant–Fungal Interactions. Mycology 2018, 9, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, K.; Izumi, R.; Osaki, T.; Ifuku, S.; Morimoto, M.; Saimoto, H.; Minami, S.; Okamoto, Y. Chitin, Chitosan, and Its Derivatives for Wound Healing: Old and New Materials. J Funct Biomater 2018, 9, 104–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadidio, C.; Peregrina, D.V.; Gigliobianco, M.R.; Deng, S.; Censi, R.; Di Martino, P. Chitin and Chitosans: Characteristics, Eco-Friendly Processes, and Applications in Cosmetic Science. Mar Drugs 2019, 17, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamshina, J.L.; Berton, P.; Rogers, R.D. Advances in Functional Chitin Materials: A Review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2019, 7, 6444–6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Knidri, H.; Belaabed, R.; Addaou, A.; Laajeb, A.; Lahsini, A. Extraction, Chemical Modification and Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 120, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, I.; Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan Preparation from Marine Sources. Structure, Properties and Applications. Mar Drugs 2015, 13, 1133–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varlamov, V.P.; Il’ina, A.V.; Shagdarova, B.T.; Lunkov, A.P.; Mysyakina, I.S. Chitin/Chitosan and Its Derivatives: Fundamental Problems and Practical Approaches. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2020, 85, 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, L.R.; Kim, B.M.; Hyun, K.; Kwak, G.B.; Lee, C.H.; Chai, K.Y. Preparation and Characterisation of Chitin Benzoic Acid Esters. Molecules 2011, 16, 3029–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoll-Romero, L.; Pascual, S.; Aragunde, H.; Biarnés, X.; Planas, A. Chitin Deacetylases: Structures, Specificities, and Biotech Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifuku, S. Chitin and Chitosan Nanofibers: Preparation and Chemical Modifications. Molecules 2014, 19, 18367–18380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivashankari, P.R.; Prabaharan, M. Deacetylation Modification Techniques of Chitin and Chitosan; Elsevier, 2017; Vol. 1; ISBN 9780081002575.

- Latańska, I.; Kolesińska, B.; Draczyński, Z.; Sujka, W. The Use of Chitin and Chitosan in Manufacturing Dressing Materials. Prog Chem Appl Chitin Deriv 2020, 25, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklagina, Y.G.; Klechkovskaya, V.V.; Kononova, S.V.; Petrova, V.A.; Poshina, D.N.; Orekhov, A.S.; Skorik, Y.A. Polymorphic Modifications of Chitosan. Crystallography Reports 2018, 63, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.B.; Struszczyk-Swita, K.; Li, X.; Szczęsna-Antczak, M.; Daroch, M. Enzymatic Modifications of Chitin, Chitosan, and Chitooligosaccharides. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Fang, Z.; Tian, W.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cai, J. Green Fabrication of Amphiphilic Quaternized β-Chitin Derivatives with Excellent Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Activities for Wound Healing. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, N.; Noguchi, J.; Tokura, S.; Shiota, H. Studies on Chitin X. Cyanoethylation of Chitin. Polym J 1983, 15, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaifu, K.; Nishi, N.; Komai, T.; Seiichi, S.; Somorin, O. Studies on Chitin. V. Formylation, Propionylation, and Butyrylation of Chitin. Polym J 1981, 13, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, E.J.; Stacey, M.; Tatlow, J.C.; Tedder, J.M. Studies on Triflluoroacetic Acid. Part I. J Chem Soc 1949, 2976–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, J.E.; Tatlow, C.E.M.; Tatlow, J.C. Studies Od Trifluoroacetic Acid. Part II. J Chem Soc 1950, 1367–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, E.J.; Stacey, M.; Tatlow, J.C.; Tedder, J.M. Studies Od Trifluoroacetic Acid. Part III. J Chem Soc 1949, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, E.J.; Henry, S.H.; Tatlow, C.E.M.; Tatlow, J.C. Studies Od Trifluoroacetic Acid. Part IV. J Chem Soc 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Luyen, D.; Rossbach, V. Mixed Esters of Chitin. J Appl Polym Sci 1995, 55, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.Y.; Ding, Q.; Montgomery, R. Preparation and Physical Properties of Chitin Fatty Acids Esters. Carbohydr Res 2009, 344, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draczynski, Z.; Bogun, M.; Sujka, W.; Kolesinska, B. An Industrial-Scale Synthesis of Biodegradable Soluble in Organic Solvents Butyric–Acetic Chitin Copolyesters. Advances in Polymer Technology 2018, 37, 3210–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draczyński, Z. Synthesis and Solubility Properties of Chitin Acetate/ Butyrate Copolymers. J Appl Polym Sci 2011, 122, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, L.R.; Kim, B.M.; Hyun, K.; Kang, K.H.; Lu, C.; Chai, K.Y. Preparation of Chitin Butyrate by Using Phosphoryl Mixed Anhydride System. Carbohydr Res 2011, 346, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draczyński, Z. Kopoliester Butyrylo-Acetylowy Chityny Jako Nowy Aktywny Składnik Nanokompozytów Polimerowo-Włóknistych; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaszuba, M.; Corbett, J.; Watson, F.M.N.; Jones, A. High-Concentration Zeta Potential Measurements Using Light-Scattering Techniques. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2010, 368, 4439–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawski, D.; Rabiej, S.; Herczyńska, L.; Draczyński, Z. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Chitins of Different Origin. J Therm Anal Calorim 2008, 93, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).