Introduction

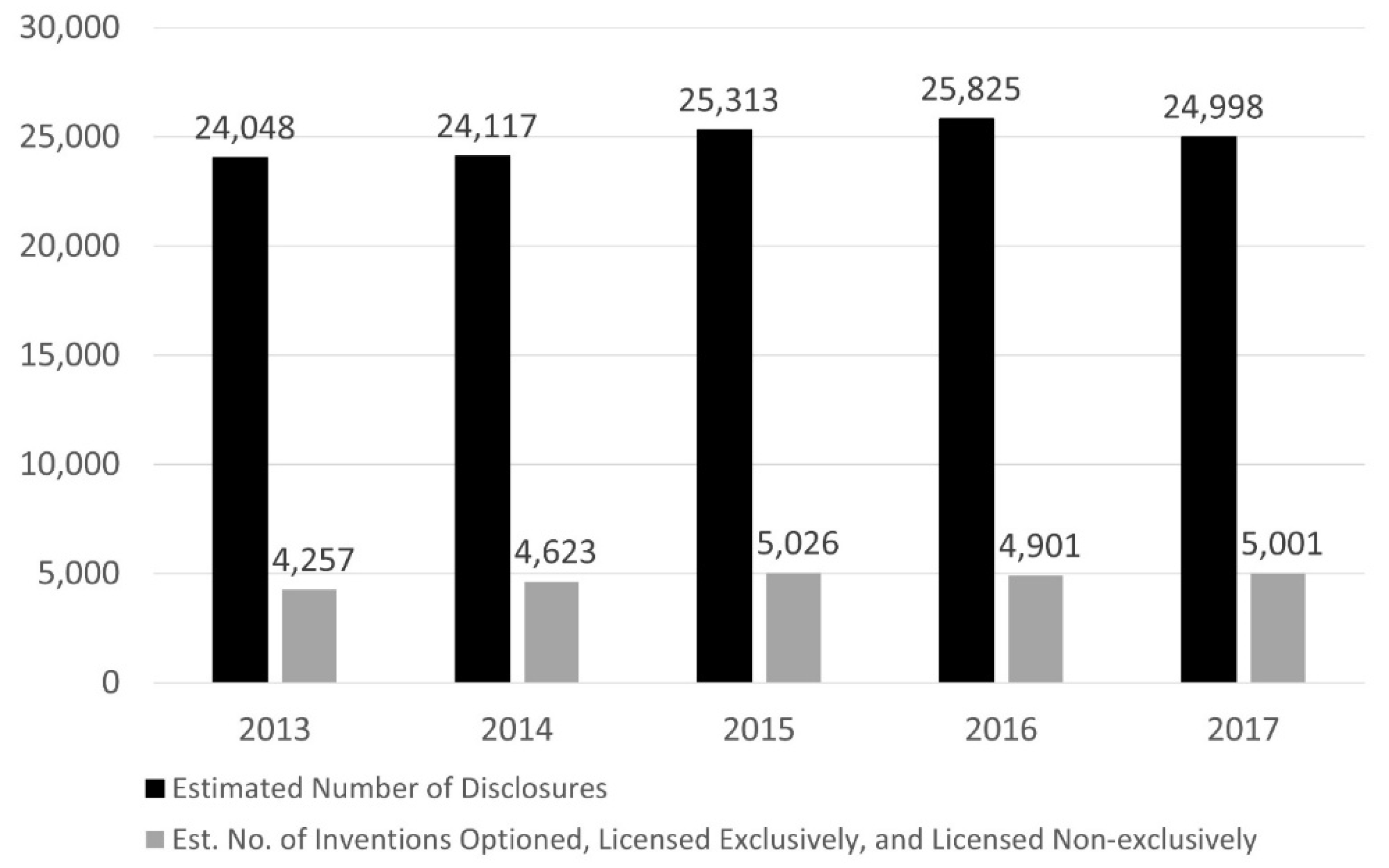

The incidence of university and federal laboratory technology transfer in the United States of America (U.S.) has increased significantly since the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, but progress seems to have stalled based on an examination of data about licensing rates over the years. Technology, in this context, is broadly defined as culturally influenced information that social actors use to pursue the objectives of their motivations, and which is embodied in such a manner to enable, hinder, or otherwise control its access and use (Townes, 2022). Prior to the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, only about five (5) percent of patented technologies derived from federally funded research were licensed (Schacht, 2012). However, not all technologies are patentable, so it is reasonable to conclude that the percentage of technologies created that were licensed was likely lower. Currently, about 20 percent of technologies (mostly patented inventions) created at U.S. universities, many with the support of federal funding, are licensed (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2020; Townes, 2022; see

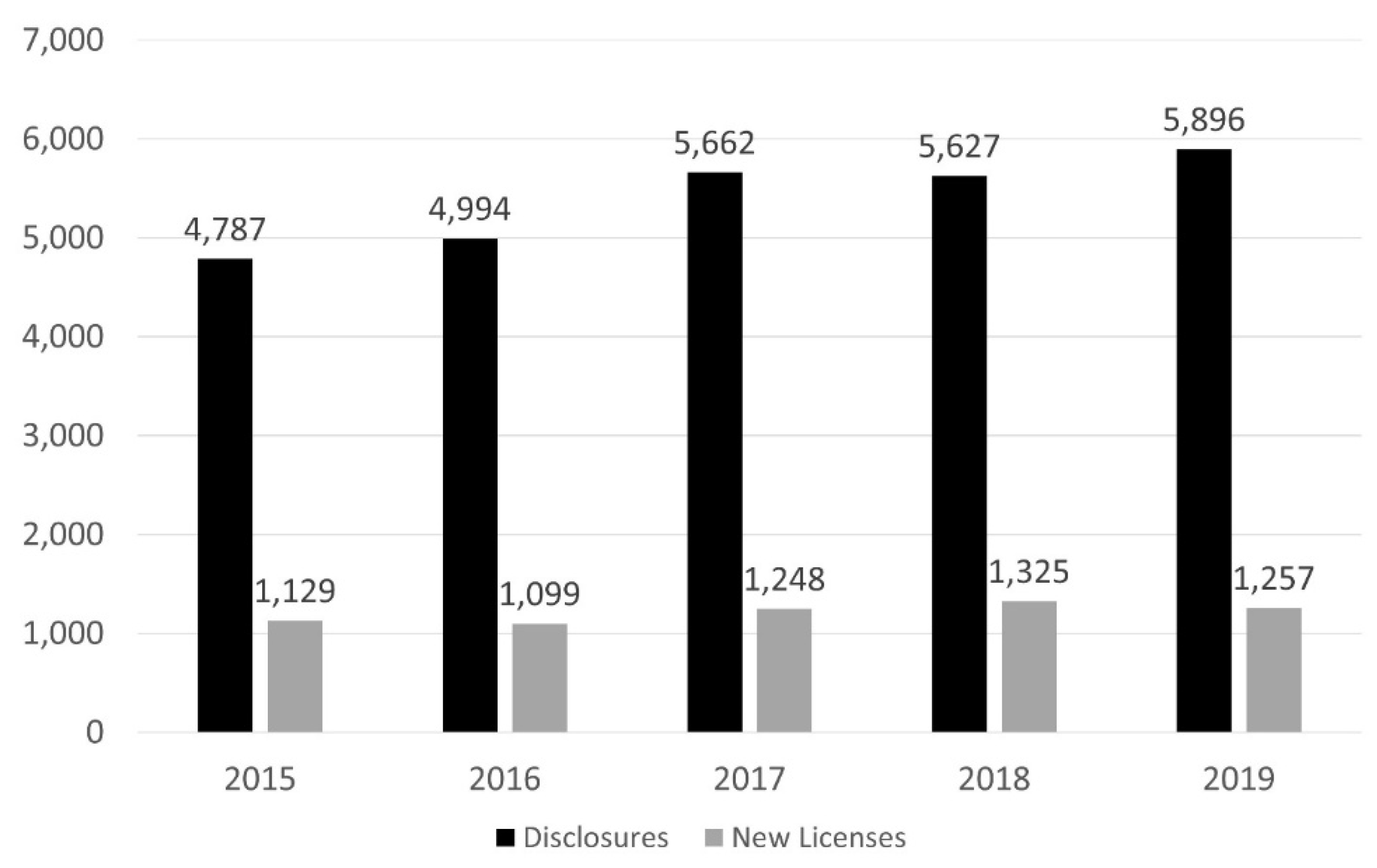

Figure 1). The licensing percentage for patented technologies created at federal laboratories is about the same as that for universities (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2022; see

Figure 2). However, it must be noted that the data are not based on a one-to-one match of technology disclosures with technology licenses and options. Technologies licensed and optioned in a given year are likely to have been disclosed in prior years.

Research suggests that technology maturity level is an important factor that influences the incidence of technology transfer (see Munteanu, 2012; Townes, 2022, 2024a). University administrators and federal policymakers have either taken or considered actions related to technology maturity level to increase the incidence of technology transfer. Several universities have launched what are typically referred to as “gap funds” to de-risk and mature technologies to attract industry commercialization partners (Munari et al., 2016; Price & Sobocinski, 2002). The U.S. Congress has also considered intervention to increase the incidence of technology transfer. In the 117th Congress, Senate bill S.1260 and House bill H.R.2225 were introduced. If the legislation had been enacted it would have authorized funding for universities to enable technology maturation.

The gap fund programs of U.S. universities and proposed public policy initiatives such as S.1260 and H.R.2225 underscore a measurement issue. How does one measure the maturity of a technology at the meso- and micro-level in a practical and useful way? Various approaches for measuring technology maturity have been proposed in the literature (see e.g., Kyriakidou et al., 2013; Lezama-Nicolás et al., 2018; Mankins, 1995, 2009a, 2009b; Zorrilla et al., 2022). However, most of these approaches are intended for very specific contexts. Others are too complex and cumbersome to be of practical use to technology transfer practitioners in universities. Moreover, none of these instruments, except for a few, have been validated in any meaningful way.

Perhaps the most well-known instrument used to characterize the maturity level of a technology is the technology readiness level (TRL) scale developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in the United States of America. Some university technology transfer offices have begun applying this scale in various manners as part of their processes for vetting technologies and making portfolio decisions. However, many university technology transfer professionals have encountered challenges using the NASA TRL scale (see e.g., Li et al., 2023; Townes, 2024b). These challenges not only make it difficult for university technology transfer practitioners to effectively employ the scale as tool for managing technology portfolios and facilitating the conveyance of technologies created at universities to the private sector, but they also make it nearly impossible to confidently generalize research findings or perform meta-analyses on studies of technology maturity level and its influence on technology transfer (see e.g., Olechowski et al., 2020; Schwartz, 2023; Townes, 2024b).

It is not surprising that technology transfer practitioners operating in certain contexts encounter difficulties when applying the NASA TRL scale. The scale is essentially a typology framework. Putting typologies into practice can be challenging (see Collier et al., 2012). Also, as an agency of the federal government, NASA developed the TRL scale in the context of public sector applications. The public sector is not motivated by economic profit in the same way as the private sector. Moreover, technology development projects at universities and in the private sector are also likely to comprise a much broader range of types and kinds of technologies than those in any given federal agency in the public sector. Finally, there is no indication that anyone has ever established the validity and reliability of the NASA TRL scale. Consequently, developing and validating a generalized TRL scale would constitute a significant contribution to the literature and could prove very useful in facilitating and advancing technology transfer research, policy, and practice.

Instruments and special apparatus capable of accurately and reliably measuring phenomena are essential for scientific advancement (see Kuhn, 2012). Also, practitioners and policy makers cannot effectively determine whether or to what degree gap fund mechanisms and other interventions focused on maturing technologies affect the incidence of technology transfer without a valid and reliable measurement instrument. The NASA TRL scale as it is currently formulated is not particularly well-suited to fulfill this role.

The aim of this paper is to present research that contributes to the knowledge base relevant to the assessment and evaluation of research and technology, particularly in academic settings. This includes key insights about methodologies and methods to properly validate instruments for measuring the maturity of technologies. The study presented in this paper examined three issues. First, how can the NASA TRL scale be adapted to better suit the needs of technology transfer professionals in a wider range of contexts, particularly university technology transfer practitioners? Second, how applicable to validating such an instrument based on “readiness levels” are the typical methods for assessing the validity of measurement instruments? Finally, how should large scale studies be structured to better ensure the proper validation of technology maturity measurement instruments that are based on “readiness levels” and intended for use at universities and in other contexts?

Review of the Related Literature

The literature relevant to the topic of assessing technology maturity level is very limited. The construct of technology maturity level itself is difficult to define. Most of the reviewed literature about technology maturity level fails to explicitly define the construct (see e.g., Albert, 2016; Bhattacharya et al., 2022; Chukhray et al., 2019; Juan et al., 2010; Mankins, 1995, 2009a; Munteanu, 2012). Nolte (2008) resorted to analogies and scenarios to try to explain technology maturity level but never provided an exact definition. Based on what is discussed in the literature, it seems reasonable to broadly define technology maturity level as the degree to which a technology is ready for use as intended.

The NASA TRL scale is probably among the earliest attempts to operationalize technology maturity level and is one of several approaches found in the literature. The need for explicitly defined descriptions of various steps of progression for demonstrating flight readiness became apparent as satisfying the technical needs of NASA programs progressed beyond exploiting existing technology assets by adapting and requalifying them to pursuing new technologies (see Sadin et al., 1989). Stanley Sadin, a NASA researcher, is credited with conceiving and formulating the first 7-level TRL scale in 1974 to address this issue (Banke, 2010). In 1995, John Mankins, another NASA researcher and program manager, extended and further refined the TRL scale to its current 9-level incarnation (Mankins, 2009b). Since then, other scholars and practitioners have proposed alternative readiness level scales to assess the maturity of technologies in various contexts or have adapted the concept of readiness levels to other domains (see

Table 1). In fact, so many alternatives and variants of readiness level scales have been offered, introduced, or adapted for various settings that “readiness level proliferation” has become a problem in the public sector (Nolte & Kruse). However, few, if any, of these scales appear to have been validated in any scientifically meaningful way.

Use of the NASA TRL scale as a measure of the maturity of a technology seems to have gained traction in the fields of research management and technology transfer, particularly within U.S. universities. This is probably because of its adoption by certain departments and agencies of the U.S. government that fund a significant amount of research conducted at U.S. universities. In 2001, after the General Accounting Office (GAO) recommended that the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) make use of the scale in its programs, the Deputy Under Secretary of Science and Technology issued a memorandum endorsing the use of the TRL scale in new DoD programs. Guidance for using the scale to assess the maturity of technologies was incorporated into the Defense Acquisition Guidebook and detailed in the 2003 DoD Technology Readiness Assessment Deskbook (Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Science and Technology, 2003; Nolte & Kruse, 2011, October 26; Nolte, 2008). In the mid-2000s, the European Space Agency (ESA) adopted a TRL scale that closely followed the NASA TRL scale (European Association of Research and Technology Organizations, 2014). The NASA TRL scale has apparently become the de facto standard for measurement instruments to assess the maturity of technologies across a variety of industries (Olechowski et al., 2015).

But just because an instrument has become widely adopted does not mean it is optimal for the task or meets the needs of all users in all contexts. The NASA TRL scale is not without its shortcomings. Many, if not most, U.S. university technology transfer offices have not formally incorporated the scale into their technology evaluation processes because it is highly subjective, which makes it susceptible to idiosyncratic variation, and does not completely suit their needs (Li et al., 2023; Townes, 2024b). Olechowski et al. (2020) investigated the challenges associated with using the NASA TRL scale in practice. They found that the difficulties encountered by practitioners were related to either system complexity, planning and review, or assessment validity. The issue of assessment validity suggests that the NASA TRL scale, as constituted, may be susceptible to idiosyncratic variation, which poses a potential impediment to advancing technology transfer theory and practice.

All of this suggests that there is a significant knowledge gap regarding the measurement and application of technology maturity in technology transfer research, policy, and practice. To address this gap, an effort was undertaken to develop a generalized technology readiness level (GTRL) scale that would be practical and consistent across a wide array of settings and contexts, particularly in the field of university technology transfer. Additionally, a pilot study of the GTRL’s validity and reliability was conducted to identify and gain insights into the challenges that are likely to be encountered with validating the GTRL scale and other instruments for measuring technology maturity that are based on “readiness levels”.

Pilot studies are an important and valuable step in the process of empirical analysis, but their purpose is often misunderstood (National Institutes of Health, 2023, June 7; Van Teijlingen & Hundley, 2010). The goal of a pilot study is to ascertain the feasibility of a methodology being considered or proposed for a larger scale study; it is not intended to test the hypotheses that will be evaluated in the larger scale study (Leon et al., 2011; Van Teijlingen & Hundley). Unfortunately, pilot studies are often not reported because of publication bias that leads publishers to favor primary research over manuscripts on research methods, theory, and secondary analysis even though it is important to share lessons learned with respect to research methods to avoid duplication of effort by researchers (Van Teijlingen & Hundley).

Table 2 summarizes the study structure. The goal of this study was to fill the knowledge gap regarding the measurement of a technology’s degree of maturity by exploring the following two hypotheses:

H1: The NASA technology readiness level scale can be modified and generalized in a way that increases its practicality and minimizes idiosyncratic variation both within and across contexts.

H2: The standard approaches for validating measurement instruments can be applied to validate instruments for measuring the construct of technology maturity that are structured as readiness levels.

To examine these hypotheses, an effort was made to develop a generalized technology readiness level (GTRL) scale and investigate the following considerations about the proposed GTRL scale:

What challenges are likely to be encountered in a larger study to assess the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale and other such instruments?

Can the methods for assessing content validity be applied to the GTRL scale?

Should participants in a larger validation study of the reliability of the GTRL scale be limited to university and federal laboratory technology transfer professionals?

How difficult will it be to recruit study participants?

How should a larger study familiarize participants with the GTRL scale?

What factors should be controlled in a larger validity and reliability study?

How viable are asynchronous web-based methods for administering a validity and reliability study?

How viable is the approach of presenting marketing summaries of technologies to participants for them to rate?

How burdensome will it be for study participants to rate several technologies in multiple rounds?

What modifications, if any, to the GTRL scale should be considered before performing a larger validity and reliability study?

Data and Methods

This section describes the development of the generalized technology readiness level (GTRL) scale and the design and implementation of a pilot validity and reliability study.

Development of the Generalized TRL Scale

The NASA TRL scale was used as the starting point of reference for developing the GTRL scale because of its familiarity among technology transfer practitioners and the simplicity of its application. The NASA TRL scale is an ordinal scale. Its application as an instrument for measuring technology maturity essentially treats technology maturity as a unidimensional construct.

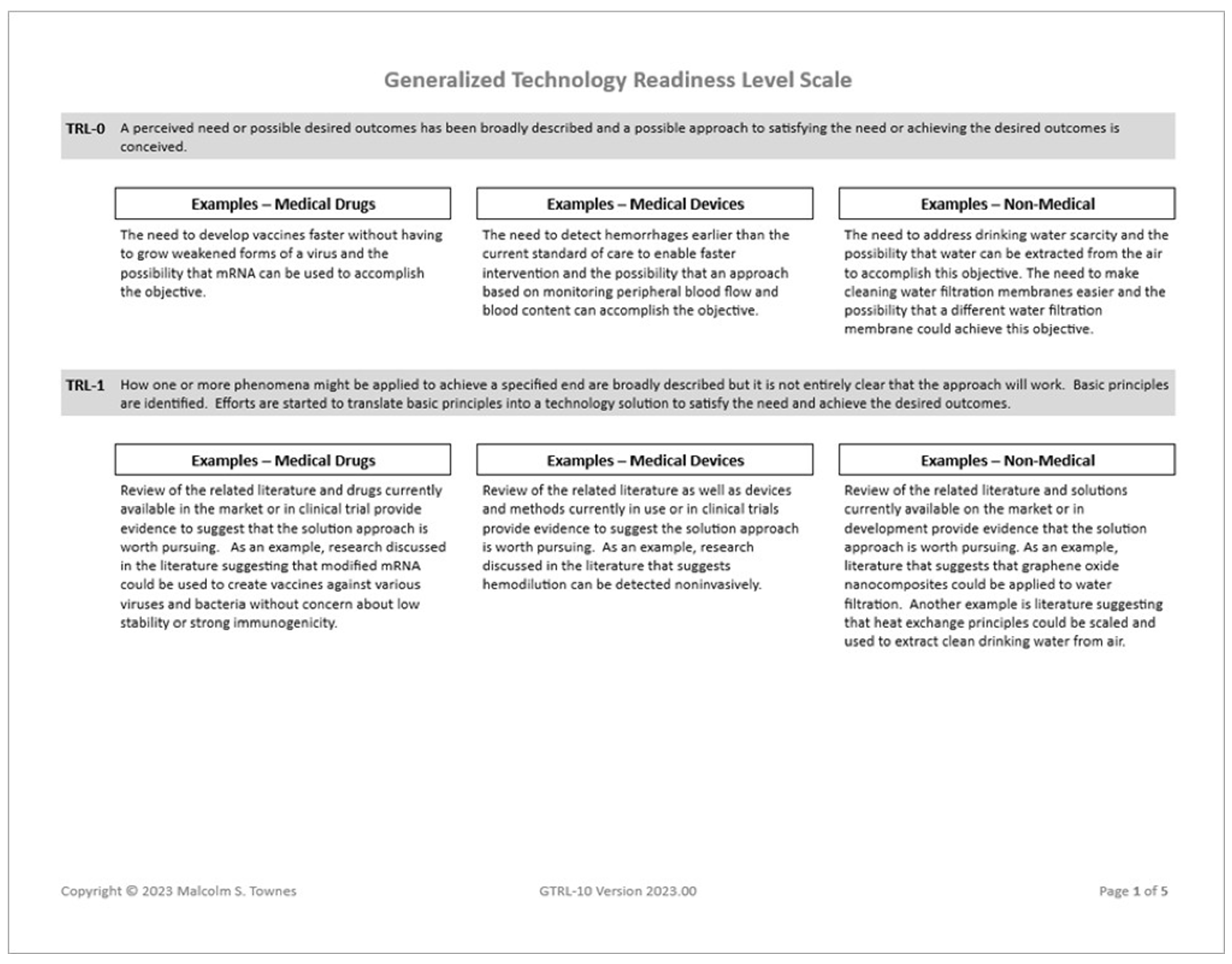

The content of various documents that discuss the NASA TRL scale and its application in other government agencies were reviewed to evaluate the comprehensiveness of the dimension indicators. Defining the indicators and sub-indicators of each readiness level was an iterative process. The objective of this step was to understand what should be included and excluded in the concept of each indicator. This was done by searching for higher order concepts (HOCs) and common themes that were adequate for characterizing each indicator regardless of the context. Generalized definitions in terms of these HOCs and common themes for each indicator of readiness were specified on the 10-level ordinal scale (see

Table 3). Examples for each of three major contexts (medical drugs, medical devices, and non-medical applications) were then developed to provide additional guidance about the meaning of each indicator (i.e., scale level) and how it should be applied.

Once the indicators and context examples were defined, the focus shifted to the content and physical layout of the GTRL scale (see

Figure 3). The layout of the original NASA TRL scale and its layout in various technology readiness assessment (TRA) deskbooks and guides were examined to identify potential issues. The objective in designing the layout of the GTRL scale was to present it in a manner that was easy to follow and intuitive to minimize the cognitive burden on the user and the possibility of user error.

With the format, layout, and content of the GTRL scale defined, attention turned to its validation. There are several types of validity that are used to establish the accuracy and reliability of an instrument for measuring a construct. Some are more relevant than others depending on the situation and context. A review of the related literature suggests that assessing face validity of the GTRL scale is unnecessary. There appears to be consensus among validity theorists that so-called face validity does not constitute scientific epistemological evidence of the accuracy of an instrument or its indicators (Royal, 2016).

Assessing Content Validity

Content validity is an indication of whether the construct elements (i.e., dimensions) and element items (i.e., indicators) of a measurement instrument are sufficiently comprehensive and representative of the operational definition of the construct it purports to measure (see Almanasreh et al., 2019; Bland & Altman, 2002; Yaghmaie, 2003). Content validity is considered a prerequisite for other types of validity (Almanasreh et al.; Yaghmaie). For the GTRL scale, “technology readiness” is the only construct element. Each readiness level (i.e., TRL) is an indicator of the degree of “technology readiness” on the scale.

There is no universally agreed upon approach or statistical method for examining content validity (Almanasreh et al., 2019). The content validity index (CVI), proposed by Lawshe (1975), was chosen as the statistic for examining the content validity of the GTRL scale because it is a widely used approach. Although there is the possibility that the CVI may overestimate content validity due to chance, it has the advantage of being simple to calculate as well as easy to understand and interpret.

Some modifications were made to the CVI method. For purposes of evaluating the indicators, “relevance” was replaced with the concept of “usefulness” because theoretically an indicator can be relevant to a construct without necessarily being useful in a practical sense for measuring the concept. For evaluating the context examples for each indicator, “relevance” was replaced with the concept of “helpfulness” for much the same reason because an example can be relevant without being helpful to understanding how to interpret and apply an indicator. Moreover, the term “helpful” better reflects the intended function of the examples.

Two (2) individuals with experience in university technology transfer were recruited to serve as experts to assess the content validity of the GTRL scale. Each expert had more than 15 years of experience in university technology transfer and served as director of a university technology transfer office. No compensation was offered for participating in the study. An email that contained a copy of the GTRL scale and a link to an online questionnaire (created on the Qualtrics platform) was sent to the experts to collect the content validation data (see Supplementary Resource 1). The email instructed them to familiarize themselves with the GTRL scale before completing the questionnaire. The experts did not have to complete the questionnaire in one session. They could save their answers and return to complete the questionnaire later. However, if they did not continue or complete the questionnaire within two (2) weeks after the last time they worked on it, whatever answers they provided up to that point were recorded.

The overall process for assessing the content validity of the GTRL scale consisted of having an expert first rate the clarity of each indicator (i.e., readiness level) definition beginning with the lowest indicator followed by the next sequential indicator until the expert had rated every readiness level definition. Then the expert rated the clarity of each context example for each readiness level, beginning with the lowest followed by the next sequential readiness level until the expert rated all context examples for every readiness level. After rating clarity, the experts then rated the helpfulness of each context example as an aid to understanding how to assess whether a technology satisfied the requirements for a given readiness level beginning with the lowest followed by the next sequential readiness level until the expert had rated all context examples for every readiness level. The experts then rated the usefulness of each readiness level as a measure of the maturity of a technology, beginning with the lowest followed by the next sequential readiness level until the expert had rated every readiness level. Finally, the experts rated the usefulness of the concept of “technology readiness” as a measure of technology maturity.

This sequencing was adopted so that the experts would not have to keep changing their focus from one concept or feature to another. There was a concern that such focus shifting would affect how consistently the experts rated the scale features. Assessment of the element itself was done last because there was a concern that an expert’s response to this question would act to unduly prime the expert’s ratings of all other features of the scale.

The specifics of the content validity assessment began by showing the expert a matrix table with the definitions of the readiness levels listed in sequential order from lowest to highest and asking the expert to rate the clarity of the definition of each on the following Likert scale:

1 – not clear at all

2 – needs some clarification

3 – clearly understood

Next, the questionnaire presented the expert with a matrix table consisting of examples for each context for the lowest readiness level and instructed the expert to rate the clarity of each context example on the same Likert scale shown above. This process was repeated for each readiness level in sequential order until the experts had rated all context examples for all readiness levels.

After rating the clarity of each readiness level and its contexts example, the experts rated the helpfulness of each context example for each readiness level. Beginning with the lowest readiness level, the questionnaire presented the experts with a matrix table comprising examples for each context and asked them to rate the helpfulness of each on the following Likert scale:

1 – not helpful at all

2 – marginally helpful

3 – helpful

This process was repeated for each readiness level in sequential order until the experts had rated the context examples of every readiness level.

The experts then rated the usefulness of each readiness level, as defined, as a measure of technology readiness. The questionnaire presented the experts with a matrix table that showed the definitions of each readiness level listed in sequential order from lowest to highest and asked them to rate the usefulness of each readiness level on the following Likert scale:

1 – not useful at all

2 – marginally useful

3 – useful

Once the experts rated the clarity and usefulness of each readiness level and the clarity and helpfulness of each context example for each readiness level, the questionnaire asked them to rate the usefulness of the concept of “technology readiness” as a measure of technology maturity level using the same Likert scale used for rating the usefulness of the readiness levels above.

Assessing Inter-Rater and Intra-Rater Reliability

The method for determining the inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of the GTRL scale relied on both professional and lay experts rating several technology summaries. Ten technologies at various stages of development were selected from public sources. Using this information, a 1-to-2-page summary was created for each technology similar in style to technology summaries posted by many university technology transfer offices (see Supplementary Resource 2). To ensure that a variety of maturity levels were represented, the information was modified in some cases to describe the technology as having achieved a greater or lesser degree of maturity. A questionnaire was then created using Qualtrics to present the technology summaries and collect responses from raters (see Supplementary Resource 3).

A combination of non-probabilistic purposive sampling and non-probabilistic convenience was used to recruit respondents. Potential respondents who were likely to be familiar with evaluating technology and readily accessible were selected. These sampling approaches are considered suitable for preliminary research (see Etikan et al., 2016; Jager et al., 2017; Sedgwick, 2013). Respondents were solicited via an email recruitment message sent using the Qualtrics platform to a total of 22 additional individuals who had experience assessing the maturity of technologies. No compensation was offered to them for participating in the study. The recruitment message informed the prospective raters that they would be rating 10 technologies and that at least two (2) weeks later they would be asked to rate the same 10 technologies again without referring to their previous ratings. A reminder message was sent five (5) calendar days after the original recruitment email message.

The prospective respondents were given 14 calendar days from the date of the initial recruitment email message to complete the questionnaire at which time the survey closed. Roughly 14 calendar days after the first survey closed, an email recruitment message for the second survey was sent via the Qualtrics platform to those individuals who responded to the first survey. A reminder message was sent seven (7) calendar days after the first follow up recruitment email message. The second questionnaire was essentially structured the same as the first questionnaire except that the respondents were allowed to skip the overview of the GTRL scale if they chose to do so (see Supplementary Resource 4).

Once the data were collected, the CVratio function in the psychometric package (Fletcher, 2023) of the open-source programming language R in the RStudio developer environment was used to calculate the content validity ratios (CVRs) for each technology readiness level and context example (see Supplementary Resource 5). The ICC function for intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) in the psych package (Revelle, 2024) as well as the icc and kripp.alpha functions in the irr package (Gamer et al., 2019) were used to calculate the inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of using the GTRL scale (see Supplementary Resource 5).

Results

This section briefly presents the results of piloting the data collection methodology described above as well as the proposed methods for analyzing data collected in a larger study to assess the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale.

Content Validity

Each expert rated the scale level definitions and context examples of the GTRL scale (see

Table 4).

The scale level content validity index (CVI) was calculated as 0.8 using the CVRs for the usefulness of the technology readiness level definitions (see

Table 5).

Inter-Rater and Intra-Rater Reliability

Of the 22 other individuals invited to participate in the pilot study, only four (4) individuals rated one (1) or more technologies. Three (3) of those individuals rated all 10 technologies, and one (1) person only rated four (4) of the technologies. Of the four (4) individuals who rated one (1) or more technologies, three (3) of them rated all 10 technologies a second time.

The data were downloaded into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, organized, and cleaned (see

Table 6). The ICC and Krippendorff’s Alpha were calculated for the inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of using the GTRL scale were calculated (see

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9, and

Table 10). For the ICC calculations, the two-way mixed-effects model was selected because each technology was rated by the same set of raters. However, the raters were not randomly selected from a larger population of raters with similar characteristics. The single rater type was selected because the GTRL scale is intended to use the measurement from a single rater as the basis of assessment. Finally, the absolute agreement definition was chosen because the analysis focused on whether different raters assign the same score to the same subject. Additionally, the two-way mixed-effects single rater consistency ICC model was also included because it is identical to a weighted Cohen’s kappa coefficient with quadratic weights for ordinal scales, which takes into consideration the magnitude of disagreement between raters (see Hallgren, 2012).

Discussion

The previous section presented the results of the GTRL scale development and pilot study without comment. This section aims to interpret the results presented in the previous section and answer the questions posed.

Table 11 summarizes the results of the study.

Table 11.

Summary of Study Results.

Table 11.

Summary of Study Results.

| Research Question |

Findings |

|

|

- 2.

How applicable are the typical methods for assessing the validity of measurement instruments to validating such an instrument based on “readiness levels”? |

|

- 3.

How should large scale studies be structured to better ensure the proper validation of technology maturity measurement instruments that are based on “readiness levels” and intended for use at universities and in other contexts? |

Recruit participants that are somewhat homogeneous along certain dimensions such as setting or experience assessing technologies. Participants in such studies will likely require more than just casual familiarization with the scale. Recruit between 10 and 30 participants. Email solicitation alone will probably not be sufficient |

| |

|

| Hypotheses |

Conclusion |

| H1: The NASA technology readiness level scale can be modified and generalized in a way that increases its practicality and minimizes idiosyncratic variation both within and across contexts. |

Results support hypothesis |

| H2: The standard approaches for validating measurement instruments can be applied to validate instruments for measuring the construct of technology maturity that are structured as readiness levels. |

Results support hypothesis with epistemological caveats |

Table 11.

(Continued). Summary of Study Results.

Table 11.

(Continued). Summary of Study Results.

| Considerations Investigated |

Outcomes |

|

“Technology readiness” not explicitly defined in literature There is no absolute unit of “readiness” Concept of “readiness” must be operationalized using context-specific proxies Participant recruitment is likely to be difficult CVI method is not as definitive as suggested in the literature |

- 2.

Can the methods for assessing content validity be applied to the GTRL scale? |

|

- 3.

Should participants in a larger validation study of the reliability of the GTRL scale be limited to university and federal laboratory technology transfer professionals? |

|

- 4.

How difficult will it be to recruit study participants? |

|

- 5.

How should a larger study familiarize participants with the GTRL scale? |

|

- 6.

What factors should be controlled in a larger validity and reliability study? |

|

- 7.

How viable are asynchronous web-based methods for administering a validity and reliability study? |

|

- 8.

How viable is the approach of presenting marketing summaries of technologies to participants for them to rate? |

|

- 9.

How burdensome will it be for study participants to rate several technologies in multiple rounds? |

|

- 10.

What modifications, if any, to the GTRL scale should be considered before performing a larger validity and reliability study? |

Reducing the number of readiness levels Present examples with bullet points Include higher order concept (HOC) or theme for each readiness level |

Findings

A qualitative approach augmented by quantitative methods was taken to investigate the three questions that were the focus of the study. Based on the study results, one can make the following conclusions regarding the three primary research questions.

Research Question 1: How can the NASA TRL scale be adapted to better suit the needs of technology transfer professionals in a wider range of contexts, particularly university technology transfer practitioners?

The development of the GTRL scale helped to understand how the NASA TRL scale could be adapted to better suit the needs of technology transfer practitioners in a wider range of contexts. Adapting the NASA TRL scale to create the GTRL focused on minimizing ambiguity in the definitions of each scale level and reducing the cognitive burden imposed when using the GTRL scale. This included using more precise words in the definitions, providing context-specific examples of each readiness level, using clear and simple sentence structures, minimizing the length of sentences where possible, avoiding misplaced modifiers, and using a consistent style (see Guliyeva, 2023; Johnson-Sheehan, 2015; Office of the Federal Register, 2022, March 1; Yadav et al., 2021). Chunking was also used to help reduce the cognitive burden imposed on the user (see Cowan, 2010; Thalmann et al., 2019). For example, the GTRL scale comprises three broad categories of technologies. Additionally, no more than three context-specific examples were included for each readiness level within a technology category.

Research Question 2: How applicable to validating such an instrument based on “readiness levels” are the typical methods for assessing the validity of measurement instruments?

The pilot validation study provided insight into whether the typical validation methods for assessing the validity of instruments are applicable for instruments designed to measure the degree of maturity of technologies that are based on “readiness level” scales. In short, the typical validation methods are quite applicable. However, some minor adjustments may be necessary to facilitate the application of such methods.

Research Question 3: How should large scale studies be structured to better ensure the proper validation of technology maturity measurement instruments that are based on “readiness levels” and intended for use at universities and in other contexts?

The pilot study provided numerous clues about how one should structure large scale studies of the validity and reliability of instruments designed to measure the maturity of technologies that are structured as “readiness level” scales such as the NASA TRL scale and GTRL scale. One important lesson was that such studies should recruit participants that are somewhat homogeneous along certain dimensions such as setting (e.g., university, federal laboratory, private sector research and development) or experience assessing technologies. Another is that participants in such studies will likely require more than just casual familiarization with the scale. Finally, large scale studies will likely need to recruit between 10 and 30 participants. Moreover, email solicitations alone will probably not be sufficient to successfully recruit the necessary number of participants and offering compensation will likely be necessary to minimize non-response bias.

Summary Hypotheses Conclusions

The findings above are warranted by the results of the exploration of the two hypotheses that were posed. The results of this exploration lend credence to the two hypotheses because of the specific outcomes of the examination.

Hypothesis 1: The NASA technology readiness level scale can be modified and generalized in a way that increases its practicality and minimizes idiosyncratic variation both within and across contexts.

The approach taken to modify and generalize the NASA TRL scale demonstrated by the development of the GTRL scale does appear to be a viable scheme for reducing subjectivity and mitigating potential idiosyncratic variation. The results of the pilot study suggest that such an approach holds promise but additional modifications are likely to increase the GTRL’s ease of use and further decrease idiosyncratic variation. The modifications implemented thus far do not impede the practicality of the GTRL scale. Thus, the overall usefulness of a TRL-based scale is likely increased, but this needs to be established with a larger scale validation study.

Hypothesis 2: The standard approaches for validating measurement instruments can be applied to validate instruments for measuring the construct of technology maturity that are structured as readiness levels.

It appears that the standard methods and methodologies for validating measurement instruments can be applied to validating the GTRL scale and other technology maturity measurement instruments that are based on readiness levels. The pilot study demonstrated that the most popular method for assessing content validity can be successfully applied to assessing the GTRL scale. It also demonstrated the viability of applying standard methods for assessing reliability to the GTRL scale and provided insights to guide future studies.

Summary of Considerations Investigated

The study identified and highlighted several challenges that are likely to be encountered with efforts to validate TRL-based measurement instruments for assessing the maturity of technologies. Investigating the following questions surfaced these challenges and revealed potential approaches to cope with them.

Consideration 1: What challenges are likely to be encountered in a larger study to assess the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale and other such instruments?

A significant challenge with using the construct of technology readiness level as a measure of technology maturity is that there is no formal definition. In fact, the concept of “technology readiness” does not appear to be explicitly defined in the literature. Moreover, there is no such unit or quantity of “readiness”. It can be contextually operationalized in numerous ways such as the allowable failure rate for a product or system, the efficacy of a medical drug, or the variability of properties of a material at different design phases. But such operationalizations are context-specific proxies. Strictly speaking, they are not examples of technology readiness. They simply stand in for the concept of “technology readiness”.

Another difficulty that is likely to be encountered is participant recruitment. Workloads and recent societal changes seem to make it more difficult to recruit participants for such studies. Additionally, the current environment of cyberattacks and malicious malware make many people hesitant to respond to email solicitations, which are more cost effective for large studies.

However, the most significant challenge to performing larger validation studies is epistemological in nature. The CVI method of assessing content validity may not be as definitive as the literature suggests. It assumes that experts are virtually omniscient and have near complete, infallible knowledge of the construct. This obviously cannot be true, and history is replete with examples. When using expert-based approaches it is possible for an instrument to incorporate dimensions that experts currently deem critical, which are later demonstrated to be irrelevant. It is also possible for content validity to be deemed sufficiently high even if an instrument is missing relevant and useful dimensions which the experts are simply not aware. At best, such an approach can only estimate the degree to which the content of an instrument reflects the current consensus about dimensions of a phenomena.

Consideration 2: Can the methods for assessing content validity be applied to the GTRL scale?

The pilot study demonstrated that the most popular methods for assessing content validity and reliability can be applied to the GTRL scale. The CVI value, the ICC value for inter-rater reliability, and Krippendorff’s alpha reliability coefficient were all successfully calculated and interpretable.

Consideration 3: Should participants in a larger validation study of the reliability of the GTRL scale be limited to university and federal laboratory technology transfer professionals?

It is probably worthwhile to segregate participants in larger validation studies of the GTRL scale into relatively homogenous cohorts along various dimensions. In such a scheme, one cohort would consist of university technology transfer professionals while federal laboratory technology transfer professionals would constitute another. Validation studies can also be conducted with other homogenous groups such as private sector research and development professionals in specific industries. This will likely increase the data quality and improve the internal consistency of the studies.

Consideration 4: How difficult will it be to recruit study participants?

It appears that obtaining the participation of university technology transfer professionals is likely to be a significant challenge in larger studies to assess the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale. Six (6) of the 22 other individuals (27%) solicitated for the pilot study were employed as university technology transfer professionals but none of them responded even though all were familiar with the researcher making the request. University technology transfer offices are notoriously understaffed and under-resourced. This may have contributed to the non-response rate and exacerbated societal trends that already tend to increase non-response. Several of the 22 other individuals solicitated for the study were hesitant to click on the link in the invitation email that was distributed via the online survey platform because they feared getting a computer virus even though they recognized the name of the person making the request.

Consideration 5: How should a larger study familiarize participants with the GTRL scale?

Although this was only a pilot study, one interpretation of the lower than desired inter-rater reliability statistics is that better instruction on the proper application of the scale may be needed in a larger study as well as when using the scale in practice. The approach taken in the pilot study probably will not suffice. The nature and specifics of this instruction will likely need to vary a bit among the study groups. For example, the type and amount of instruction required for university technology transfer practitioners will likely differ to some non-trivial degree from that required for users in the private sector such as venture capital professionals.

There are several possible options for familiarizing study participants with the GTRL scale. A video providing a more detailed explanation of the GTRL scale with examples of its application is one option. Alternatively, one could also familiarize participants with the GTRL scale using a live synchronous overview that not only provides a more detailed explanation with examples of how to apply the scale but also enables participants to ask questions to clarify any confusion.

Consideration 6: What factors should be controlled in a larger validity and reliability study?

In larger validation studies of the reliability of the GTRL scale, it is probably advisable to control for the type of experience the respondents have assessing technology maturity. Although the GTRL scale is intended for a broad spectrum of users, validating the scale in more homogeneous groups will likely improve the quality and internal consistency of the validation studies. Additionally, studies can control for the category of technology. This may enable the collection of cleaner data for a more accurate assessment of inter-rater and intra-rater reliability for a given class of technology. It may also be prudent to control for the prestige of the organization offering the technology and the researchers that created the technology. All these factors could potentially affect how participants rate a technology.

Consideration 7: How viable are asynchronous web-based methods for administering a validity and reliability study?

Asynchronous web-based methods for collecting data for studies of the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale and other such instruments for measuring technology maturity level appear to be viable. There were no issues administering the questionnaires using the web-based survey platform.

Consideration 8: How viable is the approach of presenting marketing summaries of technologies to participants for them to rate?

Presenting several summaries of technologies to participants and having participants rate the technologies based on those summaries is a viable approach for conducting reliability studies. The participants did not appear to encounter any problems. This approach has the advantage of mimicking the nature and structure of how demand-side technology transfer professionals obtain initial information about technologies. Moreover, it allows one to eliminate extraneous information and control for various factors.

Consideration 9: How burdensome will it be for study participants to rate several technologies in multiple rounds?

Having study participants rate several technologies in multiple rounds does not appear to be overly burdensome. The longest time required to complete the questionnaire for the first round was within four (4) days of beginning the questionnaire with most of the participants completing the questionnaire within two (2) days of beginning it. In the second round, all participants completed the questionnaire the same day they started. Having participants rate 10 technologies in multiple rounds did not appear to be overly burdensome.

Consideration 10: What modifications, if any, to the GTRL scale should be considered before performing a larger validity and reliability study?

This was only a small pilot study. As such, the data and results are not sufficient to make broad generalizations. But they do provide some insights, and the results suggest that it may be prudent to consider modifications to either the instrument or the methodology, or both, before implementing larger studies of reliability.

The validation statistics provide clues to the specific modifications that may be helpful. Depending on the reference, the scale level CVI value of 0.8 is considered acceptable for two expert raters. The ICC value for the inter-rater reliability of rating technologies using the GTRL scale had a p-value greater than 0.05 in both rounds. Thus, one could not reject the null hypothesis that there was no agreement among the raters. However, the ICC value for inter-rater reliability did increase from the first round of technology ratings to the second round. Krippendorff’s alpha reliability coefficient also increased from the first round of technology ratings to the second round, but was still well below the 0.667 threshold, which is considered the minimal limit for tentative conclusions (see Krippendorff, 2004). The ICC value for estimating intra-rater reliability ranged from 0.557 to 0.559 and was statistically significant. This suggests that use of the scale is moderately stable over time. However, Krippendorff’s alpha reliability coefficient was 0.531, which is less than the 0.667 threshold considered the smallest acceptable value.

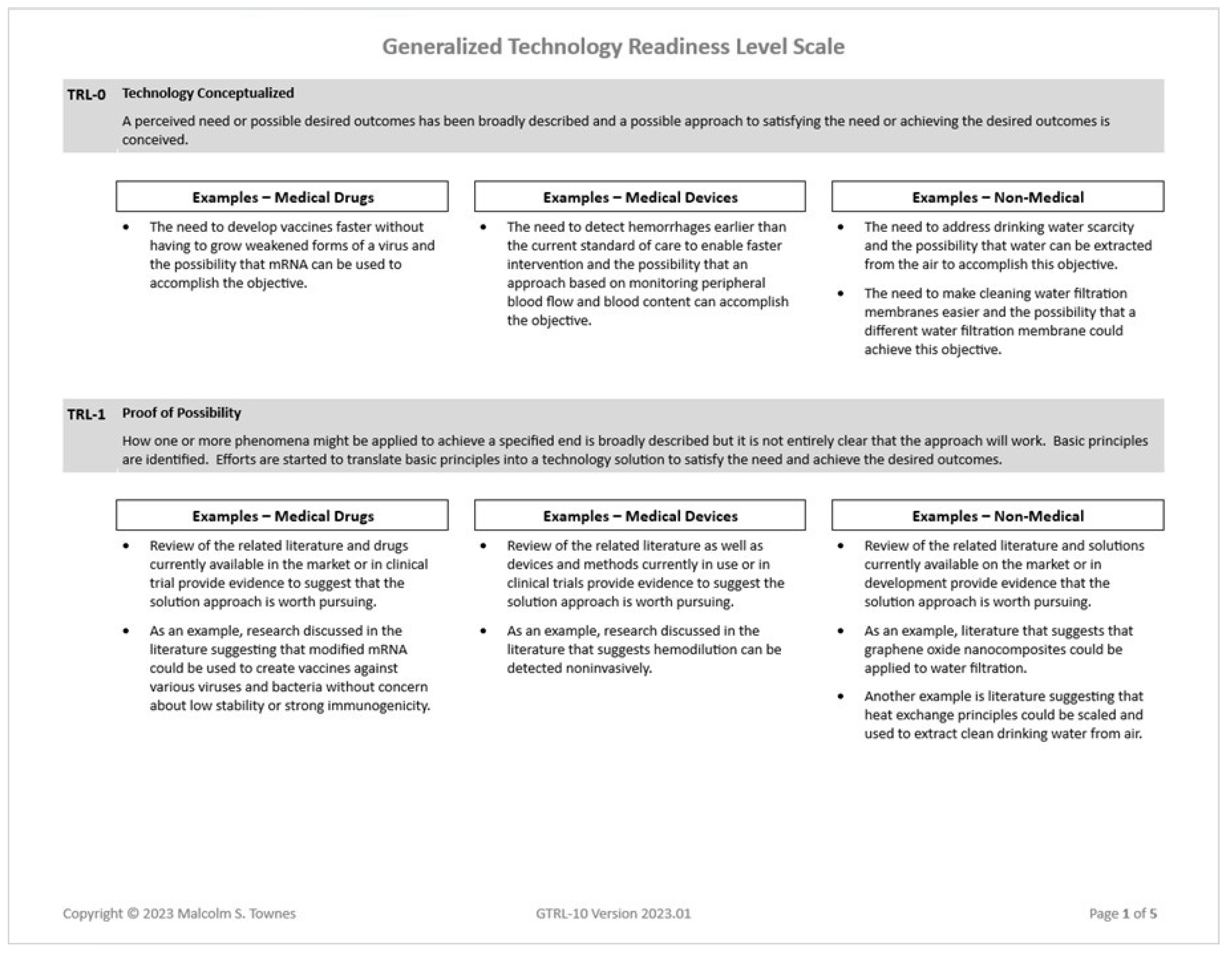

There are several possible modifications to the GTRL scale that can be implemented to address these issues. First, reducing the number of indicators (i.e., readiness levels) on the GTRL scale may be worthwhile. This will likely increase the inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of the instrument. Assessments of technology maturity in certain settings and contexts, such as university and federal laboratory technology transfer, may not need the level of precision represented by the 10-level GTRL scale and other similar scales. The GTRL scale may prove more practical and useful for the intended contexts of its application if it is reduced from a 10-level ordinal scale to a 5-level ordinal scale (see

Table 12 and Supplementary Resource 7).

It may also be worthwhile to re-format the examples for each readiness level and present them in a series of bullet points (see

Figure 4). This may help reduce the cognitive burden of using the instrument and allow users to more quickly locate the relevant information needed to rate a technology using the scale. Finally, it may be helpful to include the higher order concept (HOC) or theme for each readiness level on the instrument. This should be done in a very conspicuous manner that makes it easy to visually locate (see Supplementary Resource 7 and Supplementary Resource 8). The HOC or theme may serve as a shorthand for users to help them mentally organize the details of the instrument and enable users to better apply the scale.

Contribution and Relevance

The GTRL scale and pilot study presented in this paper are relevant to the assessment and evaluation of research and technology for several reasons and contribute to technology transfer research, practice, and policy in several ways. The GTRL scale is more practical for meeting the needs of technology transfer practitioners in contexts outside of space systems and military technology. The features that are incorporated into the instrument help to significantly minimize idiosyncratic variation. This not only makes the GTRL scale more useful for practitioners as they manage research and technology portfolios, but it is also an important improvement to facilitate technology transfer research, particularly investigations about technology maturity level. A more consistent and reliable measurement instrument enables research study replication and facilitates cross-context comparisons. Better empirically derived insights will in turn produce more effective public policies regarding science and technology because they will be rooted in facts supported by data and not just theoretical speculation.

Implications

The results of the study presented in this paper have two main implications. First, the modifications and generalizations of the NASA TRL scale, as represented in the GTRL scale, have the potential to increase the efficacy and efficiency of university technology transfer practices. Given what is in the literature, one can make a reasonably strong case that increasing the maturity level of technologies created at U.S. universities will increase the incidence of university technology transfer. With a valid and reliable measurement instrument, university technology transfer practitioners will be able to better determine how much a given technology needs to be matured and provide better guidance to university researchers. This will enable technology transfer practitioners to better allocate scarce resources to those technologies that hold the most promise for being successfully transferred to the private sector.

Additionally, valid and reliable instruments for measuring the maturity of technologies will likely lead to more effective federal technology transfer policy. Better measurement instruments will enable technology transfer researchers to conduct deeper and more varied explorations of the role and influence of technology maturity on technology transfer as a phenomenon. This includes enabling the synthesis and analysis of data from multiple studies on technology transfer. These improved research capabilities will produce more useful insights to inform public policy decisions.

Limitations

As a pilot study, the primary objective was to test core elements of an approach for assessing the validity and reliability of using a generalized technology readiness level (GTRL) scale as an instrument for evaluating the maturity of technologies, particularly in the context of university technology transfer operations in the United States of America. The primary contribution of the study is mostly limited to presenting the GTRL scale itself and generating insights about the viability of the methodology for assessing its validity and reliability.

The number of participants in the pilot study is too low to enable one to draw conclusions about the validity and reliability of the GTRL instrument. The pilot study lacked sufficient power to detect real differences and thus there is a higher than acceptable risk of a Type II error and failing to detect validity in the instrument. There is also a higher than acceptable risk of a Type I error and thus the possibility of spurious findings regarding validity and inter-rater reliability. The low number of participants also impedes generalizing the validity and inter-rater reliability results to a wider population. Despite these limitations, the analysis of the data collected does enable one to make reasonable conjectures about the potential problems that may be encountered when using a 10-level GTRL scale for assessing the maturity of technologies.

Recommendations for Future Research

It is recommended that future studies of the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale focus on specific contexts and specific cohorts of relatively homogenous participants. Additionally, even though two (2) experts are considered minimally acceptable for content validity studies that employ the CVI method, it is recommended that such studies increase the number of experts to between six (6) and nine (9) to increase the degree of confidence that one can have in the results and minimize the probability of chance agreement.

Finally, if future studies of inter-rater reliability present 10 technologies for rating, then the studies should have at least 10 participant raters to minimize the variance of the intraclass correlation coefficient (see Saito et al., 2006). Two replicates (i.e., rounds of ratings) should be sufficient for studies of intra-rater reliability. In such designs, between 10 and 30 participants should suffice (see Koo & Li, 2016). It is also recommended that future studies of validity and reliability offer financial compensation to incentivize the participation of technology transfer professionals and minimize non-response bias (see Dillman et al., 2014). Following up email recruitment messages with telephone calls may also be necessary to successfully recruit participants (see Dillman et al.).

Conclusion

This paper presented a generalized technology readiness level (GTRL) scale that scholars and practitioners can potentially use to assess the maturity of technologies in a variety of settings and contexts, particularly university technology transfer in the United States of America. It also presented the results of a pilot study to test a methodology for assessing the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale, which may also be useful for assessing other technology maturity measurement instruments that are structured as readiness level scales. The findings of the study suggest that the GTRL scale has promise as a potentially more useful measurement instrument for technology transfer practitioners than the traditional NASA TRL scale, demonstrate the viability of a methodology for evaluating its validity and reliability, highlight areas where the GTRL scale can be improved, and reveal potential methodological issues that researchers may encounter when conducting validity and reliability studies of the GTRL scale as well as strategies for coping with those challenges. This paper contributes to the research management and technology transfer literature by proposing two versions of an instrument for assessing technology maturity that is potentially more practical and possibly less susceptible to idiosyncratic variation than the NASA TRL scale and thus has promise to improve technology transfer research, policy, and practice. It demonstrates a replicable methodology for estimating the validity and reliability of the GTRL scale, which might also be useful for validity and reliability studies of other instruments for measuring the maturity of technologies when such instruments apply the concept of “readiness level”. Moreover, this paper can also help other researchers avoid “re-inventing the wheel” in future efforts to develop and validate such measurement instruments.

Funding

The author did not receive funding support from any organization to assist with this work or the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Keith D. Strassner and Mr. Eric W. Anderson, J.D., who served as domain experts for assessing the content validity of the generalized technology readiness level scale.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data availability

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this paper and its supplementary files. All other data generated during the study not included in this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

This research did not require Institution Review Board approval because it did not involve research on human participants or animals as subjects.

Informed Consent

Informed consent for patient information to be published in this article was not required because the study did not use patient information.

Declaration regarding artificial intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies

During the preparation of this work the author did not use AI or AI-assisted tools to write any text and takes full responsibility for the content of this paper.

References

- Albert, T. (2016). Measuring technology maturity: Theoretical aspects. In Measuring technology maturity: Operationalizing information from patents, scientific publications, and the web (pp. 9-113). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Allaire, J. J. (2019). RStudio: Integrated development for R (Version 1.2.1335) [Software]. RStudio. Retrieved May 10, 2019 from https://rstudio.com/products/rstudio/#rstudio-desktop.

- Almanasreh, E., Moles, R., & Chen, T. F. (2019). Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(2), 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Banke, J. (2010, August 7, 2017). Technology readiness levels demystified. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved August 24, 2018 from https://www.nasa.gov/topics/aeronautics/features/trl_demystified.html.

- 5. Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-517, 94 Stat. 3015 (1980). Retrieved February 6, 2022 from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-94/pdf/STATUTE-94-Pg3015.pdf.

- Bhattacharya, S., Kumar, V., & Nishad, N. (2022). Technology readiness level: An assessment of the usefulness of this scale for translational research. Productivity, 62(2), 112-124. [CrossRef]

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (2002). Validating scales and indexes. British Medical Journal, 324(7337), 606-607. [CrossRef]

- Chukhray, N., Shakhovska, N., Mrykhina, O., Bublyk, M., & Lisovska, L. (2019). Methodical approach to assessing the readiness level of technologies for the transfer. In N. Shakhovska & M. O. Medykovskyy (Eds.), Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (volume 1080). Conference on Computer Science and Information Technologies, Lviv, Ukraine. [CrossRef]

- Collier, D., LaPorte, J., & Seawright, J. (2012). Putting typologies to work: Concept formation, measurement, and analytic rigor. Political research quarterly, 65(1), 217-232. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. (2010). The magical mystery four: How is working memory capacity limited, and why? Current Directions Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57. [CrossRef]

- 11. Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Science and Technology. (2003). Technology readiness assessment (TRA) deskbook. U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved December 11, 2023 from https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA418881.pdf.

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American journal of theoretical and applied statistics, 5(1), 1-4. [CrossRef]

- 14. European Association of Research and Technology Organizations. (2014). The TRL scale as a research and innovation policy tool, EARTO recommendations [Report]. Retrieved July 4, 2018 from http://www.earto.eu/fileadmin/content/03_Publications/The_TRL_Scale_as_a_R_I_Policy_Tool_-_EARTO_Recommendations_-_Final.pdf.

- Fellnhofer, K. (2015). Literature review: Investment readiness level of small and medium sized companies. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 7(3/4), 268-284. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T. D. (2023). psychometric: Applied psychomeric theory (Version 2.4) [Software program]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). Retrieved September 13, 2024 from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psychometric/index.html.

- Gamer, M., Lemon, J., Fellows, I., & Singh, P. (2019). irr: Various coefficients of interrater reliability and agreement (Version 0.84.1) [Software program]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). Retrieved September 13, 2024 from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/irr/index.html.

- Guliyeva, A. (2023). Types of ambiguity in oral and written speech in daily communication (Publication Number 31312711) [Master's thesis, Khazar University]. Baku, Azerbaijan. https://www.proquest.com.

- Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Hockstad, D., Mahurin, R., Miner, J., Porter, K. W., Robertson, R., & Savatski, L. (2017). AUTM 2017 licensing activity survey Association of University Technology Managers, . Retrieved December 11, 2023 from https://autm.net/surveys-and-tools/surveys/licensing-survey/2017-licensing-activity-survey.

- Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). More than just convenient: The sicentific merits of homogenous convenience samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2), 13-30. [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Sheehan, R. (2015). Technical communication today Fifth ed., Vol. Pearson.

- Juan, Z., Wei, L., & Xiamei, P. (2010). Research on technology transfer readiness level and its application in university technology innovation management, 2010 International Conference on E-Business and E-Government, 2010, 1904-1907. Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE). [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology Second ed., Vol. SAGE Publications.

- Kuhn, T. S. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions Fourth ed., Vol. University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1962).

- Kyriakidou, V., Michalakelis, C., & Sphicopoulos, T. (2013). Assessment of information and communications technology maturity level. Telecommunications Policy, 37(1), 48-62. [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel psychology, 28(4), 563-575. [CrossRef]

- Leon, A. C., Davis, L. L., & Kraemer, H. C. (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of psychiatric research, 45(5), 626-629. [CrossRef]

- Lezama-Nicolás, R., Rodríguez-Salvador, M., Río-Belver, R., & Bildosola, I. (2018). A bibliometric method for assessing technological maturity: The case of additive manufacturing. Scientometrics, 117(3), 1425-1452. [CrossRef]

- Li, A., Schoppe, L., & Lockney, D. (2023). Technology readiness level scale: Is it useful for TTOs? TechInsight. Retrieved March 14, 2025 from https://techpipeline.com/article/technology-readiness-level-scale-is-it-useful-for-ttos/.

- Mankins, J. C. (1995). Technology readiness levels [Whitepaper]. Advanced Concepts Office, Office of Space Access and Technology, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved August 24, 2018 from http://www.artemisinnovation.com/images/TRL_White_Paper_2004-Edited.pdf.

- Mankins, J. C. (2009a). Technology readiness and risk assessments: A new approach. Acta Astronautica, 65(9-10), 1208-1215. [CrossRef]

- Mankins, J. C. (2009b). Technology readiness assessments: A retrospective. Acta Astronautica, 65(9-10), 1216-1223. Retrieved May 29, 2021 from http://www.onethesis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/1-s2.0-S0094576509002008-main.pdf.

- Munari, F., Rasmussen, E., Toschi, L., & Villani, E. (2016). Determinants of the university technology transfer policy-mix: A cross-national analysis of gap-funding instruments. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41, 1377-1405. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, R. (2012). Stage of development and licensing university inventions. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- 36. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. (2020). Survey of federal funds for research and development, fiscal years 2018-19. National Science Foundation. Retrieved May 29, 2021 from http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/fedfunds/.

- 37. National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2022). Federal laboratory technolgy transfer fiscal year 2019: Summary report to the President and the Congress. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved November 1, 2023 from https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2022/09/29/FY2019%20Federal%20Technology%20Transfer%20Report.pdf.

- National Institutes of Health, N. C. f. C. a. I. H. (2023, June 7). Pilot studies: Common uses and misuses. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved October 6, 2023 from https://www.nccih.nih.gov/grants/pilot-studies-common-uses-and-misuses.

- National Science Foundation for the Future Act, H.R.2225, 117th Cong. (1st Sess. 2021), (2021). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2225.

- Nolte, W., & Kruse, R. (2011, October 26). Readiness level proliferation [Powerpoint slides]. National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) 14th Annual Systems Engineering Conference, October 24-27, 2011. San Diego, California, United States of America. https://ndia.dtic.mil/wp-content/uploads/2011/system/13132_NolteWednesday.pdf.

- Nolte, W. L. (2008). Did I ever tell you about the whale?: Or measuring technology maturity. Information Age Publishing.

- 42. Office of the Federal Register. (2022, March 1). Avoiding ambiguity. National Archves. Retrieved August 10, 2025 from https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/write/legal-docs/ambiguity.html.

- Olechowski, A. L., Eppinger, S. D., & Joglekar, N. (2015). Technology readiness levels at 40: A study of state-of-the-art use, challenges, and opportunities, 2015 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), August 2-6, 2015. Portland, Oregon, United States of America. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). [CrossRef]

- Olechowski, A. L., Eppinger, S. D., Tomaschek, K., & Joglekar, N. (2020). Technology readiness levels: Shortcomings and improvement opportunities. Systems Engineering, 23(2). [CrossRef]

- Price, S. C., & Sobocinski, P. Z. (2002). Gap funding in the USA and Canada. Industry and Higher Education, 16(6), 387-392. [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. (2024). psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research (Version 2.4.6.26) [Software program]. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN).

- Royal, K. (2016). “Face validity” is not a legitimate type of validity evidence! The American Journal of Surgery, 212(5), 1026-1027. [CrossRef]

- Sadin, S. R., Povinelli, F. P., & Rosen, R. (1989). The NASA technology push towards future space mission systems. Acta Astronautica, 20, 73-77. [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y., Sozu, T., Hamada, C., & Yoshimura, I. (2006). Effective number of subjects and number of raters for inter-rater reliability studies. 25(9), 1547-1560. [CrossRef]

- Schacht, W. H. (2012). The Bayh-Dole act: selected issues in patent policy and the commercialization of technology. (RL30276). Washington, DC: Library of Congress. Retrieved January 9, 2020 from http://crsreports.congress.gov.

- Schwartz, D. (2023). Technology readiness level scale: Is it useful for TTOs? Technology Transfer eNews [Blog]. Retrieved January 11, 2024 from https://techpipeline.com/article/technology-readiness-level-scale-is-it-useful-for-ttos/.

- Sedgwick, P. (2013). Convenience sampling. Bmj, 347. [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, M., Souza, A. S., & Oberauer, K. (2019). How does chunking help working memory? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(1), 37-55. [CrossRef]

- 54. The R Foundation. (2023). The R project for statistical computing (Version 4.2.3) [Software]. The R Foundation. https://www.R-project.org.

- Townes, M. S. (2022). The influence of technology maturity level on the incidence of university technology transfer and the implications for public policy and practice (Publication Number 29209868) [Doctoral dissertation, Saint Louis University]. ProQuest.

- Townes, M. S. (2024a). The role of technology maturity level in the cccurrence of university technology transfer. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. [CrossRef]

- Townes, M. S. (2024b). TRL scale is a useful if imperfect tool for TTOs. Technology Transfer Tactics. https://techpipeline.com/article/trl-scale-is-a-useful-if-imperfect-tool-for-ttos/.

- United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021, S.1260, 117th Cong. (1st Sess. 2021), (2021). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1260.

- Van Teijlingen, E., & Hundley, V. (2010). The importance of pilot studies. Social Research Update, 35(4), 49-59. Retrieved November 13, 2023 from https://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU35.html.

- Westerik, F. H. (2014). Investor readines: Increasing the measurability of investor readiness [Master's thesis, University of Twente].

- Yadav, A., Patel, A., & Shah, M. (2021). A comprehensive review on resolving ambiguities in natural language processing. AI Open, 2, 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaie, F. (2003). Content validity and its estimation. Journal of medical education, 3(1), 25-27. Retrieved October 11, 2023 from https://brieflands.com/articles/jme-105015.pdf.

- Zorrilla, M., Ao, J. N., Terhorst, L., Cohen, S. K., Goldberg, M., & Pearlman, J. (2022). Using the lens of assistive technology to develop a technology translation readiness assessment tool (TTRAT)™ to evaluate market readiness. Disability and Rehabilitation-Assistive Technology, 1145-1160. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).