1. Introduction

The term interstitial lung disease (ILD) includes an heterogeneous group of more than 200 diseases, characterized by histological and radiological findings of inflammation and/or fibrosis affecting the interstitium of the lungs [

1,

2]. Although several classifications have been made, ILDs can be subdivided into autoimmune-related ILDs (e.g., connective tissue diseases associated-ILDs [CTD-ILDs]), exposure-related ILDs (e.g., hypersensitivity pneumonitis, drug or toxic-induced ILDs), ILDs involving cysts or airspace filling, sarcoidosis, orphan diseases and idiopathic ILDs (from which the most common is the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF]) [

3,

4]. IPF is a progressive-fibrosing ILD with the radiological and/or histological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), in the exclusion of environmental factors ascribed to ILD (such as domestic and occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue diseases or drug toxicity) [

5,

6]. However, these conditions may be sometimes coetaneous but not judged to be sufficient to exclude the diagnosis of IPF [

7]. Estimates of prevalence and incidence of IPF are inaccurate due to the complex nature of diagnosing the disease, but among 7,000 – 101,500 develop the disease annually [

8]. Due to this health burden, it is of crucial importance to detect biomarkers that are clinically useful in establishing a differential diagnosis and prognosis between IPF and other forms of progressive pulmonary fibrosis [

4,

9].

Regarding prognosis, one of the main characteristics affecting the progression of ILDs is the radiological pattern, among which UIP, a definite feature of IPF, confers worse clinical outcome to affected patients [

10,

11]. Several mediators are involved in the pathological progression of IPF, such as epithelial cells, mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts and immune cells, which through fibrogenesis participate in lung function decline. Processes such as protein homeostasis imbalance and mitochondrial damage in lung tissue, among others, have exhibited a critical role in the pathophysiology of IPF. Considering molecular factors that may have relevance in the clinical management of IPF patients, previous works reported that telomere length (TL) and telomerase activity could be impaired in this group of ILDs [

12]. Telomeres, DNA sequences located at the end of the eukaryotic chromosomes, protect DNA from progressive shortening during normal cell replication [

13]. TL has been implied in a variety of lung diseases, as their shortening limits the capacity of tissue renewal in the lungs [

14,

15]. Although the role of telomere shortening as a driving factor for the development of lung diseases such as ILDs has been more widely investigated, little is known about the impact of tissue telomere status on the prognosis of IPF

versus other ILDs.

In this work, our main objective was to investigate the role of TL and telomerase activity as possible biomarkers with clinical utility in establishing the different prognosis of patients affected by IPF and those who develop other ILDs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Tissue Samples

The study population included 61 patients referred to the Thoracic Surgery Service of the San Carlos Hospital in Madrid (Spain) and submitted to surgical lung biopsy for ILD diagnosis. All participants were recruited subsequently and regardless of gender, age or disease stage.

A total number of 28 IPF (7 women and 21 men) and 33 (8 women and 25 men) patients with other ILDs were included prospectively between 2017 and 2023. The median age ± interquartile range (IQR) was 70 ± 9 years for IPF patients and 63 ± 17 years for patients with other ILDs.

Table 1 shows demographic variables (gender, age), co-morbidities and exposures from all the participants considered in this work according to final diagnosis. Both groups were comparable except for age and tobacco exposure, which were significantly higher in the IPF population.

Written approval to develop this study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (C.I. 19/104-E_BS, 26/3/2019). In addition, written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to enrolment. Exclusion criteria were the absence of a lung diagnostic biopsy indication or the lack of signed informed consent.

After surgical resection, tissue samples were frozen until processed at -80˚C, using Tissue-Tek® OCT as a freezing medium. All the samples were handled by the Biobank of the Health Research Institute of San Carlos Hospital (IdISSC) in Madrid (B.0000725), from the national network of Biobanks, project PT2020/00074 subsidized by the Carlos III Institute of Health (ISCIII) and co-funded by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). Cryostat-sectioned, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained samples from each tissue block were examined microscopically by two independent pathologists to confirm pathological diagnosis.

2.2. Analysis of Telomere Length and Telomerase Activity

Both relative telomere length (TL) and telomerase activity were analysed in fresh Tissue-Tek® OCT-frozen lung tissue samples. For DNA extraction and protein extraction, 20 cuts of tissue of 10 µm and 10 cuts of 10 µm were used, respectively. In both cases, OCT was removed prior to the extraction by washing the cuts with 500 μl of PBS and centrifuging at 4,000 rpm during 10 minutes at room temperature.

Genomic DNA extraction for TL determination was performed according to the Blin and Stafford procedure [

16]. Relative TL in ILD samples was determined by a real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) method based on the Cawthon procedure [

17]. This technique consists of the calculation of the T/S ratio, a relative parameter of the telomere length of the sample that is given by the comparison of the copy number of its telomere sequence (T) between the number of copies of a single copy gene (S), with respect to a reference DNA. As a single copy gene, RPLP0 (Ribosomal Protein Large P0) gene was used. Shortly, two real-time qPCR amplifications per sample were performed, one for quantification of telomeres and the other for quantification of RPLP0. Each reaction contained 20 ng of DNA, 10 μl of the 2x PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madrid, Spain), which contained ROX™ as passive reference dye, as well as the corresponding primers for each reaction (Thermo Fisher Scientific), in 20 μl of final volume. The following primer sequences were used [

17,

18]: TELOMERE 5´CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT3´ (forward) and 5’GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT 3´ (reverse);

RPLP0 5´CAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC3´ (forward) and 5´CCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA3´ (reverse).

For the amplification of telomere sequence, concentrations of 300 nM of the forward primer and 900 nM of the reverse primer were used, and for the amplification of the RPLP0 gene, 300 nM of the forward primer and 500 nM of the reverse primer were used.

All reactions were performed by triplicate. For each pair of primers, a standard curve was included by using serial dilutions of a pooled human DNA of known concentration obtained from non-tumour lung tissues, in order to calculate the efficiency (E) of each experiment (

, where “slope” refers to the slope of the regression line that relates the Ct value versus the logarithm of the DNA concentration). The same pooled DNA was used as a reference DNA for the T/S ratio calculation. T/S ratio was calculated using the model established by Pfaffl [

19]:

This T/S ratio constitutes a relative indicator of telomere length. Higher values of the T/S ratio are related to longer telomere sequences.

For telomerase activity determination, total protein extracts were obtained and processed according to the protocol of the TeloTAGGG™ Telomerase PCR ELISA kit (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). This procedure allows to establish a semi-quantitative assay that consists in a telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP)-based telomerase polymerase chain reaction (PCR), followed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect the PCR products. For each sample, assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions both in the direct and 10-fold diluted protein extract. Samples with OD450nm ≥ 0.2 were considered as telomerase positive.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Variables were described using medians and IQR or proportions according to the properties (quantitative or categorical, respectively) of the data. Comparisons and statistical tests were performed based on the quantitative (t Student, Mann–Whitney U) or categorical (Chi-squared) nature, and the normality or non-normality of the data, as appropriate.

T/S ratio was categorized according to the Cutoff Finder tool [

20], which set 0.95 as the cut-off point for classifying patients depending on TL of their tissue samples. Specifically, patients with lung tissue samples showing a T/S ratio < 0.95 were classified in the group of shorter TL, whereas patients whose tissue samples showed a T/S ratio ≥ 0.95 were classified in the group of longer TL.

Survival curves according to clinico-pathological variables and categorized T/S ratio were obtained based on the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with a log-rank test. Patients who died in the postoperative period (1 month) were excluded from the survival studies. The median follow-up period of the series was 24 months (range 2 – 70).

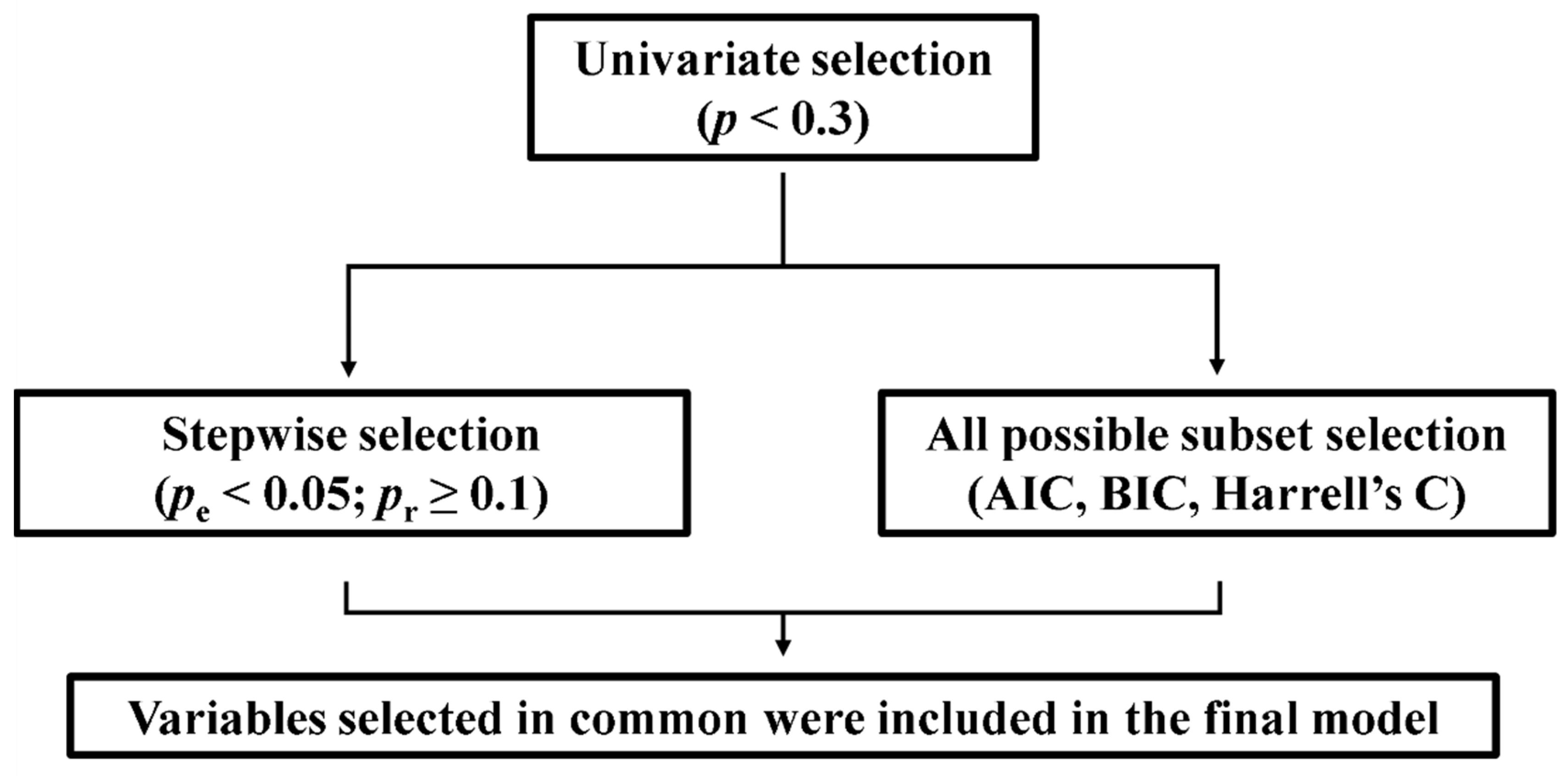

A Cox regression model was performed to assess the impact on mortality of clinical variables and T/S ratio. As shown in

Figure 1, the variables to be included in the Cox regression were selected using a step-by approach: first, a univariate Cox test was performed for each variable, and those with statistical

p < 0.3 were refined by means of backward and forward stepwise selection and the best equation of all possible subsets according to the Harrell’s C, Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). These strategies allow the selection, from a set of predictor variables, of those that would best fit a regression model [

21]. We also tested for the validity of the model (proportionality assumption, log-linear relationship between instant rate of incidence and explicative variables, and presence of influential individuals). The statistical significance value was set at

p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with STATA IC16.1 (Stata-Corp LLC, Texas, USA) and IBM

® SPSS

® Statistics software package version 27 (IBM Inc.).

3. Results

3.1. Survival Analysis Based on Clinic-Pathological Variables and T/S Ratio

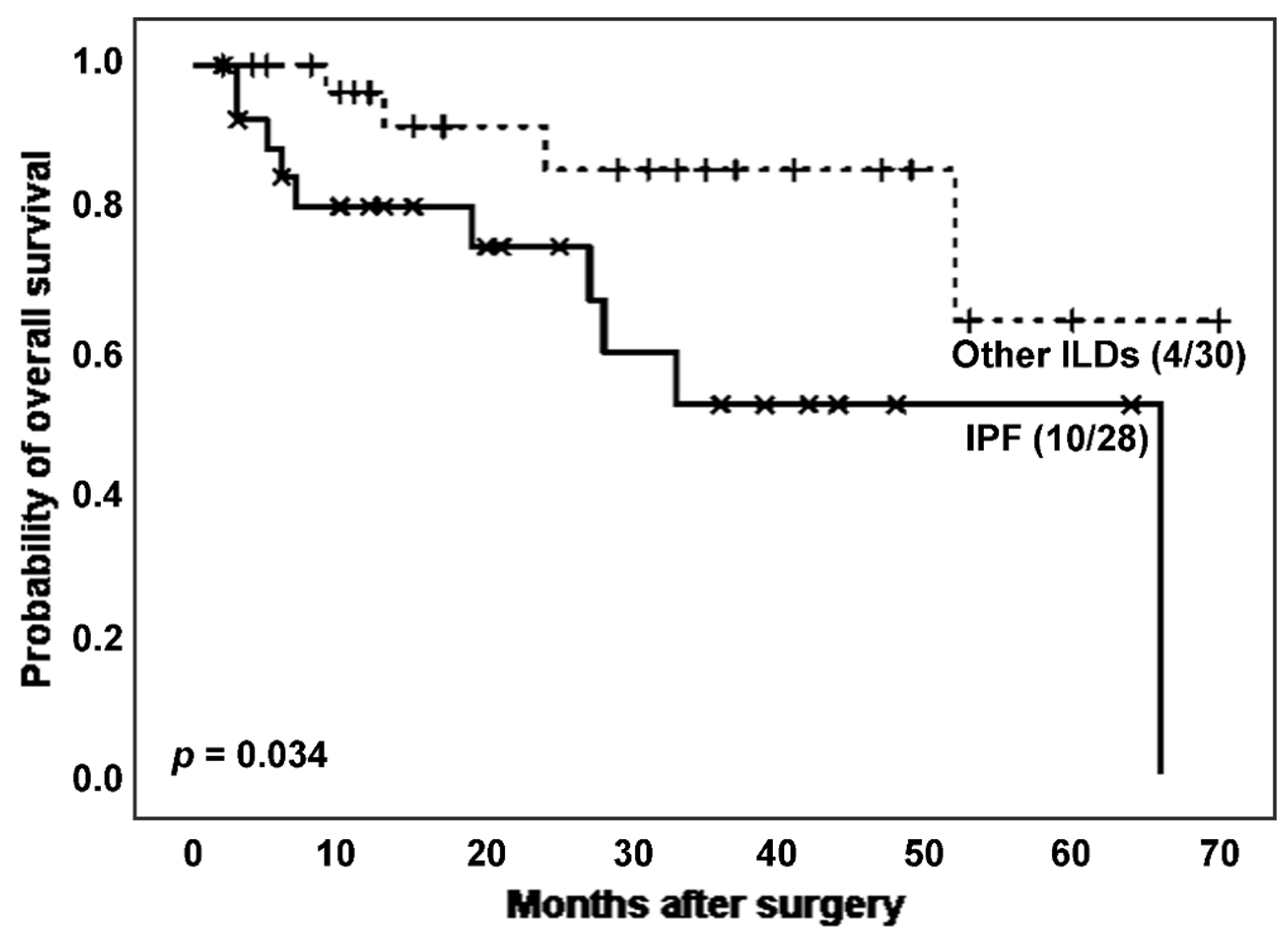

When analysing the effect of IPF on the survival of ILD patients (

Figure 2), IPF patients experienced more death events (10 [35.7%]

vs. 4 [13.3%]) and showed a significantly lower survival time after surgery than patients with other ILDs (estimated Kaplan-Meier probability of death: 100.0%

vs. 36.1%, log rank-test

p = 0.034). The mean T/S ratio was lower in the IPF group, although the difference was not statistically significant (0.762

vs. 0.856,

p = 0.330 in Student’s T test). Regarding telomerase activity, the proportion of telomerase positivity was higher in the group with higher TL, e.g., the non-IPF group (23 [82.1%]

vs. 15 [65.2%],

p = 0.168 in Chi-squared test).

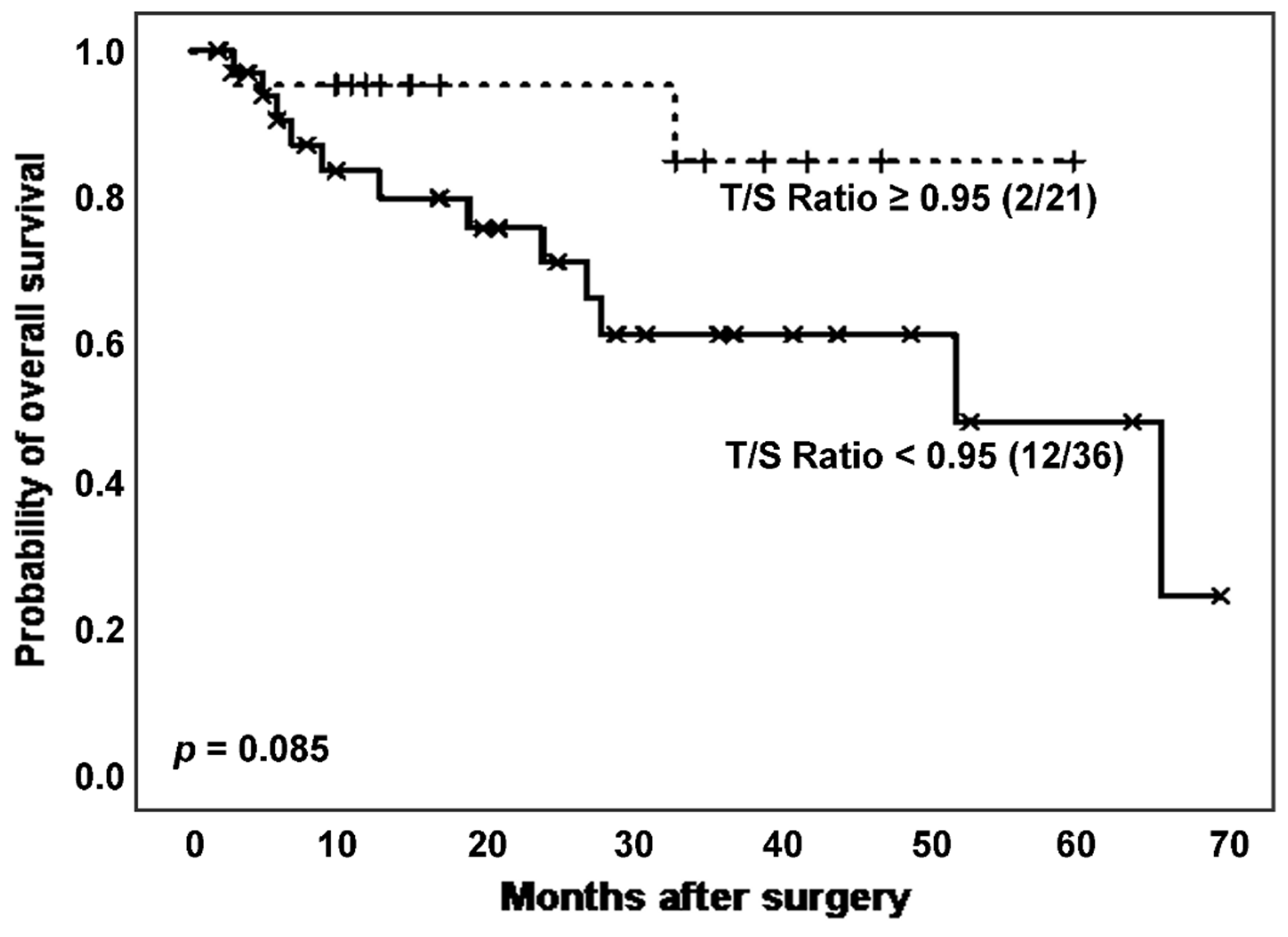

Following, we considered the effect of TL on survival of the total population of patients affected by ILD. Specifically, we analysed survival curves according to T/S ratio (

Figure 3) and found a higher mortality rate (12 [33.3%]

vs. 2 [9.52%]) and poorer survival, with borderline significant differences (estimated Kaplan-Meier probability of death: 75.8%

vs. 15.3%; log rank-test

p = 0.085), in patients with shorter TL (

Figure 3). Telomerase activity evaluation reported a greater number of positive cases in those patients with T/S ratio above the stablished threshold (17 [81.0%]

vs. 21 [70.0%],

p = 0.377 in Chi-squared test).

When considering the effect of TL only on the survival of the group of IPF patients, those patients with shorter telomeres (T/S ratio < 0.95) showed lower survival than the ones with longer telomeres (number of deaths: 8 [42.1%] vs. 2 [25.0%]; estimated Kaplan-Meier probability of death: 100.0% vs. 41.7%; p: 0.464).

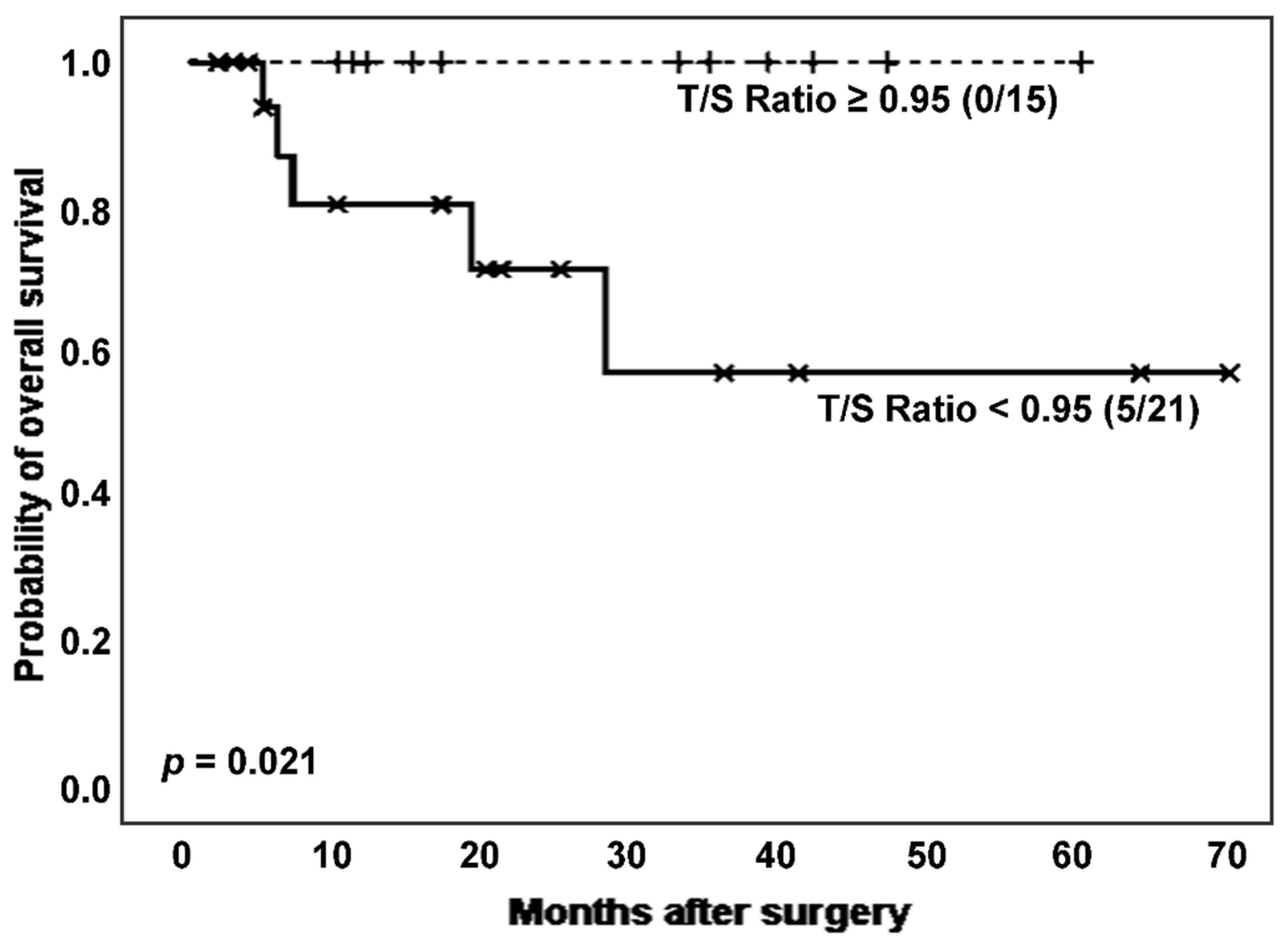

Next, considering the effect of cancer on TL, we established survival analyses according to categorized T/S ratio in ILD patients with and without lung cancer. Interestingly, in the subpopulation of ILD patients without cancer (n = 36), those with shortened TL had a significantly poor clinical evolution, comparing to the group showing longer TL (number of deaths: 5 [23.8%]

vs. 0 [0.0%]; estimated Kaplan-Meier probability of death: 42.9%

vs. 0.0%; log rank-test

p = 0.021) (

Figure 4). Telomerase reactivation was also lower in the patients with shortened TL (12 [80.0%]

vs. 11 [68.8%],

p = 0.474 in Chi-squared test).

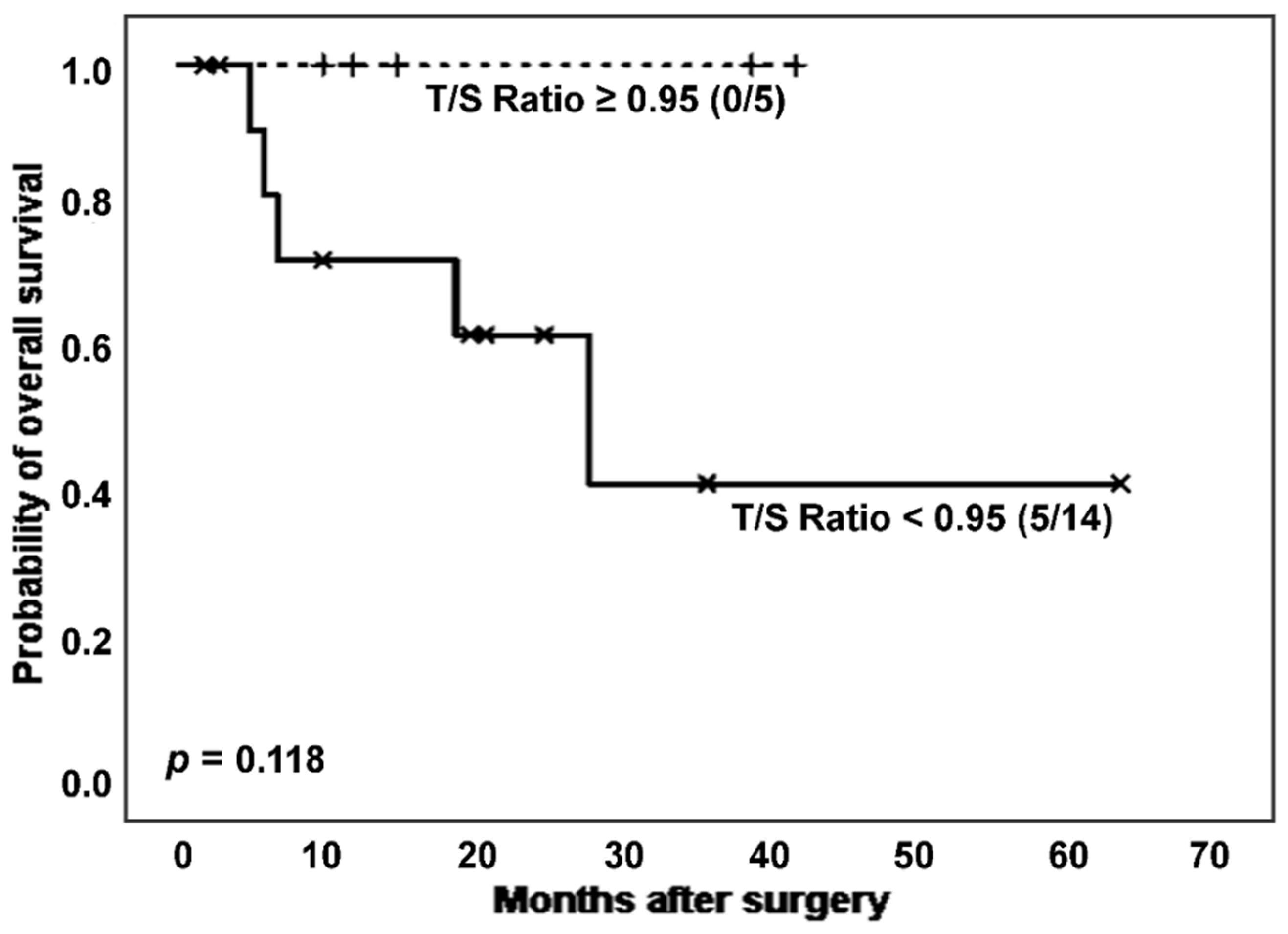

Only considering non-cancer IPF patients, survival differences in relation to T/S ratio showed a trend toward statistical significance (

Figure 5). Thus, after excluding patients with cancer, subjects affected by IPF and showing shortened telomeres experienced worse prognosis than those with longer TL (number of deaths: 5 [35.7%]

vs. 0 [0.0%]; estimated Kaplan-Meier probability of death: 58.4%

vs. 0.0%), although differences did not reach statistical significance (

p = 0.118, log-rank test). In the group of cases with a more adverse prognosis, a slightly lower telomerase activation rate was observed, although without significant differences (7 [63.6%]

vs. 3 [60.0%],

p = 0.889 in Chi-squared test).

Non-IPF patients without cancer did not report any mortality events.

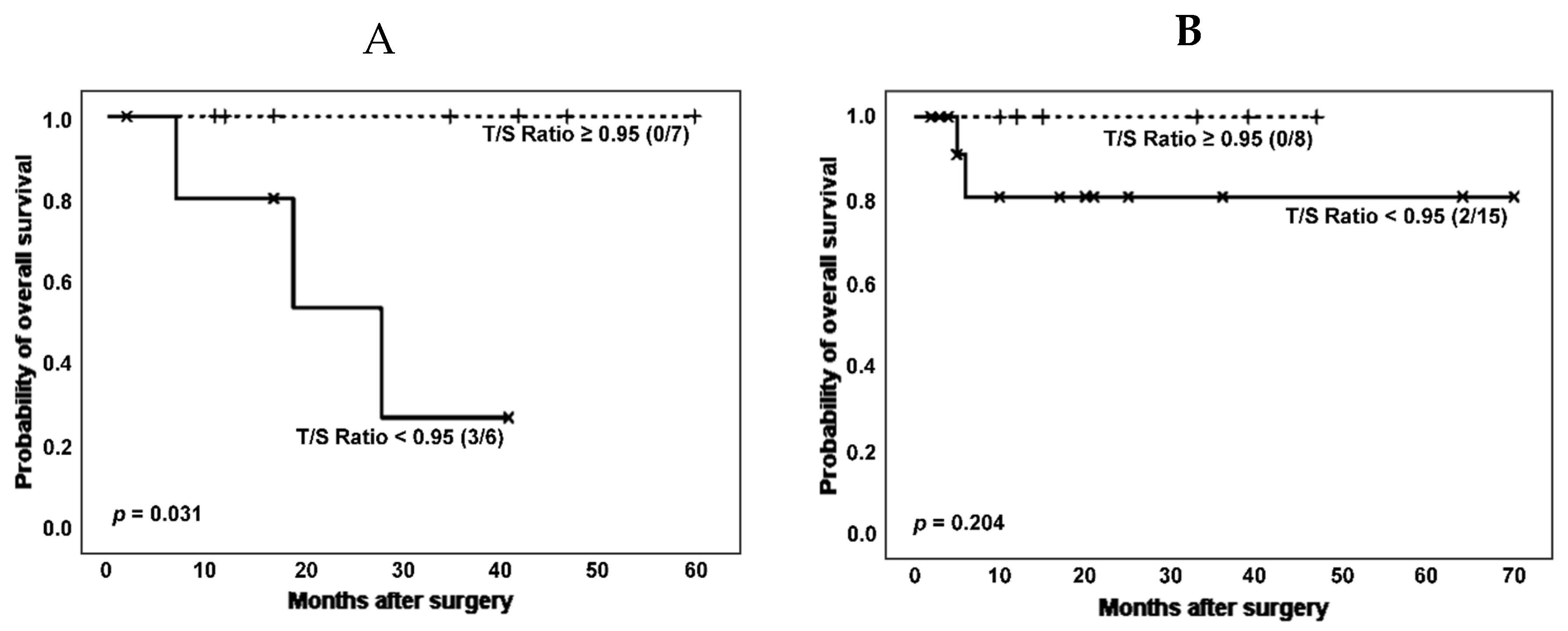

Another clinical variable of interest in the group of pathologies considered in this work is the development of rheumatic diseases. Therefore, we then performed survival analysis according to categorized T/S ratio and stratifying by the co-occurrence of ILD and rheumatoid disorders (RD) in patients without cancer (

Figure 6).

When patients without cancer were stratified based on ILD and RD co-occurrence, the effect of shorter telomeres on survival could be noticed both in patients with and without a RD, although it was only significant in the group of RD patients (number of deaths: 3 [50.0%] vs. 0 [0.0%]; estimated Kaplan-Meier probability of death: 73.0% vs. 0.0%, log rank-test p = 0.031). Telomerase activity was again decreased in patients with shorter TL (3 [60.0%] vs. 5 [71.4%], p = 0.679 in Chi-squared test).

In summary, our results indicate that TL constitutes a relevant factor in establishing the clinical prognosis of patients affected by ILD, with patients having shorter telomeres showing a worse prognosis.

3.2. Cox Regression Analysis

In order to assess the impact on mortality of clinical variables and T/S ratio, we performed a Cox regression analysis. The first step of the variable selection process (variables with

p < 0.3 in univariate Cox regression) yielded as potential prognostic factors age, IPF, RD and cancer, as well as the interactions of T/S ratio with age, IPF and RD. We applied a second selection procedure, by means of stepwise selection and the best equation of all subsets, which proposed age, the presence of IPF, RD, T/S ratio and the interaction between T/S ratio and RD as significant variables. The whole process of variable selection is described in the

Supplementary material. Except age, the clinical variables selected were implied in prognosis (

Table 2). T/S ratio would behave as an effect modifying variable of RD.

A diagnosis of the selected model (detailed in the

Protocol S1) did not reveal significant disruptions in its assumptions.

3.3. Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with IPF and RD.

To explain the modifying effect that T/S ratio has on the survival impact of RD at a molecular level, we investigated the possible link between shorter telomeres and a higher oxidation status due to inflammation. Thus, we analysed the correlation between TL and several blood inflammatory parameters (fibrinogen, C reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and ferritin) measured at the time lung tissue was obtained.

We found that, in patients without cancer, ferritin was significantly increased in cases with RD and IPF co-occurrence, when compared to patients with just IPF (

p = 0.032, Mann Whitney U test) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

In this work, we evaluated the role of TL and telomerase activity in lung tissue samples of patients affected by ILDs according to the presence of a IPF

vs non-IPF ILDs. As far as we are concerned, this is the first work to evaluate the role of lung tissue TL in the prognosis of patients with ILDs. One previous work used tissue TL as a biomarker for disease development [

22], although the majority of studies have focused on peripheral blood leukocyte TL as a biomarker for the presence of ILD [

23]. Thus, several other works have shown a worse prognosis in patients with ILDs, such as IPF and CTD-ILD patients, which had shortened telomeres in peripheral white blood cells [

24,

25,

26,

27].

We detected a worse clinical evolution in IPF patients, especially in the ones with shortened TL in lung tissues. Specifically, we found an estimated median survival of 66 months in those patients with IPF, similar to that reported elsewhere [

24,

25], and survival was even lower in those IPF patients with shorter telomeres in lung tissue (28 months). TL of peripheral blood cells has been proposed as a reflection of the overall TL of the individual [

28], including lung tissue. Nevertheless, considering that lung tissue of patients with IPF harbours hyperplastic type II pneumocytes and fibroblast foci, whereas inflammatory cells are absent [

29,

30,

31], it is challenging to elucidate how peripheral leukocyte TL reflects telomere status in lung tissue. Despite this, telomere shortening has been observed to be systemic in patients with IPF [

32] and an increased systemic oxidative stress has also been reported [

33] in these patients.

Molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain involvement of telomere shortening in fibrosis or poor prognosis observed in ILDs with UIP patterns, such as IPF and CTD-ILDs. Telomere shortening in epithelial type II cells and alveolar stem cells, caused by conditions that increase cell turnover, oxidative stress or inflammation (e.g. smoking, mutations and other noxious factors) would lead to a senescence-associated phenotype and influence the native microenvironment and local cell signalling, including increased expression of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) [

34]. This mechanism would trigger the deposition of excessive extracellular matrix filaments in the interstitial space and the gradual loss of healthy alveolar epithelial cells in the lung parenchyma. Moreover, when shortened telomeres reach a critical length, cell apoptosis occurs with a further loss of healthy alveolar epithelial type 2 cells and lung dysfunction. In this regard, one study in explanted lungs, showed that telomere shortening was associated with increased total collagen and chromosomal damage, and this damage increased elastin and structural disease severity [

35]. This mechanism has also been proposed for other diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In fact, telomere dysfunction in lung pathophysiology is significant because some diseases, such as IPF, can be familial by inheriting mutations on telomerase reverse transcriptase (

TERT) or telomerase RNA component (

TERC), regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1 (

RTEL1), poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (

PARN) implied in maturation, dyskerin (

DKC1) implied in trafficking, TERF1-interacting nuclear factor 2

(TINF2) implied in shelterin function [

36,

37,

38].

In our study, we were not able to demonstrate an independent role for TL in the worse prognosis of ILD patients, for several possible reasons. Differences in populations might have accounted as we included patients with cancer, and the population size was modest. Additionally, we included ILD patients being subsidiary to surgery which might have caused a selection bias. Furthermore, other molecular mechanisms that were not investigated could be involved. Several works highlight the role of the mucin-like protein MUC5B, metalloproteinases MMP7 and MMP9, and interleukins such as CXCL10 and IL-23 in the risk of developing the disease or a more severe disease [

39]. Perhaps, when integrating all this information, we could better interpret a patient's prognosis in a personalized approach. Therefore, we suggest that a panel of molecular markers to assess patient prognosis would enable a more comprehensive approach [

40,

41].

Although telomere shortening did not show an independent role in the risk of death of our population, it did modify the impact that RD had on survival. In fact, in a multivariate analysis, TL displayed a modifying role on the risk of death associated with the presence of RD; and a link between higher inflammatory parameters and shorter TL in patients with IPF and concomitant RD was detected.

Some authors have outlined that CTD-ILDs have a worse prognosis than other ILDs, and similar to IPF, when a UIP pattern is present [

42,

43]. This emphasizes the importance of combining the radiological and pathological features [

44] along with molecular markers when assessing ILD prognosis. Surprisingly, cancer did not impact significantly on mortality in the Cox regression, perhaps due to early stages of the patients at diagnosis, which anticipated a good prognosis. A higher impact of TL in patients with IPF and RD co-occurrence may be explained because the RD exhibit additional mechanisms underlying TL shortening. We hypothesized that a higher inflammatory state could be the rationale for the performance of TL as a modifying variable of RD. A higher inflammation would lead to increased production of oxygen reactive species, which in turn would damage DNA and shorten telomeres. We conducted a very indirect analysis and showed that patients with concomitant IPF and RD and higher inflammatory parameters tended to have shorter TL. Some studies point at the same direction regarding the involvement of inflammation and short telomeres [

45,

46,

47]. TL has also been reported to have a modifying variable effect in other contexts. For example, in a study assessing the role of TL in the risk of death in IPF patients treated with immunosuppression, the authors showed a significant interaction between immunosuppression medication (e.g. azathioprine, prednisone and N-acetylcysteine) and TL in peripheral leukocytes [

48]. Therefore, the authors identified leukocyte TL as a biomarker for patients with IPF at risk for poor outcomes when exposed to immunosuppression. Similarly, we identified tissue TL as a biomarker for patients with ILD at risk of poor outcomes when exposed to concomitant CTDs.

Despite the role of TL in the prognosis of ILD established in observational studies, difficulties in implementation of TL as prognostic marker in clinical practice may be due to the lack of consensus on the method to be used in the measurement of TL [

23,

38] and the lack of cutoff value to define shortened TL. Further investigation is warranted to standardize TL as a clinical biomarker.

Our work has several limitations and strengths. First, our sample size is modest and different follow-ups in subgroups may have hampered drawing statistical conclusion. However, we tested assumptions for Cox regression and found no significant vulnerabilities. Second, the classification of patterns and final diagnosis of ILD is difficult, but the final classification was done within a multidisciplinary approach. Furthermore, we analysed tissue samples instead of leukocyte TL, which may more accurately reflect the telomere status of lung tissue.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results indicated a worse prognosis in IPF patients, especially in the ones with shortened TL. In a multivariate analysis, TL displayed a modifying role on the risk of death associated with the presence of RD. Furthermore, there was a link between higher inflammatory parameters and shorter TL in patients with IPF when concomitant RD was present.

Supplementary Materials

Protocol S1: Variable selection Cox regression model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Melchor Saiz-Pardo, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Formal analysis, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Melchor Saiz-Pardo and Pilar Iniesta; Funding acquisition, Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Investigation, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Jose-Ramón Jarabo, Joaquín Calatayud, Melchor Saiz-Pardo, Carlos-Alfredo Fraile, Florentino Hernando, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Methodology, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Jose-Ramón Jarabo, Joaquín Calatayud, Melchor Saiz-Pardo, Carlos-Alfredo Fraile, Florentino Hernando, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Project administration, Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Supervision, Asunción Nieto, Dolores Álvaro-Álvarez, María-Jesús Linares, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Validation, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Jose-Ramón Jarabo, Joaquín Calatayud, Melchor Saiz-Pardo, Asunción Nieto, Dolores Álvaro-Álvarez, María-Jesús Linares, Carlos-Alfredo Fraile, Florentino Hernando, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Writing – original draft, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez; Writing – review & editing, Sofía Tesolato, Juan Vicente-Valor, Jose-Ramón Jarabo, Joaquín Calatayud, Melchor Saiz-Pardo, Asunción Nieto, Dolores Álvaro-Álvarez, María-Jesús Linares, Carlos-Alfredo Fraile, Florentino Hernando, Pilar Iniesta and Ana-María Gómez-Martínez.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from “Neumomadrid” (Sociedad Madrileña de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica) (2019), and from “Cátedra EPID Futuro UAM-Roche” (2020). Funders did not partic ipate in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, nor preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the San Carlos Hospital (Madrid, Spain) C.I. 19/104-E_BS, 26/3/2019. Informed consents were obtained from patients prior to investigation assuring the confidentiality of their data.

References

- Cottin V, Hirani NA, Hotchkin DL, Nambiar AM, Ogura T, Otaola M, et al. Presentation, diagnosis and clinical course of the spectrum of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 21 de diciembre de 2018;27(150):180076. [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Mang C, Ringl H, Herold C. Interstitial Lung Diseases. Multislice CT. 24 de agosto de 2017;261-88. [CrossRef]

- Griese M. Etiologic Classification of Diffuse Parenchymal (Interstitial) Lung Diseases. J Clin Med. 21 de marzo de 2022;11(6):1747. [CrossRef]

- Wijsenbeek M, Suzuki A, Maher TM. Interstitial lung diseases. Lancet Lond Engl. 3 de septiembre de 2022;400(10354):769-86. [CrossRef]

- Podolanczuk AJ, Thomson CC, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Martinez FJ, Kolb M, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: state of the art for 2023. Eur Respir J. abril de 2023;61(4):2200957. [CrossRef]

- American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. febrero de 2000;161(2 Pt 1):646-64.

- Cottin V, Martinez FJ, Smith V, Walsh SLF. Multidisciplinary teams in the clinical care of fibrotic interstitial lung disease: current perspectives. Eur Respir Rev. 7 de septiembre de 2022;31(165):220003. [CrossRef]

- Gupta RS, Koteci A, Morgan A, George PM, Quint JK. Incidence and prevalence of interstitial lung diseases worldwide: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open Respir Res. 1 de junio de 2023;10(1):e001291. [CrossRef]

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1 de mayo de 2022;205(9):e18-47. [CrossRef]

- Riha RL, Duhig EE, Clarke BE, Steele RH, Slaughter RE, Zimmerman PV. Survival of patients with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1 de junio de 2002;19(6):1114-8. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım F, Türk M, Bitik B, Erbaş G, Köktürk N, Haznedaroğlu Ş, et al. Comparison of clinical courses and mortality of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial pneumonias and chronic fibrosing idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019;35(6):365-72. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Wang J. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Adv Respir Med. febrero de 2023;91(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Shay JW, Wright WE. Telomeres and telomerase: three decades of progress. Nat Rev Genet. mayo de 2019;20(5):299-309. [CrossRef]

- Hao LY, Armanios M, Strong MA, Karim B, Feldser DM, Huso D, et al. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell. 16 de diciembre de 2005;123(6):1121-31. [CrossRef]

- Alder JK, Barkauskas CE, Limjunyawong N, Stanley SE, Kembou F, Tuder RM, et al. Telomere dysfunction causes alveolar stem cell failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 21 de abril de 2015;112(16):5099-104. [CrossRef]

- Blin N, Stafford DW. A general method for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. septiembre de 1976;3(9):2303-8. [CrossRef]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 15 de mayo de 2002;30(10):e47. [CrossRef]

- Ksiazek K, Passos JF, Olijslagers S, Saretzki G, Martin-Ruiz C, von Zglinicki T. Premature senescence of mesothelial cells is associated with non-telomeric DNA damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 26 de octubre de 2007;362(3):707-11. [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1 de mayo de 2001;29(9):e45. [CrossRef]

- Budczies J, Klauschen F, Sinn BV, Győrffy B, Schmitt WD, Darb-Esfahani S, et al. Cutoff Finder: a comprehensive and straightforward Web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e51862. [CrossRef]

- Thompson ML. Selection of Variables in Multiple Regression: Part I. A Review and Evaluation. Int Stat Rev Rev Int Stat. 1978;46(1):1-19. [CrossRef]

- Alder JK, Chen JJL, Lancaster L, Danoff S, Su S chih, Cogan JD, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2 de septiembre de 2008;105(35):13051-6. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Molina M, Borie R. Clinical implications of telomere dysfunction in lung fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. septiembre de 2018;24(5):440-4. [CrossRef]

- Tomos I, Karakatsani A, Manali ED, Kottaridi C, Spathis A, Argentos S, et al. Telomere length across different UIP fibrotic-Interstitial Lung Diseases: a prospective Greek case-control study. Pulmonology. 1 de julio de 2022;28(4):254-61. [CrossRef]

- Stuart BD, Lee JS, Kozlitina J, Noth I, Devine MS, Glazer CS, et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an observational cohort study with independent validation. Lancet Respir Med. julio de 2014;2(7):557-65. [CrossRef]

- Dai J, Cai H, Li H, Zhuang Y, Min H, Wen Y, et al. Association between telomere length and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirol Carlton Vic. agosto de 2015;20(6):947-52. [CrossRef]

- Adegunsoye A, Newton CA, Oldham JM, Ley B, Lee CT, Linderholm AL, et al. Telomere length associates with chronological age and mortality across racially diverse pulmonary fibrosis cohorts. Nat Commun. 17 de marzo de 2023;14(1):1489. [CrossRef]

- Schneider CV, Schneider KM, Teumer A, Rudolph KL, Hartmann D, Rader DJ, et al. Association of Telomere Length With Risk of Disease and Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 1 de marzo de 2022;182(3):291-300. [CrossRef]

- Parra ER, Kairalla RA, Ribeiro de Carvalho CR, Eher E, Capelozzi VL. Inflammatory cell phenotyping of the pulmonary interstitium in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2007;74(2):159-69. [CrossRef]

- Khalil N, O’Connor R. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current understanding of the pathogenesis and the status of treatment. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 7 de julio de 2004;171(2):153. [CrossRef]

- Pathology of Usual Interstitial Pneumonia: Definition, Epidemiology, Etiology. 17 de octubre de 2021 [citado 18 de octubre de 2023]; Disponible en: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2078722-overview?&icd=login_success_email_match_fpf#showall.

- Armanios M. Telomerase and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mutat Res. 1 de febrero de 2012;730(1-2):52-8. [CrossRef]

- Daniil ZD, Papageorgiou E, Koutsokera A, Kostikas K, Kiropoulos T, Papaioannou AI, et al. Serum levels of oxidative stress as a marker of disease severity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21(1):26-31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Xu L, Cong YS. Telomere Dysfunction in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front Med. 11 de noviembre de 2021;8:739810. [CrossRef]

- McDonough JE, Martens DS, Tanabe N, Ahangari F, Verleden SE, Maes K, et al. A role for telomere length and chromosomal damage in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2018;19:132. [CrossRef]

- Cronkhite JT, Xing C, Raghu G, Chin KM, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, et al. Telomere Shortening in Familial and Sporadic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1 de octubre de 2008;178(7):729-37. [CrossRef]

- Newton CA, Batra K, Torrealba J, Kozlitina J, Glazer CS, Aravena C, et al. Telomere-related lung fibrosis is diagnostically heterogeneous but uniformly progressive. Eur Respir J. 1 de diciembre de 2016;48(6):1710-20. [CrossRef]

- Courtwright AM, El-Chemaly S. Telomeres in Interstitial Lung Disease: The Short and the Long of It. Ann Am Thorac Soc. febrero de 2019;16(2):175-81. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy C, Keane MP. Contemporary Concise Review 2021: Interstitial lung disease. Respirol Carlton Vic. julio de 2022;27(7):539-48. [CrossRef]

- Bowman WS, Echt GA, Oldham JM. Biomarkers in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease: Optimizing Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Response. Front Med. 10 de mayo de 2021;8:680997. [CrossRef]

- Karampitsakos T, Juan-Guardela BM, Tzouvelekis A, Herazo-Maya JD. Precision medicine advances in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. eBioMedicine. 1 de septiembre de 2023;95:104766. [CrossRef]

- Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, Webb WR, Ryu JH, Uden JHV, et al. Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 1 de junio de 2010;35(6):1322-8. [CrossRef]

- Kocheril SV, Appleton BE, Somers EC, Kazerooni EA, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, et al. Comparison of disease progression and mortality of connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Arthritis Rheum. 15 de agosto de 2005;53(4):549-57. [CrossRef]

- Utz JP, Ryu JH, Douglas WW, Hartman TE, Tazelaar HD, Myers JL, et al. High short-term mortality following lung biopsy for usual interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1 de febrero de 2001;17(2):175-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Nong W, Ji L, Zhuge X, Wei H, Luo M, et al. The regulatory feedback of inflammatory signaling and telomere/telomerase complex dysfunction in chronic inflammatory diseases. Exp Gerontol. 1 de abril de 2023;174:112132. [CrossRef]

- Wong JYY, Vivo ID, Lin X, Fang SC, Christiani DC. The Relationship between Inflammatory Biomarkers and Telomere Length in an Occupational Prospective Cohort Study. PLOS ONE. 27 de enero de 2014;9(1):e87348. [CrossRef]

- Jurk D, Wilson C, Passos JF, Oakley F, Correia-Melo C, Greaves L, et al. Chronic inflammation induces telomere dysfunction and accelerates ageing in mice. Nat Commun. 24 de junio de 2014;5(1):4172. [CrossRef]

- Newton CA, Zhang D, Oldham JM, Kozlitina J, Ma SF, Martinez FJ, et al. Telomere Length and Use of Immunosuppressive Medications in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1 de agosto de 2019;200(3):336-47. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).