1. Introduction

Glycosylation is a common post-translational modification (PTM) in proteins, influencing protein folding [

1] and targeting (both intracellular and extracellular targeting [

2]. This has a profound influence on the quality and titer of IgGs manufactured in the pharmaceutical industry. Additionally, glycosylation affects peptide-MHC binding [

3], and Fc receptor interactions [

4]. Therefore, the glycosylation of biopharmaceutical drugs affect its safety and efficacy – by affecting it’s in vivo half-life [

5], immunogenicity [

6] and effector functions [

7]. A recent survey of the top 20 best-selling IgG drugs shows that more than half of them were glycoproteins (either monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or Fc-based fusion proteins [

8].

Most therapeutic antibodies belong to the IgG1 subclass. The mechanism of action often comprises antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) which requires interactions mediated by the Fc region of the IgG1. While the Fab domain of different monoclonal antibodies are structurally diverse in order to recognize different antigens, the Fc region is relatively well conserved and lacks the structural diversity of the Fab domain. After the Fab domain has bound to the antigen, the Fc domain determines the function/mechanism by which the monoclonal antibody will act. For example, it may recruit molecules of innate immune system (complements) or bind to antigen presenting cells (APCs) by binding to Fcγ receptors [

12]. Interestingly, the Fc region of IgG1 has two conserved

N-glycosylation sites at Asn297 (one each in the two CH

2 domains of each heavy chains) [

12,

13]. Therefore, variability in glycan architecture affects how IgG interacts with the immune system, and therefore the downstream function/efficacy as well.

One of the major reasons for glycan variability is that in contrast to proteins, the biosynthesis of glycans is not solely derived from the plasmid template, but also depends on other factors like genetic make-up of the cells (cell-lines) in which the glycoproteins are expressed [

9] including epigenetics [

10] and the extracellular environment (cell culture) [

11].

As a result, glyco-biologics (biopharmaceutical drugs which are glycosylated) often have a heterogeneous profile for glycans. This profile is heavily dependent on specific host cell line (HEK vs CHO) and the upstream cell culture process. Additionally, the downstream purification process (more specifically, the modes of chromatography used in the purification process) may alter the glycan profile of the final enriched, purified species.

Therefore, regulatory agencies require glycan profiles to be consistent for different batches of the drug. This is critical as glycan profiles affect the safety and efficacy of a drug. Hence, FDA has suggested a QbD (Quality by Design) approach to monitor glycosylation as far as the Critical Process Parameters (CPP) for Drug Substance Manufacture and Target Product Profile (of Drug Product) is concerned. Thus, the process design (upstream/downstream) needs to identify the CPPs for maintaining the optimal glycan profile. QbD requires an appreciation of historical data, design of experiments (DoE), process analytical technology (PAT) and concomitant risk assessments.

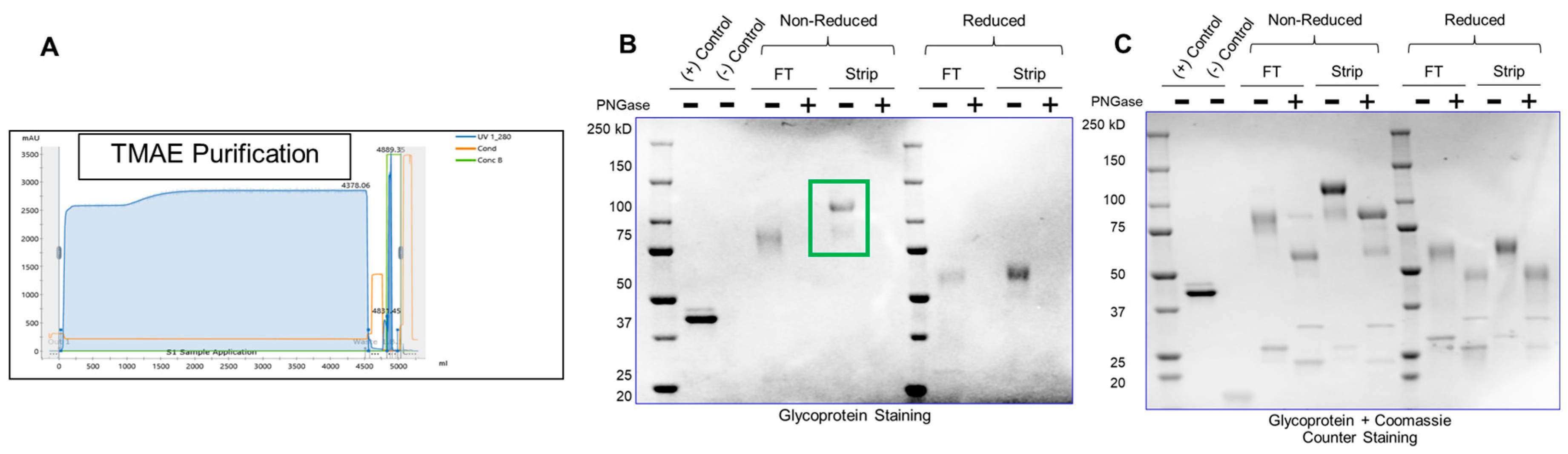

All IgGs including glycoproteins need to be purified; additionally, glycoproteins need the glycan architecture to be monitored through the process as that has a profound effect on potency. Generally, the proteins are captured by a Protein A step followed by other polishing steps [

14]. Such additional polishing steps consists of ion-exchange and hydrophobic interaction chromatography – these modalities are used to remove process impurities like endotoxins, host cell proteins (HCP) and residual DNA [

15]. This is followed by non-chromatographic steps to concentrate the IgG – such as ultrafiltration and diafiltration (UFDF). A population of glycans will behave bind to an anion-exchange column or hydrophobic column (based on charge or hydrophobicity), and the heterogeneity of the purified pool will depend on the specific elution condition. As a result, pharmaceutical manufacturers need to analyze the glycan profile throughout process development and manufacturing.

This diversity coupled with the nonlinear structures of glycans gives their physicochemical characterization an added layer of complexity. Additionally, an oligosaccharide can be “

N-linked” or “

O-linked” depending on whether the carbohydrate is attached through the amide group of an asparagine residue (“

N-linked”) or the hydroxyl group of a serine/threonine residue in an IgG “

O-linked”. Therefore, multiple analytical techniques are used to understand IgG glycosylation. Generally speaking, the analysis can be carried out at three distinct levels [

16], depending on the specific question to be answered. These levels include the intact protein level, glycopeptide level, or with released glycans.

At the intact protein level, one can use chromatography, gel electrophoresis or mass-spectrometry. At an intact level, a top-down approach can be used to analyze intact protein samples with minimal sample preparation in order to obtain molecular weight and PTMs like glycosylation. It can be used to gauge variability between different batches. However, an intact top-down approach is limited in detecting the nuances of minor glycoforms. Therefore, middle-down strategies, coupled with chemical and enzymatic approaches can be used to analyze different antibody subunits. This approach using reducing agents to reduce inter-chain disulfide bonds and specific protease (like IdeS) is often utilized to detect and identify multiple glycoforms and other PTMs [

17].

Additionally, glycopeptide analysis is carried out to comprehend glycosylation microheterogeneity using a bottom-up approach. Here, the therapeutic biologic is treated with proteolytic enzymes (trypsin) and then analyzed with LC/MS or CE [

18]. Such methods are used for monitoring variability between different manufacturing batches or process development. Finally, the identity of the monosaccharide composition, the specific glycosidic linkage – of which is critical to safety/efficacy of the therapeutic can be characterized in-depth by HPLC/UPLC coupled with MS [

16]. A major technical challenge is the lack of a chromophore in the monosaccharide augmented by the different configurations of the glycan. To circumvent this, released glycans are fluorescently labelled for optimal detection [

19]. Capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence (CE-LIF) has also been used for glycans analysis (where the released N-glycans are labelled with 8-aminopyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonate). In this case, the labelled glycans are resolved using charge/hydrodynamic-volume ratio [

20]. CE-LIF can also be coupled with HPLC/UPLC in a 2D format.

The gold standard to interrogate glycosylation is MS as it has the best resolution. The most common ionization methods for analyzing glycosylation are ESI and MALDI. However, a common challenge to most methods is the complexity introduced by the enzymatic digestion of glycosylated biologics. This may lead to competitive ion suppression (analyzing glycopeptides vs peptides) during mass-spectrometric analysis. Additionally, it may not be practically feasible to engage the MS team during different phases of downstream purification. Engaging a MS team may be time consuming and often a MS team may be geographically distant from the downstream team, requiring samples to be shipped which may lead to temperature excursions, etc.

A highly desired kit in a downstream purification team’s toolbox is a seamless method to detect, monitor and quantitate glycans in real-time. This will be critical to guide both downstream purification and upstream expression studies. This is especially important as glycans are increasingly being shown to be critical for a growing number of therapeutic assets – and understanding glycan content is central to interrogating batch-to-batch variability. Additionally, a common downstream purification chromatographic technique is ion-exchange, and this is known to influence glycan content – thus, a quick tool to monitor glycan activity is helpful in a downstream team.

Currently, most downstream teams analyze glycan content following enzymatic digestion with PNGase (which removes N-linked glycosylation) – the proteins are subsequently resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel and the mobility shift (faster migrating band upon glycan truncation) confirms the presence of a glycosylated species. This is the assay used as purification guide to quickly identify glycosylated species. However, the assay is not quantitative. Additionally, this is an indirect enzymatic measurement and assumes that PNGase will be active for all immunoglobulins.

It is easy to appreciate that an ideal glycosylation-staining method should selectively stain the sugar, without staining the protein on an SDS-PAGE gel. The greatest challenge in the field has been the inability to have a dye that selectively stains sugar – a “Coomassie for carbohydrates”. The primary reason for this is that amino acids (serine/threonine/tyrosine) have primary-hydroxyl groups just like sugars; thus, selectively staining sugar moieties in their native hydroxyl form is challenging.

We have developed a method (henceforth referred to as ‘GlycoIg-stain’) where we can selectively oxidize the primary-alcohol groups in sugars to their aldehyde form using periodic acid. Our method leaves the primary alcohol in the amino acids intact. The reason behind this selectivity is that we leverage the stereochemistry of the alcohols by selectively oxidizing the cis-diol in glycoproteins to aldehyde in situ on the SDS-PAGE gel. The oxidation process we use is selective and requires two proximal hydroxyl groups to be in a ‘cis’ position. The aldehyde is then detected by Schiff’s reaction and the glycosylated IgG appears as a magenta band on the SDS-PAGE gel (graphical abstract). IgGs which are not glycosylated will not be stained by this method. The SDS-PAGE gel can then be counterstained with Coomassie (per regular protocol) to stain both glycosylated and non-glycosylated IgG.

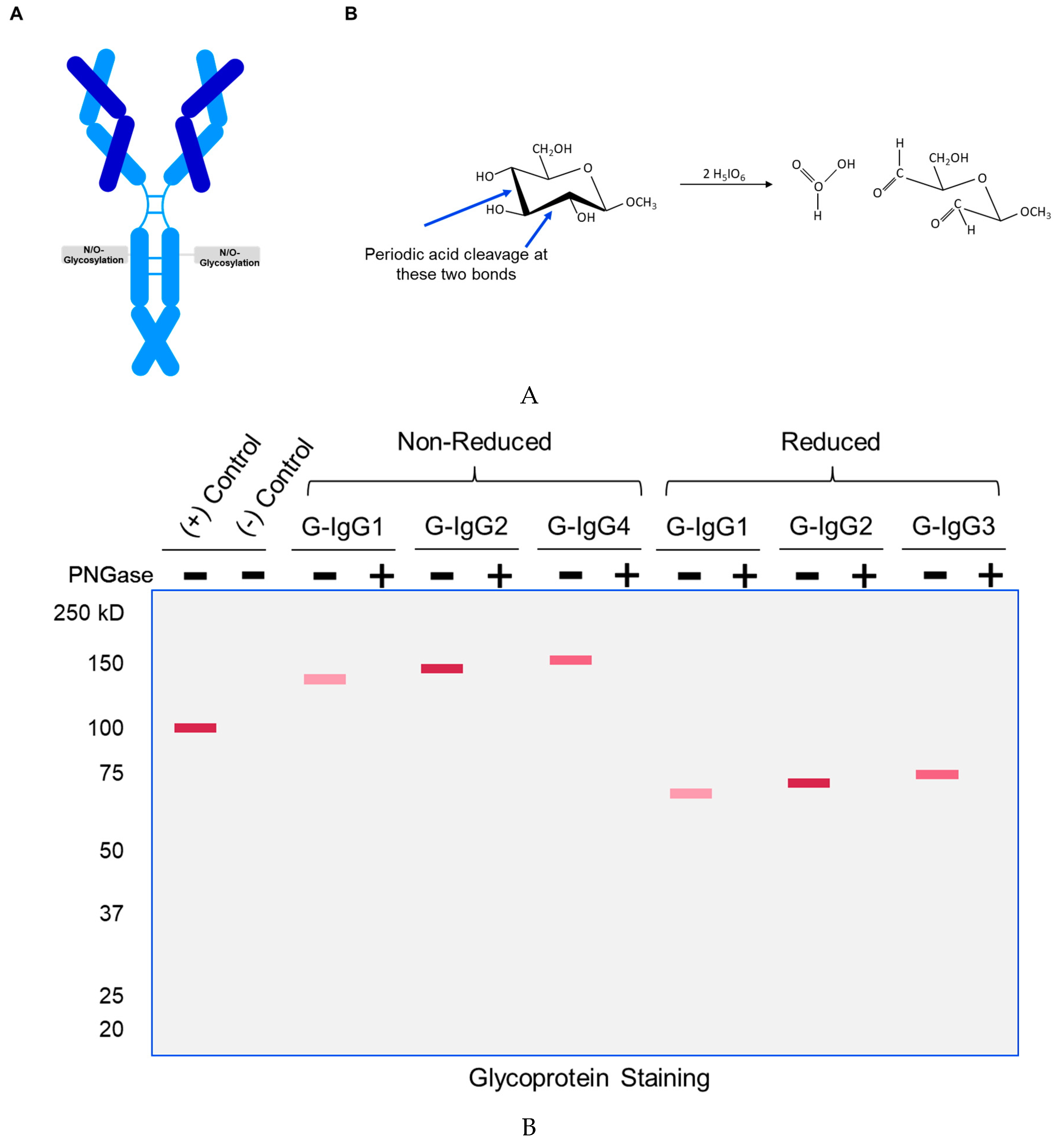

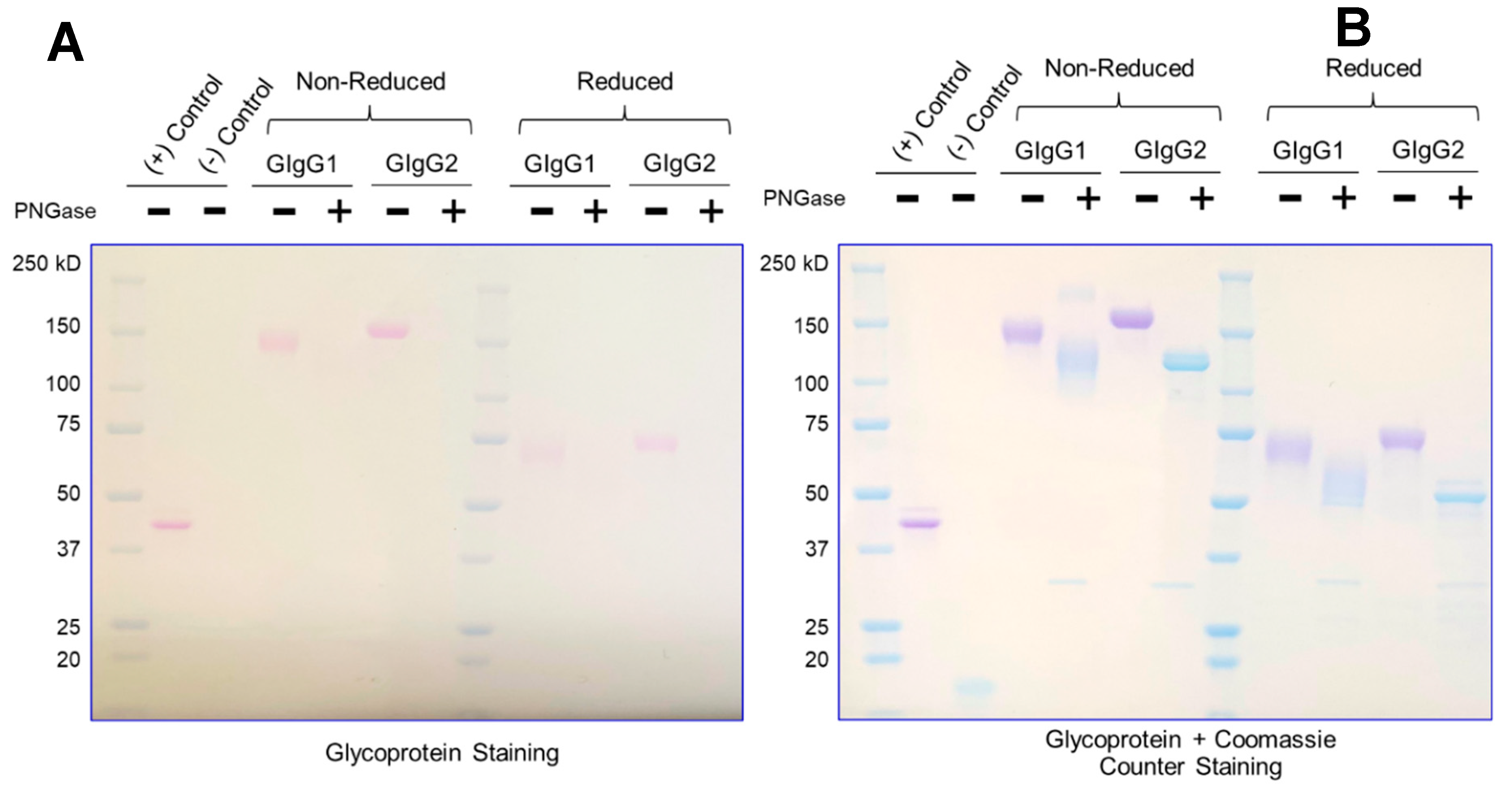

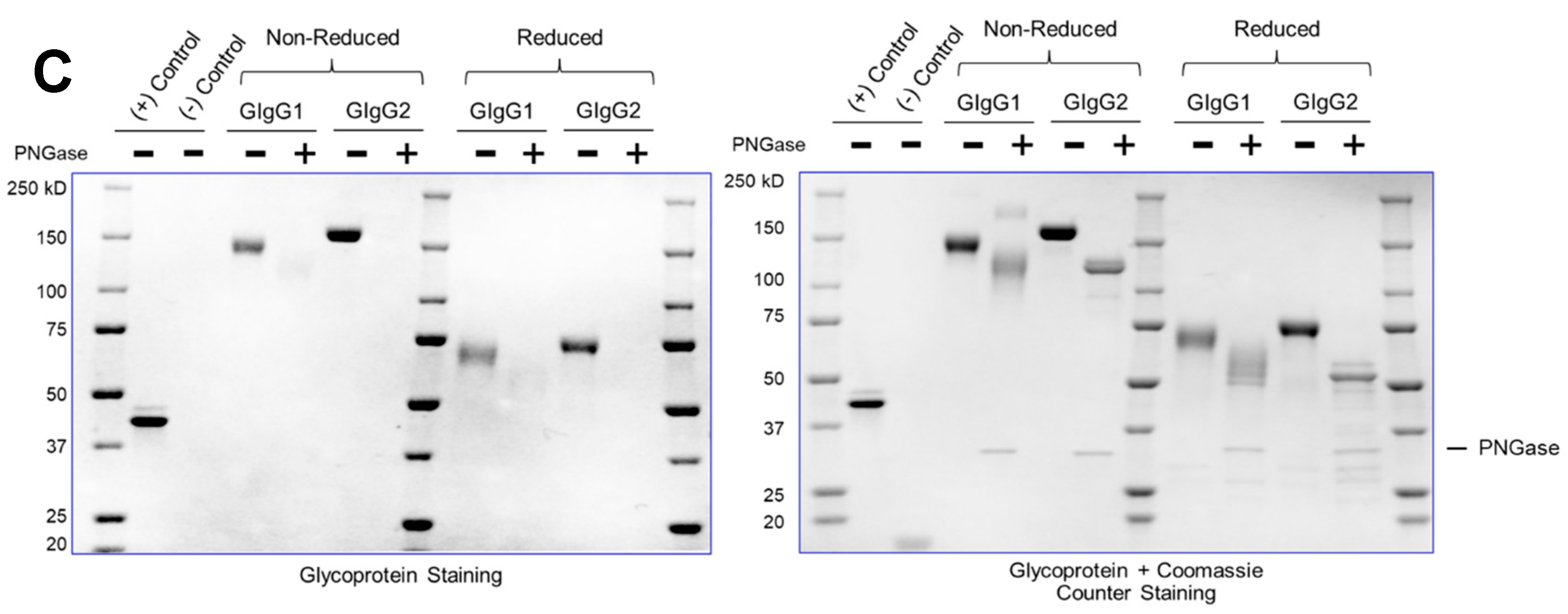

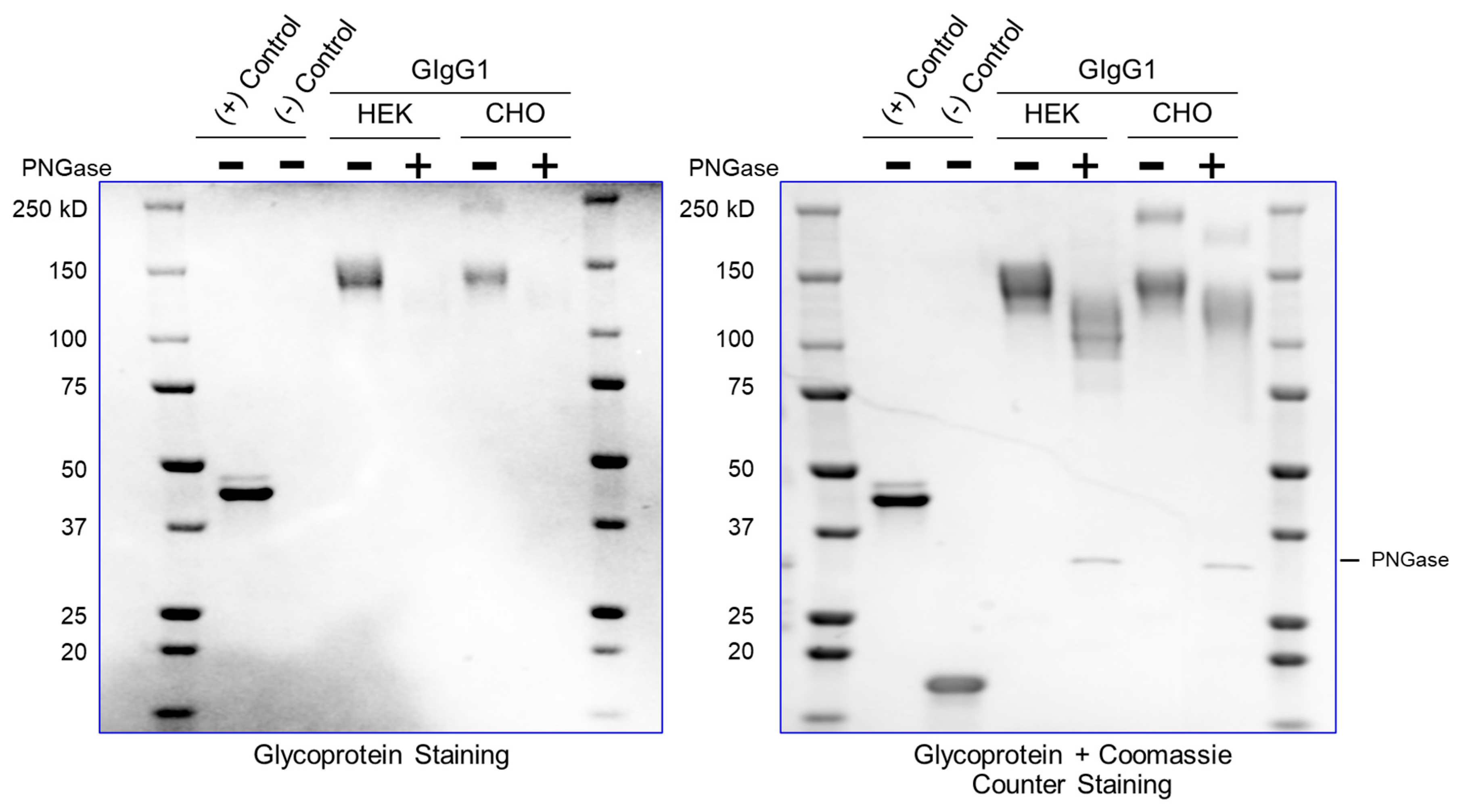

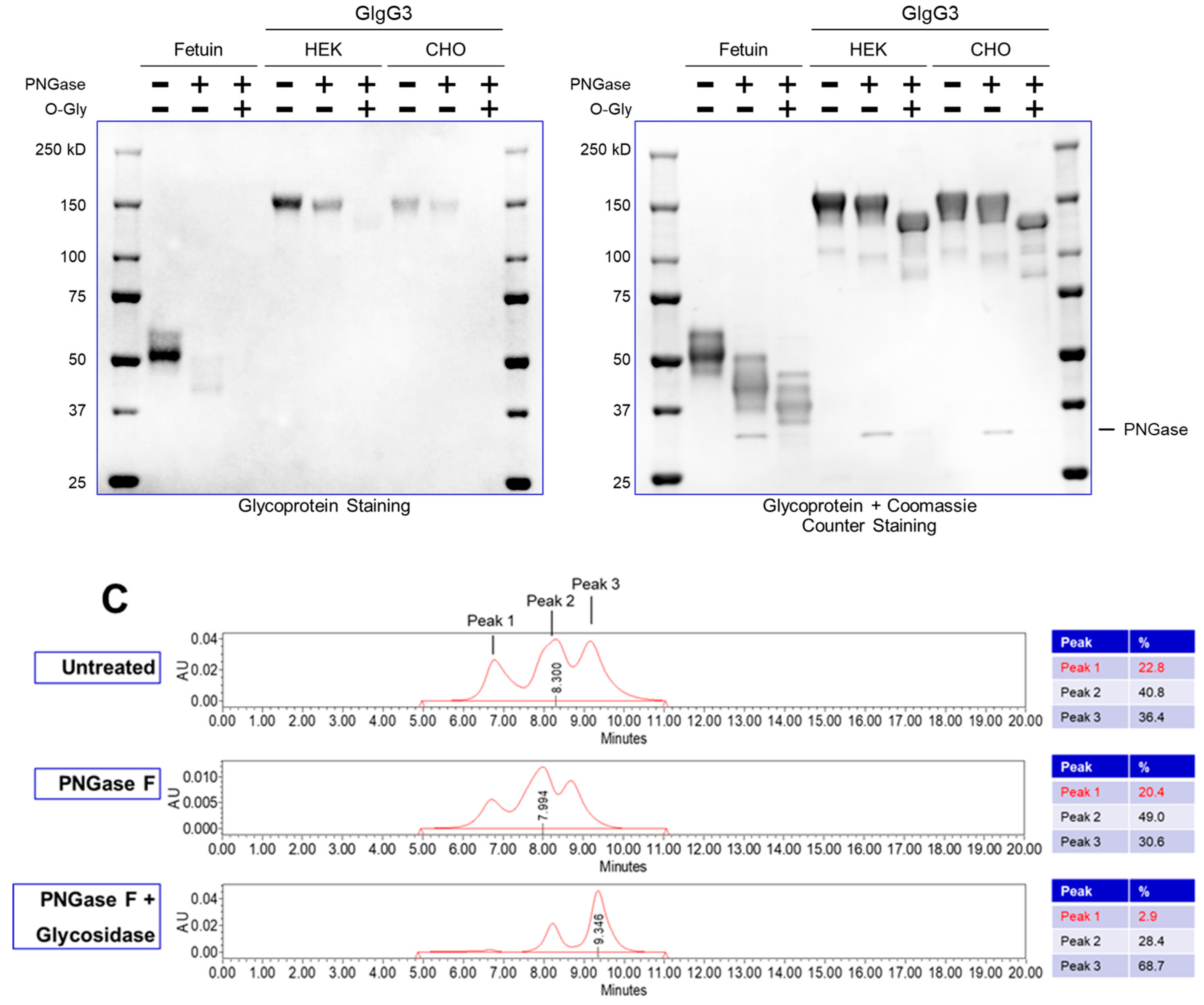

The mechanism for the ‘GlycoIg-stain’ is shown in

Figure 1A. The carbohydrates in the CH2 domain are selectively oxidized to aldehydes

in situ on an SDS-PAGE gel. These aldehydes can then be visualized using Schiff reaction. A pictorial representation of the expected magenta bands for the glycosylated IgGs is depicted in

Figure 1B (the magenta bands disappear upon treatment with PNGase (enzyme that removes N-linked glycosylation).

Our protocol is rapid and semi-quantitative. It can detect both N-linked and O-linked glycosylation. Finally, the ability to stain a single SDS-PAGE gel with the ‘GlycoIg-stain’ followed by the Coomassie (may also serve as protein loading control) enables streamlining with existing protocol to enable facile adoption in any laboratory.

The immunoglobulins, their sizes, isoelectric point, cell lines where they were expressed along with their modes of expression and glycosylation-linkage is designated in

Table 1. “G-IgG” refers to “glycosylated imynoglobulin”.

3. Discussion

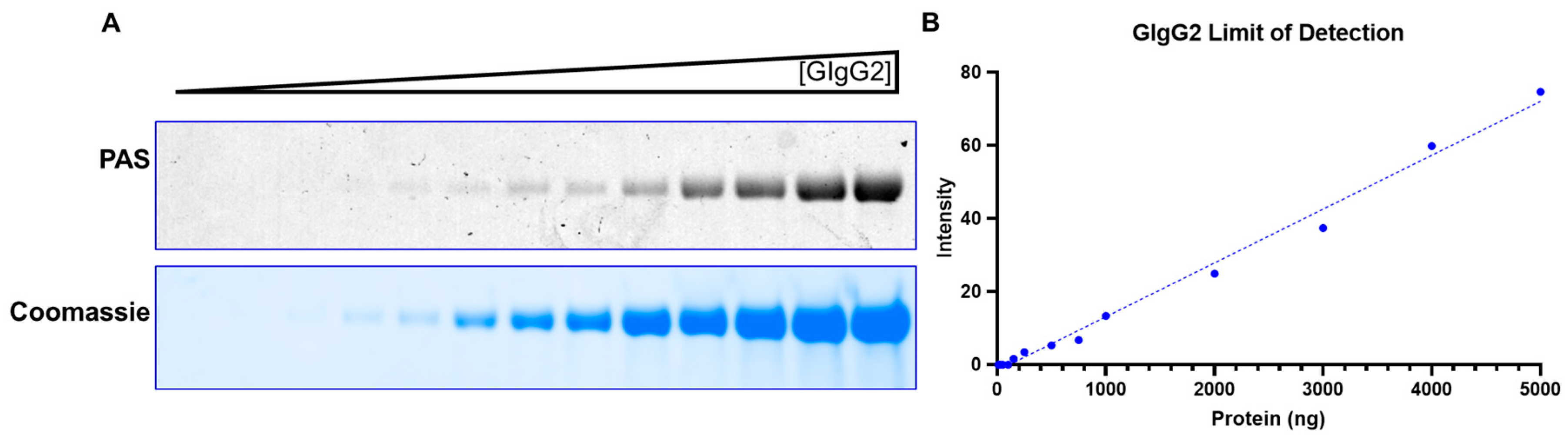

We have developed a protocol which involves resolving the samples on an SDS-PAGE gel, followed by staining the gel with “GlycoIg stain” to detect glycoproteins, enabling the QbD paradigm in a seamless, cost-effective manner. It can quickly determine if a protein is glycosylated leveraging the Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) reaction to specifically detect glycosylated IgGs with oxidizable carbohydrate groups. The PAS reaction uses periodic acid to oxidize the two cis-diol groups to an aldehyde in-situ on the gel. The gel aldehyde is subsequently treated with Schiff reagent which gives a magenta band for the glycosylated protein against a faint-pink background [

36].

The method takes less than two hours, and the same SDS-PAGE gel can be sequentially stained for glycosylation and Coomassie respectively, thereby obviating the need to run multiple gels. This facilitates streamlining with routine SDS-PAGE protocols to enable facile adoption. Additionally, this makes the protocol fast, convenient, and cost-effective. The method is semi-quantitative, sensitive (~100ng) and can detect both N-linked and O-linked glycosylation. We also noted that we could derive critical insights by using the “GlycoIg-stain” which we would otherwise have been challenging. For example, the “GlycoIg-stain” helped us to differentiate that the clipped species were aglycosylated whereas the intact molecule was glycosylated. This information could be important in reevaluating the sequence design or the cell culture conditions.

We added an alkylating agent to the samples to prevent SDS-PAGE artifacts - which may be especially more pronounced for immunoglobulins given the enhanced propensity for disulfide scrambling and resulting fragmentation [

34,

35,

36]. However, our method is compatible with sample preparation without the addition of alkylating agents.

We feel that the method can also be extended to stain on nitrocellulose membranes and may be coupled with western blotting. However, one potential drawback of the method is that the staining intensity may potentially be lower for IgGs with fewer glycosylation sites or “sparse” glycan trees than the “heavily” glycosylated immunoglobulins.

Finally, our method may also find use for developing biosimilars which are increasingly becoming important because of the ‘patent cliff’ for original drugs. A comparability analysis for biosimilars is critical to regulatory approval [40]. The FDA [41], WHO [

21], and European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidelines [42] all require a detailed study of the glycosylation patterns and emphasizes a QbD comparison with the original drug where possible.

5. Conclusion

Since the glycosylation profile and diversity can be affected by subtle changes upstream and chromatographic processes downstream, it is imperative to develop a tool that can be integrated with common biochemistry protocols to study both glycosylated and aglycosylated immunoglobulins. We have demonstrated a novel methodology that selectively stains glycosylated immunoglobulins, but not aglycosylated IgGs on an SDS-PAGE gel. The staining of glycoproteins is enabled by selective in situ oxidation of cis-diol groups on the carbohydrate (and not alcohol groups of the amino acids) to aldehyde directly on the polyacrylamide gel. This selective oxidation is carried out by incubating the polyacrylamide gel in periodic acid. These aldehydes are then detected by Schiff reaction and appears as magenta bands of the SDS-PAGE gel.

An experimentally determined glycosylation level is one of the several CQAs that must be specified to regulatory agencies as this has been shown to affect safety and efficacy of IgG therapeutics. The ability to control and analyze glycosylation levels needs to be demonstrated to regulatory agencies before approval. Indeed, both WHO [

21]and International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Q6B [

22] require pharmaceutical companies to identify and characterize most PTMs including glycosylation. Thus, the monitoring and characterization of glycans through the development process is an essential part of any successful QC (quality control) endeavor.

The QC challenges are accentuated by the fact that there are two types of glycosylation,

N-linked and

O-linked. An immunoglobulin can be glycosylated by one or more linkages. Both these types of glycosylation affect protein conformation, folding, processing and secretion (endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus), degradation and biological activity [

23]. Indeed, anomalous glycosylation has been linked with various kinds of diseases, including neurodegenerative [

23], congenital [

25], various autoimmune diseases [

12], and cancer [

26]. Additionally, they affect protein purity and titer – important from a cost of goods (COGS) perspective for pharmaceutical companies

An oligosaccharide is “

N-linked” through the amide group of an asparagine residue located in a consensus NXS/T sequence (X can be any amino acid except proline). Unlike O-glycosylation,

N-glycosylation is unique to proteins that are secreted [

25]. Interestingly, the assembly of

N-glycans commences as a Glc

3Man

9GlcNAc

2 in the ER, but is transferred to the Golgi only if the protein folds correctly – as a Man

8GlcNAc

2 [

28]. In the Golgi, the glycosylation can continue as a high-mannose or some glycans may be interchanged to form a hybrid “tree-like” bi, tri, or a quaternary structure.

An oligosaccharide is “

O-linked” through the hydroxyl group of a serine/threonine residue in an IgG. However, unlike

N-linked glycosylation,

O-linked glycosylation does not have a consensus site [

29]. The common O-linked glycosylations are

O-acetylgalactosamine (

O-GalNAc), linked via an α-linkage of an O-glycosidic bond. Another O-linked glycosylation is the

O-acetylglucosamine (

O-GlcNAc), which is linked through

β-linkage of an O-glycosidic bond. The most common

O-GlcNAc are mucins. O-glycosylation variations can be quite diverse with monosaccharides and/or oligosaccharides. Multiple immunological diseases can be caused by mucin O-glycan aberrations [

30].

Monitoring this diversity in N-linked and O-linked glycosylation can be challenging. For this, the regulator agencies recommend a QbD approach to integrate our findings at each step of the development process. QbD is at its core a conceptual framework that is to be adopted through development into manufacturing such that product quality can be built into the process – however, this needs immaculate analytical processes to monitor glycosylation at every stage [

31]. To implement a QbD framework, the optimal target product profile (TPP) of the biotherapeutic which is appropriate for clinical efficacy needs to be established. Following this, the critical process parameters (CPPs) that may affect the TPP and the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the drug can be studied thoroughly [

32]. The CPPs need to be studied in real-time (if possible) by process analytical technology (PAT) to ensure appropriate drug attributes [

33].

It is appreciated that implementing QbD for biologics is generally a greater challenge than small molecules given the general complexity of biotherapeutics [

33]. A simple gel-based monitoring method which can be run in a basic biochemistry lab would be a big step ahead towards this QbD paradigm as it would allow a near real-time assessment of glycosylation parameters.

Two such techniques, alcian blue gel and Stains-All gel [

32,

33] were developed for staining proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and negatively charged glycoproteins. However, these were non-specific and stained all negatively charged proteins including phosphoproteins. Thus, they could not be adopted to study glycosylation. Another common method is to study the mobility shift post enzymatic digestion with PNGase F (PNGase F is an enzyme that removed N-linked glycans). PNGase F is widely used in the industry as it has the broadest specificity and can completely remove the sugar chains without protein degradation. Other enzymes are more specific with regards to the type of N-glycan they cleave. However, this method is not quantitative and perhaps more importantly, it is an indirect method that relies on how amenable the glycoprotein is to the enzymatic digestion. A comparison of this common enzymatic method with the method we developed is demonstrated in

Table 2.