Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

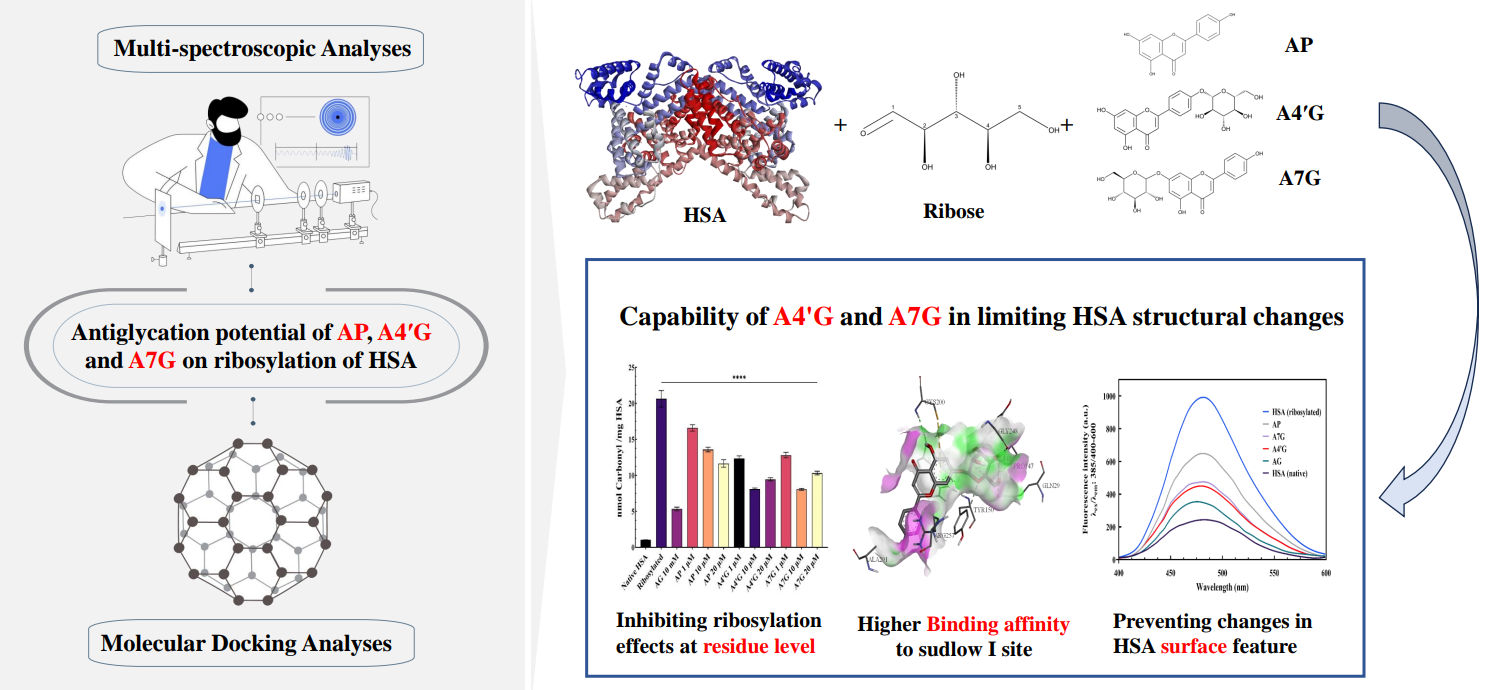

Abstract

Keywords:

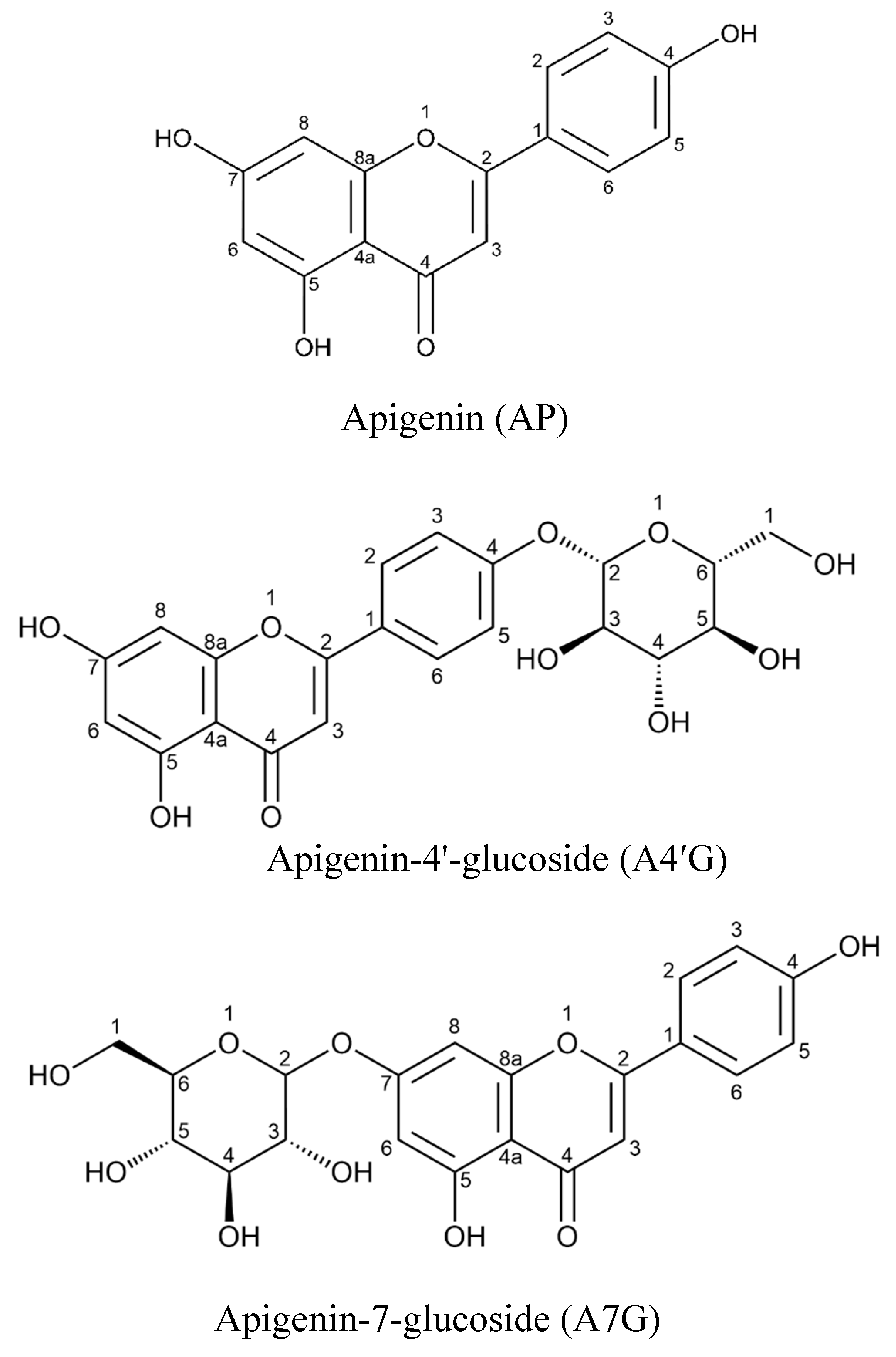

Introduction

Results and Discussion

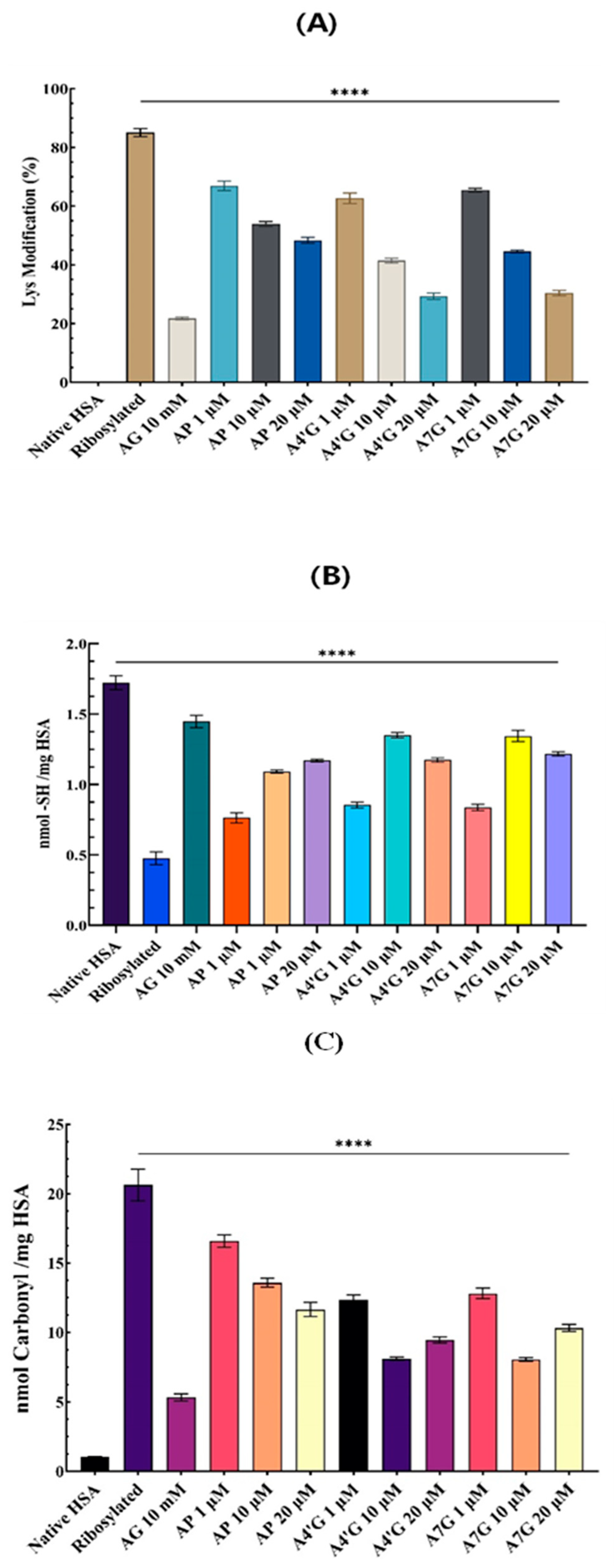

Ribosylation Effect at Residue Level

Ribosylation Alters the HSA Surface Feature

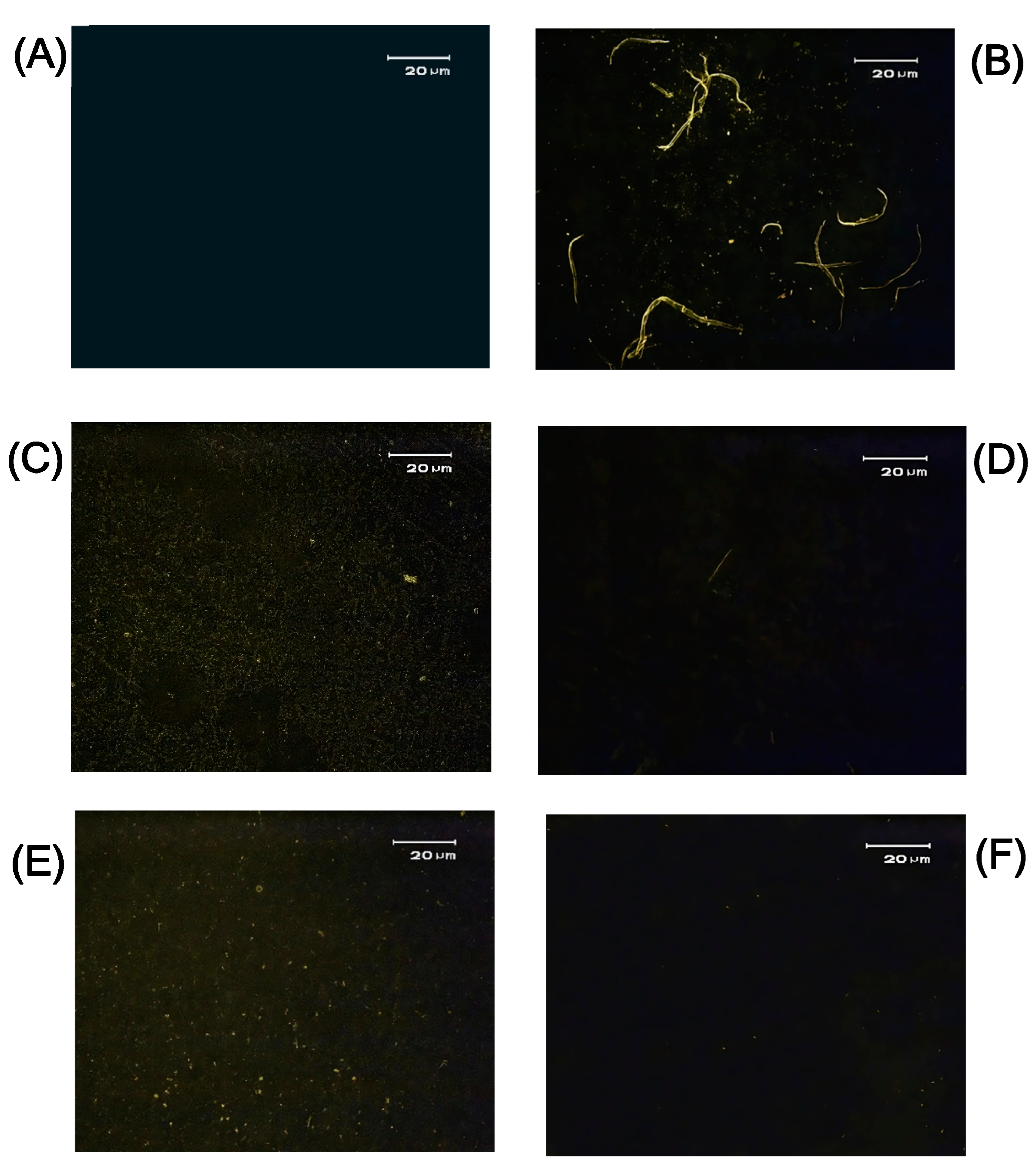

Ribosylation Drives Cross-β Structure Formation

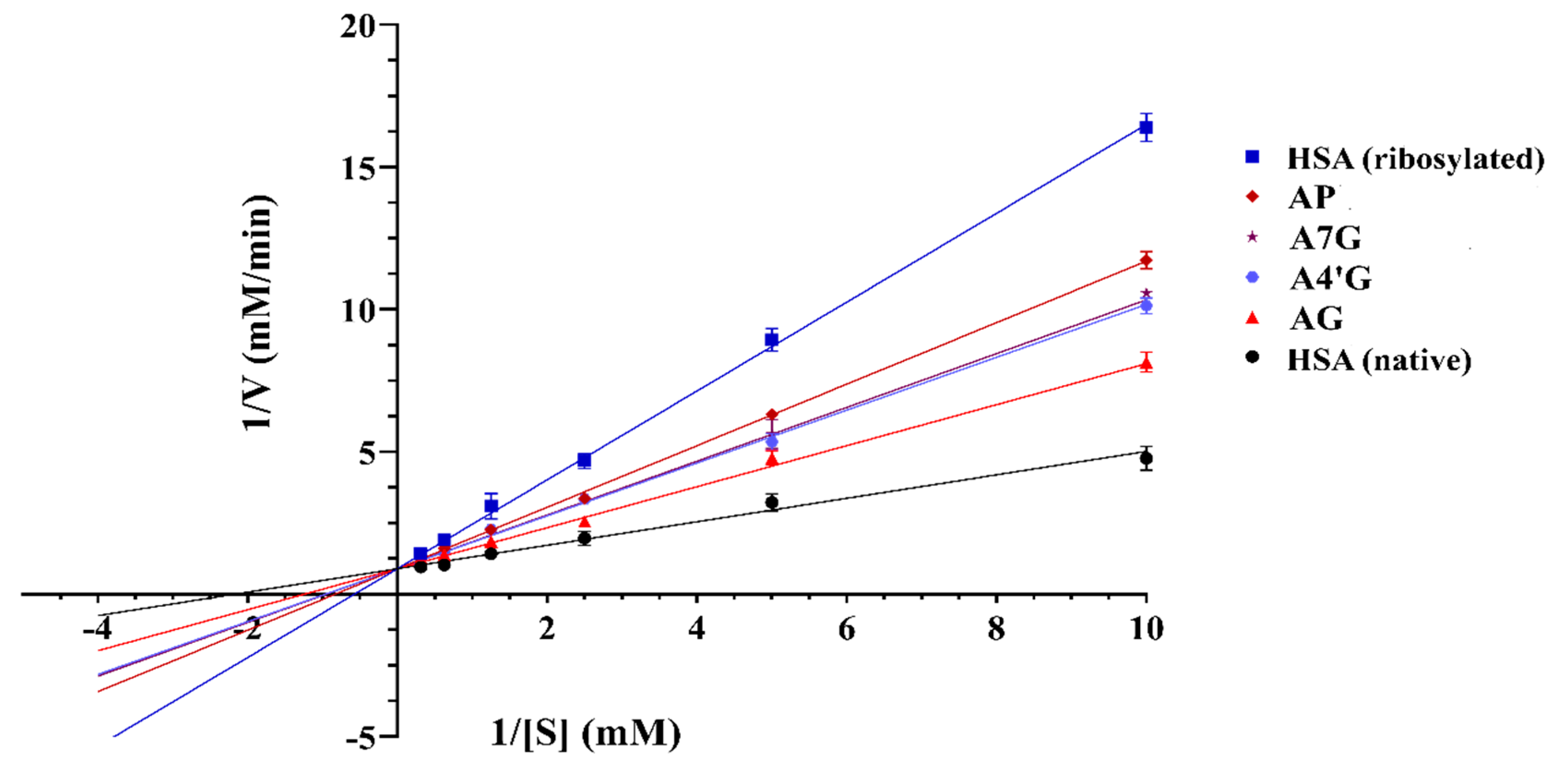

HSA Esterase-like Activity

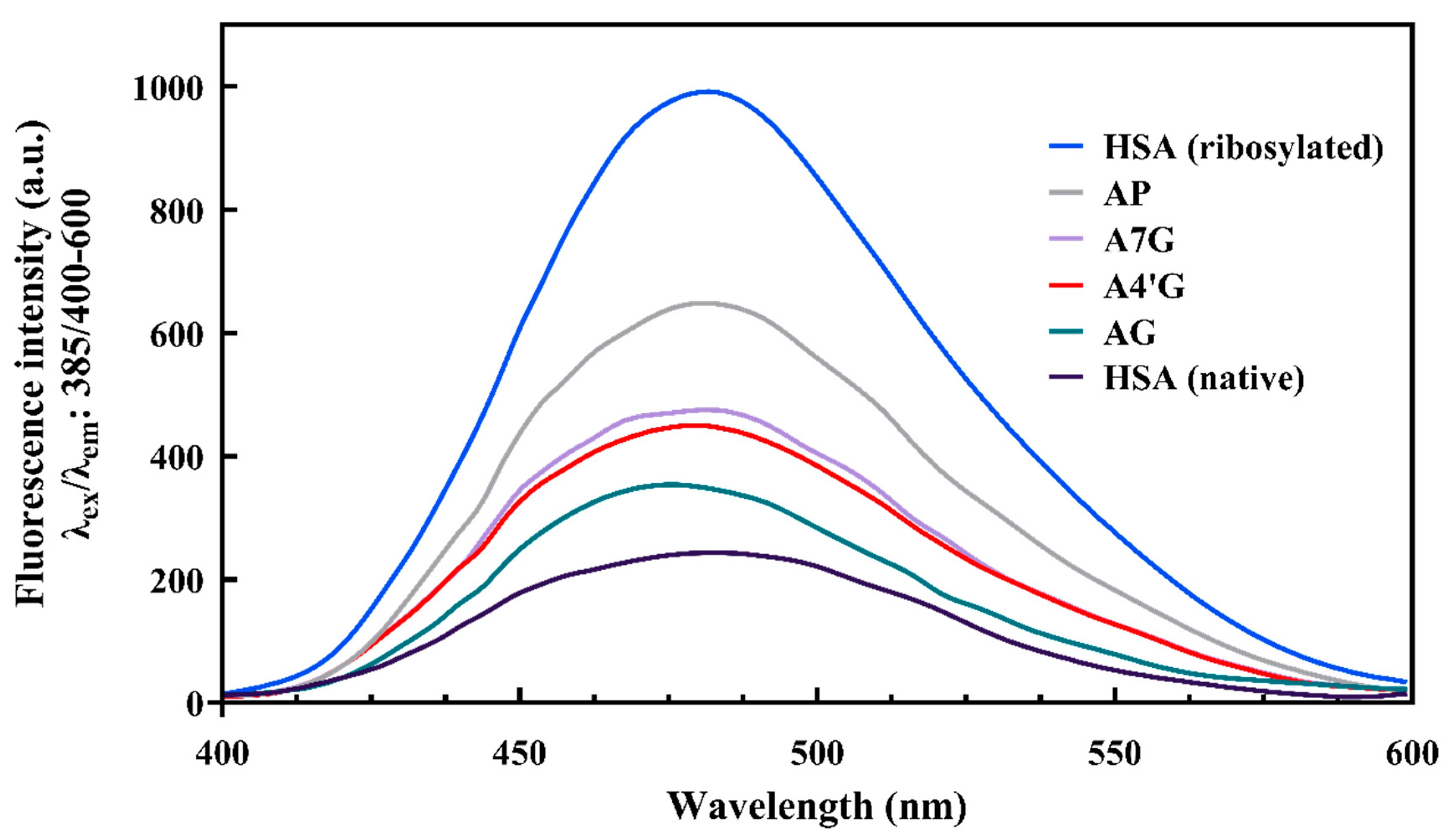

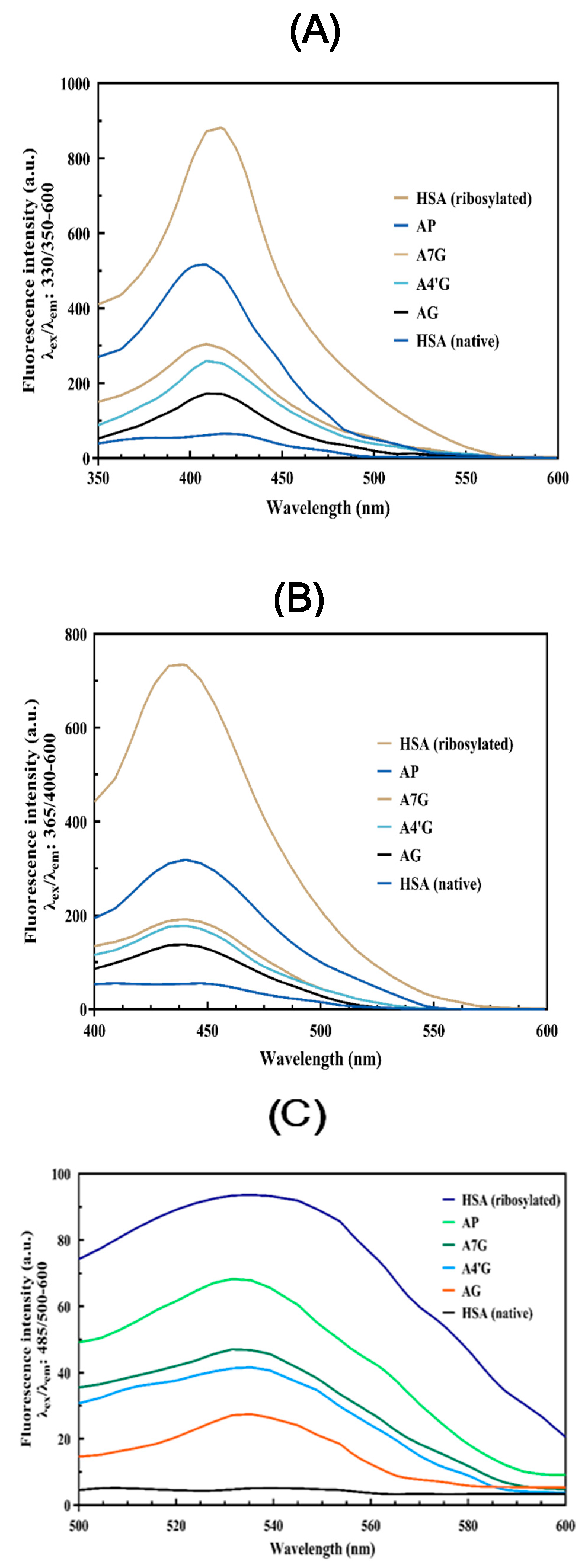

AGEs Fluorescence Measurement

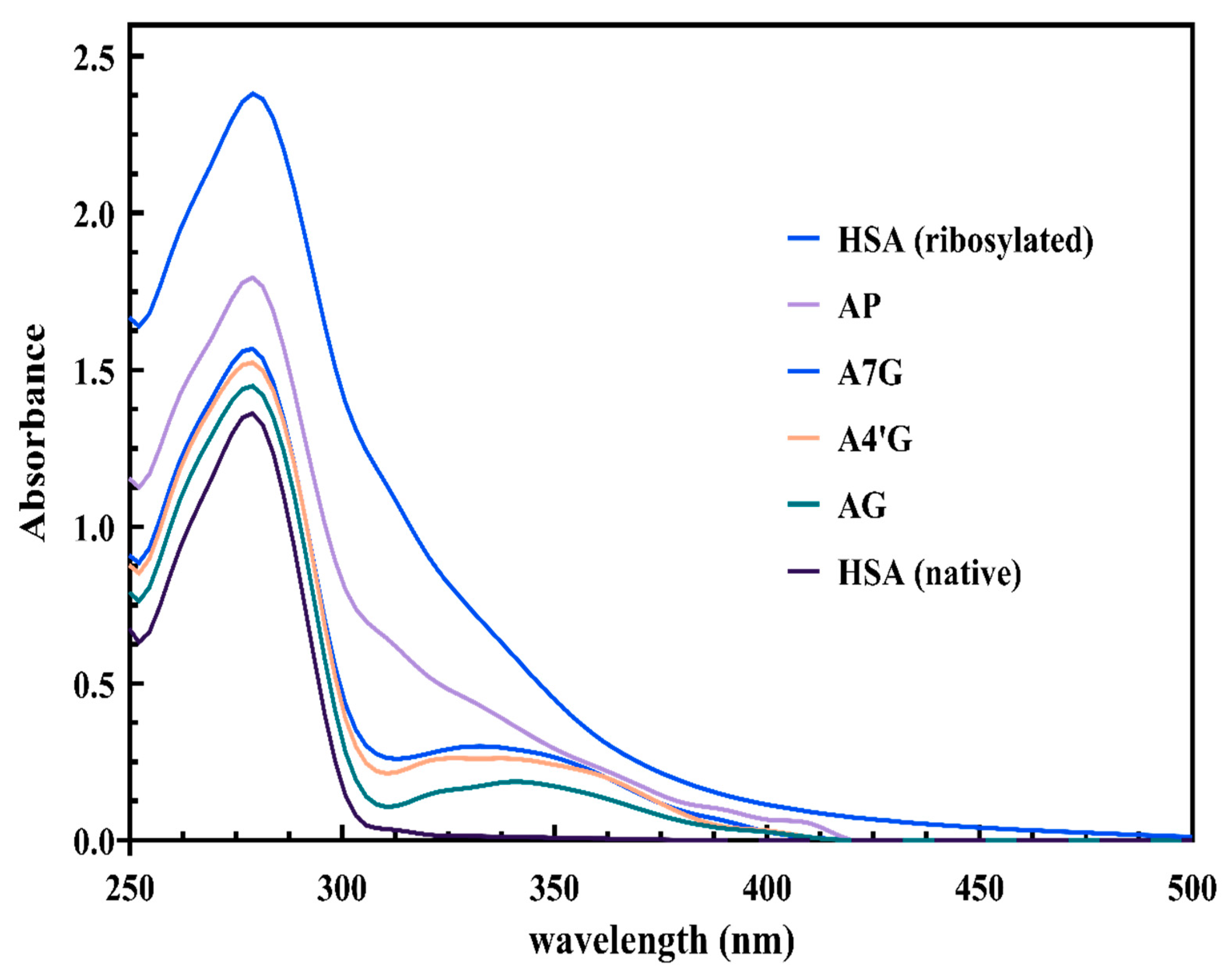

UV–Visible Spectroscopy

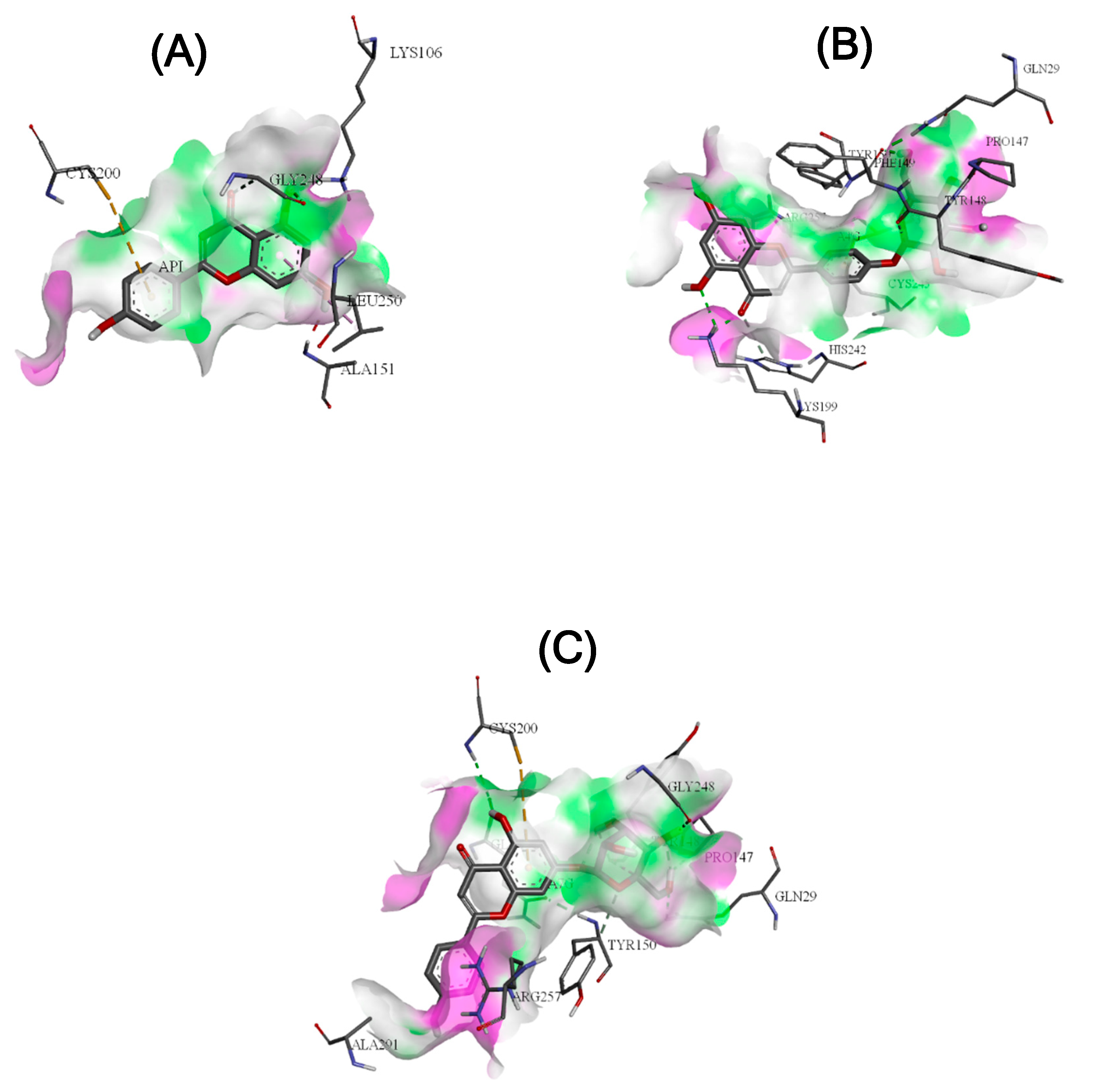

Molecular Docking Approach

Material and Methods

Chemicals

In-Vitro Glycation of HSA

UV-Visible Spectroscopy

AGE Fluorescence Measurements

ANS Binding Assay

Carbonyl Content Measurement

Primary Amino Group Measurement

Thiol Group Measurement

HSA Esterase-like Activity

Fluorescence Microscopy

Molecular Docking Analysis

Statistics

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Qais, F.A.; Alam, M.M.; Naseem, I.; Ahmad, I. Understanding the mechanism of non-enzymatic glycation inhibition by cinnamic acid: an in vitro interaction and molecular modelling study. RSC advances 2016, 6, 65322–65337. [Google Scholar]

- Koerich, S.; Parreira, G.M.; de Almeida, D.L.; Vieira, R.P.; de Oliveira, A.C.P. Receptors for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE): promising targets aiming at the treatment of neurodegenerative conditions. Current Neuropharmacology 2023, 21, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, J.V.; Weldon, S.C.; Quinn, D.; Kiers, G.H.; DeGroot, J.; TeKoppele, J.M.; Hughes, T.E. Advanced glycation end product ligands for the receptor for advanced glycation end products: biochemical characterization and formation kinetics. Analytical biochemistry 2004, 324, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi, P.; Leboffe, L.; di Masi, A.; Trezza, V.; Fanali, G.; Gioia, M.; Coletta, M.; Fasano, M. Ligand binding to the FA3-FA4 cleft inhibits the esterase-like activity of human serum albumin. PloS one 2015, 10, e0120603. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, G.; Ahn, S.N. Structure, enzymatic activities, glycation and therapeutic potential of human serum albumin: A natural cargo. International journal of biological macromolecules 2019, 123, 979–990. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadpour, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Miroliaei, M. Role of Structural Peculiarities of Flavonoids in Suppressing AGEs Generated From HSA/Glucose System. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, K.; Qais, F.A.; Ahmad, I.; Naseem, I. Inhibitory effect of vitamin B3 against glycation and reactive oxygen species production in HSA: An in vitro approach. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2017, 627, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar, A.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A.; Sattarahmady, N.; Hosseinpour-Faizi, M.A.; Aminbakhsh, M.; Ahmad, F.; Saboury, A.A.; Ganjali, M.R.; Norouzi, P. Spectroscopic studies of the effects of glycation of human serum albumin on L-Trp binding. Protein and Peptide Letters 2007, 14, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Anguizola, J.; Matsuda, R.; Barnaby, O.S.; Hoy, K.; Wa, C.; DeBolt, E.; Koke, M.; Hage, D.S. Glycation of human serum albumin. Clinica chimica acta 2013, 425, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Maciążek-Jurczyk, M.; Janas, K.; Pożycka, J.; Szkudlarek, A.; Rogóż, W.; Owczarzy, A.; Kulig, K. Human serum albumin aggregation/fibrillation and its abilities to drugs binding. Molecules 2020, 25, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xing, X. Research progress on classification, sources and functions of dietary polyphenols for prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Journal of Future Foods 2023, 3, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paulo Farias, D.; de Araujo, F.F.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Antidiabetic potential of dietary polyphenols: A mechanistic review. Food Research International 2021, 145, 110383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Miroliaei, M.; Ghanadian, M. Inhibitory effect of flavonoid glycosides on digestive enzymes: In silico, in vitro, and in vivo studies. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 217, 714–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Jiang, Y. New insights on bioactivities and biosynthesis of flavonoid glycosides. Trends in food science & technology 2018, 79, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Qin, Q.; Chang, M.; Li, S.; Shi, X.; Xu, G. Molecular interaction study of flavonoids with human serum albumin using native mass spectrometry and molecular modeling. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2018, 410, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Y.; He, T.; He, R. d-Ribose contributes to the glycation of serum protein. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2019, 1865, 2285–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Schmitt, J.; Münch, G.; Gasic-Milencovic, J. Characterization of advanced glycation end products for biochemical studies: side chain modifications and fluorescence characteristics. Analytical biochemistry 2005, 338, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefek, M.; Trnkova, Z.; Krizanova, L. 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine carbonyl assay in metal-catalysed protein glycoxidation. Redox report 1999, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasymov, O.K.; Glasgow, B.J. ANS fluorescence: potential to augment the identification of the external binding sites of proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2007, 1774, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Sun, X.; Foegeding, E.A. Modulation of physicochemical and conformational properties of kidney bean vicilin (phaseolin) by glycation with glucose: Implications for structure–function relationships of legume vicilins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2011, 59, 10114–10123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, B.; Kroon-Batenburg, L.M.; Wu, Y.-P.; Brünjes, B.; Posthuma, G.; Kranenburg, O.; de Groot, P.G.; Voest, E.E.; Gebbink, M.F. Glycation induces formation of amyloid cross-β structure in albumin. Journal of biological chemistry 2003, 278, 41810–41819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-y.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Li, L.; Guo, M.-m.; He, Y.-f.; Dong, Y.-m.; Meng, H.; Yi, F. Advanced Glycation End Products in the Skin: Molecular Mechanisms, Methods of Measurement, and Inhibitory Pathways. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroliaei, M.; Khazaei, S.; Moshkelgosha, S.; Shirvani, M. Inhibitory effects of Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis, L.) extract on the formation of advanced glycation end products. Food chemistry 2011, 129, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, G.; Baig, M.H.; Lee, E.J.; Cho, W.-K.; Ma, J.Y.; Choi, I. Biophysical study on the interaction between eperisone hydrochloride and human serum albumin using spectroscopic, calorimetric, and molecular docking analyses. Molecular pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 1656–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclère, J.; Birlouez-Aragon, I. The fluorescence of advanced Maillard products is a good indicator of lysine damage during the Maillard reaction. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2001, 49, 4682–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrover, M.; Mariño, L.; Sanchis, P.; Pauwels, K.; Kraan, Y.; Lebrun, P.; Vilanova, B.; Muñoz, F.; Broersen, K.; Donoso, J. Mechanistic insights in glycation-induced protein aggregation. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 3449–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M.; Miroliaei, M.; Ghanadian, M.; Szumny, A.; Rahimmalek, M. Exploring the inhibitory properties of biflavonoids on α-glucosidase; computational and experimental approaches. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 127380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousheh, M.; Darvishi, F.Z.; Miroliaei, M. A novel biological role for nsLTP2 from Oriza sativa: Potential incorporation with anticancer agents, nucleosides and their analogues. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2015, 58, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayot, P.; Tainturier, G. The quantification of protein amino groups by the trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid method: a reexamination. Analytical biochemistry 1997, 249, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanifar, E.; Miroliaei, M. Differential effect of biophenols on attenuation of AGE-induced hemoglobin aggregation. International journal of biological macromolecules 2020, 151, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riener, C.K.; Kada, G.; Gruber, H.J. Quick measurement of protein sulfhydryls with Ellman's reagent and with 4, 4′-dithiodipyridine. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2002, 373, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kollman, P.A.; Kuntz, I.D. Flexible ligand docking: a multistep strategy approach. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 1999, 36, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Km (mM) | Vmax (mM/min) |

| Native HSA | 0.542 ± 0.061 | 1.254 ± 0.001 |

| Glycated HSA | 1.953 ± 0.091 | 1.256 ± 0.003 |

| AG 10 mM | 0.912 ± 0.054 | 1.254 ± 0.002 |

| Apigenin 1 µM | 1.885 ± 0.087 | 1.243 ± 0.004 |

| Apigenin 10 µM | 1.539 ± 0.058 | 1.239 ± 0.002 |

| Apigenin 20 µM | 1.351 ± 0.073 | 1.241 ± 0.002 |

| A4'G 1 µM | 1.754 ± 0.049 | 1.238 ± 0.001 |

| A4'G 10 µM | 1.407 ± 0.071 | 1.238 ± 0.002 |

| A4'G 20 µM | 1.162 ± 0.067 | 1.246 ± 0.002 |

| A7G 1 µM | 1.733 ± 0.051 | 1.242 ± 0.002 |

| A7G 10 µM | 1.438 ± 0.041 | 1.244 ± 0.004 |

| A7G 20 µM | 1.183 ± 0.025 | 1.236 ± 0.003 |

| Samples | OD330nm | OD360nm | OD400nm |

| HSA (native) | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.000 |

| HSA (ribosylated) | 0.740 | 0.329 | 0.114 |

| AG 10 mM | 0.168 | 0.141 | 0.027 |

| AP 1 µM | 0.548 | 0.272 | 0.113 |

| AP 10 µM | 0.342 | 0.225 | 0.047 |

| AP 20 µM | 0.447 | 0.233 | 0.066 |

| A4'G 1 µM | 0.556 | 0.276 | 0.117 |

| A4'G 10 µM | 0.334 | 0.253 | 0.078 |

| A4'G 20 µM | 0.260 | 0.210 | 0.031 |

| A7G 1 µM | 0.556 | 0.276 | 0.117 |

| A7G 10 µM | 0.334 | 0.253 | 0.078 |

| A7G 20 µM | 0.299 | 0.214 | 0.027 |

| Receptor/ligand complex | Binding free energy (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding interactions |

| HSA/AP | -7.6 | A:LYS106:HZ2 - :API:O2 |

| :API:H2 - A:GLY248:O | ||

| A:GLY248:CA - :API:O3 | ||

| HSA/A4'G | -10.4 | A:LYS199:HZ2 - :A4'G:O9 |

| A:LYS199:HZ2 - :A4'G:O8 | ||

| :A4'G:H4 - A:PRO147:O | ||

| :A4'G:H6 - A:PHE149:O | ||

| A:HIS242:CE1 - :A4'G:O9 | ||

| :A4'G:C15 - A:TYR148:O | ||

| HSA/A7G | -9.6 | A:GLN29:HE22 - :A7G:O6 |

| :A7G:H6 - A:PRO147:O | ||

| :A7G:H4 - A:GLY248:O | ||

| :A7G:H3 - A:TYR148:O | ||

| :A7G:H8 - A:GLN196:O | ||

| :A7G:C14 - A:TYR148:O |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).