1. Introduction

Resonating with the World

The aim of the present study is to attempt to integrate consciousness and cognition as a function of resonance seen as a fundamental feature of life and cognitive function where resonance is defined as an effect that is amplified when two systems are in harmony. A tuning fork set to 440 Hz or tuned to concert "A" currently in symphony orchestras, would have a second fork vibrate in sympathy with or in phase with the first if one were to tap a fork. If we were to silence the first tuning fork, we would still be able to hear the vibrations coming from the fork we did not touch. We might say that the second fork is experiencing an induced sympathetic resonant vibration or frequency. Both forks are tuned to the exact same frequency. We are aware of instances where people have broken glass with just their voice. Whoever wants to try it should lightly tap the glass with a nail or finger and then listen for the glass's natural resonance or pitch. The next step is singing a long note in the person's voice. Until the glass is broken, the vibration's amplitude increases steadily. Alternatively, a suspension bridge in Tacoma, Washington, built with steel and concrete, fell in 1940. On November 1 of that year, the bridge experienced a modest, seemingly negligible vibration along with a constant wind of about 45 mph. Unfortunately, some areas of the bridge's resonant frequency coincided with the vibration's frequency. The vibration increased until it reached a destructive resonance frequency, which caused the bridge to collapse. There is a video of the event available [

1].

A big steel and concrete bridge was demolished by resonance in one instance, while a glass was broken in another. In light of this, it is possible that we may destroy a minuscule object, perhaps a living bacterium. We might be able to modify the biological liquid crystal using a unique electronic signal, but this would require a device of some sort. A tool designed to cause a resonant vibration in a cell or other living entity was patented by James Bare [

2,

3,

4]. For instance, a 100 Hz input would cause the resonating cell to output 100 pulses per second, similarly for 200 Hz, and so forth. Once the matching frequency is found that will entrain with the input frequency, we can start looking for the "magic frequency" 1 Hz at a time. One high and one low input frequency are required, with the higher frequency being 11 times greater than the lower or the 11th harmonic [

5], where microorganisms start to break apart. The application matters a lot. Cancer cells of a certain type are sensitive to frequencies between 100,000 and 300,000 Hz [

6,

7].

We have long wondered how a biologically based machine could be built with billions of neurons that could outperform several of the most sophisticated computers. The brain has significant processing capability and nearly infinitely expandable storage [

8,

9,

10]. The idea that the brain may tune itself to a level where it can be excitable without disorder in a manner analogous to a phase transition has recently been supported. Our neurological systems have a propensity to maintain a balance between rest and chaos. Information processing is optimized when there is a state of flux between quiescence and chaos [

11]. This brings up the notion of criticality.

2. Resonating with the Brain

2.1. Thinking Critically About Criticality in the Context of Resonance

Complex systems that are on the verge of a phase change between randomness and order are said to be in a critical state. There is a unique improvement in information-processing abilities in this kind of system, and we might even speculate that the brain may play a key role. Criticality, computation, and cognitive processes are beginning to show links and linkages.We can better grasp the nature of cognition and neural processing by comprehending the concept of criticality.

Neurons that fire simultaneously link together, according to Hebb [

12]. We now understand that neurons seek a key set point and regime when they functionally join with others [

11]. Ma and colleagues have backed the idea that criticality is subject to active regulation. Criticality was mediated by inhibitory neurons in both Ma and colleagues' models and in our own [

13,

14,

15]. Larger brain networks seem to be regulated by these neurons. According to Koch & Leisman [

14], the function of criticality is to develop a computational model that may be used to optimize information processing, including the storing and transmission of intricate sensory patterns and parts of memory.

Power laws serve as the foundation for the majority of measurements in clinical neurophysiology and psychophysics. These power laws are used to separate background activity from noise using a variety of methodologies, such as the Fast Fourier Transform, signal averaging techniques, coherence, dipole source localization, and Hilbert-Huang transforms. The exponent relation is a good substitute with direct use in information processing. We might want to look into biofield physiology as a way of explaining the process of living in order to better comprehend the relationship between criticality, resonance, consciousness, "awakenness", awareness and integrated brain function.

2.2. Biofield Physiology and Information

Biological systems generate a variety of fields that are only partially diffused so that they can more effectively self-regulate and organize their physiology. This is done for the purpose of making physiological organization more efficient. Alterations to physiological regulatory systems can be brought about by biofields in a manner that is comparable to that of alterations brought about by molecular control systems. Electroencephalograms (EEG) and magnetoencephalograms (MEG) are two examples of the types of biofields that can cause changes in the synchronization of the brain's electrical activity (EEG).

It has been demonstrated that biofields are made up of forces that are dispersed across a broad region and have the ability to encode information [

16,

17]. These pressures, which also have an effect on that physiology, can control and affect the physiology of tissues and cells. As a complementary function for physiological coherence for metabolic processes, biofields coordinate the integration of several different levels of physiological activity both temporally and spatially [

18]. This is done as a result of biofields' ability to maintain physiological coherence. When referring to the qualities that constitute a living creature, the terms "biofield activity" and "resonance" can be used interchangeably in this context because they mean the same thing.

Analyzing the functional connection while at rest MRI helps us understand the brain's functioning architecture better. The technique depends on slow correlations in the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal (e.g., 0.01-0.1 Hz) in the brain. These gradual correlation patterns have been utilized to identify functional networks and to explain how they grow, alter with age, differ between people, and get disrupted in disease [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Though the fundamental mechanisms remain unclear, It is thought that delayed BOLD fluctuations and their associations represent brain processes. [

26,

27].

Two distinct types of often seen dynamics in the brain may be related to two separate underlying systems or processes. The pacemaker may affect dynamics that show narrow band-limited power [

28]. For example, the dominant occipital alpha rhythm in the EEG during peaceful wakefulness may be caused by an alpha pacemaker. A particular subset of thalamocortical neurons with inherent rhythmic bursting at alpha frequencies and gap junction couplings make up alpha pacemakers [

29]. Despite the fact that this oscillating model of resting-state activity is well supported e.g., [

28,

30], The most commonly recognized hypothesis in the field holds that brain activity propagates within an anatomically limited small world network to produce correlations [

31,

32]. Scale-free dynamics, or 1/f dynamics, are predicted by this model [

33,

34,

35]. Large events are rare whereas little events are frequent in 1/f dynamics because of the inverse relationship between event amplitude and frequency. More specifically, as frequency is increased, even by a small exponent, power can change inversely:

P ∝ 1/

fβ, with common exponents ranging from 0 to 3 [

36]. Though they can also happen in other noncritical systems, 1/f dynamics are a feature of complex dynamic systems operating at a critical point, when the system is balanced between ordered and disordered phases [

37,

38]. The 1/f features of many neural signals, including local field potentials, have encouraged models of the brain operating at a crucial point by a process of self-organization [

39,

40,

41].

A high level of sensitivity to particular stimuli, and by extension, particular signal frequencies, are necessary for coherent physiology. This sensitivity is required, among other things, for the effective coordination and integration of internal biological systems. Coherent physiology requires not just efficient coordination and integration of the body's internal biological systems but also a significant sensitivity to particular stimuli and, as a result of this, particular signal frequencies. Exogenous energy that is generated either biologically or non-biologically appears to be vulnerable to and entrains human physiological systems, according to a significant body of research in this area. During physiological activity, it is possible to collect measurements of electrical and magnetic fields; however, this may lead to confusion since metabolic processes or the outcome of physiological action are not completely known [

19,

20].

It is recognized that there will eventually be shared resonance, both within and between individual species, because all living things resonate at comparable or coherent frequencies. In the neurosciences, resonance theory has long been noted. Crick & Koch [

21], Fries [

22,

23] and Koch [

24] have studied the concept of resonance. According to Fries, a critical component of the nervous system's operation was brain synchronization, resonance, or "communication through coherence,".

2.3. Consciousness as a Function of Resonance

Resonance is thought by many theories to contribute to conscious states. According to Dehaene's Global Workspace Theory, integrated conscious activity is the outcome of long-distance connections between synchronous or resonant cortical areas [

24,

25]. By claiming that while consciousness, which is associated with being awake and aware, is a function of resonance, it is not always a property of all resonant states, Grossberg [

26] extended on the idea of brain communication-based resonance. Phase changes in resonance were also considered vital for understanding brain function by Freeman & Vitiello [

27]. When Pockett proposed an electromagnetic field theory based on the synchronization from movement feedback when differentiating between conscious and non-conscious fields, she raised the significance of resonance in understanding integrated brain activity [

28,

29]. Others have developed further resonance-based theories of brain integration, such as Bandyopadhyay and colleagues' [

30]. Fractal Information Theory [

31,

32,

33]. As a result, albeit still in theory and without practical application, resonance's importance in comprehending brain communication systems has begun to gain some traction.

The concept of resonance is intimately connected to awareness, interregional connections or disconnection in the brain, and its integrative function. It can be used to describe synchrony, vibration, or harmony more broadly. Similar resonance patterns can be found in the brain's synchronized electrical cycles. Resonance's significance in fostering integrated brain activity must be properly understood in the context of death, which must be considered.

3. Resonating with Life (and Death): Gaps in Current Understanding

One of the numerous hypotheses that try to explain life and living is the assumption that life function comes from organized computer-like activity in the neural networks of the brain that are connected with mental states. Another notion is that the temporal binding of information in these networks is associated with synchronous oscillations between the cortex and thalamus. How we think consciously may be impacted by the complexity of neural computing.

Death itself is not noteworthy until a clinical definition is required. It is more important to comprehend the mechanisms at play during the lack of consciousness, though. Although death seems to us to be a real event and an undeniable state, a corpse, whether human or otherwise, continues life function even after it has been proven that it is dead. There is minimal disagreement that the person is dead despite a few isolated cells, nests, or cell subnetworks that continue to function.

As we continue, the argument becomes more challenging since, despite the brain having "died," peripheral body organs like the heart, lungs, liver, and other organs are still functioning due of modern developments. In the past we had thought that the body perished when the full brain expired, and resultantly physical functions ceased. Nevertheless, the development of modern technology has made it difficult for us to determine the precise moment of death. The constituent components of consciousness or micro consciousness entities are required to combine to provide us with the vividness of the conscious experience bringing us to the combination problem.

3.1. The Combination Problem

The combination problem asks if lower-level micro-consciousnesses can join together to produce higher-level macro-consciousnesses. According to the suggested explanation, distinct brain regions may undergo a phase shift in the bandwidth and speed of information flow between them when it comes to a common resonance in the setting of mammalian consciousness. More complicated variations of consciousness may form as a result of this phase transition, and the nature and content of those varieties will rely on the specific combination of component neurons that are present at any one time. To distinguish this perspective from emergent materialism, we can provide more thorough insights into the ontology of consciousness and propose that awareness manifests as a continuum of increasing richness in all physical processes. This procedure might be referred to as a metasynthesis, and it is also known as a general resonance theory.

3.2. Everything Has a Unique Resonance

Everything in the universe is always changing and evolving. Certain frequencies cause even seemingly immovable things to vibrate, oscillate, or resonate. As a result, everything is genuinely oscillating, and coordinated oscillation between two states is what defines resonance. Different oscillating processes often start vibrating at the same frequency when their frequencies are close enough [

34]. Sometimes they "sync" in unexpected ways that accelerate and enrich the flow of energy and information. By examining this occurrence, significant insights into the nature of consciousness—both in relation to humans and other mammals and on a more basic level—may be gained. Using a range of resonant examples from physics, biology, chemistry, and neuroscience, [

34] aimed to illustrate the nature of synchrony in relation to the experience of consciousness. These examples included: Certain species of fireflies that start to flash their bioluminescent fires in unison when they are in huge groupings. Mammalian awareness and the ability of human brains to fire large numbers of neurons at specific frequencies are believed to be closely related to various forms of neural synchronization [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. We always see the same face of the moon because its spin precisely matches its orbit around the planet. When photons with the same frequency and power are discharged simultaneously, a laser is produced. At this point it can be helpful to consider how resonance and synchrony differ in relation to our inquiries.

3.3. What is Resonance and Synchrony?

The tendency for multiple processes to move together, or oscillate, at the same or a comparable frequency is known as resonance or synchronization. Synchrony, also known as harmonic oscillator theory or complex network theory, is the study of how connected oscillators behave in relation to one another.

The following two queries are raised by numerous instances of resonance: How do the constituent elements of resonant structures—a phrase that refers to any grouping of resonating components—interact with one another and, once achieved, how do they reach resonance? Examining each question individually, paying close attention to the first two examples we gave above: (1) The significant neural synchronization in mammalian brains; and (2) the synchronization of flashes in fireflies.

The sort of communication between each resonant structure will vary depending on the scenario being studied, and in many resonance cases, clear conclusions are difficult to derive. Each firefly has access to visual signals, but it is also likely that it has access to olfactory, chemical, and perhaps electrical or magnetic stimuli. One of the two instances of intricate resonant structures we can utilize are fireflies. On the basis of empirical studies, it seems that a key factor in how firefly populations coordinate the synchronization of their bioluminescent flashing is visual perception [

34].

It is less clear how each neuron communicates with the others when neuronal synchronization occurs in the brain. Neural synchronization that happens too quickly to rely solely on electrochemical neuronal communication is known as electrical field gamma synchrony; it requires electrical field signaling, according to Freeman's studies of the brains of rabbits and cats. As noted by Freeman & Vitiello [

27], high temporal resolution of EEG signals indicates that the beta and gamma ranges of carrier waves regularly re-synchronize in miniscule time lags over wide distances, providing evidence for a variety of intermittent spatial patterns. Axodendritic synaptic transmission, the predominant mechanism for brain interactions, should cause the EEG oscillations to experience distance-dependent delays because of successive synaptic delays and restricted propagation velocities. The coherence of global brain gamma "synchrony" cannot be adequately explained by gap junction coupling alone, according to Craddock et al. [

35]. However, what is currently known suggests strongly that shared resonance plays a pivotal role in the development of mammalian consciousness, including human consciousness.

3.4. How Is Shared Resonance Attained in Resonating Structures?

How do entities that are in connection with one another through resonance modify their resonance frequencies to reach resonance with one another? In many circumstances, entities that are initially unsynchronized manage to become entrained. What driving forces are behind these processes?

We may compare the mechanisms that enable firefly synchrony to conscious human activities in terms of how fireflies time their flashes. For instance, our brain sends a series of neuronal pulses to our finger when we wish to lift it, causing the desired action. Similar to fireflies, it's conceivable that when a fly decides to flash its lights, an electrical pulse travels from its brain to its abdomen.At that point, the physiological and chemical processes responsible for the fly's bioluminescence come into play.

It might seem unusual to attribute intent to fireflies. Nonetheless, it would make sense that fireflies would be aware of and able to intentionally manage of their physiological functions, especially those associated with large organs such as their light-producing organ. Their actions are intricate and show a variety of "behavioral correlates of consciousness." By comparing the different neurological and behavioral similarities between humans and other mammals, we may recognize that fireflies probably only have a basic level of conscious awareness without implying that they have anything close to the depth of human consciousness.

On the basis of the supposition that fireflies possess a primitive kind of consciousness, compared to human consciousness, we may provide a high-level explanation for how flashes are synchronized without considering the intricacies of sub-level mechanisms. This makes an explanation simple: the body obeys the will of the brain, in the same way that any conscious activity in a person, dog, cat, etc. would be explained. However, we can also explain firefly flashing synchrony without intelligence or consciousness. This is Strogatz's method, and he and his colleagues proposed intrinsic biological oscillators that automatically sync with neighbors to explain the mystery of firefly synchrony [

34].

It would be difficult to argue that individual neurons want to be in synchrony, but there is evidence for some form of neuronal consciousness, however basic it may be in comparison to whole-brain consciousness. How do neurons synchronize so swiftly and regularly? Although there are numerous indications that point to different kinds of field effects, this is still unknown. How this communication occurs in each neuron to quickly adjust its electrical cycle so as to meet rapidly changing macroscopic patterns is still unknown.

Keppler [

36] focused on the phase changes observed in mammalian brains and the general "criticality" that these brains appear to be in., meaning that they are very sensitive to even minute changes. It is possible to think of brain mechanisms underlying conscious activities as a complicated system that functions close to a key point of a phase transition. With appropriate stimuli, the brain can transition from a disordered phase with irregular dynamics and spontaneous activity to an ordered phase with long-range connectivities and stable attractors.

The idea of a "phase transition" could be significant when thinking about the combination problem and macro-consciousness. Phase transitions include the freezing of water into ice and the condensation of water vapor into droplets. Similar to brain states, neural states can oscillate in reaction to seemingly unimportant inputs. Dehaene [

25] provides evidence in favor of the theory that phase transitions are essential to mammalian consciousness.

A cognitive frequency trio of particular electrical brain wave combinations is described as follows by Fries [

22,

23]: gamma-band synchronization carries out the attended stimuli's selective communication, beta-band synchronization mediates top-down attentional influences, and a 4 Hz theta rhythm resets gamma regularly. Because nature is made up of numerous lawful processes, each will resonate at different frequencies. Additionally, processes that are close to one another may eventually synchronize and resonate at the same frequency.

5. Criticality of Resonating Consciousness

A collection of psychophysical concepts that would explain the connection between consciousness and physical systems were suggested by Schooler & associates [

38] and Hunt [

37].They elaborate on how it is that resonance is essential for establishing macro-scale awareness by combining several micro-conscious entities at different organizational levels.

Without subscribing to panpsychism or panexperientialism [

37,

38,

39,

40] [we can state that connected consciousness is significantly primitive in the vast bulk of matter, maybe only an electron or an atom's primitive humming of awareness. However, in certain kinds of groupings of matter, as in sophisticated biological life forms, awareness can grow notably richer in comparison to the bulk of matter [

41,

42].

All objects could be considered to be at least somewhat conscious on the basis of the observable behavior of electrons, atoms, molecules, bacteria, paramecia, mice, bats, and rats. An emergentist perspective contends that consciousness appeared where it had not before existed and arose at a specific period in the history of each species that experiences consciousness. Panpsychism is the opposing position to this theory.

Panpsychism contends that rather than emerging, matter and the mind are always connected, and vice versa (these two sides of the same coin are equally significant.). However, the mind that is constantly connected to all matter is typically quite primitive. Only a very small amount of consciousness exists within an electron or an atom. But as matter becomes more complex, so too does the mind, and vice versa. Nevertheless, in this situation, complexity does not matter. Instead, it is the result of stronger internal and external connections that resonate. A mathematical version of the concept was developed by Hunt [

39,

43], emphasizing how resonant connections result in larger-scale consciously aware beings and how relevant characteristics may be characterized and measured.

Although we will not go into great detail here, (see [

37,

39,

41,

44] supported by others [

38,

40,

42]. According to Tononi & Koch [

42], elementary particles are either charged or not while discussing panpsychism within the context of Integrated Information Theory. As a result, a photon, which is a carrier of light, has no charge, a proton has one positive charge, and an electron has one negative charge. According to Tononi & Koch, charge is a feature that these particles have by nature in the fields of chemistry and biology. Charge is just present in uncharged materials; it does not arise from them. Their reasoning is that consciousness is no different. Matter is arranged to give rise to consciousness. It is ingrained in the system's architecture. It is a characteristic of complicated things that cannot be boiled down to the operations of more basic attributes.

When two entities resonate at the same frequency, they bond or join in a variety of ways. Such common resonance and binding may sometimes lead to the blending of different characteristics of cognitive, perceptual, and their motor equivalents into a more cohesive whole, depending on the entities under discussion [

9]. According to quantum field theory, at the most basic level, matter is actually more akin to a little standing wave of concentrated energy. Each of these waves is regional in both distribution (spatially) and time.(temporally).

Since matter is fundamentally wave-like, it is easy to understand how information transfer, and ultimately the emergence of macro-conscious forms, are associated with shared resonance. All physical processes are fueled by waves of various kinds, at least partially. Waves collaborate instead of competing when multiple entities resonate at the same frequency. This leads to significantly faster energy and information transfer between the components of whatever resonant structure we are observing, as well as a much wider bandwidth. Subsequently, the information flows merge into a larger harmonic and the resonant wave shapes of the micro-conscious organisms become coherent rather than occurring out of phase (decoherently).

Furthermore, Christof Koch [

24] suggested that feedback pathways may play a crucial role in producing a type of standing wave or resonance in the brain network if information is amplified and sustained in the brain by top-down attention. Beyond the degree of synchronization generated by sensory input alone, neurons have the ability to coordinate their spiking activity, if they receive more local and widespread feedback. This amplifies their postsynaptic impact in comparison to when they activate independently. On this basis, a significant network of neurons may be developed capable of exerting impact throughout the cortex and between lower brain structures. This would be the slow mode upon which conscious awareness rests, according to Koch.

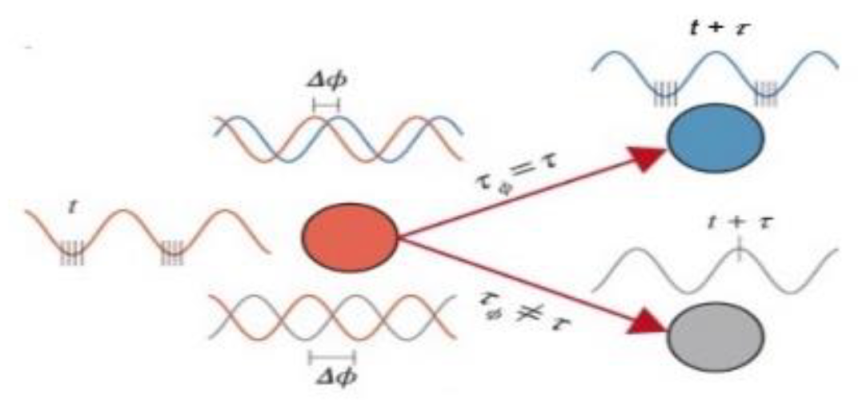

Expanding on Koch's theories, Fries [

22,

23] proposed a "communication through coherence" theory. Fries [

23] offered the following example of shared resonance in relation to neural resonance/coherence: Inputs happen at various times during the excitability cycle due to a lack of coherence, and their effective connection will be consequently reduced. Nonetheless, inputs will spread faster and over a wider bandwidth if they fall within the same excitability cycle.

Through a variety of biophysical information pathways, organisms gain from faster information sharing. More macro-scale levels of consciousness are able to emerge thanks to these speedier and richer information flows than would be feasible in similar-scale structures like sand heaps or rocks because biological structures are more active and more interconnected than rocks or sand. But the kind of interconnectivity that is required has to be predicated on resonance processes, which usually cause a phase shift in the information flow rate as a result of the conversion of incoherent structures into coherent ones.

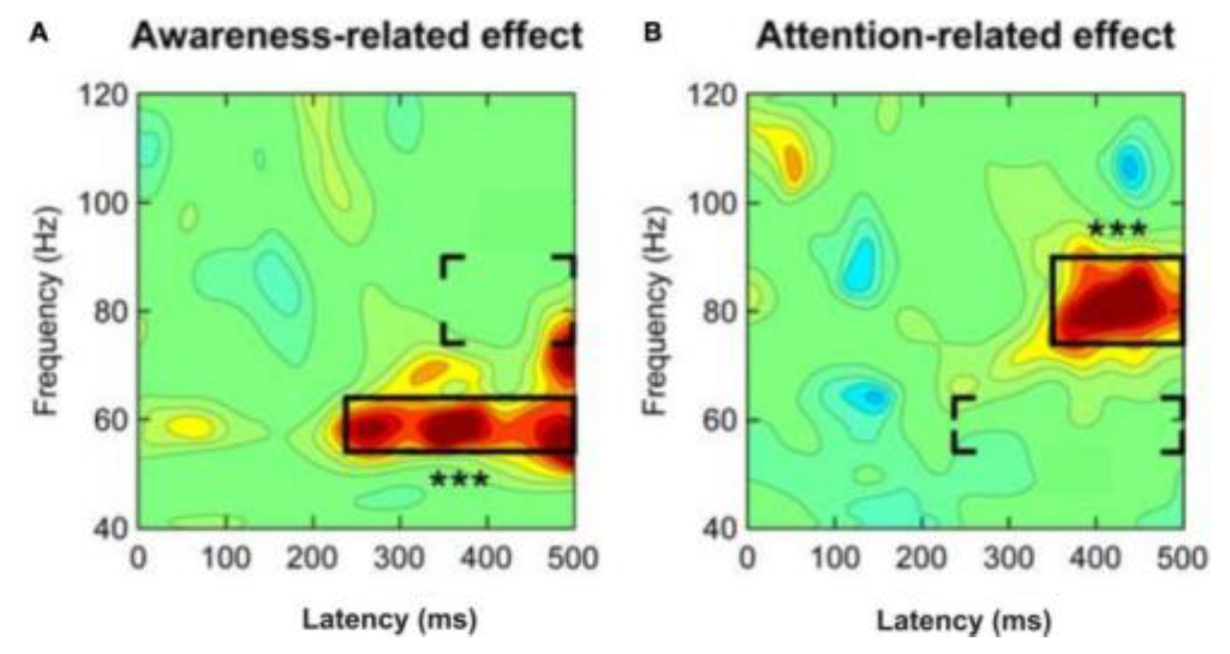

We know that gamma synchrony is a main neurological correlate of consciousness in human brains a notion supported by Dehaene [

25]. He was particularly interested in certain "signatures of consciousness," such as late-onset gamma synchrony [

45]. However, a combination of gamma and lower harmonic frequencies is frequently linked to mammalian consciousness [

23]. This common resonance creates an electromagnetic field that, through certain neuronal electrochemical firing patterns, might act as the source of macro-conscious information [

28,

46,

47,

48,

49]. Gamma synchrony is used as an example of how more neurons get incorporated into the common gamma synchrony, which Hameroff [

45] refers to as "the conscious pilot". This is backed up by other slower frequency waves [

23]. However, when the shared gamma synchrony recedes from specific neurons, it allows those neurons to return to their previous resonance state, resulting in a pattern that is more localized.

In order to entrain additional neurons, this moving large-scale wave absorbs them into a semi-stable gamma wave pattern. This allows the pace of information interchange to shift from mostly electrochemical to electromagnetic, and allows the capacity for information processing of the several micro-conscious entities made up by those neuron clusters to be combined into a macro-conscious entity. The larger harmonic is entrained with the smaller-scale harmonics.through this process; hence, all of the constituents' "windows" are opened to one another, facilitating more fluid information transmission. The pace of change of macro-consciousness is precisely the same as that of its constituent neurons and associated fields.

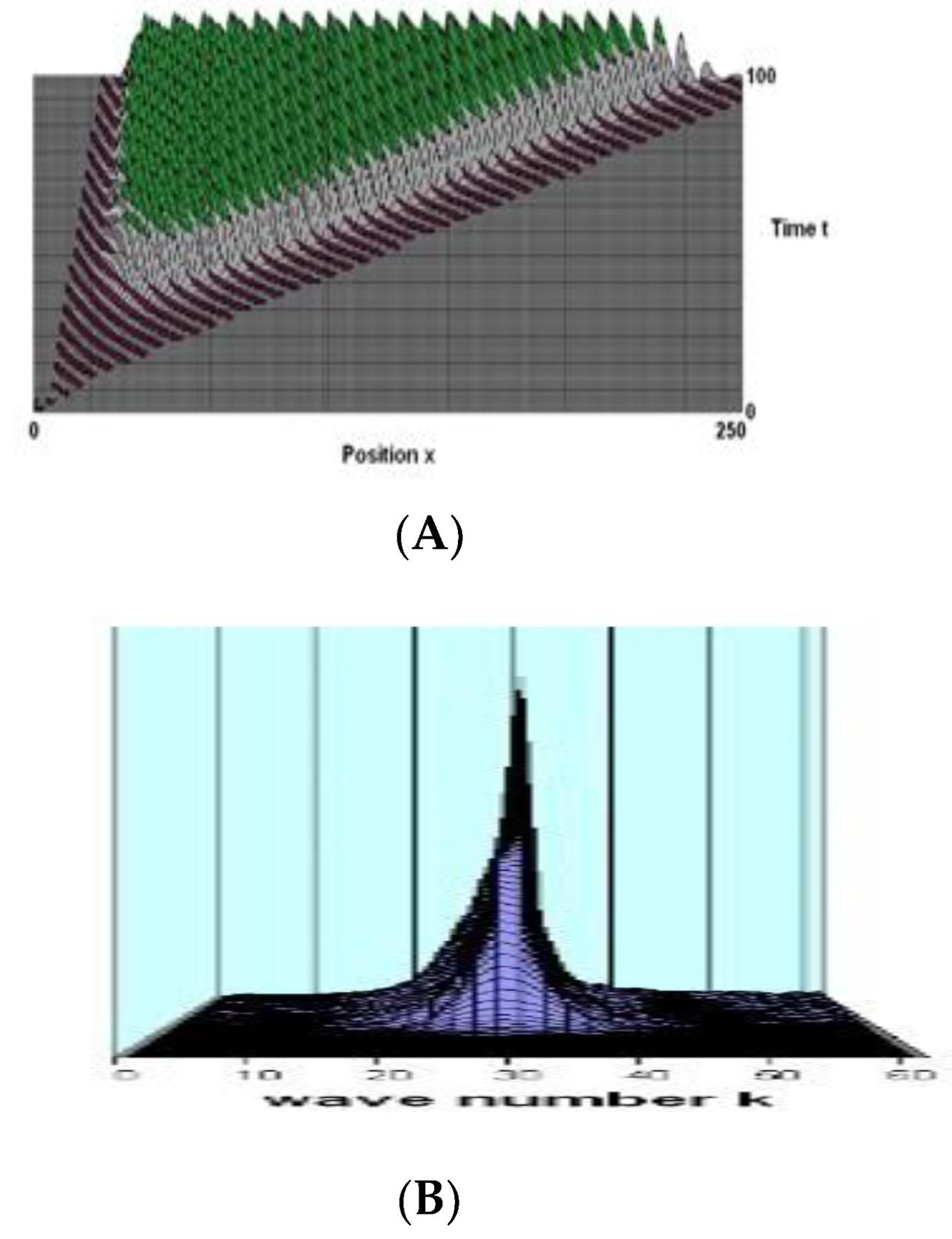

Figure 1 shows an example of such a procedure.

Whitehead [

51] indicated that the many become one and are augmented by one. In other words, lower-level entities are employed to create a new, higher-level entity; however, the lower-level entities are not eliminated during the binding process; rather, they are bound into the new entity, hence increasing the number of entities by one. The many increase one by one until they achieving unity. Numerous subsidiary micro-conscious entities are included when the "conscious pilot" circumnavigates the brain; these numerous aspects of consciousness merge into a single dominating consciousness, leaving the subsidiary consciousnesses alone.

6. Coherence in Resonance

Fries [

23] uses his Communication Through Coherence (CTC) paradigm to explain how resonance among various brain regions has a part in "selected communication" (the "windows" that are open when coherent and resonant and closed when incoherent and not resonant). Furthermore, coherence enables certain neurons to synchronize with the main resonance frequency. Fries [

23] states that communication requires coherence. When there is a lack of coherence, the excitability cycle experiences random inputs, which reduces effective connectivities. A postsynaptic neural group responds mostly to the coherent presynaptic group when it gets inputs from many presynaptic groups. Selective communication is thus accomplished by selective coherence.

Lack of coherence causes inputs to come at random times during the excitability cycle, which lowers effective connectivities. If one group of synaptic inputs, which collectively create one neural representation, is able to elicit postsynaptic excitation followed by inhibition, then further synaptic inputs will be unable to enter the cell because inhibition will have prevented that for happening. Consequently, these additional inputs are unable to inhibit themselves, and they cannot communicate the neuronal image that they generate. By entraining the postsynaptic neuronal group's perisomatic inhibition and instructing it to follow its own rhythm, this tactic creates a selective or exclusive communication channel.

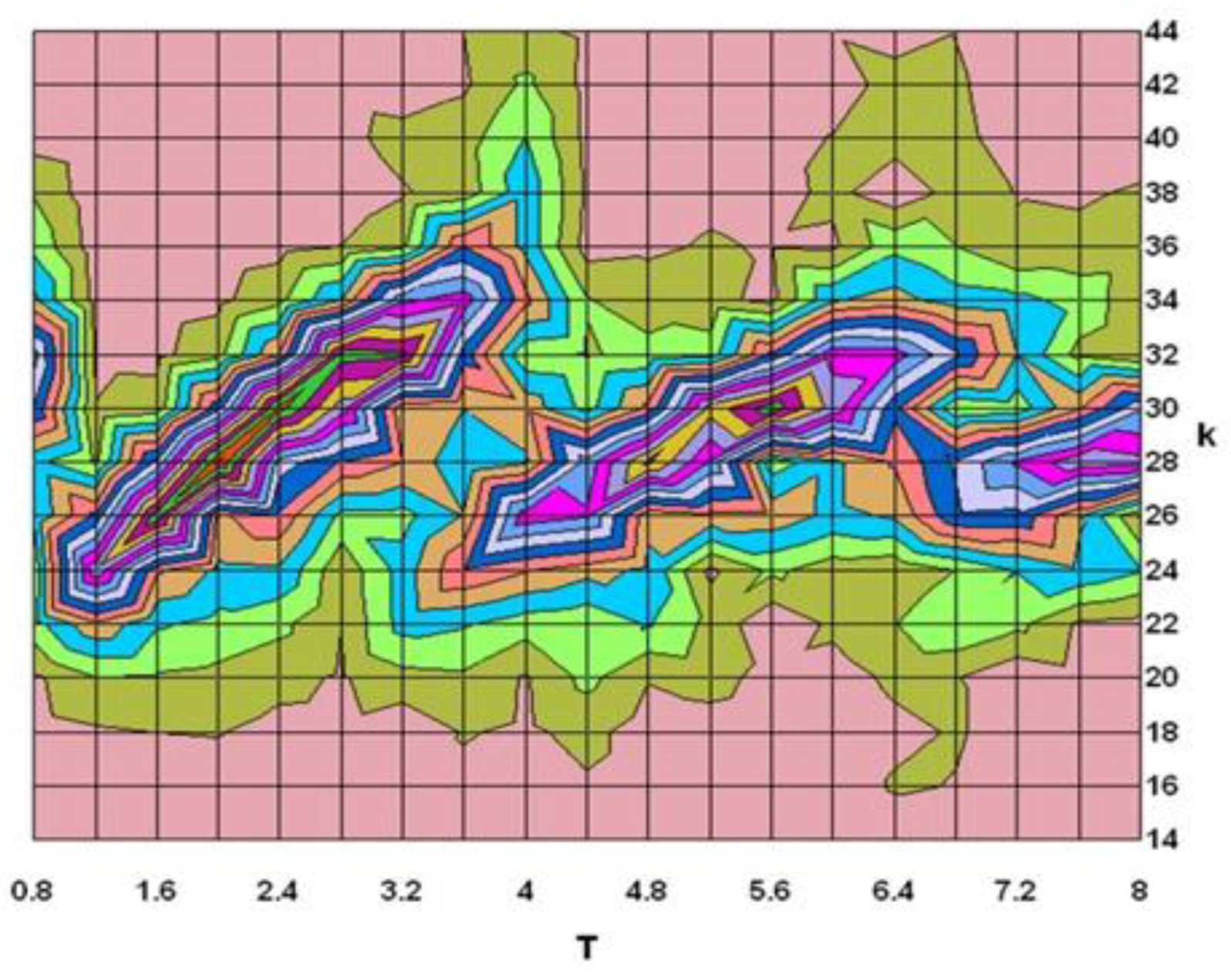

Figure 2 is an example of optimizing interregional brain communication.

It is now thought that small organisms merged to create the organelles (e.g. mitochondria) of more advanced eukaryotic cells, which then joined to produce multicellular organisms [

53]. It seems plausible that life acquired the ability to incorporate subjective experiences into nested hierarchies of higher-order conscious individuals at the same time that it obtained the ability to unite various living units into more complicated solitary life forms. The hypothesis was suggested by Zeki & Bartel [

54,

55]. to explain how consciousness develops from neuronal activity in the brain relies on this hierarchical view of awareness.

Zeki & Bartel [

54,

55] contend that the brain arranges multiple conscious experiences in a hierarchical fashion to produce a single, cohesive experience using variations in the processing rates of various parts of the visual system. They proposed that consciousness exists on three different hierarchical levels in the brain: unified consciousness, which corresponds to the experience of the individual experiencing the perception; micro-consciousness, which corresponds to the different levels of the visual system that process distinct attributes (e.g., V5 processes motion and V4 processes color); and macro-consciousnes swhich integrates multiple attributes of a system (e.g., binding color to motion).

Zeki further suggests that there is a specific temporal order in which each of these nested levels of awareness happens, with the lower order levels coming before and influencing the higher order ones. The reason for this is that the lower order levels are more fundamental. Zeki's model can be explained as follows [

55]. According to Zeki, there are three distinct hierarchical levels of awareness: micro, macro, and united consciousness. One level must depend on the presence of the level below it. One might imagine a temporal hierarchy at each level. For the microconsciousness level, this has been demonstrated due to the fact that color and motion are perceived differently. Zeki [

55] claims that it has been demonstrated that binding across characteristics takes longer than binding within attributes at the level of macro-consciousnesses."Myself" is the perceiving individual, the product of individual temporal hierarchies of micro- and macro-consciousnesses leading to a final, combined consciousness.

The smallest sentient observers may be found exclusively in the inorganic world at the atomic and molecular level. Life's evolution may have given rise to the capacity to organize conscious observers into hierarchies within other conscious observers, each level embracing a more macroscopic perspective based on the (rudimentary) level of awareness intrinsic to atoms and molecules. When the organism's unified dominating experience occurs, this process ultimately reaches its greatest level.

Zeki divides his suggested levels into chronological sequences, with higher-order events taking place later in time. In other words, Zeki's hypothesis suggests that different brain regions that are involved in consciousness may go through the same experiences for slightly different times and for varied lengths of time, with the ultimate unified awareness involving the longest moments/duration of experience.

7. Integrating Consciousness and Cognition Through Resonance

There is evidence that shared electrical resonance is probably the origin of combination [

22,

23]. This shared electrical resonance may also be preceded and lead by a shared quantum entanglement resonance. The largely unchanging physical structures can support several states of consciousness because of the constantly shifting energy and information fluxes that overlay the typically stable physical structures. This is excellently shown by Fries [

23], who challenges whether brain communication is dependent on neuronal synchronization, suggesting that the communication pattern could be altered by dynamic shifts in synchronization. Fries refers to stable structures as the "backbone" of conscious processes. According to Fries, the fundamental components of cognition are these adaptive modifications to the brain's communication system, which are reinforced by the more inflexible anatomical structure, but operating through activity waves.

Constraints on the common resonance states may prevent physical materials from generating macro-consciousness. Situations that are disorganized and non-resonant hinder the exchange of information spatially. Dominant consciousness—like the waking consciousness that people experience—needs large-scale common resonance. There exists a hierarchy of resonance in brain networks [

56,

57]. Even when higher-level resonance, which represents more degrees of integration, is temporarily absent (such as during a seizure, sleep, or death), there can still be lower-level resonance, which requires less information integration (death, in which case lower-level resonances may continue for some time but will also, before too long, dissipate). Physical materials in small spaces may not become macro-aware. [

56,

57].

These mechanisms may account for the observed phenomenon of important brain regions synchronizing at regional levels during seizures in the absence of global consciousness [

58]. Characterizing conscious experiences during absence seizures is often challenging since higher levels of organization lose their characteristic synchrony while lower-level systems (individual and local clusters of neurons) remain in synchrony [

13,

15,

59]. Since resonance reflects the physical structure’s dynamics, changes in resonance and awareness states do not affect the stability of the physical structure.

8. Cortical Activity Waves as a Vehicle for Consciousness and Cognition

Mammalian brains differ from reptile brains in that they have layered anatomy [

60], which implies that possessing this structure has some evolutionary advantage. We here propose that the layered cortex structure permits a time delay in the interconnections between its layers, and that this temporal lag efficiently controls brain activity waves, which are cortical tissue's resonant modes and the electrochemical energy they store. When enough energy is stored, these waves expand as they move to locations that are substantially farther from their origin than the normal axonal length, and they interact with most of the cells in their path until they reach their saturated amplitude.

The forgoing is grounded on the revolutionary continuum analysis of Wilson and Cowan [

61,

62], applied to a simple system with two filamentary layers that are separated by a uniform time delay in space and undergo modest temporal variations [

63]. In the Wilson-Cowan model, all other components are driven by synaptic flux into hypothetical "continuum elements," which act as energy reservoirs; flux and stored energy are connected via what is compared to a "leaky capacitor." The energy is stored in the excitatory (e) and inhibitory I activities of the constituent cells, which are considered to be of two types. The internal energy of each species is considered independently. Elements can be connected in four distinct ways: e-i, i-e, e-e, and i-i. The afferent species is indicated by the first index, while the efferent species is shown by the second index. The length over which the typical connection probability of each afferent species is termed the connection range which is the length of time that decreases with distance along the layers [

61].

The neuronal continuum can be impacted by waves of spreading and rising activity [

64,

65]. When one element exhibits some excess of excitatory activity, the return i-e connections lower the excitatory surplus in the originating element, while the e-i connections to adjacent elements raise the inhibitory activity. Oscillations are linked to an overcorrection, as is often the case. Meanwhile, e-e and i-i linkages stimulate development and proliferation by way of transmission to additional elements. Since the factors governing wavelength and frequency are essentially constant and only vary through synaptic modulation, this approach does not meet the requirements for carriers of cognitive processes [

66].

Because of the phase relations required for wave amplification, the delay adds control. The wave is now generated as before by an excitatory surplus element, but it separates in two, with one half propagating to the opposite layer with a delay of T. The relationship between flux and activity in the second layer leads to a phase shift that is close to π/2. A similar procedure is followed to return to the original layer; Only when the overall phase shift is an even multiple of π does amplification take place. Consequently, the link between the delay and the angular temporal frequency of the favored wave is multivalued.

The integer n that yields the fastest growth—which is initially exponential—is the one selected in each given scenario [

67]. The rate of this growth usually leads to the clear dominance of the selected mode. Nonetheless, both modes expand at those values of T where their growth rates are equivalent, and this situation continues until

T reaches a point when the new mode takes precedence. When it comes to activity waves, the propagation speed increases with wavelength, and the wavelength is a single-valued function of frequency. As a result, the waves move through space at various speeds and occupy various locations, creating a highly erratic pattern of activity in between.

8.1. The Wilson-Cowan Equations

The relative active percentages

Asl s=e,i, l = 0,1 at time

t of the various species in the two layers, within an element centered at position x, are the dependent variables in our model (there are four in total).

Here,

N reflects the synaptic flux into the element from all other elements, weighted by the inter-layer signal latency, and by the connection probability decreasing with distance.

The connection coefficients Bus,ml possess, when the cells are in the same position laterally, an afferent connection probability of cell of species u and layer m that is proportional to the species and layer in question.

The exponent describes the connection probability decreasing with lateral distance from the afferent element at position X to the element at location x; the connection range ϭus,ml is considered to exclusively depend on the afferent species. For the sake of this calculation, all inter-layer connection parameters and connections within the layers are assumed to be the same in both directions. Delay Tml applies only if m and l relate to different layers when it equals T. A typical synapse's synaptic energy is represented by the attention parameter F. T and F remain constant here and the integral encompasses all of space, whereas the sums cover both species and strata.

The sigmoid function S must be used as a flow limiter since when all cells are active, the total stored energy cannot vary, nor can it decrease when none are. Since it is assumed that both species and layers have an equilibrium activity level, which is taken to be ½, the active fractions fall between -½ and +-½. When the synaptic flux is zero, S's functional form is zero with a slope of one. A decrease toward equilibrium with a time constant of unity is represented by the second term in (2).

8.2. Numerical Results

The excitatory active fraction is considered to have been subjected to a δ-function impulse with amplitude 0.0001 (above equilibrium) at time zero, and the first time-step is carried out analytically in order to seed all the points. A convergence test is included in the Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg (RKF) method, which is used to simultaneously solve the equations in (2). A cubic spline integrated analytically is used to compute the integral in (3) at each function evaluation (use of discrete methods leads to spurious spectral lines). The same-layer inhibitory connection range acts as the spatial unit and is used to represent all other ranges.

The 2048 amplitudes are written at intervals of several time steps in temporary files to account for the time delay; linear interpolation is employed to obtain the intermediate values required for the RKF test. The computation is terminated when a detectable signal reaches the final point in order to prevent end effects. Fast Fourier transform (fft) is used after every time step; this establishes the connection between wavelength λ is λ = 256/ k and spectral variable k.

The 2048 amplitudes are stored in temporary files until they are needed, accounting for the time delay; they are written at intervals of multiple time steps, and the RKF-required intermediate values are acquired using linear interpolation. To avoid end effects, the calculation is terminated when a detectable signal reaches the last point. A fast Fourier transform (fft) is run following each time step; the formula for the relationship between spectral variable k and wavelength λ is λ = 256/k.

The findings for two values of delay are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Only positive amplitudes are displayed for clarity's sake. Since the neural refractory period is longer, negative amplitudes are slightly bigger [

61].

Figure 1.

(A) The wave produced at time zero by a very slight variation (0.0001) in the excited fraction in an element located at layer 0 position. Here, we see the exponential growth of the wave amplitude in the stimulated layer, which is driven by the flux limit to saturation, with a maximum amplitude of around 0.4. Time units are decay durations, while spatial units are the same-layer inhibitory range. (B) The identical wave's spectral intensity as a function of time and wave number k (into the diagram). In the same layer, the connection parameters are: Bee = 3.5, Bei = 5.9, Bie = -4.8, Bii = -2.5, σe = 1.25, σi = 1.0; for opposite layers Bee = 3.0, Bei = 1.1, Bie = Bii = -1.0, σe = σii = 0.6. The attention factor F = 0.45, and the time delay T = 2.4.

Figure 1.

(A) The wave produced at time zero by a very slight variation (0.0001) in the excited fraction in an element located at layer 0 position. Here, we see the exponential growth of the wave amplitude in the stimulated layer, which is driven by the flux limit to saturation, with a maximum amplitude of around 0.4. Time units are decay durations, while spatial units are the same-layer inhibitory range. (B) The identical wave's spectral intensity as a function of time and wave number k (into the diagram). In the same layer, the connection parameters are: Bee = 3.5, Bei = 5.9, Bie = -4.8, Bii = -2.5, σe = 1.25, σi = 1.0; for opposite layers Bee = 3.0, Bei = 1.1, Bie = Bii = -1.0, σe = σii = 0.6. The attention factor F = 0.45, and the time delay T = 2.4.

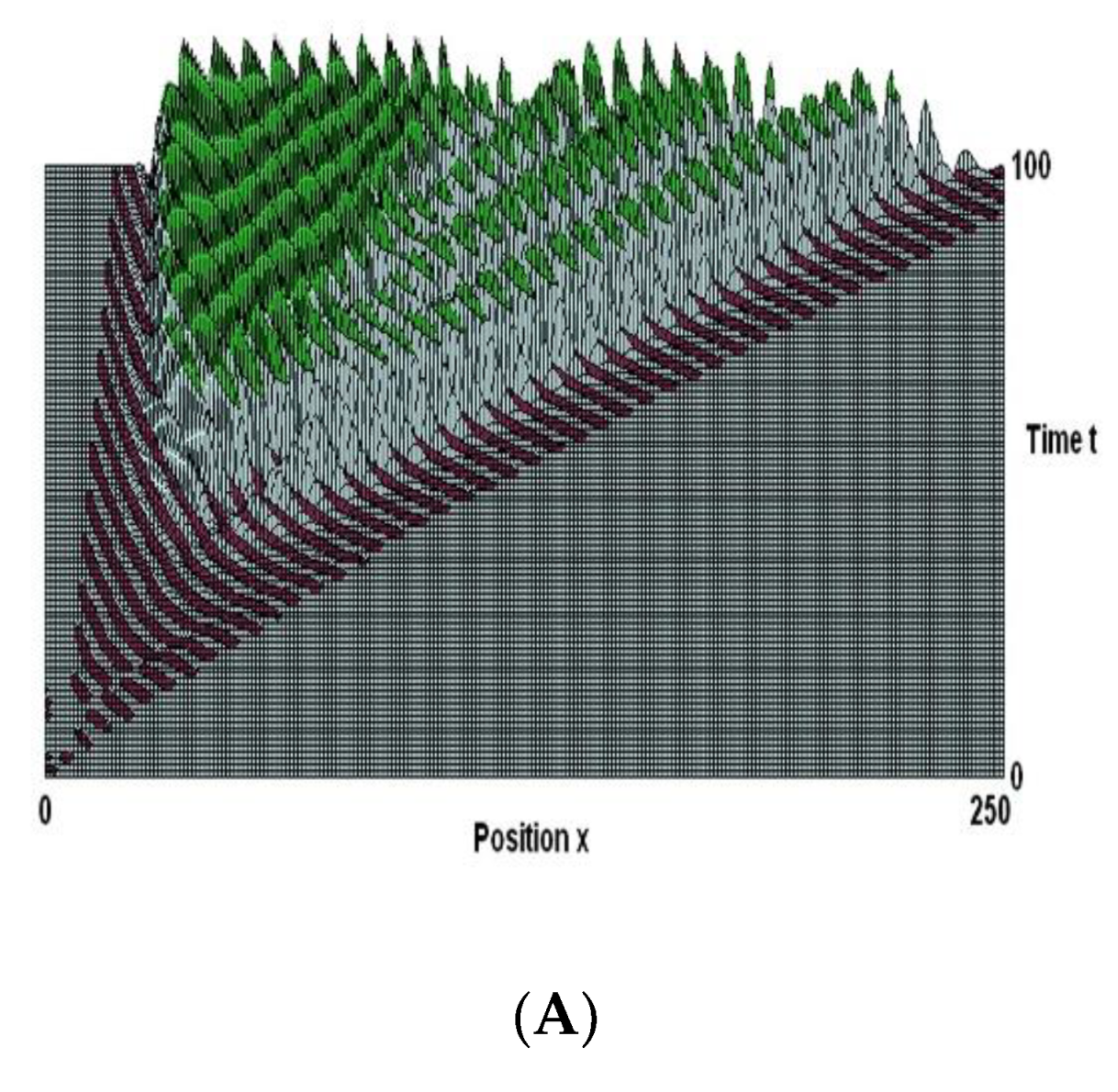

Figure 2 shows the scenario at a different value, in contrast.

Figure 2.

Here the parameters are the same as in

Figure 1 except the delay

T is 3.6 decay periods. The initial noise now generates two waves, with different wavelengths. Propagation speed increases with increasing wave-length, so that the waves occupy different spatial regions. There is erratic activity in the intermediate space. The energy is spread between the two spectral peaks, as shown by their lesser amplitudes. Later on, non-linear interference excites other waves with shorter wavelengths.

Figure 2.

Here the parameters are the same as in

Figure 1 except the delay

T is 3.6 decay periods. The initial noise now generates two waves, with different wavelengths. Propagation speed increases with increasing wave-length, so that the waves occupy different spatial regions. There is erratic activity in the intermediate space. The energy is spread between the two spectral peaks, as shown by their lesser amplitudes. Later on, non-linear interference excites other waves with shorter wavelengths.

It is clear that the wave in

Figure 1 is coherent due to its regularity and narrow spectral peak. Despite the random position of the starting noise, active and inactive elements behave in lockstep when they are one wavelength apart. Two waves are produced under the parameters shown in

Figure 2; they propagate at different speeds and occupy various spatial regions, have different growth rates, and have different wavelengths. There is erratic activity in the middle space.

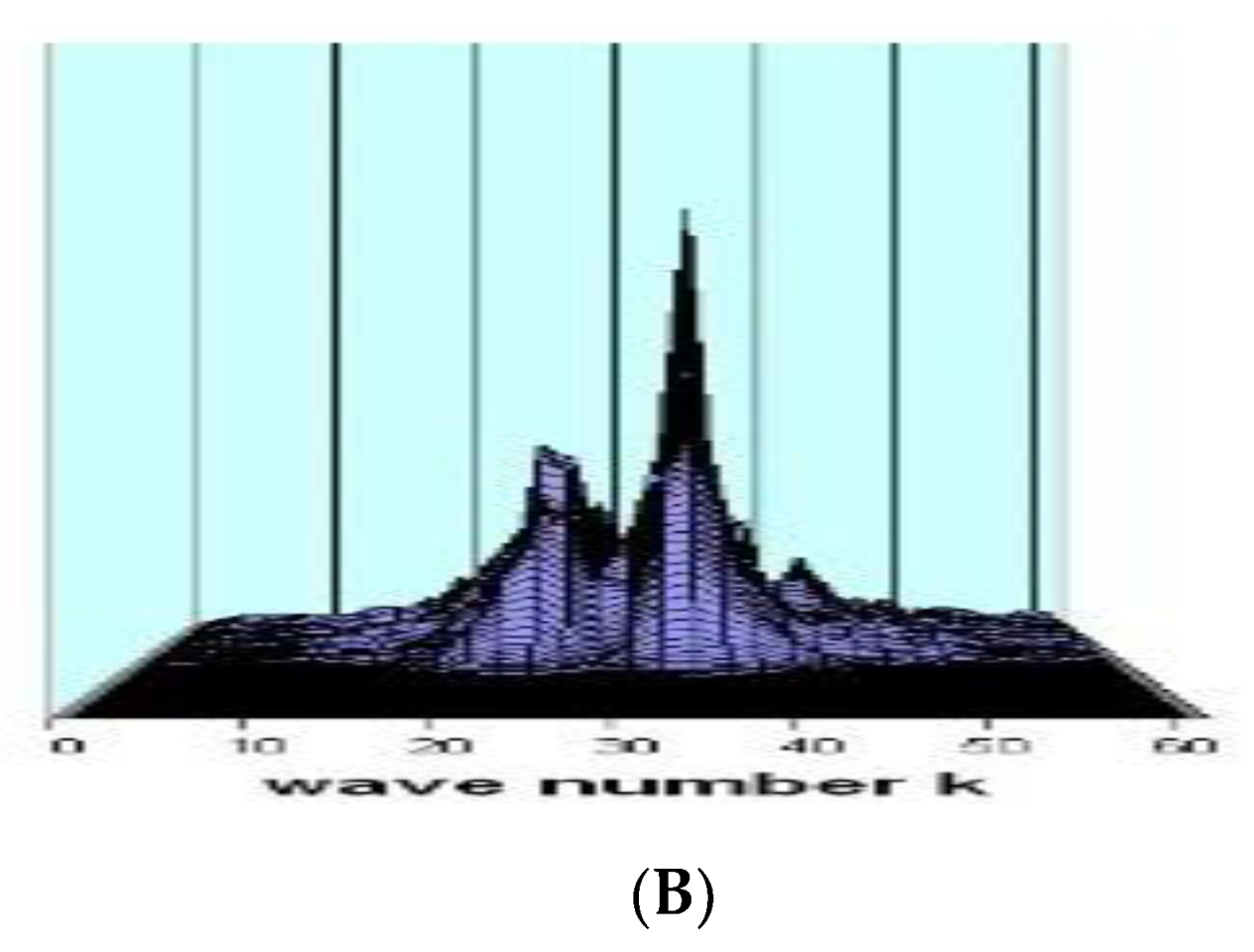

Figure 3 depicts the influence the delay has:

Figure 3.

An example of a contour plot showing the spectral intensity against delay for a set of studies with constant delay after stimulation (80 decay periods). The remaining variables are the same as those in the figures that came before.

Figure 3.

An example of a contour plot showing the spectral intensity against delay for a set of studies with constant delay after stimulation (80 decay periods). The remaining variables are the same as those in the figures that came before.

The preferred wavelength when just one wave is growing is a (decreasing) function of delay; altering the delay reorganizes the neurons into a subset that they were previously arranged into. Because the linked group is reconstituted (almost exactly) upon repeating a value of T, this procedure can be compared to a memory search. Regarding the theories of memory storage, we remain neutral and do not make any assumptions about the relationship between the waves and semantic content. However, since our simplistic model closely resembles the real cortex, these theories need to account for activity waves, which are the corresponding resonant modes.

9. Conclusion: Resonance Signatures Allow Us to Adapt and Effectively Interact with Our Environment

A multitude of delays and ensuing rhythms are possible due to the human cortex's six layers. There is currently no explanation for the different electroencephalographic frequency bands' origins [

68,

69]. It is evident that the current theory directly addresses that issue.

The random placement of the initial stimulus matters when two waves are produced because the location of the irregular wave pattern is fixed only with respect to the origin. As a result, there are a wide variety of potential neuronal firing patterns in these situations. If each subset of individual cortical cells reflects a distinct thought, then, in the spirit of the continuum analysis, wherein cells are divided into components, there are comparatively fewer, but still a great number of possibilities. For roughly 20 billion cortical cells, there are about 106 billion such possibilities.

The way in which these patterns are "decoded" into a combination of recollections of past memories and the semantic content of different wave-memories or conscious awareness is not explained by this theory. It might, however, provide as an illustration of how cognitive research can benefit from the study of brain tissue as organized resonating media.

It is probable that each part of our brain and body has its own resonance signature. These signals can fluctuate subtly from moment to moment, possibly fluctuating around the average frequency value. It has been hypothesized that the major cause of conscious experiences is the process by which our brains learn new knowledge about an ever-changing reality during our entire lives. Developing resonant states between top-down and bottom-up processes, learning top-down expectations, matching them with bottom-up data, and concentrating attention on the predicted information clusters as they come to an attentive consensus between what is expected and what is real in the outside world are some of these processes.

Every conscious experience in the brain is thought to be a resonant condition, and learning, sensation, and the associated cognitive representations are caused by these resonant situations (see Grossberg [

59]). As we gain more knowledge about the environment, our sensory and cognitive representations of it can hold true, according to Grossberg's idea. Our bodies are able to unlearn irrelevant learnt maps as our motor and spatial representations develop from childhood to adulthood. This happens as a result of the brain trying to keep up with the body's changes. We conclude that procedural memories are not conscious because resonance cannot be produced by the inhibitory matching processes that underpin spatial and motor actions. Resonance, then, is the language that enables effective communication with our external and inner environments as well as with other people. Activity waves are the means by which criticality is governed; but what governs that?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This study had employed no data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Tacoma Bridge. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3mclp9QmCGs)[accessed 18 March 2023).

- Bare, J. E. (2001). Resonant Frequency Therapy Device. US Patent 6,221,094, (accessed 16 May, 2023) https://patents.google.com/patent/US5908441A/en).

- Bare, J. E. (1999) Resonant Frequency Therapy Device. US Patent 5,908,441 (accessed 16 May, 2023)(https://patents.google.com/patent/US6221094B1/en).

- Bare, J. E. (2014). Resonant Frequency Therapy Device. US Patent 8,652,184 (accessed 16 May, 2023)(https://patents.google.com/patent/US8652184B2/en).

- Pitt, W. G., (1987). Protein Adsorption On Polyurethanes (FTIR). University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

- Mittelstein, D. R., Ye, J., Schibber, E. F., Roychoudhury, A., Martinez, L. T., Fekrazad, M. H., Ortiz, M., Lee, P. P., Shapiro, M. G. & Gharib, M. (2020). Selective ablation of cancer cells with low intensity pulsed ultrasound. Applied Physics Letters, 116(1), 013701.

- Buckner, C. A., Buckner, A. L., Koren, S. A., Persinger, M. A., & Lafrenie, R. M. (2015). Inhibition of cancer cell growth by exposure to a specific time-varying electromagnetic field involves T-type calcium channels. PLoS One, 10(4), e0124136.

- Kang, C., Li, Y., Novak, D., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Q. & Hu, Y. (2020). Brain networks of maintenance, inhibition and disinhibition during working memory. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 28(7), 1518-1527.

- Leisman, G. (2022). On the Application of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience in Educational Environments. Brain Sciences, 12(11), p.1501.

- Leisman, G., Melillo, R. (2022). Front and center: Maturational dysregulation of frontal lobe functional neuroanatomic connections in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 16.

- Ma, Z., Turrigiano, G. G., Wessel, R. & Hengen, K .B. (2019). Cortical circuit dynamics are homeostatically tuned to criticality in vivo. Neuron, 104(4), 655-664.

- Hebb, D. (1948). The organisation of behavior: a neuropsychological theory.Wiley, New York.

- Koch, P., Leisman, G. (1990). A continuum model of activity waves in layered neuronal networks: computer models of brain-stem seizures. In: Proceedings. Third Annual IEEE Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (pp. 525-531). IEEE.

- Koch, P. & Leisman, G., (2015). Cortical Activity waves are the physical carriers of memory and thought. In 2015 7th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER) (pp. 364-367). IEEE.

- Leisman, G., Koch, P. (2009). Networks of conscious experience: computational neuroscience in understanding life, death, and consciousness. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 20(3-4), 151-176.

- Hammerschlag, R., Jain, S., Baldwin, A.L., Gronowicz, G., Lutgendorf, S. K., Oschman, J. L. & Yount, G. L. (2012). Biofield research: A roundtable discussion of scientific and methodological issues. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(12), 1081-1086.

- Hammerschlag, R., Levin, M., McCraty, R., Bat, N., Ives, J.A., Lutgendorf, S.K. & Oschman, J.L. (2015). Biofield physiology: a framework for an emerging discipline. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 4(1_suppl), pp.gahmj-2015.

- Ho, M. W. (2008). The Rainbow and the Worm: The Physics of Organisms. World Scientific, Singapore.

- Finger, A. M. & Kramer, A. (2021). Mammalian circadian systems: Organization and modern life challenges. Acta Physiologica, 231(3), p.e13548.

- Doelling, K., Herbst, S., Arnal, L. & van Wassenhove, V. (2023). Psychological and neuroscientific foundations of rhythms and timing. London, Oxford.

- Crick, F., & Koch, C. (1990). Towards a neurobiological theory of consciousness. Seminars in the Neurosciences, 2, 263–275.

- Fries, P. (2005). A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 474-480.

- Fries, P. (2015). Rhythms for cognition: communication through coherence. Neuron, 88(1), 220-235.

- Koch, C. (2004). Qualia. Current Biology, 14(13), R496.

- Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the brain: Deciphering how the brain codes our thoughts. Penguin.

- Grossberg, S. T. (2017). Towards solving the hard problem of consciousness: The varieties of brain resonances and the conscious experiences that they support. Neural Networks, 87, 38-95.

- Freeman, W.J. & Vitiello, G. (2006). Nonlinear brain dynamics as macroscopic manifestation of underlying many-body field dynamics. Physics of Life Reviews, 3(2), 93-118.

- Pockett, S. (2000). The Nature of Consciousness: A Hypothesis. Iuniverse, Bloomington.

- Pockett, S. (2012). The electromagnetic field theory of consciousness a testable hypothesis about the characteristics of conscious as opposed to non-conscious fields. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 19(11-12), 191-223.

- Bandyopadhyay, A. (2019). Resonance Chains and New Models of the Neuron. Available at: https://medium.com/@aramis720/resonance-chains-and-new-models-of-the-neuron-7dd82a5a7c3a (accessed 15 May, 2023).

- Sahu, S., Ghosh, S., Ghosh, B., Aswani, K., Hirata, K., Fujita, D. & Bandyopadhyay, A., (2013a). Atomic water channel controlling remarkable properties of a single brain microtubule: correlating single protein to its supramolecular assembly. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 47, 141-148.

- Sahu, S., Ghosh, S., Hirata, K., Fujita, D., & Bandyopadhyay, A. (2013b). Multi-level memory-switching properties of a single brain microtubule. Applied Physics Letters 2013:123701. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. , Ray, K., Fujita, D. & Bandyopadhyay, A., (2019). Complete dielectric resonator model of human brain from MRI data: a journey from connectome neural branching to single protein. In: Engineering Vibration, Communication and Information Processing: (pp. 717-733), Springer, New York.

- Strogatz, S. H. (2012). Sync: How Order Emerges From Chaos in the Universe, Nature, and Daily Life. Hachette, UK.

- Craddock, J. A., Hameroff, T. R., Ayoub, S. T., Klobukowski, M. & Tuszynski, A. (2015). Anesthetics act in quantum channels in brain microtubules to prevent consciousness. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 15(6), 523-533.

- Keppler, J. (2013). A new perspective on the functioning of the brain and the mechanisms behind conscious processes. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 242.

- Hunt, T. (2011). Kicking the psychophysical laws into Gear a new approach to the combination problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18(11-12), 96-134.

- Schooler, J. W., Hunt, T., & Schooler, J. N. (2011). Reconsidering the metaphysics of science from the inside out. Neuroscience, Consciousness and Spirituality, 157-194.

- Hunt, T. (2014). Eco, Ego, Eros: Essays in Philosophy, Spirituality and Science. Aramis Press.

- Goff, P. (2017). Consciousness and Fundamental Reality. Oxford University Press.

- Koch, C. (2014). Ubiquitous minds. Scientific American Mind, 25(1), 26-29.

- Tononi, G., & Koch, C. (2015). Consciousness: here, there and everywhere?.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1668), 20140167.

- Hunt, T. (2020). Calculating the boundaries of consciousness in general resonance theory. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 27(11-12), 55-80.

- Griffin, D. R. (1998). Unsnarling the World-knot: Consciousness, Freedom, and the Mind-body Problem, University of California Press, ISBN 0520209443.

- Hameroff, S. (2010). The “conscious pilot”—dendritic synchrony moves through the brain to mediate consciousness. Journal of Biological Physics, 36, 71-93.

- Jones, M. (2013). Electromagnetic-field theories of mind. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 20(11-12), 124-149.

- McFadden, J. (2002a). Synchronous Firing and its influence on the brain's electromagnetic field. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 9(4), 23-50.

- McFadden, J. (2002). The conscious electromagnetic information (Cemi) field theory: the hard problem made easy? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 9(8), 45-60.

- John, E. R. (2001). A field theory of consciousness. Consciousness and cognition, 10(2), 184-213.

- Wyart, V., & Tallon-Baudry, C. (2008). Neural dissociation between visual awareness and spatial attention. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(10), 2667-2679.

- Whitehead, C. (2010). Cultural distortions of self-and reality-perception. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 17(7-8), 95-118.

- Chapeton, J. I., Haque, R., Wittig, J. H., Inati, S. K., & Zaghloul, K. A. (2019). Large-scale communication in the human brain is rhythmically modulated through alpha coherence. Current Biology, 29(17), 2801-2811.

- Margulis, L., & Sagan, D. (1990). Origins of sex: Three Billion Years of Genetic Recombination. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Zeki, S., & Bartels, A. (1999). Toward a Theory of Visual Consciousness. Consciousness and Cognition, 8(2), 225-259.

- Zeki, S. (2003). The disunity of consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(5), 214.

- Steinke, G. K., & Galán, R. F. (2011). Brain rhythms reveal a hierarchical network organization. PLoS Computational Biology, 7(10), e1002207.

- Hilgetag, C. C., & Goulas, A. (2020). ‘Hierarchy’in the organization of brain networks. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375(1796), 20190319.

- Jiruska, P., De Curtis, M., Jefferys, J. G., Schevon, C. A., Schiff, S. J., & Schindler, K. (2013). Synchronization and desynchronization in epilepsy: controversies and hypotheses. The Journal of Physiology, 591(4), 787-797.

- Grossberg, S. T. (2012). Studies of mind and brain: Neural principles of learning, perception, development, cognition, and motor control (Vol. 70). Springer, New York.

- Aboitiz, F., Montiel, J., Morales, D., & Concha, M. (2002). Evolutionary divergence of the reptilian and the mammalian brains: considerations on connectivity and development. Brain research reviews, 39(2-3), 141-153.

- Wilson, H. R., & Cowan, J. D. (1973). A mathematical theory of the functional dynamics of cortical and thalamic nervous tissue. Kybernetik, 13(2), 55-80.

- Destexhe, A., & Sejnowski, T. J. (2009). The Wilson–Cowan model, 36 years later. Biological cybernetics, 101(1), 1-2.

- Koch, P., & Leisman, G. (1996). Wave theory of large-scale organization of cortical activity. International journal of neuroscience, 86(3-4), 179-196.

- Golomb, D., & Amitai, Y. (1997). Propagating neuronal discharges in neocortical slices: computational and experimental study. Journal of neurophysiology, 78(3), 1199-1211.

- Ermentrout, B. (1998). The analysis of synaptically generated traveling waves. Journal of computational neuroscience, 5, 191-208.

- Koch, P., & Leisman, G. (2001). Effect of local synaptic strengthening on global activity-wave growth in the hippocampus. International journal of neuroscience, 108(1-2), 127-146.

- Koch, P., & Leisman, G. (2006). Typology of nonlinear activity waves in a layered neural continuum. International journal of neuroscience, 116(4), 381-405.

- Buzsaki, G. (2006). Rhythms of the Brain. Oxford university press.

- Neymotin, S. A., Lee, H., Park, E., Fenton, A. A., & Lytton, W. W. (2011). Emergence of physiological oscillation frequencies in a computer model of neocortex. Frontiers in computational neuroscience, 5, 19.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).