Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

17 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and experimental population

2.2. Blood sampling for AMH

2.3. SNP data and quality control

2.4. Genome-wide association study (GWAS)

2.5. Multiple testing adjustment

2.6. Validation population

2.7. Reproductive management

2.8. Physiological traits and climatic data

2.9. SNP marker genotyping

2.10. Statistics for the validation analysis

3. Results

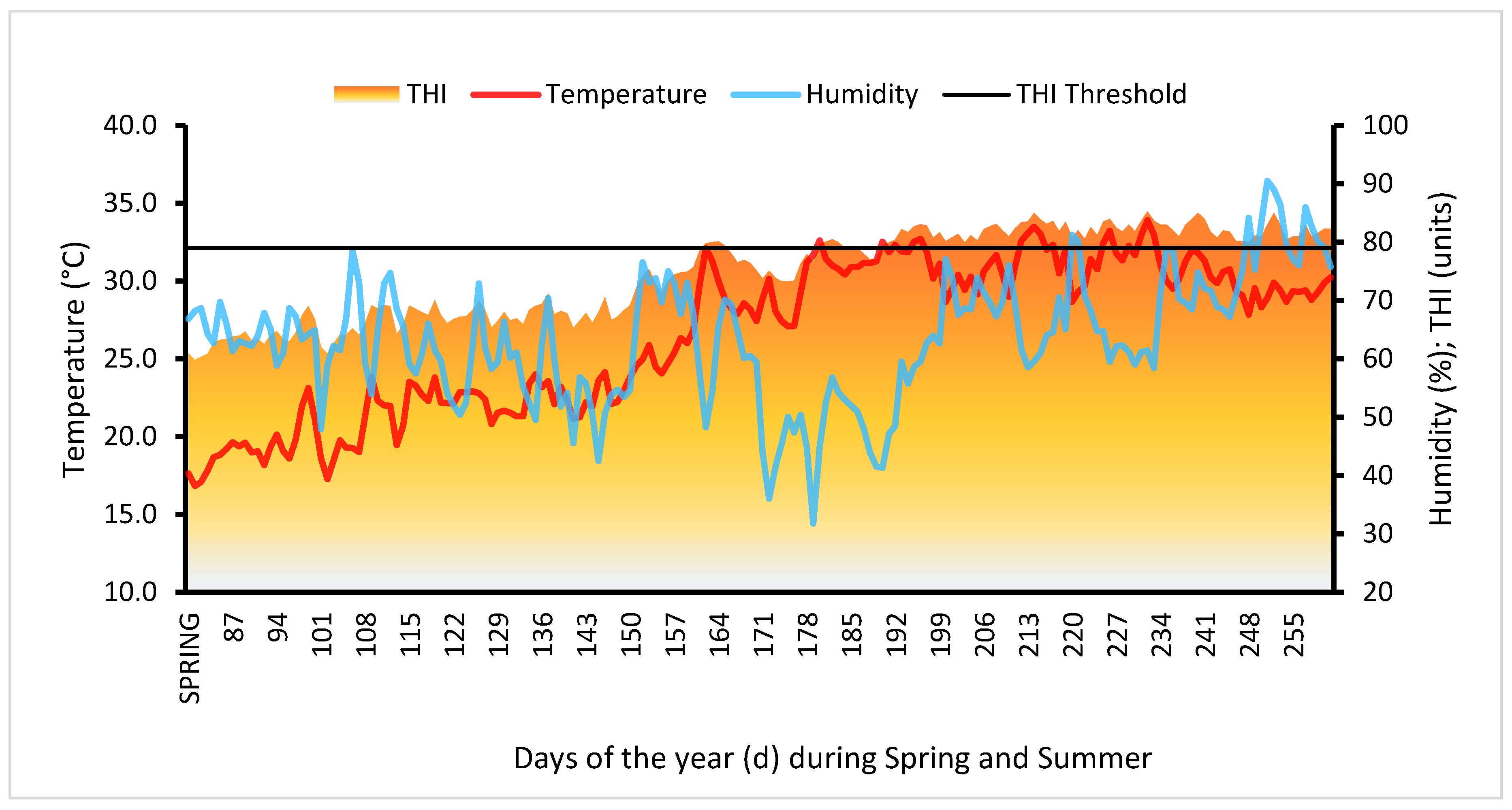

3.1. Climate and AMH sampling

3.2. AMH as endocrine marker during summer

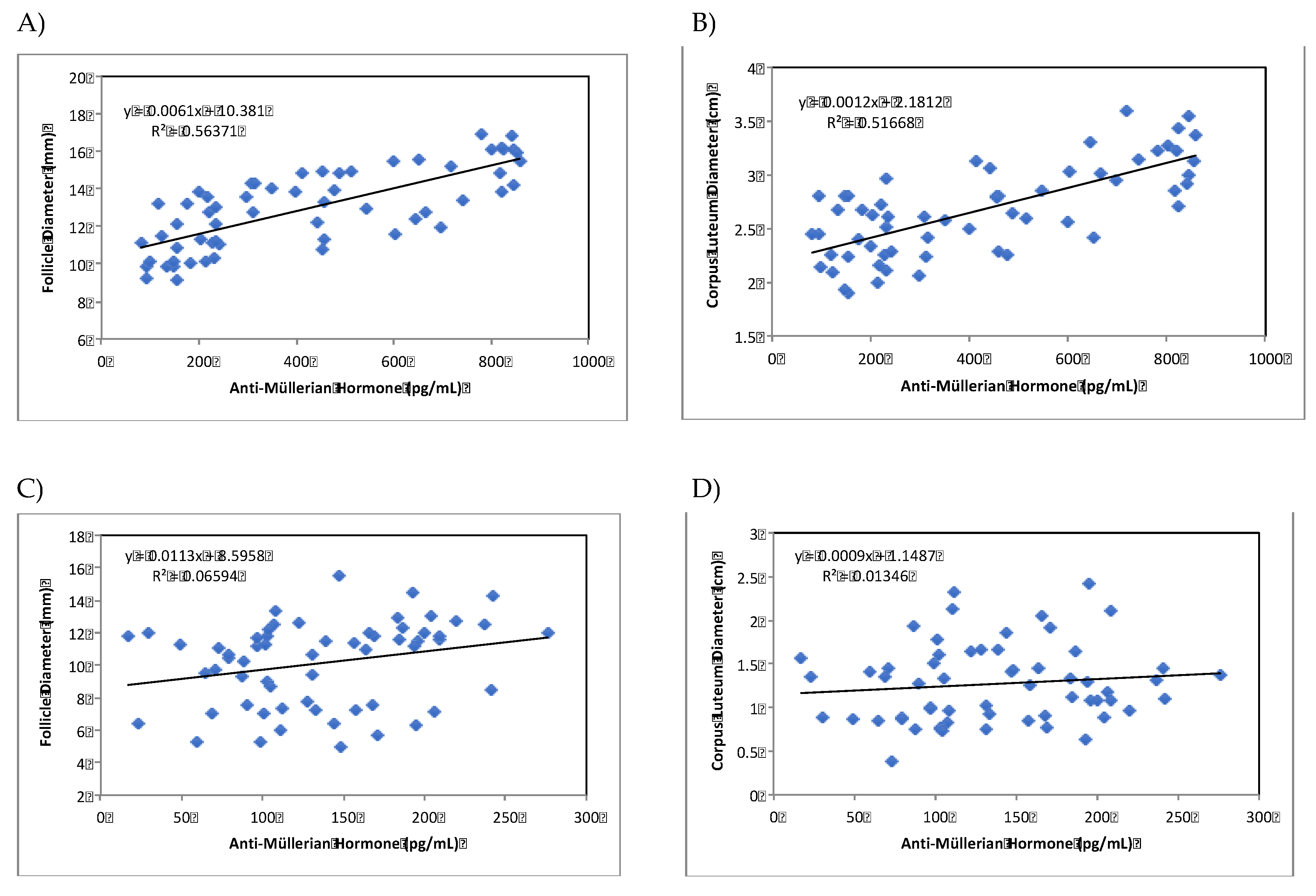

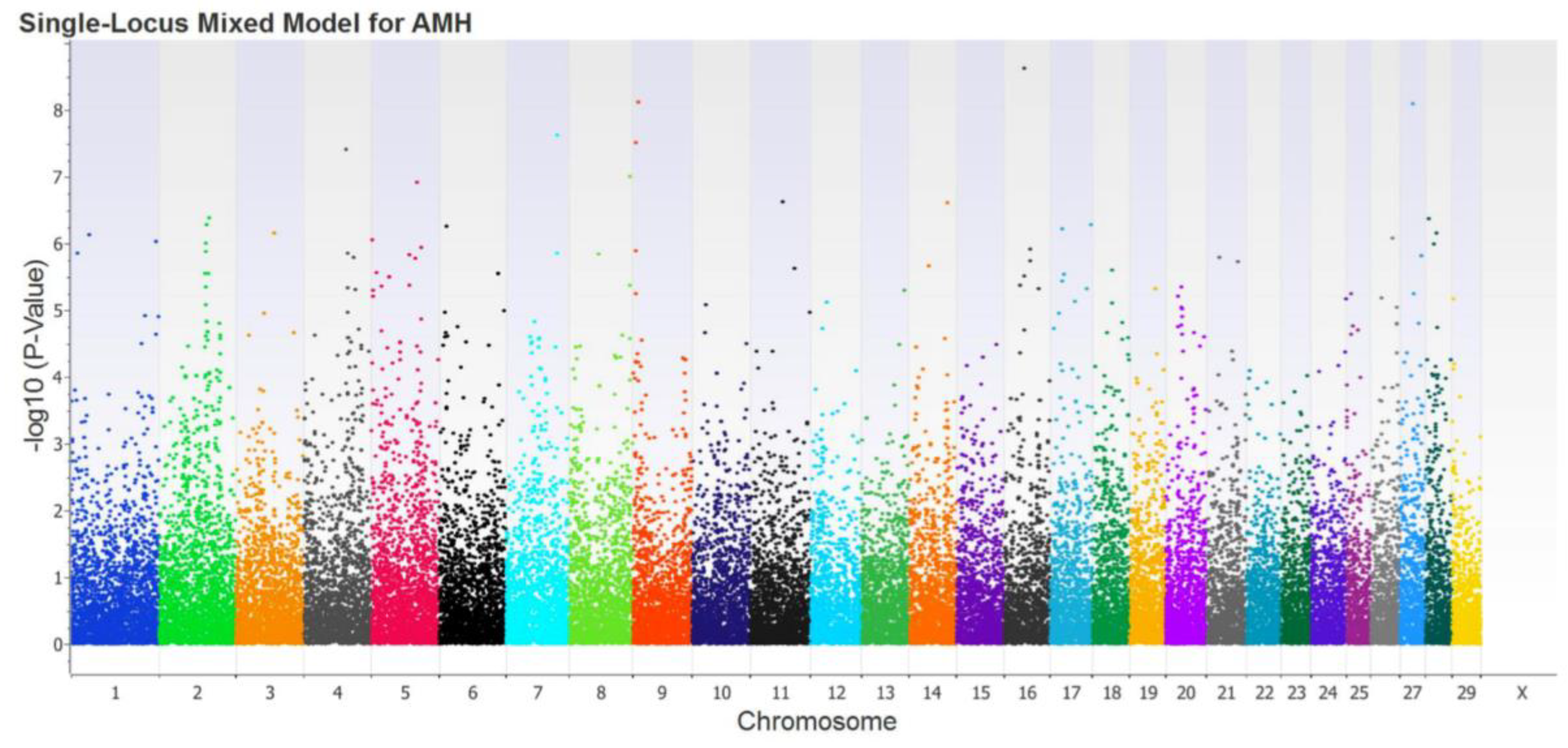

3.1. Genome-wide association study

3.2. SNPs selection

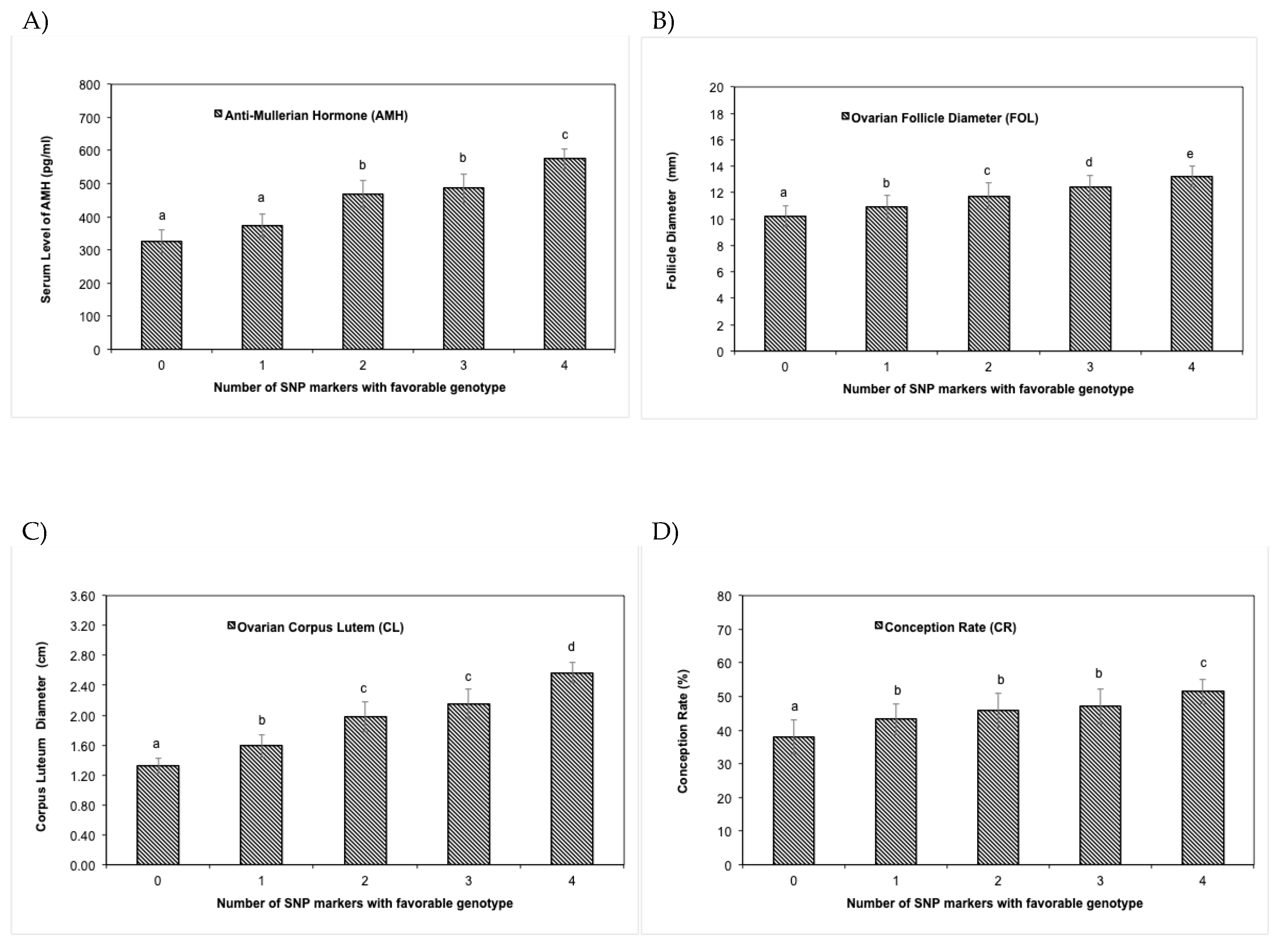

3.3. SNP markers validation

3.4. SNP effects on reproductive phenotypes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cole, J.B.; VanRaden, P.M. Symposium review: Possibilities in an age of genomics: The future of selection indices. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3686–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, S.T. Genetic control of reproduction in dairy cows. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2013, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglior, F.; Fleming, A.; Malchiodi, F.; Brito, L.F.; Martin, P.; Baes, C.F. A 100-Year Review: Identification and genetic selection of economically important traits in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10251–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, J.E.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Axford, M.; Nieuwhof, G.; Shaffer, M. Symposium review: Building a better cow-The Australian experience and future perspectives. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3702–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomasen, J.R.; Willam, A.; Egger-Danner, C.; Sørensen, A.C. Reproductive technologies combine well with genomic selection in dairy breeding programs. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, P.D.; Santos, V.G.; Giordano, J.O.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Fricke, P.M. Development of fertility programs to achieve high 21-day pregnancy rates in high-producing dairy cows. Theriogenology 2018, 1, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucy, M.C. Symposium review: Selection for fertility in the modern dairy cow-Current status and future direction for genetic selection. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3706–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häggman, J.; Christensen, J.M.; Mäntysaari, E.A.; Juga, J. Genetic parameters for endocrine and traditional fertility traits, hyperketonemia and milk yield in dairy cattle. Animal 2019, 13, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, M.A.; Hostens, M.; Opsomer, G. Reproductive management in dairy cows—the future. Ir. Vet. J. 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Krassel, F.; Scheetz, D.M.; Neuder, L.M.; Ireland, J.L.; Pursley, J.R.; Smith, G.W.; Tempelman, R.J.; Ferris, T.; Roudebush, W.E.; Mossa, F.; et al. Concentration of anti-Müllerian hormone in dairy heifers is positively associated with productive herd life. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 3036–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossa, F.; Ireland, J.J. Physiology and endocrinology symposium: Anti-Müllerian hormone: A biomarker for the ovarian reserve, ovarian function, and fertility in dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobikrushanth, M.; Dutra, P.A.; Bruinjé, T.C.; Colazo, M.G.; Butler, S.T.; Ambrose, D.J. Repeatability of antral follicle counts and anti-Müllerian hormone and their associations determined at an unknown stage of follicular growth and an expected day of follicular wave emergence in dairy cows. Theriogenology 2017, 1, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, M.Y.; Jimenez-Krassel, F.; Steibel, J.P.; Lu, Y.; Baktula, A.; Vukasinovic, N.; Neuder, L.; Ireland, J.L.H.; Ireland, J.J.; Tempelman, R.J. Genomic heritability and genome-wide association analysis of anti-Müllerian hormone in Holstein dairy heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 8063–8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alward, K.J.; Bohlen, J.F. Overview of Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and association with fertility in female cattle. Reprod Domest Anim. 2020, 55, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobikrushanth, M.; Purfield, D.C.; Colazo, M.G.; Butler, S.T.; Wang, Z.; Ambrose, D.J. The relationship between serum anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations and fertility, and genome-wide associations for Anti-Müllerian hormone in Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7563–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, C.A.; Roca, J.; Barranco, I. Editorial: Molecular Biomarkers in Animal Reproduction. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 1, 802187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Simental, J.F.; Peña-Calderón, C.; Avendaño-Reyes, L.; Correa-Calderón, A.; Macías-Cruz, U.; Rodríguez-Borbón, A.; Leyva-Corona, J.C.; Rivera-Acuña, F.; Thomas, M.G.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Predictive markers for superovulation response and embryo production in beef cattle managed in northwest Mexico are influenced by climate. Liv, Sci. 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano-Algandar, R.; Medrano, J.F.; Thomas, M.G.; Enns, R.M.; Speidel, S.E.; Sánchez-Castro, M.A.; Luna-Nevárez, G.; Leyva-Corona, J.C.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Genetic markers associated with milk production and thermotolerance in Holstein dairy cows managed in a heat-stressed environment. Biology 2023, 12, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfenson, D.; Roth, Z. Impact of heat stress on cow reproduction and fertility. Anim. Front. 2018, 9, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.J. Exploitation of genetic and physiological determinants of embryonic resistance to elevated temperature to improve embryonic survival in dairy cattle during heat stress. Theriogenology 2007, 68 (Suppl 1), S242–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendelman, M.; Aroyo, A.; Yavin, S.; Roth, Z. Seasonal effects on gene expression, cleavage timing, and developmental competence of bovine preimplantation embryos. Reproduction 2010, 140, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, Z.; Hansen, P.J. Disruption of nuclear maturation and rearrangement of cytoskeletal elements in bovine oocytes exposed to heat shock during maturation. Reproduction 2005, 129, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Chiaratti, M.R.; Macabelli, C.H.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Ferraz, M.L.; Watanabe, Y.W.; Smith, L.C.; Meirelles, F.V.; Baruselli, P.S. The infertility of repeat-breeder cows during summer is associated with decreased mitochondrial DNA and increased expression of mitochondrial and apoptotic genes in oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, Z. Effect of heat stress on reproduction in dairy cows: Insights into the cellular and molecular responses of the oocyte. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2017, 5, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R.J.; Zimbelman, R.B.; Rhoads, R.P.; Rhoads, M.L.; Baumgard, L.H. A re- evaluation of the impact of temperature humidity index (THI) and black globe humidity index (BGHI) on milk production in high producing dairy cows. Proc. 24th Annual South. Nut. Man. Conf., Tempe, Arizona, USA 2009, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, T.L.; Johnson, L.J.; Gaughan, J.B. A comprehensive index for assessing environmental stress in animals. J. Anim Sci. 2010, 88, 2153–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Salas, C.A.; Luna-Nevárez, G.; Reyna-Granados, J.R.; Luna-Ramirez, R.I.; Limesand, S.W.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Molecular markers for thermo-tolerance are associated with reproductive and physiological traits in Pelibuey ewes raised in a semiarid environment. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 112, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, B.S. Forensics: Handbook of Statistical Genetics; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, D.S.; Mackay, T.F.C. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics, 4th ed.; Longman Scientific and Technical: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Nevarez, P.; Rincon, G.; Medrano, J.F.; Riley, D.G.; Chase, C.C.Jr.; Coleman, S.W.; VanLeeuwen, D.; DeAtley, K.L.; Islas-Trejo, A.; Silver, G.A.; et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in then growth hormone-insulin like growth factor axis in straightbred and crossbred Angus, Brahman, and Romosinuano heifers: Population genetic analyses and association of genotypes with reproductive phenotypes. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 8, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, C.; Fabre, S.; Médigue, C.; di Clemente, N.; Clément, F.; Bontoux, M.; Touzé, J.L.; Dupont, M.; Briant, E.; Rémy, B.; Beckers, J.F.; et al. Anti-mullerian hormone is an endocrine marker of ovarian gonadotropin-responsive follicles and can help to predict superovulatory responses in the cow. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rensis, F.; Saleri, R.; Garcia-Ispierto, I.; Scaramuzzi, R.; López-Gatius, F. Effects of heat stress on follicular physiology in dairy cows. Animals 2021, 11, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, G.E.; Tao, S.; Laporta, J. Heat stress impacts immune status in cows across the life cycle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Corona, J.C.; Reyna-Granados, J.R.; Zamorano-Algandar, R.; Sanchez-Castro, M.A.; Thomas, M.G.; Enns, R.M.; Speidel, S.E.; Medrano, J.F.; Rincon, G.; Luna-Nevarez, P. Polymorphisms within the prolactin and growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 functional pathways associated with fertility traits in Holstein cows raised in a hot-humid climate. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2018, 50, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monniaux, D.; Drouilhet, L.; Rico, C.; Estienne, A.; Jarrier, P.; Touzé, J.; Sapa, J.; Phocas, F.; Dupont, J.; Dalbiès-Tran, R.; Fabre, S. Regulation of anti-Müllerian hormone production in domestic animals. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2012, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.S.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Lima, F.S.; Greco, L.F.; Morrison, A.; Kumar, A.; Thatcher, W.W.; Santos, J.E.P. Plasma anti-Müllerian hormone in adult dairy cows and associations with fertility. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 6888–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.H.; Carvalho, P.D.; Rozner, A.E.; Vieira, L.M.; Hackbart, K.S.; Bender, R.W.; Dresch, A.R.; Verstegen, J.P.; Shaver, R.D.; Wiltbank, M.C. Relationship between circulating anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and superovulatory response of high-producing dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobikrushanth, M.; Purfield, D.C.; Canadas, E.R.; Herlihy, M.M.; Kenneally, J.; Murray, M.; Kearney, F.J.; Colazo, M.G.; Ambrose, D.J.; Butler, S.T. Anti-Müllerian hormone in grazing dairy cows: Identification of factors affecting plasma concentration, relationship with phenotypic fertility, and genome-wide associations. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 11622–11635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Chakravarty, A.K.; Singh, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Singh, M.; Yousuf, S. Effect of heat stress on reproductive performances of dairy cattle and buffaloes: A review. Vet. World. 2016, 9, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.L.; Bignardi, A.B.; Pereira, R.J.; Stefani, G.; El Faro, L. Genetics of heat tolerance for milk yield and quality in Holsteins. Animal 2017, 11, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succu, S.; Sale, S.; Ghirello, G.; Ireland, J.J.; Evans, A.C.O.; Atzori, A.S.; Mossa, F. Exposure of dairy cows to high environmental temperatures and their lactation status impairs establishment of the ovarian reserve in their offspring. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11957–11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamp, O.; Derno, M.; Otten, W.; Mielenz, M.; Nürnberg, G.; Kuhla, B. Metabolic heat stress adaption in transition cows: Differences in macronutrient oxidation between late-gestating and early-lactating German Holstein dairy cows. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaton, C.; Schenkel, F.S.; Sargolzaei, M.; Cánovas, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Malchiodi, F.; Price, C.A.; Baes, C.; Miglior, F. Genome-wide association study and in silico functional analysis of the number of embryos produced by Holstein donors. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7248–7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Marca, A.; Volpe, A. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in female reproduction: Is measurement of circulating AMH a useful tool? Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2006, 64, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastora, S.L.; Triantafyllidou, O.; Kolovos, G.; Kastoras, A.; Sigalos, G.; Vlahos, N. Combinational approach of retrospective clinical evidence and transcriptomics highlight AMH superiority to FSH, as successful ICSI outcome predictor. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Nevárez, G.; Pendleton, A.L.; Luna-Ramirez, R.I.; Limesand, S.W.; Reyna-Granados, J.R.; Luna-Nevárez, P. Genome-wide association study of a thermo-tolerance indicator in pregnant ewes exposed to an artificial heat-stressed environment. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 101, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobikrushanth, M.; Purfield, D.C.; Colazo, M.G.; Wang, Z.; Butler, S.T.; Ambrose, D.J. The relationship between serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) concentration and reproductive performance, and genome-wide associations for serum IGF-1 in Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 9154–9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, A.P.O.; Barros, V.R.P.; Santos, J.M.; Menezes, V.G.; Cavalcante, A.Y.P.; Gouveia, B.B.; Bezerra, M.E.S.; Macedo, T.J.S.; Matos, M.H.T. Immunohistochemical localization of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in the sheep ovary and the synergistic effect of IGF-1 and FSH on follicular development in vitro and LH receptor immunostaining. Theriogenology 2019, 129, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Shang, W.; Zeng, S. Effects of IGF-1 on the three-dimensional culture of ovarian preantral follicles and superovulation rates in mice. Biology 2022, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T. Molecular and cellular mechanisms for the regulation of ovarian follicular function in cows. J. Reprod. Dev. 2016, 62, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, H.C.; Antonia, R.J.; Baldwin, A.S. PI3K/Akt promotes feedforward mTORC2 activation through IKKα. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 21064–21075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roith, D. The insulin-like growth factor system. Exp. Diabesity Res. 2003, 4, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.B.; Dixit, M.; Neginskaya, M.; Nagaraj, K.; Pavlov, E.; Werner, H.; Yakar, S. Effects of GH/IGF on the aging mitochondria. Cells 2020, 9, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, S.S.; Naranjo-Gomez, J.S.; Rondón-Barragán, I.S. Thermoprotective molecules: Effect of insulin-like growth factor type I (IGF-1) in cattle oocytes exposed to high temperatures. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascari, I.J.; Alves, N.G.; Jasmin, J.; Lima, R.R.; Quintão, C.C.R.; Oberlender, G.; Moraes, E.A.; Camargo, L.S.A. Addition of insulin-like growth factor I to the maturation medium of bovine oocytes subjected to heat shock: Effects on the production of reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial activity and oocyte competence. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2017, 60, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.S.; Risolia, P.H.B.; Ispada, J.; Assumpção, M.E.O.A.; Visintin, J.A.; Orlandi, C.; Paula-Lopes, F.F. Role of insulin-like growth factor 1 on cross-bred Bos indicus cattle germinal vesicle oocytes exposed to heat shock. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Hao, H.; Du, W.; Pang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zou, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, X. Supplementation of EGF, IGF-1, and connexin 37 in IVM medium significantly improved the maturation of bovine oocytes and vitrification of their IVF blastocysts. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesken-Nikitin, A.; Hwang, C.I.; Cheng, C.Y.; Michurina, T.V.; Enikolopov, G.; Nikitin, A.Y. Ovarian surface epithelium at the junction area contains a cancer-prone stem cell niche. Nature 2013, 495, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Terakawa, J.; Clevers, H.; Barker, N.; Daikoku, T.; Dey, S.K. Ovarian LGR5 is critical for successful pregnancy. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2380–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jackson, L.; Dey, S.K.; Daikoku, T. In pursuit of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor-5 regulation and function in the uterus. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 5065–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lau, W.; Barker, N.; Low, T.Y.; Koo, B.K.; Li, V.S.; Teunissen, H.; Kujala, P.; Haegebarth, A.; Peters, P.J.; van de Wetering, M.; et al. Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 2011, 476, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Luo, H.; Yang, M.; Augustino, S.M.A.; Wang, D.; Mi, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genetic parameters and weighted single-step genome-wide association study for supernumerary teats in Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 11867–11877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risha, M.A.; Ali, A.; Siengdee, P.; Trakooljul, N.; Haack, F.; Dannenberger, D.; Wimmers, K.; Ponsuksili, S. Wnt signaling related transcripts and their relationship to energy metabolism in C2C12 myoblasts under temperature stress. PeerJ 2021, 14, e11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlebacher, A. Mechanisms of T cell tolerance towards the allogeneic fetus. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.Y.; Moldenhauer, L.M.; Groome, H.M.; Schjenken, J.E.; Robertson, S.A. Toll-like receptor-4 null mutation causes fetal loss and fetal growth restriction associated with impaired maternal immune tolerance in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.A.; Care, A.S.; Moldenhauer, L.M. Regulatory T cells in embryo implantation and the immune response to pregnancy. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 4224–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial toxins in sepsis: A brief review. Virulence 2014, 5, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittebole, X.; Castanares-Zapatero, D.; Laterre, P.F. Toll-like receptor 4 modulation as a strategy to treat sepsis. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 2010, 568396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Lun, J.C.; He, Y.M.; Tang, L.P. Heat stress inhibits TLR4-NF-κB and TLR4-TBK1 signaling pathways in broilers infected with Salmonella Typhimurium. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Xu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Su, L. NF-κB signaling is essential for resistance to heat stress-induced early stage apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ezernieks, V.; Wang, J.; Arachchillage, N.W.; Garner, J.B.; Wales, W.J.; Cocks, B.G.; Rochfort, S. Heat stress in dairy cattle alters lipid composition of milk. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faylon, M.P.; Baumgard, L.H.; Rhoads, R.P.; Spurlock, D.M. Effects of acute heat stress on lipid metabolism of bovine primary adipocytes. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 8732–8740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.J. Reproductive physiology of the heat-stressed dairy cow: Implications for fertility and assisted reproduction. Anim. Reprod. 2019, 16, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Bowman, P.J.; Haile-Mariam, M.; Pryce, J.E.; Hayes, B.J. Genomic selection for tolerance to heat stress in Australian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2849–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, J.I.; Song, J.Z.; Heyen, D.W.; Lewin, H.A.; Ron, M. A new approach to the problem of multiple comparisons in the genetic dissection of complex traits. Genetics 1998, 150, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minozzi, G.; Nicolazzi, E.L.; Stella, A.; Biffani, S.; Negrini, R.; Lazzari, B.; Ajmone-Marsan, P.; Williams, J.L. Genome wide analysis of fertility and production traits in Italian Holstein cattle. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, P.M. Sizing up human height variation. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 489–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, E.K.; Baranowska, I.; Wade, C.M.; Salmon-Hillbertz, N.H.; Zody, M.C.; Anderson, N.; Biagi, T.M.; Patterson, N.; Pielberg, G.R.; Kulbokas, E.J.; et al. Efficient mapping of Mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Moderate heat stress (n=152; THI = 72-79) |

Severe heat stress (n=128; THI > 79) |

|---|---|---|

| AMH (ng/ml) | 417.26 ± 4.51 a | 136.94 ± 4.03 b |

| FOL (mm) | 12.95 ± 0.93 a | 10.15 ± 1.02 b |

| CL (cm) | 2.68 ± 0.02 a | 1.26 ± 0.04 b |

| CR (%) | 52.63 a | 37.50 b |

| RT (°C) | 38.21 ± 1.25 a | 38.73 ± 3.05 b |

| RR (breaths/min) | 63.35 ± 3.14 a | 67.14 ± 4.96 b |

| Variable | Moderate HS (p-value) | Severe HS (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| FOL (mm) CL (cm) RT (°C) RR (breaths/min) |

0.7508 (<0.0001) 0.7188 (<0.0001) 0.3427 (0.0142) 0.2135 (0.1938) |

0.2567 (0.0837) 0.1160 (0.2155) 0.0958 (0.2671) 0.0634 (0.5728) |

| SNP ID 1 | Variant 2 | BTA 3 | Position 4 | Gene 5 | Alleles 6 | Var 7 | p-Value 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs41807005 | Intergenic | 16 | 34′845050 | -------- | T/C | 0.162 | 2.35 × 10−9 |

| rs109740021 | Intergenic | 9 | 9′329501 | -------- | A/G | 0.157 | 7.53 × 10−9 |

| rs42416336 | Intronic | 27 | 23′354986 | LONRF1 | A/C | 0.152 | 8.16 × 10−9 |

| rs876084180 | Intronic | 7 | 21′401999 | AMH | A/C | 0.143 | 2.38 × 10−8 |

| rs136263395 | Intergenic | 9 | 4′423733 | -------- | T/C | 0.141 | 3.11 × 10−8 |

| rs445674221 | Intronic | 4 | 76′133069 | IGFBP1 | A/G | 0.139 | 3.85 × 10−8 |

| rs8193046 | Intronic | 8 | 108′833985 | TLR4 | T/C | 0.131 | 9.86 × 10−8 |

| rs42849475 | Intronic | 5 | 1′087211 | LGR5 | A/G | 0.129 | 1.20 × 10−7 |

| rs42338999 | Intergenic | 11 | 58′684365 | -------- | T/C | 0.124 | 2.38 × 10−7 |

| rs135450328 | Intergenic | 14 | 68′794329 | -------- | A/C | 0.123 | 2.46 × 10−7 |

| rs478504266 | Intronic | 2 | 89’091847 | SGO2 | G/A | 0.119 | 4.15 × 10−7 |

| rs137194049 | Intronic | 28 | 4′632166 | DISC1 | T/C | 0.118 | 4.24 × 10−7 |

| rs135441773 | Intronic | 2 | 84′744596 | SLC39A10 | T/G | 0.117 | 5.22 × 10−7 |

| rs110893810 | Intronic | 17 | 73′804897 | RSPH14 | T/C | 0.116 | 5.24 × 10−7 |

| rs136745124 | Intergenic | 6 | 12′650752 | -------- | A/G | 0.115 | 5.49 × 10−7 |

| rs43475092 | Intergenic | 3 | 68′078177 | -------- | T/C | 0.114 | 7.04 × 10−7 |

| SNP ID 1 | Gene 2 | F. Allele 3 | Allele Frequency 4 | HWE Test 5 | HWE p-Value 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | C | |||||

| rs876084180 | AMH | T | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| A | G | |||||

| rs445674221 | IGFBP1 | T | 0.53 | 0.47 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| rs42849475 | LGR5 | T | 0.24 | 0.76 | 1.25 | 0.31 |

| rs8193046 | TLR4 | T | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.86 | 0.39 |

| SNP ID 1 | Trait 2 | Least-Square Means by Genotype ± SE 3 | p-Value 4 | AlleleSE | AdditiveFE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AC | CC | |||||

| rs876084180 | AMH | 501.26 ± 45.3 a | 382.49 ± 37.9 b | 152.94 ± 19.2 c | <0.0001 | 165.12 | 174.16* |

| FOL | 13.01 ± 1.06 a | 11.95 ± 1.04 b | 10.17 ± 0.98 c | 0.0010 | 1.37 | 1.42* | |

| CL | 2.53 ± 0.17 a | 1.92 ± 0.16 ab | 1.47 ± 0.19 b | 0.0086 | 0.50 | 0.53* | |

| CR | 45.20 ± 3.67 a | 36.75 ± 3.32 a | 40.65 ± 4.01 a | 0.6519 | 2.21 | 2.27 | |

| AA | AG | GG | |||||

| rs445674221 | AMH | 141.80 ± 19.6 a | 267.39 ± 23.2 a | 442.65 ± 37.8 b | 0.0009 | 146.01 | 150.42* |

| FOL | 10.63 ± 0.96 a | 11.04 ± 1.05 a | 13.91 ± 1.12 b | 0.0068 | 1.60 | 1.64* | |

| CL | 1.24 ± 0.09 a | 1.82 ± 0.07 b | 2.89 ± 1.18 c | 0.0087 | 0.72 | 0.77* | |

| CR | 34.50 ± 0.47 a | 45.15 ± 0.46 b | 56.25 ± 0.42 c | <0.0001 | 10.55 | 10.87* | |

| rs42849475 | AMH | 291.55 ± 26.7 a | 342.16 ± 37.5 a | 401.29 ± 39.2 a | 0.1506 | 52.76 | 54.87* |

| FOL | 9.86 ± 0.87 a | 11.16 ± 1.09 b | 12.64 ± 1.26 b | 0.0079 | 1.34 | 1.39* | |

| CL | 1.38 ± 0.07 a | 1.92 ± 1.05 b | 2.24 ± 1.90 b | 0.0096 | 0.38 | 0.43* | |

| CR | 39.70 ± 3.07 a | 46.20 ± 3.59 b | 50.25 ± 4.36 b | 0.0188 | 4.91 | 5.27* | |

| rs8193046 | AMH | 474.67 ± 38.7 a | 379.23 ± 37.3 b | 158.34 ± 14.2 c | <0.0001 | 151.78 | 158.16* |

| FOL | 13.28 ± 1.29 a | 11.37 ± 0.94 b | 10.14 ± 0.94 c | 0.0065 | 1.52 | 1.57* | |

| CL | 2.71 ± 2.02 a | 1.86 ± 1.45 b | 1.20 ± 1.08 c | 0.0012 | 0.67 | 0.75* | |

| CR | 54.15 ± 3.67 a | 45.70 ± 3.29 a | 36.75 ± 3.18 b | 0.0034 | 8.45 | 8.70* | |

| SNP ID 1 | Trait 2 | Least-Square Means by Genotype ± SE 3 | p-Value 4 | Allele SE | Additive FE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AC | CC | |||||

| rs876084180 | RT | 38.14 ± 2.98 a | 38.25 ± 2.67 a | 38.79 ± 3.39 b | 0.0316 | -0.28 | 0.32* |

| RR | 63.67 ± 5.22 a | 65.44 ± 5.19 a | 66.35 ± 5.19 a | 0.0928 | -1.63 | 1.69* | |

| AA | AG | GG | |||||

| rs445674221 | RT | 38.89 ± 3.02 a | 38.46 ± 2.96 b | 38.15 ± 2.77 c | 0.0094 | -0.34 | 0.37* |

| RR | 68.32 ± 4.98 a | 65.01 ± 4.67 b | 61.96 ± 4.12 c | 0.0067 | -3.06 | 3.18* | |

| rs42849475 | RT | 38.81 ± 3.54 a | 38.39 ± 2.69 b | 38.26 ± 3.82 b | 0.0235 | -0.24 | 0.27* |

| RR | 65.79 ± 4.28 a | 64.03 ± 5.02 a | 62.99 ± 4.67 a | 0.2138 | -1.35 | 1.40* | |

| rs8193046 | RT | 38.16 ± 2.65 a | 38.49 ± 3.08 b | 38.93 ± 3.19 c | 0.0076 | -0.35 | 0.38* |

| RR | 61.24 ± 5.09 a | 64.96 ± 5.16 b | 68.95 ± 4.87 c | 0.0052 | -3.69 | 3.85* | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).