Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

16 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

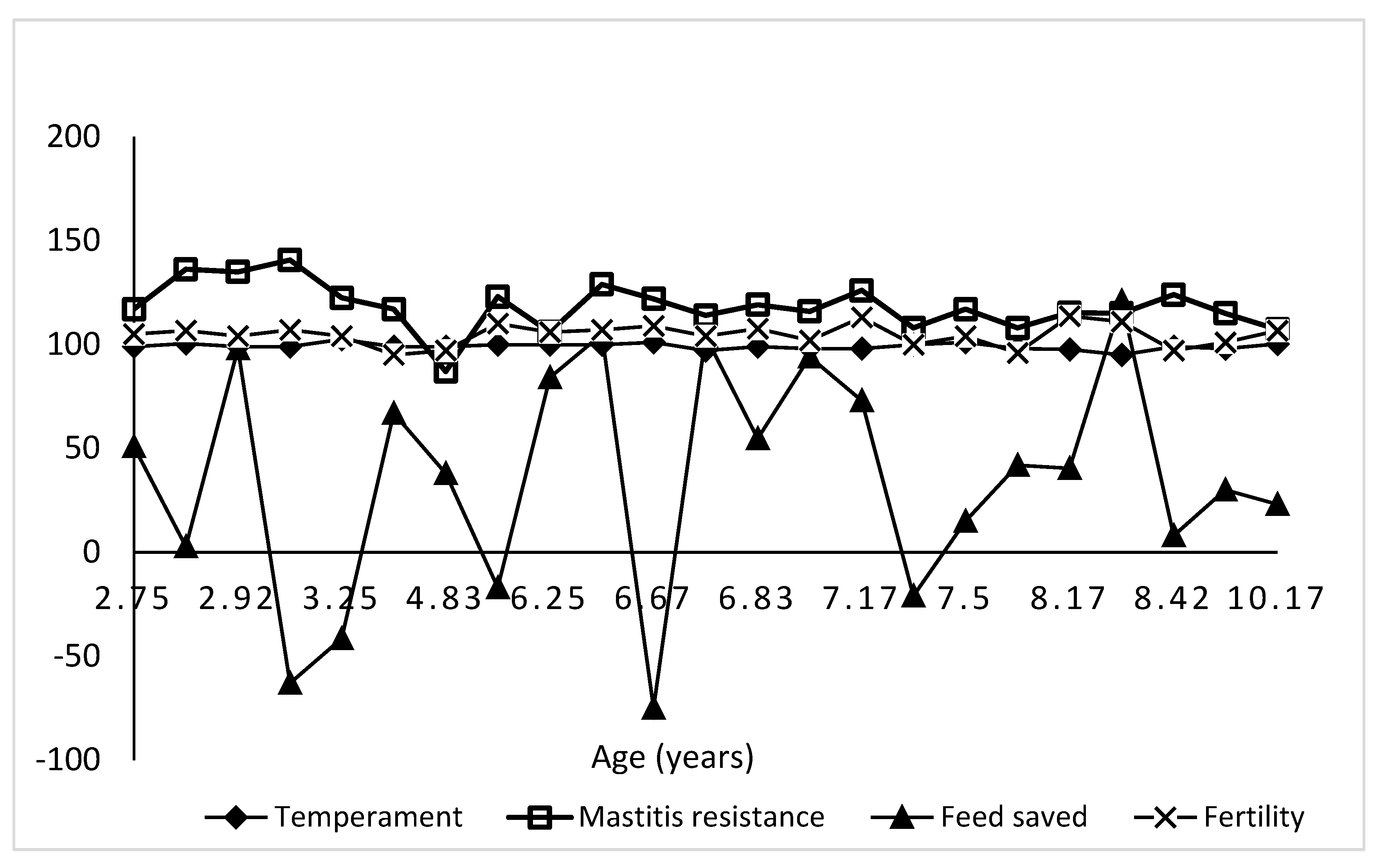

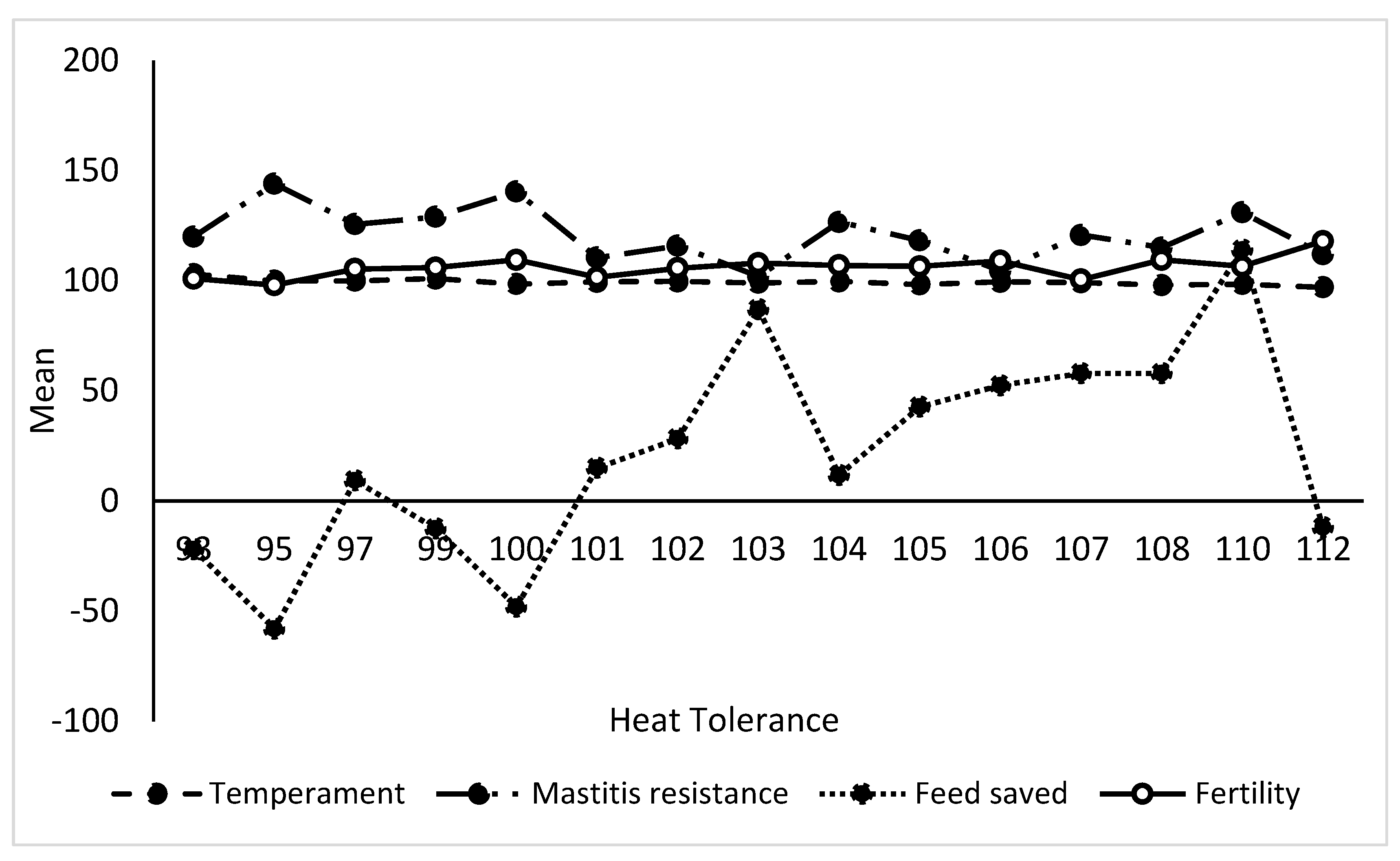

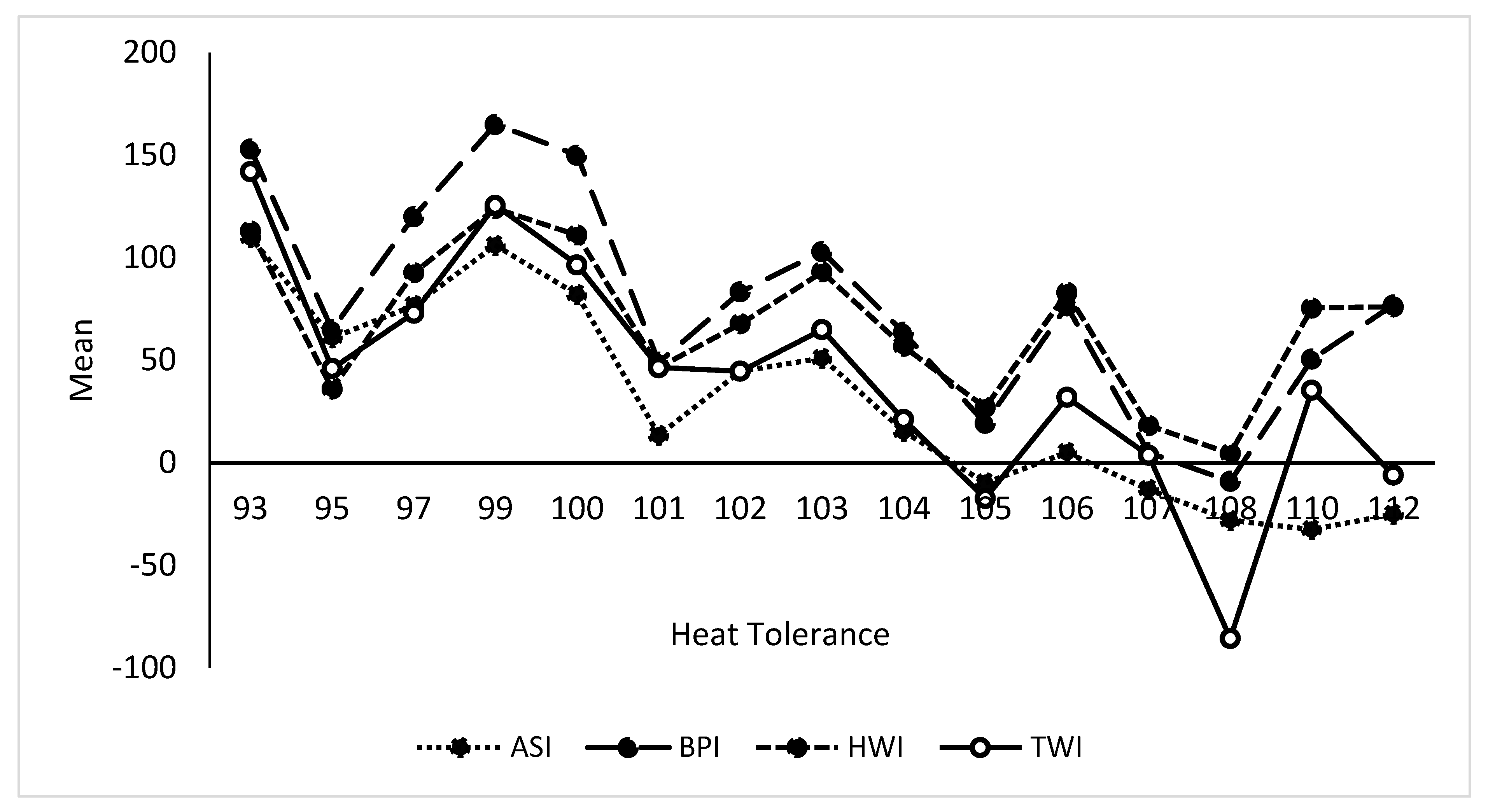

Variation in Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) by relative thermotolerance

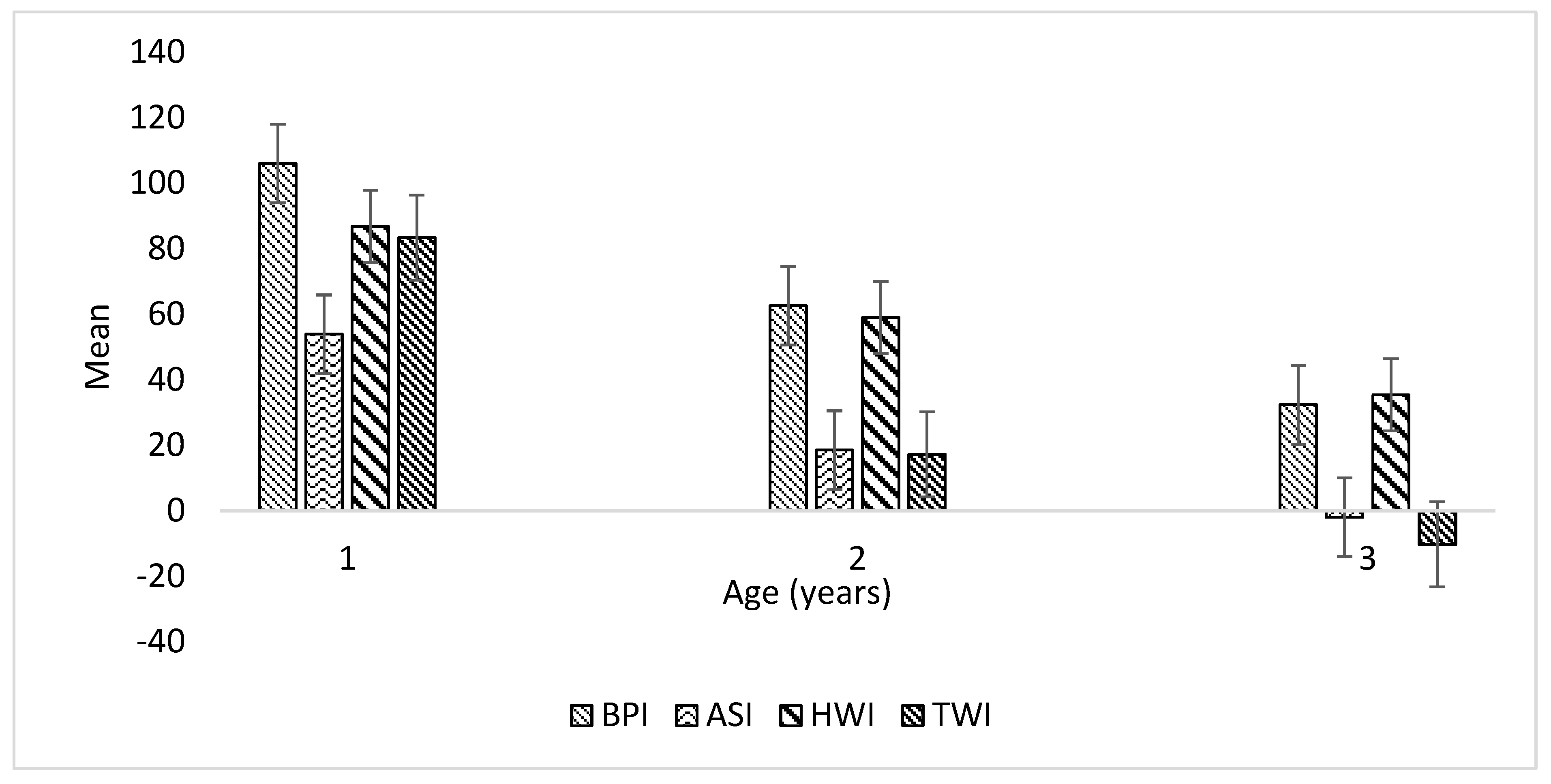

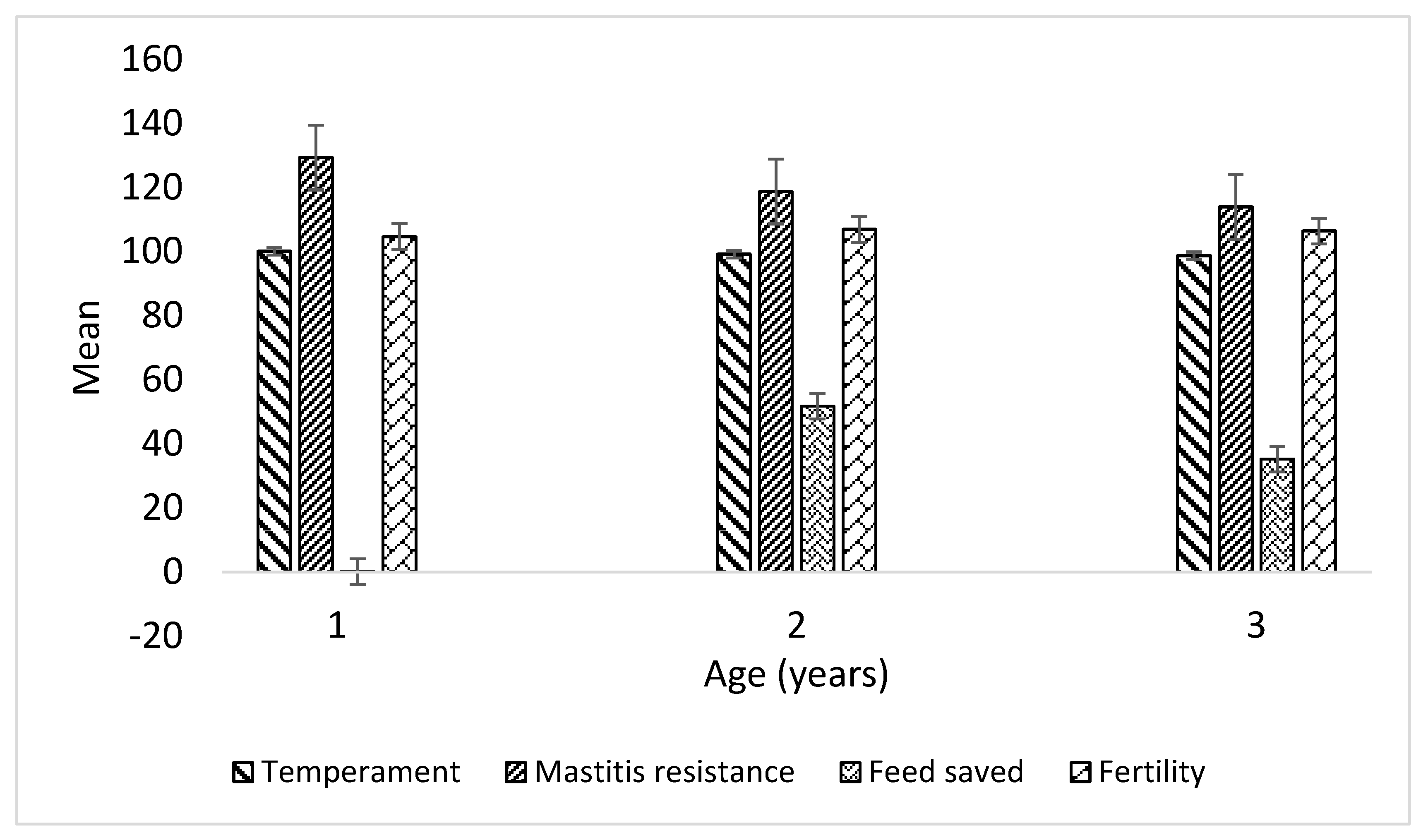

Variation in GEBVs of selection indices by age group

Association of GEBVs of economic traits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AUIBAR, The State of Farm Animal Genetic Resources in Africa. Towards Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation by the Year 2025, ed. B.N. Nouala S, Mbole-Kariuki M, Nengomasha E and Tchangai P. 2019: African Union Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources (AUIBAR), Nairobi, Kenya. 293.

- FAO, et al., The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021-Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. 2021: FAO, Rome,.

- Rojas-Downing, M.M.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Harrigan, T.; Woznicki, S.A. Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, J.; Mutua, J.Y.; Notenbaert, A.M.O.; Marshall, K.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Heat stress will detrimentally impact future livestock production in East Africa. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, J.; Mills, K.E.; Sirovica, L.V.; Sundermann, L.; Bolton, S.E.; von Keyserlingk, M. Public perceptions of potential adaptations for mitigating heat stress on Australian dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5893–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei-Amponsah, R.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; Cheng, L.; Cullen, B.; Joy, A.; Abhijith, A.; Zhang, M.H.; Chauhan, S.S. Heat Stress Impacts on Lactating Cows Grazing Australian Summer Pastures on an Automatic Robotic Dairy. Animals 2020, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.W.; McCarl, B.A.; Jones, J.P.H. An Overview of Mitigation and Adaptation Needs and Strategies for the Livestock Sector. Climate 2017, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, P.H.F.; Wang, Y.; Yan, P.; Oliveira, H.R.; Schenkel, F.S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Brito, L.F. Genetic Diversity and Signatures of Selection for Thermal Stress in Cattle and Other Two Bos Species Adapted to Divergent Climatic Conditions. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 604823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheruiyot, E.; Nguyen, T.; Haile-Mariam, M.; Cocks, B.; Abdelsayed, M.; Pryce, J. Genotype-by-environment (temperature-humidity) interaction of milk production traits in Australian Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2460–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, X.; Hu, L.; Xu, W.; Chu, Q.; Liu, A.; Guo, G.; Liu, L.; Brito, L.F.; Wang, Y. Genomic analyses and biological validation of candidate genes for rectal temperature as an indicator of heat stress in Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4441–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R.; Renquist, B.; Xiao, Y. A 100-Year Review: Stress physiology including heat stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10367–10380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, N.; Cobanov, B.; Schnitkey, G. Economic Losses from Heat Stress by US Livestock Industries. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, E52–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.; Gennari, R.; Dahl, G.; De Vries, A. Economic feasibility of cooling dry cows across the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9931–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laporta, J.; Ferreira, F.; Ouellet, V.; Dado-Senn, B.; Almeida, A.; De Vries, A.; Dahl, G. Late-gestation heat stress impairs daughter and granddaughter lifetime performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 7555–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, G.E.; Tao, S.; Laporta, J. Heat Stress Impacts Immune Status in Cows Across the Life Cycle. Front. Veter- Sci. 2020, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R.J.; Baumgard, L.H.; Zimbelman, R.B.; Xiao, Y. Heat stress: physiology of acclimation and adaptation. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, J.E.; Haile-Mariam, M. Symposium review: Genomic selection for reducing environmental impact and adapting to climate change. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5366–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikmen, S.; Khan, F.A.; Huson, H.J.; Sonstegard, T.S.; Moss, J.I.; Dahl, G.E.; Hansen, P.J. The SLICK hair locus derived from Senepol cattle confers thermotolerance to intensively managed lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5508–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikmen, S.; Mateescu, R.G.; A Elzo, M.; Hansen, P.J. Determination of the optimum contribution of Brahman genetics in an Angus-Brahman multibreed herd for regulation of body temperature during hot weather. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.; Jannaman, E.; Pryce, J.; De Vries, A.; Hansen, P. Effectiveness of the Australian breeding value for heat tolerance at discriminating responses of lactating Holstein cows to heat stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7820–7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmickle, A.T.; Larson, C.C.; Hernandez, F.S.; Pereira, J.M.; Ferreira, F.C.; Haimon, M.L.; Jensen, L.M.; Hansen, P.J.; Denicol, A.C. Physiological responses of Holstein calves and heifers carrying the SLICK1 allele to heat stress in California and Florida dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9216–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Reinoso, M.A.; Aponte, P.M.; Garcia-Herreros, M. Genomic Analysis, Progress and Future Perspectives in Dairy Cattle Selection: A Review. Animals 2021, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J.B.; Douglas, M.L.; O Williams, S.R.; Wales, W.J.; Marett, L.C.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Reich, C.M.; Hayes, B.J. Genomic Selection Improves Heat Tolerance in Dairy Cattle. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, J.; Nguyen, T.; Axford, M.; Nieuwhof, G.; Shaffer, M. Symposium review: Building a better cow—The Australian experience and future perspectives. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3702–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, G.; Sutherland, M.; Waas, J.; Schaefer, A.; Cox, N.; Stewart, M. Infrared Thermography—A Non-Invasive Method of Measuring Respiration Rate in Calves. Animals 2019, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaughan, J.B.; Mader, T.L.; Holt, S.M.; Lisle, A. A new heat load index for feedlot cattle1. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyabarathi, M.; Jeyakumar, S.; Manimaran, A.; Jayaprakash, G.; Pushpadass, H.A.; Sivaram, M.; Ramesha, K.P.; Das, D.N.; Kataktalware, M.A.; Prakash, M.A.; et al. Infrared thermography: A potential noninvasive tool to monitor udder health status in dairy cows. Veter- World 2016, 9, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, J.B.; Mader, T.L.; Holt, S.M.; Lisle, A. A new heat load index for feedlot cattle1. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DataGene, Technote 20 Heat Tolerance ABV. Dairy Australia, 2017.

- Nguyen, T.T.T. , et al., Breeding for heat tolerance in Australian dairy cattle: From development to implementation. Agriculture Victoria, AgriBio, Centre for AgriBioscience, Bundoora, Victoria 3083, Australia, 2017.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Bowman, P.J.; Haile-Mariam, M.; Pryce, J.E.; Hayes, B.J. Genomic selection for tolerance to heat stress in Australian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2849–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihulay, H.; Abied, A.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Adaptation Mechanisms of Small Ruminants to Environmental Heat Stress. Animals 2019, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ashraf, S.; Goud, T.S.; Grewal, A.; Singh, S.; Yadav, B.; Upadhyay, R. Expression profiling of major heat shock protein genes during different seasons in cattle (Bos indicus) and buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) under tropical climatic condition. J. Therm. Biol. 2015, 51, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Group 1 (Thermo-susceptible) |

Group 2 (Thermotolerant) |

|---|---|---|

| Respiration rate (breadths min_1)# | 91.8 + 34.7 (303)* | 90.1 + 32.1 (313) |

| Panting score# | 2.0 + 0.8 (307) | 1.9 + 0.8 (317) |

| Daily Milk Production (kg/d) | 21.3 + 5.6b (341) | 30.0 + 6.9a (340) |

| Fat % | 4.4 + 0.9a (340) | 3.9 + 32.1b (313) |

| Protein % | 3.2 + 0.3a (340) | 3.0 + 0.2b (340) |

| Concentrate intake (kg/d) | 5.3 + 1.8b (322) | 6.2 + 1.6a (320) |

| Rumination time (mins) | 399.4 + 108.b (320) | 445.9 + 108.5 a (320) |

| Residual feed (kg/d) | 1.1 + 0.2a (322) | 0.7 + 0.8b (322) |

| Thermo-susceptible Group (n = 19) |

Thermotolerant Group (n = 20) |

Herd Average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (sample size) | 19* | 20 | 39.0 |

| BPI | 75.7 ± 19.2 | 63.2 ± 16.5 | 69.3 |

| ASI | 32.0 ± 12.5 | 19.0 ± 11.9 | 25.3 |

| HWI | 65.6 ± 15.3 | 58.4 ± 13.3 | 61.9 |

| TWI | 37.8 ± 21.5 | 29.5 ± 14.3 | 33.5 |

| Milk | 86.7 ± 68.7 | -14.1 ± 91.2 | 35.0 |

| Milk Protein | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 3.3 |

| Milk Fat | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 0.25 ± 2.6 | 3.1 |

| HT | 102.4 ± 0.95 | 104.1 ± 0.93 | 103.2 |

| Feed Saved | 20.8 ± 12.0 | 31.5 ± 14.3 | 26.28 |

| Fertility | 106.0 ± 1.05 | 105.8 ± 1.38 | 105.9 |

| Age group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5 years | years | > 7 years | Total/Overall | |

| N | 15 | 11 | 13 | 39.0 |

| BPI | 106.1a ± 21.3 | 62.6ab ± 17.6 | 32.4b ± 20.1 | 69.26 |

| ASI | 53.9 a ± 15.6 | 18.5ab ± 12.8 | -1.9b ± 10.4 | 25.33 |

| HWI | 86.9 ± 16.8 | 59.1 ± 13.1 | 35.5 ± 18.1 | 61.9 |

| TWI | 83.4a ± 17.9 | 17.3ab ± 20.1 | -10.2b ± 19.5 | 33.54 |

| Milk | 207.1a ± 79.0 | -175.3b ± 131.1 | 14.4ab ± 68.7 | 35.0 |

| Milk Protein | 9.0 a ± 1.7 | -0.18b ± 2.0 | -0.23b ± 1.5 | 3.33 |

| Milk Fat | 7.0 ± 3.0 | 1.2 ± 2.8 | 0.2 ± 2.2 | 3.10 |

| HT | 100.9 ± 1.2 | 103.9 ± 1.0 | 105.4 ± 0.80 | 103.2 |

| Feed Saved | -0.3 ± 15.04 | 51.7 ± 19.7 | 35.2 ± 11.0 | 26.28 |

| Fertility | 104.7 ± 1.43 | 106.91 ± 0.80 | 106.4 ± 1.91 | 105.9 |

| BPI# | ASI | HWI | TWI | Milk | Protein | Fat | FS | Fertility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASI | 0.80** | ||||||||

| HWI | 0.97** | 0.64** | |||||||

| TWI | 0.95** | 0.77** | 0.92** | ||||||

| Milk | 0.11 | -0.05 | -0.13 | -0.02 | |||||

| Protein | 0.52** | 0.70** | 0.40** | 0.58** | 0.64** | ||||

| Fat | 0.61** | 0.80** | 0.46** | 0.56** | -0.02 | 0.46** | |||

| FS | -0.30 | -0.41** | -0.13 | -0.32* | -0.29 | -0.45** | 0.48** | ||

| Fertility | 0.51** | 0.02 | 0.62** | 0.30 | -0.28 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| HT | -0.43** | -0.70** | -0.28 | -0.45** | -0.33* | -0.74** | -0.59** | 0.45** | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).