1. Introduction

Left displaced abomasum (LDA) is a multifactorial disease of cattle that occurs mainly during the transition postpartum period [

1,

2]. In the left form of displacement, the abomasum occupies a caudodorsal position, located between the rumen and the left abdominal wall. The pathology is characterized by a decrease in milk production and an increased risk of culling. The most effective way to treat this pathology is surgery, which significantly increases the economic costs of milk production. The median incidence of left displaced abomasum among Holstein cattle based on 12 studies is 2.71% [

3], which makes this pathology one of the important threats to the economic stability of dairy livestock farming.

Numerous studies have established that left displacement of the abomasum is recorded often (75% of cases) than right displaced abomasum (RDA) [

4,

5]. Right displacement is more likely to be persistent, in contrast to left-sided form, which significantly increases the risk of right pathology. It has also been established that right form is more acute than left one and requires prompt surgical treatment. However, due to its frequent occurrence, the economic damage from LDA significantly exceeds the losses from RDA.

Despite the widespread occurrence of LDA, its etiology remains not fully understood. There are several hypotheses explaining LDA etiology. It is believed that one of the most important prerequisites for displacement of the abomasum is atony arising as a result of inadequate feeding that does not correspond to the physiological status and leading to the accumulation of gas and liquid in the organ cavity, since this symptom occurs in more than 80% of all cases [

4,

6,

7]. According to the hypothesis, gas appears in the abomasum body and, with an increase in its volume, shifts abomasum cranially. The flow of gas toward the pyloric region causes displacement of the abomasum to the cranial dorsal side and then its movement to the left side of the abdominal wall [

8]. Occurrence of left displaced abomasum was also associated with the elliptical shape of the abdominal cavity section [

9] and negative energy balance [

10]. It has also been demonstrated that an increase in BHB and AST levels in the first two weeks after birth is a predictor for the occurrence of the described pathology [

11,

12,

13], as well as low concentrations of liver-secreted IGF1 together with increased non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) and beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) [

13]. Cows with left displaced abomasum often have comorbidities such as ketosis, mastitis, metritis, endometritis and fatty liver [

4,

14].

Heritability for LDA has been estimated in Holstein cattle to be between 0.1 and 0.31 [

2,

15,

16]. Early attempts have already been made to determine the genetic determinants for the disease. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), associated with left displaced abomasum [

2,

17,

18]. However, clarifying the position of quantitative trait loci (QTL) in individual populations and identifying the genes underlying this complex disease can contribute to both a deeper understanding of the pathogenesis of LDA and the development of effective approaches to the treatment and prevention of this pathology.

Another effective tool for genomic analysis is the assessment of individual autozygosity of animals, or extended homozygous nucleotide fragments - runs of homozygosity (ROH), indicating the inbreeding. The consolidation of ROH loci with a low frequency of recombination in generations of animals may indicate the formation of gene clusters under selection pressure, mostly due to positive selection for productivity traits, as well as adaptation to changing environmental conditions. ROH allow us to more effectively assess the degree of genomic inbreeding both in a population and individually and also to evaluate the conservation of certain loci. A high degree of inbreeding in the studied animals can influence the results of genome-wide association study, increasing the likelihood of detecting false positive associations. Moreover, the location of candidate genes in ROH may indicate their significant influence on the breeding quality of animals. Modern industrial dairy farming technologies are based on the exclusive use of assisted reproductive technologies, such as artificial insemination of cows. For cryopreservation of genetic material (sperm), sires with the highest breeding value and high rates of heritability of productive qualities are selected. This approach leads to an increase in the inbreeding degree in herds and an increase in the population genetic homogeneity. As a result of the use of such a strategy for improving the genetic potential of dairy cattle, the frequency of predisposition hereditary factors for multifactorial diseases increases. Loci containing disease susceptibility factors often become homozygous, which increases the number of disease cases in herds.

The aim of the study is to find genetic associations characterizing the genomic variability of the predisposition to LDA in Holstein cattle of the Leningrad region of the Russian Federation.

2. Materials and Methods

The collection of biological material for the study was carried out in three farms in the Leningrad region. The study analyzed two groups of animals, divided according to the principle of “case” and “control” (healthy animals). Peripheral blood samples were taken from a mixed-age herd of 360 highly productive Holstein cows, from which 175 animals belonged to the control group and 185 cows belonged to the case group that consisted of animals with left displaced abomasum diagnosed by clinical examination. Sampling was carried out in specialized vacutainer blood collection tubes with EDTA as an anticoagulant then stored in frozen condition at -200C until the DNA extraction procedure. DNA was isolated from samples using the phenol-chloroform method according to a standard proteolytic treatment protocol using proteinase K. Quality control of isolated DNA was carried out using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, USA).

For the genotyping procedure the GeneSeek® Genomic Profiler™ Bovine 100K DNA chip (Neogen, USA) with a coverage density of 95256 SNPs was used. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to assess population stratification and determine the number of genetic covariates. Quality control and filtering of genotyping data were carried out using the PLINK 1.90 software package [

19]. When filtering the bioarray data, the following value thresholds were used: the minimum allele frequency was set at a threshold of <0.5, the p-value threshold for the Hardy-Weinberg distribution was <1e-6, the number of missing variants per sample was <0.05, and the proportion of missing variants per marker was also <0.05.

ROH analysis was implanted in detectRUNS package in R. Parameters for ROH search were determined according to the following criteria [

20]: a sliding window size was 25 SNP, the proportion of homozygous overlapping windows was 0.05, a minimum number of 35 homozygous SNPs included in a window, a maximum gap between consecutive SNPs of 0.1 Mb, a maximum number of 1 heterozygous SNP per window. Found ROH islands then were divided into three classes based on its size: short (0.5-1Mb), medium (1-4Mb) and large (>4Mb) [

20]. To evaluate the inbreeding coefficient, we count proportion of the genome covered by runs of homozygosity by dividing total length of ROH by the length of genome (FROH) [

21] according to the following formula:

where:

i is the number of the animali,

n stands for total number of ROH found in animali,

LROHi represents total ROH length for animali,

Lg identifies genome length of the individual.

We defined a common ROH island based on overlapping homozygous regions with a frequency greater than 0.50 for all animals and also considered the suggestive frequency threshold greater than 0.40 to include more candidate genes and regions. Сandidate genes located within ROH islands were identified using cattle genome assembly ARS-UCD1.3 (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_002263795.3/). To find genomic loci that may contain genes whose polymorphisms are strongly associated with the development of LDA, we also looked at the distribution of ROH islands in the case and control groups separately. The statistical significance of the difference in the incidence of ROH islands in healthy animals and cows with displacement was assessed using the Pearson chi-square test.

To ensure accuracy of genome-wide association study we used three statistical models independently: General Linear Model (GLM), Mixed Linear Model (MLM), and Fixed and Random Model Circulating Probability Unification (FarmCPU), implemented in the GAPIT Version 3 [

22] and rMVP [

23] packages in R.

False discovery rates (FDR) were calculated as described by Benjamini and Hochberg [

24]:

where:

m is the number of tests,

R is the number of significant tests,

Pr(> 0) is equal to the significance threshold.

The results were visualized using the qqman (v.0.1.9) [

25] and qqplot2 (v.3.4.4.) packages in the RStudio programming environment (v. 2023.9.1.494) using the Manhattan plot.

Annotation of the identified associations was carried out using cattle genome assembly ARS-UCD1.3, visualized in the genome browser GDV (Genome Data Viewer). To search for QTL associated with Economically relevant traits the CattleQTLdb database was used. For functional annotation of genes located within ±0.2 Mb of suggestive SNPs the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene database was used, as well as the open UniProt protein sequence database and scientific literature. The impact of a substitution on a protein sequence was determined using the VEP (Variant Effect Predictor) software [

26].

3. Results

In our study 85,605 polymorphic genetic variants obtained from genotyping by GeneSeek® Genomic Profiler™ Bovine 100K DNA array and 325 samples passed quality control. Of the filtered samples 172 were taken from animals of experimental group and 153 of the control group.

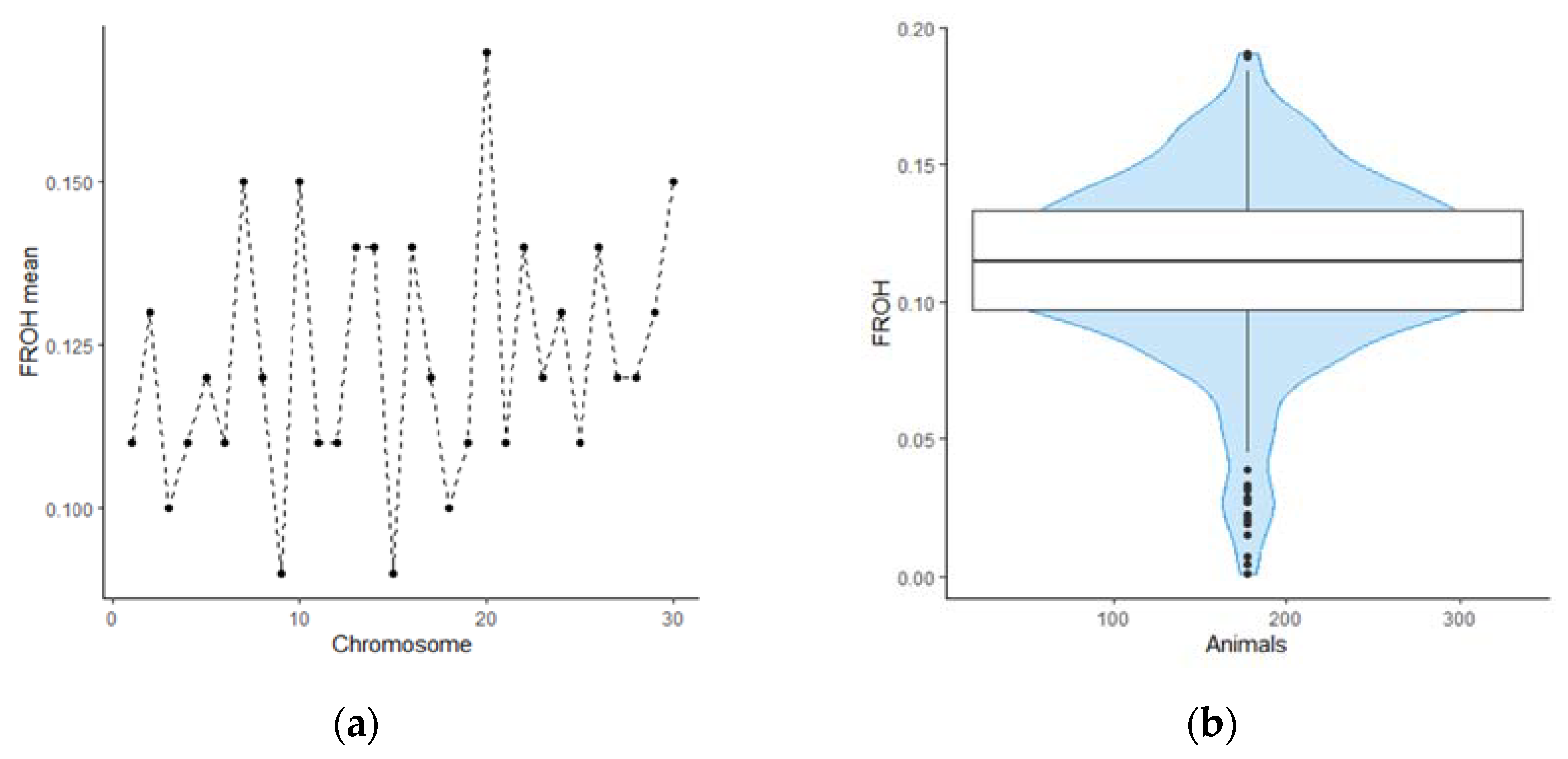

We evaluated inbreeding coefficient using F

ROH method. The F

ROH ranged from 0.01 to 0.19 for individual genotypes and from 0.09 to 0.17 for mean F

ROH value for each bovine chromosome. We found that the distribution of homozygosity has similar value across autosomes. However, BTA 9 and BTA 15 are distinguished by a noticeably lower content of runs of homozygosity, compared to other chromosomes. On the contrary, BTA 20 in animals from our sample on average contains more homozygous regions, which requires further consideration. The distribution patterns of genomic inbreeding coefficients among the studied animals and bovine chromosomes are shown on

Figure 1.

Analysis of ROH islands occurrence frequency in the studied population of dairy cattle allowed us to identify a number of conserved regions in the genome, which, as we assume, are under selection pressure. As a next step, we calculated the frequency of ROH and identified ROH islands for each chromosome in our population. First, we identified regions with an occurrence frequency greater than 0.5. Two such ROH island was discovered on BTA14 and two were located on BTX (

Table 1).

Also, 20 homozygous regions were found, including at least 5 SNPs, which were found in more than 40% and less than 50% of the all studied population. Suggestive ROH were mapped to BTA5, BTA7, BTA13, BTA14, as well as BTA20, BTA21, BTA22, BTA26 and BTX. Suggestive homozygous regions on BTX had the longest extend (6.4 Mb, 5.5 Mb and 3.9 Mb) and were present in the greatest number (n = 3) which can be explained by the characteristics of sex chromosomes recombination.

The distribution of ROH islands in the control and case groups of animals was slightly different. In particular, four ROH, two of which were located on BTA13, one on BTA21 and one on BTX were more frequently represented in the genomes of animals in the control group. It is worth noting that no selection signatures were found that were significantly more common in the control group than in the experimental group. Information about extent of the loci and their frequency in the both groups is shown in

Table 2.

According to the CattleQTLdb first loci on BTA13 contains QTL associated with body conformation traits such as stature, dairy form, rear leg placement, body depth, rump width, foot angle and few traits related to productivity and susceptibility, namely milk yield and milk fat yield and M. paratuberculosis susceptibility. The second ROH on the given chromosome, which has the largest frequency range among the two groups, is also contains QTL for a similar set of traits, specifically body depth, rump width, stature, dairy form, udder cleft and several others. Moreover, the occurrence of this region in the genomes of animals of the two groups was significantly different, which indicates the role of body shape in the development of the disease.

The region of homozygosity on BTA21 does not contain the described QTL but in humans, loss of homologous genomic region is connected with the Prader-Willi syndrome. ROH island on BTX is associated with semen quality more specifically percentage normal sperm and general reproductive traits such as age at puberty and scrotal circumference.

Regarding the GWAS analysis, the choice of three models was based on their unique advantages in addressing various complexities of genetic analysis. GLM is an effective tool for analyzing simple population structures, whereas MLM provides a more robust framework for dealing with complex population structures, potentially reducing false positive associations [

27]. FarmCPU takes a novel approach implementing both fixed and random effects, allowing to simultaneously handle effects of cryptic relatedness and population stratification thus make it possible to more accurate map quantitative trait loci [

28]. Our comparative analysis revealed subtle differences in the results of all three models. Thus, we focused on the MLM and FarmCPU models as this could minimize the chance of finding false associations while increasing the likelihood of detecting true associations, resulting in a more robust and complete set of marker trait associations.

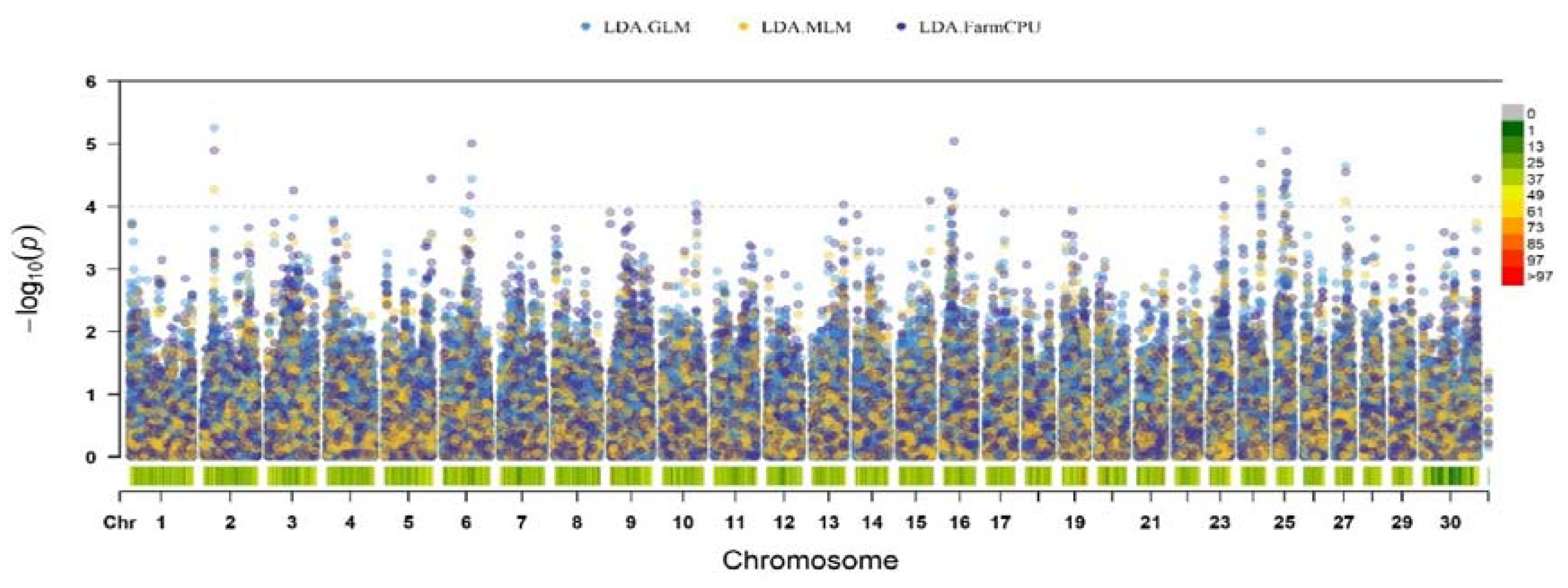

Figure 2 shows the results of a genome-wide association study with left displaced abomasum in the studied group of Holstein cows. Fourteen suggestive SNPs (p < 1 × 10-4) were detected. The found polymorphisms were identified on BTA2, BTA3, BTA6, BTA9, as well as BTA16, BTA23, BTA24, BTA25, BTA27 and BTX.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of significant SNPs for left displaced abomasum in Russian Holstein cattle identified in FarmCPU, GLM, and MLM of GWAS analysis. The lower horizontal line represents the suggestive significance threshold (p < 1 × 10−4). The upper line represents genome-wide significance threshold (p < 1 × 10−4). Colored dots indicate an associated SNP.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of significant SNPs for left displaced abomasum in Russian Holstein cattle identified in FarmCPU, GLM, and MLM of GWAS analysis. The lower horizontal line represents the suggestive significance threshold (p < 1 × 10−4). The upper line represents genome-wide significance threshold (p < 1 × 10−4). Colored dots indicate an associated SNP.

The largest number of suggestive SNPs was located on BTA25 (n = 4); all polymorphisms were located within locus positioned in range from 17.7 to 27.1 Mb. Two nucleotide polymorphisms were located on BTA16, the remaining chromosomes each contained one nucleotide substitution associated with the development of pathology.

The structural annotation revealed 14 genes that contained detected SNPs or were close to them. Functional annotation of polymorphisms showed the presence of substitutions mainly in the non-coding parts of the genome (such as intergenic regions, introns). Of the 14 polymorphisms detected, of which 6 were in introns of following genes: ABCB11, SRP72, RGS18, GSG1L, FBXL19 and PRKCB. Remaining polymorphisms were found in intergenic regions. Substitutions located in exons have not passed the threshold of statistical significance, were synonymous and did not affect the functions of proteins encoded by the genes in which they were located. More detailed information about the associated polymorphisms is in

Table 3.

Two SNPs were located in QTLs previously described for the trait. Thus, the SNP located on BTA23 was within the boundaries of the locus with coordinates 29.2-47.0 Mb [

29]. Also, in previous studies on the Chinese population of Holstein cattle, one of the regions on chromosome 25 (24.8–26.8 Mb) was already noted [Huang H].

GO enrichment analysis showed that candidate genes were involved in a wide range of biological processes, including protein ubiquitination (ABCB11, FBXL19), fatty acid metabolism (ABCB11, PNPLA4), the formation of organs and tissues as homeotic genes (SOX4), transcription regulation, regulation of signal transduction and others. A list of GO (Gene Ontology) terms characterizing biological processes is displayed in the table below.

However, the biological role of certain genes has not been established due to their low representation in the scientific articles.

4. Discussion

Genome-wide association study for left displaced abomasum made it possible to identify associated polymorphisms localized close to or within genes, of which such genes asABCB11, SRP72, RGS18, SOX4, GSG1L, FBXL19, PNPLA4 are most promising. Our results suggest that susceptibility to LDA may be formed by the contribution of multiple genes with small effect sizes, consistent with moderate estimates of heritability for the trait.

Past study of Ricken et al. have found genetic correlations between LDA and milk fat, milk protein and milk yield [

30]. Our results partly confirm previous findings, as some of the genes described in our study located in QTL for traits such as milk fat content (ABCB11) [

31] and glycerophosphocholine content (GSGL1) [

32].

Runs of homozygosity analysis shown that the studied population is characterized by a moderate degree of genomic inbreeding. For most animals this value ranged from 0.1 to 0.15. Four ROH islands were discovered that were present in the genomes of most animals of both groups, all of them located on two chromosomes - BTA14 and BTX. Most likely, the reason for the appearance of such regions in the genome is selection pressure aimed at improving the quality of livestock productivity. It should be noted that some of the discovered regions, as well as the candidate genes located in them, have already been described for other herds in the scientific articles. As for one of homozygous region located on BTA14, genes located in the locus have already been associated with such phenotypic traits as serum prolactin level [

33], growth and feed efficiency [

34], carcass weight (CWT) and eye muscle area (EMA) in Korean Hanwoo cattle [

35], carcass trait [

36], fat deposition in Brazilian Nellore cattle but productive traits, especially important for dairy cattle, have not yet been associated with this locus.

Some loci were more widely represented in the group of animals with LDA than in healthy individuals. Thus, two loci on BTA13, both containing QTL for body conformation traits had the greatest difference in prevalence (10.11% and 15.28%, respectively) between two groups. Moreover, the second ROH was statistically significantly different in its occurrence in the case and control groups and was more widely represented in animals with LDА. That may be due to them containing selection signatures referring to the body conformation of Holstein cows. As previously mentioned, the occurrence of LDA was associated with elliptical shape of the abdominal cavity section [

9] which is typical for this breed of cattle. The shape of the abdominal cavity may affect the location of the internal organs, causing the abomasum to be pushed out of the right side of the body when it is inflated. Although body measurements were not taken in this study, we can hypothesize that the shape and volume of the abdominal cavity, according to genomic data, may be a predisposing factor for left displaced abomasum in Holstein cattle.

Another ROH more common in animals with LDA was located on BTA21. In our sample, healthy cows were 7.59% less likely to become its carriers. The locus contains five copies of genes coding small nucleolar RNASNORD116 and one copy of SNORD109A. In humans, this genes strongly associated with Prader-Willi Syndrome and Angelman Syndrome, complex multisystem genetic disorders with developmental delay, behavioral uniqueness and speech impairment [

37,

38]. Prader-Willi Syndrome is also characterized by life-threatening obesity due to uncontrolled appetite and muscle weakness [

38]. Despite the fact that QTL has not yet been identified for productive traits in this genetic region, it may play a significant role in the formation of the nervous system and appetite control both in humans and cattle according to the principle of orthology which may be connected with occurrence of the studied disease.

ABCB11 encodes the bile acid export pump (BSEP), the main transporter of bile acids from hepatocytes to the biliary system [

39]. The connection between liver diseases and impaired motility of the digestive system in cattle has been demonstrated in a number of publications [

2,

4,

40,

41]. Thus, in cows with pathologies of this organ, a decrease in the strength and duration of rumen contraction was noted [

41]. Studies have reported that cases of LDA in animals with liver lesions are more common than in the general population [

2]. When analyzing the biochemical profile of animals, it was found that in cases of LDA, markers of hepatocyte death significantly increase [

4]. And, vice versa, an increase in some of hepatocyte death markers predicts the onset of displacement [

11,

12], however, to explain this connection requires further research. A previous GWAS study has already suggested a link between bile acid metabolism and LDA [

2].

The SRP72 gene encodes a polypeptide that is part of a protein complex that promotes post-translational modification of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum [

43]. In the signal recognition particle (SRP) SRP68 and SRP72 proteins form a heterodimer that has been difficult to investigate and thus many processes in which the previously mentioned protein is involved still remain not fully understood. It is known that polymorphisms in SRP72 are associated with one of the hereditary forms of aplastic anemia [

44]. Transcriptomic studies have demonstrated that the expression of SRP72 gene may be a marker of hepatotoxicity [

45]. The mechanism of involvement of this protein in the development of left displacement of the abomasum is also not completely clear. SRP72 may carry out post-translational modifications of proteins, whose direct or indirect interaction with certain substrates will lead to a decrease in the force of smooth muscles contraction which may affect on peristatic of the gastrointestinal tract and cause the occurrence of LDA. Or the effect may be more indirect, for example, it can be caused by changes in the passage of certain biochemical pathways.

SOX4 encodes a transcription factor involved in the formation of several organ systems during embryogenesis [

46]. The possible role of this gene in a hereditary predisposition to abomasum displacement is ambiguous since SOX4 is involved both in the formation of the nervous system and has a pleiotropic effect on the formation of the bile ducts of the liver [

47].

The GSG1L protein is a subunit of the AMPA receptor that regulates the transmission of nerve impulses at synapses [

48]. FBXL19 is involved in the ubiquitinylation of proteins and also regulates the activity of a number of homeotic genes by attaching CDK8 to their promoters [

49], thereby participating in the formation of the musculoskeletal system and internal organs disturbances in this process may be a predisposition factor for LDA. The protein is also involved in IL-33 signaling pathway [

50]. The role of these proteins in the development of left displaced abomasum requires further study.

Thus, we mapped loci that may be associated with LDA in Holstein cattle of the Leningrad region. Found loci were identified on BTA2, BTA3, BTA6, BTA9, as well as BTA16, BTA23, BTA24, BTA25, BTA27 and BTX. Most of the polymorphisms were not detected in previous studies, which may indicate the diversity of the genetic architecture in populations distributed in different geographical areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kirill Plemyashov and Anna Krutikova; Data curation, Anna Krutikova and Angelina Belikova; Formal analysis, Angelina Belikova; Funding acquisition, Kirill Plemyashov; Investigation, Tatiana Kuznetsova and Boris Semenov; Methodology, Anna Krutikova and Angelina Belikova; Project administration, Boris Semenov; Resources, Tatiana Kuznetsova and Boris Semenov; Software, Angelina Belikova; Visualization, Angelina Belikova; Writing – original draft, Anna Krutikova and Angelina Belikova; Writing – review & editing, Anna Krutikova and Angelina Belikova.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number №22-16-00143, https://rscf.ru/project/22-16-00143/.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by Local Ethical Committee of St. Petersburg State University of Veterinary Medicine, protocol №3 from 25.06.24.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Polina Anipchenko of Università degli Studi di Perugia for active assistance in the implementation of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Plemyashov, K.V.; Semenov, B. S.; Kuznetsova, T. Sh.; E.A. Korochkina; Nikitin, V. V.; G.S. Khusainova; A.A. Krutikova. Displacement of Abomasum in Highly Productive Dairy Cows. Veterinaria 2022, 25 (11), 48–54.

- Huang, H.; Cao, J.; Guo, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies QTLs for Displacement of Abomasum in Chinese Holstein Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97(3), 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, J. E.; Parker Gaddis, K. L.; Koeck, A.; Bastin, C.; Abdelsayed, M.; Gengler, N.; Miglior, F.; Heringstad, B.; Egger-Danner, C.; Stock, K. F.; Bradley, A. J.; Cole, J. B. Invited Review: Opportunities for Genetic Improvement of Metabolic Diseases. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99(9), 6855–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, U.; Nuss, K.; Reif, S.; Hilbe, M.; Gerspach, C. Left and Right Displaced Abomasum and Abomasal Volvulus: Comparison of Clinical, Laboratory and Ultrasonographic Findings in 1982 Dairy Cows. Acta. Vet. Scand. 2022, 64(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, V.; Hamann, H.; Scholz, H.; O Distl. Einflüsse Auf Das Auftreten von Labmagenverlagerungenbei Deutschen Holstein Kühen [Influences on the Occurrence of Abomasal Displacements in German Holstein Cows]. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2001, 108(10), 403–408.

- Doll, K.; Sickinger, M.; Seeger, T. New Aspects in the Pathogenesis of Abomasal Displacement. Vet. J. 2009, 181(2), 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittek, T.; Tischer, K.; Gieseler, T.; Fürll, M.; Constable, P. D. Effect of Preoperative Administration of Erythromycin or FLunixin Meglumine on Postoperative Abomasal Emptying Rate in Dairy Cows Undergoing Surgical Correction of Left Displacement of the Abomasum. J Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 232(3), 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, M.; Aoki, T.; Sakurai, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Inokuma, H.; Kawamoto, S.; Yamada, K. Fluoroscopic Observation of the Development of Displaced Abomasum in Dairy Cows. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017, 79(12), 1952–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöber M; Saratsis P. Vergleichende Messungen Am Rumpf von Schwarzbunten Kühen Mit Und Ohne Linksseitiger Labmagenverlagerung [Comparative Measurements on the Trunk in of Black and White Cows with and without Leftside Abomasal Displacement]. Dtsch Tierarztl Wschr. 1974, 81 (23), 564–565.

- Constable, P. D.; Hinchcliff, K. W.; Done, S. H.; Grünberg, W.; Radostits, O. M. Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Pigs and Goats, 11th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, Mo, 2017; pp. 436–621. [Google Scholar]

- Ospina, P. A.; Nydam, D. V.; Stokol, T.; Overton, T. R. Association between the Proportion of Sampled Transition Cows with Increased Nonesterified Fatty Acids and β-Hydroxybutyrate and Disease Incidence, Pregnancy Rate, and Milk Production at the Herd Level. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93(8), 3595–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen I; M, O.; Coskun A. The Level of Serum Ionised Calcium, Aspartate Aminotransferase, Insulin, Glucose, Betahydroxybutyrate Concentrations and Blood Gas Parameters in Cows with Left Displacement of Abomasum. Polish J. Vet. Sci. 2006, 9 (4), 227–232.

- Lyons, N. A.; Cooke, J. S.; Wilson, S.; Winden, van; Gordon, P. J.; Wathes, D. C. Relationships between Metabolite and IGF1 Concentrations with Fertility and Production Outcomes Following Left Abomasal Displacement. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174 (26), 657–657.

- Tschoner, T.; Zablotski, Y.; Feist, M. Retrospective Evaluation of Method of Treatment, Laboratory Findings, and Concurrent Diseases in Dairy Cattle Diagnosed with Left Displacement of the Abomasum during Time of Hospitalization. Animals 2022, 12(13), 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwald, N. R.; Weigel, K. A.; Chang, Y. M.; Welper, R. D.; Clay, J. S. Genetic Selection for Health Traits Using Producer-Recorded Data. I. Incidence Rates, Heritability Estimates, and Sire Breeding Values. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87 (12), 4287–4294.

- Tsiamadis, V.; Banos, G.; Panousis, N.; Kritsepi-Konstantinou, M.; Arsenos, G.; Valergakis, G. E. Genetic Parameters of Sub-clinical Macromineral Disorders and Major Clinical Diseases in Postparturient Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99(11), 8901–8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, S.; Zerbin, I.; Doll, K.; Rehage, J.; Distl, O. A Genome-Wide Association Study for Left-Sided Displacement of the Abomasum Using a High-Density Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Array. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101(2), 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mömke, S.; Sickinger, M.; Lichtner, P.; Doll, K.; Rehage, J.; Distl, O. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies Loci for Left-Sided Displacement of the Abomasum in German Holstein Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96(6), 3959–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slifer, S. H. PLINK: Key Functions for Data Analysis. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2018, 97(1), e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, G.; Yang, L.; Zhu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; Gao, H.; Liu, G. E.; Li, J. Genomic Patterns of Homozygosity in Chinese Local Cattle. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9(1), 16977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuillan, R.; Leutenegger, A.-L.; Abdel-Rahman, R.; Franklin, C. S.; Pericic, M.; Barac-Lauc, L.; Smolej-Narancic, N.; Janicijevic, B.; Polasek, O.; Tenesa, A.; MacLeod, A. K.; Farrington, S. M.; Rudan, P.; Hayward, C.; Vitart, V.; Rudan, I.; Wild, S. H.; Dunlop, M. G.; Wright, A. F.; Campbell, H. Runs of Homozygosity in European Populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83(3), 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. GAPIT Version 3: Boosting Power and Accuracy for Genomic Association and Prediction. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2021, 19(4), 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Liu, X. RMVP: A Memory-Efficient, Visualization-Enhanced, and Parallel-Accelerated Tool for Genome-Wide Association Study. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2021, 19(4), 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Method. 1995, 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. D. Qqman: An R Package for Visualizing GWAS Results Using Q-Q and Manhattan Plots. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3(25), 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, W.; Gil, L.; Hunt, S. E.; Riat, H. S.; Ritchie, G. R. S.; Thormann, A.; Flicek, P.; Cunningham, F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016, 17(1), 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. M.; Zaitlen, N. A.; Wade, C. M.; Kirby, A.; Heckerman, D.; Daly, M. J.; Eskin, E. Efficient Control of Population Structure in Model Organism Association Mapping. Genetics 2008, 178(3), 1709–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Huang, M.; Fan, B.; Buckler, E. S.; Zhang, Z. Iterative Usage of Fixed and Random Effect Models for Powerful and Efficient Genome-Wide Association Studies. PLOS Genet. 2016, 12(2), e1005767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mömke, S.; Scholz, H.; Doll, K.; Rehage, J.; Distl, O. Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Left-Sided Displacement of the Abomasum in German Holstein Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91(11), 4383–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricken M; Hamann H; Scholz H; Distl O. Genetic Analysis of the Prevalence of Abomasal Displacement and Its Relationship to Milk Output Characteristics in German Holstein Cows. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2004, 111(9), 366–370.

- Meredith, B. K.; Kearney, F. J.; Finlay, E. K.; Bradley, D. G.; Fahey, A. G.; Berry, D. P.; Lynn, D. J. Genome-Wide Associations for Milk Production and Somatic Cell Score in Holstein-Friesian Cattle in Ireland. BMC Genet. 2012, 13(1), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetens, J.; Heuer, C.; Heyer, I.; Klein, M. S.; Gronwald, W.; Junge, W.; Oefner, P. J.; Thaller, G.; Krattenmacher, N. Polymorphisms within the APOBR Gene Are Highly Associated with Milk Levels of Prognostic Ketosis Biomarkers in Dairy Cows. Physiol. Genomics. 2015, 47(4), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, B. C.; Houser, A.; Bagley, C. P.; Ely, K.; Payton, R. R.; Saxton, A. M.; Schrick, F. N.; Waller, J. C.; Kojima, C. J. A Polymorphism InXKR4is Significantly Associated with Serum Prolactin Concentrations in Beef Cows Grazing Tall Fescue. Anim. Genet. 2014, 45(3), 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoreishifar, S. M.; Eriksson, S.; Johansson, A. M.; Khansefid, M.; Moghaddaszadeh-Ahrabi, S.; Parna, N.; Davoudi, P.; Javanmard, A. Signatures of Selection Reveal Candidate Genes Involved in Economic Traits and Cold Acclimation in Five Swedish Cattle Breeds. Genet. Sel. 2020, 52(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, M. S. A.; Lim, D.; Park, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Gondro, C.; Park, B.; Lee, S. Functional Partitioning of Genomic Variance and Genome-Wide Association Study for Carcass Traits in Korean Hanwoo Cattle Using Imputed Sequence Level SNP Data. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Srikanth, K.; Won, S.; Son, J.-H.; Park, J.-E.; Park, W.; Chai, H.-H.; Lim, D. Haplotype-Based Genome-Wide Association Study and Identification of Candidate Genes Associated with Carcass Traits in Hanwoo Cattle. Genes 2020, 11(5), 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shu, X.; Mao, S.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Zou, C. Genotype–Phenotype Correlations in Angelman Syndrome. Genes 2021, 12(7), 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M. G.; Miller, J. L.; Forster, J. L. Prader-Willi Syndrome - Clinical Genetics, Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches: An Update. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2019, 15(4), 207–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayagam, J. S.; Williamson, C.; Joshi, D.; Thompson, R. J. Review Article: Liver Disease in Adults with Variants in the Cholestasis-Related Genes ABCB11, ABCB4 and ATP8B1. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52(11–12), 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezborodov, P.N. Study Of The Rumen Motor Function In High-Productive Cows With Abomasum Displacements. Izvestiya of Timiryazev Agricultural Academy (TAA) 2019, 5, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyuzhny, I.I.; Barinov, N. D. Liver Disorders in Cows of Holstein-Friesian Breed. The Veterinarny Vrach 2015, 2, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. S.; Tao, J. Z.; Xu, L. H.; Wei, F. H.; He, S. H. Identification of Disordered Metabolic Networks in Postpartum Dairy Cows with Left Displacement of the Abomasum through Integrated Metabolomics and Pathway Analyses. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82(2), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, K.; Juaire, K. D.; Soni, K.; Shanmuganathan, V.; Hendricks, A.; Segnitz, B.; Beckmann, R.; Sinning, I. Reconstitution of the Human SRP System and Quantitative and Systematic Analysis of Its Ribosome Interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47(6), 3184–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Altri, T.; Schuster, M. B.; Wenzel, A.; Porse, B. T. Heterozygous Loss of Srp72 in Mice Is Not Associated with Major Hematological Phenotypes. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 103(4), 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatakuti, S.; Pennings, J. L. A.; Gore, E.; Olinga, P.; Groothuis, G. M. M. Classification of Cholestatic and Necrotic Hepatotoxicants Using Transcriptomics on Human Precision-Cut Liver Slices. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29(3), 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M. H.; Harvey, R. P.; Wegner, M.; Sock, E. Cardiac Outflow Tract Development Relies on the Complex Function of Sox4 and Sox11 in Multiple Cell Types. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 71(15), 2931–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncy, A.; Antoniou, A.; Cordi, S.; Pierreux, C. E.; Jacquemin, P.; Lemaigre, F. P. Transcription Factors SOX4 and SOX9 Cooperatively Control Development of Bile Ducts. Dev. Biol. 2015, 404(2), 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perozzo, A. M.; Schwenk, J.; Kamalova, A.; Nakagawa, T.; Fakler, B.; Bowie, D. GSG1L-Containing AMPA Receptor Complexes Are Defined by Their Spatiotemporal Expression, Native Interactome and Allosteric Sites. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14(1), 6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova, E.; Kondo, T.; Feldmann, A.; Nakayama, M.; Koseki, Y.; Konietzny, R.; Kessler, B. M.; Haruhiko Koseki; Klose, R. J. FBXL19 Recruits CDK-Mediator to CpG Islands of Developmental Genes Priming Them for Activation during Lineage Commitment. eLife 2018, 7.

- Pinto, S. M.; Subbannayya, Y.; Rex, D. A. B.; Raju, R.; Chatterjee, O.; Advani, J.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Keshava Prasad, T. S.; Wani, M. R.; Pandey, A. A Network Map of IL-33 Signaling Pathway. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 12(3), 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).