1. Introduction

Potato is an important and widely recognized food product worldwide. It is particularly recommended by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization as a plant that supports food security, especially in the face of continuous population growth and associated challenges in food access [

1,

2]. Potatoes are low in calories but rich in starch, protein, vitamins (C and B-group), as well as minerals such as potassium, magnesium, zinc, and manganese. They are the most commonly consumed vegetable in Europe and North America, simultaneously serving as the primary source of antioxidants in the human diet. Therefore, technologies and cultivation methods aimed at improving the nutritional quality of potatoes can significantly impact public health [

3].

To achieve success in potato cultivation and maintain food security, herbicides are often used to control weeds [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, there are alternative weed control methods, such as organic farming, biodynamic cultivation, mulching, and biological weed control [

9]. Diversifying approaches to weed control can contribute to more sustainable potato cultivation, which is crucial for maintaining the supply of this essential carbohydrate source and dietary component for people worldwide [

8,

10].

Phytotoxicity refers to the ability of chemical substances or environmental factors to induce negative effects on plants. It includes substances like pesticides, herbicides, heavy metals, mineral salts, as well as environmental factors such as air pollution, UV radiation, and climate change [

10,

11]. In agriculture, phytotoxicity is significant due to the extensive use of chemical substances for pest, disease, and weed control. However, improper use or excessive application of these substances can lead to plant damage, reduced yields, and a loss of production value. Adverse weather conditions, such as heavy rainfall or drought, can also increase phytotoxicity, especially in certain soil types and susceptible potato cultivars [

11]. Phytotoxicity is an important aspect that must be considered in agriculture to ensure effective plant protection and maintain crop productivity while minimizing the environmental impact [

11,

12].

Phytotoxic effects on plants can manifest as leaf necrosis, growth inhibition, deformations, and changes in plant tissue structure. These effects can have a negative impact on plant development and crop quality.

Sources of phytotoxicity include pesticides, herbicides, environmental pollutants, industrial substances, and natural factors that can affect plants. Research on phytotoxicity is essential for evaluating the impact of various substances and factors on plants. These studies can help develop guidelines and regulations regarding the use of chemical substances in agriculture. Phytotoxicity can also have a detrimental impact on the natural environment, including aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Therefore, it is crucial to address the risks associated with the release of phytotoxic substances into the environment and the necessity of controlling them to protect nature.

The threat of weed infestations in potato plantations, particularly from herbicides, is significant and continues to grow. Potatoes have a low competitive ability against weeds, stemming from their slow initial growth. Factors contributing to weed infestation in potato cultivation include the increasing share of cereals in crop structure, simplifying crop rotations, organic fertilization, as well as no-till and poorly conducted maintenance practices. The introduction of simplifications in crop cultivation typically results in increased weed infestation. However, currently, replacing mechanical treatments with appropriate herbicides and their mixtures greatly simplifies maintenance. Properly selected herbicides provide nearly complete destruction of most weed species in potato plantations and are fully selective for the protected crop [

4,

13,

14,

15].

When selecting herbicides for potato cultivation, consideration should be given not only to the spectrum of targeted weeds but also to the phytotoxic effects of the substances on the cultivated plant [

5,

11,

16,

17,

18]. Phytotoxic reactions most commonly occur when herbicides are applied after potato emergence. This reaction is particularly significant in seed production as it can hinder or even prevent proper negative selection through difficulties in identifying virus diseases. In commercial production, it can lead to reduced yields, the production of smaller tubers, increased damage, and a decline in quality. This is most noticeable in cultivars with the shortest vegetation periods, as they have limited time for chlorophyll regeneration [

10,

19,

20,

21].

Phytotoxicity of herbicides is largely determined by the genetic tolerance of cultivars and soil-climate factors [

11,

12,

22,

23]. The phytotoxic effect of herbicides also increases under conditions of low rainfall, poor preparation of the herbicide, and in cold, high precipitation years [

24,

25,

26].

Phytotoxic symptoms on potato plants are usually transient and persist, depending on the sensitivity of a particular cultivar, for 14 to 28 days following treatment [

7,

8,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Reducing the duration of phytotoxic symptoms on potato plants is important, particularly for cultivars with short vegetation periods. Prolonged symptom persistence can impede the regeneration of the photosynthetic surface, affecting yield accumulation and quality [

31,

32].

The conducted erlier research has not yielded a definitive answer regarding the response of plants to herbicides used in potato cultivation and their selectivity towards the cultivated plant. Therefore, the aim of the conducted research was to assess the phytotoxic effects of herbicides on cultivated potato cultivars and weeds. The alternative hypothesis has been confirmed in the study, demonstrating that the application of herbicides and their mixtures, such as: (a) metribuzin – PRE; (b) metribuzin + rimsulfuron + ethoxylated isodecyl alcohol – PRE; (c) metribuzin – POST; (d) metribuzin + rimsulfuron + ethoxylated isodecyl alcohol – PRE; (e) metribuzin + fluazifop-P butyl – POST; (f) metribuzin + sulfosulfuron + SN oil – POST emergence:

Provides a broader range of herbicidal action and inflicts more substantial damage to weeds, while simultaneously preventing phytotoxic damage to the crop plants when compared to mechanical weed control and complete weed elimination.

Allows for the reduction of environmental pollution and ensures improved chemical treatment efficacy by employing smaller herbicide doses, contrary to the null hypothesis that posits no differences between herbicide and herbicide mixture variants and the variant without weed protection and the variant with mechanical control.

2. Materials and Methods

The research results were based on a field experiment conducted in 2007-2009 at the Institute of Plant Breeding and Acclimatization - National Research Institute in Jadwisin (52°28′ N, 21°02′ E).

2.1. Field research

The experiment was designed using the method of randomized sub-blocks in a dependent layout, a split-plot design, with three replications. The study investigated two factors: the first-order factor comprised potato cultivars – moderately early ‘Irga’ and moderately late ‘Fianna’, while the second-order factors were weed control methods: 1) control object - without protection; b) mechanical weed control, extensive mechanical treatments (every 2 weeks) from planting until row closure; 3) Sencor 70 WG - 1 kg∙ha

-1 - before potato emergence; 4) Sencor 70 WG – 1 kg∙ha

-1 + Titus 25 WG - 40 g∙ha

-1 + Trend 90 EC – 0.1% before potato emergence (PRE); 5) Sencor 70 WG - 0.5 kg∙ha

-1 after potato emergence (PRE); 6) Sencor 70 WG – 0.3 kg∙ha

-1 + Titus 25 WG – 30 g∙ha

-1 + Trend 90 EC – 0.1% after potato emergence (POST); 7) Sencor 70 WG - 0.3 kg∙ha

-1 + Fusilade Forte 150 EC - 2 dm∙ha

-1 after potato emergence (POST); 8) Sencor 70 WG - 0.3 kg∙ha

-1 + Apyros 75 WG - 26.5 g∙ha

-1 + Atpolan 80 SC - 1 dm∙ha

-1 after potato emergence (POST). Herbicides were applied using 300 dm∙ha

-1 of water. Winter rye was the preceding crop, and after its harvest, white mustard was sown as a cover crop to be ploughed under. After winter rye harvest, nitrogen fertilization at a rate of 50 kg N·ha

-1 was applied, followed by subsoiling and sowing of white mustard (20 kg·ha

-1). In the autumn of the year preceding potato planting, phosphorus-potassium fertilization was applied (39.3 kg P·ha-1 and 116.2 kg K·ha

-1), followed by autumn ploughing. Nitrogen fertilizers were applied in the spring (100 kg N·ha

-1), mixed with the soil using a cultivation tool with a coil harrow. Potato tubers were planted in the third decade of April with a spacing of 75 x 33 cm. The seed material was classified as C/A, according to EU standards. An accumulator sprayer equipped with flat fan nozzles with a flow rate of 0.35–0.65 dm·min-1 and a pressure of 0.1–0.2 MPa was used for the spraying. Potato protection against diseases and pests was carried out according to IOR recommendations. Preparations such as Carial Star 500 SC 0.6 dm·ha

-1, Altima 500 SC – 0.4 dm·ha

-1, Cabrio Duo 112 EC 2.5 dm ·ha

-1, Ridomil Gold MZ Pepite 67.8 WG – 2.5 kg·ha

-1 were used for protection against late blight and early blight. Insecticides were applied to reduce Colorado potato beetle infestation, including Nuprid 200 SC – 0.15 dm·ha

-1, Cyperkil Max 500 EC – 0.06 dm·ha

-1, Calypso 480 SC – 0.75 dm·ha

-1, and Mospilan 20 SP at 0.05 kg·ha

-1. All pesticides were applied following IOR-PIB recommendations [

33,

34].

2.2. Characteristics of cultivars

The tested potato cultivars are presented in

Table 1.

2.3. Herbicide and adjuvants active substances

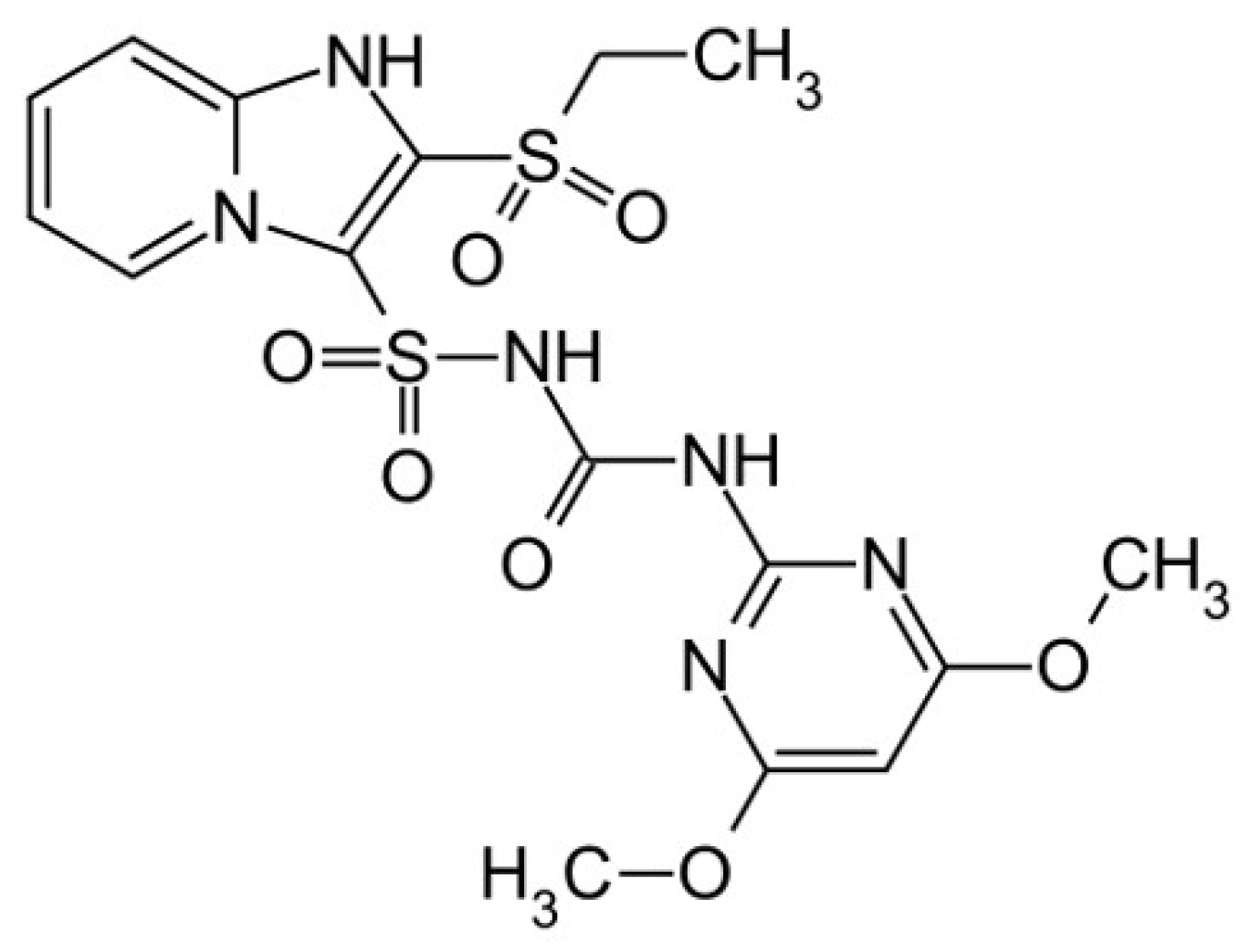

2.3.1. Sulfosulfuron

Chemical names: sulfosulfuron, 1-(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)-3-(2-ethylsulfonylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl)sulfonylurea, 1-(2-ethylsulfonylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-3-(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)urea, sulfonourea group (

Figure 1).

IUPAC Name: 1-(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)-3-(2-ethylsulfonylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl)sulfonylurea (Computed by LexiChem TK 2.7.0) [

36].

Molecular formula: C16 H18 N6 O7 S2; Registry Number: 141776-32-1 [

37]. Molecular Weight – 470.5 g/mol [Computed by PubChem 2.1 [

36].

GHS Classification: H400 - Very toxic to aquatic life [Acute Hazard]; H410 - Very toxic to aquatic life with long-lasting effects [Long-term Hazard].

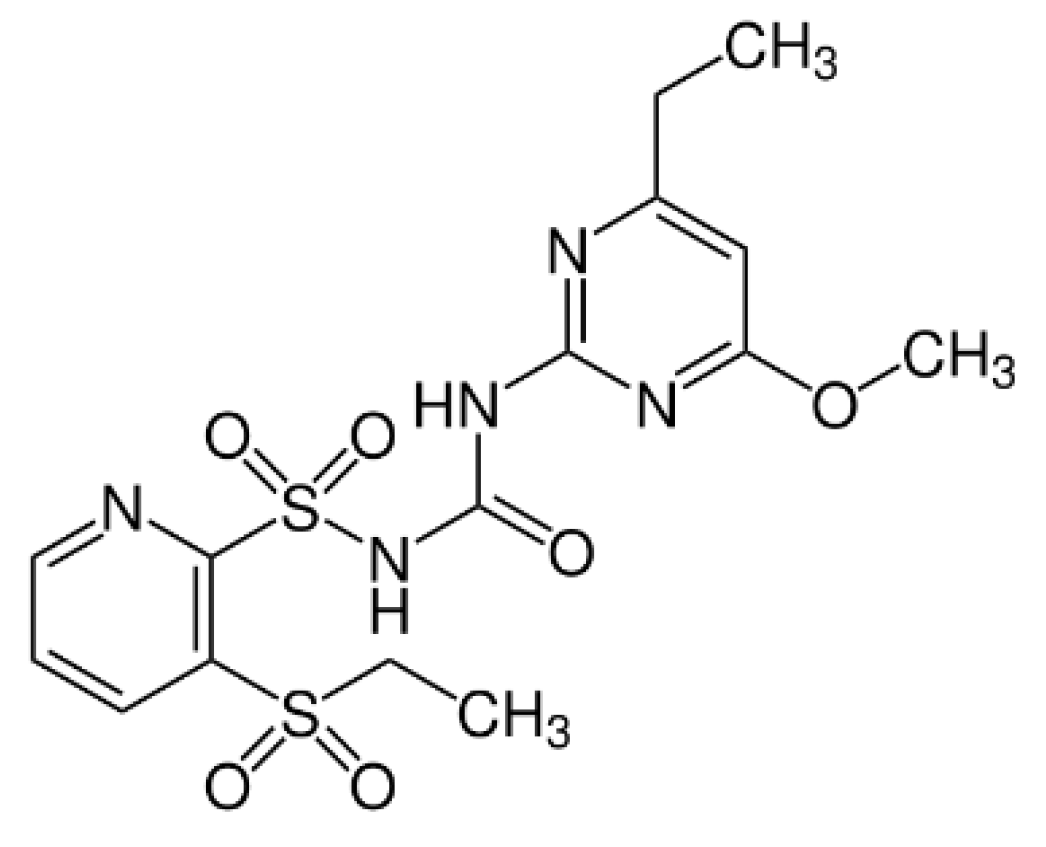

2.3.2. Rimsulfuron

Chemical names: rimsulfuron, N-[[(4,6-dimethoxy-2-pyrimidinyl)amino]carbonyl]-3-ethylsulfonyl-2-pyridinesulfonamide, N-((4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)aminocarbonyl)-3-(ethylsulfonyl)-2-pyridinesulfonamide, rimosulfuron. IUPAC name: 1-(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)-3-(3-ethylsulfonylpyridin-2-yl)sulfonylurea (

Figure 2). Chemical group: Rimsulfuron belongs to the sulfonylurea group, which is one of the classes of herbicides used in agriculture.

Molecular formula: C14 H17 N5 O7 S2. Registry Number: 122931-48-0 [

37]. Rimsulfuron is a selective herbicide. It works by interfering with the metabolic processes in weeds, causing them to die. It is available in the form of granules, liquid for solution and in mixtures with other active substances. It works by inhibiting the processes of amino acid biosynthesis, which leads to impaired growth and development of weeds. The use of rimsulfuron is subject to safety regulations for both crop and environmental protection [

36].

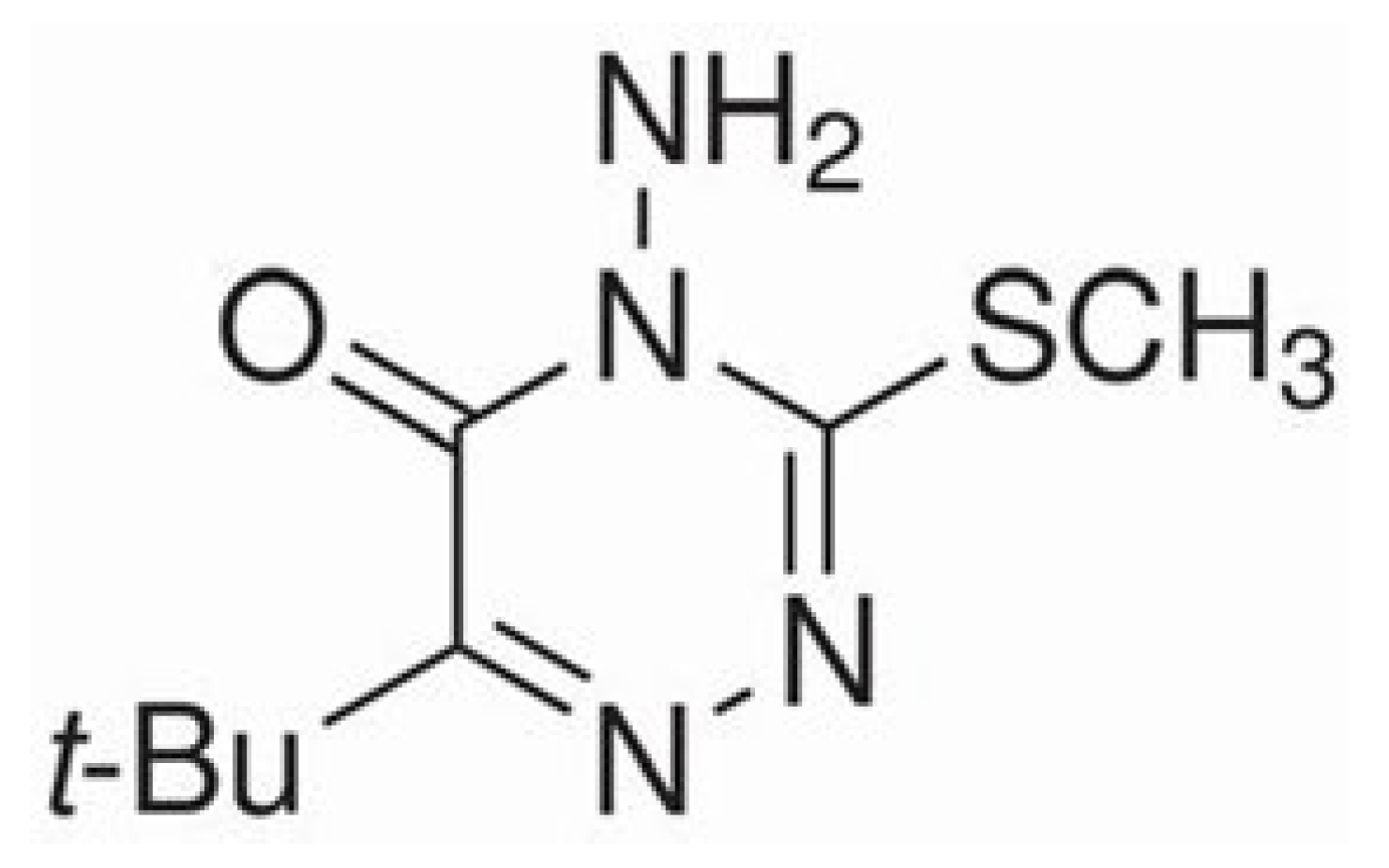

2.3.3. Metribuzin

Chemical name: 4-Amino-6-tert-butyl-3-methylthio-1,2,4-triazin-5(4H)-one, metribuzin (

Figure 3). Molecular formula: C8H14N4OS [

36]. Registry Number: 21087-64-9 [

37].

Metribuzin is a colorless, crystalline solid substance. It is used as an herbicide It belongs to the class of 1,2,4-triazines, specifically 1,2,4-triazin-5(4H)-one substituted with an amino group at position 4, a tert-butyl group at position 6, and a methylsulfonyl group at position 3. It serves as a xenobiotic, an environmental pollutant, herbicide, and an agrochemical agent. It is a member of 1,2,4-triazines, organic sulfones, and cyclic ketones [

36,

37]. Metribuzin affects the photosynthetic apparatus of plants, especially the photosynthetic reaction systems. This inhibits the ability of weeds to absorb solar energy and convert it into nutrients, which leads to the plants weakening and dying. Under its influence, weeds stop developing and their leaves may turn yellow or white, which is a sign of weakness and death. Metribuzin is a selective herbicide, it can be used both before and after weed emergence. The use of metribuzin requires caution and compliance with safety and environmental regulations to avoid negative effects on crops and the environment [

36].

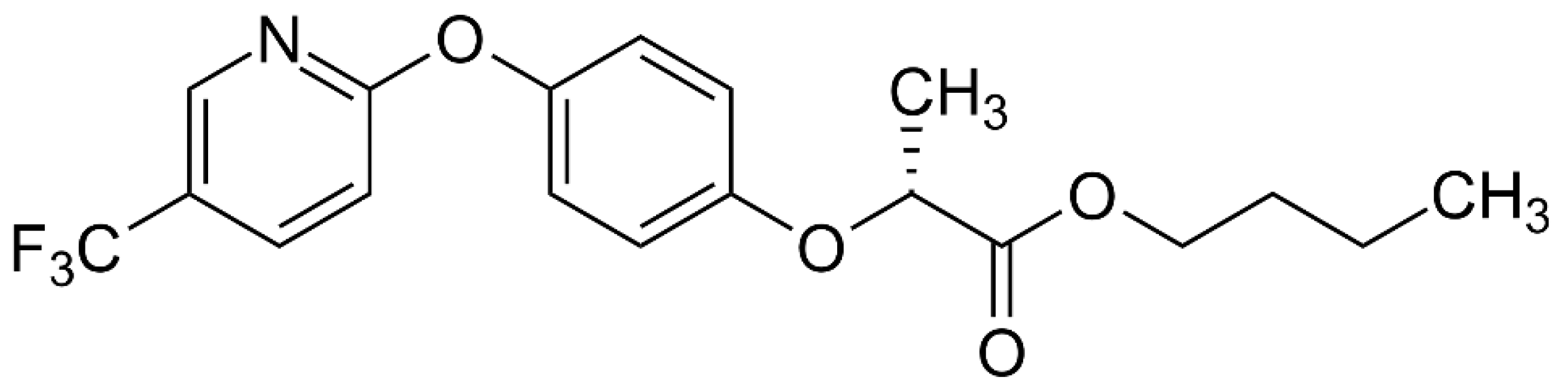

2.3.4. Fluasyfop-P-butyl

Synonyms: Fluazifop-P-Butyl; 79241-46-6; Fusillade super; Fusillade 2000; Fusillade S; Fusillade DX; Fusillade II; Fluazyfop-P-butyl [ISO]; (2R)-2-[4-[5-(trifluorometylo)pirydyn-2-ylo]oksyfenoksy]propanian butylu; N99K0AJ91S (

Figure 4). Empirical Formula (Hill Notation): C19H20F3NO4 [

36].

Chemical type: Fluazifop-P-butyl is a derivative of aryloxy phenoxy alkanoic acid. It is a selective herbicide used to control weeds without causing harm to the cultivated crops. It acts on weeds by inhibiting the growth and development of their root and above-ground systems. Fluazifop-P-butyl is available in the form of a liquid or emulsion, which is applied in agricultural fields using sprayers. It is a chemical substance that must be used following the manufacturer's recommendations and safety regulations. Fluazifop-P-butyl is available under various trade names, depending on the manufacturer and the market where it is sold [

38]. Available Data: Number: 79241-46-6 [

37]. Molecular weight: 383.36; MDL number: MFCD06199153. Substance identifier: 329753893 [

36].

In the experiment sulfosulfuron was used in the form of Apyros 75 WG; rimsulfuron – in the form of the herbicide Titus 25 WG; fluazifop – in the form of Fusilade Forte 150 EC, and metribuzin was used in the form of Sencor 70 WG. The herbicides were applied at a rate of 400 liters per hectare (ha) of water using a backpack sprayer with flat-fan nozzles, with a flow rate of 0.35–0.65 liters per minute (dm.min

-1) and a pressure of 0.1–0.2 megapascals (MPa). The treated area of the plot was 31.0 square meters [

34,

38].

2.4. Phytotoxicity assessment

The phytotoxic effects of herbicides on potato plants were assessed every 7 days, starting from the date when the first signs of damage appeared (such as leaf discoloration, yellowing, or browning) and continuing until they stabilized or disappeared (for a total of six assessments) on the EWRC scale (

Table 2).

The first assessment of the plant's condition and weed infestation was conducted when the weeds emerged in the control plots, while the potatoes were at BBCH stage 12 (development of successive leaves). The subsequent assessment was carried out seven days later - at BBCH stage 20 (beginning of lateral branching), and the final one when the rows were closing (BBCH 40). The degree of phytotoxicity of the preparation was assessed using the 9-point scale (EWRC) [

39].

At the stage of technical maturity, the potato crop was harvested using a potato elevator. The tuber yield and its structure were determined and, on this basis, the marketable tuber yield was calculated [

22,

40].

2.5. Soil assessment

Annually, prior to commencing the experiment, in accordance with the PN-R-04031 [

41] standard, 20 soil samples were collected from the arable layer (0-20 cm) to create a composite sample weighing approximately 0.5 kg. These samples were analysed to determine the soil's particle size composition, availability of phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium, as well as soil pH in accordance with the Mocek [

42]. The chemical and physicochemical properties of the soil were determined in a certified laboratory at the District Chemical and Agricultural Station in Wesoła, near Warsaw, using the following methods: soil particle size composition was determined by laser diffraction [

43]; pH was measured in a suspension of 1 mol KCl dm-3 and in a water suspension using the potentiometric method [

44]; organic carbon content (Corg.) was determined using the Tiurin method [

42]; available magnesium content was determined using the Schachtschabel method [

45] the content of absorbable forms of phosphorus and potassium was measured using the Egner-Riehm method [

46,

47].

The experiment was carried out on loamy, sandy and clay soil [

48]. The share of sand, silt and clay was 66.98%, 30.57% and 2.45%, respectively (

Table 3).

The results of soil analyses were confronted with standard values provided by the Soil Science and Plant Cultivation – National Research Institute [

49].

In the physicochemical analysis, the content of assimilable macronutrients in soil dry matter, pH value, and organic matter content in the soil were considered. The content of assimilable phosphorus (P) in 2007 was 104.2 mg kg

-1, which can be classified as moderately high. In 2008, the content of this element decreased to 42.8 mg P kg

-1, and in 2009, it further decreased to 17.1 mg kg

-1, classifying the soil as low in phosphorus. For potassium (K), the content of assimilable potassium in 2007 was high, at 183.7 mg kg

-1. In 2008, it was 139.2 mg kg

-1, and in 2009, it decreased to 61.1 mg kg

-1, making the soil potassium-deficient. Magnesium (Mg) content in 2007 was 121.3 mg kg

-1, which is considered high [

49]. In 2008, this value decreased to 92.9 mg/kg, and in 2009, it was only 35.7 mg kg

-1. Soil pH (KCl) was found to be acidic, ranging from 4.9 in 2007 to 5.3 pH in 2009. The content of organic matter (Corg) in the soil was from 7.2 to 7.5 g kg

-1. Loamy soils, due to their nature, often contain less organic matter than forest soils or peatlands. Therefore, a value of 7.4 g kg

-1 for loamy soil can be considered moderately low. These data are essential for assessing soil suitability for crop cultivation (

Table 4).

2.6. Meteorological conditions

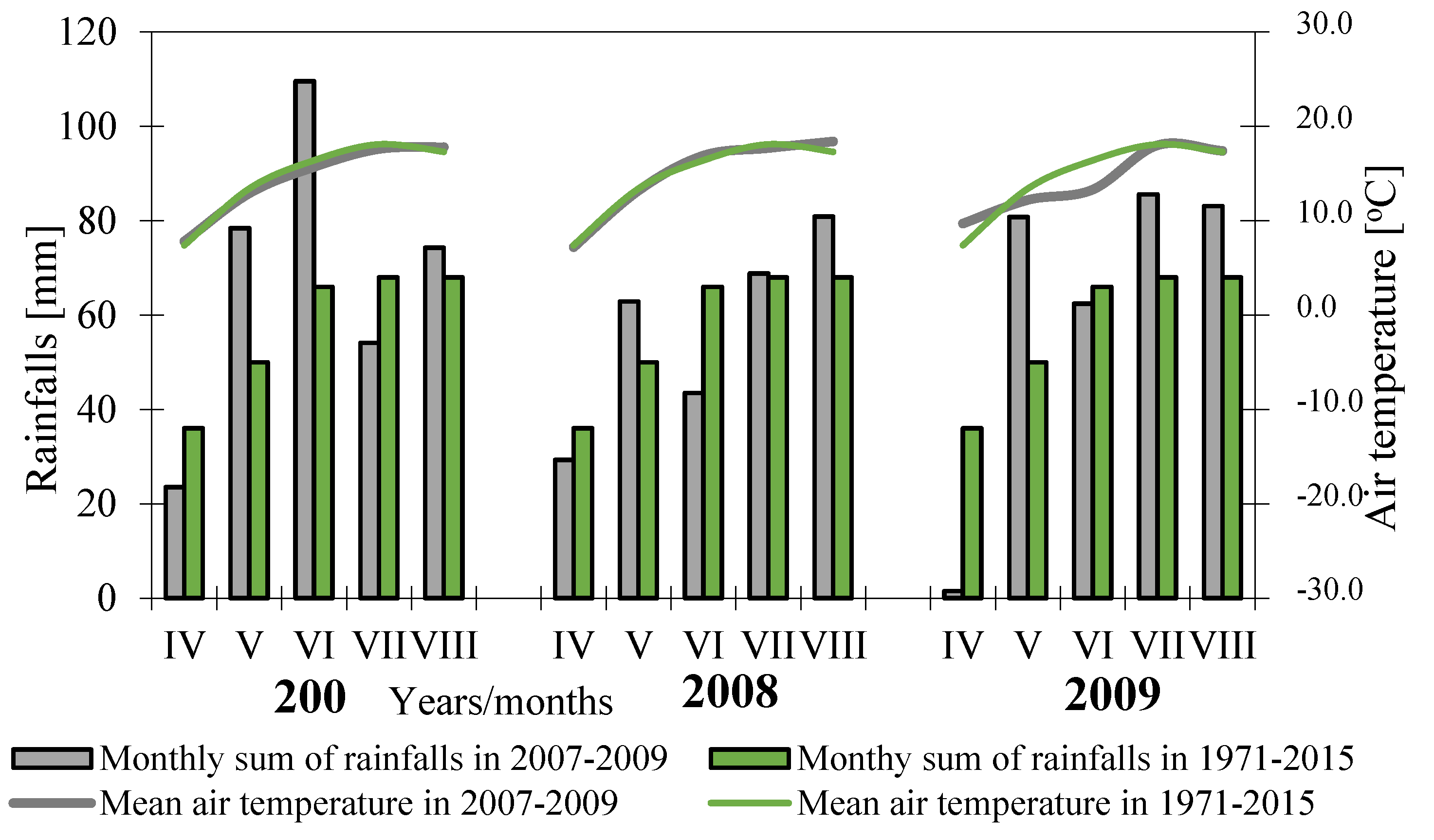

The weather conditions during the growing season in 2007-2009 were characterized by changeable air temperatures and rainfalls (

Figure 5,

Table 5).

In the years 2007-2009, the vegetation period conditions in Jadwisin exhibited varying temperatures and precipitation levels (

Figure 5). In 2007, the year could be described as relatively dry, 2008 as dry, and 2009 as having the most optimal moisture and temperature conditions for potato growth.

During the first year of the study, the average temperature from April to September was 13.7°C, which was 0.6°C lower than the long-term average. The total precipitation during this period was 436 mm, which was 165% of the long-term norm (

Figure 1).

In 2008, the weather during the vegetation period was unusual. Precipitation in May and August exceeded the long-term average, while June and July were dry, with water shortages observed in other months. The average temperature from April to September was 14.2°C, 0.3°C lower than the long-term average (

Figure 5).

The meteorological conditions in the 2009 vegetation period were diverse, but the main characteristic was drought at the beginning. The average temperature from April to September was 15.3°C, within the long-term norm, while the total precipitation during this period was 360 mm, which was 4.3 mm lower than the long-term average. Precipitation in the second half of the vegetation period was well-distributed over time (

Figure 5).

The values of the Selyaninov’s hydrothermal coefficient are calculated from the formula [

50]:

where:

P − sum of monthly precipitation in mm,

Σt − monthly total air temperature. Sum of precipitations and temperatures in the period, when the temperature has not been lower than 10°C.

According to the Selyaninov’s hydrothermal coefficient, the potato vegetation period was classified as wet (2007), dry (2008) and optimal (2009). In 2007, drought was recorded in April and July, while the remaining months were humid. The year 2008 was characterized by an optimal moisture content, but in June, during the period of intensive harvesting, dry conditions prevailed. In 2009, during potato planting and harvest, drought was recorded, while in the remaining months of the growing season were moist (

Table 5).

2.7. Statistical calculations

The statistical calculations were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.2. [

51]. The statistical analyses were based on a three-factor model (years x cultivars x maintenance) of analysis of variance (ANOVA), as well as multiple t-Tukey tests (or confidence intervals). The significance level was set at p≤0.05. The significance of sources of variability was assessed using the Fisher-Snedecor test, known as the "F" test. For variables expressed in percentages that were close to 0 or 100, normalizing transformations were applied using the natural logarithm (ln

x). After the calculations, the data were retransformed.

The logarithmic transformation of a random variable x is described by the formula:

where g(

x) = ln(

x) [

52].

In practice, logarithmic transformation is often used to adjust the distribution of data to meet statistical assumptions, especially when the data exhibit a nonlinear relationship or a skewed distribution. The results of the statistical analysis using these methods can help in better understanding the relationships between variables and assessing the significance of differences between groups or conditions. Moreover, descriptive statistics and calculations of Pearson’s simple correlation coefficients [

53] were used.

3. Results

3.1. Coverage of soil with crops and weeds

The soil coverage by potato plants averaged 95.5%, single-leaf weeds accounted for 2.4%, and two-leaf weeds for 12.1% (

Table 6).

Varietal characteristics and the study years did not significantly differentiate the soil coverage by the crop. However, the cultivation methods had a significant impact. The highest soil coverage by the crop was observed in the treatment where Sencor 70 WG + Fusilade Forte 150 EC was applied after potato emergence, while the lowest coverage was in the control treatment without any cultivation. In the field of ‘Irga’ potato cultivar, a higher degree of soil coverage by both single-leaf and two-leaf weeds was observed, while the coverage by the crop plants was lower compared to the ‘Fianna’ cultivar field. The response of potato plants to the applied herbicides was not significantly related to the genetic properties of the studied cultivars (

Table 6).

3.2. Damage to potato plants

Herbicide damage to potato plants was predominantly influenced by the chemical weed control method applied in the experiment (

Table 7). Greater changes in leaf blade damage were observed after the POST application of herbicides compared to PRE application for potatoes. The highest level of damage was recorded when the herbicide Sencor 70 WG was applied POST at a rate of 0.5 kg ha

-1. On the other treatment plots, the values remained at a similar level and were homologous in terms of the examined characteristic. The PRE use of the herbicide mixture, Sencor 70 WG + Titus 25 WG + Trend 90 EC, resulted in more significant discoloration of leaf blades compared to the application of a single active herbicide substance such as metribuzin (

Table 7).

3.3. Damage to weeds

The average degree of damage to dicot weeds was 3.1° on the 9° EWRC scale (

Table 8). Genetic characteristics of the examined cultivars and weed control methods did not significantly differentiate the extent of damage to this group of weeds. Instead, the weather conditions during the study years had the most significant impact on the damage to dicot weeds in the crop field. The highest effectiveness in reducing dicot weed damage was achieved in 2009, while the lowest was observed in 2008. This was mainly due to the weather conditions during the potato's growing season (

Table 8).

Significant interaction between maintenance methods and years was also observed. Only in maintenance methods 4 to 8 (Sencor PRE and POST in different combinations with herbicides), significant differences in weed reduction were identified during the study years. The most pronounced herbicidal effect was observed in the optimal year of 2009, while the weakest effect was seen in the dry year of 2008 (

Table 8).

The average degree of damage to monocot weeds was 2.1° on the 9° EWRC scale (

Table 9). Potato maintenance had the most significant impact on the damage to this weed class. All mechanical-chemical maintenance methods increased the damage compared to mechanical maintenance. The most significant phytotoxic damage was observed in monocot weeds after the application of the herbicide mixture Sencor + Apyros + Atpolan, followed by the use of preparations: Sencor + Fusilade Forte, while the least damage was caused by mechanical-chemical maintenance involving the Sencor PRE preparation (

Table 9).

Meteorological conditions during the study years also influenced the degree of damage to monocot weeds. The most significant symptoms of phytotoxic damage in this group of weeds were observed in 2009, a year characterized by a very wet May, while the least damage was observed in 2008, a year with a warm and dry period during plant emergence. Meteorological conditions during the potato vegetation period modified the damage to monocot weeds only in weed control methods from 5 to 8. The most substantial reduction in weed infestation was achieved in 2009, which was optimal for potato yields, while the lowest reduction was observed in the dry year of 2008 (

Table 9).

3.4. Yield of tubers

The total and commercial yields of tubers were determined. The commercial yield accounted for 93.4% of the total yield. The genetic characteristics of the studied cultivars only differed in the commercial potato yield. The moderately late cultivar '‘Fianna’' proved to be more productive than the moderately early cultivar '‘Irga’' (

Table 10).

The methods of potato cultivation influenced both the total yield and the commercial yield of tubers. The best yield results in both cases were achieved by using the Sencor 70 WG preparation PRE, at the recommended dose (1 kg ha

-1). In the case of the commercial yield, all other combinations with herbicides were comparable to the PRE application of the Sencor preparation, as well as with mechanical potato cultivation

Table 10).

Regarding the total yield, objects 2 to 4 and 6 to 8 showed homogeneity in terms of this trait, while object 5, with the application of Sencor POST at a reduced dose (0.5 kg ha

-1), exhibited significantly lower total yield but significantly higher yield compared to the control object and the mechanically cultivated object (

Table 10).

The values of the total and commercial yield were primarily influenced by meteorological conditions during the years of the study. The highest values of these traits were obtained in 2009, an optimal year in terms of moisture and thermal conditions during the potato vegetation period. Homogeneous values of the total and commercial yield were achieved in 2008, characterized by a favorable period shortly before and after potato emergence, along with better meteorological conditions in the second half of the vegetation period. The lowest yield for both traits was obtained in 2007, a flood year with excessive rainfall in June and September (three times higher than the long-term average) (

Table 10).

Only in the case of the commercial yield did the tested cultivars exhibit a varied response to meteorological conditions during the study years. The cultivar '‘Irga’' achieved the highest yield in 2008, while the mid-late cultivar '‘Fianna’' achieved its best yield in 2009, a year that was optimal in terms of moisture and thermal conditions. Both cultivars, however, produced the lowest yield in the flood year of 2007 (

Table 10).

3.5. Descriptive Characteristics of Potato Plant Yields and Phytotoxic Damage

Table 11 offers a comprehensive view of the descriptive statistics related to potato yield and phytotoxic damage. It encompasses both dependent and independent variables:

Dependent variable y1 (total yield): The average total potato yield stands at approximately 30.2 t ha

-1 with a standard error of 0.77. The median is 28.80, while the standard deviation is 9.28 t ha

-1. The total yield data exhibits slight negative skewness (0.02), and the kurtosis is -0.51. The total productivity ranges from 9.48 to 51.84 t ha

-1, and the coefficient of variation is 30.74%, indicating relatively high stability in the value of this feature. Practically, this means that total potato yield values deviate by approximately 30.74% from the average. A larger coefficient of variation implies greater data variability (

Table 11).

Similarly, marketable yield (y2): The average marketable yield is 28.27 t ha

-1 with a standard error of 0.79. The median market yield is 26.89 units, and the standard deviation - 9.49. Market yield data also exhibits slight negative skewness (-0.01), with a kurtosis of -0.50. Marketable yield ranges from 6.30 to 49.37 t ha

-1, and the coefficient of variation for this feature is 33.56%. A coefficient of variation (CV) of 33.56% indicates significant variability concerning its average value. In the dataset, marketable potato yield may vary due to factors such as growing conditions, soil, diseases, or pests. A high coefficient of variation can imply greater yield-related risk, impacting farmers' incomes. To stabilize yields and incomes, measures can be taken to minimize this variability (

Table 11).

Independent variables (x1 to x6) (phytotoxic damage at different time points): These variables represent phytotoxic damage levels at varying time intervals (7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days). Phytotoxic damage of cultivated plants increases over time, with x1 having the highest mean (2.42) and x6 having the lowest mean (0.79). Standard deviations also increase, indicating greater variability. Positive skewness values suggest right-skewed distributions, with x4 being the most positively skewed (skewness 1.98). Kurtosis values vary, with relatively high kurtosis values for x5 (4.84) and x6 (0.11), indicating heavier tails in their distributions. The ranges of phytotoxic damage values also expand over time (

Table 11).

In summary, the descriptive statistics offer a comprehensive view of total and marketable potato yield and the progression of phytotoxic damage over different time points. These statistics reveal insights into central tendencies, variability, and data distributions for each parameter.

3.6. The Relationship Between Potato Yield and Phytotoxic Damage in Plants

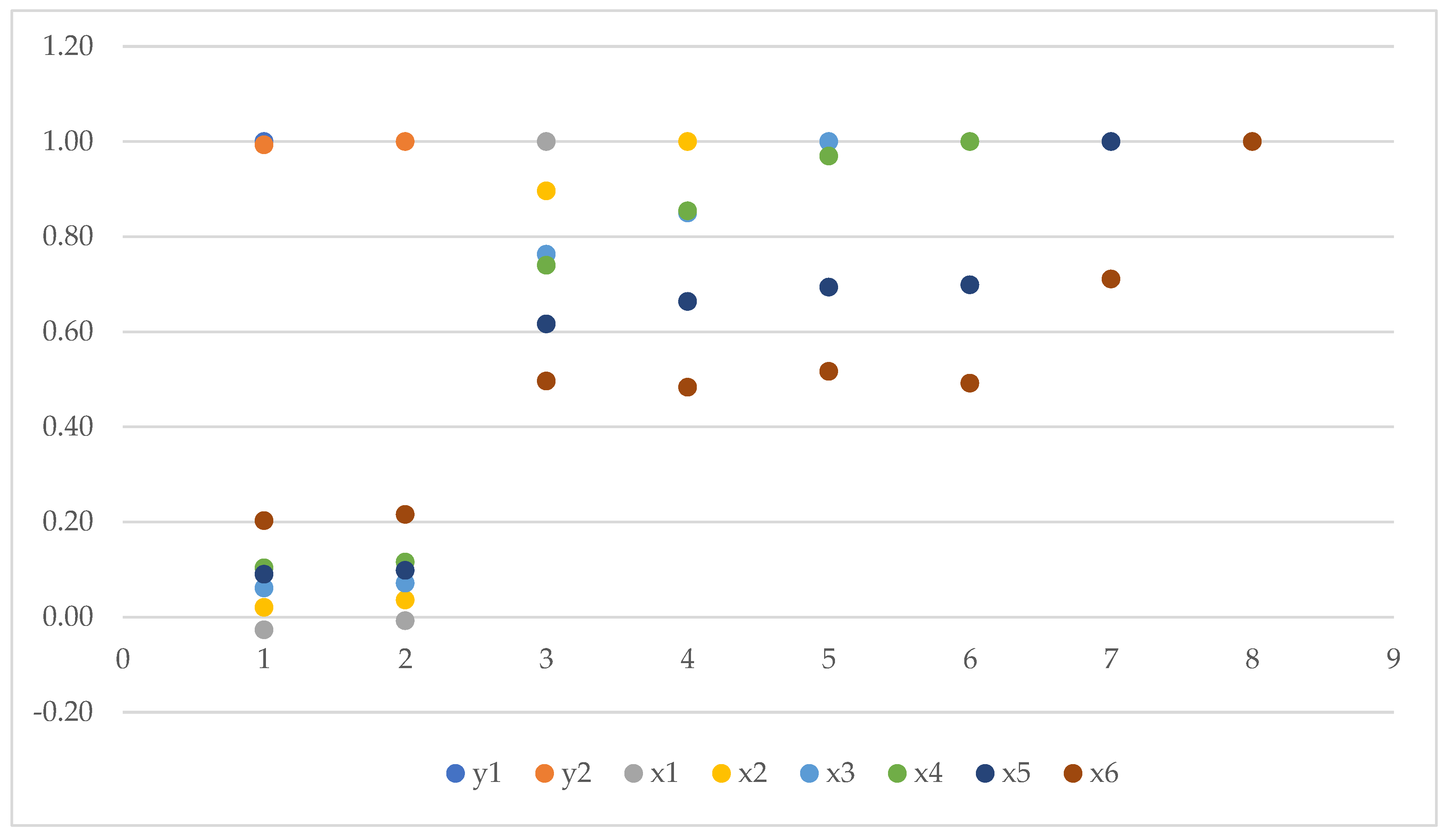

Figure 6 presents Pearson's correlation coefficients between various variables, including total and marketable potato yield and the degree of phytotoxic damage to potato plants at different time intervals after herbicide application.

For total potato yield (y1), the correlation between total yield and marketable yield was r=0.99, indicating a strong positive correlation, suggesting that changes in one of these parameters go hand in hand with similar changes in the other (

Figure 6).

The correlation between total yield and the degree of phytotoxic damage to potato plants at various time intervals is very weak and close to zero (ranging from -0.03 to 0.20). This suggests that there is no clear correlation between total potato yield and the degree of phytotoxic damage in the observed periods, except for damage observed after 42 days from the first herbicide application. For marketable potato yield (y2), the correlation with the degree of phytotoxic damage is also very weak and close to zero (

Figure 6).

Regarding the degree of phytotoxic damage (x1 to x6), the correlation between different time intervals of phytotoxic damage is generally positive and moderate, indicating that the degree of plant damage increases over time (

Figure 6).

In summary, the results indicate a strong correlation between total and marketable potato yields, as expected, given that both variables should be closely related. However, the lack of a clear correlation between yield and the degree of phytotoxic damage suggests that phytotoxicity has a limited impact on yield within the observed range.

4. Discussion

In conditions of intensive potato cultivation technology, plants are exposed to the influence of various stressful conditions that often hinder the realization of physiological processes at the potential capacity of this species. It is known that herbicides can translocate from leaves and stems to fruits, seeds, tubers, and accumulate within them, altering their physiological, biochemical, and consumable properties [

14,

19,

25,

54,

55,

56]. Herbicides can induce enduring or transient alterations in the morphology of potato plants [

10,

57,

58]. The extent of damage is not necessarily linked to the spectacular appearance of damage symptoms.

4.1. Phytotoxicity of herbicides and its effects

The consequences of herbicide phytotoxicity for yields, as stated by [

10,

11,

19,

27,

58,

59], can be better assessed based on the time of herbicide application and the duration of symptoms rather than their intensity. The response of potato plants to applied herbicides is also dependent on various factors, such as genetic characteristics of cultivars, the timing of application, air temperature during application, post-application precipitation, and soil organic matter content [

10,

16,

19,

54,

58,

60,

61]. Phytotoxic reactions in plants are most commonly observed when herbicides are applied after potato emergence [

55,

56,

59]. In the conducted research, POST herbicide applications (such as metribuzin) resulted in more significant changes in potato plants, visible on leaf blades, than those used for PRE weed control. According to Lichtenthaler [

57,

62,

63,

64], herbicides disrupt the course of photosynthesis, enzymatic processes, damage chlorophyll, induce excessive transpiration, and inhibit cell division. Much greater damage caused by foliar application of the herbicide's active ingredient was observed in the case of chlorophyll b than chlorophyll a. The average decrease in chlorophyll b content was about 140% compared to undamaged control plants. The phytocide changes subsided after about 6 weeks but caused irreversible damage to the plant's assimilation apparatus. Most active ingredients of herbicides (e.g., clomazone) inhibit the biosynthesis of pigments. According to Skórska and Swarcewicz [

11,

65,

66], the active substances in herbicides can easily penetrate chloroplasts, causing damage to photosystem II and the light-harvesting complex (LHC). According to these authors, herbicides also disrupt the chlorophyll a:b ratio and reduce the activity of electron carriers. As a result, changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters occur [

62,

64,

65,

66]. Pszczółkowski et al. [

40] demonstrated the impact of microorganisms on the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus of potato. A decrease in the induction of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters indicates reduced efficiency of primary photosynthesis reactions in photosystem II. In the conducted research, the most significant phytotoxic damage to potato plants was found in cases where metribuzin was the active ingredient, applied after potato emergence. The most severe phytotoxic symptoms on potato plants, as well as a lower level of soluble solids and reduced potato yields after metribuzin, dichlozoline, and imazethapyr application, were also reported by Fonseca et al.[

7]. Therefore, the herbicides they examined were considered less selective. Linuron and clomazone had no effect on the level of soluble solids in their research and did not reduce potato yields; thus, they were considered more selective for this species. [

67] examined the effectiveness of weed control in sweet potato cultivation and phytocides effects of using bentazon. However, they did not observe any phytotoxic symptoms on sweet potato plants after applying this preparation. The evaluation of POST damage caused, among others, by metribuzin in Romania was conducted by [

68]. However, they did not observe any post-herbicide damage to potato plants. Other active substances of herbicides (haloxyfop-R (methyl ester), setoxydim, oxyadargil, bentazon, oxyadiazon, and oxyfluorfen) were examined by [

69] on common valerian plants [

Valeriana officinalis L.]. The most harmful effects of herbicides were caused by the application of oxyfluorfen, followed by bentazon, and the effects increased with the higher doses of preparations. Oxadiazon, on the other hand, caused significant damage only after 30 days from application. Other herbicides did not show any significant damage at any time after application compared to the control treatment. Sensitivity of potato cultivars to metribuzin and fomesafen applied before potato emergence was studied by Tkach and Golubev [

58]. They observed phytotoxic symptoms only in early cultivars, Udacha and Nevsky. For the Avrora cultivar, they only found a negative impact on plant height due to metribuzin and formesafen application, resulting in a significant growth delay. Despite the observed phytotoxic symptoms, these authors did not demonstrate any negative effects on the yield of the tested potato cultivars. Phytotoxic symptoms caused by urea-based herbicides include chlorotic changes that subsequently transform into necroses [

10,

11,

56,

58,

70].

Currently, research on phytotoxicity focuses on identifying target processes shaped by allelochemicals present in acceptor plants or isolating specific chemical compounds from donor plants. Despite the numerous advantages of advanced biotechnological and omics techniques, they have not been widely utilized for a comprehensive understanding of phytotoxicity. While some genetic studies on allelopathy and phytotoxicity have been conducted [

71,

72], only a few have focused on identifying the fundamental genetic mechanisms and global gene expression changes related to these processes [

72,

73]. To date, there is a lack of research aimed at determining the genetic or molecular basis of the benefits arising from positive allelopathic interactions. This is highly significant because this origin may play a key role in shaping the ability of allelopathic interactions to influence potato yields and its competition with weeds.

Research conducted by Szajko et al. [

73] analysed the distribution of phytotoxicity and glycoalkaloid content in a diploid potato population, attempting to explain the source of phytotoxic variability among plants. In comparison to white mustard, a plant species used as a reference point, potato leaf extracts contained six different glycoalkaloids, namely solasonine, solamargine, α-solanine, α-chaconine, leptinine I, and leptinine II. The glycoalkaloid profiles of high phytotoxicity potato offspring significantly differed from those of low phytotoxicity offspring. RNA sequencing analysis revealed that low phytotoxicity offspring exhibited increased expression of genes related to flavanol/3-hydroxylase synthesis, influencing plant growth. This demonstrates that metabolic changes in potato offspring can affect various physiological responses in the recipient plant, including white mustard. Phytotoxicity is not solely related to the quantity of glycoalkaloids but also to their composition and the presence of other metabolites, including flavonoids. Consequently, it is suggested that diverse factors, including glycoalkaloids and flavonoids, may influence plant phytotoxicity [

72,

74]. Phytotoxicity is a key aspect in agriculture to maintain the balance of ecosystems. Research on the mechanisms of phytotoxicity and its impact allows the development of effective strategies for plant and environmental protection.

4.2. Mechanisms of Phytotoxic Action

Herbicides from various chemical groups exhibit diverse mechanisms of phytotoxic action. They interact with different plant life processes [

75]. According to [

57], urea herbicides are more readily absorbed through roots than leaves and move within the plant, disrupting the process of photosynthesis. Selective systemic herbicides like Sencor move through the xylem and interfere with photosynthesis, affecting a broad spectrum of both monocot and dicot weed species. [

29] found that the active ingredients in these herbicides hinder the early stages of photosynthesis by inhibiting water photolysis. By acting as electron transport inhibitors in the light phase of photosynthesis, they generate active oxygen species, which react with the lipid-protein components of plasma membranes, ultimately damaging chloroplast structures.

Rimsulfuron, an active ingredient with systemic action, is absorbed through the leaves and swiftly moves throughout the plant, inhibiting weed growth by disrupting the biosynthesis of amino acids. Rimsulfuron is selective to potatoes, making it relatively safe for this crop. Its herbicidal effect becomes noticeable after 7-20 days post-application. Rimsulfuron operates through systemic selectivity, which means that the potato plant breaks it down into inactive compounds [

28,

33,

76]. According to [

77], rimsulfuron is commonly used for controlling

Chenopodium album L. and

Amaranthus retroflexus L. in potato fields. Investigating the absorption and metabolic patterns of rimsulfuron between these two weed species and potatoes can provide valuable insights for optimizing herbicide application in the field. Redroot pigweed (

A. retroflexus L.), the most sensitive species in their study, showed the highest absorption rate and the lowest herbicide metabolism rate. Potatoes proved to tolerate rimsulfuron well. The combination of active substances rimsulfuron (Titus 25 WG) and metribuzin (Sencor 70 WG) in the study resulted in more severe damage to both potato plants and weeds when applied POST rather than PRE. [

28] and [

77] observed similar effects. This combination was intended to enhance the control of monocot weeds in potato cultivation. Rimsulfuron interrupted lipid processes, whereas metribuzin disrupted photosynthesis. Together, these active substances seemed to act synergistically, achieving a more effective weed control compared to each one applied individually.

Apyros 75 WG, containing the active substance sulfosulfuron, is absorbed through both roots and leaves, moving throughout the plant, where it acts as an amino acid biosynthesis inhibitor. Amino acids like valine, isoleucine, and leucine are vital for plant growth and development [

6,

78]. By interfering with the production of these amino acids, sulfosulfuron hinders cell growth and leads to a decline in plant yield. In the study, sulfosulfuron caused higher damage to potato plants of the ‘Irga’ cultivar compared to ‘Fianna’. It also induced more damage in monocot weeds than dicot weeds. Sulfosulfuron degrades rapidly in the soil, leading to decreased damages in

Amaranthus aegyptiaca, affecting weed control. However, its use negatively affected potato tuber yield, reducing it significantly.

Fluazifop-P-butyl (Fusilade Forte 150 EC), an aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicide, actively moves within the plant and accumulates in root stems and rhizomes. It disrupts various biochemical processes in plants, particularly inhibiting lipid production, which is crucial for monocot weeds compared to cultivated dicot plants [

36,

57,

75]. Metribuzin, on the other hand, impacts the photosynthesis process, leading to plant damage [

57]. In the conducted study, combining fluazifop-P-butyl with metribuzin led to the highest damage to weeds compared to the mechanical-chemical control group. The potato cultivar '‘Irga’' proved more sensitive to this combination than the relatively late-maturing '‘Fianna’.' This synergy helped control monocot weeds more effectively, contributing to better crop yield and quality [

68,

77].

The sensitivity of potato cultivars to the herbicides and their mixtures varied. Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers were useful for differentiating sensitive and tolerant populations at a molecular level. SSRs, also known as microsatellites, are DNA sequences consisting of short, repeating nucleotide motifs. They are used as genetic markers for genetic diversity analysis, parent identification, gene mapping, and other genetic research purposes. EST-SSRs, or Expressed Sequence Tag-SSRs, are particularly suitable for genetic and genomic studies at both intra- and inter-species levels [

74].

Dittmar et al. [

79] assessed the toxicity of metribuzin on potato plants and recorded reversible damage at 8%. Stressed conditions like prolonged drought, excessive rainfall, flooding, heavy metals, or soil salinity can cause chloroplast membrane disorganization, directly affecting the efficiency of photosystem PS II. In such cases, reparation is facilitated by the short-lived nature of stress and the early growth phase of potato plants [

40].

The active substance metribuzin can affect plants in various ways, such as inhibiting photosynthesis, disturbing metabolic processes, inhibiting cell division, impeding the movement of water and nutrients, and acting both PRE and POST. Metribuzin's impact may differ depending on concentration, weed species, and environmental conditions. It should be used in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations and safety and environmental protection regulation.

4.3. Impact of Environmental Conditions on Herbicide Phytotoxicity

Environmental conditions significantly influenced the risk of herbicide toxicity. The existing relationship between weather patterns and the sensitivity of plants of this species to herbicides indicates that it is largely determined by post-application habitat conditions in unfavorable meteorological and soil conditions. These observations, concerning potato plants, are supported by [

10,

11,

54,

59]. According to [

19], increased herbicide phytotoxicity concerning potatoes may occur in wet and cool years when plants are less resilient to adverse weather conditions. In the opinion of [

13,

25,

54,

80], low temperatures and low precipitation may create less favorable conditions for herbicide degradation in the soil, thereby increasing their phytotoxicity. Conversely, high levels of rainfall during potato planting, emergence, and vigorous vegetative growth can increase their sensitivity to herbicides. According to [

11], strategic deep soil tillage increases damage caused by certain herbicides, including those containing metribuzin as the active substance. According to [

81], often different yield constraints occur simultaneously and can appear on both the topsoil and subsoil, associated with both fine and coarse-textured soils. While some substrate constraints reflect the inherent nature of the soil, others occurring in the upper 0.5 m of the soil profile, such as soil acidity or compaction resulting from machinery practices, result from agricultural management.

Prudent herbicide use in potato production is crucial because their improper use induces stress in plants, potentially leading to growth and development disruptions. The extent of the stress depends on the type of active substance, application timing, conditions, fertilization, and the genetic properties of cultivated plants.

4.4. The Impact of Varietal Traits on Phytotoxic Damage in Potatoes

The susceptibility of potatoes to phytotoxic damage can be influenced by various varietal traits. Research has shown that different potato cultivars exhibit varying levels of sensitivity to herbicides, and this sensitivity is often associated with specific varietal characteristics. The following varietal traits can influence phytotoxic damage in potatoes:

Genetic Factors: The genetic makeup of potato cultivars plays a significant role in determining their susceptibility to phytotoxicity. Some cultivars may possess genetic traits that make them more resistant to the effects of herbicides, while others may be more sensitive. Research has demonstrated genetic diversity among potato genotypes, which can explain variations in phytotoxic responses [

19,

54,

56,

59,

60,

80]

Growth Habit: Cultivars with different growth habits, such as determinate or indeterminate growth, may exhibit varying sensitivities to herbicides. Determinate cultivars tend to have limited vegetative growth and may be less affected by herbicides that target vegetative growth processes [

22].

Tuber Formation: Varietal traits related to tuber formation, such as the number, size, and depth of tubers, can affect how potatoes respond to herbicides. Cultivars with deeper or larger tubers may be less vulnerable to herbicide damage because the tubers are further below the soil surface [

11].

Leaf Morphology: Differences in leaf structure and morphology among potato cultivars can impact their susceptibility to herbicides. Cultivars with thicker or waxy leaves may provide some protection against herbicide absorption, reducing phytotoxic effects [

19,

72]. [

19] examined the influence of the number of stomata on the damage to potato plants after POST metribuzin application. He demonstrated that the leaf structure of the studied potato cultivars had a significant effect on the intensity of phytotoxic symptoms and the pace of their reduction.

Maturity: Early-maturing and late-maturing potato cultivars may respond differently to herbicides. The growth stage at which herbicides are applied can affect the extent of damage. Early-maturing cultivars may be more sensitive to herbicides applied during the early growth stages [

54,

80,

82]. In the conducted studies, the mid-late cultivar '‘Fianna’' demonstrated a better response to phytocides damage compared to the mid-early cultivar '‘Irga’.'

Stress Tolerance: Cultivars that are more stress-tolerant may recover more effectively from herbicide-induced stress. Some cultivars exhibit better resilience to adverse environmental conditions and herbicide-related stress [

14,

26,

62,

63,

72,

82].

Metabolic Traits: Varietal differences in metabolic processes can influence how herbicides are processed and detoxified within the plant. In the case of our own research, the cultivar ‘‘Fianna’’ was characterized by a faster rate of metabolism than ‘‘Irga’’. Cultivars with efficient metabolic pathways may be less affected by herbicides [

4,

82].

Nutrient Uptake: Cultivars with variations in nutrient uptake and utilization may respond differently to herbicides. Adequate nutrient levels can enhance a plant's ability to recover from herbicide stress [

14,

26,

72]. In the conducted research, various fertilizers were utilized, including the foliar fertilizer, which included phosphorus, potassium, as well as acetate ions, and had a strongly alkaline pH (pH 14.5). This alkaline pH hinders pathogen development and reduces the potato's response to stress, which could have contributed to enhancing the resistance of the studied cultivars to phytocides stress.

Understanding the influence of these varietal traits on phytotoxic damage is crucial for selecting appropriate potato cultivars and implementing effective herbicide management strategies. Different cultivars may respond differently to herbicide treatments and environmental conditions, so choosing the right cultivar for specific growing conditions is essential to minimize phytotoxic effects and maximize potato yields.

The herbicide resistance of potato cultivars is a highly valuable attribute, denoting the capacity of certain cultivars to withstand the phytotoxic effects of herbicides. This resistance can be attributed to specific genetic characteristics that enhance these cultivars' ability to endure herbicide applications more effectively, enabling precise weed control without causing substantial crop damage. Extensive research on potato cultivar resistance to the active substance metribuzin has been conducted by [

19,

54,

56,

59,

80], and others. Based on our own research and that of other authors [

19,

22,

22,

56,

59], it has been established that the fundamental aspects of potato cultivar resistance to herbicides encompass:

Genetic Basis: The herbicide resistance of potato cultivars is genetically determined. Certain potato cultivars possess inherent genetic traits that render them less susceptible to the toxic effects of herbicides. These traits are often inherited and transmitted through the breeding process [

59,

72].

Herbicide-Tolerant Cultivars: Some potato cultivars have been developed or selected specifically for their herbicide resistance, and these are referred to as herbicide-tolerant cultivars [

74].

Resistance Mechanisms: These mechanisms operate at the genetic and biochemical levels and may encompass reduced herbicide uptake, enhanced herbicide detoxification, modified target site sensitivity, or a combination of these factors [

32,

74,

83].

Selective Herbicides: Herbicide-resistant potato cultivars are typically developed for use with specific herbicides that effectively control problematic weeds while having minimal impact on potato yields. This selective approach permits efficient weed management without harming the potato crop [

72].

Monitoring and Adaptation: Growers employing herbicide-resistant potato cultivars must continually monitor weed populations and adapt their weed control strategies. This practice helps prevent the development of herbicide-resistant weeds and maintains the long-term efficacy of herbicides [

34].

In summary, the herbicide resistance of potato cultivars is a valuable tool for effective weed management, while minimizing damage to potato crops. It is the result of genetic traits and extensive research, empowering farmers to use herbicides more efficiently and sustainably in potato cultivation. However, prudent herbicide resistance management is crucial to ensure its long-term effectiveness and sustainability.

4.5. Dependence of yield on phytotoxic damage

The results presented in this manuscript provide valuable insights into the characteristics of potato yields and the degree of phytotoxic damage caused by herbicide applications.

Phytotoxic damage decreases over time: Over the observed time intervals (x1 - x6), the data showed a positive yet moderate correlation between time and the extent of plant damage. This suggests that as time progresses, phytotoxic damage tends to decrease.

Strong correlation between total and marketable yield: A significant finding was the very strong correlation observed between total and marketable potato yields, with a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of 0.99. This strong positive correlation indicates that variations in one of these yield parameters closely correspond to similar variations in the other.

Limited correlation between yield and phytotoxic damage: conversely, the correlation between total yield (y1) and phytotoxic damage at various time intervals exhibited very weak correlations, ranging from -0.03 to 0.20. This implies little to no clear relationship. The same trend was observed for marketable yield (y2) (r=0,01 to 0.22). These results suggest that phytotoxic damage does not significantly impact yield within the observed range. A similar correlation between phytotoxic damage and potato yield was observed by [

13,

14,

21,

25,

26,

80]. According to [

50,

84], the main cause of the decline in potato yield in Poland are agrophenological factors, and mainly delay in the potato planting date, delay in emergence, delay in tuberization and flowering may contribute to a decline in potato yield by 10 to 16%, in relation to for a long-term crop.

The analysis results indicate a strong correlation between total and marketable potato yields, which aligns with expectations since these variables are inherently related. However, there is limited evidence supporting a clear correlation between potato yields and the degree of phytotoxic damage caused by herbicides. This suggests that, within the observed range, herbicide-induced phytotoxicity has a limited impact on potato yield. The robust correlation between total and marketable yield can be beneficial for farmers, as it allows for more accurate predictions of marketable yield based on total yield. Additionally, the data highlights that phytotoxic damage becomes less visible over time, providing essential insights into the potential effects of herbicide applications on crop health. It's important to note that these findings are specific to the dataset and conditions under examination, and further research may be necessary to extend these conclusions to different scenarios.

The analysis of Pearson's correlation coefficients reveals some important findings regarding the relationship between potato yield and phytotoxic damage in plants. While a strong positive correlation exists between total and marketable potato yields, suggesting that changes in one parameter are closely associated with similar changes in the other, the degree of phytotoxic damage shows a very weak correlation with potato yield. This indicates that the phytotoxic damage to potato plants, observed at different time intervals after herbicide application, has a limited impact on the overall yield within the observed range. Potato growers and researchers should be aware that the effects of phytotoxicity on yield are relatively minor in comparison to other factors that influence potato production.

5. Towards the Future

In studies of herbicide phytotoxicity in the context of potato cultivation, significant aspects regarding plant reactions to these substances and the influence of environmental conditions on phytotoxicity risk have been emphasized. Here is a summary and a challenge for the future.

Phytotoxicity of herbicides and genetic variation: Research has shown that different potato cultivars exhibit varying sensitivity to applied herbicides. There is a need for further research to identify the genes and genetic mechanisms influencing this sensitivity and to use this knowledge in breeding potato cultivars with greater herbicide tolerance.

Impact of environmental conditions: Weather and soil conditions are crucial for the influence of herbicides on potato plants. Studies demonstrate that low temperatures, low rainfall, or excessive rainfall can increase herbicide phytotoxicity. It is worthwhile to continue researching this aspect to better understand how different environmental conditions affect plant reactions to herbicides.

Role of biostimulants and secondary substances: Research into interactions between herbicides and other chemical compounds in potato plants, such as glycoalkaloids and flavonoids, is essential. It is valuable to investigate how these substances affect herbicide phytotoxicity and how their impact can be managed.

Optimization of herbicide application: Studies on the timing and dosages of herbicide application are significant, particularly in the context of minimizing phytotoxicity risk and maximizing weed control effectiveness. This research can contribute to the development of improved herbicide application practices in potato cultivation.

Integrated farming approach: In the context of herbicide application optimization, it is valuable to promote an integrated approach that considers various factors, such as plant genetics, environmental conditions, herbicide type, and application timing. This approach can contribute to more sustainable potato cultivation.

As agriculture faces challenges related to environmental protection and increased production efficiency, research on herbicide phytotoxicity in potato cultivation remains a significant research area. Knowledge in this area can contribute to the development of more efficient and sustainable agricultural practices.

6. Conclusions

The use of herbicides, especially in POST applications, resulted in significant leaf damage to potatoes compared to PRE applications, especially when the herbicide Sencor 70 WG was applied POST applications at a dose of 0.5 kg ha-1.

Damage to dicotyledonous weeds remained relatively low and did not significantly differ between potato cultivars or weed control methods. Instead, atmospheric conditions during the study years had a more pronounced impact on weed damage than genetic factors or weed control methods.

The best results in terms of both overall and marketable potato yields were obtained by using the Sencor 70 WG herbicide PRE at the recommended dose. However, using this herbicide POST, even at a reduced dose, led to a reduction in the overall yield compared to the control and mechanical weed control.

The Apyros 75 WG herbicide containing sulfosulfuron as its active ingredient can be a valuable tool for controlling monocot weeds but may carry the risk of damaging potato plants, especially with specific cultivars. Further research on the herbicide's impact on different plant cultivars is valuable, and strategies should be developed for its effective use in agriculture while minimizing crop damage.

The impact of herbicides on potato yield turned out to be variable and depended on several factors, including potato variety, weed control method, and weather conditions. Therefore, it is essential for farmers to consider these factors in their agricultural practices and make informed decisions to optimize potato yield.

The higher level of herbicide damage in the 'Irga' cultivar indicates that the use of the Apyros 75 WG herbicide resulted in more extensive damage to this potato cultivar compared to the 'Fianna' cultivar. This suggests that the plant cultivar can influence its sensitivity to the herbicide's effects, and further research is needed to investigate the mechanisms behind this difference in sensitivity.

Weather conditions during the growing season had a substantial effect on both total and marketable potato yields. The highest yields were achieved in a year with optimal humidity and thermal conditions, whereas the lowest yields were observed during a dry year. This underscores the critical role of weather conditions in agriculture.

In potato cultivation, the priority should be given to optimizing factors such as crop management, disease and pest control, and environmental conditions, rather than relying solely on reducing phytotoxic damage to enhance yields. This knowledge can inform decision-making processes and resource allocation in potato farming to achieve greater efficiency and productivity.

In studies of herbicide phytotoxicity in the context of potato cultivation, significant aspects concerning plant responses to these substances and the impact of environmental conditions on phytotoxicity risk have been highlighted. Here is a summary and a challenge for the future: Phytotoxicity is a crucial factor in both agriculture and environmental conservation. Investigating its mechanisms and effects will enable the development of effective plant protection strategies and the maintenance of ecological equilibrium.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization: P.B. and B.S.; methodology: P.B., M.P., B.S.; software: D.S., P.P.; validation, P.B., M.P. and D.S.; formal analysis: P.B.; investigation: P.B.; resources: P.B., P.P.; data curation: P.B., D.S.; writing—original draft preparation: P.B., P.P.; writing—review and editing: P.B., B.S.; visualization: M.P., D.S.; supervision: B.S.; project administration: P.B., M.P.; funding acquisition: B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply. No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Institute of Plant Breeding and Acclimatization - National Research Institute, branch in Jadwisin for administrative and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”

List of abbreviations

PRE – pre-emergence

POST – post-emergence

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed 12.10.2023).

- Anonymous, 2023. Chapter 2. Food security and nutrition around the world [in:] The state of food security and nutrition in the world. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continue. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development, United Nations Children’s Fund World Food Programmer, World Health Organization, Rome, 2023. https://www.fao.org/3/cc3017en/cc3017en.pdf (accessed 10.10.2023).

- Devaux, A., Kromann, P. & Ortiz, O. Potatoes for Sustainable Global Food Security. Potato Research Journal of the European Potato Research Association, 2014, 1-13. ISSN 0014-3065, Potato Res. DOI: 10.1007/s11540-014-9265-1.

- Alebrahim, M.T., Majd, R., Rashed Mohassel, M.H., Wilcockson, S.; Baghestani, M.A.; Ghorbani, R.; Kudsk; P. Evaluating the efficacy of pre- and post-emergence herbicides for controlling Amaranthus retroflexus L. and Chenopodium album L. in potato. Crop Protection, 2012 42: 345-350.

- Hussain, Z., Munsif, F., Marwat, K.B., Ail, K., Afridi, R.A., Bibi S. Studies on efficacy of different herbicides against weeds in potato crop in Peshawar. Pak. J. Bot., 2013, 45(2): 487-491.

- Singh S.P.; Rawal, S.; Dua, V.K.; Sharma, S.K. Effectiveness of sulfosulfuron herbicide in controlling weeds in potato crops. Potato J., 2017, 44 (2): 110-116.

- Fonseca L.F., Luz J.M.Q., Duarte I.N., Wan D.B. Controle de plantas daninhas com herbicidas aplicados em pré-emergência na cultura da batata. [Weeds control with herbicides applied in pre-emergence in potato cultivation]. Biosci. J., Uberlândia, 2018, 34(2): 279-286.

- Herrera-Murillo, F., Picado-Arroyo, G. Evaluation of pre-emergent herbicides for weed control in sweet potato. Agronomía Costarricense, 2023, 47(1): 59-71.

- Wójtowicz A.; Mrówczyński M. (ed.) Metodyka integrowanej ochrony ziemniaka dla doradców. Opracowanie zbiorowe. Wyd. IOR-PIB, Poznań, 248 ss., 2017, ISBN: 978-83-64655-32-6 (in Polish).

- Biswas, U., Kundu, A., Labar, A., Datta, M.K., Kundu, C.K. Bioefficacy and phytotoxicity of 2, 4-D Dimethyl Amine 50% SL for weed control in potato and its effect on succeeding crop greengram. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci., 2017, 6(11): 1261-1267.

- Edwards, T.J.; Davies, S.L.; Yates, R.J., Rose, M.; Howieson, J.G.; O’Hara, G.; Steel, E.J.; Hall, D.J.M. The phytotoxicity of soil-applied herbicides is enhanced in the first-year post strategic deep tillage. Soil and Tillage Research, 2023, 231: 105734, ISSN 0167-1987. [CrossRef]

- Felipe, J.M., Martins, D., Da Costa, N.V. Seletividade de herbicidas aplicados em pré-emergência sobre cultivares de batata. Bragantia, Campinas, 2006, 5(4): 615-621.

- Gugała M., Zarzecka K. Skuteczność i selektywność herbicydów w regulacji zachwaszczenia na plantacji ziemniaka. Biuletyn IHAR, 2011, 262: 103-110. (in Polish).

- Mystkowska, I., Zarzecka, K., Baranowska, A., & Gugała, M. An effect of herbicides and their mixtures on potato yielding and efficacy in potato crop. Progress in Plant Protection/Postępy w Ochronie Roślin, 2017a, 57(1): 21-26.

- Abdallah, I.S., Atia, M.A., Nasrallah, A.K., El-Beltagi, H.S., Kabil, F.F., El-Mogy, M.M., & Abdeldaym, E.A. Effect of new pre-emergence herbicides on quality and yield of potato and its associated weeds. Sustainability, 2021, 13(17), 9796. [CrossRef]

- Dvořak, P.J., Remešowă, I. Assessment of metribuzin effects on potatoes using a method of very rapid fluorescence induction. Rast. Výr. 2002, 48 (3): 107-117.

- Hutchinson, P. J., Boydston, R. A., Ransom, C. V., Tonks, D. J., & Beutler, B. R. Potato variety tolerance to flumioxazin and sulfentrazone. Weed Tech., 2005, 19(3): 683-696.

- Brooke, M. J., Stenger, J., Svyantek, A. W., Auwarter, C., Hatterman-Valenti, H. ‘Atlantic’ and ‘Dakota Pearl’ chipping potato responses to glyphosate and dicamba simulated drift. Weed Technol. 2022, 36: 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz J. Reakcja odmian ziemniaka o zróżnicowanej budowie liści na metrybuzynę stosowaną po wschodach. Część I. Zwalczanie chwastów w ziemniaku. Biuletyn Instytutu Hodowli i Aklimatyzacji Roślin, 2012, 265: 15-28. (in Polish).

- Dias, R.C., Barbosa, A.R., Silva, G.S., De Lourdes Pereira Assis, A.C., Melo, C.A.D., Silva, D.V., Reis, M.R. Efeito de herbicidas no crescimento, produtividade e qualidade de tubérculos de batata. Magistra, Cruz das Almas – BA, 2017, 29(1): 71-79.

- Ginter, A., Zarzecka, K., Gugała, M., & Mystkowska, I. Wpływ sposobu ochrony plantacji przed chwastami na wyniki produkcyjne i ekonomiczne trzech odmian ziemniaka jadalnego. Progress in Plant Protection /Postępy w Ochronie Roślin, 2023, 63(1): 41–47.

- Barbaś, P. Zmiany w morfologii Chenopodium album w warunkach stosowania metrybuzyny i mieszanki metrobuzyny z sulfosulfuronem, rimsulfuronem i flauazyforem w uprawie ziemniaka. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska. Sectio E. Agricultura, 2008, 63(1): 71-80. (in Polish).

- Reader A.J., Lyon D., Harsh J., Burke I. How soil pH affects the activity and persistence of herbicides. Washington State University, 2015, https://research.libraries.wsu.edu:8443/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2376/6097/FS189E.pdf.

- Ramsey, R.J.L., Stephenson, G.R., Hall, J.C.A review of the effects of humidity, humectants, and surfactant composition on the absorption and efficacy of highly water-soluble herbicides. Pesticide Biochemistry & Physiology, 2005, 82(2): 162-175.

- Gugała, M., Zarzecka, K., & Sikorska, A. Ocena skuteczności działania herbicydów i ich wpływ na plon handlowy ziemniaka. Biuletyn IHAR, 2013, 270: 75-84. (in Polish).

- Mystkowska, I., Zarzecka, K., Baranowska, A., & Gugała, M. Zachwaszczenie łanu i plonowanie ziemniaka w zależności od sposobu pielęgnacji i warunków pogodowych. Acta Agrophysica, 2017b, 24(1): 111-121. (in Polish).

- Urbanowicz J. Reakcja nowych odmian ziemniaka na powschodowe stosowanie metrybuzyny. Progres in Plant Protection / Post. w Ochr. Roślin, 2006, 46(2): 305-308. (in Polish).

- Boydston, R.A. Potato and Weed Response to Postemergence - Applied Chlorsulfuron, Rimsulfuron, and EPTC. Weed Technology, 2007, 21: 465-469.

- Luz J.M.Q., Fonseca L.F., Duarte I.N. Selectivity of pre-emergence herbicides in potato cv. Innovator. Horticultura Brasileira, 2018, 36: 223-228.

- Hatterman-Valenti, H., Endres, G., Jenks, B., Ostlie, M., Reinhardt, T., Robinson, A., Stenger, J., Zollinger, R. Defining glyphosate and dicamba drift injury to dry edible pea, dry edible bean, and potato. Hort. Technology, 2017, 27(4): 502-509.

- Hoza, G., Enescu, B. G., & Becherescu, A. Research regarding the effect of applying herbicides to combat weeds in quickly-potato cultures. Scientific Papers-Series B, Horticulture, 2015, (59): 219-223.

- Ma, H., Lu, H., Han, H., Yub, Q., & Powlesb, S. Metribuzin resistance via enhanced metabolism in a multiple herbicide resistant. Pest Manag. Sci., 2020, DOI 10.1002/ps.5929.

- Zalecenia ochrony roślin na lata 2018/2019. Instytut Ochrony Roślin – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Części I–IV. Opracowanie zbiorowe, Wydawnictwo: IOR-PIB, Poznań, ISSN: 1732-1816 (in Polish).

- Korbas M. (ed.). Potato protection program. 2017. https://www.ior.poznan.pl/plik,2913program-ochrony-ziemniaka-pdf. (accessed 23.09.2023) (in Polish).

- Nowacki W. (ed.). Characteristics of the National Register of Potato Cultivars, 22th Edition, 2019. IHAR—PIB, Branch Jadwisin, ss. 45. (in Polish).

- PubChem Compound Summary for CID 70551071, CID 70551071. 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/70551071. (Accessed 12.10.2023).

- CAS Databases 2023, https://www.cas.org/support/documentation/cas-databases (accessed 08.10.2023).

- EPA 2023. Fluazifop-P-butyl; Pesticide tolerances. Resolution of the Environmental Protection Agency of April 27, 2023. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/04/27/2023-08939/fluazifop-p-butyl-pesticide-tolerances.

- Badowski, M., Domaradzki, K., Filipiak, K., Franek, M., Gołębiewska, H., Kieloch, R., Kucharski, M., Rola H., Rola, J., Sadowski, J., Sekutowski, T., Zawerbny, T. Metodyka doświadczeń biologicznej oceny herbicydów, bioregulatorów i adiuwantów. Cz. I. Doświadczenia polowe. Wyd. IUNG Puławy, 2001, 167 ss. (in Polish).

- Pszczółkowski, P., Sawicka, B., Skiba, D., Barbaś, P., Noaema, A.H. The Use of Chlorophyll Fluorescence as an Indicator of Predicting Potato Yield, Its Dry Matter and Starch in the Conditions of Using Microbiological Preparations. Applied Sciences, 2023; 13(19):10764. [CrossRef]

- PN-R-0403:1997. Chemical and agricultural analysis of soil. Sampling. Polish Committee for Standardization, Warszawa. (in Polish).

- Mocek A. Gleboznawstwo. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. ISBN-13, 978-83-01-18795-8. Wydanie 1, 2015, 589 ss.

- Ryżak, M., Bartmiński, P.; Bieganowski, A. Methods for determination of particle size distribution of mineral soils. Acta Agroph. Theses and Monographs, 2009, 175(4): 1-97. ISSN: 1234-4125.

- Lützenkirchen J., Preočanin T., Kovačević D., Tomišić V, Lövgren L., Kallay N. Potentiometric titrations as a tool for surface charge determination. Croat. Chem. Acta, 2012, 85(4): 391-417.

- PN-R-04020:1994+AZ 1:2004. Chemical and agricultural analysis of soil. Polish Committee for Standarization, Warszawa. (in Polish).

- PN-R-04023:1996. Chemical and agricultural analysis of soil. Determination of available phosphorus content in mineral soils. Polish Committee for Standarization, Warszawa. (in Polish).

- PN-R-04022:1996+AZ 1:2002. Chemical and agricultural analysis of soil. Determination of available potassium content in mineral soils. Polish Committee for Standardization, Warszawa. (in Polish).

- World Reference Database for Soil Resources. WRB. 2014, http://www.fao.org/3/ai3794e.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Nawrocki S. Fertilizer recommendations. Part. I. Limit numbers for valuation of soils in macro- and microelements. Ed. by IUNG Puławy, 1990, P (44). (in Polish).

- Skowera B., Kopcińska J., Kopeć B. Changes in thermal and precipitation conditions in Poland in 1971-2010. Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Land Reclamation, 2014, 46(2): 153-162.

- SAS I. I. 2008. SAS/STAT®9.2. User’s Guide.

- Koronacki, J.; Mielniczuk, J. Statystyka dla studentów kierunków technicznych i przyrodniczych. WNT, Warszawa, 2006, Wyd. 3, ss. 456. (in Polish).

- IBM. SPSS Statistics 28 User’s Guide—IBM Core System. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_28.0.0.

- Sawicka, B. The response of 44 cultivars of potato to metribuzin. Rocz. Nauk Rol., seria E – Ochrona Roślin, 1994, 23(1/2): 103-123. (in Polish).

- Hermeziu, M., Nitu, S., Hermeziu, R. Studies of efficacy of different herbicides against weeds in potato crop in central part of Romania. Annals of the University of Craiova, 2020, XXV(LXI), 388–393.

- Urbanowicz J. Skuteczność zwalczania chwastów w ziemniaku za pomocą wybranych herbicydów przedwschodowych. Ziemniak Polski, 2021, 1, 24-33. (in Polish).

- Praczyk T., Skrzypczak G. (ed.). Właściwości i zastosowanie herbicydów. [w:] Herbicydy. Wydawnictwo: PWRiL, Poznań, 2004, ISBN: 83-09-01786-3: 17-66. (in Polish).

- Tkach, A.S., & Golubev, A.S. Sensitivity of potato cultivars to formesafen and metribuzin. Potato Journal, 2022, 49(1): 17-26.

- Urbanowicz J. Wpływ powschodowego stosowania metrybuzyny na plon wybranych odmian ziemniaka. Progress in Plant Protection / Post. w Ochr. Roślin, 2010, 50(2): 837-841. (in Polish).

- Sawicka, B.; Skalski; J. Zachwaszczenie ziemniaka w warunkach stosowania herbicydu Sencor 70 WP. Cz. II. Skuteczność chwastobójcza herbicydu. Rocz. Nauk Rol., 1996, A-112, 1-2: 169-182 (in Polish).

- Riethmuller-Haage, I., Bastiaans, L., Kempenaar, C., Smutny, V., Kropff, M.J. Are pre-spraying growing conditions a major determinant of herbicide efficacy? Weed Research, 2007, 47(5): 415-424.

- Lichenthaler H.K. Vegetation stress an introduction to the stress concept in plants. J. Plant Physiol., 1996,148: 4–11.

- Starck, Z. Wpływ warunków stresowych na koordynację wytwarzania i dystrybucję fotoasymilatów. Post. Nauk Roln. 2010, 1: 9-26. (in Polish).

- Sawicka; B.; Michałek, W.; Pszczółkowski, P. Dependence of chemical composition of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers on physiological indicators. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture, 2015, 102(1): 41-50. ISSN 1392-3196 / e-ISSN 2335-8947, DOI 10.13080/z-a.2015.102.005.

- Skórska, E.; Swarcewicz, M. Zastosowanie fluorescencji chlorofilu do oceny skuteczności działania wybranych adiuwantów w mieszaninie z atrazyną. Inżynieria Roln. 2005, 64: 253–259. (in Polish).