Submitted:

10 October 2023

Posted:

12 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

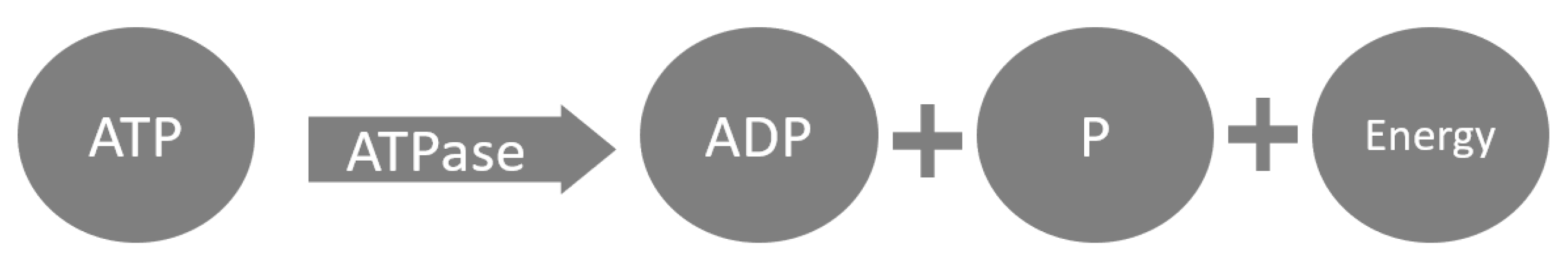

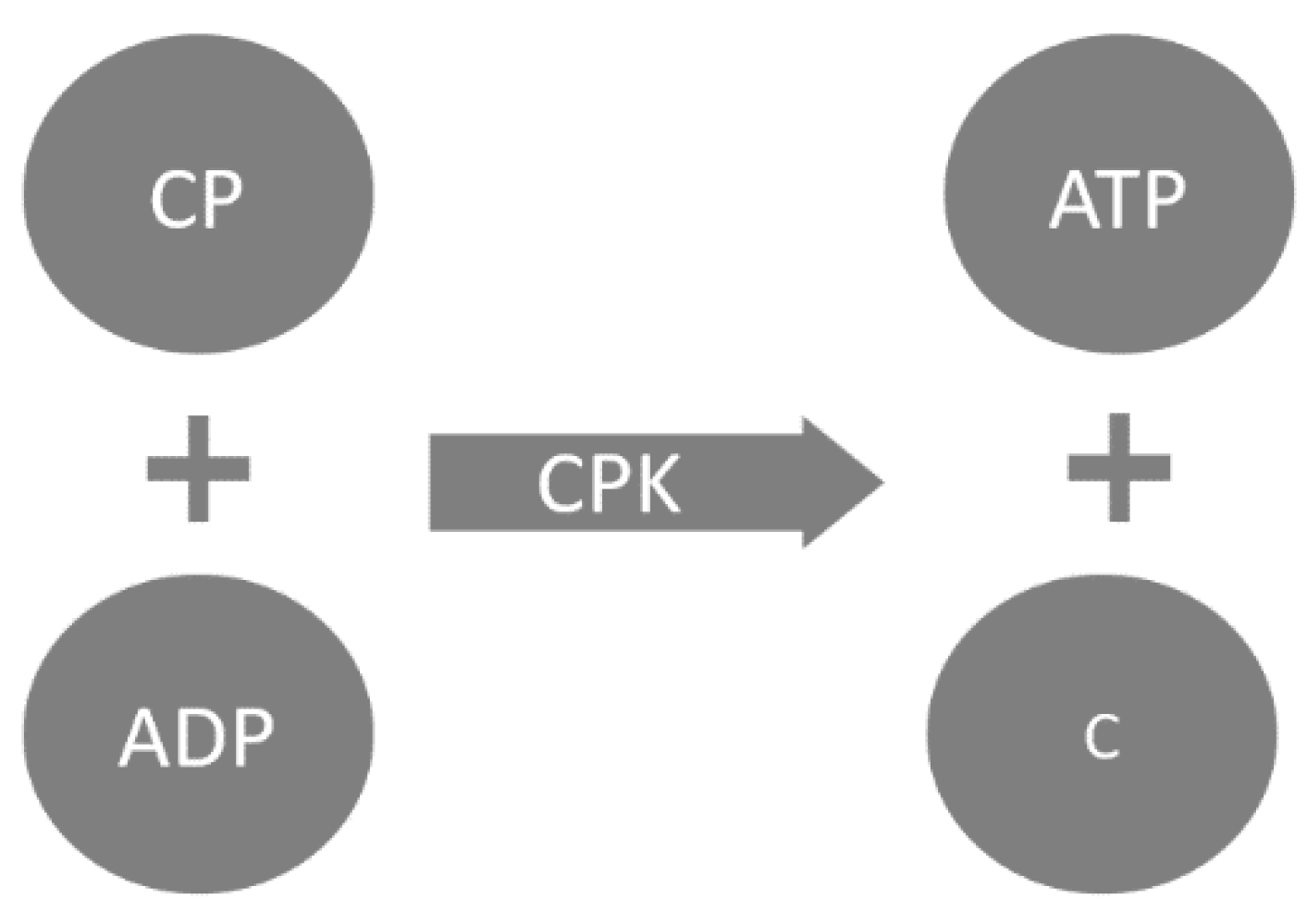

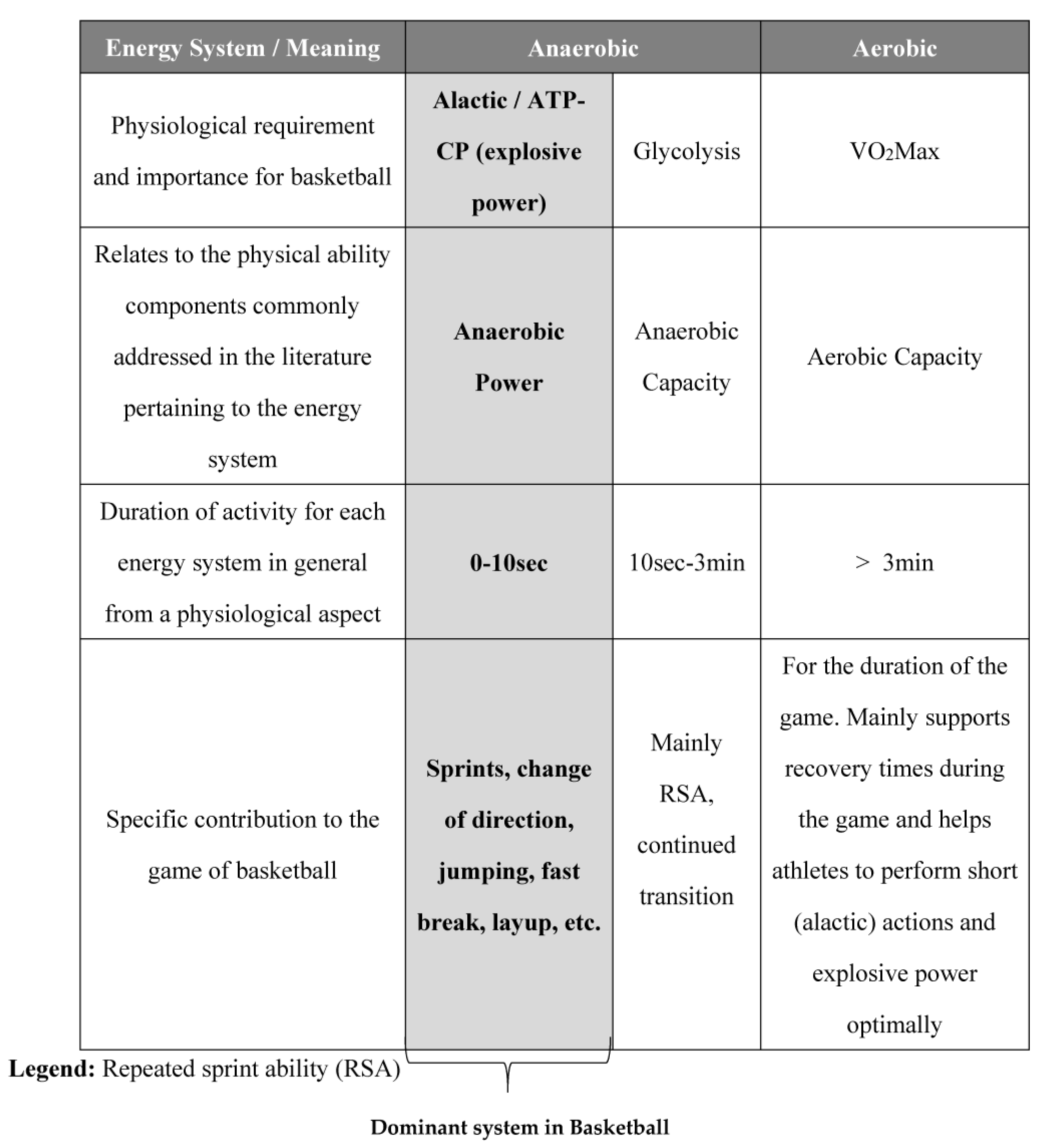

1.1. The physiological anaerobic alactic system that is dominant in basketball

1.2. Explosive power and anaerobic alactic demands in basketball

1.3. Specific movements in basketball

2. Explosive capability assessments

2.1. 5/10-meter sprint speed test

2.2. Standing broad jump test

2.3. Drop jump test

2.4. 2x5-meter change of direction ability test

2.5. Countermovement jump test

2.6. Squat jump test

2.7. Bounding power test

2.8. Spike jump test

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions and Practical Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gottlieb, R.; Eliakim, A.; Shalom, A.; Iacono, A.; Meckel, Y. Improving Anaerobic Fitness in Young Basketball Players: Plyometric vs. Specific Sprint Training. Journal of Athletic Enhancementer. 2014, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, R.; Shalom, A.; Calleja-Gonzalez, J. Physiology of Basketball – Field Tests. Review Article. J Hum Kinet. 2021, 77, 159–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, N.; El Fazaa, S.; El Ati, J.; Tabka, Z. Time-motion analysis and physiological data of elite under-19-year-old basketball players during competition * Commentary. Br J Sports Med. 2007, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanović, E.; Stojiljković, N.; Scanlan, A.T.; Dalbo, V.J.; Berkelmans, D.M.; Milanović, Z. The Activity Demands and Physiological Responses Encountered During Basketball Match-Play: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine. 2018, 48, 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delextrat, A.; Cohen, D. Physiological Testing of Basketball Players: Toward a Standard Evaluation of Anaerobic Fitness. J Strength Cond Res. 2008, 22, 1066–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.J. Physiological considerations and suggestions for the training of elite basketball players. In Toward an Understanding of Human Performance; Movement: Ithaca, NY, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, E.L.; Mathews, D.K. The Physiological Basis of Physical Education and Athletics; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aksović, N.; Bjelica, B.; Milanović, F.; Milanovic, L.; Jovanović, N. Development of Explosive Power in Basketball Players. Turkish Journal of Kinesiology. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mancha-Triguero, D.; García-Rubio, J.; Antúnez, A.; Ibáñez, S.J. Physical and Physiological Profiles of Aerobic and Anaerobic Capacities in Young Basketball Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovic, M.D.; Ostojic, S.M.; Calleja-González, J.; Milosevic, Z.; Mikic, M. Correlation between explosive strength, aerobic power and repeated sprint ability in elite basketball players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2012, 52, 375–81. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, T.; Spiteri, T.; Piggott, B.; Bonhotal, J.; Haff, G.G.; Joyce, C. Monitoring and Managing Fatigue in Basketball. Sports (Basel) 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, N.; Nassis, G.P.; Bolatoglou, T.; Geladas, N.D. Physiological and technical characteristics of elite young basketball players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2004, 44, 157–63. [Google Scholar]

- Alemdaroğlu, U. The Relationship Between Muscle Strength, Anaerobic Performance, Agility, Sprint Ability and Vertical Jump Performance in Professional Basketball Players. J Hum Kinet. 2012, 31, 149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balčiūnas, M.; Stonkus, S.; Abrantes, C.; Sampaio, J. Long term effects of different training modalities on power, speed, skill and anaerobic capacity in young male basketball players. J Sports Sci Med. 2006, 5, 163–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McInnes, S.E.; Carlson, J.S.; Jones, C.J.; McKenna, M.J. The physiological load imposed on basketball players during competition. J Sports Sci. 1995, 13, 387–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.M.; Young, W.B. Agility literature review: Classifications, training and testing. J Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 919–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalfawi, S.A.I.; Sabbah, A.; Kailani, G.; Tønnessen, E.; Enoksen, E. The relationship between running speed and measures of vertical jump in professional basketball players: a field-test approach. J Strength Cond Res. 2011, 25, 3088–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancha-Triguero, D.; García-Rubio, J.; Calleja-González, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Physical fitness in basketball players: a systematic review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, E.; Bowers, R.; Foss, M. The Physiological Basis of Physical Education and Athletics; WB Saunders: Philadelphiam, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gillam, G.M. Basketball energetics: physiological basis. Nat Strength Cond Assoc. J 6 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, D.G. Predicting success in junior elite basketball players--the contribution of anthropometic and physiological attributes. J Sci Med Sport. 2000, 3, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, S.M.; Mazic, S.; Dikic, N. Profiling in Basketball: Physical and Physiological Characteristics of Elite Players. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2006, 20, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wragg, C.B.; Maxwell, N.S.; Doust, J.H. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of a soccer-specific field test of repeated sprint ability. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000, 83, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, G.; Dizdar, D.; Jukic, I.; Cardinale, M. Reliability and Factorial Validity of Squat and Countermovement Jump Tests. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2004, 18, 551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- García-López, J.; Peleteiro, J.; Rodgríguez-Marroyo, J.A.; Morante, J.C.; Herrero, J.A.; Villa, J.G. The Validation of a New Method that Measures Contact and Flight Times During Vertical Jump. Int J Sports Med. 2005, 26, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, C.; Luhtanen, P.; Komi, P.V. A simple method for measurement of mechanical power in jumping. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1983, 50, 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghe, T.; Scanlan, A.; Dalbo, V.; Calleja-González, J. The Negative Influence of Air Travel on Health and Performance in the National Basketball Association: A Narrative Review. Sports. 2018, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferioli, D.; Rampinini, E.; Martin, M.; Rucco, D.; la Torre, A.; Petway, A.; et al. Influence of ball possession and playing position on the physical demands encountered during professional basketball games. Biol Sport. 2020, 37, 269–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meckel, Y.; Machnai, O.; Eliakim, A. Relationship Among Repeated Sprint Tests, Aerobic Fitness, and Anaerobic Fitness in Elite Adolescent Soccer Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2009, 23, 163–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujika, I.; Santisteban, J.; Castagna, C. In-season effect of short-term sprint and power training programs on elite junior soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2009, 23, 2581–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, L.L.; Merom, D.; Thomas, M.; Peralta, L. 30-year changes in Australian children’s standing broad jump: 1985–2015. J Sci Med Sport. 2018, 21, 1057–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glencross, D.J. The nature of the vertical jump test and the standing broad jump. Res Q. 1966, 37, 353–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedley, J.S.; Lloyd, R.S.; Read, P.; Moore, I.S.; Oliver, J.L. Drop Jump: A Technical Model for Scientific Application. Strength Cond J. 2017, 39, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffaye, G.; Bardy, B.; Taiar, R. Upper-limb motion and drop jump: effect of expertise. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2006, 46, 238–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baca, A. A comparison of methods for analyzing drop jump performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 437–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, T.T.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Bishop, C.; Calleja-González, J.; Arruda, A.F.S.; Guerriero, A.; et al. Change of Direction Deficit in National Team Rugby Union Players: Is There an Influence of Playing Position? Sports (Basel) 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.B.; McDowell, M.H.; Scarlett, B.J. Specificity of sprint and agility training methods. J Strength Cond Res. 2001, 15, 315–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sayers, M. Does the 5-0-5 test measure change of direction speed? J Sci Med Sport. 2014, 18, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovi, J.D.; Mcguigan, M.R. Relationships between sprinting, agility, and jump ability in female athletes. J Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlan, A.T.; Madueno, M.C.; Guy, J.H.; Giamarelos, K.; Spiteri, T.; Dalbo, V.J. Measuring Decrement in Change-of-Direction Speed Across Repeated Sprints in Basketball: Novel vs. Traditional Approaches. J Strength Cond Res. 2021, 35, 841–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.A. Jumping into plyometrics; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL., 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, J.M.; Cronin, J.B.; Gabbett, T.J.; McGuigan, M.R.; Etxebarria, N.; Newton, R.U. Relative importance of strength, power, and anthropometric measures to jump performance of elite volleyball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2008, 22, 758–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehar, M.; Sekulic, D.; Sisic, N.; Spasic, M.; Uljevic, O.; Krolo, A.; et al. Evaluation of different jumping tests in defining position-specific and performance-level differences in high level basketball players. Biol Sport. 2017, 3, 263–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.; Bishop, D.; Dawson, B.; Goodman, C. Physiological and metabolic responses of repeated-sprint activities:specific to field-based team sports. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 1025–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.K.; Oikawa, S.Y.; Halson, S.; Stephens, J.; O’Riordan, S.; Luhrs, K.; et al. In-Season Nutrition Strategies and Recovery Modalities to Enhance Recovery for Basketball Players: A Narrative Review. Sports Medicine. 2022, 52, 971–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcher, C.; Buchheit, M. Shooting Performance and Fly Time in Highly Trained Wing Handball Players: Not Everything Is as It Seems. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017, 12, 322–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalom, A.; Gottlieb, R.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Calleja-Gonzalez, J. A Unique Specific Jumping Test for Measuring Explosive Power in Basketball Players: Validity and Reliability. Applied Sciences. 2023, 13, 7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioli, D.; Rampinini, E.; Bosio, A.; La Torre, A.; Azzolini, M.; Coutts, A.J. The physical profile of adult male basketball players: Differences between competitive levels and playing positions. J Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 2567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, P.A.; Vardaxis, V.G. Lower-Extremity Strength Profiles and Gender-Based Classification of Basketball Players Ages 9-22 Years. J Strength Cond Res. 2009, 23, 406–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorio, A.; Agosti, F.; De Col, A.; Lafortuna, C.L. Age-and gender-related variations of leg power output and body composition in severely obese children and adolescents. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006, 29, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.; Shalom, A.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Calleja-González, J. Validity and reliability of a unique aerobic field test for estimating VO2max among basketball players. Scientific Journal of Sport and Performance. 2022, 1, 112–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, N.; Newton, R.U.; Andrews, W.A.; Kawamori, N.; McGuigan, M.R.; Nosaka, K. Does performance of hang power clean differentiate performance of jumping, sprinting, and changing of direction? J Strength Cond Res. 2008, 22, 412–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meylan, C.; McMaster, T.; Cronin, J.; Mohammad, N.I.; Rogers, C.; deKlerk, M. Single-Leg Lateral, Horizontal, and Vertical Jump Assessment: Reliability, Interrelationships, and Ability to Predict Sprint and Change-of-Direction Performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2009, 23, 1140–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, T.T.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.; Calleja-González, J.; Alcaraz, P.E. Short-term adaptations following Complex Training in team-sports: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0180223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFiori, J.P.; Güllich, A.; Brenner, J.S.; Côté, J.; Hainline, B.; Ryan, E.; et al. The NBA and Youth Basketball: Recommendations for Promoting a Healthy and Positive Experience. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2053–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Garcia-Hermoso, A.; Moran, J.; Chaabene, H.; Negra, Y.; Scanlan, A.T. The effects of plyometric jump training on physical fitness attributes in basketball players: A meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Gil, M.; Torres-Unda, J.; Esain, I.; Duñabeitia, I.; Gil, S.M.; Gil, J.; et al. Anthropometric Parameters, Age, and Agility as Performance Predictors in Elite Female Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2018, 32, 1723–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Horizontal | Vertical | Combined |

|---|---|---|

| 5/10-meter sprint (speed test) | Countermovement jump | Bounding power |

| Standing broad jump | Squat jump | Spike jump |

| Horizontal drop jump | Vertical drop jump | |

| 2 x 5-meter change of direction ability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).