1. Introduction

Increasing efficiency of an energy conversion system is of great importance in our society as we tackle the on-going climate crisis and aim to reduce the use of fossil fuel resources [

1]. About 72 % of the global energy consumption is wasted after the conversion processes [

2]. Moreover, the recent U.S. energy chart shows that about 60% of the energy generated is rejected to the environment mostly as waste heat [

3]. From this perspective, waste heat recovery (WHR) is one of the promising approaches that can increase the efficiency of energy conversion processes and reduce the use of fossil fuels. Waste heat recovery systems can be categorized into three groups: Heat-to-Heat, Heat-to-Work, and Heat-to-Power [

4]. This study investigates the utilization of the Heat-to-Power WHR approach using solid-state thermoelectric generators (TEGs) in a gas turbine power plant as a case study.

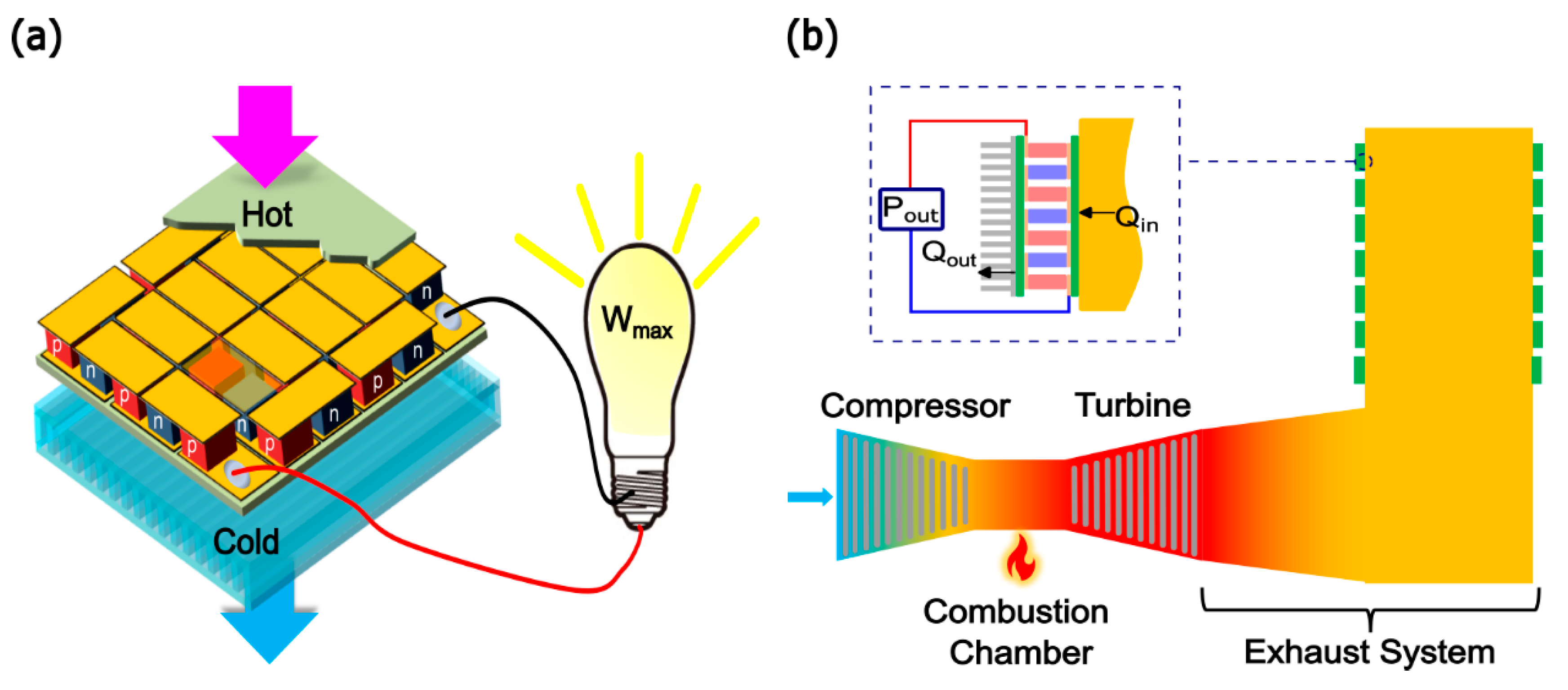

Gas turbine cycles are one of the most popular energy conversion cycles that convert the chemical energy of a fuel to mechanical energy to rotate turbine blades, which in turn generates electricity. As schematically shown in

Figure 1, a typical gas turbine power plant comprises four main components: a compressor to pressurize the input gas, a combustion chamber to add energy to the compressed gas, a prime mover (turbine) to extract the energy from the hot gas, and an exhaust system to capture the toxic combustion products before releasing the flue gases to the atmosphere [

5]. Despite its relatively high energy efficiency, a gas turbine wastes a vast amount of energy by releasing high temperature gases into the environment. The typical temperature of the exhaust gases from a simple gas turbine cycle is in the range of 400 – 500 °C [

6].

There are two known approaches to recover waste heat from a gas turbine: regeneration and cogeneration. A regenerator (or recuperator) is a heat exchanger used to preheat the compressed gas with the exhaust gas before it enters the combustion chamber, thereby decreasing the heat input requirement by recycling waste heat from the exhaust [

5]. However, in high pressure-ratio compressors, the temperature of the compressed gases can be already higher than the temperature of the exhaust gases, so a regenerator is unviable in such a case as it will decrease the compressed gas temperature. Also, the pressure drop across the regenerator can adversely increase the power consumption of the cycle and thus reduce the overall efficiency. Hence, regenerative gas turbines are relatively scarce [

7]. On the other hand, cogeneration is the process of producing multiple useful forms of energy from a single energy source [

8]. For gas turbines, the released gases can be used to generate superheated vapor for a subsequent Rankine cycle in combined cycles or can be exploited in various processes where heat is the main input such as in chemical, paper, or food processing industry, also in air conditioning, desalination, etc. [

9]. However, high capital cost and special installation requirements associated with these cogeneration systems could hinder their utilization. Furthermore, gas turbines are often desired to operate on part load, which reduces the amount of released heat and makes it less attractive for use in many of the aforementioned systems.

Over the past decades, thermoelectric energy conversion has attracted great attention as a heat recovery technology because of its capability to directly convert waste heat to electrical power based on the Seebeck effect without moving parts and fluids involved [

10]. A thermoelectric generator (TEG) is a solid-state device comprised of multiple n-type and p-type semiconductor elements or TE legs that are connected electrically in series and thermally in parallel as shown in

Figure 1(a). When heat flows through the module, a voltage is induced in each of the TE legs by the Seebeck effect, which delivers power to the load. TE system offers small form factors, no moving parts, robust operation, and minimal impacts to the application system, e.g. gas turbine.

Maximum power output or efficiency is achieved when the module design parameters such as fill factor (fractional area coverage by TE legs) and leg thickness are optimized for simultaneous electrical and thermal load matching against the external electrical and thermal resistances[

11]. Hence, custom design optimization of TE system is necessary for a specific application system as the conditions of external resistances vary depending on the application. The efficiency of a thermoelectric material is largely determined by the dimensionless figure-of-merit

ZT defined as

where

S is the Seebeck coefficient or thermopower,

is the electrical conductivity,

is the thermal conductivity, and

T is the absolute temperature [

12]. Equation (1) reveals that a good thermoelectric material is characterized by high power factor (

, and low thermal conductivity. Researchers have shown that this could be attained by nanostructuring [

13]. Nanostructuring of thermoelectric materials is a promising technique that can suppress the phonon transport to reduce thermal conductivity, while maintaining the electron transport or the power factor high to improve the

ZT. For example, nanostructured Bi

2Te

3 alloys enhanced the

ZT values of the n-type and the p-type to ~1.4 and ~1.0, respectively[

14,

15]. Moreover, the rhombohedral complex molecular structures of GeTe and SnSe have made them excellent thermoelectric materials with

ZT above 2.0 in the mid-temperature range [

16,

17]. There are several review papers that describe the recent advancement of thermoelectric materials [

13,

18,

19].

Recently, there has been a great deal of research on TE waste heat recovery systems. Kuroki et al. [

20] demonstrated the feasibility of using TEGs to recover waste heat generated from a steel making process. The system consisted of 16 TEG modules of 5 × 5 cm

2 mounted above the radiating slab; each module produced 18 W under the temperature difference of 220 K. The maximum power density of 1.32 kW/m

2 was achieved in this study when the hot side temperature was 1188 K. Referring to this study, Ghosh et al. [

21] provided a detailed theoretical investigation to further optimize the module performance. Yazawa et al. [

22] exploited the large temperature difference between the burner flame and the pressurized steam in a steam turbine cycle to produce additional electrical power and enhance the overall efficiency using TEGs as a topping cycle. They carried out an optimization study on the interface temperature between the TEG and the steam pipes for better energy economy. A follow up study was caried out by the same team [

23] to investigate the efficiency enhancement of advanced supercritical steam turbines as a result of adding the TE topping generators. Hasani et al. [

24] experimentally investigated a proton-exchange-membrane (PEM) fuel cell thermoelectric heat recovery system. They reported that when TEGs were integrated with a 5 kW PEM fuel cell to recover waste heat, they could produce up to 800 W more electric power with TE modules. However, the TE efficiency was only around 0.35 % at hot water temperature of 68 °C due to the relatively small temperature difference applied. There have been several studies on TE waste recovery in cement manufacturing processes [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] as well. In this process, a vast amount of heat is wasted from the shell of the rotating kiln. Mirhosseini et al. [

29] investigated the use of TEGs for waste heat recovery in cement kilns with three different types of heat sinks and optimized TEGs for highest power output and lowest investment cost. The results revealed that the best cost per power ratio is attained with the staggered configured heat sink; however, different fill factors should be used at different sections of the kiln. There have been many other studies that explore the feasibility of the TE technology as a heat recovery system [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

For waste heat recovery in gas turbines, Yongjia et al. [

35] investigated a small TEG heat recovery unit on a gas turbine to power a sensor node. An experimental prototype, consisting of a TEG module and two heat pipes to dissipate heat from the cold side, was developed to characterize the performance and validate the mathematical model. At 325

heat source temperature, the system provided 0.92 W power output with a peak open circuit voltage of 2.4 V, which was enough to power few sensors and their auxiliary electronics. Bardy et al. [

36] provided a mathematical model to predict the maximum efficiency of a TEG system integrated with a gas turbine system in two configurations: topping cycle configuration and preheating topping cycle configuration. In the former, TEG modules were placed on top of the gas turbine cycle between the heat source and the combustion chamber; whereas, in the later configuration, TEG modules received heat from the heat source to generate electricity and reject the remaining energy directly to the working fluid before it enters the combustion chamber. It was concluded that the topping configuration can improve the efficiency of the combined cycle and it was efficient for both low- and high-temperature Brayton cycles.

In this study, we investigate the “bottom cycle configuration,” where a thermoelectric waste heat recovery system (TEWHR) is mounted at the outer surface of the exhaust ducts in a gas turbine power plant. We develop a numerical algorithm to optimize the TEWHR performance along with the calculation of exergy factors such as exergy efficiency, waste exergy ratio, and recoverable exergy. This numerical tool can solve the coupled heat and electric current equations with convective heat transfer at both sides, and account for the temperature reliance of the thermoelectric properties. Finally, considering that the thermal resistance of the cold side is one of the prominent factors that influence the performance of the system, the effect of the cold side convection heat transfer coefficient on the matched-load power output is investigated as well.

2. Methodology and Computational Models

Figure 1(b) shows a schematic of the gas turbine power plant with TEGs mounted at the exhaust duct of the turbine that we investigate. The compressor pressurizes the working fluid (air in this case) and then routes it to the combustion chamber, where heat energy is added to raise its temperature up to the design temperature limit of the turbine. After that, the pressurized hot gases expand in the prime mover and mechanical energy is produced. In this study, the General Electric LM6000 PC simple gas turbine of 42 % thermal efficiency and 46 MW rated power output is used for investigation. This gas turbine is widely used in power plants and marine application to generate electricity and heat [

37]. The flue gases leave the turbine at 500 °C, which falls within the range of high-quality heat, at a mass flow rate of 130 kg/s. The cross-sectional area and the length of the exhaust duct investigated are assumed to be 0.5 × 0.5 m

2 and 2 m, respectively.

TEG modules are installed at the outer surface of the exhaust duct as shown in

Figure 1(b). Due to the temperature difference between the hot gases inside the duct and the surrounding air outside, heat flows through the attached TEGs by conduction and voltage is generated by the Seebeck effect. When a load resistance is connected to the module, an electric current flows to the load by the generated voltage and thus electric power is delivered to the load. A detailed numerical algorithm has been developed in this study to investigate the power generation performance and to optimize the design of this thermoelectric waste heat recover system.

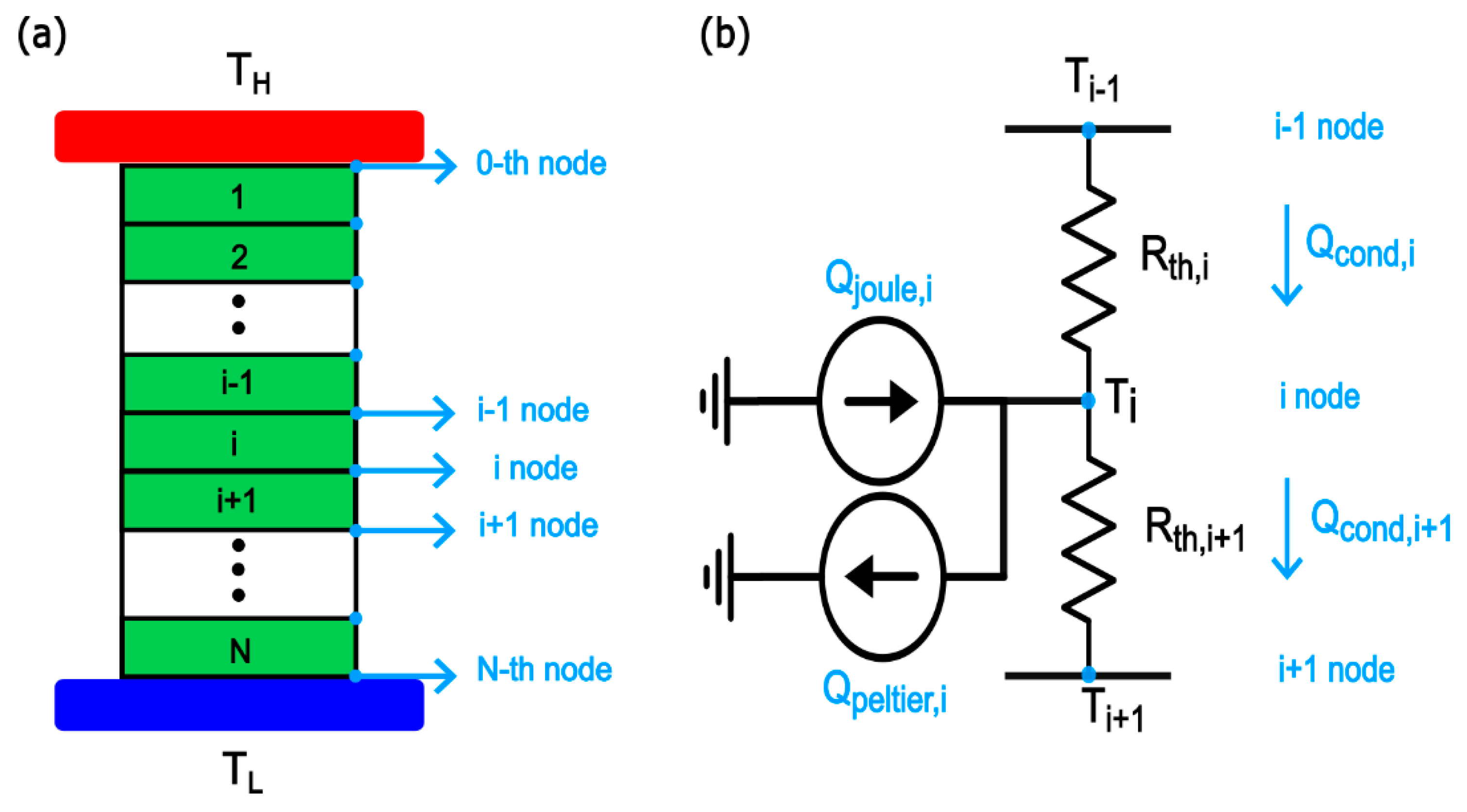

Our computational model incorporates the TE phenomena and the convective heat transfer phenomenon at both interfaces with flue gases and surrounding ambient air. For the TE phenomena (Seebeck, Peltier, Joule, and Thomson effects), the coupled thermal and electrical current equations are solved simultaneously in each TE element to find the temperature profile along its thickness, the rate of heat transfer through it, and the power output. A finite element method is used to divide the TE leg into smaller segments in order to obtain accurate temperature profile and to account for the change of material properties along the element thickness with temperature as shown in

Figure 2(a). Each segment has its own TE properties which correspond to the average temperature of the segment

. The expressions that describe the change of material properties with temperature have been curve fitted and integrated in the proposed algorithm. The three TE equations, conduction heat in eq.(2), Joule heat in eq.(3), and Peltier heat in eq.(4), are solved together in an iterative manner. The process starts with a linear temperature distribution inside the TE leg as an initial guess, assuming that the conduction heat dominates over Joule and Peltier heats. Before each iteration, the TE material properties are updated based on the temperature profile of the previous iteration. Hence, the fixed-point iteration method has been used.

where

is the electric current,

is the thermal conductance, and

is the electrical resistance of the i-th segment with thickness of

.

Figure 2 (b) depicts the equivalent thermal circuit model of one segment. Applying the first law of thermodynamics at the i-th node gives eq.(5)

where i spans from 1 to N-1. The first and the last segments of the TE element are in contact with the copper plates that convey the electric current between legs. Therefore, the first segment of the TE element has one component of Peltier heat and one component of Joule heat at the bottom interface, eq.(6) and eq.(7), while the last the TE element has one component of Peltier heat and one component of Joule heat at the top interface, eq.(8) and eq.(9).

where

are influenced by the external thermal resistances.

Every TE generator has multiple pairs n-type and p-type legs element connected electrically in series and thermally in parallel. The ratio of the area covered by these TE pairs to the total area of the substrate is called the fill factor, which is expressed as

where

is the number of TE pairs,

is the cross-sectional area of the n-type element and

is the cross-sectional area of the p-type element. This factor along with the hot side heat transfer coefficient

control the rate of heat flow into the first segment of the TE elements. Thus, the rate of heat input into the 0-th node is:

where the first term of this equation

represent the fractional area of the hot plate that provides the input heat for each TE leg. On the other end of the TE leg, the cold side heat transfer coefficient

controls the heat output from the last segment of the TE element; therefore, the rate of heat conduction out of the

node is:

So far, the mathematical formulation of the problem is not closed as there are

unknowns,

temperature points and the electric current

, and only

equations, i.e., two more equations are still needed. The closure of this problem lies in the fact that the total heat input to the TE modules is equal to the convection heat transferred from the flowing fluid to the surface of the exhaust duct and that the open circuit voltage of the TEG is equal to the sum of the individual voltage of each TE leg as they are connected electrically in series.

where

is the fractional area of the hot plate that is in contact with the TE legs,

is the internal resistance of each leg,

is the electrode resistance that connects between the legs, and

is the contact resistance. The open-circuit voltage of each segment

can be calculated from the Seebeck relation:

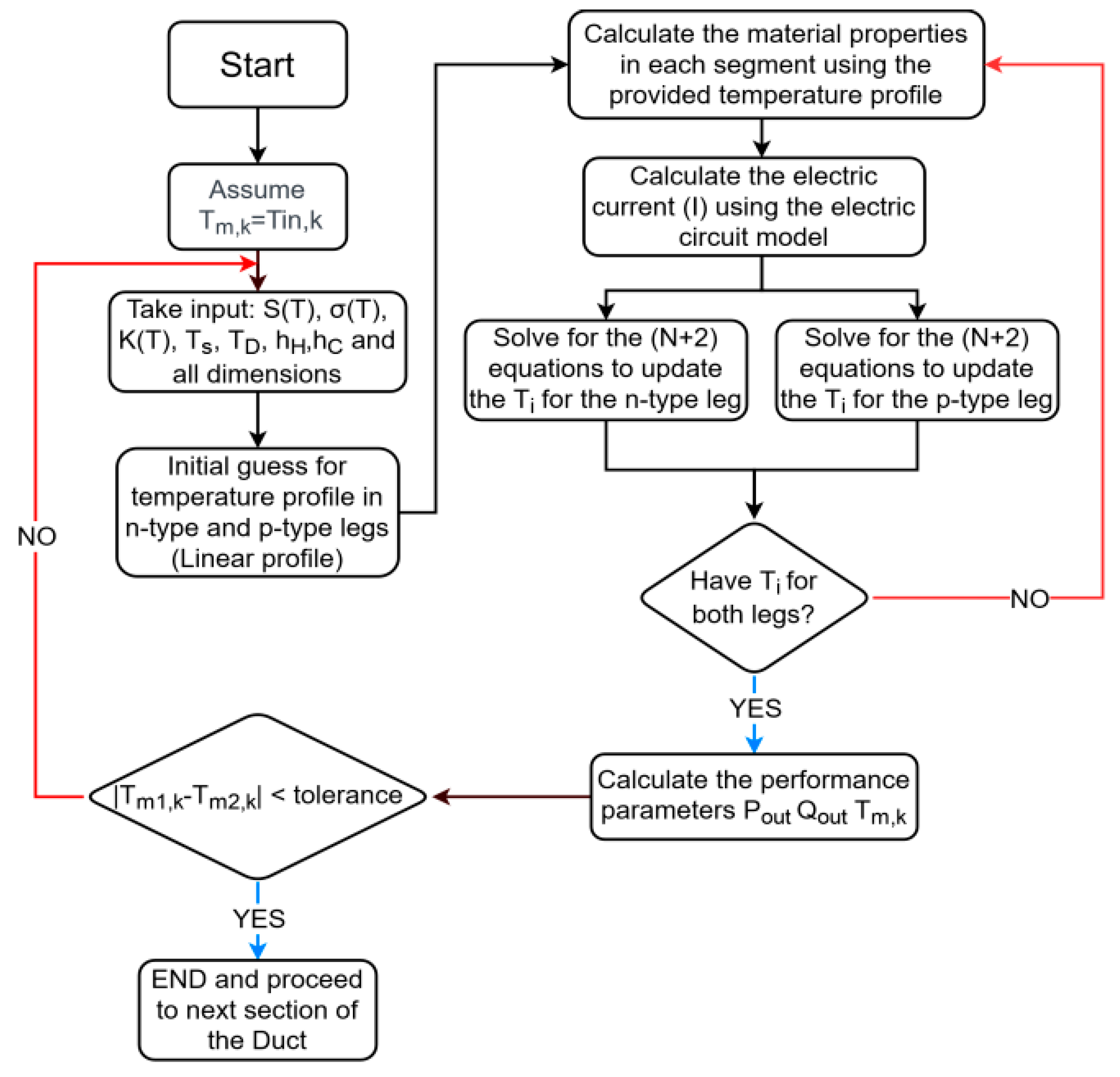

After obtaining the required number of equations, these equations are solved simultaneously multiple times until the temperature profiles of both legs converge. The flow chart of the TE algorithm is shown in

Figure 3, and the performance parameters can be calculated as follows:

To calculate the hot side convection coefficient

, one needs to use equation (18) which corresponds to the Nusselt number of turbulent conduit flow [

38].

where

assuming smooth duct, Re is the Reynolds number given by

and Pr is the Prandtl number given as

. Numerous kinds of heat exchanger have been tested in such TEG systems such as straight fins [

30] or pin fins [

29] on the hot side, and thermosyphon [

39] or flat plates on the cold side. Therefore, various values of

and

are investigated to evaluate their effects on the output power of the TEG system and the consequence of utilizing various heat exchangers. However, the system optimization has been first examined with typical values of a hot side convection coefficient of

and a cold side convection coefficient of

.

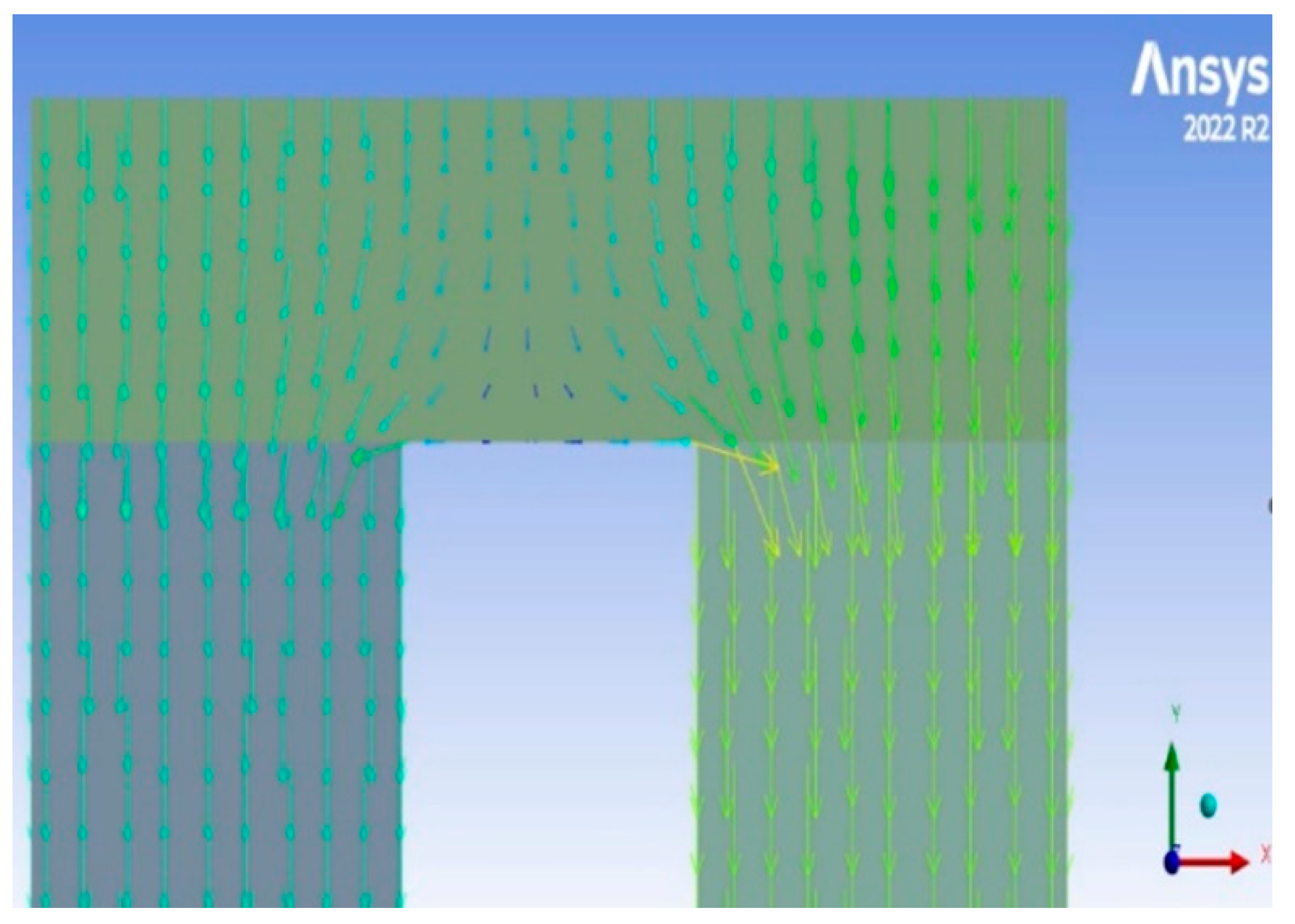

It is worth mentioning that the rate of heat transport through the n-type leg and the p-type leg are not equal because they have different thermal conductivities, and thus different temperature profiles along their thickness. Relying on this fact, Gosh et al. [

21] argued that there is a lateral heat transport through the copper connecting plates, and accordingly they modified the heat input assigned to each leg to match the contact surface temperature. To investigate the viability of this argument, a numerical experiment has been carried out on a pair of TE elements using ANSYS-TE. The results reveal that the heat flux input to each leg comes from the top surface and from the middle section of the connecting plate as shown in

Figure 4. Therefore, we conclude that there is no need to modify the heat input equations and make a two-level iterative algorithm.

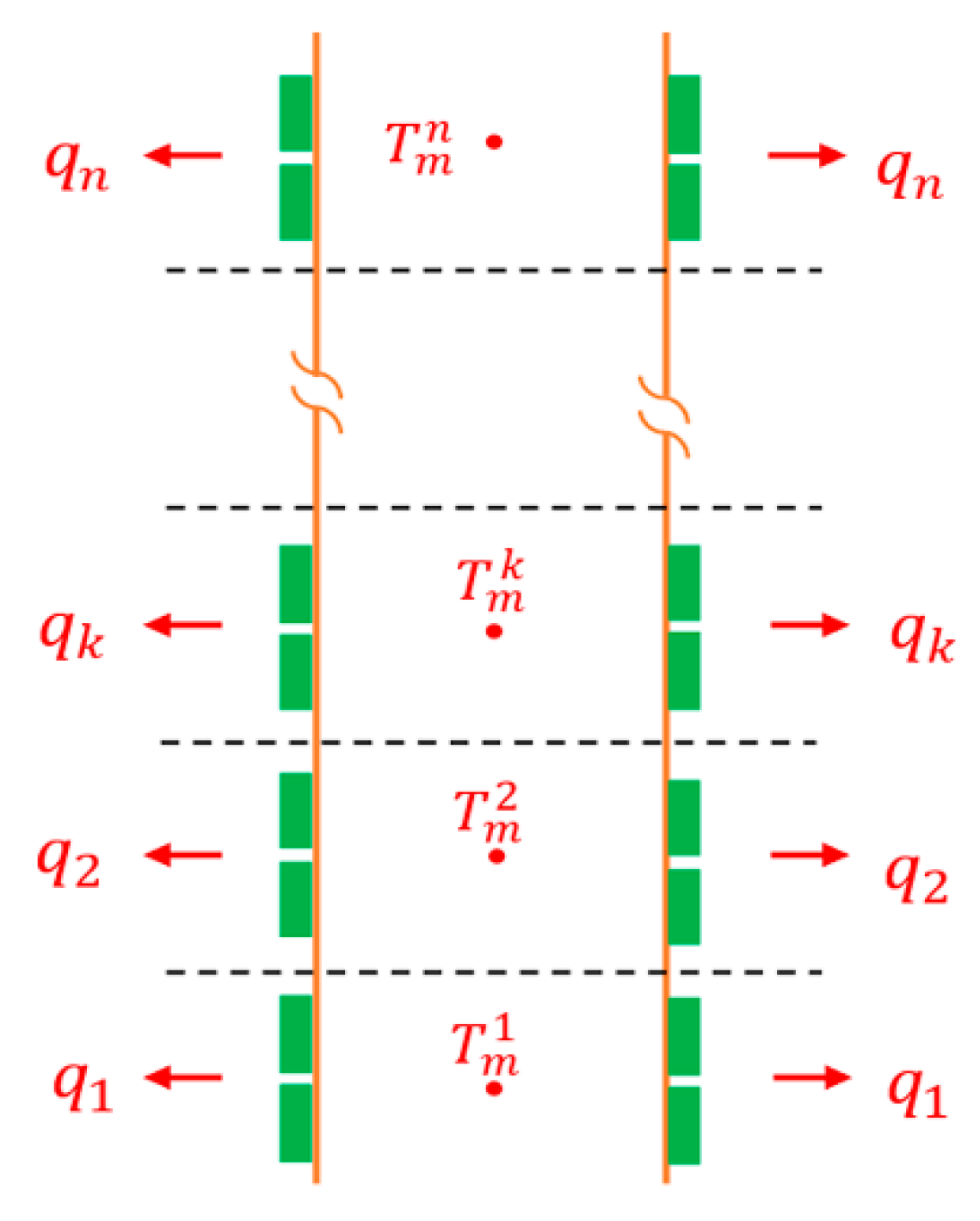

The temperature of the released gases drops along the duct length as a result of heat transfer to the TE generators that are mounted on the outer surface of the duct; thus, an extensive heat transfer analysis needs to be carried out in order to find temperature distribution along the duct length. Therefore, one needs to divide the duct into n number of smaller sections to account for the influence of this temperature variation on the TE properties and the rate of power generation from the TEGs,

Figure 5. Each section has a mean temperature

, which is the heat source temperature for the TEMs attached to this segment, equal to the average of the inlet and outlet mean temperatures of the k-th section, i.e.

. Always, in the first iteration of each segment, the mean temperature is assumed to be equal to the inlet temperature of that segment. Then, this is taken as the heat source temperature in order to start solving the TE equations which eventually give the amount of heat absorb from this segment

among many other parameters. Thereafter, the obtained value is plugged into eq.(19) to obtain the outlet temperature

, and the new mean temperature

is calculated and compared with the one obtained from the previous iteration to check whether the convergence

reach a stipulated tolerance or not. After reaching convergence, the solver proceeds to the next duct of the section to repeat the same process and find the accurate mean temperature. The flow chart of the combined algorithm is shown in Figure 3.

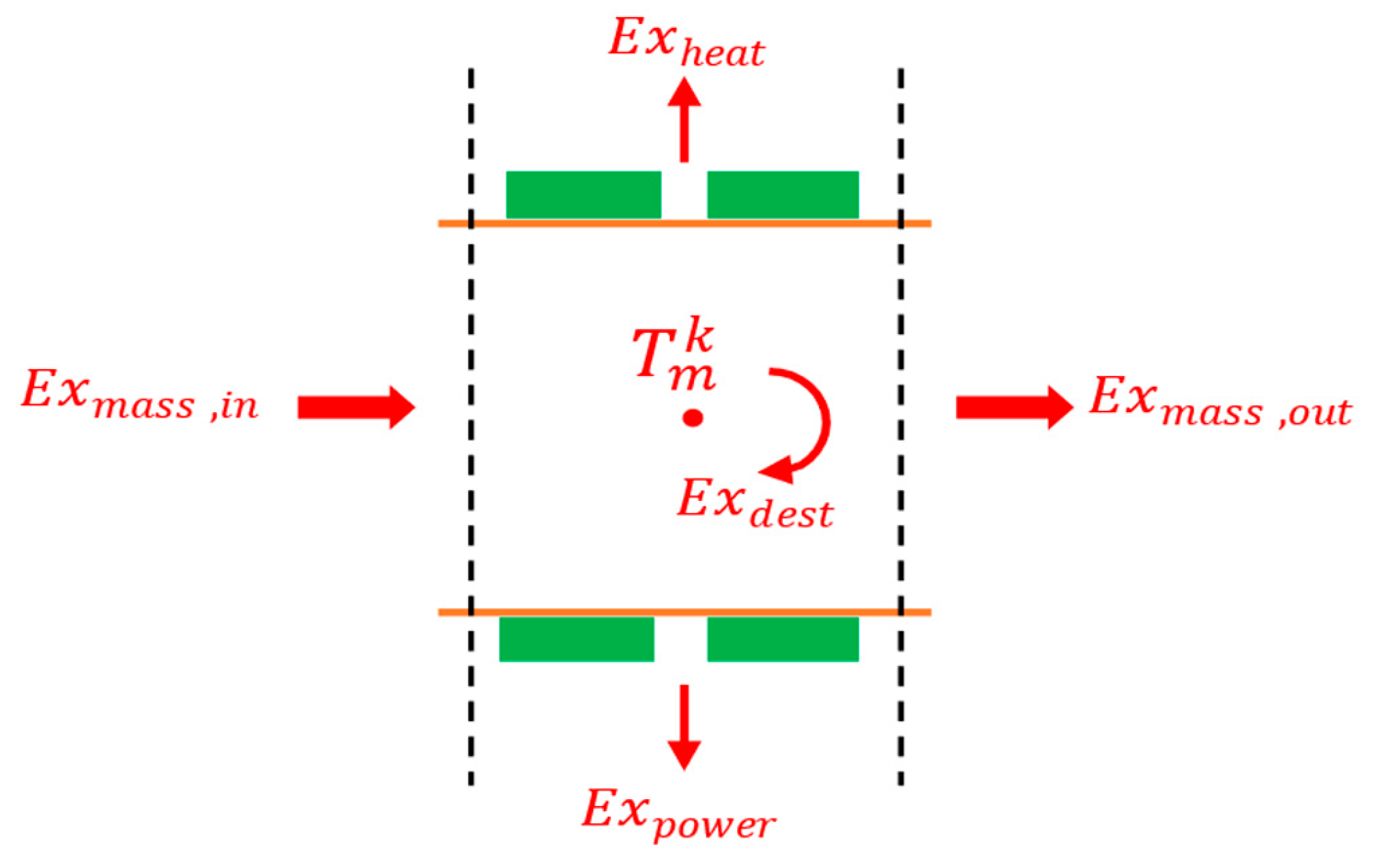

3. Exergy Analysis

Exergy is defined as a thermodynamic property that determines the amount of energy that can be extracted from an available energy source. Exergy analysis is a crucial step prior to the implementation of any energy conversion or heat recovery process as it helps to evaluate and optimize the process design. It can provide an accurate perception of how much the proposed design shifted from the ideal and identify the types and causes of irreversibilities that yield to this shift. Furthermore, exergy can provide an insight into the environmental impact of the proposed heat recovery system and its sustainability through quantifying several exergy related factors such as the second-law efficiency, waste exergy ratio, exergetic improvement potential, and the recoverable exergy. All these factors are known as exergetic sustainability indicators, and they are defined as follows [

37,

40].

The second-law efficiency is the ratio of the useful exergy output to the exergy input of the TEG system such that

where

is the useful exergy output from the TE module, and

is the exergy input to the TE module. From the second law perspective, the exergy efficiency represents the ratio of the actual power produced to the power that would have been produced when there are no thermodynamic irreversibilies in the system. In TE generation, the useful exergy output

is equal to the power generated by the TEG module, while the exergy input (

) is equal to the heat exergy supplied from the flue gases. The input heat exergy equals the exergy difference across each section of the duct.

The waste exergy ratio (WER) is the ratio of the total wasted exergy

to the total exergy input, given by

where

is the sum of the exergy destructed

and the total exergy discarded to the environment

, which is the heat exergy that leaves the TEG.

The exergy improvement potential, IP, is the prospective energy that could be extracted with further improvement of the TE generators, which could be done by enhancing the heat transfer coefficients across the TE legs or improving the figure of merit (

ZT).

It is noteworthy that these factors are evaluated for the TEG system separately. This means the mass exergy that leaves the system to the environment is not considered as waste exergy despite its huge amount.

The recoverable exergy is the potential exergy that could be extracted from the flue gas after it leaves the exhaust duct. It is equal to the difference between the exergy entering the exhaust duct and the exergy entering the TE generators from the flue gas. Thus, the recoverable exergy ratio, RE, is the ratio of the recoverable exergy to the exergy input to the exhaust duct.

An extensive exergy analysis should be performed on the proposed system to be able to calculate the aforementioned exergy indicators. According to the laws of thermodynamics, exergy can be destroyed but cannot be created, and exergy destruction in any thermodynamic system is due to the presence of irreversibilities inside this system, which can be sorted into two categories, namely internal irreversibilities and external irreversibilities. In TE systems, internal irreversitbilities include Joule heating, heat conduction in TE legs, and heat losses to the filler, while external irreversibilities include heat transfer with the heat source and heat sink, and fluid fiction. The exergy change of a system during a thermodynamic process is equal to the difference between the net exergy transfer and exergy destruction within the system, equation (24).

where exergy can be transferred into or out of the system by heat, work, and mass flows across the system’s boundaries. Thus, the exergy of the k-th section of the duct can be written as the exergy of an open system in steady state operation,

Figure 6.

where

is the heat rejected from the TE module. After calculating the exergy destruction of each section, the total exergy destruction of the TE heat recovery system is calculated using equation (26).

This exergy destruction comprises exergy destruction due to heat convection from the flue gases and exergy destruction due to heat transfer through the TEG modules, which can be calculated using equations (27) and (28), respectively.

where

is the heat input to the TEG at the boundary temperature of the exhaust duct

.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrations of (a) a thermoelectric generator (TEG) module and (b) a gas turbine cycle with TEG modules mounted at the exhaust duct.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrations of (a) a thermoelectric generator (TEG) module and (b) a gas turbine cycle with TEG modules mounted at the exhaust duct.

Figure 2.

(a) Discretization of the TE element into N segments to account for the temperature variation along the length (b) Equivalent thermal circuit model of the i-th segment.

Figure 2.

(a) Discretization of the TE element into N segments to account for the temperature variation along the length (b) Equivalent thermal circuit model of the i-th segment.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the combined heat transfer-TE simulation algorithm.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the combined heat transfer-TE simulation algorithm.

Figure 4.

Heat flux from a hot source at the top through a ceramic plate and then a pair of TE elements.

Figure 4.

Heat flux from a hot source at the top through a ceramic plate and then a pair of TE elements.

Figure 5.

Discretization of exhaust duct to account for the temperature gradient along the length.

Figure 5.

Discretization of exhaust duct to account for the temperature gradient along the length.

Figure 6.

Exergy balance on one (k-th) section of the exhaust duct.

Figure 6.

Exergy balance on one (k-th) section of the exhaust duct.

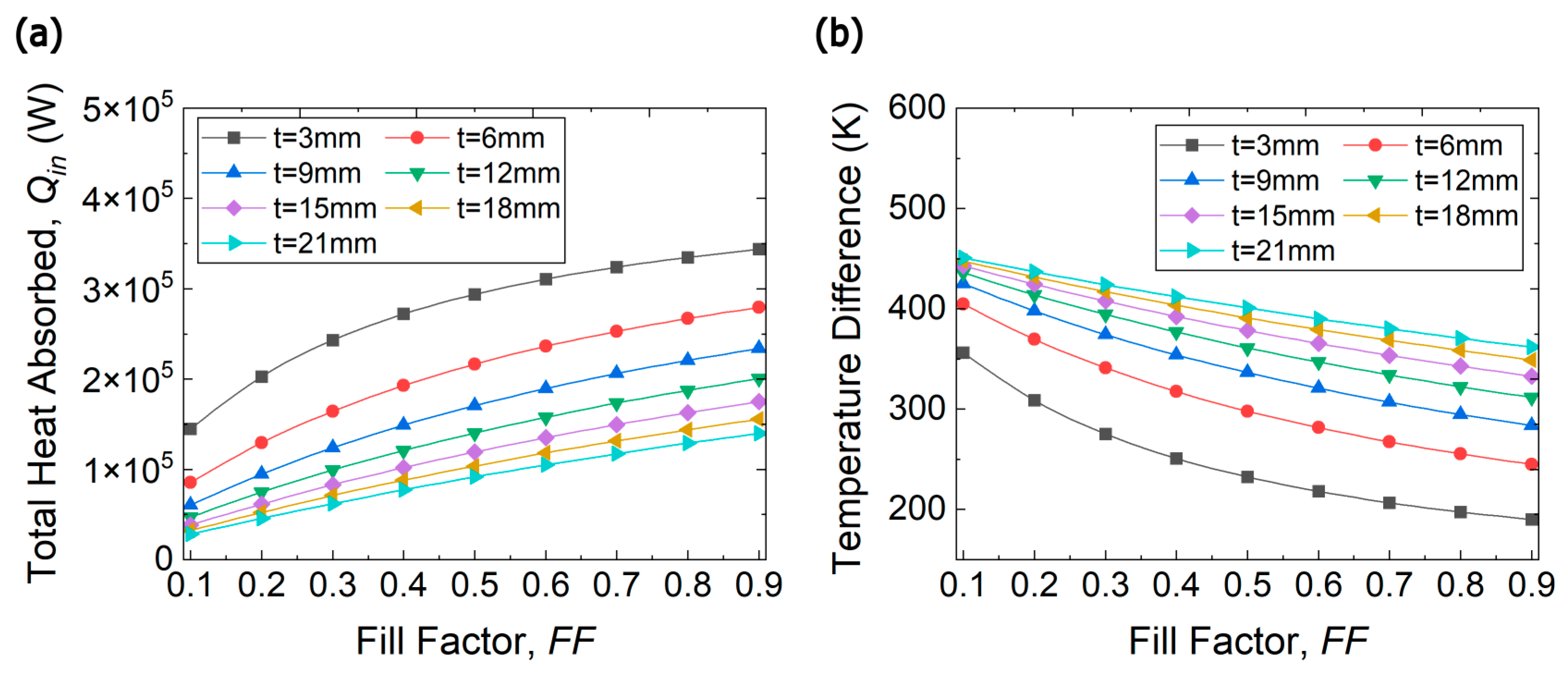

Figure 7.

(a) Total Heat input and (b) Temperature difference across TE legs for a waste heat recovery TE system mounted on the first section of the exhaust duct as a function of fill factor at various leg thicknesses.

Figure 7.

(a) Total Heat input and (b) Temperature difference across TE legs for a waste heat recovery TE system mounted on the first section of the exhaust duct as a function of fill factor at various leg thicknesses.

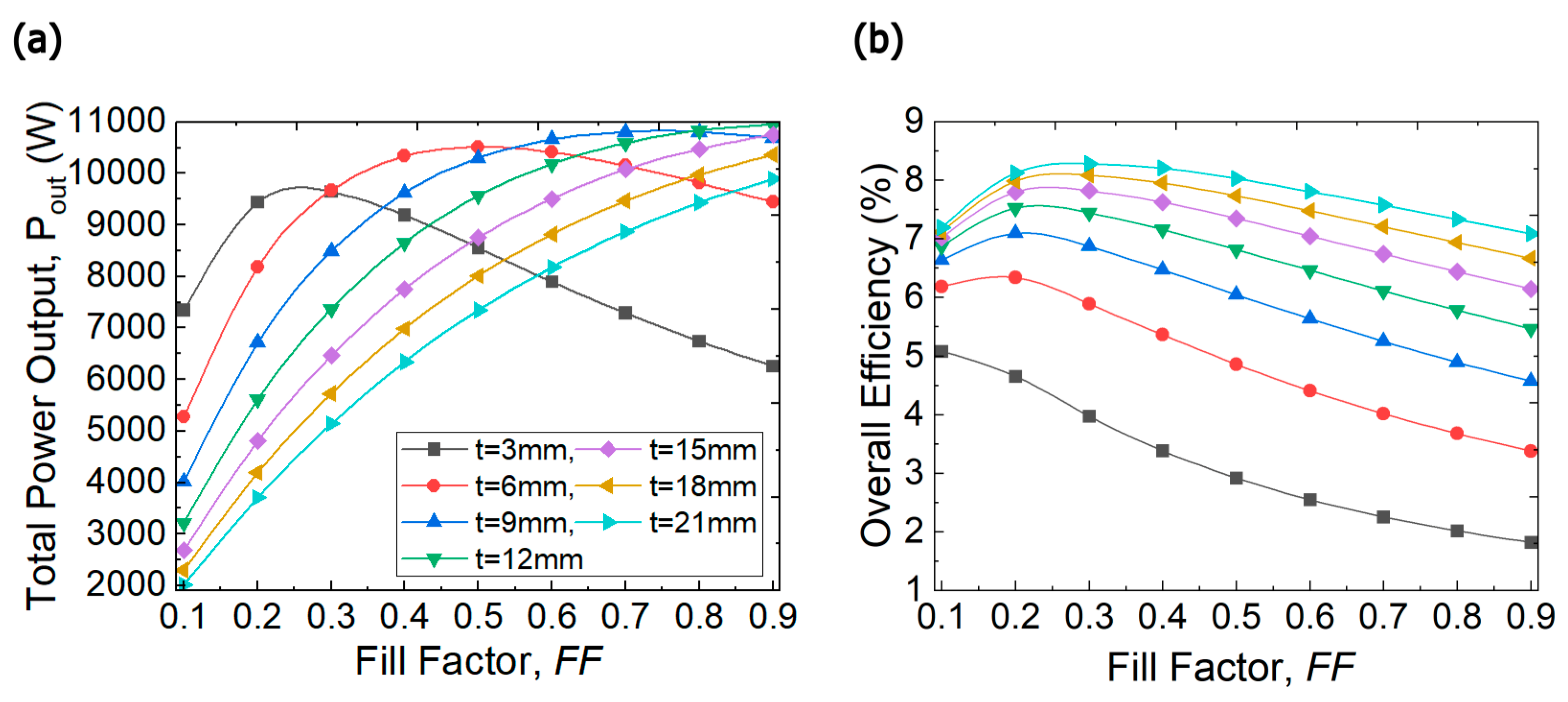

Figure 8.

(a) Total power output and (b) Overall efficiency of the TEG heat recovery system as a function of fill factor at various leg thicknesses.

Figure 8.

(a) Total power output and (b) Overall efficiency of the TEG heat recovery system as a function of fill factor at various leg thicknesses.

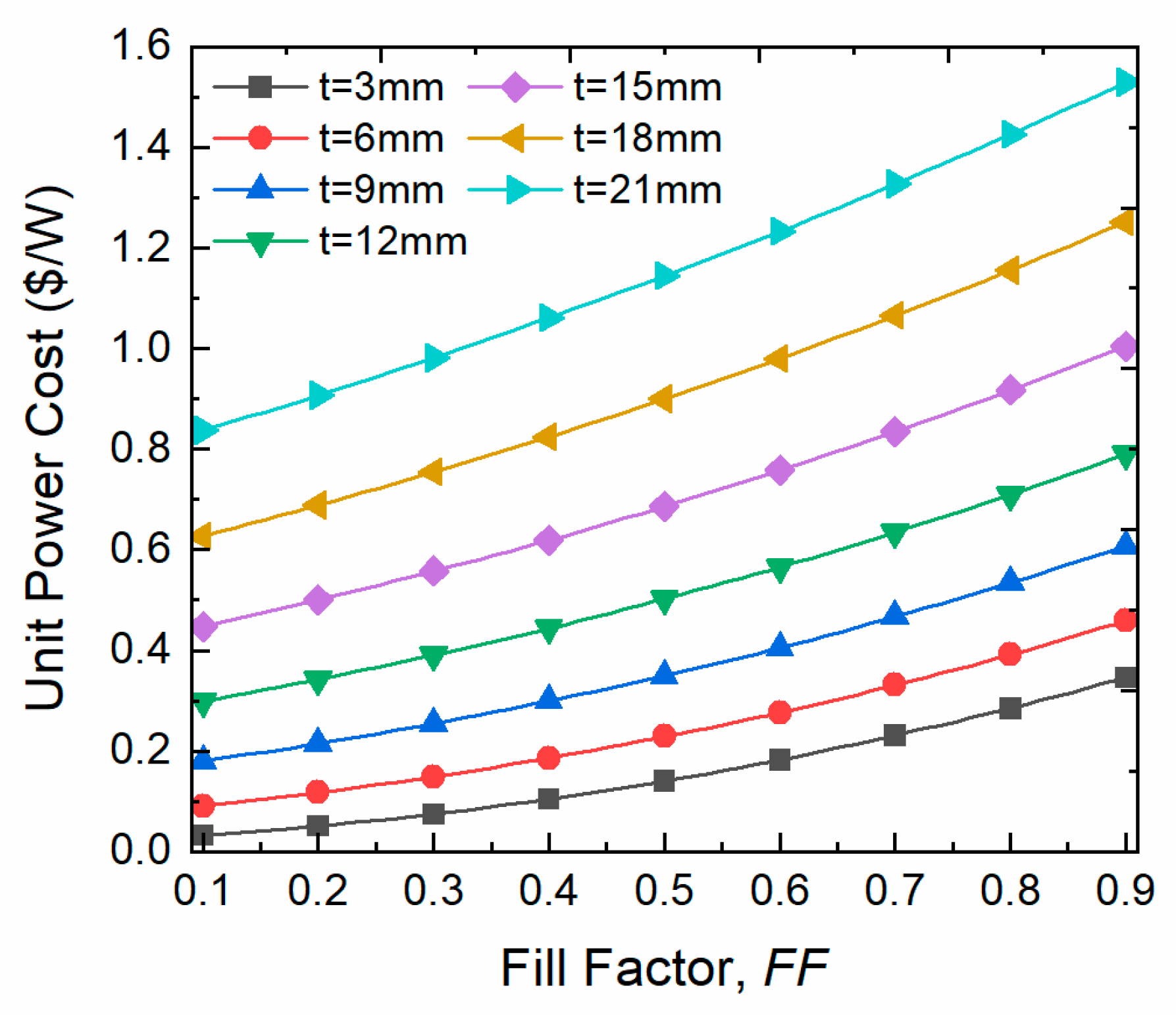

Figure 9.

Power Cost of the TEG heat recovery system as a function of fill factor at various leg thicknesses.

Figure 9.

Power Cost of the TEG heat recovery system as a function of fill factor at various leg thicknesses.

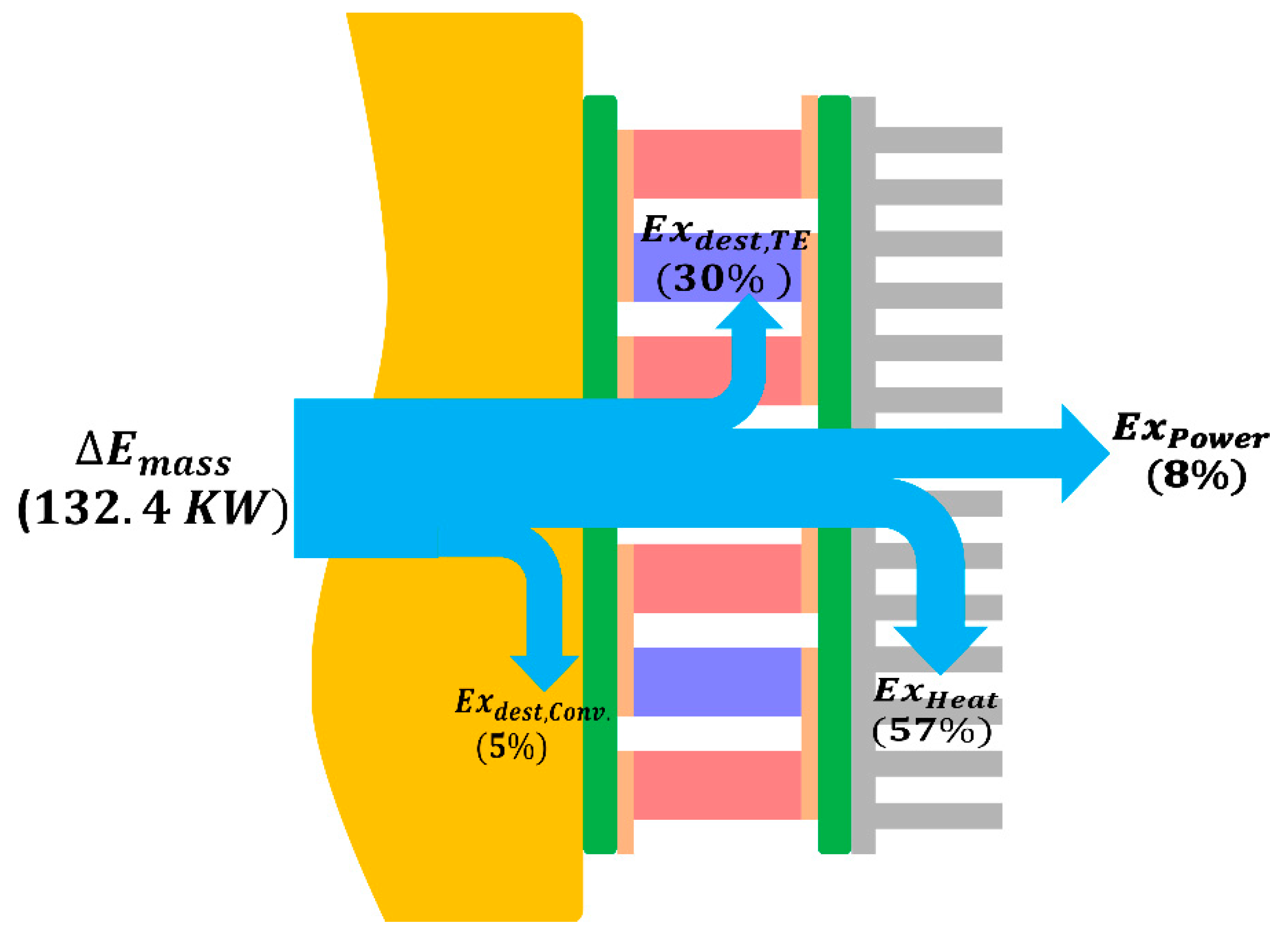

Figure 10.

Exergy flow of the irreversible TE heat recovery system at the optimal design.

Figure 10.

Exergy flow of the irreversible TE heat recovery system at the optimal design.

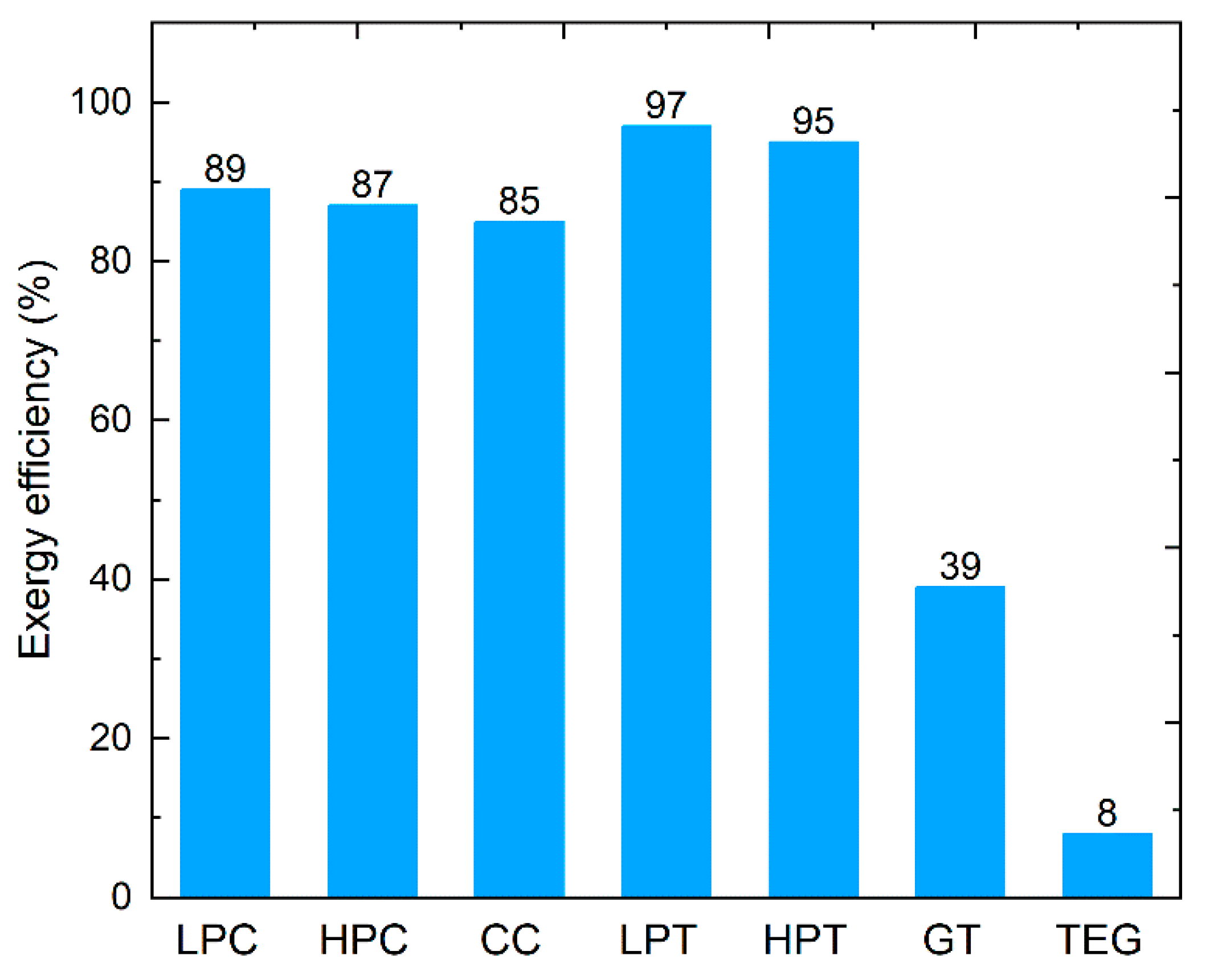

Figure 11.

The second-Law exergy efficiency of the gas turbine components and the TE heat recovery system where LPC: Low Pressure Compressors, HPC: High Pressure Compressors, CC: Combustion Chamber, LPT: Low Pressure Turbine, HPT: High Pressure turbine, GT: Gas Turbine cycle, and TEG: Thermoelectric Generators by this work.

Figure 11.

The second-Law exergy efficiency of the gas turbine components and the TE heat recovery system where LPC: Low Pressure Compressors, HPC: High Pressure Compressors, CC: Combustion Chamber, LPT: Low Pressure Turbine, HPT: High Pressure turbine, GT: Gas Turbine cycle, and TEG: Thermoelectric Generators by this work.

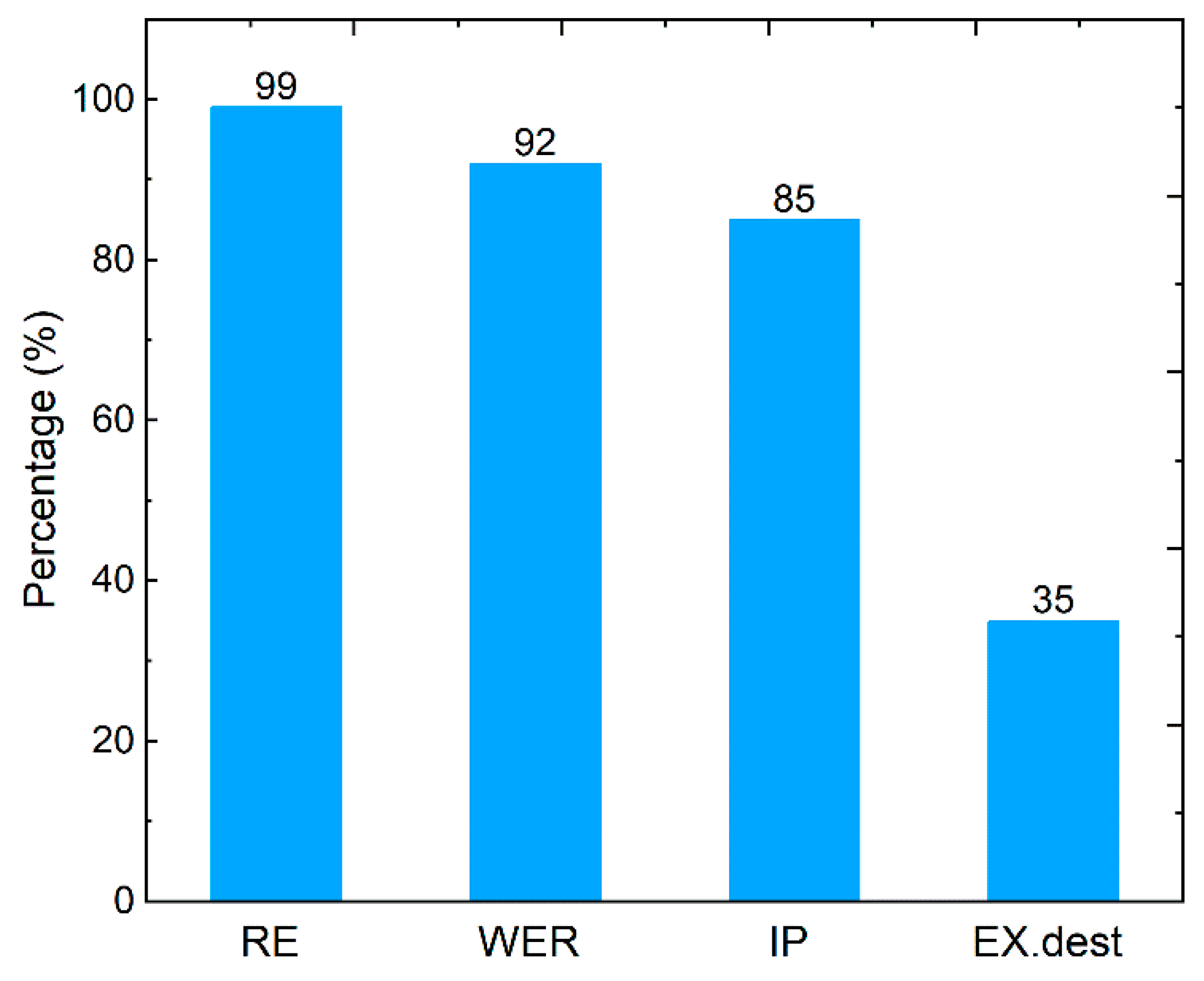

Figure 12.

Exergetic Sustainability indicators of the proposed TE heat recovery system where RE: Recoverable Exergy, WER: Waste Exergy Ratio, IP: Improvement Potential, EXdest: Exergy destroyed.

Figure 12.

Exergetic Sustainability indicators of the proposed TE heat recovery system where RE: Recoverable Exergy, WER: Waste Exergy Ratio, IP: Improvement Potential, EXdest: Exergy destroyed.

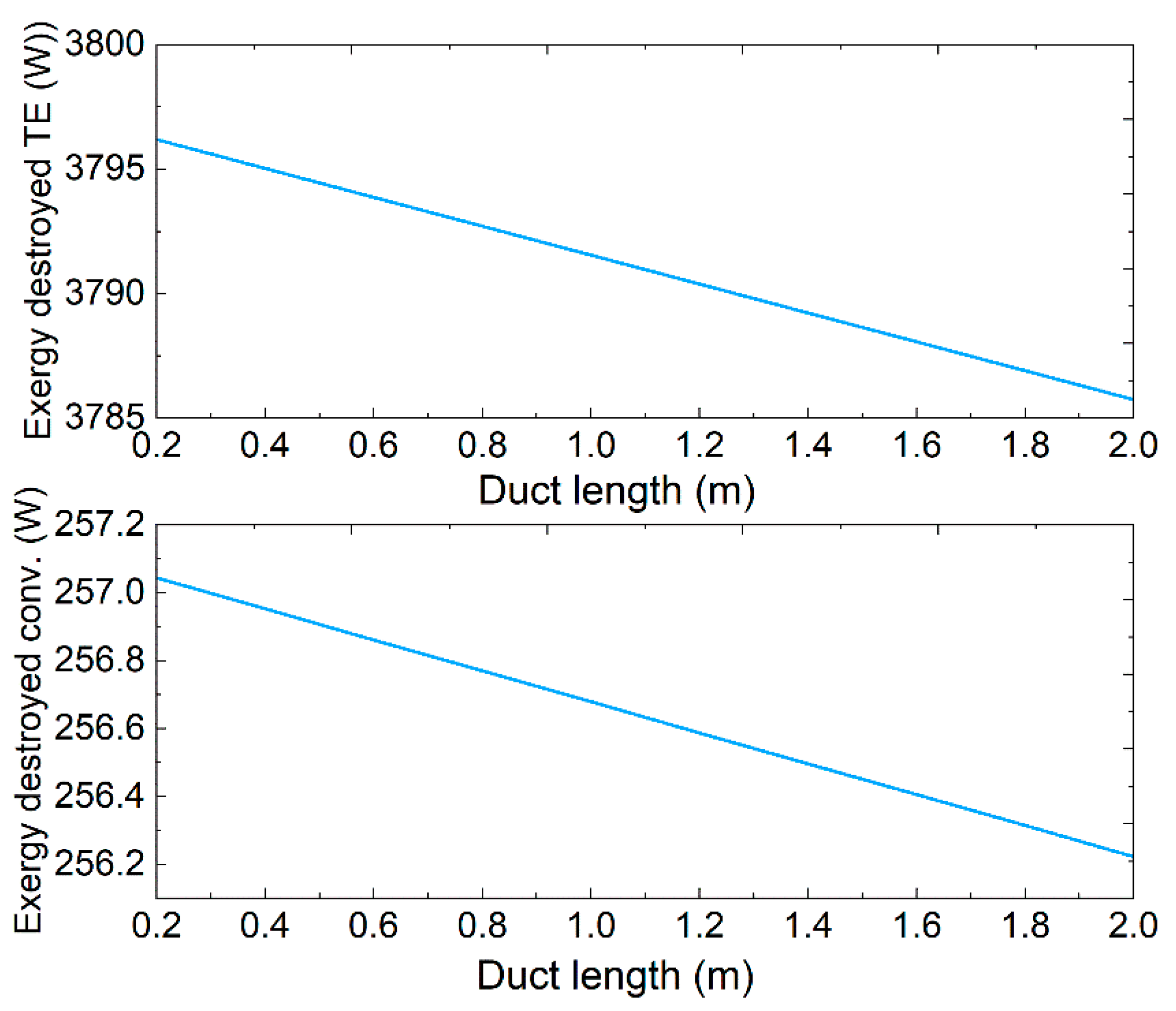

Figure 13.

Convective exergy destruction which is due to heat transfer between fluid layers and fluid friction, and TE exergy destruction due to heat conduction in the p- and n-type legs. Both are along the duct length.

Figure 13.

Convective exergy destruction which is due to heat transfer between fluid layers and fluid friction, and TE exergy destruction due to heat conduction in the p- and n-type legs. Both are along the duct length.

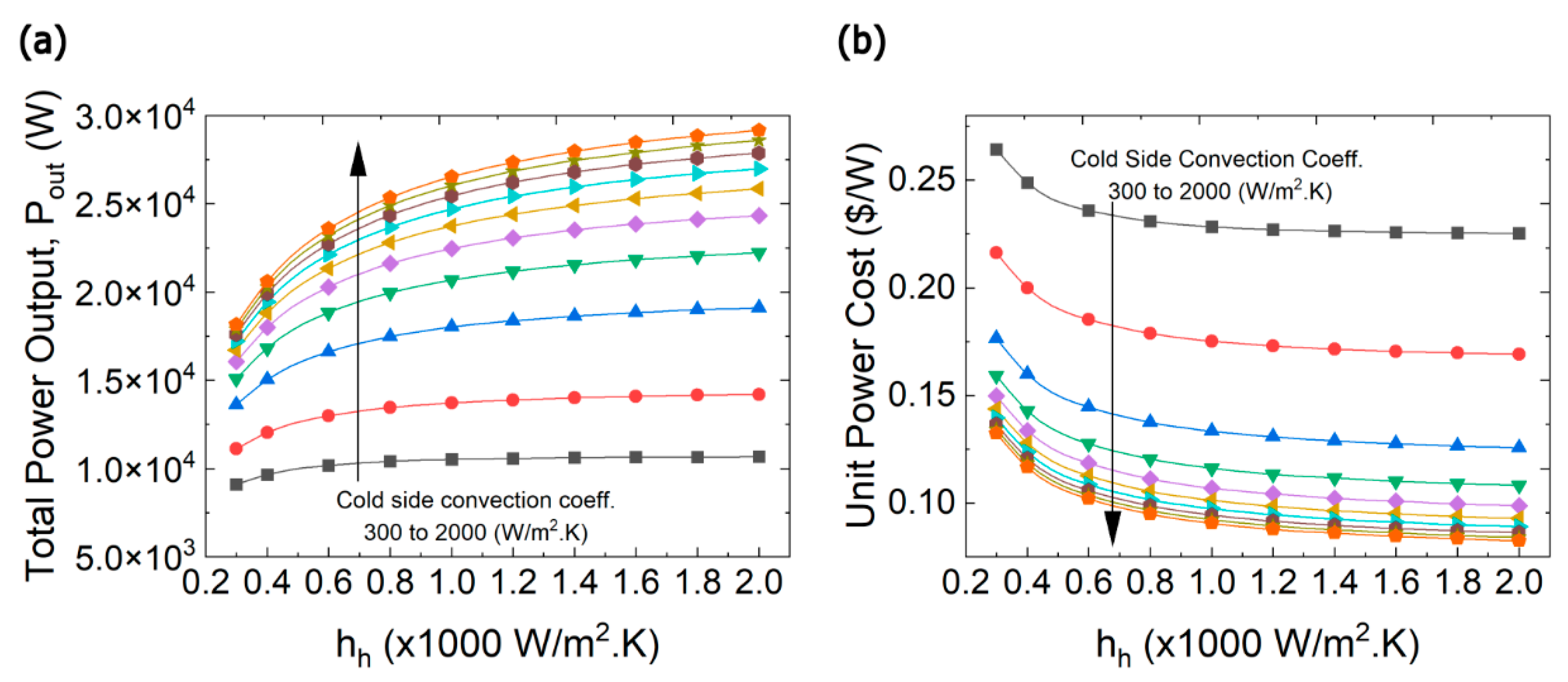

Figure 14.

(a) Maximum power output (b) Unit power cost as a function of convection coefficients.

Figure 14.

(a) Maximum power output (b) Unit power cost as a function of convection coefficients.

Table 1.

Exergy efficiency of the components of Gas Turbine [

37].

Table 1.

Exergy efficiency of the components of Gas Turbine [

37].

| Components |

Inlet Exergy (MW) |

Outlet Exergy (MW) |

Exergy efficiency (%) |

| LPC |

11.62 |

10.33 |

89 |

| HPC |

70.82 |

63.03 |

87 |

| CC |

174.18 |

148.27 |

85 |

| HPT |

148.27 |

146.65 |

97 |

| LPT |

85.56 |

82.84 |

95 |