1. Introduction

Refrigeration plays a vital role in various applications, including the preservation of perishable food products and the control of cooling temperatures in electronic systems [

1]. Conventional domestic refrigerators typically utilize vapor-compression technology. While this technology presents a high coefficient of performance (COP), the refrigerants used in these systems can have adverse environmental effects. In contrast, thermoelectric refrigeration, which is based on the Peltier effect, offers significant advantages over traditional vapor compression technology, even though its COP is not as high [

2,

3]. These benefits include the elimination of refrigerants, a more compact system design, reduced noise and vibration, enhanced temperature control through the variation of their power supply, and minimal maintenance requirements. Moreover, thermoelectric systems can be conveniently powered by direct current (DC) sources, such as photovoltaic cells [

4].

Thermoelectric cooling (TEC) technology is gaining popularity for use in small and portable refrigeration systems, particularly in scientific laboratories where a constant temperature bath is necessary [

5]. This technology effectively cools and maintains the temperature of samples at a specific set point. Thermoelectric cooling devices have found interesting applications in the medical field, serving as the cooling element in the cryoprobes used for cryosurgery, as well as being used for cooling the brain or skin [

6]. Additionally, they are employed in cryotherapy systems where precise control of skin blood flow is required [

7].

When selecting an air conditioning system based on thermoelectric devices for a particular application, it is important to evaluate not only the TEC coefficient of performance and the required cooling capacity at the desired temperature. We must take into consideration also the operational characteristics of the cooling system and overall energy consumption, with various types of losses associated with the thermodynamic process of heat transfer at the cold and hot side of TEC. Jurkans and Blums [

8] investigated a practical method to increase the efficiency of thermoelectric cooling. They experimentally validated a simple model that evaluated the induced heat loss and the recovered energy after a dynamic switch of the thermoelectric module between cooling and electrical energy generation modes.

From a thermodynamic point of view, the second law analysis and Entropy Generation Minimization (EGM) method has proved to be very powerful tools in the optimization of TEC systems, with the evaluation of the minimum system irreversibility and maximum exergy contribution at a constant environmental temperature [

9,

10,

11]. Tipsaenporm et al. [

12] analyzed the thermodynamic properties of a compact thermoelectric air conditioner using an exergy analysis approach. They found that the exergy efficiency of the cooling system was relatively low compared to its coefficient of performance. Many TEC-based cooling system studies have been focused on maximizing cooling capacity and coefficient of performance for the overall refrigeration system, improving exergy efficiency as the temperature difference between the TEC hot and cold side’s increases. The optimal performance of a single-stage TEC can be achieved by adjusting both the operating current and the TEC’s configuration [

13].

The practical purpose of this refrigeration box is to serve as a cooling medium, providing a viable and cost-effective alternative to the expensive thermostatic water bath. We propose enabling the efficient extraction of phenolic compounds from hydroalcoholic mixtures of various fruits and leaves at optimal temperatures of approximately 10°C using the ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) method [

14,

15,

16]. We will modify the upper section of the refrigerated box to accommodate the insertion of an ultrasonic transducer, which will be in direct contact with the liquid sample contained in a 100 ml glass placed inside the box. For the current refrigeration test with a water load, we aim for a liquid cooling point of 12°C inside the refrigeration box.

2. Thermodynamic Modelling of Thermoelectric Cooling System

Thermal model of the refrigeration system and energy analysis

The mathematical model presented in this study for analyzing the thermodynamic behavior of a thermoelectric cooling system considers one-dimensional energy balance and heat transfer equations applicable to air-cooled heat exchangers. We considered some assumptions for the model simplification [

17]: (i) heat transfer between the hot and cold sides of the thermoelectric cooler (TEC) is one-dimensional and occurs under steady-state conditions, (ii) the Thomson effect is neglected, and (iii) the Seebeck coefficients, electrical resistivity’s and thermal conductivities of the p-type and n-type thermoelectric materials are assumed to be constant, determined at a specific operating temperature.

When a heat sink is placed onto the hot side of the TEC cooler, thermal transfer occurs only at the points where the two surfaces make direct contact. The heat transfer region typically accounts for around 5% of the total area, while the remaining 95% consists of microscopic gaps where no contact is made [

18]. To enhance heat conduction, thermal paste is applied to fill these gaps and improve the overall contact between the surfaces.

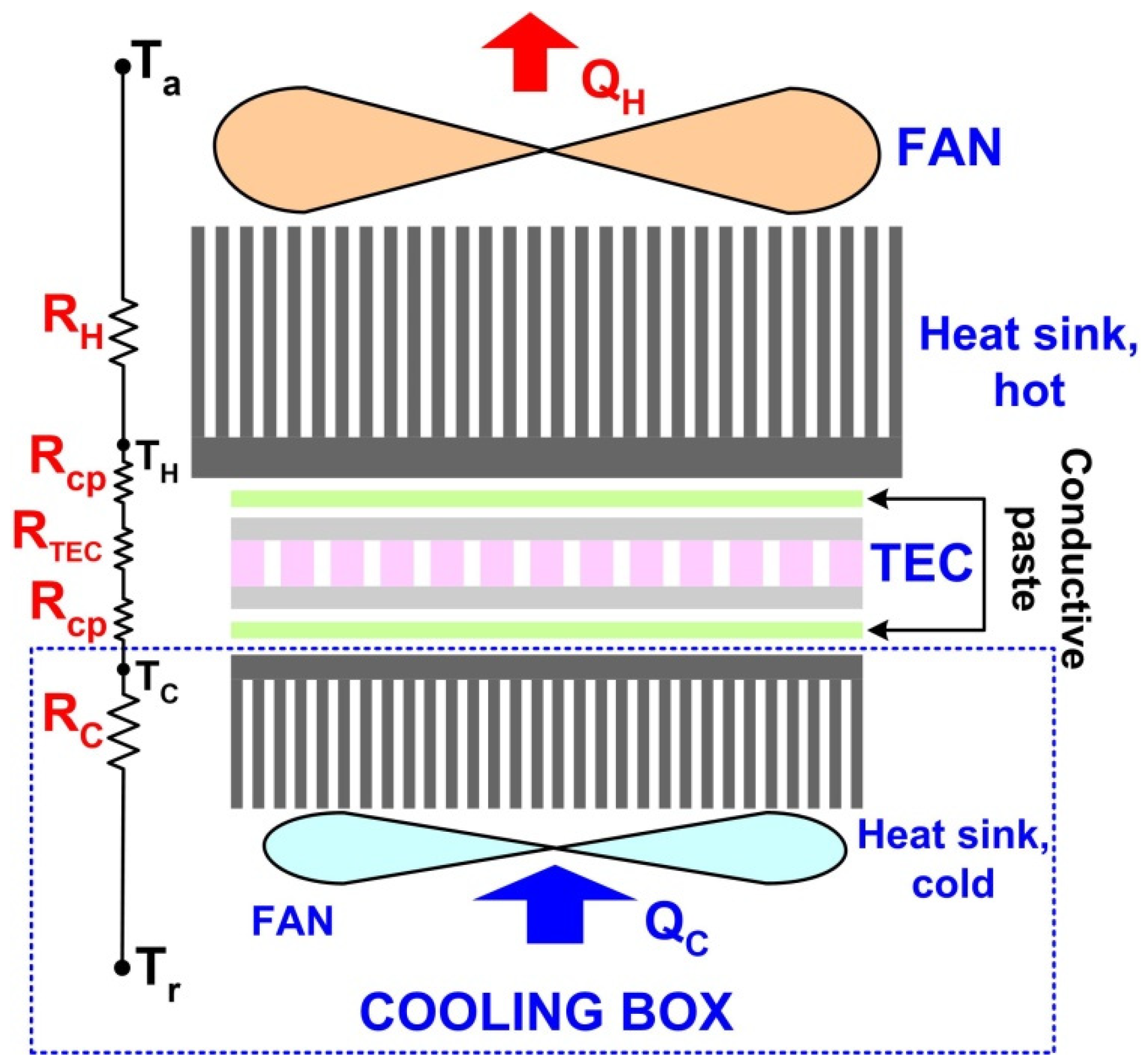

Figure 1 presents the thermal resistance network diagram of the thermoelectric refrigeration system, considering the thermal resistances imposed by the hot – end and cold -end heat sinks, the TEC module and the thin layers of thermo-conductive paste between the heat sinks and ceramic plates of TEC device.

The total thermal resistance of this refrigeration system is calculated as:

The thermal resistance of the TEC module,

RTEC (°C/W), was calculated here with the following relation [

17]:

In relation (2), the maximum operating voltage and current Umax and Imax, respectively, the maximum value of the temperature gradient between the hot and cold plates of TEC, ΔTmax, identified at a specific hot – side temperature TH,ref, are all obtained from the datasheets of thermoelectric devices.

The Fourier law of heat conduction was considered here for the calculation of thermal resistance of the silicon – type conductive paste:

For a conductive paste thickness tcp = 0.2 mm with thermal conductivity kcp = 1.2 W/moC and a cross section area of TEC ceramic plates Ap = 16∙10-4 m2, Rcp = 1.04 oC/W.

Thermal resistance of the heat sink at the hot and cold surface of thermoelectric module,

RH and

RC, respectively, can be evaluated with relations [

19]:

In relations (4) and (5), TH and TC represents the hot – side and cold – side TEC temperatures; Tr and Ta are the air temperature inside the cooling box and the ambient air temperature outside the refrigerator system, respectively. TH, TC, Tr and Ta are measured according to the specific experiment stage.

The total amount of heat absorbed at the TEC cold plate,

QC (W), is calculated with the following expression [

8,

20]:

The amount of heat transferred to the heat sink from the TEC hot plate,

QH (W), is expressed as [

8,

20]:

In the relations above, It is the current absorbed by the TEC module from the power supply. The three physical property parameters of the thermoelectric device, Sm, Rm and Km represent the Seebeck coefficient, electrical resistance and thermal conductivity, respectively.

The values of

Sm,

Rm and

Km are estimated from the specific performance curves provided in each of the datasheets of TEC devices used in this study: TEC1-12706, TEC1-12705 and TEC1-12703 [

21,

22,

23]. Three sets of curves are considered, for a standard

TH = 27

oC:

QC as a function of thermal gradient

ΔT between the TEC plates at different current values

I, Voltage

U as a function of

ΔT for different current values and

Qc as a function of voltage

U at different

ΔT values.

From the slope of U - ΔT curves at ΔT = 0, selected for current values I as close as possible to the experimentally measured It, we could obtain Rm =U/I (Ω) for each of the TEC devices.

The Seebeck coefficient is evaluated considering the expression [

24]:

were

TC = TH so

ΔT = 0 and the only independent variables are

Qc and

I. The value of

Sm is obtained by considering the pair of values (

QC, I) at

ΔT = 0 for

I ≈ It.

Finally, the thermal conductivity of the TEC module will be calculated by considering a pair of values (

I,

ΔT), extracted from the curve associated with

QC = 0, using the relation [

24]:

The values of

Sm,

Rm and

Km obtained for TEC1-12706, TEC1-12705 and TEC1-12703 devices are presented in

Table 1.

The power consumption of the thermoelectric module, necessary for system cooling, is assessed as described in [

8]:

The first term in equation (18) corresponds to the total Joule power losses, while the second term represents the contribution of the Seebeck effect.

The refrigeration performance of thermoelectric cooler module is investigated through the

Coefficient of Performance (COP), defined as a ratio between the cooling capacity of TEC and his power consumption [

4]:

The

entropy generation inside a thermodynamic system represents a measure of the irreversibility for a mass and/or heat transfer process [

25]. Thermodynamic losses and the inefficiencies present inside an energy transfer system can be quantified through the

exergy analysis, a fundamental tool for the evaluation and improvement of the global efficiency of the system.

Exergy represents a thermodynamic property which determines the quality of all the energy flows along the system, from inputs to outputs.

The thermal conductance and internal electrical resistance of the thermoelectric materials, in conjunction with a finite heat transfer rate between the TEC module and heat sinks will contribute to an increase of the entropy generation [

11]. The heat transfer between the hot plate of TEC and heat sink, the convective heat transfer between the heat sink and surroundings, along with the electrical charge transport between the hot and cold plate of thermoelectric module will generate the occurrence of external and internal irreversibilities and the enhancement of entropy generation rate.

The exergy balance inside the thermoelectric cooling system can be expressed as [

26]:

were T

0 is the environment temperature and

Pin = Pt, representing the 100% exergy input [

26].

In the right hand side of the relation (20), the first term represents the exergy collected at the cold side of TEC module, being the reversible work inside the cooling system and the third term is the exergy removed from the TEC hot – side; the second term is the system irreversibility (energy destruction), defined as [

26]:

were the

total entropy generation rate of TEC module,

Sgen-T, is defined as below [

27]:

The lowest feasible temperature of heat rejection for the thermoelectric cooling system is the environment temperature [

10], so

T0 = TH.

The

exergy efficiency of the thermoelectric cooler, known also as the

second – law efficiency, will be defined as the ratio between the exergy output and energy input, using the relation [

28,

29]:

Thus, the

exergy efficiency will be calculated with expression [

27]:

3. Performance Analysis of the Thermoelectric Cooling Unit

The main purpose of this air – cooled thermoelectric refrigeration investigation is to establish the cooling performance of the system with an optimal TEC module in the presence of a cooling load. For this purpose, a 100 ml Berzelius glass was placed inside the cooling box.

The coefficient of performance for the entire refrigeration system was calculated with expression [

29]:

were

We is the total electrical power consumed by the cooling system, and

QT (W) represents the refrigeration load (total heat rate developed inside the cooling box), evaluated with relation [

29]:

In the relation above, Qcb (W) is the heat flux through the cooling box, Qpl (W) is the product load as the heat removed by the water glass in the refrigerator and Wfan (W) is the electrical power consumption of the external and internal system fans.

The product load and heat flow inside the cooling box are calculated with relations [

29]:

In relation (21), m (g) is the mass of the water product, Cp (J/g∙K) is the specific heat capacity of water product, Tp,i and Tp,f (K) are initial and final temperatures of the water product, respectively, and Δt (s) is time interval for the water cooling from Tp,i to Tp,f.

In expression (22),

A (m

2) is the internal surface area of the cooling box and

U (W/m

2K) is the overall heat transfer coefficient, defined as [

29]:

with the wall thickness and thermal conductivity of the polystyrene – based cooling box,

dcb = 4cm and

kcb = 0.035 W/mK, respectively.

In relation (23),

hint and

hext (W/m

2K) are the air heat transfer coefficients at the inner and outer part of the refrigeration system. These coefficients are linked to the real heat transfer coefficients for air under forced convection through plate fin heat sinks, based on an analytical composite model developed by P. Teerstra et al. [

30]:

were

ηx represents the

fin efficiency for the external and internal heat sink and

hi,x (W/m

2K) is the

ideal heat transfer coefficient for the air at the inner and outer surface of the cooling box, calculated with the following expression [

30]:

In relation (25), ka,x (W/mK) is the air thermal conductivity evaluated at a specific temperature outside and inside the refrigeration box, Ta and Tr, respectively.

The ideal Nusselt number value

Nui,x for the air is expressed through relation [

30]:

In expression (26),

Prx and

represents the Prandl number and Reynolds number for each channel of the external and internal heat sink, calculated with relations [

30]:

In relations above, μa,x (Kg/m∙s), Cpa,x (J/KgK) and νa,x (m2/s) are dynamic viscosity, specific heat capacity and kinematic viscosity of air, respectively, calculated at specific Ta and Tr values.

In relation (28), valid for , Ua,x (m/s) is the experimentally measured air velocity under forced convection at the boundary of external and internal fan.

The geometrical parameters for the external and internal heat sinks are presented in

Table 2.

All the heat sink dimensions were measured using a digital caliper with resolution of 0.01 mm and accuracy of 0.03 mm.

In

Table 1,

N is the number of fins,

W is the sink base width,

L is the sink base length,

t is the fin thickness,

b is the distance between fins,

Ht is the heat sink height and

H is the fin height.

Under the composite model of air forced convection through parallel plates of the heat sink considered in this study, the

fin efficiency can be expressed as [

30]:

were

ks (W/mK) is the fin thermal conductivity, with a value of 220 W/mK for the Aluminium Alloy EN AW-6060 [

30].

We can see in relation (29) that the decrease of the ratio H/b (or H/t) would reduce the thermal resistance through the fins, and η can approach the ideal value of 1.

4. Experimental Set-Up

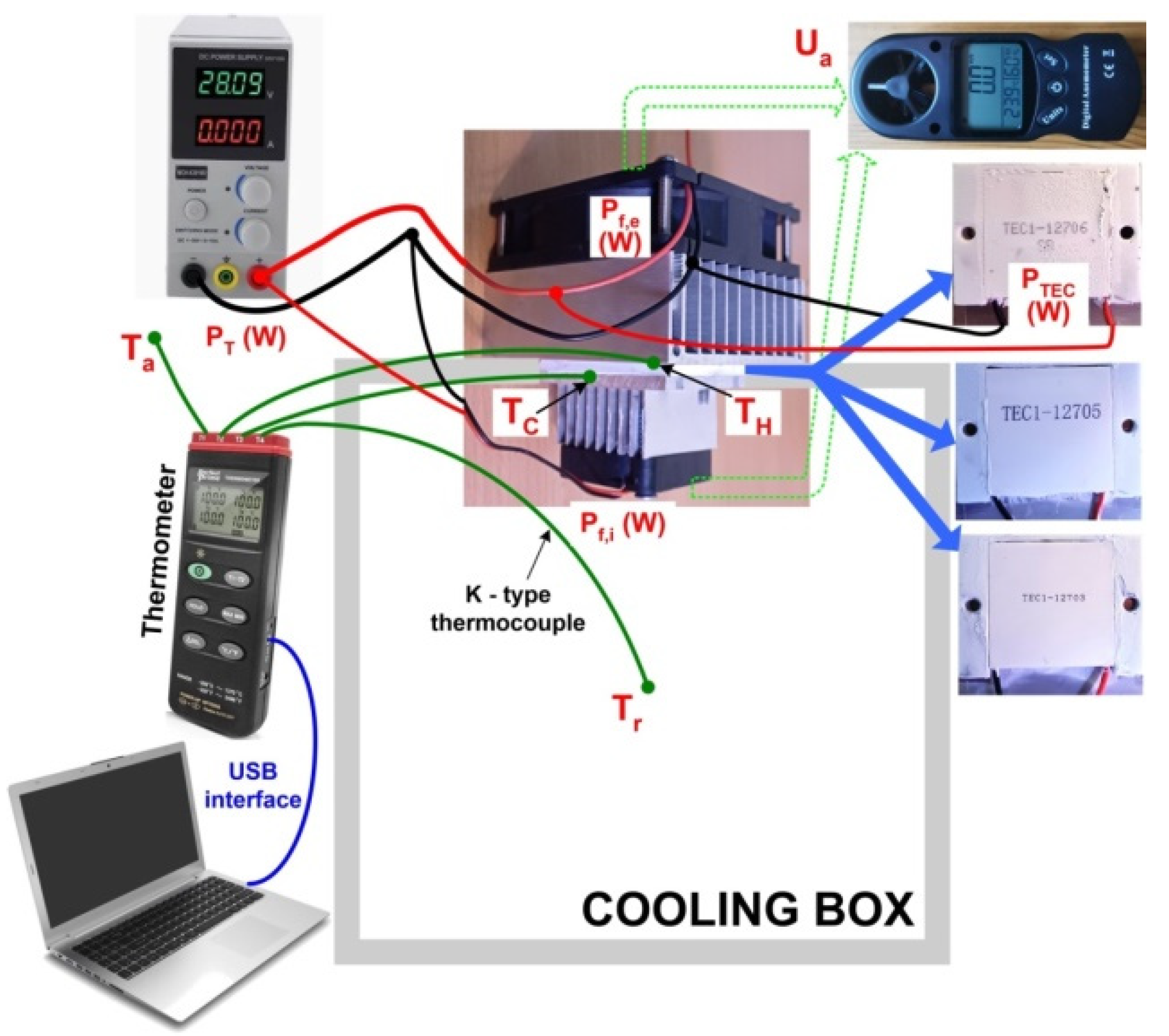

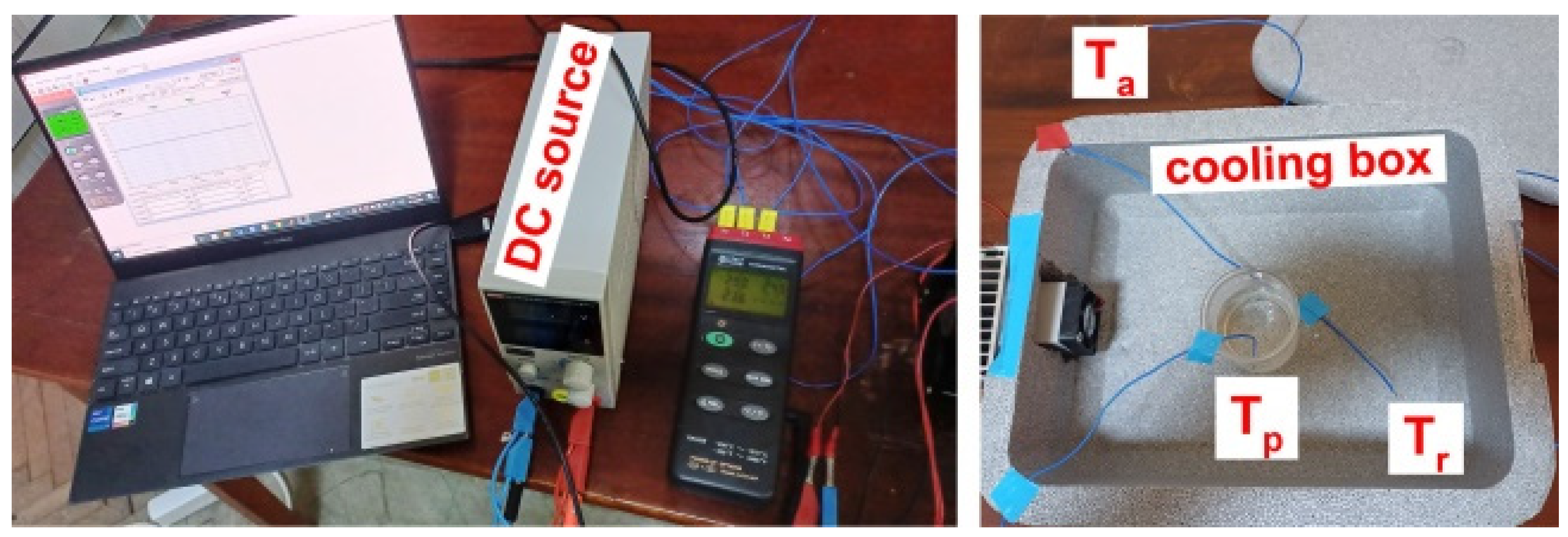

Two different configurations of thermoelectric cooling systems were considered here. The first one, presented in

Figure 2, contained the cooling box with air load and was used for the performance evaluation of three different thermoelectric cooling modules. For the second configuration, presented in

Figure 3, we considered a water glass of 100 ml as a cooling load for the refrigeration box.

We used here a server station cooling FAN 8025 DC 12V – 0.4 A (JLJ Electromechanical, China) for the forced air convection trough external heat sink. The cooling air inside the box was circulated by a small DC brushless fan 12V-0.12A (CJY Electronic, China) placed on the boundary of internal heat sink.

We tested thermoelectric coolers type TEC1 – 12703, TEC1 – 12705 and TEC1 – 12706, based on 127 bismuth telluride (Bi

2Te

3) semiconductor couples (

n - type and

p – type), with similar dimensions

LxWxH (mm): 40 x 40 x 3.8 (

0.1) mm, characterized by different thermo - electrical parameters (see

Table 1). In the datasheets, the maximum values of the voltage, DC current and cooling capacity,

Umax,

Imax and

Qc,max, respectively, are specified for a maximum temperature gradient

ΔTmax = 70

oC, at a hot side temperature

Th0 = 27

oC.

Table 3.

Specifications of the thermoelectric modules TEC used in this study [

21,

22,

23].

Table 3.

Specifications of the thermoelectric modules TEC used in this study [

21,

22,

23].

| TEC model |

Umax (V) |

Imax (A) |

Qc,max (W) |

| TEC1 - 12703 |

15.8 |

4 |

39.8 |

| TEC1 - 12705 |

16 |

5.4 |

54.1 |

| TEC1 - 12706 |

16 |

6.1 |

61.4 |

As we can see in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, experimental cooling system contains a cooler box made from expanded polystyrene, with the inner dimensions of 26 x 20 x 9.5 cm and the wall thickness of 4 cm. Temperatures at the surface of TEC hot plate

TH, TEC cold plate

TC, refrigerated air inside the box

Tr, ambient temperature

Ta and water load inside the glass

Tp were measured using a four - channel PerfectPrime TC0304 digital thermometer (resolution of 0.1

oC and accuracy of ± 1

oC), with K-type thermocouples as temperature sensors. The power supply for the TEC module, external and internal fans,

PTEC,

Pf,e and

Pf,i, respectively, was provided by a 300W MCH – K310D DC source (± 0.5% voltage/current display accuracy). Two Kafuter K – 523 thin films of thermally conductive paste with a thermal conductivity of 1.2 W/mK, placed between the hot/cold plate of TEC module and external/internal heat sinks, offered a maximization of heat transfer between the metallic/ceramic surfaces.

Experimental temperature data were recorded through a USB connection between the thermometer and PC using the TestLink TC0309 software.

5. Results and Discussions

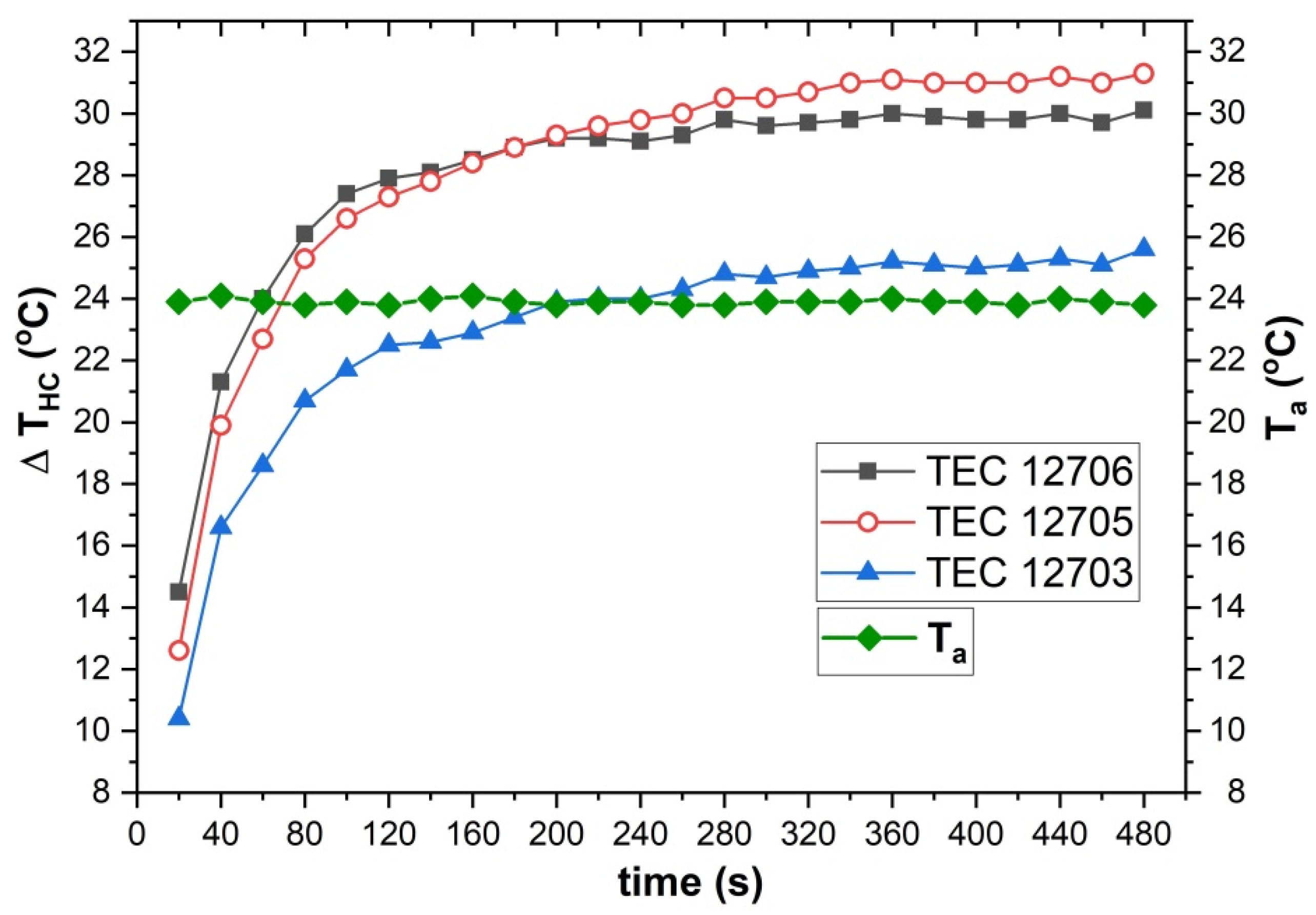

In the first stage of the study, we investigated the cooling performances of three different commercial TEC devices inside the same cooling box with an air load. The average electrical power consumption (PTEC) of the three thermoelectric module modules, TEC1 - 2703, TEC1 - 12705 and TEC1 - 12706, indicated by the power supply at the beginning of each test was 28.18 W, 34.65 W and 53.19 W, respectively.

Figure 4 presents the variations in time for the hot side – cold side temperature gradient of the TEC modules,

ΔTHC = TH – TC, along with the evolution of ambient temperature

Ta. We could observe a slight increase with about 1

oC of

ΔTHC in the case of TEC1- 12705 testing by comparing it with TEC1- 12706 testing during the last 3 minutes.

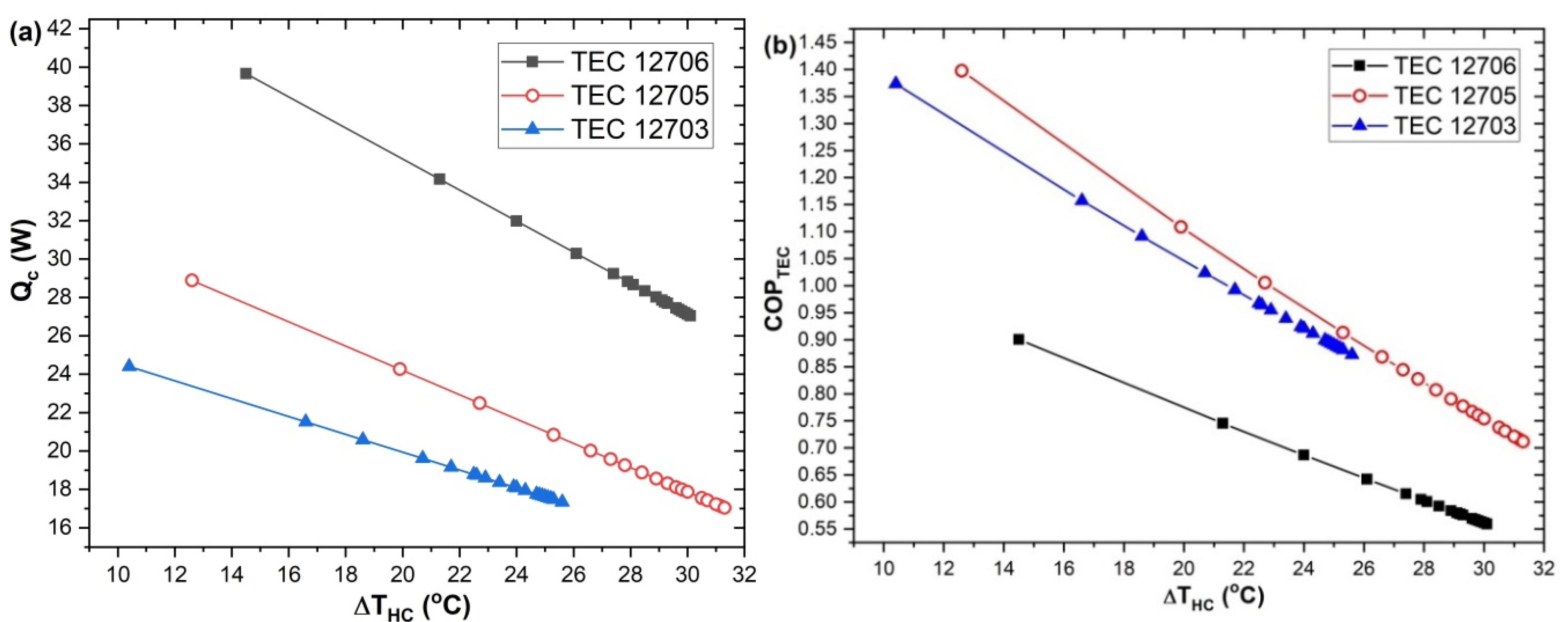

Figure 5 shows the cooling performance of the TEC1 - 12706, TEC1 - 12705 and TEC1 - 12703 modules at different temperature gradients between the hot and cold side of thermoelectric modules.

Under a much higher current absorbed from the power supply

It, TEC1 - 12706 offered an enhanced cooling capacity for the refrigeration system compared with TEC1 - 12705, presenting this way

QC values about 10 W higher (see

Figure 5a). Instead, the increased Joule power losses registered for TEC1 - 12706 generated a power consumption with about 24 W higher than for TEC1 - 12705, so his corresponding COP cooling parameter decreased with 27 % after 8 minutes of testing. Although TEC1 - 12703 presented the lowest cooling capacity, this module showed also the lowest power losses through Joule effect and the COP values were closer to the TEC1 - 12705 module (see

Figure 5b).

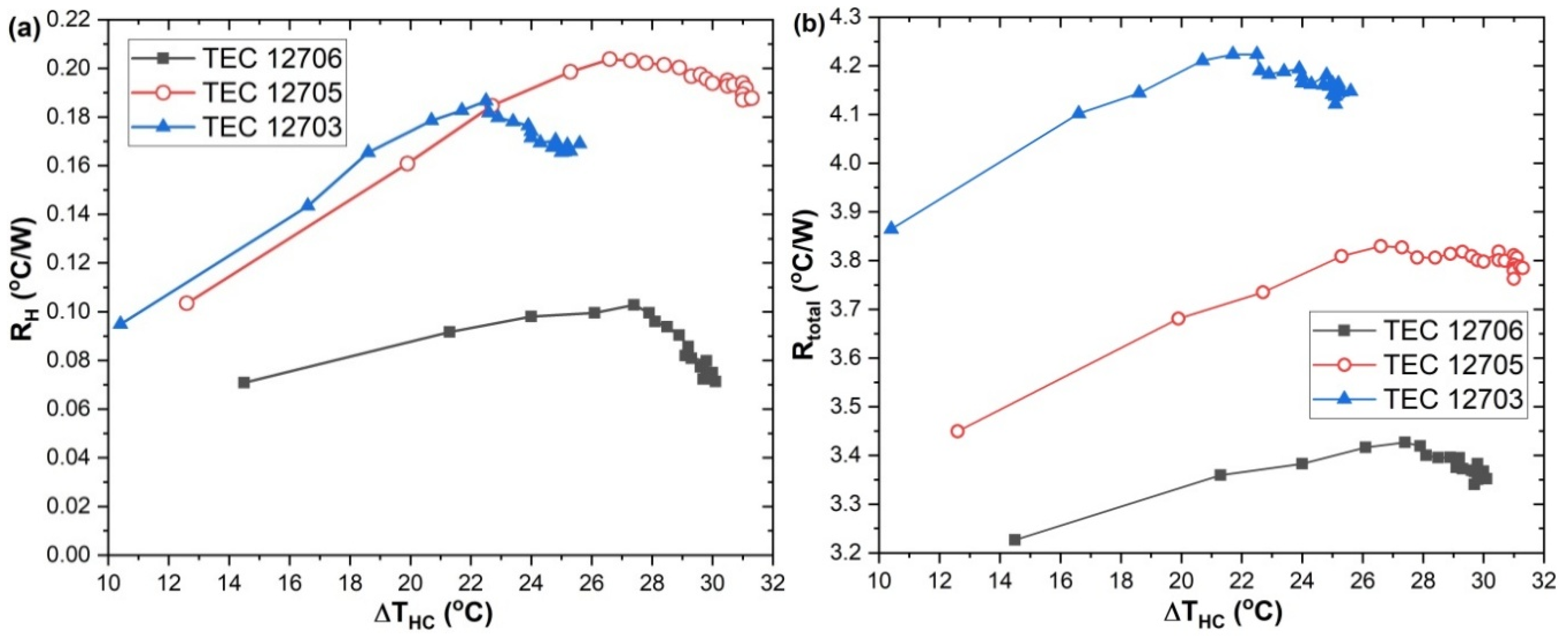

Figure 6 presents the variation of the thermal resistances inside the refrigeration system for the three different TEC modules.

Figure 6a revealed a proper performance of the heat sink under forced air convection, coupled with all the three TEC modules. Due to the high amount of heat transferred between the TEC1-12706 hot side and the heat sink, the R

H value was the lowest for this system configuration. For example, at

ΔTHC = 30°C, R

H was only 0.072 °C/W.

Chang Y. W. et al. [

31] showed that a thermoelectric air-cooling module presents a lower performance compared to a conventional heat sink without a TEC when the thermal resistance of the heat sink exceeds 0.385

oC/W.

As we can see in

Figure 6b, the total thermal resistance of the cooling system with TEC1 - 12706 presented the lowest values, under a lowest individual thermal resistance

RTEC and also the lowest heat sink thermal resistances at the hot and cold junction of TEC module.

The coefficient of performance (COP) of a complete cooling system, which includes both heat supply and heat dissipation subsystems, is influenced by temperature drop losses across the system thermal resistances [

32]. Consequently, the COP of the entire thermoelectric cooling unit should be lower than that of an individual TEC module operating under the same

ΔTHC conditions.

Under those circumstances, the exergy analysis became necessary to take into account all the losses and inefficiencies registered during the energy conversion process developed inside the refrigeration system.

The total entropy generation rate

Sgen inside the cooling system is directly correlated with the internal and external irreversibilities. Internal irreversibilities arise from Joule heating losses due to electrical resistance and heat conduction losses within the thermoelectric couples. External irreversibilities result from irreversible heat transfer between the TEC and the heat source’s hot junction and between the TEC cold junction and the heat sink reservoirs [

33].

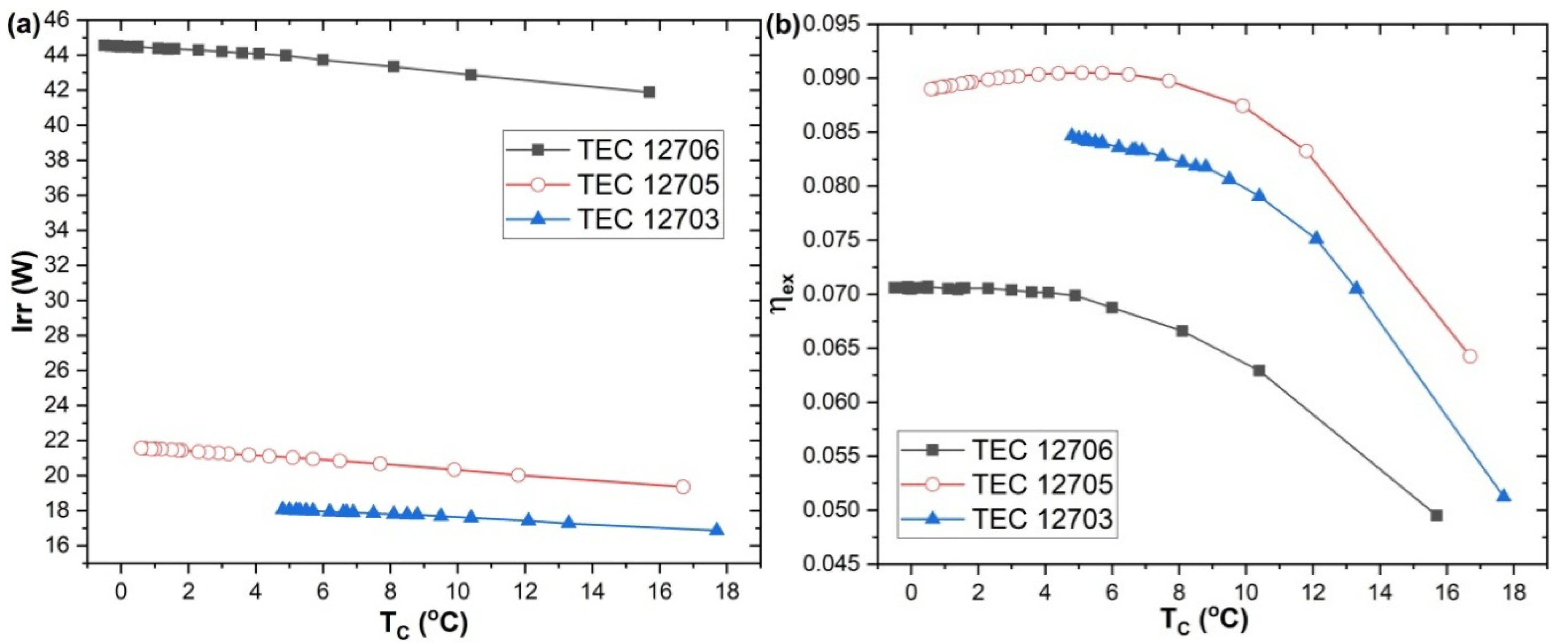

The required refrigeration temperature and a specific cooling capacity play crucial roles in determining the practical applications of thermoelectric cooling systems. Therefore, we present in

Figure 7 the variations in the thermoelectric module’s exergy efficiency (

ηex) and irreversibility (

Irr) measured at different cooling temperatures throughout the entire testing period.

During the air cooling test, TEC1- 12705 and TEC1 - 12706 exhibited similar values for

TC and

TH. However, the

QC value recorded for TEC 12706 was significantly higher, with the

QH value being 71% to 86% greater. As a result, the entropy generation rate (

Sgen) during the testing of TEC1 - 12706 was 0.076 W/K higher than that of TEC1 - 12705. Consequently, as illustrated in

Figure 7a, the irreversibility rate for TEC1 - 12706 was twice as high as that for TEC1 - 12705.

Equation (18) shows that a key factor affecting the exergy efficiency coefficient is the ratio of cooling efficiency to the power consumption of the TEC module. During testing, we found that the Q

C/P

t ratios for TEC1 - 12706, TEC1 - 12705, and TEC1 - 12703 were 0.71, 0.91, and 0.92, respectively. Consequently, the exergy efficiency of TEC 12705 was approximately 7.3% higher than that of TEC1 - 12706 at a temperature T

C = 5°C, as we could see from

Figure 7b.

Tipsaenporm et al. [

12] investigated a compact thermoelectric–based refrigeration system containing three TEC1–12708 modules and a rectangular fin heat sink under forced convection cooling. They observed a similar behaviour of system irreversibility, with a linear increase in value from approximately 38 W at an electric current supply of 2 A to 55 W at a current of 3 A. The maximum exergy efficiency achieved by their cooling system was 0.088 at Q

C = 28.6 W, which is almost identical to the values presented by TEC1-12705 during the cooling test with an air load at T

C values of 8–10 °C.

X. Li et al. [

34] reported also a similar range of exergy values for a thermoelectric cooler module type TEC1 – 12708 powered by a 12V supply voltage within a TEC–TEG system.

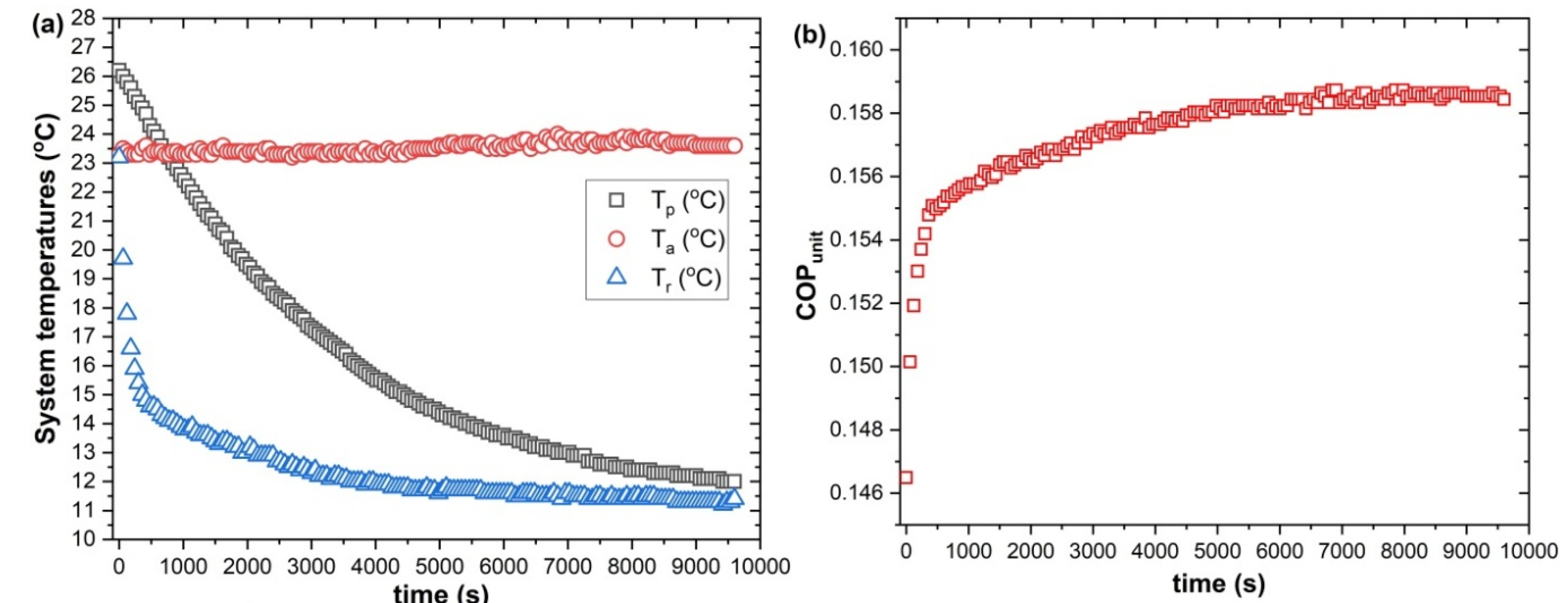

In the last part of this study, a water glass of 100 ml was considered as a cooling load for the refrigeration box. We could evaluated this way the coefficient of performance of the overall refrigeration system, containing the TEC module and external ventilation fan with optimal cooling behavior.

In

Figure 8a, we present the temperature variations of ambient air, refrigerated air, and water load inside the refrigeration box during a 160-minute cooling test. After 3000 seconds of testing, we observed a rapid decrease in the internal refrigeration temperature (

Tr) to 12.3 °C, corresponding to a water load temperature (

Tp) of 17.3 °C. This behaviour indicates that the internal pin-fin heat sink effectively cools the air.

Min and Rowe [

35] defined the

cooling-down period (CDP) of a refrigerator as the time required for the refrigeration temperature to drop from the surrounding ambient temperature (

Ta) to a value that is 20% above the system’s designated cooling set point. We set the cooling point at 12 °C for our current refrigerator configuration. As shown in

Figure 8a, the

CDP value was 660 seconds, consistent with the expected duration for the small refrigeration volume of the cooling box (0.00494 m

3).

M. Miramanto et al. [

36] investigated also a thermoelectric cooling system formed by TEC1 – 12706 module (P

TEC =38.08 W), a polyurethane cooler box with dimensions of 21.5 cm x 17.5 cm x 13 cm, an external heat sink - fan and inner heat sink, using a 380 ml bottle of water as the cooling load. Without an internal fan for the cooling air circulation, they reported a temperature gradient between the outer and inner cooler box

ΔTar = Ta – Tr of only 6

oC after 10.000 s of testing, half the value registered in our case under the same testing conditions. Using an identical cooler box, a TEC1 – 12710 module working at

PTEC = 42W, a fan – based inner heat sink with a vapor chamber plate for the cooling of external heat sink and 500 ml of water as the cooling load, A. Winarta et al. [

37] reported an improved cooling of the water load from 26

oC to 9

oC after 200 minutes of testing for a thermoelectric refrigeration system with vapor chamber heat sink.

Figure 8b shows that after only 6 minutes of testing, the refrigeration unit’s

COP attained a value of 0.155 and remained almost constant (2.5% maximum deviation) throughout the remaining testing time.

Gökçek and Şahin [

29] performed an experimental test of a thermoelectric refrigerator box with a water cooling system for the external heat sinks and a TEC1 – 12709 module working at

PTEC = 60W. They reported a

COP value of 0.23 after 25 minutes of testing, but after only 50 minutes of operation, the

COP decreased to 0.13.

6. Conclusions

After the refrigeration system investigation with three different thermoelectric modules (TEC1-1706, TEC1-12705 and TEC1-12703), thermal resistance network analysis revealed that the TEC1–12706 module presented the lowest total thermal resistance under the highest cooling capacity. Still, the refrigeration cooling box attained the highest TEC-type coefficient of performance with another thermoelectric module, TEC1–12705.

After conducting an exergy analysis, TEC1–12705 was selected as the optimum thermoelectric cooling device for further testing of the refrigeration box, as it presented the highest exergy efficiency. For this system configuration, we observed that the optimal cooling temperatures (TC) during the testing period ranged from 3.8°C to 6.5 °C. This temperature domain corresponds to maximum exergy efficiency values of 0.09 and irreversibility values ranging from 21.2 W to 20.8 W.

The water, used as the cooling load during the refrigeration box’s cooling performance study with TEC1-12705, attained the desired cooling temperature of 12 °C after 160 minutes of testing. The refrigeration unit’s coefficient of performance presented values between 0.155 and 0.159 throughout the testing period, indicating a stable and efficient operating mode at any intermediate cooling stage.

References

- Saber, H.H.; Hajiah, A.E.; Alshehri, S.A. Sustainable Self-Cooling Framework for Cooling Computer Chip Hotspots Using Thermoelectric Modules. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrain, D.; Martínez, A.; Rodríguez, A. , Improvement of a thermoelectric and vapour compression hybrid refrigerator. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 39, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Meng, F.; Sun, F. Effect of heat transfer on the performance of thermoelectric generator-driven thermoelectric refrigerator system. Cryogenics 2012, 52, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheepati, K.R.; Balal, N. Solar Powered Thermoelectric Air Conditioning for Temperature Control in Poultry Incubators. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaferani, H.; Sams, M.W.; Ghomashchi, R.; Chen, G. Thermoelectric coolers as thermal management systems for medical applications: Design, optimization, and advancement. Nano Energy 2021, 90, 106572–106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Shi, X.-L.; Zou, J.; Chen, Z.-G. Thermoelectrics for medical applications: Progress, challenges, and perspectives. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 437, 135268–135283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, N.; Dedow, K.; Nguy, L.; Sullivan, P.; Khoshnevis, S.; Diller, K.R. An On-Site Thermoelectric Cooling Device for Cryotherapy and Control of Skin Blood Flow. J Med Device 2015, 9, 445021–445026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkans, V.; Blums, J. Estimating the Impact of a Recuperative Approach on the Efficiency of Thermoelectric Cooling. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A. Advanced Engineering Thermodynzamics, 4th Ed. ed; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Dwivedi, V.K.; Pandit, S.N. Exergy analysis of single-stage and multi stage thermoelectric cooler. Int. J. Energy Res. 2013, 38, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, W.-W.; Ding, W.-T.; Yang, G.-B.; Liu, D.; Zhao, F.-Y. Entropy generation minimization of thermoelectric systems applied for electronic cooling: Parametric investigations and operation optimization. Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 186, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipsaenporm, W.; Rungsiyopas, M.; Lertsatitthanakor, C. Thermodynamic Analysis of a Compact Thermoelectric Air Conditioner. J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Fu, H.; Yu, J. Evaluating optimal cooling temperature of a single-stage thermoelectric cooler using thermodynamic second law. Applied Thermal Engineering 2017, 123, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, V. González de Peredo, Mercedes Vázquez-Espinosa, Estrella Espada-Bellido, Marta Ferreiro-González, Antonio Amores-Arrocha, Miguel Palma, Gerardo F. Barbero and Ana Jiménez-Cantizano, Alternative Ultrasound-Assisted Method for the Extraction of the Bioactive Compounds Present in Myrtle (Myrtus communis L.). Molecules 2019, 24, 882. [Google Scholar]

- Yerena-Prieto, B.J.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, M.; Vázquez-Espinosa, M.; González-de-Peredo, A.V.; García-Alvarado, M.Á.; Palma, M.; Rodríguez-Jimenes, G.d.C.; Barbero, G.F. Optimization of an Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Method Applied to the Extraction of Flavonoids from Moringa Leaves (Moringa oleífera Lam.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.S.; Suryawanshi, D.; Kumar, M.; Waghmare, R. Ultrasonic treatment: A cohort review on bioactive compounds, allergens and physico-chemical properties of food. Current Research in Food Science 2021, 4, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiwiguna, T.A. Method for thermoelectric cooler utilization using manufacturer’s technical information. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1941, 020002. [Google Scholar]

- Šumiga, d. Srpak, ž. Kondić, application of thermoelectric modules as renewable energy sources. tehnički glasnik 2018, 12, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahmargoi, M.; Rahbar, N.; Kargarsharifabad, H.; Sadati, S.E.; Asadi, A. , An Experimental Study on the Performance Evaluation and Thermodynamic Modeling of a Thermoelectric Cooler Combined with Two Heatsinks. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 20336–20347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Maleki, A. Performance Improvement of the LNG Regasification Process Based on Geothermal Energy Using a Thermoelectric Generator and Energy and Exergy Analyses. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online:. Available online: https://module-center.com/Administrator/files/UploadFile/TEC1-12703-English.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Available online:. Available online: https://module-center.com/Administrator/files/UploadFile/TEC1-12705-English.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Available online:. Available online: https://asset.re-in.de/add/160267/c1/-/en/000189115DS02/DA_TRU-Components-TEC1-12706 (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Palacios, R.; Arenas, A.; Pecharromán, R.R.; Pagola, F.L. Analytical procedure to obtain internal parameters from performance curves of commercial thermoelectric modules. Applied Thermal Engineering 2009, 29, 3501–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, J.C.; Cavalcanti, E.J.C.; Carvalho, M. Energy, Exergy, Entropy Generation Minimization, and Exergoenvironmental Analyses of Energy Systems-A Mini-Review. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 902071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, S.; Kaushik, S.C.; Anusuya, K. Thermodynamic modelling and analysis of thermoelectric cooling system. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Energy Efficient Technologies for Sustainability (ICEETS), Nagercoil, India; 2016; pp. 685–693. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, J.-N.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Ding, C.; Sui, G.-R.; Jia, H.-Z.; Gao, X.-M. An Enhanced Thermoelectric Collaborative Cooling System With Thermoelectric Generator Serving as a Supplementary Power Source. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2021, 68, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćehajić, N. Exergy Analysis of Thermal Power Plant for Three Different Loads. TECHNICAL JOURNAL 2023, 17, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçek, M.; Şahin, F. Experimental performance investigation of minichannel water cooled-thermoelectric refrigerator. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2017, 10, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teertstra, P.; Yovanovich, M.; Culham, J. Analytical forced convection modeling of plate fin heat sinks. J Electron Manuf 2000, 10, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.W.; Chang, C.C.; Ke, M.T.; Chen, S.L. Thermoelectric air-cooling module for electronic devices. Appl Therm Eng 2009, 29, 2731–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasil’ev, E.N. The Effect of Thermal Resistances on the Coefficient of Performance of a Thermoelectric Cooling System. Technical Physics 2021, 66, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, S.; Kaushik, S.C. Energy and exergy analysis of an annular thermoelectric cooler. Energy Conversion and Management 2015, 106, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Yu, D.; Rezaniakolaei, A. The Influence of Peltier Effect on the Exergy of Thermoelectric Cooler–Thermoelectric Generator System and Performance Improvement of System. Energy Technology 2023, 11, 2300136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, G.; Rowe, D.M. Experimental evaluation of prototype thermoelectric domestic-refrigerators. Applied Energy 2006, 83, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmanto, M.; Syahrul, S.; Wirdan, Y. Experimental performances of a thermoelectric cooler box with thermoelectric position variations. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2019, 22, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarta, A.; Rasta, I.M.; Suamir, I.N.; Puja, I.G.K. Experimental Study of Thermoelectric Cooler Box Using Heat Sink with Vapor Chamber as Hot Side Cooling Device. In Akhyar (eds) Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Experimental and Computational Mechanics in Engineering. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer, Singapore. 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).