1. Introduction

In this article we discuss ethnobotany and traditional practices of the Sakha people, an ethnically Turkic people living in northeastern Russia, whose home is in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Sakha territory extends across Arctic and Subarctic It has a strong continental climate with very low temperatures in the winter (-50C to -70C in places) and high summer temperatures (+30C or more).

Plants have occupied a central place in the life of the Sakha people since ancient times. Names are regularly given only to those plants that people use in some way, and names are generally based on some defining feature of the plant, be it appearance, habitat, or usage [

1] p. 188, as is common for Indigenous plant nomenclature [

2]. Plant nomenclature eflects the social, economic and cultural activities of the inhabitants of a particular region, their understanding of the world around them, and provides key information about how a group conceptualizes the physical world and their relations and engagement with it [

3], p. 43.

The first documentation of Sakha folk medicine dates to the 17th century. The records mention that in 1670 a servant Semyon Epishev was collecting herbs around the Yakutsk stockade. In his records he gives a detailed description of plants with local (Sakha) names and “advice” on their use [

4], pp. 235-236. In discussions of Sakha professional folk medicine, discussions of the medicinal uses and preparation of plants dominates [

5]; broader overviews of traditional folk medicine include [

6,

7,

8].

Approximately 75% of the territory of the Sakha Republic is taiga [

9], and almost the entire continental territory of Yakutia is a zone of continuous permafrost. There are some 2000 species of higher vascular plants, of which more than 230 species are medicinal (157 genera and 55 families) [

10]. The Indigenous peoples of the region use plants as a source of food, shelter, and used for medicinal purposes. They name the plants they use, and these names are created according to basic principles found elsewhere among Indigenous peoples, with naming practices based on a set of salient and culturally relevant characteristics, such as size, shape, color and habitat [

2]. In Sakha naming practices, the plant names do not usually indicate use; this is rather knowledge that is transferred from user to user but not encoded in the plant name itself. (This is in contrast to some other traditions, such as the English common name for

Euphrasia, ‘eye bright’, which indicates the plant’s use in treating eye infections.)

Plant-based medicines are widely used for the healing of virtually all vital organs and for normalizing basic physiological functions. The traditional methods and techniques of Sakha folk healing, many of which we have found in archival sources of the past centuries, are the most effective for treating various groups of diseases which are widespread among people living in the Far North. In the course of our research we have found that these traditional practices are maintained by modern healers, having been being passed on from generation to generation as a living experience of the people, as an element of their centuries-old culture [

11]. The plant names represent the Sakha worldview, their attitude to the environment, practical experience and system of values.

2. Materials and Methods

The findings presented here are based on research conducted in 2017-2023 in the territory of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Three basic methodologies were used in gathering data. First, interviews were collected with 2500 consultants about the identification of plants, collection methods, uses and beliefs. Consultants were first shown a photograph of a plant and asked to identify it. The images used to elicit plant names and descriptions are provided in this article (Figures 1 and 2, and 5–14). After a consultant identifies the plant, the interviewer proceeded with an open-format interview about that particular plant. The researcher adapted the questions depending on the respondent. This interview technique is based on community participatory research methods, enabling consultants to shape the research and provide information that they see as important, not just what the researcher is interested in, helping to eliminate research bias and to contribute community knowledge. Second, we conducted participant observation work, walking the land with consultants, identifying and collecting plants and preparing them for use. Third, researchers used purposive sampling to identify plant names and uses in published sources. Information about the consultants quoted in the present article is provided in Appendix

Table A1, where we provide their name, year of birth, district of residence, and profession. They are referred to in the text by their initials.

3. Results

Our research focuses on 10 plants with medicinal uses, provided in

Table 1. These plants were selected because our fieldwork demonstrated that they are known and actively used by modern Sakha herbalists, healers and shamans. The medicinal role of these plants in traditional Sakha healing is widely known among practitioners and continues to this day. We were able to cross-check uses and our interpretations of plant names in published sources. In this section we provide information about both uses and names: the naming practices provide insight into Sakha traditional beliefs and ways of life. Ethnobotanical nomenclature differs significantly from scientific nomenclature: folk names of medicinal plants are ambiguous, and the plant itself may have several common names, as seen in the examples of Achillea millefolium L., Polygonum aviculare L., and Dryopteris fragrans (L.) Schott. One and the same consultant sometimes provided more than one common name.

4. Discussion

Our fieldwork resulted in the list of plants found in

Table 1. We now discuss each of these plants, their uses, and what their Sakha names tell us about them, in detail.

4.1. Achillea millefolium L.

The Sakha common names for Achillea millefollum L. are

xaryja ot,

köbüör ot,

bytyryys ot, and

suorat ot; all have the second component

ot ‘grass’. The lexical unit

xaryja ‘spruce’ +

ot ‘grass’ literally translates as ‘spruce-grass’ (

Figure 1). The name is formed by metaphorical extension in terms of the plant’s appearance as an herbal bush: the first component

xaryja indexes the fact that yarrow resembles a spruce.

In the next name, the first component is

köbüör which is ‘raw butter, diluted with boiled milk or boiled water by whorling’ [

14], pp. 1891-1893. We assume that the name

köbüör is explained by the fact that the plant produces small white or pink flowers, which grow in tightly compacted clusters, which in turn form a common shield-shaped group of numerous clusters, are likened to whipped raw butter in appearance (

Figure 2). The name metaphorically indexes these inflorescences.

A similar example is presented in the name

suorat ot, which includes the name of a dairy product. (

Suorat is ‘sour milk’, a fermented boiled milk made from skimmed cow’s milk and constituting the main daily food of the Sakha people in summer; the name literally translates as ‘grass-like sour milk’. The formation of this name is also associated with the comparison of the shield-shaped inflorescence of numerous clusters of yarrow flowers. These clusters have some white flowers in each group, lending them the appearance of sour milk, a whitish liquid with a slightly yellowish tinge (

Figure 2). Sakha herbalists use yarrow herb for gastrointestinal diseases and as an antiseptic. The juice of yarrow leaves, mixed with black currant juice, is drunk to increase appetite [

10].

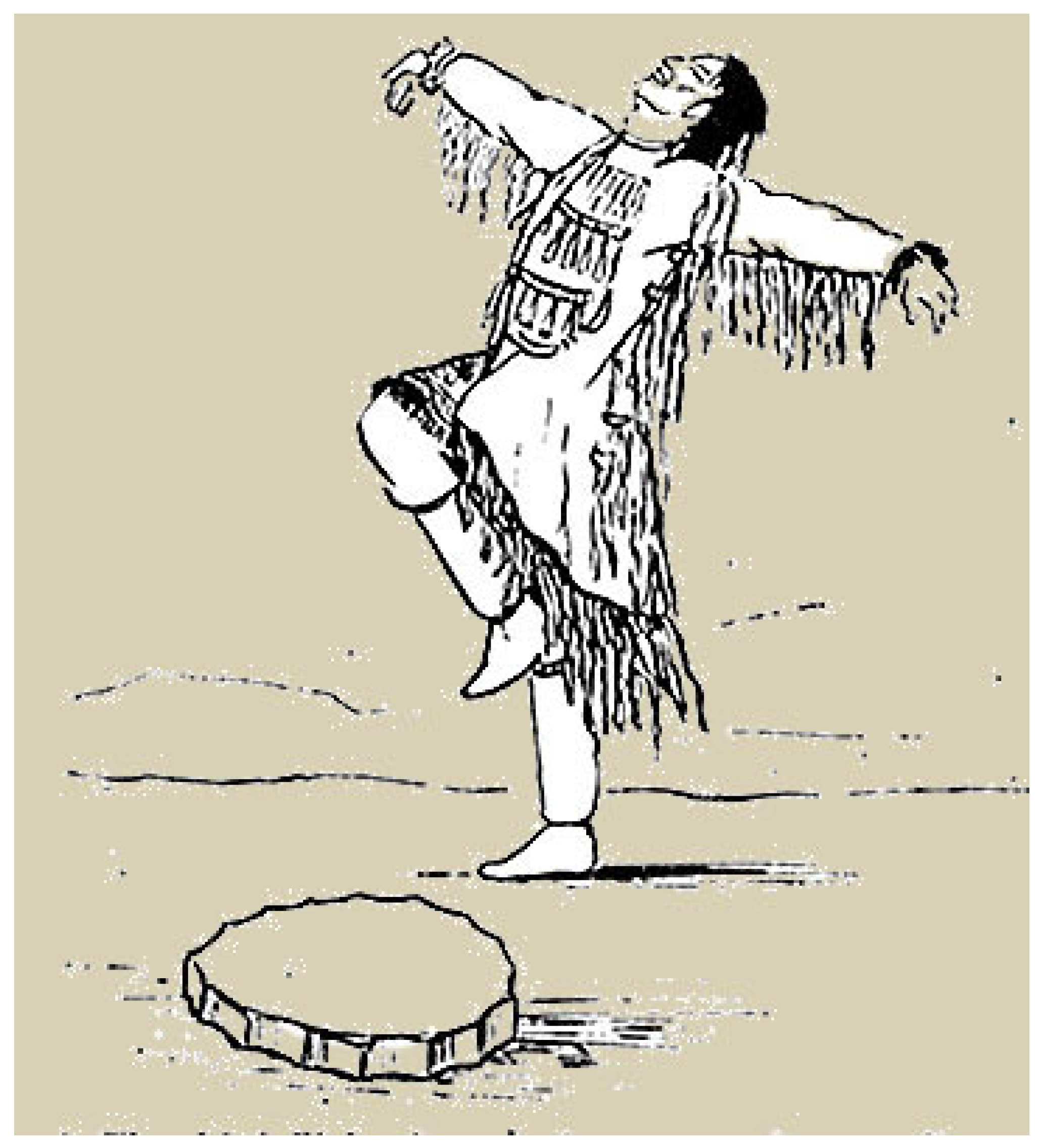

The third name,

bytyryys ot, is formed by metaphorical extension. The first component

bytyryys means ‘fringed tassels made of twisted threads, fabric or leather (for example, on a saddle cloth or on a shamanic costume); fringe (on the hem of a shaman’s costume)’ [

14], pp. 645-646. This can be understood as likening the yarrow leaves to the fringe on the hem of a shaman’s costume (

Figure 3).

Yarrow leaves are frilly, feather-like, tapering to a point, and similar to the shaman’s fringe (

Figure 4).

Thus, these compound names, taken together, comprise a comprehensive description of the individual morphological elements of the plant: inflorescences (köbüör ot), leaves (bytyryys ot) and herbal bush (xaryja ot).

4.2. Artemisia absinthium

The name of common wormwood in the Sakha language arose by singling out the functional attribute of a medicinal plant (

Figure 5).

The name

kya uga or

kya oto ‘common wormwood, edible herb’ consists of two components, in which the first component

kya indexes the use of wormwood for medicinal purposes. The word

kya is of common Turkic origin; in Sakha it denotes ‘blood coming out of internal organs (in women during childbirth, miscarriage, bloody diarrhea); menstrual blood’ [

14], p. 1351. Wormwood is considered a female plant that stimulates the uterus and regulates the menstrual cycle, as well as alleviating various gynecological ailments. The second component

uk (from

ug-a) means ‘stem’ [

14], p. 2988. In this way the Sakha common name comes from the fact that the plant is used to treat various kinds of bleeding is reflected in the name of a medicinal plant.

Common wormwood and other wormwood species are used under the name

üöre oto by Sakha phytotherapists in an infusion as a styptic, as well as to improve digestion, as a carminative, an appetite stimulant, and as a general tonic and stimulant. The infusion is used for anemia, depression and exhaustion, as a diaphoretic and anti-inflammatory agent for fever and pneumonia, colds, laryngitis, cystitis, urethritis, and as a diuretic, choleretic, anticancer and anthelmintic agent. Baths from the herb are recommended for gout and colds. An infusion of wormwood can be used externally to relieve stomatitis, for treating wounds and long non-healing ulcers, by applying the fresh herb itself, or a cloth soaked in fresh wormwood juice, to the affected area [

10]. An infusion of wormwood is recommended by the Sakha healers as a hemostatic, as well as a diuretic, and a choleretic agent (for cystitis and urethritis) [

17].

A second meaning of the base kya is ‘tinder, kindling’, that is, a thin long sliver of dry wood, intended for stoking a stove or lighting a room. Sakha healers use a splinter of wormwood to cauterize wounds: a compacted lump of crushed leaves is applied to the sore place and burnt, as a treatment for radiculitis, sciatica, rheumatism, and muscle strain.

The second name for common wormwood, üöre oto consists of two components; the first component üöre means ‘herb for stew’. In pre-revolutionary times, the young leaves of this plant served as a source of food for poor people: The leaves were first boiled in water, and then squeezed well to extract the water, cut into small pieces and boiled in buttermilk. It can also be prepared to make a nutritious and tasty fermented milk soup. First, buttermilk and yogurt are boiled, then diluted by one third with water, seasoned with flour at the rate of 2 tablespoons per liter of liquid and brought to a boil, while stirring continuously. Young, finely chopped wormwood leaves, scalded with boiling water, are added to the finished soup.

4.3. Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub

There are a number of regional variants for the Sakha name for Chamerion angustifolium (L.) Holub:

kuruŋ ot, kuruŋ oto and

kürüŋ ot (

Figure 6).

The first element,

kuruŋ, has three meanings in the dictionary: (1) dry, withered, dried up, dried out; 2) dry, dried up; 3) forest fire, a place with scorched forest, burned out place’ [

14], p. 1254. According to many elders, the Sakha ancestors used this plant in their daily activities: they dried the leaves and flowers to brew as as a hot drink or tea. That is, they specifically used the plant in dry form. A decoction of fireweed is used to treat headaches, metabolic disorders, dysbacteriosis, anemia, and gastric ulcer. It can also be used to normalize sleep, relieve anxiety, and to slow the growth of neoplasms. It is one of the few plants effective in the treatment of prostate adenoma (information supplied by consultants LVS and EPV). Note that [

15] gives the Latin name of the Sakha plant

kuruŋ ot as plant as Chamaerion (Rafin.).

4.4. Veronica incana L.

There are two Sakha names for the perennial herbaceous plant Veronica incana L.:

lohour oy and

oǧonɲor oto. The base

lohour can be translated as ‘well-ripened, poisonous, full (of fruit, grain, needles)’ plus

ot ‘grass") literally translates as ‘well-ripened grass’. It is is considered to be one of the oldest medicinal plants in Sakha traditions. Its flowers grow densely along the stem, tapering at the top of the stem like long brushes. The flowers grow out from the stem, resembling a wreath of ripened grasses. Thus the name

lohour ot describes the plant’s appearance (

Figure 7).

Silver speedwell is a popular remedy in Sakha traditional medicine. When taken as a decoction or infusion of the herb, it is used for various gastrointestinal diseases, hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, heartache, nervous agitation and liver diseases, as well as for pustular acne [

10].

The name oǧonɲor oto is formed by metaphorical extension. The first component, oǧonɲor ‘old man, elder’, represents a metaphorical perception and interpretation of silver speedwell as a ripe plant. Our consultant provided another interpretation, stating that oǧonɲor oto ‘herb of the elder’ got its name because it was widely used by the famous Sakha shaman and herbologist F.P. Chahkin (consultant: KPT).

4.5. Polygonum aviculare L.

In addition to its medicinal properties, Polygonum aviculare L. is also used as bird fodder by the Sakha people, and its name

čyyčaax oto translates as ‘bird grass’, from

čyyčaax ‘bird’ or ‘little bird’, also seen in the English common name

bird buckwheat (

Figure 8). The Russian

gorec ptičij is literally ‘bird mountaineer’.

The second name tiergen oto indexes the place where it grows: tiergen is a ‘yard, fence, cattle yard in summer, cattle pen, cattle drive’. This word is a borrowing from Mongolian (and is seen in modern Mongolian tirgen ‘village, settlement, place in the village where the cattle are kept’). And in fact bird buckwheat or knotweed grows on trampled fields, in yards, on paths, along roads, in clearings, permanent dry pastures, and in weedy places near dwellings.

The third name we collected,

kyabakka (and its variant

kyabaxa) has the two literal meanings ‘a part of the body (between the navel and the crotch)’ and ‘an ancient female metal garment worn in front below the navel at the top of the undergarment’ [

14], p. 1352. In this case, the name of the plant references the diseased organ. Polygonum aviculare L., or knotweed, has been used in folk and official medicine for several millennia. The herb is an effective treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases of the genital area, bleeding after childbirth, miscarriages caused by uterine fibroids, menopausal and juvenile hypermenorrhea, atony and hypotonia of the uterus to stimulate contractions. In addition, knotweed prevents the formation of urinary cacui and promotes their excretion in the case of kideny stones, it removes excess sodium and chlorine ions in the urine, and increases or enhances uterine contractions. It was used for infertility in the Middle Ages.

In traditional Sakha medicine, a decoction of the plant is taken for pneumonia and gastritis. Knotweed may be used for cholelithiasis and urolithiasis (from consultants RIG, YYN), for stomach ulcers, tuberculosis, liver and kidney diseases. A paste of fresh leaves is applied to purulent wounds (consultant: VEG). This plant is used for kidney diseases: for urolithiasis, pyelonephritis, and for treating wounds (consultants: KPX, KPT).

Modern medicine has confirmed that knotweed is effective for infertility. It stimulates the ovaries, relieves inflammation and promotes pregnancy. The medicinal plant is used in the treatment of a complex of diseases of the body and the body between the navel and perineum (in Sakha kyabaky). Thus, the plant name kyabaky reflects the medicinal properties by indicating the names of the organs for which the knotweed plant is used.

4.6. Gentiana decumbens L.

The gentian plant, a hardy species with trumpet-shaped deep blue flowers (

Figure 9), is popular for its medicinal properties, is called

čoroon ot in the Sakha language.

The first component

čoroon refers to the cup or serving vessel for drinking

kumys, fermented horse milk, traditional Sakha beverage (

Figure 10).

The dictionary defines it as ‘a wooden cylindrical dish for kumys, of different sizes, on one or three legs (decorated with carvings); a vessel that is a cup, jug, bowl, cup, glass; tall vessel with a tray’ [

14], p. 3650. Large-leaf gentian is used for diseases of the kidneys, liver and stomach, and a decoction of the herb also has an antipyretic effect (consultant: VEF).

4.7. Dryopteris fragrans (L.) Schott

Two of the Sakha names Dryopteris fragrans (L.) Schott–taas oto ‘fragrant woodfern, stonewort’ and xaja baggaǧa–provide information about where the plant grows. The word taas is ‘stone mountain’ and xaja has a broader meaning of ‘mountain, mountain range, mountain ridge, high mountain, cliff, rock, stone mountain’. Fragrant woodfern is an understudied medicinal plant. One of the most cold-tolerant ferns, it grows in the Arctic zone of Russia, as well as in the alpine and subalpine belts with a thick, short, brown, obliquely ascending rhizome, typical of the genus Dryopteris. In traditional Sakha medicine, the above-ground part of woodfern is used as an anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, antipyretic, for diarrhea, headaches, pulmonary tuberculosis (consultant: RIG).

The name

battax ot has a figurative meaning of ’grass-like hair’, stemming from the literal meaning of

battax: ‘cranial skin with vegetation, heads, pubes, head fur, cap of hair on the head’ [

14], p. 406. The name references the plant’s morphology, with grassy hair (

Figure 11).

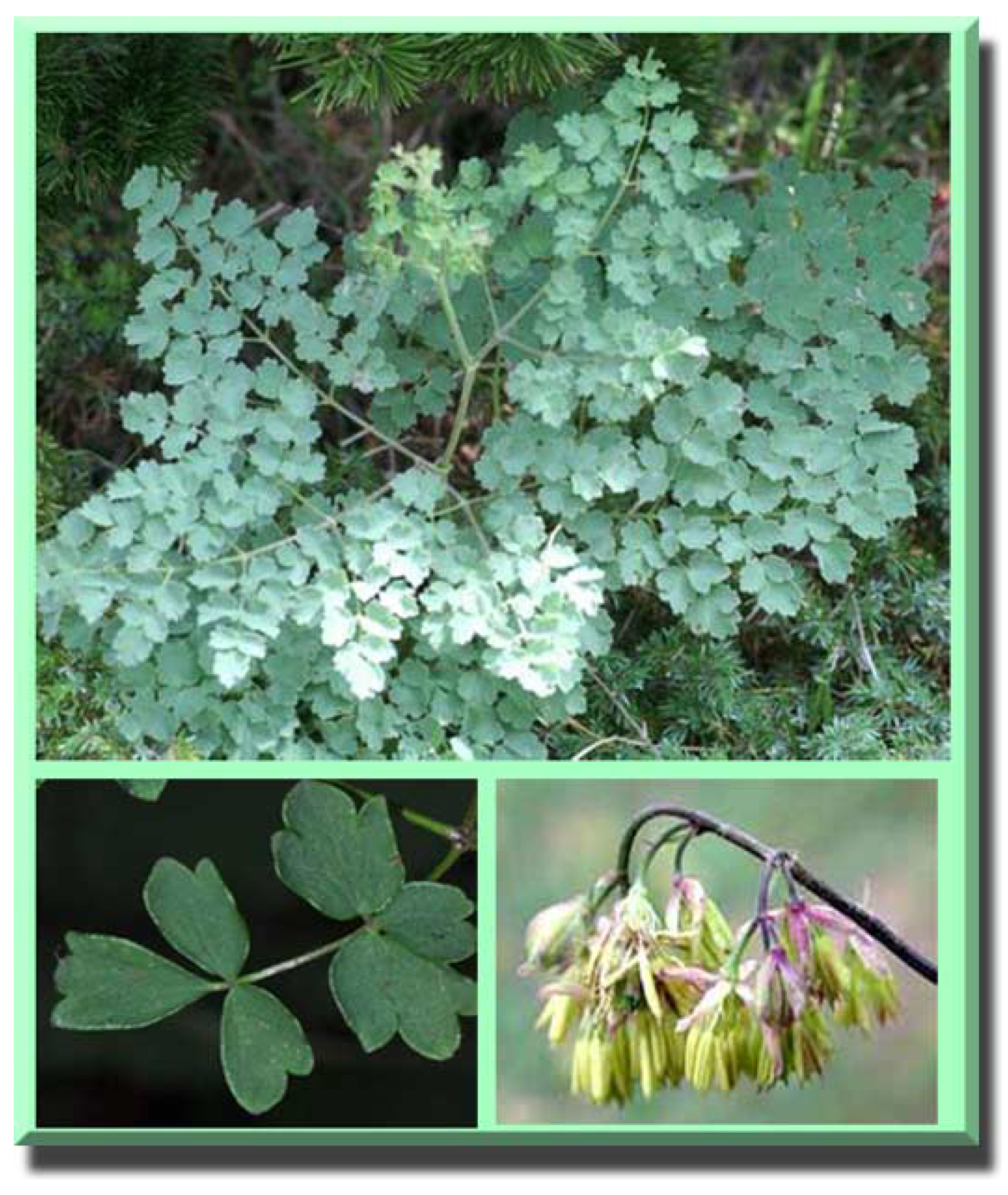

4.8. Thalictrum foetidum L.

There are two Sakha names for Thalictrum foetidum L.,

ürüje oto and

dZerekeen ot. As with the names in

Section 4.7, the first of these refers to the habitat where the plant can be found, and the second to the plant’s morphology. The first component

ürüje is a ‘brook, stream, rivulet, river, or tributary’, indicating a characteristic place of growth.

The alternate name indexes the plant’s appearance:

dZerekeen translates as ‘a variegated border, a cross-striped pattern, embroidery, in general frills of all kinds (striped, checkered) on anything, whatever its origin’ [

14], p. 812. With rounded-ovate, rounded or semi-heart-shaped, three-lobed drooping leaves, the wide-triangular leaves of stinking meadow-rue resemble a pattern based on the repetition and alternation of its rounded constituent elements (

Figure 12).

4.9. Bergenia crassifolia (L.) Fritsch

The Sakha name

čalygras denotes a perennial herbaceous plant of the Saxifragaceae family– the thick-leaved Bergenia crassifolia (

Figure 13).

The dictionary defines it as ‘the bergenia plant or monetnik, the decoction of which is used to treat venereal diseases and urinary retention’ [

14], p. 3564. The name comes from the onomatopoeic verb

čalygraa, ‘to make the sound of a small splash or a weak blow against dishes (said of water)’; ‘to make noise in the water, to speak so much and quickly that one cannot make it out’. It is an interesting name which makes reference to the resulting cure: a decoction of this plant remedies urinary retention and difficulty in urination. The verb is used to denote the sound of emptying the bladder, i.e., urination. So, the name

čalygras indicates the purpose of treatment.

Bergenia rhizomes and leaves are used in traditional medicine as an antiseptic for bladder diseases. An infusion of the leaves treats exacerbation of cystitis. The plant is also used as a strong astringent for gastrointestinal disorders and female diseases (consultants: VEF, KPT). Due to its anti-inflammatory and disinfecting effect, it has a positive effect on urinary retention.

4.10. Parnassia palustris L.

In traditional medicine, Parnassia palustris L. (

Figure 14), a perennial herb of the Celastraceae (birch) family is used to treat gynecological diseases, such as heavy periods, uterine prolapse, postpartum pain, and to facilitate postpartum separation of the placenta, eucorrhoea, sharp pain in the bladder, as well as for gonorrhea. A decoction of the above-ground part of of the bog star can be drunk as a diuretic for bladder pain. The plant was also used to treat veneral diseases, attested to by doctors V.N. Chepalov and P. M Bushkova, and our consultant VPA; see also [

11].

The Sakha noun

čemellide is formed from the noun

čemelli ‘chancre’ [

14], p. 3602. The term chancre refers to a purulent ulcer or disease of the genital organs, appearing independently or due to syphilis. Thus, the

čemellide reflects the therapeutic properties of the plant, by indexing the name of disease which it treats.

5. Conclusions

The study of plant naming practices enables us to reconstructs the world view of the Sakha speakers, and reveals the main parameters that characterize their material and spiritual culture. The compound plant names show that naming practices are based on a limited set of principles. We find names that index 1) the appearance and the form of any of their parts, which characterize individual morphological elements: inflorescences (köbüör ot, čoroon ot), leaves (bytyryys ot), herb bush (xaryjryya ot); external state (lohuor ot, battax ot, dyerekeen ot); 2) the plant’s habitat or characteristic place of growth (taas battaǧa, xaya battaǧa, taas oto, ürüeye oto); 3) the functional characteristic of a medicinal plant (kya uga, kya oto); 4) or an index of function (oǧonnyor oto, čyyčaax oto).

Our consultants are contemporary herbalists, healers, and shamans, who unquestionably have a clear idea of how to use these plants to help cure specific ailments. Our fieldwork demonstrates that the use of medicinal plants is part of a living tradition, not just a museum piece of knowledge. Taken holistically, the functional characteristics of these phytonyms, the contexts of their use, and additional extra-conceptual meanings testify to the fact that these names are important linguistic elements that build a picture of the Sakha worldview at a higher level, reflecting their spiritual world, values and social relationships.

No discussion of plants in Sakha traditional medicine would be complete without at least a mention of the important role that local plants played historically in the diet of the Sakha people. In the conditions of the Far Northern Arctic and Subarctic regions, the Indigenous populations experience an acute shortage of vitamins and biologically active substances, which can be replenished only by products of plant origin. Ethnographic studies show that the Sakha people used to eat about 50 different species of herbaceous plants. Of these, only onions and sorrel have survived in the regular diet of local people. The set of edible plants that were found in the Sakha diet largely coincides with those of other Turkic-speaking peoples of Siberia, suggesting that they brought these traditions with them when they migrated to Yakutia. Like other Turkic and Mongolian-speaking peoples of Siberia, they procured plants by gathering. For an overview of the cultural heritage of Sakha traditional foods and the role of plants, see [

18].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Grenoble, Malysheva, Turantaeva; methodology, Malysheva; investigation, Malysheva, Turantaeva; data curation, Malysheva; writing—original draft preparation, Grenoble, Malysheva, Turantaeva.; writing—review and editing, Grenoble, Malysheva, Turantaeva; supervision, Malysheva; project administration, Grenoble, Malysheva; funding acquisition, Grenoble, Malysheva. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Megagrant from the Government of the Russian Federation under Grant 075-15- 2021-616 for the project “Preservation of Linguistic and Cultural Diversity and Sustainable Development of the Arctic and Subarctic of the Russian Federation.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with practices of M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University, Yakutsk, Russia, and by Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago, Protocol 17-1362, approved 04.10.2017, approved with amendments on 22.07.2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request only due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Megagrant No. 075-15-2021-616 from the Government of the Russian Federation for the project “Preservation of Linguistic and Cultural Diversity and Sustainable Development of the Arctic and Subarctic of the Russian Federation.” We are also grateful for support from the M.K. Ammosov North-eastern Federal University in Yakutsk and from the University of Chicago.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Consultants

Table A1.

Consultants.

| Name |

Initials |

YOB |

Location |

Specialization |

| G.I. Atlasova |

GIA |

1953 |

Ust’-Aldan district |

healer |

| V.P. Alekseev |

VPA |

1961 |

Megino-Kangalassky district |

healer |

| O.P. Ambros’eva |

OPA |

1948 |

Megino-Kangalassky district |

herbalist |

| V.E. Fedorov |

VEF |

1954 |

Megino-Kangalassky district |

healer |

| V.E. Gerasimov |

VEG |

1955 |

Verxnesiljusy district |

healer |

| R.I. Gortseva |

RIG |

1932 |

Ojmjansky district |

herbalist |

| A.A. Jakovleva |

AAJ |

1951 |

Tattinsky district |

herbalist |

| N.I. Jakovleva |

NIJ |

1951 |

Amgin district |

herbalist |

| Y.Y. Nikolaeva |

YYN |

1954 |

Njurbinsky district |

healer |

| N.P. Sivcev |

NPS |

1953 |

Amgin district |

herbalist |

| L.V. Sleptsova |

LVS |

1952 |

Tattinsky district |

herbalist |

| K.P. Tokumova |

KPT |

1940 |

Tattinsky district |

healer |

| E.P. Vasilieva |

EPV |

1933 |

Amginsky district |

herbalist |

References

- Brodskij, I.V. Nazvanija rastenij v finno-ugorskix jazykax (na materiale pribaltijsko-finskix i komi jazykov.[Names of plans in Finno-Ugric languages (based on Pribaltic-finnic and the Komi languages]; Nauka: Moscow, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, B. Folk systematics in relation to biological classification and nomenclature. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1973, 4, 71–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, Z.I.; Xasanšina, G.V. Latinizirovannyj semantičeskij metajazyk agronomii kak sposob naučnoj konceptualizacii i kategorizacii fragmenta dejstvitel-nosti carstva rastenij [A Latinized semantic metalanguage of agronomy as a way of scientific conceptualization and categorization of a fragment of the reality of the plant kingdom]. In Problemy jazykovoj konceptualizacii i kategorizacii dejstvitel’nosti: materialy Vserossijskoj naučnoj konferencii “Jazyk. Sistema. Ličnost”’; Grindina, T. A., Ed.; Izd-vo Uralskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogičeskogo universiteta: Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2004; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Medved’, A.N. Bolezn’ i bol’nye v Drevnej Rusi: ot “rudometa” do “doxtura”. Vzgljad s posicij istoričeskoj antropologii. [Illness and the sick in Ancient Russia: from “ore-gun” to “doctor”. Historical anthropological view]; Izd-vo Oldga Abyško: St. Petersburg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, A.A. Rastitel’nye lečebnye sredstva jakutskoj narodnoj mediciny [Herbal remedies of Sakha folk medicine]; Jakutknigoizdat: Yakutsk, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, A.A. Narodnaja mudrost’: znanija i predstavlenija [Folk wisdom: knowledge and ideas.]; Jakutskoe knižnoe izdatel’stvo: Yakutsk, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gogolev, A.I. Narodnaja medicina [Folk medicine]. In Yakuty. Saxa. [The Yakuts. Sakha]; Romanova, E.N., Ed.; Nauka: Moscow, 2013; pp. 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Grigor’eva, A.M. O narodnoj medicine Jakutov) [Aboust Sakha folk medicine]; Jakutskoe knižnoe izdatel’stvo: Yakutsk, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, O.A.; Danilova, N.S. Konspekt flory sosudistyx rastenij prirodnoj territorii Jakutskogo botaničeskogo sada [Prospectus of the flora of Yakutia: Vascular plants]. Phytodiversity of Eastern Europe 2019, 1, 70–94. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, A.A. Lekarstvennye rastenija Jakutii i perspektivy ix osvoenija [Medicinal plants of Yakutia and prospects for their development]; Jakutknigoizdat: Novosibirsk, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grigor’eva, A.M. Narodnoe vračevanie v Yakutii (XVII–XX vv.) [Folk healing in Yakutia (XVII–XX centuries)]. Iz glubin: Moscow, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzneca, L.V. Lekarstvennye rastenija Jakutii. [Medicinal plants of Yakutia]. Bičik: Yakutsk, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, B.I. Ispol’zovanie lekarstvennyx rastenij Jakutii. [Use of medicinal plants of Yakutia]. Nauka: Novosibirsk, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pekarskij, È.K. . Slovar’ jakutskogo jazyka [Dictionary of the Sakha language], Vol. 1; AN SSSR: Leningrad, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, B.I. Dvudol’nye rastenija okrestnostej g. Jakutska. (Opredelitel’) [Dicotyledonous plants in the vicinity of Yakutsk (A guide)]; Jakutskij gosudarstvennyj universitet: Yakutsk, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Efimova, M.D. Aallaaxtyyna. Saxalyy emtenii [Sakha medicine]. Bičik: Yakutsk, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, A.A. Lekarstvennye rastenija [Medicinal plants], 4th ed.; Bičik: Yakutsk, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Borisova, I.Z.; Illarionov, V.V.; Illarionova, T.V. Cultural heritage in the food traditions of the Sakha people. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 2017, 9 (2S), 1388–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).