1. Introduction. Survey of selected review papers

The problem of controlling the supersonic/hypersonic flow produced by an aerodynamic (AD) body by the deposition of energy to the flow or various points on the surface of the streamlined body is currently a well-developed area of aerospace engineering. Numerous reviews devoted to various aspects of this topic include an analysis of research from the end of the last century to the present day. In the review papers of D. Knight et al. [1–3], the reviews are presented of research on the use of energy deposition for aerodynamic applications. In [1], D. Knight and N. Kianvashrad review the recent developments in three areas: SparkJets, drag reduction, and flow control. Particular attention is paid to studies related to the experimental formation of the unique SparkJet and multi-electrode SparkJet and their impact on the flow structure including the boundary layer (BL) and shock waves (SWs).

In [2,3], D. Knight presented surveys of research of experiments and simulation of using microwave (MW) and laser discharges for supersonic flow control and on aerodynamic drag reduction at high speeds. A classification of MW discharges, physical features of laser discharges, methods for producing MW and laser discharges, as well as the parameters of these discharges are analyzed. Experimental and numerical results on the reduction of wave drag with the use of MW and laser discharges are analyzed. The different types of energy deposition are considered, energy deposition in a uniform supersonic flow and energy deposition upstream of an AD body. The conditions for the formation of SWs and recirculation regions are analyzed along with the capability of the drag reduction. It is important that the reviews [1–3] include the indication of the parameters of experiments and calculations, as well as the comparison of the results examined in terms of individual characteristic parameters.

An extensive overview of wave drag reduction methods is presented by S. Rashid et al. in [4]. Flow control device for drag reduction in the areas of aerodynamics and flight mechanics including passive flow control, hybrid flow control and active flow control are analyzed. The results of the author’s analysis are presented in the convenient form of tables. Last two parts include the review of studies on energy deposition for wave drag reduction. Energy deposition methods considered include basic principles, the summary of previous studies on energy deposition, factors affecting energy deposition devices and a survey of related literature on energy deposition. The authors concluded that the energy deposition technique is more beneficial from the point of view of the robustness of operation over the passive methods, such as spike or air jets. The energy input can be continuous or pulsed and may be organized by laser or afterglow laser-plasma. The authors underlined that pulsed lasers have to be controlled by many parameters but this technique gives better results even at high angles of attack.

A review of approaches of energy deposition using different kinds of gas discharges, such as surface barrier discharges, pulsed spark discharges, and optical discharges for plasma aerodynamic applications is presented by A. Starikovskiy and N. Aleksandrov in [5]. The discharges considered are characterized by producing ultrafast (on the nanosecond time scale for atmospheric pressure) local gas heating. Studies of such type of plasma effects that facilitate or impede plasma-assisted control of the gas flow are analyzed from the point of view of the physical mechanisms of interaction of various types of discharges with gas flows. The mechanisms of ultrafast heating of air along with the processes that determine the decay of a strongly nonequilibrium discharge plasma, are considered. The researches on control of the configuration of SWs in front of an AD body and its trajectory, quasi-steady separated flows and layers, separation of the BL, dynamic of flow separation, and the use of plasma for other applications, such as the deicing of an AD body are considered.

The works on studies of bow shock wave (BSW) control devices for the reduction of drag, aero-heating and their practical implementation are considered by M. Ahmed and N. Qin in [6] along with the physics-based mechanisms of the action of these devices. Studies concerning passive flow control, such as mechanical spikes and active flow control, i.e. fluidic devices, counterflow (opposing) jets and opposing plasma jets (or SparkJets) along with energetic (thermal) devices, end energy deposition devices, and hybrid devices included the coupling passive and active flow control devices are considered. The authors analyzed principle of operation of such kind devices, practical implementation, factors controlling the effectiveness of these devices, flow unsteadiness associated with them, non-conventional studies and prospective gaps in investigation of these devices. Besides, the authors present survey on key studies on energy deposition devices and the prospective gaps in the field of energy deposition devices which is interesting in the framework of recent review. The authors consider the existing practical applications for forebody shock control devices, give numerous examples of the use of discharge plasma to control high-speed flows, and list the available real hypersonic vehicles that already implement these devices. The Appendix of this review paper contains tables that present in a convenient compact form the summaries of the previous studies on mechanical spike devices, fluidic (opposing jet) devices, energy deposition devices, and hybrid spike-fluid devices.

The historical review on the idea of flow control by energy deposition to the supersonic flow past AD body, which appeared in the last century and was developed in this century, is presented by V. Fomin et al. in [7]. In [8], P. Bletzinger et al. present an overview of research in the former Soviet Union and in the USA on the interaction of plasma with high speed flows and shock waves. The authors note that as early as the 1980s, there were reports of modifications of traveling SWs in weakly ionized gases. The energy deposition into a high-speed flow leads to modifications of the flow due to a decrease in the Mach number in the plasma region. A critical question in many studies has been what effect plasma factors have on this process. This literature is analyzed and illustrated with representative examples. It is shown that heating in many cases has a global character; however, individual localized ionization and thermal effects are also of interest for high-velocity flow control. The authors emphasize that the effectiveness of plasma methods for flow control and drag reduction is quite high, which justifies further research in order to optimize the control of aerodynamic processes due to the energy deposition to the flow. In a review [9], J. Shang et al. considered the studies on mechanisms of plasma actuators (PAs) for hypersonic flow control. The review includes different plasma models, including the analysis of governing equations for investigation of the magneto–aerodynamic interaction, electro–aerodynamic interaction, and separated flow control. The example is shown when the separated flow region is completely suppressed in the numerical simulation at a Mach number of 14 (see [10] by G. Updike).

H. Zong et al. present the review paper [11] considered plasma synthetic jet actuators (or SparkJets, or plasma jets) for active flow control. The paper provides an observation of plasma jet actuator systems, including working principles of them, power supply systems, and the construction of actuators. The authors examined experimental and numerical studies, considering parameters of jet formation and intensity metric along with time evolutions of jet exit velocity and cavity pressure. Theoretical models of energy deposition are considered from the point of view of energy efficiency, and the examples are given of flow control applications. The article highlights that current studies on the application of an array of actuators have shown a reduction in flow separation, as well as mitigation of low-frequency instability associated with the separated flow.

R. Males in [12] and M. Shneider et al. in [13] conduct the analysis of studies in flow control by energy addition into high-speed air, in particular, from the point of view of generation of virtual shapes in supersonic flows. In [12], Males discuses laser and microwave energy deposition for drag reduction, steering and related applications, and the use of electron beams for magneto-hydrodynamic (MHD) applications, as well as the addition of acoustic energy into a BL. In [13] the authors present a short selective review of theoretical and experimental studies conducted by this group related to high-speed aerodynamic applications of energy injection for drag reduction, geometry control, steering and sonic boom mitigation. A common feature of all these substantially different processes is the creating of virtual shock-vortex shapes, forming a new structure of the flow. The authors examine flow virtual shapes which are created by MW plasma heating, magnetohydrodynamic impacts, the use of electron beams, and localized plasma-assisted surface combustion. The studies of aerodynamic forces generated by off-axis heat addition upstream of an AD body are also considered.

In [14], A. Russel et al. present the review covered the fundamental characteristics of the methods of flow control based on Joule heating as well as the experience of their applications in controlling high-speed flows. The review includes the parts concerning analyzing the studies on nanosecond pulse dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasmas, localized arc filament plasma actuators, pulsed plasma synthetic jets, laser and MW generated plasma including numerical modelling, as well as energy deposition methods for shock wave – boundary layer interaction (SWBLI) and BL separation control in high speed intakes. The authors underlined that in supersonic/hypersonic flows the methods of mechanical control can be problematic because they require energy for moving and do not have fast enough response time. Meanwhile, devices for energy deposition for flow control have no moving parts and their response times can be nanoseconds. The review involves the consideration of fundamental physics of the operation of such methods along with the experience of their applications in high-speed flows.

In review papers [15,16] of the S. Leonov’s group, surveys of experimental methods of flow control, including surface PAs, laser energy deposition, and the impact of plasma generated by MW impulses are presented. In [15], the attention is paid to studies of the effect of near-surface discharge on structure and parameters of supersonic airflow, the mechanism of lateral jets generation, including the researches of the optimization of the discharge localization in a mixing layer of two gases. In [16], the authors present the review of studies on the dynamics of formation of near-surface electric discharges and on the mechanisms of their interaction with the airflow. The questions of the dynamics of surface barrier discharges (SDBD) in quiescent air, flow perturbations generated by SDBD plasma including kinetic modeling of SDBD plasmas, as long as the dynamics of DC SDBD in airflow including the effect of plasma-induced flow separation on a plane wall are examined with the numerous illustrations reprinted from the considered works.

The studies on the flow perturbations generated by SDBD plasma include the effects of low-speed near-wall jets and vortices and the compression waves production accompanied by the following thermal perturbations [16]. The studies of the time scales of the development of various discharges and thermal perturbations in nanosecond pulse discharges and afterglow are also considered, which provides the necessary information for modeling the discharge experiments. The figures are presented of the formation of the stratified plasma medium in the case of quasi-DC (Q-DC) discharge plasma in M = 2 airflow. Within the framework of this review, the most interesting are the parts that deal with the review of studies on the transition from uniform to filamentary plasma and the review of the filamentary (constricted) mode of SDBD plasmas which has the shape of the stratified plasma medium. The authors underlined that for filamentary discharge mode, modeling predictions were basically non-existent.

J. Kriegseis et al. present a review on studies on DBD-based boundary-layer control in aerodynamic applications [17]. The electrical and physical characteristics of PAs are considered along with the modes of the PAs operating. The authors consider the structure of PAs, including their geometry and materials, schemes of their action, intensity and power consumption. The numerical results of solving the vorticity equation in the area of the actuator action are analyzed. In the subsections the authors examine the studies on BL stabilization, including the using of vortex generators, active wave cancelation, and the discharge-based control of turbulent BL.

In the review article [18], I. Znamenskaya presents an overview of modern methods for recording, processing and analyzing dynamic processes. The author of the review considers both the physical foundations of flow visualization and the foundations of modern technologies for digital processing of flow images. The review contains an analysis of modern methods of flow visualization. Particular attention is paid to methods using cross-correlation image processing algorithms. The actual problem of using big data in the analysis of the results of panoramic experiments is considered. Examples of the use of machine learning in the analysis of large shadow data sets are given.

The present review paper provides an overview which focuses on the use of spatially multi-component (complex) plasma structures and combined energy deposition for high-speed flow control. In the review, spatially multi-component plasma structures are understood as strongly inhomogeneous plasma formations generated by an energy source of some type or resulting from the mutual action of several energy sources of different types. Such structures are the result of a “nonlinear superposition” of the action of the individual components, cause new physical properties of the impact of this complex plasma structures on a high-speed flow. Despite existence of many reviews devoted to active flow control with the help of energy deposition, there has not yet been a separate review that includes consideration of the specific effects of spatially multi-component (complex) plasma structures on the flow. The purpose of this review is to fill this gap in the review literature in the scientific area of energy deposition for controlling the supersonic and hypersonic flows. The review considers the use of spatially multi-component plasma structures for influencing a single SW, as well as the BSW, the structure of a high-speed flows including control of SW – BL interaction (SWBLI) and control of AD characteristics of streamlined bodies.

2. Brief background

The direction of flow/flight control with the use of high-speed heating of local areas of the supersonic/hypersonic gas flows began to develop rapidly in the second half of the last century (see [19] by D. Knight). Historical aspects of the development of these areas and their use for flow/flight control are given by V. Fomin et al. in [7] and P. Bletzinger et al. in [8]. At present, research on the control of high-speed flows around AD bodies by means of the formation of plasma regions in the flow and on the surfaces of an AD body occupies one of the leading places in aerospace engineering (see the Reviews collected in Introduction). ESs used for these purposes can be MW (e.g. R. Miles et al. [20] and Yu. Kolesnichenko et al. [21,22]), laser (L. Myrabo, Y. Raizer [23], P. Tretyakov et al. [24]), discharge (V. Bityurin et al. [25], D. Roupassov et al. [26]), plasma jets (or SparkJets, H. Zong et al. [11]), magnetohydrodynamic (MHD, V. Bityurin et al. [27], T. Lapushkina et al. [28,29]). The features of plasma structures obtained using these sources and their effect on supersonic/hypersonic flow will be described below.

Theoretically, the possibility of controlling the structure of high-speed flows in problems of supersonic aerodynamics is substantiated by P. Georgievsky and V. Levin [30], I. Nemchinov et al. [31,32], D. Riggins et al. [33]. The separation zones of the flow were studied in the case of a supersonic flow past a blunt body with an external energy sources (ES). The effectiveness of the use of oblong sources - “thermal spikes” was shown in [30,31]. Essential drag reduction using focused energy release was also shown in [33]. The formation of a reciprocating circulation flow, which causes a change in pressure on the surface of a streamlined body, was also obtained in V. Artem’ev et al. [32]. Self-sustained flow pulsations in the flow past pointed and blunt bodies, initiated by an extended ESs, were obtained and studied by Georgievsky and Levin in [34] and by O. Azarova et al. in [35,36]. The high-speed flow past an ES was considered by K. Krasnobaev and R. Syunyaev in [37] and by K. Krasnobaev in [38]. It was shown that, due to heating, the flow near the source becomes subsonic, and the gas density may decrease by more than an order [37]. It was established that the BSW is formed in the flow at a sufficiently large energy release, and a quantitative analogy was obtained between the supersonic flow past thin bodies and ESs [38].

In [39,40], O. Azarova and D. Knight carried out the optimization of the shape and parameters of the regions of “heat spots” resulting from the deposition of MW and laser energy in the supersonic flows over combined cylindrical bodies on the basis of the comparison with experimental data. Approaches to reduce the drag force for the considered MW and laser experiments were proposed, and estimates of the amount of energy required to produce regions of heated gas with the obtained parameters are given. A 3D gas dynamics code was created and described by D. Knight et al. in [41] for modeling the interaction of MW-generated plasma with supersonic flow over a blunt body. In this case, the thermochemical model contained the description of the 23 types of species and included 238 reactions. The dynamics of the kinetics of the species in the MW-plasma is discussed and significant non-equilibrium effects were observed throughout the interaction.

In the calculations [21] by Yu. Kolesnichenko et al., the vortex structure in the shock layer region formed under the action of a longitudinal ES (filament) was obtained, and a vortex mechanism of influencing the AD body was proposed, resulting to the frontal drag force decrease. In [42] by O. Azarova, the formation of the vortex was obtained as a result of the Richtmyer-Meshkov instability (RMI) manifestation. In [43,44], O. Azarova and L. Gvozdeva for various gas media, showed the possibility of controlling three-shock configurations resulting from the interaction of the BSW with a longitudinal heated filament during the precursor growth. A complex structure of the vortex generated by the RMI was established that arises when an ES interacts with a shock layer, consisting of two twisted shear layers and a set of reflected compression-rarefaction waves between them [43].

A separate direction is connected with the control of the interaction of SW/BSW with a boundary layer (SWBLI). BL separation is a frequently present phenomenon in the supersonic and hypersonic flows past AD bodies. It can have a negative effect on the AD characteristics of the body. The objectives of SWBLI control are to reduce the separation zone caused by a pressure growth and to suppress the instabilities associated with the flow separation (see [45] by H. Babinsky, J. Harvey). The use of plasma structures initiated by sets of actuators to implement SWBLI control will also be discussed below.

3. Filamentary plasma: control of BSWESI and SWBLI

The problem of the interaction of SW/BSW with inhomogeneous plasma structures (filamentary plasma) is an integral part of research on the supersonic/hypersonic flow control, since this process directly affects the aerodynamic characteristics of a flying object ([1] by D. Knight). The studies usually include research of the interaction of such ESs with the SW/BSW (SWESI/ BSWESI), as well as their effect on the process of SWBLI. Inhomogeneous plasma can be initiated by energy release using various tools, such as: arc plasma energy deposition (array of surface arc PAs), air glow gas discharge of constant voltage, a set of high-frequency, counter-flow plasma synthetic jet actuators (CPSJAs), a set of pulsed discharges of a high-power density and long pulse width, NS-DBD burst PAs, pulsed spark discharge PAs, localized multiple MW discharge in air, MW radiation produced through a filamentation of ultrashort high-intensity laser pulses in the atmosphere and so on. Impact results are usually associated with a change in the shape/position of the SW/BSW and blurring/weakening/disappearance of SW/BSW (resulting in the reduction of the drag force); changing the topology of a flow in a separation area (FSA) (resulting in the changing the lift forces). One of the promising areas is the study of gasdynamic instabilities in the processes under consideration, such as Richtmyer-Meshkov instability and Kelvin-Helmholtz instability (KHI), and production of vorticity in the flow acting the defined flow/flight characteristics. All these directions determine the choice of articles included in this section.

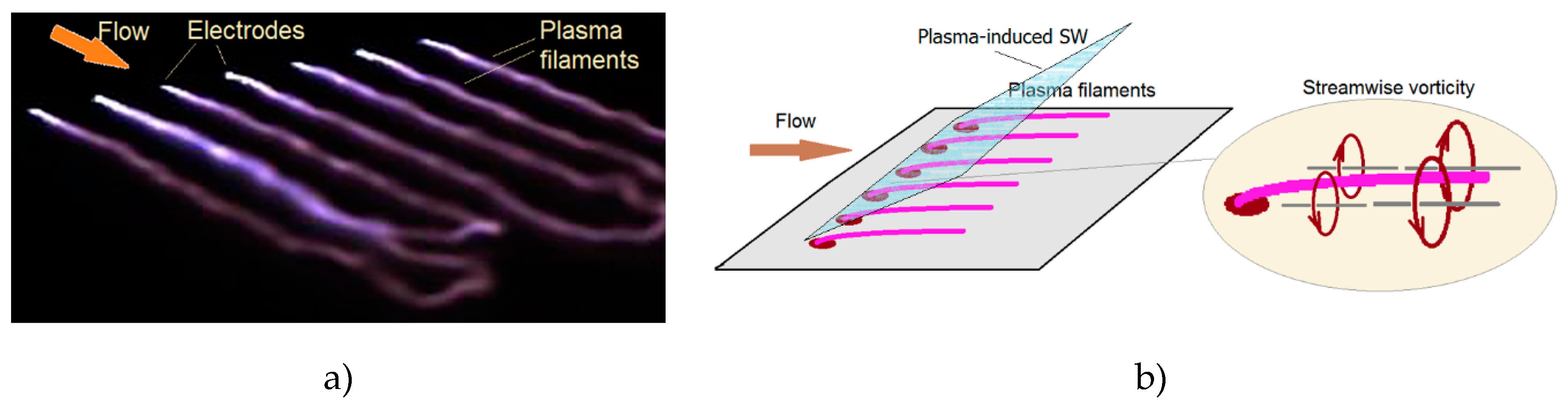

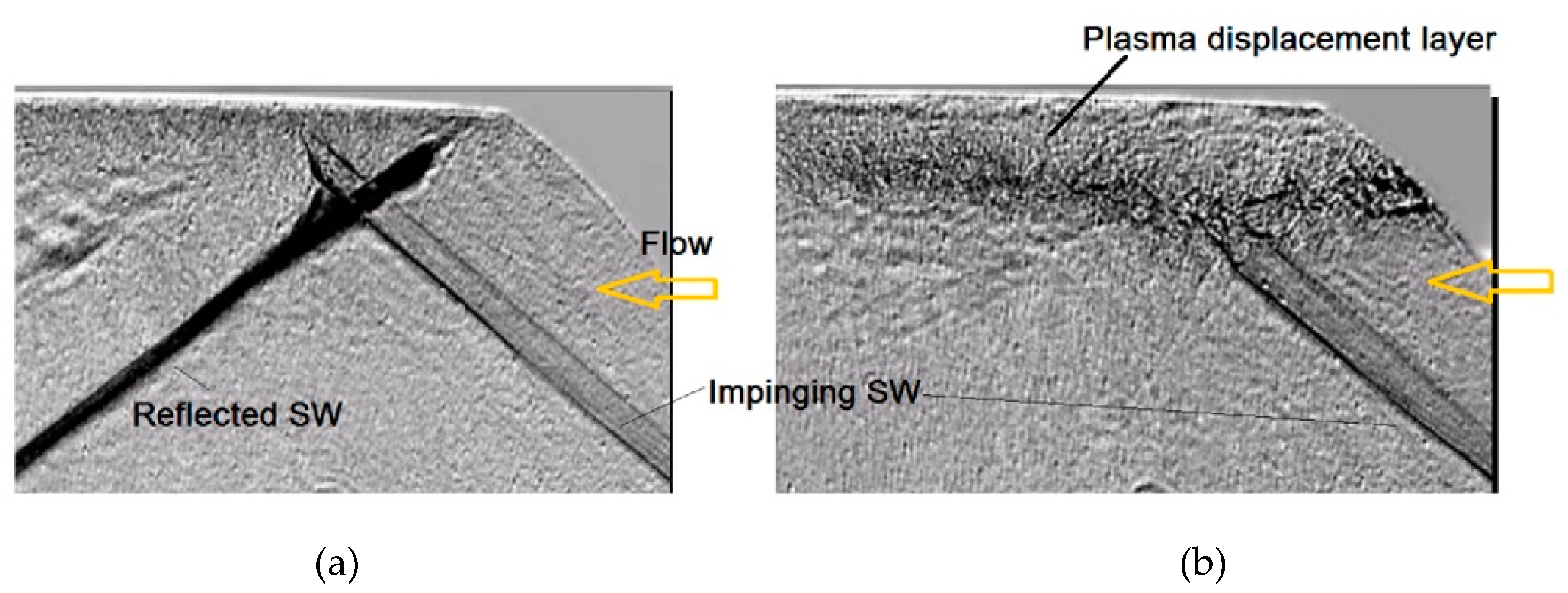

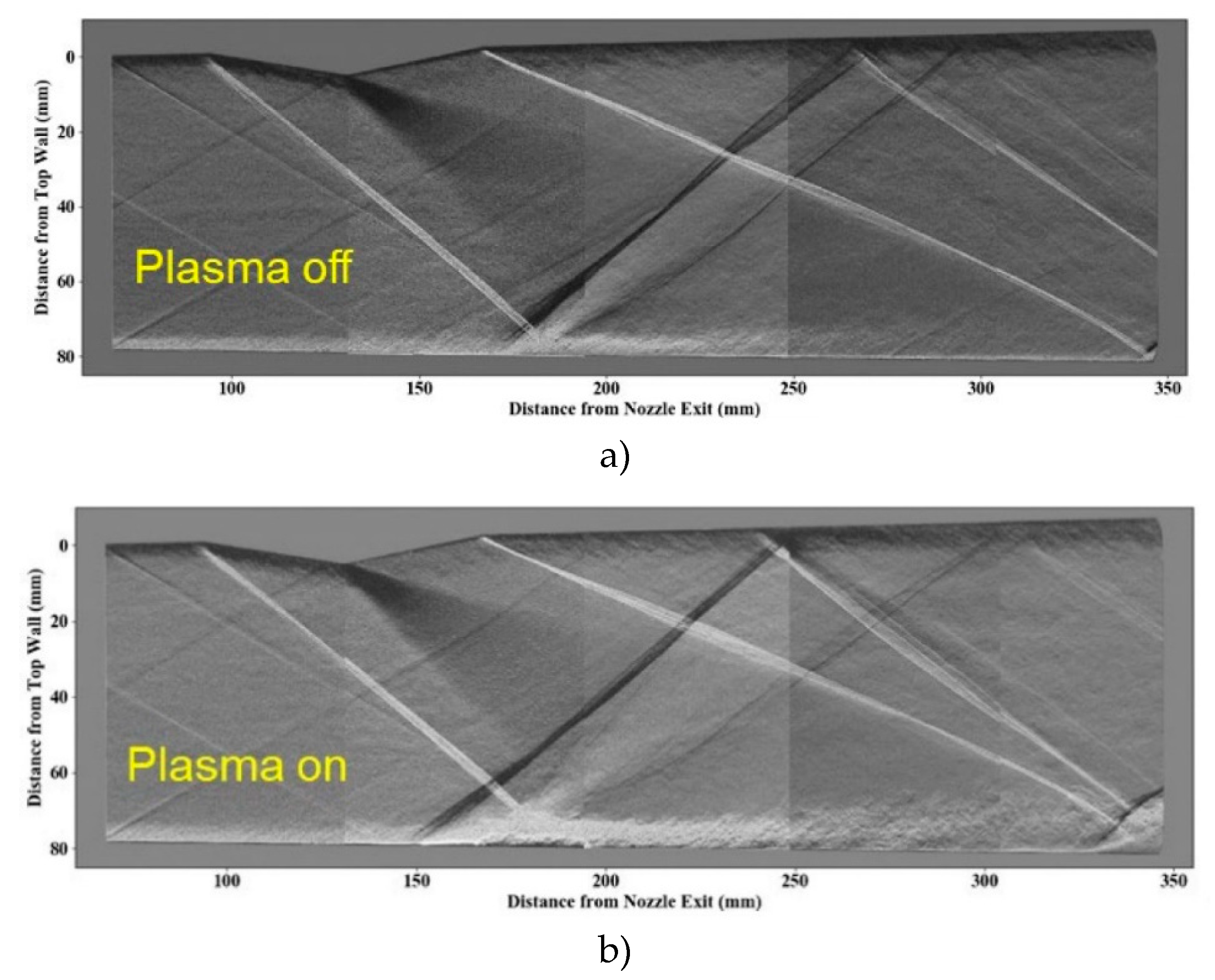

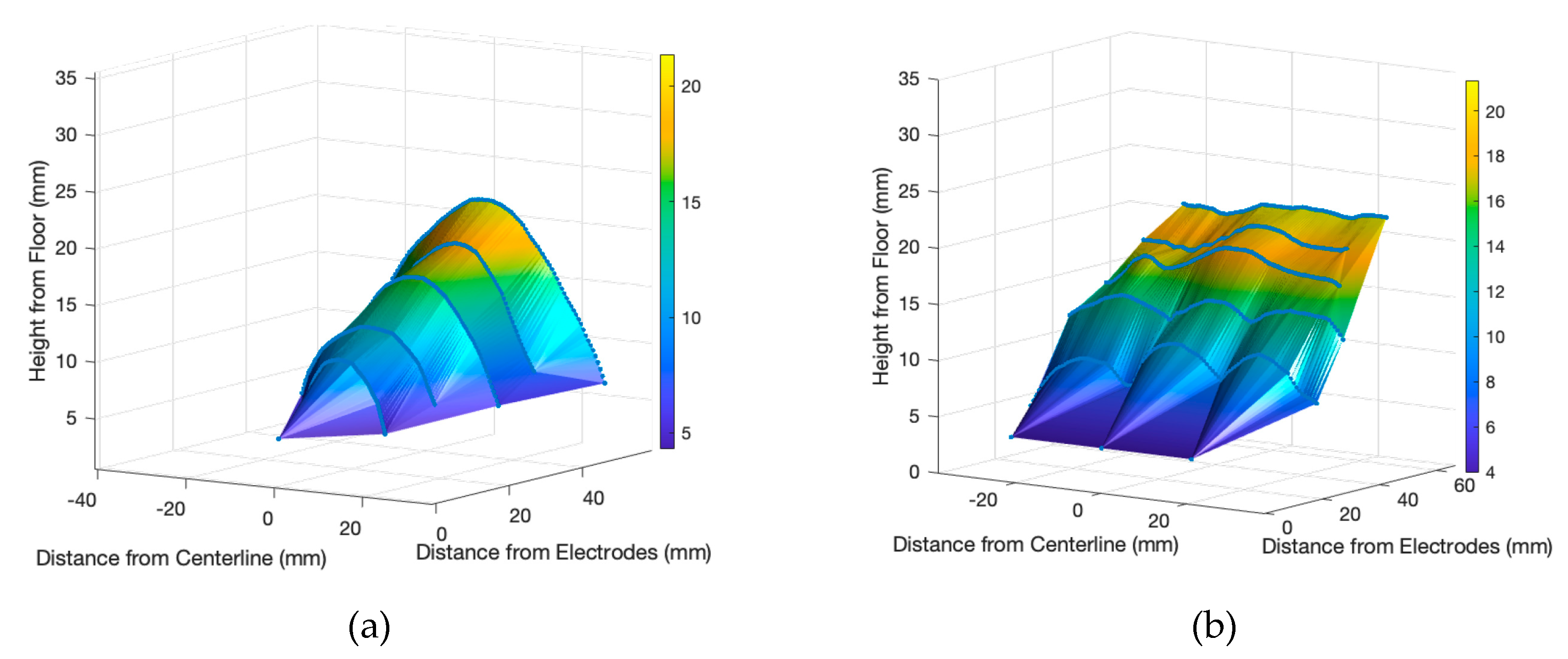

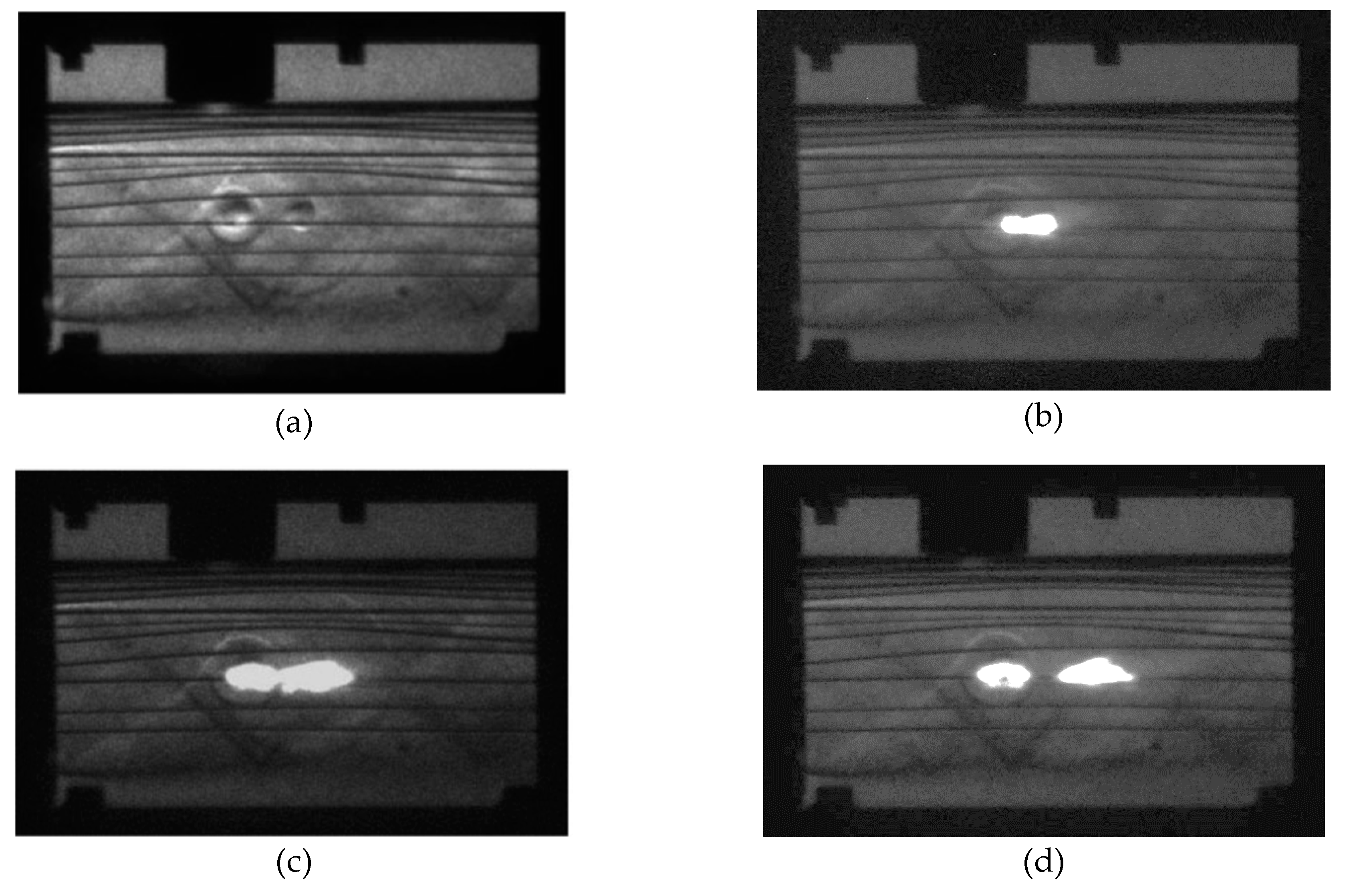

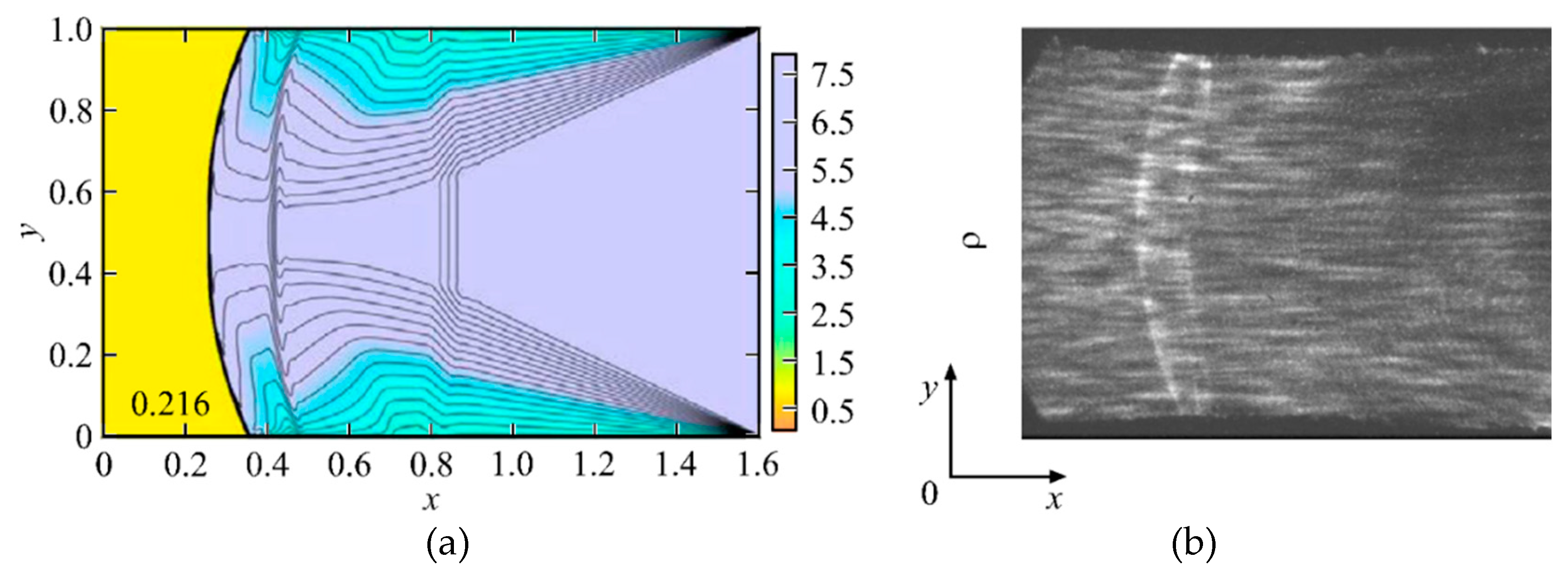

In [46–51] the S. Leonov’s group considered the problem of SWBLI and suppression of the different types of SWs by a streaming plasma array. The suppression of the reflected oblique shock wave by a filamentary plasma and the pressure distribution on the wall in a supersonic airflow of the Mach number M

∞=2 moving along a channel are obtained by S. Leonov et al. in [46–48]. Attention was paid to the effect of the filamentary plasma array on the reflection dynamics of the incident shock wave during its interaction with the BL. Methods used included schlieren imaging, plasma characterization by electrical probes, optical emission spectroscopy techniques, and wall pressure measurements along the test section. A filamentary plasma was generated between flush surface electrodes in the spanning array using a Q-DC electrical discharge (

Figure 1). In the experiment, the moving SW interacts with a perturbed BL generated by the plasma array. The structure of the plasma ES is a set of discontinuous alternant supersonic and subsonic longitudinal zones capable of effectively damping the force of the external impinging shock wave (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Therefore, the interaction parameters were shown to give the possibilities of an active SWBLI control.

The simulation results showed good agreement with the experimental results (

Figure 4). Thus, one may have the effect of weakening the SW due to the interaction with the stratified plasma in the modified BL. Another gas-dynamic phenomenon is the generation of streamwise vorticity, which can be realized by the interaction of the confined plasma with the airflow, as shown in

Figure 1b. An array of plasma flow vorticity generators was shown to prevent the flow separation Thus, the approach shows promising results for controlling both SWBLI and shock-dominated flows.

P. Andrews et al. in [49] continued the study in works by S. Leonov et al. [46–48] and considered the problem of SW/BSW control in the shock-containing flows. The triggering effect of patterned near-surface electrical discharges on the reflection SW was studied experimentally. A solid wedge SW generator was installed on the upper wall of the wind tunnel with the flow Mach number M

∞ = 4 and initial pressure

p0 = 4 bar, and filamentary electrical Q-DC discharges were placed on the opposite wall. At the same time, the SW moved from the wedge to plasma filaments located along the flow. The main results of the work include studying the details of the interaction of the SW with the plasma array (SWESI), as well as with a single filament, using schlieren imaging and pressure measurement. In addition, the three-dimensional shape of the SW structure was constructed both before and after electrical discharge activation using Mie scattering methods (

Figure 5).

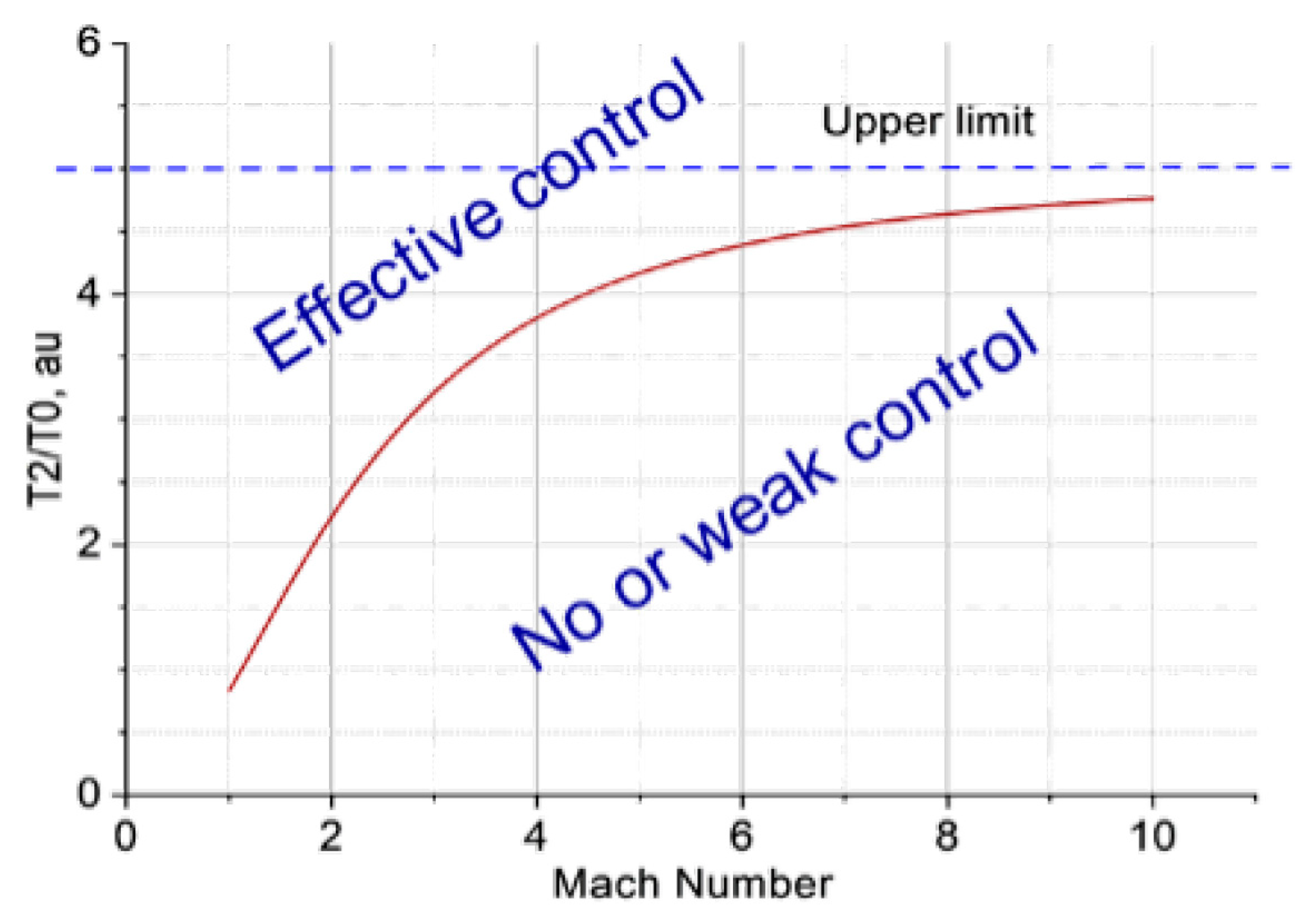

The physical principles of flow control and criteria for determining its effectiveness by plasma trigger mechanisms were formulated. Simplified criteria for the efficiency of the plasma control of the SW position are formulated as a function of the critical plasma temperature and the flow Mach number (

Figure 6).

S. Elliott et al. investigated the effects of Q-DC electrical discharges on supersonic flow dynamics in [50]. Schlieren imaging, pressure sensors, and pressure sensitive paint (PSP) were used to study shock-dominated flow behavior near a compression ramp. As a result, the attenuation of reflected SWs was observed, and the emergence of new oblique shocks was registered. Importantly, the experiments showed that the discharge action did not induce additional pressure losses in the channel. At the same time, F. Falempin et al. [51] focused on the influence of weakly ionized plasma on a 2D aerodynamic configuration with a three-shock compression ramp. The results showed significant changes in SWs positions, flow field structure, pressure distributions, and mass flow rates. These changes were influenced by power deposition and operating conditions, including converting a two-SW structure to a single SW and enhancing pressure recovery coefficients.

In [52], L. Feng et al. present the research on characteristics of instabilities originated during the interaction of a SW with the turbulent BL (SWBLI) which was controlled by high-frequency arc plasma energy deposition (APED) initiated by six pairs of electrodes. This study conducted experiments with Mach 2.5 airflow over a semicircular column with 15 kHz APED pulsing in the microsecond range and generating rapid, high-frequency thermal bubbles downstream. Time-resolved schlieren imaging at 30 kHz frame rate captured dynamic flow fields, focusing on how these thermal bubbles affected supersonic turbulent SWBLI instabilities. Analyzing 5000 schlieren images, the authors compared instantaneous and mean flow fields with and without APED control. Results revealed that the APED effectively reduced separation and attached SWs continuously, narrowed the low-frequency component of the oscillatory separation SW (SSW), and intensified of the attached SW oscillation. In addition, the thermal bubbles enlarged vortex scales in the turbulent BL and shear layer, increasing shear layer fluctuations with numerous high-frequency components. Continuous transformation of enlarged eddies along the shear layer weakened the SWs and modulated SWBLI frequency. Notably, the SSW experienced a frequency modulation with reduced low-frequency components, attributed to enhanced shear layer fluctuations and continuous upstream thermal bubble entry into the separation zone.

In [53] L. Feng et al. continue the research presented in previous work. The authors applied time-resolved schlieren imaging to observe the evolution of the turbulent SWBLI affected by the APED. The research also considered the effect of APED on the flow patterns in the absence of SWBLI at different condenser energy levels and flow deflection angles. Experimental results showed the perturbing effect of the APED on the incoming SWBLI decreased at higher flow deflection angles for the same energy deposition. Direct numerical simulations confirmed the preventing by the APED the velocity evolution of the turbulent BL, attributing the non-steady SSWs mainly to thermal bubbles that alter the BL compressibility, expand the separation zone, and contribute to the dispersion and displacement of the SW, in agreement with the experimental results.

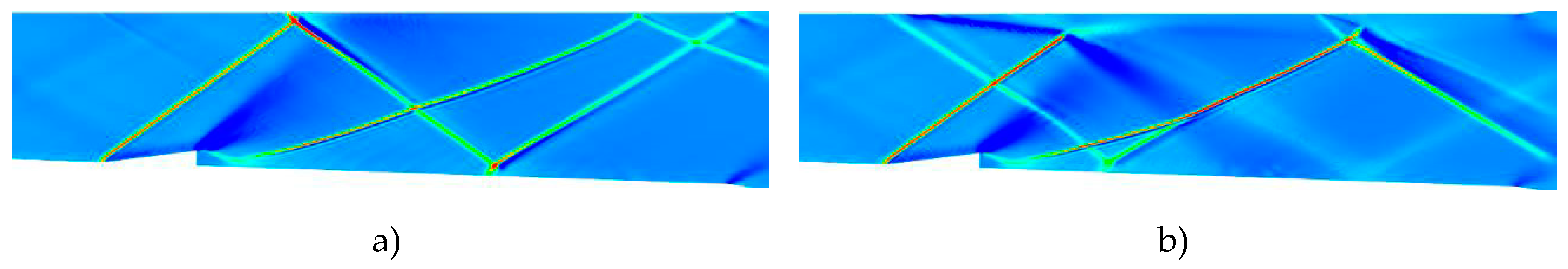

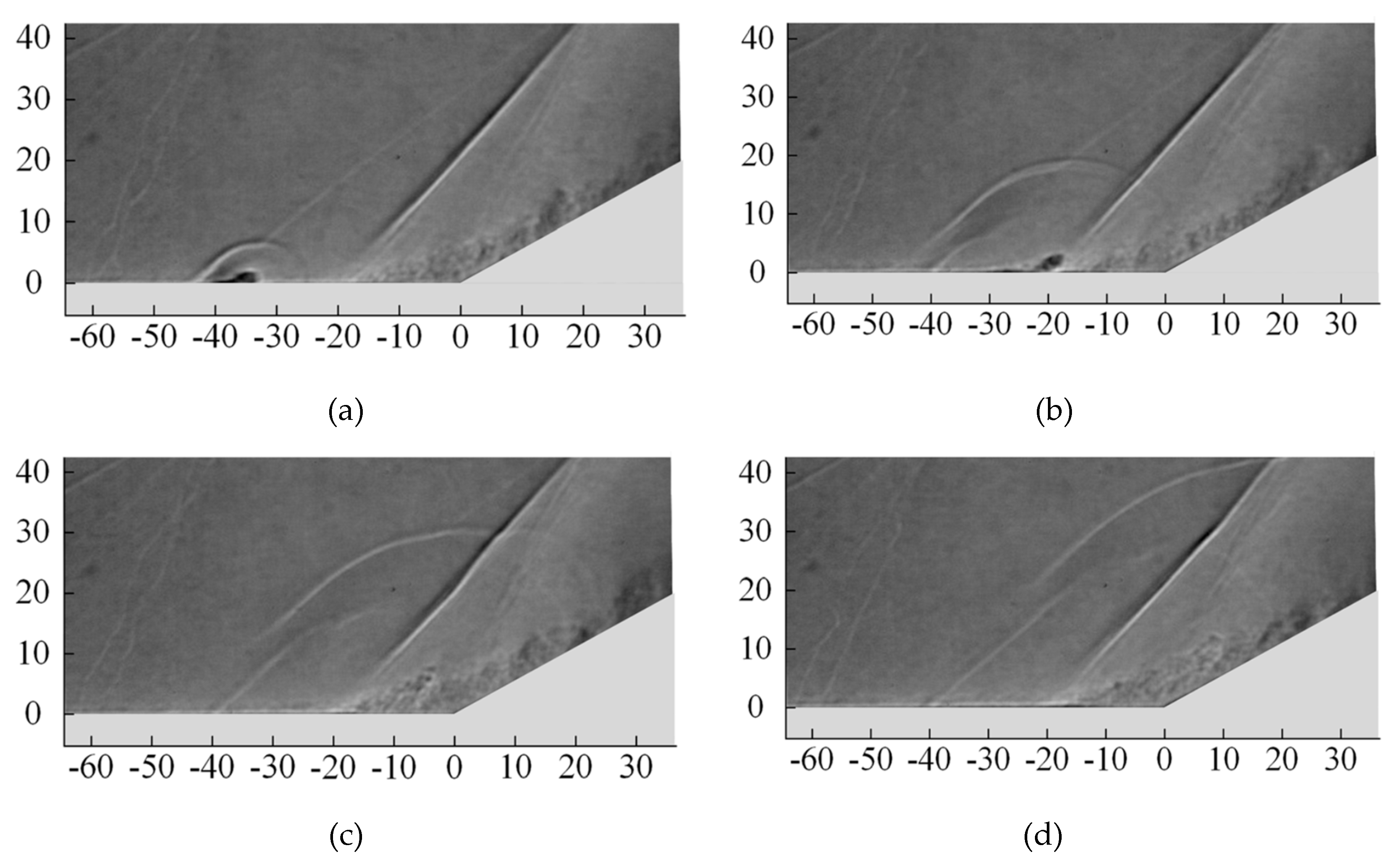

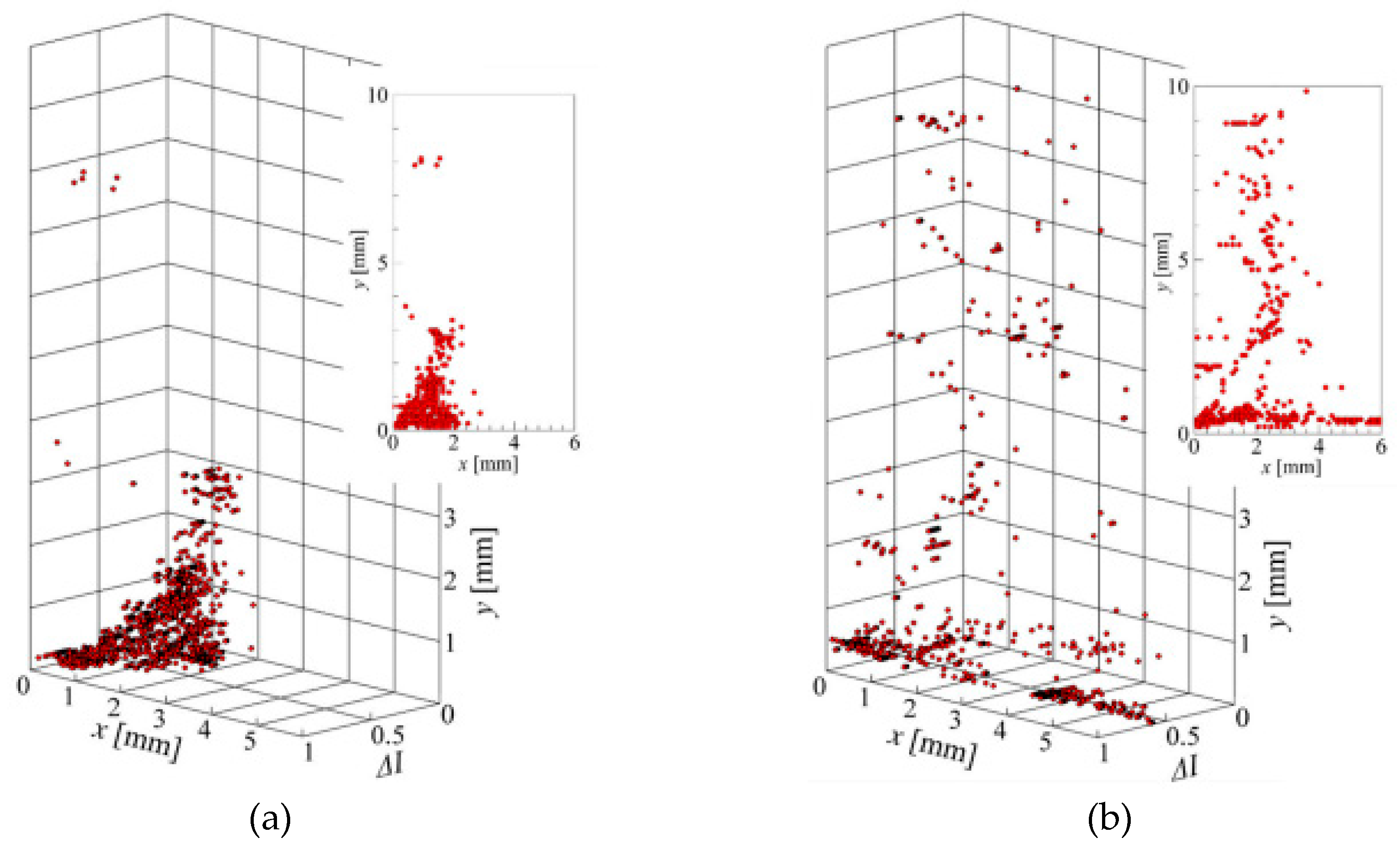

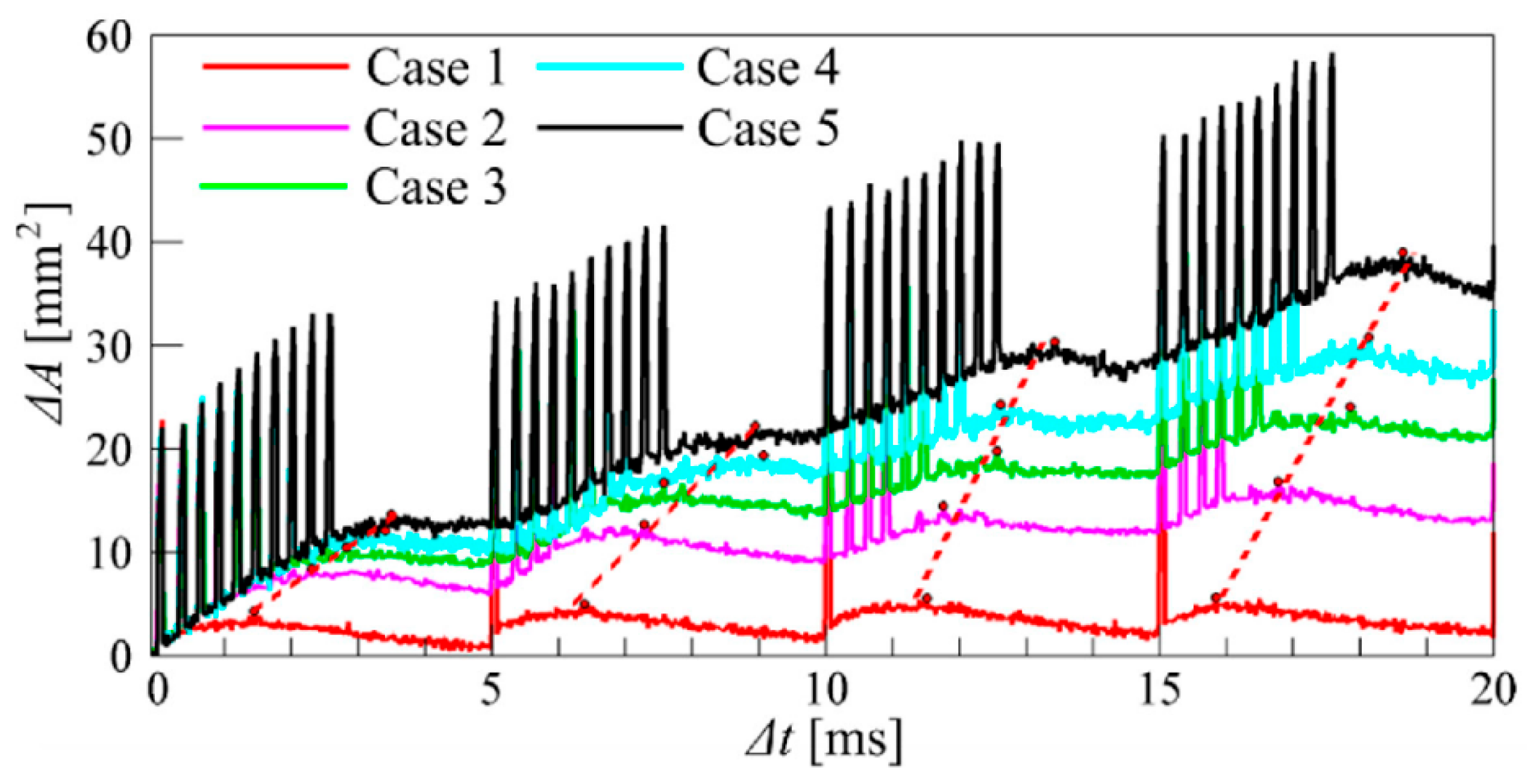

In [54–57] T. Gan et al. present a research on the control of the SWBLI using surface arc PAs (SAPAs). The study was conducted in a Mach 2.0 flow with a 26° wedge angle. An array of 16 SAPAs was used to precisely control the SWBLI phenomenon. This array operated at discrete frequencies, specifically 500Hz, 1kHz, 2kHz, and 5kHz, strategically positioned upstream of the SWBLI region. Complex flow dynamics were visualized using a high-speed schlieren imaging system capable of acquiring data at a 25,000 fps. The SW underwent profound changes induced by introducing control gas drops or control gas bottles generated by the SAPA array. These changes were manifested as the disappearance of the root portion of the SSW, accompanied by the branching of the oblique shockwave as the gas drops passed through the interaction region. The SW attenuation was additionally validated by analyzing root-mean-square schlieren intensity values. Comparisons were made between low-frequency and high-frequency actuation modes. Experimental results showed that the plasma actuation leads to the generation of numerous periodic streamwise vortices and small-scale trailing vortices in the high-frequency actuation mode. Consequently, it induces blurring and bifurcation effects on the SSW front and changes in the BL, as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. These results provide valuable insights into the control mechanisms for the SWBLI using a SAPA array.

In [58–60] H. Wang et al. presented of the results of the investigations on the topic of flow control with the use of a set of PAs. In the study in [58], the authors presented a strategy to suppress supersonic flow separation using high-frequency counterflow plasma synthetic jet actuators (CPSJAs). The primary objective was to investigate whether the control effectiveness of CPSJAs could be improved by their interaction with the jet/bow shock. Pulsed capacitive discharge was applied to an array of CPSJAs, resulting in the formation of the vortex rings, as was shown in schlieren images. Simulation results showed that the interaction between the CPSJAs and the BSW generated vorticity within the vortex ring. The result was a rapid deceleration of the jet and increasing the turbulent mixing in the synthetic jet. This interaction significantly disturbed the downstream flow. Furthermore, the study identified conditions under which the separation bubble could effectively suppress upstream laminar BL separation. As a result, CPSJAs were shown to be a promising technique for mitigating extensive separation regions in supersonic flows.

In [59,60] H. Wang et al. continue the previous studies and explored an innovative high-speed aerodynamic control technique using high-power, long-pulse-width pulsed discharges. Transient schlieren images describing the interaction between flow structures induced by the discharges and the SW-containing flow field were presented. The investigations, which include experiments in Mach 5 and Mach 6 wind tunnels and numerical simulations, evaluate the effects of these discharges on a conical configuration with two ramps. The discharges rapidly perturb the flow dynamics, weakening the attached boundary layer SW and altering the aerodynamic forces. Improved control is achieved with deeper plasma penetration, resulting in energy efficiencies ranging from 28% to 32% (M∞=5) and a maximum axial force reduction of 32.9% (M∞=6). This research demonstrates the potential of electrical discharges for efficient and rapid flow control in high-speed flows.

In [61], X. Ma et al. investigated the response characteristics of a SWBLI controlled by six high-frequency pulsed arc discharges in Mach 2.5 flow. The authors investigated evolution of the SWBLI under different excitation power and frequency conditions due to arc plasma energy deposition. The results show that the pulsed arc discharges profoundly affect SWBLI structures, distorting the SSW and improving flow control. Intense separation occurs in the initial flow field ahead of the semi-cylinder, forming SSWs and reattachment SWs accompanied by an expansion fan region. Plasma application weakens the oblique SWs, significantly expands the SWBLI zone with the upstream SSW motion, and provides continuous thermal excitation of the BL, reaching maximum penetration near the half cylinder. Various plasma conditions demonstrated removal of the upstream shear layer and reattachment of the SW foot. Higher power or frequency settings also provide better drag reduction effects, achieving up to 25.5% drag reduction rate under certain control conditions (2.5×1010 W/m3 /60 kHz).

M. Tang et al. experimentally investigated SWBLI control on a 24-degree compression ramp using a streamwise PAs array of five pulsed spark discharge actuators [62,63]. The results show a decrease in SW intensity as the separation region expands, decreasing the SSW angle from 41.6° to 22.3°. The study examines the time-averaged velocity field and the temporal evolution of the phase-averaged velocity field, highlighting the return of the flow field to baseline between actuation cycles and emphasizing the role of high-frequency actuation in maintaining control. Additionally, the streamline deflection when the flow is passing through the actuation region is observed. It is supposed that the flow deflection will also occur on both sides of the actuation region and produce the counter-rotating vortex, resulting in the separation reduction under the actuation. The research demonstrates a 45% reduction in the drag under the action of the PAs array and elucidates the principles underlying obtaining the continuous control.

In [64], H. Shahid et al. numerically investigated the effects of multiple opposing jets on atmospheric reentry vehicles. The research aims to optimize nozzle configurations to improve the aerodynamic and thermal properties of these vehicles, with a focus on maximizing drag reduction and temperature control. The simulations included four geometries: no nozzle, single nozzle, multiple nozzles located at the vehicle periphery, and multiple nozzles located closer to the stagnation point. The results show that single and multiple nozzles near the stagnation point reduce drag and heat, while the peripheral jets serve as an effective deceleration mechanism. The effect of angle of attack was shown to be more detrimental for single-nozzle jets than for multi-nozzle jets, with the latter operating more efficiently under these conditions. It was also found that shifting the position of multiple nozzles from the periphery to the stagnation point changes the jet behavior, resulting in improved drag and heat reduction, which is particularly useful for extreme angle of attack scenarios.

H. Xu et al. numerically investigated the effect of microjet pressure and multiple microjets on SWBLI control using a typical 24° compression corner model [65,66]. Results obtained using 3D Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations and two-equation shear stress transport k-ω both with k-ε turbulence models showed that microjet control relies on the generation of a counter-rotating vortex pair that mixes high-energy flow near the BL with low-energy flow within the BL. The size and proximity of the vortex core in this counter-rotating vortex pair played a critical role in the SWBLI control, with larger and closer vortex cores providing more effective control.

4. Filamentary plasma: control of SWESI

This part contains an analysis of the works on the control of SW interaction with energy sources (ESs) (SWESI), which are the inhomogeneous plasma structures (filamentary plasma). ESs are considered in the different forms of gas discharges: elongated elliptically shaped inhomogeneity generated via discharge providing the exploding wires, air glow gas discharge of constant voltage with formation of ionization strata, and other types of gas discharges. The results on a SW curvature, its blurring, weakening or disappearance were considered along with the manifestation of gasdinamic instabilities, the RMI and KHI. It should be underlined that the problem of SWESI is an important part of flow control because it models the impact of the ESs on the high-speed flows/flights.

In [67], S. Sembian et al. and in [68], N. Apazidis et al. presented a study of the interaction of a planar blast wave with an elongated rectilinear and inclined heat-generated inhomogeneity. Experimental and numerical studies are made of the unstable evolution of an elongated elliptical inhomogeneity immersed in ambient air and oriented perpendicularly and obliquely to an incident planar blast wave with Mach number 2.15. In the experiments the gas heating from an exploding wire generated elliptical inhomogeneities and SWs. Shadow patterns for rectilinear inhomogeneities (α = 0◦) are presented together with the corresponding numerical fields of density gradients and vorticity, which demonstrated the manifestation of the RMI. Also, presented is an experimental shadow photograph and a numerical density gradient field corresponding to the case of an oblique inhomogeneity (α = 24◦), depicting the structure of the vortex street accompanying the formation of the KHI. Furthermore, a unique linear equation governing the normalized circulation has been derived through numerical simulations. In the case of α = 24◦ a vortex tail resembling the KHI was observed. The initial velocity of each vortex in the series was shown to correlate with the intensity of the transmitted wave. In contrast, it was observed a linear decrease in velocity over time as the vortex train expanded.

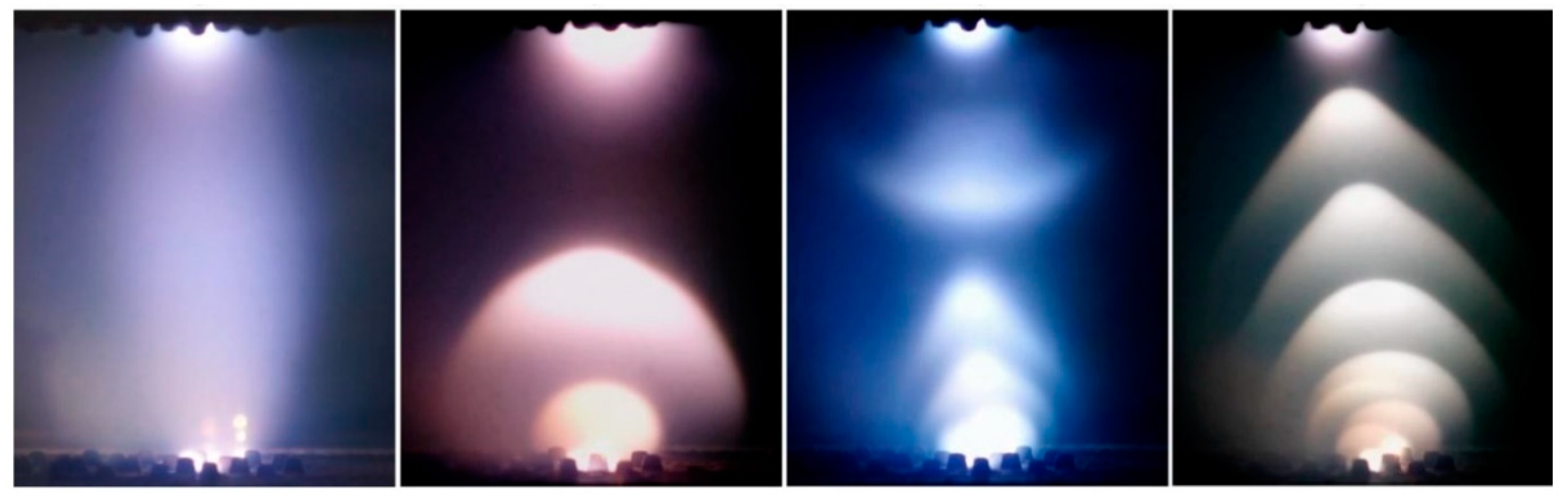

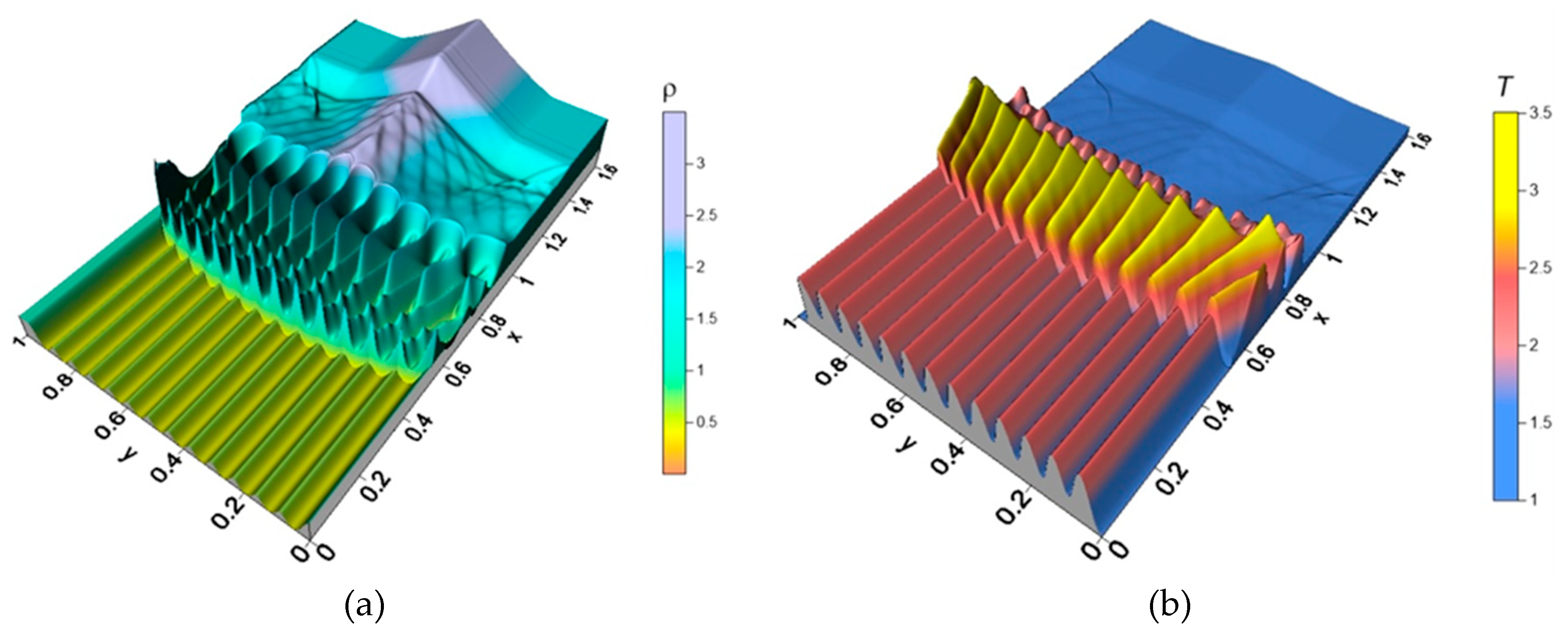

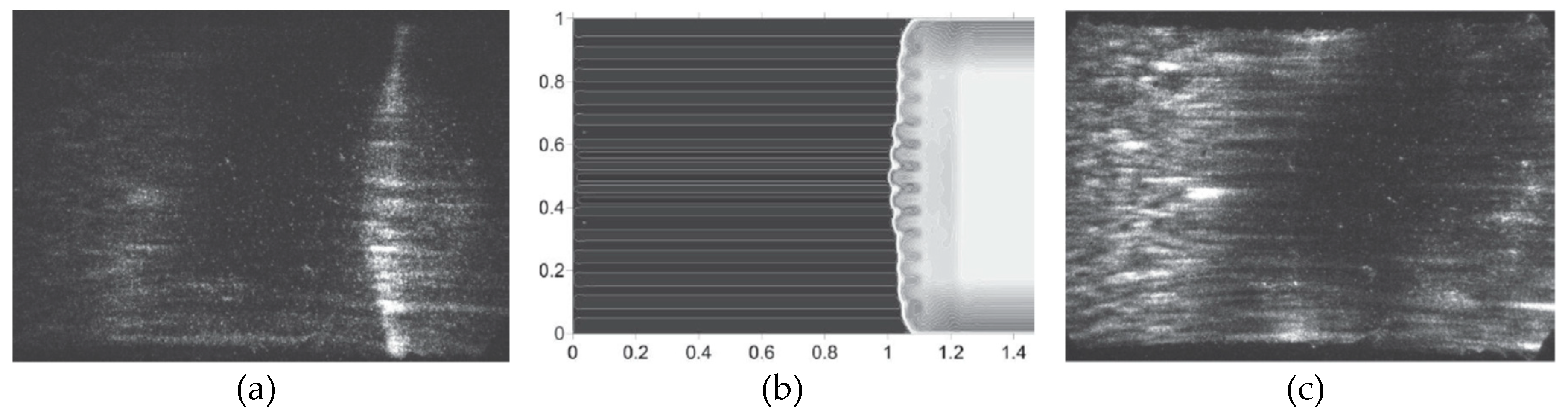

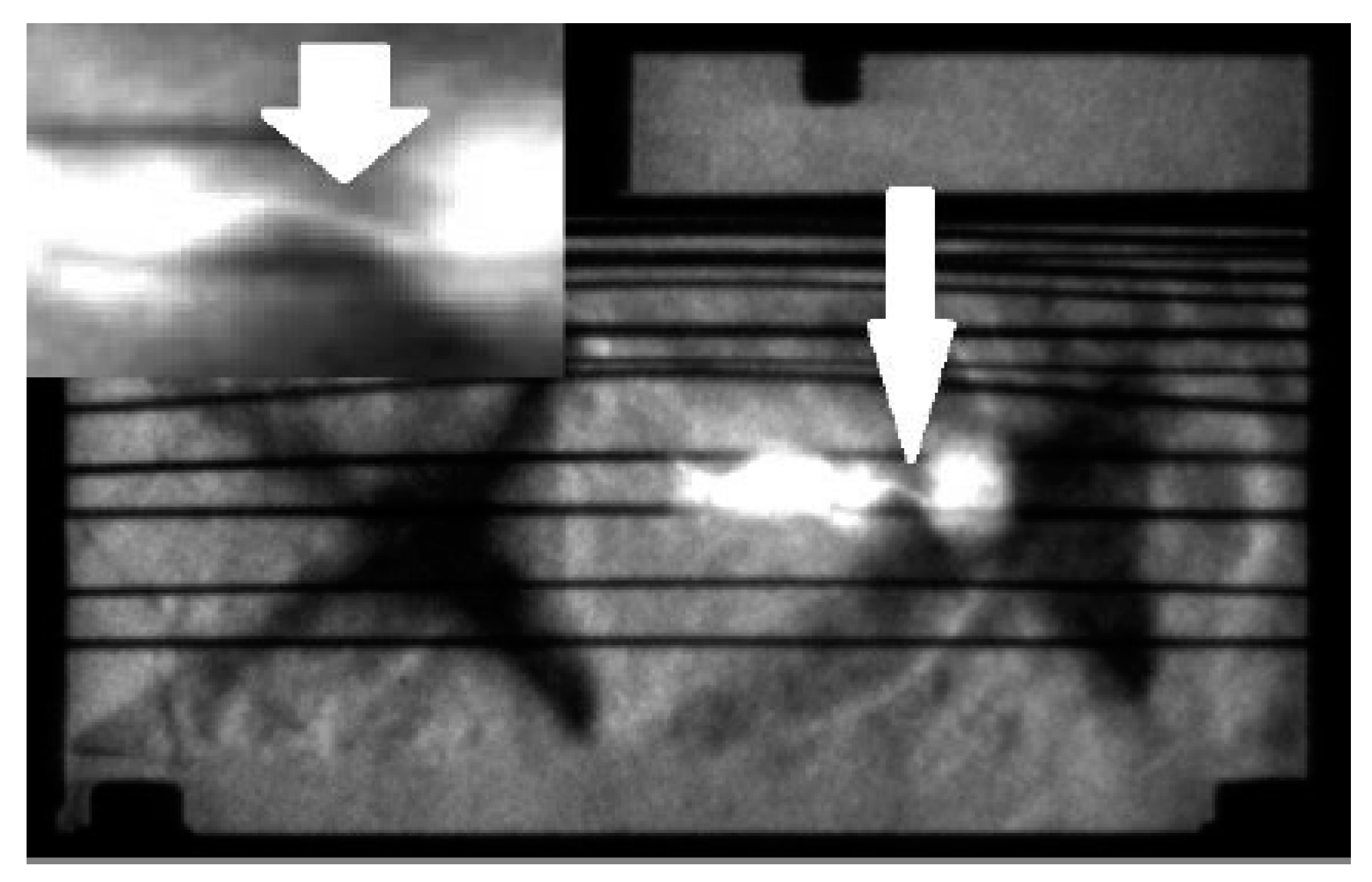

The studies of T. Lapushkina et al. and O. Azarova et al. [69–73] are devoted to ionization instability in air gas discharges of different scales. The experiments involved a constant voltage gas discharge in an open chamber without sidewalls, leading to formation of ionization strata within the discharge region due to ionization instability. The scale of these ionization layers changed as a function of discharge conditions such as pressure or gas discharge current, resulting in a multilayer plasma medium with varying electron and gas temperatures. Different types of discharges were observed, ranging from large-scale structured (3-5 striations per discharge length) (

Figure 9) to small-scale (20-25 striations per discharge length) (

Figure 10), and their occurrence and development conditions were studied [69,70].

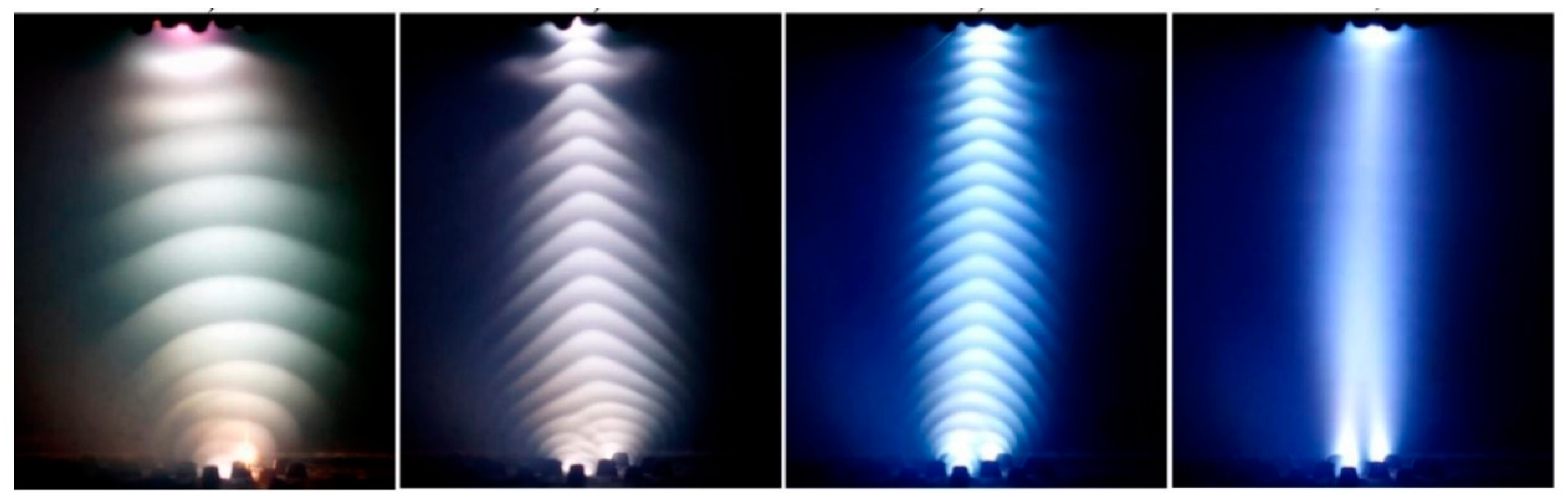

In addition, the interaction between a SW and a pre-established stratified gas discharge plasma was investigated experimentally and numerically, resulting in the formation of a new SW configuration during SW – energy source interaction (SWESI) and the curvature of the SW (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). This interaction was found to cause significant waveform distortion, including destruction, that was obtained experimentally and numerically in [71–73] (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

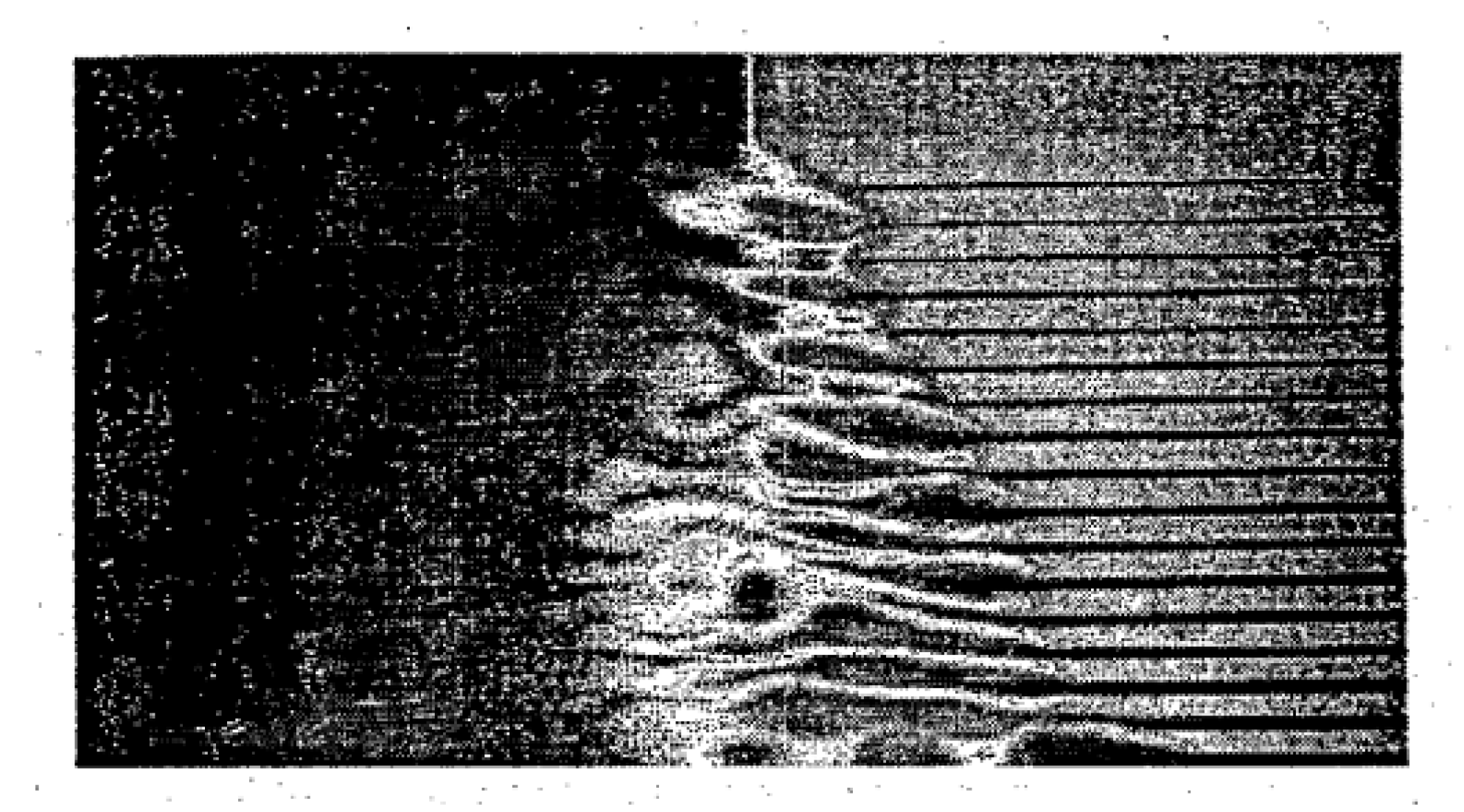

In [25], V. Bityurin et al. considered the interaction of longitudinal pulse discharge with the SW. In the numerical simulations the authors assumed that the discharge plasma has a layered inhomogeneous structure due the streamers origination. The problem was considered in a cylindrical formulation without taking into account the effects introduced by viscosity and thermal conductivity. The plasma inhomogeneity was formed by specifying heated cylindrical layers of different widths. As a result of the simulation, the curvature of the initial SW front (due to the difference in the parameters of the heated layers) was obtained, as well as the zone of gas-dynamic instabilities (vortex structures) located behind the modified SW front (

Figure 15).

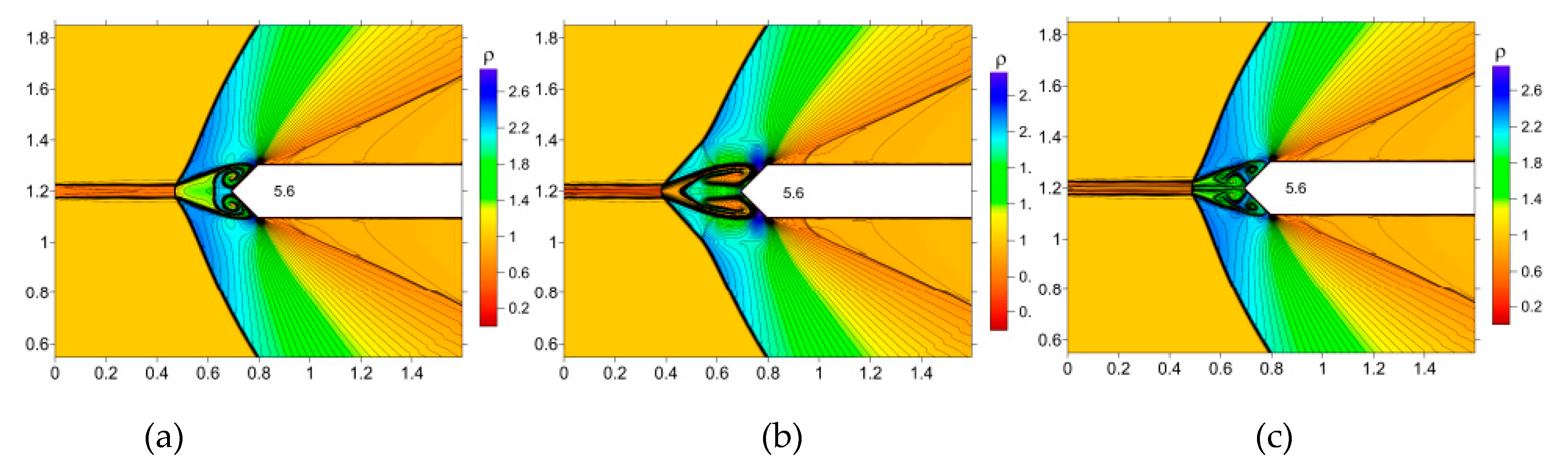

5. Multi-component plasma structures: experimental obtaining and modelling

In this part we consider the works on the experimental obtaining and modelling spatially multi-component plasma structures, such as localized double and multiple MW discharge in air, MW radiation produced through a filamentation of ultrashort high-intensity laser pulses in the atmosphere, NS-SDBDs, NS-DBD burst multiple PAs, and a surface barrier corona discharge actuators. The part contains a review of the results of physical-mathematical model included a set of thirteen plasma-chemical reactions and the study of localized multiple MW discharge in air, the model for MW plasma waveguides induced in the atmosphere through the filamentation of high-intensity ultrashort laser pulses, results on the increasing lift, reducing drag and trailing-edge excitation, as well as the prediction of the length and time scales of the filamentary plasma induced by NS-SDBDs, and possibility of noise mitigation using barrier corona discharge.

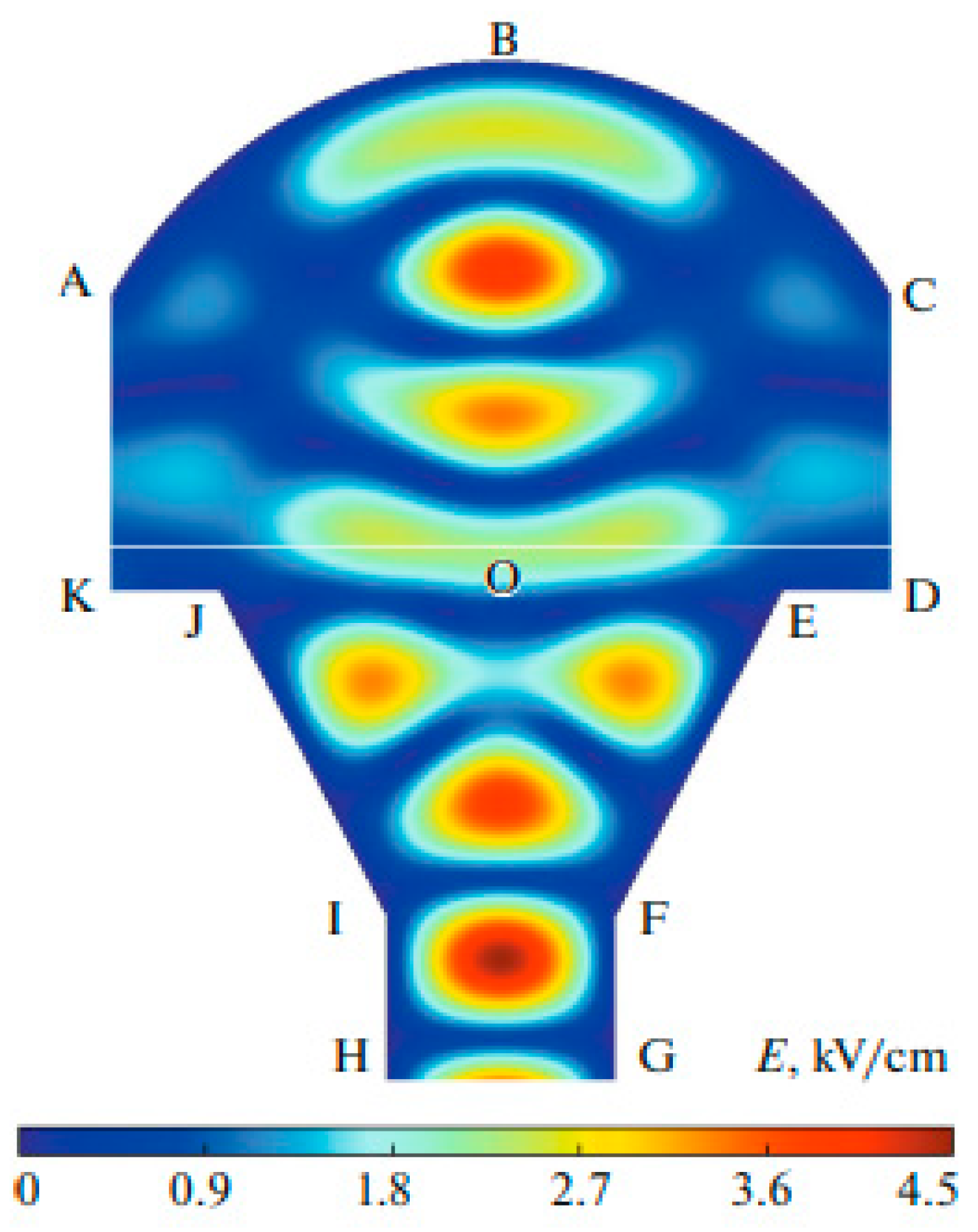

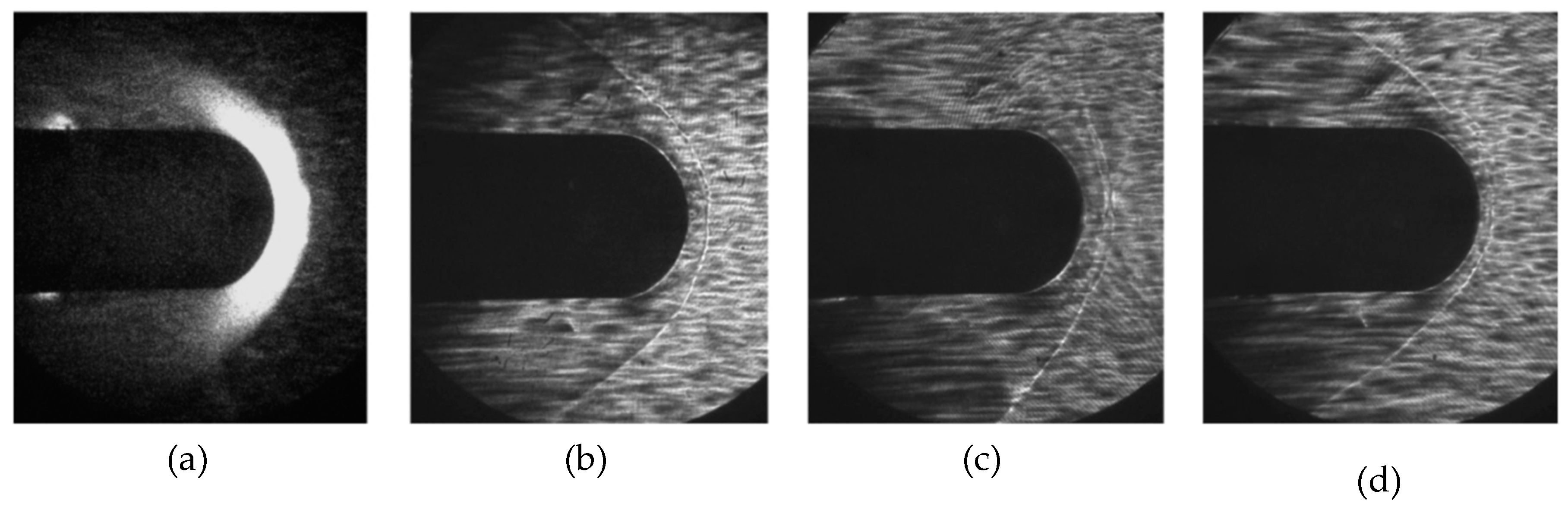

In [74], A. Saifutdinov et al. performed numerical simulations using an extended hydrodynamic model to investigate the dynamics of parameter formation of a MW discharge in air. This MW discharge was localized at electric field maxima generated by a custom-designed focusing system in an experiment. The authors comprehensively determined all the critical parameters of the MW discharge plasma and captured images of elongated plasmoids aligned with the supersonic flow axis ([75] by R. Khoronzhuk) (

Figure 16).

The model included thirteen plasma chemical reactions for the simulation a SW in air (

Figure 17) showed that the focusing system led to the emergence of two MW discharges (plasmoids). The study also provided insight into the electron density and electric field strength distributions of these discharges. It was shown that optimal gas heating occurred when the MW discharge was excited at the focus of the system. These studies made a significant progress in understanding the physics of focused MW discharges.

M. Shneider et al. performed a self-consistent plasma-dynamic analysis and numerical simulations of long-lived laser-induced MW plasma waveguides in the atmosphere [76]. The authors developed a comprehensive model to assess the lifetime limits of these MW plasma waveguides generated by filamentation with high-intensity ultrashort laser pulses and sustained by longer laser pulses, integrating plasma kinetic, Navier-Stokes equations, electron heat conduction, and electron vibrational energy transfer equations. It was shown that near- or mid-infrared laser pulses can extend the lifetime of plasma waveguides by effectively increasing electron temperatures, thereby reducing electron attachment to neutral species and dissociative recombination. This enhancement enables MW transmission over long distances through the plasma waveguide. The findings obtained offer new possibilities for long-distance MW transmission.

C. Clifford et al. conducted NS-DBD experiments on a NACA 0015 airfoil in a wind tunnel at 15° angle of attack [77]. Four symmetrically placed actuators on the upper and lower surfaces of the airfoil, at the aerodynamic leading edge and the aerodynamic trailing edge, were constructed using two copper strip electrodes. These actuators extended into the wake region, slightly broadening and reducing the separation area, resulting in a 37% reduction in separation area, a 42% increase in lift, and a 20% reduction in drag. In addition, the plasma triggering at the aerodynamic trailing edge reduced the amplitudes of the pressure spectrum peaks over a wide range of Strouhal numbers.

In [78], L. Rajendran et al. investigated the length and time scales of filamentary surface plasma discharge in the context of using NS-SDBD actuators for high-speed flow control at supersonic and hypersonic conditions. These actuators utilize short nanosecond high voltage pulses to rapidly energize the electrode gap (see [79] by J. Little, [80] by L. Wang et al., and [14] by A. Russel et al.). NS-SDBDs are a type of PAs that employs high-voltage nanosecond pulses between surface-mounted electrodes, inducing electrical breakdown in the surrounding air and rapid heating. When operated at high pulse frequencies, these actuators generate multiple filaments, forming SW structures and complex flow patterns, such as vortex ring. A reduced-order model for the cooling induced by the vortex ring as presented. The results of this study demonstrate that a vortex ring-based cooling model effectively predicts the length and time scales of nanosecond surface discharge-induced flow. These predictions provide valuable insights for optimizing multi-filament, multi-pulse NS-SDBD actuators commonly used in flow control applications. This model also helps to bridge the gap between the early and late stages of the induced flow. Notably, the flow exhibited pronounced three-dimensionality during the experiments, necessitating the corresponding volumetric velocity and density field measurements.

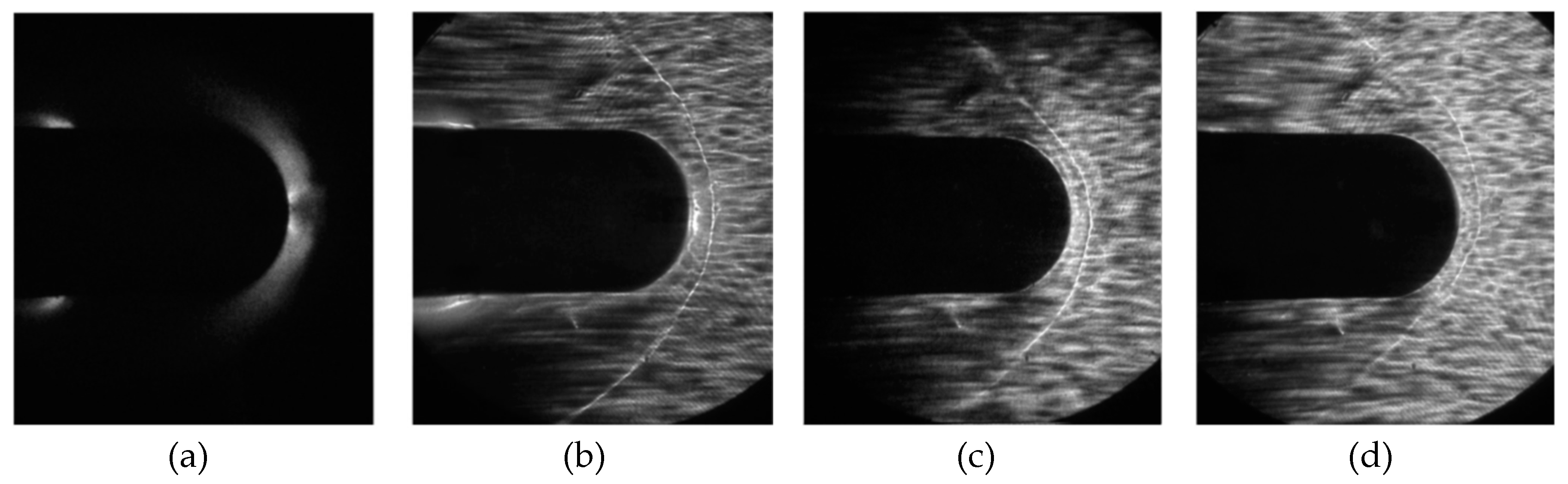

T. Ukai and K. Kontis analyzed thermal fluctuations around NS-DBD plasma actuators using schlieren-based frequency analysis [81]. These thermal fluctuations are critical for effective flow control in high-speed flows. The focus of this study was on the burst plasma actuation, which can improve flow control by delaying separation and increasing turbulence. Schlieren images show more significant thermal perturbations during burst plasma discharges than in non-burst cases. These perturbations gradually increase as multiple plasma discharges supply thermal energy before diffusing due to thermal equilibrium (

Figure 18). Even after the discharge stops, the thermal regions before diffusion grow slightly. A burst plasma discharge creates a hot plume, resulting in different thermal patterns, often fluctuating at 200 Hz at high burst ratios (

Figure 19). Therefore, these wave-like thermal fluctuations can improve the process of flow control.

In [82] V. Kopiev et al. investigated the use of various plasma actuators (PAs) to control instability waves in turbulent jet shear layers, which are a significant source of aircraft noise. The results of testing three types of PAs are presented: high-frequency dielectric barrier discharge (DBD), slipping surface discharge, and surface barrier corona discharge. Particle image velocimetry measurements showed that these PAs effectively suppressed artificially induced instability waves in turbulent air jet shear layers at atmospheric pressure. These results suggest promising applications for PAs in jet noise suppression and provide directions for further research in this area.

6. Repetitive multiple laser pulse plasma structures: control of BSWESI and SWBLI

Research has revealed that a single laser pulse falls short in igniting combustible gas due to the rapid loss of over 90% of absorbed energy within the initial microseconds through SW and radiation losses, leaving a mere 7% to 8% of energy available for ignition (see [83] by T. Phuoc). Consequently, numerous studies have focused on exploring the efficacy of employing a sequence of two consecutive pulses or multiple repetitive pulses, as opposed to a solitary pulse, as a means to enhance the energy delivered by laser sparks (LSs) for igniting combustible gases. In this section, we review selective studies on the effects on flow control using plasma structures initiated by multipulse laser action. The studies include the consideration of a problem of BSWESI control, the models of pulsating heat supply, the models included different species and chemical reactions, the comparison of the effects for different shapes of bodies. The results on the influence of Mach number and ES location are examined from the point of view of the lift-to-drag ratio improving. Also, the results describing the double vortex mechanism for the drag reduction are presented which leads to the intensification in the frontal drag force reduction and suppression of shear layer instability and large scaled flow pulsations.

In [84] S. Guvernuk and A. Samoylov investigated a problem of supersonic control of a flow over AD body using a repetitively pulsed source of external energy supply. In this work, the effects of the influence of a repetitively pulsed source of external energy supply on the AD characteristics of a downstream hemisphere are modeled. The dependence of the shape of an energy deposition and its effect on the flow on the pulsation frequency was studied, and it was shown that the regime of pulsating heat supply can be more efficient than a stationary one.

K. Anderson (Norton) and D. Knight studied the interaction between repetitively heated filaments and a blunt cylinder in a supersonic flow in [85–87]. The authors performed simulations in which the pulse energy deposition time was varied to assess its effect on heat transfer to the body. When the L/D ratio was 4/3, the filament spacing proved to be optimal, resulting in effective aerothermodynamic streamlining of the body. This streamlining resulted in a reduction in both average drag and average heat transfer. Within the streamlined region, a toroidal vortex of low-velocity flow was formed, facilitating the development of a thermal layer at the cylinder face while eliminating the stagnation point, thereby reducing heat transfer between the cylinder face and the flow. As a result, this research demonstrated that energy deposition can efficiently reduce drag without increasing the overall thermal load on a blunt body.

In [88], U. Padhi et al. performed numerical simulations of supersonic airflow under two consecutive laser pulses in stationary air. The second pulse was introduced into the previously created air breakdown zone created by the first pulse. Air dissociation and recombination in the high-temperature breakdown zone were modeled with five species and eleven reactions, assuming local thermal equilibrium conditions. The results revealed two distinct phases in laser spark decay: the first phase involved SW generation and propagation, while the second phase involved changes in the ignition core. Using repetitive pulses instead of a single pulse resulted in the propagation of a SW layer, and increasing the delay between pulses enhanced the evolution of the secondary SW around the breakdown zone. It was shown that the repetitive pulses with different delays induced significant changes in the density field and temperature range (

Figure 20), with perturbations depending on the time intervals between laser pulses.

A. Sangtabi et al. numerically investigated the effects of repetitive laser pulse energy deposition on supersonic flow around three shapes: sphere, cone, and oblate spheroid [89]. The authors compared the effects among these shapes regarding pulse number, frequency, Mach number, and energy deposition location. The energy saving efficiency calculated as:

was evaluated for these three shapes of AD body for the total energy value

Q. Here, the drag force increment after the interaction of the BSW with the blast wave (the negative term (1 −

D/

D0)), the duration of drag reduction

dt, the steady drag force

D0 and the free stream Mach number M

∞ were indicated as four defining parameters in the energy saving efficiency.

The results led to several observations. Dividing the total energy into multiple pulses with lower energy levels significantly increased the duration of drag reduction, with energy saving efficiencies of 199%, 93%, and 24% for a single pulse on the sphere, oblate spheroid, and cone, respectively. Changing the frequency from 50 kHz to 100 kHz increased the drag reduction duration and reduced the drag force fluctuations. In addition, the authors observed an inverse relationship between drag reduction duration and free-stream Mach number, with energy saving efficiencies improving by 212%, 215%, and 110% as Mach number increased from 2.5 to 5 for the sphere, oblate spheroid, and cone, respectively. Finally, it was found that the diameter of the blast wave/low-density region increased as the distance between the energy deposition point and the body increased, resulting in increased efficiency of the blast wave-BSW interaction for the sphere and oblate spheroid. At the same time, the cone showed a slight decrease in efficiency. Thus, the results presented showed effective drag reduction for all shapes, with the blunt shapes (sphere and oblate spheroid) outperforming the cone in drag reduction.

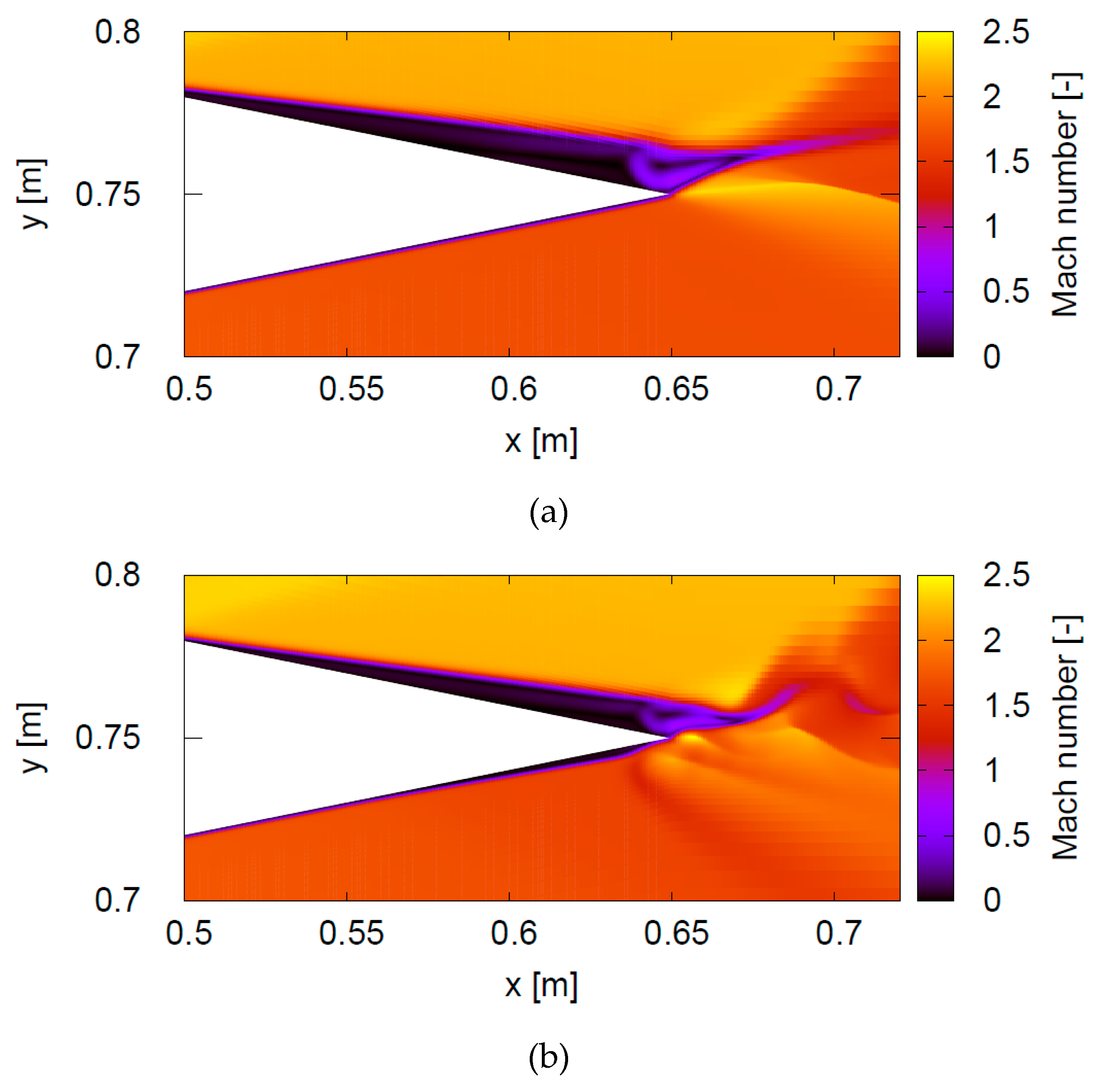

In [90], M. Takahashi and N. Ohnishi explored the potential for controlling airfoil separation using repetitive laser pulses. They conducted experiments with a flow Mach number of 1.7, an altitude of 20 km, and an angle of attack of 10 degrees. Repetitive pulses were directed at the underside of a diamond-shaped airfoil to mitigate flow separation on the upper surface. The rapid heating from the repetitive pulses generated a powerful SW from a focal point, leading to the induction of an expansion wave at the trailing edge as the supersonic SW propagated from the underside to the top surface, resulting in a reduction of the separation region on the top surface. A comparison of the local Mach number fields between cases without laser impact and those subjected to multiple laser pulses is shown in

Figure 21. The research demonstrated that repetitive pulse energy deposition improved the lift-to-drag ratio of the wing, highlighting the effectiveness of a “contactless” flow control method through numerical simulations.

In [91], O. Azarova conducted a numerical investigation of supersonic flow control by combined energy deposition methods, considering various body shapes such as blunt cylinders, hemispherical cylinders, and pointed bodies over a range of freestream Mach numbers from 1.89 to 3.45. The study showed that the drag reduction was due to complex unsteady vortex structures resulting from the RMIs. Two mechanisms were described: the unsteady double vortex mechanism for frontal drag reduction and the constantly acting vortices in a steady flow. It was shown that the combined energy release suppressed the shear layer instability and large-scale flow pulsations. In particular, drag control showed significant improvements, with a 19% reduction for blunt cylinders and a 52% reduction for hemispherical cylinders, achieved by combining energy deposition with an interior rarefaction parameter α

ρ1 less than that of the initial filament: α

ρ1 < α

ρ (

Figure 22a). This effect was associated with generating two vortices rotating in the same direction. When α

ρ1 > α

ρ, the generating vortices rotated in opposite directions, resulting in a reduced drag force change (

Figure 22b). The study investigated the structure of unsteady and steady flow fields for pointed bodies under different types of filaments (

Figure 23). It was established a steady flow mode characterized by a constantly acting vortex pair, reducing frontal drag by up to 71% (

Figure 23b).

7. Self-sustained theoretical models: dual-pulse laser, multi-mode laser pulses and self-sustained glow discharge

This part is devoted to the analysis of three self-sustained theoretical models: the model of dual-pulse laser ignition, the model of nano-second multi-mode pulses, and the model of self-sustained glow discharge. These models include additional plasma reactions for the description of non-equilibrium plasma generation and a self-consistent theoretical approach for mathematical formulation for inhomogeneous current contraction of a self-sustained glow discharge. Below these models are discussed separately.

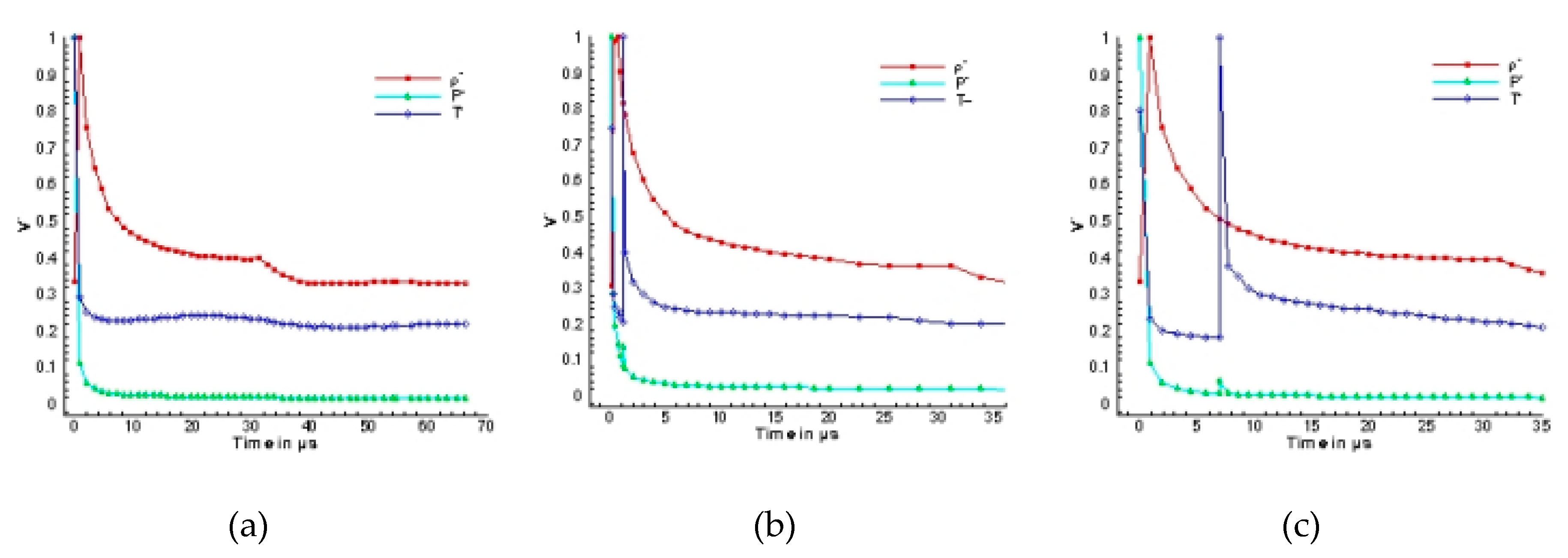

In [92,93], A. Tropina et al. and in [94], R. Mahamud et al. presented a comprehensive two-dimensional mathematical model for dual-pulse laser ignition. This model combines the Navier-Stokes equations with equations for translational and vibrational energy and neutral and charged species. The spatial contours of the temperature for one of the base cases were shown along with the velocity vectors and streamline profiles with respect to the temperature contours, as well as the spatial contours of different species after 60 µs. The results indicated that the behavior of the ignition core is influenced by the shape and initial energy distribution within the energy spot created by the initial ultraviolet laser pulse. In addition, the research underscores the significant influence of laser intensity, vibrational non-equilibrium, and initial electron number density on the ignition delay time and flame kernel evolution.

A. Alberti et al. investigated non-equilibrium plasma generation using nanosecond multi-mode laser pulses in [95]. The authors used a self-consistent computational model to study the formation and growth of plasma cores generated by these pulses, incorporating non-equilibrium effects through a two-temperature model and treating the plasma with an approach based on the Navier-Stokes equations. The propagation and attenuation of the laser beam was simulated using the radiative transfer equation coupled with the flow governing equations. The results successfully replicated critical experimental findings, including a two-lobed plasma core and the appearance of quasi-periodic structures. It was shown that the occurrence of these structures is closely related to the mode splitting frequency of the laser, which corresponds to local power peaks in the incident beam. Furthermore, the modulation frequency of the laser was found to affect the local electron density and temperature, resulting in a more elongated plasma for multi-mode pulses compared to single-mode pulses.

In [96] M. Shneider et al. performed a numerical study of the dynamic contraction of the current channel within a quasi-neutral positive column of a self-sustained glow discharge occurring in a rectangular channel with the convection cooling. The authors developed a self-consistent theoretical model to describe the inhomogeneous current contraction in this glow discharge, including a comprehensive set of two-dimensional equations that take into account the ionization thermal instability. This self-sustained glow discharge occurred in a molecular gas (nitrogen) stabilized by an external circuit and subjected to convective heat loss. The study illustrated the evolution of the contracted channel as it progressed from one electrode to another until it reached a longitudinally uniform contracted state. The propagation velocity of the contraction was also estimated and compared with the existing experimental results.

8. Flow control using combined physical phenomena

In this part we discuss the experimental works on organization and study the MW discharge initiated by single and double LSs in a supersonic flow, pulse volumetric electric discharge and a discharge organized as a pulsed plasma column with the use of plasma sheets. The results within the framework of organizing control of supersonic flows are also considered: PGD, EGD and MHD impact for the purposes of the BSW control, and an energy supply to one side of the wedge due to a spark discharge (“plasma wedge”) which is an example of coupling the mechanical and energy approaches to flow control.

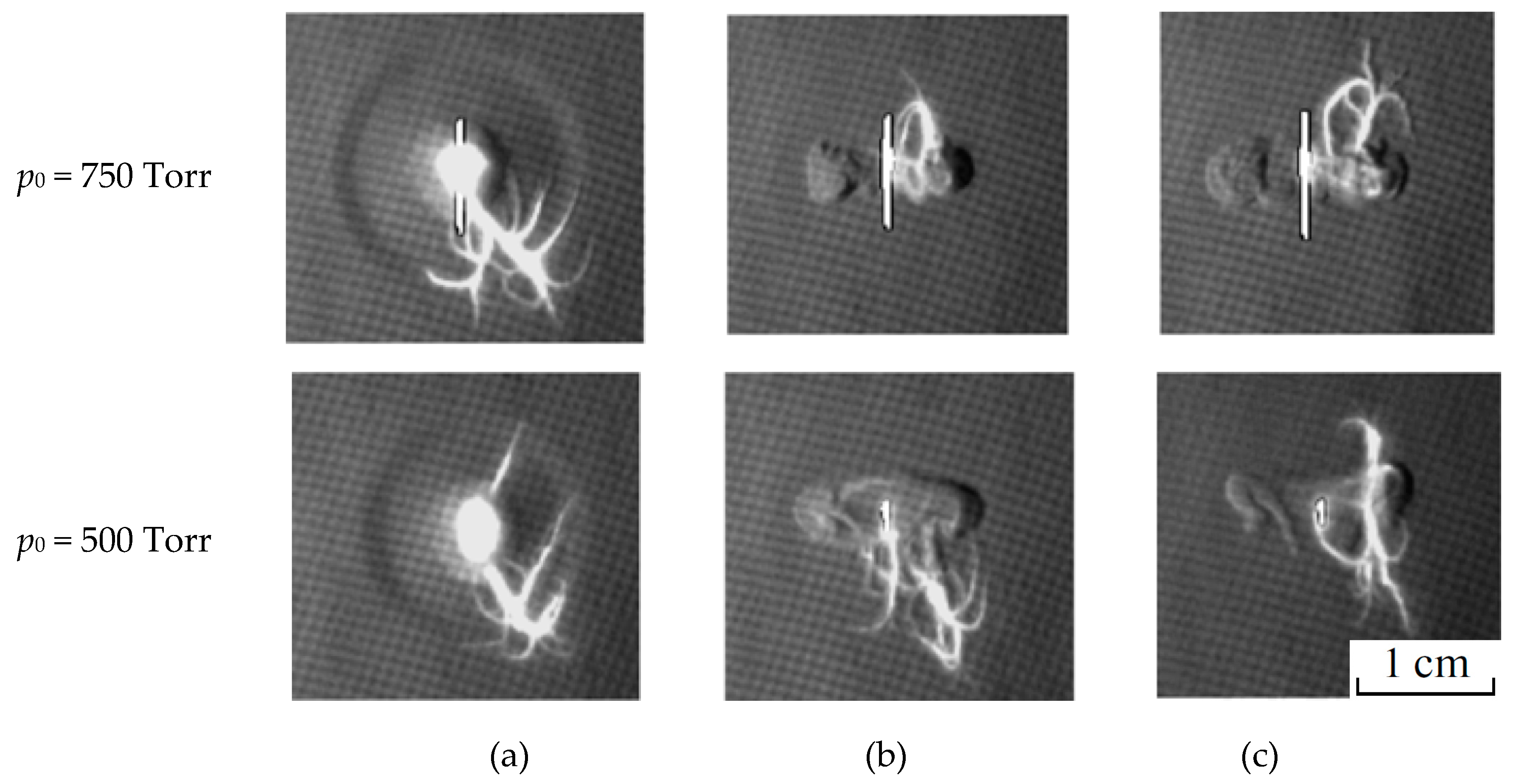

S. Afanas’ev et al. conducted experiments in [97] to investigate the effect of gas-dynamic processes on the characteristics and initiation threshold of a laser spark (LS) initiated MW discharge in the open air (see

Figure 24 and

Figure 25).

Here MW beam propagates from left to right, laser beam propagates from top to bottom. In

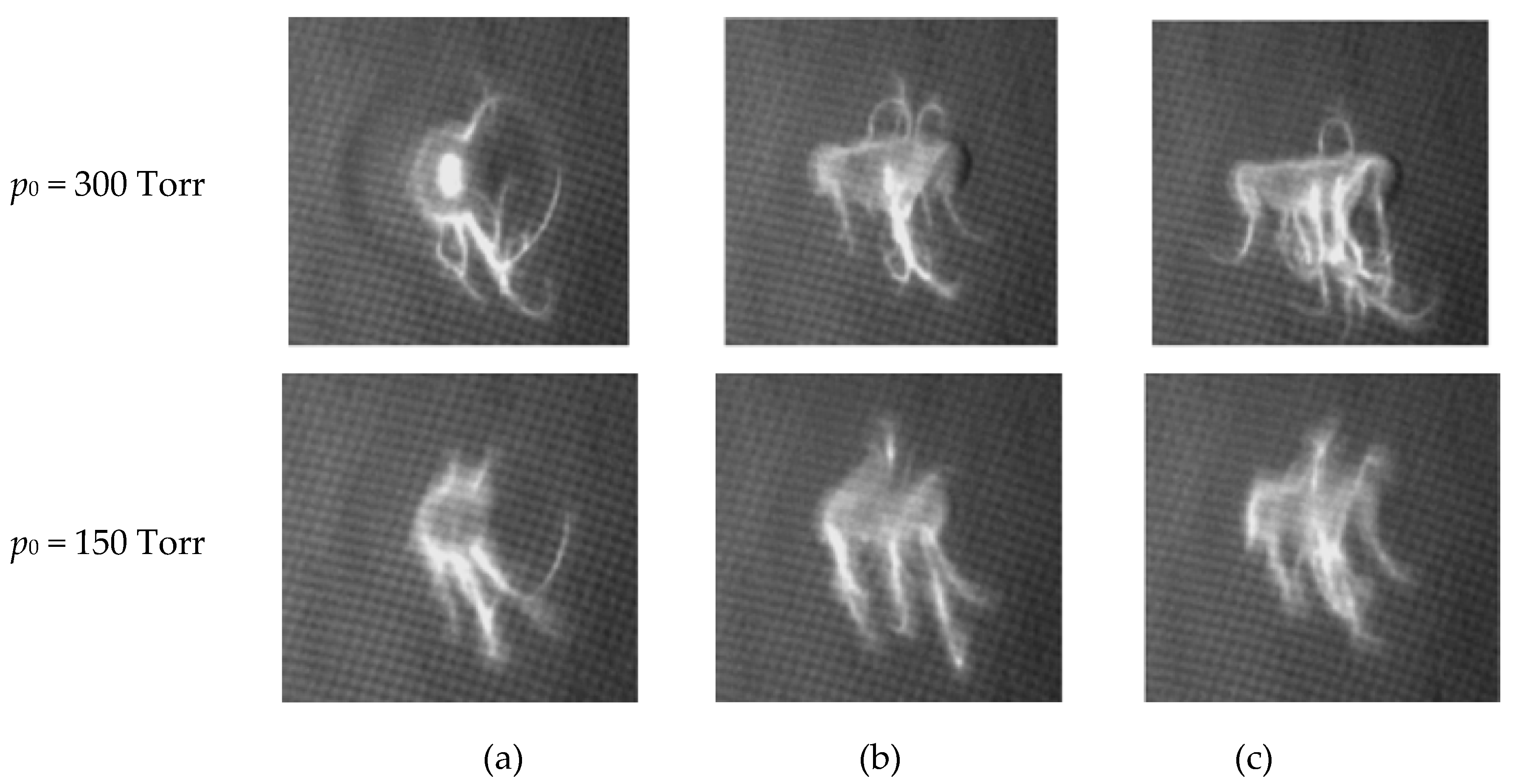

Figure 24 the MW beam characteristics are electric field voltage per centimeter E ≈ 5 kV/cm, time τMW = 4 μs, laser beam has the parameters: energy w = 370 mJ, time of action τlas = 10 ns. In

Figure 25 the MW beam characteristics are E ≈ 5 kV/cm for pressure p0 = 300 Torr and E ≈ 4 kV/cm for p0 = 150 Torr; τMW = 4 μs, laser beam has the parameters: w = 370 mJ, τlas=10ns. It was shown that under the existing MW field strength, the duration for which a LS can initiate the discharge increases with higher laser pulse energy. In addition, the significant reductions in the MW discharge initiation threshold and the duration of LS initiation capability were observed at atmospheric and reduced air pressure, which was influenced by gas-dynamic perturbations associated with the LS.

The works [75,98,99], presented by the V. Lashkov’s group, are ideologically a continuation of the previous work. The authors present experimental results on MW discharge in a supersonic flow initiated by single and double LSs, along with numerical simulations of the SW structures induced by multiple LSs in an airflow (

Figure 26). Here in the experiments the static pressure p0 = 145 Torr and freesrtream Mach number M∞ = 1.5.

The fusion of two plasma areas from the LSs into one extended region was also shown, and the mechanism of this fusion, associated with the formation of a secondary streamer between these regions, was elucidated (

Figure 27). Overall, employing various spatial and temporal arrangements of LSs within a supersonic flow, the authors demonstrated the potential for lowering the MW breakdown threshold and manipulating the shape and placement of the MW plasma.

In [100–102] the group of I. Znamenskaya presented the results on obtaining the elements of classical Riemann problem in experiment. The authors performed experiments on the study of a flow dynamics after pulse ionization of a half-space in front of a flat SW within a channel. These results, described in detail in [100,101], showed that a pulsed volumetric electric discharge initiated near the SW concentrates in front of the SW and rapidly heats the adjacent gas. The evolution of the flow pattern after the discharge was studied using shadow imaging and a high-speed camera, revealing a configuration with two shocks separated by a contact surface, reflecting the classical solution of the Riemann problem on a decay of an arbitrary discontinuity. The authors also estimated the amount of discharge energy converted to heat over the duration of the discharge.

E. Koroteeva et al. experimentally and numerically studied the flow induced by a pulsed plasma column in low-pressure quiescent air [102]. The authors used plasma sheets to pre-ionize the gas, which facilitated the formation of a volume discharge between them. The results showed that in a confined mode, this discharge effectively deposited electrical energy uniformly in a long (24 mm) and narrow (less than 2 mm radius) plasma column. It was obtained that this pulsed localized energy deposition resulted in a highly symmetric cylindrical SW that expanded at an average velocity of 550 m/s within the first 40 µs after discharge. In the performing 3D CFD simulations, the observed flow structures were accurately reproduced which provided more profound insights into the complex discharge-induced flow. Therefore, the generated SWs, whether in single or repetitive pulse modes, can be used to influence locally the high-speed flows in desired ways, provided their effects can be predicted.

In [28,29], the group of T. Lapushkina presents the results focused on the control of supersonic flows using magnetic impact in addition to plasma and electrical impacts. The study explores the potential for controlling SW configurations through plasmagasdynamic (PGD), electrogasdynamic (EGD), and magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) approaches [28]. Specifically, the effects of gas discharges with varying parameters on the standoff distance of a BSW in the supersonic flow of ionized xenon past a semi-cylinder AD body are investigated. In the PGD control method, a discharge generates a highly non-equilibrium plasma in front of the body, and the obtained experimental results showed that the BSW position changes depending on the degree of plasma non-equilibrium. In the EGD and MHD methods, a discharge was organized in the near-surface area of the nose section of the body. In these cases, changes in the BSW positions are achieved by adjusting the discharge intensity (EGD method) or by applying an external magnetic field (MHD method).

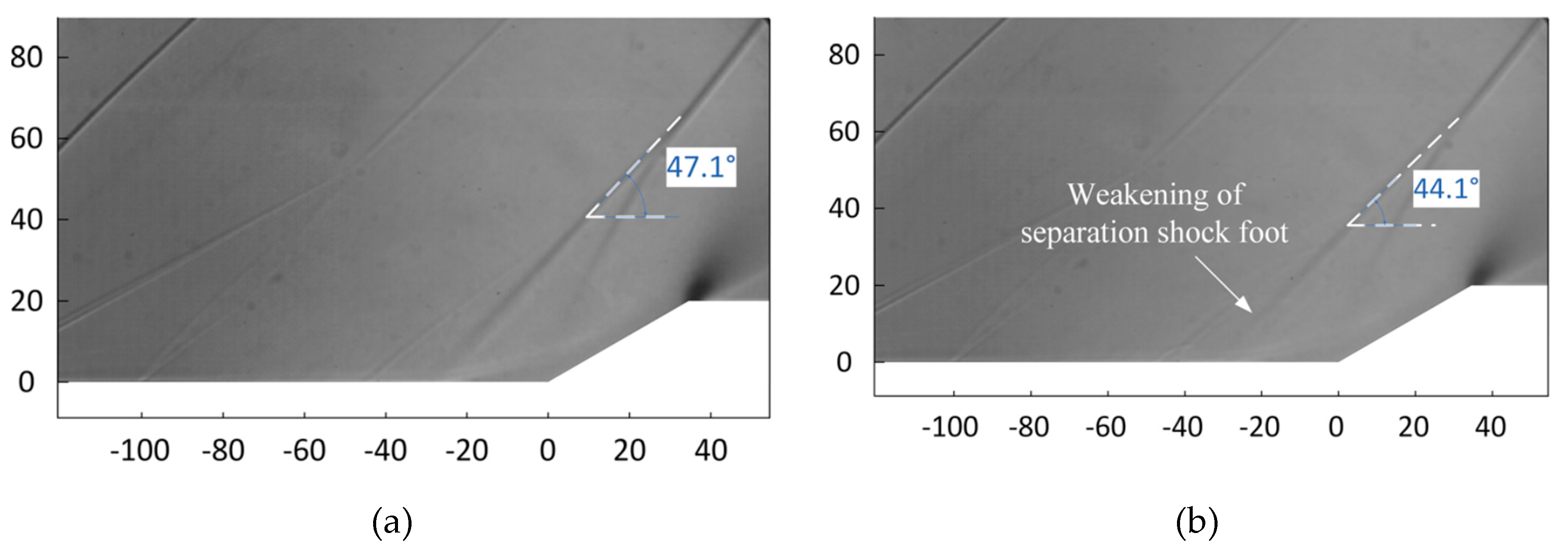

In [29] T. Lapushkina has formulated the principles of MHD control for both internal and external supersonic flows. The experiments were performed using a gas-dynamic setup based on a shock tube capable of generating a wide range of a flow Mach numbers (M∞ = 4-7). Electric and pulsed magnetic fields with intensities up to 1.5 T were applied. The results showed that changing the local application region, the intensity, and the direction of the gas discharge currents makes it possible to control the ponderomotive force acting on the gas flow during the MHD impact. This allows to control a SW shape and position, flow velocity and direction, along with the pressure changes near the surfaces of the streamlined body. The experimental flow patterns and data analysis illustrated the impact of the MHD effect on several aspects, including changing the angle of the attached SW, adjusting the BSW standoff distance, and modifying the drag and lift forces of streamlined bodies (

Figure 28 and

Figure 29). It should be underlined that a key advantage of MHD control over mechanical methods is its speed. In addition, when gas discharge flows are well organized, the MHD effects are independent of the flow velocity or angle of attack, making them suitable for a broader range of supersonic flow control applications.

In [103], P. Polivanov et al. presented an experimental and numerical study of a plasma vortex generator in a supersonic turbulent BL. This study addresses the challenge of flow control under turbulent BL conditions at transonic and supersonic speeds of the oncoming flow. The authors investigated a combined control device named by them as a “plasma wedge”, a wedge-shaped device installed in the flow. Energy is supplied to one side of the wedge by a spark discharge actuator. The flow passes over a rectangular flat plate with a sharp leading edge. The results showed that the initiation of the discharge resulted in the formation of a longitudinal vortex in the wake behind the actuator. The experimental data included the velocity distribution in the wake behind the plasma wedge actuator, the pressure distribution in the transverse coordinate, and the temperature distribution at the model surface. In addition to the flow parameters and the electrical characteristics of the discharge were also measured. The experimental results confirmed that the activation of the discharge increases the flow vorticity, demonstrating the effectiveness of such PAs. The vortex formation process was also investigated numerically, considering the location of energy release on the wedge and the role of velocity gradients in the BL. The numerical results showed that it is possible to generate a longitudinal vortex by heating the flow in the center and near the trailing edge of the wedge.

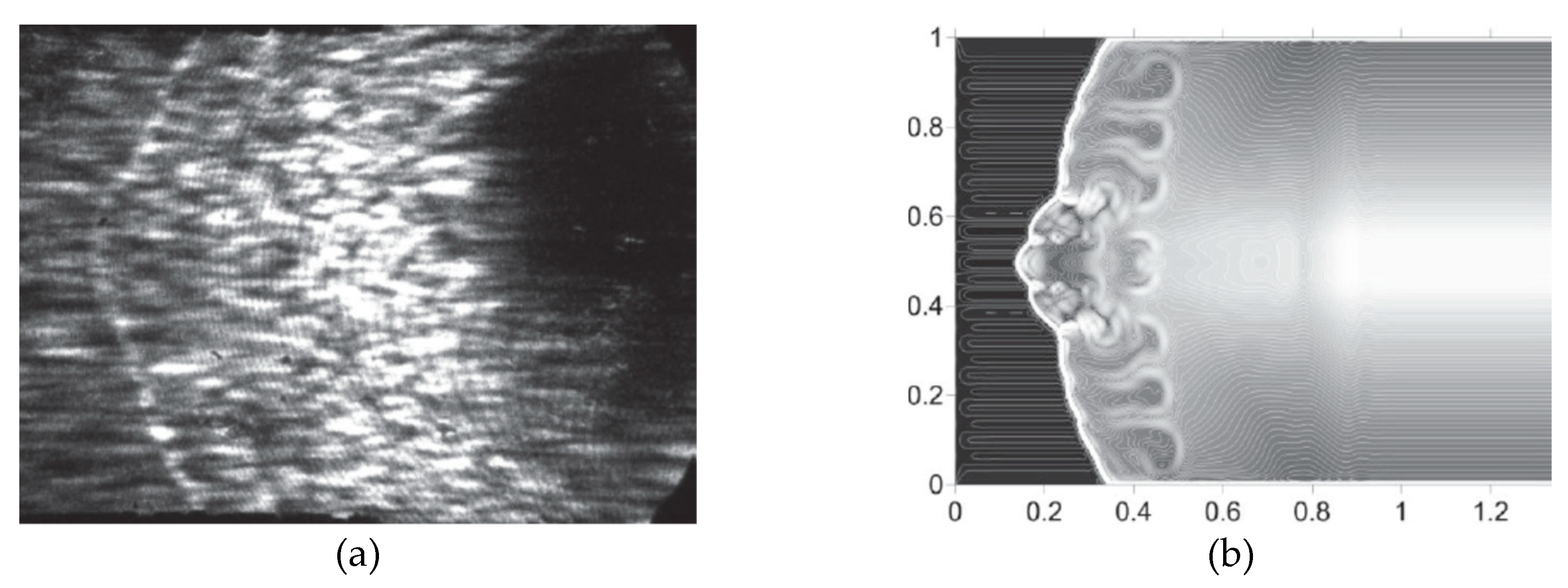

In [104–106] O. Azarova et al. studied the passage of a SW through the area of glow gas discharge plasma, conducted a comparison of thermal and plasma effects upon the characteristics of a supersonic flow past an AD body, such as a steady BSW position, as well as the properties of the streamlined body along with the characteristics of the near-surface gas discharge plasma. The authors proved the essential role of the plasma effects, in particular, the degree of ionization and the degree of non-equilibrium of the discharge plasma. Due to the interaction of the SW with the preformed gas-discharge plasma region, a new configuration of the shock wave consisting of two discontinuities is formed, which was established in the course of experiments on the passage of the shock wave through a heated ionized region formed by a gas-discharge [104]. It turned out that in the resulting configuration the convexity of the discontinuity fronts coincides with the direction of motion of the initial SW. In this case, the discontinuities observed experimentally can be interpreted as elements of the solution of the two-dimensional Riemann problem on the decay of an arbitrary discontinuity: the shock wave (SW) and the contact discontinuity (CD) that follows it (

Figure 30). Also, it was found that the shape of the fronts and absolute values of velocities of emerging discontinuities depend on the value of the ratio if specific heats γ.

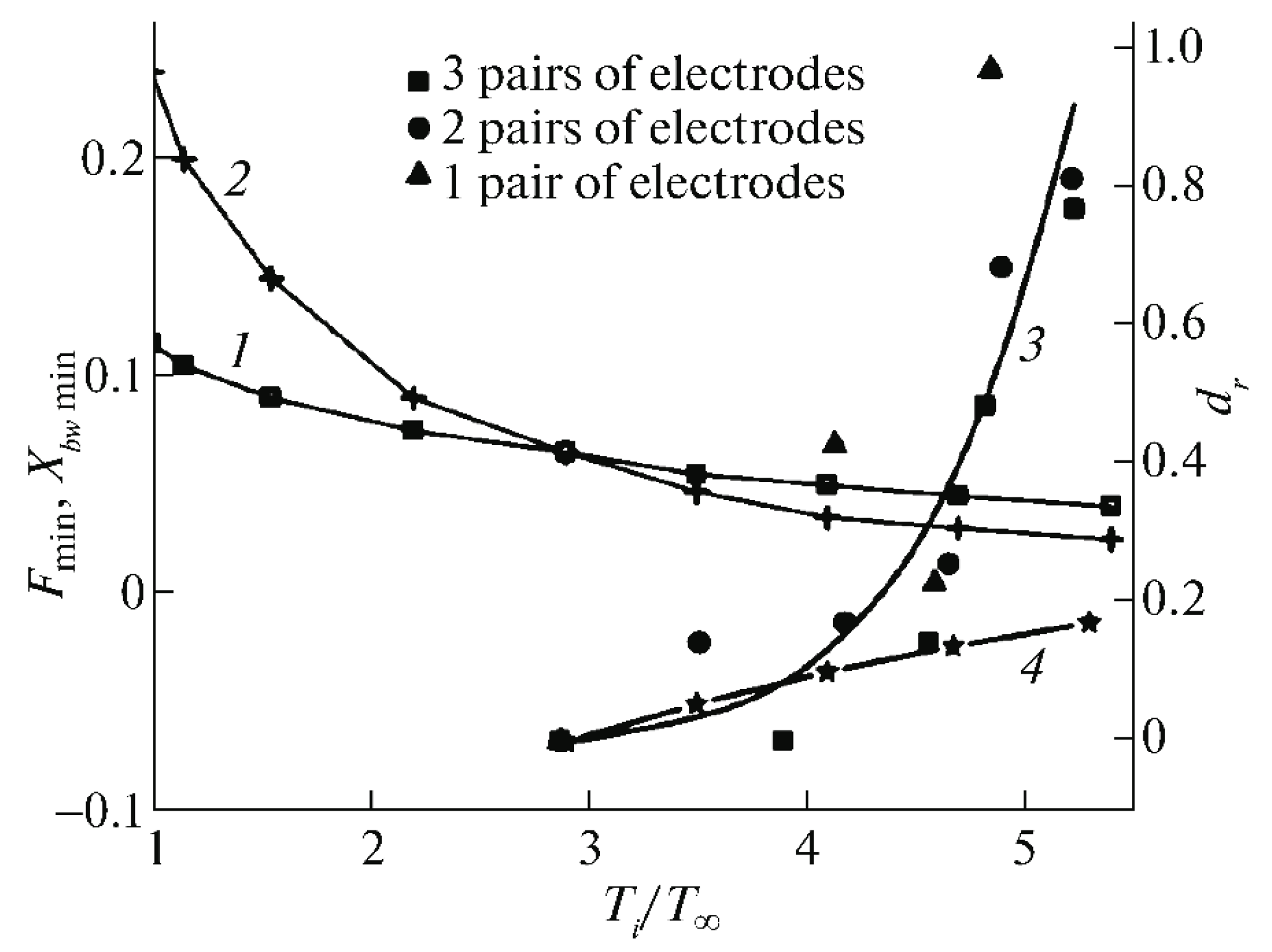

Numerical modeling of the thermal effect of plasma on the shock layer of a homogeneously heated region with the gas temperature equal to the electron temperature determined in the experiment for the flow parameters used in the experiment was performed in [105]. The analysis of the calculations and their comparison with experimental data leads to conclude that there is a plasma effect (as opposed to thermal exposure only) on the supersonic flow past an AD body, which increases nonlinearly with the increasing degree of non-equilibrium of gas discharge plasma in a wide temperature range (

Figure 31).

Here F is the relative frontal drag force, Xbw is the BSW coordinate, Dexp is the averaged (over all experiments with various numbers of electrode pairs) relative BSW standoff distance from the AD body (vs. degree of non-equilibrium in the oncoming flow for Ti = Te), Dnum is the calculated BSW standoff.

The study in [106] is devoted to the control of the BSW in a Mach 4 supersonic airflow around a semi-cylindrical body using a surface gas discharge. In the experiments the increasing the discharge power in the plasma region increased the BSW standoff distance within certain power and current ranges. In the accompanying calculations it was found that the plasma parameters such as the degree of ionization and the degree non-equilibrium influence the position of the steady BSW (as well as the characteristics of the AD body). A mechanism based on non-steady processes during a steady flow formation was obtained which explained the change of the BSW position due to its interaction with the pre-existing plasma zone created by the discharge. Thus, the study demonstrates the potential to control the BSW position and AD body characteristics by creating a plasma region using a surface gas discharge on the front surface of the body.

9. High-speed flow control using thermal longitudinal layered plasma structures

This part is devoted to the numerical prediction of the possibilities of a high-speed flow control using thermal longitudinal layered plasma structures. These structures are modelled as sets of heated layers – thermally stratified energy sources (TSS). The simulations are based on the complex conservative difference schemes ([107] by O. Azarova). The experimental and numerical results on the SW curvature and blurring are considered up to the complete disappearance of the SW fronts due to multiple manifestation of the RMI. In addition, the results on the impact of TSS on BSW and AD characteristics of a body were examined including the formulation of principles of high-speed flow control using TSS. These principles include both transient and steady-state flow control inducing the possibilities of initiation and suppressing self-consistent flow pulsations and drag/lift control. Finally, the results on the noise impact on the ground during flow control using TSS are analyzed.

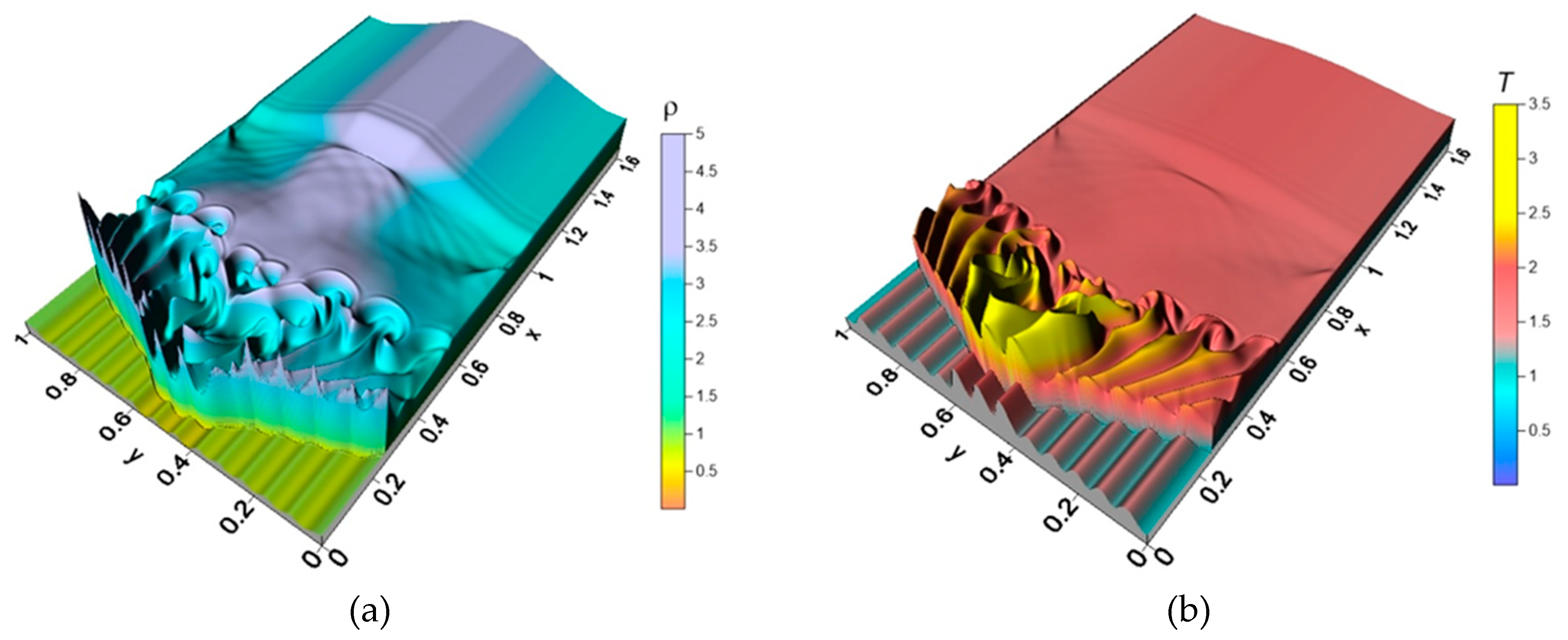

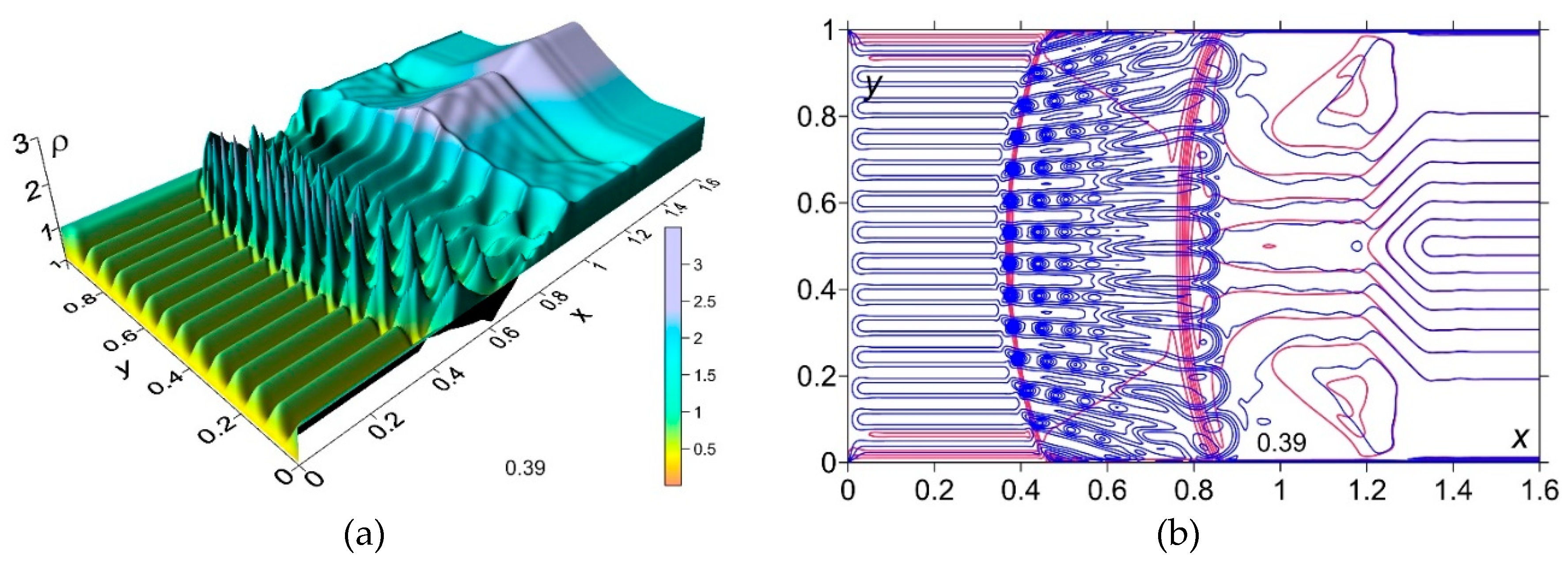

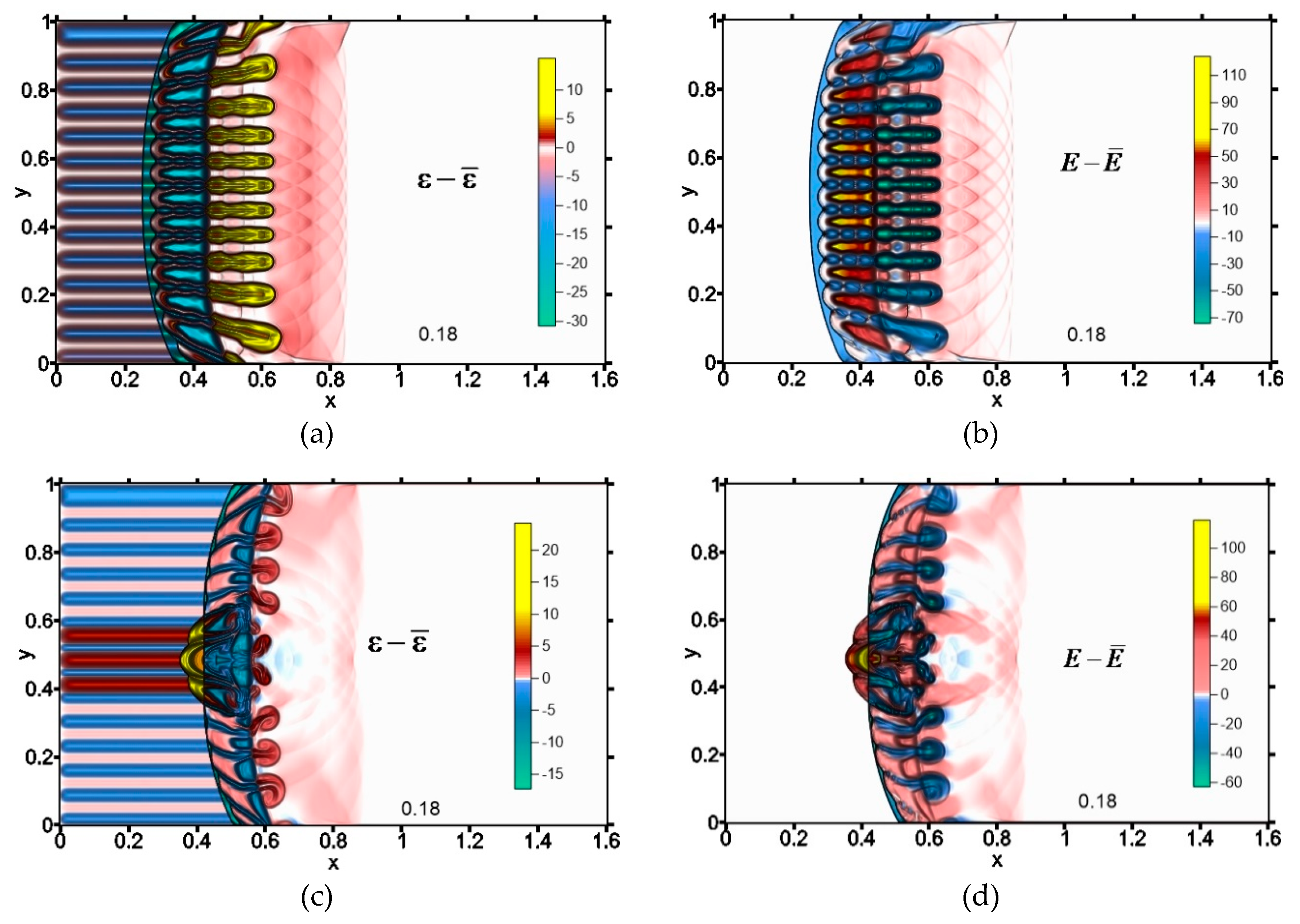

In [108–110] O. Azarova et al. examined the energy transformations accompanying the SW distortion and disappearance during the interaction with TSS, redistribution of energy in a viscous heat-conductive medium during this interaction including the consideration of these processes at hypersonic speeds. The study in [108,109] investigates the interaction of a planar SW with ionization layers from a glow gas discharge, focusing on energy transformation using numerical methods. Gas layer temperatures in ionization-unstable plasma are studied, and the energy transfer between layered energy deposition and the heated gas zone behind the SW is investigated. Experimental and numerical results showed that ionization unstable discharge plasma distorts or even erase a pre-planar SW. It was shown that the layered energy deposition distorts the SW front as the result of the multiple RMI manifestation and creates zones of increased internal and kinetic energy. Overall, the energy transfer calculations showed that structuring releases energy into layers while maintaining total and average internal energy, distorting the SW front and creating high energy zones (

Figure 32 and

Figure 33). These effects are more pronounced at higher temperatures in the layered energy source and higher SW Mach numbers.

The study examining the complex interaction between SWs and TSSs, focusing on their influence on SWs in the Mach number range from 6 to 12 is presented in [110]. A notable finding is the emergence of the RMI, leading to the SW front and contact discontinuity front blurring or vanishing within density fields. The simulations are validated against experimental data at Mach number 6, confirming their reliability. The authors also evaluate the efficiency of stratified energy sources compared to homogeneous sources (designated by index

h) of the same total energy (

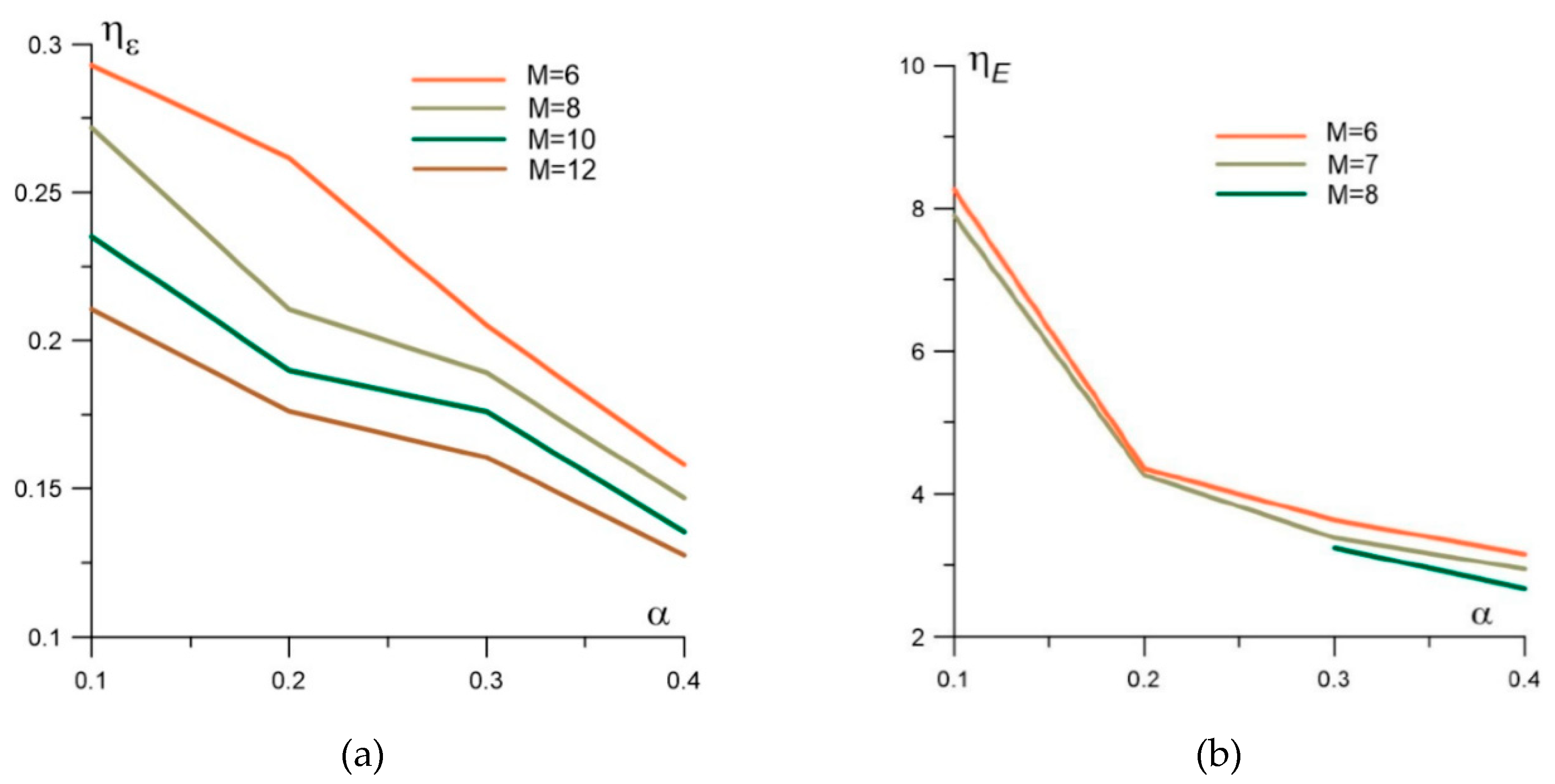

Figure 34):

Here ε is the internal energy of a gas and E is the volume kinetic energy.

TSSs are found to be superior, producing localized zones with significantly elevated specific internal energy and volume kinetic energy levels, up to 29% and 8.3 times higher, respectively, than homogeneous sources, with larger differences at lower rarefaction parameters and higher Mach numbers. These results have practical implications, suggesting that specific energy attributes within the SW structures, particularly in the hypersonic context, can be precisely controlled by strategically adjusting the rarefaction parameter or temperature profiles within the layers of the TSS, offering potential advances in supersonic and hypersonic flow control for various applications.

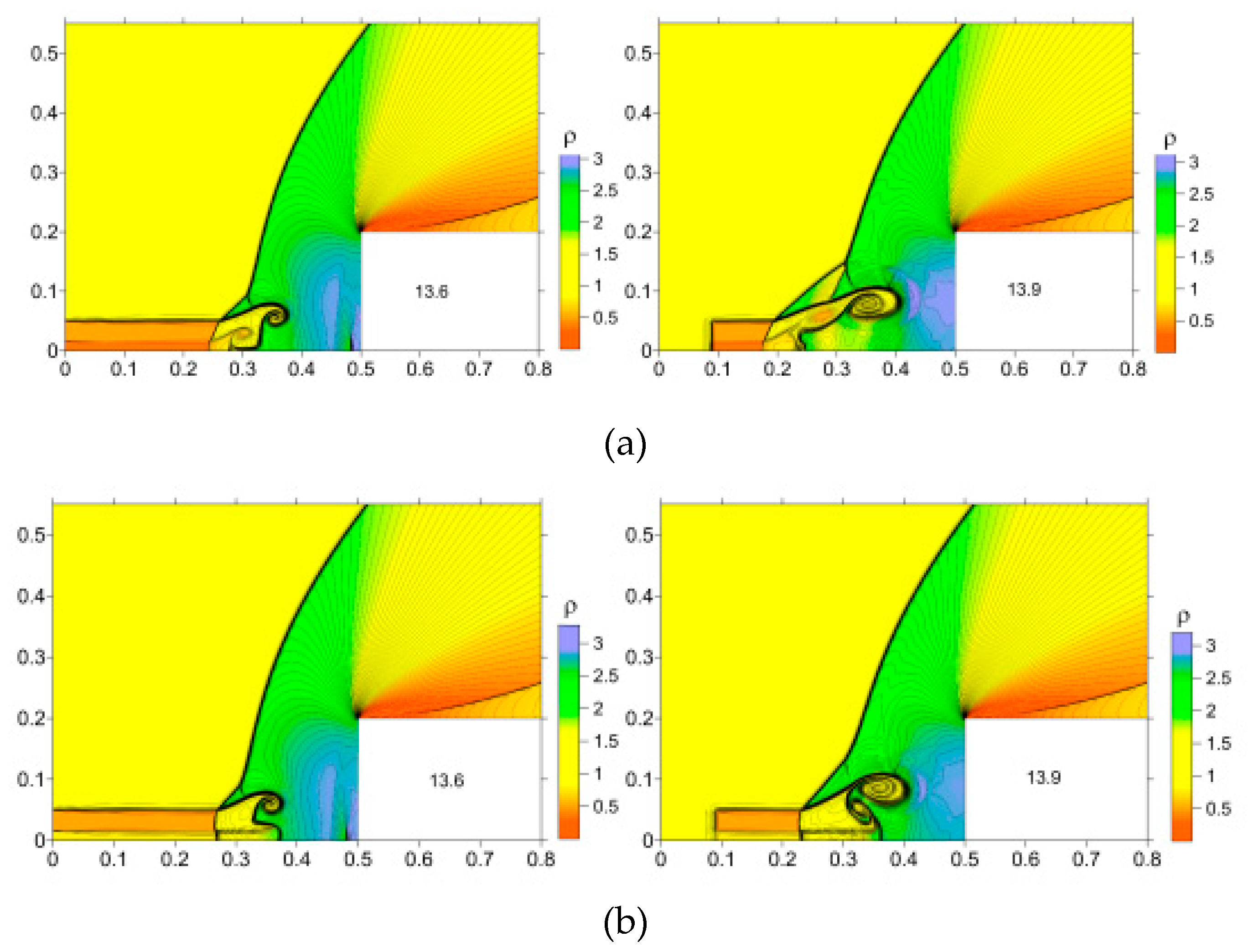

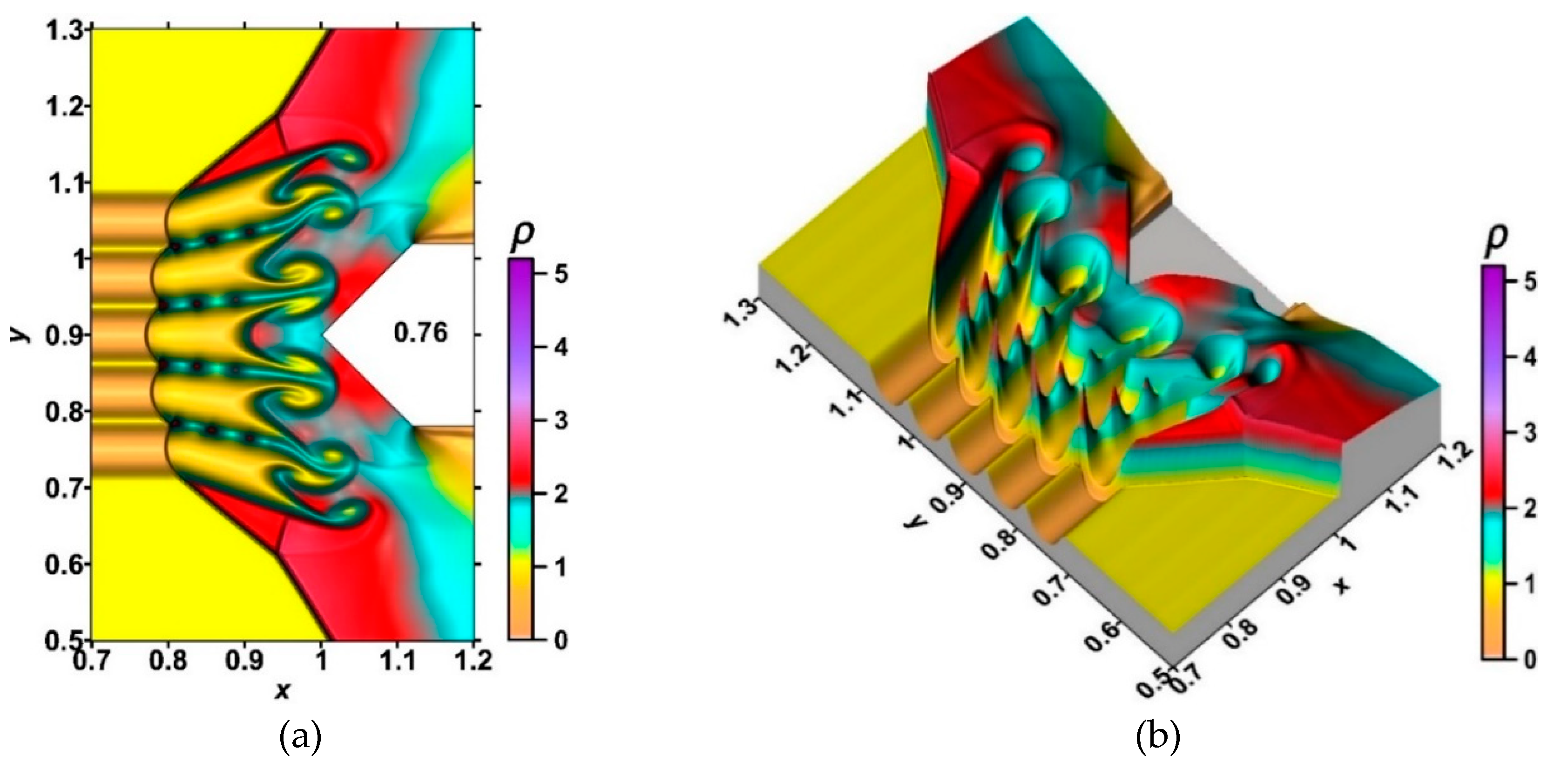

In [111–114] O. Azarova et al. investigated the impact of a TSS on the BSW and AD characteristics of a streamlined body. Principles of unsteady high-speed flow control including the control of BSW, drag and lift forces, and the flow stability using the TSSs were formulated. In [111], the study reveals the emergence of multiple RMIs leading to the almost complete disappearance of the BSW front within the source region and introduces a novel multi-vortex mechanism affecting the streamlined body (

Figure 35).

The research analyzes key parameters and compares the effects of stratified and homogeneous energy sources with equal total energy. In particular, the results highlight the potential for significant reductions in the temperature at the double-wedge vertex and the average front surface temperature due to energy redistribution into layers. In supersonic flow past a double-wedge pointed plate at M∞=2, the study distinguishes the effect of a TSS, showing that it leads to a substantial reduction in the stagnation temperature and the average frontal surface temperature compared to a homogeneous source with similar total energy and spatial characteristics.

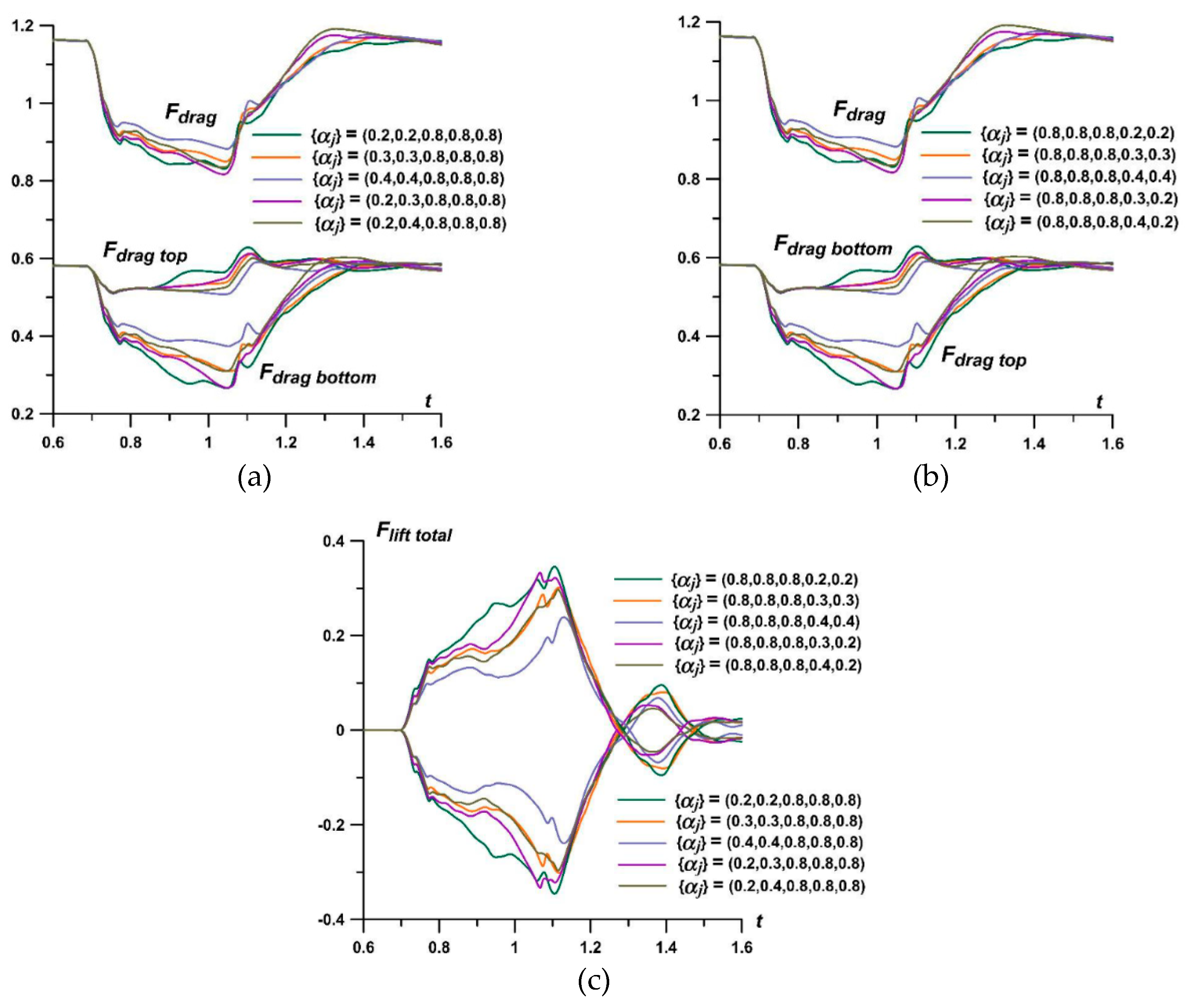

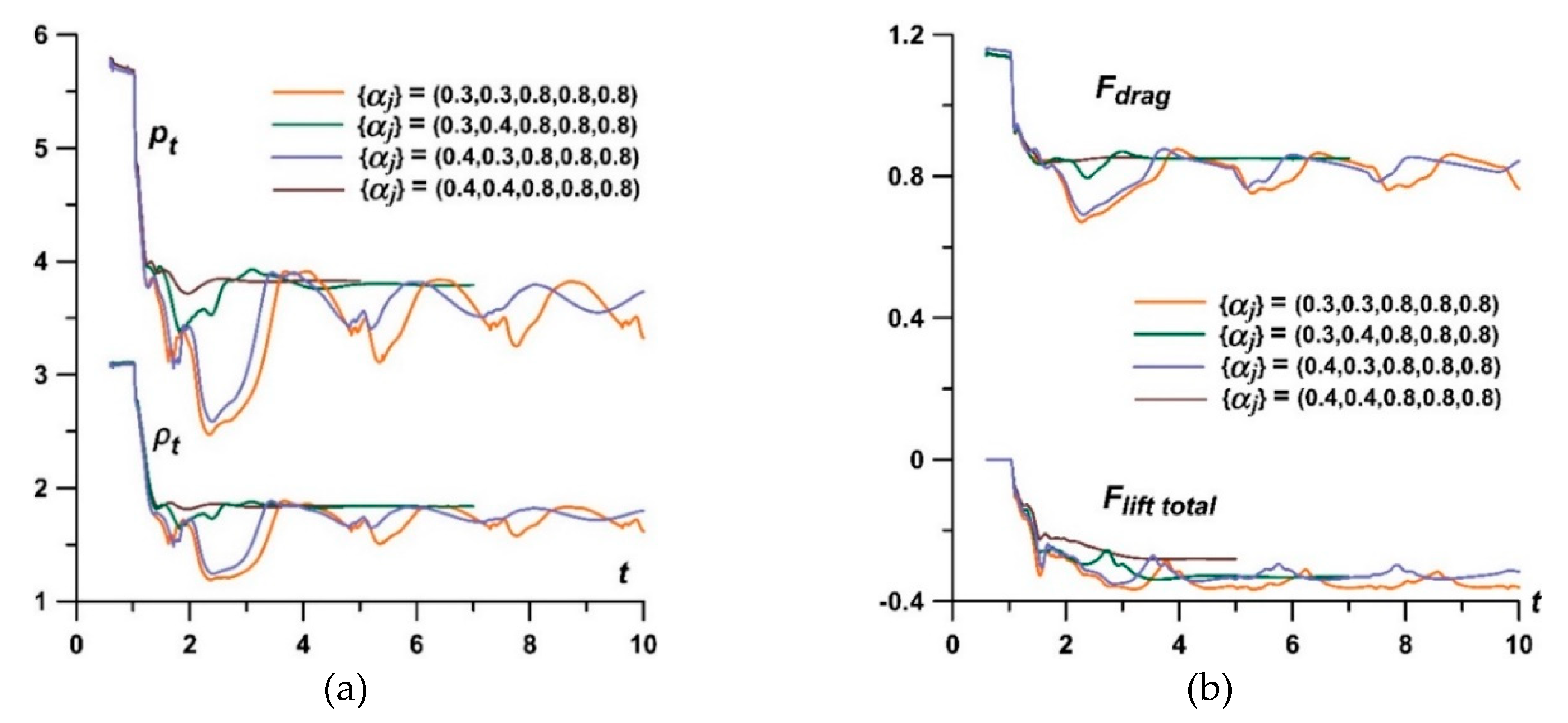

In [112,113] the study investigates the dependence of frontal drag and lift forces on temperature variations within the source layers. Every heated layer is supposed to have a decreased density and is characterized by a rarefaction parameter α which means, taken to account that the pressure is supposed to be constant, that the temperature is increased in the layer. The TSS is characterized by a set of rarefaction parameters in its layers. By changing the temperature distribution within these layers, more intense vortices accompanying the RMI can be achieved, temporarily reducing the drag force and inducing transient changes in the lift forces. In [112], the principles of temporary supersonic flow control by layered energy sources are elucidated, including the ability to manipulate the rate of change of drag and lift forces, with lower

αj (higher temperatures) in the TSS layers and larger density differences yielding more substantial effects (

Figure 36).

The study in [113] presents a novel method for high-speed flow control using a continuously active TSS. The research explores the relationship between steady supersonic flow, aerodynamic body characteristics, and temperature variations within the layers of the TSS. Detailed visualization of density, pressure, temperature, and local Mach number fields was carried out to analyze the controlled establishment of steady flow modes under the action of a TSS. Multiple RMI are observed, resulting in significant perturbation of the BSW front within the source layers and sharp peaks initiation (

Figure 35).

Key findings include the wavy nature of the bow shock front, influenced by the source stratification, and the larger BSW separation distance at lower

αj values (higher temperatures) in the layers. By changing the temperatures within the symmetric sets {

αj}, control over flow parameters, pressure, density, and drag is achieved. Asymmetric sets {

αj} can induce pulsating flow modes, with mechanisms for self-sustained pulsations described. The ability to suppress these flow pulsations by changing temperature settings was demonstrated. The study also considered the ability of lift (pitch) forces initiating and control (

Figure 37). These results provide a novel approach which can give valuable insights into dynamic flow control using thermally stratified energy sources (TSSs).

The issue of noise reduction (Sonic Boom problem) in supersonic aircraft design is critical and has a significant impact on the development of supersonic aviation. In [115] M. Park and M. Nemec provided an overview of noise generation research, explicitly addressing the Sonic Boom problem in supersonic flows/flights. The authors summarized the studies presented at the Second AIAA Sonic Boom Workshop.

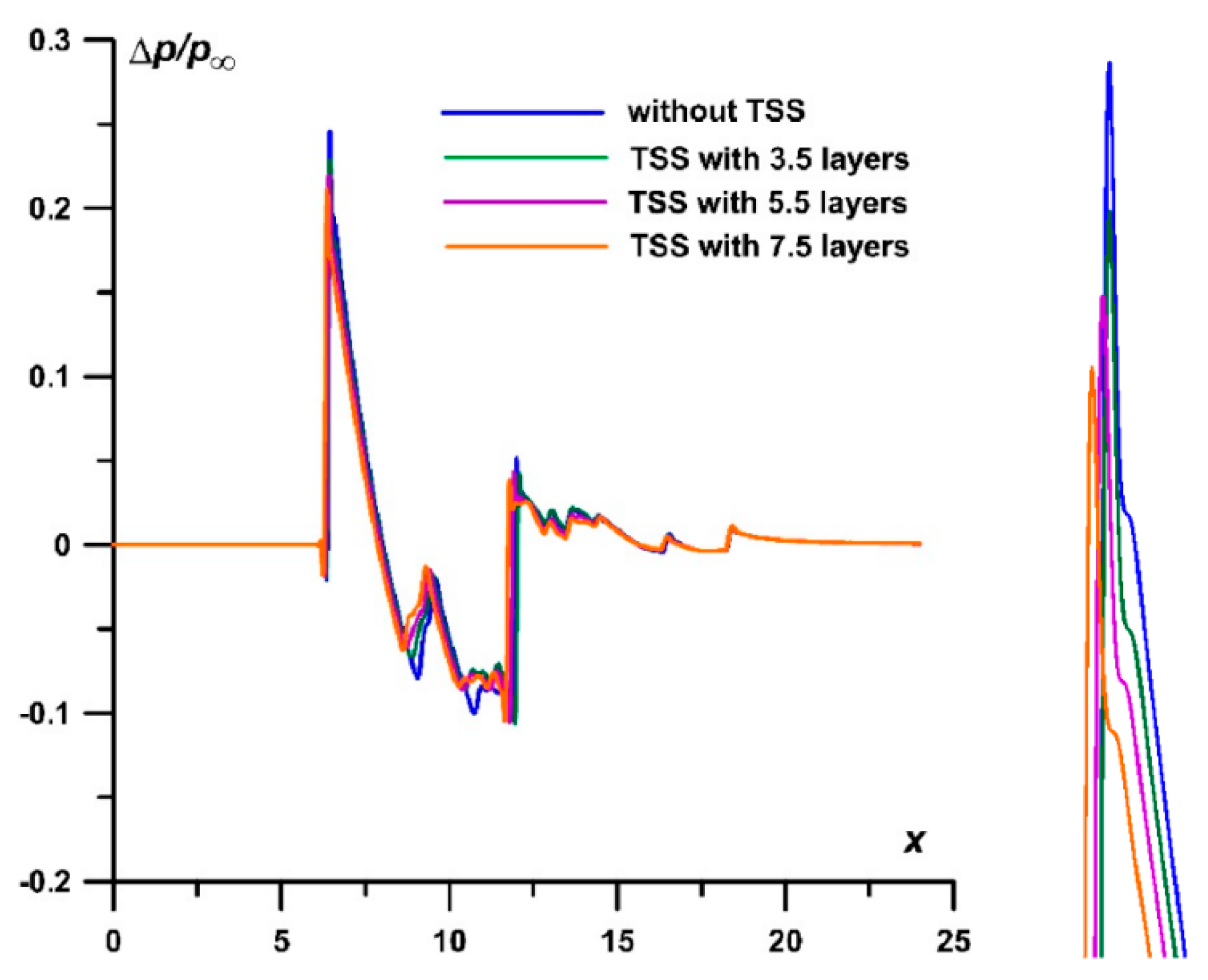

The study in [114] by O. Kravchenko et al. devoted to noise generation during civil supersonic aircraft flights, focusing on the influence of a TSS used to control a supersonic flow past an aerodynamic model of a pointed cylinder. The authors evaluate near-field and ground pressure signatures and perceived sound level in decibels (PLdB) on the ground. Complex conservative difference schemes [107], C. Tomas’ waveform parameter method described in [116], and S. Stevens’ Mark VII algorithm presented in [117] are used for near-field modeling, ground pressure signature analysis, and PLdB evaluation. When the flow is controlled by varying the temperature in the TSS layers and the number of layers in the TSS, some pressure reduction is observed at the BSW front and in the nearfield and ground pressure signatures. At the same time, these values do not exceed the pressure values for flow without TSS action (

Figure 38).

Therefore, the simulations showed that no additional noise is introduced onto the ground when controlling the flow with the use of TSS. In addition, in a broader sense, the modeling showed that changing the surface pressure and reducing drag does not necessarily imply a change in the PLdB at the ground.

10. Conclusion