3.1. CALPHAD calculations

The content of thermodynamically stable phases as a function of oxygen activity (

aO) for all investigated steel grades at 650 °C is shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

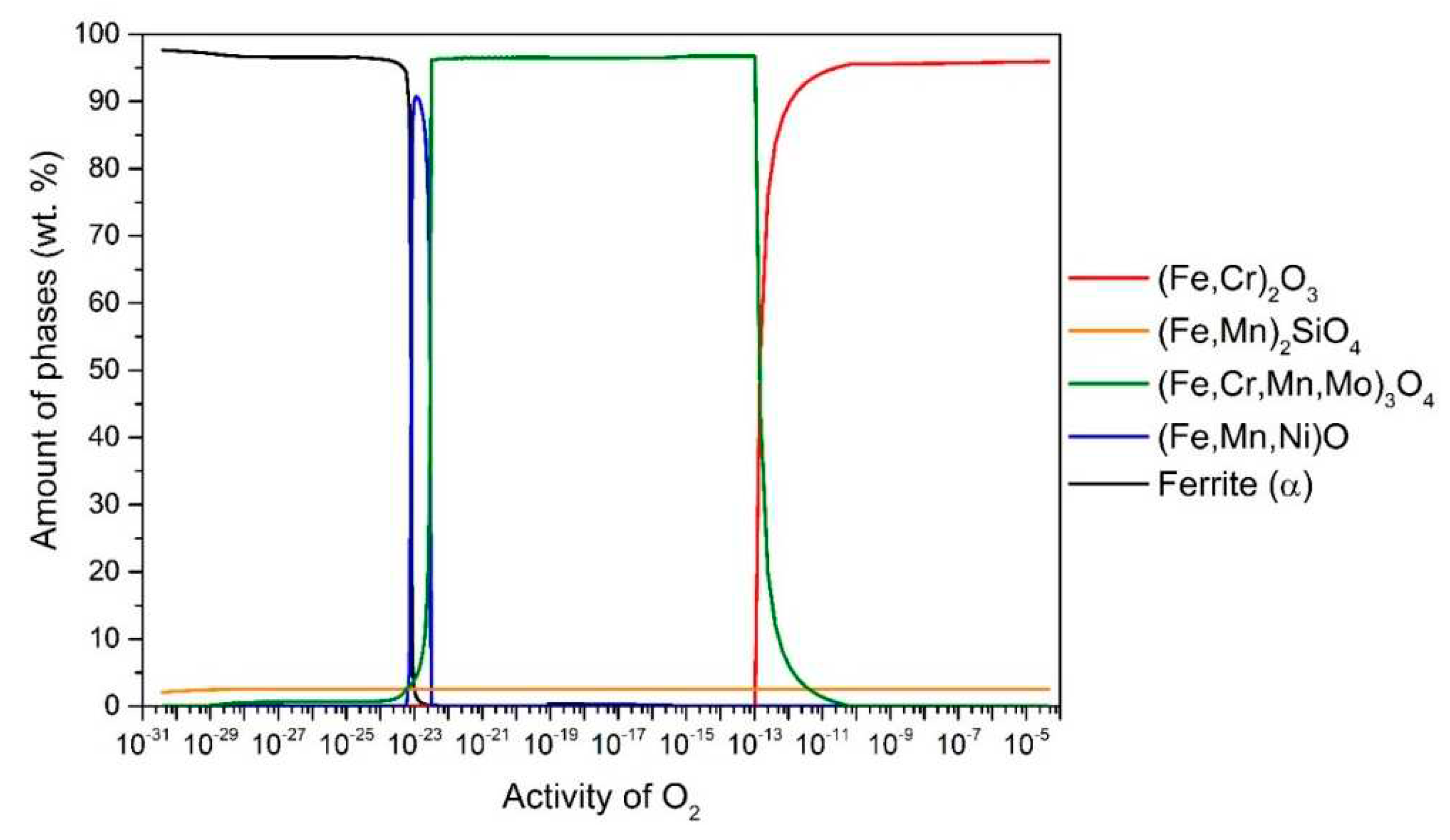

Figure 1 shows the results for the steel 16Mo3. According to this at 650 °C up to

aO ≈ 10

–13, the stable oxide (Fe, Cr)

2O

3 (95.9 wt.%) predominates, followed by (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 (2.8 wt.%) and the remaining 1.3 wt.% is (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4. In the range

aO ≈ 10

-13–10

-23, (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4 is stable and predominant (96.7 wt.%), followed by (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 (3.3 wt.%) and in the range

aO ≈ 10

-22–10

-23 (Fe, Mn, Ni)O (the content increases to 90.7 wt.%) and the rest is (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4 and (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 (but the content of these two changes with

aO according to the wüstite content). It is also observed that internal oxidation occurs at 650 °C, so that (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4 and (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 are stable under the steel surface. In all cases, internal oxidation was determined by the amount of α-ferrite phase, as the α-ferrite content calculated at equilibrium at a temperature of 650 °C is 97.5 wt.%. Therefore, we can determine whether internal oxidation takes place or not. If the α-ferrite content increases (black line), it should immediately increase to 97.5 wt.%, if not, internal oxidation takes place, as shown in

Figure 1.

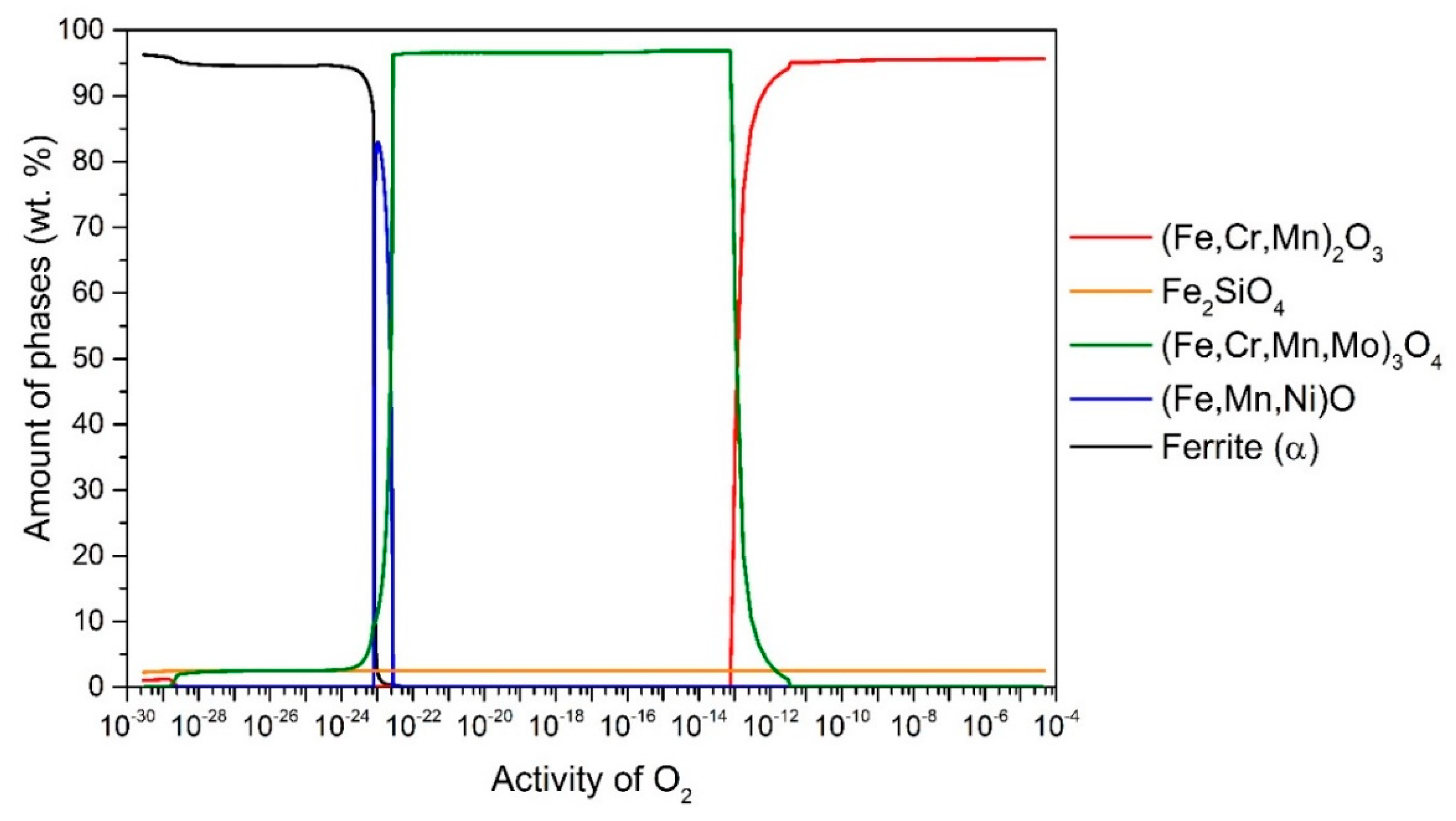

Figure 2 shows the results for 13Cr steel. Thus at 650 °C up to

aO ≈ 10

–13, the stable oxide (Fe, Cr, Mn)

2O

3 (95.6 wt.%) predominates, followed by Fe

2SiO

4 (4.4 wt.%). In the range

aO ≈ 10

-13–10

-22, (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4 is stable and predominant (96.7 wt.%), followed by Fe

2SiO

4 (3.3 wt.%) and in the range

aO ≈ 10

-22–10

-23 (Fe, Mn, Ni)O (the content of which increases up to 83 wt.%) and the remainder is (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4 and Fe

2SiO

4 (but the content of these two changes with

aO according to the wüstite content). It is also observed that internal oxidation occurs at 650 °C, so that (Fe, Cr, Mn, Mo)

3O

4 and Fe

2SiO

4 are stable under the steel surface. In all cases, the internal oxidation was determined by the amount of α-ferrite phase, as the equilibrium calculated α-ferrite content at 650 °C is 97 wt.%. Therefore, we can determine whether internal oxidation occurs or not. If the α-ferrite content increases (black line), it should immediately increase to 97 wt.%. If not, internal oxidation takes place, as shown in

Figure 2.

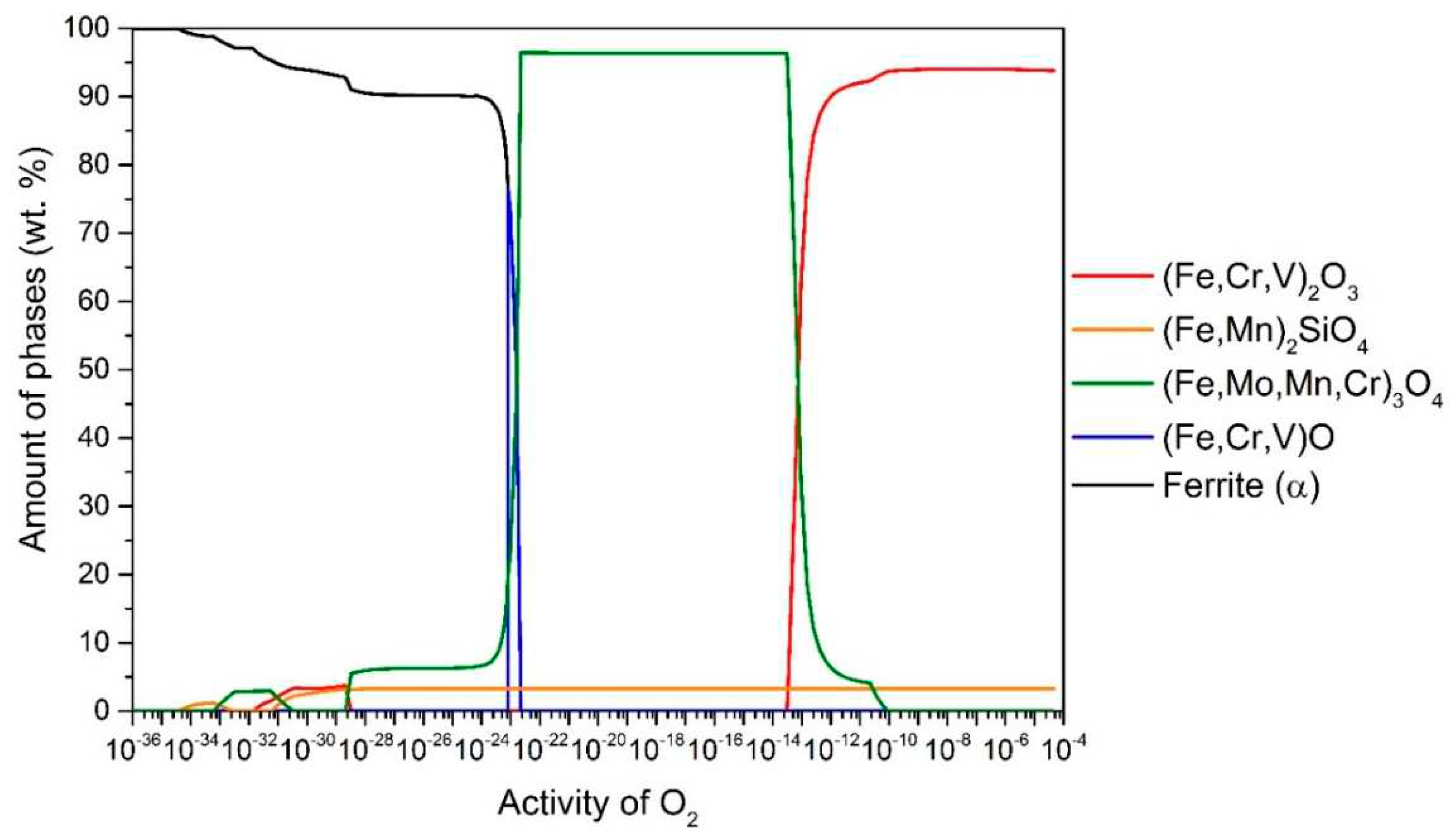

Figure 3 shows the results for T24 steel. At 650 °C up to

aO ≈ 10

–13, the stable oxide (Fe, Cr, V)

2O

3 (94.3 wt.%) predominates, followed by (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 (5.7 wt.%). In the range

aO ≈ 10

-13–10

-22, (Fe, Mo, Mn, Cr)

3O

4 is stable and predominant (96.7 wt.%), followed by (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 (3.3 wt.%) and in the range

aO ≈ 10

-22–10

-23 (Fe, Cr, V)O (the content of which increases up to 76.4 wt.%) and the rest is (Fe, Mo, Mn, Cr)

3O

4 and (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 (but the content of these two changes with

aO according to the wüstite content). It is also observed that internal oxidation occurs at 650 °C, so that (Fe, Mo, Mn, Cr)

3O

4, (Fe, Mn)

2SiO

4 and (Fe, Cr, V)

2O

3 are stable under the steel surface. In all cases, internal oxidation was determined by the amount of α-ferrite phase, as the equilibrium calculated α-ferrite content at the temperature of 650 °C is 98.5 wt.%. Therefore, we can determine whether internal oxidation occurs or not. If the α-ferrite content increases (black line), it should immediately increase to 98.5 wt.%, otherwise, internal oxidation occurs, as shown in

Figure 3.

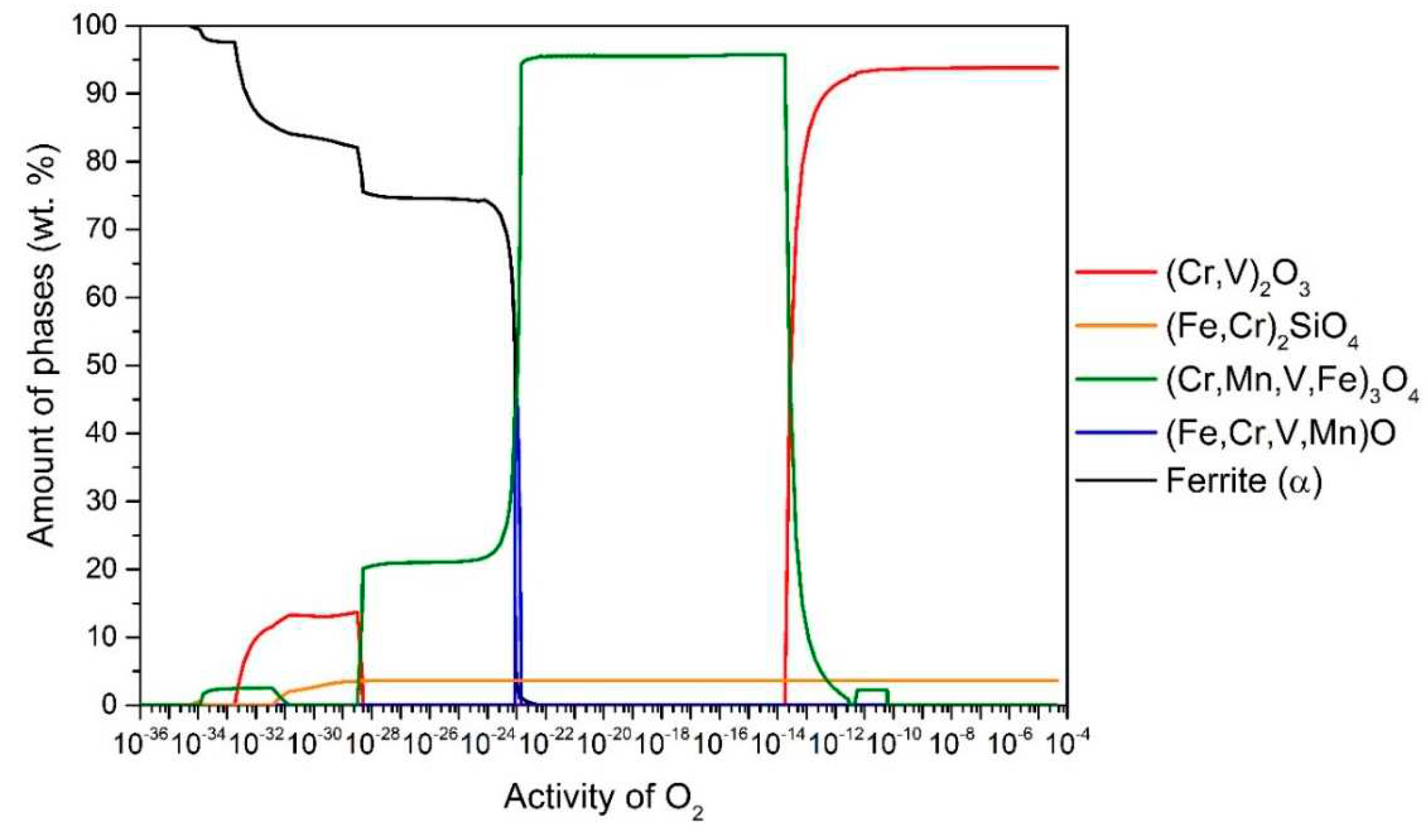

Figure 4 shows the results for the steel P91. According to this at 650 °C up to

aO ≈ 10

–14, the stable oxide (Cr, V)

2O

3 (94.2 wt.%) predominates, followed by (Fe, Cr)

2SiO

4 (5.8 wt.%). In the range

aO ≈ 10

-14–10

-22, (Cr, Mn, V, Fe)

3O

4 is stable and predominant (96.1 wt.%), followed by (Fe, Cr)

2SiO

4 (3.9 wt.%) and in the range

aO ≈ 10

-23–10

-24 (Fe, Cr, V, Mn)O (the content of which increases up to 45.8 wt.%) and the rest is (Cr, Mn, V, Fe)

3O

4 and (Fe, Cr)

2SiO

4 (but the content of these two changes with

aO according to the wüstite content). It is also observed that internal oxidation occurs at 650 °C, so that (Cr, Mn, V, Fe)

3O

4, (Fe, Cr)

2SiO

4 and (Cr, V)

2O

3 are stable under the steel surface. In all cases, internal oxidation was determined by the amount of α-ferrite phase, as the equilibrium calculated α-ferrite content at the temperature of 650 °C is 97.8 wt.%. Therefore, we can determine whether internal oxidation occurs or not. If the α-ferrite content increases (black line), it should immediately increase to 97.8 wt.%, otherwise, internal oxidation occurs, as shown in

Figure 4.

3.2. Thermogravimetric analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was used to measure the change in weight of the steels studied during high-temperature oxidation, as this is the most common method for studying the oxidation rate and can be measured continuously or discontinuously [

16]. An iterative rectangular distance regression algorithm was used for the best fit of the TGA results to the mathematical functions. A two-phase exponential growth function (equations (1)), a second-degree polynomial (equation (2) - parabolic law) and a third-degree polynomial (equation (3) - cubic law) were used to describe the curves (TGA results).

In all cases, t is the time in s, Δm is the change in weight in mg, A is the specific surface area of the sample in cm2, while the other coefficients depend on the temperature and the chemical composition of the steel.

However, since oxidation kinetics is usually studied by a change in mass as a function of oxidation time, a parabolic law can be expressed by the Pilling-Bedworth equation [

17,

18]:

Where

W is the change in mass per unit area due to oxidation of iron and

kp (=

) is the parabolic constant in g

2 cm

-4 sec

-1, and

W0 is the initial mass at the time (

t = 0) of parabolic oxidation. In the original Pilling-Bedworth equation [

18],

W0 is equal to 0. The most suitable method to obtain the equation for calculating the rate constant for the oxidation of steel during continuous heating or cooling was developed by Kofstad [

19]. According to his interpretation, oxidation following a linear, parabolic, or cubic law can be generally expressed as follows:

where

W is defined as the change in mass per unit area over time

t,

n is a constant with values of 1, 2, or 3 for the linear, parabolic, or cubic law, and

kn is a time-independent rate constant expressed as:

Where B is the constant, T is the absolute temperature, R is the gas constant, and Q is the activation energy.

The rate constants were calculated for all samples studied after equation (5) was derived by simple linear regression. The basic equation for the calculation of the rate constant (

kn) is as follows:

Where Δm is the change in weight in mg, A is the specific surface area in cm2, t is the oxidation time in s, and kn is the rate constant, where n can be 1, 2, or 3, respectively, in the case of a linear, parabolic, or cubic law. In the case of the exponential law, 1 < n < 3. The index n was named after the type of equation, so that the exponential law has the index e and the cubic law the index c.

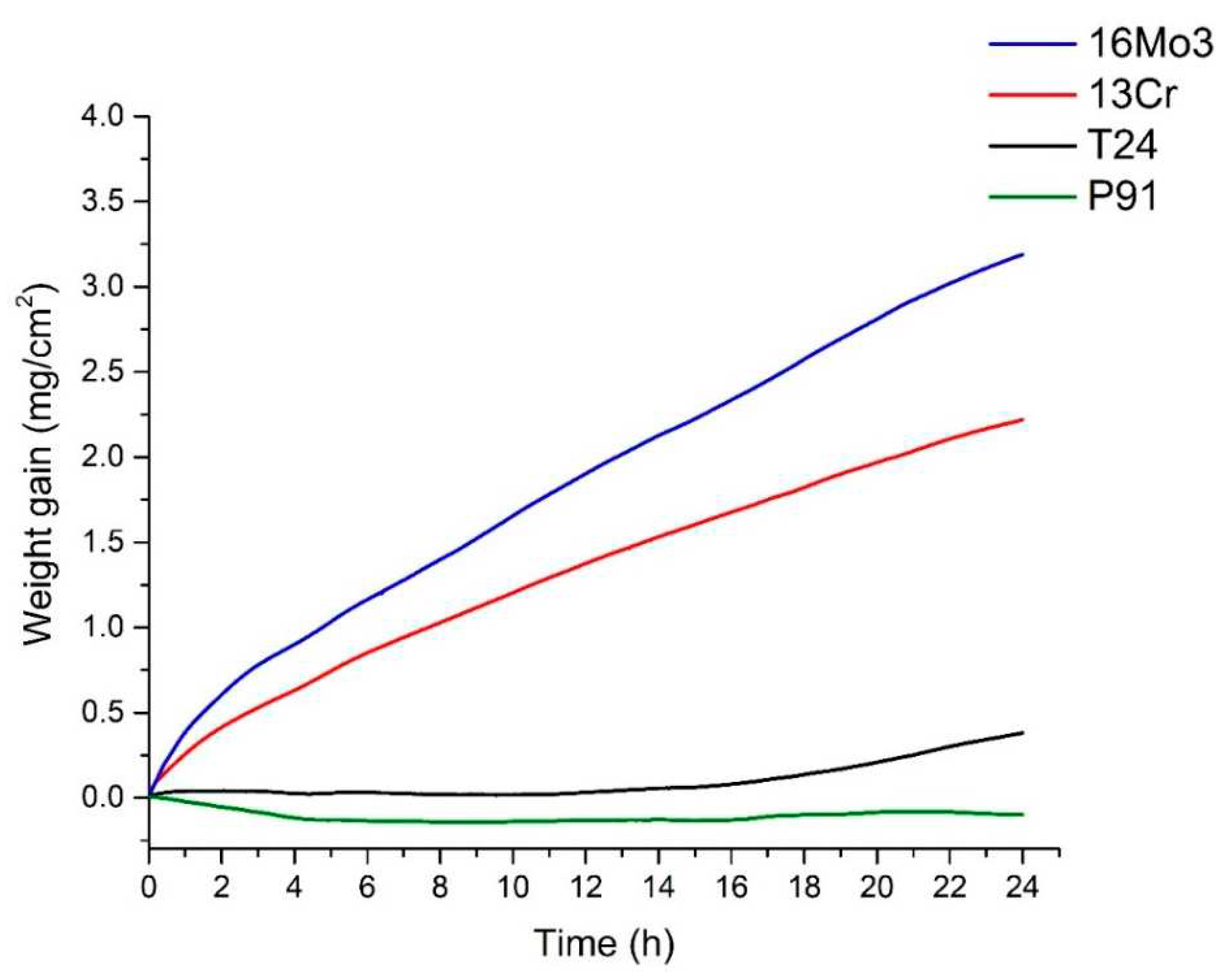

The following graph (

Figure 5) shows the TGA results of the steels examined. After 4 hours, the oxidation kinetics of steel 16Mo3 starts to follow a parabolic law and the TGA results can be expressed with a parabolic equation, but overall, the best fit is still the exponential equation. For steel 13Cr, the same trend is observed but it seems to be faster as the oxidation kinetics starts to follow a parabolic law after 2 hours. On the other hand, the oxidation kinetics of steel T24 follows the cubic law. The oxidation kinetics of steel P91 can be described by the cubic law, as the TGA results agree best with the cubic equation. In a study on the high-temperature oxidation behaviour of P91 steel [

20], it was suggested that it follows a parabolic law (at 600 °C and 700 °C). We cannot confirm this, but on the other hand its oxidation time was 1000 hours. We assume that this is the same trend as for the 16Mo3 and 13Cr steels in this study.

The equation types with the corresponding coefficients that best fit the TGA results are listed in

Table 2.

The calculated results of the rate constants are shown in

Table 3. The results of the rate constants are a clear indication that the oxidation kinetics is fastest for 13Cr steel, followed by 16Mo3, T24 and P91. This means that 13Cr steel oxidises the most and P91 the least.

3.3. Microscopy

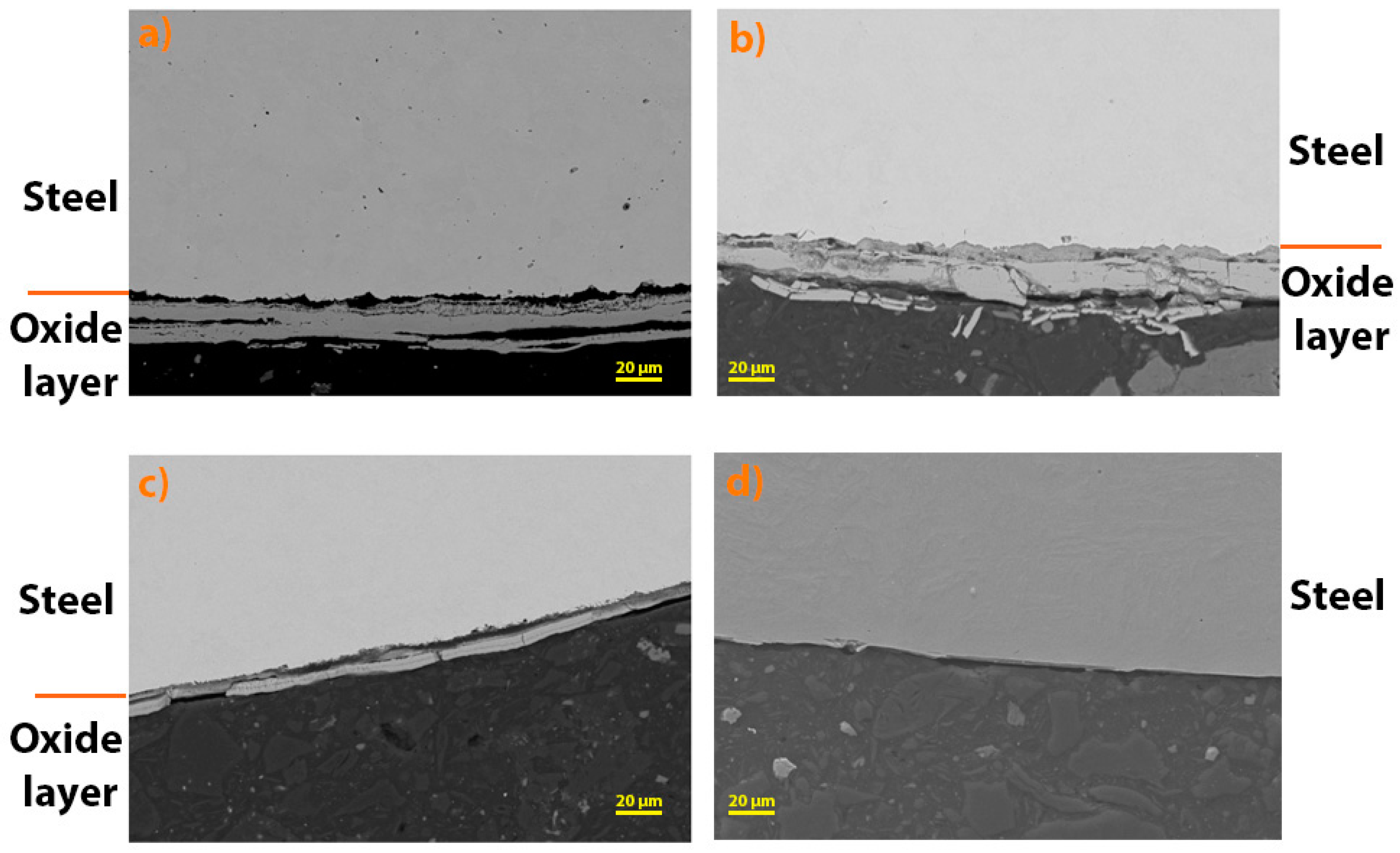

The oxide layers formed were further analysed using SEM (

Figure 6). It can be seen that the thickest oxide layer was formed on steel 16Mo3, followed by 13 Cr, T24 and P91. The results are in agreement with the analysis of TG (

Figure 5) and consequently with the calculated rate constants (

Table 3).

In addition, the thickness of the oxide layers formed on the steels examined was measured. The following table (

Table 4) shows the average of the measured thickness. The results show that the thickest oxide layer was formed on 13Cr steel, followed by 16Mo3, T24 and P91 (with no oxide layer observed on SEM). For 13Cr steel, there are deviations from the TG analysis results, but if you look at

Figure 6, it is obvious that the oxide layer on 13Cr steel is cracked and chipped, which is why these results differ. And as already mentioned, no oxide layer was found on the surface of P91 steel after high-temperature oxidation, which is also in agreement with the results of the TG analysis (

Figure 5).

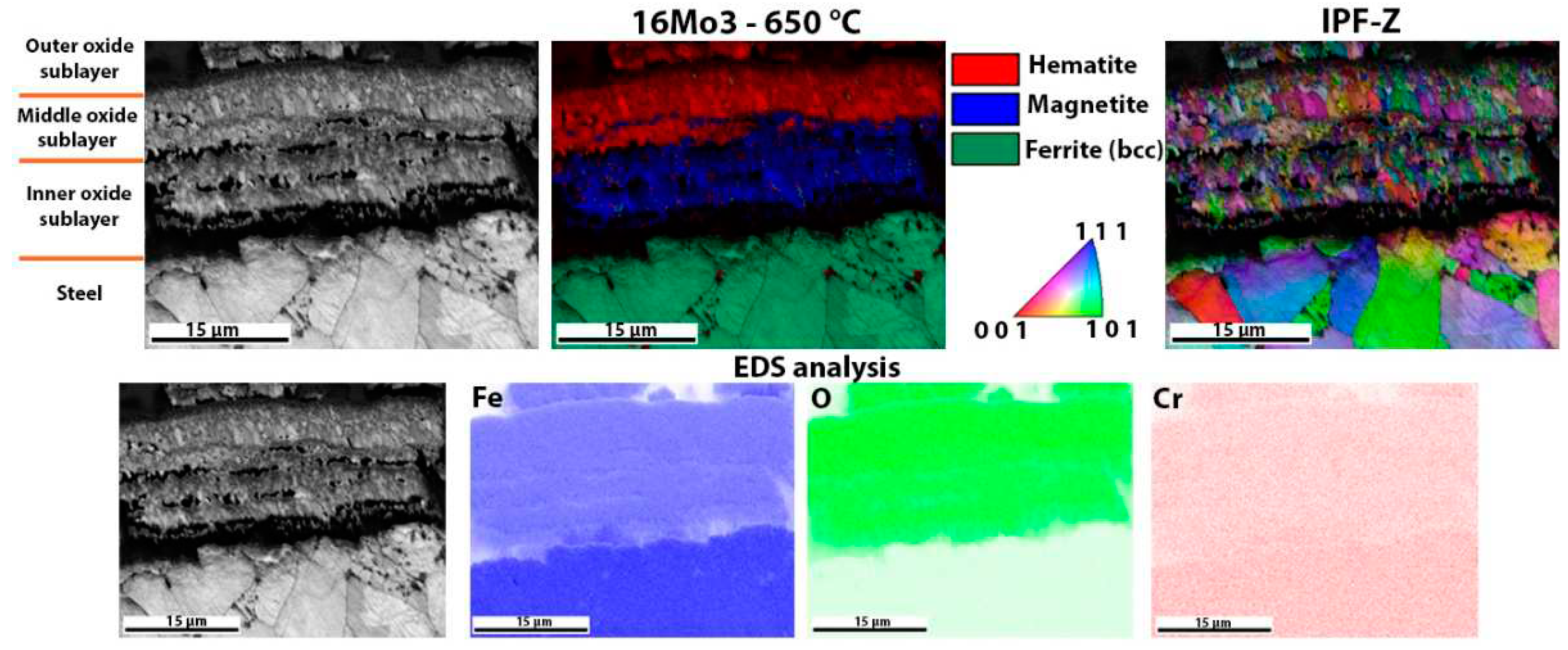

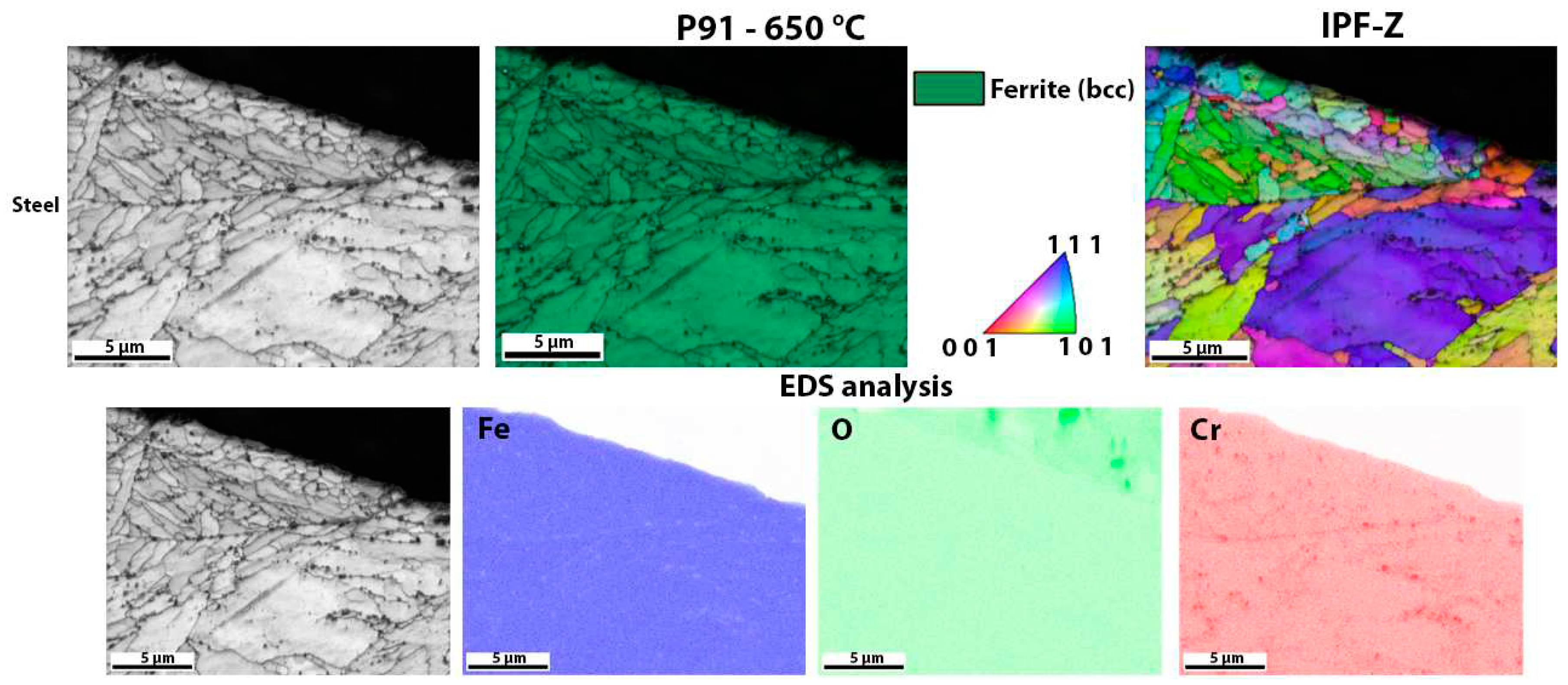

The oxide layers formed were also examined using EBSD analysis.

Figure 7 shows the oxide layer formed after high-temperature oxidation of 16Mo3 steel. It is obvious that the outer and middle oxide layers consist mainly of hematite. On the other hand, the inner oxide sublayer is mainly magnetite. IPF-Z mapping also showed that the grain size in the outer and inner oxide layers is smaller than in the middle oxide sublayer. However, EDS analysis showed no differences within the oxide layer. Fe, O and Cr are essentially homogeneously distributed throughout the oxide layer formed. There are some green coloured grains in the oxide layer (mainly in the middle and inner oxide sublayers), which are not ferrite but wüstite, as both have the same body-centered cubic crystal structure (bcc). This applies to all oxide layers of the examined samples (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), i.e., green coloured grains in the oxide layer are wüstite and not ferrite.

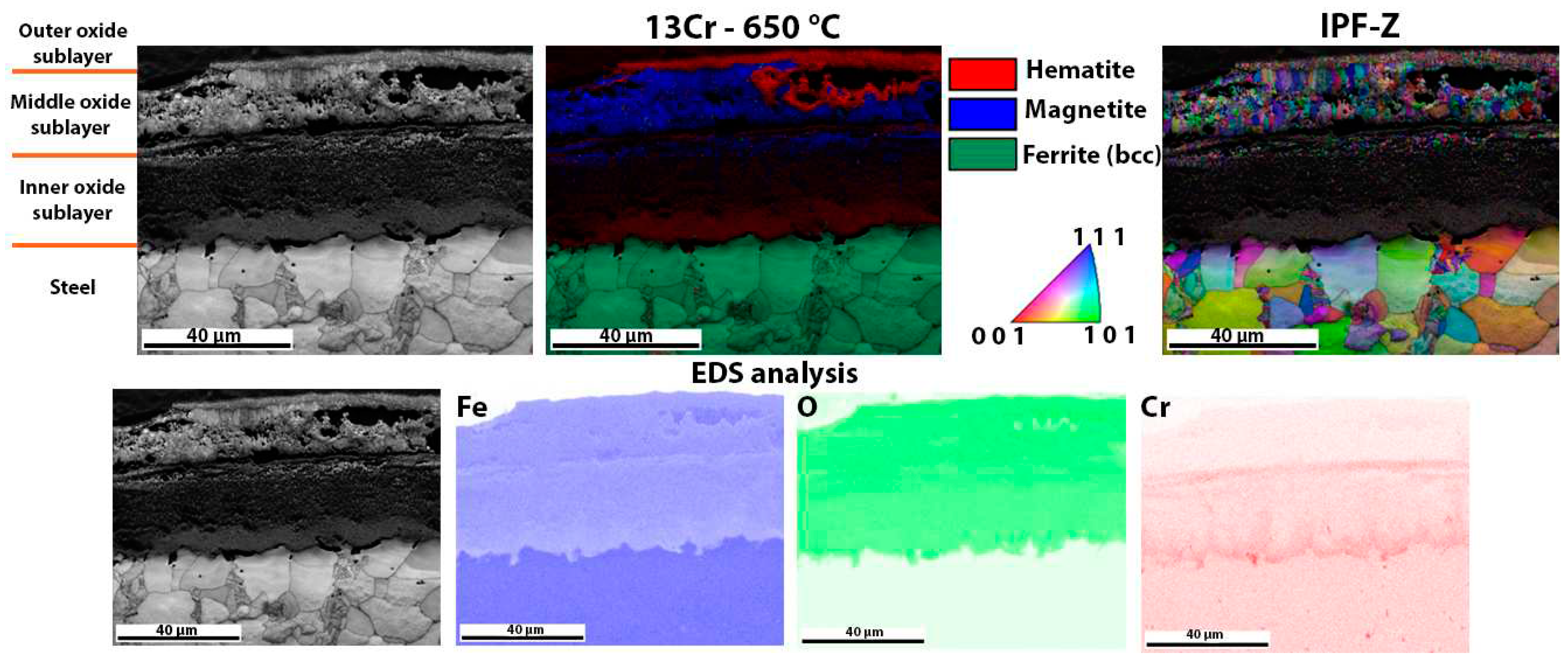

Figure 8 shows the oxide layer formed after high-temperature oxidation of 13Cr steel. It is obvious that the outer and inner oxide sublayer consists mainly of hematite. On the other hand, the inner oxide sublayer is mainly magnetite. IPF-Z mapping also shows that the grain size in the outer and inner oxide sublayer is smaller than in the middle oxide sublayer. The EDS analysis of the surface distribution of the elements shows that there is an increased Cr content in the inner oxide sublayer. However, as far as O and Fe are concerned, they are essentially homogeneously distributed throughout the oxide layer formed. In the oxide layer (mainly in the middle and inner oxide sublayers) there are some green coloured grains which are not ferrite but wüstite, as both have the same body centered cubic crystal structure (bcc). In this case, there are fewer wüstite crystal grains in the oxide layer than in the 16Mo3 steel. This is also consistent with the results of the TG analysis (

Figure 5), as diffusion is fastest in the wüstite, which means that the oxidation rate should be higher for 16Mo3 steel than for 13Cr and the calculated rate constant (

Table 3) should also be lower than that calculated for 16Mo3 steel.

The last oxide layer analysed was one that had formed on T24 steel after high-temperature oxidation (

Figure 9). In this case, although an oxidation layer was found, the entire sublayer consisted mainly of hematite. Some magnetite crystal grains were found in the inner oxide sublayer and some wüstite grains were also found in the middle oxide sublayer. As far as the size of the grains is concerned, the same trend as in the other analysed oxide layers is shown, i.e., the outer and inner oxide sublayers consist of smaller crystal grains than the inner oxide sublayer. EDS analysis of the surface distribution of the elements shows that the Cr content is increased in the inner oxide sublayer, while the Fe content decreases in the inner oxide sublayer. O, on the other hand, is essentially homogeneously distributed over the entire oxide layer formed. The results again agree well with the analytical results from TG (

Figure 5), where T24 steel shows the second lowest weight increase during high-temperature oxidation and the second lowest calculated rate constant (

Table 3).

Figure 10 shows the surface of P91 steel after high-temperature oxidation. In this case, there was no oxide layer that could be analysed with EBSD. The result was to be expected as the TG analysis also showed that there was only a minimal increase in weight during oxidation. EDS analysis was also only done to show that there is no oxide layer that can be analysed (there is no increased amount of oxygen on the steel surface), it only shows that there are some Cr-based carbides in the matrix (areas with increased Cr). This is also consistent with the results of the TG analysis (

Figure 5), as P91 steel has the lowest weight increase during high-temperature oxidation and the lowest calculated rate constant (

Table 3).

The Cr content is the decisive factor in high-temperature oxidation. Even an average content of 2.6 wt.% lowers the oxidation rate considerably (as can be seen in

Table 3), the Cr content also changes the oxidation curve from exponential to cubic. This means that steels with low Cr content such as 16Mo3 and 13Cr are susceptible to severe oxidation, even in the presence of short-term, transient overheating. The strong weight gain due to oxidation is already visible after one hour (see

Figure 5). The thicker oxide layers in the 16Mo3 and 13Cr steels show a clear distinction between hematite and magnetite, as shown by the EBSD analysis in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. At higher Cr contents, such as in steel T24, magnetite should form, but the crystal structure is difficult to assess with EBSD due to the smaller grain size, so only the Fe-rich hematite can be clearly distinguished. The high Cr contents in P91 prevent a much thicker oxide layer formation, so that the oxide layer could not be observed (

Figure 10). This is also consistent with the TG curves (

Figure 5) and the calculated constant rates (

Table 3). The oxide layers of 16Mo3 and 13Cr are brittle and crumble during sample preparation, which leads to unreliable measurements of the oxide layer thickness, so we focused on the thermogravimetric measurements.