1. Introduction

Nowadays, there is a continuous search for materials that show high corrosion resistance, which would ensure high durability of products, including bone implants and those working at offshore. These materials often demonstrate low hardness and resistance to wear due to friction. A material, which shows limited surface strength and corrosion resistance, especially in an environment containing chlorides, is relatively cheap and commonly used AISI 316L austenitic steel, which is still applied for implants and medical devices [

1,

2,

3], as well as in several other industries [

4,

5]. These problems can be solved to some extent by using surface engineering methods. Currently, the most commonly used surface treatments of austenitic steels are: nitriding [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], carburizing [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], nitrocarburizing [

6,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] and DLC coating deposition [

24,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. The aim of these processes is to improve various functional properties of steels, such as increasing hardness, resistance to wear due to friction and corrosion [

6,

30], as well as improving hydrophilicity and reducing bacterial adhesion to the surface [

37]. One of the most common surface treatments of austenitic steels is ion nitriding [

6,

7,

38]. Properly performed nitriding of austenitic steel provides many benefits, including a significant increase in surface hardness and increased resistance to wear due to friction or corrosion [

6,

38]. However, the disadvantage of all the above methods is the relatively high cost of devices, the need to use of clean gases (nitrogen, methane, hydrogen) and, in the case of ion treatments, the use of vacuum systems, which makes them even more expensive.

Despite the large amount of research on the surface treatment of austenitic steels, no research center in the world has yet addressed the issue of thermal oxidation of austenitic steel in an air atmosphere in order to improve its performance properties. There are no scientific publications on this topic, which makes it an area requiring research. Ecological and cheap thermal oxidation process of austenitic steel can potentially lead to the formation of layers with interesting and useful properties, such as increased corrosion or friction wear resistance and also decorative values in the form of changing the colour of the steel surface.

The aim of the work was to assess the effect of thermal oxidation of commonly used AISI 316L steel on the phase composition and basic functional properties, such as: surface roughness, hardness, wettability, friction wear and corrosion resistance of the produced oxide layers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation

The flat surface of AISI 316L steel samples (

Table 1) in the form of ϕ25x6 mm discs cut from a round bar was subjected to grinding on 240 to 1200 grit abrassive SiC papers (Lam Plan, Gaillard, France), then polished using a polishing disc and a 1 μm diamond suspension (Lam Plan, Gaillard, France), and finally degreased in acetone (Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland) using an ultrasonic cleaner (Intersonic, Olsztyn, Poland). The oxide layers were formed by heating the steel in air at three temperatures: 350°, 400°C and 450°C for 6 h at atmospheric pressure using a tube furnace (Nabertherm, Lilienthal, Germany) (

Figure 1).

2.2. Surface Topography and Roughness Tests

The tests of the topography and roughness of the produced layers’ surfaces were carried out using a Wyko NT9300 optical profilometer (Veeco, Plainview, NY, USA), measuring the Ra (arithmetic mean deviation of the profile from the mean line) and Rz (the sum of the arithmetic mean height of the five highest elevations above the mean line and the average depth of the five lowest depressions below the mean line) parameters at 10× magnification with the Vision software. Five roughness measurements were performed for each variant of the samples and selected 3D images of the sample surfaces were presented.

2.3. X-ray Diffraction Measurements

Using the X-ray diffraction (XRD) method, the phase composition of the layers was measured. The D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany) and a CuKα1 tube with a wavelength of λ=0.154056 nm were used for the measurements. The tests were carried out at a voltage of 40 kV, a current of 40 mA, a step of Δ2θ=0.05 °, and a counting time of 3 sec. The thin oxide layers were examined utilizing grazing incidence angle diffraction at an incident X-ray beam angle of 2°. The obtained diffraction patterns were then analyzed using the Brucker’s EVA program.

2.4. Microhardness and Friction Wear Resistance Tests

The microhardness was measured using a Shimadzu HMV-G microhardness tester (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a Vickers indenter. In order to investigate the effect of the oxidation process on the hardness of AISI 316L austenitic steel, three different loads were used: 0.05 kg, 0.1 kg, and 0.2 kg, and seven measurements were taken for each load and sample. “Ball-on-disc” frictional wear tests were conducted using a T-21 tribotester (ITEE, Radom, Poland), following the specifications outlined in ASTM G 99–05 and ISO 20808:2004 standards, at an ambient temperature of approximately 22 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 45%. The tests utilized 10 mm diameter Al

2O

3 balls with a polished finish. They were performed under a load of 5 N with measurements taken over a duration of 6000 revolutions, at a speed of 145 rpm. Wear resistance was assessed by measuring the size of the groove profile created by wear in four different areas. The geometry of the grooves was analyzed using a Wyko NT9300 optical profilometer (Veeco, Plainview, NY, USA), and the cross-sectional area was computed with the Vision program. The wear rate (

Wv) was calculated using the following equation:

where:

V represents the volume of material worn away, derived from the average cross-sectional area of the grooves and the wear circumference,

Fn signifies the axial force, and

s denotes the length of the friction track. The wear rates and variations in the friction coefficient were presented on graphs, while the Veeco optical profilometer was employed to visualize the selected wear tracks.

2.5. Corrosion Resistance Tests

The corrosion resistance of AISI 316L steel after surface treatment was tested in a non-deoxygenated 3.5% NaCl solution (Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland). A three-electrode system was used for the tests, in which the sample was the tested electrode, the Ag/AgCl electrode (Eurosensor, Gliwice, Poland) was the reference electrode, and a platinum wire was the auxiliary electrode. Before the tests, the materials were kept in an open circuit for 2 hours using an Atlas-Sollich 1131 device (Atlas-Sollich, Rębiechowo, Poland), which allowed for the stabilization of their potentials and the determination of the open circuit potential (Eocp) value. Then, the anodic polarization curves of the tested materials were recorded using the potentiodynamic method. In the potential range of ±250 mV from the Eocp potential, a polarization rate of 0.2 mV/sec was used, in the remaining range up to 1000 mV, a rate of 0.8 mV/sec was used. The measurements were carried out using the AtlasCorr program. The pitting potentials Epit of the tested materials were read from the obtained polarization curves. Utilizing the AtlasLab program, the corrosion current density icorr, the corrosion potential Ecorr with the Tafel method within the scope of applicability of this method, and the polarization resistance Rpol using the Stern method, were determined. At least three measurements were taken for each layer variant. After potentiodynamic tests, the surfaces of corroded samples were documented using a Nikon Eclypse LV150N microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA).

2.6. Wettability Tests

In the study of wettability of oxide layers formed after oxidation of AISI 316L austenitic steel, the liquid used was distilled water. A special, precise syringe was utilized to apply it to the sample surface in the form of drops. A goniometer model 90-U3-PRO from Rame-Hart (ramé-hart instrument, Succasunna, NJ, USA) was used to measure the contact angle. This device was equipped with a precise, adjustable table, LED lamp and camera. The DROPimage program was used to measure the contact angles and take photos of the drops. Seven measurements were taken for each variant and the average was calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Appearance

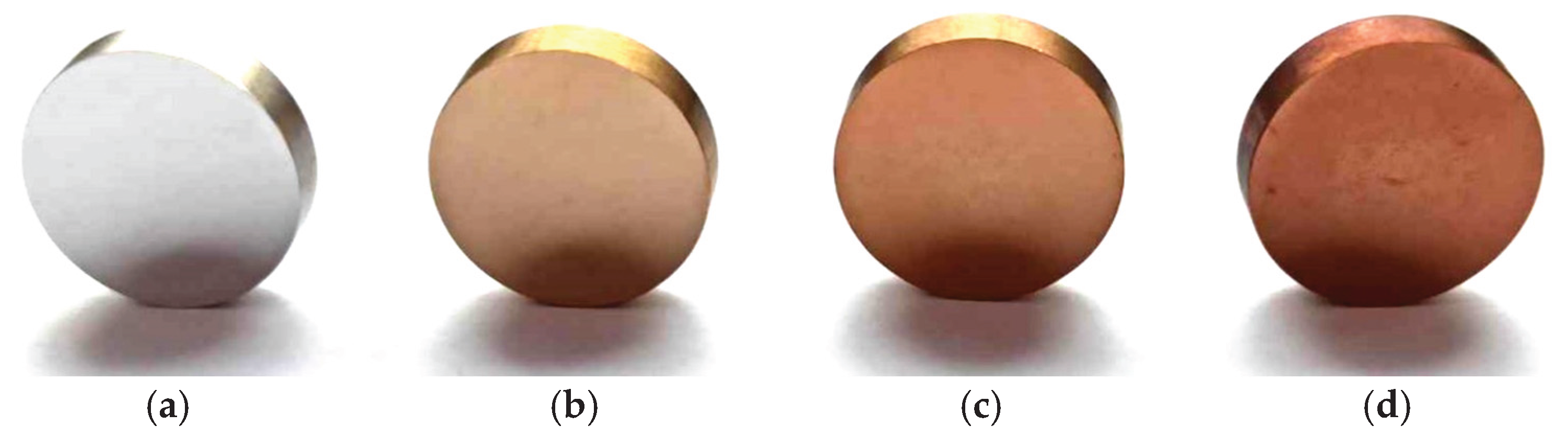

Figure 2 shows the appearance of the surface of austenitic steel after oxidation in an open furnace in an air atmosphere. The initial state has a silver color, typical of polished austenitic steel (

Figure 2a). After oxidation at 400 °C, the color changed to light gold (Figure 2b). Further increase in the process temperature caused the gold shade to become darker (Figure 2c), obtaining a shade of rose gold for steel oxidized at 500 °C (

Figure 2d). The darker color may suggest that the layer formed after oxidation is thicker. Oxidation caused the AISI 316L steel to gain an additional aesthetic aspect.

3.2. Surface Topography and Roughness

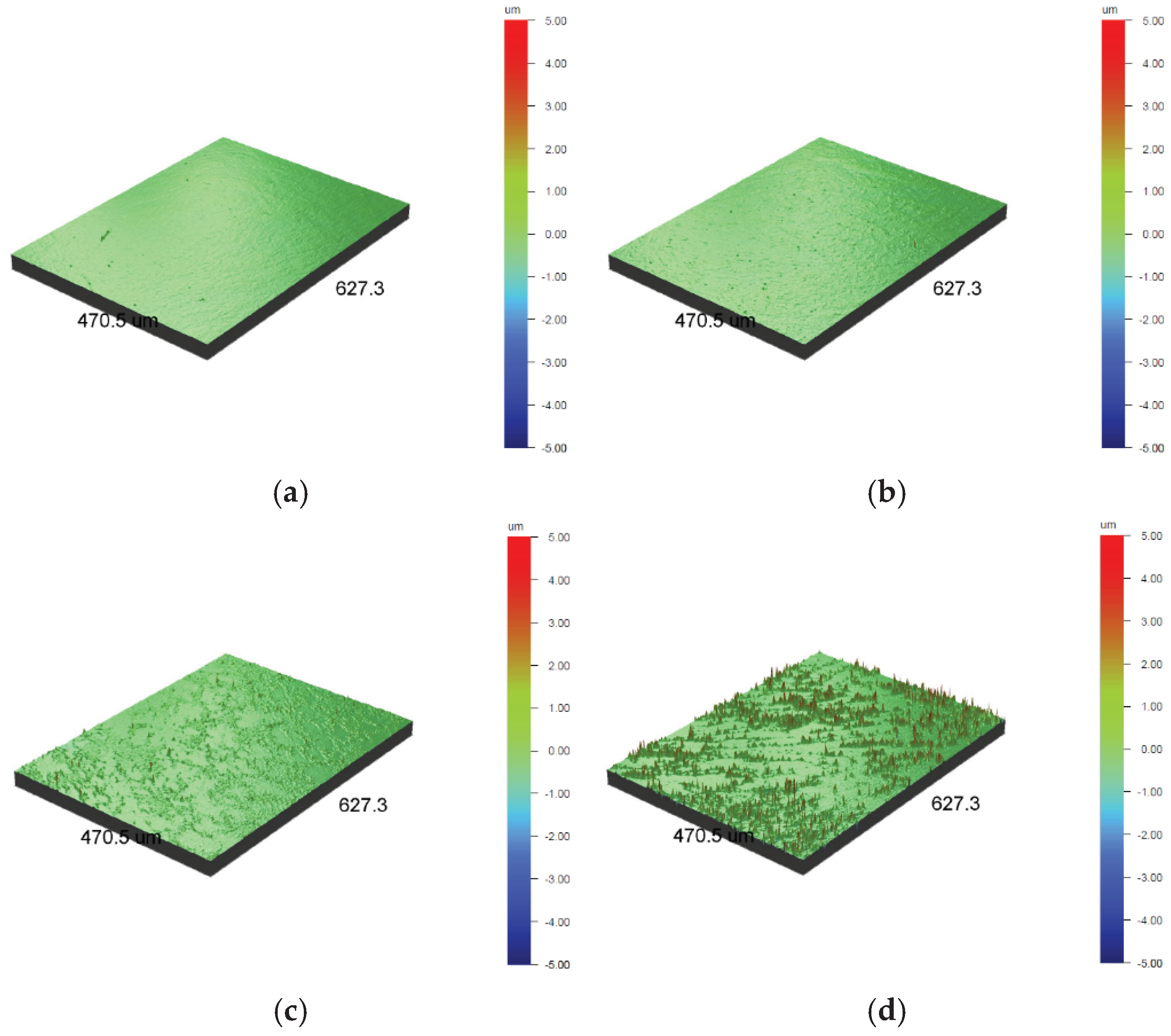

Based on tests performed with an optical profilometer, the roughness parameters Ra and Rz were determined (

Table 2). From the obtained results it can be concluded that the control sample with a polished surface is characterized by the lowest roughness, i.e. Ra=33.1 nm and Rz=989.6 nm. The parameters Ra and Rz after the oxidation process performed at a temperature of 400 °C remain at almost twice the level of the parameters for the initial state. Definitely the highest values of roughness parameters were obtained for steel oxidized at 500 °C. It can be seen that with the increase of the oxidation temperature the roughness of the steel surface increases.

The 3D images shown in

Figure 3 confirm the increase in surface development with the increase in oxidation temperature of the 316L austenitic steel, which makes it more uneven due to the formation of oxides. The change in the shade of the steel from light gold to dark gold (

Figure 2b-c) may also be due to the significant development of its surface (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

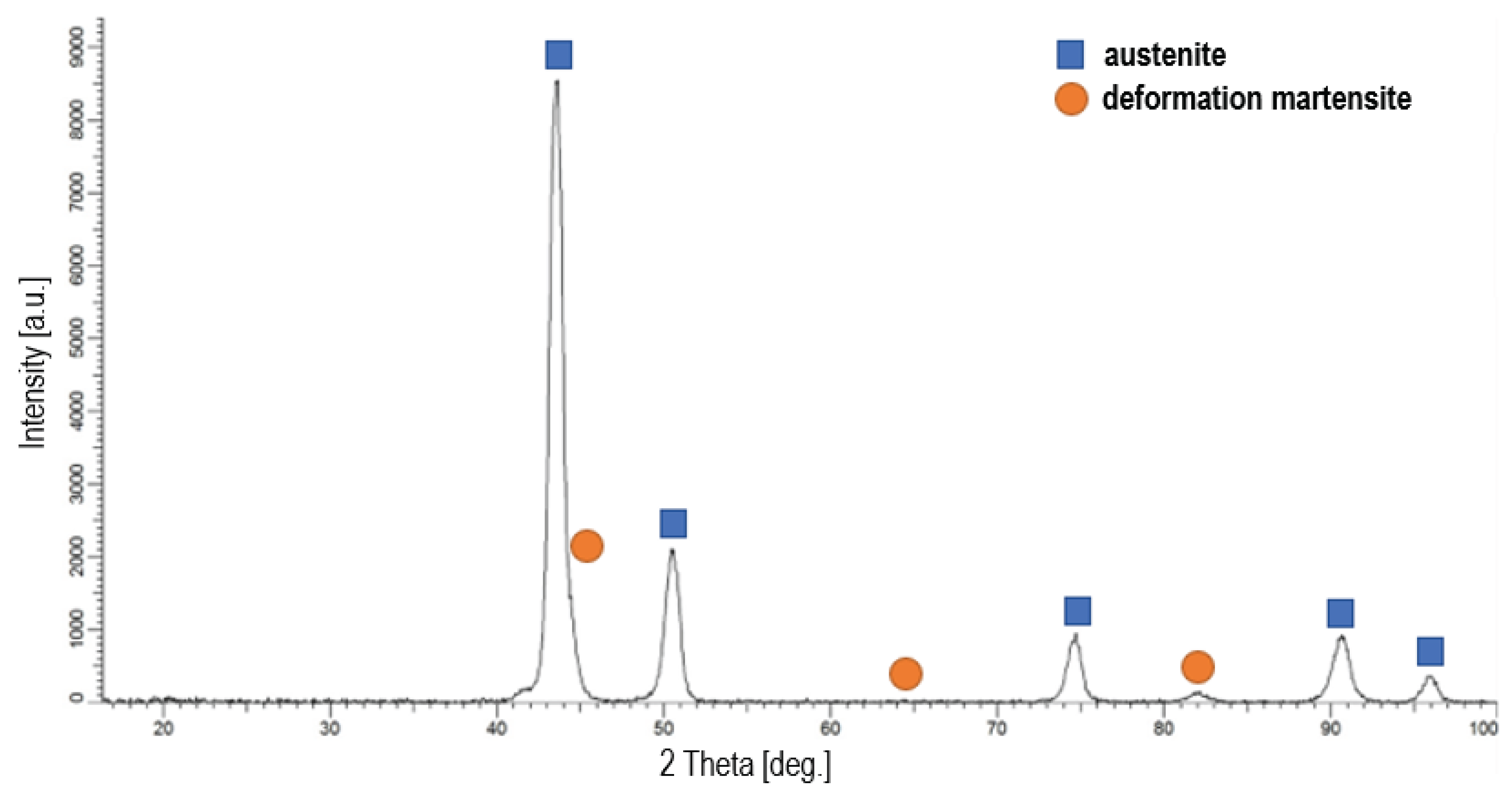

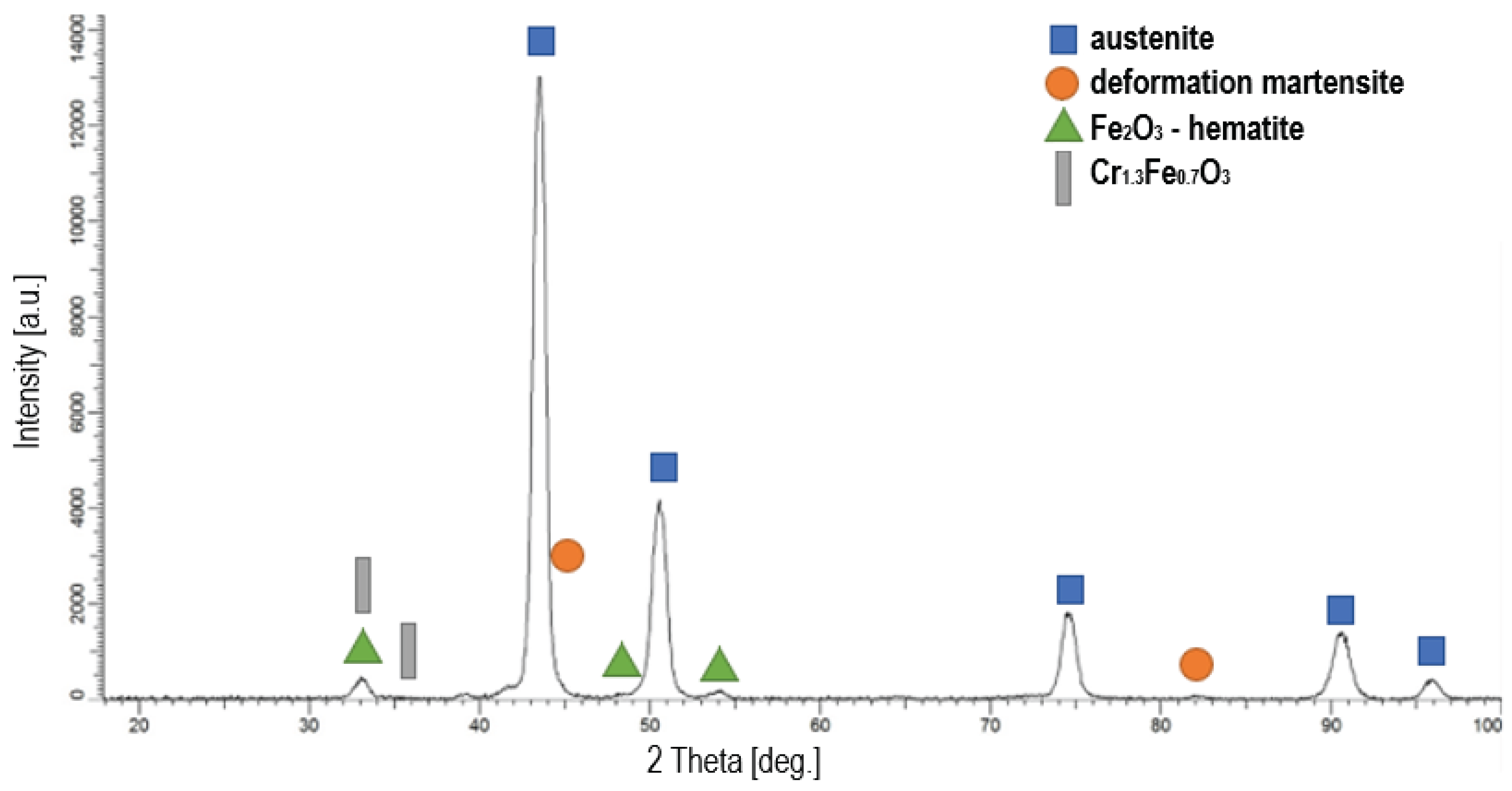

3.3. Microstructure Analysis

Figure 4 shows X-ray diffraction patterns for the steel in its initial state and

Figure 5 an example pattern for steel oxidized at 500 °C, since all patterns for oxide layers are similar with no significant differences in peak intensities and positions. AISI 316L steel is composed of austenite and deformation martensite, which was formed in the surface layer as a result of grinding and polishing (

Figure 4). Due to the pressure exerted to the sample surface during mechanical preparation, a martensitic transformation induced by plastic deformation occurred (TRIP effect) [

12,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The XRD studies confirmed that after oxidation of AISI 316L austenitic steel, there is a layer of oxides on its surface (

Figure 5). At all process temperatures (400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C), two types of oxides were detected, which are: Fe

2O

3 (hematite) and Cr

1.3Fe

0.7O

3 and the peaks in all cases were of very similar, low intensity. Another phase identified after oxidation processes was austenite located under the layers in the substrate. The peaks from austenite showed high intensity, and from oxides relatively low, which indicates that the layers produced were very thin. This conclusion is also supported by the fact that the layers were examined at a low angle of incidence of the X-ray beam (2°). Due to their very small thickness, they could not be observed on cross-sections using SEM.

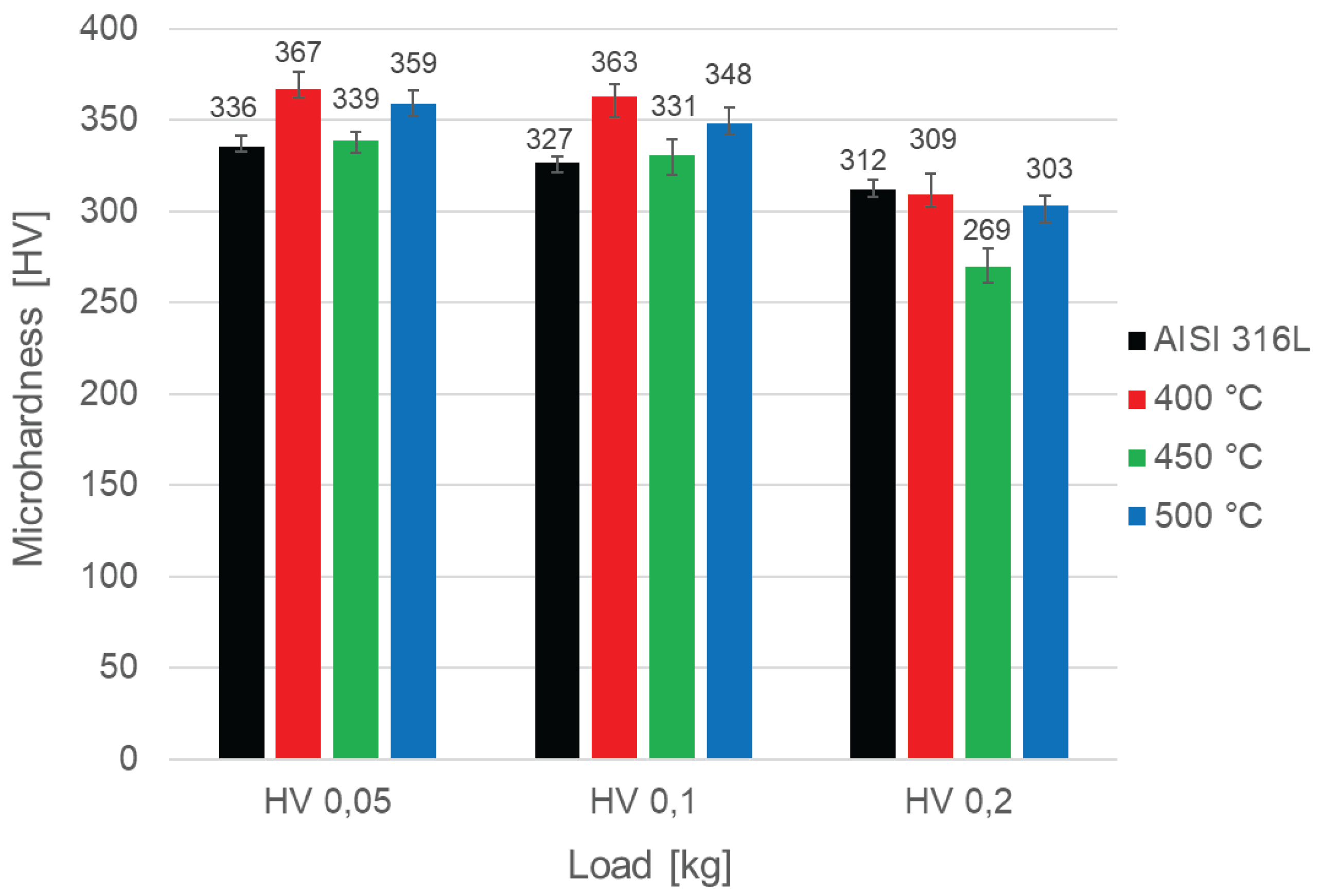

3.4. Microhardness and Friction Wear Resistance Analysis

In order to investigate the effect of the oxidation processes of AISI 316L austenitic steel on its hardness, microhardness tests were carried out using the Vickers method at different loads (

Figure 6). The measurements show that oxidation of samples made of austenitic steel does not significantly affect their hardness. A slight tendency of hardness increase is visible at the lowest loads (HV0.1 and HV0.05). Among the oxidized layers, the lowest microhardness is shown by the one after oxidation at 450 °C and it obtained slightly higher microhardness values than the steel in the initial state for loads of 0.05 kg and 0.1 kg. In the case of testing at a load of 0.2 kg, all oxidized layers are characterized by lower microhardness values with the most pronounced decrease of this parameter in the case of the layer oxidized at 450 °C. In turn, the highest microhardness is shown by the sample oxidized at 400 °C, which reaches 363 HV0.1 and 367 HV0.05. The steel after the 500 °C process achieved an intermediate hardness between the other variants after oxidation (i.e. 348 HV0.1 and 359 HV0.05). It is worth emphasizing, however, that the differences in hardness obtained between the samples are not large. Low values may result from the low thickness of the oxide layers, their brittleness and the influence of the soft substrate.

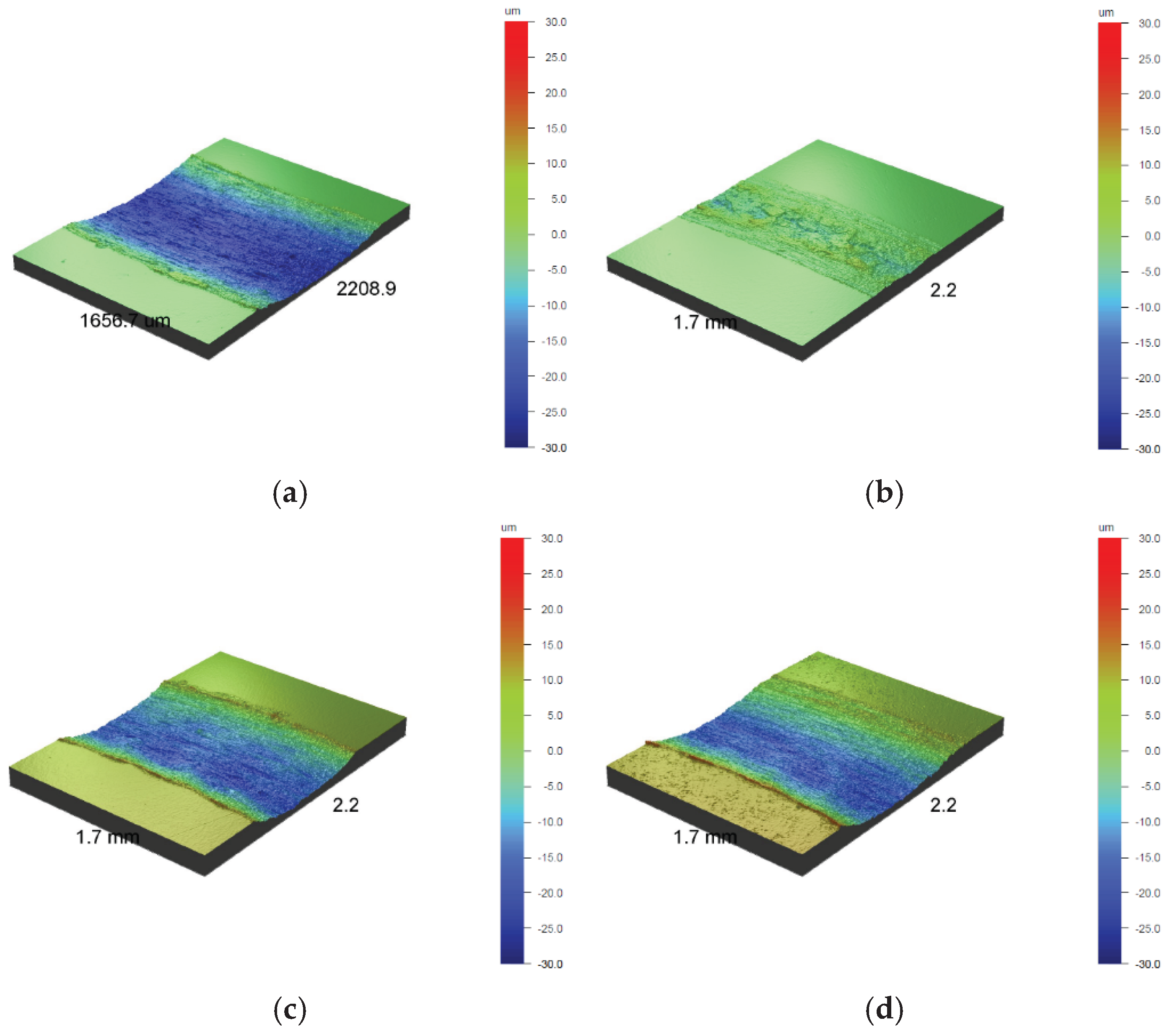

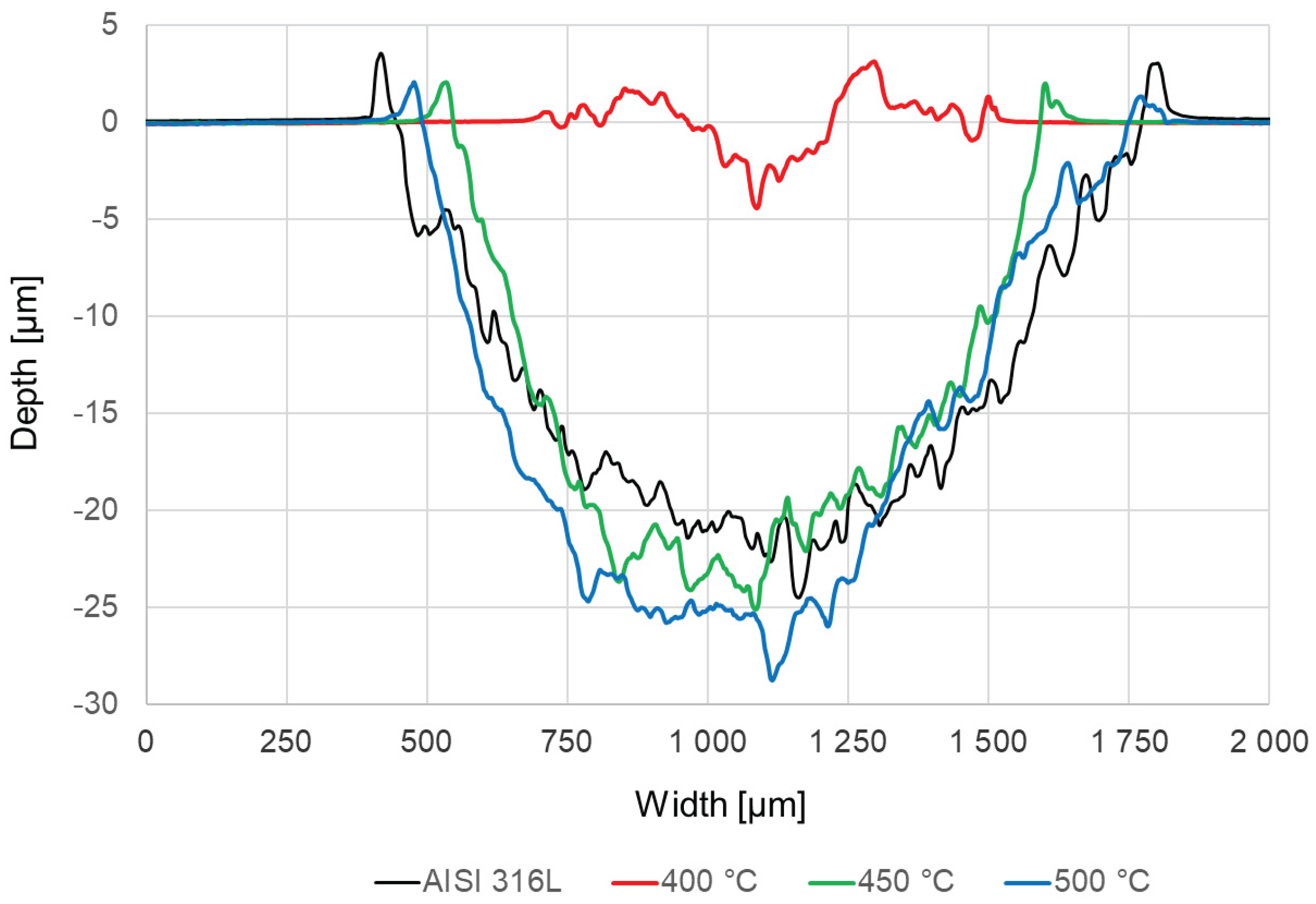

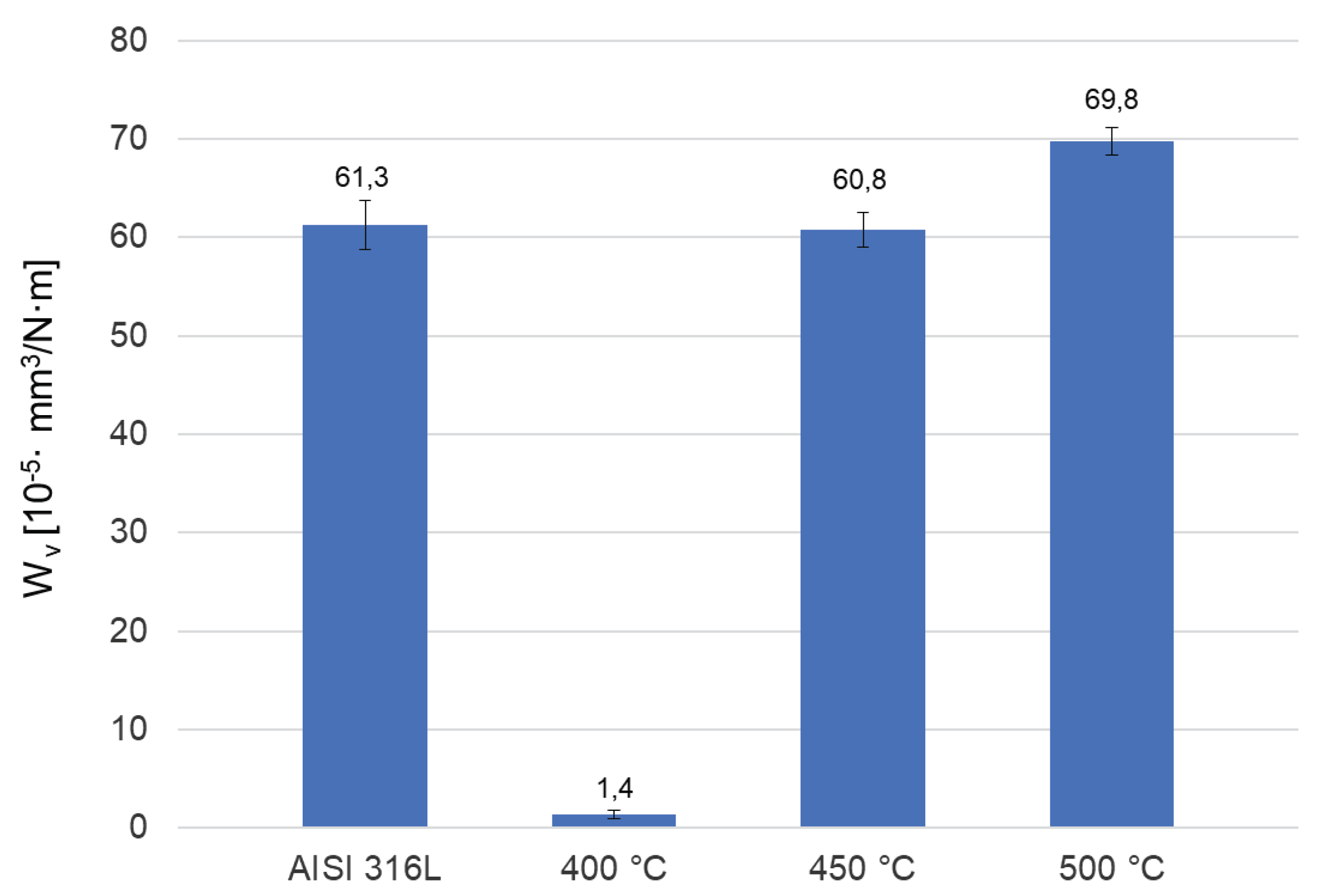

Among the abrasive wear obtained in the „ball-on-disc” test, the most noticeable is the wear observed for steel oxidized at 400 °C (

Figure 7b,

Figure 8). The wear made using a corundum ball is in this case the shallowest, which indicates the lowest wear of this sample. The other samples do not show such high resistance, they have worn more, and their widths and depths of abrasions are similar (

Figure 7a,c,d,

Figure 8).

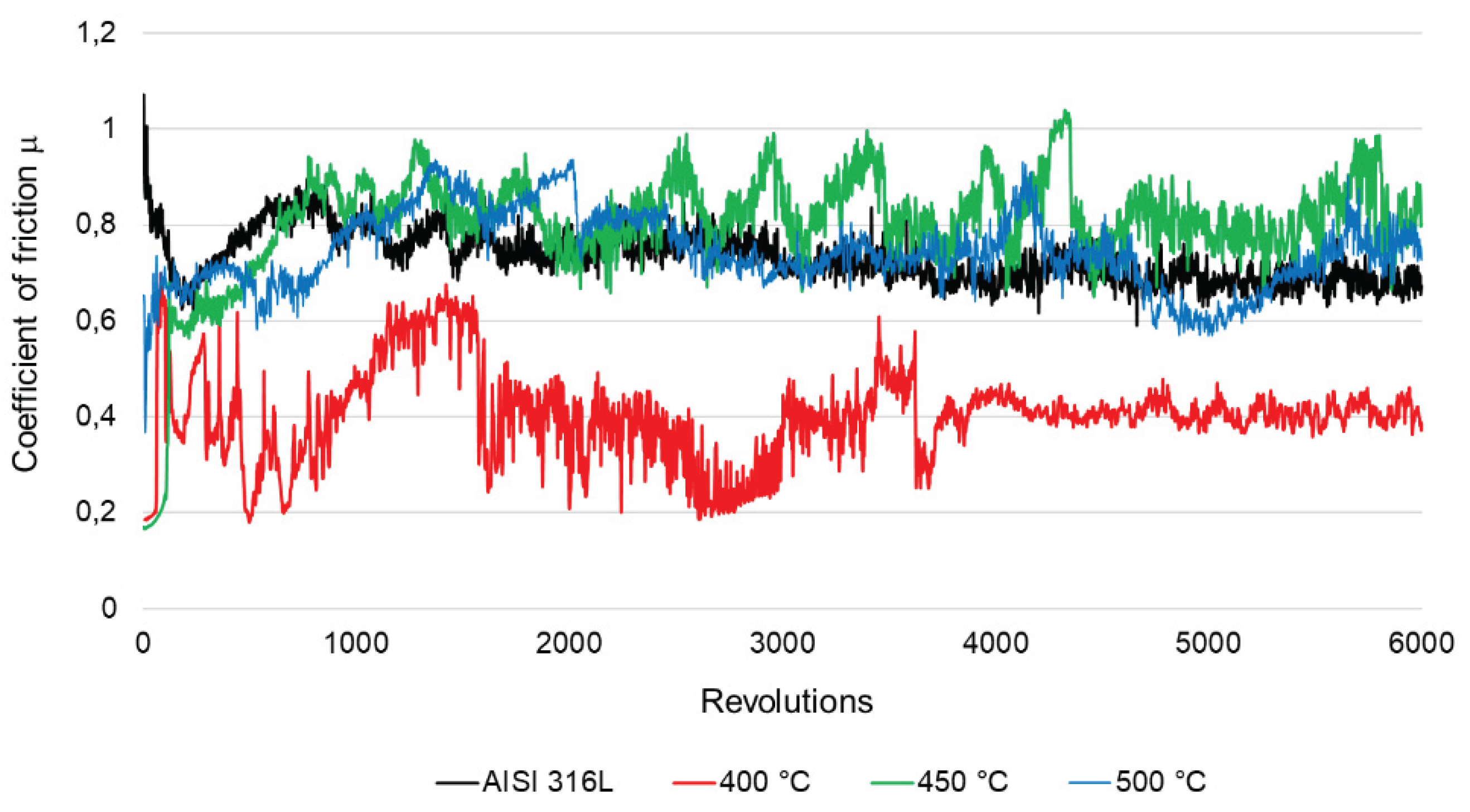

From the graph presented in

Figure 9, it can be concluded that during the tribological "ball-on-disc" test, the surface oxidized at 400 °C showed different properties than the others ones. Throughout the test, the friction coefficient for this sample is characterized by the lowest values, and at about 4000 revolutions it stabilizes and oscillates around 0.4, which is a value comparable to the coefficient of friction of a carbon coating produced on AISI 316L steel under DC glow discharge conditions measured at a load of 5N as well [

24]. The friction coefficient for the other steels, in the initial state and oxidized at 450 °C and 500 °C, remains at a similar level during the test, oscillating in the range of about 0.6-1. The average friction coefficient for the layers oxidized at 450 °C and 500 °C was about 0.8 and is higher than the average friction coefficient for the steel in the initial state (0.7), which may result from the greater roughness of the oxide layers (

Table 2).

The “ball-on-disc” tests showed that the steel after oxidation at 400 °C has the best tribological properties. It has the lowest coefficient of friction among the tested samples (Figure 9). In addition, the layer after oxidation at 400 °C shows the highest microhardness (Figure 6) and low roughness (

Table 2), which, combined with the low coefficient of friction, resulted in the most favorable wear rate, i.e. over 40 times lower than for the steel in its initial state (

Figure 10). The steel in its initial state and oxidized at 450 °C performed almost identically in the test. Oxidation at 500 °C resulted in the least favorable wear rate, which, despite its higher hardness compared to polished steel, probably results from the highest surface roughness (

Table 2), detachment of oxides and acting as abrasive particles.

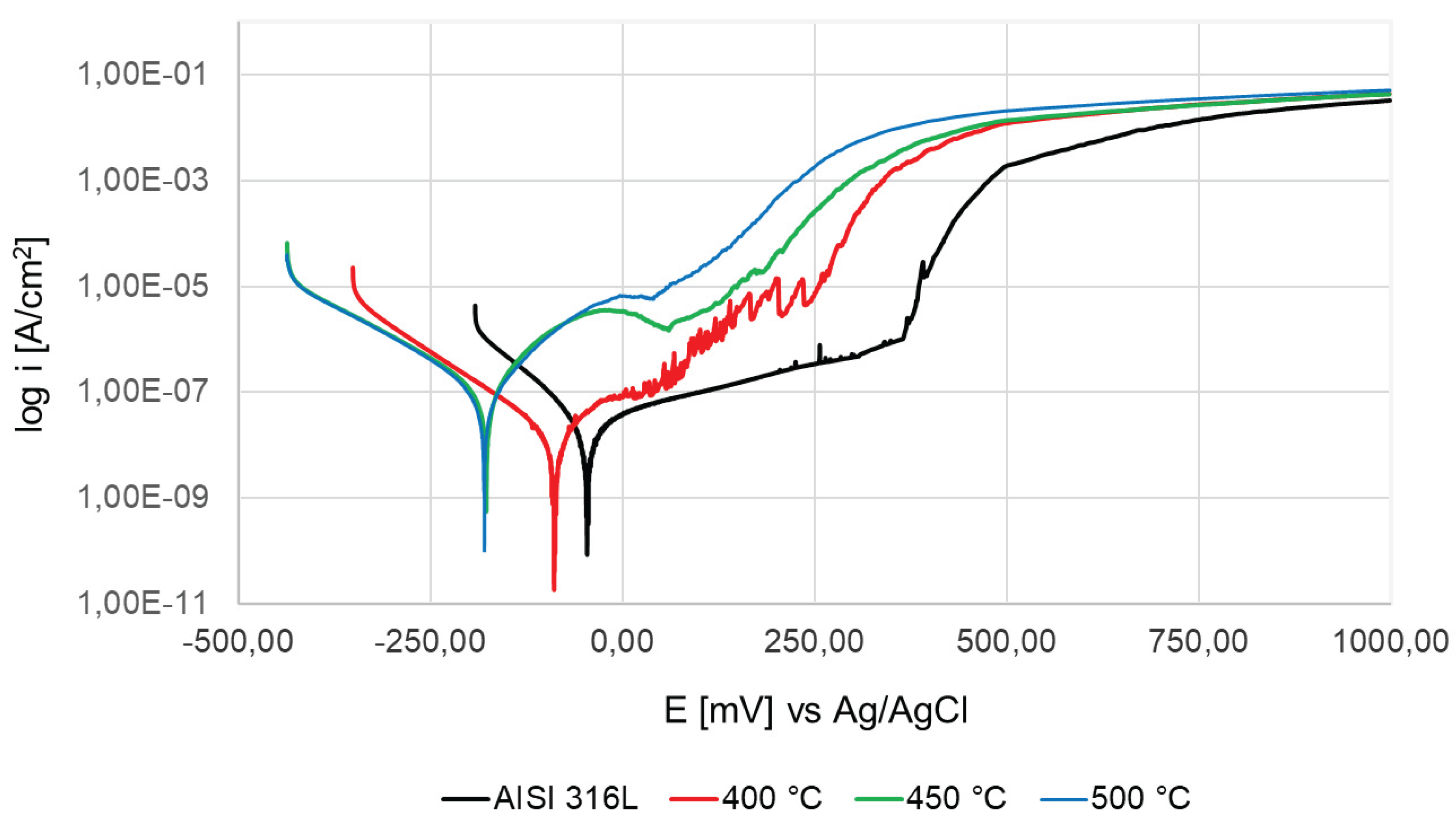

3.5. Corrosion Resistance Analysis

Based on the values of the corrosion potential E

corr, it can be stated that the highest resistance in the 3.5% NaCl environment is characteristic of the steel in the initial state, because it goes into the active state at the highest potential (-28 mV) (

Figure 11, Table 3). There is a visible trend showing that with the increase in the oxidation temperature, the corrosion potential decreases, down to the value of -196 mV for the layer oxidized at 500 °C. The situation is similar with the breakdown (pitting) potential E

pit, after exceeding which pits start to form. The lowest value of E

pit (160 mV) was observed for the sample after oxidation at 500 °C. Only the sample after the process at 400 °C showed a value of E

pit similar to the initial state and was lower only by about 22 mV. The highest value of the breakdown potential was observed for the initial state (420 mV). In turn, the clearly best value of the corrosion current density i

corr (41 nA/cm

2) and polarization resistance R

pol (909 kΩ∙cm

2) was observed for steel oxidized at 400 °C, which indicates that for these parameters the layer showed the highest dielectric properties, and electron exchange between the layer and the environment was the most difficult. The other layers oxidized at 450 and 500 °C were characterized by a decrease in the polarization resistance R

pol and an increase in the corrosion current density i

corr in relation to the layer oxidized at 400 °C, while their R

pol and i

corr values were lower than those for the steel in its initial state. The highest corrosion current density i

corr was characteristic of the initial state (227 nA/cm

2), probably due to the thinnest naturally formed passive layer compared to the thicker, more dielectric furnace oxidized layers. Despite the reduced corrosion potential E

corr and slightly lower breakdown potential E

pit compared to the steel in its initial state, oxidation at 400 °C guarantees an almost 2-fold increase in polarization resistance R

pol and an over 5-fold decrease in corrosion current density i

corr, which may be caused by the high homogeneity of the oxide layer formed under these process conditions.

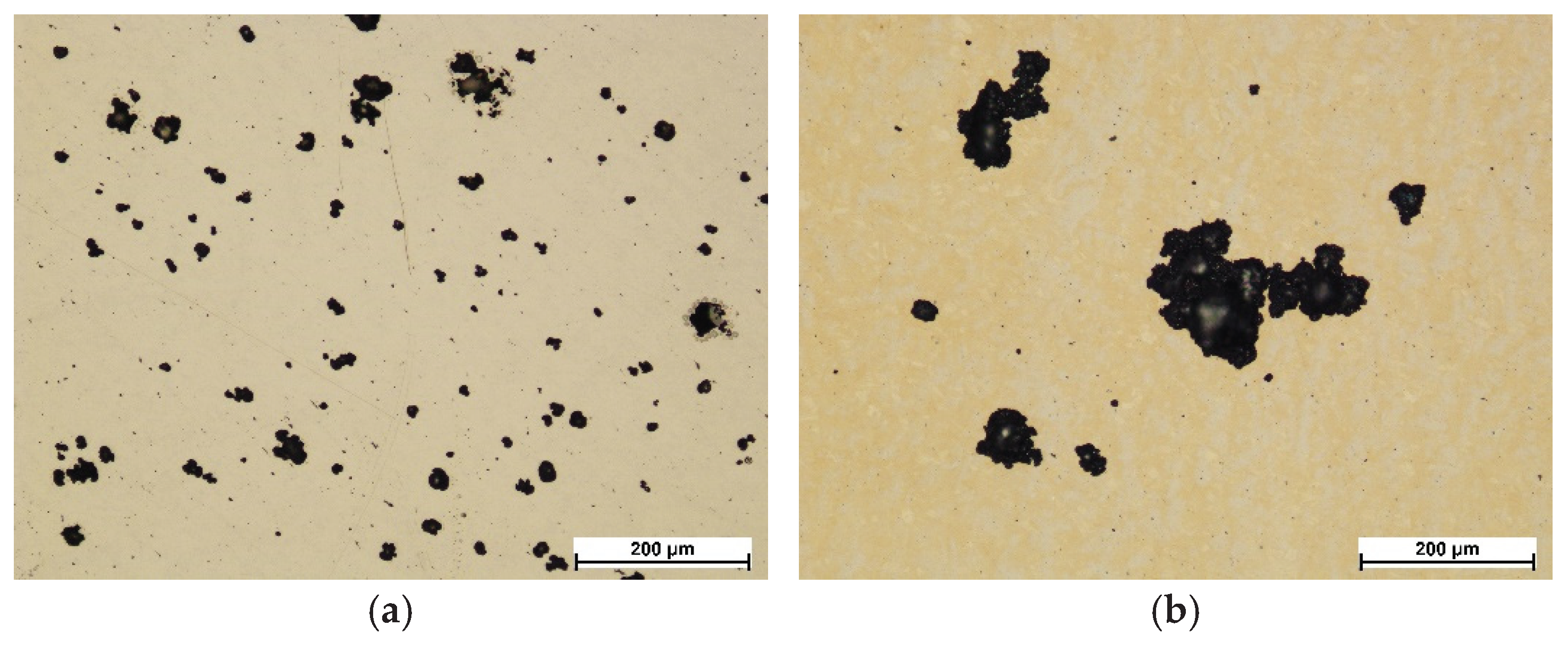

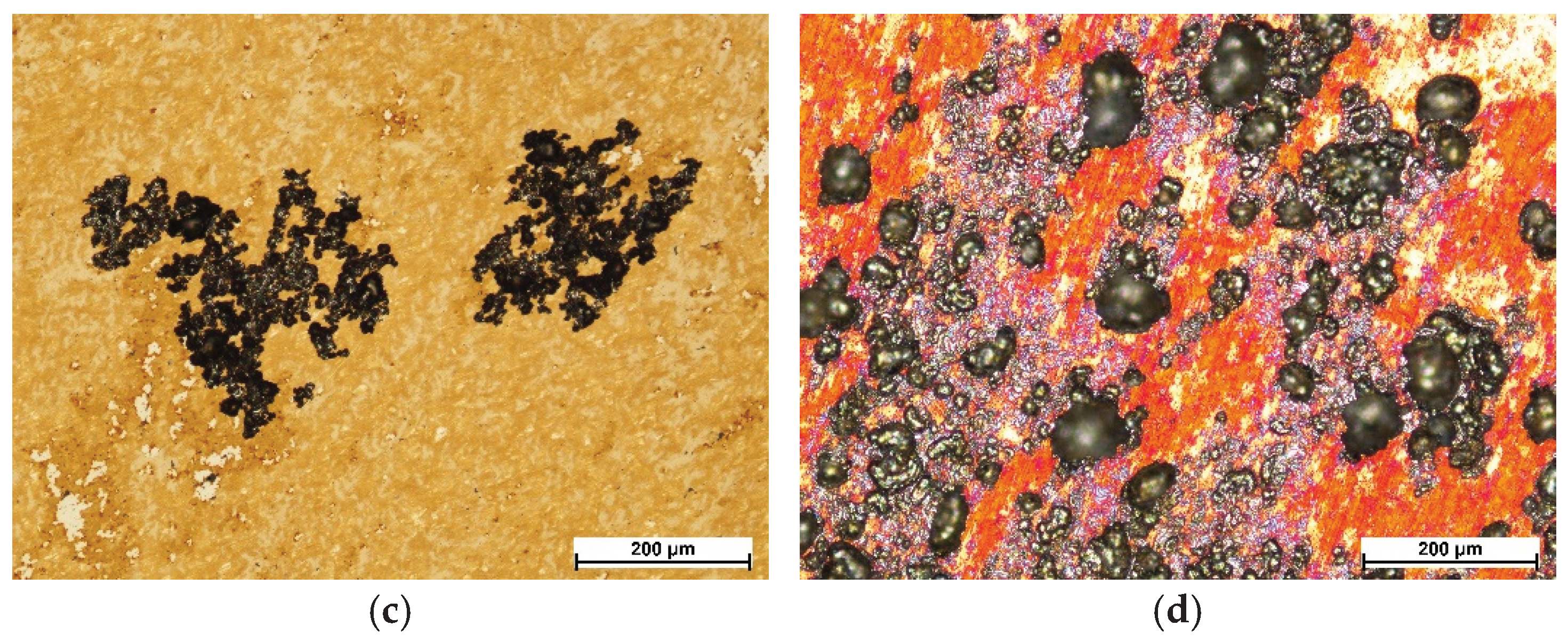

Figure 12 shows images of the steel surface and layers after corrosion tests. As expected, exceeding the breakdown potential resulted in the formation of corrosion pits in all cases. In the case of AISI 316L steel in the initial state, the pits are up to about 100 μm in size, and the smallest ones, which have only just started to form, are several μm in size. The number of pits in this case is high, but they did not reach large sizes (

Figure 12a). The layer oxidized at 400 °C showed pits of larger diameters (

Figure 12b), but of a much smaller number compared to the steel in the initial state. The largest pits in this case are bigger than 100 μm. Few small pits, which have only just started to form, are also visible. In turn, the pits formed on the steel oxidized at 450 °C are even larger than those obtained on the layer after the process at 400 °C, or the initial state (

Figure 12c). They show a less regular shape and there are no spherical pits observed, as in the case of the initial state or steel oxidized at 400 °C. Their branched shape suggests that they were formed by combining a larger number of small pits. The pits present on the steel after oxidation at 500 °C are the deepest in comparison to the other variants and are characterized by an irregular shape and high density on the surface of the layer (

Figure 12d).

The number and size of pits correlate with the values of the breakdown potential (Table 3). It can be seen that the lower the value of the breakdown potential E

pit, the greater the number and size of pits. A change in the color of the steel surface after the oxidation processes is also visible, which is related to the formed iron and chromium oxides (

Figure 12b-d). In the case of layers oxidized at 450 and 500 °C, bright areas were observed, where the oxide layers were most likely dissolved during potentiodynamic tests (Figure 12c,d). Such areas become anodic sites, where preferential pitting propagation may occur. In the case of the layer formed at 400 °C, no such dissolution was observed, which again confirms its high homogeneity, and the resulting pitting could have initiated in small, single defects of its structure, hence a smaller number of corrosion damages in this case (

Figure 12b) compared to AISI 316L steel in the initial state (

Figure 12a).

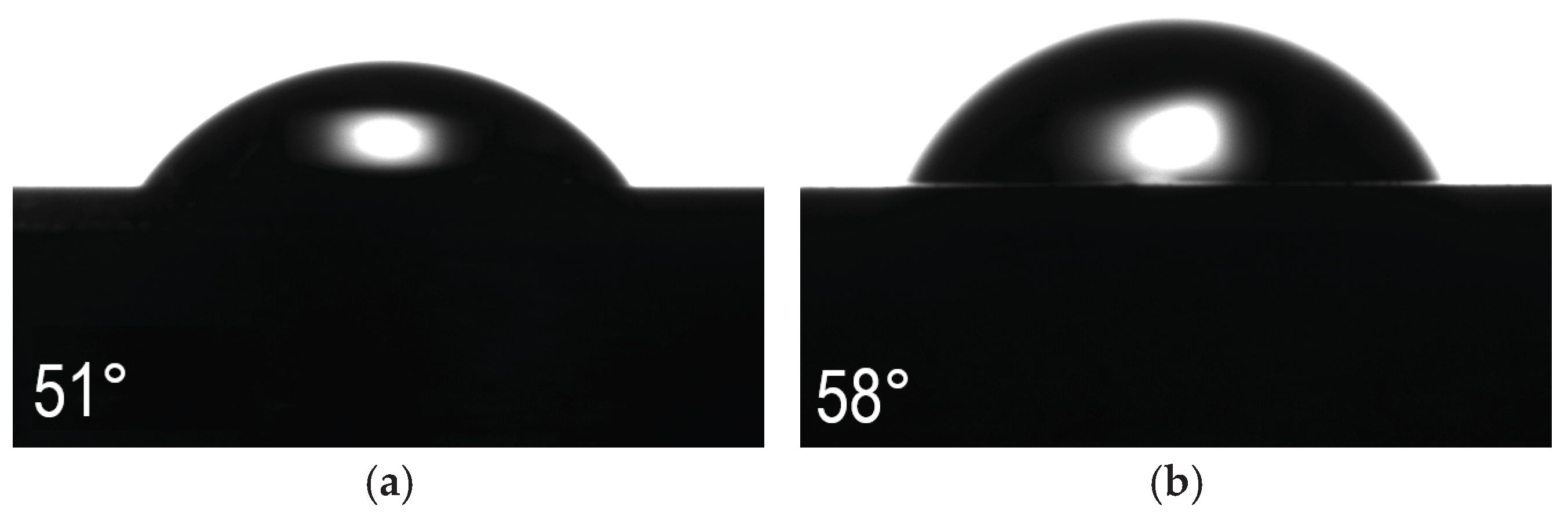

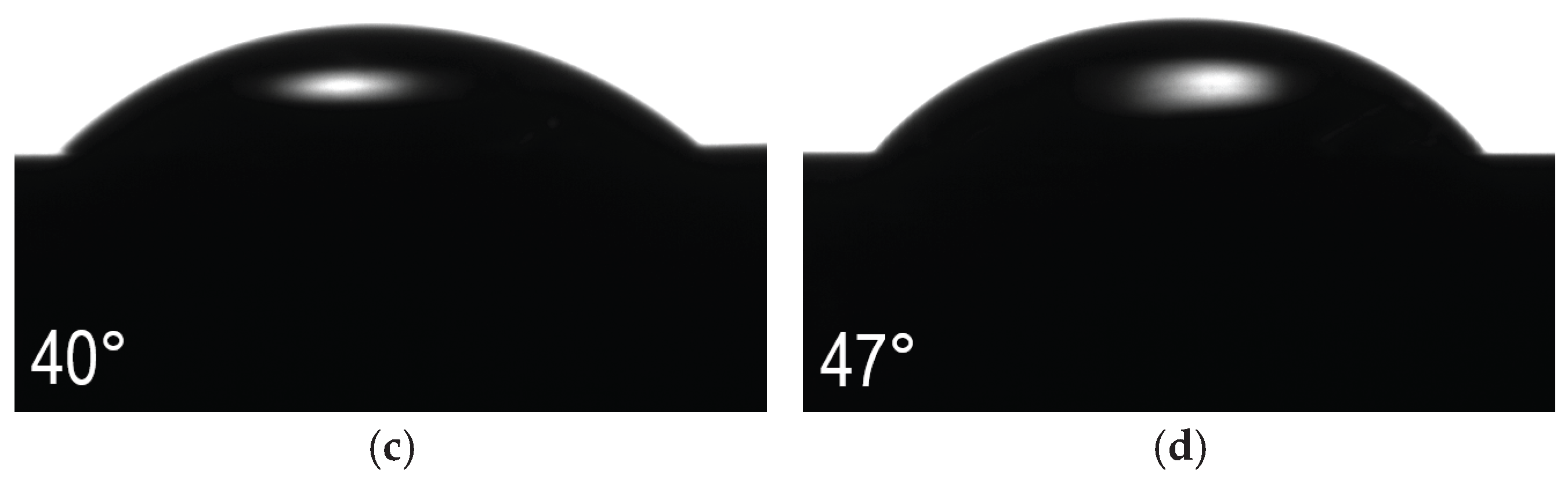

3.6. Wettability Analysis

The performed contact angle tests did not show any tendency linking this parameter with the increase in the steel oxidation temperature (

Figure 13). All tested sample variants showed smaller or larger hydrophilic properties (<90°). The highest contact angle is characterized by the surface oxidized at 400°C and is about 58° (

Figure 13b). The second largest angle is that obtained for the polished AISI 316L steel in the initial state (

Figure 13a). In this case, the contact angle was about 51°. Lower angle values, i.e. larger hydrophilic properties, were obtained for the steel after oxidation at 450°C and 500°C, which were about 40° and 47°, respectively (

Figure 13c,d). In the case of samples after oxidation at 450 °C and 500 °C, the most flattened water drops are visible, which indicates their greatest hydrophilicity, and therefore they may exhibit the best biological properties in contact with human tissue, however, their worse corrosion and friction wear resistance disqualify these materials. Steel oxidized at 400 °C exhibits the highest contact angle, but these are still good hydrophilic properties, and with very good values of the wear rate W

v and corrosion resistance exceeding in some parameters (I

corr, R

pol) the initial state is a prospective and promising material in terms of biomedical applications. Higher values of the contact angle may have also a positive effect when considering antibacterial properties.

4. Conclusions

The tests carried out on the surfaces of ASIS 316L austenitic steel after the oxidation processes at temperatures of 400° °C, 450 °C and 500 °C, in an air atmosphere allow to draw the following conclusions:

The phases formed on the surfaces after oxidation are Fe2O3 (hemetite) and Cr1.3Fe0.7O, and the layers obtained are very thin and could not be observed during the examination with a microscope on their cross-sections.

Roughness tests using an optical profilometer showed a tendency for the roughness to increase with the increase in the temperature of the oxidation process.

Due to their small thickness, the layers obtained did not significantly increase the microhardness of the tested steel. The hardness measured at the lowest loads (0.05, 0.1 kg) increased the most after oxidation at 400 °C.

The “ball-on-disc” tribological tests showed that the layer with the lowest roughness and the highest hardness, which was formed during oxidation at 400 °C, had a significant impact on the reduction of the friction coefficient and a very significant reduction of the wear rate. The explanation of the phenomenon of very good wear resistance obtained after this process requires in-depth analyses, which will be the subject of further research.

The corrosion tests showed a clear deterioration of the corrosion resistance of the steel after oxidation at the two highest temperatures (450 °C and 500 °C). The steel oxidized at 400 °C presented a corrosion potential and a breakdown potential slightly lower than the polished steel in its initial state, but in turn it obtained significantly better values of the corrosion current density and polarization resistance. After corrosion tests there are larger pits than on the steel in its initial state, but there are definitely fewer of them.

All surfaces of the tested samples showed a hydrophilic character. The steel after oxidation at 400 °C has the lowest surface wettability, which may also be the reason for the good corrosion resistance of this layer variant.

The steel changed colour to gold after oxidation, which may be a positive feature in some applications where decorative values are important.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.B. and H.W.; methodology, T.B. and H.W.; formal analysis, T.B., H.W. and B.A.-C.; investigation, T.B., H.W., M.S. and B.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.B. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, T.B.; visualization, T.B., H.W., M.S. and B.A.-C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nouri, A.; Wen, C. Stainless Steels in Orthopedics. In Structural Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 67–101 ISBN 978-0-12-818831-6.

- Heidari Laybidi, F.; Bahrami, A. Antibacterial Properties of ZnO-Containing Bioactive Glass Coatings for Biomedical Applications. Materials Letters 2024, 365, 136433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni, B.H.; Bahrami, A.; Rajabinezhad, M.; Abbasi, M.S.; Laybidi, F.H. Electrophoretic Deposition of Bioactive Glass 58S- xSi3N4 (0 < x < 20 Wt.%) Nanocomposite Coating on AISI 316L Stainless Steel Substrate for Biomedical Applications. Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 55, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; De Mongeot, F.B.; Ferrando, G.; Manzato, G.; Meyer, M.; Parodi, L.; Sgobba, S.; Sortino, M.; Vaglio, E. Study on Properties of AISI 316L Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion for High Energy Physics Applications. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2023, 1055, 168459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, F.G.B.; Tavares, S.S.M.; Perez, G.; Garcia, P.S.P.; Pimenta, A.R. Failure Investigation of an AISI 316L Pipe of the Flare System in an Off-Shore Oil Platform. Engineering Failure Analysis 2025, 167, 108939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T. Enhancing the Corrosion Resistance of Austenitic Steel Using Active Screen Plasma Nitriding and Nitrocarburising. Materials 2021, 14, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Georges, J.; Li, X.Y. Active Screen Plasma Nitriding of Austenitic Stainless Steel. Surface Engineering 2002, 18, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, M.; Çomaklı, O.; Yetim, T.; Yetim, A.F.; Çelik, A. Investigation of Mechanical, Tribological and Magnetic Properties after Plasma Nitriding of AISI 316L Stainless Steel Produced with Different Orientations Angles by Selective Laser Melting. Surface and Coatings Technology 2023, 467, 129676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Thirumurugesan, R.; Krishnakumar, S.; Rani, R.; Chandramouli, S.; Parameswaran, P.; Mythili, R. Performance Evaluation of Plasma Nitrided 316L Stainless Steel during Long Term High Temperature Sodium Exposure. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2023, 55, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, M.; Hu, J. Enhanced Plasma Nitriding Efficiency and Properties by Severe Plastic Deformation Pretreatment for 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 15, 1742–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M.; Miura, K.; Ohtsu, N. Hydrogen-Free Plasma Nitriding Process for Fabrication of Expanded Austenite Layer on AISI 316 Stainless Steel Surface. Materials 2025, 18, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Ma, C.; Hai, X.; Song, K. 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel Deformation Organization and Nitriding-Strengthened Layer Relationships. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatkalíková, V.; Drímalová, P.; Balin, K.; Slezák, M.; Markovičová, L. Electrochemical Behavior of Plasma-Nitrided Austenitic Stainless Steel in Chloride Solutions. Materials 2024, 17, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, B.; Kamiński, J.; Kulikowski, K.; Borowski, T.; Sobiecki, J.R.; Wierzchoń, T. The Effect of Nitriding Temperature of AISI 316L Steel on Sub-Zero Corrosion Resistance in C2H5OH. Materials 2024, 17, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriūnas, P.; Čerapaitė-Trušinskienė, R.; Galdikas, A. Modeling of Plasma Nitriding of Austenitic Stainless Steel through a Mask. Coatings 2024, 14, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardian-Tapia, R.; Rosales-Cadena, I.; Roman-Zubillaga, J.L.; Gonzaga-Segura, S.R. Mechanical and Microstructural Characterization of AISI 316L Stainless Steel Superficially Modified by Solid Nitriding Technique. Coatings 2024, 14, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corujeira Gallo, S.; Dong, H. Study of Active Screen Plasma Processing Conditions for Carburising and Nitriding Austenitic Stainless Steel. Surface and Coatings Technology 2009, 203, 3669–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.M.; Ignat, M.; Pinedo, C.E.; Tschiptschin, A.P. Structure and Properties of Low Temperature Plasma Carburized Austenitic Stainless Steels. Surface and Coatings Technology 2009, 204, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y.; Gong, J.; Somers, M.A.J. On the Fatigue Behavior of Low-Temperature Gaseous Carburized 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel: Experimental Analysis and Predictive Approach. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2020, 793, 139651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Gong, J. Exploration on the Fatigue Behavior of Low-Temperature Carburized 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel at Elevated Temperature. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2022, 850, 143562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, M.; Yoshida, D.; Yamauchi, N.; Ueda, N.; Sone, T.; Tanaka, S. Surface Material Design of 316 Stainless Steel by Combination of Low Temperature Carburizing and Nitriding. Surface and Coatings Technology 2005, 200, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgioli, F. The Expanded Phases Formed in Stainless Steels by Means of Low-Temperature Thermochemical Treatments: A Corrosion Perspective. Metals 2024, 14, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, C.X.; Dong, H.; Bell, T. Low Temperature Plasma Nitrocarburising of AISI 316 Austenitic Stainless Steel. Surface and Coatings Technology 2005, 191, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T.; Kulikowski, K.; Spychalski, M.; Rożniatowski, K.; Rajchel, B.; Adamczyk-Cieślak, B.; Wierzchoń, T. Mechanical Behavior of Nitrocarburised Austenitic Steel Coated with N-DLC by Means of DC and Pulsed Glow Discharge. Archives of Metallurgy and Materials 2022, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajzer, A.; Ceglarska, M.; Sura, N.; Kajzer, W.; Borowski, T.; Tarnowski, M.; Pilecki, Z. Effect of Nitrided and Nitrocarburised Austenite on Pitting and Crevice Corrosion Resistance of 316 LVM Steel Implants. Materials 2020, 13, 5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhai, L.; Xue, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Gong, J. Unusual Intermediate Layer Precipitation in Low-Temperature Salt Bath Nitrocarburized 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel. Surface and Coatings Technology 2024, 494, 131521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Jafarpour, S.; Dalke, A.; Biermann, H. Different Approaches for Plasma Nitrocarburizing of Austenitic Stainless Steel Using a Plasma-Activated Solid Carbon Precursor in a Hot-Wall Reactor. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2025, 34, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhai, L.; Xu, Y.; Wu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Gong, J. Low-Temperature Nitrocarburized 316L Stainless Steel: Residual Stress and Mechanical Properties. Surfaces and Interfaces 2025, 62, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Barua, A. Behavior of the S-Phase of Plasma Nitrocarburized 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel on Changing Pulse Frequency and Discharge Voltage at Fixed Pulse-off Time. Surface and Coatings Technology 2016, 307, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T.; Kulikowski, K.; Adamczyk-Cieślak, B.; Rożniatowski, K.; Spychalski, M.; Tarnowski, M. Influence of Nitrided and Nitrocarburised Layers on the Functional Properties of Nitrogen-Doped Soft Carbon-Based Coatings Deposited on 316L Steel under DC Glow-Discharge Conditions. Surface and Coatings Technology 2020, 392, 125705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Xu, Z.; Su, Z.; Li, Y.; Yi, A.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, K.; Chen, K.; Liao, Z.; et al. Mechanical Property and Biocompatibility of Multilayer Ti-DLC Films with Different Ti Target Power by Hybrid PVD/PECVD on 316L Stainless Steel. Surface and Coatings Technology 2025, 496, 131672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpanya, P.; Wongpinij, T.; Photongkam, P.; Siritapetawee, J. Improvement in Corrosion Resistance of 316L Stainless Steel in Simulated Body Fluid Mixed with Antiplatelet Drugs by Coating with Ti-Doped DLC Films for Application in Biomaterials. Corrosion Science 2022, 208, 110611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, A.; Pietri, A.D.; Ben Hjal, A.; Khodabakhshi, M.; Biasiolo, L.; Dabalà, M. Electrochemical and Localized Corrosion Characteristics of Kolsterised and DLC-Coated 316LVM Stainless Steel for Biomedical Applications. Applied Surface Science 2025, 693, 162808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, F.A.; Ramos, B.B.; Pereira, D.G.; Bendo, T.; Hammes, G.; De Mello, J.D.B.; Binder, C. Effect of Thermochemical Treatment as Buffer Layers on the Tribological Performance of Stainless Steel with DLC Films. Wear 2025, 205998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Chen, S.; Ma, M.; Yang, D.; An, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; et al. High-Loading 316L Stainless Steel by Integrated Low-Temperature Surface Nitriding and DLC Deposition. Surface and Coatings Technology 2025, 496, 131716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellesen, M.S.; Christiansen, T.L.; Hilbert, L.R.; Møller, P. Erosion–Corrosion and Corrosion Properties of DLC Coated Low Temperature Gas-Nitrided Austenitic Stainless Steel. Wear 2009, 267, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Abel, E.W. Reduction of Bacterial Adhesion on Modified DLC Coatings. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2008, 61, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Bell, T. Corrosion Properties of Active Screen Plasma Nitrided 316 Austenitic Stainless Steel. Corrosion Science 2004, 46, 1527–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Peng, K.; Wen, W.; Lu, D.; Long, J.; Meng, Y.; Peng, M.; Wei, F. Coupled Effects of TRIP and TWIP in Metastable Austenitic Stainless Steel via Optimization of Stacking Fault Energy. Materials Characterization 2025, 220, 114656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chakraborti, P.C.; Tarafder, S.; Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Analysis of Deformation Induced Martensitic Transformation in Stainless Steels. Materials Science and Technology 2011, 27, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Borgenstam, A.; Hedström, P. Comparing the Deformation-Induced Martensitic Transformation with the Athermal Martensitic Transformation in Fe-Cr-Ni Alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 766, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T.; Jeleńkowski, J.; Psoda, M.; Wierzchoń, T. Modifying the Structure of Glow Discharge Nitrided Layers Produced on High-Nickel Chromium-Less Steel with the Participation of an Athermal Martensitic Transformation. Surface and Coatings Technology 2010, 204, 1375–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Nabertherm tube furnace used for oxidation.

Figure 1.

Nabertherm tube furnace used for oxidation.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic appearance of the surface of AISI 316L steel in its initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c), 500 °C (d).

Figure 2.

Macroscopic appearance of the surface of AISI 316L steel in its initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c), 500 °C (d).

Figure 3.

3D images from an optical profilometer of the polished AISI 316L steel surface in its initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 3.

3D images from an optical profilometer of the polished AISI 316L steel surface in its initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction pattern of AISI 316L steel in its initial state.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction pattern of AISI 316L steel in its initial state.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction pattern of AISI 316L steel oxidized at 500 °C.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction pattern of AISI 316L steel oxidized at 500 °C.

Figure 6.

Microhardness of AISI 316L steel surface in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 6.

Microhardness of AISI 316L steel surface in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 7.

3D images of wear tracks of the polished surface of AISI 316L steel in its initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 7.

3D images of wear tracks of the polished surface of AISI 316L steel in its initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 8.

Wear profiles of polished AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 8.

Wear profiles of polished AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 9.

Graph of friction coefficient versus the number of revolutions of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 9.

Graph of friction coefficient versus the number of revolutions of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 10.

Wear rate of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 10.

Wear rate of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 11.

Polarization curves of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 11.

Polarization curves of AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Figure 12.

Corrosion damage of AISI 316L steel surface in initial condition (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 12.

Corrosion damage of AISI 316L steel surface in initial condition (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 13.

Contact angles and drops of distilled water on the surface of AISI 316L steel in the initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Figure 13.

Contact angles and drops of distilled water on the surface of AISI 316L steel in the initial state (a) and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C (b), 450 °C (c) and 500 °C (d).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of AISI 316L (1.4404) steel (wt %), according to the PN-EN 10027-2 standard.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of AISI 316L (1.4404) steel (wt %), according to the PN-EN 10027-2 standard.

| C |

Cr |

Mn |

Mo |

N |

Ni |

P |

S |

Si |

| ≤ 0.03 |

16-18 |

≤ 2 |

2-3 |

≤ 0.1 |

10-14 |

≤ 0.045 |

≤ 0.03 |

≤ 1 |

Table 2.

Roughness parameters Ra and Rz of steel in the initial state and oxidized layers at 400, 450 and 500 °C.

Table 2.

Roughness parameters Ra and Rz of steel in the initial state and oxidized layers at 400, 450 and 500 °C.

| Material |

Ra [nm] |

Rz [nm] |

| AISI 316L |

33.1 ± 2.9 |

989.6 ± 76.6 |

| 400 °C |

51.1 ± 1.1 |

1933.0 ± 274.8 |

| 450 °C |

84.2 ± 2.0 |

5266.7 ± 222.7 |

| 500 °C |

190.7 ± 8.6 |

11231.6 ± 71.7 |

Table 3.

Electrochemical values obtained from potentiodynamic curves for AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

Table 3.

Electrochemical values obtained from potentiodynamic curves for AISI 316L steel in the initial state and after oxidation processes at temperatures: 400 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C.

| Material |

icorr [nA/cm2] |

Ecorr [mV] |

Rpol [kΩ∙cm2] |

Epit [mV] |

| AISI 316L |

227 ± 138 |

-28 ± 14 |

468 ± 153 |

420 ± 8 |

| 400°C |

41 ± 14 |

-62 ± 19 |

909 ± 217 |

398 ± 26 |

| 450°C |

79 ± 18 |

-177 ± 8 |

275 ± 51 |

267 ± 14 |

| 500°C |

109 ± 14 |

-196 ± 15 |

190 ± 17 |

160 ± 16 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).