1. Introduction

The development of the additive manufacturing technology is becoming increasingly evident, especially across the methods based on material deposition using directed energy (Directed Energy Deposition, DED) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Additive manufacturing is among the fastest growing production techniques of this day and age. It consist in layered application of material in powder or wire until the desired object shape is obtained. Such technologies are particularly widespread in the area of rapid prototyping of complex machine parts. They make it possible to create objects, including metal ones, in a cost-effective and flexible manner, without the need for specialised tools. Unlike traditional manufacturing methods, additive manufacturing techniques enable full process automation, from the design stage to final production, which significantly increases their efficiency.

Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) is a technology that employs an electric arc as an energy source to melt metal wire, which is subsequently deposited, layer by layer, to build three-dimensional objects [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The process uses of standard welding wire, which makes it relatively inexpensive, and does not require significant logistics to obtain the resource. WAAM is classified among high-throughput additive processes, enabling fabrication of even large-size parts [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Given the nature of the process, which involves significant amounts of energy being generated, the microstructure of the parts manufactured becomes heterogeneous, which typically leads to increased internal stresses and hardness.

Some of the characteristics of the microstructures obtained by way of additive manufacturing are as follows [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]:

- −

variable grain size within the material;

- −

directional grain orientation—usually vertical, and parallel to the material deposition direction.

The latter of the characteristic features of the materials obtained by the WAAM method is attributed to the formation of a temperature gradient between successive layers over the course of heating, leading to preferential vertical grain growth. Consequently, the material microstructure becomes anisotropic, and its mechanical properties, such as strength, vary depending on the said direction. One of the effective ways to improve the structure and mechanical properties of materials is heat treatment which follows the additive manufacturing process. As mentioned in paper [

26], heat treatment can successfully decrease residual stresses, thus reducing the risk of workpiece deformation over time. The studies described in papers [

27,

28] confirm that heat treatment has a beneficial effect on the plastic properties of components manufactured using this technology. Gunen et al. [

29] also observed that processes such as homogenising and boriding can significantly reduce the wear and friction coefficient of stainless steel components produced by WAAM.

The authors of paper [

30] also demonstrated that the WAAM method can be applied to produce materials of favourable mechanical properties, and particularly to improve their impact strength, by way of dedicated multi-stage heat treatment using a fluidised bed furnace for isothermal procedures. The treatments they discussed also yielded almost complete defragmentation of columnar grains which, however, caused a decrease in surface hardness.

The favourable changes observed in connection with the technology developed, combining austenitisation, martensitic quenching in mineral oil, annealing, and austempering in a fluidised bed, provided foundations for the continuation of research on the heat treatment processes adapted to the specific characteristics of materials produced by additive manufacturing, which, however, will use industrial furnaces based on oil coolants. The outcome of the research in question was the development of the heat treatment technology described in this paper.

Considering the potential practical application of the technology in question, namely in the production of individual workpieces required for the repair of machinery operating in severe environmental conditions, it was decided that, once manufactured and treated, the workpieces would be subjected to tribocorrosion wear processes in order to demonstrate their resistance to the combined effects of environmental factors such as abrasive wear and corrosion. The foregoing was due to the fact that friction nodes in machines often operate in electrolytic and abrasive environments [

31,

32]. The problem of tribocorrosion wear of the iron alloys produced by additive manufacturing methods has virtually been undiagnosed [

33,

34].

It is also noteworthy that yet another particularly important and difficult problem is obtaining a microstructure of structural materials that ensures sufficiently high resistance to tribocorrosion. The material must be characterised by high abrasion hardness, while being immune to the corrosive effects of the operating environment, at the same time. To produce such a complex set of material properties (e.g., by way of adequate heat treatment) is a complicated endeavour. It is so because treatments that increase material hardness typically reduce its resistance to corrosion (e.g., hardening increases hardness and abrasion resistance, but the stresses introduced into the material increase its susceptibility to corrosion).

The goal of the research addressed in this paper was to identify the parameters of a new method of heat treatment of materials obtained by the WAAM method as well as to assess the impact of advanced heat treatment based on mineral coolants, as proposed by the authors, on the resistance of the ferrous alloy subject to tests to tribocorrosion in 3.5% NaCl as well as to purely mechanical wear. What the article provides is an analysis of the relationship between the properties of the material developed by the manufacturing technology in question (including dedicated heat treatment) and the elementary mechanisms causing wear, especially under the conditions of tribocorrosion. With this goal in mind, the authors compared the results of wear tests of heat-treated samples with those of base reference (non-treated) samples. The analysis of the test results implied a probable mechanism of the effect of increased material impact strength (being the heat treatment effect) on the reduction of tribocorrosion wear. It should be emphasised that such studies of the tribocorrosion properties of heat-treated WAAM prints represent a novelty, given the state of the art.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

As part of the rapid prototyping experiment, a ferrous alloy produced using a flux-cored wire of 1.6 mm in diameter was used, and its chemical composition was as follows: 0.21% C, 0.8% Si, 1.29% Mn, 1.34% Cr. The exact chemical composition of the said wire and the MAG process parameters have been provided in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively. This kind of wire is commonly used for hard facing, and its typical applications include regeneration of rolling wheels, conveyor rollers, rolls, shafts, and other machine components.

The choice of this particular material for testing was based on the results obtained by computer simulations in the JMatPro software, dilatometric tests as well as previous studies [41] which had confirmed its high heat treatability.

Before the process commenced, the base surface had been thoroughly cleaned mechanically and degreased to ensure optimal adhesion conditions. No additional cooling was used over the course of the entire process.

The experimental rapid prototyping process was conducted on a 20 mm thick plate made of the S690QL1 steel. A structure composed of seven layers was produced, each of which consisted of eight seams.

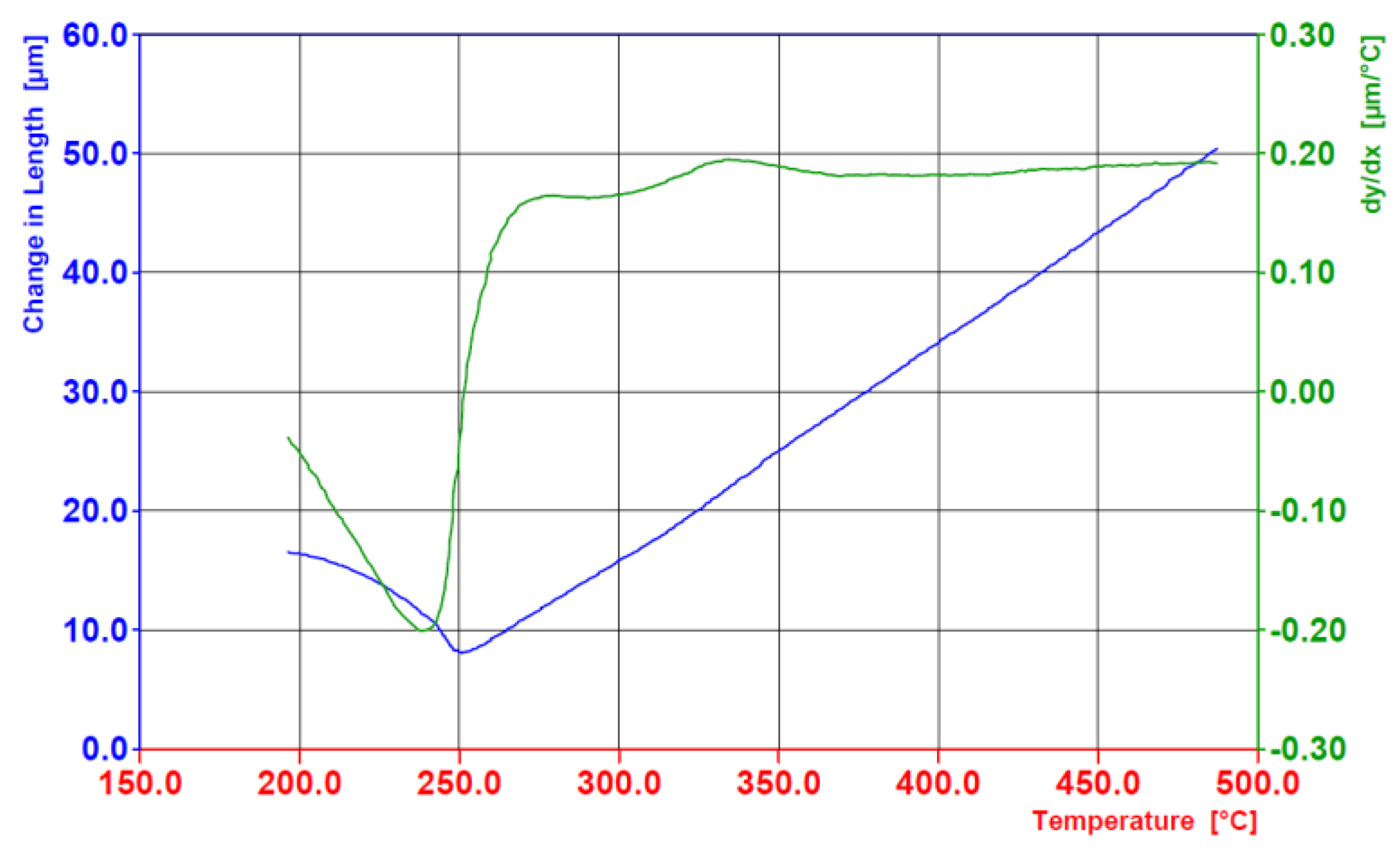

The authors had developed an original and innovative heat treatment technology for the ferrous alloy tested, the main purpose of which was to remove grain anisotropy and obtain a multiphase structure characterised by increased plasticity and impact strength. This procedure is based, among other factors, on microstructure fragmentation. The heat treatment process was designed on the basis of the computer simulations performed in the JMatPro software as well as the aforementioned dilatometric tests (see

Figure 2), which made it possible to define the parameters of consecutive treatments and their optimal combination.

Figure 1.

Dilatometric graph of the material produced by WAAM after annealing.

Figure 1.

Dilatometric graph of the material produced by WAAM after annealing.

The heat treatment process developed by the authors consisted of four major stages:

- −

austenitising, during which the material was heated to 950 °C and held at this temperature for 15 minutes,

- −

martensitic quenching in mineral oil, directly following austenitisation,

- −

annealing, conducted at 760 °C for 60 minutes,

- −

austempering, conducted at 260 °C for 180 minutes.

2.2. Mechanical Tests

The samples used for testing of mechanical properties and tribocorrosion wear were cut out from the material produced by the WAAM method. To ensure uniform conditions, all the samples were taken parallel to the deposition layers, at a minimum distance of 5 mm from the die surface. Thus prepared, the samples were divided into two groups: one representing the reference material, while the second group was heat treated in a manner adapted to the chemical composition of the material.

A series of tests were performed to assess the mechanical properties of the material before and after the heat treatment.

Static tensile testing—the static tensile tests were performed on a Zwick/Roell Z250 universal testing machine. The tests were conducted in accordance with PN-EN ISO 6892-1:2010 at room temperature. Five-time samples with a measuring diameter of 6 mm were used, applying a constant strain rate of 0.001s−1.

Impact testing—the impact test was performed on standardised samples of 55×10×10 mm in dimensions with a V notch in accordance with PN-EN ISO 148-1:2010. A Zwick/Roell RKP450 Charpy impact hammer with a nominal energy of 300 J was used for the measurements.

Hardness testing—the hardness measurements were performed on the flat surfaces of samples cut out in a manner analogous to the samples used for strength and impact testing. A stationary HR-150 hardness tester was used to determine this parameter.

2.3. Microstructural and Phase Characteristics

A SUPRA 35 type high-resolution scanning electron microscope (SEM) from Zeiss was used to identify the microstructure and the surface wear mechanism of the materials tested, both before and after heat treatment. The observations were conducted by secondary electron (SE) detection. The phase composition was analysed using an X’Pert PRO MPD X-ray diffractometer (XRD) from Panalytical. The device was fitted with a cobalt anode lamp (λKα = 0.179 nm) and a PIXcel 3D detector. The Bragg-Brentano geometry measurements were performed within the 2Θ angle range from 5° to 110° with a 0.05° step and a counting time of 100 s per step. The diffractograms were subject to a qualitative phase analysis performed using the HighSore Plus software (v. 3.0e) and the dedicated PAN-ICSD database.

2.4. Tribological Tests

A test rig based on a ball-on-plate model system [

30,

34] was used to assess wear resistance. The following samples were used in the tests:

- −

cube-shaped samples with 10 mm edges,

- −

counter-samples (balls) made of Al2O3 with a diameter of 7.0 mm.

All the tests were performed with a load of 10 N and a sliding speed of approx. 18 mm/s. Under each test, the ball, driven by an eccentric mechanism, slid back and forth across the sample surface over a distance of 6 mm for approx. 40 minutes. The total friction distance was 43.2 m. Each test was repeated three times.

After the wear tests were completed, profilometric measurements of the wear marks were taken. Based on these measurements, the volumetric material loss was estimated. For purposes of further analysis, it was assumed that volumetric wear would be a measure of the material’s resistance to tribocorrosion and mechanical wear only.

The research experiment was designed so as to identify the individual components of tribocorrosion wear (ZT) in line with the following relationship:

where: Z

M—material loss caused exclusively by mechanical interactions, Z

C—material loss caused exclusively by corrosive interactions, ΔZ—synergistic effect of friction and corrosion.

The total tribocorrosion wear (ZT) was determined in 3.5% NaCl at the free corrosion potential. In a series of additional independent experiments conducted under cathodic polarisation conditions, the purely mechanical component (ZM) was determined. The polarisation potential applied (approx. -900 mV (SCE)) eliminated corrosive effects in 3.5% NaCl. The component (ZC) corresponding to the purely corrosive wear was estimated using Faraday’s equation. The relevant calculations were performed for the specific corrosion current density and test duration time. The measure of the combined effect of friction and corrosion is the ΔZ factor, which can be determined by transforming equation 1.

During the tribocorrosion tests, the potential was measured in the test system with the sample using a potentiostat from ATLAS Sollich. A calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode, while a platinum mesh was used as the auxiliary electrode. The potentiostat was also used to determine polarisation curves and to assess the corrosion resistance of the materials studied.

3. Results

3.1. Mikrostruktura i Właściwości Mechaniczne

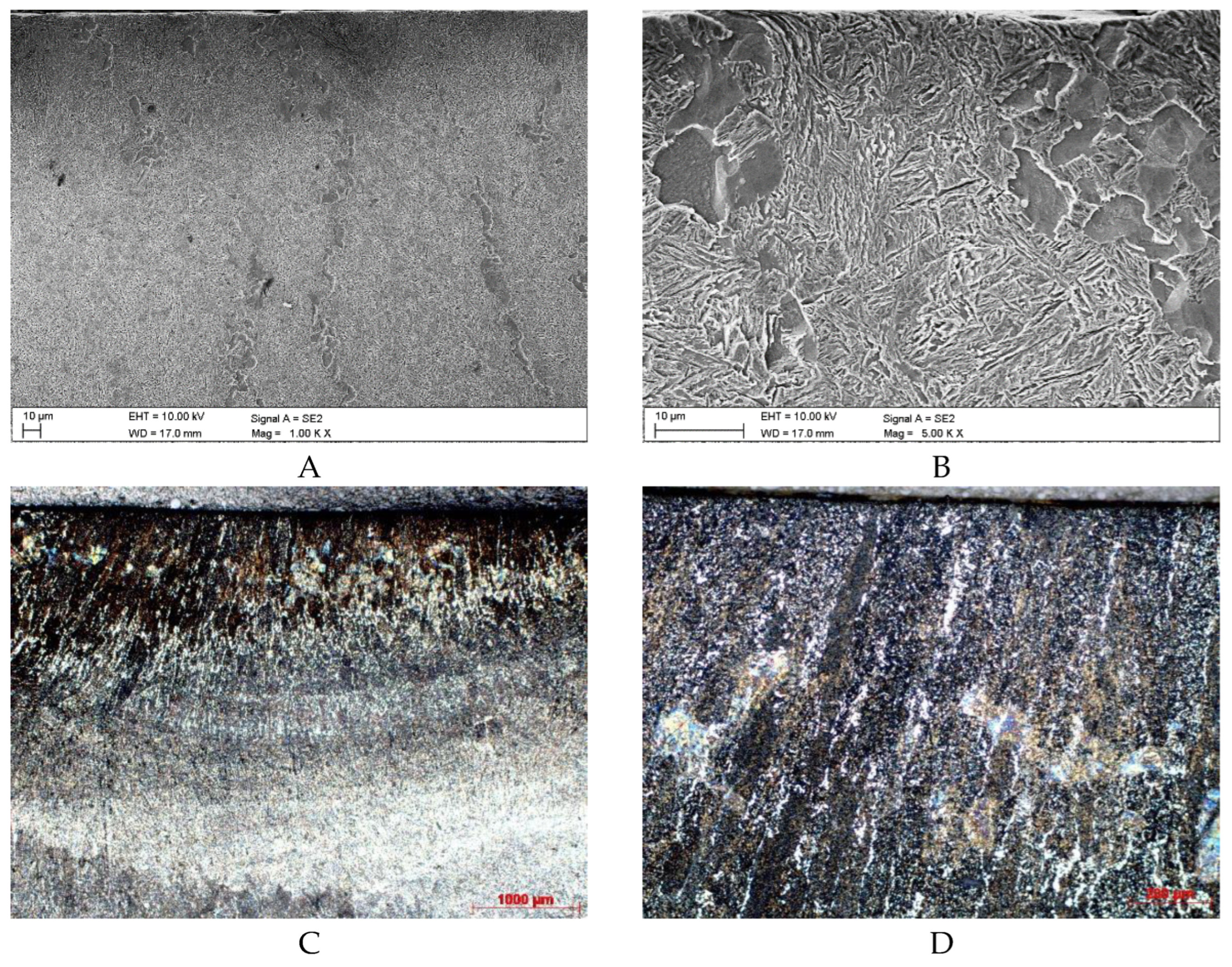

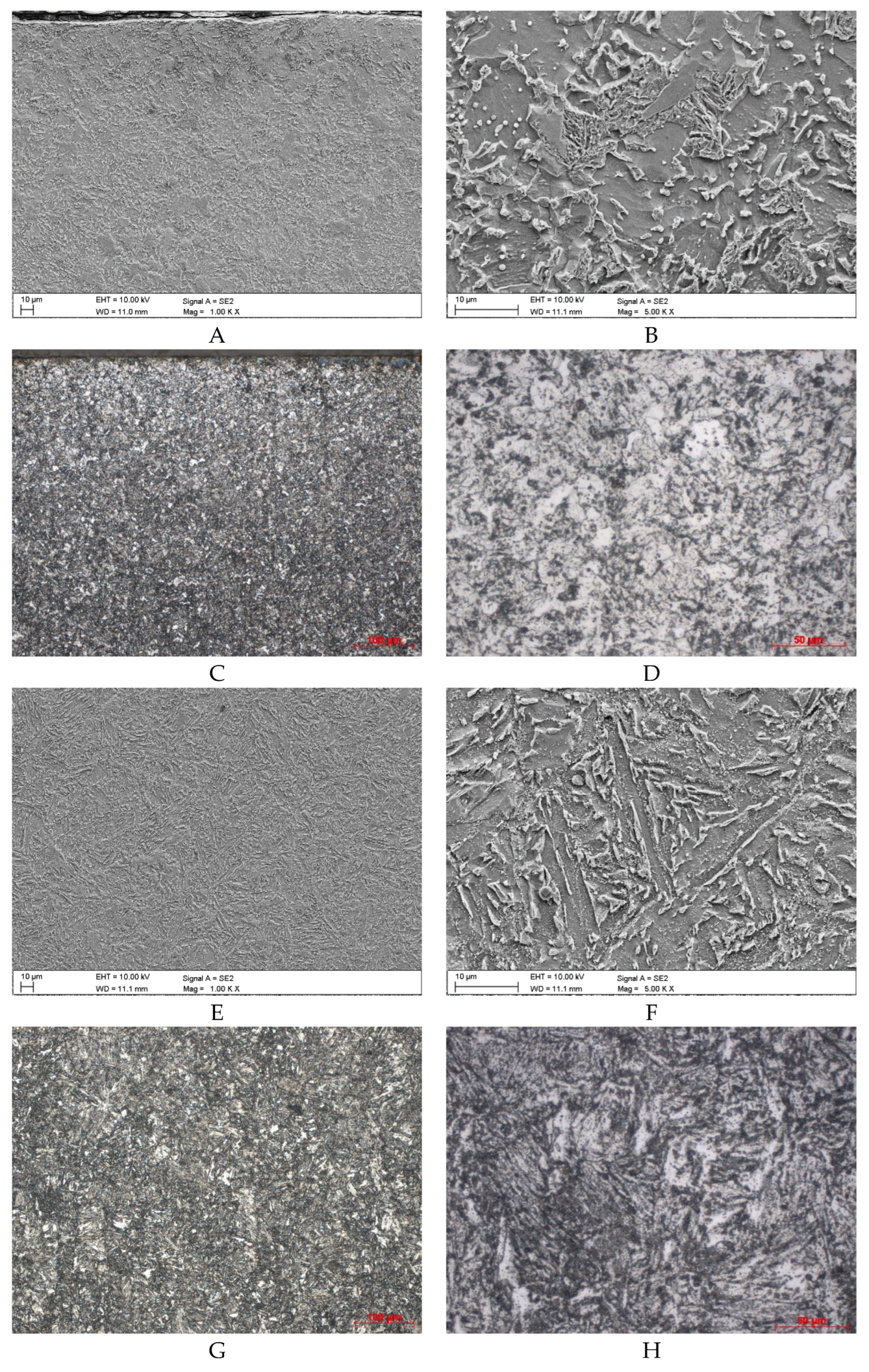

Figure 2 shows the initial microstructure of the material obtained by the WAAM method (Variant A), while

Figure 2 shows it after the heat treatment (Variant B).

Figure 2.

Microstructures obtained for variant A; A—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×1000; B—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×5000; C—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×25; D—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×100; E—found in the core, SEM, ×1000; F—found in the core, SEM, ×5000; G—found in the core, LM, ×100; H—found in the core, LM, ×500.

Figure 2.

Microstructures obtained for variant A; A—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×1000; B—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×5000; C—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×25; D—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×100; E—found in the core, SEM, ×1000; F—found in the core, SEM, ×5000; G—found in the core, LM, ×100; H—found in the core, LM, ×500.

The phase composition of the microstructure in the near-surface area of the sample under Variant A is significantly diversified. There are heat-affected zones (

Figure 2A–D) where the grains display different shapes. The area directly underlying the surface, to the depth of approx. 1 mm, is dominated by darker columnar grains. They are oriented perpendicularly to the layer applied and comprise a mixture of bainite and martensite, separated by thin layers of ferrite. Some of these elongated grains are in direct contact with the surface.

What continues to be observed in the material core (

Figure 2E,G), at a magnification of ×100, is partially directional nature of the structure with a predominance of bainite, but analysis of individual areas shows no explicit grain orientation (

Figure 2F,H).

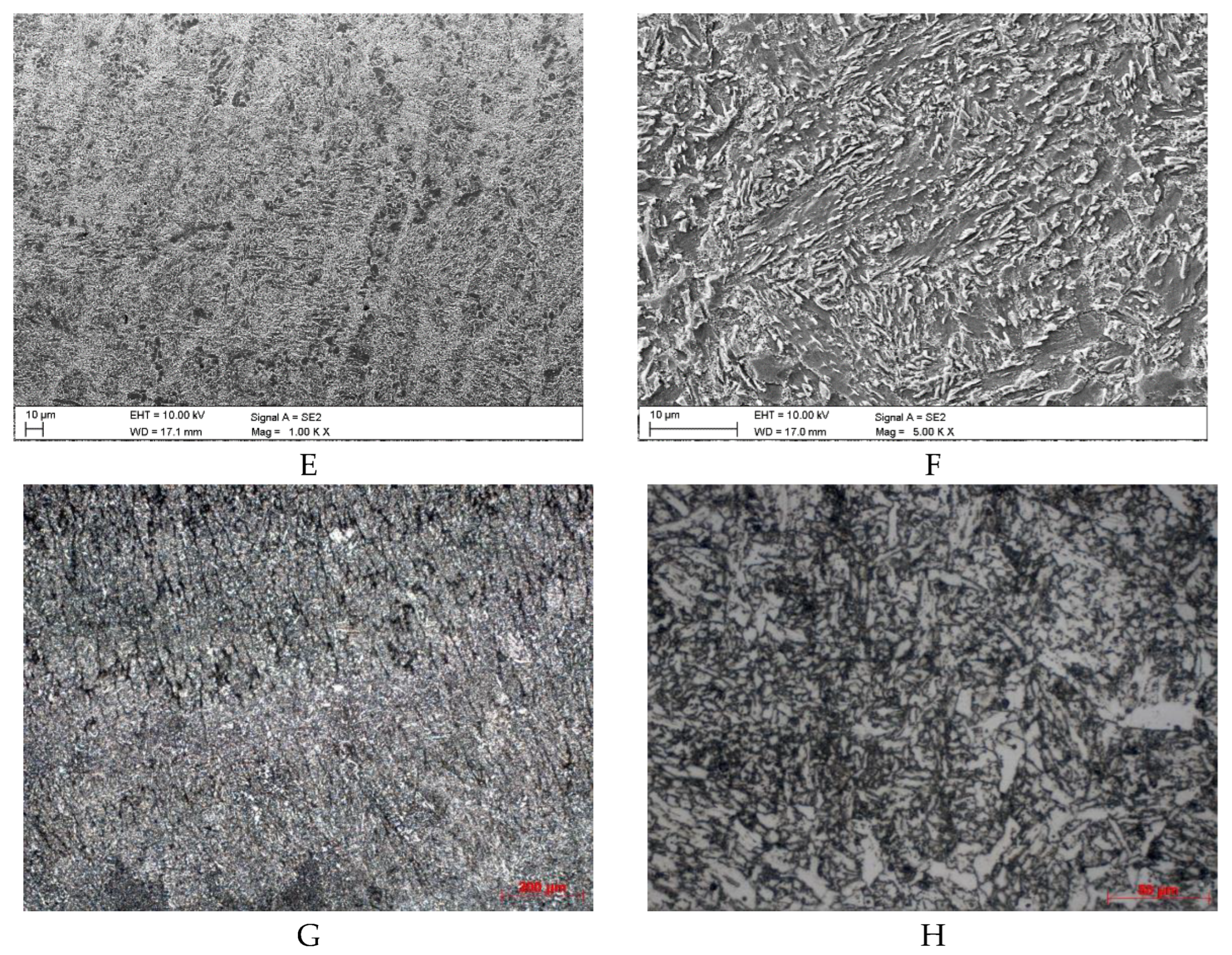

In the case of Variant B (

Figure 3A÷D), no columnar grains or other forms of directionally oriented phase are observed in the surface layer. The resulting ferritic-bainitic structure, perceived as a homogeneous phase, shows no organised arrangement, with grains distributed randomly and multidirectionally.

The middle part’s microstructure (

Figure 3E,G) in the heat-treated sample (Variant B) comprises ferrite (light phase), which did not transform during incomplete austenitisation, and bainite, which was formed as an outcome of the transition of austenite over the course of isothermal soaking. This structure is far more ordered than that obtained for Variant 1. One can observe an explicitly layered arrangement of bainite plates separated by ferrite (

Figure 3F,H).

A comparison of

Figure 2H with

Figure 3H clearly shows that the innovative heat treatment led to considerable fragmentation of the originally elongated grains. This process demonstrates the beneficial effect of the method developed by the authors on the microstructure of the material produced by the WAAM technique.

However, it should be noted that the original heat treatment procedure in question did not lead to phase transformations, as confirmed by the results of the XRD phase composition tests of the materials tested, shown in

Figure 4. The peaks visible in this figure are associated exclusively with the alpha iron, which confirms the occurrence of ferritic and bainitic phases.

3.2. Tests of Mechanical Properties

Table 3 contains the results of the tests of the mechanical properties of the iron alloy Fe (0.21% C, 0.8% Si, 1.29% Mn, 1.34% Cr). They were conducted to compare the material in the as-produced (Variant A) and heat-treated (Variant B) condition.

The heat treatment caused significant changes in the alloy’s most important properties:

- −

hardness reduced by approx. 7 HRC, which could be interpreted as a direct result of the increased ferrite share in the near-surface layer following the heat treatment,

- −

yield strength decreased by approx. 25%,

- −

maximum strength decreased by approx. 15%,

- −

impact strength increased by 43 J/cm2, which represents an impressive increase of 238% compared to the reference material (Variant A).

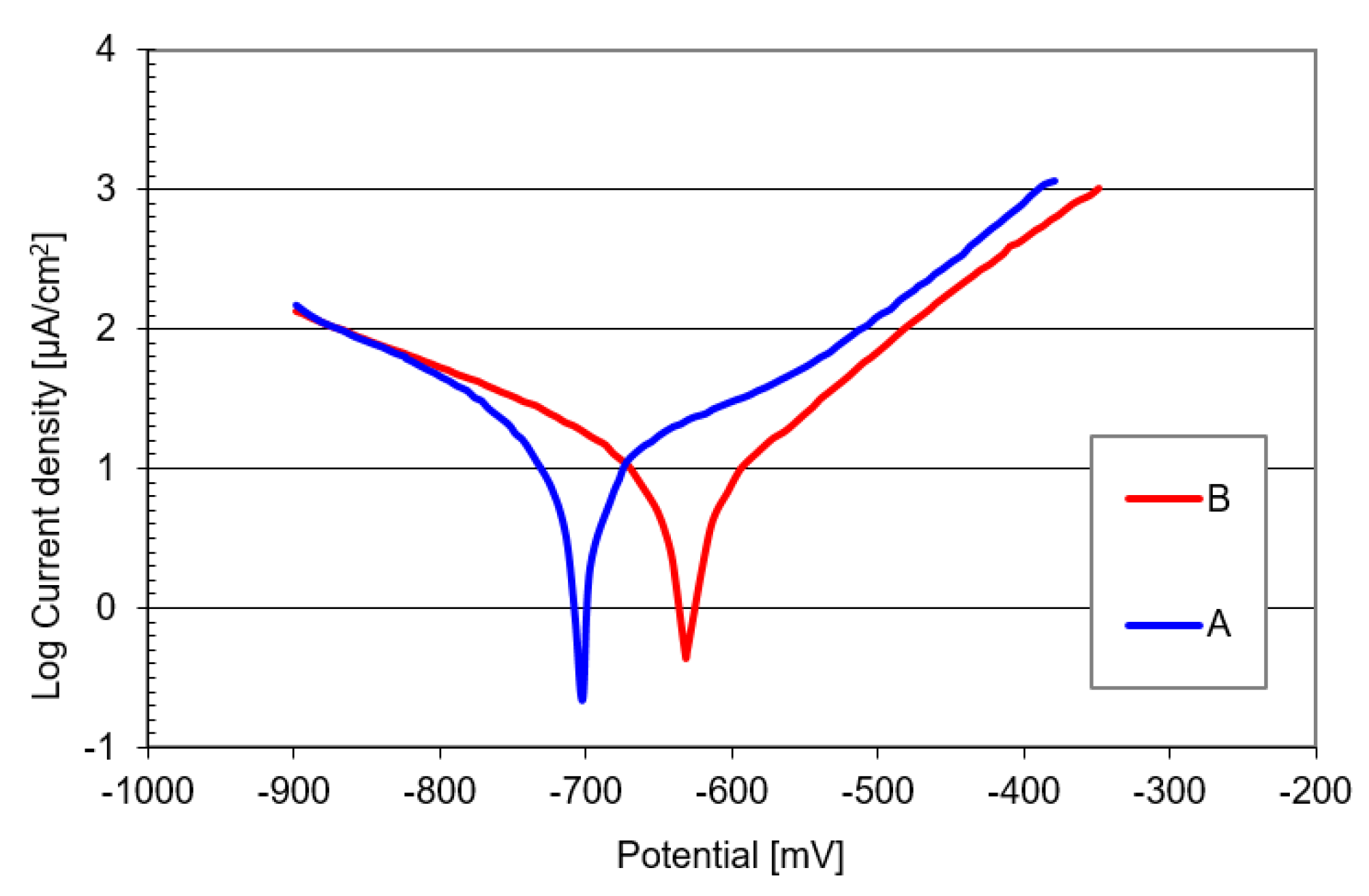

3.2. Corrosion Resistance

The corrosion resistance of the materials studied in 3.5% NaCl was assessed on the basis of polarisation curves. The characteristics determined for both the material variants subject to tests have been presented in

Figure 5. Based on the polarisation curves plotted for them, their corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (icorr) were established using the Tafel method. The results thus obtained have been provided in

Table 4. The lower corrosion current density implies higher corrosion resistance in 3.5% NaCl of the heat-treated material (Variant B).

3.3. Tribocorrosion Results

Table 5 contains the values of the material loss following tribocorrosion tests and that observed under purely mechanical wear conditions (with cathodic polarisation). The data include the average values obtained in a series of measurements and the standard deviation. Additionally, the component of the friction and corrosion synergy effect (ΔZ) was estimated. Analysis of the data provided in

Table 5 implies that the samples subjected to the specialised heat treatment procedure (Variant B) show less wear under tribocorrosion conditions in a 3.5% NaCl solution. The average material loss in these samples was approximately 2.59·10

–3 mm

3. In the base samples (Variant A), the material loss was greater and amounted to approx. 3.59·10

–3 mm

3. Lower wear values were also recorded under purely mechanical conditions when studying Variant B (1.75·10

−3 mm

3) in comparison with Variant A (2.49·10

−3 mm

3). For both these material variants subject to testing under tribocorrosion conditions, a clear synergy effect of friction and corrosion was observed, representing more than 30% of the total material loss.

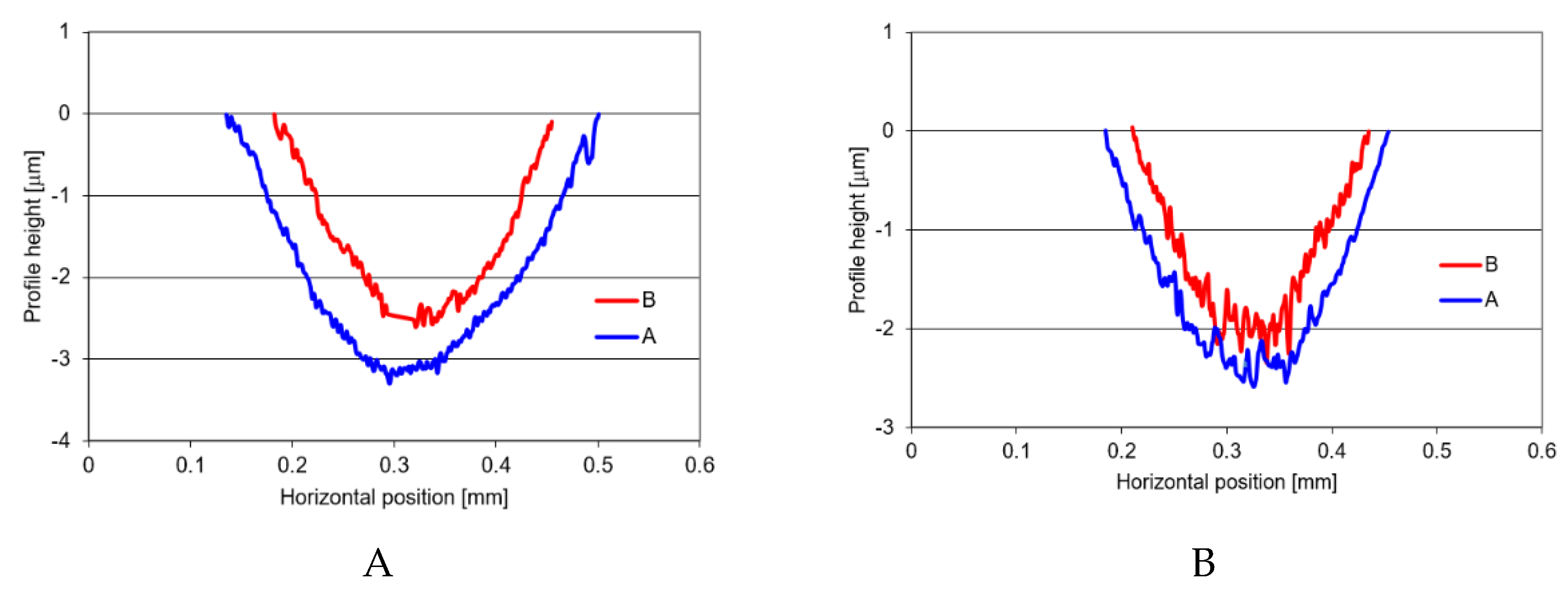

The wear mark profiles established in the studies have been provided in

Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Wear profiles established for: A—tribocorrosion wear (ZT), B—mechanical wear only (ZM).

Figure 5.

Wear profiles established for: A—tribocorrosion wear (ZT), B—mechanical wear only (ZM).

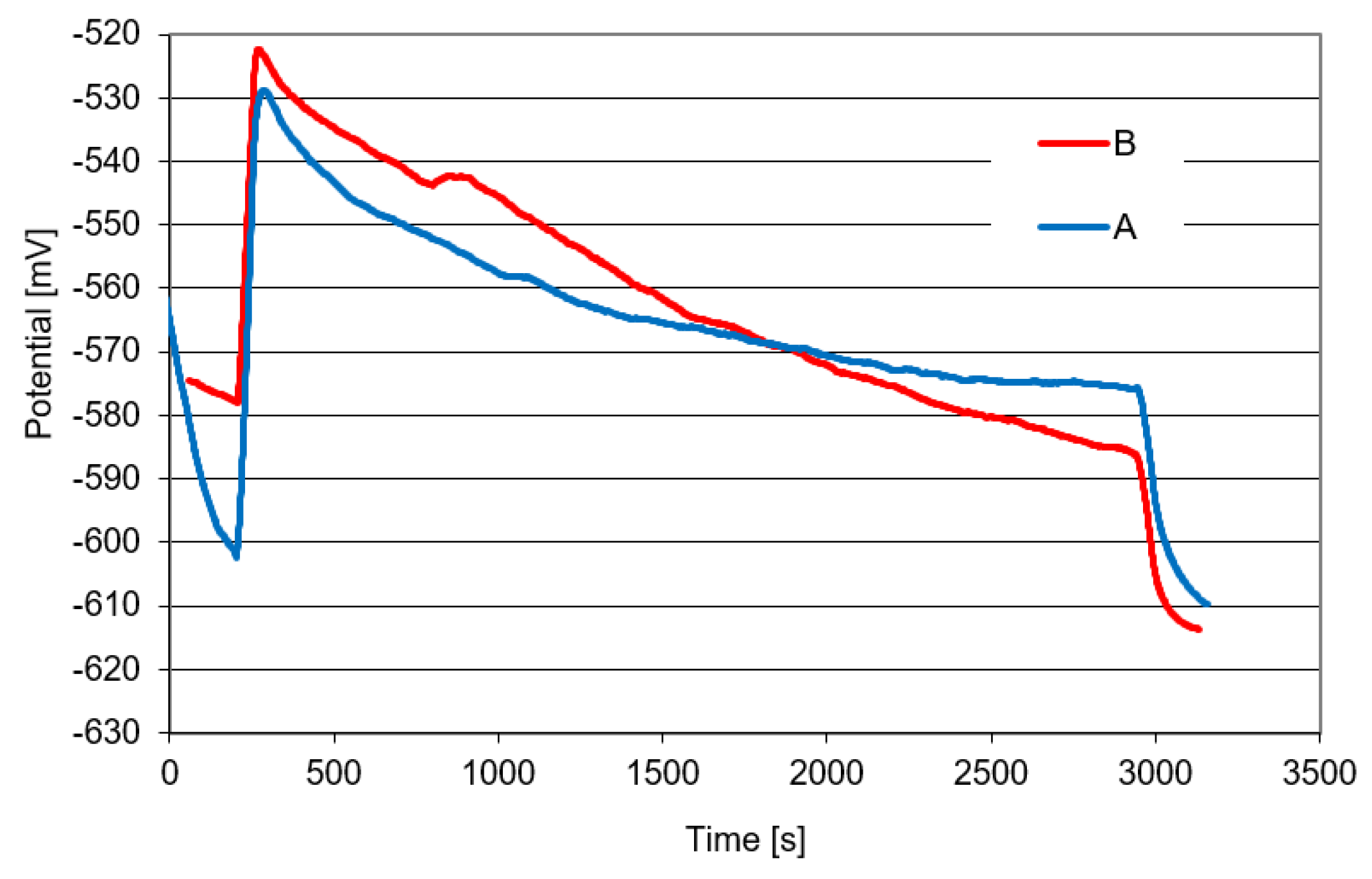

Over the course of the wear tests, changes in the electrochemical potential of the system were monitored, as shown in

Figure 6. The graphs demonstrate that both the material variants examined are not capable of passivation in a 3.5% NaCl solution. Having immersed the sample in the NaCl solution, without any friction, one could observe an initial potential decrease. This is attributable to the formation of a thin layer of corrosion products on the material surface. When friction begins (counter-sample movement), this corrosion layer is removed. The wear area acquires a more positive potential than the remainder of the sample surface, causing a noticeable potential increase. On the other hand, when the friction forcing is stopped, the potential decreases again.

After the tests had been completed, the hardness in the wear mark area was measured. No considerable material consolidation was observed, as the hardness measured inside the wear mark did not diverge significantly from the material hardness outside this area.

Figure 6.

Changes in the potential of the material variants examined under tribocorrosion test conditions.

Figure 6.

Changes in the potential of the material variants examined under tribocorrosion test conditions.

3.4. Worn Surface Damage

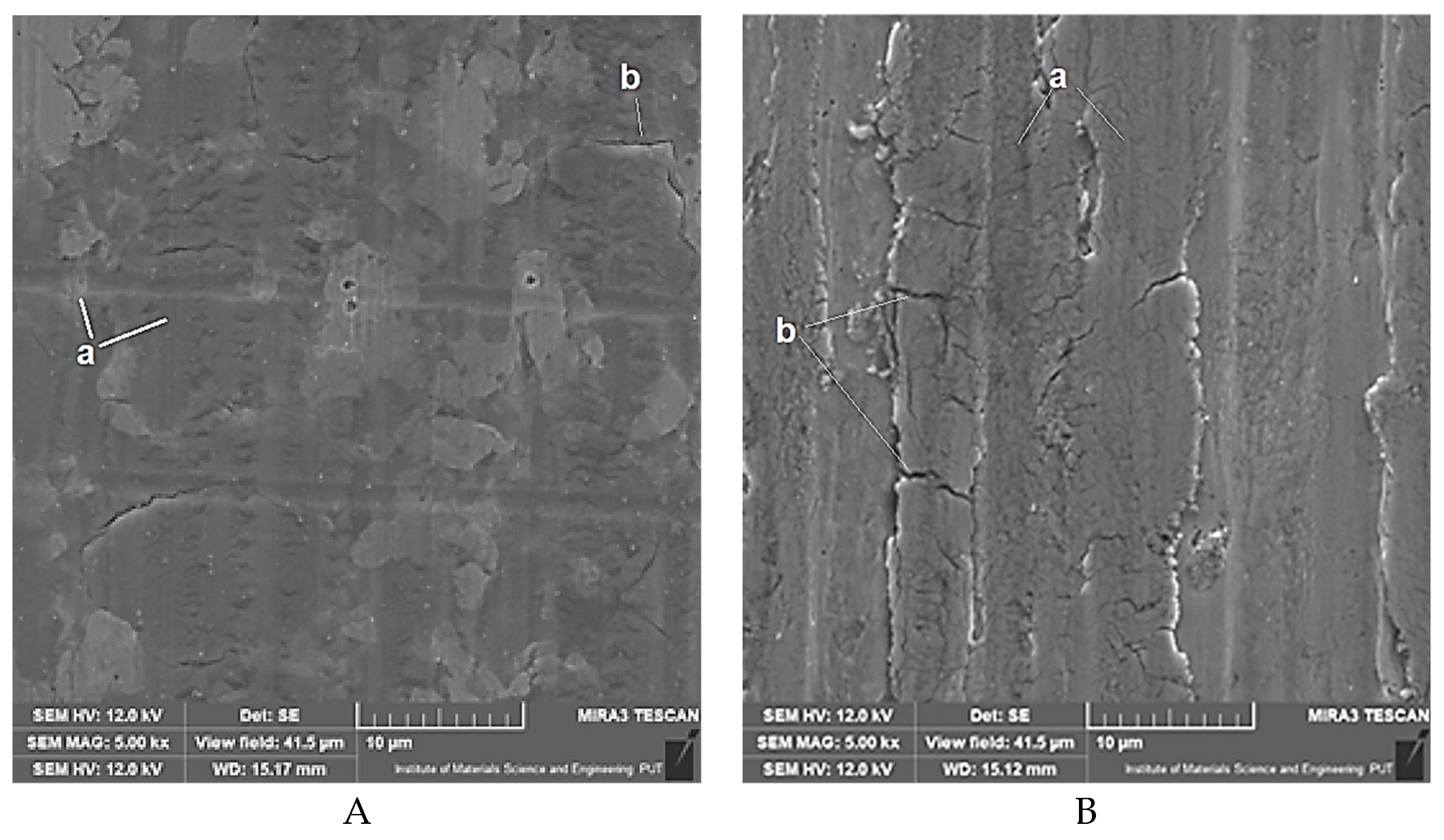

Once the tests had been completed, microscopic observations of the wear surface were conducted.

Figure 7 shows examples of the wear marks observed in the base samples (Variant A) obtained under tribocorrosion and purely mechanical wear conditions. The corresponding marks found in the heat-treated samples (Variant B) have been shown in

Figure 8.

The photographs depicting the wear marks indicate that the predominant mechanism of material removal is abrasion. There are numerous parallel grooves visible on the surface of most samples, resulting from the micro-abrasion of the sample material by harder coarse protrusions of the moving counter-sample (balls). These grooves are particularly visible on the wear marks observed under the conditions of purely mechanical forcing and in the reference base material (Variant A). The heat-treated material (Variant B) is characterised by lower hardness, which makes it more susceptible to plastic strain. Under such conditions, grooving is more likely to occur than micro-abrasion. On the other hand, under the conditions of tribocorrosion, corrosion processes may cause partial removal of micro-abrasion marks (grooves being shallower and less numerous). What can also be seen on the surface of the wear marks is microcracks, especially with mechanical forcing at play.

4. Discussion

The heat treatment proposed by the authors made it possible to cause favourable changes in the microstructure. In the core zone of the samples, a bainite structure embedded in a ferritic matrix was formed (

Figure 3A–D), while in the near-surface zone, significant fragmentation of columnar grain was observed (

Figure 3E–H). These structural modifications translated into significant improvement in the material properties. Variant B, compared to the base material (Variant A), exhibits better plasticity, facilitating plastic deformation. Despite the reduction in hardness by approx. 30% and in yield strength by approx. 25%, the main benefit is a more than threefold increase in impact strength, as confirmed by the data in

Table 3.

The test results provided (

Figure 5,

Table 5) prove that the heat treatment proposed by the authors improves the wear resistance of the material examined. Compared to the base samples (Variant A), the samples subjected to the innovative heat treatment (Variant B) showed less volume loss following wear tests, both under tribocorrosion and purely mechanical wear conditions.

The relationship observed in the material variants examined is not obvious, because the material of a significantly lower (by 30%) hardness shows less wear. However, thanks to the dedicated heat treatment, the impact strength of this material (Variant B) is more than three times higher. In order to explain the effect of the higher impact strength of the material (on lower hardness) on the wear reduction, the authors have applied the energy model of the wear process proposed by G. Fleischer [

35,

36].

The concept concerns a friction node where two bodies come into contact under load. Friction energy is generated as a result of the frictional interactions associated with the mutual displacement of these bodies. This energy is absorbed by the more susceptible element of the friction couple. According to the model, each body can accumulate a certain amount of this energy in the near-surface layer. Once the critical energy threshold is exceeded, the deformed volume of the near-surface layer breaks off, thus forming a new wear particle. The detachment of the deformed micro-volume can be attributed to the development of micro-cracking.

What G. Fleischer’s energetic wear model takes into account is the elementary mechanisms of material removal identified on the surface of the wear marks in the samples subject to tests. The wear marks visible in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 imply that the frictional contact with the hard surface of the counter-sample causes plastic strain of the near-surface layer of the sample material. Such a strain can lead to the immediate breaking off of the deformed micro-volume of the material as a result of micro-abrasion (especially in the case of the base material (Variant A), characterised by higher hardness and lower impact strength). The strain can also cause grooving without immediate material detachment. However, in the area of the locally deformed near-surface layer, micro-cracking may be initiated. When repeated on a cyclical basis, frictional effects promote the development of micro-cracks until the wear particle breaks off. Micro-cracks are visible on the surface of the wear marks (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). In line with the energetic interpretation of the wear process, it can be assumed that the impact strength of the material (KCV) may be a factor which determines the value of the critical energy required for the wear particle to break off as a consequence of cracking. Previously released, papers [

37,

38] describe studies which have demonstrated experimentally that the value of abrasive wear in sliding couples correlates more strongly with the impact strength of the material examined than with its hardness.

With reference to the energetic concept of the wear process, the authors of this paper have adopted a simplifying assumption that the aforementioned critical energy (required for the wear particle to break off) is proportional to the product of the material’s impact strength (KCV) and area A within which the material detachment occurs. The aforementioned area A can be approximated as the actual area of frictional contact between the sample and counter-sample AR. In the case of plastic strain, the real area of contact of the friction couple depends on the force affecting the friction node (F) and the material hardness (H):

In the heat-treated samples (Variant B), the threshold energy required for the wear particle to break off is higher than in the non-treated samples (Variant A). This conclusion is illustrated by the following inequalities:

The heat-treated material (Variant B) is characterised by higher impact strength (

Table 3) and, most likely, a larger real contact area. However, the hardness of this material (

Table 3) is lower. Consequently, the real contact between the sample and the counter-sample occurs over a larger area.

Ultimately, the heat-treated samples (Variant B) show a higher critical energy required to for the wear particle to detach. It is due to this fact that more energy must be supplied to the friction node in order to remove the deformed near-surface layer of the material. To achieve this effect by way of wear, more contact interactions are necessary. The wear particle breaks off after a longer time than in the case of non-treated samples (Variant A). The relationship between impact strength and the elementary mechanisms of material removal, as described above, may explain the lower wear (especially under mechanical forcing conditions) of the heat-treated samples.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusions arising from the studies and analyses discussed in the article are as follows:

It has been confirmed that it is possible to produce workpieces of high plastic properties from Fe (0.21% C, 0.8% Si, 1.29% Mn, 1.34% Cr) alloys by way of additive welding methods and advanced heat treatment. Microscopic observations and phase tests have shown that the heat treatment proposed by the authors, being a combination of austenitising, martensitic quenching, annealing, and austempering, enables comminution of the columnar grain in the ferrous alloy produced by WAAM.

The heat-treated material (Variant B) shows significantly lower tribocorrosion and mechanical wear. It is also characterised by higher wear resistance, even though the dedicated heat treatment has caused its hardness to drop (by approx. 30%).

In line with the description of the interactions in the friction node examined, as proposed by the authors of the article, the wear resistance of the analysed ferrous alloy improves as a consequence of increased impact strength. The heat-treated material (Variant B), offering lower hardness, is more susceptible to plastic strain during frictional interactions. However, the detachment of deformed micro-areas of the near-surface layer occurs after a longer time than in the base material (Variant A). The main reason for this phenomenon may be the higher critical energy required for the wear particles to break off. The value of the said critical energy is determined by the increase in the impact strength of the heat-treated material (Variant B), being more than threefold.

The heat treatment proposed in the article improves the corrosion resistance of the material subject to the studies in 3.5% NaCl. In the heat-treated samples (Variant B), the corrosion current density was found to be approximately 40% lower. Consequently, this also causes less material loss due to corrosion processes occurring on the sample surface, in the areas exposed to friction under tribocorrosion conditions (these processes being the main cause of the friction-corrosion synergy effect).

The advanced heat treatment proposed in the article is an example of a technological procedure which makes it possible to achieve a specific combination of material properties (increased resistance to abrasion and the corrosive effects of 3.5% NaCl) that is particularly favourable in terms of tribocorrosion resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.W.; methodology; A.N.W., validation, M.S.W. and P.N.; formal analysis, A.G. and S.M.; investigation, A.S., P.N., A.G., S.M. and M.S.; resources, M.S.W. and S.M.; data curation, A.N.W; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and A.N.W, writing — review and editing, M.S.W.; visualization, P.N. and M.S.; supervision, A.N.W. and M.S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The presented research results were conducted within the framework of completed projects: 1. The Silesian University of Technology, Excellence Initiative—Research University program implemented at the Silesian University of Technology, the year 2020, project no. 06/020/SDU/10-21-01 entitled. ‘Development of an innovative method for improving the functional properties of manufactured components by electron beam rapid prototyping’. 2. Łukasiewicz—Upper Silesian Institute of Technology, Development Fund project no. BW-30/ZB.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blakey-Milner, B.; Gradl, P.; Snedden, G. Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—Process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Götzendorfer, B.; Esen, C.; Hellmann, R. Design Rules for Hybrid Additive Manufacturing Combining Selective Laser Melting and Micromilling. Materials 2021, 14, 5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.K.; Moroni, G.; Vaneker, T.; Fadel, G.; Campbell, I.; Gibson, I.; Bernard, A.; Schulz, J.; Graf, P.; Ahuja, B. Design for Additive Manufacturing: Trends, opportunities, considerations, and constraints. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derekar, K.S. A review of wire arc additive manufacturing and advances in wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminium. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.Z.; Alkahari, M.R.; Rosli, N.A.B.; Hasan, R.; Sudin, M.N.; bin Ramli, F.R. Review of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing for 3D Metal Printing. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2019, 13, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, P.; Ruiz-Navas, E.M.; Gordo, E. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) for Aluminum-Lithium Alloys: A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harshita, P.; Anisha, A.; Sutha, G.G. Applications of wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) for aerospace component manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 4995–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivántabernero; Paskual, A.; Álvarez, P. Study on Arc Welding Processes for High Deposition Rate Additive Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2018, 68, 358–362.

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Duarte, V.; Miranda, R.M.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J.P. Current Status and Perspectives on Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). Materials 2019, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L. Wire and Arc Additive Manufacture (WAAM) Reusable Tooling Investigation. Ph.D. Thesis, Cranfield University, Bedford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martina, F.; Williams, S.W. Wire+arc additive manufacturing vs. traditional machining from solid: A cost comparison. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 32, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. An investigation into the comparative costs of additive manufacturing vs. machine from solid for aero engine parts. InCost Effective Manufacturing via Net-Shape Processing, meeting proceedings RTO-MP-AVT-139, pages 17–1–17–10. Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 2006.

- Buchanan C, Wan W, Gardner L. Testing of wire and arc additively manufactured stainless steel material and cross-sections. Ninth International Conference on Advances in Steel Structures. Hong Kong: China; 2018.

- Busachi, A.; Erkoyuncu, J.; Colegrove, P.; Martina, F.; Ding, J. Designing a WAAM Based Manufacturing System for Defence Applications. Procedia CIRP 2015, 37, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.I.; Wang, J.; Qin, J.; He, Y.; Shepherd, P.; Ding, J. A Review of WAAM for Steel Construction—Manufacturing, Material and Geometric Properties, Design, and Future Directions. Structures 2022, 44, 1506–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin W, Zhang C, Jin S, Tian Y, Wellmann D, Liu W. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Stainless Steels: A Review. Applied Sciences 2020;10(5):1563. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Zhang Y, Gao M, Wang F, Li Q, Zeng X. Effects of milling thickness on wire deposition accuracy of hybrid additive/subtractive manufacturing. Science and Technology of Welding and Joining 2019;24(5):375–81. [CrossRef]

- Nagamatsu H, Sasahara H, Mitsutake Y, Hamamoto T. Development of a cooperative system for wire and arc additive manufacturing and machining. Additive Manufacturing 2020;31:100896. [CrossRef]

- Gordon JV, Haden CV, Nied HF, Vinci RP, Harlow DG. Fatigue crack growth anisotropy, texture and residual stress in austenitic steel made by wire and arc additive manufacturing. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2018;724:431–8. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Ma Z, Chen G, Liu C, Ma D, Ma S. Obtaining fine microstructure and unsupported overhangs by low heat input pulse arc additive manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2017;27:198–206. [CrossRef]

- Bermingham MJ, StJohn DH, Krynen J, Tedman-Jones S, Dargusch MS. Promoting the columnar to equiaxed transition and grain refinement of titanium alloys during additive manufacturing. Acta Materialia 2019;168:261–74. [CrossRef]

- DebRoy T, et al. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—Process, structure and properties. Progress in Materials Science 2018;92:112–224. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Wang D, Han F. Effect of crystalline grain structure on the mechanical properties of twinning-induced plasticity steel. Theoretical & Applied Mechanics Letters 2016;32(1):181–7. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Wang Z, Xiao Y, Horstemeyer M, Cui X, Chen L. Insight into the mechanisms of columnar to equiaxed grain transition during metallic additive manufacturing. Additive Manufacturing 2019;26:22–9. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan C, Gardner L. Metal 3D printing in construction: A review of methods, research, applications, opportunities and challenges. Engineering Structures 2019;180:332–48. [CrossRef]

- Brandl E, Baufeld B, Leyens C, Grault R. Additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V using welding wire: comparison of laser and arc beam deposition and evaluation with respect to aerospace material specifications. Physics Procedia 2010;5:595–606. [CrossRef]

- Bermingham MJ, Kent D, Zhang H, StJohn DH, Dargusch MS. Controlling the microstructure and properties of wire arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V with trace boron additions. Acta Materialia 2015;91:289–303. [CrossRef]

- Günen, A., Gürol, U., Koçak, M., & Çam, G. (2023). A new approach to improve some properties of wire arc additively manufactured stainless steel components: Simultaneous homogenization and boriding. Surface & Coatings Technology, 460, 129395. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A.N.; Stachowiak, A.; Marciniak, S.; Gołaszewski, A.; Staszuk, M.; Węglowski, M.S.; Rykała, J.; Kowalski, M. Improving the tribocorrosion resistance by increasing the impact strength of an iron alloy manufactured by the wire arc additive manufacturing method. Wear, 572–573, 2025, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tuszyński, W.; Michalczewski, R.; Osuch-Słomka, E.; Snarski-Adamski, A.; Kalbarczyk, M.; Wieczorek, A.N.; Nędza, J. Abrasive Wear, Scuffing and Rolling Contact Fatigue of DLC-Coated 18CrNiMo7-6 Steel Lubricated by a Pure and Contaminated Gear Oil. Materials 2021, 14, 7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawk J.A., Wilson R.D, Tylczak J.H., Doğan Ö.N., Laboratory abrasive wear tests: investigation of test methods and alloy correlation. Wear 225-229, 2, 1999, 1031-1042. [CrossRef]

- Munoz A.I., Espallargas N., Mischler S., Tribocorrosion. Cham (Switzerland): Springer International Publishing, 2020.

- Stachowiak A., Wieczorek A.N., Comparative tribocorrosion tests of 30CrMo12 cast steel and ADI spheroidal cast iron. Tribology International, 155, 2021, 106763. [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, G., Energetische Methode der Bestimmung des Verschleißes. Schmierungstechnik, 4, 9–12, 1973.

- Fleischer, G.; Gröger, H.; Thum, H. Verschleiß und Zuverlässigkeit; VEB Verlag Technik: Berlin, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano O.A., A Review on the Effect of Impact Toughness and Fracture Toughness on Impact-Abrasion Wear. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 30, 2021, 7101–7116. [CrossRef]

- Salesky W.J., Thomas G., Medium Carbon Steel Alloy Design for Wear Applications. Wear 75 (1), 1982, 21–40. [CrossRef]

Figure 3.

Microstructures obtained for variant B; A—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×1000; B—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×5000; C—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×25; D—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×100; E—found in the core, SEM, ×1000; F—found in the core, SEM, ×5000; G—found in the core, LM, ×100; H—found in the core, LM, ×500.

Figure 3.

Microstructures obtained for variant B; A—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×1000; B—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, SEM, ×5000; C—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×25; D—found in the near-surface area of the cross-section, LM, ×100; E—found in the core, SEM, ×1000; F—found in the core, SEM, ×5000; G—found in the core, LM, ×100; H—found in the core, LM, ×500.

Figure 4.

Diffractograms of the materials examined.

Figure 4.

Diffractograms of the materials examined.

Figure 5.

Polarisation curves of the materials examined (3.5% NaCl).

Figure 5.

Polarisation curves of the materials examined (3.5% NaCl).

Figure 7.

Wear marks on the surface of non-heat treated samples (Variant A) following tests under tribocorrosion conditions (A) and under mechanical wear conditions (B); designations: a—grooves, b—crack.

Figure 7.

Wear marks on the surface of non-heat treated samples (Variant A) following tests under tribocorrosion conditions (A) and under mechanical wear conditions (B); designations: a—grooves, b—crack.

Figure 8.

Wear marks on the surface of heat-treated samples (Variant B) following tests under tribocorrosion conditions (A) and mechanical wear conditions (B); designations: a—grooves, b—crack.

Figure 8.

Wear marks on the surface of heat-treated samples (Variant B) following tests under tribocorrosion conditions (A) and mechanical wear conditions (B); designations: a—grooves, b—crack.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the material subject to tests [wt.%].

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the material subject to tests [wt.%].

| C, % |

Si, % |

Mn, % |

Cr, % |

Mo, % |

Ni, % |

| 0.201±0.013 |

0.995±0.14 |

1.444±0.174 |

1.214±0.171 |

0.036±0.005 |

0.033±0.005 |

Table 2.

Parameters of the WAMM prototyping process.

Table 2.

Parameters of the WAMM prototyping process.

| Current I, A |

Wire feed speed Vd, m/min |

Arc voltage U, V |

Travel speed Vp, cm/min |

Shielding

gas |

| 235-240 |

4.8±0.1 |

23.3±0.1 |

25±0.1 |

M21 |

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of the material examined, in as-produced and heat-treated condition.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of the material examined, in as-produced and heat-treated condition.

| Variant No. |

A |

B |

| Material condition |

Without heat treatment |

Heat-treated |

| Hardness, HRC |

27±1 |

20±1 |

| Impact strength KCV, J/cm2

|

18±1 |

61±2 |

| Yield point Re, MPa |

656±7 |

494±5 |

| Maximum strength Rm, MPa |

920±9 |

777±8 |

Table 4.

Corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (icorr) of the materials examined.

Table 4.

Corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (icorr) of the materials examined.

| Material |

Ecorr, mV (SCE) |

icorr, µA/cm2

|

| Variant A |

-699 ± 32 |

17.3 ± 1.5 |

| Variant B |

-633 ± 27 |

9.2 ± 1.0 |

Table 5.

Results of the tests of wear processes.

Table 5.

Results of the tests of wear processes.

| Material |

Material loss in the tribocorrosion (ZT) |

Mechanical component (ZM) |

Corrosion component (ZK) |

Synergistic effect

(ΔZ) |

ΔZ/ZT

|

| mm3·10−3

|

mm3·10−3

|

mm3·10−3

|

mm3·10−3

|

% |

| Variant A |

3.59 ± 0.16 |

2.49 ± 0.12 |

0.027 |

1.10 |

31 |

| Variant B |

2.59 ± 0.14 |

1.75 ± 0.09 |

0.013 |

0.83 |

32 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).