1. Introduction

Dark energy is a mysterious energy component that

has been observed to be driving the accelerated expansion of the universe, and

have defied several explanations since its discovery in supernova observations [

1] Its existence has since been confirmed by

several independent observations like the Planck measurements of the Cosmic

Microwave Background (CMB), indicating that it accounts for about 68.3% of the

gravitating energy content of the universe [

2].

This is in addition to the older dark matter mystery of gravitationally

attractive but invisible energy component constituting about 26.8% of the

gravitating energy content of the universe. Only about 4.6% is in the form of

visible baryonic matter.

The cosmological constant (Λ) earlier introduced

into Einstein’s Field Equations, while being the simplest solution, results in

a conflict between measured density of dark energy and the 120 orders of

magnitude larger value predicted from quantum field theory [

3]. The Λ problem has defied logical solution from

supersymmetric cancellation approach, relaxation of vacuum energy [

4] and anthropic approach [

5]. It also defies an approach that simply makes

the spacetime metric insensitive to Λ [

6].

Slowly evolving scalar field models like quintessence

is one of the prominent alternative approaches to solve the dark energy mystery

without the Λ route. We also have modified gravity models and unification of

dark energy and dark matter. See Ref. [

7] for

detailed review and Refs.[

8,

9] for recent review.

The amount of theoretical and observational efforts

that has been applied to understand dark energy and dark matter shows that they

require new physics beyond the existing standard model of cosmology and

particle physics. Attempts to resolve the dark matter mystery can be mainly

classified as either a modification of gravity or introduction of new particles

beyond the standard model of particle physics. However, both approaches of

modified gravity and particle dark matter have failed to provide consistent

explanations to the dark matter mystery even though each approach tends to

explain some observations and fail at some others.

There is an approach that explains dark matter as

gravitational polarization of vacuum energy by baryonic matter without invoking

new particle or modifying gravity in the traditional sense [

10]. It is based on the idea that matter and

antimatter have opposite gravitational charges which requires a violation of

the Weak Equivalence Principle. Preliminary findings from measurements of

antiproton to proton charge to mass ratio imply that matter and antimatter

gravitate the same way [

11]. Furthermore, the

recent result from the ALPHA collaboration has ruled out the possibility of

gravitationally repulsive antimatter [

12].

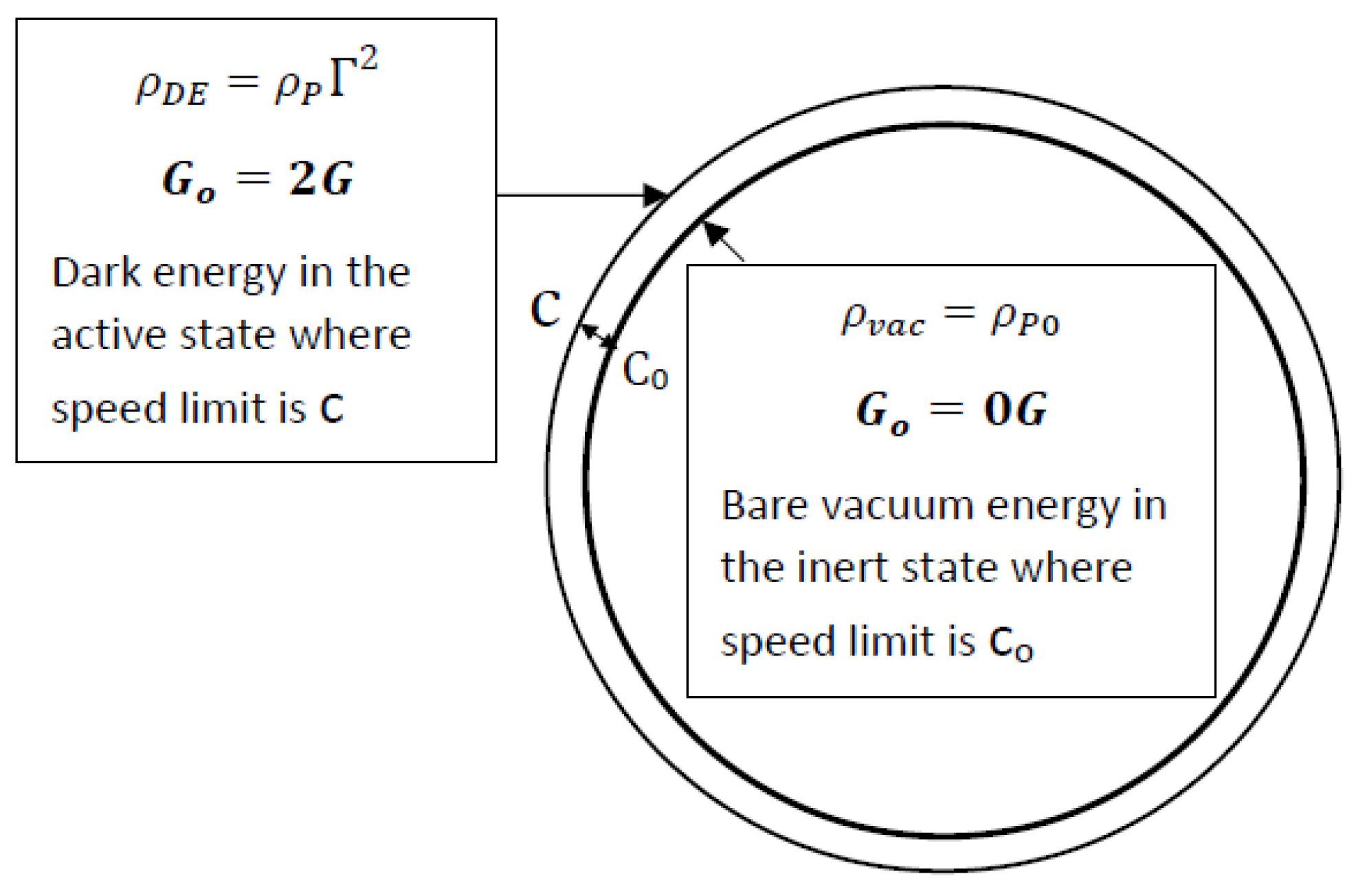

In this paper, the dark energy and dark matter

puzzle are tackled using the framework of Extra Dimension Symmetry (EDS) that

doubles the number of large extra dimensions with microscopic partners. EDS

provides a solution to the dark energy puzzle by placing the bare vacuum energy

component in a gravitationally inert state where the actual gravitational

constant

Go= 0G. Due to

a speed limit asymmetry and energy density constraint, a non zero component

spills into the gravitationally active state where

Go= 2G, as

dark energy. For dark matter, it relies on the background effect of neutrinos

which induces a nonzero gravitational constant in the inert state, enabling the

gravitation of virtual particles which appears as dark matter. This neutrino

substrate approach for dark matter neither requires the polarization of the

quantum vacuum nor opposite gravitational charges for particles and

antiparticles like in [

10].

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 discusses the key dimensional

symmetry that doubles the number of large spatial dimensions with microscopic

partners. It also discusses the speed constraint, the two on and off

gravitational states, their speed limit asymmetry and density constraint, which

is then applied in section 4 to provide a solution to the Λ problem.

Section 3 discusses General Relativity in a

large extra dimension and explores its unique features of gravitational

inversion as well as the chain of causality in gravitation. It is shown that

the expansion of a time-like spatial dimension is quantitatively equivalent to

the curvature of our visible spatial dimensions.

Section 4 discusses the emergence of dark

energy due to a speed limit asymmetry and energy density constraint discussed

in section 2, while in section 5, the key reheating prediction is discussed.

Section 6 discusses the gravitation of virtual

particles which appears as dark matter due to the background effect of neutrino

substrates which induces nonzero gravitational constant in the inert state.

Discussion and conclusion follows in

Section 7.

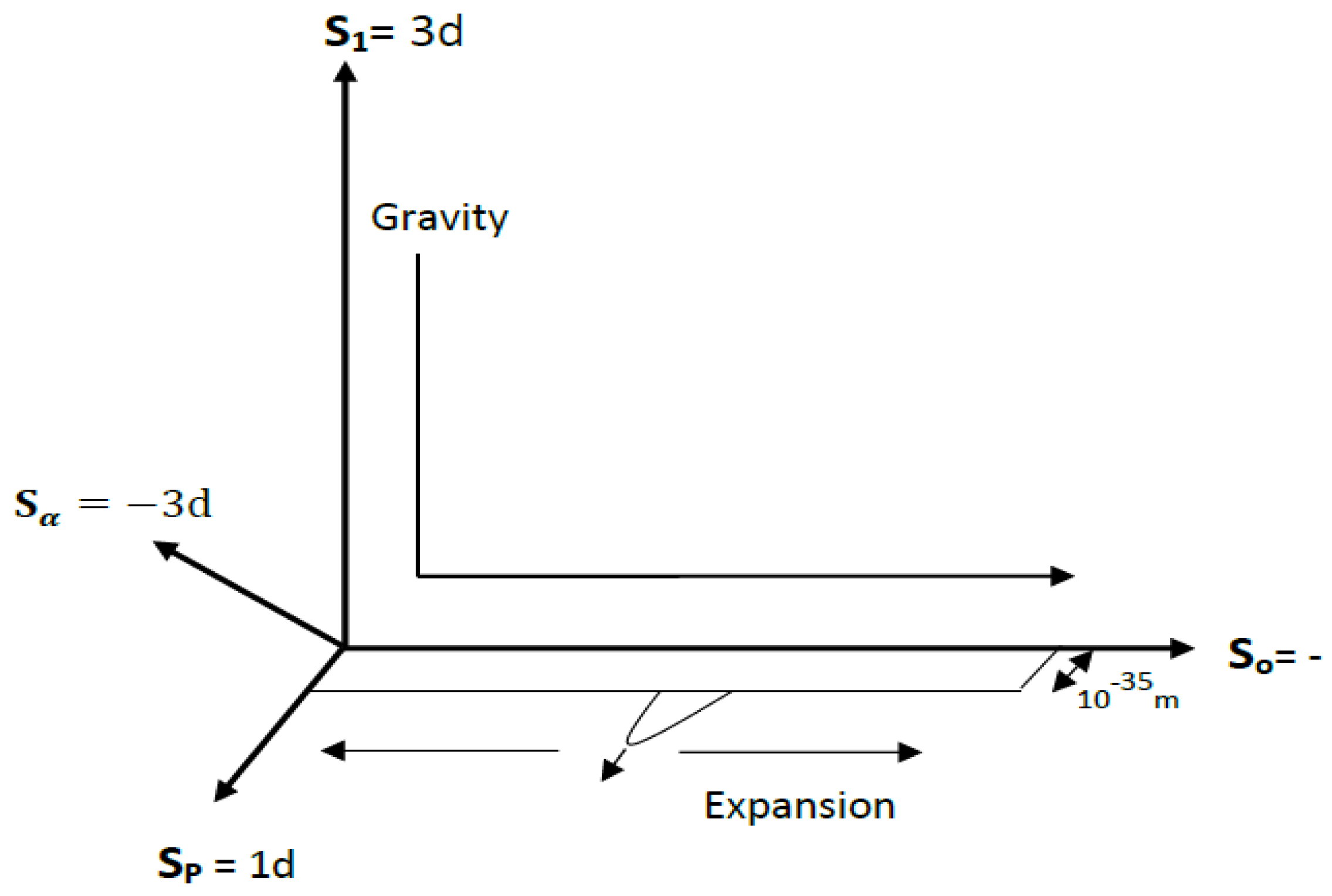

2. Extra Dimensional Symmetry Framework

In this framework, the number of large spatial

dimensions is described by the dimension number

such that,

.

where

corresponds to

which is a time like spatial dimension that is

invisible due to speed constraint discussed in

Section

2.1.

corresponds to which is the visible set of spatial dimensions.

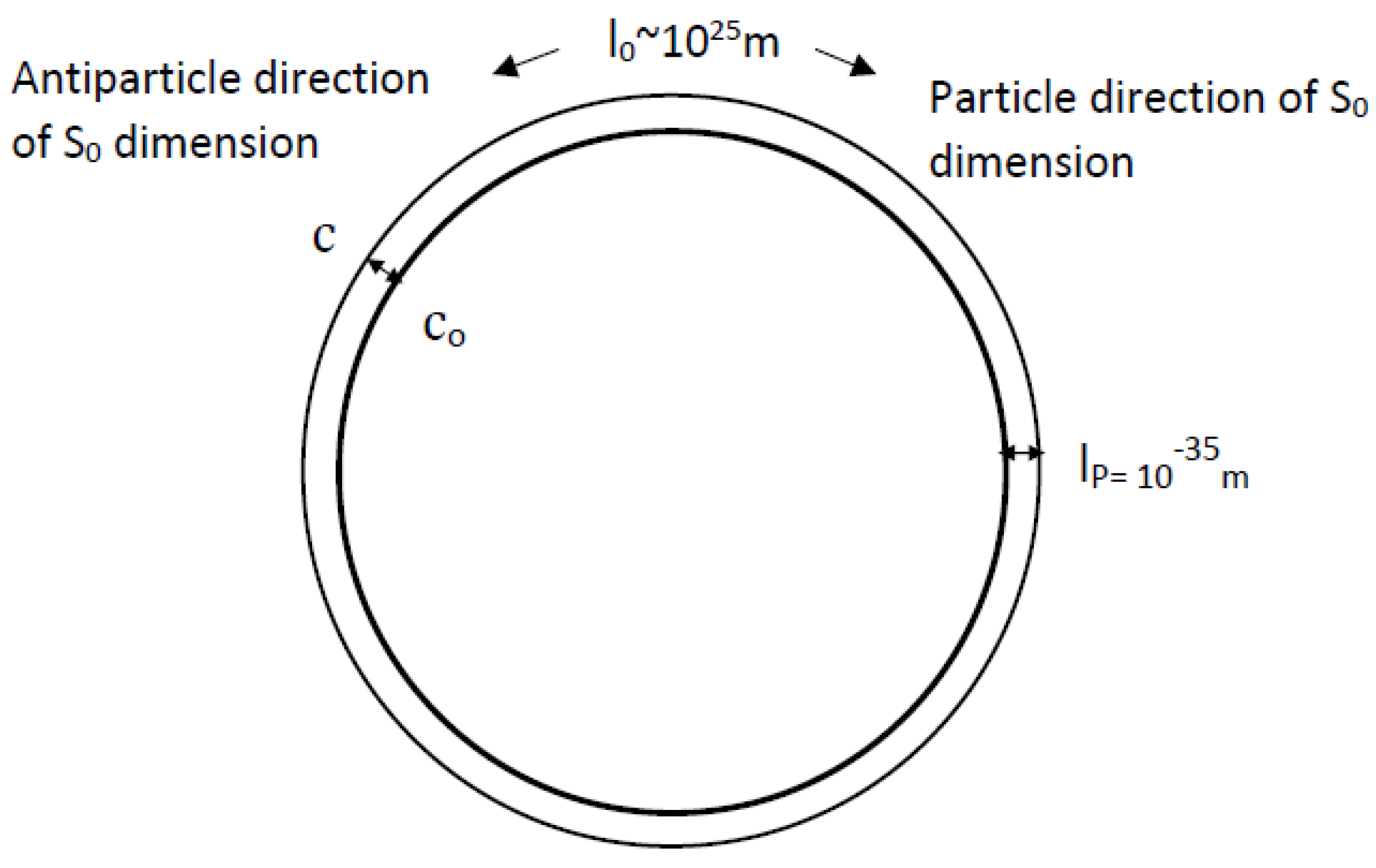

The EDS framework doubles large spatial dimensions

with microscopic dimensional partners with opposite dimension numbers such that

the total dimension number of the universe is zero as illustrated in

Figure 1. While the dimensional partner of S

0,

is a Planck size

dimension, the dimensional partner of S

1

is denoted

. If there is perfect symmetry,

. It is assumed that the large spatial dimensions S

1

and S

0 where inflated in the early universe at the expense of their

dimensional partners

and S

P which contracted to their

microscopic sizes becoming invisible.

In resolving the mysteries of dark energy and dark

matter, this paper focuses on the S0 dimension and its microscopic

dimensional partner SP as well as their interactions with the

visible spatial dimension S1.

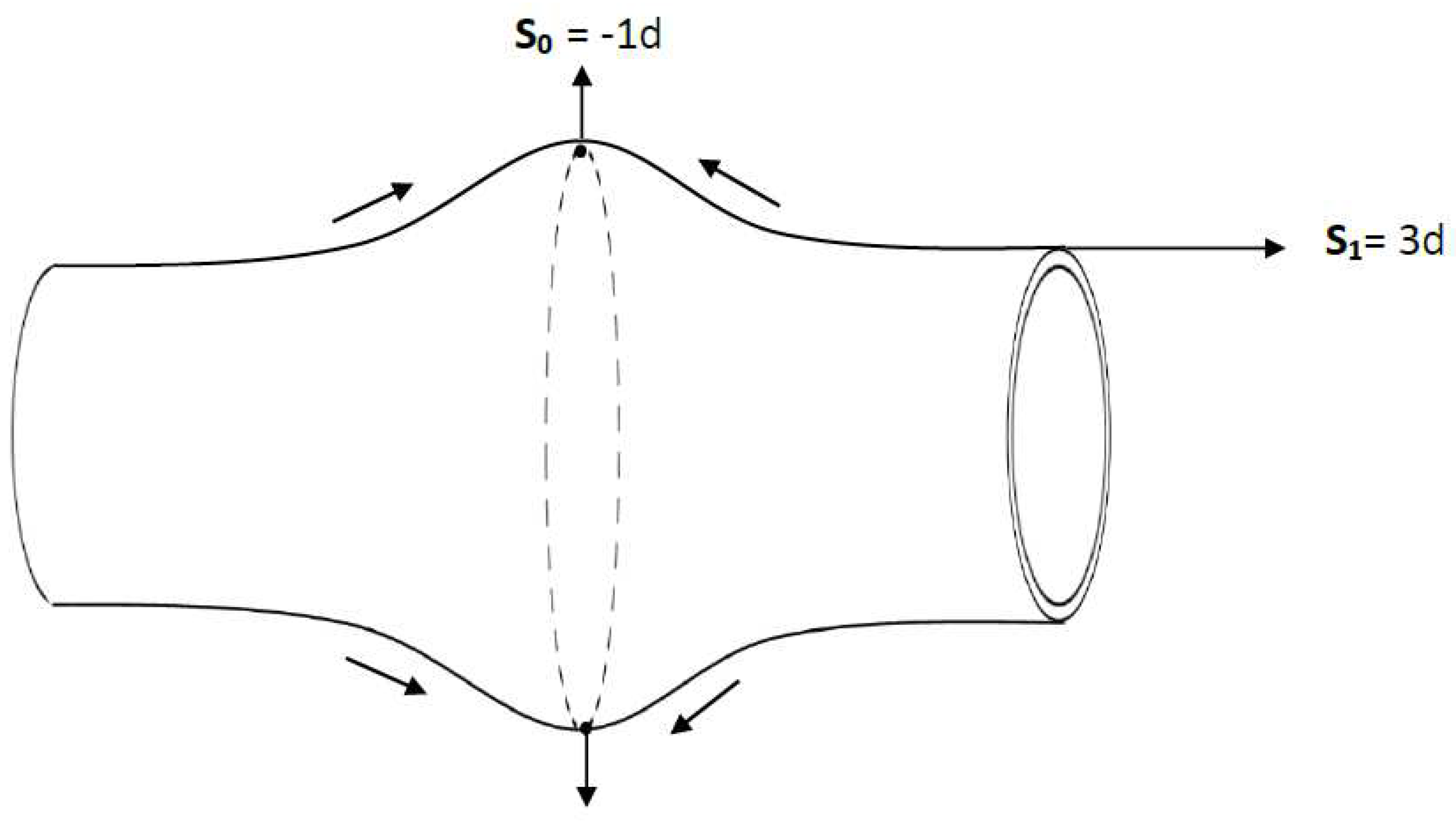

2.1. Speed Constraint and Invisibility of S0

Despite its cosmic size, the S

0

dimension is invisible due to its time like behavior from the speed constraint

illustrated in Equation (2) and

Figure 2.

Consistent with Special Relativity, the speed constraint requires that a

particle’s velocity must always equal the maximum speed limit c in the S

1

– S

0 dimension. Massless particles like photons have zero velocity

component along S

0, while massive particles and antiparticles travel

in opposite directions along S

0. This motion along S

0 is

quantitatively equivalent to the passage of time such that,

where µ is particle velocity along S0,

and ν is particle velocity along visible spatial dimension S1.

When

for massive particles,

and conversely, when

ν , for massless particles,

, to satisfy the speed constraint. This suggests

that time can be an emergent temporal dimension driven by the velocity of a

particle along S

0 dimension. How fast time appears to pass for a

massive particle can be equivalent to the ratio of its S

0 component

of velocity

to the speed limit c as,

where

is the equivalent Lorentz factor for the S

0 dimension. Since

,

2.2. Speed Limit Asymmetry

The asymmetry in speed limits c and c

0 is described by the asymmetry parameter

which is the ratio of the Planck size of S

P to the size of S

0 dimension, illustrated in

Figure 3.

such that,

where

is the size of S

0 in Planck unit. And

where

, is the value of

in flat spacetime. The increase in size

is proportional to the absolute value of the gravitational potential

such that,

where

is a constant. The asymmetry relationship between the two speed limits c and c

0, as shown in

Figure 3 can be expressed as,

2.3. Gravitational State Oscillation

In EDS, Standard Model particles oscillates between the two speed states which are also opposite gravitational on and off states. This is such that for a particle of energy E, with the exception of neutrinos, the state life time

for such particle is,

where

is the reduced Planck constant and

is the Planck energy. The oscillation of neutrinos between the active and the inert phase is regulated by a different mechanism.

The oscillation of Standard Model particles between the two gravitational states and , makes gravity discrete on microscopic spacetime scale. It however appears smooth on macroscopic spacetime scale with an average gravitational constant G.

2.4. Energy Density Constraint

The energy density constraint essentially constrains the total energy density in a given volume of spacetime to always equal the upper limit of the Planck density

. This is only obtainable in the gravitational active state where the speed limit is c while the bare vacuum energy component exists in the inert state with lower speed limit and hence lower Planck density

where

is the vacuum energy density, and

is the total baryonic matter density. The key significance of this, is in the emergence of non zero Λ dark energy in section 4. However, such energy density constraint implies a Planck density limit to the density of black holes like that suggested in [

13], where Planck stars replace black hole singularities.

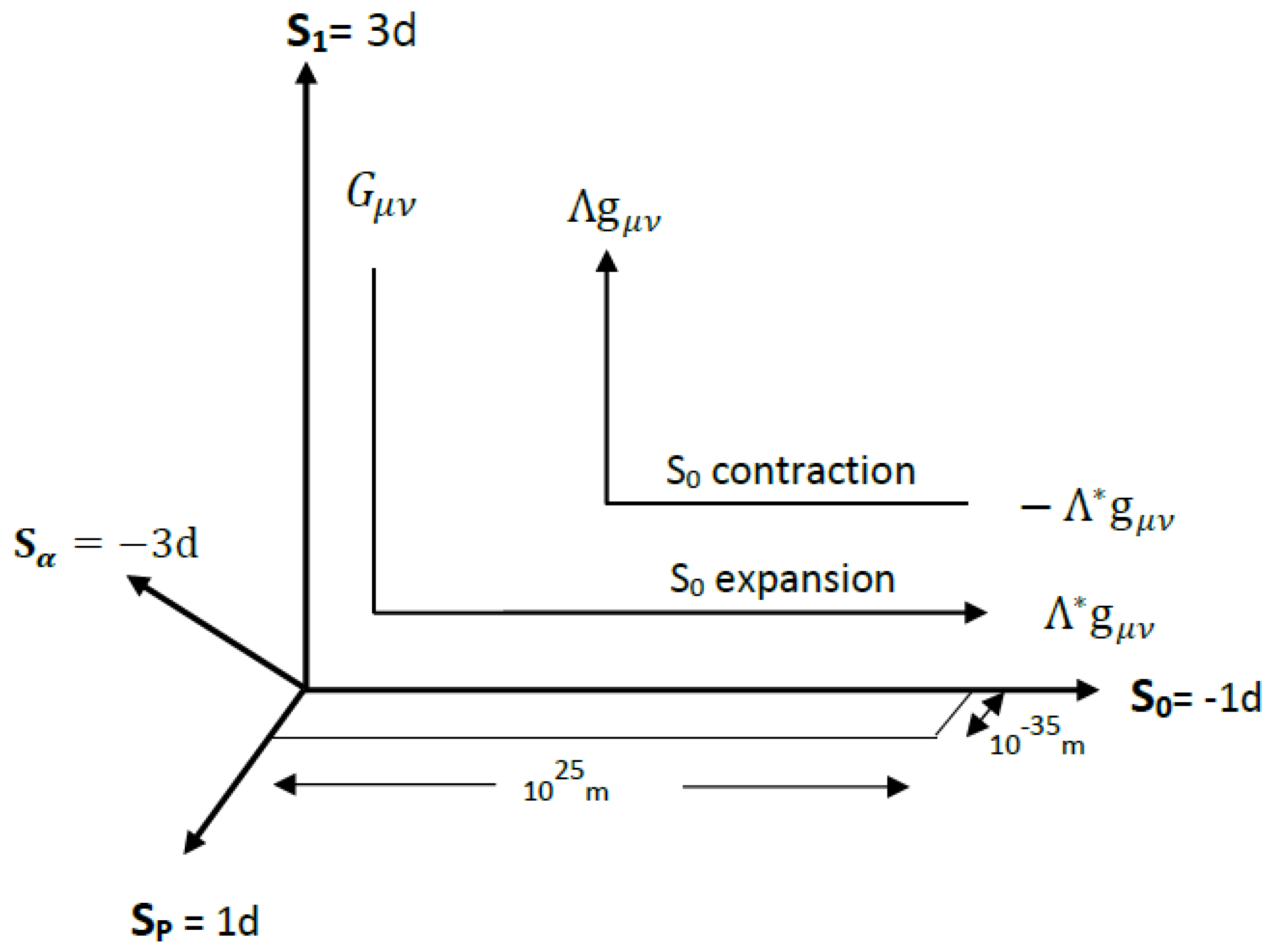

3. General Relativity in S0Dimension

Solution of Einstein’s Field Equation in 1+1 dimensionality is being used as a pedagogical tool [

14] and reveals some interesting properties of the equation in such dimensionality. In this section, the focus is on General Relativity in -1+1 dimension which have some inverted features not seen in 1+1 dimensionality because of the negative dimension number of S

0. The negative dimension number of the S

0 dimension gives it some features such as appearance of positive energy density as negative energy density and the inversion of positive pressure to negative pressure. Eintein’s Field Equation in S

0 can be expressed as

where

is the equivalent Einstein Tensor in S

0 dimension.

is the equivalent cosmological constant and

is the stress energy tensor as seen in S

0 dimension. In -1+1 dimensionality, just as in 1+1, the curvature term

is zero, and Equation (11) becomes

3.1. Features of General Relativity in S0Dimension

The negative one dimensionality of the S0 dimension from Equation (1), when applied in the context of General Relativity, confers on it some unique features such as:

- i.

Positive energy density in S1 is equivalent to negative energy density everywhere in S0.

An energy density associated with a given Planck volume of 3d space S

1 appears as an equivalent negative energy density everywhere along S

0 dimension associated with it as a positive cosmological constant as illustrated in

Figure 4.

- ii.

Positive pressure in S1 is equivalent to negative pressure in S0

Any form of positive pressure in S1 appears as negative pressure in S0 for the same reason of negative dimensionality. The result is a positive cosmological constant expansion of S0.

- iii.

Negative pressure in S1 is equivalent to a positive pressure in S0

The same negative dimensionality causes the inversion of negative pressure in S

1 appearing as positive pressure in S

0 driving its negative cosmological constant contraction. The result is that the curvature of S

1 (

) is equivalent to the cosmological constant expansion of S

0 as illustrated in

Figure 5, such that,

and a positive cosmological constant term (

) in S

1 is equivalent to a negative cosmological constant term (

) in S

0 such that,

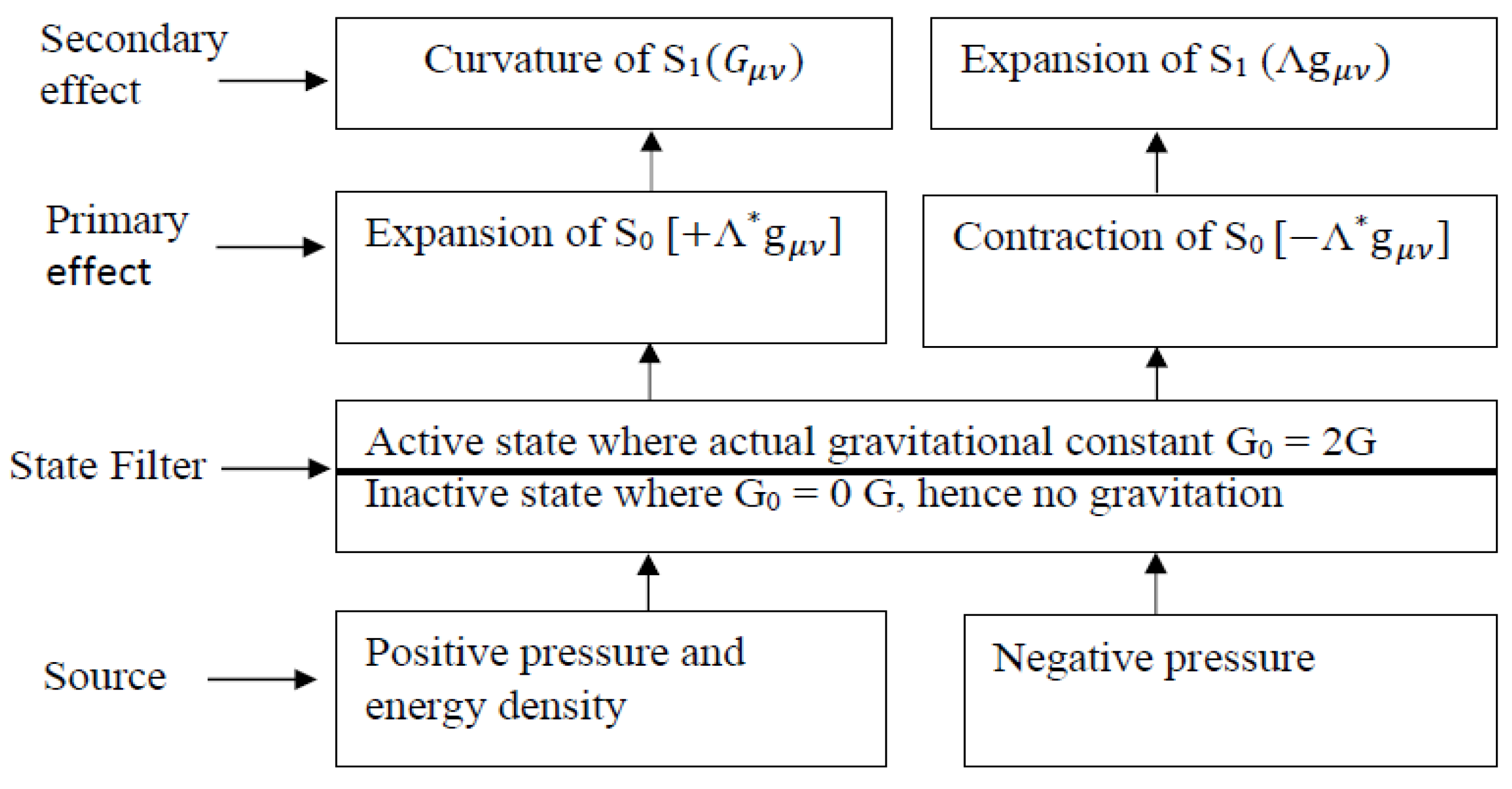

3.2. Gravitational Chain of Causality

The inversion of gravitation discussed in the previous section suggests that at a more fundamental level, gravity is the expansion or contraction of S

0 dimension. This then manifests in an inverted form as curvature or expansion of S

1 dimension as illustrated in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The existence of gravitational on and off states acts as a filter in this gravitational chain of causality enabling real particles to gravitate while virtual particles remain inert as illustrated in

Figure 6.

The existence of the bare vacuum energy component in the gravitationally inert state ensures that it does not gravitate. This partly solves the cosmological constant problem. The second part of the problem about the nonzero value is addressed in the next section.

4. Emergence of Nonzero Cosmological Constant

The asymmetry in speed limit described in Equation (8) between the two gravitational states also reflects in the values of their Planck densities such that

where

is the lower Planck density in C

0 state and

is the Planck density in the C state.

The existence of the bare vacuum energy component

in the lower C

0 state implies that

which is less than the Planck density and the energy density constraint requires that the total vacuum energy density should be equal to the Planck density in the absence of matter.

Since the gravitationally inert lower speed state lacks the capacity to contain all the vacuum energy components, a small component spills into the gravitationally active state as dark energy

as illustrated in

Figure 7, such that,

in the gravitationally active state C to satisfy the energy density constraint so that the total vacuum energy density equals the Planck density . The lower Planck density is associated with speed state C0.

Since

is suppressed with the expansion of S

0 in the gravitational well of massive objects (Equation (6) and

Figure 4), the density of this form of dark energy varies spatially according to this suppression by gravitational potential wells. The deeper the gravitational well the more the suppression. And substituting the value of

from Equation (5),

where

is the size of S

0 dimension in Planck unit, which increases with the absolute value of the gravitational potential

according to Equation (7).

5. Gravitational Wave Reheating (GWR) Prediction

The propagation of gravitational waves along the visible 3d space S

1 should also vibrate any extra spatial dimension such as the S

P and S

0 dimensions. The stretching of S

P dimension during such vibration should cause the creation of real photons out of vacuum energy. This is the Gravitational Wave Reheating (GWR) mechanism of EDS. However as illustrated in

Figure 8, the expansion of S

0 dimension in gravitational potential wells suppresses the possible stretching of S

P dimension resulting in a threshold value of strain

below which reheating cannot occur.

This is such that for reheating to occur, the gravitational wave strain

must be greater than the gravitational strain

of S

0 expansion as

and

where

is the increase in the size of S

0 dimension and it is proportional to the absolute value of the gravitational potential

from Equation (7).

is the size of S

0 in flat spacetime.

hardens the S

P dimension against gravitational wave oscillation.

5.1. Energy Scale of Reheat Photons

The maximum energy

of the reheat photons that can be emitted in the resulting spectrum can be described by

where

is the Planck energy and

is the effective stretching strain of the resulting S

P oscillation once the threshold gravitational wave strain is exceeded such that

.

5.2. Magnetic Softening of the SP Dimension

Magnetic fields produce negative pressure that can flatten curvature and even dampen gravitational waves [

15]. Within the EDS framework, the gravitational strain of expansion (

) of the S

0 dimension is a measure of spatial curvature. Therefore, the flattening of spacetime curvature softens the S

P dimension which becomes more sensitive to gravitational wave oscillation. In essence, a strong magnetic field like that obtainable around magnetars, softens the S

P dimension by lowering the threshold strain required for reheating to occur with incident gravitational waves.

From energy conservation perspective, the energy lost by gravitational waves passing through a strongly magnetized region has to be released in some form and GWR provides the mechanism for converting the gravitational wave energy into electromagnetic one. It is expected that the brief burst of electromagnetic waves radiated while the gravitational waves passes through a strongly magnetized region such as magnetars, should be in the form of radio waves.

6. Dark Matter from Vacuum Energy

The bare vacuum energy component should always be gravitationally inert with its existence in the

state where the gravitational field is effectively switched off. However, in this framework, neutrinos affects their background in the inert state such that

. Within such background in the inert state, neutrinos provide some gravitational illumination described by Equation (22) that enables virtual particles to gravitate with positive pressure appearing as dark matter.

where

is the neutrino induced gravitational constant in the inert state.

is the asymmetry parameter involved in the emergence of dark energy.

is the flavour parameter. It varies with neutrino flavour such that

.

is a dimensionless phase parameter that varies between zero and one (

), with zero being a ground phase where it always gets stuck until it experiences a disturbance of the microscopic dimensions such as reheating described in the previous section. It remains in this active phase for a life time

and falls back to the

phase.

is a dimesionless parameter that varies with neutrino kinetic energy.

and it is described by,

where

is the neutrino kinetic energy and

is the Planck energy. Substituting

and

from Equation (5) and Equation (23), Equation (22) becomes,

where

is the size of the S

0 dimension (in Planck unit) which increases with the absolute value of the gravitational potential

, hence the suppression of dark matter effect of neutrinos in deep gravitational potential wells.

It is assumed that the value of the gravitational constant in both gravitationally active and inert state, is constrained such that,

where

and

are the gravitational constants in the active and the inert states respectively.

While hot dark matter is the form of dark matter that can be produced by relativistic neutrinos, cosmic neutrinos are nonrelativistic. Such nonrelativistic cosmic neutrino substrates should be further slowed down by the Higgs like drag from its self induced gravitational interaction with virtual particles within its background. This enhances the clustering of cosmic neutrino substrates and the gravitating virtual particles in their background appear as cold dark matter.

The gravitational potential suppression of

enables this substrate dependent form of dark matter to have hybrid behaviour by mimicking modified gravity form of dark matter such as Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) while also exhibiting some particle behavior of its neutrino substrates like the gravitational polarization of vacuum energy approach [

10] and superfluid dark matter described in [

16].

6.1. Categories of Neutrino Substrate Dependent Dark Matter

Heavy and light dark matter are two categories of neutrino substrate dependent dark matter that exists within the EDS frame work depending on the neutrino energy scale and phase parameter. Equation (22) consists of a rest term and a kinetic term . The kinetic term can be active or inert depending on the phase parameter which varies between one and zero where it freezes. can be unfrozen from its zero value, activating the kinetic term, gravitational disturbances such as sudden change in negative pressure above a threshold and falls back to its frozen phase within a life time . Such gravitational disturbances can also trigger reheating discussed in section 5.

- i.

Heavy dark matter

From Equation (22), an Ultra High Energy neutrino with a kinetic energy of 1015 eV and a phase parameter , will have an active kinetic term. It can induce a gravitational constant close to 10-13 G in the gravitationally inert state where the bare vacuum energy exists. With the gravitation of vacuum energy of the order the Planck density with such value of G within the neutrino background, it can manifest as detectable heavy dark matter. As the high energy neutrino substrate falls back to the frozen phase with the kinetic term becomes inactive, making it become light form of dark matter. A micro-resolution digital scale should have the sensitivity to detect the gravitational effect of such heavy dark matter while it is still active.

- ii.

Light dark matter

Neutrinos in the state, particularly cosmic neutrinos can induce close to 10-120 G in the gravitationally inert state, resulting in light and cold dark matter, clustered within and around galaxies. Such light form of dark matter which dominates the total dark matter density in this framework, can only be detected through the CMB, gravitational lensing and the dynamics of wide stellar binaries, galactic and extra galactic structures.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

EDS provides an elegant framework for the resolution of the cosmological constant problem of dark energy and the nature of dark matter. In doing so it provides deeper insights into the dimensional structure of spacetime and chain of causality involved in gravitation. Specifically, it places the bare vacuum energy component in a state where the gravitational field is switched off with actual gravitational constant G0 = 0G, while real standard model particles, oscillate between this gravitationally inert state and the active state.

Due to an energy density constraint and a speed limit asymmetry that limits the capacity of the inert state to contain the entire vacuum energy component, a small component spills into the active state as dark energy. The asymmetry parameter is the ratio of the size of the spatial equivalent of time (S0 dimension) and its microscopic partner SP.

The illuminating effect of neutrino substrates particularly cosmic neutrinos, induces non zero gravitational constant in the inert state, providing gravitation for virtual particles which appears as dark matter. This neutrino substrate dependent form of dark matter exhibits hybrid behaviour of particle dark matter and modified gravity form of dark matter like the gravitational polarization of vacuum energy approach [

10] and superfluid dark matter [

16]. The heavy form of dark matter that can be activated by the gravitational disturbance of the microscopic dimension S

P, provides an opportunity for direct detection of such form of dark matter while it is active.

The reheating prediction in which gravitational waves produce electromagnetic secondary with negative pressure from strong magnetic fields of magnetars and dark energy might be the sources of Fast Radio Bursts [

17] and Excess Radio Background [

18].

Expected results from the trio of the JWST, Euclid and upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Telescope and Vera Rubin Observatory, are expected to provide precision measurements of dark energy density as well as the dynamics of dark matter. Such precision measurements should glean out the predicted suppression of dark energy density in the deep gravitational potential wells of baryonic matter like it apparently does to dark matter.

There are a number of potential insights that are beyond the scope of this paper. For instance it is possible that the fine structure constant just like

, is simply the ratio of the Planck scale to the size of the

dimension. It is also possible that the rest term in Equation (24), might be the source of neutrino mass. These possibilities as well as others like baryon asymmetry from net spin with respect to the S

0 dimension (

Figure 3), shall be investigated in future work.

In conclusion, the EDS framework offers new physics explanations for dark energy and dark matter as different manifestations of vacuum energy that can be tested and provides potential insights into the dimensional structure of spacetime and gravity.

Author Contributions

Kabir Adinoyi Umar: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Resources. Benjamin Gbenga Ayatunji: Supervision.

Data availability: No data was used for the research described in the article

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Benjamin G. Ayatunji for his criticisms, encouragement and mentorship and S. X. K. Howusu for his inspiring advice and initial motivation for this work. This work was funded by the author.

Declaration of competing interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gilliland, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. Astron. J. 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade P. A., R. et al., Planck 2013 results. XVI. 2013; arXiv:1303.5076[astro-ph.CO]. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. M. , The cosmological constant, Living Rev. Rel. a: 4:1, (2001), arXiv, 2001; :1. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, S. et al., de Sitter vacua in string theory, Phys. Rev. D68 (2003) 046005, arXiv:hep-th/0301240.

- Banks, T.; Dine, M.; Motl, L. On anthropic solutions of the cosmological constant problem. J. High Energy Phys. 2001, 2001, 031–031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamid, N. , A small cosmological constant from a large extra dimension, Phys. Lett. B480 (2000) 193-199, arXiv:hep-th/000197.

- Copeland, E. J. et al., Dynamics of dark energy, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D15 (2006) 1753-1936, arXiv:hep-th/0603057.

- Oks, E. Brief review of recent advances in understanding dark matter and dark energy. New Astron. Rev. 2021, 93, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, K. et al. Dark matter, dark energy and alternate models: a review, Advances in Space Research, 60, (2017) 166-186, arXiv: 1704.06155[physics.gen-ph]. 2017, arXiv:1704.06155[physics60. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukovic D., S. Quantum vacuum and dark matter, Astrophysics and Space Science 337 (2012)9-14.

- Borchert M., J. , Devlin J. A., Ulmer S., et al. A 16 parts per trillion measurement of the antiproton to proton charge-mass ratio, Nature 601 (2022) 53-57.

- Anderson, E.K.; Baker, C.J.; Bertsche, W.; Bhatt, N.M.; Bonomi, G.; Capra, A.; Carli, I.; Cesar, C.L.; Charlton, M.; Christensen, A.; et al. Observation of the effect of gravity on the motion of antimatter. Nature 2023, 621, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovelli, C. , Vidoto, F., Planck Stars, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D23 (2014) 1442026, arXiv:1401.6562.

- Boozer, A.D. General relativity in (1 + 1) dimensions. Eur. J. Phys. 2008, 29, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagas, C.G. Magnetic Tension and the Geometry of the Universe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 5421–5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossenfelder, S.; Mistele, T. The Milky Way’s rotation curve with superfluid dark matter. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020, 498, 3484–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. The physics of fast radio bursts. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 95, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialkov, A.; Barkana, R. Signature of excess radio background in the 21-cm global signal and power spectrum. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 486, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).