Submitted:

08 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Survey Participants

3.2. Participants' perspectives on the safety of Greek-produced plant foods in terms of pesticide residues in comparison to those of other EU member states.

3.3. The variables predicting the participants' attitudes towards the safety of Greek-produced plant foods research question

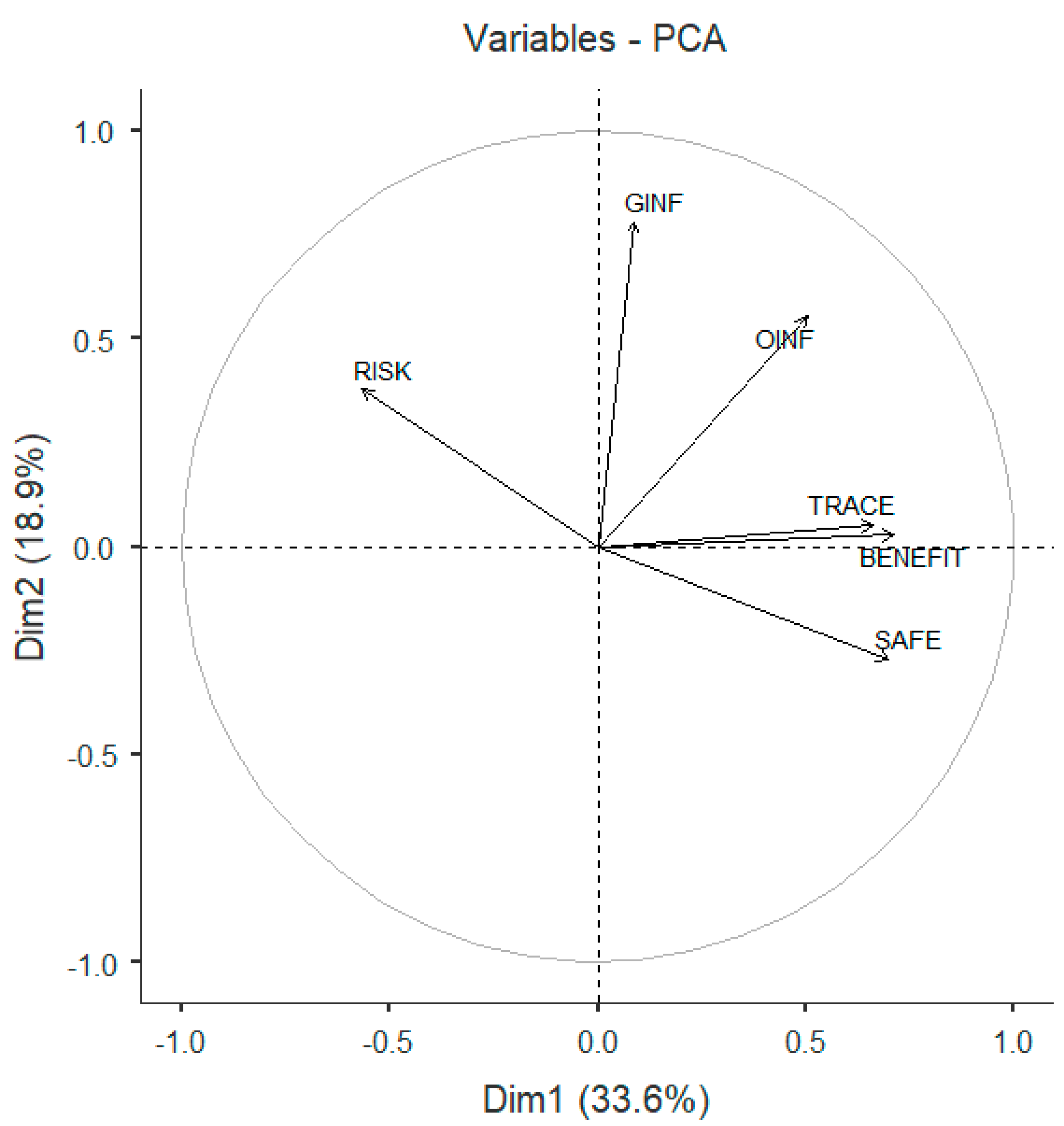

3.3.1. Principal components underlying the participants' attitudes

3.3.2 Predictive variables of participants' perceptions – Logistic regression model

3.4. Latent class analysis of the respondents

3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographic variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 896 | 48.50% |

| Male | 950 | 51.50% | |

| Age | 18 – 24 | 220 | 11.90% |

| 25 – 34 | 195 | 10.60% | |

| 35 – 44 | 404 | 21.90% | |

| 45 – 54 | 669 | 36.20% | |

| 55 – 64 | 304 | 16.50% | |

| ≥ 65 | 54 | 2.90% | |

| Educational background | Less than high school | 31 | 1.70% |

| High school – Technical education | 397 | 21.50% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 727 | 39.40% | |

| Master's degree | 565 | 30.60% | |

| Doctoral degree | 126 | 6.80% | |

| Residential geographical area | Northern Greece | 540 | 29.30% |

| Central Greece | 473 | 26.60% | |

| Southern Greece | 833 | 45.10% | |

| Population of place of residence | Less than 10,000 inhabitants (rural) | 468 | 25.40% |

| More than 10,000 inhabitants (urban) | 1378 | 74.60% | |

| Underage children in the family | No | 1027 | 55.60% |

| Yes | 819 | 44.40% | |

| Plenty of spare time | Νο | 735 | 39.80% |

| Yes | 1111 | 60.20% | |

| Smoking habits | Νο | 1404 | 76.10% |

| Yes | 442 | 23.90% | |

| Vegetarian by choice | Νο | 1722 | 93.30% |

| Yes | 124 | 6.70% | |

| Physical activity habits | Never | 243 | 13.20% |

| Occasionally | 1207 | 65.40% | |

| Systematically | 396 | 21.40% | |

| Professional or amateur pesticide users | Νο | 1058 | 57.30% |

| Yes | 788 | 42.70% | |

| Occupation | Civil servants | 814 | 44.10% |

| Private employees | 344 | 18.60% | |

| Self-employed | 224 | 12.10% | |

| Farmers | 98 | 5.30% | |

| Unemployed | 71 | 3.90% | |

| University students | 215 | 11.70% | |

| Retired | 80 | 4.30% |

| Original variables (5-point Likert scale statements) | Median (1) | IQR (2) | Principal components | Uniqueness (3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OINF | BENEFIT | GINF | TRACE | RISK | SAFE | ||||

| Official information sources | Perceived pesticides' benefits | General information sources | Confidence in traceability | Perceived pesticides' risk | Perceived plant-food safety | ||||

| Official Websites as source for pesticide information | 3 | 2 | 0.918 | 0.185 | |||||

| Newsletters from public institutions '' | 3 | 2 | 0.866 | 0.259 | |||||

| Scientific periodicals '' | 3 | 2 | 0.853 | 0.270 | |||||

| I receive information on pesticides from Agronomists | 4 | 3 | 0.712 | 0.428 | |||||

| Pesticides contribute to national income growth | 4 | 1 | 0.836 | 0.383 | |||||

| Pesticides help increase food production | 4 | 1 | 0.797 | 0.441 | |||||

| The use of agrochemicals is an unavoidable fact | 4 | 2 | 0.719 | 0.470 | |||||

| The correct use of pesticides safeguards the user | 4 | 2 | 0.697 | 0.418 | |||||

| The proper use of pesticides protects the consumer | 4 | 2 | 0.652 | 0.411 | |||||

| My information sources about pesticides are TV/Radio | 2 | 2 | 0.791 | 0.358 | |||||

| '' Electronic Press | 3 | 2 | 0.789 | 0.282 | |||||

| '' Press | 2 | 2 | 0.743 | 0.373 | |||||

| '' Social Media | 2 | 2 | 0.716 | 0.483 | |||||

| Labelling (traceability) reassures me | 4 | 1 | 0.865 | 0.273 | |||||

| Safety of certified food products | 4 | 1 | 0.843 | 0.303 | |||||

| Products from Integrated Crop Management are safe | 4 | 1 | 0.819 | 0.310 | |||||

| I feel that my health has been at risk | 3 | 1 | 0.820 | 0.288 | |||||

| I feel uncertain about the health of my own people | 4 | 2 | 0.793 | 0.424 | |||||

| Pesticide residues in food make me concerned about my safety | 5 | 1 | 0.787 | 0.347 | |||||

| Food of plant origin is generally safe to consume | 4 | 2 | 0.893 | 0.295 | |||||

| The consumption of fruit and vegetables does not generally pose a risk to the consumer | 3 | 2 | 0.733 | 0.345 | |||||

| Plant-based foods are tested for pesticide residues | 3 | 2 | 0.636 | 0.450 | |||||

| Sum of the squared loadings | 2.970 | 2.795 | 2.390 | 2.245 | 1.982 | 1.823 | |||

| Scale reliability (McDonald's ω) | 0.865 | 0.796 | 0.774 | 0.795 | 0.720 | 0.698 | |||

| Explained variance % | 13.502 | 12.706 | 10.863 | 10.205 | 9.008 | 8.288 | |||

| Cumulative variance % | 13.502 | 26.208 | 37.071 | 47.275 | 56.283 | 64.571 | |||

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | X2 = 14,294.113; df = 231; p < 0.001 | ||||||||

| KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy test | 0.829 | ||||||||

|

(1): Median of the distribution of participants' answers to the 5-point Likert scale questions (1 = never to 5 = usually, or 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, whichever applies). (2): Interquartile range (3): Proportion of variance that is ''unique'' to the variable and not explained by the PCs. Uniqueness equals 1-communality. The lower the uniqueness, the higher the relevance of the variable in the PC model. Note: ''promax'' rotation was used, variable loadings > 0.6 and uniqueness < 0.5 were selected. | |||||||||

| Model coefficients – Dependent variable: Plant-food produced in Greece is as safe as in other EU member-States in term of pesticide residues | |||||||||

| Wald test | 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

| Predictor | Estimate, b | Standard error | z | Statistic | df | p | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | −0,637 | 0,145 | −4,399 | 19,353 | 1 | <0,001 | 0,529 | 0,398 | 0,702 |

| SAFE (Perceived plant-food safety) | 0,863 | 0,066 | 12,991 | 168,755 | 1 | <0,001 | 2,369 | 2,080 | 2,698 |

| Higher education | 0,553 | 0,134 | 4,129 | 17,045 | 1 | <0,001 | 1,738 | 1,337 | 2,260 |

| Age group ≥45 years old | 0,423 | 0,112 | 3,773 | 14,233 | 1 | <0,001 | 1,527 | 1,226 | 1,903 |

| OINF (Official information sources) | 0,408 | 0,063 | 6,468 | 41,836 | 1 | <0,001 | 1,504 | 1,329 | 1,701 |

| Male gender | 0,308 | 0,116 | 2,657 | 7,058 | 1 | 0,010 | 1,361 | 1,084 | 1,708 |

| TRACE (Confidence in traceability) | 0,231 | 0,062 | 3,702 | 13,707 | 1 | <0,001 | 1,259 | 1,115 | 1,423 |

| BENEFIT (Perceived pesticides benefits) | 0,228 | 0,065 | 3,524 | 12,420 | 1 | <0,001 | 1,256 | 1,106 | 1,426 |

| RISK (Perceived pesticides risk) | −0,123 | 0,061 | −2,006 | 4,024 | 1 | 0,045 | 0,884 | 0,784 | 0,997 |

| Pesticides user status | −0,327 | 0,137 | −2,395 | 5,736 | 1 | 0,020 | 0,721 | 0,551 | 0,942 |

| Predictive measures: AUC = 0.790; Sensitivity = 0.709; Specificity = 0.736 | |||||||||

| Note: Estimates represent the log odds of "Plant-food produced in Greece is as safe as in other EU member-States = 1" vs. "Plant-food produced in Greece is as safe as in other EU member-States = 0" | |||||||||

References

- Pawlak, K.; Kołodziejczak, M. The Role of Agriculture in Ensuring Food Security in Developing Countries: Considerations in the Context of the Problem of Sustainable Food Production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO,2023. Strategic Priorities for Food Safety FAO within the FAO Strategic Framework 2022–2031, Rome.

- Damalas, C. A.; Eleftherohorinos, I. G. Pesticide Exposure, Safety Issues, and Risk Assessment Indicators. IJERPH 2011, 8, 1402–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F. P. Agriculture, Pesticides, Food Security and Food Safety. Environmental Science & Policy 2006, 9, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Dobson, H. The Benefits of Pesticides to Mankind and the Environment. Crop Protection 2007, 26, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zeiss, M. R.; Geng, S. Agricultural Pesticide Use and Food Safety: California’s Model. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2015, 14, 2340–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, J.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Bon, H.; Huat, J.; Parrot, L.; Sinzogan, A.; Martin, T.; Malézieux, E.; Vayssières, J.-F. Pesticide Risks from Fruit and Vegetable Pest Management by Small Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Ficke, A.; Aubertot, J.-N.; Hollier, C. Crop Losses Due to Diseases and Their Implications for Global Food Production Losses and Food Security. Food Sec. 2012, 4, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S. J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The Global Burden of Pathogens and Pests on Major Food Crops. Nat Ecol Evol 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kooner, R.; Arora, R. Insect pests and crop losses. In Breeding Insect Resistant Crops for Sustainable Agriculture; Arora, R., Sandhu, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 45–66. ISBN 978-981-10-6055-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kabir, E.; Jahan, S. A. Exposure to Pesticides and the Associated Human Health Effects. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 575, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magkos, F.; Arvaniti, F.; Zampelas, A. Organic Food: Buying More Safety or Just Peace of Mind? A Critical Review of the Literature. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2006, 46, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curl, C. L.; Beresford, S. A. A.; Fenske, R. A.; Fitzpatrick, A. L.; Lu, C.; Nettleton, J. A.; Kaufman, J. D. Estimating Pesticide Exposure from Dietary Intake and Organic Food Choices: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Health Perspect 2015, 123, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tago, D.; Andersson, H.; Treich, N. Pesticides and health: A review of evidence on health effects, valuation of risks, and benefit-cost analysis. In Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research; Blomquist, G.C., Bolin, K., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 24, pp. 203–295. ISBN 978-1-78441-029-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi, C.; Morasso, G. Genotoxicity of Pesticides. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2000, 11, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P.; Maipas, S.; Kotampasi, C.; Stamatis, P.; Hens, L. Chemical Pesticides and Human Health: The Urgent Need for a New Concept in Agriculture. Front. Public Health 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L. G. The Neurotoxicity of Organochlorine and Pyrethroid Pesticides. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier, 2015; Vol. 131, pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Eriksson, P.; Fredriksson, A.; Buratovic, S.; Viberg, H. Developmental Neurotoxic Effects of Two Pesticides: Behavior and Neuroprotein Studies on Endosulfan and Cypermethrin. Toxicology 2015, 335, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Chen, C.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qian, Y. Combined Cytotoxic Effects of Pesticide Mixtures Present in the Chinese Diet on Human Hepatocarcinoma Cell Line. Chemosphere 2016, 159, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, M.; Chen, C.; Yang, X.; Qian, Y. Three Widely Used Pesticides and Their Mixtures Induced Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis through the ROS-Related Caspase Pathway in HepG2 Cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2021, 152, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillot, V.; Takakura, N.; Hegarat, L. L.; Fessard, V.; Audebert, M.; Cravedi, J.-P. Genotoxicity of Pesticide Mixtures Present in the Diet of the French Population. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2012, 53, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matich, E. K.; Laryea, J. A.; Seely, K. A.; Stahr, S.; Su, L. J.; Hsu, P.-C. Association between Pesticide Exposure and Colorectal Cancer Risk and Incidence: A Systematic Review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 219, 112327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirdefeldt, K.; Adami, H.-O.; Cole, P.; Trichopoulos, D.; Mandel, J. Epidemiology and Etiology of Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of the Evidence. Eur J Epidemiol 2011, 26, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curl, C. L.; Fenske, R. A.; Elgethun, K. Organophosphorus Pesticide Exposure of Urban and Suburban Preschool Children with Organic and Conventional Diets. Environ Health Perspect 2003, 111, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Barr, D. B.; Pearson, M. A.; Waller, L. A. Dietary Intake and Its Contribution to Longitudinal Organophosphorus Pesticide Exposure in Urban/Suburban Children. Environ Health Perspect 2008, 116, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, G.; Bao, Y. Revisiting Pesticide Exposure and Children’s Health: Focus on China. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 472, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozowicka, B. Health Risk for Children and Adults Consuming Apples with Pesticide Residue. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 502, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, M.; Zeng, S.; Gao, J. Urinary Neonicotinoid Concentrations and Pubertal Development in Chinese Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environment International 2022, 163, 107186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortenkamp, A. Ten Years of Mixing Cocktails: A Review of Combination Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Environ Health Perspect 2007, 115 (Suppl. 1), 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laetz, C. A.; Baldwin, D. H.; Collier, T. K.; Hebert, V.; Stark, J. D.; Scholz, N. L. The Synergistic Toxicity of Pesticide Mixtures: Implications for Risk Assessment and the Conservation of Endangered Pacific Salmon. Environ Health Perspect 2009, 117, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laetz, C. A.; Baldwin, D. H.; Hebert, V.; Stark, J. D.; Scholz, N. L. Interactive Neurobehavioral Toxicity of Diazinon, Malathion, and Ethoprop to Juvenile Coho Salmon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2925–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laetz, C. A.; Baldwin, D. H.; Hebert, V. R.; Stark, J. D.; Scholz, N. L. Elevated Temperatures Increase the Toxicity of Pesticide Mixtures to Juvenile Coho Salmon. Aquatic Toxicology 2014, 146, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzati, V.; Briand, O.; Guillou, H.; Gamet-Payrastre, L. Effects of Pesticide Mixtures in Human and Animal Models: An Update of the Recent Literature. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2016, 254, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobis, A. R.; Ossendorp, B. C.; Banasiak, U.; Hamey, P. Y.; Sebestyen, I.; Moretto, A. Cumulative Risk Assessment of Pesticide Residues in Food. Toxicology Letters 2008, 180, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobis, A.; Budinsky, R.; Collie, S.; Crofton, K.; Embry, M.; Felter, S.; Hertzberg, R.; Kopp, D.; Mihlan, G.; Mumtaz, M.; Price, P.; Solomon, K.; Teuschler, L.; Yang, R.; Zaleski, R. Critical Analysis of Literature on Low-Dose Synergy for Use in Screening Chemical Mixtures for Risk Assessment. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2011, 41, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, A. F.; Gil, F.; Tsatsakis, A. M. Biomarkers of Chemical Mixture Toxicity. In Biomarkers in Toxicology; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. F.; Gil, F.; Lacasaña, M. Toxicological Interactions of Pesticide Mixtures: An Update. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91, 3211–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Carrasco Cabrera, L. ; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2021 European Union Report on Pesticide Residues in Food. EFS2 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Craig, P. S.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hernández-Jerez, A. F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Kneuer, C.; Ossendorp, B.; Pedersen, R.; Wolterink, G.; Mohimont, L. Cumulative Dietary Risk Characterisation of Pesticides That Have Acute Effects on the Nervous System. EFS2 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Craig, P. S.; Dujardin, B.; Hart, A.; Hernandez-Jerez, A. F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Kneuer, C.; Ossendorp, B.; Pedersen, R.; Wolterink, G.; Mohimont, L. Cumulative Dietary Risk Characterisation of Pesticides That Have Chronic Effects on the Thyroid. EFS2 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Dujardin, B. Comparison of Cumulative Dietary Exposure to Pesticide Residues for the Reference Periods 2014–2016 and 2016–2018. EFS2 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Food Safety in the EU: Report; Special Eurobarometer – March 2022. Publications Office: LU, 2022; https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-09/EB97.2-food-safetyin- the-EU_report.pdf (accessed on 10-08-2023). [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, R.; Johnston, J.; Tucker, K.; DeSesso, J. M.; Keen, C. L. Estimation of Cancer Risks and Benefits Associated with a Potential Increased Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012, 50, 4421–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcke, M.; Bourgault, M.-H.; Rochette, L.; Normandin, L.; Samuel, O.; Belleville, D.; Blanchet, C.; Phaneuf, D. Human Health Risk Assessment on the Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables Containing Residual Pesticides: A Cancer and Non-Cancer Risk/Benefit Perspective. Environment International 2017, 108, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Insausti, H.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Lee, D. H.; Wang, S.; Hart, J. E.; Mínguez-Alarcón, L.; Laden, F.; Ardisson Korat, A. V.; Birmann, B.; Heather Eliassen, A.; Willett, W. C.; Chavarro, J. E. Intake of Fruits and Vegetables by Pesticide Residue Status in Relation to Cancer Risk. Environment International 2021, 156, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Malmfors, T.; Krewski, D.; Mertz, C. K.; Neil, N.; Bartlett, S. Intuitive Toxicology. II. Expert and Lay Judgments of Chemical Risks in Canada. Risk Analysis 1995, 15, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Koyama, K.; Uehara, C.; Hirakawa, A.; Horiguchi, I. Changes in the Risk Perception of Food Safety between 2004 and 2018. Food Safety 2020, 8, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atreya, N. Pesticides in Perspective Does the Mere Precence of a Pesticide Residue in Food Indicate a Risk? J. Environ. Monitor. 2000, 2, 53N–56N. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, R. M. W.; Morris, J. Food Safety Risk: Consumer Perception and Purchase Behaviour. British Food Journal 2001, 103, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Frewer, L.; Rowe, G.; Houghton, J.; Kehagia, O.; Perrea, T. A Perceptual Divide? Consumer and Expert Attitudes to Food Risk Management in Europe. Health, Risk & Society 2007, 9, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vossen-Wijmenga, W. P.; Zwietering, M. H.; Boer, E. P. J.; Velema, E.; Den Besten, H. M. W. Perception of Food-Related Risks: Difference between Consumers and Experts and Changes over Time. Food Control 2022, 141, 109142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Guide to Ranking Food Safety Risks at the National Level; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-133282-5. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley, S. R.; Tucker, M. The Influence of Perceived Food Risk and Source Trust on Media System Dependency. Journal of Applied Communications 2004, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, K.; Gaskell, G. European Public Perceptions of Food Risk: Cross-National and Methodological Comparisons: European Public Perceptions of Food Risk. Risk Analysis 2008, 28, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoglou, K. B.; Roditakis, E. Consumers’ Benefit—Risk Perception on Pesticides and Food Safety—A Survey in Greece. Agriculture 2022, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Yan, S.; Fan, B. Regional Regulations and Public Safety Perceptions of Quality-of-Life Issues: Empirical Study on Food Safety in China. Healthcare 2020, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. R. D.; Hammitt, J. K. Perceived Risks of Conventional and Organic Produce: Pesticides, Pathogens, and Natural Toxins. Risk Analysis 2001, 21, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M. Trust and Risk Perception: A Critical Review of the Literature. Risk Analysis 2021, 41, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J. B.; Debbelt, C. A.; Schneider, F. M. Too Much Information? Predictors of Information Overload in the Context of Online News Exposure. Information, Communication & Society 2018, 21, 1151–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotelenets, E.; Barabash, V. Propaganda and Information Warfare in Contemporary World: Definition Problems, Instruments and Historical Context. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Man-Power-Law-Governance: Interdisciplinary Approaches (MPLG-IA 2019); Atlantis Press: Moscow, Russia; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C. A.; Renfrew, M. J.; Woolridge, M. W. Assessing the Risks of Pesticide Residues to Consumers: Recent and Future Developments. Food Additives and Contaminants 2001, 18, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiozzo, B.; Pinto, A.; Neresini, F.; Sbalchiero, S.; Parise, N.; Ruzza, M.; Ravarotto, L. Food Risk Communication: Analysis of the Media Coverage of Food Risk on Italian Online Daily Newspapers. Qual Quant 2019, 53, 2843–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybats, C.; Tredinnick, L. Post Truth, Information, and Emotion. Business Information Review 2016, 33, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlin, N. Fake News: Belief in Post-Truth. LHT 2017, 35, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, Ø.; Gunnlaugsdottir, H.; Holm, F.; Kalogeras, N.; Leino, O.; Luteijn, J. M.; Magnússon, S. H.; Odekerken, G.; Pohjola, M. V.; Tijhuis, M. J.; Tuomisto, J. T.; White, B. C.; Verhagen, H. State of the Art in Benefit–Risk Analysis: Consumer Perception. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012, 50, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, A. E.; Mazzocchi, M.; Traill, W. B. Modelling Risk Perception and Trust in Food Safety Information within the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Food Quality and Preference 2007, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; West, R.; Leskovec, J. Disinformation on the Web: Impact, Characteristics, and Detection of Wikipedia Hoaxes. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web; International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee: Montréal Québec Canada, 2016; pp. 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxa-Kakavouli, D.; Torres-Echeverry, N. Google’s Role in Spreading Fake News and Misinformation. SSRN Journal 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Sargeant, J. M.; Majowicz, S. E.; Sheldrick, B.; McKeen, C.; Wilson, J.; Dewey, C. E. Enhancing Public Trust in the Food Safety Regulatory System. Health Policy 2012, 107, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofstedt, R. E. How Can We Make Food Risk Communication Better: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? Journal of Risk Research 2006, 9, 869–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Application of Risk Communication to Food Standards and Safety Matters: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation, Rome, 2-6 February 1998; World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Ed.; FAO food and nutrition paper; World Health Organization ; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen, J. F. M.; McCluskey, J.; Francken, N. Food Safety, the Media, and the Information Market. Agricultural Economics 2005, 32, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, K. D. Public Perceptions of Food-Related Risks: A Cross-National Investigation of Individual and Contextual Influences. Journal of Risk Research 2019, 22, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, N. Communicating Risks Linked to Food – the Media’s Role. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2008, 19, S14–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.; Brennan, M.; De Boer, M.; Ritson, C. Media Risk Communication – What Was Said by Whom and How Was It Interpreted. Journal of Risk Research 2008, 11, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, H. P.; Dunwoody, S. Scientific Uncertainty in Media Content: Introduction to This Special Issue. Public Underst Sci 2016, 25, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehagia, O.; Chrysochou, P. The Reporting of Food Hazards by the Media: The Case of Greece. The Social Science Journal 2007, 44, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Epp, A.; Lohmann, M.; Böl, G.-F. Pesticide Residues in Food: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Misconceptions among Conventional and Organic Consumers. Journal of Food Protection 2017, 80, 2083–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarpa, P. El.; Garoufallou, E. Information Seeking Behavior and COVID-19 Pandemic: A Snapshot of Young, Middle Aged and Senior Individuals in Greece. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2021, 150, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Food-related risks. Report; Special Eurobarometer – 10. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/corporate_publications/files/reporten.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Food-related risks. Report; Special Eurobarometer – 19. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/corporate_publications/files/Eurobarometer2019_Food-safety-in-the-EU_Full-report.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th edition.; Cengage: Andover, Hampshire, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, B. E.; Bowen, N. K.; Faubert, S. J. Latent Class Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. Journal of Black Psychology 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The jamovi project. Jamovi (Version 2.3) -Computer Software. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.17.3) -Computer software. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Verbeke, W.; Frewer, L. J.; Scholderer, J.; De Brabander, H. F. Why Consumers Behave as They Do with Respect to Food Safety and Risk Information. Analytica Chimica Acta 2007, 586, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagianni, P.; Tsakiridou, E.; Tsakiridou, H.; Mattas, K. Consumer Perceptions about Fruit and Vegetable Quality Attributes: Evidence from a Greek Survey. Acta Hortic. 2003, No. 604, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, A.; Pun, M.; Khanona, J.; Aung, M. Consumer Attitudes, Knowledge and Behaviour: A Review of Food Safety Issues. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2004, 15, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Siegrist, M.; Keller, C. Attitudes toward Chemicals Are Associated with Preference for Natural Food. Food Quality and Preference 2011, 22, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sha, Y.; Song, X.; Yang, K.; ZHao, K.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Impact of Risk Perception on Customer Purchase Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. JBIM 2020, 35, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimara, E.; Skuras, D. Consumer Demand for Informative Labeling of Quality Food and Drink Products: A European Union Case Study. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2005, 22, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Chryssohoidis, G. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Organic Food: Factors That Affect It and Variation per Organic Product Type. British Food Journal 2005, 107, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Fotopoulos, C.; Zotos, Y. Organic Consumers’ Profile and Their Willingness to Pay (WTP) for Selected Organic Food Products in Greece. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2006, 19, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, E.; Zotos, Y.; Mattas, K. Employing a Dichotomous Choice Model to Assess Willingness to Pay (WTP) for Organically Produced Products. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2006, 12, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, E.; Boutsouki, C.; Zotos, Y.; Mattas, K. Attitudes and Behaviour towards Organic Products: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2008, 36, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, E.; Mattas, K.; Mpletsa, Z. Consumers’ Food Choices for Specific Quality Food Products. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2009, 15, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, E.; Mattas, K.; Tsakiridou, H.; Tsiamparli, E. Purchasing Fresh Produce on the Basis of Food Safety, Origin, and Traceability Labels. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2011, 17, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E.; Beus, C. E. Understanding Public Concerns About Pesticides: An Empirical Examination. Journal of Consumer Affairs 1992, 26, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Fischhoff, B.; Lichtenstein, S. Facts and fears: Understanding perceived risk. In Societal Risk Assessment: How Safe Is Safe Enough? Schwing, R.C., Albers, W.A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 181–216. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. L. Simultaneous-Equation Model for Estimating Consumer Risk Perceptions, Attitudes, and Willingness-to-Pay for Residue-Free Produce. Journal of Consumer Affairs 1993, 27, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leikas, S.; Lindeman, M.; Roininen, K.; Lähteenmäki, L. Who Is Responsible for Food Risks? The Influence of Risk Type and Risk Characteristics. Appetite 2009, 53, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchi, M.; Lobb, A.; Bruce Traill, W.; Cavicchi, A. Food Scares and Trust: A European Study: Food Scares and Trust: A European Study. Journal of Agricultural Economics 2008, 59, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembischevski, P.; Caldas, E. D. Risk Perception Related to Food. Food Sci. Technol 2020, 40, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H. The Multiple Dimensions of Information Quality. Information Systems Management 1996, 13, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, T. “Fake News”: False Fears or Real Concerns? Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 2017, 35, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables of focus | Mann-Whitney U Test | Rank-Biserial Correlation (*) | 95% CI for Rank-Biserial Correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| OINF: Official information sources | W = 8,249.0; p < 0.001 | −0.981 | −0.983 | −0.978 |

| BENEFIT: Perceived benefits | W = 283,684.0; p < 0.001 | −0.332 | −0.378 | −0.284 |

| GINF: General information sources | W = 344,139.0; p < 0.001 | −0.190 | −0.240 | −0.138 |

| TRACE: Confidence in traceability | W = 340,339.0; p < 0.001 | −0.198 | −0.249 | −0.147 |

| RISK: Perceived pesticides risk | W = 378,416.0; p < 0.001 | 0.109 | 0.056 | 0.161 |

| SAFE: Perceived plant-food safety | W = 387,926.0; p = 0.001 | −0.086 | −0.138 | −0.034 |

| Pesticide residues in food make me concerned about my safety | W = 428,532.0; p = 0.588 | 0.009 | −0.044 | 0.062 |

| In Greece plant food is not tested for pesticide residues as often as in other EU Member-States | W = 428,008.0; p = 0.760 | 0.008 | −0.045 | 0.061 |

| Background variables | Class 1 (N = 871) | Class 2 (N = 975) | Chi-Squared Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Non-Supporters” | “Supporters” | |||

| Gender | Female | 54.6 % | 45.4 % | Χ2 = 38.183; df = 1; |

| Μale | 40.2 % | 59.8 % | p < 0.001 | |

| Age | 18–44 | 47.6 % | 52.4 % | Χ2 = 0.112; df = 2; |

| ≥45 | 46.8 % | 53.2 % | p = 0.738 | |

| Place of residence | Rural | 40.6 % | 59.4 % | Χ2 = 10.908; df = 1; |

| Urban | 49.4 % | 50.6 % | p < 0.001 | |

| Region | Northern Greece | 52.8 % | 47.2 % | Χ2 = 14.271; df = 2; |

| Central Greece | 48.8 % | 51.2 % | p < 0.001 | |

| Southern Greece | 42.6 % | 57.4 % | ||

| I use pesticides | No | 61.6 % | 38.4 % | Χ2 = 207.455; df = 1; |

| Yes | 27.8 % | 72.2 % | p < 0.001 | |

| Profession | Civil servants | 53.1 % | 46.9 % | X2 = 36.611; df = 6; |

| Farmers | 30.6 % | 69.4 % | p < 0.001 | |

| Private employees | 42.2 % | 57.8 % | ||

| Retired | 42.5 % | 57.5 % | ||

| Self-employed | 37.9 % | 62.1 % | ||

| Unemployed | 45.1 % | 54.9 % | ||

| University students | 52.6 % | 47.4 % | ||

| Education | Secondary education | 52.6 % | 47.4 % | Χ2 = 6.488; df = 1; |

| Higher education | 45.6 % | 54.4 % | p = 0.011 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).