Submitted:

01 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Semen collection, sample preparation and experimental design

2.3. Motility Assessment

2.4. Viability Assessment

2.5. Preparation of whole cell lysates

2.6. Determination of Intracellular Glutathione

2.7. Determination of the Intracellular superoxide anion content

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

2.9. Statistical analysis

3. Results

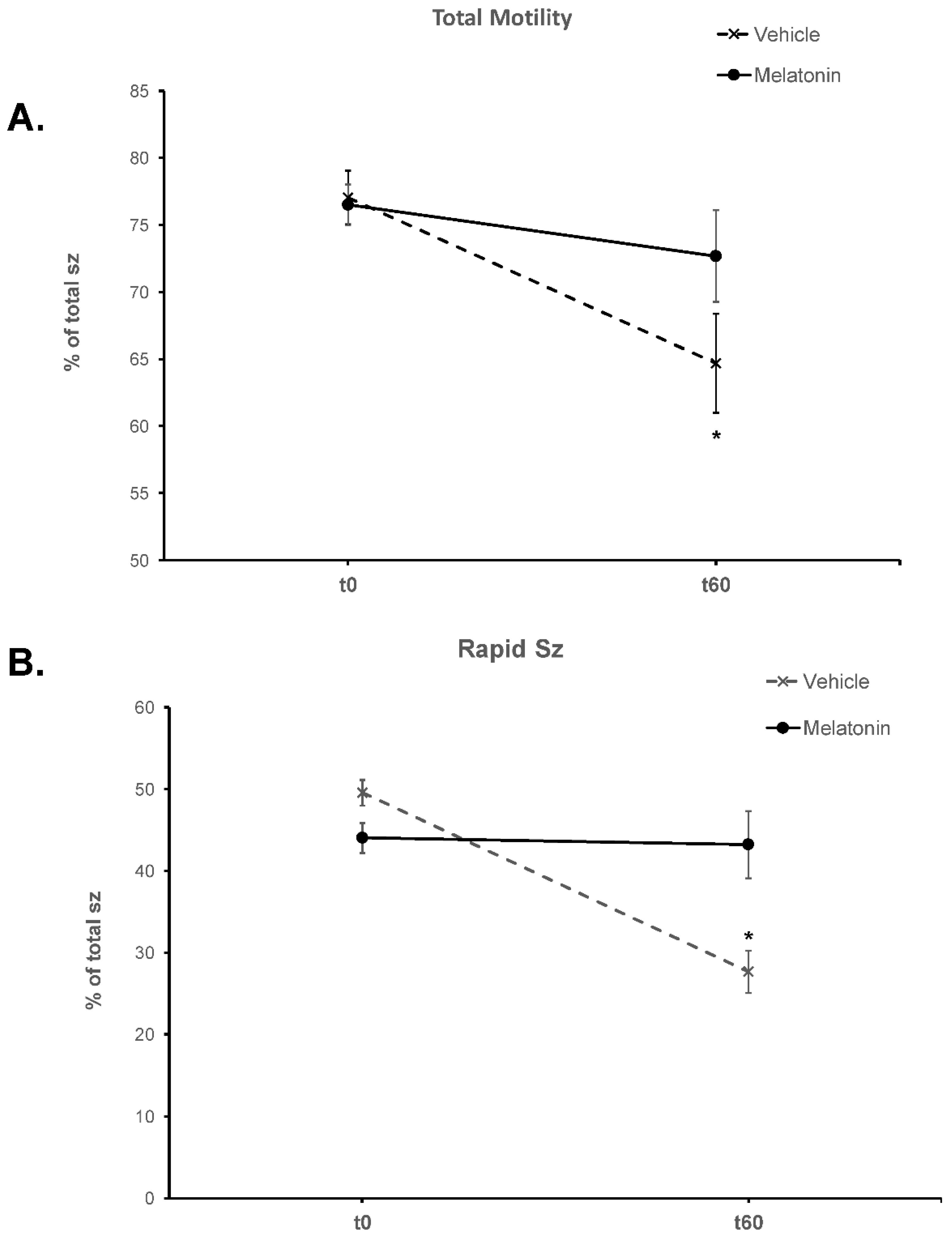

3.1. Melatonin inhibits the loss of motility over time during the handling of spermatozoa

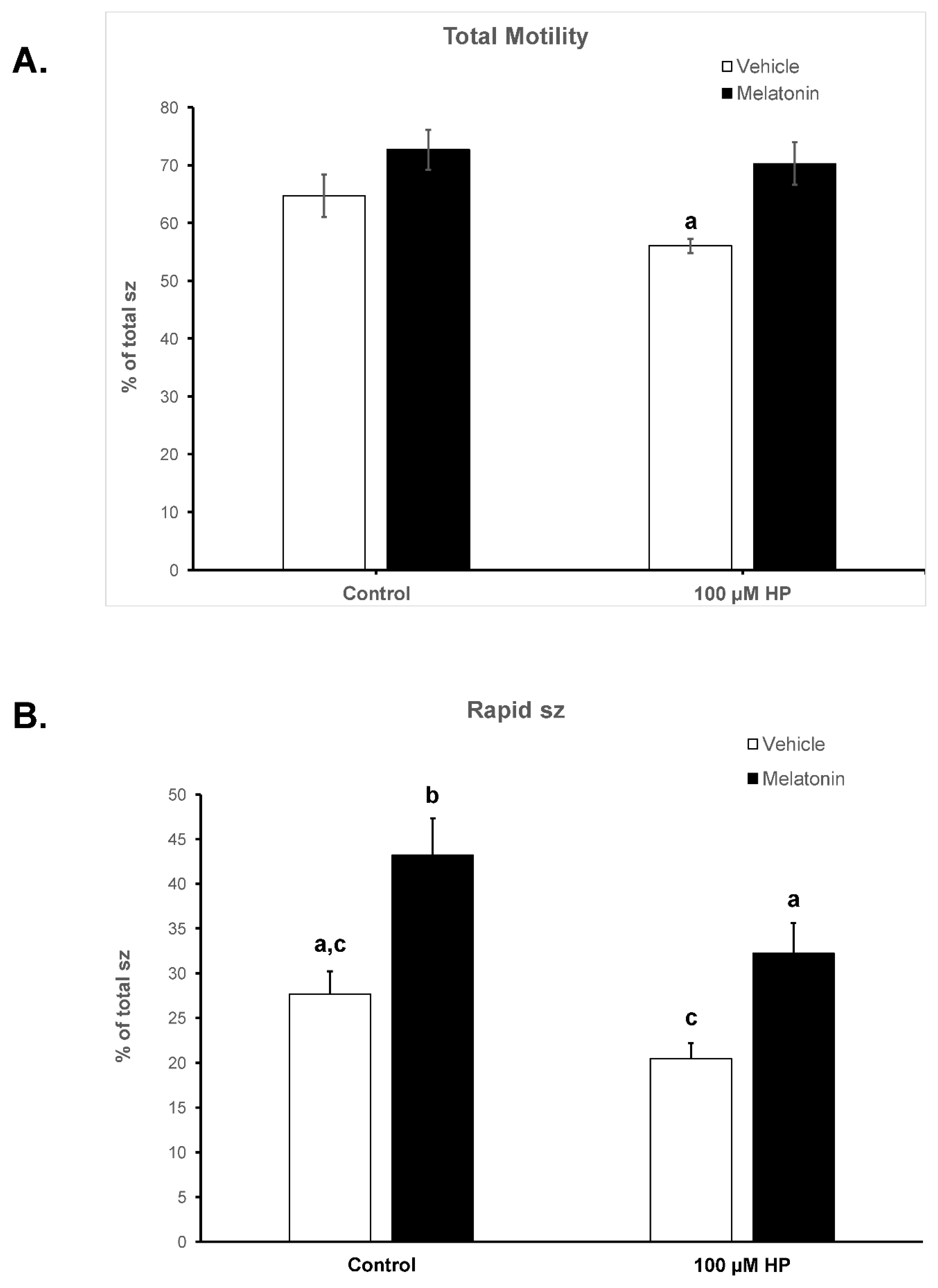

3.2. In the presence of melatonin, spermatozoa retain their motility during an insult by hydrogen peroxide

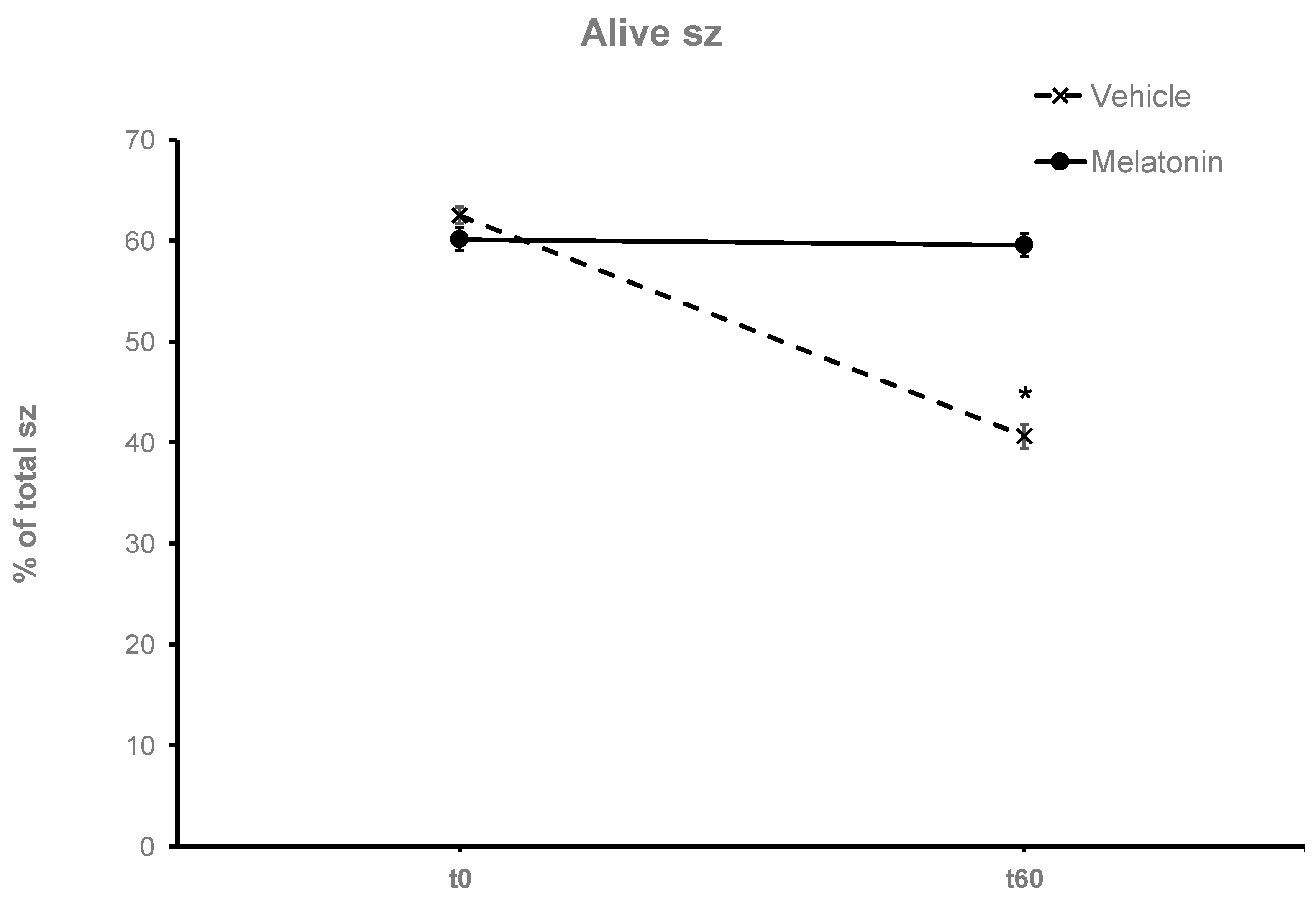

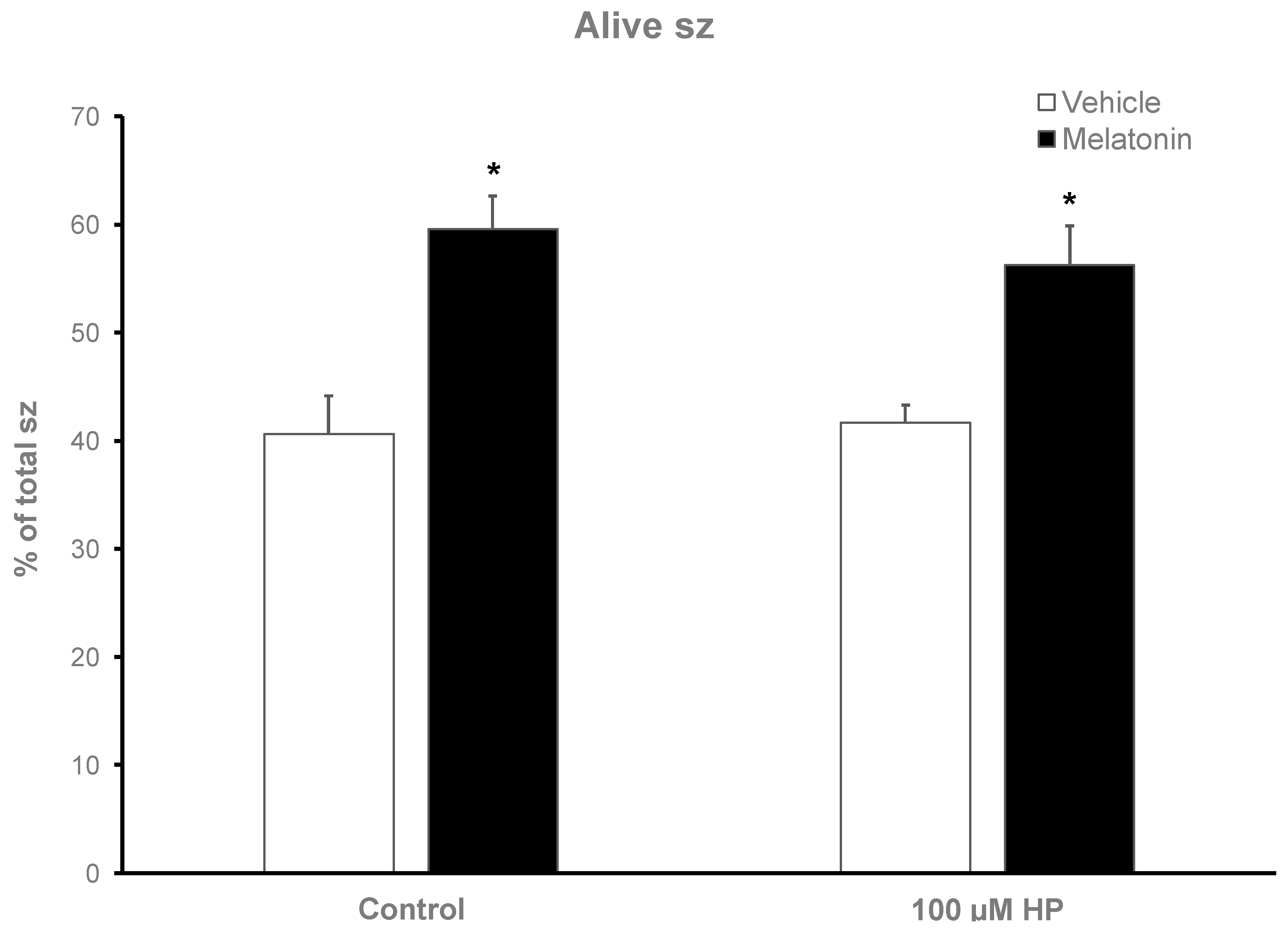

3.3. Melatonin protects viability of spermatozoa against oxidative stress

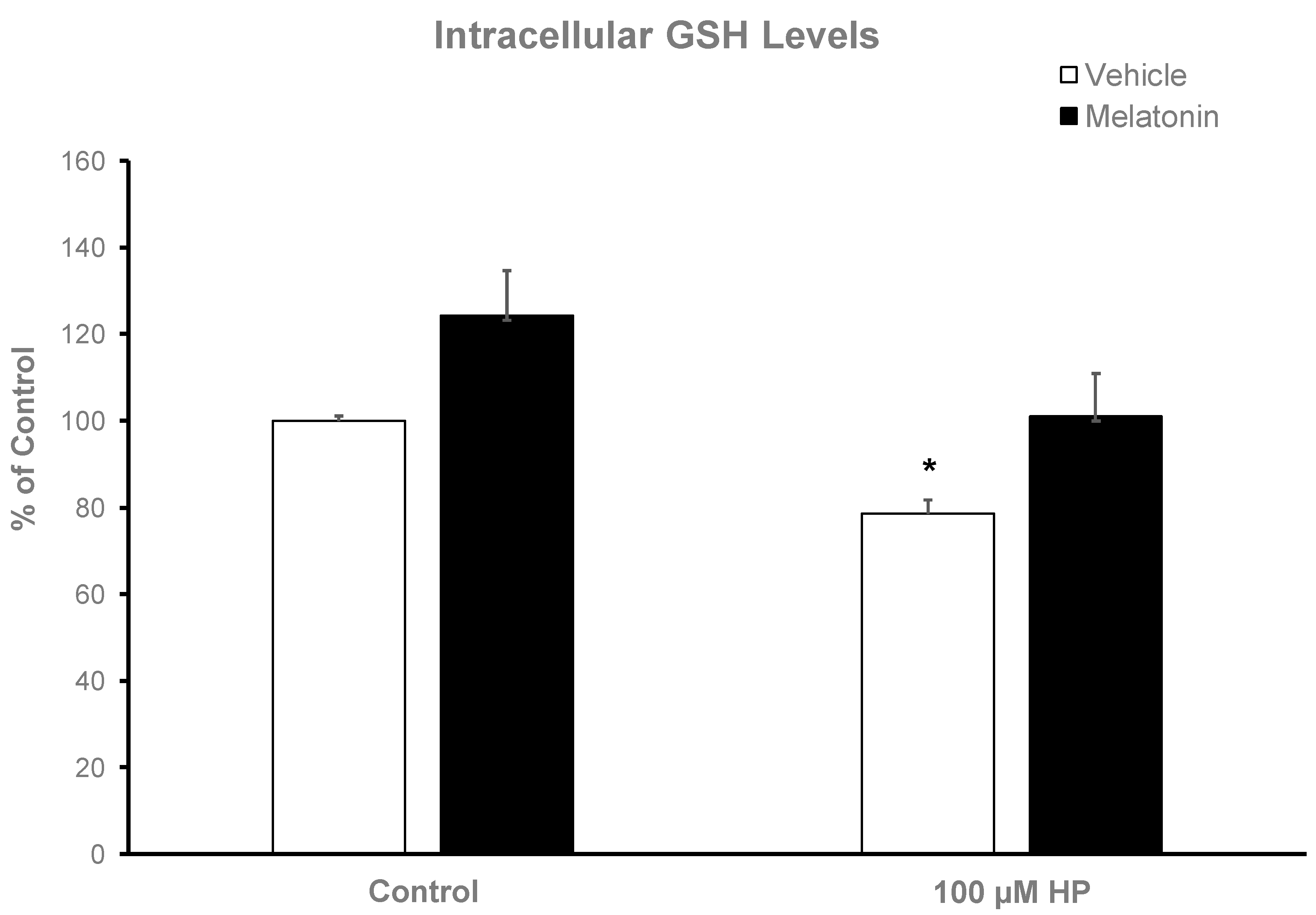

3.4. Melatonin increases the intracellular GSH content of spermatozoa

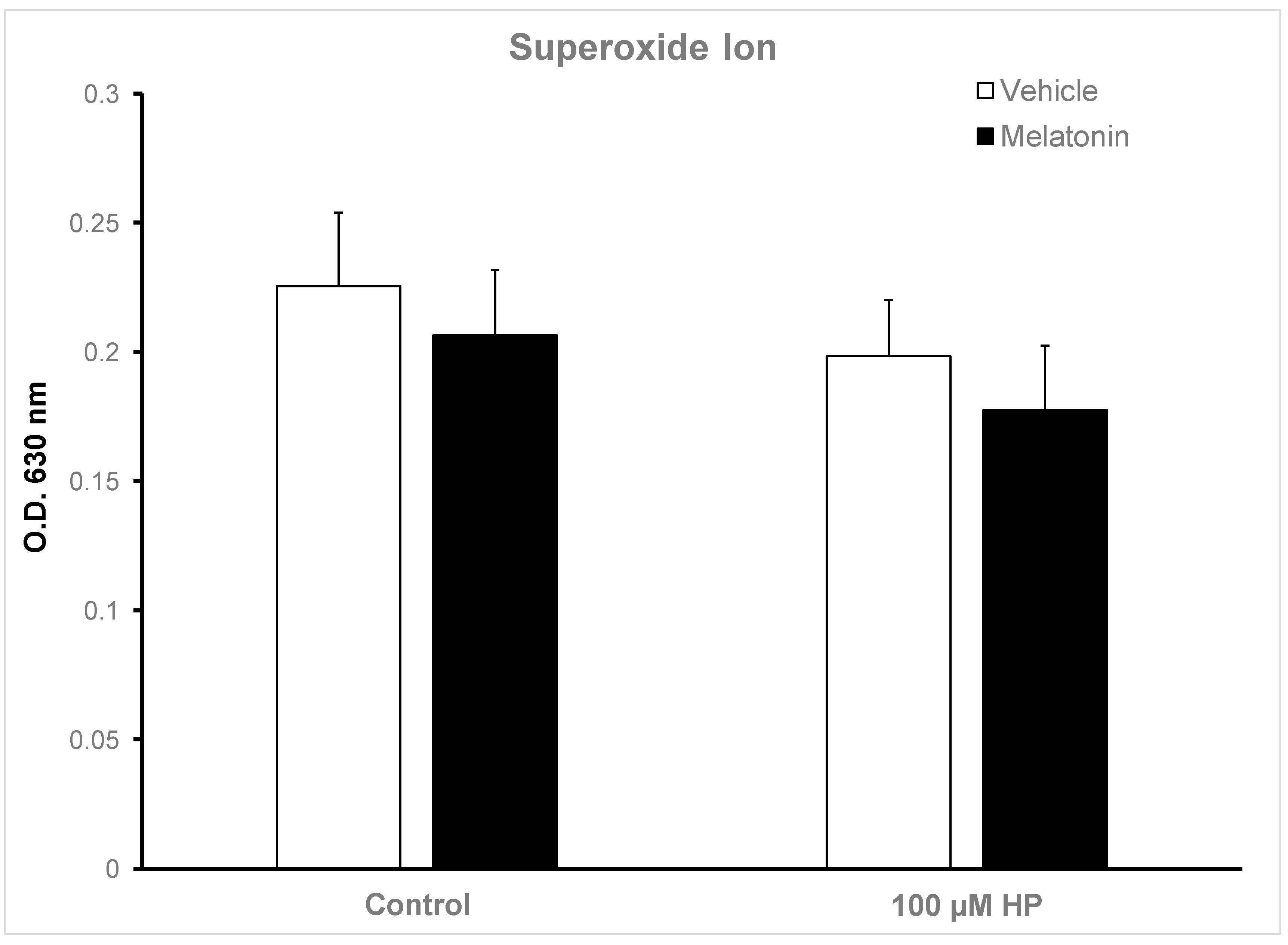

3.5. Melatonin does not affect the intracellular levels of superoxide ion)

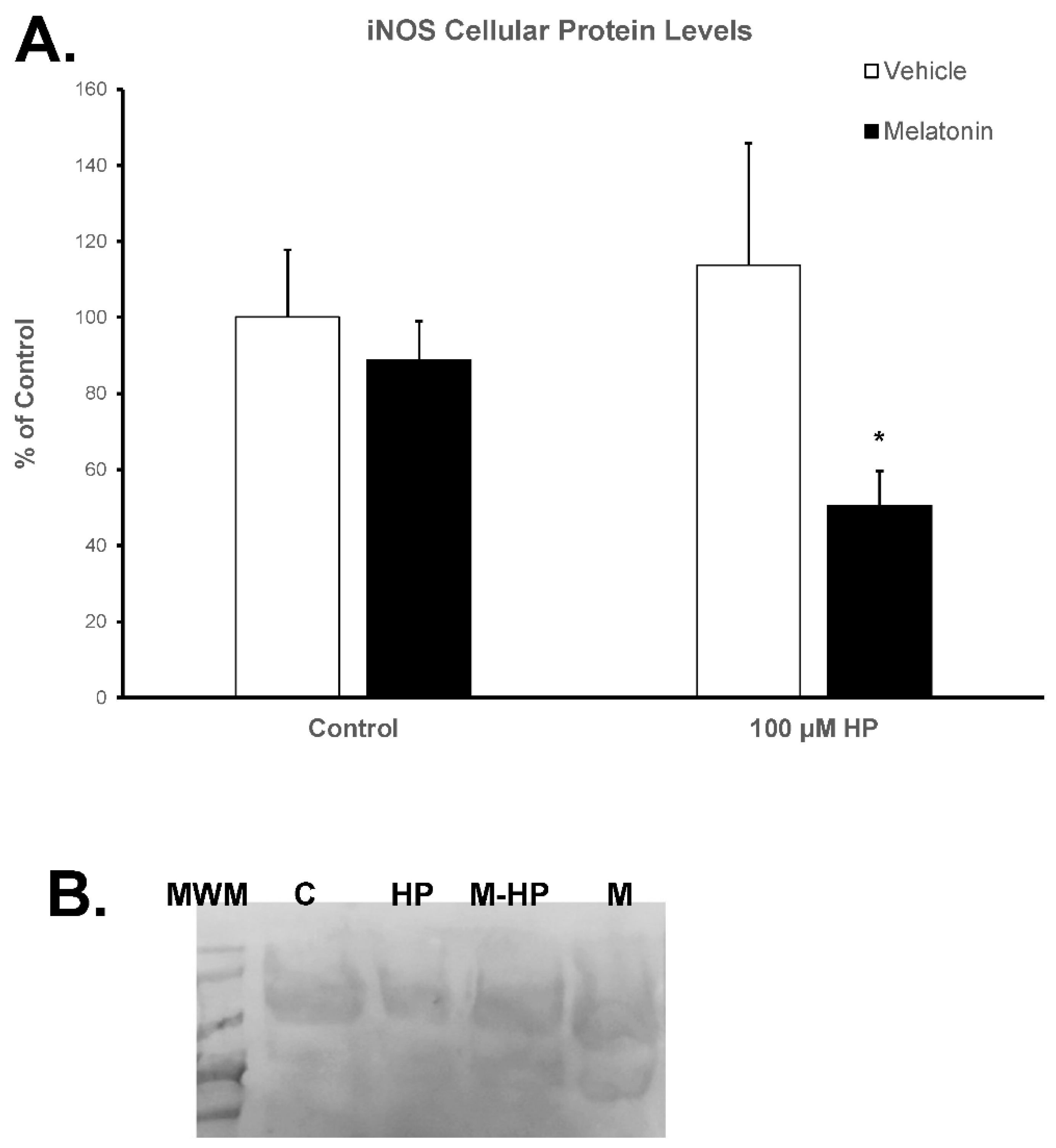

3.6. Melatonin reduces the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) protein levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez, M.; Majzoub, A. Best Laboratory Practices and Therapeutic Interventions to Reduce Sperm DNA Damage. Andrologia 2021, 53. [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M.R.; Saber Abdelrahman, A.; Evans, H.C.; Gilmore, A.A.; Hitit, M.; Arifiantini, R.I.; Purwantara, B.; Kaya, A.; Memili, E. Advances in Cryopreservation of Bull Sperm. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6, 268. [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, A.; Picardo, M.; Gandini, L.; Dondero, F. Lipids of the Sperm Plasma Membrane: From Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Considered as Markers of Sperm Function to Possible Scavenger Therapy. Hum Reprod Update 1996, 2, 246–256. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.W.; Zhang, H.; Ikemoto, I.; Anderson, D.J.; Loughlin, K.R. Reactive Oxygen Species Generation by Seminal Cells during Cryopreservation. Urology 1997, 49, 921–925. [CrossRef]

- Said, T.M.; Gaglani, A.; Agarwal, A. Implication of Apoptosis in Sperm Cryoinjury. Reprod Biomed Online 2010, 21, 456–462. [CrossRef]

- Safarinejad, M.R.; Hosseini, S.Y.; Dadkhah, F.; Asgari, M.A. Relationship of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids with Semen Characteristics, and Anti-Oxidant Status of Seminal Plasma: A Comparison between Fertile and Infertile Men. Clinical Nutrition 2010, 29, 100–105. [CrossRef]

- Baldi, E.; Tamburrino, L.; Muratori, M.; Degl’Innocenti, S.; Marchiani, S. Adverse Effects of in Vitro Manipulation of Spermatozoa. Anim Reprod Sci 2020, 220, 106314. [CrossRef]

- Tsantarliotou, M.P.; Sapanidou, V.G. The Importance of Antioxidants in Sperm Quality and in Vitro Embryo Production. Journal of Veterinary Andrology 2018, 3, 1–12.

- Sapanidou, V.; Tsantarliotou, M.P.; Lavrentiadou, S.N. A Review of the Use of Antioxidants in Bovine Sperm Preparation Protocols. Anim Reprod Sci 2023, 251, 107215. [CrossRef]

- Sapanidou, V.; Taitzoglou, I.; Tsakmakidis, I.; Kourtzelis, I.; Fletouris, D.; Theodoridis, A.; Lavrentiadou, S.; Tsantarliotou, M. Protective Effect of Crocetin on Bovine Spermatozoa against Oxidative Stress during in Vitro Fertilization. Andrology 2016, 4, 1138–1149. [CrossRef]

- Sapanidou, V.; Lavrentiadou, S.N.; Errico, M.; Panagiotidis, I.; Fletouris, D.; Efraimidis, I.; Zervos, I.; Taitzoglou, I.; Gasparrini, B.; Tsantarliotou, M. The Addition of Crocin in the Freezing Medium Extender Improves Post-Thaw Semen Quality. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2022, 57, 269–276. [CrossRef]

- Pintus, E.; Ros-Santaella, J.L. Impact of Oxidative Stress on Male Reproduction in Domestic and Wild Animals. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1154. [CrossRef]

- Pintus, E.; Luis, J.; Santaella, R.-; Drevet, J.R.; Sorrentino, R. Impact of Oxidative Stress on Male Reproduction in Domestic and Wild Animals. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bathgate, R. Antioxidant Mechanisms and Their Benefit on Post-Thaw Boar Sperm Quality. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2011, 46, 23–25. [CrossRef]

- Hacışevki, Aysun, and B.B. An Overview of Melatonin as an Antioxidant Molecule: A Biochemical Approach. In Melatonin - Molecular Biology, Clinical and Pharmaceutical Approaches; Drăgoi, C.M., Nicolae, A.C., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2018; pp. 59–85 ISBN 978-1-78984-504-4.

- Tsantarliotou, M.P.; Kokolis, N.A.; Smokovitis, A. Melatonin Administration Increased Plasminogen Activator Activity in Ram Spermatozoa. Theriogenology 2008, 69, 458–465. [CrossRef]

- Lialiaris, T.S. Melatonin in Prevention of Mutagenesis, Oxidation and Other Damage to Cells.; 2011.

- Casao, A.; Cebrián, I.; Asumpção, M.E.; Pérez-Pé, R.; Abecia, J.A.; Forcada, F.; Cebrián-Pérez, J.A.; Muiño-Blanco, T. Seasonal Variations of Melatonin in Ram Seminal Plasma Are Correlated to Those of Testosterone and Antioxidant Enzymes. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2010, 8, 59. [CrossRef]

- Monllor, F.; Espino, J.; Marchena, A.M.; Ortiz, Á.; Lozano, G.; García, J.F.; Pariente, J.A.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Bejarano, I. Melatonin Diminishes Oxidative Damage in Sperm Cells, Improving Assisted Reproductive Techniques. Turkish Journal of Biology 2017, 41, 881–889. [CrossRef]

- Espino, J.; Ortiz, Á.; Bejarano, I.; Lozano, G.M.; Monllor, F.; García, J.F.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Pariente, J.A. Melatonin Protects Human Spermatozoa from Apoptosis via Melatonin Receptor- and Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase-Mediated Pathways. Fertil Steril 2011, 95, 2290–2296. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rebolledo, A.E.; Fernández-Santos, M.R.; Bisbal, A.; Ros-Santaella, J.L.; Ramón, M.; Carmona, M.; Martínez-Pastor, F.; Garde, J.J. Improving the Effect of Incubation and Oxidative Stress on Thawed Spermatozoa from Red Deer by Using Different Antioxidant Treatments. Reprod Fertil Dev 2010, 22, 856–870. [CrossRef]

- Casao, A.; Abecia, J.A.; Cebrián-Pérez, J.A.; Muiño-Blanco, T.; Vázquez, M.I.; Forcada, F. The Effects of Melatonin on in Vitro Oocyte Competence and Embryo Development in Sheep | Efecto de La Melatonina En La Competencia Del Oocito y El Desarrollo Embrionario Ovino in Vitro. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2010, 8, 35–41. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, B.W.; Park, I.C.; Cheong, H.T.; Kim, J.T.; Park, C.K.; Kong, H.S.; Lee, H.K.; Yang, B.K. Ameliorative Effects of Melatonin against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress on Boar Sperm Characteristics and Subsequent in Vitro Embryo Development. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2010, 45, 943–950. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-Y.; Hao, H.-S.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Zhang, P.-P.; Wang, H.-Y.; Pang, Y.-W.; Du, W.-H.; Zhao, S.-J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.-M.; et al. Melatonin Improves the Fertilization Capacity of Sex-Sorted Bull Sperm by Inhibiting Apoptosis and Increasing Fertilization Capacitation via MT1. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.-W.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Jiang, X.-L.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Zhao, S.-J.; Du, W.-H.; Hao, H.-S.; Zhao, X.-M.; Zhu, H.-B. Protective Effects of Melatonin on Bovine Sperm Characteristics and Subsequent in Vitro Embryo Development. Mol Reprod Dev 2016, 83, 993–1002. [CrossRef]

- Carlos Gutié Rrez-Añez Id, J.; Henning, H.; Lucas-Hahn, A.; Baulain, U.; Aldag, P.; Sieg, B.; Hensel, V.; Herrmann, D.; Niemann, H. Melatonin Improves Rate of Monospermic Fertilization and Early Embryo Development in a Bovine IVF System. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alegre, E.; Álvarez-Fernández, I.; Domínguez, J.C.; Casao, A.; Martínez-Pastor, F. Melatonin Non-Linearly Modulates Bull Spermatozoa Motility and Physiology in Capacitating and Non-Capacitating Conditions. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Casao, A.; Gallego, M.; Abecia, J.A.; Forcada, F.; Pérez-Pé, R.; Muiño-Blanco, T.; Cebrián-Pérez, J.Á. Identification and Immunolocalisation of Melatonin MT(1) and MT(2) Receptors in Rasa Aragonesa Ram Spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil Dev 2012, 24, 953–961. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Arto, M.; Luna, C.; Pérez-Pé, R.; Muiño-Blanco, T.; Cebrián-Pérez, J.A.; Casao, A. New Evidence of Melatonin Receptor Contribution to Ram Sperm Functionality. Reprod Fertil Dev 2016, 28, 924–935. [CrossRef]

- Succu, S.; Berlinguer, F.; Pasciu, V.; Satta, V.; Leoni, G.G.; Naitana, S. Melatonin Protects Ram Spermatozoa from Cryopreservation Injuries in a Dose-Dependent Manner. J Pineal Res 2011, 50, 310–318. [CrossRef]

- Fujinoki, M. Melatonin-Enhanced Hyperactivation of Hamster Sperm. REPRODUCTION 2008, 136, 533–541. [CrossRef]

- Gwayi, N.; Bernard, R.T.F. The Effects of Melatonin on Sperm Motility in Vitro in Wistar Rats. Andrologia 2002, 34, 391–396. [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, I.; Kohram, H.; Ardabili, F.F. Antioxidative Effects of Melatonin on Kinetics, Microscopic and Oxidative Parameters of Cryopreserved Bull Spermatozoa. Anim Reprod Sci 2013, 139, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Cheuquemán, C.; Arias, M.E.; Risopatrón, J.; Felmer, R.; Álvarez, J.; Mogas, T.; Sánchez, R. Supplementation of IVF Medium with Melatonin: Effect on Sperm Functionality and in Vitro Produced Bovine Embryos. Andrologia 2015, 47, 604–615. [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Martos, S.; Casao, A.; Yeste, M.; Cebrián-Pérez, J.A.; Muiño-Blanco, T.; Pérez-Pé, R. Melatonin Reduces CAMP-Stimulated Capacitation of Ram Spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil Dev 2019, 31, 420–431. [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Zapico, C.; Coto-Montes, A. Melatonin as Antioxidant under Pathological Processes. Recent Patents on Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Drug Discov- ery 2007, 1, 63–82. [CrossRef]

- Gilad, E.; Wong, H.R.; Zingarelli, B.; Virág, L.; O’connor, M.; Salzman, A.L.; Szabó, C. Melatonin Inhibits Expression of the Inducible Isoform of Nitric Oxide Synthase in Murine Macrophages: Role of Inhibition of NFκB Activation. The FASEB Journal 1998, 12, 685–693. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Basang, W.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, X. Roles of Nitric Oxide in the Regulation of Reproduction: A Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Catt, J.W.; Henman, M. Toxic Effects of Oxygen on Human Embryo Development. Hum Reprod 2000, 15 Suppl 2, 199–206. [CrossRef]

- Gadea, J.; García-Vazquez, F.; Matás, C.; Gardón, J.C.; Cánovas, S.; Gumbao, D. Cooling and Freezing of Boar Spermatozoa: Supplementation of the Freezing Media with Reduced Glutathione Preserves Sperm Function. J Androl 2005, 26, 396–404. [CrossRef]

- Gadea, J.; Gumbao, D.; Cá novas, S.; Alberto García-Vá zquez, F.; Alberto Grulló, L.; Carlos Gardó, J. Supplementation of the Dilution Medium after Thawing with Reduced Glutathione Improves Function and the in Vitro Fertilizing Ability of Frozen-Thawed Bull Spermatozoa. [CrossRef]

- Sapanidou, V.; Taitzoglou, I.; Tsakmakidis, I.; Kourtzelis, I.; Fletouris, D.; Theodoridis, A.; Zervos, I.; Tsantarliotou, M. Antioxidant Effect of Crocin on Bovine Sperm Quality and in Vitro Fertilization. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 1273–1282. [CrossRef]

- Sapanidou, V.; Taitzoglou, I.; Tsakmakidis, I.; Kourtzelis, I.; Fletouris, D.; Theodoridis, A.; Lavrentiadou, S.; Tsantarliotou, M. Protective Effect of Crocetin on Bovine Spermatozoa against Oxidative Stress during in Vitro Fertilization. Andrology 2016. [CrossRef]

- Vajta, G.; Holm, P.; Greve, T.; Callesen, H. Factors Affecting Survival Rates of in Vitro Produced Bovine Embryos after Vitrification and Direct In-Straw Rehydration. Anim Reprod Sci 1996, 45, 191–200. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.T.; Squiers, C.D.; Bogart, R.; Oloufa, M.M. The Technique for Characterizing Mammalian Spermatozoa as Dead or Living by Differential Staining. J Anim Sci 1951, 10, 226–235. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, A.; Petrotos, K.; Stagos, D.; Gerasopoulos, K.; Maimaris, A.; Makris, H.; Kafantaris, I.; Makri, S.; Kerasioti, E.; Halabalaki, M.; et al. Enhancement of Antioxidant Mechanisms and Reduction of Oxidative Stress in Chickens after the Administration of Drinking Water Enriched with Polyphenolic Powder from Olive Mill Waste Waters. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017.

- Becerra, M.C.; Eraso, A.J.; Albesa, I. Comparison of Oxidative Stress Induced by Ciprofloxacin and Pyoverdin in Bacteria and in Leukocytes to Evaluate Toxicity. Luminescence 2003, 18, 334–340. [CrossRef]

- Katsipis, G.; Tzekaki, E.E.; Tsolaki, M.; Pantazaki, A.A. Salivary GFAP as a Potential Biomarker for Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Correlation with Neuroinflammation and Apoptosis. J Neuroimmunol 2021, 361, 577744. [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, R.; Kalthur, G.; Barbato, V.; Longobardi, S.; Rella, F. Di; Adiga, S.K.; Talevi, R.; Moretti, E. Sperm Oxidative Stress during In Vitro Manipulation and Its Effects on Sperm Function and Embryo Development. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Toor, J.S.; Sikka, S.C. Chapter 1.6 - Human Spermatozoa and Interactions With Oxidative Stress. In Oxidants, Antioxidants and Impact of the Oxidative Status in Male Reproduction; Henkel, R., Samanta, L., Agarwal, A., Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 45–53 ISBN 978-0-12-812501-4.

- O’Flaherty, C.; de Lamirande, E.; Gagnon, C. Positive Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Mammalian Sperm Capacitation: Triggering and Modulation of Phosphorylation Events. Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 41, 528–540. [CrossRef]

- de Lamirande, E.; O’Flaherty, C. Sperm Activation: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2008, 1784, 106–115. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.K.; Bilaspuri, G.S. Impacts of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants on Semen Functions. Vet Med Int 2011, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.K.; Bilaspuri, G.S. Oxidative Stress Alters Membrane Sulfhydryl Status, Lipid and Phospholipid Contents of Crossbred Cattle Bull Spermatozoa. Anim Reprod Sci 2008, 104, 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Said, T.M.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Banerjee, J.; Alvarez, J.G. Oxidative Stress in an Assisted Reproductive Techniques Setting. Fertil Steril 2006, 86, 503–512. [CrossRef]

- Nicole McPherson, and; Agarwal, A.; Maldonado Rosas, I.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Cannarella, R.; Boitrelle, F.; Villar Munoz, L.; Finelli, R.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Henkel, R.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Assisted Reproduction: A Comprehensive Review of Its Pathophysiological Role and Strategies for Optimizing Embryo Culture Environment. Mexico; imaldonado@citmer.mx (I.M.R 1152, 11, 477. [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, P.; Fair, T. Maturation of Oocytes in Vitro. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 2016, 4, 255–268. [CrossRef]

- Rizos, D.; Clemente, M.; Bermejo-Alvarez, P.; De La Fuente, J.; Lonergan, P.; Gutiérrez-Adán, A. Consequences of in Vitro Culture Conditions on Embryo Development and Quality. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2008, 43, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Martins da Silva, S.J. DNA Fragmentation, Antioxidants and ART. In Assisted Reproduction Techniques; 2021; pp. 606–611 ISBN 9781119622215.

- Agarwal, A.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Du Plessis, S.S. Utility of Antioxidants during Assisted Reproductive Techniques: An Evidence Based Review; 2014;

- Reiter, RusselJ.; Tan, D.-X.; Cabrera, J.; D’Arpa, D.; Sainz, RosaM.; Mayo, J.; Ramos, S. The Oxidant/Antioxidant Network: Role of Melatonin. Biol Signals Recept 1999, 8, 56–63. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S.M.; Amir, ·; Wani, B.; Rahil, ·; Bhat, R.; Muneeb, ·; Rehman, U.; et al. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 43, 2437–2458. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, M.; Tang, J.; Xu, Z. Melatonin in Reproductive Medicine: A Promising Therapeutic Target? Curr Med Chem 2023, 30, 3090–3118. [CrossRef]

- Dehdari Ebrahimi, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Ala, M.; Ebrahimi, F.; Pakbaz, S.; Azarpira, N. Protective Effects of Melatonin against Oxidative Stress Induced by Metabolic Disorders in the Male Reproductive System: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Rodent Models. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dehdari Ebrahimi, N.; Shojaei-Zarghani, S.; Taherifard, E.; Dastghaib, S.; Parsa, S.; Mohammadi, N.; Sabet Sarvestani, F.; Moayedfard, Z.; Hosseini, N.; Safarpour, H.; et al. Protective Effects of Melatonin against Physical Injuries to Testicular Tissue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Animal Models. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.R.; Silva, J.R.V. Mechanisms of Action of Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants to Control Oxidative Stress during in Vitro Follicle Growth, Oocyte Maturation, and Embryo Development. Anim Reprod Sci 2023, 249. [CrossRef]

- Role, W.; S Silva, A.M.; Kim, Y.-B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Lu, W. Citation: Molecules Role of Melatonin in Bovine Reproductive Biotechnology. 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Griveau, J.E.; Renard, P.; Lannou, D.L. An in Vitro Promoting Role for Hydrogen Peroxide in Human Sperm Capacitation. Int J Androl 1994, 17, 300–307. [CrossRef]

- Rivlin, J.; Mendel, J.; Rubinstein, S.; Etkovitz, N.; Breitbart, H. Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Sperm Capacitation and Acrosome Reaction1. Biol Reprod 2004, 70, 518–522. [CrossRef]

- ChaithraShree, A.R.; Ingole, S.D.; Dighe, V.D.; Nagvekar, A.S.; Bharucha, S. V; Dagli, N.R.; Kekan, P.M.; Kharde, S.D. Effect of Melatonin on Bovine Sperm Characteristics and Ultrastructure Changes Following Cryopreservation. Vet Med Sci 2020, 6, 177–186. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, X. Melatonin and Male Reproduction. Clinica Chimica Acta 2015, 446, 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Espino, J.; Bejarano, I.; Lozano, G.M.; Monllor, F.; García, J.F.; Pariente, J.A.; Rodríguez, A.B. High Endogenous Melatonin Concentrations Enhance Sperm Quality and Short-Term in Vitro Exposure to Melatonin Improves Aspects of Sperm Motility. J Pineal Res 2010, 50, 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Cebrián-Pérez, J.A.; Casao, A.; González-Arto, M.; dos Santos Hamilton, T.R.; Pérez-Pé, R.; Muiño-Blanco, T. Melatonin in Sperm Biology: Breaking Paradigms. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2014, 49, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, C.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Radi, R. Peroxynitrite: Biochemistry, Pathophysiology and Development of Therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007, 6, 662–680. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.; Reiter, R.J.; Topal, T.; Manchester, L.C.; Oter, S.; Tan, D.-X. Melatonin: An Established Antioxidant Worthy of Use in Clinical Trials. Molecular Medicine 2009, 15, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, S.S.; Hagenaar, K.; Lampiao, F. The in Vitro Effects of Melatonin on Human Sperm Function and Its Scavenging Activities on NO and ROS. Andrologia 2010, 42, 112–116. [CrossRef]

- Alderton, W.K.; Cooper, C.E.; Knowles, R.G. Nitric Oxide Synthases: Structure, Function and Inhibition. Biochemical Journal 2001, 357, 593–615. [CrossRef]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Trakht, I.; Srinivasan, V.; Spence, D.W.; Maestroni, G.J.M.; Zisapel, N.; Cardinali, D.P. Physiological Effects of Melatonin: Role of Melatonin Receptors and Signal Transduction Pathways. Prog Neurobiol 2008, 85, 335–353. [CrossRef]

| Group | Total motile (%) | Static (%) | Rapid (%) |

Medium (%) | Slow (%) |

PM | VCL | VSL | VAP | ALH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control t0 | 77.05±1.99 | 22.95±1.99 | 49.57±1.52 | 22.38±1.14 | 5.12±1.17 | 21.16±1.74 | 60.89±3.17 | 19.43±1.19* | 34.52±1.87b,d,e | 3.26±0.16* |

| Melatonin t0 | 76.5±1.53 | 24.33±1.93 | 44.03±1.84 | 25.94±1.37 | 6.53±0.9 | 23.77±1.55 | 59.58±1.22 | 20.93±0.57* | 35.83±0.46b,d,e | 3.09±0.08 |

| Control t60 | 61.9±3.69a,b,d | 35.32±3.69 | 27.67±2.58a,b,c | 28.15±1.27 | 8.87±0.74 | 23.58±2.23 | 49.82±1.68a,b | 18.55±0.96 | 30.47±1.09b,c,e | 2.72±0.2 |

| Control t60-HP | 54.96±1.2a,b | 43.98±1.27 | 20.48±1.73a,b,c | 25.53±1.19 | 10.02±0.85 | 20.25±4.62 | 43.72±5.6a,b,c | 17.83±1.89 | 23.85±4.17a,b,c | 2.93±0.05 |

| Melatonin t60 | 72.68±3.42b,c | 23.98±4 | 43.22±4.13 | 23.58±1.79 | 5.88±0.63 | 24.3±4.38 | 62.15±1.84 | 21.55±1.95* | 36.67±1.49d, | 3.38±0.18* |

| Melatonin t60-HP | 70.32±4.51a,c,d | 34.43±3.36 | 32.2±3.39a,b | 25.77±2.29 | 9.27±1.46 | 19.12±2.81 | 54.38±4.31b,c | 18.4±1.08 | 32±1.93b,c,d | 3.18±0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).