Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Local and Animals

2.2. Semen extender, antioxidants supplementation and experimental design

2.3. Semen collection and processing

2.4. Seminal assessment

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allai, L.; Benmoula, A.; Marciane da Silva, M.; Nasser, B.; El Amiri, B. Supplementation of Ram Semen Extender to Improve Seminal Quality and Fertility Rate. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 192, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binyameen, M.; Saleem, M.; Riaz, A. Recent Trends in Bovine Reproductive Biotechnologies. CAB Rev. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F. The Causes of Reduced Fertility with Cryopreserved Semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2000, 60–61, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Wu, G.; Hong, Q.; Quan, G. Spermatozoa Cryopreservation: State of Art and Future in Small Ruminants. Biopreserv. Biobanking 2019, 17, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, A.; Contreras, C.Bs.; Herrera, F.; Alcantar-Rodriguez, A. Melatonin as an Antioxidant Preserving Sperm from Domestic Animals. Asian Pac. J. Reprod. 2017, 6, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, S.; Finelli, R.; Agarwal, A.; Henkel, R. Reactive Oxygen Species in Male Reproduction: A Boon or a Bane? Andrologia 2021, 53, e13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, S.A. Cryostorage and Oxidative Stress in Mammalian Spermatozoa. In Studies on Men’s Health and Fertility; Agarwal, A., Aitken, R.J., Alvarez, J.G., Eds.; Oxidative Stress in Applied Basic Research and Clinical Practice; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2012; pp. 41–56. ISBN 978-1-61779-775-0. [Google Scholar]

- Soren, S.; Singh, S.V.; Singh, P. Influence of Season on Seminal Antioxidant Enzymes in Karan Friesbulls under Tropical Climatic Conditions. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2016, 40, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, E.; Marti, J.I.; Muino-Blanco, T.; Cebrian-Perez, J.A. Effect of the Cryopreservation Process on the Activity and Immunolocalization of Antioxidant Enzymes in Ram Spermatozoa. J. Androl. 2008, 29, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadea, J.; Sellés, E.; Marco, M.A.; Coy, P.; Matás, C.; Romar, R.; Ruiz, S. Decrease in Glutathione Content in Boar Sperm after Cryopreservation. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, Y.; Wen, F.; Feng, T.; Hu, J. Effect of Addition of Melatonin on Liquid Storage of Ram Semen at 4 °C. Andrologia 2019, 51, e13236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadea, J.; Gumbao, D.; Gómez-Giménez, B.; Gardón, J.C. Supplementation of the Thawing Medium with Reduced Glutathione Improves Function of Frozen-Thawed Goat Spermatozoa. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 13, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezo, F.; Yeste, M.; Zambrano, F.; Uribe, P.; Risopatrón, J.; Sánchez, R. Antioxidants and Their Effect on the Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress of Frozen-Thawed Boar Sperm. Cryobiology 2021, 98, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucak, M.N.; Ateşşahin, A.; Yüce, A. Effect of Anti-Oxidants and Oxidative Stress Parameters on Ram Semen after the Freeze–Thawing Process. Small Ruminant Research 2008, 75, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Ahsan, H.; Zia, M.K.; Siddiqui, T.; Khan, F.H. Understanding Oxidants and Antioxidants: Classical Team with New Players. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadea, J.; Molla, M.; Selles, E.; Marco, M.A.; Garcia-Vazquez, F.A.; Gardon, J.C. Reduced Glutathione Content in Human Sperm Is Decreased after Cryopreservation: Effect of the Addition of Reduced Glutathione to the Freezing and Thawing Extenders. Cryobiology 2011, 62, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Wei, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Cao, P.; Yang, S.; Li, G. Effect of Glutathione on Sperm Quality in Guanzhong Dairy Goat Sperm During Cryopreservation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 771440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Jin, T.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Niu, H.; Ren, Y. Effects of Reduced Glutathione on Ram Sperm Parameters, Antioxidant Status, Mitochondrial Activity and the Abundance of Hexose Transporters during Liquid Storage at 5 ℃. Small Ruminant Research 2020, 189, 106139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an Antioxidant: Under Promises but over Delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minucci, S.; Venditti, M. New Insight on the In Vitro Effects of Melatonin in Preserving Human Sperm Quality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyawilert, W.; Rungruangsak, J.; Liao, Y.; Tang, P.; Paungsukpaibool, V. Melatonin Supplementation Improved Cryopreserved Thai Swamp Buffalo Semen. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2021, 56, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M.O.; He, B.; Lu, W.; Wang, J. Antioxidative Effect of Melatonin on Cryopreserved Chicken Semen. Cryobiology 2019, 89, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadl, A.M.; Ghallab, A.R.M.; Abou-Ahmed, M.M.; Moawad, A.R. Melatonin Can Improve Viability and Functional Integrity of Cooled and Frozen/Thawed Rabbit Spermatozoa. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2021, 56, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Rodriguez, J.A.; Carbajal, F.J.; Martinez-De-Anda, R.; Alcantar-Rodriguez, A.; Medrano, A. Melatonin Added to Freezing Diluent Improves Canine (Bulldog) Sperm Cryosurvival. Reproduction and Fertility 2020, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahandeh, E.; Ghorbani, M.; Mokhlesabadifarahani, T.; Bardestani, F. Melatonin and Selenium Supplementation in Extenders Improves the Post-Thaw Quality Parameters of Rat Sperm. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2022, 49, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipolla-Neto, J.; Amaral, F.G. Melatonin as a Hormone: New Physiological and Clinical Insights. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 990–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, C.; Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antolin, I.; Herrera, F.; Martin, V.; Reiter, R.J. Regulation of Antioxidant Enzymes: A Significant Role for Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu, J.; Qazi, I.H.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, G. Use of Melatonin in Sperm Cryopreservation of Farm Animals: A Brief Review. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 233, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbas, J.P.; Pimenta, J.; Baptista, M.C.; Marques, C.C.; Pereira, R.M.L.N.; Carolino, N.; Simões, J. Ram Semen Cryopreservation for Portuguese Native Breeds: Season and Breed Effects on Semen Quality Variation. Animals 2023, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel, A.J.F.; Doney, J.M.; Gunn, R.G. Subjective Assessment of Body Fat in Live Sheep. J. Agric. Sci. 1969, 72, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Hernández, P.R.; Simões, J.; Barbas, J.P. Effects of Three Semen Extenders, Breeding Season Month and Freezing–Thawing Cycle on Spermatozoa Preservation of Portuguese Merino Sheep. Animals 2021, 11, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChaithraShree, A.R.; Ingole, S.D.; Dighe, V.D.; Nagvekar, A.S.; Bharucha, S.V.; Dagli, N.R.; Kekan, P.M.; Kharde, S.D. Effect of Melatonin on Bovine Sperm Characteristics and Ultrastructure Changes Following Cryopreservation. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banday, M.N.; Lone, F.A.; Rasool, F.; Rashid, M.; Shikari, A. Use of Antioxidants Reduce Lipid Peroxidation and Improve Quality of Crossbred Ram Sperm during Its Cryopreservation. Cryobiology 2017, 74, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmani, H.; Nabi, M.M.; Vaseghi-Dodaran, H.; Rahman, M.B.; Mohammadi-Sangcheshmeh, A.; Shakeri, M.; Towhidi, A.; Shahneh, A.Z.; Zhandi, M. Effect of Glutathione in Soybean Lecithin-Based Semen Extender on Goat Semen Quality after Freeze-Thawing. Small Ruminant Research 2013, 112, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcay, S.; Ustuner, B.; Nur, Z. Effects of Low Molecular Weight Cryoprotectants on the Post-Thaw Ram Sperm Quality and Fertilizing Ability. Small Ruminant Research 2016, 136, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, N.; Erdogan, C.; Bucak, M.N.; Ozturk, A.E.; Bodu, M.; Ili, P.; Baspinar, N.; Dursun, S. Cryopreservation Effects on Ram Sperm Ultrastructure. Biopreserv. Biobanking 2020, 18, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, A. Energy Metabolism in Mammalian Sperm Motility. WIREs Mech. Dis. 2022, 14, e1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Hoek, M.; Rickard, J.P.; De Graaf, S.P. Motility Assessment of Ram Spermatozoa. Biology 2022, 11, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaretta, E.; Estrada, E.; Bucci, D.; Spinaci, M.; Rodríguez-Gil, J.E.; Yeste, M. Combining Reduced Glutathione and Ascorbic Acid Has Supplementary Beneficial Effects on Boar Sperm Cryotolerance. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.S.; Rakha, B.A.; Ullah, N.; Andrabi, S.M.H.; Iqbal, S.; Khalid, M.; Akhter, S. Effect of Exogenous Glutathione in Extender on the Freezability of Nili-Ravi Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis) Bull Spermatozoa. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2010, 28, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.; Soares, A.; Batista, A.; Almeida, F.; Nunes, J.; Peixoto, C.; Guerra, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Ram Sperm Frozen in Tris Egg-Yolk and Supplemented with Superoxide Dismutase and Reduced Glutathione: In Vitro and In Vivo Effect of the Addition of SOD and GSH. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2011, 46, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, R.A.; Wolf, C.A.; De Oliveira Viu, M.A.; Gambarini, M.L. Addition of Glutathione to an Extender for Frozen Equine Semen. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 2013, 33, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succu, S.; Berlinguer, F.; Pasciu, V.; Satta, V.; Leoni, G.G.; Naitana, S. Melatonin Protects Ram Spermatozoa from Cryopreservation Injuries in a Dose-Dependent Manner: Melatonin Mitigates Cryopreservation Injuries of Ram Spermatozoa. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 50, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, I.; Kohram, H.; Naijian, H.; Bahreini, M.; Poorhamdollah, M. Protective Effect of Melatonin on Sperm Motility Parameters on Liquid Storage of Ram Semen at 5 °C. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 6670–6674. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, A.T.; Brito, L.; Althouse, G.; Aurich, C.; Chenoweth, P.; Fraser, N.; Lopate, C.; Love, C.; Luvoni, G.; Waberski, D. Andrology Laboratory Review: Evaluation of Sperm Motility. Clinical Theriogenology 2021, 13, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wu, D.; Liang, M.; Huang, S.; Shi, D.; Li, X. The Effects of Melatonin, Glutathione and Vitamin E on Semen Cryopreservation of Mediterranean Buffalo. Theriogenology 2023, 197, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagbonsi, I.A.; Olayaki, L.A. Melatonin Attenuates Δ 9 -Tetrahydrocannabinol-Induced Reduction in Rat Sperm Motility and Kinematics in-Vitro. Reprod. Toxicol. 2018, 77, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnaugh, L.; Ball, B.A.; Sabeur, K.; Thomas, A.D.; Meyers, S.A. Osmotic Stress Stimulates Generation of Superoxide Anion by Spermatozoa in Horses. Animal Reproduction Science 2010, 117, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalothia, S.K.; Mehta, J.S.; Kumar, T.; Prakash, C.; Talluri, T.R.; Pal, R.S.; Kumar, A. Melatonin and Canthaxanthin Enhances Sperm Viability and Protect Ram Spermatozoa from Oxidative Stress during Liquid Storage at 4 °C. Andrologia 2022, 54, e14304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Fixed Variables | Interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semen processing (SP) | Group (G) | SP x G | |

| IM | *** | NS | NS |

| Alive | *** | NS | NS |

| Death | *** | NS | NS |

| Abnormal | ** | NS | NS |

| Head defects | *** | NS | NS |

| IP defects | NS | NS | NS |

| Tail defects | *** | NS | NS |

| TS | *** | * | NS |

| TM | *** | NS | NS |

| TPM | *** | ** | *** |

| Slow | *** | * | NS |

| Medium | *** | * | * |

| Rapid | *** | NS | NS |

| VCL | *** | * | * |

| VSL | *** | *** | *** |

| VAP | *** | *** | ** |

| ALH | *** | NS | NS |

| LIN | ** | NS | ** |

| STR | NS | NS | *** |

| WOB | *** | ** | NS |

| BCF | *** | * | * |

| Parameters | G1 (Control) | G2 (Melatonin) | G3 (GSH) | G4 (GSH + Melatonin) | ±(Sqrt)SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Thawed | Fresh | Thawed | Fresh | Thawed | Fresh | Thawed | ||

| Alive (%) | 78.7 a | 40.1 b | 79.1 a | 38.1 b | 80.9 a | 40.9 b | 82.9 a | 41.1 b | 0.17 |

| Death (%) | 20.9 a | 58.8 b | 20.0 a | 61.7 b | 18.6 a | 58.8 b | 16.6 a | 58.4 b | 0.22 |

| IM (%) | 60.0 a | 39.7 b | 58.7 a | 37.2 b | 58.7 a | 40.3 b | 59.3 a | 38.0 b | 0.08 |

| Abnormal (%) | 15.3 a | 11.6 a | 15.5 a | 11.4 a | 20.3 a | 10.8 a | 15.0 a | 12.9 a | 0.35 |

| Head D (%) | 0.8 a,b | 2.6 a,b | 1.2 a,b | 1.7 a,b | 1.1 a,b | 1.7 a,b | 0.7 b | 3.0 a | 0.37 |

| IP D (%) | 3.1 a | 3.8 a | 1.9 a | 2.7 a | 2.2 a | 2.2 a | 1.5 a | 2.1 a | 0.24 |

| Tail D (%) | 9.6 a,b,c | 3.8 c | 10.9 a,b | 5.3 b,c | 15.3 a | 5.5 b,c | 11.0 a,b | 6.3 b,c | 0.40 |

| Parameters | G1 (Control) | G2 (Melatonin) | G3 (GSH) | G4 (GSH + Melatonin) | ±(Sqrt)SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Thawed | Fresh | Thawed | Fresh | Thawed | Fresh | Thawed | ||

| TS | 4.1 a | 37.6 b | 2.7 a | 35.3 b | 4.4 a | 38.9 b | 2.9 a | 36.8 b | 0.17 |

| TM | 93.4 a | 59.5 b | 95.4 a | 62.3 b | 94.0 a | 58.2 b | 95.4 a | 61.1 b | 0.11 |

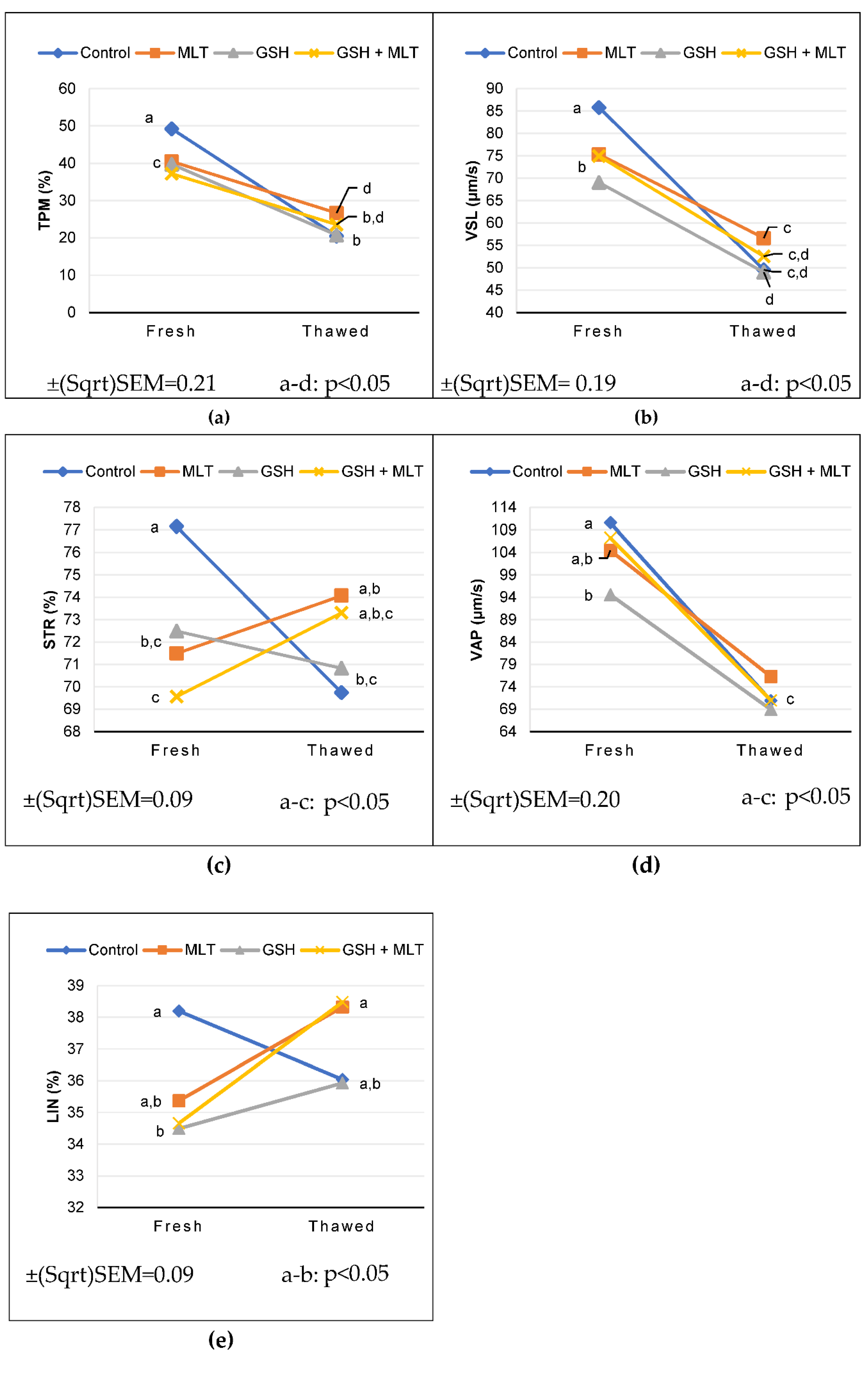

| TPM | 49.2 a | 20.5 b | 40.5 c | 26.7 d | 39.7 c | 20.8 b | 37.2 c | 23.6 b,d | 0.21 |

| Slow | 0.5 a | 3.4 b | 0.4 a | 3.2 b | 2.3 b | 3.7 b | 0.4 a | 4.5 b | 0.23 |

| Medium | 3.5 b,c | 6.1 a | 3.5 b,c | 5.5 a,b | 5.8 a,b | 5.9 a,b | 2.6 c | 5.8 a,b | 0.20 |

| Rapid | 87.1 a | 46.9 b | 89.0 a | 50.3 b | 83.0 a | 44.0 b | 89.5 a,b | 44.8 b | 0.21 |

| VCL | 222.0 a | 137.2 c | 211.3 a,b | 147.5 c | 197.8 b | 136.3 c | 216.6 a,b | 135.8 c | 0.29 |

| VSL | 85.8 a | 49.5 c,d | 75.3 b | 56.6 c | 69.0 b | 49.0 d | 75.0 b | 52.5 c,d | 0.19 |

| VAP | 110.6 a | 70.9 c | 104.5 a,b | 76.3 c | 94.6 b | 68.9 c | 107.3 a | 71.0 c | 0.20 |

| ALH | 3.6 a | 2.9 b | 3.6 a | 2.9 b | 3.5 a | 2.9 b | 3.6 a | 2.8 b | 0.03 |

| LIN | 38.2 a | 36.0 a,b | 35.4 a,b | 38.3 a | 34.5 b | 35.9 a,b | 34.7 b | 38.5 a | 0.09 |

| STR | 77.2 a | 69.7 b,c | 71.5 b,c | 74.1 a,b | 72.5 b,c | 70.8 b,c | 69.6 c | 73.3 a,b,c | 0.09 |

| WOB | 49.4 b,c,d | 51.3 a,b,c | 49.2 c,d | 51.5 a,b | 47.5 d | 50.4 a,b,c | 49.4 b,c,d | 52.2 a | 0.05 |

| BCF | 22.8 a | 18.5 c,d | 20.8 a,b | 19.7 b,c | 20.8 a,b | 17.6 d | 21.4 a,b | 19.2 b,c,d | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).