1. Introduction

Since organelles in sperm disappear during spermatogenesis, the ability to remove reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) generated from the frozen sperm cells is significantly lower than that of normal somatic cells [

1,

2]. Moreover, the oxidative stress that occurs in the process of freezing and thawing to preserve sperm is the cause of markedly reducing the viability of sperm.

Generally, non-permeable cryoprotectants (alpha-lactose and egg yolk) and permeable cryoprotectants (glycerol and Orvus Es Paste, OEP) are used to freeze boar sperm [

3]. The reason for using the freeze protection agent is to prevent damage to the sperm and to protect the sperm to maintain its function of the sperm. Although the release of intracellular water by the cryoprotectant is essential in the sperm freezing process, the sperm undergoes osmotic stress during this process [

3,

4]. As a result, it has been reported that ROS generates in sperm cells, and the sperm are damaged. For this reason, it is a critical study to maintain the viability of sperm with an appropriate concentration and co-treatments of antioxidants and to prevent sperm loss from oxidative stress.

ROS, which occurs in the freezing and thawing process of semen, is a typical cause of oxidative stress. An increase in ROS causes a decrease in sperm motility, viability, and fertilization ability [

5,

6]. In addition, since NO induces apoptosis and rapidly decreases the viability of sperm, suppressing or reducing the generation of NO is essential for protecting the frozen sperm [

7,

8]. Based on previous studies, we identified the concentrations of ROS and NO generated during the freeze-thawing process of semen. We treated melatonin and silymarin to increase the viability of sperm. Melatonin is an antioxidant, and silymarin has an antioxidant function [

9]. Melatonin scavenged ROS and free radicals in the animal and human body. In the brain, Melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland and has an essential function in the neuroendocrine system [

10]. Thus, melatonin regulates sperm quality and male reproduction, and it is not clear in the reproductive system of males, such as sperm in freezing semen. In particular, silymarin is a drug used to treat liver disease, and its action is known to protect and detoxify liver cells by removing ROS [

11]. However, there are no studies on the effects of ROS and NO, which generates during the freezing-thawing process of boar semen, with melatonin and silymarin in frozen-thawed sperm.

This study investigated how melatonin and silymarin act as antioxidants in sperm from boar frozen-thawed semen, which have not been identified yet. Also, we investigated the effect of melatonin and silymarin treatment on the viability of sperm. Since research on the effect of melatonin and silymarin on frozen-thawed semen is unclear, it is necessary to investigate which part of melatonin and silymarin plays a role in ROS and NO to affect sperm during the freezing and thawing of semen. Thus, this study aimed to identify the effect of melatonin and silymarin on frozen-thawed sperm. We examined the motility and viability of sperm, ROS, and NO production in frozen-thawed boar semen with melatonin and silymarin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Melatonin and silymarin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Semen

Fresh semen from ten crossbred pigs (Duroc × Yorkshire × Landrace, average ages = 28.7 ± 3.2 months) was collected by a glove-hand method. Collected semen was diluted with a Modena extender (

Table 1), transported to the laboratory, and then stored at 18.0℃ before the freezing experiment. Fresh semen samples were subjected to microscopic analysis using semen samples with at least 80% motile sperm [

12]. All experiments and guidelines were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University (KIACUC-09-0139).

2.3. Freezing and Thawing of Semen

A previous study carried a freezing extender [

13,

14]. First, the semen samples were centrifuged to remove seminal plasma for removing seminal plasma at 400 g for 5 min, and then, sperm fraction was only used for cryopreservation. Briefly, the 1

st freezing extender was composed of 11.0% α-lactose (Sigma, St. Louis MO, USA) and 20.0% egg yolk, and 2

nd freezing extender was made from the 1st freezing extender supplemented with 9.0% glycerol (Sigma) and 1.5% OEP (Nova Chemical Sales Inc., MA, USA). We added antioxidants in 1

st and 2

nd freezing extenders, such as 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 mM melatonin (Sigma) and 0, 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 mM silymarin (Sigma). Sperm were diluted with 1

st freezing extender at 18℃ and was cooling at 5℃ for 120 min, then diluted with 2

nd freezing extender at 5℃ of the half volume of 1

st freezing extender until 1.0 × 10

9 sperm/mL. Sperm was packaged into 0.5 mL straw (20 straws/semen/pig) and cooled to -120℃ for 10 min before being plunged into liquid nitrogen for storage using static nitrogen vapor [

12,

13]. The frozen sperm into straw was thawed in a water bath at 37.0℃ for 45 seconds and centrifuged at 410 g for 5 min, and then the freezing extender was removed. The samples were re-suspended to Modena until 1.0 × 10

7 sperm/mL for analysis of sperm viability, ROS, and NO production.

2.4. Evaluation of Sperm Motility

The motility of sperm was subjectively evaluated according to a standard method. To measure fresh and frozen-thawed sperm motility, a 10.0 μL sperm sample was placed on a pre-warmed slide glass and covered with a cover glass, and then put in the sample on a warm chamber. The total sperm motility was subjectively assessed by visual estimations. In at least 5 fields, sperm motility was determined and examined at × 200 magnification under a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.5. Sperm Viability Assay

The viability of frozen-thawed sperm was evaluated using a sperm Live/Dead kit (L-7011, Invitrogen, NY, USA) according to a previous study [

14]. The sperm samples were diluted with 40 nM SYBR-14 and 2.0 μM propidium iodide (PI), which were incubated at 38℃ for 5 min in a dark room, and then, these samples were centrifuged to remove supernatants at 410 g for 5 min. After incubation, stained 10,000-count sperm was measured using flow cytometry (FACSCaliber, BD, USA). Viability was analyzed using the dot-plot method (CELLQuest, version 6.0 software, BD).

2.6. Reactive oxygen Species Determination

In the thawed sperm, we measured the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) using a 2',7'-dichloro-fluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA, Invitrogen) [

15]. The produced ROS quantified by the DCF standard curve. After centrifuging a 1.0 mL semen sample with a concentration of 1.0 × 107 sperm/mL at 410 g for 5 min, 200.0 μL of the supernatants was mixed with 20.0 μL of 20.0 mM DCF-DA and incubated for 30 min. in an incubator at 37℃. After that, we measured the incubated samples for ROS production of sperm using a FACS [

8].

2.7. Production of Nitric Oxide

The production of nitric oxide was detected using a nitric oxide 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA) reagent (Sigma) [

16]. Briefly, we used a concentration of 1.0 × 107 sperm/mL in PBS at 410 g for washing for 10 min, and then DAF-2 DA was added to the suspension for a final concentration of 10.0 μM, and then, the sample incubated at 37℃ for 1 hr. After that, we measured the incubated samples for NO production of sperm using a FACS [

8].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher-protected least significant difference (PLSD) analysis was used for all statistical data analysis, using Stat View (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data were presented as mean ± standard error mean. A P-value < 0.05 probability was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Melatonin and Silymarin on Sperm Motility

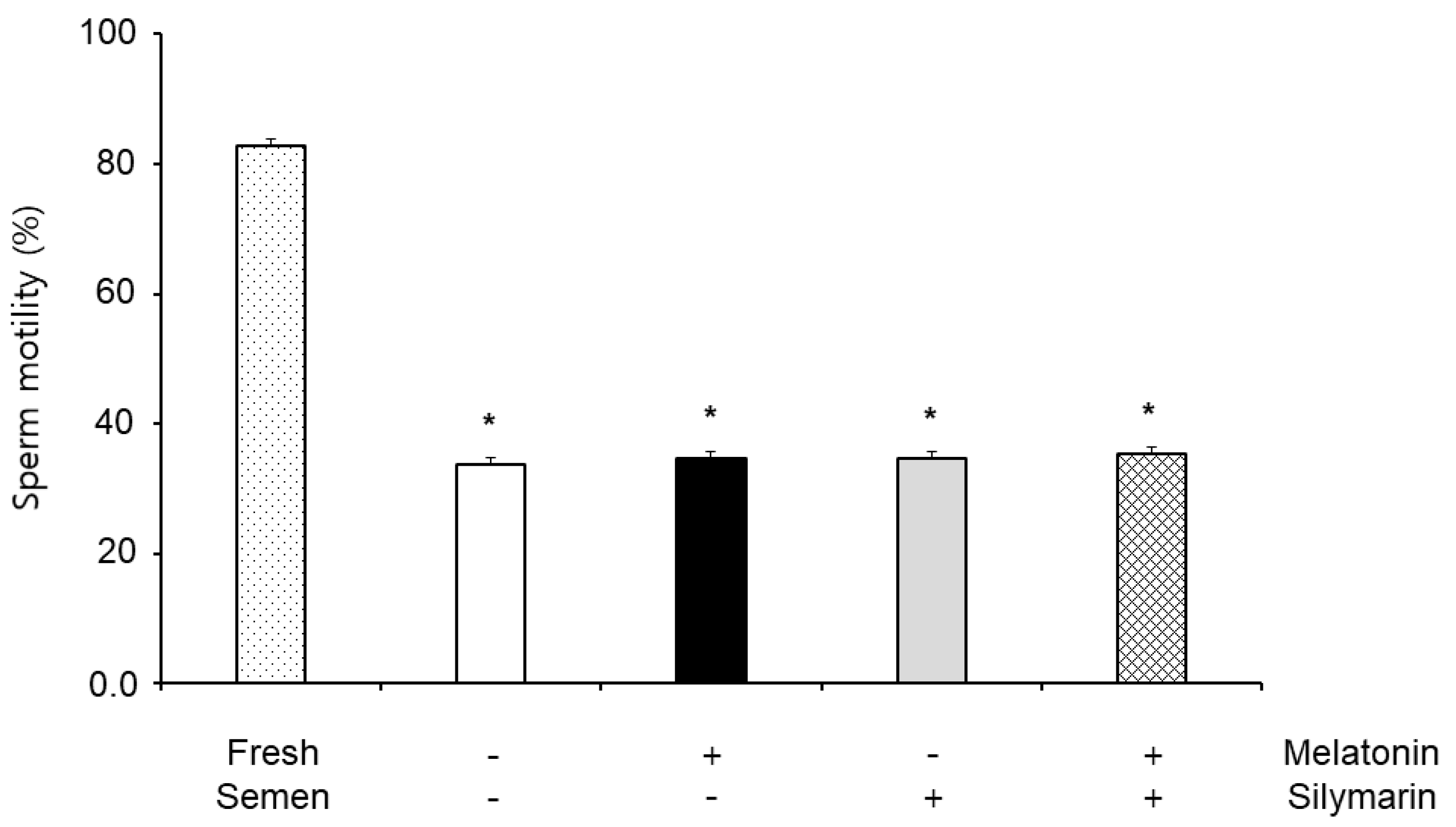

The effects of melatonin and silymarin on sperm motility are shown in

Figure 1. Sperm motility in frozen-thawed semen (33.82%) was significantly decreased compared with fresh semen (82.78%,

P < 0.05), but the sperm motility was not significantly different between non-treatment (33.82%), 0.1 mM melatonin (34.74%) and 0.01 mM silymarin (34.60%) treatments, and both treatment (35.34%).

3.2. Does-Dependent Effects of Melatonin and Silymarin on Sperm Viability

We first evaluated the viability of sperm on melatonin and silymarin concentrations in frozen-thawed semen.

Table 2 and

Table 3 show sperm viability on frozen-thawed semen was significantly increased in a dose-dependent 0.1 mM melatonin and 0.01 mM silymarin (

P < 0.05). Therefore, we used a concentration of 0.1 mM melatonin and 0.01 mM silymarin for determining ROS, NO production, and viability of sperm in frozen-thawed semen.

3.3. Effects of Melatonin and Silymarin on ROS and NO Production, and Sperm Viability

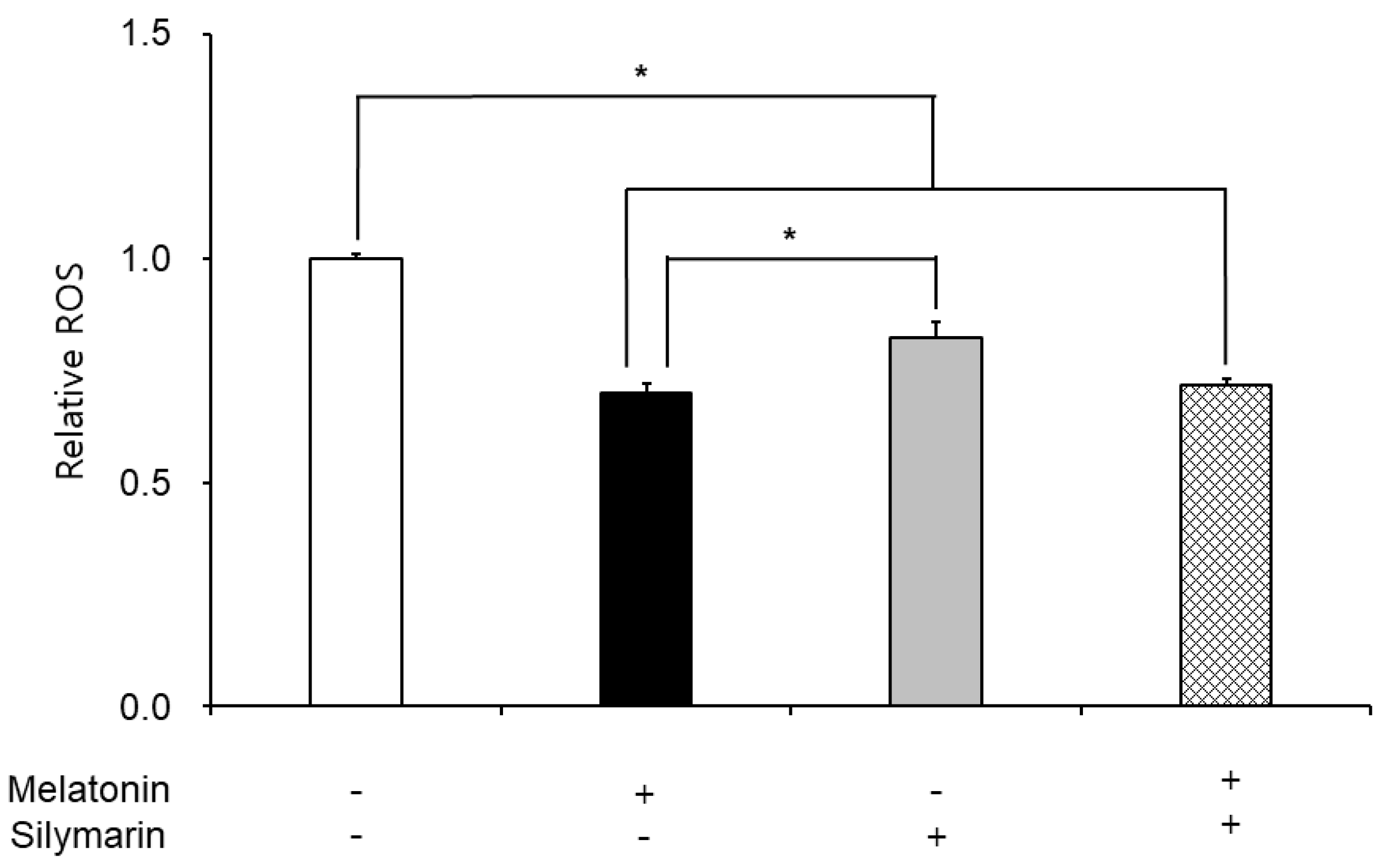

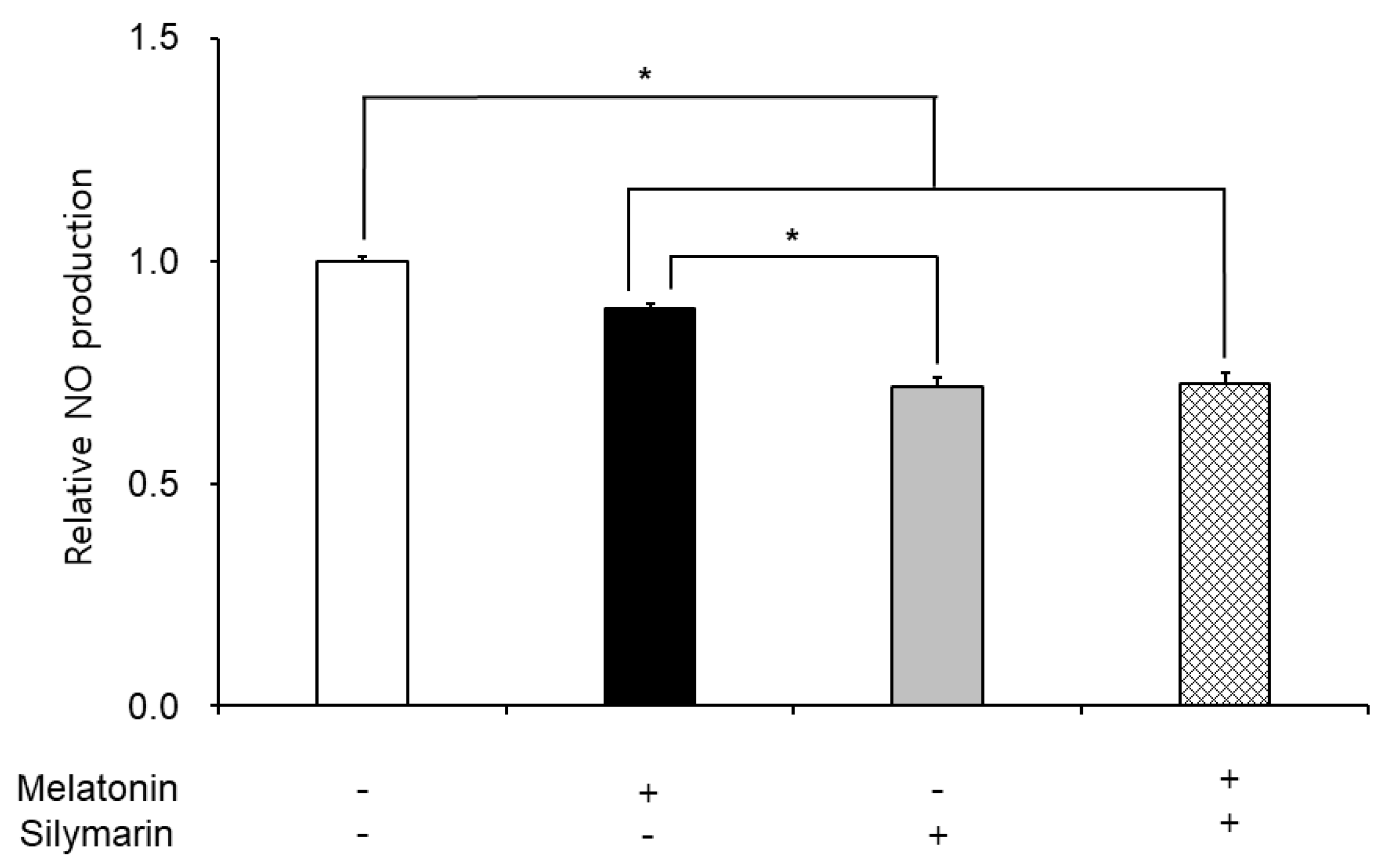

The effects of melatonin and silymarin on the ROS and NO production are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. ROS and NO production in melatonin and silymarin treatment groups were significantly decreased (

P < 0.05). And both treated groups were significantly lower than the non-treated group, not alone treated groups (

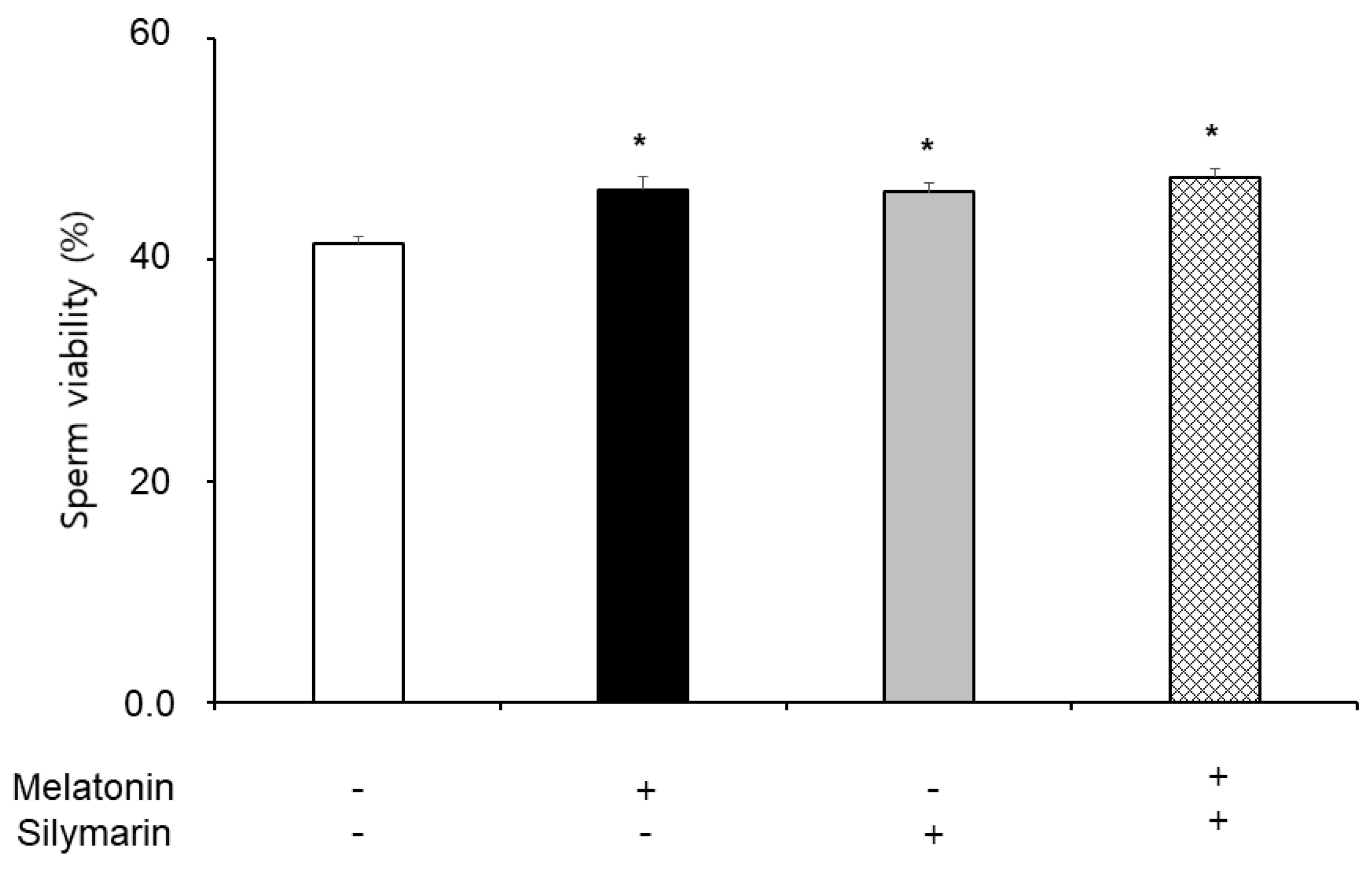

P < 0.05). Finally, the effects of melatonin and silymarin on the viability of sperm are shown in the

Figure 4. Sperm viability in both melatonin and silymarin-treated groups was higher than in the non-treated group, but not significantly different between the alone-treated groups (

P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The current study shows that sperm motility did not observe any significant differences in the frozen-thawed semen. Melatonin and silymarin did not regulate sperm motility, but frozen-thawed sperm has damage in the motility. It was suggested that melatonin and silymarin are not used for recovery and enhance viability in boar freezing semen.

In the present study, the treatment of melatonin and silymarin elevated the viability of frozen-thawed sperm, also co-treatment. Succu et al. reported that melatonin protects ram spermatozoa in cold shock [

17], and the reduction of melatonin induces oxidative damage in humans has been demonstrated [

18]. Karimfar et al. suggested that melatonin exerts its cryoprotective effects on spermatozoa, possibly by counteracting intracellular ROS, such as increasing the motility and viability of sperm in humans [

9]. Overall, reports that melatonin enhances the viability of sperm from frozen-thawed semen in animals and humans. Silymarin also increased sperm viability in the boar sperm. Almost research on silymarin is about hepatotoxic diseases, tumors, and carcinogenesis [

19,

20,

21]. Recently, Etemadi et al. reported that silymarin regulates cadmium-induced apoptosis in human spermatozoa [

22]. Cadmium increases ROS and lipid peroxidation levels in cells and rat testes [

23]. To our results, silymarin decreased ROS and NO production in frozen-thawed boar sperm. It may be a scavenger for ROS and NO in the freezing and thawing process of sperm. ROS and NO mediate apoptosis through oxidative stress in the cells. Cryopreservation is also essential for freezing sperm because it protects sperm osmotic pressure and oxidative stress in the freezing semen. Thus, we strongly suggest that silymarin is a potential antioxidant in frozen-thawed semen.

In this study, we have deeply discussed the effect of silymarin on sperm in frozen-thawed semen because many research groups reported that melatonin has the function of an antioxidant in the cells and improves the preservation of sperm function and quality. Nevertheless, the viability of sperm in freezing semen is lower than in fresh semen in humans and animals. Oxidative stress, such as free radicals, reactive oxygen species, and nitric oxide, leads to cell death. Thus, the viability of sperm in frozen-thawed semen is lower than in fresh semen. Especially, Ferrusola et al. suggested that cryopreservation induces nitric oxide production in spermatozoa [

9]. In the results of this study, we found that the antioxidant effects of melatonin and silymarin were different, carefully. Melatonin was involved in the general inhibition of ROS, and silymarin was involved in the inhibition of nitrogen oxide. There was a possibility that the treatment of silymarin inhibited nitric oxide synthesis. Thus, we suggest that silymarin treatment could inhibit nitric oxide synthesis.

Although the antioxidant function of silymarin is known, there is no study on which mechanism has an antioxidant effect. Some other studies reported that silymarin regulates the spermatogenesis process in rats [

24]. In bovine oviduct epithelial cells, Jang et al. reported that silymarin affects the survival rate in NO-induced oxidative stress experiments [

25]. NO is synthesized via neuronal NOS (nNOS, NOS1), inducible (iNOS, NOS2), and endothelial NOS (eNOS, NOS3). Especially, NOS1 and NOS2 are soluble and found in the cytosol, and NOS3 is membrane-associated [

26,

27]. ROS enhanced NO production in macrophages with iNOS expression, but LPS-stimulated ROS was decreased by an iNOS inhibitor [

28]. Salerno et al. reported that antioxidant inhibits nitric oxide synthase, nNOS, and eNOS [

29]. Since NO production is normally controlled by NOS (nNOS, iNOS, and eNOS), it is important in cells, also the sperm. We suggest that NO production regulates scavenging free radicals or inhibiting nitric oxide synthase in the frozen-thawed sperm. Thus, we are testing the nitric oxide synthesis experiment with silymarin to identify nitric oxide production in frozen-thawed sperm. Therefore, based on the results, we are experimenting to find out how nitric oxide synthesis by silymarin occurs. We will report a novel role of silymarin and the mechanism of silymarin in nitric oxide synthesis, as soon as possible. These results identified melatonin and silymarin enhanced sperm viability and decreased ROS and NO production in the frozen-thawed boar semen. These results suggest that melatonin and silymarin can use as the main antioxidant during sperm freezing in pigs. Furthermore, silymarin probably regulates nitric oxide synthesis more than ROS in freezing boar sperm. Thus we need to study nitric oxide synthesis with silymarin to understand the specific function in boar semen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.L. and S.L.; methodology, S.H.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, S.H.L. and S.L.; investigation, S.H.L. and S.L.; data curation, S.H.L. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.L., and S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.H.L. and S.L.; visualization, S.H.L., and S.L.; supervision, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program (S3246401), funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS, Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures that involved the use of animals followed the scientific and ethical regulations were followed by the Kangwon National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (KIACUC-09-0139).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ford, W.C.L. Reactive oxygen species and sperm. Hum. Fertil. 2001, 4, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorino, M.; Ursini, F. Oxidative stress, Spermatogenesis and Fertility. Biol. Chem. 2002, 383, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieme, H.; Oldenhof, H.; Wolkers, W.F. Mode of action of cryoprotectants for sperm preservation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 169, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, B.A.; Vo, A. Osmotic tolerance of equine spermatozoa and the effects of soluble cryoprotectants on equine sperm motility, viability, and mitochondrial membrane potential. J. Androl. 2001, 22, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfouz, R.Z.; du Plessis, S.S.; Aziz, N.; Sharma, R.; Sabanegh, E.; Agarwal, A. Sperm viability, apoptosis, and intracellular reactive oxygen species levels in human spermatozoa before and after induction of oxidative stress. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Gil, M.A.; Carvajal, G.; Garcia, E.M.; Cuello, C.; Vazquez, J.M.; Martinez, E.A. Survival and in vitro fertility of boar spermatozoa frozen in the presence of superoxide dismutase and/or catalase. J. Androl. 2005, 26, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Sabido, O.; Durand, P.; Levy, R. Cryopreservation induces an apoptosis-like mechanism in bull sperm. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 71, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Ferrusola, C.; Gonzalez Fernandez, L.; Macias Garcia, B.; Salazar-Sandoval, C.; Morillo Rodriguez, A.; Rodríguez Martinez, H.; Tapia, J.; Pena, F. Effect of cryopreservation on nitric oxide production by stallion spermatozoa. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimfar, M.; Niazvand, F.; Haghani, K.; Ghafourian, S.; Shirazi, R.; Bakhtiyari, S. The protective effects of melatonin against cryopreservation-induced oxidative stress in human sperm. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2015, 28, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, S.; Hagenaar, K.; Lampiao, F. The in vitro effects of melatonin on human sperm function and its scavenging activities on NO and ROS. Andrologia 2010, 42, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.F. Silymarin as a natural antioxidant: an overview of the current evidence and perspectives. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 204–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadea, J. Semen extenders used in the artificial insemination of swine. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2003, 1, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Oh, H.I.; Cheong, H.T.; Yang, B.K.; Lee, S.; Park, C.K. Effect of nicotinic acid on sperm characteristic and oocyte development after in vitro fertilization using cryopreserved boar semen. J. Emb. Trans. 2015, 30, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, B.K.; Park, C.K. Effect of cholesterol-loaded-cyclodextrin on sperm viability and acrosome reaction in boar semen cryopreservation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 159, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.J.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Jung, E.; Jun, J.H. Soybean peptides induce apoptosis in HeLa cells by increasing oxidative stress. Biomed. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H.; Nakatsubo, N.; Kikuchi, K.; Kawahara, S.; Kirino, Y.; Nagoshi, H.; Hirata, Y.; Nagano, T. Detection and imaging of nitric oxide with novel fluorescent indicators: diaminofluoresceins. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 2446–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Succu, S.; Berlinguer, F.; Pasciu, V.; Satta, V.; Leoni, G.G.; Naitana, S. Melatonin protects ram spermatozoa from cryopreservation injuries in a dose-dependent manner. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 50, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Melchiorri, D.; Sewerynek, E.; Poeggeler, B.; Barlow-Walden, L.; Chuang, J.; Ortiz, G.G.; Acuña Castroviejo, D. A review of the evidence supporting melatonin's role as an antioxidant. J. Pineal Res. 1995, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Lu, G.; Zhao, X. Modulatory effect of silymarin on pulmonary vascular dysfunction through HIF-1α-iNOS following rat lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 12, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.K. Silymarin and skin cancer prevention: anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects. Int. J. Oncol. 2005, 26, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lahiri-Chatterjee, M.; Sharma, Y.; Agarwal, R. Inhibitory effect of a flavonoid antioxidant silymarin on benzoyl peroxide-induced tumor promotion, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in SENCAR mouse skin. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etemadi, T.; Momeni, H.R.; Ghafarizadeh, A.A. Impact of silymarin on cadmium-induced apoptosis in human spermatozoa. Andrologia 2020, 52, e13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognjanović, B.I.; Marković, S.D.; Ðorđević, N.Z.; Trbojević, I.S.; Štajn, A.Š.; Saičić, Z.S. Cadmium-induced lipid peroxidation and changes in antioxidant defense system in the rat testes: Protective role of coenzyme Q10 and Vitamin E. Reprod. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, H.; Jahromi, H.K.; Hashemi, S.M.A.; Jashni, H.K.; Jahromi, Z.K.; Pourahmadi, M. The effect of silymarin on spermatogenesis process in rats. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2016, 5, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Park, I.; Yuh, I.; Cheong, H.; Kim, J.; Park, C.; Yang, B. Beneficial effects of silymarin against nitric oxide-induced oxidative stress on cell characteristics of bovine oviduct epithelial cell and developmental ability of bovine IVF embryos. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2014, 42, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuehr, D.J. Mammalian nitric oxide synthases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 1999, 1411, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.S.; Kim, Y.M.; Wang, Q.; Shapiro, R.A.; Billiar, T.R.; Geller, D.A. Nitric oxide down-regulates hepatocyte–inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression. Arch. Surg. 1997, 132, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.J.; Kwon, Y.G.; Chung, H.T.; Lee, S.K.; Simmons, R.L.; Billiar, T.R.; Kim, Y.M. Antioxidant enzymes suppress nitric oxide production through the inhibition of NF-κB activation: role of H2O2 and nitric oxide in inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in macrophages. Nitric Oxide-Biol.Chem. 2001, 5, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, L.; Modica, M.N.; Romeo, G.; Pittalà, V.; Siracusa, M.A.; Amato, M.E.; Acquaviva, R.; Di Giacomo, C.; Sorrenti, V. Novel inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase with antioxidant properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 49, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).