1. Introduction

With the rapid development of human society, the problem of pollution is becoming more and more serious, and people have adopted many methods to deal with the problem of pollution [

1,

2,

3]. Photocatalytic technology, as a new low-consumption, renewable and non-secondary pollution solution to pollution problems, has received extensive attention from researchers [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Through the continuous efforts of researchers, the photocatalytic materials have been greatly expanded, including oxides and sulfides such as ZnO、CdS、NiCo

2O

4 and CuInS

2 [

9,

10,

11,

12], perovskite such as CsPbCl

3 [

13], graphite-like phase g-C

3N

4 [

14] and mono-elemental red phosphorus [

15], and so on. Among numerous photocatalytic materials, ZnO is a promising photocatalyst because it possesses many excellent characteristics such as high electron mobility, low cost, nontoxicity and easy preparation [

16,

17]. However, it is very easy for photoinduced electrons and holes of ZnO to recombine, which brings the low quantum yield, thus limiting its photocatalytic activity. For purpose of inhibiting the recombination between the photoinduced electrons and holes in ZnO, the following methods have been investigated by researchers: (i) Doping metal or non-metallic ions into ZnO can change its electron-hole concentration, thereby inhibiting the recombination between the photoinduced electrons and holes [

18,

19]. However, it would be usually difficult for doping elements to be doped into the lattice of ZnO and improper doping will actually inhibit its activity. (ii) Deposition of noble metals, such as Pt, Ag and Au, on the surface of ZnO is a typical surface modification strategy for the improvement of its optical quantum efficiency [

20,

21]. However, the high cost of these precious metals is not conducive to the promotion and practical application of this technology. (iii) The technique of coupling ZnO with other semiconductors which possess proper energy bands will produce heterogeneous structures. The photoinduced charge carriers will be separated through directional transfer in the presence of potential difference or internal electric field generated by the heterojunction, which will result in the significant improvement of the photocatalytic efficiency of the ZnO [

22,

23]. Therefore, the construction of heterojunction is a very promising technology for facilitating the progress of ZnO photocatalytic research [

24,

25,

26].

Snln

4S

8, a typical polymetallic sulphide, has shown great latent capacity in the fields of the photocatalysis due to its unique structure. The SnIn

4S

8 material has a primary structure of nanoparticles and a secondary structure of micron-sized monodisperse sphere constructed from primary structure. This novel structure has two huge advantages for the application in the field of photocatalysis: (i) the primary structure provides a large specific surface area to adsorb more dye molecules; (ii) the secondary and porous structure can act as a light scattering center to improve the utilization of light. So far, Snln

4S

8 has been successfully prepared and applied to photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants [

27]. Most notably,benefitting from appropriate structure of Snln

4S

8 energy band, the photocatalytic activities of some materials can be enhanced by building a heterojunction with Snln

4S

8 [

28,

29,

30]. However, the investigation on the application of the Snln

4S

8/ZnO heterojunction in the field about photocatalytic degradation of effluent containing organic contaminant has not been reported yet.

As a common organic dye, methylene blue (MB) is one of the main components of wastewater from the printing and dyeing industry. The wastewater containing MB will cause serious ecological pollution and destruction. Furthermore, MB can result in adverse effects on human health, such as irreversible damage of the eyes, increased heart rate, vomiting, shock, unhealthy pallor, jaundice, and tissue necrosis. Therefore, how to degrade MB in wastewater has been the direction explored by many researchers.

In this work, for purpose of enhancing the photo quantum efficiency of ZnO, SnIn4S8@ZnO Z-scheme heterojunction was synthesized by a convenient two-step hydrothermal approach. Furthermore, the photocatalytic activity of SnIn4S8@ZnO was assessed through the degradation of MB under the irradiation of ultraviolet (UV) light.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of ZnO

ZnO in the form of nanosheets was prepared by a simple hydrothermal process. ZnCl2 aqueous solution (50 mL, 1 mol/L) and KOH aqueous solution (20 mL, 7.5 mol/L) were prepared, respectively. The above two solutions were mixed, agitated for 20 min, then poured into a stainless steel autoclave with Teflon-lining whose volume was 100 mL. Afterwards, the sealed autoclave was heated in the electric oven at 180°C for 10 h, and then naturally cooled to ambient temperature. Finally, the product was separated through centrifugation, washed several times using deionized water and anhydrous alcohol, dried at 60°C for 10 h, and then ground for the formation of ZnO powders.

2.2. Synthesis of SnIn4S8@ZnO heterojunction

The typical procedure for SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction synthesis was as follows. Firstly, 70 mL of anhydrous ethanol solution with a certain quantity of SnCl

4·5H

2O was prepared. Secondly, a certain quantity of InCl

3·4H

2O was dissolved in the solution which was stirred for 10 min. Thirdly, 2.0345g of the as-prepared ZnO was mixed into the solution which was agitated for 20 min. Fourthly, a certain quantity of CH

4N

2S was mixed into the solution which was agitated for 20 min. Fifthly, the solution was poured into a stainless steel autoclave with Teflon-lining whose volume was 100 mL, the sealed autoclave was heated in an electric oven at 160°C for 10 h and then naturally cooled to ambient temperature. Finally, the products were washed using deionized water, dehydrated under vacuum at 70°C for 10 h, and then ground for further use. The obtained samples were recorded as ZSX (X = 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000), where X represented the molar ratio of ZnO to SnIn

4S

8. In addition, SnIn

4S

8 was prepared through the same approach mentioned above except addition of as-synthesized ZnO. The flow chart of the synthesis of the SnIn

4S

8, ZnO and SnIn

4S

8@ZnO samples is exhibited in

Figure 1.

2.3. Characterizations

The phase compositions of the as-synthesized samples were analyzed via an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku Smartlab3kw, Japan). The morphologies of the samples were described using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Zeiss Sigma 300, Germany) and a transmission electron microscope (TEM, FEI Titan G2 60-300, US). The distribution of elements was analyzed through energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) detector (Oxford X-Max, UK) which was merged into the FESEM. A UV-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2550, Japan) was used to characterize the absorption spectra of specimens. A fluorescence spectrophotometer (Lengguang Tech. F97XP, China) was used to test the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of specimens.

2.4. Photocatalytic degradation of MB

The photocatalytic efficiencies of specimens were evaluated through choosing MB as model pollutant. 15 mg of catalyst powders were added into MB solution (100 mL, 10 mg/L). The mixture was treated for 10 min through ultrasonic vibration and then agitated for 30 min in the dark to reach adsorption/desorption equilibrium. After that, the constantly stirred mixture was illuminated by an ultraviolet lamp whose power and irradiation peak wavelength was 36 W and 365 nm, respectively. 5 ml of the mixture was extracted at the interval of 5 min, and then the photocatalyst was removed through centrifugation. Finally, the UV-Vis spectrophotometer was used to determine the absorbance of solution at 664 nm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD analysis

The XRD spectra of ZnO, SnIn

4S

8 and ZSX with a scanning speed of 10°/min are displayed in

Figure 2a. Among them, the characteristic peaks of ZnO can correspond to (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201), (004), and (202) crystalline facets of the hexagonal wurtzite phase of ZnO (JCPDS card No. 36-1451) [

31]. The characteristic peaks of SnIn

4S

8 at 2θ = 18.7°, 28.6°, 33.2°, 48.3° and 50.1°, which are consistent with the (202), (222), (400), (440) and (531) crystal faces of cubic phase of SnIn

4S

8 (JCPDS card No. 42-1305), separately, can be observed [

32]. Furthermore, no characteristic peaks of any foreign substance can be found in the XRD spectra, suggesting an excellent purity of the as-prepared SnIn

4S

8. In addition, the characteristic peaks of ZSX samples can be ascribed to the diffraction planes of ZnO (JCPDS card No. 36-1451). However, no diffraction peaks corresponding to SnIn

4S

8 can be found in the XRD patterns of ZSX samples, which should be attributed to the low level of SnIn

4S

8 in ZSX specimens and relatively fast scanning rate of XRD. In order to verify the existence of SnIn

4S

8 in ZSX samples, the as-prepared ZS1000 was test through XRD with a scanning rate of 4°/min and the pattern (

Figure 2b) clearly displays that the diffraction peaks at 18.7° and 28.6° can be ascribed to (202) and (222) plane of SnIn

4S

8 (JCPDS card No. 42-1305).

3.2. Morphological analysis

The FSEM photographs of ZnO, SnIn

4S

8 and ZSX samples are presented in

Figure 3. It can be seen that the ZnO showed flaky morphology with smooth surface (

Figure 3a). The as-prepared SnIn

4S

8 showed a morphology of 3D hierarchical reticular microspheres with diameters of 2-4 μm (

Figure 3b,c). From the magnified FSEM picture, it can be observed that the microspheres were composed of many two-dimensional nanoflakes with a thickness of about 20 nm. Furthermore, the microspheres possessed a porous appearance because of the interlacing of nanoflakes. The SEM images of ZSX samples show that many SnIn

4S

8 nanoparticles were unevenly distributed on the surface of the ZnO Substrate (

Figure 3d-h). Furthermore, the number of nanoparticles gradually decreased with the increase of the molar ratio of ZnO to SnIn

4S

8. Moreover, EDX elemental mapping analysis of ZS200 demonstrated that the elements Zn, O, Sn, In and S existed in ZSX samples (

Figure 4), which can further suggest that the large flake-like substrates were ZnO and the small nanoparticles were SnIn

4S

8.

The TEM photo of ZS800 obviously indicates that the SnIn

4S

8 nanoparticles densely covered the surface of the nanoflake-like ZnO to obtain the SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction (

Figure 5a). Two kinds of lattice fringes are clearly displayed in HRTEM image of ZS800 , as shown in

Figure 5b, the observed interplanar spacing of 0.247nm corresponded to ZnO (101) plane (JCPDS card No. 36-1451), and the characteristic interplanar spacing of 0.268nm belonged to SnIn

4S

8 (400) plane (JCPDS card No. 42-1305) [

31,

33]. Furthermore, it can be observed that the contact interface between ZnO and SnIn

4S

8 is very tight. The results mentioned above demonstrate that the SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction has been successfully constructed. The tight contact interface between SnIn

4S

8 and ZnO should be beneficial for the migration of photogenerated charge carriers and the stability of structure. As a consequence, the SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction would exhibit the enhanced photocatalytic activity.

3.3. UV-Vis absorption spectra analysis

The light-harvesting ability can be regarded as a crucial factor for the photocatalytic activity of semiconductors. It can be found from the UV-vis absorption spectra (

Figure 6a) that all the samples exhibited strong optical absorption in the region of UV. Moreover, the ZSX samples exhibited absorption cutoff wavelengths with slight redshift and the improvements of absorption capability in the Vis range compared to pure ZnO. The band gap (E

g) of the crystalline semiconductors can be obtained using the Kubelka:

Where α is the absorbance, hv is the photon energy, and A is a constant [

34]. The selection of n value (1 for direct transition, while 4 for indirect transition) is based on the transition property in the semiconductor [

35]. The band gap energy of as-synthesized specimens was determined through selecting n as 1 because both SnIn

4S

8 and ZnO are direct transition semiconductors.

Figure 6b presents the (αhν)

2 curves with hv of ZnO and ZS800, the band gaps can be calculated through lengthening the linear portion to the x-axis, which indicates that the band gaps of ZnO and ZS800 were about 3.22eV and 3.19eV, respectively. The narrowing of bandgap energy suggested that light-harvesting capability of ZnO was improved by the hybridization with SnIn

4S

8.

3.4. PL spectra analysis

The recombination rate of photoinduced charge carriers can be reflected through the peak intensity of PL spectrum. Normally, a weaker peak intensity reflects a higher separation efficiency of the photogenerated charge carriers, which results in a better photocatalytic performance [

36,

37]. The PL spectra of the as-synthesized ZnO and ZSX specimens are displayed in

Figure 7, which reveals that all specimens had similar PL spectra with two distinct luminescence peaks at approximate 400 and 460 nm. The peak at about 400 nm was the emission near the edge of the band, which originated from the recombination of the free-excitons through the collision between the excitons, and the peak at about 460nm may be the result from the inherent defects of ZnO [

38,

39]. Furthermore, compared with ZnO, the intensity of the fluorescence spectra of ZSX samples were significantly reduced. It indicated that SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction had a lower recombination rate of photogenerated charge carriers, which would be beneficial for the improvement of photocatalytic performance of catalyst [

40].

3.5. Photocatalytic activities of the specimens

The MB photodegradation curves over ZnO and ZSX samples are shown in

Figure 8a, and the ultimate degradation rates of MB after 20 min are exhibited in

Figure 8b. The changes of MB concentrations were very small when MB was adsorbed for 30 min using all samples in the dark, which indicated that the adsorption effects of the ZnO and ZSX samples on MB were negligible. After 20 min of UV illumination, the degradation rates of MB degraded by ZnO, ZS200, ZS400, ZS600, ZS800 and ZS1000 were 66%, 88%, 88%, 86%, 91% and 87%, respectively. Compared with the ZnO, the ZSX samples exhibited obviously improved photocatalytic activities. Furthermore, ZS800 had the highest photocatalytic efficiency for MB degradation.

Generally speaking, the photodegradation of MB complies with the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation:

Where k, t, C

0, and C

t are the apparent rate constant, the photocatalytic reaction time, the MB concentrations at the moment of t = 0 and a certain time, respectively [

41]. The kinetic curves of MB photodegradation in presence of ZnO and ZSX samples were fitted by plotting ln(C

0/C

t) versus time (

Figure 8c), and the good inear relationship can be observed. The gradient of kinetic curve denotes k value which corresponds to the degradation efficiency. The k values of MB degradation over ZnO, ZS200, ZS400, ZS600, ZS800 and ZS1000 were 0.054, 0.108, 0.109, 0.101, 0.121 and 0.102 min

-1, separately (

Figure 8d). It can be found that k value of ZSX samples for MB degradation were obviously higher than that of ZnO. Furthermore, ZS800 had the highest k value which was approximately 2.2 times over that of ZnO. These results indicate that the photocatalytic activity of the ZnO can be significantly boosted through hybridization with SnIn

4S

8 for the formation of SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction which is an efficient photocatalyst.

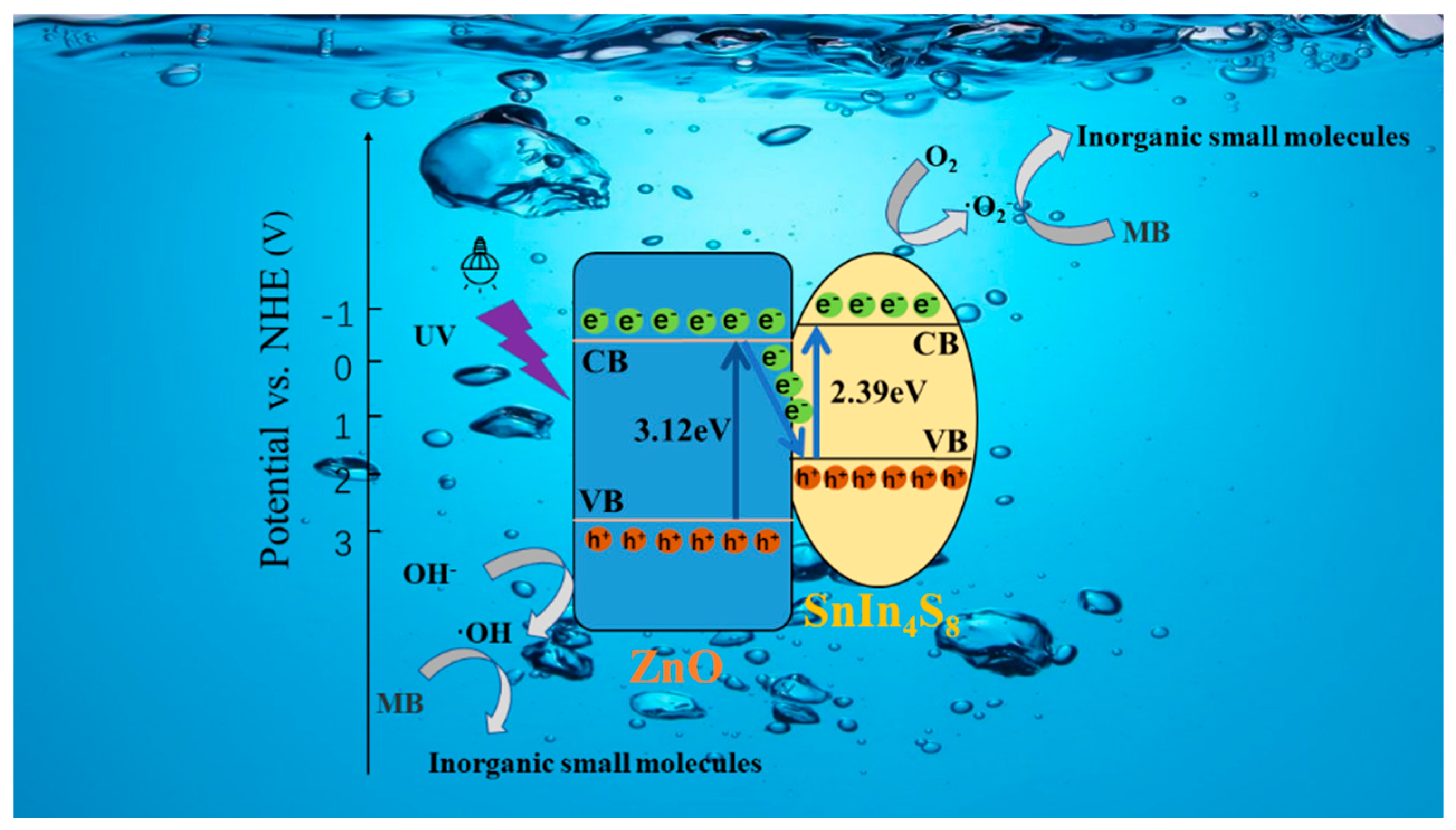

3.6. Photocatalytic mechanism analysis

According to the results in this work and several previous investigations, a Z-scheme mechanism can be proposed for efficient degradation of MB by the SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction, as shown in

Figure 9. The previous investigations indicate that the conduction band (CB) position of SnIn

4S

8 is higher than that of ZnO, while the valence band (VB) position of ZnO is lower than that of SnIn

4S

8 [

42,

43,

44]. Under the irradiation of UV light, the photoinduced electrons can transfer from the VB of the ZnO and SnIn

4S

8 to the CB of them, respectively, keeping the photogenerated holes in the VB of them. Then the photoinduced electrons in the CB of the ZnO can migrate to the VB of the SnIn

4S

8 owing to the appropriate potential difference. Eventually, a Z-shaped migration path of photogenerated electrons is formed in the SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction. This mechanism results that the photoinduced electrons collect in CB of SnIn

4S

8 while the photoinduced holes gather in VB of ZnO. These photoexcited electrons and holes are efficiently separated in the opposite side of SnIn

4S

8@ZnO heterojunction. Therefore, the life span of photo-induced carriers can be greatly improved, leading to remarkable improvement of photocatalytic activity. The photoinduced holes in VB of ZnO are vital oxidants, they can quickly oxidize hydroxyl anions (OH

-) to hydroxyl radicals (·OH). The photogenerated electrons in CB of SnIn

4S

8 are robust reductants, they can rapidly reduce dissolved oxygen (O

2) into superoxide radicals (·O

2-). Finally, the MB molecules can be degraded into the inorganic small molecules by these highly active ·OH and ·O

2- species. Overall, the main reactions of this mechanism can be expressed as below.

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

4. Conclusions

In this work, SnIn4S8@ZnO Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst was successfully acquired through a convenient two-step hydrothermal approach. The as-synthesized SnIn4S8@ZnO exhibited significantly enhanced photocatalysis activity under UV light irradiation. The degradation ability of the SnIn4S8@ZnO structure towards MB was significantly stronger than that of pure ZnO. The remarkable performance for MB photodegradation can be ascribed to the efficient spatial separation of photoinduced electrons and holes through a Z-scheme heterojunction with intimate contact interface. To conclude, the results in this paper will bring a novel insight into constructing excellent ZnO-based photocatalytic systems for wastewater purification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and C.S.; methodology, Q.C. and S.Y.; software, C.S. and J.Z.; data curation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, Q.L. and J.Z.; supervision, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Materials Processing and Die & Mould Technology, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, grant number P2023-028.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mali, H.; Shah, C.; Raghunandan, B.H.; Prajapati, A.S.; Patel, D.H.; Trivedi, U.; Subramanian, R.B. Organophosphate pesticides an emerging environmental contaminant: Pollution, toxicity, bioremediation progress, and remaining challenges. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 127, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, B.; Sun, C. Can payment vehicle influence public willingness to pay for environmental pollution control? Evidence from the CVM survey and PSM method of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, A.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Dong, F.; Zhou, Y. Surface modification to control the secondary pollution of photocatalytic nitric oxide removal over monolithic protonated g-C3N4/graphene cxide aerogel. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 397, 122822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuño, M.; Pesce, G.L.; Bowen, C.R.; Xenophontos, P.; Ball, R.J. Environmental performance of nano-structured Ca(OH)2/TiO2 photocatalytic coatings for buildings. Build. Environ. 2015, 92, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.H.A.; Li, K.; Zeng, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhan, Y.; Xie, R.; Leung, D.Y.C.; Huang, H. Titanium oxide based photocatalytic materials development and their role of in the air pollutants degradation: overview and forecast. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 200–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghizadeh, M.; Taher, M.A.; Tamaddon, A.M. Facile synthesis and characterization of magnetic nanocomposite ZnO/CoFe2O4 hetero-structure for rapid photocatalytic degradation of imidacloprid. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Cui, Z.; Li, P.; Pan, C. One-step construction of multi-walled CNTs loaded with Alpha-Fe2O3 nanoparticles for efficient photocatalytic properties. Materials 2021, 14, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, B.; Zheng, Z.; Luo, D. Strategies to enhance photocatalytic activity of graphite carbon nitride-based photocatalysts. Mater. Design 2021, 210, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Nair, R.G. Effect of aspect ratio on photocatalytic performance of hexagonal ZnO nanorods. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 817, 153277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, K.S.; Labhane, P.K.; Dhake, R.B.; Sonawane, G.H. Solvothermal synthesis of activated carbon loaded CdS nanoflowers: Boosted photodegradation of dye by adsorption and photocatalysis synergy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 744, 137202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chai, J.; Lu, S.; Mu, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, Q.; Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, B. Solution-phase vertical growth of aligned NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays on Au nanosheets with weakened oxygen-hydrogen bonds for photocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 6195–6203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chumha, N.; Pudkon, W.; Chachvalvutikul, A.; Luangwanta, T.; Randorn, C.; Inceesungvorn, B.; Ngamjarurojana, A.; Kaowphong, S. Photocatalytic activity of CuInS2 nanoparticles synthesized via a simple and rapid microwave heating process. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 015074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Xi, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhao,Y. ; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Guo, P.; Xu, J. Novel inorganic perovskite quantum dots for photocatalysis. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 12032–12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewnet, A.; Alemayehu, E.; Abebe, M.; Mani, D.; Thomas, S.; Lennartz, B. Hydrothermal synthesis of heterostructured g-C3N4/Ag-TiO2 nanocomposites for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Materials 2023, 16, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Wen, L.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y. Electronic properties of red and black phosphorous and their potential application as photocatalysts. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 80872–80884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dhiman, A.; Sudhagar, P.; Krishnan, V. ZnO-graphene quantum dots heterojunctions for natural sunlight-driven photocatalytic environmental remediation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 447, 802–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Jin, Z.; Yang, J.; Hu, R.; Zhao, F.; Gao, X.; Zhao, C. Highly efficient and stable p-LaFeO3/n-ZnO heterojunction photocatalyst for phenol degradation under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 377, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiano, V.; Iervolino, G.; Rizzo, L. Cu-doped ZnO as efficient photocatalyst for the oxidation of arsenite to arsenate under visible light. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 238, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, J.; Cao, L.; Li, J.; Ou Yang, H.; Yao, C. Microwave hydrothermal synthesis of Sr2+ doped ZnO crystallites with enhanced photocatalytic properties. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 2647–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, D. Regulating charge transfer over 3D Au/ZnO hybrid inverse opal toward efficiently photocatalytic degradation of bisphenol A and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124676. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, S.; Sahu, K.; Khan, S.A.; Tripathi, A.; Avasthi, D.K.; Mohapatra, S. Facile synthesis of Au-ZnO plasmonic nanohybrids for highly efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Opt. Mater. 2017, 64, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Qu, S.; Wang, Z. Engineering the photoelectrochemical behaviors of ZnO for efficient solar water splitting. J. Semicond. 2020, 41, 091702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, H.; Mahmood, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Yip, A.C.K. Photocatalysts for degradation of dyes industrial effluents: Opportunities and challenges. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 955–972. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Shi, J.; Sun, D.; Zou, Y.; Cheng, L.; He, C.; Wang, H.; Niu, C.; Wang, L. Au decorated hollow ZnO@ZnS heterostructure for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution: The insight into the roles of hollow channel and Au nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2019, 244, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Han, X.; Lv, K.; Dong, R.; Hang, Z.; Xin, B.; Zheng, K. Ultrasound-enhanced preparation and photocatalytic properties of graphene-ZnO nanorod composite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 259, 118131. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, P.; Xing, L.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Xue, X. Direct Z-scheme heterojunction of ZnO/MoS2 nanoarrays realized by flowing-induced piezoelectric field for enhanced sunlight photocatalytic performances. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 285, 119785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Guan, X. Porous SnIn4S8 microspheres in a new polymorph that promotes dyes degradation under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y. Visible-light-driven double-shell SnIn4S8/TiO2 heterostructure with enhanced photocatalytic activity for MO removal and Cr(VI) cleanup. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 587, 152867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, F.; Su, M.; Wei, D.; Yang, Q.; Yan, T.; Li, D. Fabrication of MOF-derived tubular In2O3@SnIn4S8 hybrid: Heterojunction formation and promoted photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) under visible light. J. Colloid Interf. Sci 2021, 596, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.; Tang, Z. Construction of novel Z-scheme flower-like Bi2S3/SnIn4S8 heterojunctions with enhanced visible light photodegradation and bactericidal activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Raji, R.; Gopchandran, K.G. Plasmonic photocatalytic activity of ZnO: Au nanostructures: Tailoring the plasmon absorption and interfacial charge transfer mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 368, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Shaya, J.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Golovko, V.B.; Tesana, S.; Wang, S.; Lu, C. Photocatalytic degradation of ethiofencarb by a visible light-driven SnIn4S8 photocatalyst. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Song, W.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Hou, B.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, P. Preparation of SnIn4S8/TiO2 nanotube photoanode and its photocathodic protection for Q235 carbon steel under visible light. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, S.; Su, X.; Ma, C. A direct Z-scheme polypyrrole/Bi2WO6 nanoparticles with boosted photogenerated charge separation for photocatalytic reduction of Cr (VI): Characteristics, performance, and mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, Z. In situ construction of hierarchical WO3/g-C3N4 composite hollow microspheres as a Z-scheme photocatalyst for the degradation of antibiotics. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 220, 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Cai, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Characterization and photocatalytic activity of large-area single crystalline anatase TiO2 nanotube films hydrothermal synthesized on plasma electrolytic oxidation seed layers. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 597, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Li., X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Microwave assisted synthesis of reduced graphene oxide incorporated MOF-derived ZnO composites for photocatalytic application. Catal. Commun. 2017, 88, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.; Karunagaran, B.; Suh, E.K.; Hahn, Y.B. Structural and optical properties of single-crystalline ZnO nanorods grown on silicon by thermal evaporation. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 4072–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, W.J.; Zhou, T.; Hu, B.Q. Growth and luminescence characterization of large-scale zinc oxide nanowires. J. Phys.,Condens. Matter. 2003, 15, 2221–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Tong, Z.; Li, S.; Yin, Y. Enhancing the photocatalytic activity of ZnO by using tourmaline. Mater. Lett. 2019, 240, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Xia, P.; Xie, Y.; Xiong, D. Synthesis of the 0D/3D CuO/ZnO heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 9531–9539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Zuo, Y.; He, G.; Chen, Q.; Meng, Q.; Chen, H. Reduced graphene oxide supported ZnO/CdS heterojunction enhances photocatalytic removal efficiency of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Wen, X.; Liu, Z.; Xing, R.; Guo, H.; Fei, Z. Efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution and Cr (VI) reduction under visible light using a novel Z-scheme SnIn4S8/CeO2 heterojunction photocatalysts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, H. DFT-proved Z-type ZnO/SnIn4S8 heterojunction for detecting hexavalent chromium. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 922, 166266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).